Abstract

The 18 kDa translocator protein (TSPO), previously known as the peripheral benzodiazepine receptor, is predominately localized to the outer mitochondrial membrane in steroidogenic cells. Brain TSPO expression is relatively low under physiological conditions, but is upregulated in response to glial cell activation. As the primary index of neuroinflammation, TSPO is implicated in the pathogenesis and progression of numerous neuropsychiatric disorders and neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer's disease (AD), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), Parkinson's disease (PD), multiple sclerosis (MS), major depressive disorder (MDD) and obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD). In this context, numerous TSPO-targeted positron emission tomography (PET) tracers have been developed. Among them, several radioligands have advanced to clinical research studies. In this review, we will overview the recent development of TSPO PET tracers, focusing on the radioligand design, radioisotope labeling, pharmacokinetics, and PET imaging evaluation. Additionally, we will consider current limitations, as well as translational potential for future application of TSPO radiopharmaceuticals. This review aims to not only present the challenges in current TSPO PET imaging, but to also provide a new perspective on TSPO targeted PET tracer discovery efforts. Addressing these challenges will facilitate the translation of TSPO in clinical studies of neuroinflammation associated with central nervous system diseases.

KEY WORDS: TSPO, Microglial activation, Neuroinflammation, Positron emission tomography (PET), CNS disorders

Abbreviations: AD, Alzheimer's disease; ALS, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; Am, molar activities; AMPA, α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole propionic acid; ANT, adenine nucleotide transporter; BBB, blood‒brain barrier; BcTSPO, Bacillus cereus TSPO; BMSC, bone marrow stromal cells; BP, binding potential; BPND, non-displaceable binding potential; CBD, corticobasal degeneration; CNS, central nervous system; CRAC, cholesterol recognition amino acid consensus sequence; d.c. RCYs, decay-corrected radiochemical yields; DLB, Lewy body dementias; dMCAO, distal middle cerebral artery occlusion; EP, epilepsy; fP, plasma free fraction; FTD, frontotemporal dementia; HAB, high-affinity binding; HD, Huntington's disease; HSE, herpes simplex encephalitis; IMM, inner mitochondrial membrane; KA, kainic acid; LAB, low-affinity binding; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; MAB, mixed-affinity binding; MAO-B, monoamine oxidase B; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; MDD, major depressive disorder; MMSE, mini-mental state examination; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; MS, multiple sclerosis; MSA, multiple system atrophy; NAA/Cr, N-acetylaspartate/creatine; n.d.c. RCYs, non-decay-corrected radiochemical yields; OCD, obsessive compulsive disorder; OMM, outer mitochondrial membrane; PAP7, RIa-associated protein; PBR, peripheral benzodiazepine receptor; PCA, posterior cortical atrophy; PD, Parkinson's disease; PDD, PD dementia; PET, positron emission tomography; p.i., post-injection; PKA, protein kinase A; PpIX, protoporphyrin IX; PRAX-1, PBR-associated protein 1; PSP, progressive supranuclear palsy; P2X7R, purinergic receptor P2X7; QA, quinolinic acid; RCYs, radiochemical yields; ROS, reactive oxygen species; RRMS, relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis; SA, specific activity; SAH, subarachnoid hemorrhage; SAR, structure–activity relationship; SCIDY, spirocyclic iodonium ylide; SNL, selective neuronal loss; SNR, signal to noise ratio; SUV, standard uptake volume; SUVR, standard uptake volume ratio; TBAH, tetrabutyl ammonium hydroxide; TBI, traumatic brain injury; TLE, temporal lobe epilepsy; TSPO, translocator protein; VDAC, voltage-dependent anion channel; VT, distribution volume

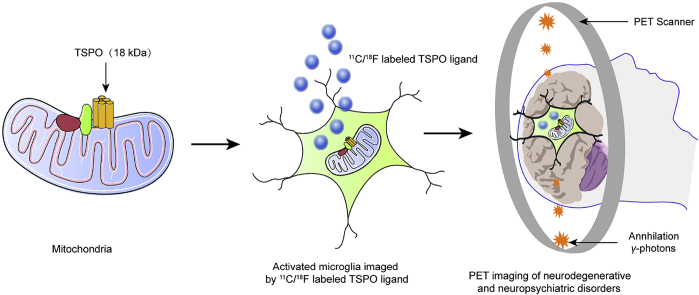

Graphical abstract

The 18 kDa translocator protein (TSPO) expression in the central nervous system is upregulated in response to glial cell activation. There is a great potential for the future application of TSPO radioligands as diagnostic and prognostic tools, as well as for assessing therapeutic interventions for neurologic diseases.

1. Introduction

The 18 kDa translocator protein (TSPO)1, first described as the peripheral benzodiazepine receptor (PBR), is mainly expressed in the outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM), in particular at the interface between OMM and inner mitochondrial membrane (IMM)2. TSPO has 169 amino acids and consists of five transmembrane α-helix domains, which are joined by two extramitochondrial and intramitochondrial loops, an extramitochondrial C-terminal, and an intramitochondrial N-terminal. The first and third loops are located on the cytoplasmic side of the membrane, while the second and fourth loops face the inside of the mitochondria3 (Fig. 1). Li et al.4 first described a cholesterol recognition amino acid consensus sequence (CRAC) in the C-terminus of TSPO, which was determined to be helical in conformation from amino acids L144 to S1595. CRAC, together with a groove in TSPO, can bind a cholesterol molecule and is thus responsible for cholesterol transport4,5 (Fig. 1). TSPO generally functions as a monomer6, but it has been demonstrated to form oligomeric compounds with itself (homo-oligomer) or other proteins, such as a 32 kDa voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC) and a 30 kDa adenine nucleotide transporter (ANT)7. Additionally, increased levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) can facilitate covalent binding among TSPO monomers, inducing the formation of TSPO oligomers8. TSPO monomers can recognize cholesterol, and TSPO homo-oligomers may also play an important role in binding and transporting cholesterol7. TSPO is rich in tryptophan, a feature that is highly conserved from bacteria to mammals. Guo et al.9 recently reported the complex crystal structure of Bacillus cereus TSPO (BcTSPO) with its inhibitor, PK11195, at a resolution down to 1.7 Å. These authors also described similar TSPO protoporphyrin IX (PpIX)-directed catalytic activities in both Xenopus and humans, demonstrating the physiological importance of TSPO in protection against oxidative stress. Subsequently, Li et al.10 described the crystal structures (at 1.8, 2.4, and 2.5 Å resolution) for TSPO from Rhodobacter sphaeroides and a mutant TSPO that simulated the human rs6971 polymorphism (Ala147→Thr147). The A147T mutation in humans perturbs the environment around the CRAC site and could transform the TSPO cholesterol-binding surface. Additionally, variation in the tilt of the helices leads to decreased binding with other ligands, indicating that the A147T mutation causes a lower-affinity conformational change.

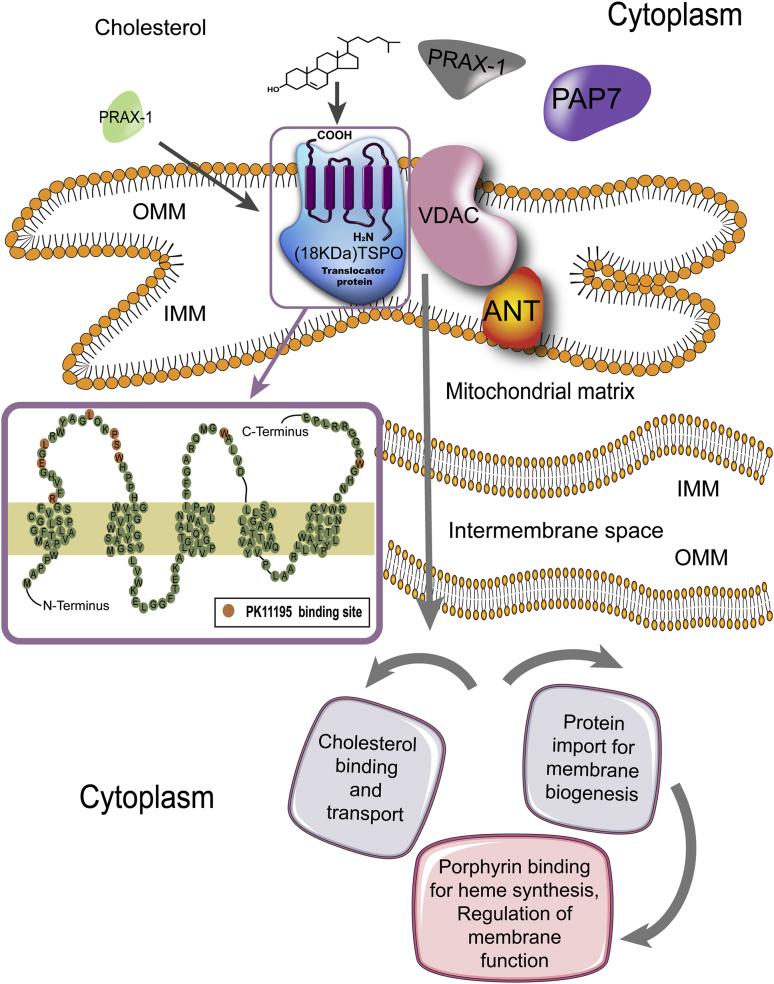

Figure 1.

TSPO structure and function. TSPO is mainly expressed in the OMM with five transmembrane alpha helix domains. The topology of TSPO in the membrane is amplified, with amino acids involved in the binding site of PK11195 highlighted. The PK11195 binding site includes the residues R24, E29, L31, L37, P40, S41, W42, W107 and W161. TSPO generally functions as a monomer, but can also form compounds with itself or other proteins, such as VDAC and ANT. Furthermore, PBR-associated protein 1 (PRAX-1), and PBR and protein kinase A (PKA) regulatory subunit RIa-associated protein (PAP7) are correlated with TSPO. PRAX-1 and PAP7 could also promote compound formation or cholesterol targeting to TSPO. TSPO has four dominating functions: (1) binding and transporting cholesterol, a critical function in neurosteroid synthesis and bile salt biosynthesis; (2) protein transport for membrane biosynthesis and other important physiological functions including cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis; (3) binding and importing porphyrin for heme biosynthesis; and (4) adjusting mitochondrial functions.

TSPO is responsible for the translocation of cholesterol from the outer to the inner mitochondrial membrane, thereby limiting the rate of neurosteroid biosynthesis11. In addition, TSPO is also involved in other physiological functions including immunomodulation12, mitochondrial metabolism and function13, apoptosis14, cell respiration and oxidative processes15, cell proliferation and differentiation16, protein import17, porphyrin transport and heme biosynthesis18, and ion transport19 (Fig. 1). Under physiological conditions, TSPO is widely distributed throughout the body with the highest concentrations observed in steroidogenic tissues. It is predominantly expressed in the kidneys, nasal epithelium, adrenal glands, lungs, and heart, while organs such as the brain and liver show relatively low expression1. However, TSPO has been shown to be involved in brain ischemia-reperfusion injury20, neurodegenerative diseases21, and other diseases22,23. In the central nervous system (CNS), TSPO expression is strongly upregulated in activated microglial cells by inflammatory stimuli24. Lavisse et al.25 found that reactive astrocytes also overexpress TSPO. Furthermore, activated peripheral macrophages sometimes express TSPO26, so in theory, under conditions of compromised blood‒brain barrier (BBB) peripheral macrophages could infiltrate the brain. Abnormal TSPO expression in glial cells27,28 is implicated in the progression of neuropsychiatric disorders involving neuroinflammation including Alzheimer's disease (AD), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), Parkinson's disease (PD), and multiple sclerosis (MS)27,28. As a result, TSPO is considered to be a promising biomarker for neuroinflammation that could be used for monitoring the effectiveness of anti-inflammatory therapies29,30.

Positron emission tomography (PET) is a noninvasive imaging technology which can provide quantitative biological information in vivo, and plays an important role in disease diagnosis, therapy assessment and drug development31, 32, 33. Unlike anatomical imaging techniques such as X-ray, ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), PET offers the real-time biological processes in molecular level based on a specific ligand bearing a positron-emitting radionuclide (“PET tracer”), which makes this technology with high sensitivity and excellent tissue penetration34. The commonly used positron radionuclides consist of 11C (t1/2 = 20.4 min),18F (t1/2 = 109.7 min), 68Ga (t1/2 = 67.6 min), 64Cu (t1/2 = 12.8 h) and 89Zr (t1/2 = 78.4 h)35, the former two isotopes are most widely used for labeling small organic molecules36,37, while the metal radionuclides are more feasible to label peptide38,39, antibody40,41 and nano materials42. Another advantage of PET is that the amount of radiotracer used in imaging studies is very low (10−6‒10−9 g; microdosing), which is feasible to evaluate the biological process without pharmacological effects, as well as to enable rapidly translation of promising radiotracers from bench work to phase 0 clinical trials43.

A number of radioligands have been developed for visualizing TSPO biodistribution and expression in physiological and pathological conditions, as well as for determining the relationship between TSPO quantification and disease progression44. Representative TSPO PET tracers advancing into human brain imaging study as well as the clinical data are summarized in Supporting Information Table S1 (the corresponding structures of tracers are depicted in the following figures) [11C]PK11195, the first prototypical PET tracer for TSPO, has historically been the most widely used to monitor neuroinflammation in various neurological disorders45, 46, 47, 48. However [11C]PK11195 has a relatively low signal to noise ratio (SNR) due to high nonspecific binding, and the short half-life of 11C (20.4 min) limits widespread transportation and clinical trials. Therefore, there have been many efforts to develop new radioligands with improved pharmacokinetics and imaging quality, and several next-generation TSPO radioligands have been developed for more accurate visualization of TSPO49, 50, 51, 52, 53. Although these new PET tracers show improved SNR, there is a limitation that there is variability in TSPO binding potential (BP) among individuals due to a single nucleotide polymorphism in the TSPO gene54. The human TSPO gene is located on chromosome 22q13.3, consists of four exons, and encodes 169 amino acids55. Recent studies discovered a single-nucleotide polymorphism (rs6971) in exon 4 of the human TSPO gene that results in a nonconservative alanine to threonine substitution, influencing the TSPO protein's ligand binding affinity56. The rs6971 polymorphism can lead to three distinct binding statuses: high-, mixed-, and low-affinity binders. The main form, Ala/Ala, is correlated with high-affinity binding (HAB), while the Ala/Thr form has mixed-affinity binding (MAB), and the Thr/Thr form has low-affinity binding (LAB)57. This gene polymorphism can influence the binding affinities of almost all of the second-generation TSPO tracers, requiring inclusion of the HAB and MAB distinction as a covariate in analyses, and exclusion of LAB participants in human clinical studies. The frequency of the polymorphisms varies by ethnic background such that the LAB frequency ranges from approximately 1 in 10 Caucasians to about 10-fold less in East Asians (http://hapmap.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). Therefore, the development of novel radioligand candidates that are insensitive to the rs6971 polymorphism, namely third-generation PET tracers, would enable greater inclusion of participants for TSPO imaging in human studies.

Here, we assess the most recent developments in TSPO PET tracers, as well as recent pharmacological developments, such as new-generation PET tracers. In this review, we will introduce the newest TSPO radioligands and discuss the challenges in TSPO radioligand development. Since there are no clinically approved TSPO PET tracers, we will also focus on new opportunities for radioligand development in alignment with recent drug discovery campaigns.

2. TSPO in the brain

Microglia are resident macrophages in the brain as well as resident CNS immune cells that form the first line of defense against invading pathogens and other harmful agents. Approximately 15% of the non-neuronal cells in the CNS are microglia58. They exquisitely monitor the brain milieu and can rapidly produce factors that affect surrounding neurons and astrocytes. Activated microglia and astroglia are often important participants in neuroinflammation59. Under physiological conditions, microglia usually exhibit a resting phenotype in which they are highly sensitive to changes in the brain microenvironment and can quickly switch to an activated phenotype in response to infection or injury60,61. After activation, microglia proliferate and migrate to the injured part, adopting typical morphological and functional properties62. The activated microglia exhibit morphological changes which may include shortening and thickening of their cellular processes, undergoing hypertrophy of the cell body or even changing to an ameboid state. In the resting state, microglia can secrete various growth factors and produce factors that support tissue maintenance63,64. When injury and/or inflammatory factors are released, microglia change from a resting state to an activated state. This activated state can include pro-inflammatory or anti-inflammatory functions or a combination of both65.

Previous studies have observed increased TSPO expression levels under neuroinflammatory conditions28,66,67. TSPO is highly expressed in activated microglia, but expressed at much lower levels in ‘‘resting’’ or surveying microglia found mainly in the gray matter27,28. The dramatic upregulation of TSPO has been reported to coincide with microglial activation in response to brain injury or inflammation68,69. Thus, TSPO has been considered a hallmark of neuroinflammation.

The increase of TSPO levels after the injury of brain are mainly occurred in the primary or secondary regions of injury that express activated glial cells. Importantly, TSPO can be visualized and quantified using in vitro and in vivo imaging techniques. TSPO PET tracers have been used to both improve knowledge about the effect of neuroinflammation on CNS disorders and to the efficacy of new anti-inflammatory treatment strategies. Currently, TSPO PET imaging is the most widely used in vivo method for inferring on the status of microglial activation. Direct evidence for an innate inflammatory response in AD was described nearly 20 years ago70, and subsequent studies have demonstrated neuroinflammation in PD71, ALS72,73, MS74, major depressive disorder (MDD)30, obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD)75 and a growing number of other nervous system pathologies. Previous studies in rodents after lipopolysaccharide (LPS) or toxins have also reported that dramatic upregulation of TSPO levels are correlated with microglial activation in response to brain injury or neuroinflammation76,77 although in postmortem investigations in humans both activated microglia and astroglia may overexpress TSPO27,28.

3. Development of radioligands targeting TSPO

The development of PET tracers for brain imaging usually commence with medicinal chemistry and pharmacological screening of potential TSPO ligands aimed for high binding affinity and high selectivity78, 79, 80. After carefully exploration of the structure–activity relationship (SAR), the candidate PET ligand is selected and amenable for 11C/18F radiolabeling, specifically focusing on the preparation of precursors, optimization of labeling conditions, as well as translational study using automatic synthesis modules. The radiolabeling reaction of each TSPO PET tracer is depicted in Supporting Information Scheme S1. 11C labeling was conventionally conducted in the presence of base such as NaOH, NaH or tetrabutyl ammonium hydroxide (TBAH), with phenol or amide as the precursor. The labeling was straightforward, and the 11C-labeled PET tracers were obtained in 9%–85% RCYs. In terms of 18F-labeled TSPO PET tracers, SN2 displacement was often employed, sometimes with radioactive prosthetic group (i.e., BrCH2CH218F and 18F–FCH2I). By now, only two TSPO PET tracers were reported with Csp2-18F motif, in which spirocyclic iodonium ylide method was employed81. The radiofluorination yields were comparable with 11C labeling. All TSPO PET tracers possessed good molar activities (Am, >1 Ci/μmol), which was an essential requirement for brain imaging.

3.1. The first TSPO PET tracer

The prototypical PET tracer for TSPO was 1-(2-chlorophenyl)-N-[11C]methyl-N-(1-methylpropyl)-3-isoquinolinecarboxamide ([11C]PK11195 [11C]1), developed more than 2 decades ago. PK11195 was the first non-benzodiazepine-type compound that was a selective antagonist for TSPO. It is an isoquinoline carboxamide discovered and named by a French company, Pharmuka, in 198482. [11C]1 was initially used as a racemate with high affinity (inhibition constant [Ki] = 9.3 nmol/L) in rat and selectivity to TSPO83. However, further studies in rats suggested that the R-enantiomer ([11C](R)1) binds with a 2-fold greater affinity than the corresponding S-enantiomer84. The binding affinity of [11C](R)1 is 3.5–4.5 nmol/L in rhesus and 2.1–28.5 nmol/L in human85. [11C]1 has high lipophilicity (logD = 3.97), which likely results in high levels of non-specific binding and relatively poor specific binding. For example, the ratio of specific to nonspecific binding of [11C](R)1 in human brain was determined to be only about 0.2–0.586. As the first PET tracer for TSPO [11C]1 has several disadvantages including a short half-life (20 min), relatively low brain uptake, a poor metabolic profile, and high levels of nonspecific binding resulting in a low SNR, all of which severely limit its widespread clinical use.

Parbo et al.87 demonstrated that BP of [11C](R)1 and the level of amyloid load in AD patients were positively correlated at a voxel level within the frontal, parietal and temporal cortices [11C](R)1 PET imaging also indicated that cortical distribution of increased inflammation overlapped with amyloid deposition in a multitude of amyloid positive mild cognitive impairment (MCI) patients. In another study, Fan et al.88 further found that there was significant correlation between increased [11C](R)1 BP and reduced glucose metabolism in AD, MCI, and PD dementia (PDD) subjects. Cortical BP of [11C](R)1 were negatively associated with mini-mental state examination (MMSE) in both AD and PDD patients. Kübler et al.89 also suggested that the BP of [11C](R)1 was significantly increased within the subregions of the caudate nucleus, putamen, pallidum, precentral gyrus, orbitofrontal cortex, presubgenual anterior cingulate cortex, and the superior parietal gyrus in patients with the parkinsonian phenotype of multiple system atrophy (MSA) compared with healthy controls. Passamonti etal.90 found that in progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) patients, the BP of [11C](R)1 within the subregions of thalamus, putamen, and pallidum were significantly elevated compared with controls. They also indicated that in AD patients, BP of [11C](R)1 in the cuneus/precuneus associated with episodic memory impairment, while in PSP patients [11C](R)1 binding within the subregions of the pallidum, midbrain, and pons associated with disease severity. In another study, Gerhard et al.91 demonstrated that the BP of [11C](R)1 within the subregions of the caudate nucleus, putamen, substantia nigra, pons, pre- and post-central gyrus, and the frontal lobe was significantly increased in corticobasal degeneration (CBD) patients compared to the healthy controls, which may help to characterize the underlying disease activity in CBD patients. Cagnin et al.92 further suggested that the increased BP of [11C](R)1 in frontotemporal dementia (FTD) patients was mainly presented in the typically affected frontotemporal brain regions, which indicated that the presence of microglial activation reflecting progressive neuronal degeneration. Iannaccone et al.93 further studied [11C](R)1 PET imaging in Lewy body dementias(DLB) patients. They found that the increased BP of [11C](R)1 in DLB and PD patients was mainly presented in the substantia nigra and putamen. Moreover, substantial additional microglia activation in several associative cortices was found in the patients with DLB.

3.2. TSPO PET tracers with improved binding specificity and brain uptake

Due to the above-mentioned limitations of [11C]1, development of novel radioligands with greater binding specificity and higher brain uptake was pursued. More than 50 novel PET tracers for TSPO have been reported, including [11C]PBR28 [11C]DAA1106 [11C]DPA713 [11C]vinpocetine [11C]DAC [18F]PBR06 [18F]DPA-714 [18F]PBR111 [18F]FEPPA, and others94, 95, 96, 97, 98, 99, 100, 101, 102 (Fig. 2). In preclinical and early clinical studies, many of these radioligands have been shown to bind to TSPO with improved bioavailability and SNR, lower nonspecific binding, and higher non-displaceable binding potential (BPND) than [11C]1. Other recent reviews have summarized the development of these radioligands103,104. Here we will focus on the radioligand design, radioisotope labeling, pharmacokinetics, and PET imaging performance in neurological diseases.

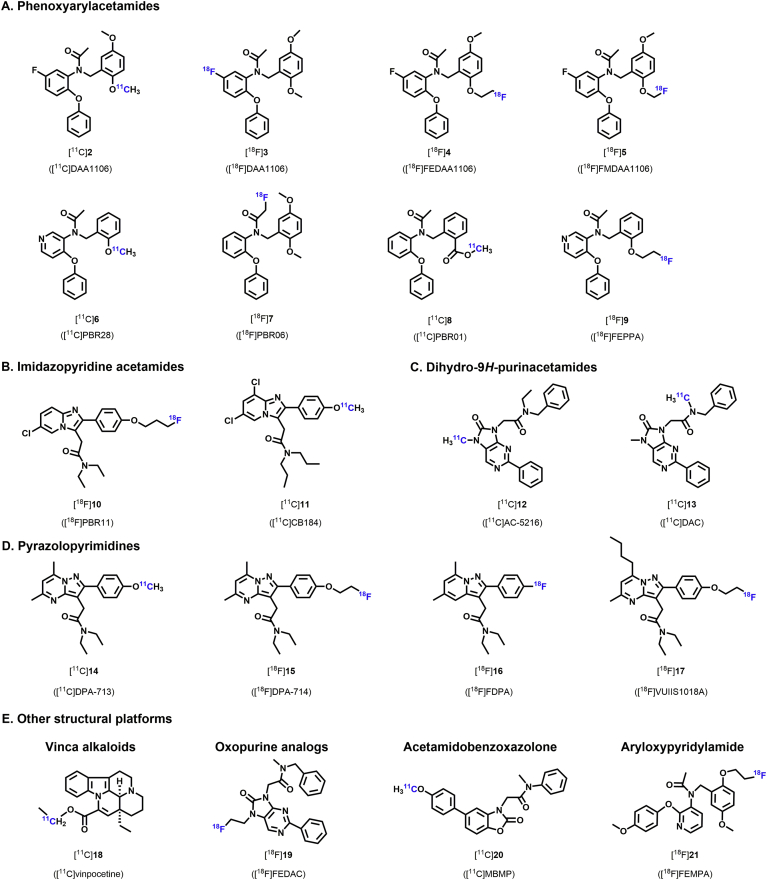

Figure 2.

TSPO radioligands with novel chemical structures.

3.2.1. Phenoxyarylacetamides

In 2012, Wang et al.105 reported the automatic radiosynthesis and evaluation of a potent and selective TSPO radioligand, N-(2,5-dimethoxybenzyl)-N-(5-fluoro-2-phenoxyphenyl)acetamide ([11C]DAA1106 [11C]2, Fig. 2), derived from a novel class of phenoxyarylacetamide with high affinity and specificity for TSPO106. The binding affinity (Ki) of [11C]2 toward TSPO was 0.043 nmol/L in rat brain and 0.188 nmol/L in monkey brain107. [3H]DAA1106 dissociation constant (KD) were 5- to 6-fold lower than [3H](R)-PK11195 in different rat brain regions. Because binding affinity is negatively correlated to the KD, these data demonstrate that [3H]DAA1106 has higher affinity for TSPO than [3H](R)-PK11195106. [11C]2 also has a reasonable lipophilicity (logD = 3.65), which could partially contribute to its good BBB penetration. In mice, high [11C]2 uptake was observed in the brain during scanning (2.1%–3.5% ID/g), about 1.5–2 fold higher than [3H]PK11195. The highest uptake of [11C]2 was observed in the olfactory bulb [4.2% ID/g at 30 min post-injection (p.i.)], and is commensurate with the highest density of TSPO in the mouse brain, as well as in the cerebellum (3.5% ID/g at 30 min p.i.). Moreover, additional studies demonstrated that [11C]2 TSPO binding was specific by pre-treatment with DAA1106 and PK11195 prior to in vivo imaging with [11C]2 in both healthy mice and in kainic acid (KA)-lesioned rats107,108. Zhang et al.109 found that [11C]2 plasma radio-metabolites are much more polar than [11C]2 and may not cross the BBB in mice [11C]2 has been widely studied in conditions associated with neuroinflammation. For example, comparing with [11C](R)1 [11C]2 showed greater retention period at the region of injury in rats with traumatic brain injury (TBI) as evaluated by in vitro autoradiography110. These results showed that [11C]2 binds to TSPO with higher affinity, indicating that [11C]2 may be a better ligand than [11C](R)1 for in vivo PET imaging of TSPO in TBI.

In 2009, Gulyás et al.111 used [11C]2 for in vitro autoradiography studies of human postmortem brain slices obtained from AD patients and age-matched controls. They found that specific binding was significantly higher in the hippocampus, the temporal and parietal cortices, the basal ganglia, and the thalamus of AD brains, suggesting that [11C]2 can effectively label activated microglia with upregulated TSPO in AD111. In another study, mean BP was significantly increased in all measured regions, including the dorsal and medial prefrontal cortices, lateral temporal cortex, parietal cortex, occipital cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, striatum, and cerebellum, as compared to healthy controls112. [11C]2 was used to measure an increase in TSPO binding in the brains of AD patients at a relatively early stage, suggesting widespread upregulation of TSPO even in early AD and further supporting the superiority of [11C]2 over [11C]1. Unfortunately, the study did not directly compare [11C]2 and [11C]1 in the same subjects112. Similarly, Yasuno et al.113 demonstrated that [11C]2 binding to TSPO was also markedly increased throughout many brain regions in MCI subjects compared with healthy controls. There was no significant difference in BP between MCI and AD patients. The high [11C]2 binding in MCI patients suggested that microglial activation may occur before the onset of clinical dementia symptoms. Further studies are needed to verify this finding.

The chemical composition of DAA1106 includes a fluorine atom. Since 18F has several favorable properties such as a relatively longer half-life (109.7 min) as well as an excellent decay profile (97% β+ emission) and positron energy (650 keV), labeling DAA1106 with 18F seems to be a logical step for developing a superior TSPO radioligand for PET imaging [18F]3 showed a very high affinity for TSPO in rat brain105. Subsequent [18F]3 biodistribution studies found low radioactivity uptake in bone without serious defluorination in mice. Furthermore, greater than 96% of the total radioactivity in the mouse brain at 60 min after radioligand injection was found to be unmetabolized radioactivity, attributed to parent [18F]3. High [18F]3 uptake during PET imaging (1.9 ± 0.3% ID/g) was observed in ischemic areas of rat brains as compared to the contralateral side. Additionally, pre-treatment with PK11195 demonstrated that [18F]3 had higher TSPO specificity in the ischemic brains114.

FEDAA1106(N-(5-fluoro-2-phenoxyphenyl)-N-(2-(2-fluoroethoxy)-5-methoxybenzyl) acetamide) is a fluorinated ethyl analogue derivative of DAA1106. Recently [18F]FEDAA1106 ([18F]4, Fig. 2) has been investigated as a potential radioligand to visualize TSPO in vivo using PET imaging. The binding affinity (Ki) of [18F]4 toward TSPO in rat brain slices was 0.078 nmol/L, and the lipophilicity (logD = 3.81) was higher than [11C](R)1 (logD = 2.78)115. Further studies demonstrated high [18F]4 uptake (2.2%–4.9% ID/g) in the mouse brain, about 1.3–1.6-fold higher than [11C]2 and 2‒3-fold higher than [11C](R)1116. The [18F]4 uptake in bone was very low (0.31% dose/g at 30 min p.i. and 0.09% dose/g at 120 min p.i.), which indicated desired stability of the fluoroethyl group against defluorination in vivo. Additional PET studies in monkey indicated a high activity attributed to [18F]4 in the occipital cortex 2 min after injection that remained at nearly the same level during the entire PET measurement (180 min). This was 1.5 times higher than [11C]2 and 6 times higher than [11C](R)1 (at 30 min p.i.). Additionally, pretreatment with PK11195 showed that the [18F]4 binding in the occipital cortex was specific. Radiometabolite analyses found that only [18F]4 was detected in monkey brain homogenates with no evidence of any radioactive metabolites (at 60 min p.i.). The [18F]4 metabolite profile was similar to [11C]2 in vivo. Another analogue of DAA1106 [18F]FMDAA1106 ([18F]5, Fig. 2) was also synthesized and evaluated. The affinity of [18F]5 for TSPO was found to be similar to [11C]2. However [18F]5 displayed high uptake in bone in mice and monkey, indicating that this radioligand was unstable for in vivo defluorination and not a useful PET radioligand116.

Recently [18F]4 PET imaging has been used to investigate neurological diseases associated with neuroinflammation117. Varrone et al.118 demonstrated that the distribution volume (VT) and BP of [18F]4 in brains was not significantly different in AD and healthy controls. These data suggested that TSPO imaging with [18F]4 was not a viable tool for monitoring microglial activation in AD. Similarly, another study found no significant differences in the BPND or VT values between MS patients and controls, demonstrating that [18F]4 could not be used to monitor MS brain lesion sites119. We speculate that the negative results from the above studies are likely due to the high nonspecific binding of [18F]4, as well as genetic variability in TSPO binding in human brains.

PBR28, an analog of DAA1106, is a promising second-generation TSPO radioligand [11C]PBR28 ([11C]6, Fig. 2, N-(2-[11C]methoxybenzyl)-N-(4-phenoxypyridin-3-yl)acetamide) was originally developed by Pike and colleagues120,121 [11C]6 showed a high affinity for TSPO in rat (Ki = 0.680 ± 0.027 nmol/L), monkey (Ki = 0.944 ± 0.101 nmol/L), and human (Ki = 2.47 ± 0.39 nmol/L) mitochondria [11C]6 also displayed high lipophilicity (logD = 3.01 ± 0.11)120 and was very stable; 99.8% was unchanged after incubation with rat brain homogenate in saline for 2 h at 37 °C. The radioactivity of this radioligand was rapidly detected in monkey brain, with peak uptake occurring in all examined TSPO-containing regions at 10 min p.i., and then was quickly washed out to a low level. Maximal uptake was 394% standard uptake volume (SUV) in the choroid plexus of the fourth ventricle120. They also found that [11C]6 radioactivity in all examined regions was rapidly and substantially reduced in monkey brain after administration of PK11195, indicating that [11C]6 binding to TSPO was specific. The specific binding of this ligand was greater than 90% of its total uptake in monkey brain121. Another study demonstrated that the specific binding of [11C]6 in monkey cerebellum was about 80-fold higher than [11C](R)1122.

Brown et al.123 further suggested that [11C]6 would cause relatively modest radiation burden in humans, similar to several other 11C-radioligands used for brain imaging [11C]6 has been used as a radioligand to study several neurological diseases associated with neuroinflammation. Oh et al.124 reported [11C]6 PET scans from 11 subjects with MS and 7 healthy volunteers. They found that [11C]6 uptake was significantly increased in focal regions of active inflammation, as proven by gadolinium contrast enhancement, in comparison to the contralateral normal-appearing white matter. Furthermore, the increase in [11C]6 uptake exceeded the appearance of contrast enhancement in MRI of some inflammatory lesions, indicating the important role of early glial activation in MS lesion formation and further confirming that TSPO is an informative biomarker of glial activation or neuroinflammation in MS. Global [11C]6 binding was correlated with disease duration, but not with clinical disability. However, the sample size was relatively small, limiting the translation of these data124. Subsequently, Hirvonen et al.125 also performed [11C]6 imaging in patients with unilateral temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE). Their study demonstrated that [11C]6 uptake in TLE patients was higher ipsilateral to the seizure focus, which consisted of the hippocampus, parahippocampal gyrus, amygdala, fusiform gyrus, and choroid plexus, indicating increased TSPO expression. Further, this asymmetry was more obvious in patients with hippocampal sclerosis. However, a larger sample size is needed to determine the generalizability of these results across different types of epilepsy125. In another study, Gershen et al.29 found that, compared to controls [11C]6 binding in patients with TLE was significantly elevated in both ipsilateral temporal regions and contralateral regions to seizure foci (including hippocampus, amygdala, and temporal pole), suggesting increased TSPO extending beyond the seizure focus and involving both temporal lobes and extratemporal regions. This demonstrated that anti-inflammatory therapy may be important in treating drug-resistant epilepsy. In 2013, Kreisl et al.59 found that [11C]6 binding in patients with AD, but not those with MCI, was significantly higher than controls in cortical brain regions, especially in the parietal and temporal cortices [11C]6 binding inversely correlated with performance in a cognitive function assessment. They demonstrated that neuroinflammation, as defined by elevated [11C]6 binding to TSPO, occurs after conversion of MCI to AD and exacerbates with disease progression. However [11C]6 PET imaging in humans is limited due to TSPO binding affinity differences related to genotype59. In another study, Lyoo et al.126 used an absolute quantitation method (VT/fP, plasma free fraction of radioligands (fP)) to confirm that [11C]6 binding was greater in AD patients than healthy controls in temporo-parietal regions, but not in the cerebellum. The authors then explored the use of the cerebellum as a pseudo-reference region and determined the standard uptake volume ratio (SUVR). SUVR demonstrated greater TSPO binding than absolute quantification and identified one additional TSPO upregulated region, indicating that SUVR analysis may have greater sensitivity. This new analysis needs to be replicated in more AD patients before being widely implemented. In 2016, Kreisl et al.127 examined AD clinical progression and demonstrated that the annual rate of elevated [11C]6 binding in temporo-parietal regions was about 5-fold higher in AD with clinical progression than in patients without progress. They suggested that TSPO may be used as a marker of Alzheimer's progression and response to anti-inflammatory therapies. Since this study had a small sample size the authors subsequently studied TSPO PET imaging in different clinical subtypes of AD, including posterior cortical atrophy (PCA) and amnestic AD128. They found that [11C]6 binding in occipital, posterior parietal, and temporal regions was significantly increased in PCA patients compared with controls. However, in amnestic AD patients [11C]6 binding in inferior and medial temporal cortex was much greater than controls. They suggested that neuroinflammation is also closely correlated with neurodegeneration across different subtypes of AD. However, this study was limited by its relatively low sample size and variability in TSPO binding affinity across subjects.

Recently, TSPO imaging has also been used to investigate other neurodegenerative diseases. For example, Lois et al.129 used [11C]6 PET/MR imaging to study neuroinflammation in Huntington's disease (HD). They reported that [11C]6 binding in the putamen and pallidum was significantly increased in HD patients compared to controls. They also observed that TSPO binding was significantly elevated in the basal ganglia of pre-symptomatic subjects, indicating that neuroinflammation is an early pathological process correlated with subclinical progression of HD. Further, they showed that, in some HD patients, TSPO binding was greater in thalamic subnuclei and brainstem regions associated with visual function, motor function, and motor coordination. The authors assert that [11C]6 PET/MR imaging provides a high signal-to-background ratio and has the potential for clinical evaluation of HD progression, albeit the study had a relatively small sample size129. Other work demonstrated that patients with ALS had greater [11C]6 binding in the precentral gyrus compared to controls130,131. Subsequently, Ratai et al.132 used integrated imaging technologies and found that increased [11C]6 binding in response to glial activation in the precentral gyrus in patients with ALS was co-localized and related to neuronal injury/loss, as monitored by decreased N-acetylaspartate/creatine (NAA/Cr).

Another 2nd-generation TSPO ligand, PBR06, was labeled with 18F, 18F-N-fluoroacetyl-N-(2,5-dimethoxybenzyl)-2-phenoxyaniline ([18F]PBR06 [18F]7, Fig. 2). The half-life of 18F allows for a longer data acquisition period, and may be required to match the pharmacokinetics of the elevated binding density. The binding affinity (Ki) of [18F]7 toward TSPO was 0.30 ± 0.08 nmol/L in monkey brain mitochondrial homogenates and 1.0 nmol/L in human brain tissue [18F]7 also has a very high lipophilicity (logD = 4.01), greater than [11C]6. Elevated lipophilicity may improve BBB penetration, but also tends to increase nonspecific binding in the brain. However [18F]7 and [11C]6 have very similar brain uptake, when corrected by VT/fP133. [18F]7 radioactivity was observed in monkey brains with peak uptake occurring in examined TSPO-containing sites at 27 and 72 min after injection. Maximal binding was 371 ± 89% SUV and occurred in the choroid plexus of the fourth ventricle. Subsequently, the radioactivity slowly washed out [18F]7 also showed no obvious evidence of in vivo defluorination. The radioactivity of unchanged [18F]7 in the brain was very high (>90%) at 30 min p.i. Moreover, the radiometabolites were more hydrophilic than [18F]7. This study also demonstrated that [18F]7 had a very low ratio of TSPO-nonspecific to specific binding in monkey134. [18F]7 has also been widely studied in many neurological disease models. Lartey et al.135 found that after stroke [18F]7 accumulation in mouse brain peaked at 5 min p.i., then decreased gradually, remaining significantly higher in infarct regions than in noninfarct sites. Pre-treatment with PK11195 eliminated the difference in [18F]7 binding between infarct and noninfarct regions. This study demonstrated that TSPO is a potential biomarker of neuroinflammation in mouse stroke models. However, further research in monkeys and humans is needed. In another study, James et al.136 found that [18F]7 binding in 15- to 16-month-old APPL/S mice was much higher in the cortex and hippocampus compared with age-matched wild-types and was well correlated with autoradiography and immunostaining results. The authors suggested that [18F]7 could be a viable biomarker for monitoring TSPO/microglia throughout AD progression and treatment, however, these data need to be replicated in higher species. Subsequently, Simmons et al.137 found that [18F]7 could monitor microglial activation in the cortex, striatum, and hippocampus of R6/2 mice treated by vehicle at a late stage of HD and in BACHD mice at an early mid-stage of symptomatic HD. In both HD mouse models [18F]7 binding could reflect the inhibitory effects of LM11A-31, a P75NTR ligand known to reduce neuroinflammation. Thus [18F]7 is also a potential radiotracer of therapeutic efficacy in HD mice.

Fujimura et al.138 further quantified TSPO using [18F]7 in healthy human brains. They showed that [18F]7 binding could be used to measure TSPO in human brains using 120 min of image acquisition. Although brain radioactivity signal is likely from a mix of radiometabolites, the radio signal of contamination is also very low (<10%). Moreover, Fujimura et al.139 reported that [18F]7 radioactivity in human bone was very low. The effective dose of [18F]7 was 18.5 μSv/MBq in human subjects, a moderate dose compared to other 18F radioligands. In another study, Singhal et al.100 found that [18F]7 and [11C]6 correlated with white matter, but not lesion sites, in MS patients. Their results also demonstrated that, compared with [11C]6, MS-correlated lesional changes detected using [18F]7 had higher clinical relevance; however, their sample size was relatively small.

Both [11C]PBR01 ([methyl-11C]methyl 2-((N-(2-phenoxyphenyl)-acetamido)-methyl)benzoate [11C]8, Fig. 2), and [18F]7 are aryloxyanilide compounds [11C]8 has also been evaluated in monkeys as a potential TSPO radioligand134. The binding affinity (Ki) of [11C]8 toward TSPO in monkey brain mitochondrial homogenates was 0.24 ± 0.04 nmol/L, similar to [18F]7. Both radioligands show high brain uptake. Further, pre-block with PK11195 of both [18F]7 and [11C]8 before PET imaging caused rapid washout of radioactivity in monkey brain, suggesting that binding was highly specific. In fact, both radioligands showed similar clearance, time to peak uptake, and washout rates. However [18F]7 may have greater potential for use in human subjects, as demonstrated by brain radioactivity quantified with standard compartmental models and a higher specific binding.

[18F]FEPPA (N-acetyl-N-(2-[18F]fluoroethoxybenzyl)-2-phenoxy-5-pyridinamine [18F]9, Fig. 2), is a novel 18F-radiolabelled phenoxyanilide, the fluoroethoxy analogue of PBR28. FEPPA had a very high binding affinity (Ki = 0.07 nmol/L) for the PBR in rat mitochondrial membrane preparations and displayed a suitable lipophilicity (logP = 2.99). Wilson et al.79 demonstrated that [18F]9 uptake in rat brain was moderate (SUV 0.6) at 5 min p.i. and slowly washed out (SUV 0.35) at 60 min p.i. The highest radioactivity in rat brain was observed in the hypothalamus and olfactory bulb [18F]9 was quickly metabolized, but no lipophilic metabolites were present and only 5% radiometabolites were observed in the brain. There was some limitation with the blocking studies to assess specific binding of [18F]9 in rat brain due to elevation of circulating radioligands and the lack of a reference region, however the ratio of tissue to plasma was reduced by approximately 97% with administration of cold PBR2879.

[18F]9 was tested in vivo in humans and applied to investigate several neuropsychiatric diseases140. Suridjan et al.141 found that [18F]9 binding was significantly greater in AD patients compared to healthy controls in grey matter areas, including the hippocampus, and the prefrontal, temporal, parietal, and occipital cortices [18F]9 binding was also increased in white matter of AD patients, including the posterior limb of the internal capsule and the cingulum bundle141. Setiawan et al.30 reported elevated TSPO VT during major depressive episodes in the grey matter regions, including the prefrontal and anterior cingulate cortex, a finding replicated with [18F]9 [11C]6 and [11C](R)1 in subsequent studies142, 143, 144, 145, 146. Attwells et al.75 reported elevated TSPO VT in OCD, particularly in the cortico-striatal-thalamic circuit involving the orbitofrontal cortex. Ghadery et al.94 did not observe activated microglia in gray or white matter using [18F]9 PET imaging in PD although additional studies are required to determine the utility of [18F]9 as a radiotracer of microglial activation in neurodegenerative diseases.

3.2.2. Imidazopyridine acetamides

PBR111(2-(6-chloro-2-(4-(3-fluoropropoxy)phenyl)imidazo[1,2-a]pyridin-3-yl)-N,N-diethylacetamide) is a metabolically stable imidazo pyridineacetamide derivative with high binding affinity and selectivity for TSPO147. [18F]PBR111 ([18F]10, Fig. 2) is a potential TSPO radioligand (Ki = 3.7 ± 0.4 nmol/L) and has an appropriate lipophilicity (logP = 3.2 ± 0.1). The highest [18F]10 uptake was 0.2%–0.3% ID/g in rat brain at 15 min p.i., which then rapidly washed out. However [18F]10 uptake in femur was 0.6% and 2.2% ID/g at 15 min and 4 h p.i., respectively, indicating that it may be unstable and defluorinated in vivo. Metabolic analysis demonstrated that, in the rat cortex, 55%–80% of the radioactivity represented [18F]10 at 15 min p.i., which further decreased to 30% at 4 h p.i.148. Moreover, Van Camp et al.149 used in vitro autoradiography and found that [18F]10 binding was significantly increased in α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole propionic acid (AMPA)-lesioned areas in rat brain compared to the control side. Moreover, blockade with an excess of unlabeled PK11195 or PBR111 significantly inhibited binding in the lesioned area. They also observed higher [18F]10 uptake in AMPA-lesioned rat brains than [11C]1 uptake using in vivo PET imaging. Unlabeled PK11195 or PBR111 quickly and fully displaced the radiolabel. However, further preclinical and clinical studies using [18F]10 as a radiotracer of neuroinflammation are needed. Subsequently, Guo et al.150 further investigated [18F]10 in human subjects. Using a 2-tissue compartment model, they concluded that [18F]10 has a high specific binding for TSPO in the healthy human brain in vivo.

[11C]CB184(N,N-di-n-propyl-2-[2-(4-[11C]methoxyphenyl)-6,8-dichloroimidazol[1,2-a]pyridine-3-yl] acetamide [11C]11, Fig. 2), is a new and improved alternative to [11C](R)1. The binding affinity (Ki) of [11C]11 toward TSPO was 0.54 nmol/L, as measured in an in vitro binding study, and lower lipophilicity (logP = 2.06 ± 0.02) compared to [11C](R)1 (logD = 2.78)151. The highest [11C]11 uptake in mouse brain is observed in the olfactory bulb (1.45 ± 0.03% ID/g), cerebellum (1.384 ± 0.091% ID/g), hippocampus (1.225 ± 0.067% ID/g), and pons (1.045 ± 0.102% ID/g) [11C]11 uptake in mouse brain was monitored at 30 min p.i., and the uptake levels were nearly stable from 30 to 60 min p.i. After pre-administration with PK11195, the [11C]11 uptake level was significantly reduced relative to controls in every brain region, indicating that [11C]11 binding specificity is very high in mouse brain tissue. Metabolic analyses demonstrated that the percentages of unchanged parent compound for [11C]11 were 92.7 ± 5.8% in the brain and 36.2 ± 15.5% in the plasma at 30 min p.i.151. Moreover, Vállez Garciaet al.152 evaluated [11C]11 labeling in neuroinflammation. Their study showed greater [11C]11 uptake in the amygdala, olfactory bulb, medulla, pons, and striatum in herpes simplex encephalitis (HSE) rats compared to controls. Similarly, the BP of [11C]11 in HSE rats was significantly higher (P < 0.05) in the amygdala, hypothalamus, medulla, pons, and septum compared with control rats. Their results indicate that [11C]11 is a good alternative radioligand for TSPO PET imaging. However, more studies are need to determine the utility of [11C]11 PET imaging for detection of neuroinflammation in non-human primates and humans.

Subsequently, Toyohara et al.153 found that [11C]11 PET imaging in healthy humans showed quick uptake in the brain followed by rapid clearance during a 90-min dynamic scan [11C]11 was equally distributed in the gray matter and was greatest in the thalamus, followed closely by the cerebellar cortex and elsewhere. Regional differences in [11C]11 binding were small, but the observed [11C]11 binding pattern was in agreement with the TSPO distribution in normal human brain. The effective dose of [11C]11 was 5.9 ± 0.6 μSv/MBq in human subjects154.

3.2.3. Dihydro-9H-purinacetamides

AC-5216 (N-benzyl-N-ethyl-2-(7-methyl-8-oxo-2-phenyl-7,8-dihydro-9H-purin-9-yl)acetamide) is an oxopurine labeled with 11C, and is another new candidate TSPO PET tracer ([11C]12, Fig. 2)155. The binding affinity (Ki) of [11C]12 toward TSPO was 0.297 nmol/L in whole rat brain and the lipophilicity was appropriate (logD7.4 = 3.3)156. Moreover, the TSPO binding site for AC-5216 may be more similar to PK11195 than to other TSPO ligands. The radioligand was observed to promote BBB penetration and enter mouse brain regions at 1 min p.i. In the olfactory bulb and cerebellum [11C]12 radioactivity was greater than 1.3% ID/g at 5 min p.i. The absorption level peaked at 15 min p.i. and then decreased until 60 min p.i. The greatest uptake of [11C]12 was present in the olfactory bulb (2.5% ID/g at 15 min p.i.), and moderate uptake was observed in the cerebellum (1.5% ID/g at 15 min p.i.). Uptake in the occipital cortex of monkey brain was greater than in other brain structures such as the cerebellum, frontal cortex, striatum, and thalamus. Pre-block with AC-5216 or PK11195 could inhibit the maximum uptake of [11C]12 to 30%–40% of the control uptake, indicating specific binding in the monkey brain in vivo [11C]12 radioactivity was also measured in mouse brain homogenate as a minor (<10%) radiometabolite at 60 min p.i.

Subsequently, Yanamoto et al.157 used [11C]12 as a novel TSPO radioligand in a KA-induced neuroinflammatory rat model. They used in vitro and ex vivo autoradiography to demonstrate that [11C]12 radioactivity was significantly elevated in the striatum lesions induced by KA (2- to 3-fold higher than the contralateral striatum). Pre-block with AC-5216 or PK11195 abolished the difference in [11C]12 uptake levels between the lesioned and nonlesioned sides, suggesting that [11C]12 has very high specificity for TSPO157. However [11C]12 needs to be further studied in preclinical and clinical trials of many other neuroinflammatory neurological diseases to determine if it is a viable alternative TSPO radioligand.

DAC is a novel derivative of AC-5216 that can be labeled with 11C by reacting a desmethyl precursor with [11C]CH3I. The binding affinity for [11C]DAC ([11C]13, Fig. 2, Ki = 0.23 ± 0.02 nmol/L) is similar to [11C]12 in rat, however, it has lower lipophilicity (logD = 3.0) compared with [11C]12, indicating that [11C]13 may have higher specificity and faster kinetics158. The greatest observed [11C]13 uptake was 2.24 ± 0.16% ID/g at 1 min p.i. in mouse brain, followed by rapid clearance. Low levels of radiometabolites of [11C]13 were detected in the mouse brain (<5%) at 60 min p.i. Yanamoto et al.158 demonstrated that [11C]13 binding in KA-lesioned rats was greater in the lesioned striatum compared to control striatum in vivo, similar to [11C]12. Pre-block with DAC or PK11195 significantly decreased [11C]13 uptake in the lesioned striatum to levels similar to the control side. Moreover [11C]13 TSPO binding was 1.8-fold higher in the lesioned striatum than in the contralateral striatum, as measured by in vitro autoradiography. In another study, Yui et al.99 reported that early infarction with a slight TSPO expression elevation in ischemic rat brains could be measured with [11C]13 PET imaging with very high molar activity (average 4060 GBq/μmol). However, binding was not observed with low molar activity of [11C]13 (37 GBq/μmol), which is consistent with the in vitro autoradiography results. However, neuroinflammation could be observed in the rat brain 4 days after ischemia using specific activity (SA) [11C]13. Pre-block with AC-5216 or PK11195 diminished the difference in radioactivity between the ipsilateral and contralateral sides, suggesting that the increased radioactivity in the infracted regions was specific to TSPO99. However [11C]13 imaging for TSPO needs to be confirmed in preclinical and clinical studies.

3.2.4. Pyrazolopyrimidines

N,N-Diethyl-2-[2-(4-methoxyphenyl)-5,7-dimethyl-pyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidin-3-yl]-acetamide (DPA-713) is a novel pyrazolopyrimidine ligand for TSPO. DPA-713 labeling with 11C can be performed by O-alkylation of a phenolic derivative (N,N-diethyl-2-[2-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-5,7-dimethyl-pyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidin-3-yl]acetamide) with [11C]CH3I to produce [11C]DPA-713 ([11C]14, Fig. 2). The radioligand displayed high affinity in rat (Ki = 4.7 nmol/L), mouse (Ki = 1.3 nmol/L), and human (Ki = 15.0–66.4 nmol/L)85,159 [11C]14 also has high lipophilicity (logD = 2.4). In Papio anubis baboon brains [11C]14 radioactivity peaked at 20 min and remained constant during scanning. Pre-injection with PK11195 (5 mg/kg) successfully decreased the radioactivity by 70% at 60 min throughout the whole brain, indicating that [11C]14 binding in the baboon was specific for TSPO160 [11C]14 has been widely used as a TSPO radioligand to study neuroinflammation. Boutin et al.161 found that [11C]14 showed a greater difference between healthy and damaged brain parenchyma compared with [11C]1 (2.5 ± 0.14- vs. 1.6 ± 0.05-fold increase, respectively) in an AMPA induced model of neuroinflammation in rats [11C]14 had a better SNR ratio than [11C]1 due to higher binding specificity161,162. Chaney et al.163 used PET imaging to demonstrate that [11C]14 uptake was markedly increased in the ipsilateral versus contralateral hemispheres in distal middle cerebral artery occlusion (dMCAO) mice. Elevated radioactivity was also measured in the ipsilateral hemisphere of dMCAO when compared with sham mice. Similarly, using ex vivo autoradiograph, elevated [11C]14 radioactivity was observed in infarcted tissue compared to surrounding healthy brain tissue163. Recently, Chaney et al.164 found that [11C]14 uptake in mice with ischemic stroke was significantly elevated in infarcted brain tissue compared to contralateral brain regions at both acute and chronic time-points. Further, using in vitro autoradiography, increased [11C]14 radioactivity was observed in infarcted versus contralateral brain regions. Importantly, microglial activation [determined by CD68 (cluster of differentiation 68) immunostaining] and [11C]14 PET tracer binding were correlated164. Further studies in non-human primates and humans are needed.

Endres et al.165 first demonstrated that [11C]14 gives a greater brain signal according to dose-normalized time activity curves, indicating that [11C]14 is a potential radioligand for evaluating TSPO binding with PET imaging in human subjects. In another study, they found that the distribution of [11C]14 in human subjects was similar to the known biodistribution of TSPO. Further, dosimetry with [11C]14 is similar to that of [11C]6 in humans [11C]14 also has a similar dose burden compared to other 11C-labeled PET tracers166. Recently, Endres et al.166 demonstrated that selective [11C]14 binding in healthy human brain was much higher than [11C](R)1. Subsequently, Gershen et al.29 found that [11C]14 radioactivity was greater ipsilateral to seizure foci, as compared to contralateral, in patients with TLE. However, the sample size was relatively small. Although [11C]14 has good potential as a TSPO radioligand due to its highly specific binding, we have observed an increased VT over time, consistent with the accumulation of radiometabolites in the human brain50.

N,N-Diethyl-2-(2-(4-(2-fluoroethoxy)phenyl)-5,7-dimethylpyrazolo [1,5-a]pyrimidin-3-yl)acetamide (DPA-714) is a novel 2-phenylpyrazolo [1,5-a]pyrimidineacetamide that is a specific TSPO ligand. It was designed with a fluorine atom in its chemical structure, allowing for labeling with fluorine-18 [18F]DPA-714 ([18F]15, Fig. 2) is a close derivative of [11C]14. The affinity of DPA-714 for TSPO (Ki = 7.0 ± 0.4 nmol/L) is lower than DPA-713 in rat. DPA-714 also has a high lipophilicity (logD = 2.44), similar to DPA-713167. James et al.167 evaluated the biodistribution of [18F]15 in rodents and baboon and found that [18F]15 uptake in rat bone was very low, indicating this radioligand is stable against defluorination in vivo. Similarly [18F]15 is capable of penetrating the BBB and accumulating in the baboon brain. The binding of [18F]15 in baboon brain could also be successfully blocked by PK11195, indicating TSPO specific binding. Further [18F]15 radiometabolites were negligible in rat brain (<3% at 30 min p.i.)168. James et al.167 found that [18F]15 uptake in a quinolinic acid (QA)-lesioned rat brain model was significantly increased in the ipsilateral striatum and reduced after pre-block with PK11195. In one study, Doorduin et al.169 compared the radioactivity of [18F]15 [11C]14, and [11C](R)1 in a rat model of herpes encephalitis. They showed that specific uptake of [18F]15 and [11C]14 was higher than [11C](R)1 in infected brain areas. Chauveau et al.162 further directly compared the uptake of [18F]15 [11C]14, and [11C](R)1 in a unilateral, striatal AMPA-lesioned rat model. They reported that [18F]15 performed better than [11C]14 and [11C](R)1 due to the greatest ipsilateral to contralateral uptake ratio and the highest BP. Moreover, the ability to label DPA-714 with 18F, the preferred PET isotope, supports its dissemination and clinical use162. Thomas et al.170 demonstrated that [18F]15 PET signal in a rat model of subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) was correlated to the degree of bleeding, suggesting that [18F]15 PET imaging could be used to improve SAH management in human patients. In another study, Gargiulo et al.171 used high-resolution PET/CT imaging and reported increased [18F]15 binding in the brainstem of transgenic SOD1G93A mice, an ALS mouse model. The brainstem is a region known to have significant degeneration and activated microglia in ALS. Thus [18F]15 might be a suitable marker to evaluate microglial activation in the SOD1G93A mouse model171 [18F]15 PET imaging was also investigated in other neurological diseases associated with neuroinflammation. Miyajima et al.172 monitored [18F]15 uptake with PET imaging and found that it was markedly increased before selective neuronal loss (SNL) in an ischemic stroke rat model, a change that was also observed by ex vivo autoradiography. Tan et al.173 used [18F]15 PET/CT imaging to monitor neuroinflammation and evaluate the therapeutic effect of bone marrow stromal cells (BMSC) in an ischemic stroke rat model, indicating that [18F]15 has highly potential for clinical application. Additionally, Nguyen et al.174 reported that [18F]15 binding in a mouse model with mesial TLE peaked on Day 7, which is mostly correlated with microglial activation, whereas reactive astrocytes become the main TSPO expression cells after 14 days. They demonstrated that TSPO has great potential as a longitudinal imaging biomarker and could be used to determine the therapeutic window in epilepsy, as well as to monitor the response to therapy174.

In healthy human subjects, Arlicot et al.175 measured the highest cerebral [18F]15 uptake at 5 min p.i., followed by two decreasing phases: a promoted washout (5–30 min) and then a slower phase. They concluded that [18F]15 is a potential PET tracer with good in vivo stability and biodistribution and an acceptable estimated effective dose175. Recently [18F]15 PET imaging has been widely used to study AD. Golla et al.176 demonstrated a small but significant difference in [18F]15 BPND between AD patients and healthy subjects; however, the sample size was very small. Subsequently, Hamelin et al.177 performed [18F]15 PET imaging in more AD patients. They found that temporo-parietal cortex [18F]15 uptake was greater in AD patients that were high and mixed affinity binders as compared to controls, particularly at the prodromal stage. Moreover, TSPO binding was related with MMSE scores and grey matter volume, and with Pittsburgh compound B binding177. Similarly, Hamelin et al.101 found that [18F]15 binding was significantly increased in patients with AD compared to controls both at prodromal and demented stages. They also observed that the change in [18F]15 uptake over time was positively correlated with three clinical outcome measures (Clinical Dementia Rating, MMSE, hippocampal atrophy), indicating that increased neuroinflammation (compared to the initial PET imaging) was associated with negative clinical AD progression. However, various factors may influence disease progression differently among different patients rather than across disease stages101. Subsequently, Hagens et al.178 further demonstrated that [18F]15 could be used to monitor increased focal and diffuse neuroinflammation in progressive MS patients, but observed that the differences were most pronounced in high-affinity binders.

N,N-Diethyl-2-(2-(4-[18F]fluorophenyl)-5,7-dimethylpyrazolo [1,5-a]pyrimidine-3-yl)-acetamide ([18F]FDPA [18F]16, Fig. 2), is a fluorine-containing pyrazolopyrimidine and fluoroaryl derivative of [18F]15 that has a fluorine atom located on the aromatic moiety, and is also a potential PET tracer. FDPA has a higher binding affinity (Ki = 2.0 ± 0.8 nmol/L) than DPA-714, and [18F]16 also has appropriate lipophilicity (logD = 2.34 ± 0.05)179. [18F]16 uptake in mouse brain was moderate (3.69% ID/g) at 2 min p.i., and the radioactivity washout was also reasonable (1.15% ID/g) at 45 min p.i. Moreover, bone uptake was negligible (<1% ID/g), indicating that little or no defluorination occurred in vivo in mice. Wang et al.179 further studied [18F]16 PET imaging in neuroinflammation models. Using a rat ischemia model, they demonstrated that maximum [18F]16 uptake occurred at the ischemic site and reached a peak of 1.20 SUV at 10 min p.i. After pre-treatment with PK11195, the PET signal was significantly reduced by ca. 80%, indicating high specificity of [18F]16 binding in vivo. Moreover, they found that [18F]16 could easily cross the BBB. And in the APP/PS1 mouse mode, they found that [18F]16 increased to 1.50 ± 0.13 SUV at 3 min p.i., indicating 1.6-fold higher uptake and slow washout compared to age-matched controls. They obtained similar results in ischemic rat brains and APP/PS1 mouse brains using in vitro autoradiography179. In another study, Keller et al.180 showed that [18F]16 radioactivity in APP/PS1 mouse brains was substantially elevated with age using in vivo PET imaging and in vitro brain autoradiography. They also observed significant differences in binding between wildtype and transgenic animals in vivo at 9 months and ex vivo at 4.5 months. After pre-block with PK11195 [18F]16 uptake was significantly decreased in all brain regions studied180. PET imaging of [18F]16 has not yet been translated to higher species.

2-(7-Butyl-2-(4-(2-[18F]fluoroethoxy)phenyl)-5-methylpyrazolo [1,5-a]pyrimidin-3-yl)-N,N-diethy-lacetamide ([18F]VUIIS1018A [18F]17, Fig. 2), is a novel analog of [18F]15 that features a 700-fold higher in vitro binding affinity for TSPO than [18F]15. [18F]17 exhibits an exceptional high TSPO binding affinity in vitro study (IC50 = 16.2 pmol/L)181. [18F]17 has a high lipophilicity (logD = 3.74 ± 0.01), but, unlike [18F]15, its lipophilicity is slightly higher than the appropriate range (logD = 1.0–3.5)78. The lipophilicity of [18F]17 needs to be reduced for PET imaging in the brain. Low [18F]17 radioactivity was observed (<1.0% ID/g) in healthy mouse brains at all time points, which is consistent with the normal TSPO distribution. Low uptake (1.6% ID/g) was also observed in the femur at 1 min p.i., which increased slightly (2.1% ID/g) at 60 min p.i., indicating that there was no significant defluorination in vivo. Metabolite analysis showed that 95.7 ± 3.0% and 86.2 ± 2.1% of intact [18F]17 remained in the brain at 30 and 60 min p.i., respectively, which is greater than the ratio of intact [18F]15 observed in brain. They further evaluated the radioligand using a focal cerebral ischemic rat model. The results demonstrated that [18F]17 uptake substantially increased on the ischemic side compared to the contralateral side. After blocking with unlabeled VUIIS1018A and PK11195, the radioactivity on the ischemic side of the brain was markedly decreased. They observed the same trend using in vitro autoradiography78. No translational imaging data has been reported in primates or humans.

3.2.5. Vinca alkaloids

Vinpocetine is a vinca alkaloid compound widely utilized in the prevention and therapy of cerebrovascular disorders. It was developed as a PET tracer labeled with 11C and has good pharmacokinetic characteristics and high affinity to TSPO. Gulyás et al.182 performed a distribution study of [11C]vinpocetine ([11C]18, Fig. 2) in a cynomolgous monkey and showed that [11C]18 could rapidly enter the brain [11C]18 radioactivity was heterogeneously distributed among different brain regions and was greatest in the thalamus, the basal ganglia, and certain neocortical regions.

[11C]18 binds to TSPO in brain tissue with low affinity (IC50 = 0.2 μmol/L)104. Subsequently, Gulyás et al.183 performed [11C]18 imaging in healthy human subjects and reported rapid [11C]18 uptake in the brain. Radioactivity varied among different brain regions, with the greatest regional uptake in the thalamus, upper brain stem, striatum, and cortex, suggesting that [11C]18 binding was specific for TSPO. A PET imaging study in four MS patients demonstrated that global brain [11C]18 uptake significantly surpassed [11C]1 radioactivity, indicating that [11C]18 is superior to [11C]1184. In contrast, Gulyás et al.185 observed no significant differences in [11C]18 signal between AD patients and age-matched control subjects. In another study, Gulyás et al.98 suggested that [11C]18 uptake in post-stroke patients was higher in the peri-infarct zone compared with the ischemic core; however, the difference was not significant. Additionally, no significant differences in BP were observed between [11C]18 and [11C]1 in any of the standard regions. This is likely due to the low binding affinity of [11C]18 for TSPO, which may limit further clinical use.

3.2.6. Oxopurine analogs

N-Benzyl-N-methyl-2-[7,8-dihydro-7-(2-18F-fluoroethyl)-8-oxo-2-phenyl-9H-purin-9-yl] acetamide ([18F]FEDAC [18F]19, Fig. 2), is an 18F-labeled oxopurine analog. The binding affinity (Ki) of [18F]19 toward TSPO was 1.34 ± 0.15 nmol/L in vitro, and [18F]19 had an appropriate lipophilicity (logD = 3.1) 186. [18F]19 showed high uptake (>1% ID/g) in the mouse brain, and [18F]19 radioactivity ranged from 1.33 ± 0.13 to 2.18 ± 0.33 in mouse bone, suggesting that little or no defluorination occurred. The maximum [18F]19 uptake in the monkey brain was in the occipital cortex at about 20 min p.i., similar to [11C]12, and low accumulation of radioactivity was observed in the skull, suggesting little or no defluorination occurred in vivo. Metabolic analysis in brain homogenate demonstrated that 75% of [18F]19 was intact at 30 min p.i.187. Yanamoto et al.188 found that [18F]19 uptake in rat brain was substantially elevated in KA-lesioned striatum compared with non-lesioned striatum, indicating that [18F]19 is a potential PET tracer for TSPO imaging. Subsequently, Yui et al.187 evaluated [18F]19 in the ischemic rat brain. They found that [18F]19 binding in the ischemic rat brain in vivo was significantly increased on the ipsilateral side compared with the contralateral side. Blocking studies with an excess of AC-5216 or PK11195 abolished the difference in radioactivity between the contralateral and ipsilateral sides. Similar results were also obtained by ex vivo autoradiography of infarcted rat brains187. Further investigation into the use of [18F]19 imaging to detect neuroinflammation in the primate and human brain is currently underway.

3.2.7. Acetamidobenzoxazolone

2-[5-(4-Methoxyphenyl)-2-oxo-1,3-benzoxazol-3(2H)-yl]-N-methyl-N-phenylacetamide (MBMP) is an acetamidobenzoxazolone skeleton labeled with 11C and is a new candidate TSPO PET tracer ([11C]20, Fig. 2). The binding affinity (Ki) of [11C]20 toward TSPO was 0.29 nmol/L, and [11C]20 had appropriate lipophilicity (clogD = 3.5)189. [11C]20 rapidly entered the mouse brain. Initial brain uptake was more than 2.0% ID/g at 1 min p.i. in mice, and the maximum uptake was observed in the cerebellum. Metabolite analysis showed that 98.6 ± 0.5% of [11C]20 was intact at 5 min p.i. with one polar metabolite. However, at 60 min p.i., only 65.7 ± 2.7% of [11C]20 in the brain was intact. Subsequently, Tiwari et al.189 evaluated TSPO binding radioligands in an ischemic rat model. Using PET imaging, they observed that [11C]20 and [11C](R)1 binding were obviously higher on the ipsilateral side than on the contralateral side. Blocking with unlabeled MBMP or PK11195 substantially decreased [11C]20 binding on the ipsilateral side. In vitro autoradiography yielded similar results. This suggested that [11C]20 was superior to [11C](R)1 for imaging. Critically, however, 35% of the [11C]20 signal observed in the mouse brain at 60 min p.i. came from radiometabolites, which is markedly higher than other TSPO radioligands (<10%)79,138,168. This is likely to limit the clinical use of 11C-MBMP. Thus, further evaluation of [11C]20 was not warranted.

3.2.8. Aryloxypyridylamide

N-{2-[2-18F-Fluoroethoxy]-5-methoxybenzyl}-N-[2-(4-methoxyphenoxy)pyridine-3-yl]acetamide [18F]FEMPA [18F]21, Fig. 2), is an aryloxypyridylamide derivative, and is a potential novel second-generation TSPO radioligand. Preclinical results suggested that [18F]21 could be rapidly eliminated from the brain and had a good SNR in nonhuman primates. Varrone et al.190 demonstrated a markedly greater VT for [18F]21 in the medial temporal cortex in AD patients compared with controls when the TSPO binding status was used as a covariate. They also observed a substantially higher VT for [18F]21 in the medial and lateral temporal cortex, posterior cingulate, caudate, putamen, thalamus, and cerebellum in AD patients compared to controls. Their study suggested that [18F]21 could be used as a potential TSPO probe in AD patients if binding status is taken into account.

The second-generation TSPO radioligand properties and PET imaging studies are summarized in Supporting Information Table S2. Most of these PET tracers showed high affinity and high selectivity to TSPO and better SNR compared with [11C]1. Thus, they have the potential to significantly contribute to clinical investigation of the relationship between TSPO and neurological disorders.

3.3. TSPO PET tracers with low binding sensitivity to rs6971 polymorphism

As mentioned above, a major limitation of aforementioned TSPO radioligands is TSPO binding affinity variability in the human brain56,191,192. This binding status variability is influenced by the single nucleotide polymorphism rs6971 in the human TSPO gene, which has been classified as HAB (A/A; ∼70%), MAB (A/T; ∼21%), and LAB (T/T; ∼9%)193. This polymorphism makes it difficult to generate consistent preclinical results with aforementioned TSPO radioligands. New radioligands that are insensitive to the rs6971 polymorphism are needed (Fig. 3).

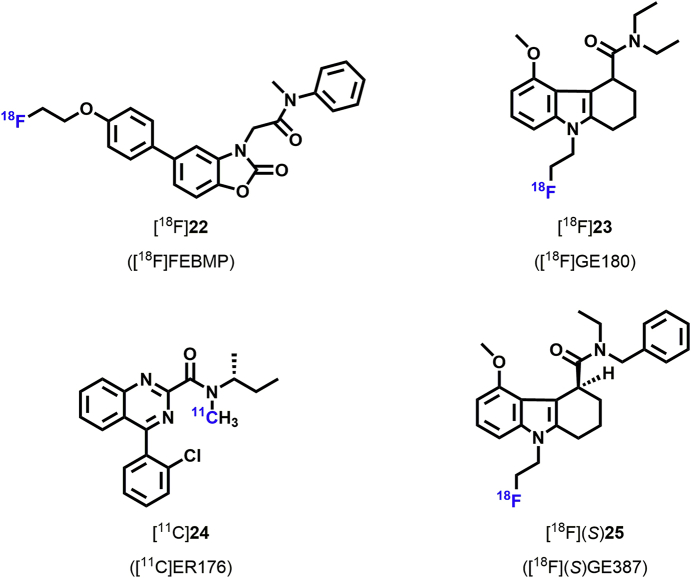

Figure 3.

Chemical structures of new TSPO radioligands with insensitivity to rs6971.

2-[5-(4-Fluoroethoxy-2-oxo-1,3-benzoxazol-3(2H)-yl)-N-methyl-N-phenylacetamide (FEBMP) is a novel TSPO ligand that can be labeled with 18F for use as a radioligand ([18F]22, Fig. 3)194. The binding affinity (Ki) of [18F]22 toward TSPO was 6.6 ± 0.7 nmol/L, and [18F]22 had a suitable lipophilicity (logD = 3.43) in vitro194. A biodistribution study in mice demonstrated a relatively high initial [18F]22 radioactivity (approximately 2.7% ID/g) in the mouse brain at 1 min p.i. High uptake (approximately 3.8% ID/g) was also measured in mouse bone, which is not negligible. However, in the ischemic rat brain, there was very little [18F]22 accumulation in the skull. The investigators speculated that the uptake in mouse bone samples may have resulted from [18F]22 binding to marrow instead of [18F]F− trapped in bones. Metabolic analysis showed that parent [18F]22 remained at 76.4 ± 2.1% at 60 min p.i. in the mouse brain195. Subsequently, in a PET imaging study, Tiwari et al.195 demonstrated that [18F]22 radioactivity in the ischemic rat brain was significantly increased in the ipsilateral striatum compared with the contralateral side. After pre-treatment with unlabeled MBMP or PK11195, the [18F]22 uptake was markedly decreased on the ipsilateral side of the brain, indicating that the [18F]22 signal was specific for TSPO.

Tiwari et al.195 used [18F]22 to demonstrate the association of TSPO genotype with binding variability. In vitro autoradiographic analysis of postmortem human brains suggested that the [18F]22 Ki ratio for LAB to HAB (RKi(L/H)) was 0.9. The ratio of TSPO binding for LAB to HAB (RB(L/H)) was also about 0.90. Thus, the ratio of specific binding for [18F]22 in both the HAB and LAB groups was similar, suggesting that the rs6971 polymorphism didn't affect [18F]22 binding status. Further, their findings suggest that [18F]22 is a promising new tool for visualizing neuroinflammation195. However, in vitro results may differ from in vivo findings. Thus, further investigation of in vivo [18F]22 binding affinity in human subjects with different genotypes is needed.

(S-N,N-Diethyl-9-[2-18F-fluoroethyl]-5-methoxy-2,3,4,9-tetrahydro-1H-carbazole-4-carboxamide) ([18F]GE-180 [18F]23, Fig. 3), is another promising TSPO radioligand used for human PET imaging196. [18F]23 has a very high affinity for TSPO (Ki = 2.4 nmol/L) in rat heart and metabolic analysis showed that 94% of [18F]23 was intact in the brain at 60 min p.i.197, suggesting that [18F]23 is a very promising TSPO radioligand. In recent years, it has been widely used to study neuroinflammation. Wadsworth et al.197 reported that [18F]23 had very good affinity, high brain absorption, and higher specific binding in a neuroinflammation model, and Dickens et al.198 demonstrated that [18F]23 could identify sites of activated microglia in both gray and white matter in a LPS-induced model of acute neuroinflammation. They also suggested that [18F]23 could be used to monitor activated microglia better than [11C](R)1 because of its higher BP and, as a fluorinated radioligand, its longer half-life. Similarly, Boutin et al.199 reported that [18F]23 radioactivity in ischemic rat brains displayed a better SNR than [11C]R-PK11195 due to its very low nonspecific binding. In another study, Liu et al.200 showed that [18F]23 PET imaging could be used to monitor neuroinflammation during AD progression and treatment. Subsequently, López-Picón et al.201 demonstrated that [18F]23 could be used to monitor neuroinflammation and therapeutic modulation of microglial activation in an AD mouse model. Moreover [18F]23 imaging could also be used as a potential tool to study epileptogenesis in a rat model of TLE202.

Feeney et al.203 further demonstrated that the total VT of [18F]23 were no significant correlations in either HAB and MAB. In one study of MS patients, Vomacka et al.204 found that [18F]23 PET imaging could semi-quantitatively evaluate neuroinflammation in patients with relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS). In a subsequent human study, Unterrainer et al.205 demonstrated that [18F]23 PET imaging could detect areas of focal microglia activation in RRMS patient lesions that were not associated with the patient's binding genotype. They found that the SUVR of [18F]23 in the focal lesions of RRMS patients with different TSPO binding genotypes were 1.87 ± 0.43 (HAB), 1.95 ± 0.48 (MAB), and 1.86 ± 0.80 (LAB). However, another recent study showed that [18F]23 had very low brain uptake in human subjects, hindering its translation to human PET imaging206.

Another new TSPO radioligand [11C](R)-N-sec-butyl-4-(2-chlorophenyl)-N-methylquinazoline-2-carboxamide ([11C]ER176 [11C]24, Fig. 3), is a novel quinazoline analog of [11C](R)1 [11C]24 has adequately high binding affinity for all TSPO rs6971 genotypes207. The ratio of radioligand binding in HAB to LAB was only 1.3 to 1 for ER176 in human brain tissue208, whereas the comparable ratio was 55 to 1 for PBR2856. Nevertheless, the clinical relevance of this compound remains to be confirmed.

The latest TSPO radioligand [18F]GE387 ([18F]25, Fig. 3), was recently reported by Qiao et al.209. More importantly, the binding affinities of [18F](S)25 to LAB and HAB were evaluated using an assay based on human embryonic kidney cell lines, and the LAB/HAB ratio was determined to be 1.3, which was similar to that of [11C](R)1. This suggests that [18F]25 TSPO binding affinity is not influenced by TSPO genotype. Moreover, they also showed that the racemic analogue of [18F]25 could enter the brain in wild-type rats. Thus [18F]25 has high potential as a TSPO radioligand due to its long half-life and probably low sensitivity to the human rs6971 polymorphism209. However, further [18F]25 PET imaging studies need to be performed in non-human primates and humans. These new TSPO radioligands properties and PET imaging studies are summarized in Supporting Information Table S3. Although these TSPO radioligands are less sensitive TSPO binding variability compared with aforementioned radioligands, their detection was still inconsistent, limiting further comparisons. Further clinical studies are needed to evaluate these new third-generation TSPO radioligands.

4. Conclusions and perspectives

A candidate PET radioligand must meet a wide array of chemical and biochemical requirements210, including (i) high binding affinity represented by Ki or half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50)—the ligands should generally have high affinity for imaging brain targets in the nanomolar or subnanomolar range; (ii) selectivity for target binding—the ligand should bind only to the biomarker, and possesses weak affinity for off-target sites; (iii) ability to pass the BBB [generally molecular weight MW < 400 Da, appropriate lipophilicity (logD7.4 of 1–3)]; (iv) amenability to be labeled with carbon-11 or fluorine-18. When the ligand is optimized and radiolabeled, the corresponding radioactive PET tracer should (v) have relatively high radiochemical yields (ideally >10%); (vi) show high BP, low nonspecific binding (or low nondisplaceable binding) and rapid clearance for nonspecific binding; (vii) be lack of accumulation of radiometabolites in the brain or radiodefluorination in skull. Specificity for TSPO, receptor binding assays at the cellular level derived from human192,209 would facilitate the discovery of novel ligands with low sensitive or insensitive to genotype, which would be helpful to develop next-generation TSPO PET tracers since traditional PET imaging in rodents or monkeys could not distinguish this rs6971 polymorphism.