Abstract

Evidence suggests increased rates of suicidality in autism spectrum disorder (ASD), but the research has rarely used comparison samples and the role of emotion dysregulation has not been considered. We compared the prevalence of parent-reported suicidal ideation and considered the role of emotion dysregulation in 330 psychiatric inpatient youth with ASD, 1,167 community youth with ASD surveyed online, and 1,000 youth representative of the US census. The prevalence of suicidal ideation was three and five times higher in the community and inpatient ASD samples respectively compared to the general US sample. In the ASD groups, greater emotion dysregulation was associated with suicidal ideation. Implications include consideration of emotion regulation as a potential mechanism and treatment target for suicidality in ASD.

Keywords: suicidality, emotion regulation, ASD, autism, reactivity, dysphoria

Suicide is the second leading cause of death among U.S. youth and young adults (Stone et al., 2018), and suicide rates have increased 31% for male adolescents and 100% for female adolescents from 2007 to 2015 (Centers for Disease Control, 2017). Suicidal ideation is especially common among adolescents (Nock, Hwang, Sampson, & Kessler, 2010). In recent years, attention has been drawn to whether individuals with ASD experience heightened risk for suicidality, though studies with larger comparative samples and examinations of potential mechanisms and associated characteristics are lacking.

Rates of Suicidality in ASD

Extant research suggests that the prevalence of suicidality is heightened in ASD. In two reviews published in 2014, prevalence rates of suicidality ranged from 10–50% (Richa, Fahed, Khoury, & Mishara, 2014; Segers & Rawana, 2014). Several studies of adults with ASD have noted elevated rates of suicidal ideation, suicidal behaviors, or suicide attempts. Among a diagnostic clinic sample of adults who were recently diagnosed with ASD, 66% reported a history of suicidal ideation and 35% reported a suicide plan or suicide attempt (Cassidy et al., 2014). Hedley and colleagues (2017) found that 20% of adults with ASD who had completed an online survey on health and well-being had experienced suicidal ideation. Another online study found that 72% of ASD adults compared to 33% of non-ASD adults scored above a psychiatric cutoff of suicide risk on the Suicide Behavior Questionnaire-Revised (Cassidy, Bradley, Shaw, & Baron-Cohen, 2018).

Studies of inpatient records or adults with ASD in psychiatric hospital settings have also reported elevated rates of suicidal ideation (30.8%; Raja, Azzoni, & Frustaci, 2011), suicide attempts (3.8% and 7%, respectively; Kato et al., 2013; Raja et al., 2011), and completed suicides (7.7%; Raja et al., 2011). Kirby et al. (2019) conducted a record review of all deaths in the state of Utah, finding that deaths from suicide in those with ASD was 0.17%, significantly higher than for those without ASD. In a Swedish population study of premature mortality rates, individuals with ASD had at least double the risk (Hirvikoski et al., 2016). Overall, studies of suicide deaths and mortality in ASD are preliminary.

Likewise, the current evidence suggests that youth with ASD have increased risk for suicidality, including ideation and attempts, compared to non-ASD peers. In a sample of youth seen in an outpatient psychiatric diagnostic clinic, parents reported that almost 11% of youth had suicidal ideation and 7% had made a suicide attempt (Mayes, Gorman, Hillwig-Garcia, & Syed, 2013). In a study of youth with any intellectual or developmental disability attending appointments at a specialty developmental disorders pediatric clinic, 14% obtained scores above a clinical cutoff on a suicide screening measure (Lipkin, Rybczynski, Ryan, & Wilcox, 2019). Several clinical samples of youth with ASD have reported increased rates of suicidality: among youth seeking treatment for anxiety disorders, 11% of parents or self-reporters indicated suicidal ideation, suicide planning, or suicide attempts (Storch et al., 2013), while another survey of youth diagnosed at an ASD clinic noted that nearly one-third endorsed suicidal thoughts, statements, and behaviors (Demirkaya, Tutkunkardaş, & Mukaddes, 2016). A study of ASD youth who were hospitalized in specialty psychiatric inpatient units found suicidal ideation in 22% via parent report (Horowitz et al., 2018).

Emotion regulation impairment as a potential mechanism related to suicidal ideation in ASD

Although the emphasis of most ASD suicidality studies to date has been on prevalence, some of the aforementioned studies explored how demographic or other characteristics were associated with suicidal ideation. Thus far, studies have found that IQ (Hirvikoski et al., 2016; Mayes et al., 2013) and ASD symptom severity (Mayes et al., 2013) are unrelated to suicidality in clinically diagnosed ASD samples, but do suggest that risk may be greatest among females (e.g., Hedley, Uljarević, Wilmot, Richdale, & Dissanayake, 2018). Factors that have been linked to suicidality in ASD include non-suicidal self-injury and self-camouflaging of ASD behaviors (Cassidy et al., 2018). Limited social support (Cassidy et al., 2018; Hedley et al., 2017) and loneliness (Hedley et al., 2018) have been associated with greater suicidality as well.

It appears that some of the increased risk for suicidality is related to depression (e.g., Hedley et al., 2017, 2018). This is consistent with a study finding that psychiatric inpatients with ASD and suicidal ideation were more likely to also have co-occurring anxiety or mood disorders than psychiatric inpatients with ASD without suicidality (Horowitz et al., 2018). Research outside of ASD also suggests that depression is present in half of adolescents with suicidal ideation (Nock et al., 2010). However, a variety of mental health diagnoses are associated with suicidal behaviors in the general population, beyond mood and anxiety disorders (Nock et al., 2013). Thus far in ASD, other psychiatric diagnoses that have been linked with suicidality include substance abuse and personality disorders (Kirby, 2019; Kirby et al., 2019). Given the prevalence of suicidal ideation across diagnoses, it is imperative to identify transdiagnostic risk factors (Miller et al., 2018).

Atypical or impaired emotion regulation (ER) has been implicated across most psychiatric disorders (Aldao, Nolen-Hoeksema, & Schweizer, 2010) and it may be important to consider how it is related to suicidality. ER is commonly defined as the ability to modify one’s arousal and emotional state to promote adaptive behavior (Gross, 1998; Gross & Thompson, 2006). In our prior work, we have found that ER impairments in ASD are best captured along two related dimensions (Mazefsky, Yu, White, Siegel, & Pilkonis, 2018). These include intense, rapidly escalating and poorly regulated emotion characterized by anger and irritability (Reactivity) and low positive affect and motivation (Dysphoria). There is now a sizeable body of research suggesting that ER is often impaired in ASD and associated with a range of mental health problems (see Cai, Richdale, Uljarevic, Dissanayake, & Samson, 2018, for review), though the association between ER and suicidality has yet to be explored in ASD. Outside of ASD, some have argued that intense and intolerable negative emotion resulting from poor ER directly increases suicidal behavior. For example, the Cry of Pain (CoP) model of suicidality posits that suicidality is a response to negative emotion that is perceived as inescapable (Williams & Williams, 1997), which can also be described as the experience of feeling emotions that cannot be effectively regulated.

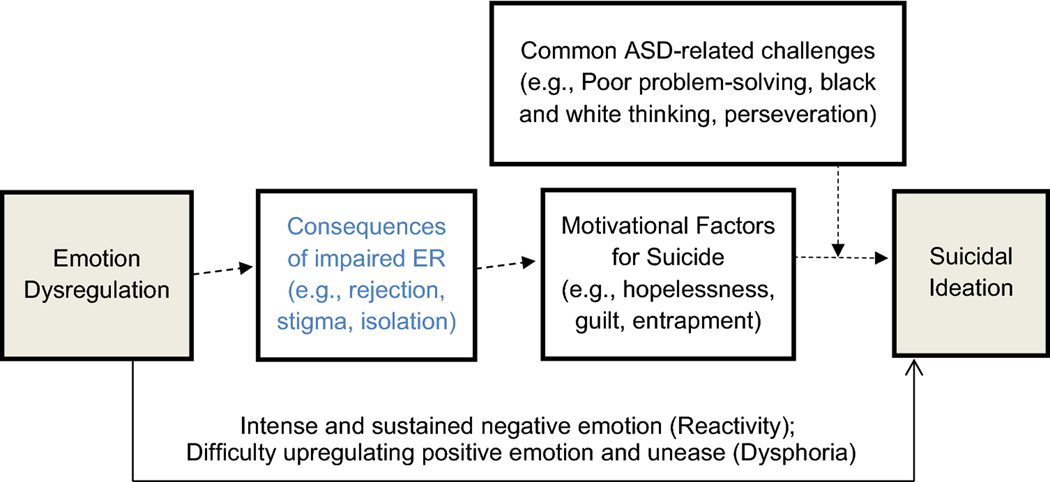

Other prominent models of suicidality, such as Joiner’s Interpersonal Theory of Suicide (Joiner, 2005) and O’Connor’s Integrated Motivational-Volitional Theory (O’Connor, 2011) emphasize the multifactorial nature of increased vulnerability to experience suicidal thoughts. These more complex models include risk and protective factors for suicide (O’Connor & Nock, 2014), including many personality and cognitive characteristics that we would argue are also related to poor ER. For example, the experience of rapid, sustained, strong negative emotion (reactivity) and difficulty upregulating positive emotion (dysphoria) may, in turn, increase hopelessness, defeat, or feelings of entrapment which have been identified as suicidality risk factors. Other risk factors such as increased guilt or feelings of being a burden may result from the aggression, angry tirades, or the feeling of being a “downer” that others do not want to be around, could all result from poor ER. Reactivity may even further diminish social support options, which are a protective factor for suicidality (Kleiman & Liu, 2013), and increase social isolation (a risk factor) due to the negative impact of emotional outbursts on relationships. It is possible that the association between impaired ER and these suicidality risk factors is magnified in the context of common ASD-related challenges such as poor problem-solving, difficulty asking for help, and lack of external support (Lai, Rhee, & Nicolas, 2017). Thus, although it is likely that ER is part of a complex set of interrelated factors leading to suicidal ideation, it is conceivable that poor ER may be a shared process underlying motivational risk factors for suicide (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Model of how impaired emotion regulation may lead to suicidal ideation in ASD.

The examples are illustrative, not all-inclusive. The model is meant to demonstrate how impaired ER may result in suicidal ideation, though there are likely bidirectional effects not pictured. This study will test the direct effect of emotion dysregulation on suicidal ideation (shaded boxes and solid arrow).

The current study

In sum, there is accumulating evidence suggesting that individuals with ASD may experience high rates of suicidal ideation and behaviors, but most studies have reported on modestly sized samples and in the context of published rates outside of ASD. Further, ASD research is in the very early stages of identifying contributors to suicide risk in ASD. ER impairment may be a particularly important construct to consider in relation to suicidality. ER could offer a potential explanation for the elevated rates of suicidality in ASD given that impaired ER is known to be common in ASD. Furthermore, it may offer a parsimonious and efficient treatment target given its theoretical link to several well-established motivating factors for suicide from the non-ASD literature. An important first step would be to determine whether ER is in fact associated with suicidality in ASD.

Therefore, the current study had two main aims: 1) to compare the prevalence of parent-reported suicidal ideation and behaviors in youth across three large samples (a community-based sample of youth with ASD surveyed online, a sample of youth with ASD admitted for inpatient psychiatric hospitalization, and a US census-matched general youth sample), and 2) to investigate whether ER impairment is associated with suicidal ideation and behaviors after controlling for demographic factors and ASD symptom severity. We hypothesized that parent-reported suicidal ideation and behaviors would be significantly higher among youth with ASD and highest in the inpatient ASD sample. We also expected that ER impairment would significantly predict the presence of suicidal ideation after controlling for demographic variables and ASD symptom severity across all groups.

Methods

Participants

Participants for this study were drawn from three parent-report youth samples for secondary analysis. These three samples were collected for development of the Emotion Dysregulation Inventory (R01 HD079512 PI: Mazefsky). Demographic characteristics are presented in Table 1. The samples were not intended to be representative of the population that they were sampled from rather than matched to each other on demographics or other characteristics (such as gender or intellectual ability). However, the age range was restricted across samples to children and adolescents ages 6 to 17 to be consistent with the normative data and validation samples for the primary measures.

Table 1.

Demographic variables and descriptive statistics

| YouGov (U.S. Census) (n=1,000) |

IAN (ASD Community online) (n= 1,169) |

AIC (ASD Inpatient specialty psychiatric) (n=330) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | |

| Mean Age (SD) | 12.05 (3.55) | 12.04 (3.19) | 13.19 (3.37) |

| Male | 50.6% (506) | 79.8% (933) | 78.8% (260) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 17.5% (175) | 9.3% (109) | 8.2% (27) |

| Race | |||

| White | 65.1% (651) | 91.5% (1070) | 90.3% (298) |

| Black | 14.5% (145) | 6.3% (74) | 9.1% (30) |

| Asian | 4.3% (43) | 2.0% (23) | 4.2% (14) |

| Native American | 3.8% (38) | 2.5% (29) | 2.4% (8) |

| Other | 2.2% (22) | 3.9% (46) | 1.2% (4) |

| Missing race | 0 | 0.4% (5) | 1.2% (4) |

| ID (IQ<70) | 1.3% (13) | 54.0% (631) | 44.8% (148) |

| Minimally verbal* | 3.4% (34) | 43.6% (510) | 52.7% (174) |

Minimally verbal was defined as either receiving module 1 or 2 of the ADOS-2 (AIC) or by parent report

Inpatient Specialty Psychiatric ASD sample (Autism Inpatient Collection)

The Autism Inpatient Collection (AIC) is a six-site study of children, adolescents, and young adults admitted to specialized inpatient psychiatric units for youth with ASD and other developmental disorders. The full methods of the AIC have been published previously (Siegel et al., 2015). The AIC includes participants ages 4–20 years old, although for the purposes of this study all participants younger than 6 and older than 18 were excluded (N=58) to match the other two samples. Only AIC subjects that completed the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL: Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001; see below) were included. Participants above the clinical cutoff (with a score of ≥ 12 on the Social Communication Score-Lifetime Version (SCQ; Rutter, Bailey, & Lord, 2003)), or with high suspicion of ASD from the inpatient clinical treatment team were eligible for enrollment. Inclusion in the AIC dataset required confirmation of ASD diagnosis by research-reliable administration of the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule-2 (ADOS-2; Lord et al., 2012). Exclusion criteria included the lack of availability of a caregiver proficient in English, or prisoner status of the individual with ASD. The AIC sample was used in this study to provide a subgroup with elevated ER impairment.

Community Online ASD sample (Interactive Autism Network)

The Interactive Autism Network (IAN) is an online registry of individuals with parent-reported professional ASD diagnoses in the United States that was developed to support internet-based research studies and aid in recruitment. Participants in IAN’s registry were invited to complete this study if they had a SCQ score of 12 or above and were between the ages of 6–17 years old. The validity of parent-reported professional diagnosis of ASD has been verified in a study using medical records in a subset of participants in the full IAN registry (Daniels et al., 2012). Community professional diagnosis of ASD has also been validated in a subset of IAN participants through the use of structured diagnostic tests such as the ADOS and clinician opinion (Lee et al., 2010). Together, these findings provide confidence in the validity of parent-reported ASD diagnoses in IAN registry participants. Invitations to participate in this study were sent to 11,648 registrants; 9,926 did not respond, 1,642 expressed interest, and 1,323 participated. Of the 1,323 participants, 1,169 (88.36%) completed all of the measures in the current study and were thus included. The IAN sample provided a self-selected sample of parents of youth with ASD, which was intended to assess ER impairment in a non-clinical setting.

U.S. census-matched general population sample (YouGov).

YouGov is a web-based global public opinion and data polling company that has the capacity to collect data from individuals anywhere in the United States. YouGov utilized sample matching to collect data from 1,000 caregivers of 6–17-year-old youths in a sample representative of the 2016 American Community Survey. YouGov staff interviewed 1,055 respondents, who were then reduced to a sample of 1,000 to produce the final dataset. Individuals used for data collection are identified using specific requirements (age, race, gender, etc.) and then by simple random sampling. The final set of completed interviews are matched to the target frame, using a weighted Euclidean distances metric. The sample represents the US population of adults with related children in the household, ages 6 to 17. The matched cases were weighted to the sampling frame using propensity scores. The propensity score function included age, gender, race/ethnicity, years of education, and region. The propensity scores were grouped into deciles of the estimated propensity score in the frame and post-stratified according to these deciles. The weights were then post-stratified on a four-way stratification of gender, age (4-categories), race (4-categories), and education (4-categories), to produce the final weight. The matched cases and the frame were combined and a logistic regression was estimated for inclusion in the frame. The YouGov sample provides a US population-representative group of parents of youth that is not clinically-obtained.

Measures

Demographics.

Parents completed a demographic questionnaire regarding the child including race, ethnicity, and gender. In addition, the questionnaire asked for information regarding their child’s verbal ability and IQ.

Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001).

The CBCL is part of the Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessments test series, which is comprised of a family of questionnaires used for assessment of behavioral, social, and emotional problems across the lifespan. The CBCL is a parent-report questionnaire for youth age 6–18 years old. Items are rated based on the past six months on a three-point Likert scale as either 0= Not True, 1= Somewhat or Sometimes True, or 2= Very True or Often True. The CBCL has been widely used and is considered well-validated, including in ASD samples (e.g., Stratis & Lecavalier, 2017). All three of the samples used for this study completed the full CBCL. For this study, we used item 91 (‘Talks about killing self’) as a measure of suicidal ideation and item 18 (‘Deliberately harms self or attempts suicide’) as a measure of suicidal behavior and attempts. Items were collapsed into a binary response of not present (answer of 0) or present (answer of 1 or 2) for analyses.

Emotion Dysregulation Inventory (EDI; Mazefsky, Day, et al., 2018; Mazefsky, Yu, et al., 2018; Mazefsky, Yu, & Pilkonis, In Press).

The EDI is a validated, change sensitive, 30-item caregiver report measure of emotion regulation impairment for individuals who are at least 6 years of age. The EDI was developed using item response theory (IRT) analysis and none of the final items had evidence of differential item functioning (e.g., psychometric biases) by gender, age, intellectual ability, and verbal ability, making it suitable for use across heterogeneous populations. Items on the EDI measure how much of a problem behaviors have been in the past 7 days. The scale used is Not at all = 0, Mild = 1, Moderate = 2, Severe = 3, or Very Severe = 4. The EDI is comprised of two scales: Reactivity and Dysphoria. Scores can be generated based on: (1) The full 24-item EDI Reactivity Item Bank, (2) a 7-item EDI Reactivity Index Short Form, and (3) 6-item Dysphoria Index. Full EDI Reactivity Scale, EDI Reactivity Index Short Form, and EDI Dysphoria Index raw scores can be converted into t-scores or theta scores based on a sample of 1,755 individuals with ASD (Mazefsky, Yu, et al., 2018) or based on a sample of 1000 youth matched to the US census as general population norms (Mazefsky, Yu, & Pilkonis, In Press). For the purposes of this study, theta scores were generated for the Reactivity Short Form and Dysphoria based on the autism conversions. While the autism norms were used in this study, the validity and reliability of the EDI has been supported in neurotypical samples (Mazefsky et al., In Press).

Procedure

For the inpatient ASD sample, data were collected following consent/assent from a family member/guardian. Caregivers who consented within ten days of admission were enrolled and completed a questionnaire battery while their child was in the hospital. For the Community ASD sample and General US census sample, parents completed the surveys online.

Analysis

To compare response rates for the CBCL suicidal ideation and suicidal behavior items across the three groups, chi square analyses were run. To determine the impact of ER impairment on parent-reported suicidal ideation, a logistic regression was run with a binary-coded CBCL item #91 (did or did not express suicidal ideation) as the outcome variable. Covariates were entered in steps: demographics (age, gender, race, and ethnicity) as step one, ASD variables (SCQ total score, sample source) as step two, and ER impairment (EDI-Reactivity) as the final step. The regression was conducted a second time, with the only difference being that the EDI-Dysphoria score was the final variable entered. To explore whether emotion regulation was differentially associated with suicidal ideation based on sample source, interaction terms were created and included in each regression model for EDI score by group using the PROCESS macro (Hayes, 2015). To assess suicidal behavior and prior attempts, the same two models were run with CBCL item #18 as the outcome variable.

In supplemental analyses, the four logistic regression analyses were also re-run with only verbally fluent participants. All three samples contained participants who were identified as minimally verbal based on parent report, but the suicidal ideation variable (CBCL item #91) requires verbal speech, and self-harm (as in item #18) in individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities is often categorized as a type of repetitive behavior (Maddox, Trubanova, & White, 2016), or serving another non-suicidal function. Thus, we wished to determine if analyses with only verbally fluent participants would yield the same conclusions.

Results

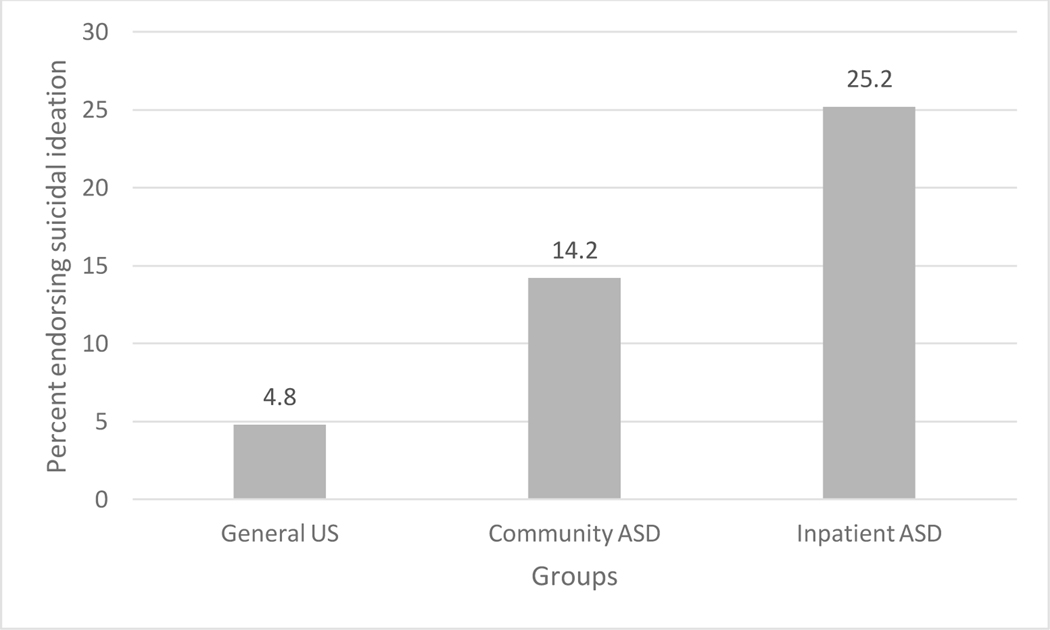

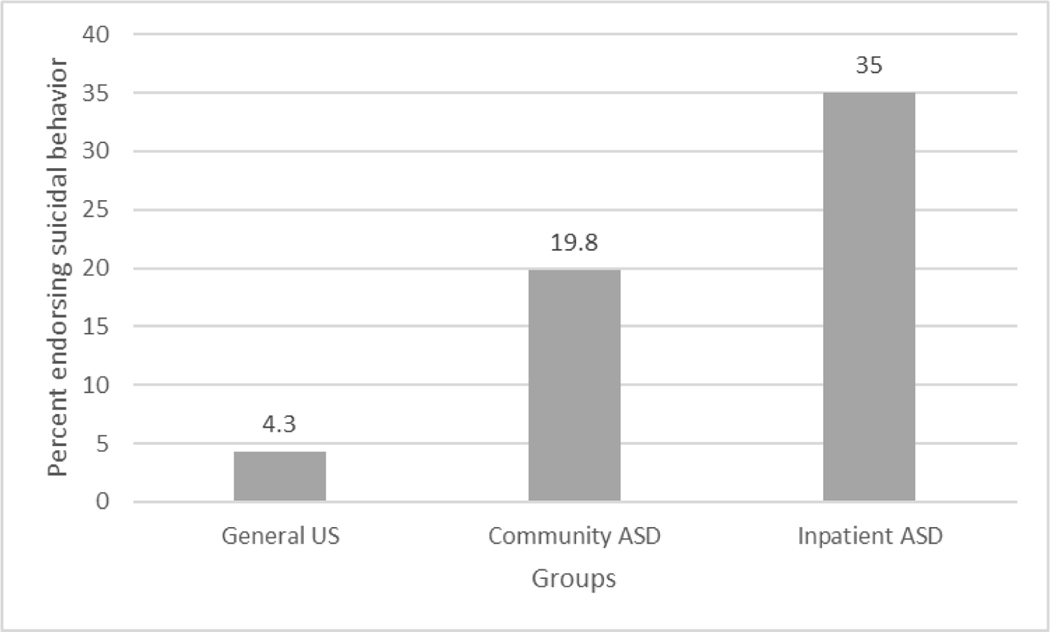

As hypothesized, all three groups significantly differed in the percent of the sample that endorsed parent-reported suicidal ideation, with the general US sample the lowest, the community ASD sample next, and the inpatient ASD sample highest, (χ2(2) = 135.81; p< .001). While nearly 5% of the general US youth sample’s parents responded that their child had voiced suicidal ideation in the past six months, parents of the community ASD group were three times more likely, and parents of the inpatient ASD group were five times more likely to endorse the item (See Figure 2). This pattern was similar for parent-reported suicidal behaviors and attempts (χ2(2) = 456.61; p< .001), with 4.3% of parents in the general US sample reporting that their child engaged in self-harm or attempted suicide in the past six months. Parents of the community ASD group were nearly five times more likely to endorse the item, and parents of the inpatient ASD group were nearly nine times more likely to endorse the item (See Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Percentage of Participants in Each Sample Endorsing Suicidal Ideation (CBCL item #91)

Figure 3.

Percentage of Participants in Each Sample Endorsing Suicidal Behavior (CBCL item #18)

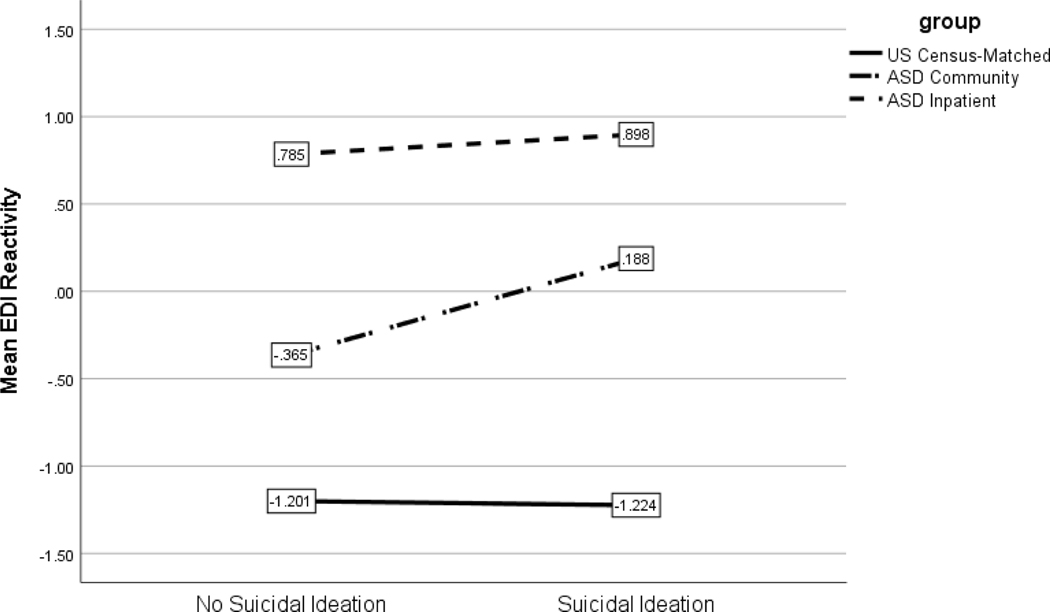

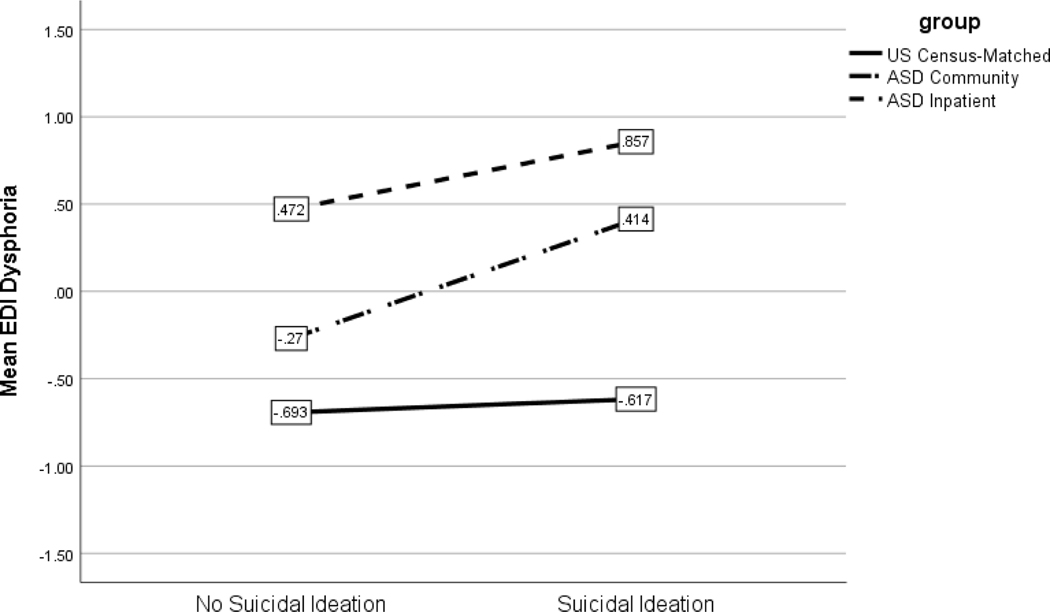

In the model to predict the presence of suicidal ideation that included EDI-R, older age (B= .07; p=.001), community ASD group (B= −1.86; p= .002), and inpatient ASD group (B= −.82; p<.001) were significant predictors. Although there was not a main effect of EDI-R scores, there was a significant interaction between EDI-R and community ASD group membership (p< .001) (Figure 4), such that higher EDI-R scores were significantly associated with parent-reported suicidality in the community ASD group.

Figure 4.

EDI Reactivity by Suicidal Ideation across Groups

When the EDI-D was used in the model, male gender (B= .45, p=.02), community ASD group (B= −2.17, p<.001), and inpatient ASD group (B= −.86, p<.001) were significant predictors of parent report of child’s suicidal ideation. Although there was not a significant main effect for EDI-D scores, there was an interaction between the EDI-D and both the community ASD sample (p=.001) and inpatient ASD sample (p=.009) (Figure 5), such that higher EDI-D scores were significantly associated with parent reports of suicidality in both ASD groups.

Figure 5.

EDI Dysphoria by Suicidal Ideation across Groups

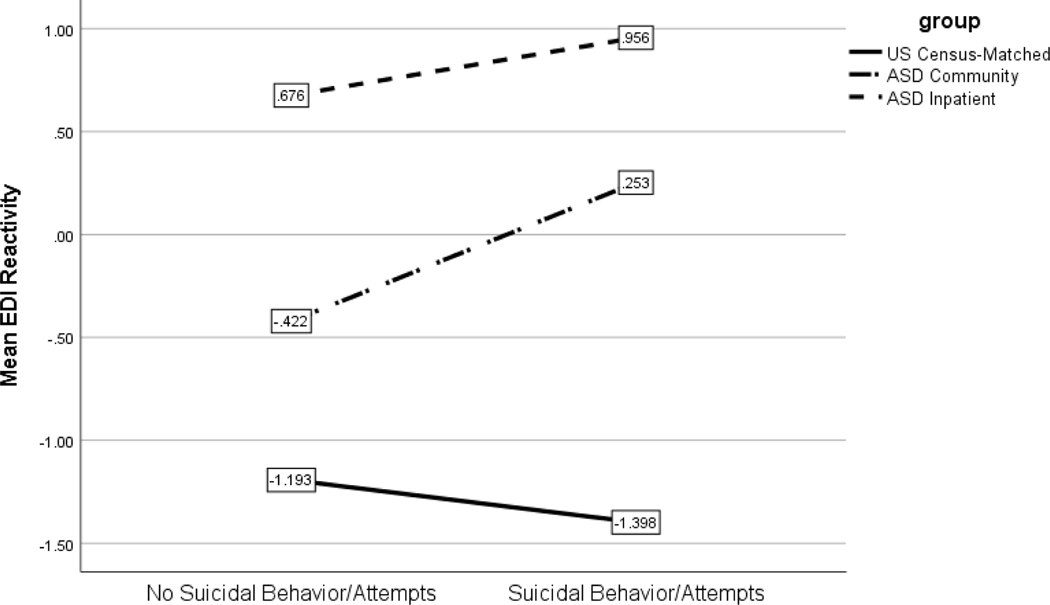

In the model to predict the presence of suicidal behaviors or attempts that included EDI-R, higher SCQ scores (B= .06; p< .001), community ASD group (B= −1.20; p< .001), inpatient ASD group (B= −.97; p< .001), and higher EDI-R (B= .59; p<.001) were significant predictors. EDI-R was not a significant predictor (B= −.24; p= .30). There were significant interactions between EDI-R and community ASD group membership (p< .001) and EDI-R and inpatient ASD group membership (p= .04), such that higher EDI-R scores were significantly associated with parental reports of suicidality in both the community and inpatient ASD groups.

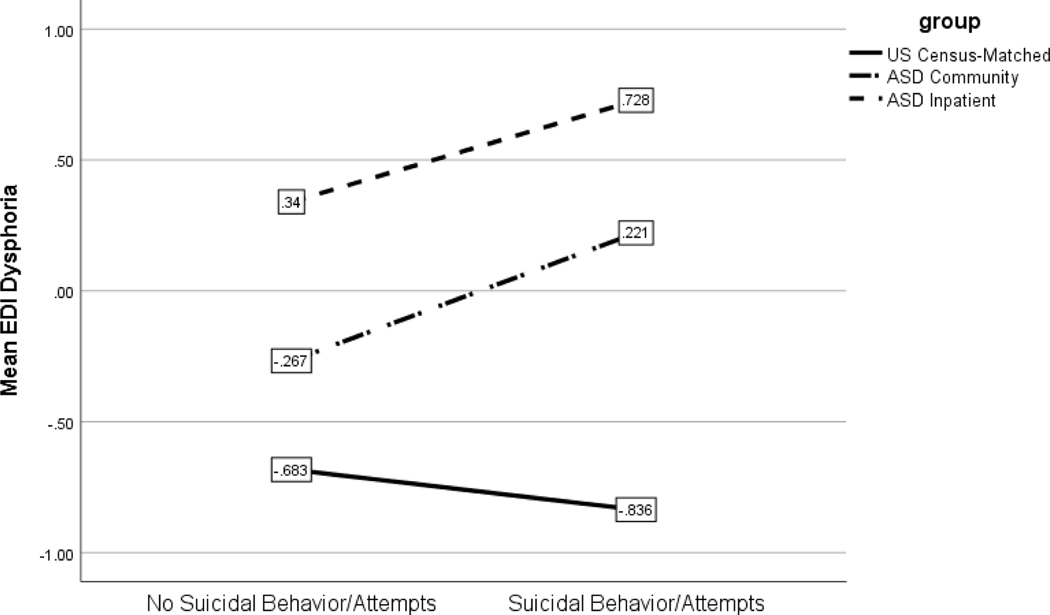

When the EDI-D was used in the model, higher SCQ scores (B= .06, p<.001), community ASD group (B= −1.88, p<.001), and inpatient ASD group (B= −1.26, p<.001) were significant predictors of suicidal ideation. Although there was not a significant main effect for EDI-D scores, there was an interaction between the EDI-D and both the community ASD sample (p=.003) and inpatient ASD sample (p=.009), such that higher EDI-D scores were significantly associated with reports of suicidality in both ASD groups.

Supplemental analyses with only verbally fluent participants yielded mostly similar results (See Supplementary Materials). The same main effects were observed in the verbal only sample when predicting parent-reported suicidal ideation, with the addition of main effects for male gender (being more likely to have parent-reported ideation) and higher EDI-R scores. The same interaction effect of Community ASD group status and higher EDI-R was present in the verbal only sample. When using the EDI-D, the same pattern of results was found in the verbal only sample as was reported in the full sample.

For analyses predicting suicidal behaviors and prior attempts based on parent report, the same main effects (higher SCQ total scores, Community ASD group status, Inpatient ASD group status, and higher EDI-R scores) were found, as well a main effect for identifying as Hispanic/Latino (being more likely to have parent-reported suicidal behaviors/prior attempts). Additionally, the interactions between both ASD groups and higher EDI-R in predicting parent report of suicidal behaviors remained in the verbal only group. When using the EDI-D, the same pattern of results was found in the verbal only group, with the exception of adding identifying as Hispanic/Latino as a main effect.

Discussion

This study aimed to determine whether parental report of suicidal ideation and behaviors are elevated in youth ASD samples by comparing their prevalence across three large groups, including a sample representative of the general US population. As predicted, parents of youth with ASD were significantly more likely to report suicidality in their child than parents of general US youth. Youth with ASD who were admitted to inpatient psychiatric settings had the highest rates of parent-reported suicidal ideation (25%), but youth with ASD in a community-based sample were also three times more likely to have parent-reported suicidal ideation (14%) compared to a general US sample (4%). Similarly, parents of youth with ASD admitted to inpatient psychiatric settings reported the highest rates of suicidal behaviors and suicide attempts (35%), while parents of youth with ASD in a community-based sample were almost five times more likely to endorse suicidal behavior (19.8%) than those in a general US sample (4.3%). These results with the largest comparative sample to date indicate that by parent report youth with ASD experience suicidality at significantly higher rates than a general US sample. This finding extends prior research that suggested elevated rates of suicidal ideation in ASD (Lai et al., 2017; Richa et al., 2014; Segers & Rawana, 2014). The general community ASD sample rate of parent-reported suicidal ideation in this study was quite similar to previously reported rates in other studies of youth with ASD (Lipkin et al, 2019, Mayes et al, 2013, Storch et al, 2013), while the rates of suicidal behavior/attempts are lower than those reported in adult ASD samples (Cassidy et al., 2014).

Results from this study also implicate the role of ER impairment in suicidality in ASD. After controlling for demographics and ASD symptom severity, increased ER impairment was significantly associated with parent-reported suicidal ideation and behavior in the ASD groups. In the community ASD group, both dimensions of ER impairment (reactivity and dysphoria) were related to a higher likelihood of reported suicidal ideation. Higher reactivity scores were not associated with suicidal ideation in the inpatient ASD group, however. This likely reflects the fact that the inpatient ASD group as a whole had high emotional reactivity, regardless of suicidality. This finding may not be surprising given that reasons for admission to specialized autism inpatient units generally include severe behavioral problems (e.g., aggression, self-injurious behavior) (Siegel et al., 2012) that are also associated with high emotional reactivity (Goodwin, Mazefsky, Ioannidis, Erdogmus, & Siegel, 2019). In contrast, elevated dysphoria was predictive of suicidal ideation in both ASD groups, suggesting that it may be particularly important to consider how general unease, low motivation, and poor upregulation of positive emotion may play a role in suicidality in ASD. In general there has been limited research on the regulation of positive emotion in ASD (Cai, Richdale, Uljarevic, et al., 2018; Samson & Antonelli, 2013; Samson, Huber, & Ruch, 2013), so this may be an important area for further study.

Interestingly, the association between ER impairment (reactivity and dysphoria) and both suicidal ideation and suicidal behaviors/attempts were unique to the ASD groups; neither reactivity nor dysphoria were associated with suicidality in the general US sample. It is possible that parents of youth with ASD are more attuned to notice signs of suicidality or distress in their children based on the availability of parent-mediated interventions for young children with ASD that train parents to observe and modify behaviors. It is also possible that the lack of association between ER and suicidality in the general population sample was due to restricted rage, including a low rate of reported suicidal ideation and behaviors/attempts as well fewer participants with severe emotion dysregulation. It will be important to follow up with additional studies comparing ASD youth to other samples with high rates of suicidality. It is possible that a similarly strong association between ER impairment and suicidality may be observed in other clinical populations, given prior research suggesting that impaired ER plays a role in suicidality outside of ASD (Davey, Halberstadt, Bell, & Collings, 2018; Hatkevich, Penner, & Sharp, 2019; Miller et al., 2018; Van Eck et al., 2015).

The association between ASD symptom severity and suicidality differed in important ways based on the item used to assess suicidality. Higher SCQ scores were associated with a greater likelihood of endorsing the item measuring suicidal behaviors and attempts. Because this item may tap self-injurious behavior that does not have suicidal intent, this finding could be explained by the heightened levels of self-injurious behaviors observed in youth with more severe ASD symptoms (Duerden et al., 2012). However, ASD symptom severity was unrelated to the item measuring suicidal ideation in this study. This contrasts prior studies that found that ASD symptom severity was related to increased suicide risk (Cassidy et al., 2018; Mayes et al., 2013). An important distinction between this study and prior research is our inclusion of emotion regulation impairment in the same model as ASD symptom severity. It is possible that the much higher rates of emotion dysregulation in ASD (Conner et al., in preparation; Joshi et al., 2018) are driving prior findings suggesting that ASD symptom severity increases suicide risk, rather than the ASD symptoms per se.

It is possible that specific unmeasured ASD-related characteristics play a role, aside from core ASD symptom severity. For example, Cassidy et al. (2018) found that efforts to camouflage ASD-related challenges increased suicide risk. Others have suggested executive function impairment, which is common in ASD, could underlie the increased prevalence of suicidal ideation in ASD (Lai et al., 2017). There are many other potential ASD-related contributors to consider as well (e.g., problem-solving deficits, perseveration, coping with sensory and environmental stressors, etc.). The heightened reactivity and distress seen in ASD may have an indirect effect on suicidality, rather than a direct main effect, that elicits cascading effects in social difficulties and mental health. It is further possible that suicidality in ASD may stem from different risk and mechanistic factors than what is seen in the typically developing population (Cassidy et al., 2018; Lai et al., 2017). It will be important for future studies to include measures of both ER and other common ASD characteristics or experiences in order to develop a more complete understanding of how having ASD leads to a higher likelihood of suicidal ideation than the general population.

Some demographic factors also emerged as significantly associated with suicidal ideation. Being male was a significant predictor of suicidal ideation, which was observed in another study of youth with ASD and suicidality (Mayes et al., 2013), but is contrary to research on adults with ASD that found females were more likely to report suicidality (Cassidy et al., 2018) as well as literature regarding suicidality in the general population (Nock et al., 2010). Older age was associated with suicidality in both models, which is consistent with prior research in typically developing samples showing increased suicidality in adolescence (Nock & Mendes, 2008). Studies of self-reported suicidal ideation by adults with ASD have reported even higher rates than we found (e.g., Cassidy et al, 2018), so it will be important to determine whether risk continues to increase across the life course and varies by reporter. Longitudinal studies of suicidality and ER impairment are also needed in order to determine whether ER impairment may function as a mechanism underlying changes in suicidality prevalence over the developmental course in ASD.

The main findings of this study did not differ in supplementary analyses that only included parents of verbally fluent youth. This is contrary to expectations that parents of those who are minimally verbal would endorse verbal suicidal ideation less frequently. It will be important for future research to develop a better understanding of how parents perceive and interpret suicidal ideation in their minimally verbal children. Findings were also generally consistent in only fluently verbal youth with regard to suicidal behaviors and attempts. This suggests a role for emotion regulation impairments in self-injurious behaviors and suicide attempts, regardless of verbal ability. Traditionally, self-injury in ASD has been conceptualized as a repetitive behavior or serving functions other a sign of suicidality; more recent research has questioned whether suicidal self-injury could be under-recognized, especially in individuals who are less verbally fluent (Cassidy et al., 2018). It is important for future research to investigate how to best categorize the functions of self-injurious behavior in individuals with ASD, as well as to identify a validated means to quantify suicidality in individuals who are not fluently verbal.

Limitations

The most substantial limitations of the current study concern measurement. The current study relied entirely upon parent report of youth symptoms. Parent-report of suicidality is likely to underestimate their child’s internal emotional states and thoughts. However, other studies in ASD have posited that self-report of internal states may be particularly difficult for individuals with ASD, as difficulties labeling emotions and internal states are common among in ASD (Berthoz & Hill, 2005; Bird & Cook, 2013). Because different sources of information can lead to different conclusions (Blakeley-Smith, Reaven, Ridge, & Hepburn, 2012; Lerner, Calhoun, Mikami, & De Los Reyes, 2012; Mazefsky, Kao, & Oswald, 2011), future research should include multiple modalities of assessment, including self-report of suicidality.

Parent-report in ASD may be further complicated by ASD symptoms. Both items from the CBCL lack specificity and could be interpreted differently than intended, with possible sample-specific effects. Using the item ‘Talks about killing self,’ to define the presence or absence of suicidal ideation suggests reliance on information conveyed verbally, though it is possible that parents of minimally verbal youth were basing their responses on other observations. Nonetheless, utilizing this item likely shifts the percentage of positive responses disproportionately toward the more verbal ASD population, and therefore limits generalizability of our results for the less verbal ASD population. Similarly, the item ‘Deliberately harms self or attempts suicide’ may also be interpreted by parents as self-injurious behavior that is relatively common in ASD and may be due to characteristics seen in ASD (e.g., repetitive behaviors or a response to hypersensitivity to environmental input) that may not have suicidal intent. Overall, parents of youth who are minimally verbal may be particularly challenged when asked to interpret the intent of their children’s behaviors or internal emotional states, and when asked to respond to items that are based on a child’s speech. It is also possible that repetitive speech and making suicidal comments or behaviors without actual suicidal intent may be more likely in youth on the autism spectrum (Cassidy et al., 2018). Determining and measuring the intent of youth who engage in self-injury, particularly those who are minimally verbal, is difficult and alternate methods may be needed to measure suicidality in those on the autism spectrum (Cassidy et al., 2018). Thus, future research should incorporate multimethod measurement of ER impairment and suicidality in ASD, particularly for those who are minimally verbal.

Although the large sample sizes in this study and use of a consistent measure across samples is a strength, only single items of suicidal ideation and behaviors/attempts were available. Relying on only two items to measure suicidality is a considerable weakness given these potential differences in reporting. Future research should use more in-depth suicidality measures that are validated in the typically developing population. It will also be important to focus on developing measures that specifically assess suicidality in ASD (Cassidy et al., 2018; Lai et al., 2017) given that individuals with ASD may also present with different suicidal behaviors (Cassidy, Bradley, Bowen, Wigham, & Rodgers, 2018; Kato et al., 2013; Weiner, Flin, Causin, Weibel, & Bertschy, 2019). Importantly, this study focused on suicidal ideation and behaviors, but did not assess suicide attempts separately. It is likely that other factors may moderate risk for attempts in those who have suicidal thoughts. Indeed, not all of those with ER impairment become suicidal, and not all of those with suicidal thoughts engage in suicidal behaviors or make an attempt. This study was the first step to determine whether impaired ER is associated with suicidal ideation, and future work should follow up on its foundation by exploring other factors that may exacerbate the association as well as characteristics or circumstances that are likely to lead to an attempt (e.g., capability factors; O’Connor, 2011).

Despite the limitations of using secondary data sources in this study, these datasets provided an opportunity to assess rates of suicidality and the relationship of suicidality and ER impairment in a large sample and offer important clinical implications. The finding that impaired ER is associated with suicidality in ASD adds to the burgeoning evidence that impaired ER is associated with a range of psychiatric symptoms and problem behaviors in ASD (Cai, Richdale, Foley, Trollor, & Uljarević, 2018; Khor, Melvin, Reid, & Gray, 2014; Mazefsky, Borue, Day, & Minshew, 2014; Samson, Hardan, Lee, Phillips, & Gross, 2015; Weiss, 2014). Therefore, although ER impairment is unlikely to be a unique predictor of suicidality, improving ER may have widespread effects on suicidality and general mental health. ER is frequently a mechanistic target of transdiagnostic treatments outside of ASD (Loevaas et al., 2019; Volkaert, Wante, Vervoort, & Braet, 2018). Although recent studies suggest that ER is also modifiable within ASD (Conner et al., 2019; Shaffer et al., 2019; Weiss et al., 2018), suicidality has not been considered as a treatment target or measured outcome in ER-focused intervention work to date. Understanding how ER-focused treatment may prevent or decrease suicidal ideation is an important direction for future research. Given the link between dysphoria and suicidal ideation in both ASD samples, it may also be worthwhile to consider how interventions focused on savoring positive emotion (McMakin, Siegle, & Shirk, 2011) and increasing behavioral activation (Gudmundsen et al., 2016) impact suicidality in ASD.

It is also important to note that the community ASD and inpatient ASD groups produced relatively similar findings, with both samples demonstrating significant associations between ER impairment and suicidality. This finding suggests that screening youth with ASD for ER impairment and suicidality should be considered in outpatient and community settings, not just in inpatient settings. Further, unlike neurotypical samples, individuals are typically admitted to specialty inpatient psychiatric units for youth with ASD due to externalizing symptoms, rather than internalizing concerns such as suicidality (Siegel et al., 2012). Our findings suggest that dysphoria in particular is associated with an increased likelihood of parent-reported suicidal ideation and behavior in these settings. It may be important to evaluate for the presence of dysphoria in those admitted for hospitalization due to externalizing behaviors, as well as to understand how suicidality, externalizing behaviors, and ER are related to one another.

In sum, this study provided compelling evidence of elevated rates of parent-reported suicidal ideation in ASD through a comparison of large ASD samples and a general sample representative of the US census. Although future studies are needed with more thorough and validated measures of suicidality and in population-level samples, the results highlight the importance of continued suicide research in ASD. Further, the findings suggest that ER impairment is associated with suicidal ideation in ASD. Future studies should further evaluate the processes that lead to this association, via concurrent consideration of other common ASD characteristics and longitudinal studies. Interventions that focus on reducing ER impairment should also be examined as a potential means to reduce suicidality in this vulnerable and at-risk population.

Supplementary Material

Figure 6.

EDI Reactivity by Suicidal Behaviors/Attempts across Groups

Figure 7.

EDI Dysphoria by Suicidal Behaviors/Attempts across Groups

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics

| YouGov (US Census) (n=1,000) |

IAN (Community online) (n= 1,169) |

AIC (ASD Inpatient specialty psychiatric (n=330) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M(SD) | % (n) | M(SD) | % (n) | M(SD) | % (n) | |

| SCQ total score | 6.82 (5.83) | 23.29 (6.04) | 24.48 (5.98) | |||

| EDI Reactivity Short Form Theta Score | −1.20 (.79) | −.29 (.85) | .86 (.81) | |||

| EDI Dysphoria Theta Score | −.69 (.78) | −.17 (.88) | .61 (.86) | |||

| CBCL 91 (suicidal ideation) | 4.8% (48) | 14.2% (166) | 25.2% (83) | |||

| Very True or Often True | 0.5% (5) | 2.4% (28) | 7.9% (26) | |||

| Somewhat or Sometimes True | 4.3% (43) | 11.8% (138) | 17.3% (57) | |||

| CBCL 18 (suicidal behaviors and past attempt) | 4.3% (43) | 19.8% (231) | 35% (117) | |||

| Very True or Often True | 1.1% (11) | 5% (58) | 21.6% (72) | |||

| Somewhat or Sometimes True | 3.2% (32) | 14.8% (173) | 56.6% (189) | |||

Table 3.

Logistic regression results predicting suicidal ideation based on ER Impairment, demographics, and ASD symptom severity

| Scale | B | Wald χ2 | p | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suicidality | ||||||

| Step 1. Demographics | age | .07 | 7.68 | .001 | .08 | .03–.13 |

| gender | .37 | 3.87 | .056 | −.37 | −.74–.09 | |

| race | .28 | 1.15 | .173 | −.36 | −.88–.16 | |

| ethnicity | .18 | .31 | .687 | −.13 | −.77–.51 | |

| Step 2. ASD symptom severity | SCQ total | .02 | 3.01 | .135 | .02 | −.01–.05 |

| Group status (community ASD) | −1.86 | 26.39 | .002 | 1.18 | .45–1.91 | |

| Group status (inpatient ASD) | −.82 | 11.52 | <.001 | 2.94 | 2.06–3.81 | |

| Step 3. ER impairment | EDI-Reactivity | .50 | 7.21 | .223 | −.31 | −.81–.19 |

| Step 4. Interaction | EDI-R × Group (community ASD) | -- | 4.79 | <.001 | 1.41 | .83–1.99 |

| EDI-R × Group (inpatient ASD) | -- | 1.61 | .108 | .50 | −.11–1.12 | |

| Step 3. ER impairment | EDI-Dysphoria | .31 | 2.81 | .935 | −.02 | −.51–.47 |

| Step 4. Interaction | EDI-D × Group (Community ASD) | -- | 3.28 | .001 | .91 | .37–1.46 |

| EDI-D × Group (Inpatient ASD) | -- | 2.61 | .009 | .85 | .21–1.50 | |

Table 4.

Logistic regression results predicting suicidal behavior based on ER Impairment, demographics, and ASD symptom severity

| CBCL 18 | Scale | B | Wald χ2 | p | Odds Ratio | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suicidality | ||||||

| Step 1. Demographics | age | .03 | 2.72 | .100 | 1.03 | .99–1.07 |

| gender | −.19 | 1.76 | .184 | .83 | .62–1.10 | |

| race | −.30 | 1.88 | .170 | .74 | .48–1.14 | |

| ethnicity | .05 | .23 | .815 | 1.06 | .67–1.65 | |

| Step 2. ASD symptom severity | SCQ total | .06 | 30.93 | <.001 | 1.06 | 1.04–1.08 |

| Group status (community ASD) | −1.24 | 17.81 | <.001 | .29 | .16–.52 | |

| Group status (inpatient ASD) | −.97 | 28.53 | <.001 | .38 | .27–.54 | |

| Step 3. ER impairment | EDI-Reactivity | .59 | 14.46 | <.001 | 1.81 | 1.33–2.46 |

| Step 4. Interaction | EDI-R × Group (community ASD) | -- | 4.85 | <.001 | 1.22 | .73–1.71 |

| EDI-R × Group (inpatient ASD) | -- | 2.03 | .042 | .55 | .02–1.07 | |

| Step 3. ER impairment | EDI-Dysphoria | .18 | 1.34 | .247 | 1.20 | .88–1.62 |

| Step 4. Interaction | EDI-D × Group (Community ASD) | -- | 3.01 | .002 | .80 | .37–1.46 |

| EDI-D × Group (Inpatient ASD) |

-- | 2.62 | .008 | .76 | .19–1.33 | |

Funding and Acknowledgements:

This study was supported with funding from NICHD R01 HD079512 (CM), the Ritvo-Slifka Award for Innovation in Autism Research (CM), Simons Foundation Autism Research Initiative and the Nancy Lurie Marks Family Foundation (SFARI #296318, M.S.). IAN is a partnership project of the Kennedy Krieger Institute and the Simons Foundation. IAN is also partially funded through a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Award for development of the National Patient-Centered Clinical Research Network, known as PCORnet.

Subjects were recruited and data obtained in partnership with the Interactive Autism Network (IAN) Research Database at the Kennedy Krieger Institute, Baltimore, MD. IAN collaborating investigators and staff included: Paul H. Lipkin, MD, J. Kiely Law, MD, MPH, Alison R. Marvin, PhD. Data were also collected in partnership with the Autism and Developmental Disorders Inpatient Research Collaborative (ADDIRC) through use of Autism Inpatient Collection (AIC) data and YouGov.

The ADDIRC is made up of the co-investigators: Matthew Siegel, MD (PI) (Maine Medical Center Research Institute; Tufts University), Craig Erickson, MD (Cincinnati Children’s Hospital; University of Cincinnati), Robin L. Gabriels,PsyD (Children’s Hospital Colorado; University of Colorado), Desmond Kaplan, MD and Rajeesh Mahajan, MD (Sheppard Pratt Health System), Carla Mazefsky, PhD (UPMC Western Psychiatric Hospital; University of Pittsburgh), Eric M. Morrow, MD, PhD (Bradley Hospital; Brown University), Giulia Righi, PhD (Bradley Hospital; Brown University), Susan L Santangelo, ScD (Maine Medical Center Research Institute; Tufts University), and Logan Wink, MD (Cincinnati Children’s Hospital; University of Cincinnati). Collaborating investigators and staff: Jill Benevides, BS, Carol Beresford,MD, Carrie Best, MPH, Katie Bowen, LCSW, Catalina Cumpanasoiu, BS, Briar Dechant, BS, Tom Flis, BCBA, LCPC, Holly Gastgeb, PhD, Angela Geer, BS, Louis Hagopian, PhD, Benjamin Handen, PhD, BCBA-D, Adam Klever, BS, Martin Lubetsky, MD, Kristen MacKenzie, BS, Zenoa Meservy, MD, John McGonigle, PhD, Kelly McGuire, MD, Faith McNeil, BS, Joshua Montrenes, BS, Tamara Palka, MD, Ernest Pedapati, MD, Kahsi A. Pedersen, PhD, Christine Peura, BA, Joseph Pierri, MD, Christie Rogers, MS, CCCSLP, Brad Rossman, MA, Jennifer Ruberg, LISW, Elise Sannar, MD, Cathleen Small, PhD, Nicole Stuckey, MSN, RN, Barbara Tylenda, PhD, Brittany Troen, MA, RDMT, Mary Verdi, MA, Jessica Vezzoli, BS, and Deanna Williams, BA. We thank the study staff for the time and energy they dedicated to this work. Special thanks also to the AIC research participants and their families that made this research possible.

Portions of these data were presented at the 2019 International Meeting for Autism Research in Montreal, CA.

Footnotes

Ethical approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Achenbach T, & Rescorla LA (2001). Manual for the ASEBA school-age forms and profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont Research Center for Children, Youth, and Families. [Google Scholar]

- Aldao A, Nolen-Hoeksema S, & Schweizer S. (2010). Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(2), 217–237. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berthoz S, & Hill EL (2005). The validity of using self-reports to assess emotion regulation abilities in adults with autism spectrum disorder. European Psychiatry, 20, 291–298. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2004.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird G, & Cook R. (2013). Mixed emotions: The contribution of alexithymia to the emotional symptoms of autism. Translational Psychiatry, 3(7), e285–8. doi: 10.1038/tp.2013.61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blakeley-Smith A, Reaven J, Ridge K, & Hepburn S. (2012). Parent–child agreement of anxiety symptoms in youth with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 6(2), 707–716. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2011.07.020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cai RY, Richdale AL, Foley K-RR, Trollor J, & Uljarević M. (2018). Brief report: Cross-sectional interactions between expressive suppression and cognitive reappraisal and its relationship with depressive symptoms in autism spectrum disorder. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 45, 1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2017.10.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cai RY, Richdale A, Uljarevic M, Dissanayake C, & Samson AC (2018). Emotion regulation in autism spectrum disorder: Where we are and where we need to go. Autism Research, 11(7), 962–978. doi: 10.1002/aur.1968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy SA, Bradley L, Bowen E, Wigham S, & Rodgers J. (2018). Measurement properties of tools used to assess depression in adults with and without autism spectrum conditions: A systematic review. Autism Research, 62, 56–70. doi: 10.1002/aur.1922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy S, Bradley L, Shaw R, & Baron-Cohen S. (2018). Risk markers for suicidality in autistic adults. Molecular Autism, 9(1), 1–14. doi: 10.1186/s13229-018-0226-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy S, Bradley P, Robinson J, Allison C, McHugh M, & Baron-Cohen S. (2014). Suicidal ideation and suicide plans or attempts in adults with asperger’s syndrome attending a specialist diagnostic clinic: A clinical cohort study. The Lancet Psychiatry, 1(2), 142–147. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(14)70248-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control. (2017). QuickStats: Suicide Rates* for Teens Aged 15–19 Years, by Sex — United States, 1975–2015. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 66(30), 816. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6630a6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conner CM, Golt J, Righi G, Shaffer RC, Siegel M, & Mazefsky CA (in preparation). The Influence of Emotion Dysregulation on Outcomes in ASD: Comparison of Inpatient ASD, Community ASD, and US Census-Matched Youth Samples. [Google Scholar]

- Conner CM, White SW, Beck KB, Golt J, Smith IC, & Mazefsky CA (2019). Improving emotion regulation ability in autism: The Emotional Awareness and Skills Enhancement (EASE) program. Autism, 23(5), 1273–1287. doi: 10.1177/1362361318810709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels AM, Rosenberg RE, Anderson C, Law JK, Marvin AR, & Law PA (2012). Verification of parent-report of child autism spectrum disorder diagnosis to a web-based autism registry. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42(2), 257–265. doi: 10.1007/s10803-011-1236-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davey S, Halberstadt J, Bell E, & Collings S. (2018). A scoping review of suicidality and alexithymia: the need to consider interoception. Journal of Affective Disorders. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.06.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demirkaya SK, Tutkunkardaş MD, & Mukaddes NM (2016). Assessment of suicidality in children and adolescents with diagnosis of high functioning autism spectrum disorder in a Turkish clinical sample. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 12, 2921–2926. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S118304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duerden EG, Oatley HK, Mak-Fan KM, McGrath PA, Taylor MJ, Szatmari P, & Roberts SW (2012). Risk factors associated with self-injurious behaviors in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42(11), 2460–2470. doi: 10.1007/s10803-012-1497-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin MS, Mazefsky CA, Ioannidis S, Erdogmus D, & Siegel M. (2019). Predicting aggression to others in youth with autism using a wearable biosensor. Autism Research, 1–11. doi: 10.1002/aur.2151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ (1998). The Emerging Field of Emotion Regulation : An Integrative Review. Review of General Psychology, 2(5), 271–299. [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ, & Thompson RA (2006). Emotion regulation: Conceptual foundations In G. J. J. (Ed.) (Ed.), Handbook of Emotion Regulation (pp. 3–26). New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gudmundsen G, McCauley E, Scholredt K, Martell C, Rhew I, Hubley S, & Dimidjian S. (2016). The Adolescent Behavioral Activation Program: Adapting Behavioral Activation as a Treatment for Depression in Adolescence. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 45(3), 291–304. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2014.979933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatkevich C, Penner F, & Sharp C. (2019). Difficulties in emotion regulation and suicide ideation and attempt in adolescent inpatients. Psychiatry Research, 271(October 2017), 230–238. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.11.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF (2015). The PROCESS macro for SPSS and SAS. [Google Scholar]

- Hedley D, Uljarević M, Wilmot M, Richdale A, & Dissanayake C. (2017). Brief Report: Social Support, Depression and Suicidal Ideation in Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47(11), 3669–3677. doi: 10.1007/s10803-017-3274-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedley D, Uljarević M, Wilmot M, Richdale A, & Dissanayake C. (2018). Understanding depression and thoughts of self-harm in autism: A potential mechanism involving loneliness. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 46, 1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2017.11.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hirvikoski T, Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Boman M, Larsson H, Lichtenstein P, & Bölte S. (2016). Premature mortality in autism spectrum disorder. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 208(3), 232–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz LM, Thurm A, Farmer C, Mazefsky C, Lanzillo E, Bridge JA, … Siegel M. (2018). Talking About Death or Suicide: Prevalence and Clinical Correlates in Youth with Autism Spectrum Disorder in the Psychiatric Inpatient Setting. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(11), 3702–3710. doi: 10.1007/s10803-017-3180-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE (2005). Why People Die by Suicide. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi G, Wozniak J, Fitzgerald M, Faraone S, Fried R, Galdo M, … Biederman J. (2018). High Risk for Severe Emotional Dysregulation in Psychiatrically Referred Youth with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Controlled Study. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48, 3101–3115. doi: 10.1007/s10803-018-3542-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato K, Mikami K, Akama F, Yamada K, Maehara M, Kimoto K, … Matsumoto H. (2013). Clinical features of suicide attempts in adults with autism spectrum disorders. General Hospital Psychiatry, 35(1), 50–53. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2012.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khor AS, Melvin GA, Reid SC, & Gray KM (2014). Coping, daily hassles and behavior and emotional problems in adolescents with high-functioning autism / Asperger’s disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44, 593–608. doi: 10.1007/s10803-013-1912-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby AV (2019). Suicide and Autism Spectrum Disorder: Associated Health Conditions. INSAR 2019 Pre-Meeting on Mental Health Montreal. [Google Scholar]

- Kirby AV, Bakian AV, Zhang Y, Bilder DA, Keeshin BR, & Coon H. (2019). A 20-year study of suicide death in a statewide autism population. Autism Research, 12, 658–666. doi: 10.1002/aur.2076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleiman EM, & Liu RT (2013). Social support as a protective factor in suicide: Findings from two nationally representative samples. Journal of Affective Disorders, 150(2), 540–545. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.01.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai JKY, Rhee E, & Nicolas D. (2017). Suicidality in Autism Spectrum Disorder: a Commentary. Advances in Neurodevelopmental Disorders, 1(3), 190–195. doi: 10.1007/s41252-017-0018-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H, Marvin AR, Watson T, Piggot J, Law JK, Law PA, … Nelson SF (2010). Accuracy of phenotyping of autistic children based on internet implemented parent report. American Journal of Medical Genetics, Part B: Neuropsychiatric Genetics, 153(6), 1119–1126. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.31103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner MD, Calhoun CD, Mikami AY, & De Los Reyes A. (2012). Understanding parent-child social informant discrepancy in youth with high functioning autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42(12), 2680–2692. doi: 10.1007/s10803-012-1525-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipkin PH, Rybczynski S, Ryan T, & Wilcox H. (2019). Screening for Suicide Risk in Children with Autism and Related Disabilities in a Pediatric Autism Center. International Meeting for Autism Research Montreal. [Google Scholar]

- Loevaas MES, Sund AM, Lydersen S, Neumer S-P, Martinsen K, Holen S, … Reinfjell T. (2019). Does the Transdiagnostic EMOTION Intervention Improve Emotion Regulation Skills in Children? Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28(3), 805–813. doi: 10.1007/s10826-018-01324-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Rutter M, DiLavore PC, Risi S, Gotham K, &, & Bishop SL (2012). Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule-2. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services. [Google Scholar]

- Maddox BB, Trubanova A, & White SW (2016). Untended wounds: Non-suicidal self-injury in adults with autism spectrum disorder. Autism. doi: 10.1177/1362361316644731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayes SD, Gorman AA, Hillwig-Garcia J, & Syed E. (2013). Suicide ideation and attempts in children with autism. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 7(1), 109–119. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2012.07.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mazefsky CA, Borue X, Day TN, & Minshew NJ (2014). Emotion regulation patterns in adolescents with high functioning autism spectrum disorder: Comparison to typically developing adolescents and association with psychiatric symptoms. Autism Research, 7(3), 344–354. doi: 10.1002/aur.1366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazefsky CA, Kao J, & Oswald DP (2011). Preliminary evidence suggesting caution in the use of psychiatric self-report measures with adolescents with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 5(1), 164–174. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2010.03.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazefsky CA, Yu L, & Pilkonis PA (In Press). Psychometric Properties of the Emotion Dysregulation Inventory in a Nationally Representative Sample of Youth. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Article In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazefsky CA, Day TN, Siegel M, White SW, Yu L, & Pilkonis PA (2018). Development of the Emotion Dysregulation Inventory: A PROMIS®ing Method for Creating Sensitive and Unbiased Questionnaires for Autism Spectrum Disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(11), 3736–3746. doi: 10.1007/s10803-016-2907-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazefsky CA, Yu L, White SW, Siegel M, & Pilkonis PA (2018). The Emotion Dysregulation Inventory: Psychometric properties and Item Response Theory calibration in an autism spectrum disorder sample. Autism Research, 11(6), 928–941. doi: 10.1002/aur.1947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMakin DL, Siegle GJ, & Shirk SR (2011). Positive Affect Stimulation and Sustainment (PASS) module for depressed mood: A preliminary investigation of treatment-related effects. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 35(3), 217–226. doi: 10.1007/s10608-010-9311-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AB, McLaughlin KA, Busso DS, Brueck S, Peverill M, & Sheridan MA (2018). Neural Correlates of Emotion Regulation and Adolescent Suicidal Ideation. Biological Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging, 3(2), 125–132. doi: 10.1016/j.bpsc [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Hwang I, Sampson N. a, & Kessler RC (2010). Mental disorders, comorbidity and suicidal behavior: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Molecular Psychiatry, 15(8), 868–876. doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock Matthew K., Green JG, Hwang I, McLaughlin KA, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, & Kessler RC (2013). Prevalence, correlates and treatment of lifetime suicidal behavior among adolescents: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication-Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). JAMA Psychiatry, 70(3), 1–24. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamapsychiatry.55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock Matthew K., & Mendes WB (2008). Physiological Arousal, Distress Tolerance, and Social Problem-Solving Deficits Among Adolescent Self-Injurers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(1), 28–38. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.1.28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor RC (2011). The integratedmotivational-volitional model of suicidal behavior. Crisis, 32(6), 295–298. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor RC, & Nock MK (2014). The psychology of suicidal behaviour. The Lancet Psychiatry, 1(1), 73–85. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(14)70222-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raja M, Azzoni A, & Frustaci A. (2011). Autism Spectrum Disorders and Suicidality. Clinical Practice and Epidemiology in Mental Health, 7(1), 97–105. doi: 10.2174/1745017901107010097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richa S, Fahed M, Khoury E, & Mishara B. (2014). Suicide in Autism Spectrum Disorders. Archives of Suicide Research, 18(4), 327–339. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2013.824834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M, Bailey A, & Lord C. (2003). The Social Communication Questionnaire. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services. [Google Scholar]

- Samson AC, & Antonelli Y. (2013). Humor as character strength and its relation to life satisfaction and happiness in Autism spectrum disorders. Humor, 26(3), 477–491. doi: 10.1515/humor-2013-0031 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Samson AC, Hardan AY, Lee IA, Phillips JM, & Gross JJ (2015). Maladaptive Behavior in Autism Spectrum Disorder: The Role of Emotion Experience and Emotion Regulation. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45(11), 3424–3432. doi: 10.1007/s10803-015-2388-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samson AC, Huber O, & Ruch W. (2013). Seven decades after Hans Asperger’s observations: A comprehensive study of humor in individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Humor, 26(3), 441–460. doi: 10.1515/humor-2013-0026 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Segers M, & Rawana J. (2014). What do we know about suicidality in autism spectrum disorders? A systematic review. Autism Research, 7(4), 507–521. doi: 10.1002/aur.1375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer RC, Wink LK, Ruberg J, Pittenger A, Adams R, Sorter M, … Erickson CA (2019). Emotion Regulation Intensive Outpatient Programming: Development, Feasibility, and Acceptability. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49(2), 495–508. doi: 10.1007/s10803-018-3727-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel M, Doyle K, Chemelski B, Payne D, Ellsworth B, Harmon J, … Lubetsky M. (2012). Specialized inpatient psychiatry units for children with autism and developmental disorders: A United States survey. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42(9), 1863–1869. doi: 10.1007/s10803-011-1426-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel M, Smith KA, Mazefsky C, Gabriels RL, Erickson C, Kaplan D, … Santangelo SL (2015). The autism inpatient collection: methods and preliminary sample description. Molecular Autism, 6(61), 1–10. doi: 10.1186/s13229-015-0054-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone DM, Simon TR, Fowler KA, Kegler SR, Yuan K, Holland KM, … Crosby AE (2018). Vital Signs: Trends in State Suicide Rates — United States, 1999–2016 and Circumstances Contributing to Suicide — 27 States, 2015 . MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 67(22), 617–624. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6722a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storch EA, Sulkowski ML, Nadeau J, Lewin AB, Arnold EB, Mutch PJ, … Murphy TK (2013). The phenomenology and clinical correlates of suicidal thoughts and behaviors in youth with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43(10), 2450–2459. doi: 10.1007/s10803-013-1795-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stratis EA, & Lecavalier L. (2017). Predictors of Parent – Teacher Agreement in Youth with Autism Spectrum Disorder and Their Typically Developing Siblings. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47(8), 2575–2585. doi: 10.1007/s10803-017-3173-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Eck K, Ballard E, Hart S, Newcomer A, Musci R, & Flory K. (2015). ADHD and Suicidal Ideation: The Roles of Emotion Regulation and Depressive Symptoms Among College Students. Journal of Attention Disorders, 19(8), 703–714. doi: 10.1177/1087054713518238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkaert B, Wante L, Vervoort L, & Braet C. (2018). ‘Boost Camp’, a universal school-based transdiagnostic prevention program targeting adolescent emotion regulation; evaluating the effectiveness by a clustered RCT: a protocol paper. BMC Public Health, 18(1), 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner L, Flin A, Causin J, Weibel S, & Bertschy G. (2019). A case study of suicidality presenting as a restricted interest in autism Spectrum disorder. BMC Psychiatry, 19(126), 1–5. doi: 10.1186/s12888-019-2122-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss JA (2014). Transdiagnostic case conceptualization of emotional problems in youth with ASD: An emotion regulation approach. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 21, 331–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss JA, Thomson K, Burnham Riosa P, Albaum C, Chan V, Maughan A, … Black K. (2018). A randomized waitlist-controlled trial of cognitive behavior therapy to improve emotion regulation in children with autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 59(11), 1180–1191. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JMG, & Williams M. (1997). Cry of pain: Understanding suicide and self-harm. Penguin Group; USA. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.