Abstract

Purpose

We assessed experienced clinicians' perceptions of benefits and drawbacks to the clinical adoption of pharyngeal high-resolution manometry (HRM). This article focuses on the professional and institutional factors that influence the clinical adoption of pharyngeal HRM by speech-language pathologists (SLPs).

Method

Two surveys (closed- and open-ended questions) and a series of focus groups were completed with SLP members of both the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association and the Dysphagia Research Society (DRS). Transcripts were inductively coded for emergent themes.

Results

Thirteen SLPs were recruited to attend focus group sessions at the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. Eighty-seven SLPs responded to the DRS open-set response survey. Two additional focus groups of 11 SLPs were convened at the DRS meeting. Conventional content analysis revealed overall SLP enthusiasm for the clinical use of HRM, with some concerns about the technology adoption process. The following themes related to the professional and institutional factors influencing clinical adoption were identified: (a) scope of practice, (b) access, (c) clinical workflow, and (d) reimbursement.

Conclusion

These data serve to elucidate the most salient factors relating to the clinical adoption of pharyngeal HRM into routine speech-language pathology clinical practice. While enthusiasm exists, a variety of systems-level issues must be addressed to support this process.

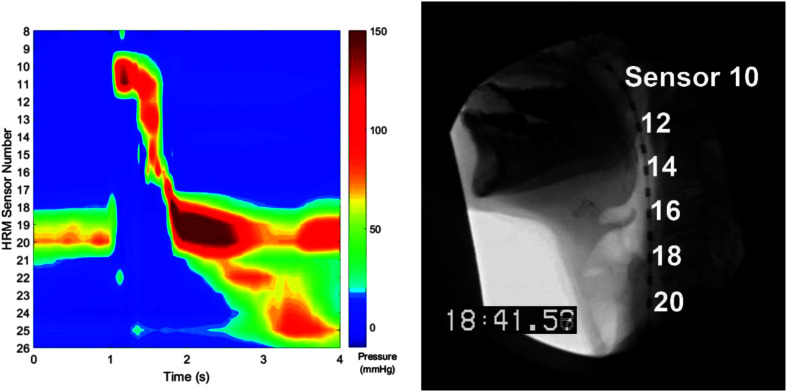

New diagnostic and treatment technologies are becoming increasingly available within the clinical practice of the speech-language pathologist (SLP). Accordingly, acceptance of this technology by SLPs is of increasing interest to the field. High-tech advancements in manometry (solid-state catheters, circumferential sensors, closer spacing of sensors; Clouse, 2001) have led to high-resolution manometry's (HRM's) establishment as a tool in the evaluation of esophageal disorders (Bredenoord et al., 2012). More recently, pharyngeal HRM has been developed to allow for measurement of the spatiotemporal features of pharyngeal swallowing and to define pressure events within the swallow (Knigge et al., 2014; see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Pharyngeal high-resolution manometry (HRM) spatiotemporal plot.

Recent studies support the importance of HRM in understanding normal swallowing physiology (Hammer et al., 2014; Kim et al., 2015; May et al., 2020; Meyer et al., 2016; Ryu et al., 2015, 2016) and in the diagnosis of dysphagia used to inform treatment recommendations (Ferris et al., 2016; Jungheim & Ptok, 2018; Knigge & Thibeault, 2016; Lee et al., 2014; Regan, 2020; Suh et al., 2019). By providing objective information regarding pressure generation, pharyngeal HRM may elucidate biomechanical underpinnings of dysphagia that cannot be gleaned from visualization alone. For example, the reason for pharyngeal residue in the valleculae is not always clear. This ambiguity may result in inappropriate treatment recommendations (prescribing exercises to improve base-of-tongue retraction when pressures at the base of tongue are adequate). The additional information provided by pharyngeal HRM regarding areas of abnormal pressure generation can clarify the biomechanical impairment underlying the observed symptom (e.g., residue), resulting in more effective treatment.

Despite methodological variability in the implementation of pharyngeal HRM (Winiker et al., 2019), efforts toward standardization of pharyngeal HRM acquisition, measurement, and reporting are underway (Omari et al., 2019). Recent findings have begun to elucidate which pharyngeal HRM metrics may be most useful in dysphagia diagnosis and research. Additionally, pharyngeal HRM has been found to be tolerated well by patients and to be a useful tool in providing the patient with biofeedback while they are performing swallowing exercises (Knigge et al., 2019, 2014). However, despite the potential of pharyngeal HRM to improve diagnosis and guide treatment of swallowing disorders when used as part of a collaborative, multidisciplinary clinic (Knigge et al., 2014), HRM has yet to be widely adopted clinically by SLPs (Ryu et al., 2015). Therefore, pharyngeal HRM can serve as a case of a new technology with the potential to be implemented in speech-language pathology clinical practice.

User acceptance and adoption behavior have been studied for technologies in health care settings (Beynon-Davies, 1999; Chang & Hsu, 2012; Li et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2015; Rahimpour et al., 2008; Whitten et al., 2010). A recent publication, based on a distinct qualitative analysis of the same data set used in this study, focused on SLP perceptions of patient-centric benefits of clinical HRM use in the diagnostic and treatment process, which patient populations would most benefit, and the optimal timing of pharyngeal HRM in this process (Jones, Rogus-Pulia, et al., 2019). Results revealed broad consensus regarding how pharyngeal HRM's objective data could improve diagnosis and treatment but less consensus among SLPs regarding which patients would be most likely to benefit and the ideal timing in the clinical process for use of HRM. While these insights regarding individual provider characteristics and perceived patient benefits are critically important to the clinical adoption of pharyngeal HRM, in order to fully elucidate barriers and facilitators, a systems-level perspective that considers factors at an institutional level is necessary to understand how SLPs view the process of bringing a new technology into clinical practice within the broader health care environment.

The provider's intention has been shown to be a major driver in the adoption process that can be influenced by a multitude of factors included in technology adoption models (Ajzen, 1991; Compeau & Higgins, 1995; Davis, 1989; Dünnebeil et al., 2010; Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975; Liu et al., 2015; Moore & Benbasat, 1991; Taylor & Todd, 1995; Venkatesh et al., 2003). Facilitating conditions are objective factors in the environment that improve the ease of accomplishing a task (Thompson et al., 1991; Venkatesh et al., 2003). Another recent publication based on closed-response survey questions administered to a similar group of expert SLPs described in this study has shown that those with training in more types of instrumentation and the belief that they could explain the HRM procedure to a patient were more likely to plan to adopt pharyngeal HRM into regular clinical practice (Jones, Forgues, et al., 2019).

However, beyond factors at the patient and individual-provider levels, the field of human factors focuses on interactions between individuals (i.e., providers) and their environment (i.e., health system) that contribute to performance, safety, health, quality of working life, and services produced (Carayon et al., 2006; Getty & Getty, 1999; Wilson, 2000). In addition to facilitating conditions, there may be professional (e.g., scope of practice) or institutional (e.g., equipment access) factors that facilitate the provider's intention to adopt or create barriers to that process. The purpose of this study was to explore how SLPs perceive these systems-level factors (professional and institutional) in influencing the clinical adoption of pharyngeal HRM.

Method

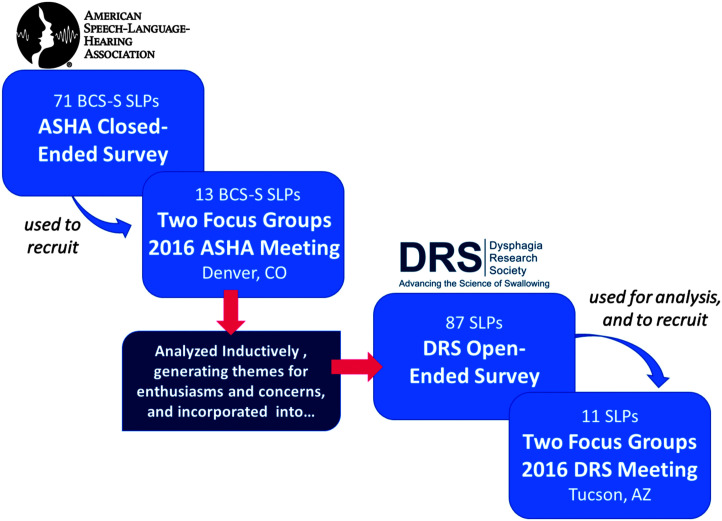

Overall, two surveys and a series of focus groups were convened using an explanatory sequential mixed-method design (Creswell & Creswell, 2018). This approach includes collecting quantitative data first to test the prevalence of various viewpoints and then collect qualitative data to explore how and why representative individuals feel the way they do. Our research began with a quantitative survey to analyze the distribution of a wide range of views on HRM among American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA)–affiliated SLPs who were board-certified specialists in swallowing and swallowing disorders (BCS-S). Then, survey respondents were recruited to participate in focus groups to give SLPs hands-on experience with using HRM in a mock clinical context and to collect in-depth data about how they viewed the possibilities of using HRM in their clinical practices. A qualitative survey of Dysphagia Research Society (DRS)–affiliated SLPs was administered to supplement the focus groups. This article is based on an analysis of data collected at four focus groups and in open-response surveys with SLPs who were members of DRS or ASHA. Participants' demographic data relevant to this article are found in Table 1. Figure 2 shows the order in which focus groups were convened and surveys were administered.

Table 1.

Demographic information for survey respondents.

| Demographic information | No. of responses |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| ASHA survey (n = 71) | DRS survey (n = 87) | ||

| Practice setting a | University or research hospital | 42 | 46 |

| Community hospital | 25 | 19 | |

| VA hospital | 7 | 6 | |

| All other hospitals | 5 | 11 | |

| Outpatient rehabilitation center | 10 | 11 | |

| Skilled nursing facility | 4 | 8 | |

| Assisted living | 2 | 2 | |

| Home health agency/patient's home | 2 | 5 | |

| Private practice | 10 | 9 | |

| College/university | 13 | 12 | |

| Research/scientific organization, foundation, lab | 4 | 12 | |

| Other | 10 | 7 | |

| Care level a | Outpatient | 53 | 51 |

| Acute | 59 | 52 | |

| Long-term acute | 11 | 6 | |

| Inpatient rehabilitation | 29 | 23 | |

| Subacute/transitional care | 13 | 11 | |

| Hospice/palliative care | 13 | 21 | |

| Research participants | 24 | 33 | |

| Other | 1 | 4 | |

Note. ASHA = American Speech-Language-Hearing Association; DRS = Dysphagia Research Society.

Categories are not mutually exclusive.

Figure 2.

Survey and focus group timeline. BCS-S = board-certified specialists in swallowing and swallowing disorders; SLPs = speech-language pathologists.

Survey and focus group methods were approved by the local institutional review board and were carried out according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided informed consent prior to participating.

Focus Groups at ASHA and DRS

Focus Group Design and Pilot Testing

Focus group question pathways were designed following accepted principles (Krueger & Casey, 2009). Participants were given a presentation on how to use and analyze HRM data, were also given a hands-on exercise with hypothetical patients, and then engaged in an hour-long discussion of their experience and of their views on the potential for clinical adoption of HRM. Questions were open-ended and were designed to elicit participant reflections on their experience using HRM in the demonstration and their views on whether or not they envisioned adopting HRM in clinic for the diagnosis and treatment of swallowing disorders.

The presentation, hands-on exercises, and question pathways were pretested with a group of eight SLPs recruited through a local interdisciplinary swallowing journal club prior to implementation at the national meetings. The pretest data are not included in this analysis because these local SLPs had preexisting familiarity with HRM.

ASHA

Through outreach to the 71 BCS-S ASHA members who responded to the closed-response survey, we recruited those SLPs who planned to attend the 2015 ASHA Convention in Denver, CO. Based on those who indicated interest, two focus groups were convened. Focus group participants at each meeting are outlined in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of focus group participants.

| Focus group | Registered (n) | Attended (n) |

|---|---|---|

| ASHA Group 1 | 8 | 7 |

| ASHA Group 2 | 7 | 6 |

| DRS Group 1 | 7 | 6 |

| DRS Group 2 (repeat attendees) | 7 | 5 |

| Total | 18 uniques/24 total |

Note. ASHA = American Speech-Language-Hearing Association; DRS = Dysphagia Research Society.

DRS Focus Groups

An invitation to participate in a focus group at the 2016 DRS Annual Meeting in Tucson, AZ, was also sent to all members of DRS who were SLPs (n = 300). Fourteen SLPs indicated that they would attend the meeting and would be interested in attending a hands-on demonstration and a focus group. Of those, half had attended the prior focus group at ASHA. Of the 14 who registered, 11 attended. Those who had not previously attended a focus group were given the same hands-on demonstration as those at AHSA, and those returning focus group participants were shown some changes to the software interface that had been made based on input from focus group attendees at ASHA.

Analysis of Focus Group Data

Focus groups were audio-recorded and digitally transcribed verbatim. Two research team members (A. F. and C. M.) coded the focus group transcripts using a conventional content analysis approach and NVivo 11 software (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). This coding process involved developing a codebook composed of major themes emerging out of the data. While some of these themes were based on the questions asked at the focus group, others, including the theme of disciplinary boundaries addressed in this article, emerged unprompted in each group. All authors reviewed and approved the codebook. The resulting focused codes were applied to all transcripts using NVivo 11.

Survey With Open-Ended Response Format

To test whether the responses offered in the focus groups convened at ASHA were representative of the broader medical speech-language pathology community, the team designed a set of open-ended survey questions based on the primary facilitators and barriers identified by the focus group participants. The survey included an embedded video explaining HRM and its potential use in clinical practice and explored themes that arose in the focus groups, including interest in the clinical adoption of HRM, perceived ease of use, perceived fit into workflow, perceived patient benefits, and any perceptions about facilitators and barriers to implementation. The survey link was e-mailed to SLP members of DRS (N = 300), and 87 members responded in full.

The narrative answers to the open-ended questions were analyzed and coded thematically line-by-line using NVivo 11 software (QSR International) by two authors (C. M. and A. F.). The team first coded inductively to elicit any emergent categories and then applied the codebook developed from the focus groups to the survey responses. No new themes emerged, and the survey responses aligned with the themes from the analysis of the focus groups.

Results

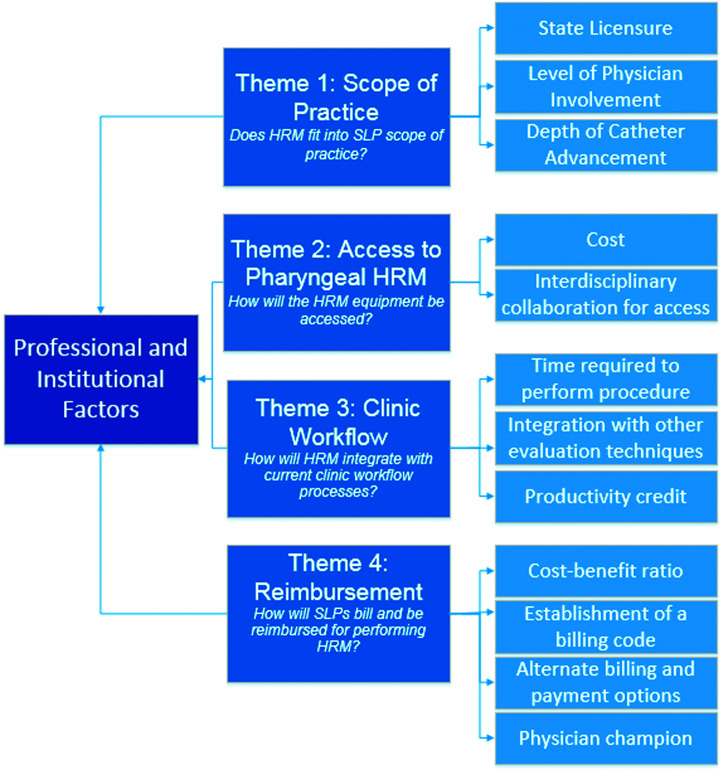

All focus group participants (n = 18) stated that they would be interested in adopting pharyngeal HRM in clinic; only two had used it in clinic but were not current users. Of the 87 open-ended survey respondents, nine currently use HRM, 55 did not but stated that they would like to, and 16 reported that they were not current users and had no plans to adopt the technology. Overall, as previously reported, SLPs expressed a strong enthusiasm for the clinical adoption of pharyngeal HRM (Jones, Rogus-Pulia, et al., 2019). However, respondents also expressed a range of concerns and common misconceptions regarding the pathway to adoption, including several involving professional and institutional barriers to clinical adoption that differed significantly from the patient-focused and individual-level concerns addressed in other articles. These concerns reflecting the current implementation climate were grouped into four thematic categories: (1) pharyngeal HRM within speech-language pathology scope of practice, (2) access to pharyngeal HRM, (3) clinical workflow, and (4) reimbursement (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Themes and subthemes for professional and institutional factors. HRM = high-resolution manometry; SLP = speech-language pathologist.

Theme 1: Scope of Practice

SLPs with dysphagia expertise expressed concerns about whether pharyngeal HRM would fit into the SLPs' scope of practice. Within this theme, we identified three subthemes: (a) state licensure, (b) level of physician involvement, and (c) depth of catheter advancement. The discussion related to these subthemes varied depending upon which stage of the pharyngeal HRM adoption process the SLPs were considering: (a) insertion and advancement of the HRM catheter or (b) analysis of data obtained during the pharyngeal HRM procedure (see Table 3 for relevant quotes associated with each subtheme).

Table 3.

Scope of practice theme.

| Subthemes | Representative quotes |

|---|---|

| State licensure | -“…in my state, for SLPs to perform HRM (of the esophagus, anyway), the procedure would need to be included in their scope of practice….not a trivial matter” (Survey; 35 years in practice, university hospital, 20 patients/week) |

| Level of physician involvement | |

| Insertion and advancement of the scope | -“…the only route I'd have to go then would be to advocate through the physicians for them to be the ones to have the equipment and to do the procedure. And I would just have access to the data” (Focus group; 12 years in practice, acute care hospital/outpatient rehabilitation, 35–40 patients/week) -“Well, you could collaborate…with the GI lab, I mean, the nurses in the GI lab do the manometry now in there….” (Focus group; clinical practice information not available) -“…given regulations for physician supervision of FEES procedures, I may be limited to use of this procedure only when I'm in the same building as one of my physicians.” (Survey; 9 years in practice, community hospital/outpatient rehabilitation/home health, 24 patients/week) |

| Analysis of HRM data | -“So what the physicians are saying to me is…you'll be able to integrate it clinically and let us know what we need to do. They like it. They see the purpose of it. But they don't know how to read it.” (Focus group; 33 years in practice, critical care/neonatal intensive care, 25 patients/week) “…you wouldn't need a physician to read your study…so there would be no POS, physician on shoulder….” (Focus group; clinical practice information not available) |

| Depth of catheter advancement | |

| Insertion and advancement of the scope | -“I think that if the esophagus is studied, that a physician should be involved. If the pharynx only, no need for a physician.” (Survey; 28 years in practice, inpatient/outpatient rehabilitation hospital, 6 patients/week) -“But that's where things get very hairy is how far do you sink the catheter?” (Focus group; clinical practice information not available) -“I'd like to have the catheter go from the velopharynx to the LES and look at the pharyngeal-esophageal dynamics…that would be my Crème de la Crème.” (Focus group; 33 years in practice, critical care/neonatal intensive care, 25 patients/week) |

| Analysis of HRM data | -“Well, a lot of these things, we can't actually diagnose as speech pathologists. Like we can't diagnose a stricture. We can't diagnose a CP bar. We can use wording like consistent with or suggestive of or refer to radiology report, but we actually cannot diagnose.” (Focus group; clinical practice information not available) |

Note. HRM = high-resolution manometry.

State Licensure

Several SLPs pointed out the lack of clear guidelines regarding how pharyngeal HRM fits into the scope of practice of SLPs. They attributed this confusion to the recent development and implementation of pharyngeal HRM. Some expressed that these guidelines at a state level would be important in supporting further clinical use of pharyngeal HRM. Participants agreed that state licensure guidelines need to be clarified to support further clinical adoption of pharyngeal HRM.

Degree of Physician Involvement

Several SLPs also wondered how much physicians would need to be involved in oversight and collaboration in the clinical use of HRM. Regarding insertion and advancement of the catheter, several SLPs felt that the physician would need to perform the procedure, and then the SLP would access the data. Some mentioned the possibility of collaboration with either gastroenterologists or nurses in the gastroenterology lab who are already performing esophageal manometry and discussed the benefits of working together with these professionals. Others felt that, so long as the physician was present in the same facility, the SLP could perform the procedure independently. Others in the group expressed that, if the evaluation was focused solely on the pharynx and did not include evaluation of the esophagus, SLPs should be able to perform the procedure independently. It is clear from this wide range of responses that clarification of practice guidelines will need to be updated before HRM can be adopted for widespread clinical use.

When discussing analysis of HRM data, SLPs expressed concern that physicians might interpret pharyngeal pressures incorrectly. Others felt that physicians would find the information provided by pharyngeal HRM useful for guiding treatment but that they would need to rely on the SLP to interpret the data within the appropriate clinical context. Several SLPs discussed that interpretation of HRM data would not require a “physician on shoulder” and could be performed independently by the SLP. One SLP suggested working with the physician on interpretation of the data to improve the quality of the analysis and to support difficult cases. While there is still a debate regarding the degree of physician involvement necessary for catheter insertion or advancement, participants generally agreed that the analysis of the pharyngeal HRM data is within the scope of speech-language pathology.

Depth of Catheter Advancement

Another subtheme identified within scope of practice concerned depth of catheter advancement and involvement of the esophagus in the evaluation. Some SLP respondents suggested that inclusion of the esophagus in the study would mean that the physician should be involved or even serve as the lead for the evaluation. Others pointed out that it is not clear who should perform the esophageal portion of the evaluation and where the boundaries are in terms of how far the SLP would advance the catheter when performing the procedure. Several SLPs suggested that evaluation of pharyngeal and esophageal pressures should be performed in combination by the SLP given that swallowing is a dynamic process and these stages are interrelated; while one raised the question whether patient consent would be needed for advancement of the catheter beyond the upper esophageal sphincter, an issue that would not exist with fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing (FEES) as a comparison.

That said, several SLPs pointed out that concerns about scope of practice extend beyond questions of instrumentation to who should interpret the data. They argued that diagnosis of esophageal issues, such as a stricture or a cricopharyngeal bar, is not within the SLP's scope of practice. Therefore, if analysis of the esophagus was involved, analysis of the HRM data would fall outside the SLP's scope. There remains a debate as to whether advancement of the catheter into the esophagus is within the scope of the SLP, but participants agreed that diagnosis of esophageal disorders is not. These concerns speak not only to the need for clarification of scope of practice guidelines when introducing a new technology into diagnosis and treatment protocols but also to how deeply SLPs are embedded in interdisciplinary teams.

Theme 2: Access to Pharyngeal HRM

A second major theme involved how SLPs would access pharyngeal HRM for clinical use. There were two subthemes identified: (a) cost of machines, catheters, and sterilization and (b) the need for interdisciplinary collaboration to allow for access (see Table 4 for quotes relevant to this theme and subthemes).

Table 4.

Access to pharyngeal high-resolution manometry theme.

| Subthemes | Relevant quotes |

|---|---|

| Cost | -“What would be a minimum set for a true working clinic? And you know, is it cleaned Cidex is it cleaned in, what is the processing methods? How much does that cost?” (Focus group; clinical practice information not available) -“My biggest concern, honestly, is the cost of the equipment and the access to the equipment.” (Focus group; 21 years in practice, university hospital, 10–12 patients/week) |

| Interdisciplinary collaboration for access | -“Would need to discuss with our GI colleagues. Not sure what manometric equipment they currently have/use.” (Survey; 28 years in practice, university/community hospital/private practice, 18 patients/week) “Would need to liaise with gastroenterologist for equipment access.” (Survey; 19 years in practice, all other hospitals (acute care), 15 patients/week) |

Cost

Several SLPs mentioned the high costs associated with the HRM machine as well as the individual catheters. One SLP also discussed costs related to sterilization of the catheters. Participants were in consensus regarding the cost-related concerns associated with the clinical adoption of pharyngeal HRM.

Interdisciplinary Collaboration for Access

Several SLPs felt that they would need to team with gastroenterology colleagues to have access to HRM equipment at their facilities. One SLP pointed out that they would need to advocate through physicians for the equipment as this SLP did not feel they had enough knowledge regarding the process of setting up the equipment. There was general agreement among the participants that interdisciplinary collaboration would be necessary to facilitate access to HRM clinically.

Theme 3: Clinical Workflow

Concerns about clinical workflow emerged as a third major theme, specifically about the ways in which use of pharyngeal HRM in speech-language pathology practice could affect workflow. There were three subthemes that emerged: (a) time required to perform the procedure, (b) integration with other evaluation techniques, and (c) productivity reporting (see Table 5 for quotes relevant to this theme and subthemes).

Table 5.

Clinical workflow theme.

| Subthemes | Relevant quotes |

|---|---|

| Time required to perform the procedure | -“I would (initially) want to do VFSS simultaneously to make diet recommendations, since that is currently the primary goal of referring SLPs/Drs…. I'd want to use it within a 45-minute visit, including results and recommendations.” (Survey; 10 years in practice, community hospital/outpatient rehabilitation/home health, 30 patients/week) -“Due to physician involvement and placement of manometric catheter, an increase in diagnostic time would most likely be warranted.” (Survey; 21 years in practice, university hospital, no clinic time) |

| Integration with other evaluation techniques | -“Clinical eval; FEES, VFSS, HRM—in that order…as an adjunct to a clinical and VFSS eval.” (Survey; 19 years in practice, all other hospitals [acute care], 15 patients/week) -“HRM would help screen patients for further visual investigations, such as MBS/VFSS or FEES while providing objective assessment of pharyngeal contraction, etc.” (Survey; 5 years in practice, university hospital, 5 patients/week) -“At my facility, we do esophageal manometry. A lot of that data is not focused on the pharynx in general, but are we going to do it as two separate studies based upon scope of practice? So that makes things difficult.” (Focus group; 6 years in practice, university hospital, 30 patients/week) |

| Productivity reporting | “Our ENT is the one that's billing for the procedure. And so even though the speech pathologist is in there for 30, 45 minutes, she's not billing for anything. So between productivity and cost requirements, right now, it doesn't really make sense.” (Focus group; 7 years in practice, university hospital, 30 patients/week) -“…if SLPs were…doing the studies, and not be able to bill (or otherwise get credit) for them, clinic/hospital administrators would question clinicians' ‘productivity.’ Sad, but true.” (Survey; 35 years in practice, university hospital, 20 patients/week) |

Time Required to Perform the Procedure

Several SLPs were concerned that both the time involved in instrumentation and in analysis for pharyngeal manometry would be a barrier to incorporating the technology into their workflow. One SLP requested that the HRM procedure be fit into a 45-min visit time frame. Another SLP addressed the need to consider the sterilization process of the catheters between each use and to determine how many catheters are needed when taken that into account and scheduling multiple patients. Others argued that the increased diagnostic time needed for pharyngeal HRM was necessary and justified. There was a debate among focus group participants as to whether the time for the pharyngeal HRM procedure would be a concern in further clinical adoption of the technology.

Integration With Other Evaluation Techniques

Another concern raised by the SLPs was where and how pharyngeal HRM would fit in with other evaluation techniques that are used for swallowing, including FEES and videofluoroscopy (videofluoroscopic swallowing study [VFSS]). Several SLPs described pharyngeal HRM as a screening technique to determine if further assessment with FEES or VFSS would be needed. Others felt that pharyngeal HRM would come after the other evaluation approaches and that it should be viewed as an adjunct to them. One SLP described how having access to pharyngeal HRM would streamline the process of evaluation and care by avoiding a referral to gastroenterology. Another SLP felt that having the ability to perform HRM and include the esophageal assessment would streamline patient care and avoid inefficient need for two separate assessments of swallowing. Although participants agreed on the complementary nature of HRM, there was a lack of consensus among participants regarding ways that pharyngeal HRM could integrate with other currently used evaluation techniques.

Productivity Reporting

Several SLPs raised concerns about productivity reporting in terms of time spent on pharyngeal HRM. If the physician or nurse is billing for the procedure but the SLP is dedicating a significant amount of time to being present and assisting with interpretation, the SLP's time would not be captured in terms of productivity. The participants generally agreed that productivity reporting would be a concern for further clinical adoption of pharyngeal HRM that would need to be addressed to ensure SLPs can account for their time dedicated to the procedure.

Theme 4: Reimbursement

The final theme that emerged within the professional and institutional factors category was reimbursement for pharyngeal HRM. Three subthemes were identified: (a) cost–benefit ratio, (b) establishment of a billing code, (c) alternate billing and payment options, and (d) physician champion (see Table 6 for quotes relevant to this theme and subthemes).

Table 6.

Reimbursement theme.

| Subthemes | Relevant quotes |

|---|---|

| Cost–benefit ratio | -“…the machine's outrageously expensive…and the reimbursement is low….” (Focus group; clinical practice information not available) -“We do not see a high enough volume patients that would recover costs with reimbursement.” (Survey; 18 years in practice, community hospital/outpatient rehabilitation, 20 patients/week) -“…looking at the cost–benefit ratio, it takes three or more people to do a fluoro study…this cost–benefit ratio makes a lot of sense.” (Focus group; 12 years in practice, Veterans Affairs hospital, 35 patients/week) |

| Establishment of a billing code | -“Without adequate potential for reimbursement, I will not request the department purchase the equipment.” (Survey; 28 years in practice, university/community hospital/private practice, 18 patients/week) -“We would work with the hospital to establish a fee for the service. However, our department only gets productivity credit for procedures that do have a CPT code, so that could be problematic.” (Survey; 38 years in practice, community hospital, 5 patients/week) |

| Alternate billing and payment options | -“We usually just lump those procedures in with other billable procedures. For example, if I want to use FEES for biofeedback, I would bill that session as a dysphagia therapy session. Or if we're using electrodes, we bill dysphagia therapy and just absorb the costs of any non-covered supplies.” (Survey; 9 years in practice, community hospital/outpatient rehabilitation/home health, 24 patients/week) -“A mix of private pay and government insurance.” (Survey; 4 years in practice, university hospital, no clinic time) -“We can do some studies gratis as part of a research study and eat the cost of the service, or bill to a grant if the project is funded.” (Survey; 25 years in practice, university hospital, 20 patients/week) |

| Physician champion | -“ So I e-mailed yesterday our healthcare economics committee co-chair…and that's one of the committees at ASHA, and so the response was we don't have a CPT code for this, so but probably would need to be initiated by the GI and/or ENT docs at the…AMA level…and then we would jump in and provide the support to then have a CPT code…And that could take a while.” (Focus group; 29 years in practice, university hospital, 30 patients/week) |

Cost–Benefit Ratio

SLPs discussed the concept of cost–benefit ratio as it applies to clinical use of pharyngeal HRM. Several SLPs expressed that, given the high cost of the machine without a high enough volume of patients and low reimbursement, it would not be worth performing pharyngeal HRM. One SLP went through the same cost–benefit analysis but concluded that this ratio justified use of pharyngeal HRM. This SLP considered the increased staffing resources needed for a videofluoroscopic swallow evaluation as compared to pharyngeal HRM and also the potential use of HRM as a screen to determine if videofluoroscopy is necessary, which would be cost saving. There was a debate among the participants regarding the cost–benefit ratio for the clinical use of pharyngeal HRM.

Establishment of a Billing Code

Several SLPs pointed out the need for establishment of a billing code for pharyngeal HRM. The SLPs emphasized that no insurance reimbursement would take place or no productivity credit given without the billing code; and therefore, without that code, facilities will be discouraged from performance of the procedure. In considering how that code would be established, one SLP pointed out the need for a separate technical versus professional components to capture the various professional roles accurately. Participants agreed that a billing code for pharyngeal HRM would need to be established to make further clinical adoption of the technology viable.

Alternate Billing and Payment Options

This group of SLPs also discussed how pharyngeal HRM might be billed as part of another billable procedure. One SLP pointed out that pharyngeal HRM could be billed alongside FEES or as part of a therapy session when used as biofeedback. Several SLPs mentioned that the procedure could be paid for through private pay or government insurance or as a research study. There was some debate among participants regarding the feasibility of billing for pharyngeal HRM as part of another billable study.

Physician Champion

Several SLPs mentioned the need for a physician champion at the national level, specifically with ASHA and the American Medical Association, for these organizations to prioritize their assistance with the establishment of a billing code for pharyngeal HRM. Participants generally agreed that a physician champion for pharyngeal HRM will be necessary for this process to move forward in support of further clinical adoption.

Discussion

This study elucidates key professional and institutional factors that structure the current implementation climate and are likely to influence the clinical adoption of pharyngeal HRM. There is clear enthusiasm for the integration of this technology into widespread clinical care. However, there were barriers to adoption identified, which related to scope of practice, access to the technology, impact on clinical workflow, and ability to be reimbursed for the procedure and analysis. Additionally, although many of the barriers identified by respondents in this study are valid, some perceived barriers reflect common misconceptions of those without pharyngeal HRM experience that need to be addressed.

The scope of practice theme emerged unprompted from both focus groups and the survey responses and points to the unique position of the SLP within an interdisciplinary clinical team. Studies of technology adoption in nursing or physician care do not include scope of practice as a domain (Ajzen, 1991; Chen et al., 2015; Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975; Moore & Benbasat, 1991; Taylor & Todd, 1995; Venkatesan et al., 1993). Our findings suggest that this issue may be somewhat unique to SLPs. SLPs may be unusual among clinical disciplines in the degree and nature of overlap between their work and that of their nursing and physician colleagues. Considering that pharyngeal HRM is new to the clinical world of speech-language pathology, there are likely some parallels between its adoption and the early adoption of videofluoroscopy and FEES for clinical use.

Initial development and implementation of the VFSS test raised questions related to scope of practice as the evaluation and treatment of swallowing disorders fell within the realms of gastroenterology, radiology, neurology, and otolaryngology. The primary role of the SLP in dysphagia management and incorporation of videofluoroscopy into standard practice required design of a systematic approach, collaboration with other medical disciplines, and appropriate training and education of SLPs (Miller & Groher, 1993). Similarly, Hiss and Postma (2003) point out in a historical review on the topic of FEES the controversy between SLPs and surgeons in terms of who would perform and interpret FEES. In the early stages of FEES clinical adoption and implementation, some of the concerns stemmed from the inability of the SLP to diagnose nasal, pharyngeal, laryngeal, or subglottic diseases. This is similar to concerns expressed by the SLPs in our sample regarding inclusion of the esophagus in the evaluation without the ability to diagnose esophageal conditions. The approach adopted by SLPs specific to FEES was to focus the speech-language pathology portion of the exam on the diagnosis and treatment of dysphagia only and to leave diagnosis of other medical conditions to the otolaryngologist (Hiss & Postma, 2003). The logistics of how this happens in clinical practice does depend on the facility and/or state licensing guidelines, with some SLPs referring to an otolaryngologist if there are concerns on the FEES exam, others performing the exam together with an otolaryngologist, and yet others requiring the otolaryngologist to review each FEES exam after it is performed. We anticipate that, with the clinical adoption of pharyngeal HRM, the level and type of physician involvement will need to be determined through a process similar to the adoption of videofluorosopy and FEES. The development of state licensure guidelines will assist in clarifying these issues as well.

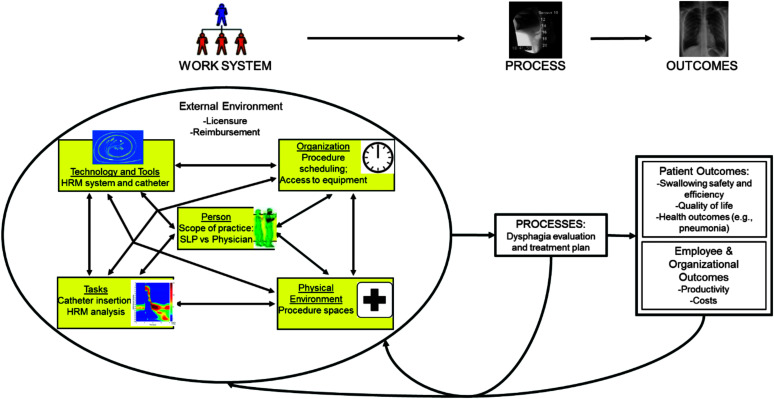

The variety of barrier themes identified, spanning from concerns at the individual provider level to those at the national level, indicates the need for a more comprehensive consideration of factors when implementing new interventions or technology in the health care setting. Specifically, human factors and systems engineering frameworks have been successfully applied to health care intervention design and implementation. The Systems Engineering Initiative for Patient Safety (SEIPS) is one such framework, which aims to comprehensively consider all elements of the health care system prior to changes in health care delivery. The overall goal is to identify barriers and facilitators to change in a proactive fashion and thus improve patient safety through reduced error. SEIPS has been successfully applied to both quality improvement interventions (e.g., infection control initiatives; Caya et al., 2015) and the adaption of new technologies (e.g., computerized provider order entry and electronic health records; Hoonakker et al., 2011). Using systems engineering models such as SEIPS can ensure comprehensive consideration of new interventions as it relates to the entire health care system and how it will impact both processes and desired outcomes (see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Adapted Systems Engineering Initiative for Patient Safety model. HRM = high-resolution manometry; SLP = speech-language pathologist. Adapted from Carayon et al. (2014) with permission from Elsevier.

In the case of HRM, our study identified various barriers that can be characterized using the SEIPS framework categories. For example, the theme of clinical workflow would be characterized under the SEIPS category of “Task” as clinicians need to find ways to integrate this procedure into their clinical workload but would also fall under “Organization,” as the introduction of HRM may impact staffing and/or patient scheduling on a clinic/hospital level. In addition to the specific system elements in SEIPS, it also accounts for the external environment that surrounds a health care system, which would cover our identified theme of reimbursement. This issue would obviously need to be addressed on a national level to ensure proper compensation for this procedure. Moving forward, it will be important for the field of speech-language pathology to approach interventions from a systems-level perspective to maximize patient benefits and clinician uptake while minimizing the potential for error and resultant patient harm. HRM can serve as an example for how mixed-methods approaches, starting with a rigorous qualitative examination of novel health care interventions, can reveal important provider and system-level barriers and facilitators.

There were several limitations to this study. The response rate of the survey was limited. Also, the survey and focus groups were tailored to SLPs with board certification in swallowing or DRS membership, assuming that they would be the most experienced and knowledgeable. It is possible that non–BCS-S SLPs might have different insights and views that can be informative to further implementation of pharyngeal HRM. Additionally, we did not examine how the perspectives of these groups of SLPs would change following structured training in pharyngeal HRM. Finally, given that these data were collected in 2015 and 2016, there may be more recent changes in the perceptions of SLPs regarding the clinical adoption of pharyngeal HRM that were not captured in this analysis. Despite these limitations, this work serves as a basis for the development of a clinical adoption framework for pharyngeal HRM that includes these professional and institutional level factors.

Conclusions

Through the qualitative methods employed in this study, the perceptions of SLPs related to professional and institutional factors influencing the clinical adoption of pharyngeal HRM became apparent. There is clear enthusiasm from BCS-S SLPs for further implementation and dissemination of this technology; however, a variety of systems-level issues must be addressed to support this process. National and state guidelines regarding the incorporation of this technology into the speech-language pathology scope of practice are necessary with a specific focus on the extent and type of physician involvement. Determination of the best processes for accessing pharyngeal HRM equipment and integration of pharyngeal HRM into current clinical workflow are needed. Finally, SLP and physician advocacy for the establishment of a billing code for pharyngeal HRM will be key to support reimbursement, which will support further clinical adoption. As more SLPs adopt pharyngeal HRM into their routine clinical practice, successful or ineffectual processes can be shared in order to improve and streamline the process for other clinicians.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grants R33 DC011130 (awarded to T. M. M.), T32 GM007507 and F31 DC015706 (awarded to C. A. J.), and 1K23AG057805-01A1 (awarded to N. M. R. P.) and the Clinical and Translational Science Award program, through the NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences Grant UL1TR002373. The article was partially prepared at the William S. Middleton Veteran Affairs Hospital in Madison, WI (GRECC Manuscript 005-2020). The views and content expressed in this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position, policy, or official views of the Department of Veteran Affairs, the U.S. Government, or the NIH. We would like to thank Rob Beattie, Suzan Abdelhalim, and Chelsea Walczak for assistance with data collection. Finally, we would like to thank the speech-language pathologists who completed the survey and participated in the focus groups.

Funding Statement

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grants R33 DC011130 (awarded to T. M. M.), T32 GM007507 and F31 DC015706 (awarded to C. A. J.), and 1K23AG057805-01A1 (awarded to N. M. R. P.) and the Clinical and Translational Science Award program, through the NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences Grant UL1TR002373. The article was partially prepared at the William S. Middleton Veteran Affairs Hospital in Madison, WI (GRECC Manuscript 005-2020).

References

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T [Google Scholar]

- Beynon-Davies, P. (1999). Human error and information systems failure: The case of the London ambulance service computer-aided despatch system project. Interacting With Computers, 11(6), 699–720. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0953-5438(98)00050-2 [Google Scholar]

- Bredenoord, A. J. , Fox, M. , Kahrilas, P. J. , Pandolfino, J. E. , Schwizer, W. , Smout, A. , & The International High Resolution Manometry Working Group. (2012). Chicago classification criteria of esophageal motility disorders defined in high resolution esophageal pressure topography (EPT). Neurogastroenterology and Motility, 24(Suppl. 1), 57–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2982.2011.01834.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carayon, P. , Schoofs Hundt, A. , Karsh, B. T. , Gurses, A. P. , Alvarado, C. J. , Smith, M. , & Flatley Brennan, P. (2006). Work system design for patient safety: The SEIPS model. Quality & Safety in Health Care, 15 (Suppl. 1), i50–i58. https://doi.org/10.1136/qshc.2005.015842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caya, T. , Musuuza, J. , Yanke, E. , Schmitz, M. , Anderson, B. , Carayon, P. , & Safdar, N. (2015). Using a systems engineering initiative for patient safety to evaluate a hospital-wide daily chlorhexidine bathing intervention. Journal of Nursing Care Quality, 30(4), 337–344. https://doi.org/10.1097/ncq.0000000000000129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang, I. C. , & Hsu, H. M. (2012). Predicting medical staff intention to use an online reporting system with modified unified theory of acceptance and use of technology. Telemedicine and e-Health, 18(1), 67–73. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2011.0048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J. , Liu, P. , Wang, Q. , Wu, L. , & Zhang, X. (2015). Influence of intensity-modulated radiation therapy on the life quality of patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cell Biochemistry and Biophysics, 73(3), 731–736. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12013-015-0638-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clouse, R. E. (2001). Topographic manometry: An evolving method for motility. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition, 32, S10–S11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compeau, D. R. , & Higgins, C. A. (1995). Application of social cognitive theory to training for computer skills. Information Systems Research, 6(2), 118–143. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.6.2.118 [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J. W. , & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. Management Information Systems Quarterly, 13(3), 319–340. https://doi.org/10.2307/249008 [Google Scholar]

- Dünnebeil, S. , Sunyaev, A. , Blohm, I. , Leimeister, J. M. , & Krcmar, H. (2010). Do German physicians want electronic health services? A characterization of potential adopters and rejectors in German ambulatory care. In Fred A., Filipe J., & Gamboa H. (Eds.), Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Health Informatics (Vol. 1, pp. 202–209). ScitePress; https://doi.org/10.5220/0002695602020209 [Google Scholar]

- Ferris, L. , Rommel, N. , Doeltgen, S. , Scholten, I. , Kritas, S. , Abu-Assi, R. McCall, L. , Seiboth, G. , Lowe, K. , Moore, D. , Faulks, J. , & Omari, T. (2016). Pressure-flow analysis for the assessment of pediatric oropharyngeal dysphagia. The Journal of Pediatrics, 177, 279–285.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.06.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein, M. , & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Addison-Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Getty, R. L. , & Getty, J. M. (1999). Ergonomics oriented to processes becomes a tool for continuous improvement. International Journal of Occupational Safety and Ergonomics, 5(2), 161–194. https://doi.org/10.1080/10803548.1999.11076417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammer, M. J. , Jones, C. A. , Mielens, J. D. , Kim, C. H. , & McCulloch, T. M. (2014). Evaluating the tongue-hold maneuver using high-resolution manometry and electromyography. Dysphagia, 29(5), 564–570. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-014-9545-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiss, S. G. , & Postma, G. N. (2003). Fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing. The Laryngoscope, 113(8), 1386–1393. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005537-200308000-00023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoonakker, P. L. , Cartmill, R. S. , Carayon, P. , & Walker, J. M. (2011). Development and psychometric qualities of the SEIPS survey to evaluate CPOE/EHR implementation in ICUs. International Journal of Healthcare Information Systems, 6(1), 51–69. https://doi.org/10.4018/jhisi.2011010104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, H.-F. , & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, C. A. , Forgues, A. L. , Rogus-Pulia, N. M. , Orne, J. , Macdonald, C. L. , Connor, N. P. , & McCulloch, T. M. (2019). Correlates of early pharyngeal high-resolution manometry adoption in expert speech-language pathologists. Dysphagia, 34(3), 325–332. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-018-9941-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, C. A. , Rogus-Pulia, N. M. , Forgues, A. L. , Orne, J. , Macdonald, C. L. , Connor, N. P. , & McCulloch, T. M. (2019). SLP-perceived technical and patient-centered factors associated with pharyngeal high-resolution manometry. Dysphagia, 34(2), 170–178. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-018-9954-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jungheim, M. , & Ptok, M. (2018). High-resolution manometry of pharyngeal swallowing dynamics. HNO, 66(7), 543–549. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00106-017-0365-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, C. K. , Ryu, J. S. , Song, S. H. , Koo, J. H. , Lee, K. D. , Park, H. S. , Oh, Y. , & Min, K. (2015). Effects of head rotation and head tilt on pharyngeal pressure events using high resolution manometry. Annals of Rehabilitation Medicine, 39(3), 425–431. https://doi.org/10.5535/arm.2015.39.3.425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knigge, M. A. , Marvin, S. , & Thibeault, S. L. (2019). Safety and tolerability of pharyngeal high-resolution manometry. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 28(1), 43–52. https://doi.org/10.1044/2018_AJSLP-18-0039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knigge, M. A. , & Thibeault, S. (2016). Relationship between tongue base region pressures and vallecular clearance. Dysphagia, 31(3), 391–397. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-015-9688-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knigge, M. A. , Thibeault, S. , & McCulloch, T. M. (2014). Implementation of high-resolution manometry in the clinical practice of speech language pathology. Dysphagia, 29(1), 2–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-013-9494-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger, R. A. , & Casey, M. A. (2009). Focus groups: A practical guide for applied research. SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, T. H. , Lee, J. S. , Hong, S. J. , Lee, J. S. , Jeon, S. R. , Kim, W. J. , Cho, H. Y. , Kim, J.-O. , Kim, M.-Y. , & Kwon, S. H. (2014). Impedance analysis using high-resolution impedance manometry facilitates assessment of pharyngeal residue in patients with oropharyngeal dysphagia. Journal of Neurogastroenteroly and Motility, 20(3), 362–370. https://doi.org/10.5056/jnm14007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, J. , Talaei-Khoei, A. , Seale, H. , Ray, P. , & Macintyre, C. R. (2013). Health care provider adoption of eHealth: Systematic literature review. Interactive Journal of Medical Research, 2(1), e7 https://doi.org/10.2196/ijmr.2468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L. , Miguel Cruz, A. , Rios Rincon, A. , Buttar, V. , Ranson, Q. , & Goertzen, D. (2015). What factors determine therapists' acceptance of new technologies for rehabilitation—A study using the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT). Disability and Rehabilitation, 37(5), 447–455. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2014.923529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May, N. H. , Davidson, K. W. , Pearson, W. G., Jr. , & O'Rourke, A. K. (2020). Pharyngeal swallowing mechanics associated with upper esophageal sphincter pressure wave. Head and Neck, 42(3), 467–475. https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.26029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, J. P. , Jones, C. A. , Walczak, C. C. , & McCulloch, T. M. (2016). Three-dimensional manometry of the upper esophageal sphincter in swallowing and nonswallowing tasks. The Laryngoscope, 126(11), 2539–2545. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.25957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, R. M. , & Groher, M. E. (1993). Speech-language pathology and dysphagia: A brief historical perspective. Dysphagia, 8(3), 180–184. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01354536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore, G. C. , & Benbasat, I. (1991). Development of an instrument to measure the perceptions of adopting an information technology innovation. Information Systems Research, 2(3), 192–222. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.2.3.192 [Google Scholar]

- Omari, T. I. , Ciucci, M. , Gozdzikowska, K. , Hernandez, E. , Hutcheson, K. , Jones, C. , Maclean, J. , Nativ-Zeltez, N. , Plowman, E. , Rogus-Paulia, N. , Rommel, N. , & O'Rourke, A. (2019). High-resolution pharyngeal manometry and impedance: Protocols and metrics—recommendations of a high-resolution pharyngeal manometry international working group. Dysphagia, 35, 281–295. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-019-10023-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahimpour, M. , Lovell, N. H. , Celler, B. G. , & McCormick, J. (2008). Patients' perceptions of a home telecare system. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 77(7), 486–498. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2007.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regan, J. (2020). Impact of sensory stimulation on pharyngo-esophageal swallowing biomechanics in adults with dysphagia: A high-resolution manometry study. Advance online publication. Dysphagia. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-019-10088-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu, J. S. , Park, D. H. , & Kang, J. Y. (2015). Application and interpretation of high-resolution manometry for pharyngeal dysphagia. Journal of Neurogastroenteroly and Motility, 21(2), 283–287. https://doi.org/10.5056/15009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu, J. S. , Park, D. H. , Oh, Y. , Lee, S. T. , & Kang, J. Y. (2016). The effects of bolus volume and texture on pharyngeal pressure events using high-resolution manometry and its comparison with videofluoroscopic swallowing study. Journal of Neurogastroenteroly and Motility, 22(2), 231–239. https://doi.org/10.5056/jnm15095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suh, J. H. , Park, D. , Kim, I. S. , Kim, H. , Shin, C. M. , & Ryu, J. S. (2019). Feasibility of high-resolution manometry for decision of feeding methods in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Medicine (Baltimore), 98(23), e15781 https://doi.org/10.1097/md.0000000000015781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, S. , & Todd, P. A. (1995). Understanding information technology usage: A test of competing models. Information Systems Research, 6(2), 144–176. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.6.2.144 [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, R. L. , Higgins, C. A. , & Howell, J. M. (1991). Personal computing: Toward a conceptual model of utilization. Management Information Systems Quarterly, 15(1), 125–143. https://doi.org/10.2307/249443 [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesan, P. , Sole, K. , Tang, C. , Macfarlane, J. T. , & Finch, R. G. (1993). Oropharyngeal production of pneumococcal capsular antigen and the potential for contamination of expectorated sputum samples in pneumococcal pneumonia. Epidemiology and Infection, 110(3), 621–631. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268800051049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh, V. , Morris, M. G. , Davis, G. B. , & Davis, F. D. (2003). User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. Management Information Systems Quarterly, 27(3), 425–478. https://doi.org/10.2307/30036540 [Google Scholar]

- Whitten, P. , Holtz, B. , & Nguyen, L. (2010). Keys to a successful and sustainable telemedicine program. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care, 26(2), 211–216. https://doi.org/10.1017/s026646231000005x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, J. R. (2000). Fundamentals of ergonomics in theory and practice. Applied Ergonomics, 31(6), 557–567. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0003-6870(00)00034-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winiker, K. , Gillman, A. , Guiu Hernandez, E. , Huckabee, M. L. , & Gozdzikowska, K. (2019). A systematic review of current methodology of high resolution pharyngeal manometry with and without impedance. European Archives of Otorhinolaryngology, 276(3), 631–645. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-018-5240-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]