Abstract

This cross-sectional study analyzes characteristics associated with posttraumatic stress disorder in patients after severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) may occur in individuals who have experienced a traumatic event. Previous coronavirus epidemics were associated with PTSD diagnoses in postillness stages, with meta-analytic findings indicating a prevalence of 32.2% (95% CI, 23.7-42.0).1 However, information after severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is piecemeal. We aimed at filling this gap by studying a group of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) who sought treatment at the emergency department, most of whom required hospitalization, eventually recovered, and were subsequently referred to a postacute care service for multidisciplinary assessment.

Methods

A total of 381 consecutive patients who presented to the emergency department with SARS-CoV-2 and recovered from COVID-19 infection were referred for a postrecovery health check to a postacute care service established April 21, 2020, at the Fondazione Policlinico Universitario Agostino Gemelli IRCCS in Rome, Italy. Patients were offered a comprehensive and interdisciplinary medical and psychiatric assessment, detailed elsewhere,2 which included data on demographic, clinical, psychopathological, and COVID-19 characteristics. Trained psychiatrists diagnosed PTSD using the criterion-standard Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5), reaching a Cohen κ interrater reliability of 0.82. To meet PTSD criteria, in addition to traumatic event exposure (criterion A), patients must have had at least 1 DSM-5 criterion B and C symptom and at least 2 criterion D and E symptoms. Criteria F and G must have been met as well. Additional diagnoses were made through the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5. Participants provided written informed consent, and the study was approved by the Università Cattolica and Fondazione Policlinico Gemelli IRCCS Institutional Ethics Committee.

Data for patients with and without PTSD were compared with the χ2 test for nominal variables and one-way analysis of variance for continuous variables. Factors significantly associated with PTSD were subjected to a binary logistic regression. P values were 2-tailed, and significance was set at a P value less than .05. Analyses were performed using R version 4 0.0 (The R Foundation).

Results

From April 21 to October 15, 2020, the postacute care service assessed 381 White patients who had recovered from COVID-19 infection within 30 to 120 days, 166 (43.6%) of whom were women. The mean (SD; range) age was 55.26 (14.86; 18-89). During acute COVID-19 illness, most patients were hospitalized (309 of 381 [81.1%]), with a mean (SD) length of hospital stay of 18.41 (17.27) days.

PTSD was found in 115 participants (30.2%). In the total sample, additional diagnoses were depressive episode (66 [17.3%]), hypomanic episode (3 [0.7%]), generalized anxiety disorder (27 [7.0%]), and psychotic disorders (1 [0.2%]). Patients with PTSD were more frequently women (64 [55.7%]), reported higher rates of history of psychiatric disorders (40 [34.8%]) and delirium or agitation during acute illness (19 [16.5%]), and presented with more persistent medical symptoms in the postillness stage (more than 3 symptoms, 72 [62.6%]) (Table). Logistic regression specifically identified sex (Wald1 = 4.79; P = .02), delirium or agitation (Wald1 = 5.14; P = .02), and persistent medical symptoms (Wald2 = 12.46; P = .002) as factors associated with PTSD.

Table. Characteristics of Patients With and Without Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) After Severe Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19).

| Characteristic | No. (%; 95% CI) | Statistical test | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (N = 381) | Without PTSD (n = 266) | With PTSD (n = 115) | |||

| Demographic and clinical characteristics | |||||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 55.26 (14.86) | 56.23 (15.97) | 53.01 (11.65) | F1 = 3.78 | .05 |

| Female | 166 (43.6; 38.5-48.7) | 102 (38.3; 32.5-44.5) | 64 (55.7; 46.1-64.9) | χ21 = 9.78 | .002 |

| Education, mean (SD), y | 14.36 (5.35) | 14.32 (5.97) | 14.45 (3.52) | F1 = 0.04 | .82 |

| Married | 229 (60.1; 55.0-65.1) | 153 (57.5; 51.3-63.5) | 76 (66.1; 56.7-74.7) | χ21 = 2.45 | .11 |

| BMI, mean (SD)a | 26.22 (4.42) | 25.96 (4.37) | 26.84 (4.48) | F1 = 3.17 | .07 |

| Smoker status | |||||

| Never | 183 (48.0; 42.9-53.2) | 123 (46.2; 40.1-52.4) | 60 (52.2; 42.7-61.6) | χ22 = 1.41 | .49 |

| Active | 41 (10.8; 7.8-14.3) | 31 (11.7; 8.1-16.1) | 10 (8.7; 4.2-15.4) | ||

| Former | 157 (41.2; 36.2-46.3) | 112 (42.1; 36.1-48.3) | 45 (39.1; 30.2-48.7) | ||

| Regular physical activity | 220 (57.7; 52.6-62.8) | 158 (59.4; 53.2-65.4) | 62 (53.9; 44.4-63.2) | χ21 = 0.99 | .32 |

| Previous history of psychiatric disorders | 95 (24.9; 20.4-29.3) | 55 (20.7; 16.0-26.0) | 40 (34.8; 26.1-44.2) | χ21 = 8.53 | .003 |

| Family history of psychiatric disorders | 84 (22.0; 18.0-26.6) | 54 (20.3; 15.6-25.6) | 30 (26.1; 18.3-35.1) | χ21 = 1.56 | .21 |

| Childhood trauma (CTQ total score), mean (SD) | 40.55 (8.93) | 40.90 (9.13) | 39.75 (8.43) | F1 = 1.07 | .30 |

| Acute COVID-19 characteristics | |||||

| Intensive care unit admission | 65 (17.1; 13.4-21.2) | 42 (15.8; 11.6-20.7) | 23 (20.0; 13.1-28.5) | χ21 = 1.00 | .31 |

| Oxygen therapy | 189 (49.6; 44.5-54.7) | 134 (50.4; 44.2-56.5) | 55 (47.8; 38.4-57.3) | χ21 = 0.20 | .64 |

| Noninvasive ventilation | 43 (11.3; 8.3-15.0) | 25 (9.4; 6.2-13.6) | 18 (15.7; 9.6-23.8) | χ21 = 3.20 | .07 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 29 (7.7; 5.2-10.8) | 16 (6.0; 3.5-9.6) | 13 (11.4; 6.2-18.7) | χ21 = 3.24 | .07 |

| Delirium/agitationb | 36 (9.4; 6.7-12.8) | 17 (6.4; 3.8-10.0) | 19 (16.5; 10.3-24.6) | χ21 = 9.63 | .002 |

| Hospitalization | 309 (81.1; 76.8-85.0) | 217 (81.6; 76.5-86.2) | 92 (80.0; 71.3-86.8) | χ21 = 0.13 | .71 |

| Length of hospital stay (if applicable), mean (SD), d | 18.41 (17.27) | 17.71 (15.04) | 20.00 (21.53) | F1 = 1.09 | .29 |

| Post–COVID characteristics | |||||

| Time since symptom onset, mean (SD), d | 96.81 (44.30) | 94.56 (42.56) | 102.01 (47.88) | F1 = 2.28 | .13 |

| Persistent COVID-19 symptoms | |||||

| None | 75 (19.7; 15.8-24.0) | 63 (23.7; 18.7-29.3) | 12 (10.4; 5.5-17.5) | χ22 = 22.03 | <.001 |

| 1 or 2 | 135 (35.4; 30.6-40.5) | 104 (39.1; 33.2-45.2) | 31 (27.0; 19.1-36.0) | ||

| ≥3 | 171 (44.9; 39.8-50.0) | 99 (37.2; 31.4-43.3) | 72 (62.6; 53.1-71.5) | ||

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CTQ, childhood trauma questionnaire; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder.

Body mass index calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

Assessed through the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM).

Discussion

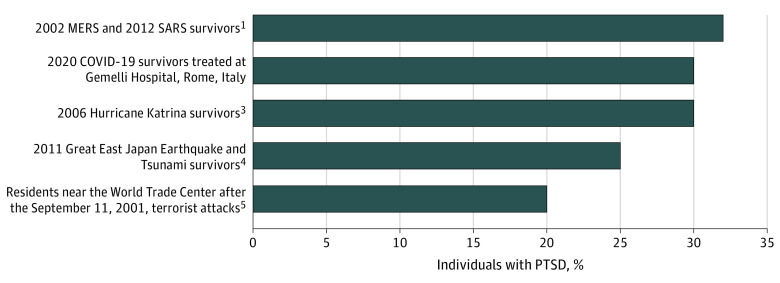

This cross-sectional study found a PTSD prevalence of 30.2% after acute COVID-19 infection, which is in line with findings in survivors of previous coronavirus illnesses1 compared with findings reported after other types of collective traumatic events (Figure).3,4,5 Associated characteristics were female sex, which has been extensively described as a risk factor for PTSD,1,3,5 history of psychiatric disorders, and delirium or agitation during acute illness. In the PTSD group, we also found more persistent medical symptoms, often reported by patients after recovery from severe COVID-19.6

Figure. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) After COVID-19 Infection and Other Collective Traumatic Events.

MERS indicates Middle East respiratory syndrome; SARS, severe acute respiratory syndrome.

This study had limitations, including the relatively small sample size and cross-sectional design, as PTSD symptom rates may vary over time. Furthermore, this was a single-center study that lacked a control group of patients attending the emergency department for other reasons. Further longitudinal studies are needed to tailor therapeutic interventions and prevention strategies.

References

- 1.Rogers JP, Chesney E, Oliver D, et al. Psychiatric and neuropsychiatric presentations associated with severe coronavirus infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis with comparison to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(7):611-627. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30203-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Landi F, Gremese E, Bernabei R, et al. ; Gemelli Against COVID-19 Post-Acute Care Study Group . Post-COVID-19 global health strategies: the need for an interdisciplinary approach. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2020;32(8):1613-1620. doi: 10.1007/s40520-020-01616-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Galea S, Brewin CR, Gruber M, et al. Exposure to hurricane-related stressors and mental illness after Hurricane Katrina. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(12):1427-1434. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.12.1427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li X, Aida J, Hikichi H, Kondo K, Kawachi I. Association of postdisaster depression and posttraumatic stress disorder with mortality among older disaster survivors of the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(12):e1917550. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.17550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Galea S, Ahern J, Resnick H, et al. Psychological sequelae of the September 11 terrorist attacks in New York City. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(13):982-987. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa013404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carfì A, Bernabei R, Landi F; Gemelli Against COVID-19 Post-Acute Care Study Group . Persistent symptoms in patients after acute COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;324(6):603-605. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.12603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]