Summary

Breast implant‐associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma (BIA‐ALCL) is an uncommon T‐cell non‐Hodgkin Lymphoma (NHL) associated with breast implants. Raising awareness of the possibility of BIA‐ALCL in anyone with breast implants and new breast symptoms is crucial to early diagnosis. The tumour begins on the inner aspect of the peri‐implant capsule causing an effusion, or less commonly a tissue mass to form within the capsule, which may spread locally or to more distant sites in the body. Diagnosis is usually made by cytological, immunohistochemical and immunophenotypic evaluation of the aspirated peri‐implant fluid: pleomorphic lymphocytes are characteristically anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK)‐negative and strongly positive for CD30. BIA‐ALCL is indolent in most patients but can progress rapidly. Surgical removal of the implant with the intact surrounding capsule (total en‐bloc capsulectomy) is usually curative. Late diagnosis may require more radical surgery and systemic therapies and although these are usually successful, poor outcomes and deaths have been reported. By adopting a structured approach, as suggested in these guidelines, early diagnosis and successful treatment will minimise the need for systemic treatments, reduce morbidity and the risk of poor outcomes.

Keywords: BIA‐ALCL, reconstructive breast surgery, lymphoma, breast implants, treatment guidelines

Since the first description of the use of a silicone prosthesis for breast augmentation in 1961, 1 it is estimated that up to 35 million women worldwide have had breast implants, with a recent prevalence rate as high as 3·3% reported in the Netherlands. 2 , 3 , 4 As an implanted foreign body, breast implants are not without risks and remain one of the most researched medical devices of all time. Reoperations and local complications have traditionally been the most frequent cause for concern following reviews into the safety of silicone breast implants, reported by the United Kingdom (UK) Independent Review Group in 1998 5 and the United States Institute of Medicine in 1999. 6 However, they found no evidence of an increase in breast or other malignancies in women with implants, although a number of studies since then have identified an uncommon but unique form of lymphoma that arises in association with breast implants. This is called breast implant‐associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma (BIA‐ALCL). The first such case was reported in the literature in 1997, 7 with five additional cases over the next decade. 8 In contrast to other lymphomas involving the breast, breast cancer, or benign lesions of the breast, the parenchyma is usually not involved in BIA‐ALCL except in cases where the malignancy extends through the implant capsule into the surrounding tissue.

For many years the association of breast implants with ALCL, a subtype of T‐cell non‐Hodgkin Lymphoma (NHL), was considered a random event as the total incidence of ALCL in the breast as a primary malignancy was 0·037 per million women per year. 9 By contrast, breast cancer has an incidence of 936 per million women per year (a lifetime risk of 1 in 8), 10 , 11 a rate that is the same irrespective of whether a breast implant is present or not. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the USA and the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) in the UK issued medical device alerts (MDA) in 2011 and 2014, by which time three cases of BIA‐ALCL had been reported in the UK and 34 worldwide 12 , 13 with a cumulative total of 173 cases reported in the global review by Brody et al., in 2015. 14 Growing evidence indicated that BIA‐ALCL is a distinct lymphoid malignancy unique to the patient cohort in which it was being observed, such that the World Health Organisation added it to its classification of lymphoid neoplasms the following year as a provisional entity alongside systemic/nodal and cutaneous ALCL. 15

As of April 2020, there are 68 confirmed reports of BIA‐ALCL in the UK 13 and about 800 cases worldwide, with 33 deaths attributed to BIA‐ALCL. 4 , 16 Both saline and silicone‐filled implants are implicated. Of note, there have been no reported cases of BIA‐ALCL in patients with a breast implant history that is confirmed to only include a smooth device, suggesting that textured implants are the causative factor. 14 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 The absolute risk of developing BIA‐ALCL is small ranging broadly depending on the study conducted and geographic location, from roughly 1:354 to 1:37 000 patients with textured implants. 3 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 The figures may lack accuracy due to the various methods of reporting and dearth of knowledge of the true denominator. While causation and pathogenesis are still the subject of broad investigation, the higher rates are associated with macro‐textured surfaces (higher surface area/roughness) whether placed for reconstructive or aesthetic reasons. 18 , 19 , 20 , 24 This information should not only inform on a prospective change in practice, but also emphasises the need for a systematic approach to investigate patients who present with problems with their implants.

This UK guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of BIA‐ALCL builds further on the United States National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) 26 , 27 , 28 and UK pathology guidelines 29 to better reflect the unique differences that exist in UK practice where there is an approximate 50:50 split between implant operations in the private sector and those conducted within the National Health Service (NHS); the majority of implant breast reconstruction (86%) is performed within the NHS and virtually all cosmetic implant surgery (98%) takes place in the private sector. 30 Specialist surgery is usually undertaken by breast or plastic surgeons who should be members of one of the three Surgical Societies: the Association of Breast Surgery (ABS), the British Association of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgeons (BAPRAS) or the British Association of Aesthetic Plastic Surgeons (BAAPS).

Implant monitoring

In the UK, routine radiological surveillance to assess implant health is not recommended within the NHS or private sector. 31 Any additional breast imaging is usually symptom‐driven by patient/surgeon concern or following clinical review. In order to monitor and improve patient safety, a Breast and Cosmetic Implant Registry (BCIR) was introduced in the UK in October 2016, recording the implants that have been used for patients and the organisations and surgeons that have carried out the procedures. The registry aims to provide the data needed to detect any early safety signals in relation to an implant and provide a mechanism for managing patients in the event of an implant recall. All providers of breast implant surgery are expected to participate. 30

Referral for breast assessment

Patients with implants who develop breast symptoms may initially present to their general practitioner (GP) or the private surgeon/clinic. In the absence of private medical insurance, the cumulative cost of consultations and investigation in the independent sector can be prohibitive such that anyone with a breast symptom and a breast implant should be referred to the local NHS symptomatic breast clinic irrespective of the initial pathway for implant surgery, as long as they meet the NHS UK residency eligibility criteria. This will improve the quality of assessment, have no self‐funding implications and should reduce the risk of missed or late diagnosis.

Patients without breast symptoms but concerned about BIA‐ALCL and/or their breast implant health can be reassured by their GP or private breast surgeon/clinic and directed to the MHRA website. 13

Clinical presentation and investigation

Symptoms and signs

BIA‐ALCL presents at a median of 8–10 years following reconstructive or cosmetic breast implantation. Early occurrence has been reported and the diagnosis should therefore be considered in any cases where implants have been in situ for longer than 12 months. 14 , 17 , 28 , 32 , 33 The lymphoma develops from the luminal aspect of the peri‐implant capsule (85%), commonly precipitating the rapid development of a periprosthetic effusion, resulting in distortion to the breast including breast swelling or new‐onset breast asymmetry. While commonly only one breast is affected, rare bilateral cases have been reported. 33 , 34 Less commonly (15%) presentation is with a palpable mass, or a combination of effusion and mass. 17 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 33 More subtle presentations may occur that are difficult to identify, particularly in the presence of pre‐existing breast asymmetry (Fig 1).

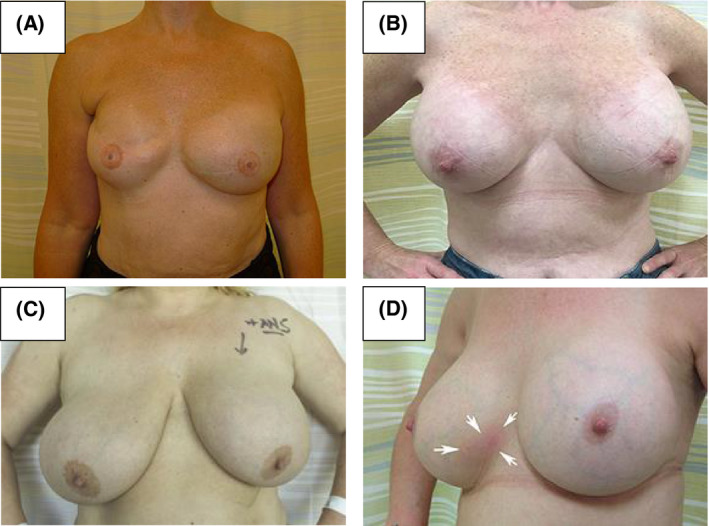

Fig 1.

Examples of clinical presentations of implant‐associated breast effusion due to breast implant‐associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma (BIA‐ALCL). (A) Effusion in a reconstructed left breast. (B) Effusion in an augmented left breast. (C) Subtle effusion in an augmented left breast, masked due to underlying physiological asymmetry, with a bigger and more redundant right breast. (D) Rash of the lower inner quadrant of the right breast preceded the appearance of a BIA‐ALCL mass at the same site.

Approximately one third of patients report pain and additional signs such as erythaema (14%), or skin lesions/ulceration (8%), 32 , 33 (Fig 1D). In a small proportion of cases, local dissemination presents with ipsilateral axillary, supraclavicular, internal mammary chain or mediastinal lymphadenopathy. In 9% of cases, systemic ‘B’ symptoms consisting of unexplained weight loss, fevers or night sweats, are observed. 33 BIA‐ALCL may occasionally be an incidental finding on routine histology after capsulectomy for capsular contraction or implant rupture. 32 , 35

There are important differentials to consider in presentations of both the ‘effusion‐only’ and ‘mass‐forming’ subtypes of BIA‐ALCL. Late seroma is a rare and usually benign complication that affects up to 0·1% of all breast implant procedures. 36 , 37 Despite the broad range of causes (silicone bleed, trauma, infection, idiopathic, haematoma, BIA‐ALCL and implant rupture), up to 10% of cases may be attributable to BIA‐ALCL. In the assessment of patients presenting with a mass‐forming lesion or lymphadenopathy, important differentials include reactions to silicone, primary breast cancer, other lymphoma subtypes, sarcoma and metastases from other primary malignancies such as melanoma; all occur at a significantly greater frequency than BIA‐ALCL. In contrast to other lymphomas involving the breast, breast cancer or benign lesions of the breast, the parenchyma is usually not involved in BIA‐ALCL except in cases where the malignancy extends through the implant capsule into the surrounding tissue. Skin lesions in isolation may represent primary cutaneous ALCL, rather than BIA‐ALCL.

Initial assessment

Investigation for a diagnosis of BIA‐ALCL should be conducted in clinical units equipped with the necessary diagnostic expertise and should follow the proposed UK guidelines diagnostic algorithm (Fig 2), based on the principle of triple assessment: clinical examination, imaging and biopsy.

Fig 2.

The UK Diagnostic algorithm for the assessment of new clinical signs in the context of previous breast implantation Adapted with permission from the NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN) for T‐Cell Lymphomas V.1.2020. 2020 National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc. All rights reserved. 28 PET CT, positron emission tomography/computed tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; HMDS, Haematological Malignancy Diagnostic Service; MDT; multidisciplinary team; IHC, immunohistochemistry; BIA‐ALCL, breast implant‐associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma.

A detailed medical history should be taken that includes the patient’s family history of cancer as this may prompt a genetics referral in accordance with the updated National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines on familial breast cancer (CG164). 38 Of note, some cases of BIA‐ALCL have been linked to Li Fraumeni Syndrome 39 and BRCA gene mutations, 3 , 40 and whether a genetic predisposition for breast cancer is similarly a risk factor for BIA‐ALCL is as yet unanswered and needs further investigation to clarify the risk. At present, patients diagnosed with BIA‐ALCL are not eligible for genetic testing under NHS commissioning guidelines unless the standard family history criteria are met. 41

Radiology in BIA‐ALCL

Imaging for BIA‐ALCL can be challenging, due to its unique biology and frequently non‐specific appearance. 35 It is important that those performing breast imaging and clinicians should consider the diagnosis of BIA‐ALCL in the appropriate setting.

Ultrasound (US)

US is the initial investigation of choice to assess pain, swelling or a mass related to a breast implant. 28 , 42 It has a sensitivity of over 80% for detecting a peri‐implant collection, with a specificity of less than 50% in elucidating the underlying cause. 35 US should include assessment for axillary lymphadenopathy and evaluation of the contralateral implant, where present.

US evaluation is operator dependent. The image should be optimised to evaluate the implant membrane, capsule and material contents along with the adjacent breast parenchyma. The entire implant should be integrated in the field of view. A high frequency (7–14 MHz) linear array probe should be used to delineate the membrane and capsule. 43

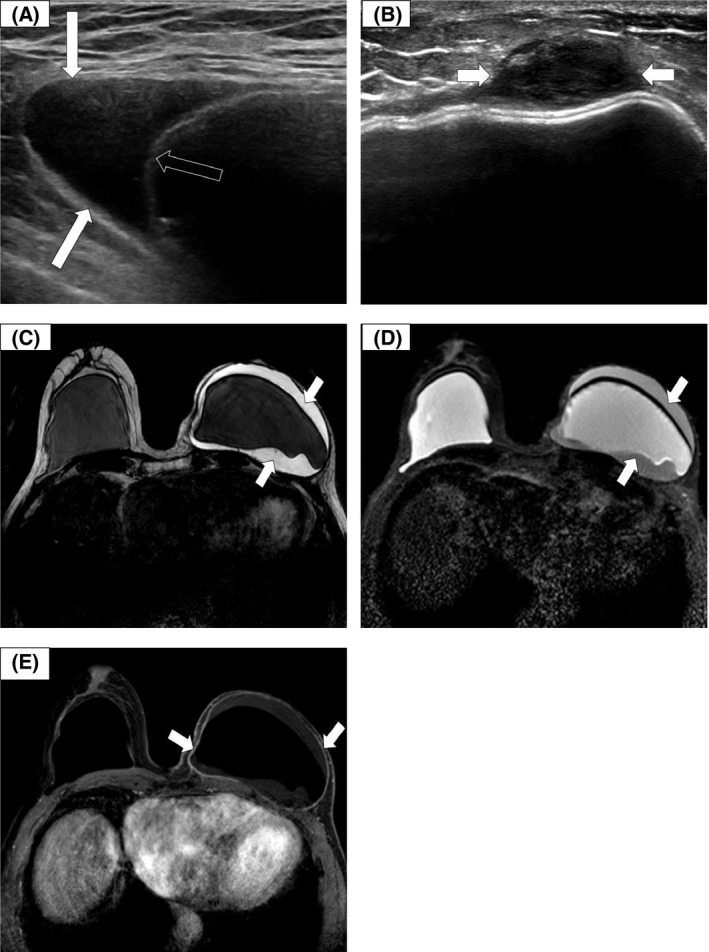

Knowledge of implant type greatly assists assessment and will avoid potential misinterpretation. The appearance of dual lumen implants can mimic peri‐implant effusions and intracapsular leaks. A small volume of fluid (< 10 ml) around an implant is often seen as a normal incidental finding and in an asymptomatic patient does not warrant further investigation. 28 , 43 , 44 . Effusions associated with BIA‐ALCL are usually homogeneous (Fig 3A) with inflammatory features in the periprosthetic breast tissue and in some cases a thickened irregular capsule. Masses can also be observed and may be solid or mixed cystic/solid and are usually ovoid (Fig 3B).

Fig 3.

Ultrasound (US) and magnetic resonance (MR) imaging in breast implant‐associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma (BIA‐ALCL). (A) Transverse US showing a peri‐implant effusion (arrows) and implant membrane (open arrow). (B) Transverse US showing a pericapsular ovoid solid mass (arrows). (C) MR imaging: axial T2‐weighted image showing an effusion around an intact left breast silicone implant. (D) MR imaging: axial silicone‐selective image showing a silicone signal between the intact implant shell and the capsule in keeping with silicone shedding/gel bleed (arrows). (E) MR imaging: axial T1‐weighted gadolinium‐enhanced fat saturation image showing LEFT effusion and capsular enhancement (arrows), with no effusion or capsular enhancement on the unaffected RIGHT side.

Mammography

If the patient is over 40 years of age, mammography should also be undertaken. Mammography has a low sensitivity and specificity for BIA‐ALCL, but it may be used to assess for any potential mimics/masses and other diagnoses including in situ and invasive primary breast malignancy. In cases of BIA‐ALCL, the capsule may be thickened and the membrane contour may be disrupted. 35

Magnetic Resonance (MR) imaging

In cases of diagnostic uncertainty or inconclusive US, MR imaging should be undertaken to assess the implant, effusion, capsule and for any potential mass and local lymphadenopathy. When the diagnosis has been established from the initial US fine‐needle aspiration (FNA) or core biopsy, MR imaging should be performed to assess disease extent and aid surgical planning. Non‐contrast sequences (T2‐weighted and silicone‐selective) may show implant membrane disruption (rupture), pericapsular effusions and signs of gel bleed (Fig 3C, D). In addition, dynamic contrast‐enhanced (DCE) sequences should be utilised to assess for capsular enhancement (Fig 3E) and masses which may not have been detected on US. 45

FDG PET/CT

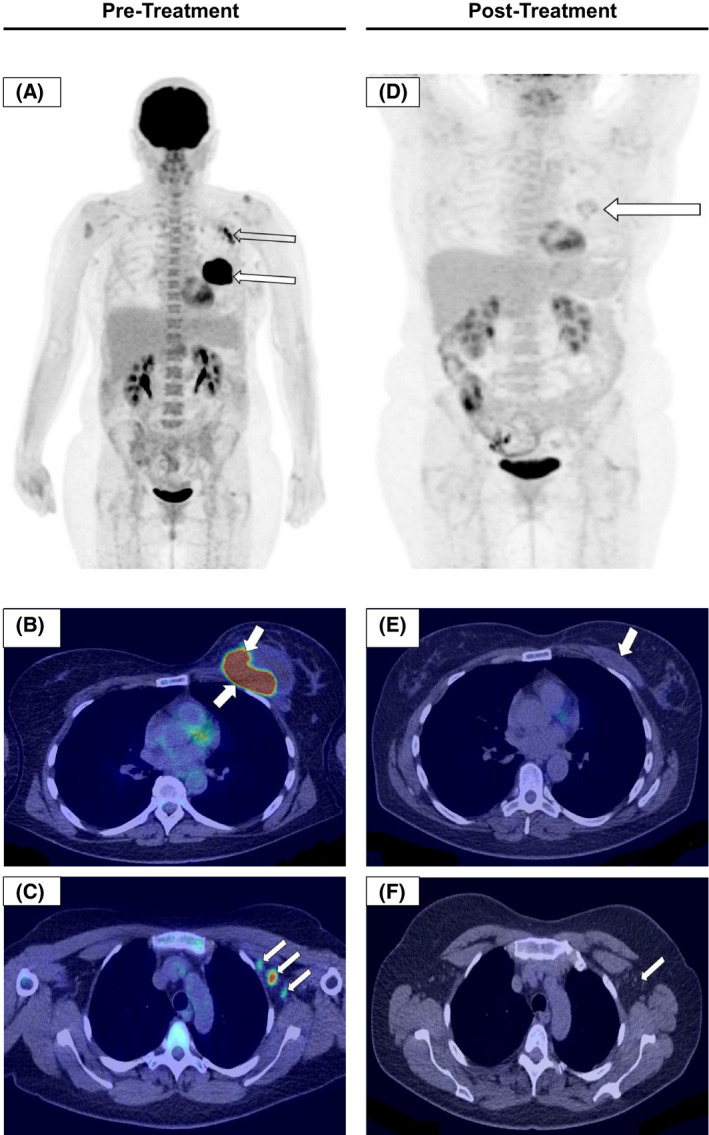

2‐[Fluorine‐18]fluoro‐2‐deoxy‐D‐glucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography (FDG PET/CT) plays an important role in the oncological staging of the majority of subtypes of lymphoma, although BIA‐ALCL was recognised subsequent to the most recent Lugano Classification Guidelines and so the utility of FDG PET/CT in this context has yet to be formally validated. 46 Low cell density peri‐implant effusions may not be FDG‐avid and inflammation/post‐intervention sequalae may lead to non‐malignant FDG uptake hampering interpretation. Nonetheless, expert groups recommend that FDG PET/CT should be undertaken for pre‐operative staging of local extent and distant disease (Fig 4A–C). 26 Carrying out PET/CT prior to the surgical intervention is necessary because post‐surgical inflammation in the chest wall, surrounding breast and regional nodes, may at times persist for a few months and hinder the identification of the uncommon patients that have extracapsular or nodal involvement. PET/CT is also required for response assessment (pre or post‐surgery), where systemic therapy has been administered (Fig 4D–F). 26 , 28 , 35 , 44

Fig 4.

2‐[Fluorine‐18]fluoro‐2‐deoxy‐D‐glucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography (FDG PET/CT) imaging in breast implant‐associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma (BIA‐ALCL). FDG PET/CT pre‐treatment (A–C), and post‐treatment images (D–F) from the same patient six weeks after the last cycle of chemotherapy. Total en‐bloc capsulectomy with excision of the BIA‐ALCL mass was followed by CHOP chemotherapy. The patient went on to have an autologous stem cell transplant and remains disease‐free one year later. (A) Coronal maximum intensity projection (MIP) PET image; there is an intensely avid mass around the left implant (arrow) and avid left axillary nodes (open arrow). (B) Axial fused PET/CT image showing an intensely avid mass in the left breast. (C) Axial fused PET/CT image demonstrating avid left axillary nodes which were confirmed to be involved on biopsy. (D) Post‐treatment coronal MIP PET image. There is no uptake of a malignant configuration; the minimal uptake in the surgical bed is in keeping with minor residual inflammation (arrow). (E) Post‐treatment axial fused PET/CT showing minimal seroma in the surgical bed (arrow). (F) Post‐treatment axial fused PET/CT demonstrating that the axillary nodes have resolved (arrow).

Evaluation of peri‐implant effusion and/or mass lesions

Where an effusion is present, the key to diagnosis of BIA‐ALCL is FNA of the entire volume of peri‐implant fluid for initial cytology and then secondary assessment where indicated (please see the subsequent section on preparation for pathology), and/or 14‐gauge core biopsy of any associated capsular mass or pathological node as per the diagnostic algorithm presented in Fig 2. If capsular nodular lesions detected on imaging are not amenable to core biopsy, open surgical excision or repeat interval imaging should be considered.

The chance of an accurate diagnosis is greatest on the initial peri‐implant aspirate, and small‐volume aspiration or subsequent repeat aspiration(s) are associated with greater false‐negative cytology, due to a dilution effect. 29 The main sample is sent as three separate specimens with these suggested volumes: Haematological Malignancy Diagnostic Service (HMDS), 10 cc in two purple‐top EDTA tubes; microbiology, 5–10 cc in a white‐capped sterile universal container; cytology should receive the entire remaining volume (at least 50 cc but can be over 500 cc), sent in multiple standard universal containers.

Local pathways must be established to ensure the correct handling and timely assessment of specimens and the request forms must clearly state concerns for a diagnosis of BIA‐ALCL. It is prudent to alert the lab to prevent a delay in analysis. The cytology department should be advised that the entire effusion sample is to be analysed.

Primary histopathological assessment

We recommend that the evaluation of peri‐implant associated effusions and tissue masses is conducted as a two‐stage process where the primary assessment is morphological. Tumour cells may be found in both the fluid and the capsule mass (where both are present) but may be seen in only one or the other. 14 , 24 Cells within fluid samples are collected by centrifugation to produce cytospins which are stained according to local preferences (Fig 5). The cells in the remaining fluid should also be collected by centrifugation to improve the diagnostic yield. The cells should be fixed with liquid preservative, subject to centrifugation and processed to create cytoblocks for immunohistochemistry.

Fig 5.

Cytology: morphology of atypical lymphoid cells representative of breast implant‐associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma (BIA‐ALCL). (A) Haematoxylin and eosin (H&E). (B) Pap stains. Arrows indicate atypical cells that would trigger follow‐up investigations. (C) Histology demonstrating atypical lymphoid cells suspicious of ALCL on the luminal side of the breast implant capsule detected by H&E and (D) CD30 stains.

The characteristic morphological abnormalities seen on standard cytology are regarded as a gold standard pre‐requisite for a diagnosis of BIA‐ALCL (Fig 5A, B). 29 , 47 This primary assessment should be conducted first; acellular samples and those composed entirely of bland inflammatory cells can be reported as negative and do not require further analysis. 29 While the vast majority of peri‐implant effusions are not related to ALCL, patients should be made aware of the limitations of diagnostic testing and the possibility of false negative results, given cytologic assessment to detect BIA‐ALCL has a sensitivity of about 78%. 35 If clinical or radiological suspicions remain after negative cytology, multidisciplinary team (MDT) discussion and referral to a tertiary centre are recommended. Secondary assessment of cytospins/cytoblocks may also be conducted as described below. In the absence of suspicion, patients should be followed up at three months to ensure that the swelling does not recur. Patients should be advised to report any symptoms that return.

Secondary assessment

All diagnoses of BIA‐ALCL should be reviewed by a haematopathologist within a specialist integrated HMDS, as per NICE guidelines. 48 Where BIA‐ALCL is suspected morphologically, further analysis is performed by immunohistochemistry using markers to confirm the haematopoietic origin of the cells: CD45; T‐cell markers: for example, CD2, CD3, CD4, CD5, CD7 and CD8; cytotoxic markers: for example, TIA1 and Granzyme B; other markers: anaplastic lymphoma kinase (Alk‐1) which by definition should be negative, CD30 which should be positive; and a B‐cell panel: for example, CD20, CD79a, PAX5 and EBER to exclude the rare cases of fibrin‐associated diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma (DLBCL) as these can display aberrant expression of CD30 and other T‐cell markers. 49 Other markers such as CD68, CD138, BCL‐2, IRF4, Ki67 and pan‐keratin may also be useful. It can be difficult to define an aberrant/neoplastic T‐cell phenotype as the tumour cells often lack expression of T‐cell antigens, and CD30 expression alone is not a defining feature as it is also present on normal activated T‐, B‐ and natural killer cells. 29 , 47 , 50 For this reason, screening of effusion fluid for CD30‐positive cells by flow cytometry in the absence of morphological abnormalities on cytology may lead to difficulties in interpretation and a false‐positive diagnosis. 29 The clonality of T cells should be confirmed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for T‐cell receptor (TR) gene rearrangements. 51 , 52 FISH can be used to assess the absence of the ALK translocation and to exclude other translocations seen in a proportion of systemic ALCL but not BIA‐ALCL such as those involving IRF4/DUSP22 and TP63. While not part of the diagnostic algorithm, numerous recurrent mutations have been detected in BIA‐ALCL. The most frequently reported are mutations that involve the JAK‐STAT pathway genes such as JAK1 and STAT3 mutations and epigenetic modifiers, for example DNMT3A. 53 , 54 , 55 , 56 , 57

Processing samples for research purposes

Hypotheses proposed regarding the pathogenesis of BIA‐ALCL include chronic inflammation driven by a bacterial biofilm, microparticles shed from the implant shell, repetitive trauma/friction between the implant shell and the capsule, carcinogenic toxins leaching from the implant or genetic predisposition. 39 , 40 , 53 , 58 , 59 , 60 , 61 , 62 , 63 , 64 Details of ongoing active UK research studies can be found here: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about‐cancer/find‐a‐clinical‐trial/a‐study‐find‐more‐about‐causes‐breast‐implant‐associated‐anaplastic‐large‐cell‐lymphoma‐bia‐alcl, and clinicians are encouraged to contact the investigators for further details. It is hoped that in the future, a centralised biobank of samples for research purposes can be developed.

Management of an indeterminate breast assessment: reactive effusions

Approximately 90% of chronic delayed seromas are clear or haemo‐serous, have no atypical cells and are not associated with malignancy. However, as a paucity of neoplastic cells can make diagnosis difficult (hence, the requirement to assess the whole seroma by cytology — see above), clinicians must always exercise caution when faced with a reactive seroma report in case of a false‐negative result. If reasonable suspicion persists, consider the following options: referral to a tertiary centre with expertise in the diagnosis and management of BIA‐ALCL, MDT discussion, repeat assessment with US and further aspiration for cytology, additional imaging with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), diagnostic total en‐bloc capsulectomy and explantation, or close monitoring. The pros and cons of each approach need careful case‐by‐case consideration, with shared decision‐making, taking into account the degree of concern, differential diagnosis and the morbidity from interventions such as total en‐bloc capsulectomy. This includes pneumothorax in up to 4% of cases, a possibility of chronic pain and significant cosmetic sequelae.

Management of confirmed cases

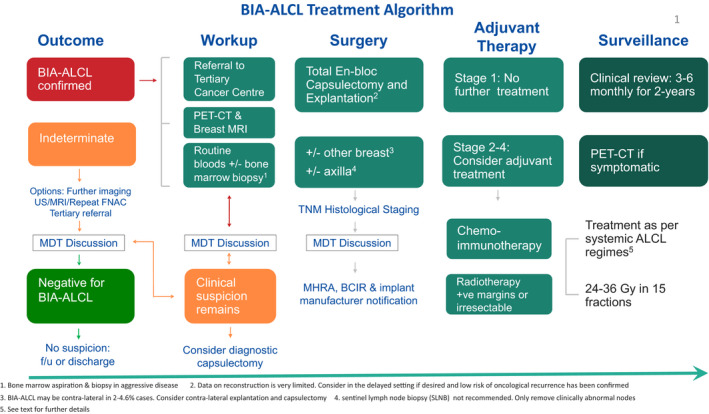

The optimal approach to patient treatment is based on the revised National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines and evolving experience from treated cases. 28 , 32 All confirmed BIA‐ALCL patients must be referred to a tertiary centre for their further management. A proposed treatment algorithm is shown in Fig 6.

Fig 6.

The UK Treatment algorithm Adapted with permission from the NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN) for T‐Cell Lymphomas V.1.2020. 2020 National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc. All rights reserved. 28 US, ultrasound; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; FNAC, fine‐needle aspiration cytology; MDT, multidisciplinary team; BIA‐ALCL, breast implant‐associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma; PET‐CT, positron emission tomography/computed tomography; TNM, tumour‐node‐metastasis; MHRA, Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency; BCIR, Breast and Cosmetic Implant Registry.

Cases must always be recorded in the BCIR (https://clinicalaudit.hscic.gov.uk) and reported to the MHRA using the yellow‐card scheme for a medical device adverse incident (https://yellowcard.mhra.gov.uk/). After central registration of the case, clinicians will be contacted for further information. They must respond promptly and maintain up‐to‐date contact information for this process. The implant manufacturer has a regulatory duty to report device failures or adverse incidents to the regulatory authority. They should be contacted to collect and analyse the implant after removal and provide any findings in their Vigilance report.

Pre‐operative investigations

Discussion of cases of BIA‐ALCL must occur in the MDT meeting prior to any intervention. We advocate this due to the crucial requirement for shared management of these patients between haemato‐oncology and breast surgery, therefore early collaboration is likely to improve patient outcomes. All imaging results including PET/CT and breast MRI should be reviewed. Routine pre‐operative blood tests include: full blood count (FBC), urea and electrolytes (U&E), Liver function tests (LFTs), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and virology. Bone marrow aspiration and trephine to assess for the presence of marrow disease is recommended prior to surgery in all cases of BIA‐ALCL where the disease is aggressive, defined as local‐regional or distant lymph node involvement or unexplained cytopenia. 28 , 34

Explantation with total en‐bloc capsulectomy

Surgery is the recommended primary treatment for all patients with BIA‐ALCL, except the minority who present with locally advanced or distant metastatic disease who may benefit from initial systemic therapy. Surgery should be performed by an experienced member of the oncoplastic breast or plastic surgery team, familiar with performing implant‐based surgery and with additional expertise in capsulectomy and tumour extirpation.

Early BIA‐ALCL is confined to the peri‐implant effusion or contained within the capsule (Stages 1 and 2A). Total en‐bloc surgical excision plays a pivotal role in reducing stage progression, future recurrence and to improve overall survival (OS). 34 With a total en‐bloc capsulectomy the specimen is removed as one complete piece comprising the entire un‐breached capsule and any associated mass; the implant and associated effusion are fully retained within the explanted specimen (Fig 7). This technique is distinctly different to the piecemeal or partial capsulectomy approach sometimes used when dealing with capsular contraction. Where inadvertent dissection into a thin capsule results in effusion fluid contaminating the operative field, the cavity should be thoroughly irrigated before wound closure. One case of local recurrence in the UK series was thought to be related to the seeding of effusion fluid from the drain exit site. 17

Fig 7.

Appearance of a total en‐bloc capsulectomy specimen. (A) Specimen with associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) mass and an overlying ellipse of skin. (B) Contralateral (unaffected) implant also removed en‐bloc. (C) After en‐bloc capsulectomy the capsules have been orientated with a 2‐0 silk suture (short superior, long lateral, medium medial and double loop anterior) after removing the implant via an inferior clam shell capsulotomy. The peri‐implant effusion fluid has been collected for cytology and HMDS. (D) Florid appearance of ALCL throughout the capsule. (E) Localised nodules of ALCL in the capsule. (F) Inner capsule which was also positive for breast implant‐associated (BIA)‐ALCL. (G, H) Peri‐implant effusion fluid. (I) Appearance after opening the specimen via inferior capsulotomy demonstrating a yellow raised capsular ).

If there is an axillary mass/enlarged axillary nodes, attempts should always be made to characterise these pre‐operatively. However, it should not be assumed that enlarged axillary lymph nodes seen on the staging PET scan are definitive evidence of lymphomatous involvement as these can be reactive or enlarged due to silicone lymphadenopathy. 65 , 66 While there is no role for sentinel node biopsy, histological confirmation with excision of enlarged nodes at the time of surgery should be sought. 32 , 67

The capsule of sub‐pectoral implants may be densely adherent or inseparable from the rib surface/intercostal muscles such that pneumothorax is a recognised risk. The operation note must record if the procedure was completed en‐bloc, or if any areas of capsule could not be removed for technical reasons. A simultaneous contralateral explantation and total capsulectomy should be strongly considered, as incidental BIA‐ALCL may be found in 2–4·6% of cases. 33 , 34 Data on immediate reconstruction are very limited and where this is requested, it is preferable to consider it in the delayed setting after a period of observation. 68 A repeat PET/CT or MRI at least six months after surgery should be considered before any decision is made. Options that might be explored include autologous flaps, fat grafting and even reconstruction with implants although in this latter case, smooth implants should be the predominant option.

Processing the specimen post‐explant

The contained peri‐implant effusion, which commonly comprises turbid fluid, should be drained from the specimen by making a 2‐mm cut into the capsule on the inferior pole and the fluid sent for cytology (Fig 7G, H). The capsule should be opened as a full inferior capsulotomy that extends from the 9 o’clock to 6 o’clock to 3 o’clock position (clam shell capsulotomy) (Fig 7C, D, E, I).

All removed implants, intact or ruptured, must be treated as a biohazard, appropriately labelled and stored as such, until collected by the manufacturer to fulfil their Vigilance obligations. If there has been a catastrophic rupture and the filler material is not recoverable, the silicone shell of the implant should still be retained. Patients should be warned that this is a regulatory requirement and that it is not appropriate, therefore, for the patient to take them home. We recommend that photographs are taken of the implant after explantation, at the end of the procedure, whether intact or ruptured. This should include a close‐up of the posterior ‘patch’ to show the manufacturer’s name, implant style and lot number, which must be recorded in the operation note. These images will act as both a clinical and medico‐legal record and will facilitate identification of the implant.

The capsule should be inspected to identify areas of concern to highlight to the pathologist. The capsule must be formally orientated by placing external sutures, for example, short silk to superior, long silk to lateral, medium silk to medial and double loop silk to anterior (Fig 7C). If a double capsule is present, the inner layer should be peeled off the implant and sent separately as BIA‐ALCL may be present separately in this layer (Fig 7F). Primary analysis of the capsule is morphological and is usually carried out by the breast pathology team, working closely with haematopathology for secondary molecular assessment as described above (Fig 5C,D). As many capsules look macroscopically normal, or are affected by areas of silicone impregnation, it is essential that multiple representative sections are taken to increase the detection of small areas of tumour cells within the capsule or on the luminal surface, as these are challenging to detect. 69 , 70 Miranda et al. reported that no mass could be identified on macroscopic examination of the capsule in 42 of 56 (75%) cases in their report of 60 patients with BIA‐ALCL. 32 In cases that despite exhaustive microscopic assessment fail to reveal any abnormal cells, the disease is categorised as effusion‐limited (stage 1A). 29

Management of BIA‐ALCL found incidentally on capsulectomy specimens

Capsulectomy is commonly performed at the same time as implant exchange or explantation for grade 3–4 capsular contracture, and it is recommended that capsules are removed in one piece wherever possible and submitted for routine histological analysis. Specimens should be orientated to maximise the value of histopathology. In the rare scenario where BIA‐ALCL is found incidentally in this manner 14 , 17 subsequent patient management should follow the diagnostic and treatment algorithms provided in this document.

Staging

The American Joint Committee on the cancer tumour‐node‐metastasis (TNM) staging system for solid tumours should be used in preference to the Lugano modification of the Ann‐Arbour classification traditionally used for lymphoid neoplasms, as proposed by Clemens et al. 34 (Table I). This not only better reflects the in situ or local infiltrative patterns associated with the disease but also allows better prognostic classification. Patients with disease limited to the effusion or confined to the capsule have a good/excellent prognosis with up to 93% reported to achieve complete remission at a median follow‐up of two years. 32 Presentation with a tumour mass that extends beyond the capsule, with lymph node or more distant involvement reflects aggressive disease and is associated with lower disease‐free (DFS) or overall survival (OS). 17 , 32 , 34 , 52

Table I.

Proposed TNM staging system for BIA‐ALCL, adapted from Clemens et al. 34

| Description of lymphoma cells | Stage | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| T = Tumour extent (penetration of capsule) | |||

| T1 | Only in the effusion or on luminal side of the capsule | 1A | T1N0M0 |

| T2 | Superficial infiltration of the luminal side of the capsule | 1B | T2N0M0 |

| T3 | Cell aggregates/sheets penetrate the capsule | 1C | T3N0M0 |

| T4 | Cells infiltrate beyond the capsule | 2A | T4N0M0 |

| N = Node extent | |||

| N0 | No lymph node involvement | ||

| N1 | One local/regional node involved | 2B | T1‐3N1M0 |

| N2 | More than one local/regional node involved | 3 | T4N1‐2M0 |

| M = Metastatic disease | |||

| M0 | No involvement of distant sites | ||

| M1 | Disease present at distant sites | 4 | T1‐4N0‐2M1 |

TNM, tumour‐node‐metastasis; BIA‐ALCL, Breast Implant‐Associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma.

Systemic treatment

The vast majority of patients who present with effusion‐only BIA‐ALCL will not require systemic or adjuvant therapy which should be confirmed after the disease stage has been defined and the case discussed at the haematology and breast MDT meetings.

Indications for chemotherapy, monoclonal antibody and/or autologous stem cell transplant

Mass‐forming disease, lymph node involvement or distant disease may require systemic treatment, and this is advocated for stage 2–4 disease. An individualised approach to systemic treatment is recommended for more advanced cases. In the series published by Clemens et al. one third of patients that received systemic chemotherapy experienced disease progression due to either a lack of appropriate local surgical control, or disease resistance to the regimen used. 34

Due to the rarity of advanced BIA‐ALCL, optimal chemotherapeutic choice is extrapolated from studies investigating systemic ALK‐negative ALCL. National guidelines for the treatment of systemic disease are published by the British Committee for Standards in Haematology (BCSH). 71 At present, CHOP (cyclophosphamide, hydroxydaunorubicin (doxorubicin), (onco)vincristine and prednisolone) chemotherapy is most frequently used for the upfront treatment of ALCL based on experience with this regimen from high‐grade B‐cell lymphoma, despite poorer outcomes in the T‐cell lymphoma setting. 72 There is conflicting evidence as to whether the addition of etoposide leads to improved outcomes. 73 , 74 , 75 , 76 , 77

Recently, ECHELON‐2, a large phase III double‐blinded randomised trial, demonstrated an improved median progression‐free survival (PFS) with BV‐CHP [brentuximab vedotin (BV), an anti‐CD30 antibody drug conjugate, given in place of vincristine] compared to standard CHOP, with PFS improving to 48·2 from 20·8 months (HR 0·71, 95% CI 0·54–0·93, P = 0·0110) with no significant differences in toxicity. 78 An OS benefit was also seen in favour of BV‐CHP (HR 0·66, 95% CI 0·46–0·95). This improvement was most significant in the ALCL subgroup. Following FDA approval of this combination for use in patients with untreated CD30‐positive T‐cell lymphomas and European Medicines Agency (EMA) approval for untreated systemic ALCL, NICE approved its use in the NHS as per EMA indication in July 2020.

Single‐agent BV is currently licensed and funded in the UK for relapsed/refractory ALCL based on data from a phase 2 study showing a favourable response rate of 86% with a complete response of 57%. 79 It is likely to be used less frequently in the refractory setting as its use as part of the upfront combination increases. There is some evidence that retreatment can lead to clinical responses, particularly if a long remission is achieved initially. 80 Currently, in the UK, patients not refractory to BV‐CHP are eligible for retreatment with BV at relapse. There are two case reports of patients achieving long‐term remission following adjunct treatment with BV as a single agent following surgery for BIA‐ALCL due to associated lymphadenopathy, although neither case had histological confirmation of nodal spread of disease. 81 , 82 A further report details a patient with BIA‐ALCL who progressed whilst having CHOP chemotherapy but responded to single‐agent BV, allowing subsequent bilateral total capsulectomy and implant removal. 17 The prognosis for relapsed or refractory ALK‐negative ALCL, is poor and where possible, treatment within a clinical trial should be considered. If a patient has already had BV or is intolerant, standard platinum‐based salvage regimens such as GDP (gemcitabine, dexamethasone, prednisolone) are alternatives in the relapse setting. 71

The role of autologous stem cell transplantation as consolidation in first remission of advanced stage (stage 3 or 4) ALCL is controversial with poor quality and conflicting evidence. 83 , 84 , 85 Given the poor outcomes generally seen following relapse of T‐cell lymphoma, allogeneic or autologous stem cell transplantation of appropriate patients as consolidation following salvage treatment should be considered on a case‐by‐case basis for BIA‐ALCL.

Indications for radiation therapy

Adjuvant chest wall radiotherapy is not routinely recommended after total capsulectomy for histologically confirmed completely excised T1 and T2 tumours. It should be considered when complete excision has not been possible, if surgical margins are positive despite total capsulectomy or where there is chest wall invasion. It is unknown what the optimal radiotherapy dose should be, but doses similar to that given to patients with other high‐grade lymphomas (24–36 Gy) have been proposed by the NCCN guidelines. 28

Ongoing surveillance

We advocate joint patient follow‐up between the surgical and haemato‐oncology teams every 3–6 months, for a minimum of two years and then as indicated. While clinical assessment is required, there is a lack of evidence to support routine imaging surveillance of BIA‐ALCL whether limited or advanced stage. 86 , 87 This is analogous to the clinical principles that guide surveillance in other NHL subtypes, that routine imaging does not improve patient outcomes. 88 , 89 , 90 Our recommendation takes into consideration evidence from a range of lymphoma subtypes, the American Society of Hematology Choosing Wisely Campaign 91 and surveillance guidance provided by the NICE guidelines on NHLs. 48 Patients who become symptomatic should be re‐referred to the tertiary centre if there is a concern for disease recurrence, to enable prompt investigation.

Conclusions

It is essential that we continue to promote widespread education of BIA‐ALCL amongst healthcare workers in the UK. Patients who receive implants whether for cosmetic or reconstructive purposes must always be advised of the risk of developing BIA‐ALCL and how this relates to implant surface type. They should always report symptoms such as delayed onset breast swelling or a mass to their GP and/or surgeon. There are no recommended changes to the routine medical care in asymptomatic patients with implants. Clinicians faced with anyone who has breast symptoms and a breast implant must consider the possibility of BIA‐ALCL and should follow these diagnostic guidelines. The management of BIA‐ALCL should be performed in a tertiary centre with multidisciplinary input.

Ongoing international surveillance and research will inform future recommendations for diagnosis and treatment. BIA‐ALCL is associated with excellent outcomes for the majority of patients; with early recognition and increased detection there is greater opportunity for successful surgery with curative intent and an improved long‐term prognosis.

Author contributions

Writing, review & editing, all authors; approval of the final manuscript, all authors.

Conflicts of interest

SDT receives research funding from Allergan. DE‐S receives funding in the form of speaker’s fees and conference costs from Takeda.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all members of the MHRA Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgery Expert Advisory Group (PRASEAG) for their comments on the manuscript. We are grateful to Leeds Cares (Registered Charity number 1170369) for supporting the Open Access publication costs of this UK Guideline.

BJH acknowledges the co‐publication in EJSO.

References

- 1. Cronin TD, Greenberg RL. Our experiences with the silastic gel breast prosthesis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1970;46(1):1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Food and Drug Administration . FDA update on the safety of silicone gel‐filled breast implants 2011 [cited 2020 April]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/80685/download

- 3. de Boer M, van Leeuwen FE, Hauptmann M, Overbeek LIH, de Boer JP, Hijmering NJ, et al. Breast implants and the risk of anaplastic large‐cell lymphoma in the breast. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(3):335–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Food and Drug Administration . Oral contribution from the European Taskforce on Breast Implant Associated‐ALCL for FDA Hearing on Breast Implants 2019. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/793015/TF_Oral_Comunication_FDA_Hearing_POST_TC_21_March.pdf

- 5. Independent Review Group . Silicone Gel Breast Implants: The Report of the Independent Review Group Cambridge. England: Jill Rogers Associates; 1998. Available from: https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20110504132647/http://www.mhra.gov.uk/Safetyinformation/Generalsafetyinformationandadvice/Product‐specificinformationandadvice/Product‐specificinformationandadvice‐A‐F/Breastimplants/Siliconegelbreastimplants/IndependentReviewGroup‐siliconegelbreastimplants/index.htm

- 6. Bondurant S. Safety of Silicone Breast Implants In: Bondurant S, Ernster V, Herdman R, editors. Safety of silicone breast implants. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Keech JA Jr. Anaplastic T‐cell lymphoma in proximity to a saline‐filled breast implant. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997;100(2):554–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Newman MK, Zemmel NJ, Bandak AZ, Kaplan BJ. Primary breast lymphoma in a patient with silicone breast implants: a case report and review of the literature. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2008;61(7):822–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Thomas A, Link BK, Altekruse S, Romitti PA, Schroeder MC. Primary Breast Lymphoma in the United States: 1975‐2013. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017;109(6):1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Howlader NNA, Krapcho M, Miller D, Brest A, Yu M, Ruhl J, et al.SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975‐2016, National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD, 2019. Available from: https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2016/

- 11. Feuer EJ, Wun LM, Boring CC, Flanders WD, Timmel MJ, Tong T. The lifetime risk of developing breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85(11):892–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. U.S. Food and Drug Administration . Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma (ALCL) in women with breast implants: Preliminary FDA Findings and Analyses; 2011. Available from: http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/ProductsandMedicalProcedures/ImplantsandProsthetics/BreastImplants/ucm239996.htm

- 13. Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency . Breast implants and Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma (ALCL). Information for clinicians and patients. 2017. [updated May 2020]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/breast‐implants‐and‐anaplastic‐large‐cell‐lymphoma‐alcl#history

- 14. Brody G, Deapen D, Taylor C, Pinter‐Brown L, House‐Lightner SR, Andersen J, et al. Anaplastic large cell lymphoma occurring in women with breast implants: analysis of 173 cases. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;135(3):695–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Pileri SA, Harris NL, Stein H, Siebert R, et al. The 2016 revision of the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms. Blood. 2016;127(20):2375–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Food and Drug Administration . Medical Device Reports of Breast Implant‐Associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma 2019. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/medical‐devices/breast‐implants/medical‐device‐reports‐breast‐implant‐associated‐anaplastic‐large‐cell‐lymphoma

- 17. Johnson L, O'Donoghue JM, McLean N, Turton P, Khan AA, Turner SD, et al. Breast implant associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma: the UK experience. Recommendations on its management and implications for informed consent. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2017;43(8):1393–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Doren EL, Miranda RN, Selber JC, Garvey PB, Liu J, Medeiros LJ, et al. U.S. Epidemiology of breast implant‐associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;139(5):1042–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Leberfinger AN, Behar BJ, Williams NC, Rakszawski KL, Potochny JD, Mackay DR, et al. Breast implant‐associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma: a systematic review. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(12):1161–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Loch‐Wilkinson A, Beath KJ, Knight RJW, Wessels WLF, Magnusson M, Papadopoulos T, et al. Breast implant‐associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma in Australia and New Zealand: high‐surface‐area textured implants are associated with increased risk. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;140(4):645–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Srinivasa DR, Miranda RN, Kaura A, Francis AM, Campanale A, Boldrini R, et al. Global adverse event reports of breast implant‐associated ALCL: an International Review of 40 Government Authority Databases. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;139(5):1029–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ghione P, Cordeiro PG, Ni A, Hu Q, Ganesan N, Galasso N, et al. Risk of breast implant‐associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma (BIA‐ALCL) in a cohort of 3,546 women prospectively followed after receiving textured breast implants. J. Clin. Oncol.. 2019;37(15_suppl):1565. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cordeiro PG, Ghione P, Ni A, Hu Q, Ganesan N, Galasso N, et al. Risk of breast implant associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma (BIA‐ALCL) in a cohort of 3546 women prospectively followed long term after reconstruction with textured breast implants. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2020;73(5):841–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Loch‐Wilkinson A, Beath KJ, Magnusson MR, Cooter R, Shaw K, French J, et al. Breast implant‐associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma in Australia: a longitudinal study of implant and other related risk factors. Aesthet Surg J. 2019;40(8):838–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mercer NSG. Editorial on the article "Risk of breast implant associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma in a cohort of 3546 women prospectively followed long term after reconstruction with macro‐textured breast implants. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2020;73(5):847–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. National Comprehensive Cancer Network . NCCN Guidelines For Treatment of Cancer by Site 2016 [updated 2019]. Available from: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx#site

- 27. Clemens MW, Horwitz SM. NCCN Consensus Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Breast Implant‐Associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma. Aesthet Surg J. 2017;37(3):285–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Clemens MW, Jacobsen ED, Horwitz SM. NCCN Consensus Guidelines on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Breast Implant‐Associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma (BIA‐ALCL). Aesthetic Surg J. 2019;39(Suppl_1):S3–S13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jones JL, Hanby AM, Wells C, Calaminici M, Johnson L, Turton P, et al. Breast implant‐associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma (BIA‐ALCL): an overview of presentation and pathogenesis and guidelines for pathological diagnosis and management. Histopathology. 2019;75(6):787–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Clinical Audit and Registries Management Service NHS Digital . Breast and Cosmetic Implant Registry: England July 2018 ‐ July 2019, managment information; 2019. Available from: https://files.digital.nhs.uk/62/8C3560/BCIR_Report_2019.pdf

- 31. Lowes S, MacNeill F, Martin L, O'Donoghue JM, Pennick MO, Redman A, et al. Breast imaging for aesthetic surgery: British Society of Breast Radiology (BSBR), Association of Breast Surgery Great Britain & Ireland (ABS), British Association of Plastic Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgeons (BAPRAS). J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2018;71(11):1521–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Miranda RN, Aladily TN, Prince HM, Kanagal‐Shamanna R, de Jong D, Fayad LE, et al. Breast implant‐associated anaplastic large‐cell lymphoma: long‐term follow‐up of 60 patients. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(2):114–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. McCarthy CM, Loyo‐Berrios N, Qureshi AA, Mullen E, Gordillo G, Pusic AL, et al. Patient Registry and Outcomes for Breast Implants and Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma Etiology and Epidemiology (PROFILE): Initial Report of Findings, 2012‐2018. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;143(3S A Review of Breast Implant‐Associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma):65S–73S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Clemens MW, Medeiros LJ, Butler CE, Hunt KK, Fanale MA, Horwitz S, et al. Complete surgical excision is essential for the management of patients with breast implant‐associated anaplastic large‐cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(2):160–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Adrada BE, Miranda RN, Rauch GM, Arribas E, Kanagal‐Shamanna R, Clemens MW, et al. Breast implant‐associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma: Sensitivity, specificity, and findings of imaging studies in 44 patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;147(1):1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. McGuire P, Reisman NR, Murphy DK. Risk Factor Analysis for Capsular Contracture, Malposition, and Late Seroma in Subjects Receiving Natrelle 410 Form‐Stable Silicone Breast Implants. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;139(1):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pinchuk V, Tymofii O. Seroma as a late complication after breast augmentation. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2011;35(3):303–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . Familial breast cancer: classification, care and managing breast cancer and related risks in people with a family history of breast cancer 2013. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg164 [PubMed]

- 39. Adlard J, Burton C, Turton P. Increasing evidence for the association of breast implant‐associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma and Li Fraumeni Syndrome. Case Rep Genet. 2019;2019:5647940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. De Boer M, Hauptmann M, Hijmering NJ, van Noesel CJM, Rakhorst HA, Meijers‐Heijboer HE, et al. Increased prevalence of BRCA1/2 mutations in women with macro‐textured breast implants and anaplastic large cell lymphoma of the breast. Blood. 2020;136(11):1368–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. National Genomic Test Directory Testing Criteria for Rare and Inherited Disease: NHS England; Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp‐content/uploads/2018/08/rare‐and‐inherited‐disease‐eligibility‐criteria‐march‐19.pdf

- 42. Bengtson B, Brody G, Brown M, Glicksman C, Hammond D, Kaplan H, et al. Managing late periprosthetic fluid collections (Seroma) in patients with breast implants: a consensus panel recommendation and review of the literature. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;128(1):1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Seiler SJ, Sharma PB, Hayes JC, Ganti R, Mootz AR, Eads ED, et al. Multimodality imaging‐based evaluation of single‐lumen silicone breast implants for rupture. Radiographics. 2017;37(2):366–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sharma B, Jurgensen‐Rauch A, Pace E, Attygalle AD, Sharma R, Bommier C, et al. Breast implant‐associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma: review and multiparametric imaging paradigms. Radiographics. 2020;40(3):609–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Montes Fernandez M, Ciudad Fernandez MJ, de la Puente YM, Brenes Sanchez J, Benito Arjonilla E, Moreno Dominguez L, et al. Breast implant‐associated Anaplastic large cell lymphoma (BIA‐ALCL): Imaging findings. Breast J. 2019;25(4):728–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Barrington SF, Mikhaeel NG, Kostakoglu L, Meignan M, Hutchings M, Mueller SP, et al. Role of imaging in the staging and response assessment of lymphoma: consensus of the International Conference on Malignant Lymphomas Imaging Working Group. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(27):3048–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Di Napoli A, Pepe G, Giarnieri E, Cippitelli C, Bonifacino A, Mattei M, et al. Cytological diagnostic features of late breast implant seromas: from reactive to anaplastic large cell lymphoma. PLoS One. 2017;12(7):e0181097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . Haematological cancers: improving outcomes NICE guideline [NG47] 2016. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng47 [PubMed]

- 49. Rodriguez‐Pinilla SM, Sanchez‐Garcia FJ, Balague O, Rodriguez‐Justo M, Piris MA. Breast implant‐associated EBV‐positive large B‐cell lymphomas: report of three cases. Haematologica. 2019;105(8):e412–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kadin ME. Regulation of CD30 antigen expression and its potential significance for human disease. Am J Pathol. 2000;156(5):1479–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Jaffe ES, Ashar BS, Clemens MW, Feldman AL, Gaulard P, Miranda RN, et al. Best practices guideline for the pathologic diagnosis of breast implant‐associated anaplastic large‐cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(10):1102–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Laurent C, Delas A, Gaulard P, Haioun C, Moreau A, Xerri L, et al. Breast implant‐associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma: two distinct clinicopathological variants with different outcomes. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(2):306–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Blombery P, Thompson E, Ryland GL, Joyce R, Byrne DJ, Khoo C, et al. Frequent activating STAT3 mutations and novel recurrent genomic abnormalities detected in breast implant‐associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Oncotarget. 2018;9(90):36126–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Laurent C, Nicolae A, Laurent C, Le Bras F, Haioun C, Fataccioli V, et al. Gene alterations in epigenetic modifiers and JAK‐STAT signaling are frequent in breast implant‐associated ALCL. Blood. 2020;135(5):360–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Oishi N, Brody GS, Ketterling RP, Viswanatha DS, He R, Dasari S, et al. Genetic subtyping of breast implant‐associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Blood. 2018;132(5):544–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Letourneau A, Maerevoet M, Milowich D, Dewind R, Bisig B, Missiaglia E, et al. Dual JAK1 and STAT3 mutations in a breast implant‐associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Virchows Arch. 2018;473(4):505–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Di Napoli A, Jain P, Duranti E, Margolskee E, Arancio W, Facchetti F, et al. Targeted next generation sequencing of breast implant‐associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma reveals mutations in JAK/STAT signalling pathway genes, TP53 and DNMT3A. Br J Haematol. 2018;180(5):741–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Turner SD, Inghirami G, Miranda RN, Kadin ME. Cell of Origin and Immunologic events in the pathogenesis of breast implant‐associated anaplastic large‐cell lymphoma. Am J Pathol. 2020;190(1):2–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Turner SD. The Cellular Origins of Breast Implant‐Associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma (BIA‐ALCL): implications for immunogenesis. Aesthet Surg J. 2019;39(Suppl_1):S21‐S7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Blombery P, Thompson ER, Jones K, Arnau GM, Lade S, Markham JF, et al. Whole exome sequencing reveals activating JAK1 and STAT3 mutations in breast implant‐associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Haematologica. 2016;101(9):e387–e390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Pastorello RG, D'Almeida Costa F, Osorio C, Makdissi FBA, Bezerra SM, de Brot M, et al. Breast implant‐associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma in a Li‐FRAUMENI patient: a case report. Diagn Pathol. 2018;13(1):10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Malcolm TI, Hodson DJ, Macintyre EA, Turner SD. Challenging perspectives on the cellular origins of lymphoma. Open Biol. 2016;6(9). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Kadin ME, Morgan J, Xu H, Epstein AL, Sieber D, Hubbard BA, et al. IL‐13 is produced by tumor cells in breast implant‐associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma: implications for pathogenesis. Hum Pathol. 2018;78:54–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Kadin ME. Commentary on: a case report of a breast implant‐associated plasmacytoma and literature review of non‐ALCL breast implant‐associated neoplasms. Aesthet Surg J. 2019;39(7):NP240‐NP2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Zambacos GJ, Molnar C, Mandrekas AD. Silicone lymphadenopathy after breast augmentation: case reports, review of the literature, and current thoughts. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2013;37(2):278–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Lee Y, Song SE, Yoon ES, Bae JW, Jung SP. Extensive silicone lymphadenopathy after breast implant insertion mimicking malignant lymphadenopathy. Ann Surg Treat Res. 2017;93(6):331–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Katzin WE, Centeno JA, Feng LJ, Kiley M, Mullick FG. Pathology of lymph nodes from patients with breast implants: a histologic and spectroscopic evaluation. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29(4):506–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Lamaris GA, Butler CE, Deva AK, Miranda RN, Hunt KK, Connell T, et al. Breast Reconstruction Following Breast Implant‐Associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;143(3S A Review of Breast Implant‐Associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma):51S‐8S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Talagas M, Uguen A, Charles‐Petillon F, Conan‐Charlet V, Marion V, Hu W, et al. Breast implant‐associated anaplastic large‐cell lymphoma can be a diagnostic challenge for pathologists. Acta Cytol. 2014;58(1):103–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Lyapichev KA, Pina‐Oviedo S, Medeiros LJ, Evans MG, Liu H, Miranda AR, et al. A proposal for pathologic processing of breast implant capsules in patients with suspected breast implant anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Mod Pathol. 2019;33(3):367–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Dearden CE, Johnson R, Pettengell R, Devereux S, Cwynarski K, Whittaker S, et al. Guidelines for the management of mature T‐cell and NK‐cell neoplasms (excluding cutaneous T‐cell lymphoma). Br J Haematol. 2011;153(4):451–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Abouyabis AN, Shenoy PJ, Sinha R, Flowers CR, Lechowicz MJ. A systematic review and meta‐analysis of front‐line anthracycline‐based chemotherapy regimens for peripheral T‐cell lymphoma. Isrn Hematol. 2011;2011:623924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Schmitz N, Trumper L, Ziepert M, Nickelsen M, Ho AD, Metzner B, et al. Treatment and prognosis of mature T‐cell and NK‐cell lymphoma: an analysis of patients with T‐cell lymphoma treated in studies of the German High‐Grade Non‐Hodgkin Lymphoma Study Group. Blood. 2010;116(18):3418–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. d'Amore F, Relander T, Lauritzsen GF, Jantunen E, Hagberg H, Anderson H, et al. Up‐front autologous stem‐cell transplantation in peripheral T‐cell lymphoma: NLG‐T‐01. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(25):3093–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. d'Amore F, Gaulard P, Trumper L, Corradini P, Kim WS, Specht L, et al. Peripheral T‐cell lymphomas: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow‐up. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(Suppl 5):v108–v115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Kim YA, Byun JM, Park K, Bae GH, Lee D, Kim DS, et al. Redefining the role of etoposide in first‐line treatment of peripheral T‐cell lymphoma. Blood Adv. 2017;1(24):2138–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Deng S, Lin S, Shen J, Zeng Y. Comparison of CHOP vs CHOPE for treatment of peripheral T‐cell lymphoma: a meta‐analysis. Onco Targets Ther. 2019;12:2335–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Horwitz S, O'Connor OA, Pro B, Illidge T, Fanale M, Advani R, et al. Brentuximab vedotin with chemotherapy for CD30‐positive peripheral T‐cell lymphoma (ECHELON‐2): a global, double‐blind, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2019;393(10168):229–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Pro B, Advani R, Brice P, Bartlett NL, Rosenblatt JD, Illidge T, et al. Brentuximab vedotin (SGN‐35) in patients with relapsed or refractory systemic anaplastic large‐cell lymphoma: results of a phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(18):2190–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Bartlett NL, Chen R, Fanale MA, Brice P, Gopal A, Smith SE, et al. Retreatment with brentuximab vedotin in patients with CD30‐positive hematologic malignancies. J Hematol Oncol. 2014;7:24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Stack A, Levy I. Brentuximab vedotin as monotherapy for unresectable breast implant‐associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Clin Case Rep. 2019;7(5):1003–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Alderuccio JP, Desai A, Yepes MM, Chapman JR, Vega F, Lossos IS. Frontline brentuximab vedotin in breast implant‐associated anaplastic large‐cell lymphoma. Clin Case Rep. 2018;6(4):634–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. El‐Asmar J, Reljic T, Ayala E, Hamadani M, Nishihori T, Kumar A, et al. Efficacy of High‐Dose Therapy and Autologous Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation in Peripheral T Cell Lymphomas as Front‐Line Consolidation or in the Relapsed/Refractory Setting: A Systematic Review/Meta‐Analysis. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2016;22(5):802–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Fossard G, Broussais F, Coelho I, Bailly S, Nicolas‐Virelizier E, Toussaint E, et al. Role of up‐front autologous stem‐cell transplantation in peripheral T‐cell lymphoma for patients in response after induction: an analysis of patients from LYSA centers. Ann Oncol. 2018;29(3):715–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Park SI, Horwitz SM, Foss FM, Pinter‐Brown LC, Carson KR, Rosen ST, et al. The role of autologous stem cell transplantation in patients with nodal peripheral T‐cell lymphomas in first complete remission: report from COMPLETE, a prospective, multicenter cohort study. Cancer. 2019;125(9):1507–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Tang T, Chen Z, Praditsuktavorn P, Khoo LP, Ruan J, Lim ST, et al. Role of surveillance imaging in patients with peripheral T‐cell lymphoma. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2016;16(3):117–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Cederleuf H, Hjort Jakobsen L, Ellin F, de Nully BP, Stauffer Larsen T, Bogsted M, et al. Outcome of peripheral T‐cell lymphoma in first complete remission: a Danish‐Swedish population‐based study. Leuk Lymphoma. 2017;58(12):2815–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Armitage JO. Who benefits from surveillance imaging? J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(21):2579–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Dann EJ, Berkahn L, Mashiach T, Frumer M, Agur A, McDiarmid B, et al. Hodgkin lymphoma patients in first remission: routine positron emission tomography/computerized tomography imaging is not superior to clinical follow‐up for patients with no residual mass. Br J Haematol. 2014;164(5):694–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Thompson CA, Ghesquieres H, Maurer MJ, Cerhan JR, Biron P, Ansell SM, et al. Utility of routine post‐therapy surveillance imaging in diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(31):3506–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Hicks LK, Bering H, Carson KR, Kleinerman J, Kukreti V, Ma A, et al. The ASH Choosing Wisely(R)campaign: five hematologic tests and treatments to question. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2013;2013:9–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]