Abstract

To minimize the risk of colliding with the ground or other obstacles, flying animals need to control both their ground speed and ground height. This task is particularly challenging in wind, where head winds require an animal to increase its airspeed to maintain a constant ground speed and tail winds may generate negative airspeeds, rendering flight more difficult to control. In this study, we investigate how head and tail winds affect flight control in the honeybee Apis mellifera, which is known to rely on the pattern of visual motion generated across the eye—known as optic flow—to maintain constant ground speeds and heights. We find that, when provided with both longitudinal and transverse optic flow cues (in or perpendicular to the direction of flight, respectively), honeybees maintain a constant ground speed but fly lower in head winds and higher in tail winds, a response that is also observed when longitudinal optic flow cues are minimized. When the transverse component of optic flow is minimized, or when all optic flow cues are minimized, the effect of wind on ground height is abolished. We propose that the regular sidewards oscillations that the bees make as they fly may be used to extract information about the distance to the ground, independently of the longitudinal optic flow that they use for ground speed control. This computationally simple strategy could have potential uses in the development of lightweight and robust systems for guiding autonomous flying vehicles in natural environments.

Keywords: optic flow, bee, flight, wind, speed, height

1. Introduction

To navigate safely and reliably within their environment, flying insects must be able to compensate for changes in wind speed and direction. Studies across different taxa suggest that flying insects rely primarily on visual information to regulate their airspeed when flying in head winds (mosquitoes: [1]; moths: [2–4]; Drosophila: [5]; aphids: [6]; locusts: [7]; honeybees: [8]). Of these species, both Drosophila and honeybees have been shown to maintain a constant ground speed in increasing head wind by holding the rate of longitudinal (front-to-back) optic flow constant [8,9]. It is currently unknown what determines the preferred rate of optic flow, but it appears to be innate and to remain constant irrespective of the visual environment [10,11].

If they are using optic flow experienced in the ventral visual field for ground speed regulation—as seems to be the case in bees [11–13]—a predicted consequence is that, when the insects can no longer produce enough thrust to compensate for a head wind (that is, to maintain constant the preferred rate of longitudinal optic flow), they will reduce their ground height. By flying closer to the ground, the magnitude of longitudinal optic flow experienced by the ventral part of the retina will increase for a set ground speed, and the preferred rate of longitudinal optic flow in the ventral visual field can be restored. A similar response might be predicted for flight in tail winds, except that the preferred rate of optic flow would then be maintained by increasing ground height to reduce the apparent rate of optic flow.

Do insects change their ground height when flying in head and tail winds? Observations made during field studies suggest that honeybees [14] and bumblebees [15] do indeed fly lower in head winds and higher in tail winds. In addition, honeybees have been shown to rely on optic flow cues to regulate their ground height [11–13] and to modify their ground height to maintain a constant optic flow when the rate of optic flow in the ventral visual field has been artificially manipulated [13]. These observations support the hypothesis that, in wind, bees will modify their distance from the ground in order to maintain a constant rate of optic flow. However, the sensory information used to regulate ground height remains unclear. Taylor et al. [16] found that tethered honeybees use a combination of optic flow and airspeed cues to regulate the ‘streamline’ response [17], whereby the orientation of their abdomen is modified to change drag. This response was proposed to play an important role for controlling flight in wind, but it remains unclear how it affects the free flight behaviour of honeybees.

The aim of the present study is to investigate how wind affects flight control in honeybees and to test the hypothesis that bees adjust their ground height in wind so as to maintain constant the rate of longitudinal optic flow in the ventral visual field. We record honeybees flying along an experimental tunnel in head and tail winds and find that both ground speed and ground height are affected by wind speed and direction. We then further explore the mechanism underlying ground speed and ground height control in wind by adding or removing the longitudinal (front-to-back) and transverse (sidewards) optic flow cues available to honeybees flying in both head and tail winds. The results suggest that honeybees rely on longitudinal optic flow cues to control their ground speed when flying in wind and that they appear to use transverse optic flow cues to control their ground height. When longitudinal optic flow cues are available, honeybees fly lower in head winds and higher in tail winds, but these adjustments do not result in a constant rate of longitudinal optic flow in the ventral visual field. Our analyses also suggest that bees make regular oscillations in the transverse component of their flight that appear to be unaffected by visual texture, wind or ground height. We hypothesize that these oscillations could be used to measure the transverse component of optic flow, which can provide an estimate of ground height that is independent of their forward speed.

2. Methods

(a). Training

The experiments were carried out in a greenhouse at the Australian National University. The temperature inside the facility was maintained at 24 ± 5°C during the day. A beehive mounted on the wall supplied the honeybees (Apis mellifera L.) used in the experiments. For each experiment, up to 16 honeybees were individually marked and trained to fly along a wind tunnel (electronic supplementary material, figure S1) to a feeder containing sugar solution placed at the end of the test section.

In each experiment, the pattern was displayed in the tunnel 2 days prior to testing and the bees were allowed to forage freely during this time. The training took place in still air with the wind conditions only being presented during the trials, which lasted for 30 min. Between trials, bees were allowed to visit the feeder in still air for at least 30 min to minimize any potential learning effects across trials. Each experiment was conducted over 3 days with each test (wind) condition being presented in a randomized order on each day (and three times in total per experiment). Details of the number of individual bees and number of flights recorded in each experiment are provided in table 1.

Table 1.

Ground speed for each visual texture and each wind condition in Experiments 1–4. N, number of individual bees; n, number of flights.

| head wind −2 m s−1 | head wind −1 m s−1 | still air 0 m s−1 | tail wind 1 m s−1 | tail wind 2 m s−1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mean ± std median [IQR] mm s−1 | mean ± std median [IQR] mm s−1 | mean ± std median [IQR] mm s−1 | mean ± std median [IQR] mm s−1 | mean ± std median [IQR] mm s−1 | |

| Experiment 1 cross-hatch | 379 ± 124 | 356 ± 60 | 362 ± 118 | 345 ± 118 | 300 ± 69 |

| 365 [302, 409] | 345 [322, 379] | 320 [276, 426] | 313 [272, 377] | 291 [239, 362] | |

| N = 11 | N = 13 | N = 10 | N = 10 | N = 10 | |

| n = 23 | n = 24 | n = 25 | n = 27 | n = 30 | |

| Experiment 2 longitudinal stripe | 1626 ± 275 | 1695 ± 217 | 1500 ± 197 | 1628 ± 166 | 1673 ± 244 |

| 1659 [1493, 1839] | 1714 [1612, 1836] | 1490 [1366, 1661] | 1625 [1514, 1751] | 1701 [1522, 1900] | |

| N = 13 | N = 11 | N = 11 | N = 16 | N = 15 | |

| n = 30 | n = 32 | n = 32 | n = 33 | n = 31 | |

| Experiment 3 transverse stripe | 255 ± 65 | 315 ± 79 | 340 ± 84 | 287 ± 92 | 303 ± 102 |

| 249 [212, 291] | 299 [276, 366] | 351 [288, 394] | 265 [231, 300] | 291 [235, 360] | |

| N = 13 | N = 10 | N = 10 | N = 10 | N = 11 | |

| n = 23 | n = 21 | n = 22 | n = 21 | n = 21 | |

| Experiment 4 blank | 577 ± 228 | 574 ± 210 | 709 ± 162 | 1087 ± 173 | 1237 ± 182 |

| 558 [372, 783] | 529 [404, 724] | 760 [578, 839] | 1110 [958, 1204] | 1237 [1089, 1346] | |

| N = 13 | N = 13 | N = 16 | N = 13 | N = 16 | |

| n = 27 | n = 24 | n = 25 | n = 27 | n = 30 |

(b). Experimental apparatus

The experiments were conducted in a square cross-section wind tunnel that was constructed of clear Perspex (for details, see electronic supplementary material, figure S1). The tunnel consisted of an entrance section, a test section and a settling chamber. The test section of the tunnel where the flights were filmed was 3.5 m in length and had a uniform cross-section of 200 mm × 200 mm. Head and tail winds were generated in the tunnel by a fan placed after the test section. Wind speeds in the test section were measured using both a hot-wire anemometer and a fan anemometer at 50, 10 and 150 mm from the walls and floor at the fan end and entry of the test section, and then calibrated with the voltage settings of the fan. The air speeds did not change across the test section of the tunnel as it had been specially designed to produce laminar airflow.

The tunnel and the camera that was positioned above it were covered with a white cloth to minimize reflections and to enable a clear view of the honeybees' body orientation and position. This also had the effect of minimizing optic flow cues in the bee's dorsal visual field, although the lens of the camera filming from above would have been visible as a small black circle in the white covering.

(c). Experimental conditions

In all experiments, flights were recorded in head and tail winds of 1 or 2 m s−1, or in still air when the tunnel walls and floor displayed one of four different visual textures. The wind speeds were limited by the maximum speed that bees would fly at in a tail wind: at speeds superior to 2 m s−1, the bees would either land on the floor or turn around and fly out of the tunnel. The patterns used in each experiment were created by attaching strips of red electrical tape (18 mm wide) to sheets of white laminated paper, 3.5 m long and 200 mm wide, and fixed to the outside of the tunnel—attaching the patterns to the inside may have led to unwanted turbulence—leading to a 210 mm distance between the visual textures on the walls (calculated by adding the width of the Perspex on the walls, 5 mm to the internal width of 200 mm). Note that the placement of the patterns on the outside would have caused additional visual cues in the tunnel such as internal reflections and glare but these would have had a lower contrast than the visual textures. The strips of tape were distributed evenly along either the length or width of the paper with a 40 or 25 mm edge-to-edge separation for the longitudinal and transverse strips, respectively.

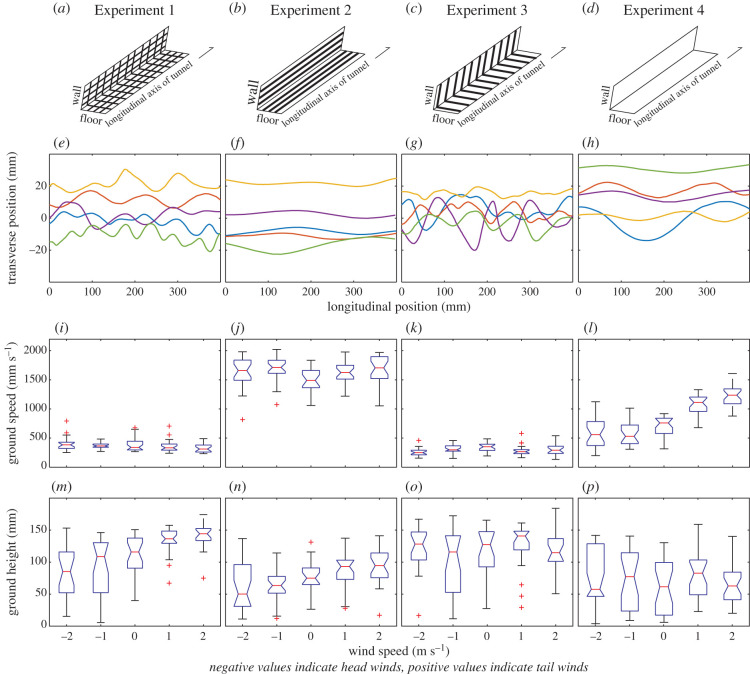

The visual textures were designed to test the effect of removing transverse and longitudinal optic flow cues on the flight control of bees flying in wind and still air. In Experiment 1, the tunnel was lined with a cross-hatch pattern consisting of transverse and longitudinal stripes (figure 1a) that provided strong longitudinal and transverse optic flow cues for bees flying to the feeder. In Experiment 2, the tunnel was lined with stripes oriented along the longitudinal axis of the tunnel to generate strong transverse optic flow cues, while minimizing longitudinal optic flow cues (figure 1b). In Experiment 3, the tunnel was lined with stripes oriented along the transverse axis of the tunnel to generate strong longitudinal optic flow cues, while minimizing transverse optic flow cues (figure 1c). In Experiment 4, the tunnel was lined with blank white sheets, minimizing both transverse and longitudinal optic flow cues (figure 1d).

Figure 1.

The effect of wind and visual texture on flight control in honeybees. (a–d) The visual textures used in Experiments 1–4. (e–h) Example trajectories from different individual bees flying in each of the experiments and wind conditions: head wind 2 m s−1 (red) and 1 m s−1 (blue), tail wind 2 m s−1 (green) and 1 m s−1 (purple) and still air (yellow) (note that data from the same colour-matched flights are also used in figures 2 and 3). (i–l) Mean ground speed values and (m–p) mean ground height values for head winds (negative values), still air (0 m s−1) and tail winds (positive values) in Experiments 1–4. Boxes indicate the distance between the lower and upper quartile values, horizontal lines indicate the median value and whiskers indicate the extent of the rest of the data. Crosses indicate values that exceed 1.5 times the interquartile range. Notches represent the 95% confidence of the median value. See table 1 for details of the number of bees and number of flights in each condition. (Online version in colour.)

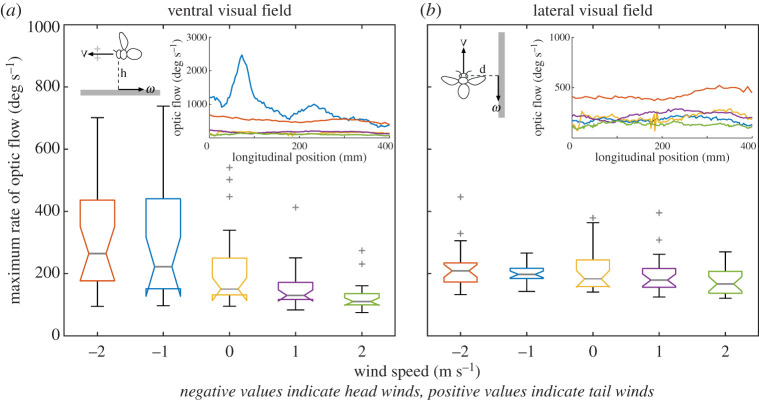

To investigate whether the bees were adjusting their ground speed and ground height in wind to maintain a constant rate of longitudinal optic flow in the lateral and ventral visual fields, we calculated the average maximum rate of longitudinal (front-to-back) optic flow generated in both the ventral and lateral visual fields in each flight trajectory. The maximum rate of longitudinal optic flow in the ventral visual field was calculated in deg s−1 as (V/h) * (180/π), where V is the mean ground speed in mm s−1 and h is the height above the ground in mm. The maximum rate of longitudinal optic flow in deg s−1 that would have been experienced in each flight in the lateral visual field was calculated as (V/d) * (180/π), where V is the mean ground speed in mm s−1 and d is 105 mm (the mean distance between the bees and the wall pattern due to the centring response [18]). This analysis was performed for Experiment 1, where the bees experienced strong longitudinal and transverse optic flow cues.

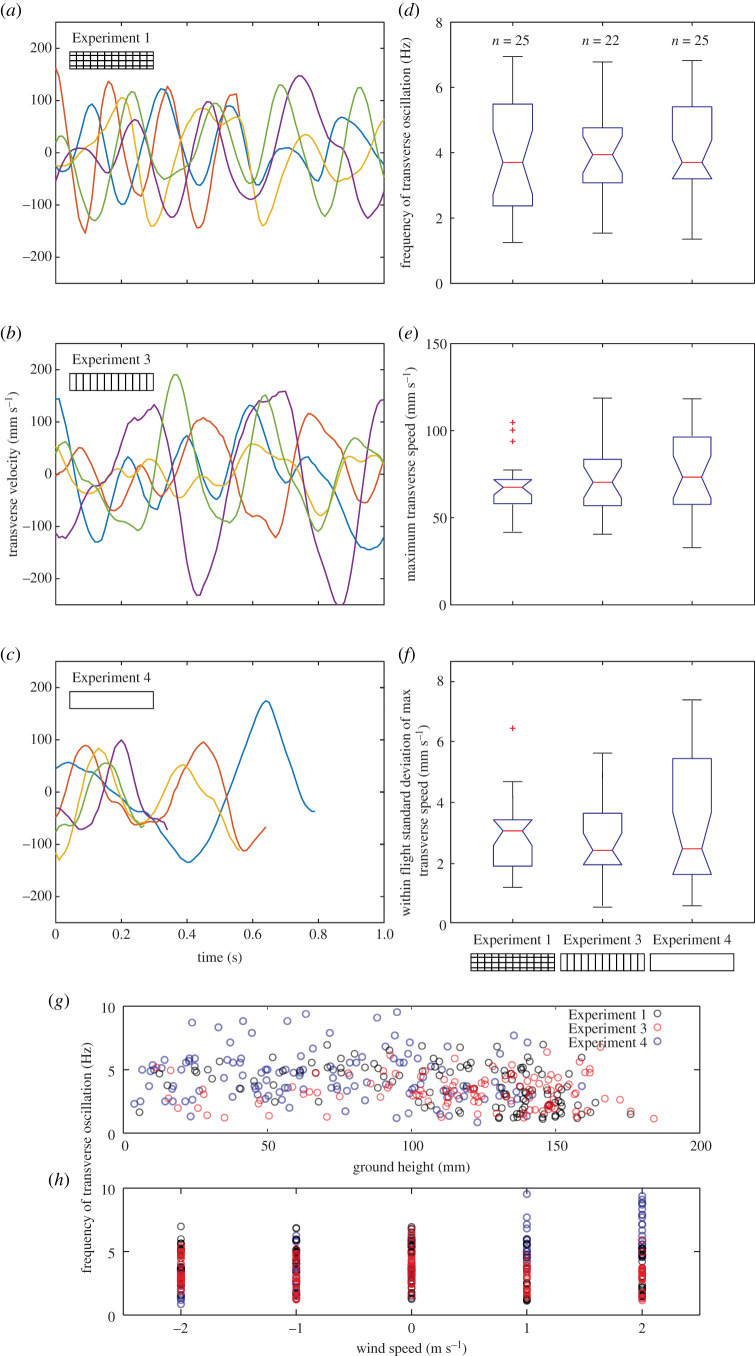

(d). Effect of visual texture on the transverse component of flight

An initial observation of the flights suggested that they contained regular transverse oscillations (figure 1e–h). To investigate whether these oscillations were indeed regular and whether they were affected by the properties of the visual texture, three additional analyses were conducted on the flight data for the still air (0 wind speed) condition and compared across Experiments 1, 3 and 4. Data from Experiment 2 were excluded from this analysis because there were too few data points per flight to perform an accurate frequency analysis due to the high ground speeds in this experiment.

Fourier transform analyses were performed on the transverse velocity values obtained from each individual flight using Matlab (Mathworks, USA). Observations of the individual power spectra for each flight confirmed the initial observation that, in almost all flights, the transverse oscillations contained a single, dominant frequency (that is, the frequency with the highest power). The dominant frequency value for each flight was then averaged and compared across treatments.

The maximum transverse speed for each oscillation within individual flights was identified by locating the point where the preceding and succeeding values were smaller, indicating a maximum. A Gaussian filter of 60 ms (std = 2.5 ms) was applied to the velocity data to remove the noise (caused by tracking inaccuracies) before performing this analysis in order to be able to accurately identify the maximum speed for each transverse oscillation. The mean and standard deviation of all the maximum transverse speed values were then calculated for each flight.

(e). Image analysis

Flights in the test section en route to the feeder were filmed at a rate of 100 Hz using two synchronized CMOS cameras (MotionPro 10 k, Redlake Inc.). The optical axes of the cameras were positioned orthogonal to each other such that one camera provided a top-view of the honeybees' flight trajectories along the tunnel, while the other provided a view along the length of the tunnel. Flights were recorded over a distance of 400 mm in the tunnel's mid-section and later tracked in image sequences recorded from each camera view using an automated tracking program developed in-house.

(f). Data analysis

Ground speed was calculated from the camera that was positioned above the mid-section of the tunnel; ground height was calculated from the camera that was positioned with an end-on view of the tunnel. The pixel positions of the honeybee in each camera view were converted to mm values using the known size and position of objects in the tunnel. The error associated with this method of converting pixel coordinates to three-dimensional world coordinates was determined to be below 10 mm from calculations of objects of known size.

The mean ground speed and ground height values were calculated for individual flights. Unless otherwise stated, all values are given as the mean ± std.

(g). Statistical analysis

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests and linear mixed models using ‘anova’ and the ‘lme’ function from the ‘nlme’ package in R (R Core [19]) were used to analyse the effect of wind speed on the tested flight parameters in the experiments after confirming that the data were normally distributed (see electronic supplementary material for the data, details of the models and the output of the statistical analyses). Bee identity was included as a random effect in the linear mixed models to account for the variation between and within flights from individual bees. The models followed the formula (in R code): model <- lme(fixed = Flight parameter ∼ Treatment, random = ∼ 1|BeeID). The significance of each explanatory variable was assessed using Wald tests (at the 5% level).

3. Results

(a). Effect of wind on flight control

Ground speed (figure 1i–l) and ground height (figure 1m–p) data from all experiments are summarized in tables 1 and 2, respectively. In the presence of strong longitudinal and transverse optic flow cues (Experiment 1), wind speed and direction did not significantly affect ground speed (t100 = −1.86, p = 0.0647, figure 1i). By contrast, ground height was affected by wind speed (t100 = 4.23, p < 0.0001, figure 1m), decreasing with increasing head wind and increasing with increasing tail wind.

Table 2.

Ground height for each visual texture and wind condition in Experiments 1–4. See table 1 for the number of individual bees and number of flights in each condition.

| head wind −2 m s−1 | head wind −1 m s−1 | still air 0 m s−1 | tail wind 1 m s−1 | tail wind 2 m s−1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mean ± std median [IQR] mm | mean ± std median [IQR] mm | mean ± std median [IQR] mm | mean ± std median [IQR] mm | mean ± std median [IQR] mm | |

| Experiment 1 cross-hatch | 87 ± 43 | 93 ± 46 | 113 ± 28 | 134 ± 21 | 142 ± 19 |

| 86 [53, 117] | 110 [53, 132] | 117 [91, 139] | 138 [131, 150] | 146 [135, 154] | |

| Experiment 2 longitudinal stripe | 63 ± 40 | 61 ± 26 | 76 ± 27 | 87 ± 28 | 95 ± 27 |

| 50 [31, 96] | 63 [52, 78] | 75 [65, 91] | 93 [73, 103] | 94 [75, 114] | |

| Experiment 3 transverse stripe | 118 ± 39 | 97 ± 51 | 118 ± 39 | 125 ± 37 | 117 ± 32 |

| 128 [103, 147] | 116 [52, 141] | 127 [93, 148] | 141 [119, 148] | 115 [101, 137] | |

| Experiment 4 blank | 78 ± 44 | 71 ± 44 | 59 ± 42 | 78 ± 33 | 67 ± 32 |

| 58 [47, 129] | 77 [24, 115] | 62 [17, 100] | 83 [49, 103] | 63 [41, 84] |

(b). Effect of visual texture on flight control in wind

When longitudinal optic flow cues were minimized in Experiment 2, wind had no strong effect on ground speed (t99 = 1.83, p = 0.0698, figure 1j). Unlike in Experiment 1, in both head and tail wind, ground speed increased to a value that was four times faster than that recorded in still air in Experiment 1. As in Experiment 1, ground height was affected by the speed and direction of the wind (t99 = 3.49, p < 0.0001, figure 1n), decreasing from the still air value in head winds and increasing in tail winds.

When transverse optic flow cues were minimized in Experiment 3, wind affected ground speed (t91 = −2.37, p = 0.0199, figure 1k), which decreased in both head and tail winds as in Experiment 1. Wind also affected ground height (t91 = 2.64, p = 0.0096, figure 1o), but there was no evidence for a systematic decrease in head winds or increase in tail winds, as observed in Experiment 1.

When both transverse and longitudinal optic flow cues were minimized in Experiment 4, ground speed was affected by both head and tail winds (t105 = 11.34, p < 0.0001, figure 1l) and, in still air, it was nearly twice the value obtained in Experiment 1. As in Experiments 1 and 2, ground speed decreased in head winds and increased in tail winds. As in Experiment 3, the speed and direction of wind did not significantly affect ground height (t105 = 0.76, p = 0.4462, figure 1p).

(c). Effect of wind on optic flow experienced in the ventral and lateral fields

To explore whether bees modified their ground height in wind to maintain constant the rate of longitudinal optic flow in the ventral visual field, we calculated the average maximum rate of longitudinal optic flow that the bees would have experienced in their ventral and lateral visual field in Experiment 1 (figure 2). There was some indication that the perceived rate of optic flow in ventral visual field was affected by wind speed and direction (t100 = −2.17, p = 0.0326, figure 2a), but this effect was less evident in the lateral visual field (t100 = −1.87, p = 0.0647, figure 2b).

Figure 2.

The effect of wind on the maximum rate of longitudinal optic flow experienced in the ventral and lateral visual fields in Experiment 1. (a) The maximum rate of longitudinal optic flow in deg s−1 (ω) that would have been experienced in each flight in the ventral visual field—calculated as (V/h) * (180/π), where V is the mean ground speed in mm s−1 and h is the height above the ground in mm. Inset: The maximum ventral optic flow calculated from the example trajectories shown in figures 1e and 3a. (b) The maximum rate of longitudinal optic flow in deg s−1 (ω) that would have been experienced in each flight in the lateral visual field—calculated as (V/d) * (180/π), where V is the mean ground speed in mm s−1 and d is the distance to the wall pattern, 105 mm. Because of the lateral oscillations, the distances d1 and d2 to the two wall patterns will oscillate in anti-phase, as will the magnitudes of optic flow generated by the two walls. However, their sum, which would be approximately constant over time due to the centring response [18], is obtained by using the mean lateral distance, d [= (d1 + d2)/2]. Inset: The maximum ventral (a) and lateral (b) optic flow from the same example trajectories shown in figures 1e and 3a: head wind 2 m s−1 (red) and 1 m s−1 (blue), tail wind 2 m s−1 (green) and 1 m s−1 (purple) and still air (yellow). See figure 1 for box plot details and table 1 for details of the number of bees and flights in each condition. (Online version in colour.)

(d). Transverse oscillations as a potential ground height control mechanism

The data presented here suggest that, when transverse optic flow cues are present, ground height decreases in head winds and increases in tail winds. When transverse optic flow cues are minimized, however, ground height is no longer affected by wind speed or direction. One possible explanation for this result is that honeybees use the rate of optic flow generated from the transverse component of flight in the ventral visual field to regulate their ground height in wind. Regular oscillations in either position or velocity in the transverse direction (see examples in figures 1e–h and 3a–c) would generate a transverse component of optic flow with a magnitude that depends on the distance to the ground but is independent of the longitudinal component (which is being used to control flight speed [10]). If bees do use the transverse component of flight to estimate ground height, five predictions can be tested using the data gathered in this study: (i) that height control is affected when the transverse component of optic flow is minimized (as is the case in Experiments 3 and 4), (ii) that the oscillations are regular throughout the flight (so that subsequent measurements of the translational component of optic flow could be compared), (iii) that the oscillations are regulated independently of visual information, that is, they should not be affected by differences in the experimental patterns, and (iv) that they are unaffected by ground height or (v) wind.

Figure 3.

Analysis of transverse oscillations. (a–c) Examples showing how the transverse velocity of flights varies with time in Experiments 1 (a), 3 (b) and 4 (c). Line colours indicate the wind condition: head wind 2 m s−1 (red lines) and 1 m s−1 (blue), tail wind 2 m s−1 (green) and 1 m s−1 (purple), and still air (yellow), with the data being taken from the same example trajectories shown in figure 1e–h. Note that the flights in Experiment 2 were excluded as they had too few data points to perform reliable analyses. The effect of visual textures used in Experiments 1, 3 and 4 on (d) the dominant frequency component of the transverse speed oscillations for each flight in still air. (e) The mean maximum speed of the transverse oscillations and (f) the standard deviation of the maximum transverse speed in each flight. (g) The relationship between the dominant frequency component and mean ground height and h wind condition for each flight in Experiments 1 (black circles), 3 (red circles) and 4 (blue circles). See figure 1 for box plot details and table 1 for details of the number of bees and flights in each condition. (Online version in colour.)

To explore whether our data match these predictions, key features of the transverse component of flight were compared across different optic flow conditions in still air: the dominant frequency of transverse oscillation, the maximum transverse speed of each oscillation, the within-flight variation of the value of maximum transverse speed and the relationship between ground height and wind and the dominant frequency of oscillation (figure 3). The results from Experiment 2 were not included in this comparison as each flight contained too few data points (due to the high ground speeds) to permit a reliable analysis. Examples of how the transverse speed of trajectories vary with time for Experiments 1, 3 and 4 are provided in figure 3a–c (using data from the trajectories shown in figure 1d–f).

In still air, the dominant frequency component of transverse oscillation had a mean value of 4.7 ± 1.6 Hz and was not significantly affected by the visual texture (n = 72, F3 = 0.02, p = 0.9828, figure 3d). Similarly, visual texture had no detectable effect on the mean or the within-flight standard deviation of the maximum transverse speed (mean: 73 ± 26 mm s−1, F3 = 0.97, p = 0.3854, figure 3e; standard deviation: 30 ± 16 mm s−1, F3 = 0.85, p = 0.4317, figure 3f). To explore if the frequency of the transverse oscillations was affected by ground height or wind condition, additional analyses were made where linear regressions were fitted to all data from Experiments 1, 3 and 4. The regression models indicated that there is a weak negative relationship between frequency and ground height: frequency = 5.2–0.01 * ground height (in mm) (adjusted R2 = 0.07, T349 = −5.3, p < 0.0001, figure 3g) and a weak positive relationship between frequency and wind speed: frequency = 4 + 0.27 * wind speed (in m s−1), (adjusted R2 = 0.03, T349 = 3.50, p = 0.0005, figure 3h) but, in both cases, the models explained less than 10% of the variance. Taken together, these results suggest that the transverse component of flight is not strongly affected by the presence or absence of longitudinal or transverse optic flow cues, wind condition or ground height.

4. Discussion

We began this study by investigating the effect of wind on flight control in honeybees (Experiment 1, cross-hatch). The bees maintained a similar ground speed, irrespective of whether they were flying in head or tail winds up to 2 m s−1, whereas ground height tended to decrease in head winds and increase in tail winds. When longitudinal optic flow cues were removed from the visual pattern (Experiments 2 and 4, longitudinal stripes and blank, respectively), ground speed was affected by wind. When transverse optic flow cues were removed (Experiments 3 and 4, transverse stripes and blank, respectively), wind no longer had an effect on ground height. An analysis of the transverse component of flight suggested that bees make regular oscillations in their transverse position and speed that are independent of visual texture (figures 1e–h and 3). We hypothesize that the bees could be using the transverse optic flow generated by these movements to determine and control their distance to the ground.

The results of Experiment 1 demonstrate the robustness of the honeybees' mechanism of visually guided ground speed control to both head and tail winds. Ground speed remained remarkably constant: in head winds, bees flew at airspeeds that were more than six times higher than the airspeed experienced in still air (2379 versus 362 mm s−1, table 1), while in tail winds, they were flying backwards relative to the air (−1700 mm s−1, table 1). Thus, in both head and tail winds and when strong optic flow cues are present, honeybees adjust their airspeed so as to maintain a constant ground speed. The findings of this study support those of Barron & Srinivasan [8], which showed that honeybees fly at a constant ground speed in head winds of up to 3.8 m s−1. It is interesting to note that in preliminary trials, when tail winds exceeded 2 m s−1, rather than flying along the tunnel, the bees would either land on the floor or turn around to fly into the wind. This behaviour may be related to the constraints of the experimental set-up or may reflect that bees tend to avoid flying in strong tail winds, perhaps because they lose the ability to control flight at high negative airspeeds.

Unlike ground speed, however, honeybees adjusted their ground height in wind, flying lower in head winds and higher in tail winds. This finding is consistent with the field observations of Wenner [14] and Riley et al. [15] and our initial hypothesis that bees would adjust their ground height in wind to maintain a constant rate of longitudinal optic flow in the ventral field. However, the change in ground height observed in this study did not lead to a constant rate of optic flow in the ventral visual field, as the bees maintained a constant forward speed in both head and tail winds. This is confirmed by an analysis of the maximum rate of longitudinal optic flow that would have been experienced in each flight in the ventral visual field (figure 2a) in comparison to the lateral visual field (figure 2b). This result is also inconsistent with the findings of Portelli et al. [13], which found that bees presented with a moving pattern on the floor in still air would modify their ground height to maintain a constant rate of optic flow in the ventral visual field. It is important to note that two main differences between the present study and that of Portelli et al. [13] make direct comparisons of the findings difficult: here, (i) the bees were responding to variations in wind speed and direction, rather than floor pattern movement and (ii) they were presented with patterns on the walls and not just the floor. Bees appear to be able to flexibly measure where in the visual field they measure optic flow cues for flight control [11,20] and there is evidence that parallel systems mediate the control of ground speed and height [21], making it difficult to determine exactly what values of optic flow they might have been measuring in Experiment 1. Additionally, it is possible that airspeed in combination with optic flow plays an important role in flight control. For example, Roy Khurana & Sane [22] found that antennal positioning in bees was mediated by a combination of airflow and optic flow and that airflow was particularly important when visual cues were minimized. Further studies in which airflow and optic flow are manipulated are necessary to determine the relative roles of these cues in flight control in honeybees.

When only the longitudinal optic flow cues were removed from the visual scene (Experiment 2, longitudinal stripes), ground speed increased dramatically, although it was not systematically affected by wind speed and direction. This is consistent with the results of Barron & Srinivasan [8], who found that bees flew at similar elevated ground speeds across a range of head winds when the tunnel displayed a similar longitudinal stripe pattern. This finding is puzzling as honeybees use longitudinal optic flow cues to control their ground speed [10,23] and should, therefore, not be able to maintain a constant ground speed when these cues are minimized. Indeed, when all strong contrast cues were removed from the tunnel walls (Experiment 4, blank), the bees no longer flew at a constant ground speed but rather flew slower in head winds and faster in tail winds. Barron & Srinivasan [8] speculated that, in their study, the bees may have acquired some longitudinal optic flow information from small imperfections in the striped tunnel patterns and this may also be the case for the present study. It is intriguing, however, that the bees do not fly at similar elevated speeds when optic flow cues are minimized (Experiment 4), when arguably the same imperfections would be available. The phenomenon of contrast adaptation [24], where the presence of a high-contrast texture obscures the visibility of low-contrast irregularities or imperfections, may have caused the bees to experience zero longitudinal optic flow in Experiment 2, and, therefore, fly at a constant, pre-set maximum speed that was dictated by the overall geometry of the tunnel (e.g. its length). In Experiment 4, on the other hand, low-contrast irregularities (e.g. reflections and glare on the internal surfaces of the tunnel) would have been visible, and the bees could have used the resulting weak translational flow cues to only partially compensate for the head and tail winds in regulating their ground speed.

Unlike ground speed, ground height varied with wind speed and direction when longitudinal optic flow cues were minimized (Experiment 2, longitudinal stripes) in a similar manner to the response observed in Experiment 1 (cross-hatch): bees flew lower in head winds and higher in tail winds. This suggests that the ground height response to wind was largely unaffected by the absence of strong longitudinal optic flow cues. In comparison, when both longitudinal and transverse optic flow cues were minimized (Experiment 4, blank), the variation in ground height increased greatly and was unaffected by wind speed and direction, suggesting that it was no longer being well controlled. A similar effect can be observed when transverse optic flow cues were minimized (Experiment 3, transverse stripes), with ground height no longer varying with wind speed and direction. Taken together, the results from this study suggest that, in wind, longitudinal optic flow cues play a role in ground speed regulation while ground height regulation appears to be mediated by transverse optic flow cues. This is consistent with the conclusions of Lecoeur et al. [20] that, in bumblebees, ground speed and ground height appear to be controlled by two systems with different preferred optic flow set-points working in parallel.

How could bees be using transverse optic flow cues for ground height control? Here, we hypothesize that bees may be using modulations in the transverse component of their flight. These sideways movements are likely to be generated by the periodic roll movements of the bee's thorax that occur in flight [25]. During such thorax roll oscillations, the head is held stable and close to horizontal with respect to the roll axis, thereby minimizing rotational optic flow [25]. If this modulation is a fixed (or calibrated) action pattern—such as that which might be generated by regular changes in thorax roll attitude—then the resulting modulation in transverse optic flow would vary with the distance to the ground. Lower magnitudes of transverse optic flow would indicate a higher altitude, and vice versa. For this strategy to function, an essential feature would be a regular and consistent oscillation or modulation of transverse speed that is generated independently of visual input and ground height. Indeed, our analyses of the transverse component of flight indicate that bees do make regular, near-sinusoidal oscillations in transverse speed that are not strongly affected by variation in visual texture, ground speed or ground height (figure 3). A similar robustness was observed in both the maximum transverse speed and the within-flight variation of maximum transverse speed, suggesting that these oscillations are quite consistent across conditions (figure 3). If information about changes in airspeed and optic flow during the transverse motions are combined, as postulated by Srinivasan [18], then an absolute estimate of distance to the ground could also be obtained. The attractive feature of such a strategy is that it would provide a true estimate of altitude, regardless of head winds, tail winds or crosswinds as such winds would simply generate a baseline level of optic flow upon which the modulation is superimposed. This independent estimate of altitude could be used to adjust the height above ground to suit the prevailing wind conditions: in the presence of a strong head wind, it might be useful to obtain wind cover by flying at lower altitudes [15]. In future studies, it would be informative to examine whether sensing of the air speed in the flight direction (for example, by the antennae) is used as an input to control the height above the ground, while the height is being sensed by the lateral oscillations. This strategy could also be usefully applied for the guidance of autonomous drones, given recent advances in the development of electromechanical whiskers for sensing airspeed (e.g. [26]).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Data accessibility

The full dataset (including individual flight data) used to generate the figures and perform the statistical analyses presented is available in the electronic supplementary material (file name: Data.xlsx) and from the Dryad Digital Repository: https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.ffbg79csj [27].

Authors' contributions

E.B. and M.V.S. conceived the study. E.B. collected the data; E.B. and N.B. analysed the data. E.B. interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors edited and revised the final manuscript version.

Competing interests

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

This research was partly supported by a grant from the US Air Force Office of Scientific Research (AOARD: Contract no. F62562-01-P0155), and Australian Research Council Grants FF0241328 and CE0561903 to M.V.S. and by a grant from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (grant no. 5433058) to N.B.

References

- 1.Kennedy JS 1940. The visual responses of flying mosquitoes. Proc. Zool. Soc. Lond. A 109, 221–242. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kennedy JS, Marsh D. 1974. Pheromone-regulated anemotaxis in flying moths. Science 184, 999–1001. ( 10.1126/science.184.4140.999) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuenen LPS, Baker TC. 1982. Optomotor regulation of ground velocity in moths during flight to sex pheromone at different heights. Physiol. Entomol. 7, 193–202. ( 10.1111/j.1365-3032.1982.tb00289.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Preiss R 1987. Motion parallax and figural properties of depth control flight speed in an insect. Biol. Cybern. V57, 1–9. ( 10.1007/BF00318711) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.David CT 1979. Height control by free-flying Drosophila. Physiol. Entomol. 4, 209–216. ( 10.1111/j.1365-3032.1979.tb00197.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kennedy JS, Thomas AAG. 1974. Behaviour of some low-flying aphids in wind. Ann. Appl. Biol. 76, 143–159. ( 10.1111/j.1744-7348.1974.tb07968.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baker PS 1978. Flying locust visual responses in a radial wind tunnel. J. Comp. Physiol. A 131, 39–47. ( 10.1007/BF00613082) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barron A, Srinivasan MV. 2006. Visual regulation of ground speed and headwind compensation in freely flying honey bees (Apis mellifera L.). J. Exp. Biol. 209, 978–984. ( 10.1242/jeb.02085) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.David CT 1982. Compensation for height in the control of groundspeed by Drosophila in a new ‘Barber's Pole’ wind tunnel. J. Comp. Physiol. A 147, 485–493. ( 10.1007/BF00612014) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baird E, Srinivasan MV, Zhang S, Cowling A. 2005. Visual control of flight speed in honeybees. J. Exp. Biol. 208, 3895–3905. ( 10.1242/jeb.01818) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Linander N, Baird E, Dacke M. 2016. Bumblebee flight performance in environments of different proximity. J. Comp. Physiol. A 202, 97–103. ( 10.1007/s00359-015-1055-y) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baird E, Srinivasan MV, Zhang S, Lamont R, Cowling A. 2006. Visual control of flight speed and height in the honeybee. In From Animals to Animats 9 (eds S Nolfi et al.), SAB 2006. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol. 4095, pp. 40–51. Berlin, Germany: Springer. ( 10.1007/11840541_4) [DOI]

- 13.Portelli G, Ruffier F, Franceschini N. 2010. Honeybees change their height to restore their optic flow. J. Comp. Physiol. A 196, 307–313. ( 10.1007/s00359-010-0510-z) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wenner AM 1963. The flight speed of honeybees: a quantitative approach. J. Apic. Res. 2, 25–32. ( 10.1080/00218839.1963.11100053) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Riley JR, Reynolds DR, Smith AD, Edwards AS, Osborne JL, Williams IH, McCartney HA. 1999. Compensation for wind drift by bumble-bees. Nature 400, 126 ( 10.1038/22029) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taylor GJ, Luu T, Ball D, Srinivasan MV. 2013. Vision and air flow combine to streamline flying honeybees. Sci. Rep. 3, 2614 ( 10.1038/srep02614) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luu T, Cheung A, Ball D, Srinivasan MV. 2011. Honeybee flight: a novel ‘streamlining’ response. J. Exp. Biol. 214, 2215–2225. ( 10.1242/jeb.050310) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Srinivasan MV 1993. How insects infer range from visual motion. Rev. Oculomot. Res. 5, 139–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.R Core Team. 2018. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lecoeur J, Dacke M, Floreano D, Baird E. 2019. The role of optic flow pooling in insect flight control in cluttered environments. Sci. Rep. 9, 7707 ( 10.1038/s41598-019-44187-2) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lecoeur J, Baird E, Floreano D. 2018. Spatial encoding of translational optic flow in planar scenes by elementary motion detector arrays. Sci. Rep. 8, 5821 ( 10.1038/s41598-018-24162-z) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roy Khurana T, Sane SP. 2016. Airflow and optic flow mediate antennal positioning in flying honeybees. eLife 5, e14449 ( 10.7554/eLife.14449) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Srinivasan M, Zhang S, Lehrer M, Collett T. 1996. Honeybee navigation en route to the goal: visual flight control and odometry. J. Exp. Biol. 199, 237–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Greenlee MW, Heitger F. 1988. The functional role of contrast adaptation. Vis. Res. 28, 791–797. ( 10.1016/0042-6989(88)90026-0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boeddeker N, Hemmi JM. 2010. Visual gaze control during peering flight manoeuvres in honeybees. Proc. R. Soc. B 277, 1209–1217. ( 10.1098/rspb.2009.1928) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deer W, Pounds PEI. 2019. Lightweight whiskers for contact, pre-contact, and fluid velocity sensing. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 4, 1978–1984. ( 10.1109/LRA.2019.2899215) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baird E, Boeddeker N, Srinivasan MV. 2021. Data from: The effect of optic flow cues on honeybee flight control in wind Dryad Digital Repository. ( 10.5061/dryad.ffbg79csj) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Baird E, Boeddeker N, Srinivasan MV. 2021. Data from: The effect of optic flow cues on honeybee flight control in wind Dryad Digital Repository. ( 10.5061/dryad.ffbg79csj) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The full dataset (including individual flight data) used to generate the figures and perform the statistical analyses presented is available in the electronic supplementary material (file name: Data.xlsx) and from the Dryad Digital Repository: https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.ffbg79csj [27].