Abstract

Background

Triglyceride-glucose (TyG) index was recently suggested to be a reliable surrogate marker of insulin resistance. We aim to investigate the associations between baseline and long-term TyG index with subsequent stroke and its subtypes in a community-based cohort.

Methods

A total of 97,653 participants free of history of stroke in the Kailuan Study were included. TyG index was calculated as ln (fasting triglyceride [mg/dL] × fasting glucose [mg/dL]/2). Baseline TyG index was measured during 2006–2007. Updated cumulative average TyG index used all available TyG index from baseline to the outcome events of interest or the end of follow up. The outcome was the first occurrence of stroke, including ischemic stroke, intracerebral hemorrhage and subarachnoid hemorrhage. The associations of TyG index with outcomes were explored with Cox regression.

Results

During a median of 11.02 years of follow-up, 5122 participants developed stroke of whom 4277 were ischemic stroke, 880 intracerebral hemorrhage, and 144 subarachnoid hemorrhage. After adjusting for confounding variables, compared with participants in the lowest quartile of baseline TyG index, those in the third and fourth quartile were associated with an increased risk of stroke (adjusted hazard ratio [HR] 1.22, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.12–1.33, and adjusted HR 1.32, 95% CI 1.21–1.44, respectively, P for trend < 0.001). We also found a linear association between baseline TyG index with stroke. Similar results were found for ischemic stroke. However, no significant associations were observed between baseline TyG index and risk of intracranial hemorrhage. Parallel results were observed for the associations of updated cumulative average TyG index with outcomes.

Conclusions

Elevated levels of both baseline and long-term updated cumulative average TyG index can independently predict stroke and ischemic stroke but not intracerebral hemorrhage in the general population during an 11-year follow-up.

Keywords: Insulin resistance, Triglyceride-glucose index, Stroke

Background

Insulin resistance is a hallmark of metabolic syndrome and is considered to be one of the important risk factors of stroke [1, 2]. A reliable surrogate marker of insulin resistance was suggested to be the triglyceride-glucose (TyG) index, which was calculated as ln (fasting triglyceride [mg/dL] × fasting glucose [mg/dL]/2) [3, 4]. Some studies showed an association between TyG index and incidence of cardiovascular diseases [5, 6]. Current data about associations between TyG index and stroke are limited. A cohort study showed that higher levels of TyG index were not associated with higher risk of cerebrovascular disease, but it indicated that participants with higher levels of TyG index tended to have higher risk of events [7]. Recently, a cross-sectional study showed that the elevated levels of TyG index was associated with a higher risk of ischemic stroke in a general population [8]. In addition, the relationships of TyG index with the risk of future stroke subtypes are uncertain. Therefore, we aim to investigate the associations between TyG index and the occurrence of stroke and its subtypes in the Kailuan Study. We further evaluated the associations between updated cumulative average TyG index and stroke and its subtypes in the Kailuan Study.

Methods

Study design and participants

The Kailuan Study is a prospective cohort study conducted in the Kailuan community in Tangshan City, China [9]. The detailed design of the Kailuan study have been described previously [10]. Briefly, from June 2006 to October 2007, a total of 101,510 participants aged from 18 to 98 years in the community were enrolled in the Kailuan study and underwent a comprehensive biennial health examination at the Kailuan General Hospital. To minimize the possible effect of reverse causality, participants with a history of stroke were excluded. In addition, we excluded participants without fasting triglyceride and fasting blood glucose at baseline.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Kailuan General Hospital and Beijing Tiantan Hospital. All of the participants provided written informed consent.

Data collection and definitions

Baseline data on demographics and clinical characteristics, including age, sex, body mass index, alcohol use, smoking status, income, education, blood pressure, physical activity, history of disease, and medications were collected via questionnaires by trained interviewers. Educational level was categorized as illiteracy or primary school, middle school, and high school or above. The high-income level was defined as participants’ average monthly income > 800 Renminbi/month. Smoking and drinking status was classified as three levels: never, former and current. Active physical activity was defined as “> 4 times per week and > 20 min at a time’’. Body mass index was calculated as weight (kg)/height (m)2. Systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure was the average of three measurements in the seated position using a mercury sphygmomanometer.

Venous blood samples were obtained from overnight fasting participants. Serum specimens were stored in the central laboratory of the Kailuan General Hospital. All the serum specimens were measured on the Hitachi 747 auto-analyzer (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan). Fasting blood glucose was measured by the hexokinase/glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase method. Serum triglyceride, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) were measured by the enzymatic colorimetric method. Plasma high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) were measured by using high-sensitivity particle-enhanced immunonephelometry assay.

Assessment of TyG index

TyG index was calculated as ln (fasting triglyceride [mg/dL] × fasting glucose [mg/dL]/2) [11]. Fasting triglyceride and fasting glucose concentration were biennially measured from 2006 to 2017. Baseline TyG index was calculated by using fasting triglyceride and fasting glucose measured during 2006–2007. To represent long-term TyG index patterns of participants, we calculated updated cumulative average TyG index using all available TyG index measurements from 2006 to the outcome events of interest or the end of follow-up [12].

Outcomes and follow-up

The outcome was the first occurrence of stroke, including ischemic stroke, intracerebral hemorrhage and subarachnoid hemorrhage according to the World Health Organization criteria [13]. Adjudication of incident stroke in the Kailuan Study was described previously [9]. In brief, participants were followed up at biennial routine medical examinations until December 31, 2017. Participants were interviewed face-to-face by trained research coordinators. The outcome was additionally confirmed by checking discharge summaries from the 11 hospitals and medical records from medical insurance. For the participants without face-to-face follow-ups, outcome information was obtained directly by checking death certificates from provincial vital statistics offices, discharge summaries and medical records.

Statistical analysis

TyG index was categorized into four groups by quartiles. Categorical variables were presented as proportions and continuous variables were presented as medians with interquartile ranges (IQRs). Difference between quartiles of TyG index were compared using χ2 test for categorical variables and Wilcoxon or Kruskal–Wallis test for continuous variables.

The associations of baseline and updated cumulative average TyG index with outcomes were explored with Cox proportional hazards models. In the first model, we adjusted for age and sex. The second model was adjusted for model 1 plus level of education, income, smoking status, alcohol abuse, physical activity, and body mass index. The third model was adjusted for model 2 plus systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, history of myocardial infarction, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and dyslipidemia, HDL-C, LDL-C, hs-CRP, antidiabetic drugs, lipid-lowering drugs and antihypertensive drugs. The hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were reported. Trend tests were performed in the regression models after the median TyG index values of each quartile were entered into the model and treated as a continuous variable.

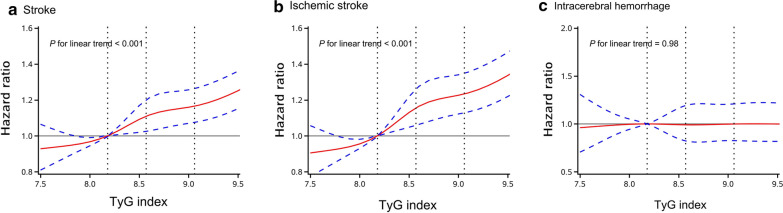

Time to the event in each group of TyG index at baseline illustrated using Kaplan–Meier curve. Additionally, restricted cubic splines were performed to examine the shape of the associations between baseline TyG index and outcomes with five knots (at the 5th, 25th, 50th, 50th, 75th and 95th percentiles). The reference point for baseline TyG index was the median of the reference group, and the HR was adjusted for all confounding variables. The potential linear relationships of baseline TyG index with outcomes were explored.

Stratified analyses about associations between baseline TyG index and outcomes were conducted between participants with a history of diabetes mellitus and without a history of diabetes mellitus.

A 2-sided value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed with SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

Results

A total of 101,510 participants completed the baseline survey in the Kailuan Study. After excluding 2571 participants with a history of stroke, and 1286 participants without fasting triglyceride and fasting blood glucose at baseline, a total of 97,653 participants were eligible for inclusion in this study (Additional file 1: Fig. S1). Baseline characteristics for participants excluded and included are shown in Additional file 2: Table S1. The median (IQR) age of participants included in this analysis was 51.67 (43.53–58.97) years. The median (IQR) of baseline TyG index was 8.58 (8.18–9.05). Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of patients according to baseline TyG index quartiles. Participants with higher quartiles of TyG index were more likely to be older, male, have a higher BMI and blood pressure, have a lower education level and income, have a higher proportion of current smokers and current drinkers, have a higher proportion of history of myocardial infarction, diabetes mellitus, hypertension and hypercholesterolemia, have a higher level of fasting plasma glucose, triglycerides, LDL-C, hs-CRP, have a lower level of HDL-C, and have a higher proportion of antidiabetic drugs, lipid-lowering drugs and antihypertensive drugs. Table 2 shows the baseline characteristics of patients according to the quartiles of updated cumulative average TyG index.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics according to quartiles of baseline TyG index

| Variable | Total | TyG index | P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quartile 1 (3.61–8.18) | Quartile 2 (8.18–8.57) | Quartile 3 (8.57–9.05) | Quartile 4 (9.05–12.50) | |||

| Participants, n | 97,653 | 24,412 | 24,414 | 24,415 | 24,412 | |

| Age, years | 51.67 (43.53–58.97) | 50.62 (41.69–58.57) | 51.68 (43.52–58.97) | 52.19 (44.13–59.44) | 52.05 (44.33–58.74) | < 0.001 |

| Male, n (%) | 77,748 (79.62) | 18,013 (73.79) | 19,350 (79.26) | 19,839 (81.26) | 20,546 (84.16) | < 0.001 |

| High school or above, n (%) | 19,064 (20.21) | 5751 (24.50) | 4556 (19.23) | 4526 (19.21) | 4231 (17.94) | < 0.001 |

| Income > 800 Renminbi/month, n (%) | 13,466 (14.29) | 3641 (15.52) | 3172 (13.40) | 3315 (14.07) | 3338 (14.16) | < 0.001 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 24.84 (22.60–27.22) | 23.14 (21.11–25.32) | 24.44 (22.39–26.64) | 25.43 (23.41–27.66) | 26.30 (24.22–28.41) | < 0.001 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 130.00 (119.30–140.70) | 120.00 (110.00–135.00) | 129.30 (116.70–140.00) | 130.00 (120.00–143.30) | 131.30 (120.00–150.00) | < 0.001 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 80.00 (78.70–90.00) | 80.00 (70.70–85.00) | 80.00 (77.30–90.00) | 80.70 (79.30–90.00) | 85.00 (80.00–92.00) | < 0.001 |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 32,577 (34.26) | 7876 (33.34) | 7615 (31.94) | 8160 (34.29) | 8926 (37.47) | < 0.001 |

| Current alcohol use, n (%) | 35,613 (37.44) | 8839 (37.40) | 8309 (34.84) | 8867 (37.25) | 9598 (40.28) | < 0.001 |

| Active physical activity, n (%) | 85,899 (91.27) | 21,392 (91.35) | 21,682 (91.75) | 21,366 (90.82) | 21,459 (91.16) | 0.004 |

| Myocardial infarction, n (%) | 1105 (1.13) | 196 (0.80) | 245 (1.00) | 312 (1.28) | 352 (1.44) | < 0.001 |

| Diabetes Mellitus, n (%) | 2860 (2.93) | 175 (0.72) | 311 (1.27) | 625 (2.56) | 1749 (7.17) | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 11,450 (11.73) | 1720 (7.05) | 2379 (9.74) | 3255 (13.33) | 4096 (16.78) | < 0.001 |

| Hypercholesterolemia, n (%) | 5429 (5.56) | 691 (2.83) | 996 (4.08) | 1519 (6.22) | 2223 (9.11) | < 0.001 |

| Fasting plasma glucose, mmol/L | 5.11 (4.66–5.71) | 4.78 (4.38–5.20) | 5.01 (4.62–5.46) | 5.24 (4.80–5.81) | 5.66 (5.02–6.90) | < 0.001 |

| Triglycerides, mmol/L | 1.27 (0.89–1.93) | 0.70 (0.58–0.82) | 1.10 (0.98–1.22) | 1.56 (1.36–1.79) | 2.77 (2.18–3.90) | < 0.001 |

| HDL-C, mmol/L | 1.51 (1.28–1.77) | 1.54 (1.30–1.80) | 1.53 (1.31–1.77) | 1.49 (1.27–1.74) | 1.47 (1.25–1.75) | < 0.001 |

| LDL-C, mmol/L | 2.33 (1.82–2.83) | 2.13 (1.60–2.72) | 2.38 (1.92–2.82) | 2.41 (1.97–2.90) | 2.38 (1.82–2.88) | < 0.001 |

| Hs-CRP, mg/L | 0.80 (0.30–2.19) | 0.60 (0.21–1.90) | 0.72 (0.29–2.00) | 0.88 (0.33–2.20) | 1.03 (0.40–2.63) | < 0.001 |

| TyG index | 8.58 (8.18–9.05) | 7.91 (7.70–8.06) | 8.39 (8.29–8.48) | 8.79 (8.68–8.91) | 9.46 (9.23–9.82) | < 0.001 |

| Antidiabetic drugs, n (%) | 2185 (2.24) | 131 (0.54) | 224 (0.92) | 478 (1.96) | 1352 (5.54) | < 0.001 |

| Lipid-lowering drugs, n (%) | 796 (0.82) | 93 (0.38) | 158 (0.65) | 187 (0.77) | 358 (1.47) | < 0.001 |

| Antihypertensive drugs, n (%) | 9895 (10.13) | 1484 (6.08) | 2036 (8.34) | 2840 (11.63) | 3535 (14.48) | < 0.001 |

Data are given as median (interquartile range) unless otherwise indicated

HDL-C high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, LDL-C low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, Hs-CRP high-sensitive C-reactive protein, TyG index triglyceride-glucose

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics according to quartiles of updated cumulative average TyG index

| Variable | Total | TyG index | P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quartile 1 (4.67–8.31) | Quartile 2 (8.31–8.65) | Quartile 3 (8.65–9.06) | Quartile 4 (9.06–12.20) | |||

| Participants, n | 97,653 | 24,413 | 24,413 | 24,414 | 24,413 | |

| Age, years | 51.67 (43.53–58.97) | 51.61 (42.65–60.31) | 51.79 (43.61–59.21) | 52.03 (44.05–58.95) | 51.27 (43.63–57.64) | < 0.001 |

| Male, n (%) | 77,748 (79.62) | 18,539 (75.94) | 19,345 (79.24) | 19,642 (80.45) | 20,222 (82.83) | < 0.001 |

| High school or above, n (%) | 19,064 (20.21) | 5375 (22.75) | 4559 (19.29) | 4626 (19.66) | 4504 (19.15) | < 0.001 |

| Income > 800 Renminbi/month, n (%) | 13,466 (14.29) | 3481 (14.74) | 3214 (13.61) | 3374 (14.35) | 3397 (14.44) | 0.004 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 24.84 (22.60–27.22) | 23.04 (21.05–25.26) | 24.39 (22.41–26.61) | 25.45 (23.43–27.64) | 26.37 (24.34–28.51) | < 0.001 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 130.00 (119.30–140.70) | 120.70 (110.00–138.70) | 129.00 (116.70–140.00) | 130.00 (120.00–144.00) | 130.00 (120.00–150.00) | < 0.001 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 80.00 (78.70–90.00) | 80.00 (70.70–86.00) | 80.00 (76.70–90.00) | 80.70 (79.30–90.00) | 83.30 (80.00–91.30) | < 0.001 |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 32,577 (34.26) | 7628 (32.10) | 7667 (32.23) | 8240 (34.72) | 9042 (37.99) | < 0.001 |

| Current alcohol use, n (%) | 35,613 (37.44) | 8539 (35.91) | 8288 (34.83) | 9038 (38.08) | 9748 (40.95) | < 0.001 |

| Active physical activity, n (%) | 85,899 (91.27) | 21,705 (92.04) | 21,528 (91.32) | 21,325 (90.85) | 21,341 (90.87) | < 0.001 |

| Myocardial infarction, n (%) | 1105 (1.13) | 214 (0.88) | 276 (1.13) | 289 (1.18) | 326 (1.34) | < 0.001 |

| Diabetes Mellitus, n (%) | 2860 (2.93) | 139 (0.57) | 329 (1.35) | 614 (2.52) | 1778 (7.28) | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 11,450 (11.73) | 1700 (6.96) | 2419 (9.91) | 3224 (13.21) | 4107 (16.82) | < 0.001 |

| Hypercholesterolemia, n (%) | 5429 (5.56) | 631 (2.59) | 1041 (4.26) | 1440 (5.90) | 2317 (9.49) | < 0.001 |

| Fasting plasma glucose, mmol/L | 5.11 (4.66–5.71) | 4.84 (4.45–5.26) | 5.03 (4.61–5.50) | 5.20 (4.73–5.80) | 5.60 (5.00–6.70) | < 0.001 |

| Triglycerides, mmol/L | 1.27 (0.89–1.93) | 0.76 (0.60–0.96) | 1.13 (0.92–1.38) | 1.51 (1.19–1.93) | 2.43 (1.75–3.56) | < 0.001 |

| HDL-C, mmol/L | 1.51 (1.28–1.77) | 1.55 (1.31–1.81) | 1.53 (1.30–1.78) | 1.49 (1.27–1.74) | 1.45 (1.24–1.72) | < 0.001 |

| LDL-C, mmol/L | 2.33 (1.82–2.83) | 2.15 (1.63–2.71) | 2.36 (1.90–2.81) | 2.40 (1.96–2.90) | 2.39 (1.85–2.90) | < 0.001 |

| Hs-CRP, mg/L | 0.80 (0.30–2.19) | 0.59 (0.20–1.70) | 0.72 (0.29–2.00) | 0.89 (0.33–2.25) | 1.10 (0.45–2.72) | < 0.001 |

| TyG index | 8.58 (8.18–9.05) | 8.00 (7.74–8.23) | 8.43 (8.22–8.62) | 8.77 (8.53–9.01) | 9.35 (9.03–9.76) | < 0.001 |

| Antidiabetic drugs, n (%) | 2185 (2.24) | 97 (0.40) | 229 (0.94) | 488 (2.00) | 1371 (5.62) | < 0.001 |

| Lipid-lowering drugs, n (%) | 796 (0.82) | 81 (0.33) | 148 (0.61) | 204 (0.84) | 363 (1.49) | < 0.001 |

| Antihypertensive drugs, n (%) | 9895 (10.13) | 1446 (5.92) | 2094 (8.58) | 2809 (11.51) | 3546 (14.53) | < 0.001 |

Data are given as median (interquartile range) unless otherwise indicated

HDL-C high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, LDL-C low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, Hs-CRP high-sensitive C-reactive protein, TyG triglyceride-glucose

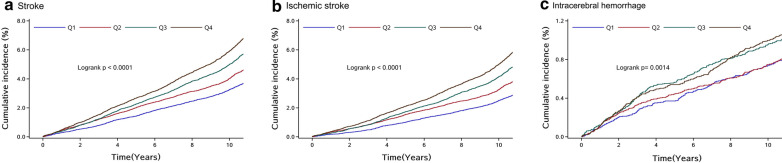

After a median follow-up of 11.02 years (IQR 10.68–11.20 years), 5122 (5.25%) participants developed stroke, of whom 4277 were ischemic stroke, 880 intracerebral hemorrhage, and 144 subarachnoid hemorrhage. The incidence of stroke, ischemic stroke, intracerebral hemorrhage and subarachnoid hemorrhage was 5.05, 4.20, 0.85 and 0.14 per 1000 person-years, respectively. Participants with higher levels of baseline TyG index had a higher risk of stroke, ischemic stroke, and intracerebral hemorrhage (Fig. 1) (P < 0.05). After adjustment for potential confounding factors in the model 3, compared with participants with the lowest quartile of baseline TyG index, the adjusted HRs (95% CI) for stroke in the second, third, and highest quartiles of baseline TyG index were 1.08 (0.99–1.18), 1.22 (1.12–1.33), and 1.32 (1.21–1.44), respectively. The adjusted HRs (95% CI) for ischemic stroke in the second, third, and highest quartiles of baseline TyG index were 1.14 (1.03–1.26), 1.31 (1.19–1.44), and 1.45 (1.31–1.59), respectively. However, there were no significant associations between baseline TyG index and intracerebral hemorrhage, after adjustment for potential confounding factors in the model 3 (Table 3). Multivariable-adjusted spline regression models showed linear associations between baseline TyG index levels and the risk of stroke and ischemic stroke (Fig. 2). Similar results were observed for the association of updated cumulative average TyG index with outcomes (Table 4).

Fig. 1.

Kaplan–Meier curves of incidence of outcomes according to quartiles of baseline TyG index. a Stroke; b Ischemic stroke; c Intracerebral hemorrhage. Q1: quartile 1; Q2: quartile 2; Q3: quartile 3; Q4: quartile 4

Table 3.

HRs for risk of outcomes according to quartiles of baseline TyG index

| Outcomes | TyG index | P value for trend | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quartile 1 (3.61–8.18) | Quartile 2 (8.18–8.57) | Quartile 3 (8.57–9.05) | Quartile 4 (9.05–12.50) | ||

| Stroke | |||||

| Case, n (%) | 922 (3.78) | 1139 (4.67) | 1403 (5.75) | 1658 (6.79) | |

| Incidence, per 1000 person-y | 3.60 | 4.48 | 5.54 | 6.59 | |

| Model 1 | Reference | 1.20 (1.10–1.31) | 1.46 (1.35–1.59) | 1.79 (1.65–1.93) | < 0.001 |

| Model 2 | Reference | 1.14 (1.05–1.25) | 1.34 (1.23–1.46) | 1.58 (1.45–1.72) | < 0.001 |

| Model 3 | Reference | 1.08 (0.99–1.18) | 1.22 (1.12–1.33) | 1.32 (1.21–1.44) | < 0.001 |

| Ischemic stroke | |||||

| Case, n (%) | 725 (2.97) | 944 (3.87) | 1183 (4.85) | 1425 (5.84) | |

| Incidence, per 1000 person-y | 2.82 | 3.70 | 4.65 | 5.64 | |

| Model 1 | Reference | 1.26 (1.15–1.39) | 1.57 (1.43–1.72) | 1.96 (1.79–2.14) | < 0.001 |

| Model 2 | Reference | 1.21 (1.10–1.33) | 1.44 (1.31–1.58) | 1.73 (1.58–1.90) | < 0.001 |

| Model 3 | Reference | 1.14 (1.03–1.26) | 1.31 (1.19–1.44) | 1.45 (1.31–1.59) | < 0.001 |

| Intracerebral hemorrhage | |||||

| Case, n (%) | 190 (0.78) | 193 (0.79) | 244 (1.00) | 253 (1.04) | |

| Incidence, per 1000 person-y | 0.73 | 0.75 | 0.95 | 0.98 | |

| Model 1 | Reference | 0.98 (0.80–1.20) | 1.22 (1.01–1.48) | 1.30 (1.07–1.56) | < 0.001 |

| Model 2 | Reference | 0.93 (0.76–1.14) | 1.13 (0.93–1.37) | 1.16 (0.95–1.41) | 0.04 |

| Model 3 | Reference | 0.89 (0.73–1.09) | 1.03 (0.85–1.25) | 0.97 (0.79–1.18) | 0.84 |

Model 1, adjusted for age and sex

Model 2, adjusted for variables in model 1 plus level of education, income, smoking, alcohol abuse, physical activity, and body mass index

Model 3, adjusted for variables in model 2 plus systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, history of myocardial infarction, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and dyslipidemia, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high-sensitive C-reactive protein, antidiabetic drugs, lipid-lowering drugs and antihypertensive drugs

TyG indicates triglyceride-glucose

Fig. 2.

Adjusted hazard ratios of outcomes according to baseline TyG index. a Stroke; b Ischemic stroke; c Intracerebral hemorrhage. Data were fitted using a Cox regression model of restricted cubic spline with five knots (at the 5th, 25th, 50th, 50th, 75th and 95th percentiles) adjusting for potential covariates. The reference point for TyG index was the median of the reference group. Red lines indicate adjusted hazard ratio, and blue lines indicate the 95% confidence interval bands

Table 4.

HRs for risk of outcomes according to quartiles of updated cumulative average TyG index

| Outcomes | TyG index | P value for trend | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quartile 1 (4.67–8.31) | Quartile 2 (8.31–8.65) | Quartile 3 (8.65–9.06) | Quartile 4 (9.06–12.20) | ||

| Stroke | |||||

| Case, n (%) | 1056 (4.33) | 1157 (4.74) | 1291 (5.29) | 1618 (6.63) | |

| Incidence, per 1000 person-y | 4.18 | 4.54 | 5.06 | 6.42 | |

| Model 1 | Reference | 1.12 (1.03–1.22) | 1.27 (1.17–1.37) | 1.71 (1.58–1.85) | < 0.001 |

| Model 2 | Reference | 1.06 (0.98–1.16) | 1.16 (1.06–1.26) | 1.50 (1.38–1.63) | < 0.001 |

| Model 3 | Reference | 1.01 (0.93–1.10) | 1.05 (0.96–1.14) | 1.25 (1.15–1.36) | < 0.001 |

| Ischemic stroke | |||||

| Case, n (%) | 830 (3.40) | 963 (3.94) | 1089 (4.46) | 1395 (5.71) | |

| Incidence, per 1000 person-y | 3.27 | 3.76 | 4.25 | 5.51 | |

| Model 1 | Reference | 1.19 (1.08–1.31) | 1.37 (1.25–1.50) | 1.89 (1.73–2.06) | < 0.001 |

| Model 2 | Reference | 1.13 (1.03–1.24) | 1.25 (1.14–1.37) | 1.66 (1.51–1.81) | < 0.001 |

| Model 3 | Reference | 1.07 (0.98–1.18) | 1.13 (1.03–1.24) | 1.39 (1.27–1.52) | < 0.001 |

| Intracerebral hemorrhage | |||||

| Case, n (%) | 219 (0.90) | 203 (0.83) | 214 (0.88) | 244 (1.00) | |

| Incidence, per 1000 person-y | 0.85 | 0.78 | 0.83 | 0.95 | |

| Model 1 | Reference | 0.94 (0.78–1.14) | 1.00 (0.83–1.21) | 1.20 (1.00–1.44) | 0.04 |

| Model 2 | Reference | 0.89 (0.73–1.08) | 0.92 (0.76–1.11) | 1.06 (0.88–1.29) | 0.45 |

| Model 3 | Reference | 0.85 (0.70–1.03) | 0.83 (0.68–1.00) | 0.89 (0.73–1.08) | 0.26 |

Model 1, adjusted for age and sex

Model 2, adjusted for variables in model 1 plus level of education, income, smoking, alcohol abuse, physical activity, and body mass index

Model 3, adjusted for variables in model 2 plus systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, a history of myocardial infarction, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and dyslipidemia, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high-sensitive C-reactive protein, antidiabetic drugs, lipid-lowering drugs and antihypertensive drugs. TyG indicates triglyceride-glucose

In our secondary analysis, Cox regression models were recalculated in participants with and without a history of diabetes mellitus (Additional file 2: Table S2). Higher quartiles of baseline TyG index were associated with an increased risk of stroke and ischemic stroke in participants without a history of diabetes mellitus. Baseline TyG index were not associated with outcomes in participants with a history of diabetes mellitus. There was no interaction between baseline TyG index and with or without a history of diabetes mellitus for the risk of outcomes (P for interaction > 0.05).

Discussion

In this large, prospective, population-based cohort study, we found that higher levels of TyG index at baseline were associated with an increased risk of future stroke and ischemic stroke during an 11-year follow-up. However, there was no significant association between baseline TyG index and intracerebral hemorrhage. Similar results were observed for the associations of long-term updated cumulative average TyG index with outcomes.

Former studies indicated that TyG index was associated with cardiovascular disease. A retrospective cohort study showed that elevated levels of TyG index were associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease in participants aged over 60 years [6]. Higher levels of TyG index were significantly associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular events and coronary heart disease during long-term follow‑up [5]. TyG index was also an independent predictor of coronary artery calcification progression [11], coronary artery disease severity and cardiovascular outcomes [14]. However, data about associations between TyG index and stroke and its subtypes are limited. A cohort study with 5014 apparently healthy participants indicated that higher levels of TyG index were not significantly associated with cerebrovascular disease, but it indicated that those with higher levels of TyG index tended to have higher risk of cerebrovascular disease [7]. In this current study, the incidence of stroke increased according to TyG index levels. We also found that the both baseline and long-term updated cumulative average TyG index were independently associated the risk of stroke and ischemic stroke. This lack of statistical significance in that previous cohort study may be explained by the smaller number of outcome events.

The mechanisms accounting for the associations between TyG index and stroke and ischemic stroke remain unclear. TyG index is a surrogate marker of insulin resistance, which may mainly account for these associations [1, 15–17]. Firstly, insulin resistance led to the chronic inflammation [18], endothelium dysfunction [19–21], facilitated the formation of foam cells in the initiation of atherosclerosis [22] and promoted the vulnerable plaque [23]. Previous studies indicated that TyG index was associated with increased arterial stiffness in general population [24, 25] and an independent predictive marker for plaque progress [26], which could contribute to the occurrence of stroke. Secondly, previous research showed that insulin resistance affected platelet adhesion, activation and aggregation [27–29] which were associated with artery stenosis or occlusion and involved in stroke occurrence. Higher TyG index levels were associated with an increased risk of coronary artery stenosis and the number and the severity of artery stenoses [30, 31]. Thirdly, participants with higher quartiles of TyG index were more likely to be older, male, have a higher BMI, have a higher proportion of current smokers and history of myocardial infarction, diabetes mellitus, hypertension and hypercholesterolemia, have a higher level of fasting plasma glucose, triglycerides, LDL-C and hs-CRP, which were a cluster of risk factors for stroke [32–37]. Insulin resistance could modify and influence the role of the stroke risk factors and contribute to stroke [17].

Participants with higher levels of baseline and updated cumulative average TyG index had a higher risk of intracerebral hemorrhage, after adjusted for age and sex. However, statistical relevance was not significant for intracerebral hemorrhage in the multivariate adjusted models. Previous studies showed that insulin resistance measured by HOMA-IR [38, 39] and euglycaemic insulin clamp [40] was not associated with intracerebral hemorrhage, which was consist with our results. Hypertension, intake of antithrombotic drugs and amyloid angiopathy were the most important risk factors for intracerebral hemorrhage [41], which may explain for this nonsignificant association.

There are some limitations in this study. First, fasting insulin was not measured in the Kailuan Study and HOMA-IR could not be evaluated. Therefore, we could not compare the predictive value of TyG index and HOMA-IR for occurrence of stroke. Second, participants at higher levels of TyG index with a cluster of vascular risk factors were more likely to take low fat diet, take more exercise, control blood pressure and weight, quit smoking and restrict the intake of alcohol, according to the medical advice. Third, the study was not nationally representative. All participants were recruited from northern China and most of them were men.

Conclusions

Elevated levels of both baseline and long-term updated cumulative average TyG index were independent predictors for stroke and ischemic stroke instead of intracerebral hemorrhage in the general population during an 11-year follow-up.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Fig. S1. Flow chart of the present study.

Additional file 2: Table S1. Baseline characteristics for participants excluded and included. Table S2. HR for risk of outcomes according to quartiles of baseline TyG index stratified by history of diabetes mellitus status.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the patients for participating and all participating centers in this study.

Abbreviations

- TyG

Triglyceride-glucose

- HDL-C

High-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- LDL-C

Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- Hs-CRP

High-sensitivity C-reactive protein

- HR

Hazard ratio

- CI

Confidence interval

- IQR

Interquartile range

Authors’ contributions

AW and GW contributed to study concept and design, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript and served as the equally contributing first authors of the manuscript. QL, YZ, SC, BT, and XT contributed to acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data and revision of the drafting of the manuscript. PW and XM contributed to acquisition of data and revision of the drafting of the manuscript. SW, YJW and YLW contributed to study concept and design, study supervision or coordination, revision of the drafting of the manuscript and served as the corresponding authors of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (81825007); Beijing Outstanding Young Scientist Program (BJJWZYJH01201910025030); Ministry of Science and Technology of the People's Republic of China (2017YFC1307900, 2018YFC1312903 and 2018YFC1312402); Beijing Municipal Science and Technology Commission (D171100003017002 and Z181100001818001).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets during and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Kailuan General Hospital and Beijing Tiantan Hospital. All of the participants provided written informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Anxin Wang and Guangyao Wang are equally contributing first authors

Contributor Information

Shouling Wu, Email: drwusl@163.com.

Yongjun Wang, Email: yongjunwang@ncrcnd.org.cn.

Yilong Wang, Email: yilong528@gmail.com.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12933-021-01238-1.

References

- 1.Kernan WN, Inzucchi SE, Viscoli CM, Brass LM, Bravata DM, Horwitz RI. Insulin resistance and risk for stroke. Neurology. 2002;59:809–815. doi: 10.1212/WNL.59.6.809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kernan WN, Inzucchi SE, Viscoli CM, Brass LM, Bravata DM, Shulman GI, et al. Impaired insulin sensitivity among nondiabetic patients with a recent TIA or ischemic stroke. Neurology. 2003;60:1447–1451. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000063318.66140.A3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simental-Mendía LE, Rodríguez-Morán M, Guerrero-Romero F. The product of fasting glucose and triglycerides as surrogate for identifying insulin resistance in apparently healthy subjects. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2008;6:299–304. doi: 10.1089/met.2008.0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guerrero-Romero F, Villalobos-Molina R, Jiménez-Flores JR, Simental-Mendia LE, Méndez-Cruz R, Murguía-Romero M, et al. Fasting triglycerides and glucose index as a diagnostic test for insulin resistance in young adults. Arch Med Res. 2016;47:382–387. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2016.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barzegar N, Tohidi M, Hasheminia M, Azizi F, Hadaegh F. The impact of triglyceride-glucose index on incident cardiovascular events during 16 years of follow-up: Tehran lipid and glucose study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2020;19:155. doi: 10.1186/s12933-020-01121-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li S, Guo B, Chen H, Shi Z, Li Y, Tian Q, et al. The role of the triglyceride (triacylglycerol) glucose index in the development of cardiovascular events: a retrospective cohort analysis. Sci Rep. 2019;9:7320. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-43776-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sánchez-Íñigo L, Navarro-González D, Fernández-Montero A, Pastrana-Delgado J, Martínez JA. The TyG index may predict the development of cardiovascular events. Eur J Clin Invest. 2016;46:189–197. doi: 10.1111/eci.12583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shi W, Xing L, Jing L, Tian Y, Yan H, Sun Q, et al. Value of triglyceride-glucose index for the estimation of ischemic stroke risk: insights from a general population. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2020;30:245–253. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2019.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang A, Li H, Yuan J, Zuo Y, Zhang Y, Chen S, et al. Visit-to-visit variability of lipids measurements and the risk of stroke and stroke types: a prospective cohort study. J Stroke. 2020;22:119–129. doi: 10.5853/jos.2019.02075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang A, Liu X, Xu J, Han X, Su Z, Chen S, et al. Visit-to-visit variability of fasting plasma glucose and the risk of cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality in the general population. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6:e006757. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.006757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park K, Ahn CW, Lee SB, Kang S, Nam JS, Lee BK, et al. Elevated TyG index predicts progression of coronary artery calcification. Diabetes Care. 2019;42:1569–1573. doi: 10.2337/dc18-1920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jin C, Li G, Rexrode KM, Gurol ME, Yuan X, Hui Y, et al. Prospective study of fasting blood glucose and intracerebral hemorrhagic risk. Stroke. 2018;49:27–33. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.019189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.WHO Stroke Recommendations on stroke prevention, diagnosis, and therapy. Report of the who task force on stroke and other cerebrovascular disorders. Stroke. 1989;20:1407–1431. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.20.10.1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mao Q, Zhou D, Li Y, Wang Y, Xu SC, Zhao XH. The triglyceride-glucose index predicts coronary artery disease severity and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with non-st-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome. Dis Markers. 2019;2019:6891537. doi: 10.1155/2019/6891537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee SB, Kim MK, Kang S, Park K, Kim JH, Baik SJ, et al. Triglyceride glucose index is superior to the homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance for predicting nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in korean adults. Endocrinol Metab. 2019;34:179–186. doi: 10.3803/EnM.2019.34.2.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Irace C, Carallo C, Scavelli FB, De Franceschi MS, Esposito T, Tripolino C, et al. Markers of insulin resistance and carotid atherosclerosis. A comparison of the homeostasis model assessment and triglyceride glucose index. Int J Clin Pract. 2013;67:665–672. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.12124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deng XL, Liu Z, Wang C, Li Y, Cai Z. Insulin resistance in ischemic stroke. Metab Brain Dis. 2017;32:1323–1334. doi: 10.1007/s11011-017-0050-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bloomgarden ZT. Inflammation and insulin resistance. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:1619–1623. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.5.1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lteif AA, Han K, Mather KJ. Obesity, insulin resistance, and the metabolic syndrome: determinants of endothelial dysfunction in whites and blacks. Circulation. 2005;112:32–38. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.520130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tallapragada DS, Karpe PA, Tikoo K. Long-lasting partnership between insulin resistance and endothelial dysfunction: role of metabolic memory. Br J Pharmacol. 2015;172:4012–4023. doi: 10.1111/bph.13145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Janus A, Szahidewicz-Krupska E, Mazur G, Doroszko A. Insulin resistance and endothelial dysfunction constitute a common therapeutic target in cardiometabolic disorders. Mediat Inflamm. 2016;2016:3634948. doi: 10.1155/2016/3634948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oh J, Riek AE, Darwech I, Funai K, Shao J, Chin K, et al. Deletion of macrophage vitamin D receptor promotes insulin resistance and monocyte cholesterol transport to accelerate atherosclerosis in mice. Cell Rep. 2015;10:1872–1886. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.02.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iguchi T, Hasegawa T, Otsuka K, Matsumoto K, Yamazaki T, Nishimura S, et al. Insulin resistance is associated with coronary plaque vulnerability: insight from optical coherence tomography analysis. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014;15:284–291. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jet158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee SB, Ahn CW, Lee BK, Kang S, Nam JS, You JH, et al. Association between triglyceride glucose index and arterial stiffness in korean adults. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2018;17:41. doi: 10.1186/s12933-018-0692-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Poon AK, Meyer ML, Tanaka H, Selvin E, Pankow J, Zeng D, et al. Association of insulin resistance, from mid-life to late-life, with aortic stiffness in late-life: the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2020;19:11. doi: 10.1186/s12933-020-0986-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Won KB, Lee BK, Park HB, Heo R, Lee SE, Rizvi A, et al. Quantitative assessment of coronary plaque volume change related to triglyceride glucose index: the progression of atherosclerotic plaque determined by computed tomographic angiography imaging (paradigm) registry. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2020;19:113. doi: 10.1186/s12933-020-01081-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moore SF, Williams CM, Brown E, Blair TA, Harper MT, Coward RJ, et al. Loss of the insulin receptor in murine megakaryocytes/platelets causes thrombocytosis and alterations in IGF signalling. Cardiovasc Res. 2015;107:9–19. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvv132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Santilli F, Vazzana N, Liani R, Guagnano MT, Davì G. Platelet activation in obesity and metabolic syndrome. Obes Rev. 2012;13:27–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2011.00930.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Randriamboavonjy V, Fleming I. Insulin, insulin resistance, and platelet signaling in diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:528–530. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee EY, Yang HK, Lee J, Kang B, Yang Y, Lee SH, et al. Triglyceride glucose index, a marker of insulin resistance, is associated with coronary artery stenosis in asymptomatic subjects with type 2 diabetes. Lipids Health Dis. 2016;15:155. doi: 10.1186/s12944-016-0324-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thai PV, Tien HA, Van Minh H, Valensi P. Triglyceride glucose index for the detection of asymptomatic coronary artery stenosis in patients with type 2 diabetes. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2020;19:137. doi: 10.1186/s12933-020-01108-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jia Q, Liu L, Wang Y. Risk factors and prevention of stroke in the chinese population. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2011;20:395–400. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2010.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Holmes MV, Millwood IY, Kartsonaki C, Hill MR, Bennett DA, Boxall R, et al. Lipids, lipoproteins, and metabolites and risk of myocardial infarction and stroke. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71:620–632. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhou Y, Han W, Gong D, Man C, Fan Y. Hs-Crp in stroke: a meta-analysis. Clin Chim Acta. 2016;453:21–27. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2015.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boden-Albala B, Cammack S, Chong J, Wang C, Wright C, Rundek T, et al. Diabetes, fasting glucose levels, and risk of ischemic stroke and vascular events: findings from the northern manhattan study (nomas) Diabetes Care. 2008;31:1132–1137. doi: 10.2337/dc07-0797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kurth T, Everett BM, Buring JE, Kase CS, Ridker PM, Gaziano JM. Lipid levels and the risk of ischemic stroke in women. Neurology. 2007;68:556–562. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000254472.41810.0d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang YJ, Li ZX, Gu HQ, Zhai Y, Jiang Y, Zhao XQ, et al. China stroke statistics 2019: a report from the National Center for Healthcare Quality Management in neurological diseases, China National Clinical Research Center for neurological diseases, the Chinese Stroke Association, National Center for chronic and non-communicable disease control and prevention, Chinese Center for disease control and prevention and Institute for Global Neuroscience and Stroke Collaborations. Stroke Vasc Neurol. 2020;5:211–239. doi: 10.1136/svn-2020-000457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wieberdink RG, Koudstaal PJ, Hofman A, Witteman JC, Breteler MM, Ikram MA. Insulin resistance and the risk of stroke and stroke subtypes in the nondiabetic elderly. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;176:699–707. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Howard G, Wagenknecht LE, Kernan WN, Cushman M, Thacker EL, Judd SE, et al. Racial differences in the association of insulin resistance with stroke risk: the reasons for geographic and racial differences in stroke (regards) study. Stroke. 2014;45:2257–2262. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.005306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wiberg B, Sundstrom J, Zethelius B, Lind L. Insulin sensitivity measured by the euglycaemic insulin clamp and proinsulin levels as predictors of stroke in elderly men. Diabetologia. 2009;52:90–96. doi: 10.1007/s00125-008-1171-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Diener HC, Hankey GJ. Primary and secondary prevention of ischemic stroke and cerebral hemorrhage: Jacc focus seminar. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:1804–1818. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.12.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Fig. S1. Flow chart of the present study.

Additional file 2: Table S1. Baseline characteristics for participants excluded and included. Table S2. HR for risk of outcomes according to quartiles of baseline TyG index stratified by history of diabetes mellitus status.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets during and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.