Abstract

Tumor microenvironment has been widely utilized for advanced drug delivery in recent years, among which hypoxia-responsive drug delivery systems have become the research hotspot. Although hypoxia-responsive micelles or polymersomes have been successfully developed, a type of hypoxia-degradable nanogel has rarely been reported and the advantages of hypoxia-degradable nanogel over other kinds of degradable nanogels in tumor drug delivery remain unclear. Herein, we reported the synthesis of a novel hypoxia-responsive crosslinker and the fabrication of a hypoxia-degradable zwitterionic poly(phosphorylcholine)-based (HPMPC) nanogel for tumor drug delivery. The obtained HPMPC nanogel showed ultra-long blood circulation and desirable immune compatibility, which leads to high and long-lasting accumulation in tumor tissue. Furthermore, HPMPC nanogel could rapidly degrade into oligomers of low molecule weight owing to the degradation of azo bond in hypoxic environment, which leads to the effective release of the loaded drug. Impressively, HPMPC nanogel showed superior tumor inhibition effect both in vitro and in vivo compared to the reduction-responsive phosphorylcholine-based nanogel, owing to the more complete drug release. Overall, the drug-loaded HPMPC nanogel exhibits a pronounced tumor inhibition effect in a humanized subcutaneous liver cancer model with negligible side effects, which showed great potential as nanocarrier for advanced tumor drug delivery.

KEY WORDS: Hypoxia-degradable, Zwitterionic nanogel, Long blood circulation, Drug release, Drug delivery

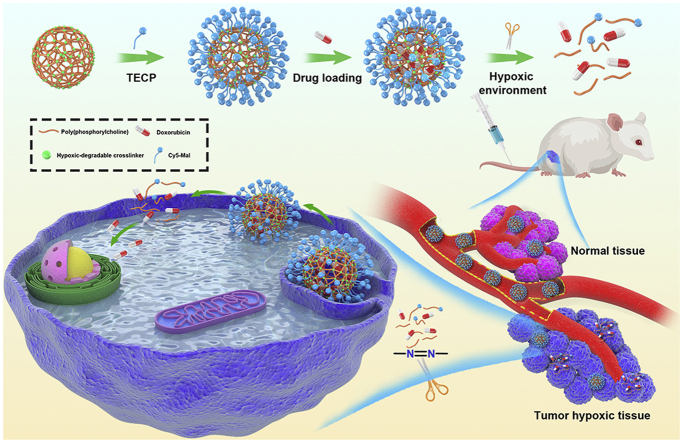

Graphical abstract

HPMPC nanogel shows ultra-long blood circulation without causing the accelerated blood clearance phenomenon, which leads to enhanced accumulation in tumor tissue. HPMPC nanogel holds the drug firmly in blood or normal tissue whereas releases the drug effectively in tumor environment, leading to improved therapeutic effect and negligible side effects.

1. Introduction

Nanogel is a kind of hydrophilic three-dimensional net structure of nanoscale dimension which has been widely used as nanocarrier for tumor drug delivery1, 2, 3. In the fabrication of nanogel, the insertion of degradable crosslinker endows the nanogel with controlled drug release in tumor microenvironment including acidic, redox and specific enzymatic conditions4, 5, 6, 7, 8. For example, nanogel fabricated by crosslinker containing disulfide bonds could achieve the accelerated drug release triggered by the high concentration of glutathione in tumor cytoplasm9, 10, 11. Furthermore, nanogel composed of ketal or acetal bonds-based crosslinker could release the loaded drug rapidly in tumor acidic environment12,13. Despite the great progress of degradable nanogel as drug carriers, there is no report of a type of hypoxia-degradable nanogel and the advantages of hypoxia-degradable nanogel over other kinds of degradable nanogels in tumor drug delivery remain unclear.

Hypoxia featuring low oxygen concentration is a symbol of nearly all the solid tumors, which usually changes the balance of redox states in tumor tissue and leads to the enhanced reductive stress14, 15, 16. Benefiting from the significant difference of bio-reductive enzymes between normal and tumor tissue, various hypoxia-responsive nanocarriers based on 2-nitro imidazole, nitro benzyl derivatives or azobenzene derivatives have been developed17, 18, 19. Owing to the cleavable property of azobenzene bond in hypoxic surroundings, azobenzene derivatives have been extensively developed as building blocks in the construction of hypoxia-responsive nanocarriers20, 21, 22. For example, Kulkarni et al.23 synthesized a hypoxia-responsive polymersome composed of poly(lactic acid)-azobenzene-poly(ethylene glycol), which released the loaded drug rapidly in hypoxic tumor spheroid. Yuan et al.24 prepared biodegradable silica nanoquencher composed of azobenzene bond which achieved specific delivery of the loaded native antibodies in tumor hypoxic environment. Recently, Yang et al.25 fabricated a hypoxia-degradable albumin-based nanosystem for enhanced tumor penetration and photodynamic-chemo combined therapy. Although plenty of nanocarriers based on azobenzene derivatives have been developed, most of them were focused on micelles, polymersomes or nanocomplexes, and developing a hypoxia-degradable nanogel is still in great demand.

Zwitterionic polymers have emerged as a new class of anti-fouling materials which have been utilized to fabricate nanocarriers for tumor drug delivery26, 27, 28. It has been reported that nanocarriers based on zwitterionic polymer exhibit long blood circulation and negligible accelerated blood clearance (ABC) phenomenon29, 30, 31. In the family of zwitterionic polymers, phosphorylcholine, carboxybetaine and sulfobetaine polymers are the most widely applied, among which phosphorylcholine polymers have attracted much attention because of the phosphorylcholine head groups similar to the phospholipids in cell membrane32, 33, 34. Recently, phosphorylcholine polymers were used to fabricate nanogels with crosslinkers composed of disulfide bond which could achieve the controlled drug release in tumor cytoplasm35. However, the super-hydrophilicity feature of phosphorylcholine polymers decreased the interaction with the hydrophobic cell membrane, which leaded to suboptimal anti-tumor effect36. Therefore, it is significant to develop a kind of novel phosphorylcholine polymer nanogel which could be degraded regardless of the cell membrane barrier, thereby enhancing the anti-tumor effect of the drug-loaded nanogel ultimately.

In this work, we synthesized a novel hypoxic-cleavable crosslinker composed of azobenzene bonds and fabricate hypoxic-degradable zwitterionic poly(phosphorylcholine)-based (HPMPC) nanogel for tumor drug delivery, as shown in Fig. 1. The degradability and drug release profiles of the HPMPC nanogel was explored in hypoxic conditions. Furthermore, the blood circulation, biodistribution and anti-tumor effect of drug-loaded HPMPC nanogel were explored in vitro and in vivo. Moreover, the anti-tumor effect between HPMPC nanogel and reduction-degradable poly(phosphorylcholine)-based (RPMPC) nanogel was compared and analyzed. This work may offer new materials and understanding of hypoxic-degradable nanogel in tumor drug delivery.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of the hypoxia-degradable poly(phosphorylcholine)-based (HPMPC) nanogel for tumor drug delivery. HPMPC nanogel shows ultra-long blood circulation without causing the accelerated blood clearance phenomenon, which leads to the enhanced accumulation in tumor tissue. HPMPC nanogel holds the loaded drug firmly in blood or normal tissue whereas releases the drug effectively in tumor hypoxic environment, leading in improved therapeutic effect and negligible side effects.

2. Methods

2.1. Materials

2-Methacryloyloxyethyl phosphorylcholine (MPC, 97%), N,N′-bis(acryloyl)cystamine (BAC, 97%), N-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-N-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride crystalline (EDC, 99%), 4-dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP, 99%), azobenzene-4,4′-dicarboxylic acid (97%), 2-aminoethyl methacrylate hydrochloride (98%), doxorubicin hydrochloride (DOX, 97%), reduced glutathione (GSH, 99%), 2,2-azobisisobutyronitrile (AIBN, 99%), cyanine5 maleimide (Cy5-Mal, 97%), N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF, 99%), tetrahydrofuran (THF, 99%), dichloromethane (DCM, 99%) and acetonitrile (AN, 99%) were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich (Shanghai, China). Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM), rat liver microsomes and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH, 97%) were purchased from CHI Scientific (Jiangyin, China). 4′,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), the immunoglobulin M (IgM) enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) Kit, the immunoglobulinitron G (IgG) ELISA Kit and 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) were obtained from Beyotime (Shanghai, China).

2.2. Cell lines and animals

HepG2 cell line and 293T cell line were provided by Cell Bank of Shanghai, Chinese Academy of Science (CAS, Shanghai, China). BALB/c nude mice (aged 5–6 weeks) were purchased from the Institute of Laboratory Animal Science of Jinan University (Guangzhou, China). All the animal experiments were performed according to the protocol of the Institutional Animal Care and Treatment Committee of Jinan University (Guangzhou, China).

2.3. Synthesis of hypoxic-degradable crosslinker

Azobenzene-4,4′-dicarboxylic acid (11.4 mmol), 2-aminoethyl methacrylate hydrochloride (27.3 mmol), EDC (27.3 mmol) and DMAP (2.85 mmol) were dissolved in 100 mL of DMF with the removal of air by nitrogen (Scheme S1). The system was stirred at 25 °C with the speed of 200 rpm for 48 h (Liyida, Suzhou, China). Then, the system was concentrated to 40 mL by rotary evaporation and separated into 4 centrifuge tubes of 50 mL. Each centrifuge tube was added with 40 mL of pure water and centrifuged with the removal of the liquid supernatant. The washing process was repeated for 3 times. The precipitate was dissolved into THF and dried with sodium sulfate. After the purification of silica gel column chromatography (DCM:THF = 19:1), 1.2 g of brown red powder was obtained. The final yield was calculated as 21.4%. 1H NMR (400 MHZ, DMSO-d6) 1.88 (6H, –C C–CH3), 3.64 (4H, –CH2–NH–), 4.23 (4H, –O–CH2–), 5.63 (2H, =CH), 6.05 (2H, =CH), 7.92 (4H, Ar), 8.11 (4H, Ar), 8.91 (2H, Ar).

2.4. Preparation of the nanogels

MPC (0.542 mmol), hypoxic-degradable crosslinker (0.162 mmol) and AIBN (0.024 mmol) were dispersed into 40 mL of AN and sonicated for 3 min at room temperature. The system was heated to 100 °C at nitrogen atmosphere with the stirring speed of 200 rpm (Liyida, Suzhou, China). The reaction was carried out for 1 h and cooled to room temperature. The system was centrifuged at 12,000 rpm and washed with pure water for 3 times (Beckman Coulter, Inc., Brea, CA, USA). Finally, the HPMPC nanogel with brown red color was acquired and stored for further use. RPMPC nanogel was obtained using BAC as the crosslinker and the detailed recipe and process were the same as HPMPC nanogel.

2.5. Modification of the nanogels with fluorescent dye

To modify the HPMPC nanogel with fluorescent dye, 5 mg of BAC was added in the preparation of the nanogel. 20 mg of HPMPC or RPMPC nanogels were dispersed in 10 mL of PBS solutions (pH = 7.4) and added with 0.2 mg of TCEP. The reaction was performed for 24 h and added with 2 mg of Cy5-Mal (dissolved in 0.5 mL of DMSO). The reaction was carried out for 12 h under a nitrogen atmosphere to obtain the Cy5-labeled nanogels.

2.6. Stability of the nanogels

HPMPC or RPMPC nanogels (0.5 mg/mL) were dispersed in cell culture medium (DMEM) for 7 days. The hydrodynamic sizes of the nanogels were detected at different time points (0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7 days) by dynamic light scattering (DLS, Malvern Nano-ZS90, Malvern, UK).

2.7. Degradability of the nanogels

The turbidity change of the HPMPC nanogel was detected by DLS in 2 mL of PBS with the addition of 100 μL of rat liver microsomes and 100 μmol/L NADPH. Air was bubbled into the solutions to create normoxic conditions. For hypoxic conditions, 5% or 1% of oxygen was bubbled into the systems. As a control, the turbidity change of the RPMPC nanogel was detected in 2 mL of PBS with 0, 5 and 10 mmol/Lof GSH. The nanogels were incubated in PBS 7.4 (0.01 mol/L) at 37 °C, and the turbidity was detected at different intervals. The relative turbidity was calculated as the ratio of turbidity at each time point to the initial turbidity. GPC (HP Agilent series 1100, Santa Clara, CA, USA) was applied to measure the molecular weight of the degraded product of HPMPC or RPMPC nanogels.

2.8. Drug loading and releasing profiles

The amount of 3 mg of DOX was dissolved in 3 mL of deionized water with the pH of 8.0. 10 mg of HPMPC or RPMPC nanogels were added in the above solutions and vibrated at 37 °C for 24 h. Then, the nanogels were separated by centrifugation with the rotational speed of 12,000 rpm and washed 3 times with pure water to remove the unabsorbed DOX. The supernatant was detected by UV–Visible spectrometry (Perkin–Elmer, Lambda750, Waltham, MA, USA) at the excitation wavelength of 488 nm to calculate the concentration of DOX. DOX loading content and DOX encapsulation efficiency were calculated using the following Eqs. (1), (2):

| (1) |

| (2) |

To explore the DOX release behaviors, 2 mL of DOX-loaded HPMPC nanogels (HPMPC@DOX) with 0.1 mg of DOX was encapsulated in a 12,000 Da dialysis bag and incubated in 100 mL of phosphate buffer saline (pH 7.4) with 5 mL of rat liver microsomes and 100 μmol/L NADPH. Air was bubbled into the solutions to create normoxic conditions. For hypoxic conditions, 1% of oxygen was bubbled into the systems. As a control, the drug release profiles of DOX-loaded RPMPC (RPMPC@DOX) nanogel was also performed with 0 or 10 mmol/Lof GSH. At different time points, 2 mL of solution were extracted and added with 2 mL of initial solution. The cumulative amount of DOX released from the nanogel was detected by UV–Visible spectrometry (Perkin–Elmer, Lambda750).

2.9. Cellular uptake behavior

The amount of ∼1 × 106 HepG2 cells per dish were seeded in confocal dishes (Corning, New York, NY, USA) and cultivated in a cell culture medium for 24 h. Afterwards, cells were incubated with Cy5-modified HPMPC@DOX or RPMPC@DOX at equal amounts of DOX for 1, 2, and 4 h in hypoxic environment. Hypoxia environment or normoxic environment were generated in the cells by cultivating in Biospherix C21 hypoxic chamber supplemented with 1% of oxygen or air, respectively. Cells were rinsed and stained with DAPI and observed with a Nikon laser confocal microscope (C2plus, Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). The cellular uptake of HPMPC@DOX or RPMPC@DOX was performed with flow cytometry (Olympus IX71, Tokyo, Japan). HepG2 cells were seeded in 6-well plates at a density of 1 × 105 cells per well and incubated for 24 h. Then, cells were cultivated with HPMPC@DOX or RPMPC@DOX at equal amounts of DOX for 4 h in hypoxic environment. After that, cells were washed several times with PBS and analyzed by flow cytometry (Olympus IX71, Tokyo, Japan).

2.10. Cytocompatibility and cytotoxity assay

HepG2 or 293T cells were seeded in 96-well plates and cultured for 24 h. Then, cells were cultivated with blank HPMPC or RPMPC nanogels (0, 50, 100, 200, 500 and 1000 μg/mL) for 24 h. Then, 20 μL of MTT solution (5 mg/mL) was added into the cells and cultured for 4 h. The supernatant was eliminated and 150 μL of DMSO as added into each well which was measured by an automated microplate spectrophotometer (EpocH2, BioTek Instruments, Santa Clara, CA, USA) at 490 nm. The cytotoxicity of HPMPC@DOX or RPMPC@DOX against HepG2 cells were also explored by the MTT assay for 24 h in normoxic or hypoxic environment (1% of oxygen). The concentration of DOX was determined as 0, 0.1, 0.5, 1.0, and 5.0 μg/mL.

2.11. Blood circulation profiles and immune compatibility

Fifteen nude female BALB/c mice (∼20 g) were separated into three groups with the intravenous administration of free Cy5, Cy5-modified RPMPC and Cy5-modified HPMPC nanogel (500 μg/mL, 100 μL), respectively. Orbital venous blood (50 μL) of each mouse was acquired at different time intervals post injection (0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, 12, 24 and 48 h)37. In Day 5, the blood of each mouse was obtained for the detection of IgM by ELISA. In Day 7, the mice of each group received a second injection as the same dose of the first injection. In the Day 12, the blood of each mouse was obtained for the test of IgG by ELISA. All of the blood samples were treated with three IU of heparin sodium in PBS and centrifuged at 1200 rpm for 10 min (Beckman Coulter, Inc.). The fluorescent intensity of each sample was measured by a fluorescence lifetime spectrometer (QM-40, Horiba Jobin Yvon, Paris, France).

2.12. In vivo fluorescence imaging and biodistribution

Fifteen HepG2 tumor-bearing nude mice were separated into three groups (n = 5) and intravenously injected with 100 μL of free Cy5, Cy5-modified RPMPC and Cy5-modified HPMPC nanogel (500 μg/mL, 100 μL). After the intravenous injection, all the mice were taken the picture by in vivo fluorescence imaging with an optical small animal imaging system (Bruker MI, in vivo Xtreme, Karlsruhe, Germany) at different time intervals (1, 2, 4, 8, 12, 24, 48 and 72 h). All mice were euthanized and the main organs including heart, liver, spleen, lung, kidney and tumor were collected and imaged by the small animal imaging system post-injection for 24 h. In addition, tumor tissues were stained by DAPI and observed by confocal laser scanning microscopy (C2plus, Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

At 24- and 48-h post-injection of free Cy5, Cy5-modified RPMPC and Cy5-modified HPMPC nanogel (500 μg/mL, 100 μL), HepG2 tumor-bearing mice in each group (n = 5) were euthanized with the main organs (heart, liver, spleen, lung and kidney) and tumor extracted. The fluorescence intensities of all the samples were measured to determine the distribution of nanogels in each organs.

2.13. In vivo anti-tumor efficacy

Twenty HepG2 tumor-bearing nude mice (∼20 g) were randomly separated into four groups (n = 5). After the tumor volume of arrives ∼100 mm3, four groups of mice were received with PBS, free DOX, RPMPC@DOX and HPMPC@DOX on Days 0 and 6 for each injection at a DOX dose of 2 mg/kg body weight, respectively. The tumor size and body weight of the mice were tested every other day. On Day 14, all of the mice were euthanized and tumors were dissected and weighed. Histological analysis was performed on major organs by hematoxylin-eosin (HE) staining.

2.14. Blood biochemistry and blood routine test

To explore the biosafety of blank nanogels, 15 female BALB/c mice (∼20 g) were randomly divided into three groups as control, RPMPC and HPMPC. Ten of the mice were intravenously injected with 100 μL of RPMPC or HPMPC nanogels (2 mg/mL), respectively. Post-injection of 24 h, blood samples were collected from each mouse for biochemical and routine blood testing.

2.15. Statistical analysis

All data were showed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Unpaired Student's t-test was conducted for the comparison of two testing groups and a probability (P) less than 0.05 was regarded as statistical significance.

3. Results and discussions

3.1. Synthesis and characterization of hypoxic-degradable crosslinker and nanogel

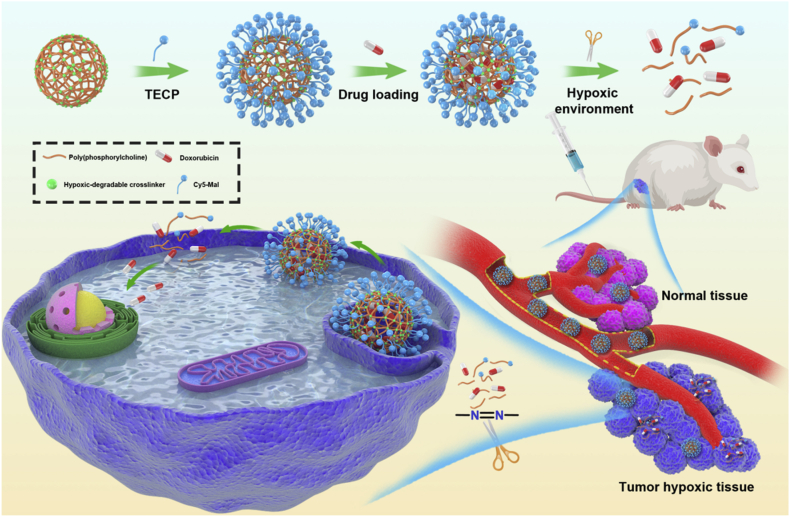

Hypoxia changes the tumor microenvironment through the overexpressed HIF-1α, which leads to the cancer progression and metastasis38,39. It has been reported that the azobenzene group could be cleaved with the elevated levels of reducing enzymes in hypoxic tumor microenvironment40. Furthermore, hypoxic environment exhibits in liver cancer model which was proved by the previous literatures41, 42, 43. In this work, azobenzene-contained crosslinker was synthesized by the amide reaction between azobenzene-4,4′-dicarboxylic acid and 2-aminoethyl methacrylate hydrochloride. The obtained crosslinker showed a brown red color with the yield of 21.4%. The structure of the crosslinker was confirmed by the 1H NMR and 13C NMR, respectively (Fig. 2A and B). In addition, mass spectrum showed that the molecular weight of the crosslinker was regarded as 493.20 g/mol, which agreed well with the theoretical molecular weight (492.20 g/mol, Supporting Information Fig. S1). Furthermore, the FT-IR spectra of the hypoxic-degradable crosslinker revealed that there were clear peaks at 1452 and 1558 cm−1, which belongs to the stretching vibration of N N groups and benzene groups in the crosslinker, respectively (Supporting Information Fig. S2). The bands appearing at 1640 and 1722 cm−1 were attributed to the C C and C O groups, respectively. Lastly, the band at 3302 cm−1 was ascribed to the stretching vibration of N–H in the crosslinker. The above data demonstrated that the azobenzene-contained crosslinker was successfully synthesized.

Figure 2.

Characterization of the hypoxia-degradable crosslinker and the nanogels. (A) 1H NMR and (B) 13C NMR of the hypoxia-degradable crosslinker. (c) Transmission electron microscope (TEM) images of (C) HPMPC nanogel and (D) reduction-degradable poly(phosphorylcholine) nanogel (RPMPC). (E) Hydrodynamic sizes of HPMPC and RPMPC nanogels dispersed in 0.1 mol/L PBS (pH = 7.4).

Zwitterionic phosphorylcholine polymer has been demonstrated as a class of biocompatible and anti-fouling material, which was widely used in biomedical applications44. Herein, HPMPC nanogel was fabricated by the copolymerization of MPC and azobenzene-contained crosslinker with reflux precipitation polymerization. As a control, RPMPC nanogel was synthesized by the copolymerization of MPC and BAC with reduction-cleavable disulfide bonds. From transmission electron microscopy (TEM), it was found that HPMPC nanogel showed uniform spherical shape with the mean diameter of 115 nm while RPMPC nanogel exhibits the mean diameter of 118 nm (Fig. 2C and D). In the meantime, the hydrodynamic size of HPMPC was 158 nm while RPMPC nanogel displayed the similar size of 163 nm (Fig. 2E). The hydrodynamic size of HPMPC nanogel was larger than its TEM diameter owing to the swollen of the nanogel in aqueous solution. Moreover, the zeta potentials of both HPMPC and RPMPC nanogels were nearly neutral due to the equal positive and negative charge (Supporting Information Fig. S3). In addition, the hydrodynamic sizes of HPMPC and RPMPC remain nearly unchanged after incubation in cell culture medium for seven days, which indicated the favorable stability of the nanogels (Supporting Information Fig. S4).

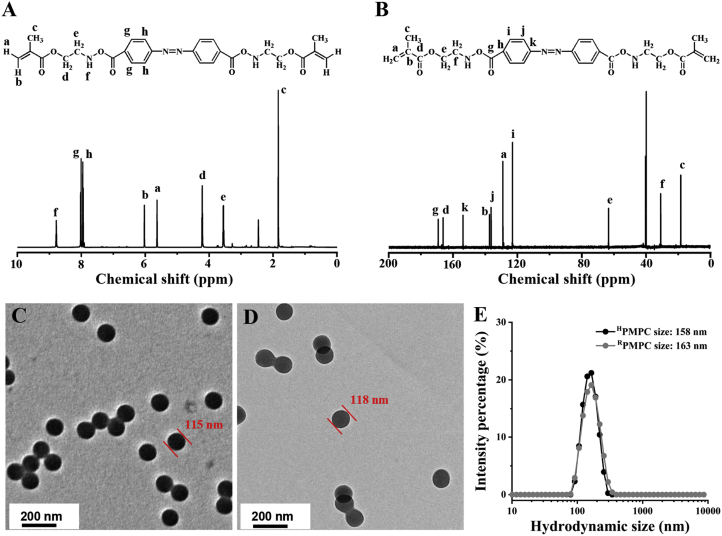

3.2. Degradation and drug releasing profiles of the nanogels

To explore the hypoxia-degradability of the HPMPC nanogel, the relative turbidity of the nanogel solutions were measured by DLS with air flow, 5% and 1% of oxygen. It was showed that the relative turbidity of HPMPC nanogel remains nearly 100%, which indicated the high stability of HPMPC nanogel in normoxic conditions. In 5% of oxygen, the relative turbidity of HPMPC nanogel drops to 87.0% after 2 h, which demonstrated the partial degradation of the nanogel (Fig. 3A). Furthermore, the relative turbidity of HPMPC nanogel reduced to 5.8% after 2 h in 1% of oxygen, indicating the sufficient degradation of HPMPC nanogel in hypoxic condition. Next, the degradation behaviors of RPMPC nanogel in different concentrations of GSH were explored. The results showed that RPMPC nanogel could be completely degraded after 50 min in 10 mmol/LGSH, which exhibited a faster degradation speed compared with HPMPC nanogel in hypoxic condition (Fig. 3B). Moreover, the degradation products of HPMPC and RPMPC nanogels were collected and analyzed by GPC. It was found that the molecule weight of HPMPC nanogel after degradation was calculated as 2100 g/mol, which was close to that of RPMPC nanogel after degradation (Fig. 3C). The above results demonstrated that HPMPC nanogel could be efficiently degraded into oligomers with low molecule weight in hypoxic condition.

Figure 3.

The degradation and drug release profiles of HPMPC and RPMPC nanogels. (A) The relative turbidity change of HPMPC nanogel with air, 5% of oxygen and 1% of oxygen gas flow. (B) The relative turbidity change of RPMPC nanogel with 0, 5 and 10 m mmol/L GSH. (C) Gel permeation chromatography (GPC) trace of the products of HPMPC and RPMPC nanogels after degradation. (D) Doxorubicin (DOX) release profiles of HPMPC@DOX with air and 1% of oxygen gas flow or RPMPC@DOX with 0 and 10 m mmol/L GSH at 37 °C in phosphate buffer.

DOX was selected as the model drug to test the drug loading and releasing properties of the HPMPC nanogel. It revealed that the DOX loading and encapsulation efficiency of HPMPC nanogel were calculated as 7.7% and 25.6%, respectively, which were close to those of RPMPC nanogel (7.4% and 24.7%, respectively). Furthermore, the drug-releasing profiles of HPMPC@DOX were tested in normoxic and hypoxic conditions, respectively. It was found that HPMPC@DOX holds the loaded DOX firmly with only 8.9% of leakage in normoxic condition after 48 h (Fig. 3D). However, HPMPC@DOX showed a rapid DOX release in hypoxic condition and 86.3% of the loaded DOX were released, which was attributed to the degradation of the azobenzene bond in hypoxic condition. RPMPC@DOX exhibited an even faster DOX release profile in reduction environment (10 mmol/LGSH) with 94.2% of loaded DOX released after 48 h, which was ascribed to the faster degradation speed of RPMPC in 10 mmol/LGSH compared to HPMPC in 1% of oxygen.

3.3. Cellular uptake and cytotoxicity of the nanogels

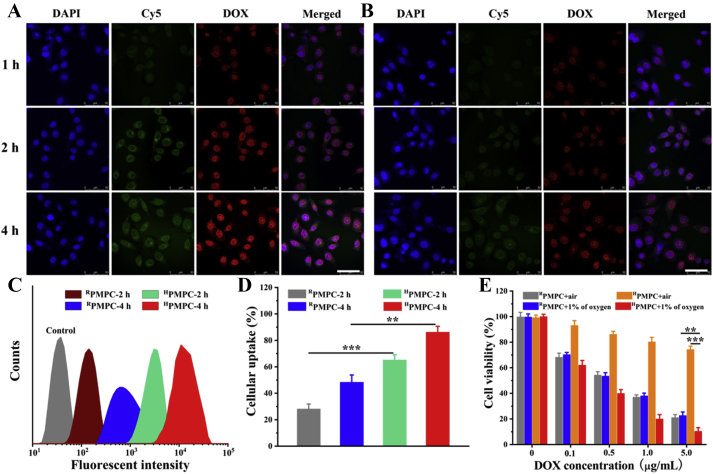

Hydrophilicity is a basic requirement for nanocarriers in tumor drug delivery, which could increase the stability of nanocarriers in vivo and reduce the protein corona on the surfaces45,46. However, tumor cell membranes are usually hydrophobic, which decrease the cellular uptake of the hydrophilic nanocarriers into the tumor cells47,48. Compared with other stimuli signals in tumor cells such as GSH, hypoxic conditions exist both in intracellular and extracellular environments in tumor tissue, which may be beneficial for the sufficient drug releasing of HPMPC@DOX. The HepG2 cellular uptake of the HPMPC@DOX was firstly evaluated by the CLSM observation. Fig. 4A revealed that red fluorescent signals of DOX, which were mainly focused on the cell nucleus, were increasingly enhanced with the extension of incubation time. On the contrary, negligible fluorescent signals were observed incubation of HPMPC@DOX in normoxic environment, owing to the nondegradable property of HPMPC in the air (Supporting Information Fig. S5). Given that HPMPC@DOX with the hydrodynamic size larger than the pore diameters of cell nucleus, it could be concluded that HPMPC@DOX was effectively degraded in hypoxic condition in vitro. Meanwhile, Fig. 4B showed that RPMPC@DOX exhibits significant weaker fluorescent signals compared to those of HPMPC@DOX, which was attributed to the suboptimal cellular uptake and insufficient drug release of RPMPC@DOX, since RPMPC could only be degraded after the cellular uptake. Flow cytometry was further employed to quantitatively explore the cellular uptake of HPMPC@DOX and RPMPC@DOX (Fig. 4C). Fig. 4D showed that the DOX internalization of HPMPC@DOX was significantly higher than that of RPMPC@DOX, which agreed well with the CLSM results. Therefore, it could be concluded that hypoxia-degradable nanogel showed superior drug releasing ability regardless of the barrier of cell membranes compared to the reduction-degradable analogue.

Figure 4.

Confocal laser scanning microscopy observation of DOX loaded HPMPC (A) and RPMPC (B) in hypoxic environment. Flow cytometry analysis (C) and quantitative analysis (D) of the cellular uptake of HPMPC and RPMPC with different treatment. (E) Cytotoxicity of DOX loaded HPMPC and RPMPC to HepG2 cells with air flow or 1% of oxygen. Scale bar = 50 μm ∗∗P < 0.01 and ∗∗∗P < 0.001.

The cytotoxicity of blank HPMPC and RPMPC nanogels were explored from the concentration of 0–1000 μg/mL. It was found that both the HPMPC and RPMPC nanogels showed negligible toxicity to HepG2 cells and 293T cells at the high concentration of 1000 μg/mL, which indicated the favorable biocompatibility of the nanogels (Supporting Information Figs. S6 and S7). Furthermore, the inhibition effects of HPMPC@DOX and RPMPC@DOX to HepG2 tumor cells were explored at hypoxic or normoxic conditions. Fig. 4E revealed that HPMPC@DOX exhibits significantly stronger inhibition effect to tumor cells at hypoxic condition compared to normoxic condition, owing to the rapid drug release at hypoxic condition. More interestingly, HPMPC@DOX showed superior tumor-killing effect than RPMPC@DOX at hypoxic condition which was attributed to the complete drug releasing ability of HPMPC@DOX regardless of the cellular uptake. Therefore, the above results demonstrated that hypoxic-degradable HPMPC nanogel displayed better anti-tumor effect in vitro compared to the reduction-degradable analogue.

3.4. Pharmacokinetics, immune response and biodistribution of the nanogels

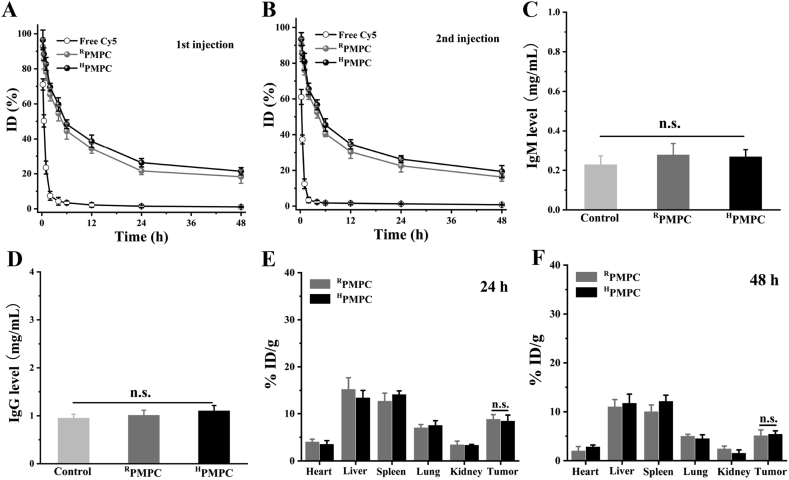

The blood circulation behaviors of the nanogels were explored by detecting the fluorescent signal intensity in blood after intravenous injection of free Cy5, Cy5-modified RPMPC and Cy5-modified HPMPC. Fig. 5A showed that both RPMPC and HPMPC nanogels exhibit ultra-long blood circulation compared to free Cy5, which was consistent well with the previous reports49,50. Furthermore, the blood retention of RPMPC (t1/2 = 45.7 h) and HPMPC (t1/2 = 44.2 h) were very close after intravenous injection due to the similar hydrodynamic sizes and surface properties of the nanogels. In addition, the pharmacokinetics profiles of RPMPC and HPMPC nanogels were nearly unchanged after the second injection, demonstrating that the repeated injection of RPMPC and HPMPC nanogels would not induce the ABC phenomenon (Fig. 5B). The immune response of mice was evaluated by detecting the IgM and IgG level in blood after intravenous injection of RPMPC or HPMPC nanogels. Fig. 5C displayed that the administration of RPMPC or HPMPC nanogels did not induce the significant rise of IgM level in blood. Similarly, Fig. 5D showed that both RPMPC and HPMPC nanogels did not induce the rise of IgG level, which indicated the desirable immune compatibility of the nanogels. The biodistribution of the nanogels were explored by detecting the fluorescent signal intensity in the major organs (heart, liver, spleen, lung and kidney) and tumor. Fig. 5E revealed that both RPMPC and HPMPC nanogels could effectively accumulate in tumor tissue post-injection for 24 h due to the well-known enhanced permeation and retention effect. Furthermore, both RPMPC and HPMPC nanogels still remained high tumor accumulation post-injection for 48 h which was ascribed to the long blood circulation of the nanogels (Fig. 5F).

Figure 5.

In vivo pharmacokinetics of free Cy5, RPMPC and HPMPC nanogels after the 1st intravenous injection (A) and (B) the 2nd intravenous injection in BALB/c mice. (C) The detection of immunoglobulin M (IgM) levels in vivo after the 1st injection. (D) The detection of immunoglobulin G (IgG) levels in vivo after the 2nd injection. The distribution of RPMPC and HPMPC nanogels in the main organs and tumors at (E) 24 h and (F) 48 h post-injection. n.s.: no significant difference.

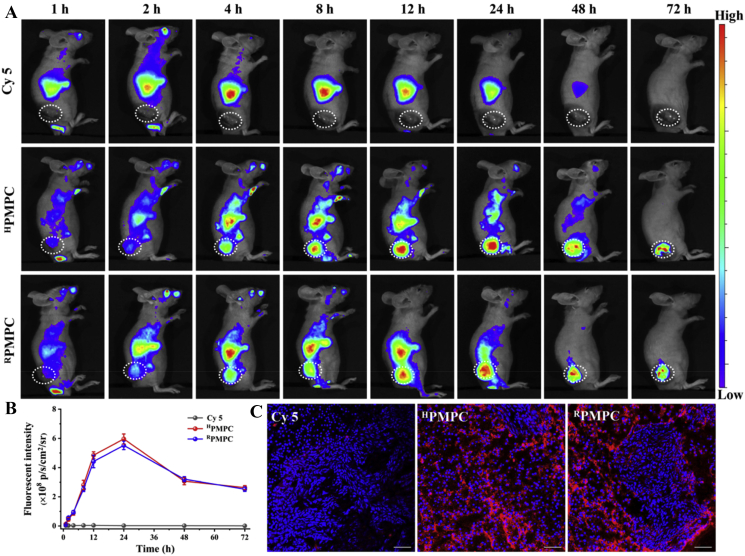

3.5. Near-infrared fluorescence imaging of the nanogels

To intuitively observe the tumor accumulation of the nanogels, near-infrared fluorescence imaging (NIFR) was carried out at varied time points post-injection of free Cy5, RPMPC and HPMPC. Fig. 6A showed that negligible fluorescent signals appeared at tumor tissue in the group of free Cy5 post-injection for 72 h, which demonstrated that free Cy5 could not effectively accumulate at tumor tissue. Meanwhile, bright red fluorescent signals were observed at tumor tissue post-injection of RPMPC and HPMPC nanogels, demonstrating the high and long-lasting accumulation of the nanogels at tumor tissue. Furthermore, the tumor accumulation of RPMPC and HPMPC nanogels did not present significant difference, which agreed well with the biodistribution experiments (Fig. 6B). Furthermore, mice were euthanized after injection for 24 h with major organs (heart, liver, spleen, lung, kidneys, and tumor) imaged by fluorescence imaging of live animals. Most of the fluorescent signals accumulated in tumors in RPMPC or HPMPC groups, demonstrating high tumor accumulation of the nanogels (Fig. S8). Moreover, CLSM observation of tumor slices post-injection for 24 h showed that strong red fluorescent signals were observed in the groups of RPMPC or HPMPC, whereas negligible red fluorescent signal was found in the group of free Cy5, which indicated the specific tumor accumulation ability of the nanogels (Fig. 6C).

Figure 6.

Near-infrared fluorescence imaging observation of mice with different treatment. (A) In vivo fluorescence imaging of mice after intravenous injected with free Cy5, HPMPC nanogel and RPMPC nanogel (tumor pointed out with white circle). (B) Fluorescence intensities of tumors versus post-injection time. (C) CLSM observation of tumor slices post-injection time of 24 h. The cell nuclei (blue) are stained by DAPI. Scale bar = 50 μm.

3.6. Anti-tumor effect and biosafety of the nanogels

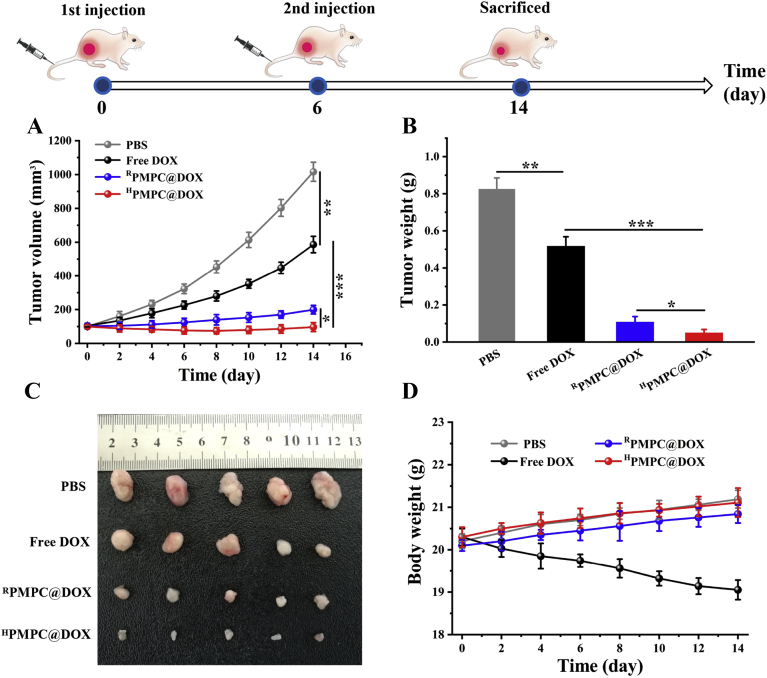

To further evaluate the anti-tumor effect of DOX-loaded nanogels, HepG2 tumor-bearing mice were treated with PBS, free DOX, RPMPC@DOX, and HPMPC@DOX, respectively. Fig. 7A showed that the PBS group had rapid tumor growth, whereas the free DOX group exhibited a moderate tumor inhibition effect with the tumor volume of 586.1 mm3 after 14 days. Furthermore, RPMPC@DOX displayed a significant tumor inhibition effect, which was ascribed to the high tumor accumulation and reduction degradability of the samples. Moreover, the strongest tumor growth inhibition effect was observed in the group of HPMPC@DOX. The superior anti-tumor effect of HPMPC@DOX than RPMPC@DOX was attributed to the more sufficient DOX release of HPMPC@DOX in tumor tissue than RPMPC@DOX. As mentioned above, RPMPC@DOX could only release the loaded DOX after the cellular uptake by tumor cells with limited efficiency, which impaired the overall anti-tumor effect of RPMPC@DOX. As to HPMPC@DOX, DOX could be effectively released from the nanogels regardless of the cell membrane barriers, leading to better anti-tumor effect. After the treatment of 14 days, all the mice were sacrificed; tumors were dissected, weighed, and imaged (Fig. 7C). The tumor weights for the PBS, free DOX, RPMPC@DOX, and HPMPC@DOX were 0.83 ± 0.055, 0.52 ± 0.048, 0.11 ± 0.028 and 0.052 ± 0.016 g, respectively (Fig. 7B). To explore the biosafety of the treated groups in vivo, the treated mice were weighed every other day. As shown in Fig. 7D, only the free DOX group induced significant body weight loss, owing to the severe cardiotoxicity of free DOX to normal cells, which indicated that the encapsulation of DOX into zwitterionic phosphorylcholine nanogels reduces the toxicity of free DOX.

Figure 7.

Anti-tumor effect of drug-loaded nanogels. (A) Tumor growth curves, (B) tumor weights and (C) tumor photograph of the mice after injection with PBS, free DOX, RPMPC@DOX and HPMPC@DOX. (D) Weight variation of HepG2 tumor-bearing mice after injection with PBS, free DOX, RPMPC@DOX and HPMPC@DOX. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01 and ∗∗∗P < 0.001.

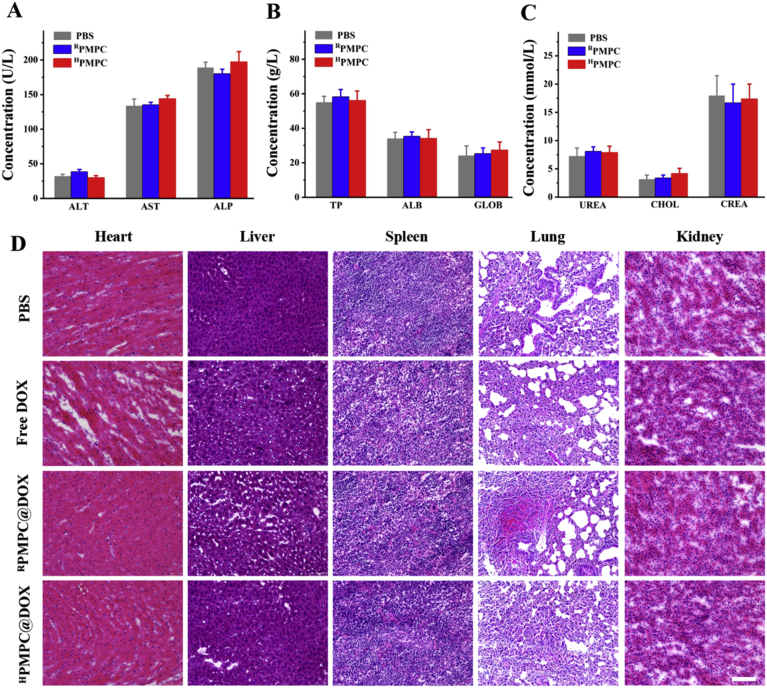

H&E staining of major organs (heart, liver, spleen, lung and kidney) was further performed to evaluate the possible side effects of the nanogels. Fig. 8D uncovered that no significant tissue damage was observed in the RPMPC@DOX and HPMPC@DOX groups. Slight myocardial fiber rupture was observed in free DOX group, maybe owing to the cardiotoxicity of DOX. Moreover, the biosafety of the nanogels was evaluated by the blood biochemistry and routine blood tests. Fig. 8A–C revealed that no significant difference was found among the mice in the PBS, RPMPC and HPMPC group. Therefore, the above results demonstrated that HPMPC nanogel showed favorable biocompatibility and biosafety in vivo.

Figure 8.

Biosafety evaluation of the nanogels. The concentration of (A) aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and alkaline phosphatase (ALP); (B) total protein (TP), albumin (ALB), and globulin (GLOB); (C) urea, cholesterol (CHOL), and creatinine (CREA) after treated for 24 h. (D) HE-stained sections of the main organs (heart, liver, spleen, lungs, and kidneys). Scale bars = 100 μm.

4. Conclusions

In summary, a type of hypoxia-degradable poly(phosphorylcholine)-based nanogel was rationally designed for tumor hypoxic-triggered drug release. The obtained HPMPC nanogel displayed desirable long blood circulation and negligible immune response, which led to the enhanced tumor accumulation. Impressively, the HPMPC nanogel could be effectively degraded and release the loaded drug in tumor tissue regardless of the cell membrane barrier which was encountered by the reduction-degradable analogue. Therefore, drug-loaded HPMPC nanogel presented superior tumor inhibition effect both in vitro and in vivo compared to the drug-loaded RPMPC nanogel. Lastly, HPMPC nanogel showed favorable biocompatibility and biosafety in vivo. Therefore, this work provided a novel hypoxia-cleavable crosslinker which could be employed to synthesize hypoxia-degradable nanogels and offered new understanding of hypoxia-degradable nanogels in tumor drug delivery.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2017YFA0205200), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81903165 and 81901857) and the Chinese Postdoctoral Foundation (Grant No. 2019M663361, China).

Author contributions

Ligong Lu, Shaojun Peng and Shun Shen designed the research. Shaojun Peng and Boshu Ouyang carried out the experiments and performed data analysis. Yongjie Xin and Meixiao Zhan participated part of the experiments. Wei Zhao provided experimental drugs and quality control. Shaojun Peng wrote the manuscript. Shun Shen revised the manuscript. All of the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chinese Pharmaceutical Association and Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences.

Supporting data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsb.2020.08.012.

Contributor Information

Shun Shen, Email: nanocarries@gmail.com.

Meixiao Zhan, Email: zhanmeixiao1987@126.com.

Ligong Lu, Email: luligong1969@126.com.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Oh J.K., Drumright R., Siegwart D.J., Matyjaszewski K. The development of microgels/nanogels for drug delivery applications. Prog Polym Sci. 2008;33:448–477. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chacko R.T., Ventura J., Zhuang J., Thayumanavan S. Polymer nanogels: a versatile nanoscopic drug delivery platform. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2012;64:836–851. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eckmann D.M., Composto R.J., Tsourkas A., Muzykantov V.R. Nanogel carrier design for targeted drug delivery. J Mater Chem B. 2014;2:8085–8097. doi: 10.1039/C4TB01141D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang Y., Zheng J., Tian Y., Yang W. Acid degradable poly(vinylcaprolactam)-based nanogels with ketal linkages for drug delivery. J Mater Chem B. 2015;3:5824–5832. doi: 10.1039/c5tb00703h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang W., Tung C.H. Redox-responsive cisplatin nanogels for anticancer drug delivery. Chem Commun. 2018;54:8367–8370. doi: 10.1039/c8cc01795f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang Y., Luo Y., Zhao Q., Wang Z., Xu Z., Jia X. An enzyme-responsive nanogel carrier based on PAMAM dendrimers for drug delivery. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2016;8:19899–19906. doi: 10.1021/acsami.6b05567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu R., An Y., Jia W., Wang Y., Wu Y., Zhen Y., et al. Macrophage-mimic shape changeable nanomedicine retained in tumor for multimodal therapy of breast cancer. J Control Release. 2020;321:589–601. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2020.02.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu R., Hu C., Yang Y., Zhang J., Gao H. Theranostic nanoparticles with tumor-specific enzyme-triggered size reduction and drug release to perform photothermal therapy for breast cancer treatment. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2019;9:410–420. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2018.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pan Y.J., Chen Y.Y., Wang D.R., Wei C., Guo J., Lu D.R., et al. Redox/pH dual stimuli-responsive biodegradable nanohydrogels with varying responses to dithiothreitol and glutathione for controlled drug release. Biomaterials. 2012;33:6570–6579. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.05.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maciel D., Figueira P., Xiao S., Hu D., Shi X., Rodrigues J., et al. Redox-responsive alginate nanogels with enhanced anticancer cytotoxicity. Biomacromolecules. 2012;14:3140–3146. doi: 10.1021/bm400768m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen W., Zou Y., Zhong Z., Haag R. Cyclo (RGD)-decorated reduction-responsive nanogels mediate targeted chemotherapy of integrin overexpressing human glioblastoma in vivo. Small. 2017;13:1601997. doi: 10.1002/smll.201601997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu B., Thayumanavan S. Substituent effects on the pH sensitivity of acetals and ketals and their correlation with encapsulation stability in polymeric nanogels. J Am Chem Soc. 2017;139:2306–2317. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b11181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang X., Malhotra S., Molina M., Haag R. Micro-and nanogels with labile crosslinks-from synthesis to biomedical applications. Chem Soc Rev. 2015;44:1948–1973. doi: 10.1039/c4cs00341a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bhandari V., Hoey C., Liu L.Y., Lalonde E., Ray J., Livingstone J., et al. Molecular landmarks of tumor hypoxia across cancer types. Nat Genet. 2019;51:308–318. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0318-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Song R., Zhang M., Liu Y., Cui Z., Zhang H., Tang Z., et al. A multifunctional nanotheranostic for the intelligent MRI diagnosis and synergistic treatment of hypoxic tumor. Biomaterials. 2018;175:123–133. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2018.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Masoud G.N., Li W. HIF-1α pathway: role, regulation and intervention for cancer therapy. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2015;5:378–389. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2015.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thambi T., Deepagan V.G., Yoon H.Y., Han H.S., Kim S.H., Son S., et al. Hypoxia-responsive polymeric nanoparticles for tumor-targeted drug delivery. Biomaterials. 2014;35:1735–1743. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thambi T., Park J.H., Lee D.S. Hypoxia-responsive nanocarriers for cancer imaging and therapy: recent approaches and future perspectives. Chem Commun. 2016;52:8492–8500. doi: 10.1039/c6cc02972h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Son S., Rao N.V., Ko H., Shin S., Jeon J., Han H.S., et al. Carboxymethyl dextran-based hypoxia-responsive nanoparticles for doxorubicin delivery. Int J Biol Macromol. 2018;110:399–405. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.11.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kulkarni P., Haldar M.K., Katti P., Dawes C., You S., Choi Y., et al. Hypoxia responsive, tumor penetrating lipid nanoparticles for delivery of chemotherapeutics to pancreatic cancer cell spheroids. Bioconjugate Chem. 2016;27:1830–1838. doi: 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.6b00241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun C., Yue L., Cheng Q., Wang Z., Wang R. Macrocycle-based polymer nanocapsules for hypoxia-responsive payload delivery. ACS Mater Lett. 2020;2:266–271. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang C., Zheng J., Ma D., Liu N., Zhu C., Li J., et al. Hypoxia-triggered gene therapy: a new drug delivery system to utilize photodynamic-induced hypoxia for synergistic cancer therapy. J Mater Chem B. 2018;6:6424–6430. doi: 10.1039/c8tb01805g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kulkarni P., Haldar M.K., You S., Choi Y., Mallik S. Hypoxia-responsive polymersomes for drug delivery to hypoxic pancreatic cancer cells. Biomacromolecules. 2016;17:2507–2513. doi: 10.1021/acs.biomac.6b00350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yuan P., Zhang H., Qian L., Mao X., Du S., Yu C., et al. Intracellular delivery of functional native antibodies under hypoxic conditions by using a biodegradable silica nanoquencher. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2017;56:12481–12485. doi: 10.1002/anie.201705578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang G., Phua S.Z.F., Lim W.Q., Zhang R., Feng L., Liu G., et al. A hypoxia-responsive albumin-based nanosystem for deep tumor penetration and excellent therapeutic efficacy. Adv Mater. 2019;31:1901513–1901521. doi: 10.1002/adma.201901513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peng S., Ouyang B., Men Y., Du Y., Cao Y., Xie R., et al. Biodegradable zwitterionic polymer membrane coating endowing nanoparticles with ultra-long circulation and enhanced tumor photothermal therapy. Biomaterials. 2020;231:119680–119692. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2019.119680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu D., Qin M., Xu D., Wang L., Liu C., Ren J. A bioinspired platform for effective delivery of protein therapeutics to the central nervous system. Adv Mater. 2019;31:1807557–1807563. doi: 10.1002/adma.201807557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peng S., Wang H., Zhao W., Xin Y., Liu Y., Yu X. Zwitterionic polysulfamide drug nanogels with microwave augmented tumor accumulation and on-demand drug release for enhanced cancer therapy. Adv Funct Mater. 2020;30:2001832. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang W., Liu S., Bai T., Keefe A.J., Zhang L., Ella-Menye J.R., et al. Poly(carboxybetaine) nanomaterials enable long circulation and prevent polymer-specific antibody production. Nano Today. 2014;9:10–16. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Men Y., Peng S., Yang P., Jiang Q., Zhang Y., Shen B., et al. Biodegradable zwitterionic nanogels with long circulation for antitumor drug delivery. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2018;10:23509–23521. doi: 10.1021/acsami.8b03943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liang S., Liu Y., Jin X., Liu G., Wen J., Zhang L., et al. Phosphorylcholine polymer nanocapsules prolong the circulation time and reduce the immunogenicity of therapeutic proteins. Nano Res. 2016;9:1022–1031. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jackson M.A., Werfel T.A., Curvino E.J., Yu F., Kavanaugh T.E., Sarett S.M., et al. Zwitterionic nanocarrier surface chemistry improves siRNA tumor delivery and silencing activity relative to polyethylene glycol. ACS Nano. 2017;11:5680–5696. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.7b01110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Han L., Liu C., Qi H., Zhou J., Wen J., Wu D., et al. Systemic delivery of monoclonal antibodies to the central nervous system for brain tumor therapy. Adv Mater. 2019;31:1805697–1805705. doi: 10.1002/adma.201805697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang L., Shi C., Wang X., Guo D., Duncan T.M., Luo J. Zwitterionic Janus dendrimer with distinct functional disparity for enhanced protein delivery. Biomaterials. 2019;215:119233. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2019.119233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xie R., Tian Y., Peng S., Zhang L., Men Y., Yang W. Poly(2-methacryloyloxyethyl phosphorylcholine)-based biodegradable nanogels for controlled drug release. Polym Chem. 2018;9:4556–4565. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peng S., Men Y., Xie R., Tian Y., Yang W. Biodegradable phosphorylcholine-based zwitterionic polymer nanogels with smart charge-conversion ability for efficient inhibition of tumor cells. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2019;539:19–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2018.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jiang Q., Luo Z., Men Y., Yang P., Peng H., Guo R., et al. Red blood cell membrane-camouflaged melanin nanoparticles for enhanced photothermal therapy. Biomaterials. 2017;143:29–45. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brown J.M., Wilson W.R. Exploiting tumour hypoxia in cancer treatment. Nat Rev Canc. 2004;4:437–447. doi: 10.1038/nrc1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu Y., Zhang L., Nazare M., Yao Q., Hu H.Y. A novel nitroreductase-enhanced MRI contrast agent and its potential application in bacterial imaging. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2018;8:401–408. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2017.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kiyose K., Hanaoka K., Oushiki D., Nakamura T., Kajimura M., Suematsu M., et al. Hypoxia-sensitive fluorescent probes for in vivo real-time fluorescence imaging of acute ischemia. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:15846–15848. doi: 10.1021/ja105937q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu X.Z., Xie G.R., Chen D. Hypoxia and hepatocellular carcinoma: the therapeutic target for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:1178–1182. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.04997.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Duran R., Mirpour S., Pekurovsky V., Ganapathy-Kanniappan S., Brayton C.F., Cornish T.C., et al. Preclinical benefit of hypoxia-activated intra-arterial therapy with evofosfamide in liver cancer. Clin Canc Res. 2017;23:536–548. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-0725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bowyer C., Lewis A.L., Lloyd A.W., Phillips G.J., Macfarlane W.M. Hypoxia as a target for drug combination therapy of liver cancer. Anti-cancer Drug. 2017;28:771–780. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0000000000000516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Matsuno R., Ishihara K. Integrated functional nanocolloids covered with artificial cell membranes for biomedical applications. Nano Today. 2011;6:61–74. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Peng S., Liu J., Qin Y., Wang H., Cao B., Lu L., et al. Metal-organic framework encapsulating hemoglobin as a high-stable and long-circulating oxygen carriers to treat hemorrhagic shock. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2019;11:35604–35612. doi: 10.1021/acsami.9b15037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhao L., Shen G., Ma G., Yan X. Engineering and delivery of nanocolloids of hydrophobic drugs. Adv Colloid Interface Sci. 2017;249:308–320. doi: 10.1016/j.cis.2017.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xu C.F., Zhang H.B., Sun C.Y., Liu Y., Shen S., Yang X.Z., et al. Tumor acidity-sensitive linkage-bridged block copolymer for therapeutic siRNA delivery. Biomaterials. 2016;88:48–59. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang Z., Sun N., Cheng R., Zhao C., Liu Z., Li X., et al. pH multistage responsive micellar system with charge-switch and PEG layer detachment for co-delivery of paclitaxel and curcumin to synergistically eliminate breast cancer stem cells. Biomaterials. 2017;147:53–67. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhao J., Qin Z., Wu J., Li L., Jin Q., Ji J. Zwitterionic stealth peptide-protected gold nanoparticles enable long circulation without the accelerated blood clearance phenomenon. Biomater Sci. 2018;6:200–206. doi: 10.1039/c7bm00747g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ou H., Cheng T., Zhang Y., Liu J., Ding Y., Zhen J., et al. Surface-adaptive zwitterionic nanoparticles for prolonged blood circulation time and enhanced cellular uptake in tumor cells. Acta Biomater. 2018;65:339–348. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2017.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.