Abstract

Although interferon α (IFNα) and anti-angiogenesis antibodies have shown appropriate clinical benefit in the treatment of malignant cancer, they are deficient in clinical applications. Previously, we described an anti-vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2)-IFNα fusion protein named JZA01, which showed increased in vivo half-life and reduced side effects compared with IFNα, and it was more effective than the anti-VEGFR2 antibody against tumors. However, the affinity of the IFNα component of the fusion protein for its receptor-IFNAR1 was decreased. To address this problem, an IFNα-mutant fused with anti-VEGFR2 was designed to produce anti-VEGFR2-IFNαmut, which was used to target VEGFR2 with enhanced anti-tumor and anti-metastasis efficacy. Anti-VEGFR2-IFNαmut specifically inhibited proliferation of tumor cells and promoted apoptosis. In addition, anti-VEGFR2-IFNαmut inhibited migration of colorectal cancer cells and invasion by regulating the PI3K–AKT–GSK3β–snail signal pathway. Anti-VEGFR2-IFNαmut showed superior anti-tumor efficacy with improved tumor microenvironment (TME) by enhancing dendritic cell maturation, dendritic cell activity, and increasing tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells. Thus, this study provides a novel approach for the treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer, and this design may become a new approach to cancer immunotherapy.

KEY WORDS: Anti-VEGFR2, IFNαmut, Tumor microenvironment, Colorectal cancer, Liver metastasis, Cancer immunotherapy

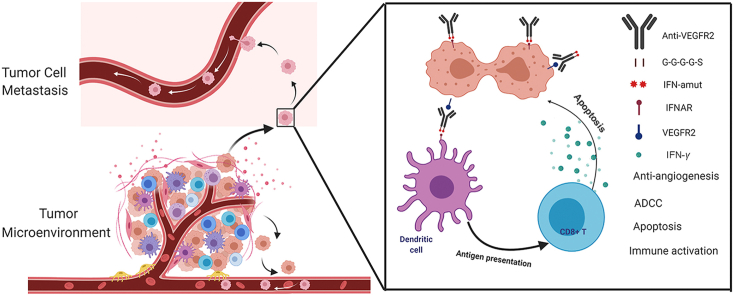

Graphical abstract

Anti-VEGFR2-IFNαmut exhibits potent anti-tumor and anti-metastasis activity by regulating the tumor microenvironment.

1. Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer, and it was the second leading cause of mortality in 2018, according to global cancer statistics1. The main cause of colorectal cancer death is liver metastasis, and half of colorectal cancer patients had liver metastases before or after surgery2. In recent years, anti-VEGF/VEGFR therapeutic antibodies have prolonged the survival of CRC patients while exhibiting a low toxic profile3,4. Ramucirumab, which is a fully humanized monoclonal antibody (mAb) that targets the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2), was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Admnistration (FDA) for the treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer in April 20155,6. The VEGF/VEGFR2 signaling pathway plays a major role in physiological and pathological angiogenesis, and the angiogenesis in cancer is essential for tumor growth and metastasis7, 8, 9. However, as single agent, these anti-VEGF/VEGFR2 antibodies have limited efficacy against CRC. In addition, there were preclinical reports that VEGF inhibitors reduced primary tumor growth, but promoted tumor invasiveness and metastasis10, 11, 12, 13, 14. Hence, it is important to explore the mechanisms of antibody action and to develop novel strategies to enhance their efficacy against invasiveness and metastasis and to minimize undesirable side-effects. Hypoxia may play an important role in invasiveness and metastasis, and some strategies to address hypoxia that was induced by anti-angiogenesis have been developed, such as the small molecule inhibitor of HIF-α15,16. However, we speculate that hypoxia is not the sole cause of invasiveness and metastasis, and the VEGF/VEGFR2 inhibitor may also alter the tumor microenvironment (TME) to encourage invasiveness and metastasis.

The TME, which consists of resident fibroblasts, endothelial cells, pericytes, leukocytes, extracellular matrix, immune cells17,18, and the immune cells infiltrated in the solid tumor such as macrophages or neutrophils play a significant role in the metastasis of malignancy19, 20, 21, 22. Therefore, we hypothesized that targeting a molecule that can regulate the tumor immune microenvironment along with anti-VEGFR2 may solve the problem of invasiveness and metastasis that is induced by VEGF/VEGFR2 inhibitor.

IFNα can activate the immune system of cancer patients, enhance the cytotoxicity of NK cells, induce the generation and survival of CTLs and memory CD8+ T cells, and promote the expression of MHC molecules in dendritic cell maturation in tumors23,24. IFNα also exhibits direct cytotoxicity by inhibiting the proliferation of tumor cells and by promoting apoptosis of those cells25. In addition, IFNα reduced tumor metastasis26,27. On the basis of these findings, the combination therapy of the anti-VEGF antibody bevacizumab with IFNα was approved by the FDA in 2009 as a first-line treatment for metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC)28, 29, 30, 31.

In previous studies, we fused IFNα2 with anti-VEGFR2 to produce a fusion antibody, named JZA01, and demonstrated that it had a good anti-tumor effect in metastatic CRC. In addition, JZA01 enhanced antigen presentation and promoted the maturation of dendritic cells32. However, we found that the affinity of IFNα2 for its receptor IFNAR1 and its direct cytotoxicity was decreased in JZA01. Because there are reports that IFNs with higher affinity for IFNAR may be better anticancer therapeutics33, we mutated IFNα to produce a higher affinity IFNα-mutant and fused it with anti-VEGFR2 to produce JZA02 in this study. We found that the affinity of JZA02 for IFNAR1 increased five times compared with JZA01, and it had improved anti-tumor efficacy compared with JZA01 both in vitro and in vivo. Moreover, in the mouse model for colorectal cancer liver metastasis, JZA02 inhibited the activation of the PI3K-AKT-GSK3β signaling pathway to inhibit liver metastasis, and it regulated the TME more efficiently by promoting dendritic cell maturation and by enhancing the infiltration of CD8+ T cells.

In summary, we have characterized a novel fusion protein, JZA02, and its superior anti-tumor and anti-metastasis properties against CRC were also shown both in vivo and in vitro.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cell culture and animals

The Chinese hamster ovary cell line CHO-pro (Amprotein Co., Ltd., Hangzhou, China) was cultured in IMDM medium (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) supplemented with 5% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco, Auckland, New Zealand). The human colorectal cancer cell lines HCT-116 and SW620 obtained from the cell bank of the Chinese Academy of Science (Shanghai, China) were cultured in 1640 medium (Gibco). The human liver cell line HL-7702 were preserved in our lab and cultured in DMEM medium (high glucose) that contained 10% (v/v) FBS. All peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) healthy donors gave informed consent for this study, and it was approved by the Ethical Committee of China Pharmaceutical University (Nanjing, China). The nude mice were purchased from Comparative Medicine Centre of Yangzhou University (Yangzhou, China) and were fed in a specific pathogen-free (SPF) environment.

2.2. The production of HCT-116-Luc cells and HCT-116-Luc-LM3 cells

The packaging plasmid, pHBLV-CMVIE-ZsGreen-T2A-Luc (Hanbio, Shanghai, China), helper plasmids, PSPAX2 and PMD2G, were cotransfected to 293T cells with LipoFiter (Hanbio). Lentivirus-containing supernatants were harvested 48 h after transfection, and recombinant lentiviruses were concentrated by ultracentrifugation. Then, the lentiviruses were added to the HCT-116 cells, and the transfected HCT-116 cells expressed green fluorescent protein (GFP) and luciferase after 48 h. Transfected HCT-116 cells were enriched by FACS sorting through a GFP tag with a purity >90%, and the sorted cells were diluted into a single cell suspension through continuous dilution. We obtained 10 clones with stable, highly expressed GFP and luciferase, which was verified by bioluminescence and reporter assays. The highly metastatic tumor variant HCT-116-Luc-LM3 cells were obtained by serial transplantation of liver metastatic clones. Briefly, liver tumor masses were minced into small pieces, digested with collagenase/hyaluronidase solution (Stem Cell Technologies, Vancouver, Canada) at 37 °C until a single-cell suspension was obtained, and cultured as described previously. Metastatic clones were tested for luciferase activity to confirm their cellular origin. The cells were re-injected into the spleen until a third-generation metastasis was achieved.

2.3. Analysis of binding affinity

The binding affinity of JZA01 and JZA02 to human IFNAR1 was measured with Biacore X100 (GE Healthcare, Sweden). Anti-human IgG (Fc) antibody was immobilized on sensor chip CM5 using a Human Antibody Capture Kit (GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden). After JZA01 and JZA02 were captured, IFNAR1 was injected at different concentrations into a running buffer (HBS-EP, pH 7.4). One flow cell of the sensor chip was set as a control. The captured antibody–analyte complex was removed by a regeneration solution (3 mol/L magnesium chloride). The association rate constant ka and dissociation rate constant kd were calculated and analyzed using the bivalent analyte model, and the equilibrium dissociation constant (KD) was calculated according to Eq. (1):

| (1) |

In addition, the binding affinity of JZA02 to tyrosine KDR (human VEGFR2) was measured as described previously.

2.4. Cell proliferation assay

Cells were plated onto a 96-well plate with 4 × 103 cells/well. After overnight starvation and incubation with different concentrations of treatments at 37 °C for 72 h, cell proliferation was quantified by a MTT assay. Inhibition (%) was calculated as Eq. (2):

| (2) |

2.5. Apoptosis assay

Colorectal cancer cell HCT-116 and SW620 were incubated in 6-well plate with different treatments (JZA02 100 nmol/L, JZA01 100 nmol/L, and IFNα 200 nmol/L) at 37 °C for 48 h, the supernatant was removed, and cells were washed three times with PBS followed by staining with annexin V-FITC and propidium iodide (PI). After being washed by PBS three times, cells were analyzed by flow cytometry to distinguish populations of early apoptotic (Annexin V+/PI–), late apoptotic (Annexin V+/PI+), and necrotic (Annexin V–/PI+) cells using an Annexin V/PI Apoptosis Assay Kit (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China). The percentage of apoptotic cells was calculated as the sum of the percentages of early apoptotic and late apoptotic cells.

2.6. Cell invasion assay

For invasion assays, 1 × 104 HCT-116 cells suspended in 100 μL RPMI 1640 media supplemented with 1% (v/v) FBS and different treatments (100 nmol/L of JZA02 or JZA01, or 200 nmol/L IFNα) were incubated in the upper well of 24-well Transwell chambers (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA), which were pretreated with matrigel (BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA, USA). The lower chambers were filled with 600 μL of RPMI 1640 media that contained 5% (v/v) FBS. After a 12–24 h incubation, the upper cells were removed, and the lower cells were fixed with 4% polyoxymethylene for 20 min and then stained with 1% (w/v) crystalline violet before being photographed under an OLYMPUS inverted microscope at 100× magnification. The number of invasive cells was determined with the Image-Pro-Plus program according to Eq. (3):

| (3) |

2.7. Scratch assay

HCT-116 cells (2 × 105 cells/well) that were suspended in RPMI 1640 media that contained 5% (v/v) FBS were incubated in a 12-well plate until they were adherent. A straight line was drawn in the middle of each well with a 1 mL tip after removing the supernatant. An aliquot of 1640 media supplemented with different treatments (100 nmol/L JZA02 or JZA01, or 200 nmol/L IFNα) was then added into corresponding wells. Images were taken using an OLYMPUS inverted microscope at 100× magnification. The length of migration was analyzed using the Image-Pro-Plus program according to Eq. (4):

| (4) |

2.8. MHC class I and MHC class II expression on the tumor surface

HCT-116 or SW620 cells (3 × 105 cells/well) were cultured in 6-well plates at 37 °C with different treatments (JZA00 50 nmol/L, JZA01 50 nmol/L, or IFNα 100 nmol/L) for 48 h. After that, cells were incubated with anti-MHC class I (Bioscience, 560965) antibody and anti-MHC class II (Bioscience, 560943) antibody for 1 h before being analyzed by flow cytometry.

2.9. Maturation of dendritic cells

Mononuclear cells and immature dendritic cells were isolated from human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (hPBMCs) and cultured in AIM-V medium (Gibco, 087-0112DK) that contained IL-4 (800 U/mL) and GM-CSF (150 ng/mL) for 4 days. Half of the medium was changed every 2 days. Different treatments (JZA00 50 nmol/L, JZA01 50 nmol/L, and IFNα 100 nmol/L) were given on the 4th day for 48 h. After that, cells were incubated with different antibodies (anti-CD80, Biosciences 560925; anti-CD86, Bioscience 560956; anti-MHC class I, Bioscience 560965; and anti-MHC class II, Bioscience 560943) for 1 h in PBS that contained 2% FBS and detected by flow cytometry.

2.10. Anti-tumor efficacy in xenograft tumor model

Colorectal cancer xenograft model was established by injecting HCT-116 cells (1 × 107) subcutaneously into BALB/c nude mice (4–6 weeks old, Yangzhou University Comparative Medicine Centre, Yangzhou, China). A total of 25 HCT-116-bearing mice were divided into five groups (five mice/group): control group, JZA01 group (1 mg/kg), JZA02 group (1 mg/kg), IFNα group (1 mg/kg) and JZA00+IFNα group (1 mg/kg+0.2 mg/kg). All treatments were administered twice a week by tail vein injection from Day 0 to Day 36. Tumor volumes were calculated using the formula Eq. (5):

| (5) |

where L is longer diameter of tumor, W is shorter diameter of vertical direction. The mice were sacrificed 36 days after treatment, and tumors were prepared for immunohistochemistry (IHC) and immunofluorescence (IF) analysis. Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tumor tissues were cut into 5 μm sections. For IHC staining, the sections were incubated with anti-Ki67, anti-CD8 antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, Boston, MA, USA), then horseradish peroxidase-labeled secondary antibody and analyzed with the Vectastain ABC Kit (Dako, Copenhagen, Denmark). For IF staining, the sections were incubated with anti-IFNγ (Abcam, Cambridge, UK), and slides were mounted with Vectashield mounting media contained DAPI before being analyzed under a fluorescence microscope. Tumor sections were viewed and photographed using a Zeiss Axio Vert A1 microscope (Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY, USA).

All animal experiments were conducted under protocols approved by the Ministry of Health of the People's Republic of China (Document No. 55, 2001) and the Guidelines for the Care and in accordance with the Provision and General Recommendation of Chinese Experimental Animals Administration Legislation and approved by the Science and Technology Department of Jiangsu Province, China [SYXK (SU) 2016–0011].

2.11. In vivo experimental model of liver metastasis of colorectal cancer

BALB/c nude mice (4–6 weeks old) were fed in the SPF environment. Mice were anesthetized using 3.8% (w/v) chloral hydrate (10 μL/g), and an incision was made in the middle of the abdomen. HCT-116-Luc-LM3 cells (5×106) that stably expressed luciferase were injected into mice spleen. A total of 35 surged mice were divided randomly into seven groups (five mice/group): PBS group, ramucirumab group (1.5 mg/kg), oxaliplatin group (5 mg/kg), JZA02 high dose group (1.5 mg/kg), JZA02 low dose group (1.0 mg/kg), JZA00 combined with IFNα group (1.5 mg/kg+0.2 mg/kg), and high dose JZA02 combined with oxaliplatin (1.5 mg/kg+5 mg/kg). Liver metastases were monitored using bioluminescence imaging. Briefly, anesthetized mice were injected intraperitoneally with 200 μL of 15 mg/mL d-luciferin potassium salt (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) dissolved in sterile PBS. Bioluminescent images were acquired using an IVIS Imaging System (Xenogen, Alameda, CA, USA) 15 min after intraperitoneal injection of d-luciferin potassium salt. Analyses were performed with Living image software (Xenogen). At the end, mice were sacrificed, and the livers were used for Hematoxylin-eosin (HE) staining, IHC, and IF staining.

2.12. Statistical analysis

All data were indicated as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Data were compared using the one-way ANOVA, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software (San Diego, CA, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Construction and characterization of JZA02

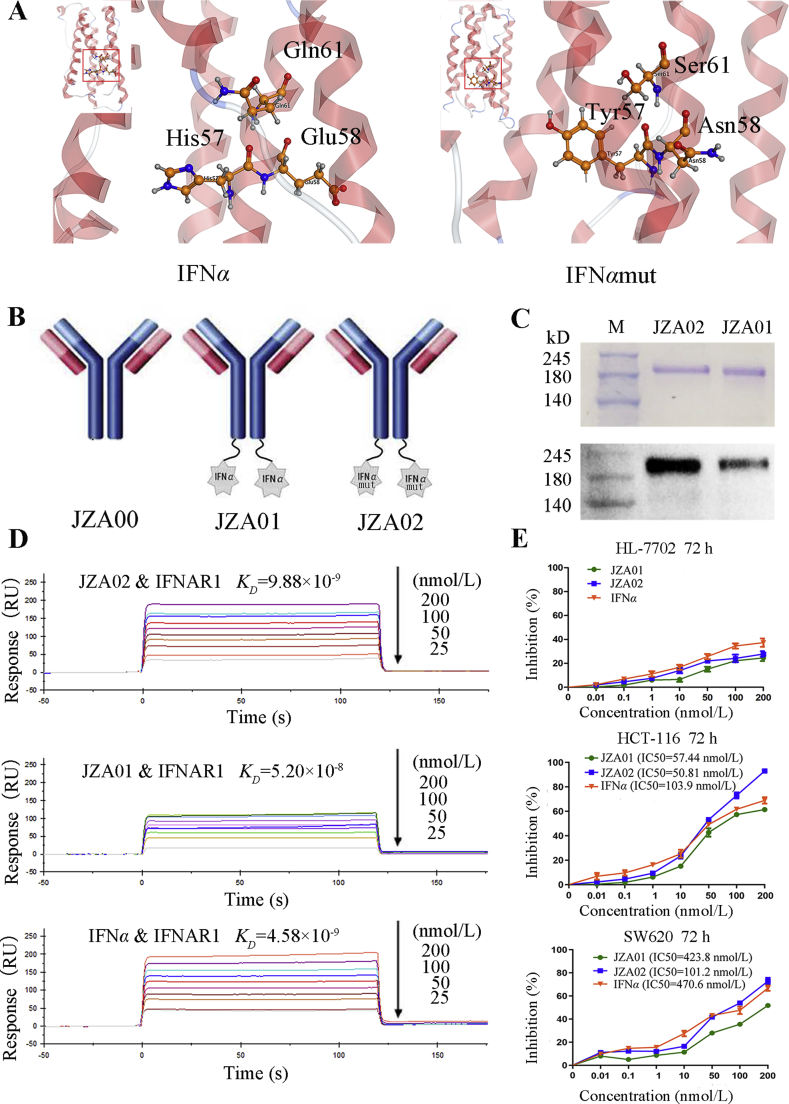

Overlap polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was used to produce IFNαmut with the mutations H57Y, E58N, and Q61S, and fused the IFNαmut to the carboxy terminus of the H chain of JZA00 using a G4S linker to obtain a fusion antibody, JZA02 (Fig. 1A and B). Non-reducing SDS-PAGE electrophoresis and Western blot analysis with anti-human IFNα confirmed that the protein was assembled correctly and was of the appropriate molecular weight (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1.

Construction and characterization of JZA02. (A) 3-D structural model of IFNα and IFNαmut. MOE was be used to build the 3-D model of IFNα and IFNαmut. (B) Diagram of JZA01 and JZA02. IFNα or IFNαmut was linked to the C-terminal of the H-chain of JZA00 with a G4S linker using overlap PCR. (C) SDS-PAGE analysis of JZA02 followed by either Coomassie blue staining or Western blot analysis with anti-IFNα antibody show that it was intact and assembled properly. (D) The binding affinity of immobilized JZA02, JZA01, or IFNα with IFNAR1 was determined with the Biacore system. The association rate increased with increasing concentration of the IFNAR1 (from bottom to top), which ranged from 0.78125 to 200 nmol/L. The complex dissociated when buffer was flowed through for 120 s. (E) HL-7702 cells, HCT-116 cells, and SW620 cells were treated with varying concentrations of IFNα, JZA01, or JZA02 for 72 h, respectively, and a MTT assay was used to detect the surviving cells. Inhibition of proliferation was plotted relative to the proliferation of untreated controls which was set to 100%.

3.2. JZA02 had a higher affinity with IFNAR1 than JZA01 did

Previously, JZA01 was shown specifically bound to VEGFR226. The binding affinity of IFNAR1 to immobilized JZA02 or JZA01 was evaluated by Biacore (GE), and the affinity was calculated using the 1:1 binding model (Fig. 1D). JZA02 exhibited high affinity for IFNAR1 (KD = 9.88 × 10−9 mol/L), which was comparable to that of IFNα (KD = 4.58 × 10−9 mol/L) and greater than that of JZA01 (KD = 5.20 × 10−8 mol/L).

3.3. JZA02 inhibited proliferation and promoted apoptosis of colorectal cancer cells

To study the activity of JZA02, we evaluated its effects on inhibiting proliferation and promoting apoptosis of colorectal cancer cells. The selective cytotoxicity of JZA02 and JZA01 was assessed on VEGFR2-positive cell lines, such as HCT-116 and SW620, and VEGFR2-negative cell line HL-7702 by MTT assay. JZA02 and JZA01 exhibited significant anti-proliferative activity on HCT-116 and SW620 in a dose-dependent manner, and the inhibition in growth of the two cell lines treated with JZA02 was higher than JZA01 and was similar to that of IFNα (Fig. 1E). Caco-2 cells and HT-29 were treated with the same procedure, and the result was similar to that with HCT-116 and SW620 cells (Supporting Information Fig. S1A), but JZA02 and JZA01 showed no cytotoxicity in normal cell line HL-7702 (Fig. 1E). To evaluate the ability of JZA02 and JZA01 to induce CRC apoptosis, HCT-116 and SW620 cells were treated with 100 nmol/L JZA02, JZA01, or 200 nmol/L IFNα for 48 h and examined by flow cytometry following Annexin V/PI staining (Fig. 2A). There was more apoptosis following the 72-h treatment with 100 nmol/L JZA02 than with 100 nmol/L JZA01 for both cell lines (Fig. 2B and Fig. S1B). In conclusion, JZA02 was more effective than JZA01 and IFNα in inhibiting proliferation and in promoting apoptosis of VEGFR2-positive cell lines, which might be attributed to the non-targeting property of free recombinant IFNα. No significant difference was observed between treatments using VEGFR2-negative cell line HL-7702.

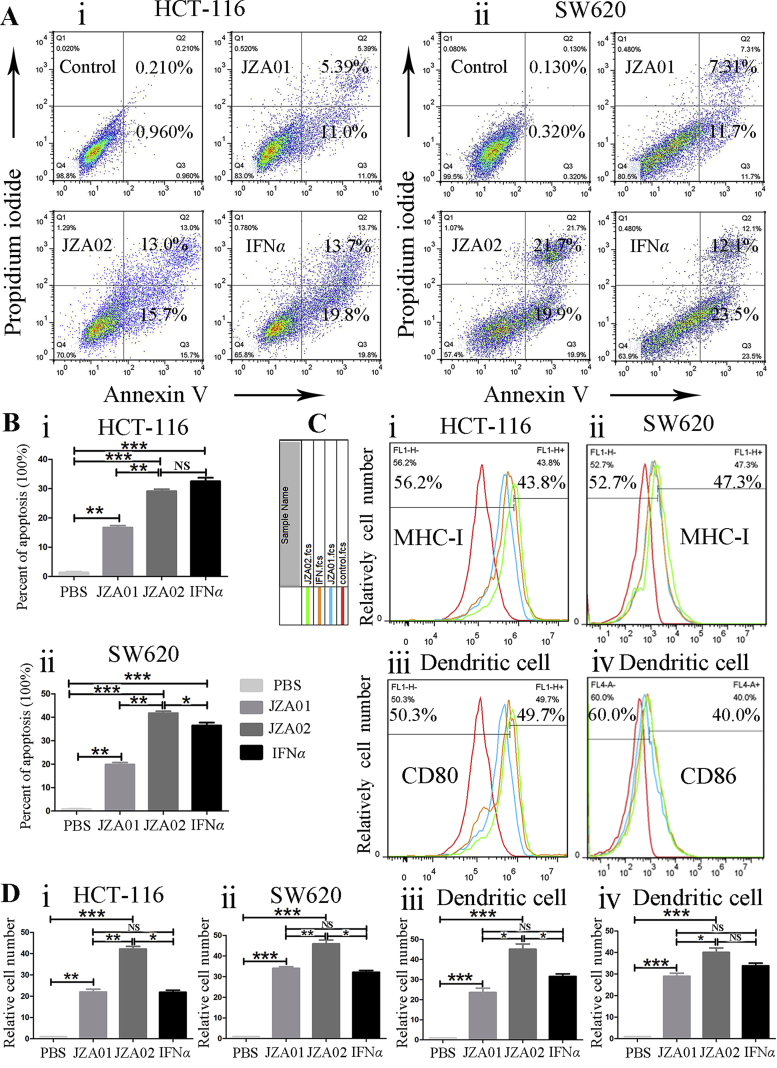

Figure 2.

JZA02 promoted apoptosis and enhanced the maturation and activity of dendritic cells. (A) JZA02 induced apoptosis of HCT-116 and SW620. HCT-116 and SW620 cells were incubated with 100 nmol/L JZA01, 100 nmol/L JZA02, or 200 nmol/L IFNα for 48 h and analyzed by flow cytometry following staining with Annexin V-FITC and PI. (B) Annexin V positive cells in Q2 and Q3 were considered apoptotic and are shown quantitatively as the mean ± SD, n = 3; ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001. (C) Flow cytometry assay of the expression of MHC class I of HCT-116 and SW620 cells under different treatments (JZA01 100 nmol/L, JZA02 100 nmol/L, or IFNα 200 nmol/L) for 48 h. Immature dendritic cells were isolated from non-activated hPBMCs and incubated under different treatments for 72 h. The expressions of CD80 and CD86 were detected by flow cytometry assay. The red, green, orange, and blue lines represent PBS treatment, JZA02 treatment, IFNα treatment, and JZA01 treatment, respectively. (D) The results in (C) are presented as the mean ± SD, n = 3; ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001.

3.4. JZA02 treatment enhanced dendritic cell maturation and activity

To compare the immune activation function of JZA01 and JZA02, cells were treated with 100 nmol/L for 48 h, and the MHC class I expression was evaluated. For both HCT-116 and SW620 cell lines, expression of MHC I treated with JZA02 was higher than in the PBS-, JZA01-, or IFNα-treated groups, and the expression of MHC I on the surface of both cell lines was similar after JZA01 or IFNα treatment (Fig. 2C and D). There was a small increase in MHC class II expression after JZA02, JZA01, or IFNα treatments (Fig. S1C). To explore the ability of JZA02 to activate dendritic cells, immature dendritic cells were separated from mononuclear cells that were isolated from hPBMCs, and were cultured in AIM-V media which contained IL-4 (800 U/mL) and GM-CSF (150 ng/mL) for 4 days. These cells were then incubated with JZA02 (50 nmol/L), JZA01 (50 nmol/L), or IFNα (100 nmol/L) for 48 h. Flow cytometry was then used to detect the expression of CD80, CD86 (Fig. 2C), MHC-I, and MHC-II (Fig. S1C) on the surface of dendritic cells. We observed that the expressions of CD80, CD86, and MHC-I on the surface of dendritic cells treated with JZA02 was higher than that treated with JZA01 or IFNα, and there was no significant difference between the JZA01-treated group and the IFNα-treated group. In conclusion, following treatment with JZA02, colorectal tumor cells and dendritic cells expressed more MHC class I and JZA02 promoted dendritic cell maturation to a greater extent than the JZA01-or IFNα-treated groups.

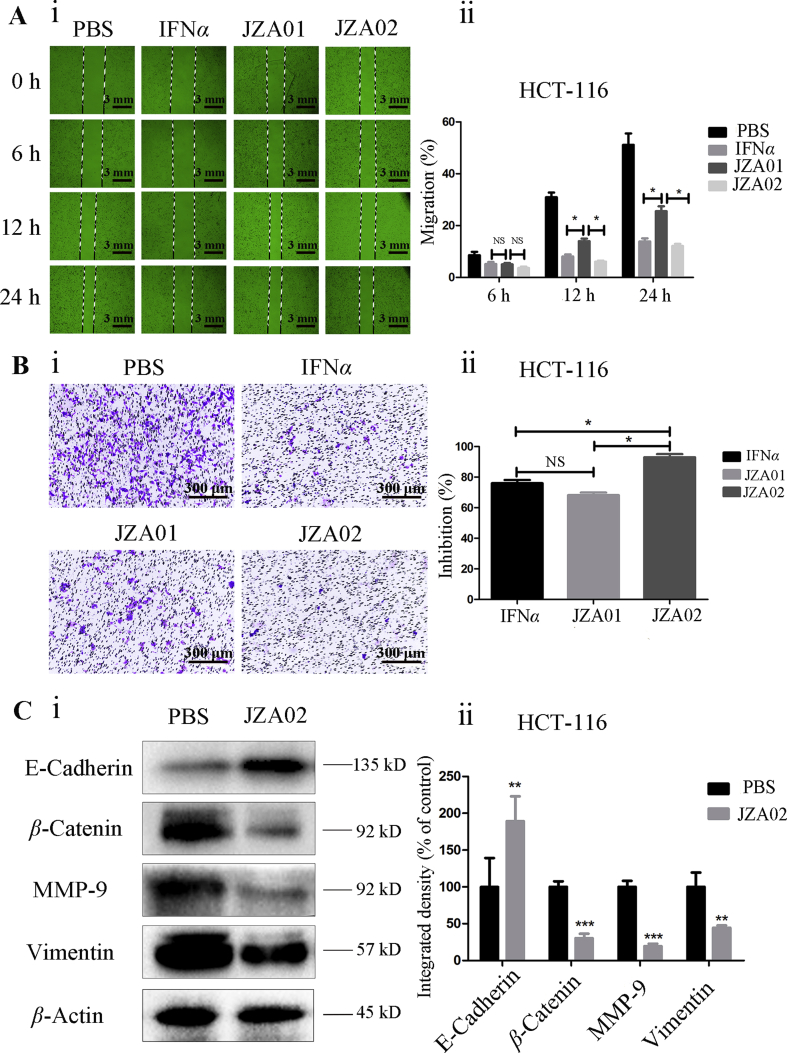

3.5. JZA02 inhibited migration and invasion of colorectal cancer cells

HCT-116 cells were cultured in 6-well plates until adherent, and then a 1 mL tip was used to draw a straight line in the middle of each well before adding 100 nmol/L JZA02, 100 nmol/L JZA01, or 200 nmol/L IFNα. Photographs were taken at 0, 6, 12, and 24 h using an OLYMPUS inverted microscope at 100× magnification. JZA02 exhibited more effective inhibition of migration of HCT-116 cells than JZA01, but it was not more effective than IFNα (Fig. 3A and Fig. S1D). Additionally, in the Transwell invasion assay, the inhibition of HCT-116 cells treated with JZA02 was higher than that treated with JZA01 and IFNα using the same concentrations (Fig. 3B). In conclusion, JZA02 was more effective than JZA01 in inhibiting the invasion and migration of tumor cells HCT-116.

Figure 3.

JZA02 inhibited migration and invasion of HCT-116 cells and regulated the EMT of HCT-116 cells. (A) For the scratch test, HCT-116 cells were incubated in 24-well plates with JZA01, JZA02, or IFNα and photographed at 0, 12, and 24 h. The migration lengths were measured by Image-Pro Plus 6.0 (i) and the data (ii) are presented as the mean ± SD, n = 3; ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001. (B) Photomicrographs (i) and quantitative analysis (ii) of a Transwell invasion assay indicated that JZA02 suppressed the invasion of HCT-116 cells better than IFNα or JZA01. The count of invasive cells treated with different drugs was measured by Image-Pro Plus 6.0. Inhibition (%) = [(control–experiment)/control] × 100. (C) Western blot analysis. (i) Western blot analysis for the EMT index of HCT-116 cells that underwent treatment with PBS and JZA02. (ii) Gray scanning and data statistics of (i) based on the integrated density of β-actin. Data are presented as the mean ± SD, n = 3; ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001.

3.6. JZA02 suppressed tumor growth and influenced the tumor microenvironment in HCT-116-bearing nude mice

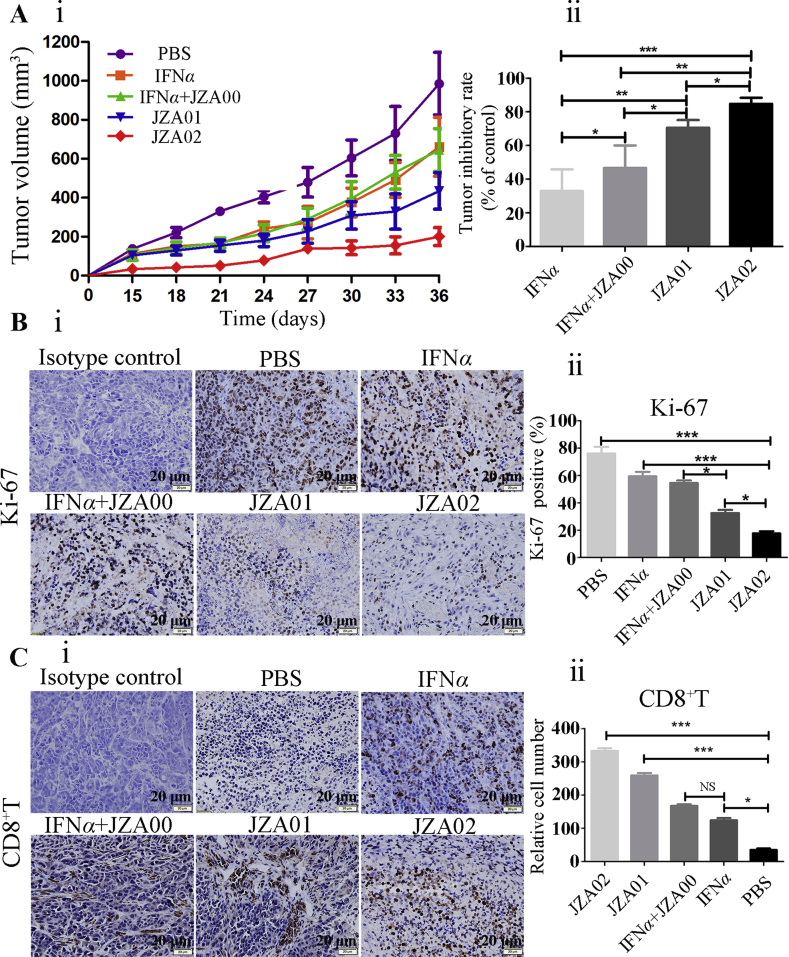

To evaluate the efficacy of JZA02 in inhibiting colorectal tumor growth compared with JZA01 and IFNα, 1 × 107 HCT-116 cells were inoculated subcutaneously in the armpit of BALB/c nude mice, and the tumor-bearing mice were treated twice a week with JZA02 (1 mg/kg), JZA01 (1 mg/kg), IFNα (0.2 mg/kg) or IFNα combined with JZA00 (0.2 mg/kg+1 mg/kg). At the same time, 5 × 106 hPBMCs from healthy donors were injected into the tumor-bearing mice once a week, and the tumor volume was measured during the treatment. At the end of the treatment, the growth of colorectal tumors was most inhibited in the JZA02-treated group (89.45%). JZA01 and IFNα reduced tumor burdens by 78% and 48% at a dose of 1 mg/kg, respectively, and JZA00 (1 mg/kg) combined with IFNα (0.2 mg/kg) reduced tumor burdens by 60%. Growth inhibition of the different treatment groups varied, but the maximum growth inhibition occurred in the JZA02 group (Fig. 4A). The detailed graph of tumors and the data for mice and tumor weights are shown in Supporting Information Fig. S2A–S2C. In addition, IHC shows that there was a significant decrease in the expression of cell proliferation marker Ki-67 in JZA02-treated tumors compared with other groups (Fig. 4B), and the infiltration of CD8+ T cells into tumors in mice treated with JZA02 was greater than in mice treated with JZA01, IFNα, or IFNα+JZA00 (Fig. 4C). Thus, the treatment influenced the TME.

Figure 4.

JZA02 had superior antitumor efficacy in HCT-116-bearing nude mice and influenced the tumor microenvironment. (A) (i) Female nude mice 4–6 weeks of age (n = 5/group) were injected in the left armpit with 5 × 106 HCT-116 cells and 1 × 107 unstimulated hPBMCs and then were treated with JZA01 (1 mg/kg), JZA02 (1 mg/kg), IFNα (0.2 mg/kg), or JZA00+IFNα (1 mg/kg+0.2 mg/kg) twice a week, and tumor volumes were monitored for 36 days. (ii) Tumor inhibition of different groups. The data for tumor volumes are given as the mean ± SD (n = 5). (B) (i) Expression of Ki-67 in paraffin sections of xenografted tumor identified with an anti-Ki-67 antibody (brown staining). After 36 days of treatment, tumors were harvested for detected. (ii) The tumor cells that expressed Ki-67 were counted with Image-Pro-Plus. Ki-67 positive (%)=(cells that expressed Ki-67/total cells) × 100. (C) (i) The infiltration of CD8+ T cells was identified with an anti-CD8 antibody (brown staining). (ii) Semiquantitative and statistical analysis of the infiltration of CD8+ T cells. The relative number of CD8+ T cells was calculated with Image-Pro-Plus. All pictures were photographed by an inverted OLYMPUS microscope at 400× magnification.

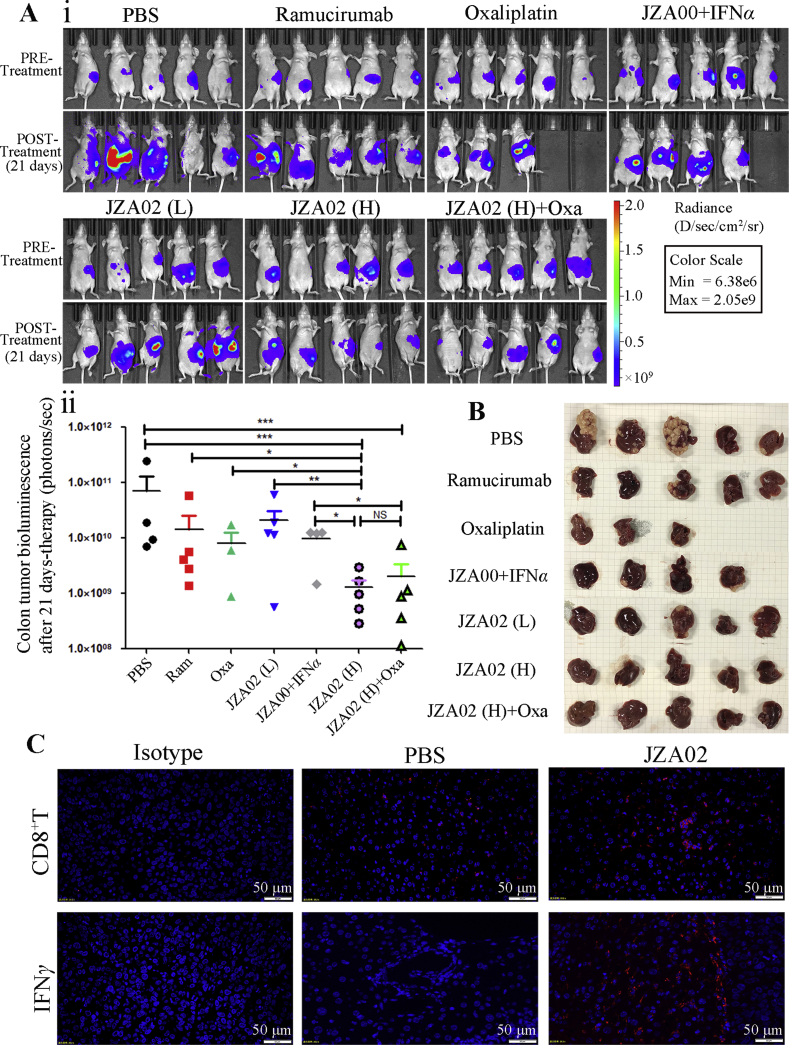

3.7. JZA02 treatment attenuated colon cancer liver metastasis in a nude mouse model

Metastasis remains a major problem in CRC. To determine if JZA02 had anti-metastasis efficacy, a colon cancer liver metastasis model was established in nude mice. The liver is the most common site for CRC metastasis, and intrasplenic injections recapitulate the process of liver metastasis. For this metastasis model, we generated stable HCT-116 clones that expressed firefly luciferase (HCT-116-Luc) constitutively, and obtained a highly metastatic tumor variant by three subsequent transplantations of liver metastatic clones, which was named variant HCT-116-Luc-LM3.

For the splenic injection metastasis model, 5 × 106 HCT-116-Luc-LM3 cells were injected into the spleen of nude mice, and these mice were kept in a SPF environment. A week following surgery, bioluminescence signals were obvious in the mice (Fig. 5A). Then, these mice were assigned randomly to groups (5 mice/group) to receive various treatments. After 21 days of treatment, bioluminescent imaging was used to evaluate the growth and metastasis of the HCT-116-Luc-LM3 cells to the liver. The bioluminescent signal in the JZA02 high dose group and the JZA02+oxaliplatin group was lower and, therefore, the growth and metastasis of CRC cells to the liver reduced in these two groups compared with that treated with ramucirumab, oxaliplatin, or JZA00+IFNα (Fig. 5A). In addition, the high dose JZA02 treatment was more effective in reducing the growth and metastasis of cancer cells than the low dose JZA02 treatment. At the end of treatment, every mouse was dissected and the liver removed to observe the metastatic nodes. The result is consistent with the bioluminescent images (Fig. 5B). In conclusion, JZA02 inhibited the growth of colorectal tumor and reduced metastasis to the liver of the colon cancer in vivo.

Figure 5.

JZA01 had superior ability to prevent metastasis in nude mice model for liver metastasis of colorectal cancer by influencing the tumor microenvironment. (A) (i) Mice (4–6 weeks of age) were anesthetized using 3.8% (w/v) chloral hydrate (10 μL/g), and an incision was made in the middle of the abdomen. 5 × 106 HCT-116-Luc-LM3 cells stably expressing firefly luciferase were injected into their spleens. After 1 week, an IVIS Imaging System was used to assess the success of engraftment and mice were divided into different treatment groups. After 21 days of treatment, an IVIS Imaging System was used to determine the extent of tumor growth (the POST-Treatment group). (ii) Tumor growth was quantified by bioluminescent imaging. (B) Livers from every group were harvested and photographed. (C) The infiltration of CD8+ T cells and expression of IFNγ in livers of mice was identified with an anti-CD8 antibody (red staining) and an anti-IFNγ antibody (red fluorescence). All pictures were photographed by an inverted OLYMPUS microscope at 400× magnification.

3.8. JZA02 treatment influenced the tumor microenvironment in the liver and regulated the metastasis index of tumor cells in the liver

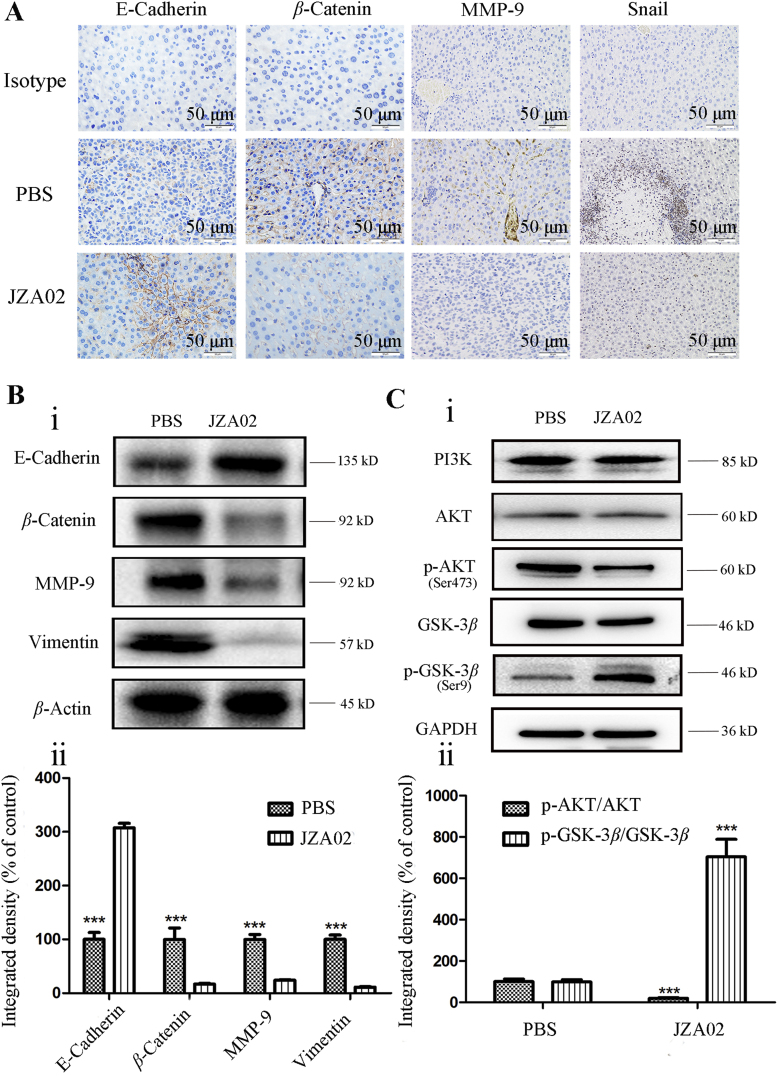

In this study, we demonstrate that JZA02 treatment inhibited tumor growth and attenuated metastasis of colon cancer to the liver. To determine if JZA02 altered the TME to reduce metastasis to the liver, immunofluorescence was used to determine the infiltration of CD8+ T cells and the expression of IFNγ in the mouse liver. Greater infiltration of CD8+ T cells were found in the JZA02-treated group compared with PBS-treated animals (Fig. 5C). In addition, we used immunohistochemistry and Western blot assay to determine the expression of metastasis-associated proteins in the liver of mice treated with high dose JZA02 compared with the PBS-treated group (Fig. 6A and B, and Fig. S2D). JZA02 increased the expression of E-cadherin and decreased the expression of MMP-9, vimentin, snail, and β-catenin. In summary, JZA02 may have activated the immune system to regulate the expression of the proteins that were associated with metastasis to inhibit metastasis of colorectal cancer to the liver.

Figure 6.

Changes in protein expression associated with the effect of JZA02 treatment on metastasis. (A) IHC that was used to detect the index associated with metastasis in the liver of mice that underwent different treatments. (B) (i) Western blot that was used to detect the index associated with metastasis in the liver of mice undergoing different treatments. (ii) Gray scanning and data statistics of (i) based on the integrated density of β-actin. Data are presented as the mean ± SD, n = 3; ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001. (C) (i) Western blot analysis for p-AKT/AKT and p-GSK3β/GSK3β in HCT-116-Luc-LM3 cells with treatments of PBS and JZA02. (ii) Gray scanning and data statistics of (i) based on the integrated density of β-actin. Data are presented as the mean ± SD, n = 3; ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001.

3.9. JZA02 inhibited the activation of the PI3K–AKT–GSK3β–snail signal pathway and regulated the metastasis-associated index in colorectal cancer cells

In the process of cancer development and metastasis, E-cadherin, MMP-9, vimentin, and β-catenin play significant roles in cell migration, invasion, and cell-matrix adhesion. Therefore, the effect of JZA02 on the expression of E-cadherin, MMP-9, vimentin, and β-catenin in HCT-116-Luc-LM3 and SW620 cells was determined by Western blot. JZA02 increased the expression of E-cadherin, but reduced the expression of MMP-9, vimentin, and β-catenin in HCT-116 and HCT-116-Luc-LM3 cells (Figure 3, Figure 6B). We also found that JZA02 inhibited the expression of snail, an epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT)-related transcription factor. So, these results suggest that JZA02 might target transcriptional and posttranslational modifications of snail to regulate the expression of proteins that were associated with cell invasion and migration. Studies of signal transduction pathways have demonstrated that PI3K/AKT and GSK-3β were involved with the regulation of snail expression at the level of transcription. In our study, JZA02 inhibited the expression of p-AKT and promoted the expression of p-GSK-3β, but the total amount of AKT and GSK-3β was constant, and the expression of snail was inhibited (Fig. 6C and Fig. S2E). GN25 (a novel inhibitor of snail–P53 binding) and JZA02 can suppress the migration and invasion of HCT-116 cells as showed in Fig. S2E. In summary, it appeared that JZA02 inhibited the activation of the PI3K–AKT–GSK3β signal pathway to downregulate and to suppress snail expression and, therefore, prevented tumor metastasis by interfering with EMT.

4. Discussion

Liver metastasis of colorectal cancer is an urgent medical problem clinically34, 35, 36, 37. Some reports have shown that the metastasis of tumors was associated with the tumor microenvironment19, 20, 21, 22. So we speculated that therapies that regulate the TME effectively may influence the metastasis of tumors.

IFNα exhibited efficacy in cancer therapy by inhibiting tumor development and metastasis, in part, because of its regulation of the TME24,25,38, 39, 40, 41, 42. But major limitations for IFNα therapy are systemic toxicity and a short in vivo half-life43, although many strategies have been used to address this problem. For example, IFNα has been coupled with PEG, albumin, or the antibody Fc fragment, but these approaches did not eliminate serious systemic toxicity44, 45, 46. In contrast, Ab–IFNα fusion protein may be a solution for this problem. Anti-CD20-IFNα had both improved pharmacokinetics and tumor-targeting in the absence of non-specific toxicity47,48. Based on these findings, in our previous study, we fused IFNα with the anti-VEGFR2 antibody that yielded a novel fused antibody, JZA01, which had significant anti-cancer activity in vitro and in vivo32.

It has been reported that IFNs, which has a higher affinity for IFNAR, may be a better anticancer therapeutic; IFNαmut has shown excellent anti-tumor properties in a previous study33. Therefore, we mutated the IFNα to increase its affinity for IFNAR1 and fused IFNαmunt with JZA00 to produce another fusion antibody, JZA02. At first, we verified that JZA02 exhibited higher affinity for IFNAR1 than did JZA01. Then, we found that JZA02 was more effective than JZA01 in inhibiting colorectal cell proliferation, in inducing colorectal cell apoptosis in vitro, and in promoting dendritic cell maturation and activity in vivo. JZA02 also promoted colorectal cancer cells HCT-116 and SW620 to increase their expression of MHC-Ι. In addition, in HCT-116 tumor-bearing nude mice, JZA02 exhibited superior anti-tumor efficacy compared with JZA01 and IFNα. Subsequent IHC and IF analyses showed that JZA02 was more effective than IFNα and JZA01 in stimulating the release of cytokines and the infiltration of CD8+ T cells in the tumor, which suggested it had improved efficacy to regulate the TME in vivo in agreement with what we observed in vitro. Taken together, JZA02 that contained a mutant IFNα with a higher affinity for IFNAR1 showed improved anti-tumor properties.

Once we had demonstrated that JZA02 regulated the TME effectively, we speculated that JZA02 with its functions of both anti-angiogenesis and regulation of TME might reduce liver metastasis of colorectal cancer. Indeed, we found this to be the case in the mouse model of colorectal cancer liver metastasis, where JZA02 inhibited the activation of the PI3K–AKT–GSK3β signal pathway that led to downregulation of the expression of snail, an EMT-related transcription factor. The downregulation of snail interfered with EMT through the regulation of the expression of E-cadherin, MMP-9, vimentin, and β-catenin. Thus, JZA02 exhibited significant efficacy in preventing metastasis. In future studies, we will attempt to identify the specific genes that determine the metastasis of colorectal cancer cells, which may be highly expressed in HCT-116-Luc-LM3.

Overall, this study has some important implications for the field of antitumor immune therapy. JZA02, in which JZA00 was fused with IFNαmut through G4S linker, possessed higher affinity for IFNAR1 compared with JZA01 that contained wild-type IFNα. By regulating the TME, JZA02 exhibited significant anti-metastasis activity. Our hope is that it may provide an approach to address the promotion of the migration and invasion of cancer cells that a treatment with only a VEGF/VEGFR2 inhibitor entails. Collectively, this study provides a new approach for the treatment of colorectal cancer, especially when the cancer has spread to the patient's liver.

5. Conclusions

Our study illuminated that anti-VEGFR2-IFNαmut (JZA02) enhanced the infiltration of CD8+ T cells in the TME and promoted the maturation of dendritic cells. At the same time, it also inhibited the activation of the PI3K–AKT–GSK3β signal pathway. It possessed anti-tumor and anti-metastasis properties. This design, which fused the anti-VEGFR2 antibody with IFN or its mutant, broadens the use of therapy for cancer based on anti-angiogenesis. This can provide us with some insights for the design of promising cancer immunotherapies in the future.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Sherie L. Morisson, Professor Emeritus, University of California Los Angeles (USA), for help with editing this paper. This work was supported by grants from “Double First-Class” University Project (CPU2018PZQ12 and CPU2018GY14, China); National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant 81993223); National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant 81773755); Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20161459, China); Postgraduate Research & Practice Innovation Program of Jiangsu Province (SJCX19_0162, China); and the National Students’ Platform for Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program (201810316010Y, China).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chinese Pharmaceutical Association and Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences.

Supporting data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsb.2020.09.008.

Author contributions

Conception and design: Juan Zhang; development of methodology: Pengzhao Shang, Rui Gao, Yijia Zhu, Xiaorui Zhang, Yang Wang, and Hui Peng; acquisition of data: Pengzhao Shang, Rui Gao, Xiaorui Zhang, and Yang Wang; analysis and interpretation of data: Pengzhao Shang, and Rui Gao; writing, review, and/or revision of the manuscript: Pengzhao Shang, Rui Gao, Juan Zhang, and Min Wang; study supervision: Juan Zhang.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Bray F., Ferlay J., Soerjomataram I., Siegel R.L., Torre L.A., Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tan E.K., Ooi L.L. Colorectal cancer liver metastases—understanding the differences in the management of synchronous and metachronous disease. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2010;39:719–733. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Woo I.S., Jung Y.H. Metronomic chemotherapy in metastatic colorectal cancer. Canc Lett. 2017;400:319–324. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2017.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hong D.S., Morris V.K., El Osta B., Sorokin A.V., Janku F., Fu S. Phase IB study of vemurafenib in combination with irinotecan and cetuximab in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer with BRAFV600E mutation. Canc Discov. 2016;6:1352–1365. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-16-0050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Casak S.J., Fashoyin-Aje I., Lemery S.J., Zhang L., Jin R., Li H. FDA approval summary: ramucirumab for gastric cancer. Clin Canc Res. 2015;21:3372–3376. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-0600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Poole R.M., Vaidya A. Ramucirumab: first global approval. Drugs. 2014;74:1047–1058. doi: 10.1007/s40265-014-0244-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shibuya M. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and its receptor (VEGFR) signaling in angiogenesis: a crucial target for anti- and pro-angiogenic therapies. Genes Cancer. 2011;2:1097–1105. doi: 10.1177/1947601911423031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jiang Z., Wang L., Liu X., Chen C., Wang B., Wang W. Discovery of a highly selective VEGFR2 kinase inhibitor CHMFL-VEGFR2-002 as a novel anti-angiogenesis agent. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2020;10:488–497. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2019.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saharinen P., Eklund L., Pulkki K., Bono P., Alitalo K. VEGF and angiopoietin signaling in tumor angiogenesis and metastasis. Trends Mol Med. 2011;17:347–362. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2011.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mountzios G., Pentheroudakis G., Carmeliet P. Bevacizumab and micrometastases: revisiting the preclinical and clinical rollercoaster. Pharmacol Ther. 2014;141:117–124. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2013.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pàez-Ribes M., Allen E., Hudock J., Takeda T., Okuyama H., Viñals F. Antiangiogenic therapy elicits malignant progression of tumors to increased local invasion and distant metastasis. Canc Cell. 2009;15:220–231. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.01.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loges S., Mazzone M., Hohensinner P., Carmeliet P. Silencing or fueling metastasis with VEGF inhibitors: antiangiogenesis revisited. Canc Cell. 2009;15:167–170. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ebos J.M., Lee C.R., Cruz-Munoz W., Bjarnason G.A., Christensen J.G., Kerbel R.S. Accelerated metastasis after short-term treatment with a potent inhibitor of tumor angiogenesis. Canc Cell. 2009;15:232–239. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lucio-Eterovic A.K., Piao Y., de Groot J.F. Mediators of glioblastoma resistance and invasion during antivascular endothelial growth factor therapy. Clin Canc Res. 2009;15:4589–4599. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sennino B., McDonald D.M. Controlling escape from angiogenesis inhibitors. Nat Rev Canc. 2012;12:699–709. doi: 10.1038/nrc3366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhao C., Zeng C., Ye S., Dai X., He Q., Yang B. Yes-associated protein (YAP) and transcriptional coactivator with a PDZ-binding motif (TAZ): a nexus between hypoxia and cancer. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2020;10:947–960. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2019.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Joyce J.A., Fearon D.T. T cell exclusion, immune privilege, and the tumor microenvironment. Science. 2015;348:74–80. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa6204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu X., Hu W., Lu L., Zhao Y., Zhou Y., Xiao Z. Repurposing vitamin D for treatment of human malignancies via targeting tumor microenvironment. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2019;9:203–219. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2018.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Szczerba B.M., Castro-Giner F., Vetter M., Krol I., Gkountela S., Landin J. Neutrophils escort circulating tumour cells to enable cell cycle progression. Nature. 2019;566:553–557. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-0915-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Albrengues J., Shields M.A., Ng D., Park C.G., Ambrico A., Poindexter M.E. Neutrophil extracellular traps produced during inflammation awaken dormant cancer cells in mice. Science. 2018;361 doi: 10.1126/science.aao4227. eaao4227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Linde N., Casanova-Acebes M., Sosa M.S., Mortha A., Rahman A., Farias E. Macrophages orchestrate breast cancer early dissemination and metastasis. Nat Commun. 2018;9:21. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02481-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vasiliadou I., Holen I. The role of macrophages in bone metastasis. J Bone Oncol. 2013;2:158–166. doi: 10.1016/j.jbo.2013.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Conlon K.C., Miljkovic M.D., Waldmann T.A. Cytokines in the treatment of cancer. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2019;39:6–21. doi: 10.1089/jir.2018.0019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fuertes M.B., Kacha A.K., Kline J., Woo S.R., Kranz D.M., Murphy K.M. Host type I IFN signals are required for antitumor CD8+ T cell responses through CD8α+ dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2011;208:2005–2016. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rizza P., Moretti F., Capone I., Belardelli F. Role of type I interferon in inducing a protective immune response: perspectives for clinical applications. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2015;26:195–201. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2014.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ye Y., Ricard L., Siblany L., Stocker N., De Vassoigne F., Brissot E. Arsenic trioxide induces regulatory functions of plasmacytoid dendritic cells through interferon-α inhibition. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2020;10:1061–1072. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2020.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.De Palma M., Mazzieri R., Politi L.S., Pucci F., Zonari E., Sitia G. Tumor-targeted interferon-α delivery by Tie2-expressing monocytes inhibits tumor growth and metastasis. Canc Cell. 2008;14:299–311. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Summers J., Cohen M.H., Keegan P., Pazdur R. FDA drug approval summary: bevacizumab plus interferon for advanced renal cell carcinoma. Oncol. 2010;15:104–111. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2009-0250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith N.R., Baker D., Farren M., Pommier A., Swann R., Wang X. Tumor stromal architecture can define the intrinsic tumor response to VEGF-targeted therapy. Clin Canc Res. 2013;19:6943–6956. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-1637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grignol V.P., Olencki T., Relekar K., Taylor C., Kibler A., Kefauver C. A phase 2 trial of bevacizumab and high-dose interferon alpha 2B in metastatic melanoma. J Immunother. 2011;34:509–515. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e31821dcefd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rini B.I., Halabi S., Rosenberg J.E., Stadler W.M., Vaena D.A., Ou S.S. Bevacizumab plus interferon alfa compared with interferon alfa monotherapy in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma: CALGB 90206. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5422–5428. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.9847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li Z., Zhu Y., Li C., Trinh R., Ren X., Sun F. Anti-VEGFR2-interferon-α2 regulates the tumor microenvironment and exhibits potent antitumor efficacy against colorectal cancer. OncoImmunology. 2017;6 doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2017.1290038. e1290038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yoo E.M., Trinh K.R., Tran D., Vasuthasawat A., Zhang J., Hoang B. Anti-CD138-targeted interferon is a potent therapeutic against multiple myeloma. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2015;35:281–291. doi: 10.1089/jir.2014.0125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bacac M., Stamenkovic I. Metastatic cancer cell. Annu Rev Pathol. 2008;3:221–247. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathmechdis.3.121806.151523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tanami H., Tsuda H., Okabe S., Iwai T., Sugihara K., Imoto I. Involvement of cyclin D3 in liver metastasis of colorectal cancer, revealed by genome-wide copy-number analysis. Lab Invest. 2005;85:1118–1129. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ishizaki T., Katsumata K., Tsuchida A., Wada T., Mori Y., Hisada M. Etodolac, a selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor, inhibits liver metastasis of colorectal cancer cells via the suppression of MMP-9 activity. Int J Mol Med. 2006;17:357–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chang H.J., Lee M.R., Hong S.H., Yoo B.C., Shin Y.K., Jeong J.Y. Identification of mitochondrial FoF1-ATP synthase involved in liver metastasis of colorectal cancer. Canc Sci. 2007;98:1184–1191. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2007.00527.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Borden E.C., Sen G.C., Uze G., Silverman R.H., Ransohoff R.M., Foster G.R. Interferons at age 50: past, current and future impact on biomedicine. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6:975–990. doi: 10.1038/nrd2422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Buchbinder E.I., McDermott D.F. Interferon, interleukin-2, and other cytokines. Hematol Oncol Clin N Am. 2014;28:571–583. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2014.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Farkas A., Kemény L. Interferon-α in the generation of monocyte-derived dendritic cells: recent advances and implications for dermatology. Br J Dermatol. 2011;165:247–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Paolini R., Bernardini G., Molfetta R., Santoni A. NK cells and interferons. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2015;26:113–120. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2014.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Parmar S., Platanias L.C. Interferons: mechanisms of action and clinical applications. Curr Opin Oncol. 2003;15:431–439. doi: 10.1097/00001622-200311000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gresser I. Antitumour effects of interferons: past, present and future. Br J Haematol. 1991;79 Suppl 1:1–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1991.tb08108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jabbour E., Kantarjian H., Cortes J., Thomas D., Garcia-Manero G., Ferrajoli A. PEG-IFN-alpha-2b therapy in BCR-ABL-negative myeloproliferative disorders: final result of a phase 2 study. Cancer. 2007;110:2012–2018. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Flisiak R., Flisiak I. Albinterferon-alpha 2b: a new treatment option for hepatitis C. Expet Opin Biol Ther. 2010;10:1509–1515. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2010.521494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jones T.D., Hanlon M., Smith B.J., Heise C.T., Nayee P.D., Sanders D.A. The development of a modified human IFN-alpha2b linked to the Fc portion of human IgG1 as a novel potential therapeutic for the treatment of hepatitis C virus infection. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2004;24:560–572. doi: 10.1089/jir.2004.24.560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xuan C., Steward K.K., Timmerman J.M., Morrison S.L. Targeted delivery of interferon-alpha via fusion to anti-CD20 results in potent antitumor activity against B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2010;115:2864–2871. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-10-250555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Trinh K.R., Vasuthasawat A., Steward K.K., Yamada R.E., Timmerman J.M., Morrison S.L. Anti-CD20-interferon-β fusion protein therapy of murine B-cell lymphomas. J Immunother. 2013;36:305–318. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3182993eb9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.