Abstract

Background

Aggressive behaviour is prevalent in people with intellectual disabilities. To understand the aetiology, it is important to recognize factors associated with the behaviour.

Method

A systematic review was conducted and included studies published between January 2002 and April 2017 on the association of behavioural, psychiatric and psychosocial factors with aggressive behaviour in adults with intellectual disabilities.

Results

Thirty‐eight studies were included that presented associations with 11 behavioural, psychiatric and psychosocial factors. Conflicting evidence was found on the association of these factors with aggressive behaviour.

Conclusions

The aetiology of aggressive behaviour is specific for a certain person in a certain context and may be multifactorial. Additional research is required to identify contributing factors, to understand causal relationships and to increase knowledge on possible interaction effects of different factors.

Keywords: aggression, intellectual disability, psychiatric disorders, psychiatric symptoms, psychosocial factors, self‐injurious behaviour

1. BACKGROUND

Aggressive behaviour is common in people with intellectual disabilities (Cooper et al., 2009; Embregts et al., 2009). It is the main reason for referral to mental health services and placement in institutions (Crocker et al., 2006; Tenneij et al., 2009; Tsiouris et al., 2011). Aggressive behaviour can have serious negative consequences for people with intellectual disability, since it can impair their personal development and social relationships, which likely decreases their quality of life (Crocker et al., 2014; Embregts et al., 2009; Lundqvist, 2013). Furthermore, it often places a heavy burden on relatives and caregivers, which in turn can negatively impact the care for people with intellectual disability (Hartley & MacLean, 2007; Lundqvist, 2013).

Aggressive behaviour can manifest as different topographies, including physically aggressive behaviour, verbally aggressive behaviour, destructive behaviour, sexually aggressive behaviour and self‐injurious behaviour (Crocker et al., 2006; Sorgi et al., 1991). It is important to note that aggressive behaviour is not a disorder. It should be seen as behaviour that often serves a function for the person displaying this behaviour, although it is often not immediately clear what the cause or function of the behaviour is. To select the most effective treatment, it is imperative to understand the aetiology of the aggressive behaviour for a specific individual. This can be achieved by performing a functional assessment (Ali et al., 2014; Antonacci et al., 2008; Embregts et al., 2009; Kerr et al., 2013; Lloyd & Kennedy, 2014). A functional assessment may be descriptive or experimental in nature, but the focus of the assessment is on understanding the behaviour and all factors that may contribute to the emergence or continuation of that behaviour (Ali et al., 2014; Hanley et al., 2003; LaVigna & Willis, 2012; Lloyd & Kennedy, 2014). The results of this assessment may guide the treatment process and inform future preventive measures.

A range of factors has been suggested as contributing to the emergence or continuation of aggressive behaviour, including biological, psychological, social, developmental and environmental factors (Ali et al., 2014; Embregts et al., 2009). A better understanding of the factors that are commonly associated with aggressive behaviour in people with intellectual disability may support the functional assessment process. This review focuses on three groups of factors that have been suggested to be associated with aggressive behaviour: behavioural factors, psychiatric factors and psychosocial factors (Cooper et al., 2009; Emerson et al., 2001). These factors are all possible targets of interventions that may help to reduce or eliminate the aggressive behaviour. This review therefore aims to provide an overview of the association of behavioural, psychiatric and psychosocial factors with aggressive behaviour in adults with intellectual disability.

2. METHOD

2.1. Search strategy

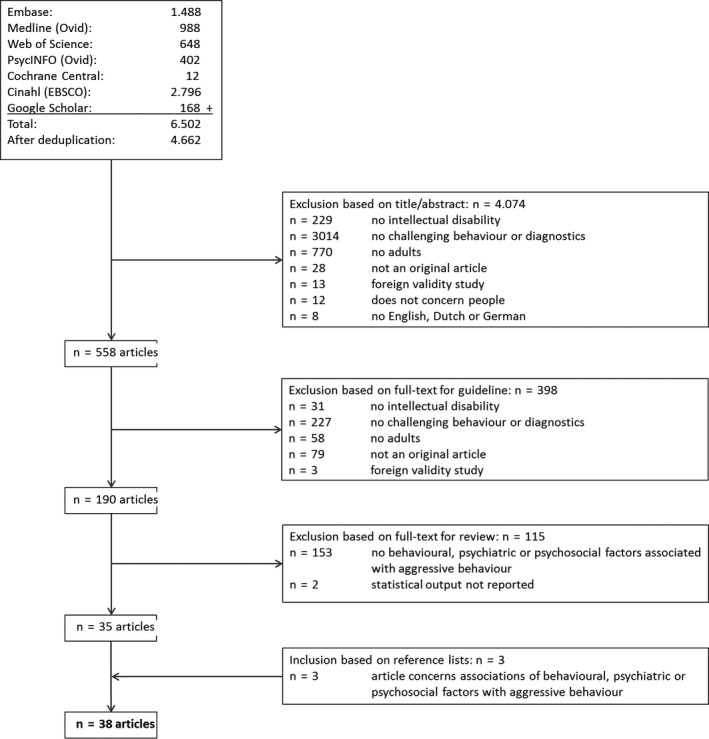

This review was part of a larger research project to develop Dutch multidisciplinary guidelines concerning challenging behaviour in adults with intellectual disability. Seven databases (Embase, Medline, Web of Science, PsycINFO, Cochrane Central, CINAHL and Google Scholar [first 200 hits]) were searched for articles published between 2002 and April 2017. A wide variety of the following search terms was used: intellectual disability, challenging behaviour and different terms for behavioural, psychiatric and psychosocial factors (the detailed search strategies were developed in collaboration with a medical information specialist and can be found in Appendix 1). Search results were entered into Endnote X9 software (Clarivate Analytics) and duplicates were removed.

2.2. Study selection

Publications were included when the following criteria were met:

The publication concerns people with mild to profound intellectual disability;

-

The publication concerns either:

Methods for describing challenging behaviour or the person with intellectual disability that are not assessed by the Dutch commission of quality assessment of testing methods (COTAN); or

Non‐somatic factors related to the presence of challenging behaviour;

The publication concerns adults (≥18 years) or results are presented separately for adults;

The publication is written in Dutch, English or German.

Publications were excluded when the following criteria were met:

The study sample consists entirely of people with a specific syndrome;

The publication exclusively concerns an association between age, sex or degree of intellectual disability and challenging behaviour;

The publication exclusively concerns biological factors related to the presence of challenging behaviour;

The publication is a validity study aimed at validation within a non‐Dutch context;

The publication is an abstract, editorial, book, dissertation, commentary or non‐systematic review.

Title and abstract of the first 100 references were screened independently by two reviewers. A sufficient level of agreement was reached (91% agreement; Cohen's κ = .52). Disagreements were discussed and the remaining publications were screened by a single reviewer. When in doubt, a second reviewer screened the article and disagreements were discussed until consensus was reached. All potentially relevant articles were obtained as full text and the first 20 articles were screened by two reviewers. A sufficient level of agreement was reached (90% agreement; Cohen's κ = .76), and the remaining articles were screened by one reviewer.

2.2.1. Additional step

Only those publications included as part of the guideline development process that concerned factors related to aggressive behaviours were included in the current review. Subsequently, the reference lists of these articles were screened, with the purpose of identifying additional publications meeting the inclusion criteria for this systematic review.

2.3. Data synthesis and analysis

Data were extracted by two researchers. General characteristics of the study, study population, methodology, information on aggressive behaviour, information on behavioural, psychiatric and psychosocial factors and associations were extracted.

The outcome most fully adjusted for confounders was extracted. Where possible, odds ratios were reported or calculated. Otherwise, correlation or regression coefficients were presented. Where relevant, in order to correctly interpret results, the direction of association(s) was reversed.

Study type was noted as “informant report” if data were collected through questionnaires completed by or interviews held with informants, as “self‐report” if data were collected through questionnaires completed by or interviews held with people with intellectual disability themselves and as “retrospective case review” if data were collected from case files.

Data were extracted separately for five topographies of aggressive behaviour following the categories of the modified overt aggression scale (MOAS+) (Crocker et al., 2006; Sorgi et al., 1991); physically aggressive behaviour (behaviour that causes bodily harm to other people), verbally aggressive behaviour (shouting, swearing or making verbal insults), sexually aggressive behaviour (making sexually inappropriate statements, exposing oneself to others, inappropriately touching oneself or others, or engaging in coercive sexual activities), destructive behaviour (aggressive behaviour aimed at objects, or the destruction of property) or self‐injurious behaviour (behaviour that causes bodily harm to oneself). Aggressive behaviour that was not specified or specified as a combination of different topographies, was reported in the category “aggression in general.”

Behavioural factors include all reported topographies of aggressive behaviour and criminal behaviour.

Psychiatric factors were categorized as “psychiatric disorders” if the diagnosis was based on criteria outlined by the diagnostic and statistical manual (DSM) or international classification of diseases (ICD). Subcategories were created based on the ICD‐10 categorization. If a study reported an association with any psychiatric disorder, without specifying the disorder, it was classified as such. If the method of diagnosing was not specified, or when screening instruments or questionnaires were used, the results were categorized as “psychiatric symptoms.” When possible—for instance when screening instruments for a specific disorder were used—these were categorized according to the corresponding ICD‐10 categories of the respective disorders. Symptoms that were not specific to a single diagnostic category were classified as “aspecific psychiatric symptoms.” If a study reported associations with a total scale measuring symptoms of mental health problems, these were classified as “total psychiatric symptoms.”

Psychosocial factors can be described as “psychological or social variables, as well as factors pertaining to the interaction of the individual and the social environment” (Hall, 2018). These include life events, living situations, factors pertaining to social interactions and personal skills.

Considering the high heterogeneity of methodological approaches, populations, definitions, outcome measures and assessment methodologies, an overview of all associations will be provided in tables and results will be presented narratively.

2.4. Quality assessment

The methodological quality of the included studies was assessed using the “NIH quality assessment tool for observational cohort and cross‐sectional studies” (National Institutes of Health, 2014). After discussion of the criteria, quality assessment was performed by a single reviewer. In case of uncertainties, the second reviewer was consulted. The NIH quality assessment tool does not have a predefined cut off‐score for high or low quality. Therefore, a number of criteria have been set by the researchers. To be judged as a high‐quality study, publications had to score positively on at least seven of the 14 criteria. Furthermore, they had to score positively on three important criteria: (a) sample size justification or power calculation, (b) clearly defined, reliable and valid dependent and (c) independent variables. Tables 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 show the methodology quality of studies; high‐quality studies are depicted in bold, low‐quality studies are not in bold.

TABLE 1.

Summary of included publications

| Author(s) and country | Study sample | Data collection method | Type(s) of aggressive behaviour (instruments) | Psychosocial factor(s) (instruments) | Association | Outcome | Statistical analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Alexander et al. (2010), UK Low quality |

n = 138 adults (109M, 29F) with mild intellectual disability and offending behaviours in an inpatient service for offenders | Retrospective chart review | Physically aggressive behaviour (case file: defined as history of aggression, recorded as either present or absent) | Psychiatric diagnosis: personality disorder (ICD‐10 diagnosis derived from case file) | NS | OR = 1.53, CI [0.49; 4.83] | Univariate, odds ratio a |

| Verbally aggressive behaviour (case file: defined as history of aggression, recorded as either present or absent) | Psychiatric diagnosis: personality disorder (ICD‐10 diagnosis derived from case file) | NS | OR = 2.20, CI [0.50; 9.61] | Univariate, odds ratio a | |||

| Destructive behaviour (case file: defined as history of aggression, recorded as either present or absent) | Psychiatric diagnosis: personality disorder (ICD‐10 diagnosis derived from case file) | NS | OR = 1.51, CI [0.52; 4.42] | Univariate, odds ratio a | |||

| Self‐injurious behaviour (case file: defined as history of aggression, recorded as either present or absent) | Psychiatric diagnosis: personality disorder (ICD‐10 diagnosis derived from case file) | NS | OR = 1.47, CI [0.63; 3.41] | Univariate, odds ratio a | |||

| Sexually aggressive behaviour (case file: defined as history of aggression, recorded as either present or absent) | Psychiatric diagnosis: personality disorder (ICD‐10 diagnosis derived from case file) | NS | OR = 1.79, CI [0.91; 3.54] | Univariate, odds ratio a | |||

|

Alexander et al. (2015), UK Low quality |

n = 138 adults (109M, 29F) with mild intellectual disability and offending behaviours in an inpatient service for offenders | Retrospective chart review | Destructive behaviour (case file: defined as history of fire setting or conviction of arson in the case history) | Life events: past experience of any abuse (evidence of child or vulnerable adult protection by Social Services) | + | OR = 2.88, CI [1.21; 6.88] | Univariate, odds ratio a |

| Life events: past experience of sexual abuse (evidence of child or vulnerable adult protection by Social Services) | NS | OR = 1.93, CI [0.85; 4.39] | Univariate, odds ratio a | ||||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: PDD (ICD‐10 diagnosis derived from case file) | NS | OR = 0.50, CI [0.19; 1.34] | Univariate, odds ratio a | ||||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: psychosis (ICD‐10 diagnosis derived from case file) | NS | OR = 1.38, CI [0.52; 3.67] | Univariate, odds ratio a | ||||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: bipolar disorder (ICD‐10 diagnosis derived from case file) | NS | OR = 0.22, CI [0.03; 1.78] | Univariate, odds ratio a | ||||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: depressive disorder (ICD‐10 diagnosis derived from case file) | NS | OR = 1.39, CI [0.49; 3.94] | Univariate, odds ratio a | ||||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: substance dependence (ICD‐10 diagnosis derived from case file) | NS | OR = 1.93, CI [0.82; 4.51] | Univariate, odds ratio a | ||||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: personality disorder (ICD‐10 diagnosis derived from case file) | + | OR = 4.08, CI [1.54; 10.79] | Univariate, odds ratio a | ||||

| Criminal behaviour: history of convictions for violent offences (case file) | + | OR = 3.13, CI [1.36; 7.23] | Univariate, odds ratio a | ||||

| Criminal behaviour: history of convictions for destructive offences (case file) | + | OR = 185.42, CI [10.55; 3,259.22] | Univariate, odds ratio a | ||||

| Criminal behaviour: history of convictions for sex offences (case file) | NS | OR = 0.94, CI [0.34; 2.59] | Univariate, odds ratio a | ||||

| Aggressive behaviour: physical (case file: defined as a history of aggression to people, recorded as either present or absent) | NS | OR = 0.46, CI [0.13; 1.71] | Univariate, odds ratio a | ||||

| Aggressive behaviour: verbal (case file: defined as a history of verbal aggression, recorded as either present or absent) | NS | OR = 1.45, CI [0.16; 12.91] | Univariate, odds ratio a | ||||

| Aggressive behaviour: destructive (case file: defined as a history of aggression against property, recorded as either present or absent) | NS | OR = 0.41, CI [0.12; 1.37] | Univariate, odds ratio a | ||||

| Aggressive behaviour: sexual (case file: defined as a history of sexual aggression, recorded as either present or absent) | NS | OR = 1.90, CI [0.82; 4.38] | Univariate, odds ratio a | ||||

| Aggressive behaviour: self‐injurious (case file: defined as a history of aggression to self, recorded as either present or absent) | NS | OR = 2.39, CI [0.66; 8.60] | Univariate, odds ratio a | ||||

|

Allen et al. (2012), UK Low quality |

n = 707 adults (410M, 297F) with intellectual disability and challenging behaviour (M age = 42, range 18–93), living in different settings | Informant reports by primary carers | Destructive behaviour (Individual Schedule) | Psychiatric symptoms: affective/neurotic, possible organic (PAS‐ADD) | + | ρ = .081 | Univariate, Spearman rank correlation |

| Psychiatric symptoms: possible organic (PAS‐ADD) | + | ρ = .11 | Univariate, Spearman rank correlation | ||||

| Psychiatric symptoms: psychotic disorder (PAS‐ADD) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, Spearman rank correlation | ||||

| Self‐injurious behaviour (Individual Schedule) | Psychiatric symptoms: affective/neurotic (PAS‐ADD) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, Spearman rank correlation | |||

| Psychiatric symptoms: possible organic (PAS‐ADD) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, Spearman rank correlation | ||||

| Psychiatric symptoms: psychotic disorder (PAS‐ADD) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, Spearman rank correlation | ||||

| Aggressive behaviour in general (Individual Schedule) | Psychiatric symptoms: affective/neurotic (PAS‐ADD) | + | ρ = .10 | Univariate, Spearman rank correlation | |||

| Psychiatric symptoms: possible organic (PAS‐ADD) | + | ρ = .14 | Univariate, Spearman rank correlation | ||||

| Psychiatric symptoms: psychotic disorder (PAS‐ADD) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, Spearman rank correlation | ||||

|

Bernstein et al. (2015), Hungary High quality |

n = 50 adults (38M, 12F) with moderate, severe, or profound intellectual disability, residing in a developmental habilitation home (M age = 31.38, SD = 7.63, range 19–49) | Informant reports by care staff | Physically aggressive behaviour (CBI) | Psychiatric symptoms: mood (MIPQ‐S) | NS | ρ = .02 | Univariate, Spearman correlation |

| Psychiatric symptoms: interest/pleasure (MIPQ‐S) | NS | ρ = −.11 | Univariate, Spearman correlation | ||||

| Aggressive behaviour: general (BPI‐S) | + | ρ = .78 | Univariate, Spearman correlation | ||||

| Aggressive behaviour: self‐injurious (BPI‐S, CBI) | NS |

ρ = .27 (BPI‐S) ρ = .45 (CBI) |

Univariate, Spearman correlation | ||||

| Self‐injurious behaviour (BPI‐S, CBI) | Psychiatric symptoms: mood (MIPQ‐S) | NS |

ρ = −.17 (BPI‐S) ρ = −.12 (CBI) |

Univariate, Spearman correlation | |||

| Psychiatric symptoms: interest/pleasure (MIPQ‐S) | NS |

ρ = −.44 (BPI‐S) ρ = −.23 (CBI) |

Univariate, Spearman correlation | ||||

| Aggressive behaviour: physical (CBI) | NS | ρ = .45 | Univariate, Spearman correlation | ||||

| Aggressive behaviour: general (BPI‐S) | + | ρ = .57 | Univariate, Spearman correlation | ||||

| Aggressive behaviour in general (BPI‐S) | Psychiatric symptoms: mood (MIPQ‐S) | NS | ρ = .13 | Univariate, Spearman correlation | |||

| Psychiatric symptoms: interest/pleasure (MIPQ‐S) | NS | ρ = .01 | Univariate, Spearman correlation | ||||

| Aggressive behaviour: physical (CBI) | + | ρ = .78 | Univariate, Spearman correlation | ||||

| Aggressive behaviour: self‐injurious (CBI) | + | ρ = .57 | Univariate, Spearman correlation | ||||

|

Bowring et al. (2017), USA Low quality |

n = 265 adults (134M, 131F) with mild, moderate, severe, or profound intellectual disability who (had) received support from services (M age = 41.44, SD = 16.28) and lived in different settings | Informant reports by family members or care staff | Self‐injurious behaviour (BPI‐S) | Communication skills: non‐verbal b (Individual survey) | − | RR = 4.705, CI [1.953; 11.333] | Univariate, relative risk estimation |

| Communication skills: no clear speech b (Individual survey) | − | RR = 3.681, CI [1.378; 9.834] | Univariate, relative risk estimation | ||||

| Communication skills: limited understanding b (Individual survey) | − | RR = 3.658, CI [1.571; 8.52] | Univariate, relative risk estimation | ||||

| Adaptive behaviour: no daytime engagement b (Individual survey) | − | RR = 3.729, CI [1.48; 9.392] | Univariate, relative risk estimation | ||||

| Living situation: paid care (Individual survey) | + | RR = 3.023, CI [1.131; 8.079] | Univariate, relative risk estimation | ||||

| Living situation: with partner (Individual survey) | NS | RR = 0.301, CI [0.017; 5.202] | Univariate, relative risk estimation | ||||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: ASD (Individual survey) | NS | RR = 1.208, CI [0.454; 3.218] | Univariate, relative risk estimation | ||||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: any (Individual survey) | NS | RR = 2.256, CI [0.976; 5.212] | Univariate, relative risk estimation | ||||

| Aggressive behaviour: general (BPI‐S) | + | ρ = .253 | Univariate, Spearman corerlation | ||||

| Aggressive behaviour in general (BPI‐S) | Aggressive behaviour: self‐injurious (BPI‐S) | + | ρ = .253 | Univariate, Spearman corerlation | |||

| Communication skills: limited understanding b (Individual survey) | − | RR = 3.882, CI [1.761; 8.559] | Univariate, relative risk estimation | ||||

| Communication skills: non‐verbal b (Individual survey) | − | RR = 3.04, CI [1.372; 6.735] | Univariate, relative risk estimation | ||||

| Communication skills: no clear speech b (Individual survey) | NS | RR = 2.147, CI [0.932; 4.945] | Univariate, relative risk estimation | ||||

| Adaptive behaviour: no daytime engagement b (Individual survey) | NS | RR = 1.918, CI [0.86; 4.276] | Univariate, relative risk estimation | ||||

| Living situation: paid care (Individual survey) | NS | RR = 2.159, CI [0.91; 5.124] | Univariate, relative risk estimation | ||||

| Living situation: with partner (Individual survey) | NS | RR = 0.271, CI [0.016; 4.67] | Univariate, relative risk estimation | ||||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: any (Individual survey) | NS | RR = 1.034, CI [0.421; 2.537] | Univariate, relative risk estimation | ||||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: ASD (Individual survey) | + | RR = 3.383, CI [1.544; 7.414] | Univariate, relative risk estimation | ||||

|

Cervantes and Matson (2015), USA High quality |

n = 307 adults (156M, 151F) with severe or profound intellectual disability, residing in developmental centres (M age = 51.44, SD = 12.49, range 20–88) | Informant reports by care staff | Sexually aggressive behaviour (DASH‐II) | Psychiatric diagnosis: ASD (DSM−5, case file) | + | F(1, 303) = 10.87 | Multivariate, ANCOVA |

| Self‐injurious behaviour (DASH‐II) | Psychiatric diagnosis: ASD (DSM‐5, case file) | + | F(1, 303) = 13.73 | Multivariate, ANCOVA | |||

|

Clark et al. (2016), Canada High quality |

n = 215 adults with mild or moderate intellectual disability who (had) received services, living in different settings (M age = 39.90, SD = 11.87, range 18–65). Participants had to be able to understand English or French | Retrospective chart review + informant reports by case managers and persons well known to participants | Aggressive behaviour in general (MOAS) | Life events: victimization history (TESI, informant reports) | + | Path coefficient = 0.99, SE = 0.48, T = 2.05 | Multivariate, bootstrapped simple mediation analysis |

| Psychiatric symptoms: total mental health problems (RSMB) | + | Path coefficient = 0.27, SE = 0.04, T = 6.03 | Multivariate, bootstrapped simple mediation analysis | ||||

| Psychiatric symptoms: psychosis (RSMB) | + | Path coefficient = 0.86, SE = 0.23, T = 3.70 | Multivariate, bootstrapped multiple mediation analysis | ||||

| Psychiatric symptoms: personality disorder (RSMB) | + | Path coefficient = 0.65, SE = 0.23, T = 2.74 | Multivariate, bootstrapped multiple mediation analysis | ||||

| Psychiatric symptoms: depression (RSMB) | NS | Path coefficient = −0.37, SE = 0.27, T = −1.35 | Multivariate, bootstrapped multiple mediation analysis | ||||

| Self‐injurious behaviour (MOAS) | Life events: victimization history (TESI, informant reports) | + | t(213) = −2.05 | Univariate, t test | |||

| Psychiatric symptoms: total mental health problems (RSMB) | + | Not reported | Multivariate, bootstrapped simple mediation analysis | ||||

| Psychiatric symptoms: depression (RSMB) | + | r = .19 | Univariate, Pearson correlation | ||||

| Psychiatric symptoms: psychosis (RSMB) | + | r = .25 | Univariate, Pearson correlation | ||||

| Psychiatric symptoms: personality disorder (RSMB) | + | r = .28 | Univariate, Pearson correlation | ||||

|

Crocker et al. (2006), Canada Low quality |

n = 3,165 adults (1,633M, 1,527F) with mild, moderate, severe, or profound intellectual disability receiving services and living in different settings (M age = 40.63, SD = 13) | Informant reports by case managers and educators | Physically aggressive behaviour (MOAS) | Living situation: family (informant survey) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, χ 2‐test |

| Living situation: family‐type residence (informant survey) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, χ 2‐test | ||||

| Living situation: group home (informant survey) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, χ 2‐test | ||||

| Living situation: apartment (informant survey) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, χ 2‐test | ||||

| Living situation: other (informant survey) | + | Not reported | Univariate, χ 2‐test | ||||

| Criminal behaviour: history of arrest (informant survey: rated as either present or absent) | + | Not reported | Univariate, χ 2‐test | ||||

| Aggressive behaviour: verbal (MOAS) | + | ρ = .53 | Univariate, Spearman correlation | ||||

| Aggressive behaviour: destructive (MOAS) | + | ρ = .59 | Univariate, Spearman correlation | ||||

| Aggressive behaviour: sexual (MOAS) | + | ρ = .20 | Univariate, Spearman correlation | ||||

| Aggressive behaviour: self‐injurious (MOAS) | + | ρ = .35 | Univariate, Spearman correlation | ||||

| Verbally aggressive behaviour (MOAS) | Living situation: family (informant survey) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, χ 2‐test | |||

| Living situation: family‐type residence (informant survey) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, χ 2‐test | ||||

| Living situation: group home (informant survey) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, χ 2‐test | ||||

| Living situation: apartment (informant survey) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, χ 2‐test | ||||

| Living situation: other (informant survey) | + | Not reported | Univariate, χ 2‐test | ||||

| Criminal behaviour: history of arrest (informant survey: rated as either present or absent) | + | Not reported | Univariate, χ 2‐test | ||||

| Aggressive behaviour: physical (MOAS) | + | ρ = .53 | Univariate, Spearman correlation | ||||

| Aggressive behaviour: destructive (MOAS) | + | ρ = .54 | Univariate, Spearman correlation | ||||

| Aggressive behaviour: sexual (MOAS) | + | ρ = .21 | Univariate, Spearman correlation | ||||

| Aggressive behaviour: self‐injurious (MOAS) | + | ρ = .26 | Univariate, Spearman correlation | ||||

| Destructive behaviour (MOAS) | Living situation: family (informant survey) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, χ 2‐test | |||

| Living situation: family‐type residence (informant survey) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, χ 2‐test | ||||

| Living situation: group home (informant survey) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, χ 2‐test | ||||

| Living situation: apartment (informant survey) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, χ 2‐test | ||||

| Living situation: other (informant survey) | + | Not reported | Univariate, χ 2‐test | ||||

| Criminal behaviour: history of arrest (informant survey: rated as either present or absent) | + | Not reported | Univariate, χ 2‐test | ||||

| Aggressive behaviour: physical (MOAS) | + | ρ = .59 | Univariate, Spearman correlation | ||||

| Aggressive behaviour: verbal (MOAS) | + | ρ = .54 | Univariate, Spearman correlation | ||||

| Aggressive behaviour: sexual (MOAS) | + | ρ = .19 | Univariate, Spearman correlation | ||||

| Aggressive behaviour: self‐injurious (MOAS) | + | ρ = .38 | Univariate, Spearman correlation | ||||

| Sexually aggressive behaviour (MOAS) | Living situation: family (informant survey) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, χ 2‐test | |||

| Living situation: family‐type residence (informant survey) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, χ 2‐test | ||||

| Living situation: group home (informant survey) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, χ 2‐test | ||||

| Living situation: apartment (informant survey) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, χ 2‐test | ||||

| Living situation: other (informant survey) | + | Not reported | Univariate, χ 2‐test | ||||

| Criminal behaviour: history of arrest (informant survey: rated as either present or absent) | + | Not reported | Univariate, χ 2‐test | ||||

| Aggressive behaviour: physical (MOAS) | + | ρ = .20 | Univariate, Spearman correlation | ||||

| Aggressive behaviour: verbal (MOAS) | + | ρ = .21 | Univariate, Spearman correlation | ||||

| Aggressive behaviour: destructive (MOAS) | + | ρ = .19 | Univariate, Spearman correlation | ||||

| Aggressive behaviour: self‐injurious (MOAS) | + | ρ = .13 | Univariate, Spearman correlation | ||||

| Self‐injurious behaviour (MOAS) | Living situation: family (informant survey) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, χ 2‐test | |||

| Living situation: family‐type residence (informant survey) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, χ 2‐test | ||||

| Living situation: group home (informant survey) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, χ 2‐test | ||||

| Living situation: apartment (informant survey) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, χ 2‐test | ||||

| Living situation: other (informant survey) | + | Not reported | Univariate, χ 2‐test | ||||

| Criminal behaviour: history of arrest (informant survey: rated as either present or absent) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, χ 2‐test | ||||

| Aggressive behaviour: physical (MOAS) | + | ρ = .35 | Univariate, Spearman correlation | ||||

| Aggressive behaviour: verbal (MOAS) | + | ρ = .26 | Univariate, Spearman correlation | ||||

| Aggressive behaviour: destructive (MOAS) | + | ρ = .38 | Univariate, Spearman correlation | ||||

| Aggressive behaviour: sexual (MOAS) | + | ρ = .13 | Univariate, Spearman correlation | ||||

| Aggressive behaviour in general (MOAS) | Living situation: family (informant survey) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, χ 2‐test | |||

| Living situation: family‐type residence (informant survey) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, χ 2‐test | ||||

| Living situation: group home (informant survey) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, χ 2‐test | ||||

| Living situation: apartment (informant survey) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, χ 2‐test | ||||

| Living situation: other (informant survey) | + | Not reported | Univariate, χ 2‐test | ||||

| Criminal behaviour: history of arrest (informant survey: rated as either present or absent) | + | t(137.91) = −5.84 | Univariate, t test | ||||

|

Crocker et al. (2014), Canada High quality |

n = 296 adults (162M, 134F) with mild or moderate intellectual disability living in the community and receiving services (M age = 40.67, SD = 12.21, range 18–65). Participants had to be able to understand English or French | Retrospective chart review + self‐reports + informant reports by a case manager and significant others | Physically aggressive behaviour (MOAS) | Psychiatric diagnosis: number of mental disorders (case file) | NS | Incidence rate ratio = 1.450, CI [0.980; 2.146] | Multivariate, logistic regression |

| Psychiatric diagnosis: severity of mental disorders (SF‐36) | NS | Incidence rate ratio = 0.972, CI [0.936; 1.009] | Multivariate, logistic regression | ||||

| Verbally aggressive behaviour (MOAS) | Psychiatric diagnosis: number of mental disorders (case file) | + | Incidence rate ratio = 3.200, CI [1.294; 7.914] | Multivariate, logistic regression | |||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: severity of mental disorders (SF‐36) | + | Incidence rate ratio = 0.937, CI [0.890; 0.986] | Multivariate, logistic regression | ||||

| Destructive behaviour (MOAS) | Psychiatric diagnosis: number of mental disorders (case file) | NS | Incidence rate ratio = 1.258, CI [0.849; 1.863] | Multivariate, logistic regression | |||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: severity of mental disorders (SF‐36) | − | Incidence rate ratio = 0.956, CI [0.920; 0.993] | Multivariate, logistic regression | ||||

| Sexually aggressive behaviour (MOAS) | Psychiatric diagnosis: anxiety disorder (SF‐36, case file) | + | Incidence rate ratio = 3.224, CI [1.311; 7.923] | Multivariate, logistic regression | |||

|

Davies et al. (2015), UK High quality |

n = 96 adults (50M, 46F) with mild or moderate intellectual disability (M age = 39.68, SD = 13.32, range 18–79). Participants had to be able to complete the questionnaires | Self‐reports + informant reports by carers | Aggressive behaviour in general (CCB) | Psychiatric symptoms: alexithymia (self‐report using AQC) | NS | ρ = .133 | Univariate, Spearman correlation |

| Psychiatric symptoms: alexithymia (informant report using OAS) | + | ρ = .298 | Univariate, Spearman correlation | ||||

|

Didden et al. (2009), the Netherlands Low quality |

n = 39 adult inpatients of a specialized treatment unit, with mild intellectual disability (age range 19–51) | Retrospective chart review | Aggressive behaviour in general (ABCL) | Psychiatric symptoms: substance abuse (case file: use of much more than 14 (females) or 21 (males) standard units of alcohol per week, with similar criteria for drug use) | + | z = 2.187 | Univariate, Mann–Whitney analysis |

|

Drieschner et al. (2013), the Netherlands Low quality |

n = 218 adults (188M, 30F) with mild intellectual disability, living in residential treatment centres for adults with intellectual disability who display serious dangerous behaviour (M age = 33.8, SD = 11.5) | Informant reports | Physically aggressive behaviour (MOAS+) | Aggressive behaviour: verbal (MOAS+) | + | ρ = .70 | Univariate, Spearman correlation |

| Aggressive behaviour: destructive (MOAS+) | + | ρ = .73 | Univariate, Spearman correlation | ||||

| Aggressive behaviour: sexual (MOAS+) | + | ρ = .30 | Univariate, Spearman correlation | ||||

| Aggressive behaviour: self‐injurious (MOAS+) | + | ρ = .47 | Univariate, Spearman correlation | ||||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: ADHD (DSM‐IV) | + | Incidence rate ratio = 2.53 | Univariate, Mann–Whitney U‐test | ||||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: Borderline personality disorder (DSM‐IV) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, Mann–Whitney U‐test | ||||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: substance‐related disorder (DSM‐IV) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, Mann–Whitney U‐test | ||||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: psychotic disorder (DSM‐IV) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, Mann–Whitney U‐test | ||||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: mood or anxiety disorder (DSM‐IV) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, Mann–Whitney U‐test | ||||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: PDD (DSM‐IV) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, Mann–Whitney U‐test | ||||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: paraphilia (DSM‐IV) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, Mann–Whitney U‐test | ||||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: antisocial personality disorder (DSM‐IV) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, Mann–Whitney U‐test | ||||

| Criminal behaviour: admission on the basis of criminal law (informant reports) | ‐ | Incidence rate ratio = −1.86 | Univariate, Mann–Whitney U‐test | ||||

| Verbally aggressive behaviour (MOAS+) | Aggressive behaviour: physical (MOAS+) | + | ρ = .70 | Univariate, Spearman correlation | |||

| Aggressive behaviour: destructive (MOAS+) | + | ρ = .80 | Univariate, Spearman correlation | ||||

| Aggressive behaviour: sexual (MOAS+) | + | ρ = .35 | Univariate, Spearman correlation | ||||

| Aggressive behaviour: self‐injurious (MOAS+) | + | ρ = .39 | Univariate, Spearman correlation | ||||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: ADHD (DSM‐IV) | + | Incidence rate ratio = 1.88 | Univariate, Mann–Whitney U‐test | ||||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: Borderline personality disorder (DSM‐IV) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, Mann–Whitney U‐test | ||||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: substance‐related disorder (DSM‐IV) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, Mann–Whitney U‐test | ||||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: psychotic disorder (DSM‐IV) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, Mann–Whitney U‐test | ||||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: mood or anxiety disorder (DSM‐IV) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, Mann–Whitney U‐test | ||||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: PDD (DSM‐IV) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, Mann–Whitney U‐test | ||||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: paraphilia (DSM‐IV) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, Mann–Whitney U‐test | ||||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: antisocial personality disorder (DSM‐IV) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, Mann–Whitney U‐test | ||||

| Criminal behaviour: admission on the basis of criminal law (informant reports) | − | Incidence rate ratio = −1.59 | Univariate, Mann–Whitney U‐test | ||||

| Destructive behaviour (MOAS+) | Aggressive behaviour: physical (MOAS+) | + | ρ = .73 | Univariate, Spearman correlation | |||

| Aggressive behaviour: verbal (MOAS+) | + | ρ = .80 | Univariate, Spearman correlation | ||||

| Aggressive behaviour: sexual (MOAS+) | + | ρ = .29 | Univariate, Spearman correlation | ||||

| Aggressive behaviour: self‐injurious (MOAS+) | + | ρ = .50 | Univariate, Spearman correlation | ||||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: ADHD (DSM‐IV) | + | Incidence rate ratio = 2.75 | Univariate, Mann–Whitney U‐test | ||||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: Borderline personality disorder (DSM‐IV) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, Mann–Whitney U‐test | ||||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: substance‐related disorder (DSM‐IV) | − | Incidence rate ratio = −1.67 | Univariate, Mann–Whitney U‐test | ||||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: psychotic disorder (DSM‐IV) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, Mann–Whitney U‐test | ||||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: mood or anxiety disorder (DSM‐IV) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, Mann–Whitney U‐test | ||||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: PDD (DSM‐IV) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, Mann–Whitney U‐test | ||||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: paraphilia (DSM‐IV) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, Mann–Whitney U‐test | ||||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: antisocial personality disorder (DSM‐IV) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, Mann–Whitney U‐test | ||||

| Criminal behaviour: admission on the basis of criminal law (informant reports) | − | Incidence rate ratio = −2.06 | Univariate, Mann–Whitney U‐test | ||||

| Sexually aggressive behaviour (MOAS+) | Aggressive behaviour: physical (MOAS+) | + | ρ = .30 | Univariate, Spearman correlation | |||

| Aggressive behaviour: verbal (MOAS+) | + | ρ = .35 | Univariate, Spearman correlation | ||||

| Aggressive behaviour: destructive (MOAS+) | + | ρ = .29 | Univariate, Spearman correlation | ||||

| Aggressive behaviour: self‐injurious (MOAS+) | + | ρ = .24 | Univariate, Spearman correlation | ||||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: ADHD (DSM‐IV) | + | Incidence rate ratio = 3.08 | Univariate, Mann–Whitney U‐test | ||||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: Borderline personality disorder (DSM‐IV) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, Mann–Whitney U‐test | ||||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: substance‐related disorder (DSM‐IV) | − | Incidence rate ratio = −1.45 | Univariate, Mann–Whitney U‐test | ||||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: psychotic disorder (DSM‐IV) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, Mann–Whitney U‐test | ||||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: mood or anxiety disorder (DSM‐IV) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, Mann–Whitney U‐test | ||||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: PDD (DSM‐IV) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, Mann–Whitney U‐test | ||||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: paraphilia (DSM‐IV) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, Mann–Whitney U‐test | ||||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: antisocial personality disorder (DSM‐IV) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, Mann–Whitney U‐test | ||||

| Criminal behaviour: admission on the basis of criminal law (informant reports) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, Mann–Whitney U‐test | ||||

| Self‐injurious behaviour (MOAS+) | Aggressive behaviour: physical (MOAS+) | + | ρ = .47 | Univariate, Spearman correlation | |||

| Aggressive behaviour: verbal (MOAS+) | + | ρ = .39 | Univariate, Spearman correlation | ||||

| Aggressive behaviour: destructive (MOAS+) | + | ρ = .50 | Univariate, Spearman correlation | ||||

| Aggressive behaviour: sexual (MOAS+) | + | ρ = .24 | Univariate, Spearman correlation | ||||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: ADHD (DSM‐IV) | + | Incidence rate ratio = 5.71 | Univariate, Mann–Whitney U‐test | ||||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: borderline personality disorder (DSM‐IV) | + | Incidence rate ratio = 4.29 | Univariate, Mann–Whitney U‐test | ||||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: substance‐related disorder (DSM‐IV) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, Mann–Whitney U‐test | ||||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: psychotic disorder (DSM‐IV) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, Mann–Whitney U‐test | ||||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: mood or anxiety disorder (DSM‐IV) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, Mann–Whitney U‐test | ||||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: PDD (DSM‐IV) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, Mann–Whitney U‐test | ||||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: paraphilia (DSM‐IV) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, Mann–Whitney U‐test | ||||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: antisocial personality disorder (DSM‐IV) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, Mann–Whitney U‐test | ||||

| Criminal behaviour: admission on the basis of criminal law (informant reports) | − | Incidence rate ratio = −2.85 | Univariate, Mann–Whitney U‐test | ||||

| Aggressive behaviour in general (MOAS+) | Psychiatric diagnosis: ADHD (DSM‐IV) | + | Incidence rate ratio = 2.28 | Univariate, Mann–Whitney U‐test | |||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: Borderline personality disorder (DSM‐IV) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, Mann–Whitney U‐test | ||||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: substance‐related disorder (DSM‐IV) | − | Incidence rate ratio = −1.57 | Univariate, Mann–Whitney U‐test | ||||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: psychotic disorder (DSM‐IV) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, Mann–Whitney U‐test | ||||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: mood or anxiety disorder (DSM‐IV) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, Mann–Whitney U‐test | ||||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: PDD (DSM‐IV) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, Mann–Whitney U‐test | ||||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: paraphilia (DSM‐IV) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, Mann–Whitney U‐test | ||||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: antisocial personality disorder (DSM‐IV) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, Mann–Whitney U‐test | ||||

| Criminal behaviour: admission on the basis of criminal law (informant reports) | − | Incidence rate ratio = −1.70 | Univariate, Mann–Whitney U‐test | ||||

|

Esbensen and Benson (2006), USA High quality |

n = 104 adults (58M, 46F) with mild, moderate, or severe intellectual disability (M age = 42.0, SD = 12.4, range 21–79 years) and living in different settings | Informant reports by care staff | Aggressive behaviour in general (SIB‐R externalized) | Life events: positive life events (LES) | NS | r = .05 | Univariate, Pearson correlation |

| Life events: negative life events (LES) | + | r = .39 | Univariate, Pearson correlation | ||||

| Life events: total life events (LES) | + | r = .24 | Univariate, Pearson correlation | ||||

|

Hartley and MacLean (2007), USA High quality |

n = 132 adults ≥50 years (66M, 66F, M age = 59.22, SD = 7.60), with mild, moderate, severe, or profound intellectual disability receiving services and living in different settings | Informant reports by care staff | Physically aggressive behaviour (ICAP) | Adaptive behaviour: motor skills, social and communication skills, personal living skills, community living skills (ICAP Broad Independence age equivalent) | − | τ = −.32 | Univariate, Kendall Tau C correlation |

| Destructive behaviour (ICAP) | Adaptive behaviour: motor skills, social and communication skills, personal living skills, community living skills (ICAP Broad Independence age equivalent) | − | τ = −.29 | Univariate, Kendall Tau C correlation | |||

|

Hemmings et al. (2006), UK High quality |

n = 214 adults (108M, 106F) with mild/moderate or severe/profound intellectual disability (range 18–85 years), living in a variety of settings | Retrospective chart review + self‐reports | Destructive behaviour (DAS) | Psychiatric symptoms: low energy (PAS‐ADD Checklist) | + | OR = 4.36, CI [1.43; 13.3] | Multivariate, stepwise logistic regression |

| Psychiatric symptoms: delayed sleep (PAS‐ADD Checklist) | + | OR = 3.28, CI [1.1; 9.76] | Multivariate, stepwise logistic regression | ||||

| Psychiatric symptoms: anhedonia, sad or down, fearful/panicky, repetitive actions, too high or happy, suicidal, loss of appetite, weight change, loss of confidence, avoiding social contact, worthlessness, early waking, restlessness, irritable mood, loss of self‐care, odd language (PAS‐ADD Checklist) | NS | Not reported | Multivariate, stepwise logistic regression | ||||

| Social skills: social functioning (DAS) | − | OR = 4.09, CI [1.7; 9.82] | Multivariate, stepwise logistic regression | ||||

| Self‐injurious behaviour (DAS) | Psychiatric symptoms: irritable mood (PAS‐ADD Checklist) | + | OR = 5.52, CI [1.99; 15.3] | Multivariate, stepwise logistic regression | |||

| Psychiatric symptoms: suicidal (PAS‐ADD Checklist) | + | OR = 5.19, CI [1.22; 22.1] | Multivariate, stepwise logistic regression | ||||

| Psychiatric symptoms: low energy, anhedonia, sad or down, fearful/panicky, repetitive actions, too high or happy, loss of appetite, weight change, loss of confidence, avoiding social contact, worthlessness, delayed sleep, early waking, restlessness, loss of self‐care, odd language (PAS‐ADD Checklist) | NS | Not reported | Multivariate, stepwise logistic regression | ||||

| Social skills: social functioning (DAS) | NS | Not reported | Multivariate, stepwise logistic regression | ||||

| Aggressive behaviour in general (DAS) | Psychiatric symptoms: early waking (PAS‐ADD Checklist) | + | OR = 4.04, CI [1.08; 15.1] | Multivariate, stepwise logistic regression | |||

| Psychiatric symptoms: low energy (PAS‐ADD Checklist) | + | OR = 3.72, CI [1.21; 11.4] | Multivariate, stepwise logistic regression | ||||

| Psychiatric symptoms: irritable mood (PAS‐ADD Checklist) | + | OR = 3.0, CI [1.16; 7.8] | Multivariate, stepwise logistic regression | ||||

| Psychiatric symptoms: anhedonia, sad or down, fearful/panicky, repetitive actions, too high or happy, suicidal, loss of appetite, weight change, loss of confidence, avoiding social contact, worthlessness, delayed sleep, restlessness, loss of self‐care, odd language (PAS‐ADD Checklist) | NS | Not reported | Multivariate, stepwise logistic regression | ||||

| Social skills: social functioning (DAS) | NS | Not reported | Multivariate, stepwise logistic regression | ||||

|

Horovitz et al. (2013), USA High quality |

n = 175 adults (94M, 81F) with mild, moderate, severe, or profound intellectual disability residing in developmental centres (M age = 52.18, SD = 13.41, range 20–87 years) | Informant reports by care staff | Self‐injurious behaviour (ASD‐BPA) | Psychiatric diagnosis: ASD (DSM‐IV‐TR and ICD‐10) | + | F(1, 170) = 11.28 | Multivariate, two‐way between‐subjects ANOVA |

| Aggressive behaviour in general (ASD‐BPA) | Psychiatric diagnosis: ASD (DSM‐IV‐TR and ICD‐10) | NS | F(1, 170) = 2.11 | Multivariate, two‐way between‐subjects ANOVA | |||

|

Hurley (2008), USA Low quality |

n = 300 patients with mild, moderate, severe, or profound intellectual disability seen in a specialty clinic of a medical centre | Retrospective chart review | Self‐injurious behaviour (case file: any form of self‐injurious behaviour, excluding suicidality but including skin picking) | Psychiatric diagnosis: depression (DSM‐IV, DSM‐IV‐TR diagnosis derived from case file) | + | OR = 8.53, CI [1.09; 66.75] | Univariate, odds ratio a |

| Aggressive behaviour in general (case file: any physical aggression towards others, objects, or verbal threats of aggression) | Psychiatric diagnosis: depression (DSM‐IV, DSM‐IV‐TR diagnosis derived from case file) | + | OR = 21.02, CI [2.73; 162.09] | Univariate, odds ratio a | |||

|

Koritsas and Iacono (2015), Australia High quality |

n = 74 adults (49M, 25F) with intellectual disability (M age = 36.56, SD = 13.14, range 19–73 years) and living in different settings | Informant reports by care staff + brief observation | Aggressive behaviour in general (Interview Protocol, ICAP, CCB) | Psychiatric symptoms: anxiety (DBC‐A) | + | β = 0.52, SE = 0.06, t = 4.16 | Multivariate, multiple regression |

| Psychiatric symptoms: disruption (DBC‐A) | + | ρ = .28 | Univariate, Spearman correlation | ||||

| Psychiatric symptoms: total (DBC‐A) | + | ρ = .24 | Univariate, Spearman correlation | ||||

| Psychiatric symptoms: depressive (DBC‐A) | NS | β = −0.16, SE = 0.03, t = −1.36 | Multivariate, multiple regression | ||||

| Psychiatric symptoms: self‐absorbed (DBC‐A) | NS | ρ = .19 | Univariate, Spearman correlation | ||||

| Psychiatric symptoms: communication disturbance (DBC‐A) | NS | ρ = .12 | Univariate, Spearman correlation | ||||

| Psychiatric symptoms: social relating (DBC‐A) | NS | ρ = .02 | Univariate, Spearman correlation | ||||

| Communication skills: ability to make needs known (informant report about communication forms and functions, combined with brief observations. Overall judgment of communication skills was determined by a speech pathologist based on these instruments) | NS | ρ = .06 | Univariate, Spearman correlation | ||||

| Living situation: with parents (compared to not living with parents) (questionnaire) | NS | ρ = .14 | Univariate, Spearman correlation | ||||

| Aggressive behaviour: learned function of aggressive behaviour (sensory) (MAS) | NS | β = −0.22, SE = 0.02, t = −1.78 | Multivariate, multiple regression | ||||

| Aggressive behaviour: learned function of aggressive behaviour (escape) (MAS) | NS | β = −0.06, SE = 0.03, t = 0.41 | Multivariate, multiple regression | ||||

| Aggressive behaviour: learned function of aggressive behaviour (attention) (MAS) | NS | β = 0.14, SE = 0.03, t = −0.32 | Multivariate, multiple regression | ||||

| Aggressive behaviour: learned function of aggressive behaviour (tangible) (MAS) | NS | ρ = .18 | Univariate, Spearman correlation | ||||

|

Larson et al. (2011), UK Low quality |

n = 60 adults (31M, 29F) with mild or moderate intellectual disability, that had to be able to read and respond to the questionnaire independently; n = 39 supporting persons |

Informant reports by supporting persons + self‐reports | Aggressive behaviour in general (questionnaire: not specified, challenging behaviour selected from a list of commonly occurring examples of challenging behaviour) | Psychiatric symptoms: attachment style (questionnaire: secure, insecure‐anxious/ambivalent, or insecure‐avoidant) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, χ 2‐test |

| Self‐injurious behaviour (questionnaire: behaviour not specified, challenging behaviour selected from a list of commonly occurring examples of challenging behaviour) | Psychiatric symptoms: attachment style (questionnaire: secure, insecure‐anxious/ambivalent, or insecure‐avoidant) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, χ 2‐test | |||

|

Lindsay et al. (2013), UK Low quality |

n = 477 adults referred to maximum secure services for antisocial or offending behaviour | Retrospective chart review | Physically aggressive behaviour (case file: behaviour leading to referral to maximum secure services | Psychiatric diagnosis: ADHD (case file) | + | OR = 1.76, CI [1.06; 2.93] | Univariate, odds ratio a |

| Verbally aggressive behaviour (case file: behaviour leading to referral to maximum secure services) | Psychiatric diagnosis: ADHD (case file) | NS | OR = 0.85, CI [0.49; 1.46] | Univariate, odds ratio a | |||

| Destructive behaviour (case file: behaviour leading to referral to maximum secure services) | Psychiatric diagnosis: ADHD (case file) | + | OR = 1.77, CI [1.00; 3.14] | Univariate, odds ratio a | |||

| Sexually aggressive behaviour (case file: behaviour leading to referral to maximum secure services) | Psychiatric diagnosis: ADHD (case file) | NS |

Contact sex OR = 0.81, CI [0.38; 1.71] Non‐contact sex OR = 0.72, CI [0.33; 1.58] |

Univariate, odds ratio a | |||

|

Lundqvist (2013), Sweden Low quality |

n = 915 adults (504M, 411F) with mild, moderate, or severe/profound intellectual disability receiving care from local health authorities and living in different settings (M age = 43.4, SD = 14.8, range 18–87 years) | Informant reports by care staff | Self‐injurious behaviour (BPI) | Psychiatric symptoms: autism (questionnaire based on the ICF) | + | OR = 1.70, CI [1.03; 2.80] | Multivariate, backward stepwise likelihood ratio multiple logistic regression |

| Psychiatric symptoms: schizophrenia (questionnaire based on the ICF) | NS | OR = 1.61, CI [0.51; 5.13] | Univariate, binary logistic regression | ||||

| Psychiatric symptoms: psychosis (questionnaire based on the ICF) | NS | OR = 0.00, CI not reported | Univariate, binary logistic regression | ||||

| Psychiatric symptoms: depression (questionnaire based on the ICF) | NS | OR = 0.28, CI [0.03; 2.22] | Univariate, binary logistic regression | ||||

| Psychiatric symptoms: OCD (questionnaire based on the ICF) | NS | OR = 0.64, CI [0.13; 3.08] | Univariate, binary logistic regression | ||||

| Psychiatric symptoms: ADHD (questionnaire based on the ICF) | NS | Not reported | Multivariate, backward stepwise likelihood ratio multiple logistic regression | ||||

| Psychiatric symptoms: general psychopathology (questionnaire based on the ICF) | NS | Not reported | Multivariate, backward stepwise likelihood ratio multiple logistic regression | ||||

| Communication skills: communicating in writing (questionnaire based on the ICF) | NS | Not reported | Multivariate, backward stepwise likelihood ratio multiple logistic regression | ||||

| Communication skills: communicating with speech (questionnaire based on the ICF) | NS | Not reported | Multivariate, backward stepwise likelihood ratio multiple logistic regression | ||||

| Communication skills: communicating with signs (questionnaire based on the ICF) | NS | Not reported | Multivariate, backward stepwise likelihood ratio multiple logistic regression | ||||

| Communication skills: communicating with gestures (questionnaire based on the ICF) | NS | Not reported | Multivariate, backward stepwise likelihood ratio multiple logistic regression | ||||

| Communication skills: communicating with sounds (questionnaire based on the ICF) | NS | Not reported | Multivariate, backward stepwise likelihood ratio multiple logistic regression | ||||

| Communication skills: communicating with pictures (questionnaire based on the ICF) | + | OR = 1.93, CI [1.21; 3.09] | Multivariate, backward stepwise likelihood ratio multiple logistic regression | ||||

| Social skills: group functioning (questionnaire based on the ICF) | NS | Not reported | Multivariate, backward stepwise likelihood ratio multiple logistic regression | ||||

| Social skills: initiating social interaction (questionnaire based on the ICF, rated on a five‐point scale from never to always) | NS | Not reported | Multivariate, backward stepwise likelihood ratio multiple logistic regression | ||||

| Aggressive behaviour in general (BPI) | Psychiatric symptoms: autism (questionnaire based on the ICF) | + | OR = 1.78, CI [1.14; 2.77] | Multivariate, backward stepwise likelihood ratio multiple logistic regression | |||

| Psychiatric symptoms: schizophrenia (questionnaire based on the ICF) | NS | OR = 1.92, CI [0.62; 6.01] | Univariate, binary logistic regression | ||||

| Psychiatric symptoms: psychosis (questionnaire based on the ICF) | NS | OR = 2.40, CI [0.64; 9.01] | Univariate, binary logistic regression | ||||

| Psychiatric symptoms: depression (questionnaire based on the ICF) | NS | OR = 2.40, CI [0.64; 9.01] | Univariate, binary logistic regression | ||||

| Psychiatric symptoms: OCD (questionnaire based on the ICF) | NS | OR = 0.96, CI [0.24; 3.85] | Univariate, binary logistic regression | ||||

| Psychiatric symptoms: ADHD (questionnaire based on the ICF) | NS | OR = 1.15, CI [0.55; 2.38] | Univariate, binary logistic regression | ||||

| Psychiatric symptoms: general psychopathology (questionnaire based on the ICF) | NS | Not reported | Multivariate, backward stepwise likelihood ratio multiple logistic regression | ||||

| Communication skills: communicating in writing (questionnaire based on the ICF) | NS | OR = 1.12, CI [0.79; 1.58] | Univariate, binary logistic regression | ||||

| Communication skills: communicating with speech (questionnaire based on the ICF) | NS | Not reported | Multivariate, backward stepwise likelihood ratio multiple logistic regression | ||||

| Communication skills: communicating with signs (questionnaire based on the ICF) | + | OR = 2.28, CI [1.49; 3.49] | Multivariate, backward stepwise likelihood ratio multiple logistic regression | ||||

| Communication skills: communicating with gestures (questionnaire based on the ICF) | NS | Not reported | Multivariate, backward stepwise likelihood ratio multiple logistic regression | ||||

| Communication skills: communicating with sounds (questionnaire based on the ICF) | NS | Not reported | Multivariate, backward stepwise likelihood ratio multiple logistic regression | ||||

| Communication skills: communicating with pictures (questionnaire based on the ICF) | NS | Not reported | Multivariate, backward stepwise likelihood ratio multiple logistic regression | ||||

| Social skills: group functioning (questionnaire based on the ICF) | − | OR = 0.54, CI [0.46; 0.64] | Multivariate, backward stepwise likelihood ratio multiple logistic regression | ||||

| Social skills: initiating social interaction (questionnaire based on the ICF, rated on a five‐point scale from never to always) | + | OR = 1.27, CI [1.10; 1.48] | Multivariate, backward stepwise likelihood ratio multiple logistic regression | ||||

|

Lunsky et al. (2012), Canada Low quality |

n = 747 adults with mild or moderate/severe intellectual disability that have experienced crisis and living in different settings | Retrospective chart review + informant reports by care staff | Physically aggressive behaviour (case file, informant report: written description of what led up to the crisis, the crisis itself and the outcome of the crisis) | Criminal behaviour: history of legal involvement (case file) | NS | b = −0.247, OR = 0.781, CI [0.477; 1.280] | Multivariate, logistic regressions |

| Psychiatric diagnosis: autism (case file) | NS | b = −0.329, OR = 0.720, CI [0.479; 1.081] | Multivariate, logistic regressions | ||||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: substance abuse disorder (case file) | NS | b = −0.714, OR = 0.490, CI [0.124; 1.930] | Multivariate, logistic regressions | ||||

| Living situation: minimal support (compared to group home) (case file) | − | b = −0.617, OR = 0.540, CI [0.337; 0.864] | Multivariate, logistic regressions | ||||

| Living situation: with family (compared to group home) (case file) | NS | b = −0.245, OR = 0.783, CI [0.496; 1.235] | Multivariate, logistic regressions | ||||

| Life events: negative life events (modified PAS‐ADD Checklist) | NS |

One life event b = 0.010, OR = 1.010, CI [0.645; 1.583] Two or more life events b = 0.098, OR = 1.103, CI [0.719; 1.693] |

Multivariate, logistic regressions | ||||

| Destructive behaviour (case file, informant report: written description of what led up to the crisis, the crisis itself and the outcome of the crisis) | Criminal behaviour: history of legal involvement (case file) | + | χ 2(1) = 6.428 | Univariate, χ 2‐test | |||

| Self‐injurious behaviour (case file, informant report: written description of what led up to the crisis, the crisis itself and the outcome of the crisis) | Criminal behaviour: history of legal involvement (case file) | + | χ 2(1) = 5.966 | Univariate, χ 2‐test | |||

|

Matson and Rivet (2008), USA High quality |

n = 298 adults (167M, 131F) with mild, moderate, severe, or profound intellectual disability residing in a developmental centre (M age = 52.03, SD = 12.78, range 21–88 years) | Informant reports by care staff | Self‐injurious behaviour (ASD‐BPA) | Psychiatric symptoms: restricted/repetitive behaviour (ASD‐DA) | + | B = 0.11, SE = 0.03, β = 0.32 | Multivariate, multiple regression |

| Psychiatric symptoms: social impairment (ASD‐DA) | NS | B = 0.02, SE = 0.02, β = 0.10 | Multivariate, multiple regression | ||||

| Psychiatric symptoms: communication impairment (ASD‐DA) | NS | B = −0.03, SE = 0.03, β = −0.09 | Multivariate, multiple regression | ||||

| Aggressive behaviour in general (ASD‐BPA) | Psychiatric symptoms: communication impairment (ASD‐DA) | + | B = −0.13, SE = 0.06, β = −0.21 | Multivariate, multiple regression | |||

| Psychiatric symptoms: social impairment (ASD‐DA) | NS | B = 0.05, SE = 0.03, β = 0.18 | Multivariate, multiple regression | ||||

| Psychiatric symptoms: restricted/repetitive behaviour (ASD‐DA) | NS | B = 0.05, SE = 0.06, β = 0.09 | Multivariate, multiple regression | ||||

|

Matson et al. (2009), USA High quality |

n = 257 adults (139M, 118F) with severe or profound intellectual disability, living in a developmental centre (M age = 49.78, SD = 11.83, range 20–81 years) | Informant reports by care staff | Self‐injurious behaviour (ASD‐BPA) | Social skills: general positive social skills (MESSIER) | − | B = −0.01, SE = 0.00, β = −0.54 | Multivariate, multiple regression |

| Social skills: general negative social skills (MESSIER) | NS | B = 0.01, SE = 0.01, β = 0.20 | Multivariate, multiple regression | ||||

| Aggressive behaviour in general (ASD‐BPA) | Social skills: general positive social skills (MESSIER) | − |

B = −0.04, SE = 0.01, β = −0.62 |

Multivariate, multiple regression | |||

| Social skills: general negative social skills (MESSIER) | + |

B = 0.11, SE = 0.03, β = 0.61 |

Multivariate, multiple regression | ||||

|

Nøttestad and Linaker (2002), Norway Low quality |

n = 22 adults with mild, moderate, severe, or profound intellectual disability, displaying physically aggressive behaviour (M = 37, range 22–75) n = 41 controls with intellectual disability (M age = 44, range 22–75 years) and living in different settings |

Informant reports by caretakers | Physically aggressive behaviour (caretaker reports: participant attacked people in the previous year) | Aggressive behaviour: destructive (caretaker reports: attacks on objects/property in the previous year) | + | Not reported | Univariate, Mann–Whitney U‐test |

| Aggressive behaviour: self‐injurious (caretaker reports: behaviour not specified) | + | Not reported | Univariate, Mann–Whitney U‐test | ||||

| Destructive behaviour (caretaker reports: attacks on property in the previous year) | Aggressive behaviour: physical (caretaker reports) | + | Not reported | Univariate, Mann–Whitney U‐test | |||

| Self‐injurious behaviour (caretaker reports: behaviour not specified) | Aggressive behaviour: physical (caretaker reports: attacks on people in the previous year) | + | Not reported | Univariate, Mann–Whitney U‐test | |||

|

Novaco and Taylor (2004), UK High quality |

129 male adults with intellectual disability residing in a forensic service (M age = 33.2, SD = 11.6) | Self‐reports + retrospective case review + informant ratings by staff | Physically aggressive behaviour (case file: defined as an act that resulted in or could potentially have resulted in physical injury, displayed since admission) | Personality type: psychoticism (EPQ‐R Short Scale) | NS | B = 0.0121, SE = 0.019, β = 0.064, t = 0.63 | Multivariate, hierarchical regression |

| Personality type: neuroticism (EPQ‐R Short Scale) | NS | B = 0.0114, SE = 0.008, β = 0.132, t = 1.35 | Multivariate, hierarchical regression | ||||

| Personality type: lie (EPQ‐R Short Scale) | NS | B = −0.0122, SE = 0.010, β = −0.125, t = 1.28 | Multivariate, hierarchical regression | ||||

| Personality type: extraversion (EPQ‐R Short Scale) | + | B = 0.0245, SE = 0.010, β = 0.237, t = 2.55 | Multivariate, hierarchical regression | ||||

| Self‐reported anger (NAS, PI, STAXI State Anger) | + |

NAS B = 0.0078, SE = 003, β = 0.381, t = 3.08 |

Multivariate, hierarchical regression | ||||

| NS |

PI B = −0.0018, SE = 0.002, β = −0.085, t = 0.74 |

Multivariate, hierarchical regression | |||||

| NS |

STAXI B = −0.0129, SE = 0.008, β = −0.150, t = 1.55 |

Multivariate, hierarchical regression | |||||

|

Owen et al. (2004), UK Low quality |

n = 93 adults (61M, 32F) with intellectual disability living in a long‐stay residential hospital (M age = 55.2, SD = 12.7, range 24–93 years) | Informant reports by care staff | Self‐injurious behaviour (BPI) | Life events: negative life events (LEL) | NS | r(93) = .09 | Univariate, Pearson correlation |

| Aggressive behaviour in general (BPI) | Life events: negative life events (LEL) | + | r(88) = .27 | Multivariate, Pearson partial correlation | |||

|

Phillips and Rose (2010), UK Low quality |

n = 20 adults (15M, 5F) with mild intellectual disability and challenging behaviour experiencing placement breakdown (M age = 47.9, range 25.3–65.7 years) n = 23 adults (17M, 6F) with mild intellectual disability and challenging behaviour, that did not experience placement breakdown (M age = 43.2, range 22.7–79.2 years). All participants were living in residential facilities |

Informant reports by care staff | Physically aggressive behaviour (DAS‐B) | Life events: moves between community services (informant reports) | NS | OR = 1.19, CI [0.23; 6.11] | Univariate, odds ratio a |

|

Rojahn et al. (2004), USA Low quality |

n = 180 adults (97M, 83F) with mild, moderate, severe, or profound intellectual disability residing at a developmental centre (M age = 50.6, SD = 14.5, range 20–91 years) | Informant reports by care staff | Self‐injurious behaviour (BPI) | Aggressive behaviour: general (BPI) | + | ρ = .25 | Univariate, Spearman rank correlation |

| Psychiatric symptoms: mania (DASH‐II) | + | ρ = .18 | Univariate, Spearman rank correlation | ||||

| Psychiatric symptoms: PDD/autism (DASH‐II) | + | ρ = .19 | Univariate, Spearman rank correlation | ||||

| Psychiatric symptoms: stereotypies/tics (DASH‐II) | + | ρ = .19 | Univariate, Spearman rank correlation | ||||

| Psychiatric symptoms: organic syndromes (DASH‐II) | + | ρ = .24 | Univariate, Spearman rank correlation | ||||

| Psychiatric symptoms: impulse control (DASH‐II) | + | ρ = .17 | Univariate, Spearman rank correlation | ||||

| Psychiatric symptoms: self‐injurious behaviour (DASH‐II) | + | ρ = .27 | Univariate, Spearman rank correlation | ||||

| Psychiatric symptoms: eating disorder (DASH‐II) | + | ρ = .15 | Univariate, Spearman rank correlation | ||||

| Psychiatric symptoms: sexual disorder (DASH‐II) | + | ρ = .18 | Univariate, Spearman rank correlation | ||||

| Psychiatric symptoms: total (DASH‐II) | + | ρ = .27 | Univariate, Spearman rank correlation | ||||

| Psychiatric symptoms: anxiety (DASH‐II) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, Spearman rank correlation | ||||

| Psychiatric symptoms: schizophrenia (DASH‐II) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, Spearman rank correlation | ||||

| Psychiatric symptoms: elimination disorder (DASH‐II) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, Spearman rank correlation | ||||

| Psychiatric symptoms: sleep disorder (DASH‐II) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, Spearman rank correlation | ||||

| Aggressive behaviour in general (BPI) | Aggressive behaviour: self‐injurious (BPI) | + | ρ = .25 | Univariate, Spearman rank correlation | |||

| Psychiatric symptoms: total (DASH‐II) | + | ρ = .25 | Univariate, Spearman rank correlation | ||||

| Psychiatric symptoms: depression (DASH‐II) | + | ρ = .16 | Univariate, Spearman rank correlation | ||||

| Psychiatric symptoms: mania (DASH‐II) | + | ρ = .20 | Univariate, Spearman rank correlation | ||||

| Psychiatric symptoms: impulse control (DASH‐II) | + | ρ = .33 | Univariate, Spearman rank correlation | ||||

| Psychiatric symptoms: self‐injurious behaviour (DASH‐II) | + | ρ = .25 | Univariate, Spearman rank correlation | ||||

| Psychiatric symptoms: anxiety (DASH‐II) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, Spearman rank correlation | ||||

| Psychiatric symptoms: PDD/autism(DASH‐II) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, Spearman rank correlation | ||||

| Psychiatric symptoms: schizophrenia (DASH‐II) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, Spearman rank correlation | ||||

| Psychiatric symptoms: stereotypies/tics (DASH‐II) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, Spearman rank correlation | ||||

| Psychiatric symptoms: organic syndromes (DASH‐II) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, Spearman rank correlation | ||||

| Psychiatric symptoms: elimination disorder (DASH‐II) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, Spearman rank correlation | ||||

| Psychiatric symptoms: eating disorder (DASH‐II) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, Spearman rank correlation | ||||

| Psychiatric symptoms: sleep disorder (DASH‐II) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, Spearman rank correlation | ||||

| Psychiatric symptoms: sexual disorder (DASH‐II) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, Spearman rank correlation | ||||

|

Rojahn et al. (2010), USA Low quality |

n = 57 adults (38M, 19F) with mild, moderate, severe, or profound intellectual disability residing at a developmental centre (M age = 50.98, SD = 11.55, range 23–81) | Informant reports by care staff | Self‐injurious behaviour (BPI‐01) | Psychiatric symptoms: ASD (ASD‐DA) | + | F(1, 55) = 6.32, η 2 = .10 | Multivariate, ANOVA |

| Self‐injurious behaviour (ASD‐BPA) | NS | Not reported | Multivariate, MANOVA | ||||

| Aggressive behaviour in general (BPI‐01, ASD‐BPA) | Psychiatric symptoms: ASD (ASD‐DA) | NS | F(1, 55) = 0.34, η 2 = .06 | Multivariate, ANOVA | |||

|

Ross and Oliver (2002), UK Low quality |

n = 24 adults (15M, 9F) with severe or profound intellectual disability (M age = 39.96, SD = 10.88) | Informant reports by care staff | Physically aggressive behaviour (CBI) | Psychiatric symptoms: mood, interest, pleasure (MIPQ) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, Fisher's Exact test |

| Verbally aggressive behaviour (CBI) | Psychiatric symptoms: mood, interest, pleasure (MIPQ) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, Fisher's Exact test | |||

| Destructive behaviour (CBI) | Psychiatric symptoms: mood, interest, pleasure (MIPQ) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, Fisher's Exact test | |||

| Self‐injurious behaviour (CBI) | Psychiatric symptoms: mood, interest, pleasure (MIPQ) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, χ 2‐test | |||

|

Sappok et al. (2014), Germany High quality |

n = 203 adult patients of a psychiatric department (139M, 64F), with mild, moderate, or severe/profound intellectual disability (M age = 35.8, SD = 12.6) and living in different settings | Retrospective chart review | Physically aggressive behaviour (MOAS) | Social skills: emotional development (SAED) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, Pearson correlation |

| Psychiatric diagnosis: schizophrenia, mood disorders, neurotic disorders, personality disorders, ASD (ICD‐10 diagnosis as derived from case file) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, Pearson correlation | ||||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: dependency disorder (ICD‐10 diagnosis as derived from case file) | NS | r = .19 | Univariate, Pearson correlation | ||||

| Verbally aggressive behaviour (MOAS) | Social skills: emotional development (SAED) | + | β = 0.26, CI [0.10; 0.43] | Multivariate, regression analysis | |||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: schizophrenia (ICD‐10 diagnosis as derived from case file) | NS | r = −.19 | Univariate, Pearson correlation | ||||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: mood disorders (ICD‐10 diagnosis as derived from case file) | NS | r = .17 | Univariate, Pearson correlation | ||||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: neurotic disorders, ASD, dependency disorders (ICD‐10 diagnosis as derived from case file) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, Pearson correlation | ||||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: personality disorder (ICD‐10 diagnosis as derived from case file) | + | β = 1.05, CI [0.34; 1.76] | Multivariate, regression analysis | ||||

| Destructive behaviour (MOAS) | Social skills: emotional development (SAED) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, Pearson correlation | |||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: schizophrenia, mood disorders, neurotic disorders, personality disorders, ASD, dependency disorders (ICD‐10 diagnosis as derived from case file) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, Pearson correlation | ||||

| Self‐injurious behaviour (MOAS) | Social skills: emotional development (SAED) | − | β = −0.38, CI [−0.53; −0.23] | Multivariate, regression analysis | |||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: schizophrenia, mood disorders, neurotic disorders, personality disorders (ICD‐10 diagnosis as derived from case file) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, Pearson correlation | ||||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: dependency disorders (ICD‐10 diagnosis as derived from case file) | NS | r = .15 | Univariate, Pearson correlation | ||||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: ASD (ICD‐10 diagnosis as derived from case file) | + | β = 0.49, CI [0.17; 0.80] | Multivariate, regression analysis | ||||

| Aggressive behaviour in general (MOAS) | Social skills: emotional development (SAED) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, Pearson correlation | |||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: schizophrenia, mood disorders, neurotic disorders, personality disorders, ASD, dependency disorders (ICD‐10 diagnosis as derived from case file) | NS | Not reported | Univariate, Pearson correlation | ||||

|

Tenneij et al. (2009), the Netherlands High quality |

n = 108 adults (82M, 26F) with mild intellectual disability residing in inpatient treatment facilities for individuals with severe behavioural and emotional problems (M age = 26.4, SD = 7.5) | Informant reports by care staff | Aggressive behaviour in general (SOAS‐R) | Aggressive behaviour: self‐injurious (SOAS‐R) | + | OR = 6.2, CI [1; 38.9] | Multivariate, stepwise regression analysis |

| Self‐injurious behaviour (SOAS‐R) | Aggressive behaviour: general (SOAS‐R) | + | OR = 6.2, CI [1; 38.9] | Multivariate, stepwise regression analysis | |||

|

Thorson et al. (2008), USA Low quality |

n = 58 adults (19M, 39F) older than 21 years, with mild, moderate, severe, or profound intellectual disability residing in developmental centres | Informant reports by care staff | Self‐injurious behaviour (BPI) | Psychiatric diagnosis: any axis I disorder (DSM‐IV‐TR, DASH‐II) | NS | Not reported | Multivariate, MANOVA post hoc pairwise comparisons |

| Psychiatric diagnosis: schizophrenia (DSM‐IV‐TR, DASH‐II) | NS | Not reported | Multivariate, MANOVA post hoc pairwise comparisons | ||||

| Aggressive behaviour in general (BPI) | Psychiatric diagnosis: any axis I disorder (DSM‐IV‐TR, DASH‐II) | NS | Not reported | Multivariate, MANOVA post hoc pairwise comparisons | |||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: schizophrenia (DSM‐IV‐TR, DASH‐II) | NS | Not reported | Multivariate, MANOVA post hoc pairwise comparisons | ||||

|

Totsika et al. (2008), UK Low quality |

n = 58 adults (36M, 22F) with moderate or severe intellectual disability, living in a long‐term residential facility (M age = 45.26, SD = 12, range 23–83 years) | Informant reports by care staff | Physically aggressive behaviour (Individual Schedule) | Psychiatric diagnosis: any (Individual Schedule) | NS | OR = 2.57, CI [0.57; 11.69] | Univariate, odds ratio a |

| Self‐injurious behaviour (Individual Schedule) | Psychiatric diagnosis: any (Individual Schedule) | NS | OR = 0.42, CI [0.12; 1.38] | Univariate, odds ratio a | |||

|

Tsiouris et al. (2011), USA High quality |

n = 4,069 adults (2,445M, 1,624F) with mild, moderate, severe, or profound intellectual disability living in the community and receiving services (M age = 49.6, SD = 14.0) | Retrospective chart review + informant reports by care staff | Physically aggressive behaviour (IBR‐MOAS) | Psychiatric diagnosis: autism (DSM‐IV or DSM‐IV‐TR diagnosis derived from case file) | + | Incidence rate ratio = 1.285 | Multivariate, incidence rate ratio a |

| Psychiatric diagnosis: anxiety (DSM‐IV or DSM‐IV‐TR diagnosis derived from case file) | + | Incidence rate ratio = 1.121 | Multivariate, incidence rate ratio a | ||||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: bipolar (DSM‐IV or DSM‐IV‐TR diagnosis derived from case file) | + | Incidence rate ratio = 1.560 | Multivariate, incidence rate ratio a | ||||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: psychosis (DSM‐IV or DSM‐IV‐TR diagnosis derived from case file) | + | Incidence rate ratio = 1.477 | Multivariate, incidence rate ratio a | ||||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: impulse control disorder (DSM‐IV or DSM‐IV‐TR diagnosis derived from case file) | + | Incidence rate ratio = 1.752 | Multivariate, incidence rate ratio a | ||||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: personality (DSM‐IV or DSM‐IV‐TR diagnosis derived from case file) | + | Incidence rate ratio = 1.271 | Multivariate, incidence rate ratio a | ||||

| Psychiatric diagnosis: OCD (DSM‐IV or DSM‐IV‐TR diagnosis derived from case file) | NS | Incidence rate ratio = 1.132 | Multivariate, incidence rate ratio a | ||||