Abstract

Objectives

We aim to assess the impact of temperature and relative humidity on the transmission of COVID-19 across communities after accounting for community-level factors such as demographics, socioeconomic status and human mobility status.

Design

A retrospective cross-sectional regression analysis via the Fama-MacBeth procedure is adopted.

Setting

We use the data for COVID-19 daily symptom-onset cases for 100 Chinese cities and COVID-19 daily confirmed cases for 1005 US counties.

Participants

A total of 69 498 cases in China and 740 843 cases in the USA are used for calculating the effective reproductive numbers.

Primary outcome measures

Regression analysis of the impact of temperature and relative humidity on the effective reproductive number (R value).

Results

Statistically significant negative correlations are found between temperature/relative humidity and the effective reproductive number (R value) in both China and the USA.

Conclusions

Higher temperature and higher relative humidity potentially suppress the transmission of COVID-19. Specifically, an increase in temperature by 1°C is associated with a reduction in the R value of COVID-19 by 0.026 (95% CI (−0.0395 to −0.0125)) in China and by 0.020 (95% CI (−0.0311 to −0.0096)) in the USA; an increase in relative humidity by 1% is associated with a reduction in the R value by 0.0076 (95% CI (−0.0108 to −0.0045)) in China and by 0.0080 (95% CI (−0.0150 to −0.0010)) in the USA. Therefore, the potential impact of temperature/relative humidity on the effective reproductive number alone is not strong enough to stop the pandemic.

Keywords: COVID-19, epidemiology, public health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Cross-sectional observations from 100 Chinese cities and 1005 US counties cover a wide spectrum of meteorological conditions.

Demographics, socioeconomic status, geographical, healthcare and human mobility factors are all included in the regression analysis.

The Fama-MacBeth regression framework allows the identification of associations between temperature/relative humidity and COVID-19 transmissibility for non-stationary short-duration data.

The exact mechanism of the negative association between R and temperature/relative humidity has not been investigated in this study.

The temperature and relative humidity data do not contain extreme conditions.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic, caused by SARS-CoV-2, has infected more than 70 million people with 1 595 187 deaths across 220 countries and territories as of 13 December 2020,1 since its first reported case in Wuhan, China in December 2019.2 3 COVID-19 has had disastrous impacts on global public health, the environment, socioeconomics.4–7 Understanding the factors that affect the transmission of SARS-CoV-2 is crucial for predicting the transmission dynamics of the virus and making appropriate intervention policies. Numerous recent studies have analysed the effects of anthropogenic factors on COVID-19 transmission, such as travel restrictions,8–10 non-pharmacological interventions,11 population flow,12 anti-contagion policies13 and contact patterns.14

Meteorological factors, such as temperature and humidity, have previously been suggested to be associated with the transmissibility of certain infectious diseases. For example, prior studies have shown that the transmission of influenza is seasonal and is affected by humidity,15 16 and that wintertime climate and host behaviour can facilitate the transmission of influenza.17–19 Studies have also shown that the transmission of other human coronaviruses that cause mild respiratory symptoms, such as OC43 (HCoV-OC43) and HCoV-HKU1, is seasonal.20 21 The seasonality of these related viruses has been leveraged in an indirect long-term simulation of the transmission of SARS-CoV-2,22 23 and other studies have demonstrated a correlation between meteorological factors and pandemic spreading.24 In addition, temperature and humidity have been shown to be important natural factors affecting pulmonary diseases,25 which are prevalent in patients with COVID-19.

However, there is no consensus on the impact of meteorological factors on COVID-19 transmissibility. For example, the study by Merow and Urban shows that ultraviolet light is associated with a decreasing trend in COVID-19 case growth rates.26 In contrast, other studies claim no association between COVID-19 transmissibility and temperature and ultraviolet light27 or a positive association between temperature and daily confirmed cases.28 29 Since the COVID-19 outbreak has lasted for less than a year, we do not have multiyear time-series data to estimate a stable serial cointegration between meteorological factors and certain indicators of COVID-19 transmissibility. As large-scale social intervention unfolded shortly after the outbreak in both countries, the periods without non-pharmaceutical intervention were quite short. Thus, estimation of the influences of meteorological factors on COVID-19 transmissibility is challenging.

The goal of this paper is to accurately quantify such influences, where the meteorological factors include temperature and humidity, and the COVID-19 transmissibility is measured by the effective reproductive number (R values). Our analysis is based on COVID-19 data from both China and the USA. With several months of observations, the R values typically will have a trend, as will temperature and humidity. In this paper, we consider a strategy of ‘trading-space-for-time’ by using Fama-MacBeth regression with Newey-West adjustment for SEs, which is widely used in finance.30–32 Specifically, we first estimate the cross-sectional association between temperature/relative humidity and R values across 100 cities in China from 19 January to 15 February (nationwide lockdown started from 24 January) and 1005 counties in the USA from 15 March to 25 April (nationwide lockdown started from 7 April) and then adjust for the time-series autocorrelation of these estimates. Demographics, socioeconomic status, geographical, healthcare and human mobility status factors are also included in our modelling process as control variables. Our framework enables analysis during the early stage of an infectious disease outbreak and thus has considerable potential for informing policy-makers to consider social interventions in a timely fashion.

Materials and methods

Data

Records of 69 498 patients with COVID-19 with symptom-onset days up to 10 February 2020 from 325 cities are extracted from the Chinese National Notifiable Disease Reporting System. Each patient’s records include the area code of his/her current residence, the area code of the reporting institution, the date of symptom onset and the date of confirmation. With such symptom-onset data, we are able to estimate the precise R values for different Chinese cities. For US data, daily confirmed cases for 1005 counties with a more than 20 000 population size are collected from the COVID-19 database of the Johns Hopkins University Center for Systems Science and Engineering (which is publicly available at https://github.com/CSSEGISandData/COVID-19/). We extract the data from 15 March to 25 April for the 1005 counties, which results in a total of 740 843 confirmed cases. Due to the unavailability of onset date information in the US data, we estimate R values from the daily confirmed cases for US counties, which may be less precise than the estimation for the Chinese cities.

We also collect 4711 cases from Chinese epidemiological surveys published online by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention of 11 provinces and municipalities, including Beijing, Shanghai, Jilin, Sichuan, Hebei, Henan, Hunan, Guizhou, Chongqing, Hainan and Tianjin. By analysing the records of each patient’s contact history, we match close contacts and select 105 pairs of clear virus carriers and infections, which are used to estimate the serial intervals of COVID-19.

Temperature and relative humidity data are obtained from 699 meteorological stations in China (from http://data.cma.cn/). Other factors, including population density, GDP per capita, the fraction of the population aged 65 and above, and the number of doctors for each city in 2018, are obtained online (https://data.cnki.net). The indices indicating the number of migrants from Wuhan to other cities over the period of 7 January to 10 February and the Baidu Mobility Index are also obtained online (https://qianxi.baidu.com/). Panel A of online supplemental table 1 in online supplemental material 1 provides the summary statistics of the variables for analysing the data from China with their pairwise correlations shown in online supplemental table 2.

bmjopen-2020-043863supp001.pdf (33.4KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-043863supp013.pdf (372KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-043863supp002.pdf (35.3KB, pdf)

For the USA, temperature and relative humidity data are collected from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/). Population data and the fraction of residents over 65 years of age for each county are obtained from the American Community Survey (https://www.census.gov/). GDP and personal income in 2018 for each county are obtained online (https://www.bea.gov/). Data describing mobility changes, including the fraction of maximum moving distance over normal time and home-stay minutes for each county, are obtained online (https://github.com/descarteslabs/DL-COVID-19 and https://www.safegraph.com/). The Gini index, the fraction of the population below the poverty level, the fraction of residents who are not in the labour force (under 16 years old), the fraction of households with a total income greater than US$200 000, and the fraction of the population with food stamp/SNAP benefits are obtained from the American Community Survey. The number of ICU beds for each county is obtained online (https://www.kaggle.com/jaimeblasco/icu-beds-by-county-in-the-us/data). Panel B of online supplemental table 1 in online supplemental material 1 provides the summary statistics of the variables for analysing the US data with their pairwise correlations shown in online supplemental table 3.

bmjopen-2020-043863supp003.pdf (36KB, pdf)

Patient and public involvement

In this study, in order to protect the patient privacy, no identifiable protected health information is extracted from the Chinese National Notifiable Disease Reporting System. The Chinese epidemiological surveys data have personal information removed before publication. Patient and/or public are not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Construction of effective reproductive numbers

We use the effective reproductive number, or the R value, to quantify the transmission of COVID-19 in different cities and counties. The calculation of the R value consists of two steps. First, we estimate the serial interval, which is the time between successive cases in a transmission chain of COVID-19 using 105 pairs of virus carriers and infections. We fit these 105 samples of serial intervals with a Weibull distribution using maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) (implemented with the Python package ‘Scipy’ and R package ‘MASS’ (Python V.3.7.4, ‘Scipy’ V.1.3.1 and R V.3.6.2, ‘MASS’ V.7.3_51.4)), as shown in online supplemental figure 1. The results of the two implementations are consistent with each other. The mean and SD of the serial intervals are 7.4 and 5.2 days, respectively.

bmjopen-2020-043863supp012.pdf (100.2KB, pdf)

Note that cities with a small number of confirmed cases typically have a highly wiggly R value curve due to inaccurate R value estimation. Therefore, we select cities with more than 40 cases in China, 100 in total. We then calculate the R value for each of the 100 Chinese cities from the date of the first case to 10 February through a time-dependent method based on MLE (online supplemental material 1 pp. 4–5).33 For estimation of R values in US counties, the settings of serial intervals are set to the same as China, that is, with a 7.4-day mean and 5.2-day SD. We use the same methods of estimating the R values of all 1005 US counties from the date when the first confirmed case occurred in the county to 25 April 2020.

Study period

We aim to study the influences of various factors on the R value under the outdoor environment because if people stay at home for most of their time under the restrictions of the isolation policy, weather conditions are unlikely to influence virus transmission. We thus perform separate analyses before and after the large-scale stay-at-home quarantine policies for both China (24 January) and the USA (7 April). The first-level response to major public health emergencies in many major Chinese cities and provinces, including Beijing and Shanghai, was announced on 24 January. Moreover, the numbers of cases in most cities before 18 January are too small to accurately estimate the R value. Therefore, we take the daily R values from 19 January to 23 January for each city as the before-lockdown period. Although Wuhan City imposed a travel restriction at 10:00 on 23 January, a large number of people still left Wuhan before 10:00 on that day, so our sample still includes 23 January for Wuhan. We take 24 January to 10 February as the period after lockdown for China. As reported by The New York Times, most states announced state-wide stay-at-home orders from 7 April for the USA.34 Moreover, the number of cases in most counties before 15 March is too small to accurately estimate the R value, so we take 15 March to 6 April for each county as the before-lockdown period and 7 April to 25 April as the after-lockdown period.

Statistical analysis

We use 6-day average temperature and relative humidity values up to and including the day when the R value is measured. Our strategy is inspired by the 5-day incubation period estimated from Johns Hopkins University35 plus a 1-day onset. In the data of this work, the series of the 6-day average temperature and relative humidity and the daily R values are mostly non-stationary. We find a declining trend of R values for nearly all Chinese cities and the US counties during our study periods, which could be due to the nature of the disease and people’s raised awareness and increased self-protection measures even before the lockdown (online supplemental table 4). Panel A and panel B in the online supplemental materials show the panel Handri LM unit root test36 results for the China and US data. In this case, direct time-series regression cannot be applied due to the so-called spurious regression37 problem, which states the fact that a regression may provide misleading statistical evidence of a linear relationship between non-stationary time-series variables. We thus adopt the Fama-MacBeth methodology38 with Newey-West adjustment, which consists of a series of cross-sectional regressions and has been proven effective in various disciplines, including finance and economics. The details are described as follows.

bmjopen-2020-043863supp004.pdf (28.2KB, pdf)

Fama-MacBeth regression with the Newey-West adjustment

Fama-MacBeth regression is a two-step procedure (online supplemental material 1 pp. 2–3). In the first step, it runs a cross-sectional regression at each point in time; the second step estimates the coefficient as the average of the cross-sectional regression estimates. Since these estimates might have autocorrelations, we adjust the error of the average with a Newey-West approach. Mathematically, our method proceeds as follows.

Step 1: Let T be the length of the time period and M be the number of control variables. For each timestamp t, we run a cross-sectional regression:

Step 2: Estimate the average of the regression coefficient estimates obtained from the first step:

We use the Newey-West approach39 to adjust for the time-series autocorrelation and heteroscedasticity in calculating the SEs in the second step. Specifically, the Newey-West estimators can be expressed as

where , where e represents residuals and is the lag (online supplemental material 1 pp. 2–3).

The Fama-MacBeth regression with Newey-West adjustment has two advantages: (1) It avoids the spurious regression problem for non-stationary series, as the first-step estimates, , have much milder autocorrelations than the autocorrelations (time trends) within the observations. Such autocorrelations can be adjusted by the Newey-West procedure. (2) Only cross-sectional coefficient estimates in the first step are used to estimate the coefficients, but not their SEs; hence, any heteroscedasticity and residual-dependent issues in the first step will not influence the final results because the heteroscedasticity and residual dependency (including the one caused by spatial correlation) does not alter the unbiasedness of the coefficient in the ordinary least squares estimation. Online supplemental table 5 shows the detailed coefficients of temperature and relative humidity in the first step of the Fama-MacBeth regression.

bmjopen-2020-043863supp005.pdf (37.1KB, pdf)

Note that the Fama-MacBeth regression with Newey-West adjustment is commonly used in estimating parameters for finance and economic models that are valid in the presence of cross-sectional correlation and time-series autocorrelation.30–32 To the best of our knowledge, our study is a novel application of this method in emergent public health and epidemiological problems.

In our implementation, on each day of the study period, we perform a cross-sectional regression of the daily R values of various cities or counties based on their 6-day average temperature and relative humidity values, as well as several categories of control variables, including the following:

Demographics. The population density and the fraction of people aged 65 and older for both China and the USA.

Socioeconomic statuses. The GDP per capita for Chinese cities. For the US counties, the Gini index and the first principal component analysis factor derived from several factors including GDP per capita, personal income, the fraction of the population below the poverty level, the fraction of the population not in the labour force (16 years or over), the fraction of the population with a total household income more than US$200 000 and the fraction of the population with food stamp/SNAP benefits.

Geographical variables. Latitudes and longitudes.

Healthcare. The number of doctors in Chinese cities and the number of ICU beds per capita for US counties.

Human mobility status. For Chinese cities, the number of people who migrated from Wuhan in the 14 days prior to the R measurement and the drop rate of the Baidu Mobility Index compared with the same day in the first week of January 2020.22 For US counties, the fraction of maximum moving distance over the median of normal time (weekdays from 17 February to 7 March) and home-stay minutes are used as mobility proxies. All human mobility controls are averaged over a 6-day period in the regression.

All analyses are conducted in Stata V.16.0.

Results

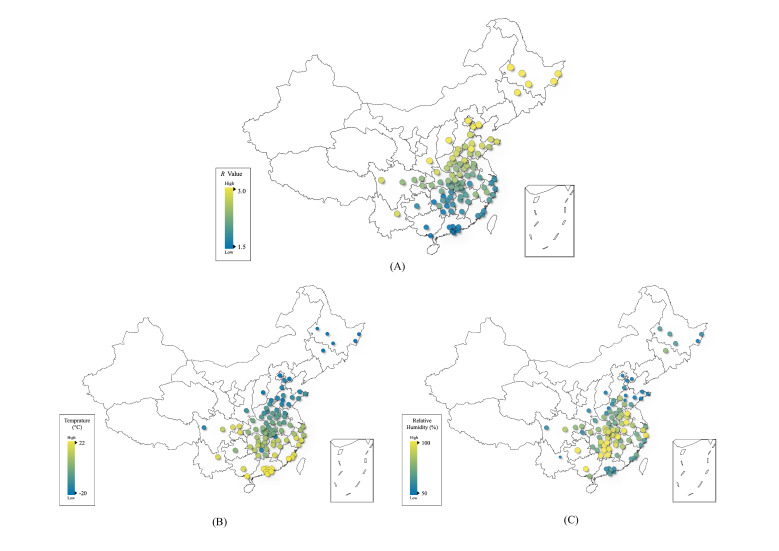

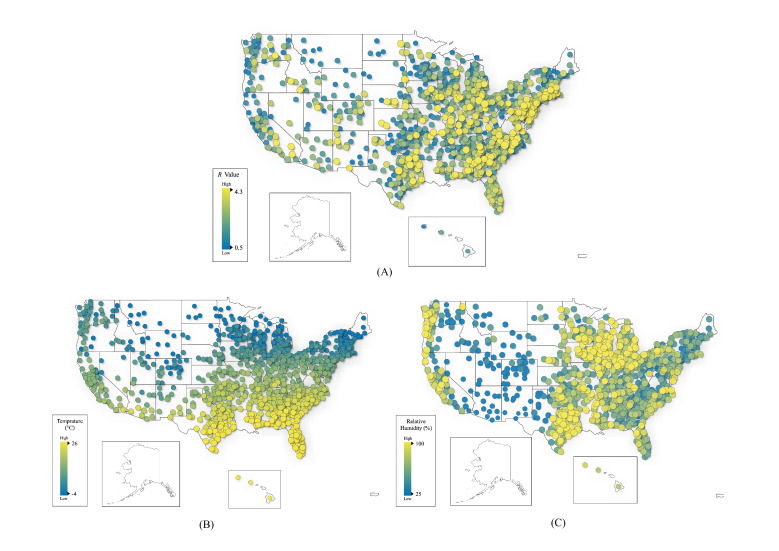

COVID-19 has spread widely in both China and the USA. The transmissibility and meteorological conditions in the cities/counties of these two countries vary greatly (see figures 1 and 2). We analyse the relationship between COVID-19 transmissibility and temperature/relative humidity, controlling for various demographics, socioeconomic statuses, geographical, healthcare and human mobility status factors and correcting for cross-sectional correlations. Overall, we find robust negative correlations between COVID-19 transmissibility before the large-scale public health interventions (lockdown) in China and the USA and temperature and relative humidity. Moreover, temperature has a consistent influence on the effective reproductive number, R values, for both Chinese cities and US counties; relative humidity also has consistent effects across the two countries. Both of them continue to have a negative influence even after the public health intervention, but with smaller magnitudes since an increasing number of people stay at home and hence are exposed less to the outdoor weather. More details are presented in the next section.

Figure 1.

City-level visualisation of COVID-19 transmission (A), temperature (B) and relative humidity (C). Average R values from 19 to 23 January 2020 for 100 Chinese cities are used in subplot (A). The average temperature and relative humidity for the same period are plotted in (B) and (C).

Figure 2.

County-level visualisation of COVID-19 transmission (A), temperature (B) and relative humidity (C) in the USA. Average R values from 15 March to 16 April 2020 for 1005 US counties are used in subplot (A). The average temperature and relative humidity for the same period are plotted in (B) and (C).

Temperature, relative humidity, and effective reproductive numbers

For both China and the USA, we conduct a series of cross-sectional regressions (the Fama-MacBeth approach38) of the daily effective reproductive numbers (R values), which measure COVID-19 transmissibility, on the 6-day average temperature and relative humidity up to and including the day when the R value is measured, considering the transmission during presymptomatic periods35 and other control factors for the before-lockdown period, the after-lockdown period and the overall period. Figure 1 shows the average R values from 19 to 23 January (before lockdown) for different Chinese cities geographically, and figure 2 shows the average R values from 15 March to 6 April (before the majority of states declared a stay-at-home order) for different US counties.

Overall, the results for Chinese cities (table 1) demonstrate that the 6-day average temperature and relative humidity have a significant relationship with R values, with p values smaller than or approximately 0.01 for all three specified time periods. The analysis of US counties (table 2) shows that 6-day average temperature and relative humidity have statistically significant correlations with R values, with p values lower than 0.05 before 7 April, the time when most states declared state-wide stay-at-home orders.34

Table 1.

Fama-MacBeth regression for Chinese cities

| Overall | Before lockdown (24 Jan) | After lockdown (24 Jan) | |

| R2 | 0.3013 | 0.1895 | 0.3323 |

| Temperature | |||

| coef | −0.0220 | −0.0260 | −0.0209 |

| 95% CI | (−0.0356 to –0.0085) | (−0.0395 to –0.0125) | (−0.0378 to –0.0041) |

| SE | 0.0065 | 0.0049 | 0.0080 |

| t-stat | −3.38 | −5.35 | −2.62 |

| p value | 0.003 | 0.006 | 0.018 |

| Relative humidity | |||

| coef | −0.0059 | −0.0076 | −0.0054 |

| 95% CI | (−0.0098 to –0.0019) | (−0.0108 to –0.0045) | (−0.0104 to –0.0004) |

| SE | 0.0019 | 0.0011 | 0.0024 |

| t-stat | −3.08 | −6.70 | −2.29 |

| p value | 0.005 | 0.003 | 0.035 |

| Population density | |||

| coef | 0.0259 | 0.1188 | 0.0001 |

| 95% CI | (−0.0292 to 0.0810) | (0.0573 to 0.1803) | (−0.0359 to 0.0362) |

| SE | 0.0266 | 0.0222 | 0.0171 |

| t-stat | 0.98 | 5.36 | 0.01 |

| p value | 0.340 | 0.006 | 0.993 |

| Percentage over 65 | |||

| coef | 0.1255 | 0.3230 | 0.0707 |

| 95% CI | (−1.7524 to 2.0034) | (−1.1797 to 1.8256) | (−2.3231 to 2.4644) |

| SE | 0.9055 | 0.5412 | 1.1346 |

| t-stat | 0.14 | 0.60 | 0.06 |

| p value | 0.891 | 0.583 | 0.951 |

| GDP per capita | |||

| coef | 0.0045 | −0.0145 | 0.0098 |

| 95% CI | (−0.0157 to 0.0248) | (−0.0249 to –0.0040) | (−0.0105 to 0.0301) |

| SE | 0.0098 | 0.0038 | 0.0096 |

| t-stat | 0.46 | −3.85 | 1.02 |

| p value | 0.647 | 0.018 | 0.322 |

| No of doctors | |||

| coef | −0.0058 | −0.0109 | −0.0043 |

| 95% CI | (−0.0090 to –0.0025) | (−0.0163 to –0.0056) | (−0.0064 to –0.0022) |

| SE | 0.0015 | 0.0019 | 0.0010 |

| t-stat | −3.71 | −5.69 | −4.41 |

| p value | 0.001 | 0.005 | 0.0004 |

| Drop of BMI | |||

| coef | 0.3051 | −0.4093 | 0.5036 |

| 95% CI | (−0.3352 to 0.9454) | (−0.6830 to –0.1356) | (−0.1133 to 1.1205) |

| SE | 0.3087 | 0.0986 | 0.2924 |

| t-stat | 0.99 | −4.15 | 1.72 |

| p value | 0.334 | 0.014 | 0.103 |

| Inflow population from Wuhan | |||

| coef | −0.0052 | −0.0006 | −0.0065 |

| 95% CI | (−0.0106 to 0.0002) | (−0.0010 to –0.0001) | (−0.0127 to –0.0003) |

| SE | 0.0026 | 0.0002 | 0.0029 |

| t-stat | −2.00 | −3.58 | −2.21 |

| p value | 0.058 | 0.023 | 0.041 |

| Latitude | |||

| coef | 0.0046 | 0.0096 | 0.0032 |

| 95% CI | (−0.0145 to 0.0236) | (−0.0133 to 0.0325) | (−0.0211 to 0.0274) |

| SE | 0.0092 | 0.0083 | 0.0115 |

| t-stat | 0.50 | 1.16 | 0.28 |

| p value | 0.625 | 0.311 | 0.786 |

| Longitude | |||

| coef | −0.0110 | −0.0270 | −0.0065 |

| 95% CI | (−0.0199 to –0.0021) | (−0.0528 to –0.0013) | (−0.0137 to 0.0007) |

| SE | 0.0043 | 0.0093 | 0.0034 |

| t-stat | −2.56 | −2.92 | −1.91 |

| p value | 0.018 | 0.043 | 0.074 |

| const | |||

| coef | 1.0929 | 2.1174 | 0.8084 |

| 95% CI | (0.5078 to 1.6781) | (1.5699 to 2.6649) | (0.5334 to 1.0833) |

| SE | 0.2821 | 0.1972 | 0.1303 |

| t-stat | 3.87 | 10.74 | 6.20 |

| p value | 0.001 | 0.0004 | 0 |

Daily R values from 19 January to 10 February and averaged temperature and relative humidity over 6 days up to and including the day when R value is measured, are used in the regression for 100 Chinese cities with more than 40 cases. The regression is estimated by the Fama-MacBeth approach.

BMI, Baidu Mobility Index.

Table 2.

Fama-MacBeth regression for the US counties

| Overall | Before lockdown (7 Apr) | After lockdown (7 Apr) | |

| R2 | 0.1155 | 0.1344 | 0.0925 |

| Temperature | |||

| coef | −0.0165 | −0.0204 | −0.0118 |

| 95% CI | (−0.0257 to –0.0073) | (−0.0311 to –0.0096) | (−0.0279 to 0.0043) |

| SE | 0.0045 | 0.0052 | 0.0077 |

| t-stat | −3.62 | −3.93 | −1.54 |

| p value | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.141 |

| Relative humidity | |||

| coef | −0.0049 | −0.0080 | −0.0013 |

| 95% CI | (−0.0103 to 0.0005) | (−0.0150 to –0.0010) | (−0.0027 to 0.0001) |

| SE | 0.0027 | 0.0034 | 0.0007 |

| t-stat | −1.84 | −2.36 | −1.90 |

| p value | 0.073 | 0.028 | 0.073 |

| Population density | |||

| coef | 4.39E−6 | 7.00E−6 | 1.23E−6 |

| 95% CI | (−0.00001 to 0.00002) | (−0.00003 to 0.00004) | (−9.84E−7 to 3.45E−6) |

| SE | 8.44E−6 | 0.00002 | 1.05E−6 |

| t-stat | 0.52 | 0.44 | 1.17 |

| p value | 0.606 | 0.666 | 0.258 |

| Percentage over 65 | |||

| coef | −0.9243 | −1.1084 | −0.7014 |

| 95% CI | (−1.3510 to –0.4976) | (−1.8119 to –0.4050) | (−1.0696 to –0.3332) |

| SE | 0.2113 | 0.3392 | 0.1752 |

| t-stat | −4.37 | −3.27 | −4.00 |

| p value | 0.0001 | 0.004 | 0.001 |

| Gini | |||

| coef | −1.8428 | −1.9255 | −1.7426 |

| 95% CI | (−3.5058 to –0.1797) | (−4.4539 to 0.6028) | (−2.4697 to –1.0154) |

| SE | 0.8235 | 1.2191 | 0.3461 |

| t-stat | −2.24 | −1.58 | −5.03 |

| p value | 0.031 | 0.129 | 0.0001 |

| Socioeconomic factor | |||

| coef | 0.0916 | 0.1406 | 0.0324 |

| 95% CI | (0.0338 to 0.1495) | (0.0886 to 0.1925) | (−0.0108 to 0.0756) |

| SE | 0.0287 | 0.0250 | 0.0206 |

| t-stat | 3.20 | 5.61 | 1.58 |

| p value | 0.003 | 0.00001 | 0.133 |

| No of ICU beds per capita | |||

| coef | −0.0097 | −0.0086 | −0.0110 |

| 95% CI | (−0.0233 to 0.0039) | (−0.0299 to 0.0126) | (−0.0171 to –0.0049) |

| SE | 0.0067 | 0.0102 | 0.0029 |

| t-stat | −1.44 | −0.84 | −3.81 |

| p value | 0.156 | 0.408 | 0.001 |

| Fraction of maximum moving distance over normal time | |||

| coef | 0.0038 | 0.0022 | 0.0057 |

| 95% CI | (0.0014 to 0.0062) | (−0.0008 to 0.0053) | (0.0048 to 0.0066) |

| SE | 0.0012 | 0.0015 | 0.0004 |

| t-stat | 3.23 | 1.50 | 13.71 |

| p value | 0.002 | 0.147 | 0 |

| Home-stay minutes | |||

| coef | 0.0003 | 0.0008 | −0.0002 |

| 95% CI | (−0.0002 to 0.0008) | (0.0004 to 0.0011) | (−0.0004 to –0.00003) |

| SE | 0.0002 | 0.0002 | 0.0001 |

| t-stat | 1.32 | 4.46 | −2.40 |

| p value | 0.194 | 0.0002 | 0.027 |

| Latitude | |||

| coef | −0.0174 | −0.0333 | 0.0018 |

| 95% CI | (−0.0357 to 0.0009) | (−0.0492 to –0.0173) | (−0.0189 to 0.0224) |

| SE | 0.0091 | 0.0077 | 0.0098 |

| t-stat | −1.92 | −4.33 | 0.18 |

| p value | 0.061 | 0.0003 | 0.861 |

| Longitude | |||

| coef | 0.0068 | 0.0102 | 0.0027 |

| 95% CI | (0.0031 to 0.0105) | (0.0082 to 0.0122) | (0.0004 to 0.0049) |

| SE | 0.0018 | 0.0010 | 0.0011 |

| t-stat | 3.71 | 10.51 | 2.49 |

| p value | 0.001 | 0 | 0.023 |

| const | |||

| coef | 1.7386 | 2.1970 | 1.1837 |

| 95% CI | (1.1784 to 2.2988) | (1.6631 to 2.7309) | (1.1687 to 1.1985) |

| SE | 0.2774 | 0.2574 | 0.0071 |

| t-stat | 6.27 | 8.53 | 166.63 |

| p value | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Daily R values from 15 March to 25 April and temperature and relative humidity over 6 days up to and including the day when R value is measured, are used in the regression for 1005 US counties with more than 20 000 population. The regression is estimated by the Fama-MacBeth approach.

The influences of the temperature and relative humidity on the R values are quite similar before the lockdown in China and the USA: a 1°C increase in temperature is associated with an approximately 0.023 decrease (−0.026 (95% CI (−0.0395 to −0.0125)) in China and −0.020 (95% CI (−0.0311 to −0.0096)) in the USA) in the R value, and a 1% relative humidity rise is associated with an approximately 0.0078 decrease (−0.0076 (95% CI (−0.0108 to −0.0045)) in China and −0.0080 (95% CI (−0.0150 to −0.0010)) in the USA) in the R value. After lockdown, the temperature and relative humidity also present negative relationships with the R values for both countries. For China, it is statistically significant (with p values lower than 0.05), and a 1°C increase in temperature and a 1% increase in relative humidity are associated with a 0.0209 decrease (95% CI (−0.0378 to –0.0041)) and a 0.0054 decrease (95% CI (−0.0104 to –0.0004)) in the R value, respectively. For the USA, the estimated effects of temperature and relative humidity on the R values are still negative but no longer statistically significant (with p values of 0.141 and 0.073, respectively). The lesser influence of weather conditions is very likely caused by the stay-at-home policy during lockdown periods, when people are less exposed to the outdoor weather. Therefore, we rely more on the estimates of the weather–transmissibility relationship before the lockdowns in both countries.

Control variables

Several control variables also have significant influences on COVID-19 transmissibility. In China, before the lockdowns, in cities with higher levels of population density, the virus spreads faster than in less crowded cities due to more possible contacts among people. A 1000 people/km2 increase in population density is associated with a 0.1188 increase (95% CI (0.0573 to 0.1803)) in the R value before lockdown. Cities in China with more doctors have a smaller transmission intensity since the infections are treated in hospitals and hence are unable to be transmitted to others. In particular, 1000 more doctors are associated with a 0.0058 decrease (95% CI (−0.0090 to –0.0025)) in the R value during the overall time period; the influence of doctor number is greater before lockdown with a coefficient of 0.0109 (95% CI (−0.0163 to −0.0056)). Similarly, more developed cities (with higher GDP per capita) normally have better medical conditions; hence, patients are more likely to be cared for and thus unlikely to be transmitting the infection to others. A 10 000 Chinese Yuan GDP per capita increase is associated with a decrease in the R value by 0.0145 (95% CI (−0.0249 to −0.0040)) before the lockdown. In the USA, there is a strong relationship between the R value and the number of ICU beds per capita after lockdown, with a p value of 0.001; every unit increase in ICU bed per 10 000 population is associated with a 0.0110 decrease (95% CI (−0.0171 to –0.0049)) in the R value. Moreover, counties with more people over 65 years old have lower R values, but the magnitude is small, that is, a 1% increase in the fraction of individuals aged over 65 is associated with a 0.0092 decrease (95% CI (−0.0135 to –0.00498)) in the R value in the overall time period.

Absolute humidity

Absolute humidity, the mass of water vapour per cubic metre of air, relates to both temperature and relative humidity. A previous work shows that absolute humidity is a good solo variable explaining the seasonality of influenza.40 The results shown in table 3 are only partly consistent with this notion.40 In particular, for the US counties, relative humidity and absolute humidity are almost equivalent in explaining the variation in the R value (12.57% vs 12.55%), while absolute humidity does achieve a higher significance level (p value less than 0.00001) than relative humidity (p value of 0.019) before lockdown. However, the coefficient of absolute humidity is not statistically significant for Chinese cities (p value of 0.316).

Table 3.

Absolute humidity

| Temperature | Relative humidity | Absolute humidity | |

| Panel A: regression for Chinese cities | |||

| R2 | 0.1817 | 0.1783 | 0.1799 |

| Temperature | |||

| coef | −0.0151 | ||

| 95% CI | (−0.0262 to –0.0040) | ||

| SE | 0.0040 | ||

| t-stat | −3.78 | ||

| p value | 0.019 | ||

| Relative humidity | |||

| coef | −0.0038 | ||

| 95% CI | (−0.0060 to –0.0016) | ||

| SE | 0.0008 | ||

| t-stat | −4.83 | ||

| p value | 0.008 | ||

| Absolute humidity | |||

| coef | −0.0159 | ||

| 95% CI | (−0.0545 to 0.0227) | ||

| SE | 0.0139 | ||

| t-stat | −1.15 | ||

| p value | 0.316 | ||

| Population density | |||

| coef | 0.1222 | 0.1062 | 0.1190 |

| 95% CI | (0.0500 to 0.1943) | (0.0441 to 0.1684) | (0.0371 to 0.2010) |

| SE | 0.0260 | 0.0224 | 0.0295 |

| t-stat | 4.70 | 4.74 | 4.03 |

| p value | 0.009 | 0.009 | 0.016 |

| Percentage over 65 | |||

| coef | −0.3769 | −0.5738 | −0.8898 |

| 95% CI | (−1.6135 to 0.8597) | (−1.6715 to 0.5239) | (−1.9335 to 0.1538) |

| SE | 0.4454 | 0.3954 | 0.3759 |

| t-stat | −0.85 | −1.45 | −2.37 |

| p value | 0.445 | 0.220 | 0.077 |

| GDP per capita | |||

| coef | −0.0174 | −0.0190 | −0.0205 |

| 95% CI | (−0.0303 to –0.0046) | (−0.0328 to –0.0052) | (−0.0340 to –0.0069) |

| SE | 0.0046 | 0.0050 | 0.0049 |

| t-stat | −3.76 | −3.81 | −4.20 |

| p value | 0.020 | 0.019 | 0.014 |

| No of doctors | |||

| coef | −0.0109 | −0.0111 | −0.0111 |

| 95% CI | (−0.0167 to –0.0051) | (−0.0167 to –0.0054) | (−0.0168 to –0.0053) |

| SE | 0.0021 | 0.0020 | 0.0021 |

| t-stat | −5.21 | −5.45 | −5.37 |

| p value | 0.006 | 0.006 | 0.006 |

| Drop of BMI | |||

| coef | −0.5174 | −0.4236 | −0.5370 |

| 95% CI | (−0.8038 to –0.2309) | (−0.6320 to –0.2152) | (−0.8650 to –0.2090) |

| SE | 0.1032 | 0.0751 | 0.1181 |

| t-stat | −5.01 | −5.64 | −4.55 |

| p value | 0.007 | 0.005 | 0.010 |

| Inflow population from Wuhan | |||

| coef | −0.0006 | −0.0004 | −0.0005 |

| 95% CI | (−0.0010 to –0.0001) | (−0.0009 to 0.00003) | (−0.0010 to –8.04E–6) |

| SE | 0.0001 | 0.0002 | 0.0002 |

| t-stat | −3.70 | −2.57 | −2.82 |

| p value | 0.021 | 0.062 | 0.048 |

| Latitude | |||

| coef | 0.0283 | 0.0422 | 0.0396 |

| 95% CI | (0.0104 to 0.0461) | (0.0331 to 0.0512) | (0.0267 to 0.0525) |

| SE | 0.0064 | 0.0032 | 0.0046 |

| t-stat | 4.40 | 12.98 | 8.53 |

| p value | 0.012 | 0.0002 | 0.001 |

| Longitude | |||

| coef | −0.0299 | −0.0273 | −0.0289 |

| 95% CI | (−0.0559 to –0.0039) | (−0.0523 to –0.0023) | (−0.0543 to –0.0034) |

| SE | 0.0094 | 0.0090 | 0.0092 |

| t-stat | −3.19 | −3.03 | −3.15 |

| p value | 0.033 | 0.039 | 0.035 |

| const | |||

| coef | 2.1182 | 2.1184 | 2.1176 |

| 95% CI | (1.5681 to 2.6684) | (1.5667 to 2.6700) | (1.5682 to 2.6670) |

| SE | 0.1981 | 0.1987 | 0.1979 |

| t-stat | 10.69 | 10.66 | 10.70 |

| p value | 0.0004 | 0.0004 | 0.0004 |

| Panel B: regression for the US counties | |||

| R2 | 0.1210 | 0.1257 | 0.1255 |

| Temperature | |||

| coef | −0.0138 | ||

| 95% CI | (−0.0267 to –0.0009) | ||

| SE | 0.0062 | ||

| t-stat | −2.21 | ||

| p value | 0.038 | ||

| Relative humidity | |||

| coef | −0.0078 | ||

| 95% CI | (−0.0140 to –0.0014) | ||

| SE | 0.0031 | ||

| t-stat | −2.53 | ||

| p value | 0.019 | ||

| Absolute humidity | |||

| coef | −0.0496 | ||

| 95% CI | (−0.0664 to –0.0327) | ||

| SE | 0.0081 | ||

| t-stat | −6.11 | ||

| p value | 0 | ||

| Population density | |||

| coef | 6.51E−6 | 6.25E−6 | 5.50E−6 |

| 95% CI | (−0.00002 to 0.00004) | (−0.00003 to 0.00004) | (−0.00002 to 0.00004) |

| SE | 0.00002 | 0.00002 | 0.00001 |

| t-stat | 0.43 | 0.40 | 0.38 |

| p value | 0.671 | 0.689 | 0.711 |

| Percentage over 65 | |||

| coef | −0.9306 | −1.0137 | −0.9071 |

| 95% CI | (−1.5574 to –0.3038) | (−1.7090 to –0.3183) | (−1.6107 to –0.2034) |

| SE | 0.3022 | 0.3353 | 0.3393 |

| t-stat | −3.08 | −3.02 | −2.67 |

| p value | 0.005 | 0.006 | 0.014 |

| Gini | |||

| coef | −1.6920 | −1.8024 | −1.7177 |

| 95% CI | (−4.4260 to 1.0420) | (−4.3390 to 0.7342) | (−4.3598 to 0.9263) |

| SE | 1.3183 | 1.2231 | 1.2744 |

| t-stat | −1.28 | −1.47 | −1.35 |

| p value | 0.213 | 0.155 | 0.192 |

| Socioeconomic factor | |||

| coef | 0.1371 | 0.1265 | 0.1363 |

| 95% CI | (0.0842 to 0.1900) | (0.0783 to 0.1747) | (0.0914 to 0.1812) |

| SE | 0.0255 | 0.0232 | 0.0217 |

| t-stat | 5.38 | 5.44 | 6.30 |

| p value | 0.00002 | 0.00002 | 0 |

| No of ICU beds per capita | |||

| coef | −0.0122 | −0.0097 | −0.0127 |

| 95% CI | (−0.0359 to 0.0114) | (−0.0294 to 0.0100) | (−0.0351 to –0.0097) |

| SE | 0.0114 | 0.0095 | 0.0108 |

| t-stat | −1.07 | −1.02 | −1.17 |

| p value | 0.294 | 0.317 | 0.253 |

| Fraction of maximum moving distance over normal time | |||

| coef | 0.0005 | 0.0014 | 0.0011 |

| 95% CI | (−0.0038 to 0.0048) | (−0.0015 to 0.0043) | (−0.0023 to 0.0045) |

| SE | 0.0021 | 0.0014 | 0.0016 |

| t-stat | 0.24 | 0.98 | 0.65 |

| p value | 0.815 | 0.338 | 0.520 |

| Home-stay minutes | |||

| coef | 0.0006 | 0.0006 | 0.0006 |

| 95% CI | (0.0003 to 0.0009) | (0.0003 to 0.0010) | (0.0003 to 0.0010) |

| SE | 0.0001 | 0.0002 | 0.0002 |

| t-stat | 3.94 | 3.91 | 3.88 |

| p value | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| Latitude | |||

| coef | −0.0201 | −0.0097 | −0.0361 |

| 95% CI | (−0.0367 to –0.0036) | (−0.0174 to –0.0020) | (−0.0511 to –0.0211) |

| SE | 0.0080 | 0.0037 | 0.0072 |

| t-stat | −2.53 | −2.61 | −4.98 |

| p value | 0.019 | 0.016 | 0.00006 |

| Longitude | |||

| coef | 0.0104 | 0.0098 | 0.0107 |

| 95% CI | (0.0084 to 0.0123) | (0.0079 to 0.0117) | (0.0086 to 0.0128) |

| SE | 0.0009 | 0.0009 | 0.0010 |

| t-stat | 11.02 | 10.66 | 10.52 |

| p value | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| const | |||

| coef | 2.2121 | 2.1911 | 2.2137 |

| 95% CI | (1.6662 to 2.7580) | (1.6600 to 2.7222) | (1.6659 to 2.7616) |

| SE | 0.2632 | 0.2561 | 0.2641 |

| t-stat | 8.40 | 8.56 | 8.38 |

| p value | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Table 3 shows the explanatory power of the absolute humidity in the pre-lockdown period for Chinese cities from 19 to 23 January (panel A) and the US counties from 15 March to 6 April (panel B).

BMI, Baidu Mobility Index.

Lockdown and mobility

Intensive health emergency and lockdown policies have taken place since the outbreak of COVID-19 in both the USA and China. In the regression analysis, we use cross-sectional centralised (with sample mean extracted) explanatory variables, and thus, the intercepts in the regression models estimate the average R value of different time periods. In China, the health emergency policies on 24 January 2020 lowered the average R value from 2.1174 (95% CI (1.5699 to 2.6649)) to 0.8084 (95% CI (0.5334 to 1.0833)), which corresponds to a more than 60% drop. In the USA, the regression results of the data as of 25 April show that although the R value has not decreased to less than 1, the lockdown policies have reduced the average R value by nearly half, from 2.1970 (95% CI (1.6631 to 2.7309)) to 1.1837 (95% CI (1.1687 to 1.1985)).

We use the Baidu Mobility Index (BMI) drop as a proxy for intracity mobility change (compared with the normal time) in China. The regression results show that before the lockdown, a 1% decrease in BMI drop is associated with a decrease in the R value by 0.004093 (95% CI (−0.00683 to 0.001356)). After the lockdown, the BMI drop does not significantly affect the R value. A possible reason is that the BMI variations across cities are quite small (all at quite low levels) after the lockdown, as the paces of interventions in different Chinese cities are quite similar. Overall, the negative relationship before lockdown may also imply that the rapid response to infectious disease risks is crucial. For the USA, we use the M50 index, the fraction of daily median of maximum moving distance over that in the normal time (workdays between 17 February and 7 March), as the proxy of mobility. It has a positive relationship with the R value both overall and after-lockdown time period, with p values lower than 0.01, which demonstrates that counties with more social movements would have higher R values than others.

Robustness checks

We check the robustness of the influences of temperature/humidity on R values over four conditions:

Wuhan city. Among these 100 cities in China, Wuhan is a special case with the earliest outbreak of COVID-19. There was an increase of more than 13 000 cases on a single day (12 February 2020) due to the unification of testing standards with other regions of China.41 Therefore, as a robustness check, we remove Wuhan city from our sample and redo the regression analysis.

Different measurements of serial intervals. We also use serial intervals in a previous work (mean 7.5 days, SD 3.4 days based on 10 cases)3 with a Weibull distribution to estimate the R values of various cities/counties for robustness checks.

Social distancing dummy variables for the US counties. States in the USA announced stay-at-home orders at different times. We add a dummy variable that is set to one if the stay-at-home order is imposed and zero otherwise.

Spatial random effect. We also introduce a spatial model into the first step of the Fama-MacBeth regression to account for spatial correlation and redo the analysis.

The results of the aforementioned four robustness checks are shown in online supplemental tables 6–11. All of them show that temperature and relative humidity have a strong influence on R values with strong statistical significance, which is consistent with the reported results in tables 1 and 2.

bmjopen-2020-043863supp006.pdf (47.5KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-043863supp007.pdf (48.7KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-043863supp008.pdf (48.3KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-043863supp010.pdf (46.2KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-043863supp009.pdf (47.4KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-043863supp011.pdf (46KB, pdf)

Discussion

We identify robust negative correlations between temperature/relative humidity and the COVID-19 transmissibility using samples of the daily transmission of COVID-19, temperature and relative humidity for 100 Chinese cities and 1005 US counties. Although we use different datasets (symptom-onset data for Chinese cities and confirmed case data for the US counties) for different countries, we obtain consistent estimates. This result also aligns with the evidence that high temperature and high humidity can reduce the transmission of influenza,40 which can be explained by several potential reasons. The influenza virus is more stable in cold environments, and respiratory droplets, as containers of viruses, remain airborne longer in dry air.42 Cold and dry weather can also weaken host immunity and make the hosts more susceptible to the virus.43 Our result is also consistent with the evidence that high temperature and high relative humidity reduce the viability of SARS coronavirus.44 High transmission in cold temperatures may also be explained by behavioural differences; for instance, people may spend more time indoors and have a greater chance of interacting with others. Further studies should be performed to disentangle these multiple explanations and change the association relationship in our study to a causal effect.

Our study has several strengths. First, we use data from vast geographical scopes in both China and the US that contain a variety of meteorological conditions. Second, we employ all kinds of control variables such as demographics, socioeconomic status, geographical, healthcare and human mobility status factors as control variables to capture the effect of regional disparity. Third, we use the Fama-MacBeth regression framework to estimate associations between temperature/relative humidity and COVID-19 transmissibility when our data are non-stationary and in a short duration. Compared with the study by Merow and Urban26, which investigates the influence of meteorological conditions on COVID-19 infections with only population density and the proportion of individuals aged over 65 years considered as control variables, our study incorporates more categories of variables to explain the heterogeneity among different regions. Although a study by Yao et al27 has announced no association between COVID-19 transmission and temperature, they use a 2-month averaged temperature for analysis, and the temperature trends are not considered. A study by Xie and Zhu29 reports positive relationships between temperature and COVID-19 cases. However, the demographic factors for cities are not incorporated as controls, and the effectiveness of non-stationary time series problem for the panel regression methods they use is not explicitly discussed.

We do acknowledge several limitations. Our findings cannot verify the detailed mechanisms between temperature/relative humidity and COVID-19 transmissibility. Our study is a statistical analysis but not an experiment. These findings should be considered with caution when used for prediction. The R2 of our regression is approximately 30% in China and 12% in the USA, which means that approximately 70% to 88% of cross-city R value fluctuations cannot be explained by temperature and relative humidity (and controls). Moreover, the temperatures and relative humidity in our Chinese samples range from −21°C to 20°C and from 49% to 100%, respectively, and in the USA, the temperature and humidity range from −10°C to 29°C and from 16% to 99%, respectively; thus, it is still unknown whether these negative relationships still hold in extremely hot and cold areas. The slight differences between the estimates on the Chinese cities and the US counties might come from the different ranges of temperature and relative humidity.

Outwardly, our study suggests that the summer and rainy seasons can potentially reduce the transmissibility of COVID-19, but it is unlikely that the COVID-19 pandemic will ‘automatically’ diminish in summer. Cold and dry seasons can potentially break the fragile transmission balance and the weaken downward trends in some areas of the Northern Hemisphere.

Therefore, public health intervention is still necessary to block the transmission of COVID-19 even in the summer. In particular, as shown in this paper, lockdowns, constraints on human mobility, increases in hospital beds can potentially reduce the transmissibility of COVID-19. Given the relationship between temperature/relative humidity and COVID-19 transmissibility, policy-makers can adjust their intervention policy according to the different temperature/relative humidity conditions. When new infectious diseases emerge, our framework can also provide policy-makers with fast support, although this is not expected.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: JW initiated this project. JW, WL and FW planned and oversaw the project. KT and KC contributed econometrics methods. KF and XL prepared the datasets and conducted the analysis. KT, FW and JW wrote the manuscript with input from all authors.

Funding: This study was granted the State Key Research and Development Program of China (2019YFB2102100), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (92046010, 71531001, 61572059, 61421003), and BRICS STI Framework Programme: Response to COVID-19 global pandemic(MFQuantiC).

Map disclaimer: The depiction of boundaries on this map does not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of BMJ (or any member of its group) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, jurisdiction or area or of its authorities. This map is provided without any warranty of any kind, either express or implied.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available on reasonable request. Temperature, humidity, R values and all control variables except home-stay minutes used in this study are available on request from JW (jywang@buaa.edu.cn). Home-stay minute data provided by Safegraph (https://www.safegraph.com/) cannot be disclosed since this would compromise the agreement with the data provider; nevertheless, these data can be obtained by applying for permission from the provider.

author-note: This paper was previously circulated under the title “High Temperature and High Humidity Reduce the Transmission of COVID-19" (https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3551767).

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

References

- 1.WHO Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic, 2020. Available: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019

- 2.Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med 2020;382:727–33. 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li Q, Guan X, Wu P, et al. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia. N Engl J Med 2020;382:1199–207. 10.1056/NEJMoa2001316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bashir MF, Ma B, Shahzad L. A brief review of socio-economic and environmental impact of Covid-19. Air Qual Atmos Health 2020:1–7. 10.1007/s11869-020-00894-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ní Ghráinne B Covid-19, border closures, and international law, 2020. Available: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3662218

- 6.Bilal , Bashir MF, Benghoul M, Numan U, et al. Environmental pollution and COVID-19 outbreak: insights from Germany. Air Qual Atmos Health 2020;13:1385–94. 10.1007/s11869-020-00893-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Collivignarelli MC, Abbà A, Bertanza G, et al. Lockdown for CoViD-2019 in Milan: what are the effects on air quality? Sci Total Environ 2020;732:139280. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kraemer MUG, Yang C-H, Gutierrez B, et al. The effect of human mobility and control measures on the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Science 2020;368:493–7. 10.1126/science.abb4218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tian H, Liu Y, Li Y, et al. An investigation of transmission control measures during the first 50 days of the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Science 2020;368:638–42. 10.1126/science.abb6105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chinazzi M, Davis JT, Ajelli M, et al. The effect of travel restrictions on the spread of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak. Science 2020;368:395–400. 10.1126/science.aba9757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lai S, Ruktanonchai NW, Zhou L, et al. Effect of non-pharmaceutical interventions to contain COVID-19 in China. Nature 2020;585:410–3. 10.1038/s41586-020-2293-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jia JS, Lu X, Yuan Y, et al. Population flow drives spatio-temporal distribution of COVID-19 in China. Nature 2020;582:1–5. 10.1038/s41586-020-2284-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hsiang S, Allen D, Annan-Phan S, et al. The effect of large-scale anti-contagion policies on the COVID-19 pandemic. Nature 2020;584:262–7. 10.1038/s41586-020-2404-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang J, Litvinova M, Liang Y, et al. Changes in contact patterns shape the dynamics of the COVID-19 outbreak in China. Science 2020;368:1481–6. 10.1126/science.abb8001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hemmes JH, Winkler KC, Kool SM. Virus survival as a seasonal factor in influenza and polimyelitis. Nature 1960;188:430–1. 10.1038/188430a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dalziel BD, Kissler S, Gog JR, et al. Urbanization and humidity shape the intensity of influenza epidemics in U.S. cities. Science 2018;362:75–9. 10.1126/science.aat6030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shaman J, Pitzer VE, Viboud C, et al. Absolute humidity and the seasonal onset of influenza in the continental United States. PLoS Biol 2010;8:e1000316. 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shaman J, Goldstein E, Lipsitch M. Absolute humidity and pandemic versus epidemic influenza. Am J Epidemiol 2011;173:127–35. 10.1093/aje/kwq347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chattopadhyay I, Kiciman E, Elliott JW, et al. Conjunction of factors triggering waves of seasonal influenza. Elife 2018;7:e30756. 10.7554/eLife.30756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Killerby ME, Biggs HM, Haynes A, et al. Human coronavirus circulation in the United States 2014–2017. J Clin Virol 2018;101:52–6. 10.1016/j.jcv.2018.01.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Neher RA, Dyrdak R, Druelle V, et al. Potential impact of seasonal forcing on a SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Swiss Med Wkly 2020;150:w20224. 10.4414/smw.2020.20224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kissler SM, Tedijanto C, Goldstein E, et al. Projecting the transmission dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 through the postpandemic period. Science 2020;368:860–8. 10.1126/science.abb5793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baker RE, Yang W, Vecchi GA, et al. Susceptible supply limits the role of climate in the early SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Science 2020;369:eabc2535. 10.1126/science.abc2535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bashir MF, Ma B,Bilal, Komal B, et al. Correlation between climate indicators and COVID-19 pandemic in New York, USA. Sci Total Environ 2020;728:138835. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen C, Liu X, Wang X, et al. Effect of air pollution on hospitalization for acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, stroke, and myocardial infarction. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 2020;27:3384–400. 10.1007/s11356-019-07236-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Merow C, Urban MC. Seasonality and uncertainty in global COVID-19 growth rates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020;117:27456–64. 10.1073/pnas.2008590117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yao Y, Pan J, Liu Z, et al. No association of COVID-19 transmission with temperature or UV radiation in Chinese cities. Eur Respir J 2020;55:2000517 10.1183/13993003.00517-2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Al-Rousan N, Al-Najjar H. The correlation between the spread of COVID-19 infections and weather variables in 30 Chinese provinces and the impact of Chinese government mitigation plans. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2020;24:4565–71. 10.26355/eurrev_202004_21042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xie J, Zhu Y. Association between ambient temperature and COVID-19 infection in 122 cities from China. Sci Total Environ 2020;724:138201. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fama EF, French KR. The cross-section of expected stock returns. J Finance 1992;47:427–65. 10.1111/j.1540-6261.1992.tb04398.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kang W, Rouwenhorst KG, Tang KE. A tale of two premiums: the role of hedgers and speculators in commodity futures markets. J Finance 2020;75:377–417. 10.1111/jofi.12845 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Petersen MA Estimating standard errors in finance panel data sets: comparing approaches. Rev Financ Stud 2009;22:435–80. 10.1093/rfs/hhn053 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wallinga J, Teunis P. Different epidemic curves for severe acute respiratory syndrome reveal similar impacts of control measures. Am J Epidemiol 2004;160:509–16. 10.1093/aje/kwh255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.NYTimes See which states are reopening and which are still shut down, 2020. Available: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/us/states-reopen-map-coronavirus.html

- 35.Johns Hopkins University Coronavirus symptoms start about five days after exposure, Johns Hopkins study finds, 2020. Available: https://hub.jhu.edu/2020/03/09/coronavirus-incubation-period/

- 36.Hadri K Testing for stationarity in heterogeneous panel data. Econom J 2000;3:148–61. 10.1111/1368-423X.00043 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kao C Spurious regression and residual-based tests for cointegration in panel data. J Econom 1999;90:1–44. 10.1016/S0304-4076(98)00023-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fama EF, MacBeth JD. Risk, return, and equilibrium: empirical tests. J Polit Econ 1973;81:607–36. 10.1086/260061 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Newey WK, West KD, simple A, et al. Heteroskedasticity and autocorrelation consistent covariance matrix. Econometrica 1987;55:703–8. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shaman J, Kohn M. Absolute humidity modulates influenza survival, transmission, and seasonality. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009;106:3243–8. 10.1073/pnas.0806852106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nanfangzhoumo What’s the difficulty of Wuhan’s “all receivable.”, 2020. Available: https://www.infzm.com/contents/177054

- 42.Lowen AC, Steel J. Roles of humidity and temperature in shaping influenza seasonality. J Virol 2014;88:7692–5. 10.1128/JVI.03544-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kudo E, Song E, Yockey LJ, et al. Low ambient humidity impairs barrier function and innate resistance against influenza infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019;116:10905–10. 10.1073/pnas.1902840116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chan KH, Peiris JSM, Lam SY, et al. The effects of temperature and relative humidity on the viability of the SARS coronavirus. Adv Virol 2011;2011:1–7. 10.1155/2011/734690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-043863supp001.pdf (33.4KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-043863supp013.pdf (372KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-043863supp002.pdf (35.3KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-043863supp003.pdf (36KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-043863supp012.pdf (100.2KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-043863supp004.pdf (28.2KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-043863supp005.pdf (37.1KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-043863supp006.pdf (47.5KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-043863supp007.pdf (48.7KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-043863supp008.pdf (48.3KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-043863supp010.pdf (46.2KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-043863supp009.pdf (47.4KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-043863supp011.pdf (46KB, pdf)