Abstract

Background

Neonatal mortality is a major contributor worldwide to the number of deaths in children under 5 years of age. The primary objective of this study was to assess the overall mortality rate of babies with a birth weight equal or below 1500 g in a neonatal unit at a tertiary hospital in the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. Furthermore, different maternal-related and infant-related factors for higher mortality were analysed.

Methods

This is a prospective cohort study which included infants admitted to the neonatal wards of the hospital within their first 24 hours of life and with a birth weight equal to or below 1500 g. Mothers who consented answered a questionnaire to identify factors for mortality.

Results

173 very low birth weight (VLBW) infants were recruited in the neonatal department between November 2017 and December 2018, of whom 55 died (overall mortality rate 32.0%). Twenty-three of the 44 infants (53,5%) with a birth weight below 1000 g died during the admission. One hundred and sixty-one mothers completed the questionnaire and 45 of their babies died.

Main factors associated with mortality were lower gestational age and lower birth weight. Need for ventilator support and sepsis were associated with higher mortality, as were maternal factors such as HIV infection and age below 20 years.

Conclusion

This prospective study looked at survival of VLBW babies in an underprivileged part of the Eastern Cape of South Africa. Compared with other public urban hospitals in the country, the survival rate remains unacceptably low. Further research is required to find the associated causes and appropriate ways to address these.

Keywords: neonatology, mortality

What is known about the subject?

The perinatal mortality rate in sub-Saharan Africa is about 30 per 1000 live births. Preterm and very low birthweight (VLBW) infants account for a large number of neonatal deaths. Although South Africa is considered an upper-middle-income country by the World Bank, survival of VLBW varies greatly dependent on resources. Survival of VLBW infants in studies from South Africa are about 75%.

What this study adds?

Survival of VLBW infants fulfilling inclusion criteria for the study was 68%. Survival for VLBW babies in our setting is lower than in other South African urban settings.

Introduction

Despite improved survival rates of neonates worldwide, the survival of preterm and low birthweight babies is still a challenge, especially in middle- and low-income countries.1–4

In 2018, WHO described a worldwide increase of babies born prematurely over the last two decades. The incidence has been estimated between 5% and 18% of all life births.5 6 The prevalence of babies born with a very low birth weight (VLBW) varies between different countries. For example, in one South African study, the prevalence was 3%, while in the USA it lies between 1.23% and 1.43%.7–9 Furthermore, prematurity and low birth weight have been identified as the leading causes of mortality in children less than 5 years of age.5 10–12 It is also well known that neonatal mortality for VLBW infants varies considerably among high-income and low-middle income countries: a mortality rate of 15% is found in the USA,13 20% by the Vermont Oxford network,14 29.1% in Iran,3 28.2% in South Korea,11 32% in the Eastern Mediterranean Region15 and 24.6% in India.16 Some single centres worldwide show a lower mortality rate with 9.5%, 12.4%, 13.0% and 17.2% in single centres in Singapore, Taiwan, Hong-Kong, Saudi-Arabia, respectively.14 17–19

In South Africa, neonatal mortality accounted for 32% of the under 5 mortality rate.4 20 21 A recent study illustrated survival rates of VLBW neonates between different hospitals in the Western Cape Province of South Africa characterised by unrestricted or restricted resources.22 The team found a significant difference with a survival rate of 84.4% and 70.4%, respectively.22 Kalimba and Ballot23 studied the survival rate of extremely low birth weight (ELBW) babies (babies weighing less than 1000 g at birth) born between 2006 and 2010 in Johannesburg and found that only 25.6% of babies born with a birth weight of less than 900 g survived their hospital stay, with birth weight and gestational age being the strongest predictors for survival. A newer retrospective cross-sectional South African study found an overall survival rate in VLBW babies (500–1499 g) of 75.7%.24

However, there are also other known contributory factors, which can be divided into neonate-related or maternal-related risk factors. Examples of neonate-related risk factors studied in the literature include low Apgar scores, hyaline membrane disease (HMD), intubation and mechanical ventilation, sepsis and haemodynamic instability.25 26 Maternal or obstetric risk factors include eclampsia, alcohol consumption, smoking, low socioeconomic status, scarce antenatal care and human immuno deficiency virus (HIV) infection.18 23 27 28 Several studies suggest an increased risk of premature labour in mothers taking antiretroviral treatment (ART) for HIV infection during pregnancy,29–32 while others did not find a relationship.33 This is noteworthy, as 30.8% of pregnant women in South Africa tested positive for HIV in 2015, and are put on treatment as soon as the infection is diagnosed.34 35

The primary aim of this study was to research neonatal mortality of VLBW infants admitted to the neonatal unit in a hospital in a mixed urban and rural setting in the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa. Second, the association between death and different maternal and neonatal factors were explored.

Setting

Frere Hospital is a large (885 beds) public tertiary hospital in East London in the Eastern Cape Province in South Africa, with a seven-bed paediatric intensive care unit (PICU), which cares for neonates and paediatric medical and surgical patients. Because of this very limited PICU access, babies with a weight below 1000 g are not provided with invasive ventilatory support due to poor survival. These babies will receive surfactant if needed and continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) ventilation is available for six infants in the high care neonatal unit, which can cater for 12 infants altogether. This high care ward is constantly above capacity, often having to care for up to 20 infants, when there is only adequate space for the above-mentioned 12 neonates. Infants with a birth weight over 1000 g will be taken to PICU and receive invasive ventilation if needed and if space is available for them. Stable neonates with a weight of more than 1000 g are referred to the general nursery ward, where they receive kangaroo mother care (KMC) in the ward and, if necessary, intravenous fluids and/or antibiotics and oxygen. Once clinically stable, off oxygen support, tolerating full enteral feeds and weighing more than 1500 g, infants will be transferred to the KMC ward until mothers are competent in caring for their baby and the weight has increased to at least 1700 g. Some stable babies might be transferred to their regional hospital once their weight has reached 1500 g.

Frere Hospital is the tertiary neonatal and obstetric referral centre for obstetric units and for surrounding district hospitals in the middle part of the Eastern Cape Province. Some referrals centres are more than 300 km away. These areas were deprived of adequate infrastructure during the Apartheid regimen and are still one of the most under-resourced and insufficiently managed parts of South Africa.

Materials and methods

This was a prospective cohort study. All babies born at the hospital, or admitted within the first 24 hours of life into the neonatal unit, with a birth weight equal or below 1500 g and without any life-threatening malformations were included. Neonates who were admitted to the neonatal ward or PICU beyond 24 hours of life were excluded as it was not possible to get sufficient information on those mother–infant pairs. Mothers were then approached for consent to include their data. The recruitment period lasted from December 2017 to November 2018.

After receiving written consent from the mothers, data concerning mother and child during the prenatal, perinatal and neonatal period were collected from the maternal and neonatal case records, as well as from a questionnaire filled in with the mother (see online supplemental file). The babies were followed up until discharge or death. All babies received standard care during this period, as outlined above.

bmjpo-2020-000918supp001.pdf (72.8KB, pdf)

Gestational age was determined by either an early ultrasound or by applying the Ballard gestational age scoring system. It is estimated that about 70% of the babies admitted to our neonatal wards will have had their gestational age assessed by early ultrasound. The different variables were defined as follows: a persistent ductus arteriosus as identified by echocardiogram; HMD by the presence respiratory distress; fractional inspired oxygen requirement above 40% followed by a confirmatory blood gas and typical X-ray signs; sepsis as clinical signs confirmed with a positive blood, urine or cerebrospinal fluid culture and/or raised C reactive protein taken at least 24 hours apart; normal weight gain was determined when weight loss after birth did not exceed more than 10% and birth weight was regained within 10–14 days of life; intracranial haemorrhage (ICH) was diagnosed with cranial ultrasound, which was only performed in clinically unstable infants with the clinical suspicion of ICH; resuscitation at birth included mask or invasive ventilation with or without cardiac compressions and medication.

Patient and public involvement

The patients, being mother–newborn pairs, were not involved in the study design. Every new-born admitted in our wards during the study period was assessed for inclusion in our study, no recruitment from the patient’s side was necessary. The results of this study are verbally communicated to the mothers and/or caretakers.

Statistical analysis

Demographic data are presented as frequencies (percentages) for categorical data, and as means (SD) for continuous data. To test for association between the outcome variable (mortality) and the predictor variables, a log binomial regression model was used. In order to investigate the relationship between hypertension and mortality in babies in more detail, a multiple regression model was used, adjusting for IUGR and gestational age. The standard for significance for all analyses was a p<0.05. Data were analysed using STATA V.15.

Results

During the study period, 4342 babies were born in the hospital, 4210 of these were live births and 231 (5.3%) were born with a birth weight between 500 g and 1500 g. Of those 231 VLBW infants, only 173 met the inclusion criteria for the study. Of those, 55 died during admission, resulting in an overall mortality rate of 31.8% (95% CI 25.2% to 39.2%) for VLBW infants admitted to our unit.

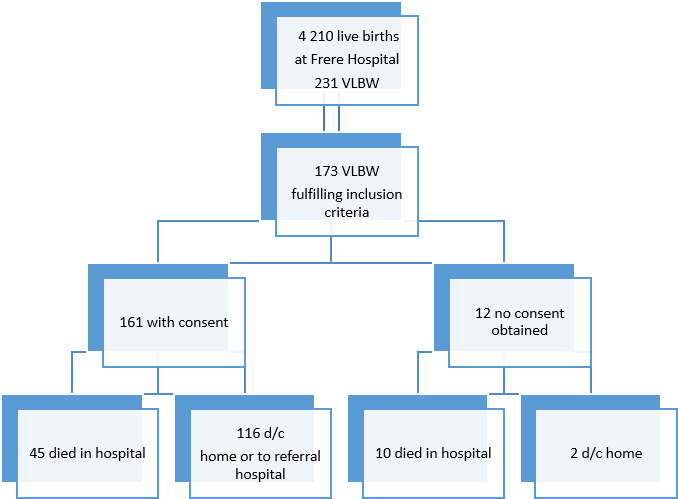

One hundred and sixty-one of the 173 VLBW infants were successfully recruited (caregivers gave informed consent) during the study period. Forty-five (28.0%) of those babies died before discharge and 116 (72.0%) were discharged home or referred to a peripheral hospital if they had reached a weight above 1500 g. Forty-four of the 161 babies were born with a birth weight below 1000 g, of those 23 (53,5%) did not survive until discharge. For an overview of recruitment and numbers of participants, see figure 1. All 116 babies discharged from hospital received a follow-up date for the high-risk clinic.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of recruitment numbers of cohort. VLBW: very low birth weight. d/c : discharged

Demographics

The maternal age ranged between 14 and 46 years. Fifty-eight (36.0%) mothers had HIV infection diagnosed before or during the pregnancy or at birth. Thirty-nine of them (67.2%) had been on ART at delivery for more than 4 weeks. Sixteen (27.6%) mothers had been on ART for less than 4 weeks or were not on treatment at all when giving birth, and their babies were thus considered at high risk for HIV transmission and treated accordingly. For other variables please see table 1.

Table 1.

Maternal demographic variables

| Variables | Category | Overall* | Neonates who died† |

| n=161 (%) | n=45 (%) | ||

| Age of mother (years) | ≤20 | 30 (18.6) | 10 (33.3) |

| >20 | 131 (81.4) | 35 (26.7) | |

| Marital status | Married/stable relationship | 91 (57.6) | 24 (26.4) |

| No partner | 67 (42.4) | 18 (26.8) | |

| Substance abuse | Yes | 13 (8.1) | 4 (30.8) |

| No | 147 (91.9) | 40 (27.2) | |

| Employment | Yes | 24 (15.1) | 5 (20.8) |

| No | 135 (84.9) | 39 (28.9) | |

| Electricity at home | Yes | 143 (89.9) | 41 (28.7) |

| No | 16 (10.1) | 3 (18.8) | |

| Running water at home | Yes | 99 (62.3) | 28 (28.3) |

| No | 60 (37.7) | 16 (26.7) | |

| Refrigerator at home | Yes | 109 (68.6) | 32 (29.4) |

| No | 50 (31.5) | 12 (24.0) | |

| Education level | Primary | 72 (45.6) | 22 (30.6) |

| Secondary/tertiary | 86 (54.4) | 21 (24.4) | |

| HIV-infection | Yes | 58 (36.5) | 14 (24.1) |

| No | 101 (63.5) | 30 (29.7) | |

| Antiretroviral Treatment (ART) | Fixed dose combination (FDC) drug | 45 (93.8) | 10 (22.2) |

| Second line treatment | 2 (4.2) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Other | 1 (2.1) | 0 (0.0) |

*The overall number and percentage per risk factor.

†The number and percentage of babies who died per risk factor category. HIV: human immunodeficiency virus, ART: antiretroviral treatment, FDC: fixed dose combination.

Of the 161 babies included in the study, 96 were female (59.7%). Almost all HIV exposed babies (n=58) tested negative for HIV infection at birth with a negative birth HIV-PCR (n=55; 94.8%). Three babies, who died a few hours after birth, did not receive an HIV-PCR at birth and their status is therefore unknown. For other variables please see table 2.

Table 2.

Infant demographics variables

| Variables | Category | Overall* | Neonates who died† |

| n=161 (%) | n=45 (%) | ||

| Gender | Female | 96 (59.6) | 27 (28.1) |

| Male | 65 (40.4) | 18 (27.7) | |

| GA (weeks) | 25–32 | 78 (49.1) | 36 (46.2) |

| 33–37 | 81 (50.9) | 9 (11.1) | |

| HIV exposed | Yes | 58 (36.0) | 14 (24.1) |

| No | 103 (64.0) | 31 (30.1) | |

| Prevention of mother to child transmission (PMTCT) | Yes | 44 (27.3) | 11 (25.0) |

| No | 117 (72.7) | 34 (29.1) | |

| Birth weight (g) | ≤1000 g | 43 (26.7) | 23 (53.5) |

| >1000 g | 118 (73.3) | 22 (18.6) | |

| Born before arrival | Yes | 11 (6.8) | 2 (18.2) |

| No | 150 (93.2) | 43 (28.7) | |

| Mother not been to antenatal clinic (ANC) | Yes (no ANC) | 25 (15.5) | 8 (32.0) |

| No (ANC attended) | 136 (84.5) | 37 (27.2) | |

| intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) | Yes | 111 (69.8) | 23 (20.7) |

| No | 48 (30.2) | 21 (43.8) |

*The overall number and percentage per risk factor.

†The number and percentage of babies who died per risk factor category.

GA, gestational age; PMTCT, prevention of mother to child transmission; IUGR, intrauterine growth restriction.

Factors associated with in hospital mortality

Maternal associated factors for the univariate model:

Univariate regression analysis was used to examine the association between mortality and associated individual factors. Associated factors of infants dying while still in hospital were higher in babies of teenage mothers, mothers with illnesses and mothers on medication. Maternal hypertension and pre-eclampsia were associated with decreased mortality in the babies. Education level of the mother and other socioeconomic status factors were not significantly related to a higher mortality risk during admission in our study, with employment status only showing a trend towards significance (table 3).

Table 3.

Significant univariate associations between VLBW infant mortality and maternal-related factors

| Variables | Category | Risk Ratio (95% CI) | P value |

| Age of mother (years) | ≤20 vs>20 | 1.25 (1.07 to 1.45) | <0.01 |

| Hypertension | Yes vs no | 0.62 (0.49 to 0.77) | <0.01 |

| Pre-eclampsia | Yes vs no | 0.69 (0.57 to 0.82) | <0.01 |

| Other illnesses | Yes vs no | 1.34 (1.04 to 1.74) | 0.02 |

| Medication | Yes vs no | 0.43 (0.25 to 0.77) | <0.01 |

| Employment | Yes vs no | 0.72 (0.52 to 1.01) | 0.06 |

| Refrigerator at home | Yes vs no | 1.22 (1.01 to 1.48) | 0.04 |

VLBW, very low birth weight.

Other illnesses included malignancies, epilepsy, mental health disorders. Medication included all other medication besides ART Most maternal factors that were not significantly associated with mortality in the regression analysis are not shown in this table.

Neonatal-associated factors:

There were many significant neonatal-associated factors related to infant mortality, such as low gestational age (p<0.01), low birth weight (p<0.01), IUGR (p<0.01) and the need for resuscitation at birth (p<0.01) or during the hospital stay (p=0.01). Male gender was not associated with higher mortality risk (p=0.94; RR=1.0; 95% CI 0.7 to 1.5) (table 4).

Table 4.

Significant univariate associations between infant mortality and infant-related factors of VLBW infants

| Variables | Category | Risk Ratio (95% CI) | P value |

| Gender | Female vs Male | 1.02 (0.70 to 1.48) | 0.94 |

| GA (weeks) | 25–32 vs 33–37 | 4.15 (2.93 to 5.88) | <0.01 |

| HIV exposed | No vs yes | 1.25 (1.00 to 1.56) | 0.05 |

| Birth weight (g) | ≤1000 vs>1000 | 2.87 (2.08 to 3.96) | <0.01 |

| IUGR | Yes vs no | 0.47 (0.35 to 0.65) | <0.01 |

| Resuscitation at birth | Yes vs no | 4.45 (3.43 to 5.78) | <0.01 |

| Apgar 1 min | 0–6 vs 7–10 | 2.46 (1.99 to 3.05) | <0.01 |

| Apgar 5 min | 0–6 vs 7–10 | 2.42 (2.12 to 2.77) | <0.01 |

| HMD | Yes vs no | 2.03 (1.72 to 2.38) | <0.01 |

| Other illnesses | Yes vs no | 1.59 (1.20 to 2.09) | 0.01 |

| Oxygen support | Yes vs no | 9.68 (7.39 to 12.68) | <0.01 |

| Days on oxygen | 0–1 day vs >1 day | 1.44 (0.94 to 2.21) | 0.09 |

| Surfactant given | Yes vs no | 3.59 (2.77 to 4.65) | <0.01 |

| Weight gain | Yes vs no | 3.39 (2.21 to 5.19) | <0.01 |

| Sepsis | Yes vs no | 6.41 (3.78 to 10.88) | <0.01 |

| Intracranial haemorrhage (ICH) | Yes vs no | 5.19 (3.03 to 8.90) | <0.01 |

| Persistant ductus arteriosus PDA | No vs yes | 2.83 (1.47 to 5.47) | <0.01 |

| Resuscitation during stay | Yes vs no | 12.31 (5.85 to 25.88) | 0.01 |

Infant-related factors that were not significantly associated with mortality in the univariate regression analysis are not shown in this table, besides gender.

ANC, antenatal clinic; GA, gestational age; HMD, hyaline membrane disease; ICH, intracranial haemorrhage; IUGR, intrauterine growth restriction; Other, other problems like neonatal jaundice, hypoglycaemia, necrotising enterocolitis, hypothermia; PDA, persistent ductus arteriosus; VLBW, very low birth weight.

Multiple regression analysis

As could be seen in the univariate analysis, maternal hypertension was associated with decreased mortality in the babies. However, when adjusting for IUGR and gestational age in the multiple regression analysis, no significant association was found for maternal hypertension (p=0.28; RR=0.88; 95% CI 0.70 to 1.11), as shown in table 5.

Table 5.

Results of maternal and infant factors in multiple regression analysis

| Variables | Category | Risk ratio (95% CI) | P value |

| Hypertension | Yes vs no | 0.88 (0.70 to 1.11) | 0.28 |

| IUGR | Yes vs no | 1.88 (1.68 to 2.11) | 0.03 |

| GA (weeks) | 25–32 vs 33–37 | 3.80 (2.43 to 5.96) | <0.01 |

GA, gestational age; IUGR, intrauterine growth restriction.

Discussion

The prevalence of VLBW infants of all live birth in this single hospital study in the Eastern Cape province between December 2017 and November 2018 was 5.4%. This figure lies within the prevalence of 3%–7% reported worldwide,3 13 but is likely elevated due to the referrals from obstetric units and surrounding district hospitals.

Almost 32% of admitted VLBW neonates with inclusion criteria died before discharge. For infants with a birth weight of 1000 g or less this number rose to 60%, while the chance for survival of infants weighing 1000 g and up to 1500 g at birth was higher, with a mortality rate of 18.5%. Thus, the overall mortality rate is higher than the reported average of approximately 25% in major cities in South Africa,24 36 37 and much higher than in the hospitals with much greater resources from the Western Cape province.22 It is also much higher than in most hospitals in high-income countries where mortality rates for VLBW infants are as low as 9.5%–17.2%.14 17–19 38 39 The high mortality in our setting is most likely due to the scarcity of skilled healthcare workers, limited infrastructures, as well as a patient overloaded, resource-restricted system, as described.4 The data support that although South Africa is considered an upper-middle-income country by the World Bank, survival of VLBW varies greatly dependent on resources.22

Consistent with other studies examining the causes of mortality in VLBW babies, birth weight and low gestational age were predictors of neonatal mortality in our study population.18 23 26 35 Complications of prematurity, such as the development of HMD and the associated need for surfactant replacement therapy with ventilation was associated with a significantly increased risk of mortality, as reported in previous research.3 22 23 26 Other studies have shown that CPAP and/or surfactant replacement therapy reduce mortality in VLBW and/or preterm neonates with HMD.22 40 Unavailability of PICU beds and overcrowding in our high care unit with low nurse-infants’ ratio could explain why we were unable to find this benefit in our cohort.

Interestingly, our study did not find that the wide range of maternal factors found in other studies increasing in-hospital mortality of infants, including lack of antenatal care, maternal primiparity, mode of delivery or complications thereof.23 27 28 32

Although a substantial percentage (36%) of the babies were born to HIV infected mothers, and 13.8% (n=8) of those had not received any ART before giving birth, all HIV-PCR done were negative. This is encouraging, but further research is needed to investigate HIV transmission rates in VLBW babies in low-resource settings.34 35

There are several limitations to this study. Even though this was a prospective study, data collection was not exhaustive and some prenatal variables could not be explored due to lack of information. Also, due to staff shortage, ultrasound of the head was not performed routinely, but only in clinically suspicious situations, and thus intracranial pathologies might have been missed. Furthermore, this is a single hospital-based study, therefore, the number of VLBW cases is limited.

Conclusion

Our cohort shows a higher in-hospital mortality of VLBW infants compared with some other urban hospitals in South Africa. These findings indicate that the survival of VLBW and especially ELBW babies are still unacceptably low in this resource restricted public hospital. This is most likely caused by numerous factors, many of which have also been implicated in similar studies, but need to be further investigated in future research and appropriately addressed.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: IM’ contribution consisted of funding acquisition, study design, investigation, data curation, supervision and drafting the initial manuscript. NM contributed to study design, investigation, data curation and reviewing the manuscript. IK-M contributed to supervision, writing and reviewing the final manuscript. MM contributed to data curation and data analysis. EJ contributes to data curation and data analysis and writing and reviewing the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the South African Medical Research Council (SAMRC) Fund, grant number (086/2017). The sponsorship of the SAMRC Pilot Grant serves to encourage clinicians in rural South Africa to engage in research.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: Walter Sisulu University Human Research Ethics Committee 086/2017.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplemental information. The existing data are deidentified participants data of mother and infant. Data will be available from https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5073-5545.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

References

- 1.Almeida MFBde, Guinsburg R, Martinez FE. Fatores perinatais associados AO óbito precoce em prematuros nascidos NOS centros dA Rede Brasileira de Pesquisas Neonatais. J Pediatr 2008;84:300–7. 10.1590/S0021-75572008000400004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Basu S, Rathore P, Bhatia BD. Predictors of mortality in very low birth weight neonates in India. Singapore Med J 2008;49:556–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Afjeh S-A, Sabzehei M-K, Fallahi M, et al. Outcome of very low birth weight infants over 3 years report from an Iranian center. Iran J Pediatr 2013;23:579–87. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rhoda NR, Gebhardt GS, Kauchali SBP. Reducing neonatal deaths in South Africa. S Afr Med J 2018;3:S9–19. [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization Newborns: reducing mortality. World Heal Organ 2019:2018–21 http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs178/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haas DM Preterm birth. BMJ Clin Evid 2011;2011:1–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Velaphi SC, Mokhachane M, Mphahlele RM, et al. Survival of very-low-birth-weight infants according to birth weight and gestational age in a public hospital. S Afr Med J 2005;95:504–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mackay CA, Ballot DE, Cooper PA. Growth of a cohort of very low birth weight infants in Johannesburg, South Africa. BMC Pediatr 2011;11:50. 10.1186/1471-2431-11-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martin JA, Hamilton BE DP, Sutton PD. National Vital Statistics Reports Births : Final Data for 2013. Statistics 2015;64:1–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu L, Oza S, Hogan D, et al. Global, regional, and national causes of under-5 mortality in 2000-15: an updated systematic analysis with implications for the sustainable development goals. Lancet 2016;388:3027–35. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31593-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hahn W-H, Chang J-Y, Chang YS, et al. Recent trends in neonatal mortality in very low birth weight Korean infants: in comparison with Japan and the USA. J Korean Med Sci 2011;26:467–73. 10.3346/jkms.2011.26.4.467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chung SH, Bae CW. Improvement in the survival rates of very low birth weight infants after the establishment of the Korean neonatal network: comparison between the 2000s and 2010s. J Korean Med Sci 2017;32:1228–34. 10.3346/jkms.2017.32.8.1228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fanaroff AA, Stoll BJ, Wright LL, et al. Trends in neonatal morbidity and mortality for very low birthweight infants. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2007;196:147.e1–147.e8. 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chee YY, Wong MS, Wong RM, et al. Neonatal outcomes of preterm or very-low-birth-weight infants over a decade from Queen Mary Hospital, Hong Kong: comparison with the Vermont Oxford network. Hong Kong Med J 2017;23:381–6. 10.12809/hkmj166064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nayeri F, Emami Z, Mohammadzadeh Y, et al. Mortality and morbidity patterns of very low birth weight newborns in eastern Mediterranean region: a meta-analysis study. J Pediatr Rev 2018;7:67–76. 10.32598/jpr.7.2.67 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bansal A Comparison of outcome of very-low-birth-weight babies with developed countries: a prospective longitudinal observational study. J Clin Neonatol 2018;7:254 10.4103/jcn.JCN_76_18 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anand AJ, Sabapathy K, Sriram B, et al. Single center outcome of multiple births in the premature and very low birth weight cohort in Singapore. Am J Perinatol 2020. 10.1055/s-0040-1716482. [Epub ahead of print: 11 Sep 2020]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen S-D, Lin Y-C, Lu C-L, et al. Changes in outcome and complication rates of very-low-birth-weight infants in one tertiary center in southern Taiwan between 2003 and 2010. Pediatr Neonatol 2014;55:291–6. 10.1016/j.pedneo.2013.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Al Hazzani F, Al-Alaiyan S, Hassanein J, et al. Short-Term outcome of very low-birth-weight infants in a tertiary care hospital in Saudi Arabia. Ann Saudi Med 2011;31:581–5. 10.4103/0256-4947.87093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nannan N, Dorrington R, Laubscher R. Under-5 mortaliy statistics in South Africa: shedding some light on the trend and causes 1997-2007. South African medical Research Council 2012.

- 21.Bradshaw D, Dorrington R. Rapid mortality surveillance report 2011, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van Wyk L, Tooke L, Dippenaar R, et al. Optimal ventilation and surfactant therapy in very-low-birth-weight infants in resource-restricted regions. Neonatology 2020;117:217–24. 10.1159/000506987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kalimba EM, Ballot D. Survival of extremely low-birth-weight infants. S Afr J CH 2013;7:13–16. 10.7196/sajch.488 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tshehla RM, Chb MB, Sa DCH CM. Mortality and morbidity of very low-birthweight and extremely low-birthweight infants in a tertiary hospital in Tshwane 2019;13. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Terzic S, Heljic S. Assessing mortality risk in very low birth weight infants. Med Arh 2012;66:76–9. 10.5455/medarh.2012.66.76-79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.S. K, Kumar MS. Morbidity and mortality pattern of very low birth weight infants admitted in SNCU in a South Asian tertiary care centre. Int J Contemp Pediatrics 2018;5:720–5. 10.18203/2349-3291.ijcp20181025 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cupen K, Barran A, Singh V, et al. Risk Factors Associated with Preterm Neonatal Mortality: A Case Study Using Data from Mt. Hope Women’s Hospital in Trinidad and Tobago. Children 2017;4:108 10.3390/children4120108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vaahtera M, Kulmala T, Ndekha M, et al. Antenatal and perinatal predictors of infant mortality in rural Malawi. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2000;82:200F–4. 10.1136/fn.82.3.F200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Townsend C, Schulte J, Thorne C, et al. Antiretroviral therapy and preterm delivery-a pooled analysis of data from the United States and Europe. BJOG 2010;117:1399–410. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2010.02689.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van der Merwe K, Hoffman R, Black V, et al. Birth outcomes in South African women receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy: a retrospective observational study. J Int AIDS Soc 2011;14:42. 10.1186/1758-2652-14-42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Powis KM, Kitch D, Ogwu A, et al. Increased risk of preterm delivery among HIV-infected women randomized to protease versus nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor-based HAART during pregnancy. J Infect Dis 2011;204:506–14. 10.1093/infdis/jir307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Uthman OA, Nachega JB, Anderson J, et al. Timing of initiation of antiretroviral therapy and adverse pregnancy outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet HIV 2017;4:e21–30. 10.1016/S2352-3018(16)30195-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.González R, Rupérez M, Sevene E, et al. Effects of HIV infection on maternal and neonatal health in southern Mozambique: a prospective cohort study after a decade of antiretroviral drugs roll out. PLoS One 2017;12:1–11. 10.1371/journal.pone.0178134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.John V, Harper K. Hiv prevalence at birth in very low-birthweight infants. S Afr J CH 2020;14:129–32. 10.7196/SAJCH.2020.v14i3.01687 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Levin C, Le Roux DM, Harrison MC, et al. Hiv transmission to premature very low birth weight infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2017;36:860–2. 10.1097/INF.0000000000001611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ballot DE, Chirwa T, Ramdin T, et al. Comparison of morbidity and mortality of very low birth weight infants in a central hospital in Johannesburg between 2006/2007 and 2013. BMC Pediatr 2015;15:1–11. 10.1186/s12887-015-0337-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gibbs L, Tooke L, Harrison MC. Short-term outcomes of inborn v. outborn very-low-birth-weight neonates (<1 500 g) in the neonatal nursery at Groote Schuur Hospital, Cape Town, South Africa. S Afr Med J 2017;107:900–3. 10.7196/SAMJ.2017.v107i10.12463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Numerato D, Fattore G, Tediosi F, et al. Mortality and length of stay of very low birth weight and very preterm infants: a EuroHOPE study. PLoS One 2015;10:1–12. 10.1371/journal.pone.0131685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zile I, Ebela I, Rozenfelde IR. Risk factors associated with neonatal deaths among very low birth weight infants in Latvia. Curr Pediatr Res 2017;21:64–8. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Griffin JB, Jobe AH, Rouse D, et al. Evaluating WHO-recommended interventions for preterm birth: a mathematical model of the potential reduction of preterm mortality in sub-Saharan Africa. Glob Health Sci Pract 2019;7:215–27. 10.9745/GHSP-D-18-00402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjpo-2020-000918supp001.pdf (72.8KB, pdf)