Abstract

Cnidarians are emerging model organisms for cell and molecular biology research. However, successful cell culture development has been challenging due to incomplete tissue dissociation and contamination. In this report, we developed and tested several different methodologies to culture primary cells from all tissues of two species of Cnidaria: Nematostella vectensis and Pocillopora damicornis. In over 170 replicated cell cultures, we demonstrate that physical dissociation was the most successful method for viable and diverse N. vectensis cells while antibiotic-assisted dissociation was most successful for viable and diverse P. damicornis cells. We also demonstrate that a rigorous antibiotic pretreatment results in less initial contamination in cell cultures. Primary cultures of both species averaged 12–13 days of viability, showed proliferation, and maintained high cell diversity including cnidocytes, nematosomes, putative gastrodermal, and epidermal cells. Overall, this work will contribute a needed tool for furthering functional cell biology experiments in Cnidaria.

Subject terms: Biological techniques, Cell culture

Introduction

Cell culture is a valuable tool used for growing and maintaining cells in a controlled ex vivo environment1. Primary cell cultures are a type of short-term cell culture where the cells being maintained are the same types that came directly from the tissue, resulting in a diverse mix of cell types2. Primary cell cultures of multiple cell types are particularly important for studying emerging model organisms because they allow for observation and manipulation of a diversity of undescribed cell types that are still functioning as they would in vivo3–5.

The phylum of Cnidaria is a diverse group of predominantly marine organisms with 2 tissue layers (ectoderm and endoderm) united by the presence of cnidocyte stinging cells5. They are the sister group to bilaterians, and therefore represent an important branch for our understanding of bilaterian evolution6, 7. Cnidarians, and in particular scleractinian corals, are also critically important for ocean biodiversity and health43,44. However, much about the cell biology of anthozoans is still unknown10,11, in part due to there being no reliable cell culture method established12–14.

Historically, cnidarian cell cultures have been challenging to maintain due to contamination and a lack of tailored media7,14,15. Cell culture methods have been developed for many different cnidarian species; however, no long-lived cultures of individual cells have been established7,14. Cnidarian tissues are constantly exposed to their natural environment due to relatively simple tissue organization, and this along with their mucus layer, has been hypothesized to lead to a higher association with a diverse microbiome that can overgrow a cell culture16–18. Given these challenges there are many areas where cell culture can be improved to achieve longevity. This includes the dissociation method, media choice, and the development of antimicrobial pre-treatments.

Here, we report the first primary cell cultures using all tissues of the model sea anemone N. vectensis, and the development of a novel method of antibiotic-facilitated dissociation for the adult coral, P. damicornis. This is also the first time that individual cells from all tissues of coral or sea anemones were shown to survive in cell culture for over 12 days. Previous cell culture studies that showed over 10 days of viability were from specific tissues, produced intact multicellular structures, or had other exceptions that make their methodology not ideal for broader use (Table 1)5,8,9,18–32. The goal of this experiment was to build on these previous cnidarian cell culture studies and produce reliable cell cultures that can be used as a versatile tool for live cell assays. We developed an extensive antimicrobial pre-treatment protocol to reduce microbial contamination. We tested several different medias and modified a previously developed recipe which we found was the best media to promote cnidarian cell survivability while also subduing microbe growth31. Using this modified media, we then monitored 123 N. vectensis cell cultures and 51 P. damicornis cell cultures. We show in both N. vectensis and P. damicornis that diverse cell types can reliably survive ex vivo for over 12 days. We also show that by using these dissociation methods, antibiotic pretreatments, and modified media that both N. vectensis and P. damicornis cell cultures have early proliferation, a high cell diversity, low rates of early microbial contamination, and consistent cell morphologies throughout the time of culturing. With these new methods, live cell methods can be developed more readily enabling the development of functional assays to better understand cnidarian cell biology.

Table 1.

Summary of previous anthozoan cell culture publications.

| Publication | Model organism(s) | Notes | Maximum viability* period |

|---|---|---|---|

| Barnay-Verdier et al. 2013 | Anemonia viridis | Tentacle tissue only | 14 days |

| Domart-Coulon et al. 2001 | Pocillopora damicornis | Calcium carbonate formation | N/A |

| Domart-Coulon et al. 2004 | Stylophora pistillata, Pocillopora damicornis | Multicellular isolates | 2 weeks |

| Domart-Coulon et al. 2004 | Pocillopora damicornis | Calcium carbonate formation | 6 days |

| Downs et al. 2010 | Pocillopora damicornis | Early microbial interference | N/A |

| Drake et al. 2018 | Stylophora pistillata | Early microbial interference | N/A |

| Estephane and Anctil 2010 | Renilla koellikeri | Cell dedifferentiation reported | 10 days |

| Frank et al. 1994 | Dendronephthya hemprichi, Heteronexia fuscescence, Favia favus, Plexaura sp., Stylophora sp., Clathraria sp., Parerythropodium sp., Milleopora sp., Porites sp. | Early microbial interference | N/A |

| Helman et al. 2008 | Xenia enlongata, Montipora digitata | Calcium carbonate formation | N/A |

| Khalesi 2008 | Sinularia flexibilis | Early microbial interference | N/A |

| Kopecky and Ostrander 1999 | Acropora micropthalma, Pocillopora damicornis, Stylophora pistillata, Seriatopora hystrix, Porties sp. | Multicellular isolates | N/A |

| Lecointe et al. 2013 | Pocillopora damicornis | Multicellular isolates | 7 days |

| Mass et al. 2012 | Stylophora pistillata | Calcium carbonate formation | N/A |

| Mass et al. 2017 | Stylophora pistillata | Calcium carbonate formation | 7 days |

| Nesa and Hidaka 2009 | Fungia sp., Pavona divaricata | Multicellular isolates | 3 days |

| Rabinowitz et al. 2015 | Nematostella vectensis | Ectodermal tissue layers | 19 days |

| Reyez Bermudez and Miller 2009 | Acropora millepora | Larvae-derived | 11 days |

| Ventura et al. 2018 | Anemonia viridis | Tentacle tissue only | 30 days |

Previous publications on anthozoan cell culture: A review of past publications that produced cnidarian cell cultures .“Notes” column indicates particular tissues preparations that were used in each study. Maximum viability is what was reported in the respective publication. “N/A” is marked for publications where viability was impossible to determine given the results. (*although the publication may report a viable time period, there was either some contamination, cell loss, or loss of cell diversity during the reported time, meaning at an unknown point the cultures were not “viable” by the standards put forth in this paper).

Methods

Pre-culture animal preparation

N. vectensis

Adult N. vectensis were maintained in glass bowls containing 0.2 μm filtered 11ppt saltwater in the dark, at room temperature. Full strength saltwater was sourced from Biscayne Bay of Miami, FL, USA and diluted using reverse osmosis fresh water to bring the final concentration to 11ppt. Animals were fed 5 days per week with freshly hatched Artemia (Utah Sea). 50% water changes were done 3 times a week33. In preparation for cell culture, animals were removed from bowls and rinsed three times with “anemone gentamicin medium” (AGM) which consists of sterile 11 ppt saltwater supplemented with 10 μg/ml Gentamicin Reagent Solution (Gibco by Life Technologies)31 (Table S1). For 3–7 days, individual anemones were isolated in AGM with daily media changes and starved. Each animal was then individually rinsed in a 2.5 μg/ml Penicillin/Streptomycin/Amphotericin B solution (PSAb) (Sigma) in 0.2 μm-filtered 11ppt saltwater and incubated at room temperature in 2.5 μg/ml PSAb for 10 min. Animals were then transferred into individual sterile 12-well tissue culture plates (VWR, Radnor, Pennsylvania) with selected media detailed below.

P. damicornis

Colonies of P. damicornis coral genotype, PAN-10, were originally collected from Saboga Island, Panama in 2005 and have been maintained at Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences culturing facilities34. The corals were maintained in an 800-gallon semi-recirculating system being constantly supplied with 10 μm-filtered sea water and were illuminated with 60 μmol·m-2·s-1 on a 12-h light/12-h dark cycle. The corals were fed using larval AP100 dry diet powder (Ziegler) twice per week. Coral tanks were cleaned twice per week to reduce algae. Just prior to starting the cell dissociation step, coral fragments approximately 1 cm in length were rinsed for 5 min with a transfer pipet using 0.2 μm-filtered full strength seawater.

Tissue dissociation and plating of cell cultures

N. vectensis

We tested several different methods of dissociation including mechanical, antibiotics-facilitated with 3% PSAb, and chemical (2% N-acetyl l-cysteine and trypsin). Of these we found that mechanical dissociation generated the most viable cells (Figure S1). For mechanical dissociation, individual anemones were treated with 7% MgCl2 in 0.2 μm-filtered 11ppt seawater and then sliced with a scalpel into tissue clumps. In some cases, the tentacle tissue and mesenterial tissue were separated with the scalpel before dissociation. This was done to demonstrate different localized cell populations with pictures (Fig. 3), however, the resultant cultures were not quantified in our study. These tissue clumps were then further dissociated by repeated pipetting using a wide bore 100 μl pipet tip to reduce cell damage. Following dissociation, cell slurries from one whole organism were concentrated into 1 ml and centrifuged three times at 100×g for 3 min, replacing supernatant with Leibovitz’s L-15 media between each centrifugation. The resulting pellet was loosened with gentle pipetting. Then 200 μl was added to 4–5 wells of a 6-well plate with 6 ml of anemone cell culture media (ACCM) or 100 μl was added to 9–10 wells of a 12-well plate with 2.5 ml ACCM. Wells without cells were used as controls to test for media contamination. The remaining clumps were left to incubate in the media and over 24 h spontaneously dissociated to individual cells (Fig. 1A). ACCM is a modified recipe of a previously published media for N. vectensis ectodermal tissue culture31. ACCM consists of 80% AGM, and 20% full strength media (FSM), which is 95% L-15 Medium, 3% FBS, 1% PSAb, and 1% HEPES Buffer. 1% Penicillin–Streptomycin-Amphotericin b (PSAb) was also added to each well along with 7.5 μg/ml Plasmocin Prophylactic(InvivoGen, San Diego, California) to reduce bacteria growth. Other media were tested, but survival rates of cells were not as high as ACCM (Fig. 2E).

Figure 3.

Cnidarian cell culture cell type diversity. (A) N. vectensis cells 48 h pd with several intact nematosomes (white arrowhead). (B) N. vectensis cells isolated only from the mesenteries 6 days pd. This cell suspension had mostly granulated round cells with dark vacuoles (black arrowhead) and large, occasionally mobile round clusters (white arrow). (C) Cells isolated only from the oral region 6 days pd. A diverse suspension of unidentified smaller round ectodermal cells (black arrowhead) along with cnidocytes (white arrowhead). (D) Proliferative N. vectensis cell culture 7 days pd with diverse cells of various shapes and sizes, including “pointed” round cells (white arrowhead) and globular cells, mostly unidentifiable based on morphology. (E) P. damicornis cell culture 21 days pd with low zooxanthellae counts, giving an observable variety of mostly unidentified host cnidarian cells in culture such as abundant rounded cells (arrowhead) (F) Diverse P. damicornis culture 25 days pd with smaller putative digestive round cells (arrowhead). (G) P. damicornis culture 28 days pd with 3 types of viable cnidocytes (arrows) (along with a piece of coral aragonite in frame) (H) P. damicornis culture 6 days pd with a large discharged cnidocyte (arrow).

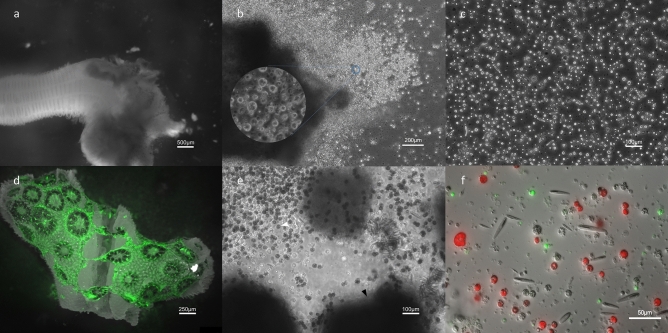

Figure 1.

Dissociation process of N. vectensis and P. damicornis tissue. (A) MgCl2 treated N. vectensis with an initial scalpel cut for mechanical dissociation. (B) N. vectensis tissue clump being spontaneously dissociated into cells in culture 24 h post-dissociation (pd). (C) Diverse N. vectensis cell suspension after full dissociation 48 h pd. (D) Green autofluorescent P. damicornis tissue being sloughed off of the skeleton 8 h into antibiotic-facilitated dissociation. (E) P. damicornis cells immediately after dissociation with intact bailed-out polyps (black arrowhead) and abundant zooxanthellae (white arrowhead). (F) Autofluorescent P. damicornis cells 12 h post-dissociation with various cell types. Red fluorescence indicates algal symbionts, Symbiodiniaceae.

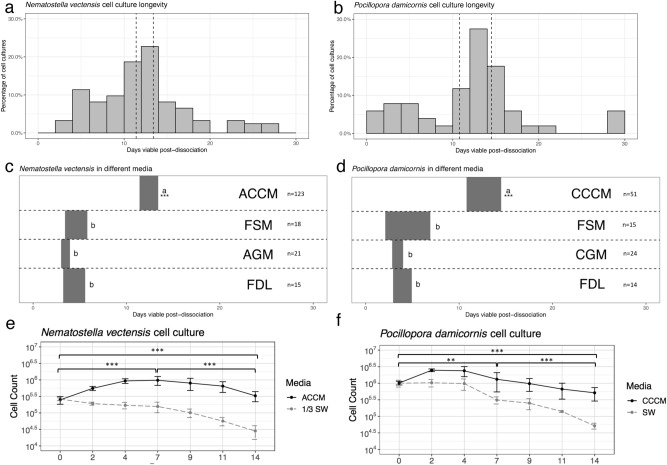

Figure 2.

Cnidarian cell culture growth and viability. (A) Distribution of N. vectensis cell culture longevity over 123 cell cultures (n = 123, binwidth = 2 days). The dashed vertical lines indicate the 95% confidence interval after a one sample t-test (11.41879, 13.39421). (B) Histogram of distributions of P. damicornis cell culture longevity over 51 cell cultures (n = 51, binwidth = 2 days). The dashed vertical lines indicate the 95% confidence interval after a one sample t-test (10.79539, 14.53794). (C,D) Comparisons of viability between culture media in N. vectensis and P. damicornis. Each grey rectangle represents the 95% confidence interval for viable days in culture for all recorded cell cultures using the listed media. Two-tailed t-test between each medium were performed, a and b represent significantly different intervals (*** = P < 0.001) (ACCM anemone cell culture medium, CCCM coral cell culture medium, FSM full strength medium, AGM anemone gentamicin medium, CGM coral gentamicin medium, FDL fish disease lab media, see supplementary figures for media formulae). (E,F) Comparison of cells counts for N. vectensis and P .damicornis maintained in seawater (11ppt seawater for N. vectensis) or cell culture media over a 14-day period. Cell counts were plotted as log10 in cells/well of culture against time (in days). Statistical significance was determined using a non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis between counts on days 0 and 7, 7 and 14, and 0 and 14 for both species. (***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01).

P. damicornis

Building on previous methods for dissociation of coral embryos, antibiotic-facilitated dissociation was used to cause expulsion of coral tissue from the adult skeleton32. P. damicornis fragments were submerged in 5–10 ml of antibiotic solution (enough to completely submerge the fragment): 2% PSAb, 7.5 μg/ml Plasmocin Prophylactic, and 30 μg/ml Gentamicin in 0.2 μm-filtered seawater in 6-well cell culture plates. The fragments incubated in this solution for 24–48 h to prevent microorganism growth and to promote the expulsion of the coral tissue from the coral skeleton (Fig. 1D). This treatment caused the sloughing off of live cells and “polyp bail-out”, which has been previously described in P. damicornis as a response to hypersalinity and toxicants35–37. Cells were confirmed to be viable with a 10% Trypan Blue (Gibco) exclusion test. Following antibiotic-facilitated dissociation, cells and the remaining skeletal fragments were plated in coral cell culture media (CCCM) that consisted of 20% FSM, 80% full strength 0.2 μm-filtered seawater with 10 μg/ml Gentamicin (CGM). After 5 days, the skeleton fragments were removed from culture wells with sterilized forceps. Cultures were further supplemented with 1% PSAb and 7.5 μg/ml Plasmocin Prophylactic.

Cell culture maintenance and viability

After 1 week, media and antibiotics were changed for N. vectensis and P. damicornis cell cultures. Following this, media and antibiotics were changed every 10 days. Cultures were observed under a microscope daily for the first week and twice a week for the remaining time of the experiment. A cell culture was deemed not viable if (1) any microbial proliferation was occurring, excluding Symbiodiniaceae, (2) if fewer than ~ 100,000 living cells remained, or (3) if more than 5% of the total cells were necrotized or fragmented. Microbial proliferation was determined visually (Fig S3). We recorded when and why each cell culture lost viability, and recognized contaminants were also recorded (Fig. 2A,B, S2).

Cell counts and viability test

Cell culture viability and cell number were recorded starting at 5 h post cell culture establishment. A 1 mL sample of cells was pipetted out of a culture and into a 1.5 mL Eppendorf tube. The contents were then centrifuged at 100×g for 3 min and the supernatant was replaced with a working concentration of Trypan blue stain (0.4%, Gibco Life Technologies). The stained cells were then transferred to a Reichert 0.1 mm deep improved Neubauer hemocytometer and total unstained cells were counted. These counts were performed in triplicate 3 times per week for the first two weeks in both species.

Results and discussion

Dissociation method affects long term cell culture viability

A total of 123 N. vectensis cell cultures and 51 P. damicornis cell cultures were tested under identical parameters and monitored for the length of their viability (Fig. 2A,B). The overall viability of the cultures was heavily dependent on the effectiveness of the tissue dissociation method. We hypothesize that the high initial cell diversity in primary cultures promotes longer cell culture viability. We define cell diversity as the number of morphologically distinct cells observed in the viable culture. However, little is understood about whether different tissue dissociation methods promote the isolation of specific populations more readily.

We found that chemical dissociation was unsuccessful in N. vectensis, but that mechanical dissociation yielded clumps of viable diverse cell types that spontaneously dissociated into sheets of individual cells (Figure S1, Fig. 1A–C). Also, for the first time we showed that adult tissue of P. damicornis is effectively dissociated using an antibiotic solution (Fig. 1D–F). The antibiotic solution caused tissue to slough off of the skeleton and after 24 h yielded a diversity of cell types (Fig. 1D–F). The process of antibiotic-facilitated dissociation for coral cell culture is a convenient innovation due to microbial mitigation and production of diverse live cells from the intact skeleton occurring concomitantly. Dissociation methods for cnidarian cell culture have been challenging due to issues with extracellular matrix strength, large amounts of mucus, and the fragility of the cells38,39. Chemical dissociation methods including trypsin and N-acetylcysteine yielded fewer viable cells, and fewer cell types due to incomplete dissociation (Figure S1). The development of the dissociation methods here are a promising breakthrough for cnidarian cell culture because they yield diverse cell types that successfully adapt to the cell culture environment quickly.

Primary cell cultures from N. vectensis and P. damicornis are viable for 12 days on average

Of the cell culture replicates produced, 54% of N. vectensis and 55% of P. damicornis cell cultures remained uncontaminated and maintained diverse cell types for > 10 days (Fig. 2A,B). On average, N. vectensis cell cultures survived for 12.3 days, while P. damicornis cell cultures averaged 12.7 days. This represents the first time that dissociated cells from combined tissues of a sea anemone or coral have been able to survive in cell culture for over 12 days without contamination. Here we used high replication and well-defined standards for viability, which we believe translates directly into “usability” for future live cell methods. Most previous studies worked with specific or intact tissues, or cultured cells in media with notable contamination. Among those studies, the highest definitive survival of individual cells derived from whole-body tissue appeared to be a maximum of 10 days24. The relatively low amount of early contamination in our cultures may be attributed to the importance of adding antibiotics at higher concentrations, as well as, the extensive rinsing and pre-treatment with antibiotics before dissociation. We also hypothesize that diluting the media to 20% allowed the cnidarian cells to outcompete any present microbes for longer periods of time. This is notable when compared to other non-diluted media tested where rapid contamination lowered viability time (Fig. 2C,D). Early contaminations were still observed on occasion, however survival up to 30 days in 3 P. damicornis cultures and 28 days in 3 N. vectensis cultures were observed (Fig. 2A,B). Why there is such variation in the sustainability of these cultures is still not understood, but differences in individual animal microbial communities could be one reason for this, however this hypothesis would need to be tested40,41.

Cell counts and microscope observations were used to determine if cultures were proliferating and cell diversity was employed as an indicator of cell culture viability. From 2 days post-dissociation, cell counts of both species showed prominent proliferation, followed by a viable cell suspension that was maintained for the remaining 12 days (Fig. 2E,F). Over a 14-day period, a higher amount of cell viability was observed for cells cultured in ACCM or CCCM than cells cultured in 0.2 μm-filtered seawater with antibiotics (Fig. 2E,F). Based on these findings, we believe that ACCM and CCCM are positively affecting cnidarian cell growth and survival, to a much better extent than seawater only or other established media (Fig. 2C,D).

Cell culture cessation was primarily due to overgrowth of Thraustochytrids, a known group of cnidarian associated Stramenopiles and historical cell culture “saboteurs”16,42. The principal limitation to long term cnidarian cell culture success is the overgrowth of microbes, and antimicrobial methods should be done as to mitigate contamination, without affecting host cell diversity. Causes of cell culture viability loss are catalogued in Figures S2 and S3. General cell culture progression from start to finish in both species is summarized in Figure S4.

A high diversity of viable cells was observed in both cultures

Using our cell culture methods, a high diversity of cells was achieved based on complete dissociation of all tissue types (Fig. 1A–F). In N. vectensis, specific cells or structures such as cnidocytes or nematosomes (mobile multicellular structures that contains cnidocytes and are unique to the genus Nematostella), could be readily identified from whole-body cultures (Fig. 1A). To further demonstrate how cells of various tissue sources could be cultured with these methods, cultures with only mesenteries and cultures with only oral/tentacle tissue were created. Putative digestive cells were isolated in cultures using only tissue from the mesenteries and small cnidocytes and epidermal cells were isolated from tentacle and oral tissue. (Fig. 3B,C). Each of these cell types were also observed in whole-body cultures and survived up to 28 days (Fig. 3D). Nematosomes generally remained mobile in culture for up to 5 days until they dissociated into almost entirely cnidocytes, revealing much about their cellular structure.

Within P. damicornis cell cultures, immediately following dissociation, cnidocytes and Symbiodiniaceae-containing cells were the most recognizable cell types (Fig. 1E), however diverse round and granular cell types were also abundant even up to 30 days post-dissociation (Fig. 3E). After 5 days post-dissociation, P. damicornis cell cultures showed a high cell diversity due to complete cell dissociation from the skeleton (Fig. 3E,F). The presence of diverse cell types, proliferation, and cell motility in both N. vectensis and P. damicornis is indicative of a viable cell culture that will be useful for short term functional assays.

Conclusions

Previous studies using cnidarian cell culture have been challenging due to incomplete dissociation methods, cell culture media(s) that were not promoting proliferation, and high contamination, especially from cultures derived from multiple tissue layers. This work represents the first time that fully dissociated whole-body primary cells of cnidarians have been shown to proliferate, maintain cell diversity, and remain viable for an average of approximately 12 days without contamination. The high number of cell culture replications performed in this study show that these cultures can be readily produced. The reliable production of cell cultures from whole body cnidarian tissues is valuable because it allows for the study of independent functions of cells from all tissues. These cultures are useful for the observation and manipulation of cell types in the context of other cell types, or for functionally identifying a putative unknown cell type. Accessible cnidarian primary cell cultures of all tissue sources are an innovative and convenient resource that broadens research avenues for cnidarian cell biology.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

Authors would like to thank Madison Emery for permission to use her photo of an adult N. vectensis. Authors would also like to thank Dr. Michael Schmale and members of his laboratory, in particular, Dr. Pat Gibbs, for assistance in cell culture technique, and microscope access. We also thank Phil Gillette for assistance with the coral aquaculture. Lastly, authors would like to thank the reviewers for their helpful comments and suggestions.

Author contributions

N.T.K. provided guidance on overall project design, intellectual ideas, and analysis. J.D.N. and N.T.K. conceived the project design. J.D.N. and M.T.C. performed cell culture methods and analysis. All authors participated in the drafting and approval process of this manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by NSF Award #: 1951826 and Revive and Restore Catalyst Science Fund. JDN: was funded by the University of Miami Linda Farmer Award and University of Miami Small Undergraduate Research Grant Experience Award.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of this Article contained errors. Modifications have been made to the Introduction, Table 1 and Reference List. Full information regarding the corrections made can be found in the correction for this Article.

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

5/26/2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1038/s41598-021-90241-3

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-021-83549-7.

References

- 1.Freshney, R.I. Culture of Animal Cells. (Alan R Liss. Inc, 1987).

- 2.Yoshino TP, Bickham U, Bayne CJ. Molluscan cells in culture: Primary cell cultures and cell lines. Can. J. Zool. 2013;91:391–404. doi: 10.1139/cjz-2012-0258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vandepas LE, Warren KJ, Amemiya CT, Browne WE. Establishing and maintaining primary cell cultures derived from the ctenophore Mnemiopsis leidyi. J. Exp. Biol. 2017;220:1197–1201. doi: 10.1242/jeb.152371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hurton LV, Berkson JM, Smith SA. Selection of a standard culture medium for primary culture of Limulus polyphemus amebocytes. In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol. Anim. 2005;41:325–329. doi: 10.1007/s11626-005-0003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frank U, Rabinowitz C, Rinkevich B. In vitro establishment of continuous cell cultures and cell lines from ten colonial cnidarians. Mar. Biol. 1994;120:491–499. doi: 10.1007/BF00680224. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amiel AR, Johnston H, Chock T, Dahlin P, Iglesias M, Layden M, Rottinger E, Martindale MQ. A bipolar role of the transcription factor ERG for cnidarian germ layer formation and apical domain patterning. Dev. Biol. 2017;430:346–361. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2017.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DuBuc TQ, Traylor-Knowles N, Martindale MQ. Initiating a regenerative response; cellular and molecular features of wound healing in the cnidarian Nematostella vectensis. BMC Biol. 2014;12:24. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-12-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ventura P, Toullec G, Fricano C, Chapron L, Meunier V, Röttinger E, Furla P, Barnay-Verdier S. Cnidarian primary cell culture as a tool to investigate the effect of thermal stress at cellular level. Mar. Biotechnol. 2018;20:144–154. doi: 10.1007/s10126-017-9791-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lecointe A, Cohen S, Gèze M, Djediat C, Meibom A, Domart-Coulon I. Scleractinian coral cell proliferation is reduced in primary culture of suspended multicellular aggregates compared to polyps. Cytotechnology. 2013;65:705–724. doi: 10.1007/s10616-013-9562-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosental B, Kozhekbaeva Z, Fernhoff N, Tsai JM, Traylor-Knowles N. Coral cell separation and isolation by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) BMC Cell Biol. 2017;18:30. doi: 10.1186/s12860-017-0146-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gold DA, Jacobs DK. Stem cell dynamics in Cnidaria: Are there unifying principles? Dev. Genes. Evol. 2013;223:53–66. doi: 10.1007/s00427-012-0429-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cai X, Zhang Y. Marine invertebrate cell culture: A decade of development. J. Oceanogr. 2014;70:405–414. doi: 10.1007/s10872-014-0242-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rinkevich B. Cell cultures from marine invertebrates: Obstacles, new approaches and recent improvements. J. Biotechnol. 1999;70:133–153. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1656(99)00067-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rinkevich B. Cell cultures from marine invertebrates: New insights for capturing endless stemness. Mar. Biotechnol. 2011;13:345–354. doi: 10.1007/s10126-010-9354-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lu Q, Ni S, Guo H. Advances in the tissue and cell culture of corals. Adv. Mar. Sci. 2016;3:43–47. doi: 10.12677/AMS.2016.32007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Siboni N, Rasoulouniriana D, Ben-Dov E, Kramarsky-Winter E, Sivan A, Loya Y, Hoegh-Guldberg O, Kushmaro A. Stramenopile microorganisms associated with the massive coral Favia sp. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 2010;57:236–244. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.2010.00469.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Har JY, Helbig T, Lim JH, Fernando SC, Reitzel AM, Penn K, Thompson JR. Microbial diversity and activity in the Nematostella vectensis holobiont: Insights from 16S rRNA gene sequencing, isolate genomes, and a pilot-scale survey of gene expression. Front. Microbiol. 2015;6:818. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barnay-Verdier, S., Dall’osso, D., Joli, N., J., Olivré, J., Priouzeau, F., Zamoum, T., Merle, P., Furla, P. Establishment of primary cell culture from the temperate symbiotic cnidarian, Anemonia viridis. Cytotechnology65, 697–704 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Domart-Coulon IJ, Elbert DC, Scully EP, Calimlim PS, Ostrander GK. Aragonite crystallization in primary cell cultures of multicellular isolates from a hard coral, Pocillopora damicornis. PNAS. 2001;98:11885–11890. doi: 10.1073/pnas.211439698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Domart-Coulon I, Tambutté S, Tambutté E, Allemand D. Short term viability of soft tissue detached from the skeleton of reef-building corals. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2004;309:199–217. doi: 10.1016/j.jembe.2004.03.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Domart-Coulon IJ, Sinclair CS, Hill RT, Tambutté S, Puverel S, Ostrander GK. A basidiomycete isolated from the skeleton of Pocillopora damicornis (Scleractinia) selectively stimulates short-term survival of coral skeletogenic cells. Mar. Biol. 2004;144:583–592. doi: 10.1007/s00227-003-1227-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Downs CA, Fauth JE, Downs VD, Ostrander GK. In vitro cell-toxicity screening as an alternative animal model for coral toxicology: Effects of heat stress, sulfide, rotenone, cyanide, and cuprous oxide on cell viability and mitochondrial function. Ecotoxicology. 2010;19:171–184. doi: 10.1007/s10646-009-0403-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Drake JL, Schaller MF, Mass T, Godfrey L, Fu A, Sherrell RM, Rosenthal Y, Falkowski PG. Molecular and geochemical perspectives on the influence of CO2 on calcification in coral cell cultures. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2018;63:107–121. doi: 10.1002/lno.10617. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Estephane D, Anctil M. Retinoic acid and nitric oxide promote cell proliferation and differentially induce neuronal differentiation in vitro in the cnidarian Renilla koellikeri. Dev. Neurobiol. 2010;70:842–852. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Helman Y, Natale F, Sherrell RM, Le Lavigne M, Starovoytov V, Gorbunov MY, Falkowski PG. Extracellular matrix production and calcium carbonate precipitation by coral cells in vitro. PNAS. 2007;105:54–58. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710604105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khalesi MK. Cell cultures from the symbiotic soft coral Sinularia flexibilis. In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol. Anim. 2008;44:330–338. doi: 10.1007/s11626-008-9128-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kopecky EJ, Ostrander GK. Isolation and primary culture of viable multicellular endothelial isolates from hard corals. In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol. Anim. 1999;35:616–624. doi: 10.1007/s11626-999-0101-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mass T, Drake JL, Haramaty L, Rosenthal Y, Schofield OME, Sherrell RM, Falkowski PG. Aragonite precipitation by “proto-polyps” in coral cell cultures. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:4. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mass T, Drake JL, Heddleston JM, Falkowski PG. Nanoscale visualization of biomineral formation in coral proto-polyps. Curr. Biol. 2017;27:3191–3196. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2017.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nesa B, Hidaka M. High zooxanthella density shortens the survival time of coral cell aggregates under thermal stress. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2008;368:81–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jembe.2008.10.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rabinowitz C, Moiseeva E, Rinkevich B. In vitro cultures of ectodermal monolayers from the model sea anemone Nematostella vectensis. Cell Tissue Res. 2016;366:693–705. doi: 10.1007/s00441-016-2495-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reyes-Bermudez DJ, Miller AA. In vitro culture of cells derived from larvae of the staghorn coral Acropora millepora. Coral Reefs. 2009;28:859–864. doi: 10.1007/s00338-009-0527-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stefanik DJ, Friedman LE, Finnerty JR. Collecting, rearing, spawning and inducing regeneration of the starlet sea anemone, Nematostella vectensis. Nat. Protoc. 2013;8:916–923. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cunning R, Bay RA, Gillette P, Baker AC, Traylor-Knowles N. Comparative analysis of the Pocillopora damicornis genome highlights the role of the immune system in coral evolution. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:1–10. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-34459-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fordyce, A. J., Camp, E. F., & Ainsworth, T. D. Polyp bailout in Pocillopora damicornis following thermal stress [version 2; peer review: 2 approved]. F1000Research6, 687 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Wecker P, Lecellier G, Guiber I, Zhou Y, Bonnard I, Lecellier VB. Exposure to the environmentally-persistent insecticide chloridecone induces detoxification genes and causes polyp bail-out in the coral P. damicornis. Chemosphere. 2018;195:190–200. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.12.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chuang, P. S., & Mitarai, S. (2020). Signaling pathways in the coral polyp bail-out response. Coral Reefs (2020).

- 38.Schmid V, Ono SI, Reber-Müller S. Cell-substrate interactions in Cnidaria. Microsc. Res. Tech. 1999;44:254–268. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0029(19990215)44:4<254::AID-JEMT5>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Peng SE, Luo YJ, Huang HJ, Lee IT, Hou LS, Chen WNU, Chen CS. Isolation of tissue layers in hermatypic corals by N-acetylcysteine: Morphological and proteomic examinations. Coral Reefs. 2008;27:133–142. doi: 10.1007/s00338-007-0300-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brown, T., Otero, C., Grajales, A., Rodriguez, E., & Rodriguez-Lanetty, M. (2017). Worldwide exploration of the microbiome harbored by the cnidarian model, Exaiptasia pallida (Agassiz in Verrill, 1864) indicates a lack of bacterial association specificity at a lower taxonomic rank. PeerJ5, e3235 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Dunphy CM, Gouhier TC, Chu ND, Vollmer SV. Structure and stability of the coral microbiome in space and time. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:1–13. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-43268-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kramarsky-Winter E, Harel M, Siboni N, Ben Dov E, Brickner I, Loya Y, Kushmaro A. Identification of a protist-coral association and its possible ecological role. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2006;317:67–73. doi: 10.3354/meps317067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Knowlton, N. & Jackson, J.B.C. Shifting Baselines, Local Impacts, and Global Change on Coral Reefs. PLoS Biol6(2): e54. 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060054 (2008) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Bellwood, D., Hughes, T., Folke, C. et al. Confronting the coral reef crisis. Nature429, 827–833. 10.1038/nature02691 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author.