Abstract

Background

Evidence about the impact of systematic nursing surveillance on risk of acute deterioration of patients with COVID-19 and the effects of care complexity factors on inpatient outcomes is scarce. The aim of this study was to determine the association between acute deterioration risk, care complexity factors and unfavourable outcomes in hospitalised patients with COVID-19.

Methods

A multicentre cohort study was conducted from 1 to 31 March 2020 at seven hospitals in Catalonia. All adult patients with COVID-19 admitted to hospitals and with a complete minimum data set were recruited retrospectively. Patients were classified based on the presence or absence of a composite unfavourable outcome (in-hospital mortality and adverse events). The main measures included risk of acute deterioration (as measured using the VIDA early warning system) and care complexity factors. All data were obtained blinded from electronic health records. Multivariate logistic analysis was performed to identify the VIDA score and complexity factors associated with unfavourable outcomes.

Results

Out of a total of 1176 patients with COVID-19, 506 (43%) experienced an unfavourable outcome during hospitalisation. The frequency of unfavourable outcomes rose with increasing risk of acute deterioration as measured by the VIDA score. Risk factors independently associated with unfavourable outcomes were chronic underlying disease (OR: 1.90, 95% CI 1.32 to 2.72; p<0.001), mental status impairment (OR: 2.31, 95% CI 1.45 to 23.66; p<0.001), length of hospital stay (OR: 1.16, 95% CI 1.11 to 1.21; p<0.001) and high risk of acute deterioration (OR: 4.32, 95% CI 2.83 to 6.60; p<0.001). High-tech hospital admission was a protective factor against unfavourable outcomes (OR: 0.57, 95% CI 0.36 to 0.89; p=0.01).

Conclusion

The systematic nursing surveillance of the status and evolution of COVID-19 inpatients, including the careful monitoring of acute deterioration risk and care complexity factors, may help reduce deleterious health outcomes in COVID-19 inpatients.

Keywords: health informatics, health & safety, quality in health care, infectious diseases, respiratory infections

Strengths and limitations of this study.

We performed a multicentre cohort study with a large sample of patients with COVID-19.

This novel research assessed the impact of the risk of acute deterioration and broader contributors to care complexity on outcomes of patients with COVID-19.

We did not evaluate other clinical measures such as the age-adjusted Charlson Comorbidity Index or patient laboratory values.

The results of this study only apply to adult wards and intermediate care inpatients.

The risk of acute deterioration was measured using VIDA, an early warning system not yet fully implemented in all hospital wards.

Introduction

Along with climate change and financial crises, pandemics are a major global risk in the 21st century. A 2019 report stated that, in the last decade, the WHO had tracked 1483 epidemic events, including severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), Middle East respiratory syndrome, Ebola and other epidemic-prone diseases, considered harbingers of a new era of high-impact, potentially fast-spreading outbreaks.1

The potential threat became real in December 2019, when a severe acute respiratory infection caused by the new coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 first began to spread in Wuhan (China).2 3 The WHO described the ‘Wuhan pneumonia’ as an outbreak of potential danger on 31 December, and as an outbreak of global concern on 31 January. This coronavirus disease (named COVID-19) was declared a global pandemic in February 2020.

Patients with COVID-19 frequently require hospital admission as they may rapidly develop severe potentially life-threatening complications, such as acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), sepsis, major thromboembolic events or cardiac injury, requiring intensive care.3–5 Recent studies have found overall in-hospital mortality rates for COVID-19 inpatients ranging from 15% to 28%.3 6–8 Therefore, early recognition of patient deterioration and escalation of treatment to reduce the risk of progression to critical complications is a significant issue that may impact patient and organisational outcomes. Screening for acute deterioration implies nursing surveillance, data collection, interpretation and recognition of changes in patients’ status, prioritisation of patients’ problems and decision-making on the interventions needed in order to curb the cascade towards adverse events (AEs) and death.9

According to the WHO, ‘patients hospitalized with COVID-19 require regular monitoring of vital signs and, where possible, utilization of early warning scores that facilitate early recognition and escalation of treatment of the deteriorating patient.’10 Early warning systems have become an important component of managing inpatient care, and are a clinical decision-making support stratification tool used to prevent poor health outcomes.11–13 Previous studies suggested the need for adaptation of these systems to each context.14 According to these recommendations, several evidence-based algorithms have been developed and used to identify and act on initial or impending acute deterioration among hospitalised patients in a timely fashion. In the context of this study, a nursing surveillance improvement programme named VIDA (the Catalan acronym for Surveillance and Identification of Acute Deterioration) was first implemented in 2013 and, through a multidisciplinary approach, has evolved into an early warning score system that is used on a daily basis to assist clinical decision-making.

It has been reported that patients hospitalised with COVID-19 have a substantial rate of chronic conditions that may affect the complexity of medical and nursing care provision and patient health outcomes.15 Nevertheless, care complexity individual factors (CCIF) are related to multiple comorbidities and mental-cognitive and psychosocial patient features, which in turn are also associated with increased healthcare needs during hospitalisation and with selected health outcomes.16–18

Only a few studies in COVID-19 inpatients have explored the use of acute deterioration risk stratification11 19 and to date, none has assessed CCIF as predictors of poor health outcomes. The aim of this study was to determine the association between the risk of acute deterioration (as measured using the VIDA early warning system), CCIF and unfavourable outcomes in patients hospitalised with COVID-19.

Methods

Setting and study design

A retrospective cohort study was carried out at seven public hospitals in Catalonia, Spain: three tertiary metropolitan facilities, three urban university centres and one community hospital. All patients with a medical diagnosis of COVID-19 infection admitted to a ward or intermediate unit for COVID-19 or other causes from 1 to 31 March 2020 with a completed hospital minimum data set report were recruited retrospectively and followed up during hospitalisation until discharge or death. Patients directly admitted and discharged from intensive care units (ICU) were excluded because the VIDA early warning system is not used in the ICU. Patients who remained hospitalised after the recruitment end date were also excluded as the hospital minimum data set was not available.

We defined the primary endpoint as a composite of unfavourable outcomes including in-hospital mortality or AEs, not present on admission and occurring thereafter during hospitalisation.

Patient and public involvement

Patients were not involved in the design, conduct or reporting of this study.

Data collection

Information regarding the demographic and clinical characteristics, continuity of care (discharged to another facility), high-tech hospital (referral centre that provides tertiary care for either open-heart surgery or major organ transplants or both), length of hospital stay (LOS) and patient severity and mortality risk was collected from the hospital minimum data set and the clinical data warehouse of the Catalan Institute of Health. Patient severity and risk of mortality were based on the All Patient Refined Diagnosis-Related Group (APR-DRG), which categorises both measures from low (level 1) to extreme (level 4). Severity and mortality risk were dichotomised in this study into low risk (levels 1–2) and high risk (levels 3–4).20 All variables were collected during hospitalisation.

The VIDA score (acute deterioration risk stratification) automatically classifies patients into five groups according to patient progress data: no risk (level 0), low risk (level 1), moderate risk (level 2), high risk (impending complication if not stabilised) (level 3), manifested complication initial status (level 4). Levels 2–4 create an alert in the electronic health records and require action in response to clinical recommendations. These recommendations are standardised for each context and involve intensifying the surveillance of the patients’ status and notifying the medical team. The health team (nurse and specialist) are responsible for the final clinical decision-making. For the purposes of this study, the VIDA score was classified as mild (levels 1–2) or high (levels 3–4) risk. Patients were classified according to the highest VIDA score obtained during their hospitalisation. Patient progress data were extracted from anonymised electronic health records whenever they were e-charted, and included: respiratory rate (breaths per minute), oxygen saturation (%), temperature (°C), mental status (level of awareness: 1=aware and orientated, >1=disturbed mental status, including disorientation, acute confusion, and so on), pulse (cardiac rate, beats per minute) and systolic and diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) (online supplemental file 1).

bmjopen-2020-041726supp001.pdf (32.8KB, pdf)

CCIFs were classified into five domains: (1) mental-cognitive, (2) psychoemotional, (3) sociocultural, (4) developmental, and (5) comorbidity/complications, as described in previous studies.16 18 Each CCIF domain is structured into factors and specifications. Patients were considered to fall within any CCIF domains if they presented at least one factor or specification during their hospitalisation. These CCIF factors and specifications were obtained from the nursing assessment e-charts as structured data based on the Architecture, Terminology, Interface, Knowledge terminology20 (online supplemental file 2).

bmjopen-2020-041726supp002.pdf (28.9KB, pdf)

Outcome measures

The main endpoint was a composite of unfavourable outcomes including in-hospital mortality and AEs during hospitalisation. The in-hospital mortality counted the number of patients with COVID-19 dying while in a ward. The AEs included ICU transfer, hospital-acquired infections (HAI) and potentially avoidable critical complications (ACC) during hospitalisation. ICU transfer was defined as the number of patient episodes with effective bed change from a general ward to an intensive care area. HAI included the number of episodes of ward patients who developed catheter-related bloodstream infection, urinary catheter-related infection, aspiration pneumonia and/or sepsis. ACC accounted for the number of episodes of ward patients who experienced a cardiac arrest, shock, thromboembolic event, acute respiratory failure, ARDS, myocardial injury, liver injury and/or kidney failure, not present on admission.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analysis of data using percentage frequencies, median and IQR was performed to determine demographic and clinical characteristics and patient outcomes. For categorical variables, a comparative analysis for detecting significant differences between groups was carried out using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test when one or more cells had an expected frequency of 5 or less. For continuous variables, the Student’s t-test or Mann-Whitney U test was used depending on the results of the Kolmogorov-Smirnov normality test. A logistic regression model of all clinical factors potentially associated with unfavourable outcome measures (AEs and in-hospital mortality) was performed including the VIDA score, clinically relevant CCIF and other potential confounders: sex, hospital level and LOS. All potential explanatory variables included in the multivariate analysis were subjected to a correlation matrix for analysis of collinearity. The discriminatory power was evaluated by the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC). The results of the multivariate analysis were reported as OR and 95% CIs. We also performed an adjusted analysis to compare unfavourable outcomes in patients admitted to wards with and without the VIDA system. Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS software package V.25.0 (SPSS). P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

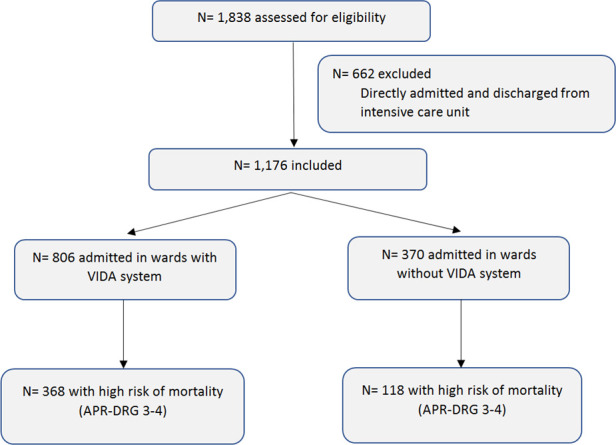

During the study period, 1838 patients were hospitalised with COVID-19, of which 1176 met the inclusion criteria (figure 1). The frequency of unfavourable outcomes was 42.8% (506 patients). The in-hospital mortality rate was 19.6% (232 patients), and almost 41% (481 patients) experienced an AE while in a ward (2.7% transferred to ICU; 2.5% HAI; 40% ACC). Acute respiratory failure, ARDS, acute kidney failure, urinary catheter-related infection, sepsis and thrombotic events were the most frequent AEs.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of patient selection process. APR-DRG, All Patient Refined Diagnosis-Related Group; VIDA, Surveillance and Identification of Acute Deterioration.

Patient characteristics

The baseline characteristics of patients with an unfavourable and favourable outcome are compared in table 1. Hospitalised patients with COVID-19 who had an unfavourable outcome were more often male, older and had one or more underlying chronic conditions (75.5%), mostly arterial hypertension or congestive heart failure, and diabetes or chronic kidney disease. Furthermore, they had a longer LOS and a high risk of severity or mortality (APR-DRG 3–4). Conversely, patients admitted to high-tech hospitals presented a lower frequency of unfavourable outcomes.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics, VIDA score and care complexity factors of admitted COVID-19 inpatients with unfavourable and favourable outcomes

| Characteristics | Study population n=1176 |

Unfavourable outcome* n=506 (42.8%) |

Favourable outcome n=670 (57.1%) |

P value |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Demographic characteristics | ||||

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 66.5 (51–77) | 74 (60–80) | 61 (49–74) | <0.001 |

| Male sex | 667 (56.7) | 192 (37.9) | 317 (47.3) | 0.001 |

| Clinical characteristics | ||||

| LOS, median (IQR) | 6 (4–8) | 7 (4–10) | 5 (4–7) | <0.001 |

| Continuity of care (discharged to another facility) | 165 (14) | 58 (11.5) | 107 (16) | 0.02 |

| Severity (APR-DRG 3–4) | 503 (42.8) | 450 (88.9) | 53 (7.9) | <0.001 |

| Mortality risk (APR-DRG 3–4) | 486 (41.3) | 449 (88.7) | 37 (5.5) | <0.001 |

| High-tech hospital | 969 (82.4) | 389 (76.9) | 580 (86.6) | <0.001 |

| Underlying disease | 745 (63.4) | 382 (75.5) | 363 (54.4) | <0.001 |

| Arterial hypertension or chronic heart failure | 469 (39.9) | 234 (46.2) | 235 (35.1) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes or chronic kidney disease | 298 (25.3) | 165 (32.6) | 133 (19.9) | <0.001 |

| Chronic respiratory disease | 171 (14.5) | 95 (18.8) | 76 (11.3) | <0.001 |

| Neurodegenerative disease | 63 (5.3) | 33 (6.5) | 39 (4.5) | 0.15 |

| Chronic liver disease | 54 (4.6) | 30 (5.9) | 24 (3.6) | 0.07 |

| Cancer | 50 (4.3) | 31 (6.5) | 19 (2.8) | 0.008 |

| Immunosuppression | 49 (4.2) | 23 (4.5) | 26 (3.9) | 0.66 |

| VIDA score† | ||||

| Low risk (0) | 104 (12.9) | 27 (7.1) | 77 (18) | <0.001 |

| Moderate risk (1–2) | 505 (62.7) | 194 (51.2) | 311 (72.8) | <0.001 |

| High risk (3–4) | 197 (16.7) | 158 (41.7) | 39 (9.1) | <0.001 |

| Care complexity individual factors (CCIF) | ||||

| Comorbidity/complications | 1176 (100) | 506 (9.1) | 670 (100) | – |

| Transmissible infection | 1176 (100) | 506 (100) | 670 (100) | – |

| Haemodynamic instability | 910 (77.4) | 396 (78.3) | 514 (76.7) | 0.57 |

| Chronic disease | 745 (63.4) | 382 (75.5) | 363 (54.4) | <0.001 |

| Uncontrolled pain | 194 (16.5) | 82 (16.2) | 112 (16.7) | 0.87 |

| Extreme weight | 168 (14.3) | 82 (16.2) | 86 (12.8) | 0.11 |

| Position impairment | 72 (6.1) | 52 (10.3) | 20 (3.0) | <0.001 |

| Urinary or faecal incontinence | 58 (4.9) | 31 (6.1) | 27 (4.0) | 0.10 |

| Immunosuppression | 49 (4.1) | |||

| Anatomical and functional disorders | 41 (3.5) | 30 (5.9) | 11 (1.6) | <0.001 |

| Communication disorders | 18 (1.5) | 13 (2.6) | 5 (0.7) | 0.01 |

| High risk of haemorrhage | 2 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.1) | 0.68 |

| Vascular fragility | 6 (0.5) | 4 (0.8) | 2 (0.3) | 0.41 |

| Involuntary movements | 3 (0.3) | 3 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0.08 |

| Dehydration | 3 (0.3) | 1 (0.2) | 2 (0.3) | 0.60 |

| Oedema | 0 (0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | – |

| Developmental | 397 (33.8) | 244 (48.2) | 153 (22.8) | <0.001 |

| Old age (≥75 years) | 397 (33.8) | 244 (48.2) | 153 (22.8) | <0.001 |

| Psychoemotional | 218 (18.5) | 86 (17.0) | 132 (19.7) | 0.13 |

| Fear/anxiety | 173 (14.7) | 70 (13.8) | 103 (15.4) | 0.51 |

| Impaired adaptation | 54 (4.6) | 17 (3.4) | 37 (5.5) | 0.09 |

| Aggressive behaviour | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0.43 |

| Mental-cognitive | 240 (20.4) | 184 (36.4) | 56 (8.4) | <0.001 |

| Mental status impairments | 238 (20.2) | 183 (36.2) | 55 (8.2) | <0.001 |

| Agitation | 5 (0.4) | 4 (0.8) | 1 (0.1) | 0.17 |

| Impaired cognitive functions | 4 (0.3) | 3 (0.6) | 1 (0.1) | 0.32 |

| Perception of reality disorders | 2 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.3) | 0.51 |

| Sociocultural | 1176 (100) | 506 (100) | 670 (100) | – |

| Lack of caregiver support | 1176 (100) | 506 (100) | 670 (100) | – |

| Belief conflict | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 0.57 |

| Language barriers | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0.43 |

| Social exclusion | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 1 |

| CCIF, median (IQR) | 4 (3–6) | 5 (4–6) | 4 (3–5) | <0.001 |

*Unfavourable outcomes included in-hospital mortality and adverse events during hospitalisation

†VIDA score was analysed according to 806 patients admitted to wards using the VIDA system.

APR-DRG, All Patient Refined Diagnosis-Related Group; ICU, intensive care unit; IQR, interquartile range; LOS, length of hospital stay; VIDA, Surveillance and Identification of Acute Deterioration.

Among the 806 patients in wards where the VIDA early warning system was in use, most patients with unfavourable outcomes experienced a high risk of acute deterioration (41.7% in patients with unfavourable outcomes vs 9.1% in patients with favourable outcomes).

Comorbidity, sociocultural and developmental domains were the most frequent CCIF domains identified in the studied sample. Mental-cognitive and psychoemotional domains were less frequent. Patients with unfavourable outcomes exhibited a higher frequency of chronic disease, position impairment, anatomical and functional disorders, communication disorders, old age (>75 years) and mental status impairment, when compared with patients with favourable outcomes. The median CCIF was also higher in patients with unfavourable outcomes (5 [IQR: 4–6] vs 4 [IQR: 3–5]) (table 1).

Association of outcomes with risk of acute deterioration and care complexity factors

The outcomes of 806 patients with low, mild or high risk of acute deterioration are compared in table 2. The frequency of unfavourable outcomes was almost 38% in patients with mild risk and almost 80% in those at high risk of acute deterioration (p<0.001). Similarly, the frequency of in-hospital mortality and AEs rose with increasing VIDA score and was around 60% and 80%, respectively, in patients with a high risk of acute deterioration (p<0.001). Acute respiratory failure, acute kidney failure and ICU transfer were the most frequent AEs.

Table 2.

Patient outcomes according to risk of acute deterioration (VIDA score) and care complexity factors

| Outcomes |

VIDA score n=806 (68.5) | CCIF n=1176 | ||||

| All | Low risk (0) | Mild risk (1–2) | High risk (3–4) | CCIF<4 | CCIF≥4 | |

| n=1176 | n=104 (12.9) | n=505 (62.7) | n=197 (16.7) | n=327 (27.8) | n=849 (72.2) | |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Unfavourable outcomes | 506 (43.0) | 27 (26.0)** | 194 (38.4)* | 158 (80.2)** | 92 (28.1)** | 414 (48.8)** |

| Deceased | 232 (19.6) | 0 (0.0)** | 46 (9.1)** | 118 (59.9)** | 5 (1.5)** | 227 (26.7)** |

| Adverse event | 481 (40.9) | 27 (26.0)** | 187 (37)* | 153 (77.7)** | 91 (27.8)** | 394 (46.4)** |

| ICU transfer | 32 (2.7) | 0 (0.0)* | 12 (2.4) | 13 (6.6)* | 4 (1.2)* | 28 (3.3)* |

| HAI | 29 (2.5) | 0 (0.0)* | 10 (2) | 12 (6.1)* | 1 (1.5) | 24 (2.8) |

| Catheter-related bloodstream infection | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.1) |

| Hospital acquired urinary tract infection | 19 (1.6) | 0 (0) | 7 (1.4) | 8 (4.1)* | 3 (0.9) | 16 (1.9) |

| Aspiration pneumonia | 3 (0.3) | 0 (0) | 3 (0.6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (0.4) |

| Sepsis | 7 (0.6) | 0 (0) | 10.2 | 3 (1.5)* | 2 (0.6) | 5 (0.6) |

| ACC | 470 (40) | 27 (26.0)** | 181 (35.8)** | 150 (76.1)** | 88 (26.6)** | 383 (45.1)** |

| Cardiac arrest | 5 (0.4) | 1 (1) | 0 (0.0)* | 3 (1.5)* | 0 (0) | 5 (0.6) |

| Shock | 4 (0.3) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (0.5) |

| Thrombotic event | 7 (0.6) | 1 (1) | 1 (0.2) | 2 (1) | 1 (0.3) | 6 (0.7) |

| Acute respiratory failure† | 436 (37) | 27 (26.0)** | 164 (32.5)** | 144 (73.1)** | 84 (25.1)** | 353 (41.6)** |

| Myocardial injury | 5 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 3 (0.6) | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0) | 5 (0.6) |

| Liver injury | 2 (0.2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.2) |

| Renal insufficiency | 83 (7.1) | 1 (1.0)* | 28 (5.5)* | 31 (15.7)** | 6 (1.8)** | 77 (9.1)** |

*P>0.001 and p<0.05; **p≤0.001.

†Includes acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).

ACC, avoidable critical complications; CCIF, care complexity individual factors; HAI, hospital-acquired infections; ICU, intensive care unit; VIDA, Surveillance and Identification of Acute Deterioration.

Among the 1176 patients analysed in this study, those with four or more CCIFs experienced unfavourable outcomes (p<0.05) (table 2).

Table 3 shows an adjusted analysis of health outcomes in 486 patients with a high risk of mortality (APR-DRG 3–4). In-hospital mortality was more frequent in patients admitted to wards where VIDA was not used (52.5% vs 41.3%, p<0.05). Conversely, the frequency of AEs was slightly higher in patients admitted to wards using VIDA (p<0.05).

Table 3.

Adjusted analysis of unfavourable outcomes according to VIDA early warning system in 486 patients with high risk of mortality (APR-DRG 3–4)

| Outcomes | Unadjusted | Adjusted | With VIDA system | Without VIDA system | P value* |

| n=1176 | n=486 (41.2) | n=368 (75.7) | n=118 (24.3) | ||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Unfavourable outcomes | 506 (43) | 449 (92.4) | 345 (93.8) | 104 (88.1) | 0.07 |

| Deceased | 232 (19.6) | 214 (44) | 152 (41.3) | 62 (52.5) | 0.02 |

| Adverse event | 481 (40.9) | 436 (89.7) | 337 (91.6) | 99 (83.9) | 0.02 |

| ICU transfer | 32 (2.7) | 25 (5.1) | 20 (5.4) | 5 (4.2) | 0.41 |

| HAI | 29 (2.5) | 19 (3.9) | 16 (4.3) | 3 (2.5) | 0.28 |

| ACC | 470 (40) | 433 (89.1) | 334 (90.8) | 99 (83.9) | 0.31 |

*All variables were compared using the Fisher’s exact test.

ACC, avoidable critical complications; APR-DRG, All Patient Refined Diagnosis-Related Group; HAI, hospital-acquired infections; ICU, intensive care unit; VIDA, Surveillance and Identification of Acute Deterioration.

Risk factors associated with unfavourable outcomes

The results of the multivariate analysis for risk of acute deterioration (as measured using the VIDA score) and CCIF potentially associated with unfavourable outcomes, in-hospital mortality and AEs are summarised in table 4.

Table 4.

Multivariate analysis of VIDA score and CCIF in 806 adult COVID-19 inpatients associated with unfavourable outcomes, death and AEs

| Characteristics | Unfavourable outcomes† | Deceased‡ | AEs§ |

| n=379/806 (47%) | n=164/806 (20.3%) | n=367/806 (45.5%) | |

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Old age (≥75 years) | 1.48 (0.99 to 2.22) | 3.04 (1.79 to 5.15)** | 1.52 (1.02 to 2.26)* |

| Male sex | 1.21 (0.87 to 1.69) | 1.86 (1.11 to 3.11)* | 1.2 (0.87 to 1.67) |

| LOS | 1.16 (1.11 to 1.21)** | 0.97 (0.93 to 1.01) | 1.17 (1.12 to 1.22)** |

| High-tech hospital | 0.57 (0.36 to 0.89)* | 1.88 (0.94 to 3.78) | 0.61 (0.39 to 0.95)* |

| VIDA score 3–4 | 4.32 (2.83 to 6.60)** | 13.99 (8.44 to 23.18)** | 4.21 (2.79 to 6.36)** |

| Chronic disease | 1.9 (1.32 to 2.72)** | 2.01 (1.03 to 3.90)* | 1.81 (1.26 to 2.59)** |

| Position impairment | 1.19 (0.58 to 2.44) | 1.41 (0.63 to 3.13) | 1.23 (0.62 to 2.46) |

| Communication disorders | 0.97 (0.24 to 3.96) | 0.87 (0.22 to 3.41) | 0.78 (0.21 to 2.95) |

| Mental status impairments | 2.31 (1.45 to 23.66)** | 6.21 (3.67 to 10.50)** | 1.72 (1.09 to 2.69)* |

Multivariate analysis included: high risk of acute deterioration (VIDA score 3–4), clinically relevant care complexity factors (old age, chronic disease, position impairment, communication disorders and mental status impairments) and potential confounders (sex, hospital level and LOS).

*P>0.001 and p<0.05; **p≤0.001.

†AUC 0.81 (95% CI 0.78 to 0.84).

‡AUC 0.91 (95% CI 0.88 to 0.93).

§AUC 0.80 (95% CI 0.77 to 0.83).

AE, adverse event; AUC, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve; CCIF, care complexity individual factors; CI, Confidence interval; LOS, length of hospital stay; OR, Odds ratio; VIDA, Surveillance and Identification of Acute Deterioration.

After adjustment for potential confounders, the analysis showed that a high risk of acute deterioration was an independent factor associated with unfavourable outcomes, in-hospital mortality and AEs in COVID-19 inpatients. Furthermore, chronic disease, mental status impairment and LOS were risk factors associated with unfavourable outcomes. Conversely, high-tech hospital admission was a protective factor against unfavourable outcomes. The AUC was 0.81 (95% CI 0.78 to 0.84).

Chronic disease, mental status impairment, old age and male sex were independent risk factors associated with in-hospital mortality in the studied COVID-19 inpatients (AUC 0.91, 95% CI 0.88 to 0.93). Finally, risk factors independently associated with AEs were chronic disease, mental status impairment, old age and LOS, whereas high-tech hospital admission was a protective factor against AEs (AUC 0.80, 95% CI 0.77 to 0.83). The AUCs of the three outcomes analysed were >0.80, showing a fair discriminatory power.

Discussion

In this study of a large cohort of hospitalised patients with COVID-19, the frequency of in-hospital mortality and AEs was around 60% and 80%, respectively, in patients scored as at high risk of acute deterioration. In-hospital mortality was higher in wards not using the VIDA early warning system. The majority of patients had four or more care complexity factors identified. The risk factors independently associated with unfavourable outcomes included chronic disease, mental status impairment, LOS and a high risk of acute deterioration. High-tech hospital admission was a protective factor against unfavourable outcomes.

Our findings are consistent with previous COVID-19 reports that found a similar frequency of in-hospital mortality and AEs.3 21 In addition, 37% of patients developed respiratory complications (acute respiratory failure or ARDS) during hospitalisation. This value is within the range reported in a previous study (29%–42%).3

The results of this study show that a high risk of acute deterioration is a significant risk factor for unfavourable outcomes, as a composite measure for in-hospital mortality and AEs in COVID-19 inpatients. Although previous studies have stressed that early warning systems are predictors of in-hospital mortality and health outcomes,22 23 only a few have evaluated warning score systems in COVID-19 inpatients.11 19 These latest studies showed a fair discrimination with adverse outcomes, illustrating that evaluating the risk for acute deterioration in the COVID-19 hospital population is a priority for healthcare organisations.19

In-hospital mortality was more frequent in patients admitted to wards where registered nurses (RN) were not using the VIDA early warning system. In this regard, other studies have shown that the use of early warning systems reinforces collaboration among the multidisciplinary team, and promotes the early identification of clinical deterioration.24 Similarly, previous studies have reported lower mortality and fewer AEs when systematic nursing surveillance of patient status and progress is part of the daily routine.9

Chronic conditions and mental status impairments were the CCIFs independently associated with unfavourable outcomes. Previous reports have shown that chronic diseases were more frequent among deceased patients with COVID-1915 and that ageing was a potential risk factor associated with mortality.6 Although our study did not identify age as a risk factor associated with a composite unfavourable outcome, we acknowledge that old age was an independent risk factor associated with mortality and AEs. Furthermore, our findings are also consistent with other studies demonstrating that mental status impairment is associated with hospital-acquired complications,25 including sepsis.4

The majority of patients had four or more CCIFs. Our findings are consistent with other studies that identified a significant rate of chronic conditions in patients with COVID-1915 along with various organisational issues that may impact care complexity and health outcomes.26 Previous studies have demonstrated the association of CCIF and health outcomes,16 with an average of two CCIFs per patient. In our study of COVID-19 inpatients, the average number of CCIFs was 4. These results are probably related to the transmissibility of this condition, which requires droplet and contact precautions; the public health measures of population confinement for pandemic management, which prevent patients’ relatives from visiting them in person, resulting in a lack of family caregiver support during hospitalisation; and the frequency of chronic diseases in the studied sample. The organisational adaptation of hospitals to this pandemic context and the required isolation precautions have been associated with poor outcomes in prior studies.27 28

We also found that LOS was associated with unfavourable outcomes, consistent with previous studies that associated AEs with increased healthcare costs due to longer hospital stays.29 Finally, high-tech hospital admission was a protective factor against unfavourable outcomes. High-tech hospitals usually have better nurse to patient ratios than urban or community facilities. In this sense, several recent studies in the same study setting concluded that on average, hospital ward patients require 5.6 hours of RN care per patient-day, while the average of available RN hours per patient-day is 2.4, and that RN understaffing is a structural issue.26 30 Nevertheless, to the best of our knowledge, no study on nurse staffing and COVID-19 inpatient outcomes has been published. Similarly, clinical leaders and healthcare managers have a key role to play in rapidly adapting organisations to the new reality. Fast and effective decision-making and managerial responses in crisis situations with high levels of uncertainty are essential both immediately and in the short term; however, they should be accompanied by planning and executing mid-term and long-lasting improvements that positively impact patient, professional and organisational outcomes, such as structural RN understaffing.26

The strengths of this study include its multicentre approach, cohort design and large sample size. It is the first study evaluating the association of the risk of acute deterioration, along with care complexity factors, with outcomes of patients with COVID-19. Importantly, we identify the importance of a range of contributors to care complexity, including psychosocial and mental-cognitive factors. In addition, the VIDA early warning system was developed as an evidence-based algorithm using a multidisciplinary approach, based on previous studies that highlighted the importance of adapting surveillance and screening systems to the organisational and cultural context.14

This study is not exempt from limitations. First, the VIDA score and CCIF data were comprehensively collected from the clinical data warehouse of the Catalan Institute of Health and all patients included had a completed nurse chart in the patient electronic health record, but we were still reliant on proper compliance with electronic record keeping and the collection of administrative data. This is acknowledged as a significant limitation since voluntary completion of patient electronic documentation during the initial weeks of the first wave of COVID-19 in our country might have been negatively influenced by the rising hospital burden, the understandable prioritisation of direct patient care, as well as the physical and emotional stress experienced by bedside healthcare professionals. Second, regarding the study selection criteria, patients directly admitted and discharged from the ICU were excluded, since no early warning system was in use in the critical care setting at the outset of the pandemic in our study area. In this sense, the results of this study only apply to adult ward and intermediate care inpatients. Third, it should be noted that of the 1176 patients included, only 806 were hospitalised in wards with a fully implemented VIDA system. Therefore, patients admitted to wards without the VIDA system did not have data available on risk of acute deterioration (VIDA score). This is a significant limitation. The VIDA system was under development in hospitals belonging to the Catalan Institute of Health during the data collection period. Therefore, future studies should corroborate the current results in centres where VIDA has been fully implemented. However, due to the high number of daily admissions, the patients’ unplanned assignment to the different wards (with or without the VIDA system) means that the patients’ clinical characteristics were similar between wards with and without the VIDA system. Fourth, although an unpublished face validity study has demonstrated the effectiveness of the VIDA early warning system, full evaluation of its psychometric properties is still pending. To minimise the potential effect of this limitation, we conducted an adjusted analysis performed with 486 patients with a similar higher risk of mortality (APR-DRG 3–4), comparing those admitted to wards using VIDA with those being treated in units with no VIDA early warning system. The results show that in-hospital mortality was more frequent in patients admitted to wards where VIDA had not yet been implemented. This result should be interpreted with caution because this analysis only included patients with a high risk of mortality and could have been influenced by other variables such as the differences in sample sizes. Finally, we acknowledge as a potential limitation that other clinical measures such as the age-adjusted Charlson Comorbidity Index or patient laboratory values were not assessed. Selected laboratory values such as lactate, ferritin or calciferol have been studied as indicators of COVID-19 prognosis and severity. Combining point-of-care laboratory data with clinical data from nurses’ observations and judgements on patient complexity factors, status and progress would probably result in an improved system for the early detection and prevention of critical complications and other unfavourable outcomes in COVID-19 inpatients.

Conclusion

The risk of acute deterioration and CCIF is associated with outcomes of patients with COVID-19. The rate of unfavourable outcomes rose with increasing risk of acute deterioration as measured using the VIDA score. The risk factors independently associated with poor health outcomes were chronic disease, mental status impairment, LOS and high risk of acute deterioration. High-tech hospital admission was a protective factor against unfavourable outcomes. The systematic nursing surveillance of patients at risk of acute deterioration and the assessment of CCIF may help reduce deleterious health outcomes in adult COVID-19 inpatients.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors had full access to all study data and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: JA, MGS, MEJU. Coordination team: MEJU. Acquisition of data: JA, MTP, MMLJ, EZP, TCN. Analysis and interpretation of data: JA, MGS, EJM. Drafting of the manuscript: JA, MGS, EJM, MEJU. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: MTP, MMLJ, HRF, EZP, TCN, JC. Statistical analysis: JA, MGS. Administrative, technical and material support: MMLJ, HRF. Study supervision: MEJU, JC.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Bellvitge University Hospital (reference 158/20). Informed consent was waived due to the study’s retrospective design. Ethical and data protection protocols related to anonymity and data confidentiality (access to records, data encryption and archiving of information) were complied with throughout the study.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplemental information.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

References

- 1.World Bank, WHO . Global preparedness monitoring board. A world at risk. annual report on global preparedness for health emergencies, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li Q, Guan X, Wu P, et al. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia. N Engl J Med 2020;382:1199–207. 10.1056/NEJMoa2001316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 2020;395:497–506. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li H, Liu L, Zhang D, et al. SARS-CoV-2 and viral sepsis: observations and hypotheses. Lancet 2020;395:1517–20. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30920-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shi S, Qin M, Shen B, et al. Association of cardiac injury with mortality in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Cardiol 2020;5:802 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.0950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet 2020;395:1054–62. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu C, Chen X, Cai Y. Risk factors associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome and death in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA Intern Med 2020. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zheng Z, Peng F, Xu B. Risk factors of critical & mortal COVID-19 cases: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. J Infect 2020;81 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.04.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Juvé-Udina M-E, Fabrellas-Padrés N, Adamuz-Tomás J, et al. Surveillance nursing diagnoses, ongoing assessment and outcomes on in-patients who suffered a cardiorespiratory arrest. Rev Esc Enferm USP 2017;51:e03286. 10.1590/s1980-220x2017004703286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.WHO Clinical management of severe acute respiratory infection when novel coronavirus (nCoV) infection is suspected, 2020. Available: https://www.who.int/publications-detail/clinical-management-of-severe-acute-respiratory-infection-when-novel-coronavirus-(ncov)-infection-is-suspected [Accessed 20 May 2020].

- 11.Hu H, Yao N, Qiu Y. Comparing rapid scoring systems in mortality prediction of critically ill patients with novel coronavirus disease. Acad Emerg Med 2020;27:461–8. 10.1111/acem.13992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liao X, Wang B, Kang Y. Novel coronavirus infection during the 2019-2020 epidemic: preparing intensive care units-the experience in Sichuan Province, China. Intensive Care Med 2020;46:357–60. 10.1007/s00134-020-05954-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O'Brien C, Goldstein BA, Shen Y, et al. Development, implementation, and evaluation of an in-hospital optimized early warning score for patient deterioration. MDM Policy Pract 2020;5:1–10. 10.1177/2381468319899663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McGaughey J, O'Halloran P, Porter S, et al. Early warning systems and rapid response to the deteriorating patient in hospital: a realist evaluation. J Adv Nurs 2017;73:3119–32. 10.1111/jan.13367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen T, Wu D, Chen H, et al. Clinical characteristics of 113 deceased patients with coronavirus disease 2019: retrospective study. BMJ 2020;368:m1091. 10.1136/bmj.m1091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adamuz J, González-Samartino M, Jiménez-Martínez E, et al. Care complexity individual factors associated with Hospital readmission: a retrospective cohort study. J Nurs Scholarsh 2018;50:411–21. 10.1111/jnu.12393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Safford MM The complexity of complex patients. J Gen Intern Med 2015;30:1724–5. 10.1007/s11606-015-3472-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Juvé-Udina ME, Matud C, Farrero S. Intensity of nursing care: workloads or individual complexity? Metas de Enfermería 2010;13:6–14. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singh K, Valley TS, Tang S, et al. Validating a widely implemented deterioration index model among hospitalized COVID-19 patients. medRxiv 2020. 10.1101/2020.04.24.20079012. [Epub ahead of print: 29 Apr 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Juvé-Udina ME What patients' problems do nurses e-chart? longitudinal study to evaluate the usability of an interface terminology. Int J Nurs Stud 2013;50:1698–710. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2013.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mao L, Jin H, Wang M, et al. Neurologic manifestations of hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol 2020;77:683 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.1127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Medic G, Kosaner Kließ M, Atallah L, et al. Evidence-Based clinical decision support systems for the prediction and detection of three disease states in critical care: a systematic literature review. F1000Res 2019;8:1728. 10.12688/f1000research.20498.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim I, Song H, Kim HJ, et al. Use of the National early warning score for predicting in-hospital mortality in older adults admitted to the emergency department. Clin Exp Emerg Med 2020;7:61–6. 10.15441/ceem.19.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ashbeck R, Stellpflug C, Ihrke E. Development of a standardized system to detect and treat early patient deterioration. J Nurs Care Qual 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bail K, Draper B, Berry H, et al. Predicting excess cost for older inpatients with clinical complexity: a retrospective cohort study examining cognition, comorbidities and complications. PLoS One 2018;13:e0193319. 10.1371/journal.pone.0193319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Juvé-Udina M-E, González-Samartino M, López-Jiménez MM, et al. Acuity, nurse staffing and workforce, missed care and patient outcomes: a cluster-unit-level descriptive comparison. J Nurs Manag 2020;28:2216–29. 10.1111/jonm.13040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Purssell E, Gould D, Chudleigh J. Impact of isolation on hospitalised patients who are infectious: systematic review with meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2020;10:e030371. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tran K, Bell C, Stall N, et al. The effect of hospital isolation precautions on patient outcomes and cost of care: a multi-site, retrospective, propensity score-matched cohort study. J Gen Intern Med 2017;32:262–8. 10.1007/s11606-016-3862-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rafter N, Hickey A, Condell S, et al. Adverse events in healthcare: learning from mistakes. QJM 2015;108:273–7. 10.1093/qjmed/hcu145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Juvé-Udina M-E, Adamuz J, López-Jimenez M-M, et al. Predicting patient acuity according to their main problem. J Nurs Manag 2019;27:1845–58. 10.1111/jonm.12885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-041726supp001.pdf (32.8KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-041726supp002.pdf (28.9KB, pdf)