Abstract

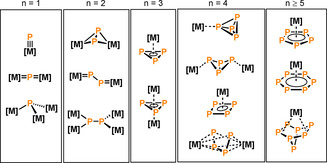

Recently there has been great interest in the reactivity of transition‐metal (TM) centers towards white phosphorus (P4). This has ultimately been motivated by a desire to find TM‐mediated alternatives to the current industrial routes used to transform P4 into myriad useful P‐containing products, which are typically indirect, wasteful, and highly hazardous. Such a TM‐mediated process can be divided into two steps: activation of P4 to generate a polyphosphorus complex TM‐Pn, and subsequent functionalization of this complex to release the desired phosphorus‐containing product. The former step has by now become well established, allowing the isolation of many different TM‐Pn products. In contrast, productive functionalization of these complexes has proven extremely challenging and has been achieved only in a relative handful of cases. In this review we provide a comprehensive summary of successful TM‐Pn functionalization reactions, where TM‐Pn must be accessible by reaction of a TM precursor with P4. We hope that this will provide a useful resource for continuing efforts that are working towards this highly challenging goal of modern synthetic chemistry.

Keywords: coordination compounds, P ligands, radicals, transition metals, white phosphorus

The activation of P4 by transition‐metal complexes has become well established, due to a desire to find new and improved routes for its transformation into useful P‐containing compounds. However, the next necessary step—functionalization of the resulting metal‐bound Pn moieties—has proven extremely challenging and has only occasionally been achieved. Herein, a comprehensive review of these important transformations is provided.

1. Introduction

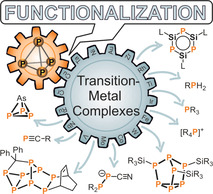

The element phosphorus is essential for life, serving as a building block for DNA and of the cellular energy carrier ATP in all living organisms. [1] In addition, synthetic phosphorus compounds have a huge impact on daily life, [1] being found in (among other things) detergents, fertilizers, insecticides, food products and flame retardants. Organophosphorus derivatives in particular play a crucial role in the chemical and pharmaceutical industries. The industrial precursor for these synthetic compounds is white phosphorus (P4), the most reactive allotrope of the element, which is produced from phosphate rock on a megaton scale annually,[ 2 , 3 ] via reaction of the mineral apatite with quartz sand and coke in an electric arc furnace (Scheme 1a). [1] While most of the P4 produced worldwide is re‐oxidized to provide high‐purity phosphate materials, a significant fraction (ca. 18 %) is used to prepare the myriad valuable organophosphorus compounds that are required by modern society. Unfortunately, the synthesis of these target organophosphorus derivatives is a multistep process, almost always involving the initial chlorination of P4 to PCl3, followed by subsequent functionalization with Grignard or organolithium reagents (Scheme 1b).[ 2 , 3 ] Triphenylphosphane (PPh3), for example, is one of the most synthetically important organophosphorus compounds, and is prepared industrially by high‐temperature reaction of chlorobenzene with PCl3 in the presence of molten sodium. [4] As well as requiring extremely toxic (Cl2), corrosive (PCl3) and pyrophoric (Na) reagents, this route also generates huge amounts of inorganic salt waste (NaCl), which is accumulated as a by‐product. Thus, sustainability and safety concerns each provide a powerful impetus for the urgent overall improvement of such processes. [5]

Scheme 1.

Production of white phosphorus (P4) from the calcium phosphate part of apatite minerals (a) and the synthesis of organophosphorus compounds via PCl3 (b) or PH3 (c) (R=organic residue; X=Cl, Br, I; THPC=tetrakishydroxymethylphosphonium chloride).

In some specific cases alternative methods can be used to transform P4; however, these often suffer from similar problems. For example, alkyl phosphanes and phosphonium salts can be prepared through hydrophosphination of alkenes and ketones (Scheme 1 c), but this requires the intermediacy of extremely toxic PH3 gas. [5] As such, the development of alternative routes that avoid the use of chlorine gas and circumvent the highly toxic intermediates PCl3 or PH3 is currently a topic of great interest. [6] In pursuit of this challenging goal, much emphasis has been placed on understanding the fundamental reactivity of P4 towards reactive metal centers. It is hoped that studying these reactions may ultimately pave the way to effective catalytic methods for converting P4 directly to organophosphorus derivatives.

1.1. Activation of white phosphorus

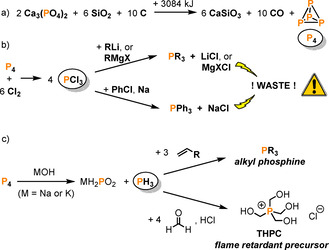

The controlled and consecutive cleavage of P−P bonds within the P4 tetrahedron (often referred to as P4 activation) plays a crucial role in the formation of reactive Pn (n=1–4) units, potentially suitable for further functionalization. As outlined in several reviews, a large number of reactive main group element or transition‐metal compounds has been applied to the activation and degradation of the P4 molecule.[ 3 , 7 , 8 ] Scheme 2 illustrates conceivable degradation pathways starting with the initial formation of “butterfly‐P4” species. The stepwise cleavage of further P−P bonds results in cyclic, branched and linear Pn fragments stabilized by transition metals or main group compounds.

Scheme 2.

A selection of possible reaction pathways for the activation of white phosphorus (P4). Only the Pn backbones of the fragments are shown; charges and substituents are omitted for clarity.

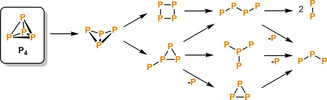

The transition‐metal‐mediated activation of P4 in particular has attracted considerable attention over the last several decades, and has given rise to a plethora of fascinating complexes bearing highly versatile Pn units.[ 3 , 7 ] A complete description of all the Pn ligands known in the literature would exceed the scope of this review. Nevertheless, an overview of common structural Pn motifs is illustrated in Figure 1. Monophosphido ligands, P2 dumbbells or cyclo‐P3 rings can be derived from fragmented P4 molecules (n≤3). Tetraphosphido ligands (n=4) are typically observed either as intact, metal‐bound P4 tetrahedra, or as partially degraded “butterfly” species, P4 rings and chains. Sometimes, the aggregation of multiple phosphorus atoms is also observed (n≥5), which may result in aromatic cyclo‐P5 and cyclo‐P6 ligands, or even extended polyphosphorus cages. In addition to the basic structures summarized in Scheme 2, bridging motifs, metal‐phosphorus multiple bonding, and structures with varying hapticity may also be observed.

Figure 1.

Structural motifs of selected transition‐metal complexes bearing Pn ligands; [M]=transition‐metal complex fragment.

2. Transition‐Metal‐Mediated Functionalization of White Phosphorus

If P4 activation represents the first step of its transformation into potential organophosphorus products, then the second step is functionalization of the resulting Pn moieties through interaction with suitable reagents. However, whereas the activation of P4 has now been extensively investigated, subsequent functionalization remains far less explored. In the last few years, interest in the transfer and incorporation of P4‐derived phosphorus atoms into organic or main group substrates has grown substantially, yet the controlled and selective functionalization of activated phosphorus units is still challenging. In this review, we aim to provide a comprehensive overview of these transition‐metal‐mediated functionalizations of white phosphorus. Throughout the review the term “functionalization” will be used to refer to reactions that involve formation of new chemical bonds between phosphorus and a non‐metal or metaloid element (c.f. P4 “activation”, where the P atoms only form new bonds to the transition metal). Reactions in which P4 is functionalized by a main group reagent in the absence of a transition metal will not be discussed here, but have been reviewed previously.[ 8 , 9 ]

The main part of the review is divided into the following sections: section 2.1 discusses the activation and functionalization of P4 in one step. The following sections discuss the functionalization of transition‐metal coordinated Pn units. The functionalization of P1, P2, und P3 moieties is described in sections 2.2. and 2.3. A large number of publications have focused on complexes with P4 units, and these results are described in section 2.4. Section 2.5. describes the functionalization of larger Pn units with five or more P atoms. Finally, the functionalization of the P4 molecules by transition‐metal‐generated p‐block element radicals is described as an alternative for P4 functionalization in section 2.6.

2.1. One‐Step activation and functionalization

The first transition‐metal‐mediated P4 functionalization reaction was reported in 1974 by Green and co‐workers. [10] They described the reaction of [Cp2MoH2] (1) with an excess of P4 in hot toluene, affording the deep red diphosphene complex [Cp2Mo(η2‐P2H2)] (2), which was crystallographically characterized by Canillo et al. three years later (Scheme 3a). [11] This discovery represented a landmark in phosphorus chemistry, since not only P4 activation, but also functionalization was observed. Specifically, four P−P bonds of the P4 tetrahedron are cleaved and, simultaneously, new P−H bonds are formed by transfer of the hydride ligands from the metal center to phosphorus.

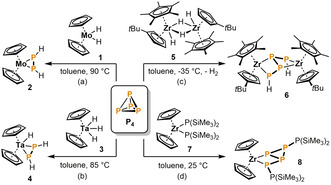

Scheme 3.

Early transition metallocene‐mediated activation of P4 with concomitant functionalization.

More than 20 years later, Stephan and co‐workers provided a further example of such a fragmentation/hydrogenation process (Scheme 3 b). Reaction of the tantalocene trihydride complex [Cp2TaH3] (3) with P4 results in the hydridodiphosphene complex [Cp2Ta(H)(η2‐P2H2)] (4). [12] Interestingly, Chirik et al. found that an analogous reaction of the related zirconium dihydride complex [Cp*2ZrH2] with P4 proceeds differently, and does not give a diphosphene complex. Instead, only P4 activation to the [1.1.0]‐tetraphosphabicyclobutane‐1,4‐diyl (“butterfly‐P4”) complex [Cp*2Zr(η2‐P4)] occurs, along with reductive elimination of H2. [13] They further described the treatment of the sterically more encumbered dinuclear complex [Cp*Cp′ZrH2]2 (5, Cp′=η5‐C5H4 tBu) with P4 (Scheme 3 c). The product molecule [{Cp*Cp′Zr}2(μ2,η2:η2‐P4H2)] (6) features a bridging P4 chain best described as a P4H2 4− tetraanion. Lappert and co‐workers used the zirconium diphosphido complex [Cp2Zr(P(SiMe3)2)2] (7) for a related insertion of a rearranged P4 scaffold into both Zr−P bonds to yield the hexaphosphane‐3,5‐diide complex 8 (Scheme 3 d). [14]

A related approach for the one‐step activation and functionalization of P4 using late transition metals was initially reported by Peruzzini et al. in 1998 (Scheme 4). [15] Rhodium(III) and iridium(III) hydride complexes [(triphos)MH3] (9 a: M=Rh, 9 b: M=Ir; triphos=1,1,1‐tris(diphenylphosphanylmethyl)ethane) enable the direct hydrogenation of P4 to PH3, if conducted in a closed system. The stoichiometric by‐products are the highly stable cyclo‐P3 compounds 10. When carrying out the reaction of 9 a with P4 at lower temperature, or in an open system, the evolution of dihydrogen gas and an isolable intermediate species [(triphos)Rh(η1:η2‐HP4)] (11 a) were observed. Further mechanistic studies performed with the kinetically more stable dihydridoethyl iridium complex [(triphos)IrH2(Et)] (9 c) revealed the initial formation of a butterfly compound [(triphos)Ir(H)(η2‐P4)], which slowly isomerizes to [(triphos)Ir(η1:η2‐HP4)] (11 b).

Scheme 4.

Functionalization of P4 mediated by rhodium and iridium triphos complexes. Reaction conditions: (a) for 9 a: THF, 70 °C; for 9 b THF, 120 °C. (b) for 9 a: open system, THF, 70 °C, ‐H2 or closed system, THF, 40 °C, ‐H2; for 9 c: open system, THF, reflux, ‐C2H6. (c) for 11 a, 11 b: THF, 70 °C; for 11 c, 11 d, 11 e: THF, 60 °C, 20 atm H2. (d) for 11 a, 11 e: +MeOTf; for 11 c: +HBF4⋅OMe2.

Only a year later, Peruzzini et al. successfully extended this concept to P−C bond formation by reporting on analogous hydrocarbon‐substituted tetraphosphido rhodium complexes [(triphos)Rh(η1:η2‐RP4)] (11 c: R=Me; 11 d: R=Et, 11 e:=Ph) derived from the corresponding ethylene complexes [(triphos)Rh(R)(η2‐C2H4)] (12 a) and P4 (Scheme 4). [16] During the reaction the labile ethylene ligand is released while the alkyl and aryl moieties previously bound to the metal center in 12 a selectively migrate to the activated P4 scaffold. Notably, the reaction of P4 with the corresponding hydrido‐ethylene derivative [(triphos)Rh(H)(η2‐C2H4)] (12 b) does not afford the expected product 11 a. Instead, the ethylene ligand inserts into the Rh−H bond and successively gives the ethyltetraphosphido species 11 d. Moreover, the pressurization of 11 c, 11 d and 11 e with H2 at 60 °C induces the formation of 10 a along with the phosphanes RPH2 in moderate yields. The reactivity of complexes 11 was further explored through reactions with electrophiles. [17] The reaction of 11 a and 11 e with MeOTf or MeI gave the doubly functionalized and highly temperature sensitive cations [(triphos)Rh(η1:η2‐MeRP4)]+ (13 a: R=H, 13 b: R=Ph). The fact that 13 a is also obtained by treating 11 c with HBF4⋅OMe2 supports the idea that in this system electrophilic attack generally takes place at the already‐functionalized phosphorus atom.

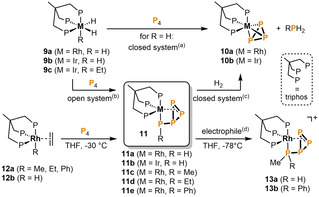

More recently, a joint study by Power, Wolf and co‐workers demonstrated that the low‐coordinate cobalt‐tin cluster 14 serves as a potent agent for one‐step P4 activation and functionalization (Scheme 5 a). [18] During the reaction, the P4 tetrahedron is selectively inserted into the rhombohedral Co2Sn2 cluster core of 14, during which one of the bulky, tin‐bound terphenyl substituents undergoes a migration to phosphorus, thereby forming a new P−C bond. The product 15 bears a terphenyl‐substituted P4 chain and represented the first example of a molecular cluster compound containing phosphorus, cobalt and tin.

Scheme 5.

Arylation of P4 by a low‐coordinate cobalt‐tin cluster (a) and ruthenium‐mediated halogenation (b) and subsequent alkylation of P4 (c).

An even more recent collaboration by the groups of Caporali and Grützmacher dealt with the chlorination of P4 by the 16 valence electron species [Cp*RuCl(PCy3)] (16, Scheme 5b). [19] Promoted by two equivalents of 16, migration of two chloride ligands from ruthenium to an activated P4 unit yields the dinuclear complex [Cp*Ru(PCy3)(μ2,η2:η4‐P4Cl2)RuCp*] (17), containing a planar and unsymmetrically bridging 1,4‐dichlorotetraphosphabutadiene ligand. A selective exchange of the chloro substituents with alkyl groups was achieved by salt metathesis with nBuLi (Scheme 5 c). The product was the tetranuclear compound [(Cp*Ru)4(μ3,η2:η2:η4‐P4 nBu2)2] (18), which features two coplanar [P4 nBu2] moieties.

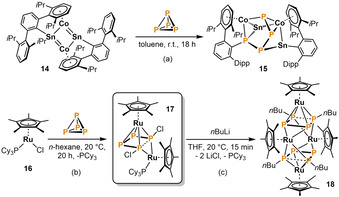

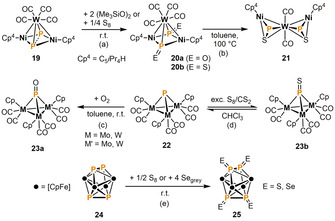

2.2. Functionalization of P1 and P2 ligands

In comparison to the one‐step reactions mentioned above, more versatile transformations can be made feasible by separating P4 activation from the subsequent functionalization step. The following section deals with functionalizations of P1 and P2 ligands derived from P4, which date back to the pioneering work of Scherer et al. in 1991. Oxidation of the Ni2WP2 complex 19 with (Me3SiO)2 affords 20 a, the first complex of PO, the heavier congener of the ubiquitous nitric oxide (NO, Scheme 6a). [20] Oxidation of 19 with S8 similarly affords the isoelectronic PS species 20 b, which undergoes partial loss of CO and rearrangement from μ3:η1 to μ2:η2 coordination of the PS ligands when heated to 100 °C (21, Scheme 6 b). [21] Mays and co‐workers found that a similar μ3‐PO compound (23 a) is formed if the trinuclear species 22 is exposed to atmospheric oxygen (Scheme 6 c). [22] The corresponding oxidation with elemental sulfur is fully reversible and leads to 23 b in the presence of an excess of S8 in CS2 (Scheme 6 d). [23] The reverse reaction to produce 22 takes place in common organic solvents in the absence of an excess S8. Scherer et al. also reported on the synthesis of E=P−P=E ligands in 25 by oxidation of the P2 dumbbells in the Fe4P4 cluster 24 with elemental sulfur or grey selenium (Scheme 6 e). [24]

Scheme 6.

Oxidation of P4‐derived P1 and P2 ligands in the coordination sphere of transition metals.

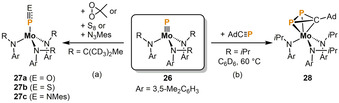

A series of remarkable functionalizations was performed by Cummins and co‐workers using early transition metals triply bound to a terminal phosphido (P3−) ligand. The molybdenum phosphide 26 was reacted with monomeric acetone peroxide, elemental sulfur and mesityl azide (MesN3), giving complexes with terminally‐bound phosphorus monoxide (27 a), phosphorus monosulfide (27 b) and iminophosphenium (27 c) ligands (Scheme 7 a).[ 25 , 26 ] In addition, the phosphaalkyne AdC≡P (Ad=1‐adamantyl) adds to the Mo≡P triple bond in 26 to yield the cyclo‐CP2 complex 28 (Scheme 7 b). [27]

Scheme 7.

P1 functionalization mediated by the molybdenum phosphido complex 26.

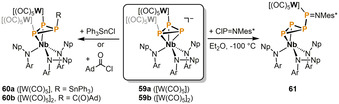

Cummins and co‐workers also subsequently demonstrated the impressive synthetic potential of the anionic niobium complex 29, which is isoelectronic with 26 (Scheme 8). The Nb≡P triple bond in 29 participates in further solvent‐dependent P4 activation. Trapping of 0.5 equivalents of P4 in weakly coordinating solvents affords [(cyclo‐P3)Nb(N[Np]Ar)3]− (Np=CH2 tBu, Ar=3,5‐Me2C6H3), which is structurally related and isolobal to 28. [28] In THF, however, addition of the entire P4 tetrahedron occurs and concomitant migration of one amide ligand onto phosphorus gives the amino functionalized cyclo‐P5 anion 30 (Scheme 8 a). Moreover, the anionic nature of 29 opened up avenues to salt metathesis reactions with electrophiles. Treatment of 29 with divalent group 14 element salts at low temperatures provides the dinuclear compounds 31 containing bridging μ2,η3:η3‐cyclo‐EP2 (E=Ge, Sn, Pb) triangles (Scheme 8 b). [29] The η2‐phosphanyl phosphinidene complexes 32 were accessible by reacting 29 under similar conditions with chlorophosphanes (Scheme 8 c). [30] Silylation and stannylation (compounds 33) at the nucleophilic phosphorus atom were achieved by treating 29 with Me3ECl (E=Si, Sn, Scheme 8 d). Cummins and co‐workers further reported that 29 enables the remarkable transformation of acyl chlorides into the corresponding phosphaalkynes (Scheme 8 e). [31] In fact, the authors described a complete synthetic cycle involving an initially formed niobacyclic intermediate 34, [2+2] fragmentation to give the phosphaalkynes P≡C‐R (R=tBu, Ad) and the niobium(V) oxo product 35, and finally the recycling of 35 by step‐wise deoxygenation, P4 activation and reduction. [32] The reaction of 29 with the chloroiminophosphane ClP=NMes* (Mes*=2,4,6‐tBu3C6H2) gives 36, which bears the diphosphorus analogue of an organic azide ligand (P=P=N‐Mes*) coordinating through the P=P unit in an η2‐fashion (Scheme 8 f). [33] Remarkably, compound 36 serves as a precursor for the thermal release of formal [P≡P] units, which can be quantitatively trapped by using 1,3‐cyclohexadiene to form the Diels‐Alder adduct 37 via a double diene addition. The by‐product of this process is the niobium imide complex [(Mes*N)Nb([Np]NAr)3] (38).

Scheme 8.

Phosphorus functionalization mediated by the niobium phosphide anion 29. (i) Recovery of starting material 29 from 35 proceeds by: 1.+Tf2O in Et2O at −35 °C; 2.+[Mg(thf)3(C14H10)]/‐Mg(OTf)2, ‐C14H10 in THF at −100 °C; 3.+0.25 equiv P4 in THF at r.t.; 4.+Na‐amalgam/‐Hg in THF at r.t.

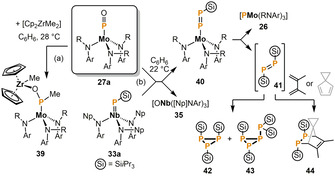

Moreover, Cummins and co‐workers also presented additional functionalizations of the terminal PO ligand in the above‐mentioned molybdenum complex 27 a, mediated by addition of more oxophilic metal species. The nucleophilic attack of one methyl group in [Cp2ZrMe2] at phosphorus gives the MoIV complex 39 in up to 75 % yield (Scheme 9a). [26] An uncommon phospha‐Wittig reaction takes place upon treatment of 27 a with the silyl phosphinidene complex 33 a (Scheme 9 b). [34] This O=P/Nb=PSiiPr3 metathesis generates the oxo niobium compound 35 along with the silyl substituted diphosphenido molybdenum complex 40. In solution, 40 decomposes within days to the phosphido molybdenum complex 26 and the unstable diphosphene 41. Elevated temperatures accelerate this decomposition reaction. The reactive intermediate 41 readily oligomerizes to a mixture of the phosphinidene trimer 42 and tetramer 43, or can be trapped with dienes to form the [2+4] cycloaddition products 44.

Scheme 9.

Transformations of the phosphorus monoxide ligand P=O promoted by combinations of two metal complexes (Ar=3,5‐Me2C6H3; R=C(CD3)2Me; Np=CH2 tBu).

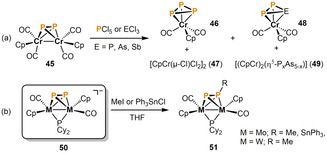

In 2000, Scheer and co‐workers described the functionalization of the chromium complex 45 with group 15 halides (Scheme 10 a). [35] While reactions with PCl5 and PCl3 both lead to the cyclo‐P3 complex 46 and the dinuclear chromium chloride 47, the reactions with ECl3 (E=As, Sb) are very unselective. A complex mixture of products is obtained, including 46, 47, the cyclo‐EP2 complex 48 and various triple‐decker compounds 49. Interestingly, Ruiz and co‐workers found that the closely‐related heavier group 6 complex anions 50 can readily be functionalized with electrophiles affording the methyl‐ or stannyldiphosphenyl bridged species 51 (Scheme 10 b). [36]

Scheme 10.

Functionalization of P2 units mediated by dinuclear group 6 complexes.

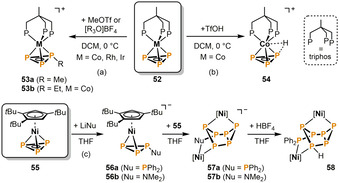

2.3. Functionalization of P3 ligands

The first functionalization of a P3 ligand was reported by Peruzzini and Stoppioni in 1986. Highly electrophilic alkylating agents MeOTf and [Me3O]BF4 were used for the methylation of the cyclo‐P3 moiety in the group 9 triphos complexes 52 (Scheme 11a). [37] The products 53 a contain methyltriphosphirene ligands coordinating in an η3‐mode. It is noteworthy that these alkylations represented the first examples of successful transition‐metal‐mediated functionalization of any polyphosphorus ligand with carbon‐based electrophiles. Four years later, Huttner and co‐workers performed the analogous reaction with [Et3O][BF4], which gave the corresponding ethylated complex 53 b. [38] The protonation of 52 with HOTf gives a different outcome (Scheme 11 b). [39] Spectroscopic and crystallographic investigations indicated that H+ interacts weakly with the heteroatomic CoP3 cluster core in 54 and is most likely located between both phosphorus and cobalt.

Scheme 11.

Reactivity of neutral cyclo‐P3 complexes with electrophiles (top) and nucleophiles (bottom); [Ni]=[Ni(C6H2 tBu3)] (triphos=1,1,1‐tris(diphenylphosphanylmethyl)ethane).

The reactivity of the cyclo‐P3 ligand toward main group nucleophiles was explored by Scheer and co‐workers 30 years later using a related nickel complex (Scheme 11 c). [40] According to variable temperature 31P NMR studies, the reaction of the nickel cyclo‐P3 sandwich compound 55 with LiPPh2 initially forms the intermediate triphosphirene species 56 a, which then rapidly incorporates a second equivalent of 55 and concomitantly rearranges to the heptaphosphane compound 57 a. Since crystallization and purification of 57 a was unsuccessful due to its high sensitivity, protonation with HBF4 was investigated to afford the more stable neutral species 58. The two nickel centers in 58 are bridged by a remarkable bicyclic P6 ligand with an exocyclic PPh2 substituent. By contrast, the reaction of 55 with LiNMe2 gives the η2‐triphosphirene complex 56 b as isolable main product, and 57 b was detected only in minor quantities by 31P NMR spectroscopy.

Further η2‐triphosphirene complexes were obtained by Piro and Cummins by reacting the di‐ and trinuclear cyclo‐P3 complex anions 59 a and 59 b with electrophiles (Scheme 12). [27] Treatment of dinuclear 59 a with Ph3SnCl affords the P‐stannylated compound 60 a, and the reaction of trinuclear 59 b with 1‐adamantanecarbonyl chloride gives the analogous, yet thermally unstable, P‐acyclated species 60 b. When 59 b is reacted with ClP=NMes*, one [W(CO)5] fragment is lost and a shift of the second [W(CO)5] moiety to the iminophosphane P is observed. The product 61 features a Mes*NP[W(CO)5]+ unit that circumambulates around the unsaturated triphosphorus cycle in solution at ambient temperature.

Scheme 12.

Functionalization of cyclo‐P3 units with electrophiles mediated by oligonuclear complex anions (Ar=3,5‐Me2C6H3; Np=CH2 tBu; Mes*=2,4,6‐tBu3C6H2).

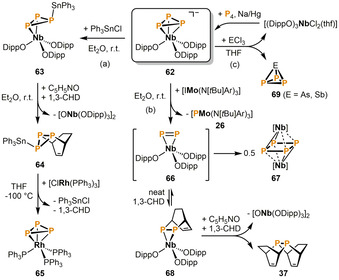

Cummins and co‐workers further demonstrated the exceptional utility of anionic niobium complexes for phosphorus transfer by using the niobate 62 (Scheme 13), which bears phenolato instead of the more established anilido ligands (cf. 29, 59). The reaction of 62 with Ph3SnCl yields the stannyltriphosphirene complex 63, where the Ph3Sn+ moiety rapidly migrates around the cyclo‐P3 ring in solution even at −90 °C (Scheme 13 a). [41] Subsequent liberation of the triphosphirene molecule from the metal center was achieved by converting 63 with the oxidant pyridine‐N‐oxide in the presence of the trapping agent 1,3‐cyclohexadiene. This procedure gave the uncommon Diels‐Alder adduct 64 along with the niobium oxo dimer [ONb(ODipp)3]2. Remarkably, 64 serves as a P3 3− synthon and readily transfers its cyclo‐P3 unit onto [ClRh(PPh3)3]. This reaction involves chloride abstraction from rhodium to eliminate Ph3SnCl, and the release of 1,3‐cyclohexadiene from the diphosphene by [4+2] retrocycloaddition which ultimately affords the cyclo‐P3 rhodium complex 65.

Scheme 13.

Phosphorus transfer reactions promoted by the anionic niobium cyclo‐P3 complex 62; [Nb]=[Nb(ODipp)3] (1,3‐CHD=1,3‐cyclohexadiene).

In a different approach, 62 was reacted with the iodo molybdenum(IV) species [IMo(N[tBu]Ar)3] (Ar=3,5‐Me2C6H3, Scheme 13 b), which acts as a P− abstractor to form [PMo(N[tBu]Ar)3] (c.f. 26, Scheme 7). [42] In this manner, the dinuclear cyclo‐P4 cluster 67 was quantitatively obtained, presumably via an irreversible dimerization of an intermediate P2 species 66. In the presence of the trapping agent 1,3‐cyclohexadiene, an equilibrium with the Diels–Alder product 68 was detected by 31P NMR spectroscopy. Complex 68 could not be isolated as a pure compound due to this equilibrium with 66, which irreversibly dimerizes to 67. However, upon addition of the oxidizing agent pyridine‐N‐oxide, liberation of the diphosphene ligand occurs, affording the above‐mentioned double cycloaddition product 37 (c.f. Scheme 8). Cummins and co‐workers also reported on the facile synthesis of the fascinating binary interpnictogen molecules EP3 (69, E=As, Sb) via salt metathesis reactions of 62 with ECl3 (Scheme 13 c). [43] The niobium dichloride by‐product [(DippO)3NbCl2(thf)] can easily be recycled to the cyclo‐P3 precursor 62 by reduction in the presence of P4.

2.4. Functionalization of P4 ligands

As the formation of P4 ligands is the most common result of transition‐metal‐mediated P4 activation,[ 3 , 7 ] it is not surprising that phosphorus functionalization has mostly been explored for these complexes. These reactions are particularly versatile, depending on the precise nature of the P4 ligand. Thus, the following section is divided into four parts correlating with the successive degradation of the P4 tetrahedron: tetrahedral P4 ligands, [1.1.0]bicyclotetraphosphane‐1,4‐diyl compounds (“butterfly‐P4” ligands), cyclo‐P4 units, and catena‐P4 species.

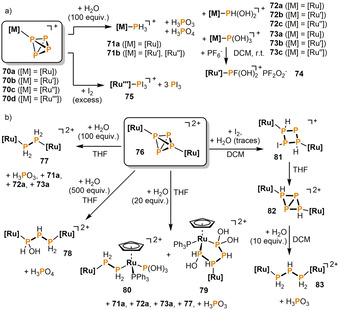

2.5. Tetrahedral P4 ligands

Stoppioni, Peruzzini and co‐workers reported on the hydrolytic disproportionation of intact P4 tetrahedra in the coordination sphere of ruthenium. Such reactivity is remarkable given that free P4 is well known to be indefinitely stable in water at room temperature. [7] The authors found that [CpRu(PPh3)2(η1‐P4)]+ (70 a) almost quantitatively forms the phosphane complex 71 a upon reaction with 100 equiv H2O (Scheme 14 a). [44] By‐products are oxophosphorus species such as phosphorus acid (H3PO3) and phosphoric acid (H3PO4). Substitution of the triphenylphosphane ligands for bidentate 1,2‐(bisdiphenylphosphanly)ethane (dppe), or the sodium salt of meta‐sulfonated triphenylphosphane (TPPMS=Ph2P(m‐C6H4SO3Na) (compounds 70 b and 70 c, respectively), resulted in formation of minor quantities of hydroxyphosphane complexes such as 72 b,c and 73 b,c as side‐products. [45] The composition of the final mixtures strongly depends on the solvent, the temperature and the amount of H2O used. When 73 b is dissolved in DCM, it reacts with its own PF6 − counter anion and gives the fluorodihydroxyphosphane complex [CpRu(dppe){PF(OH)2}] PF2O2 (74) by F/OH substitution. Lapinte, Peruzzini and co‐workers also examined the reaction of the slightly bulkier complex [Cp*Ru(dppe)(η1‐P4)]+ (70 d) with an excess of iodine in CHCl3 at room temperature. [46] Three equivalents of PI3 are released while one molecule of PI3 remains bound to the metal center to form [Cp*Ru(dppe)(PI3)]+ (75).

Scheme 14.

Hydrolysis and halogenations of P4 in the coordination sphere of mononuclear (a) and dinuclear (b) ruthenium complexes; [Ru]=[CpRu(PPh3)2]; [Ru′]=[CpRu(dppe)] (dppe=1,2‐bis(diphenylphosphanyl)ethane); [Ru′′]=[CpRu(TPPMS)2] (TPPMS=Ph2P(m‐C6H4SO3Na)); [Ru′′′]=[Cp*Ru(dppe)].

The dicationic diruthenium complex 76 displays a very complex hydrolysis behavior. When treated with 100 equiv H2O, in a similar manner to 70 a, a diphosphane complex 77 is obtained along with 71 a, 72 a, 73 a and H3PO3 as by‐products (Scheme 14 b). [47] With a much higher excess of water (500 equiv), the reaction becomes selective and gives rise to H3PO3 and the remarkable 1‐hydroxytriphosphane complex 78 in 93 % isolated yield. [48] Reducing the amount of water to only 20 equiv slows down the reaction rate significantly and affords two different compounds as major products: [49] the 1,1,4‐tris(hydroxy)tetraphosphane complex 79 and a dinuclear species 80, which contains a bridging diphosphane and a P(OH)3 ligand. The reaction mixture further contains small amounts of several other species, namely 71 a, 72 a, 73 a, 77 and H3PO3. A different reactivity is observed when 76 is first oxidized with iodine in the presence of traces of water. [50] The initial product is the monocationic diruthenium complex 81, which is stabilizing a cyclic (P4H2I)− anion. In THF, the iodide anion dissociates from the tetraphosphorus ligand, resulting in the ruthenium‐substituted [1.1.0]bicyclotetraphosphane 82 that further hydrolyzes to the triphosphane complex 83 and phosphorous acid.

Krossing comprehensively studied the iodination of the homoleptic silver complex [Ag(η2‐P4)2]+ (84), which features two intact P4 tetrahedra bound in an η2‐fashion and is paired with the very weakly coordinating aluminate anion [Al(ORF)4]− (RF=C(CF3)3, Scheme 15 a). [51] According to low temperature in situ 31P NMR experiments, 84 reacts with 3.5 equivalents of iodine even at −78 °C to give the cationic pentaphosphorus cage P5I2 + (85) along with AgI, PI3 and P4 as by‐products. Quantum chemical calculations indicated that the formation of 85 may proceed via two different pathways: the insertion of an in situ generated PI2 + cation into one P−P bond of white phosphorus, or the intermediate formation of a naked P5 + cation, which then reacts with I2. When the reaction mixture is warmed above −40 °C, 85 rapidly decomposes to the subvalent binary cation P3I6 + (86) and several unidentified by‐products. The Raman and 31P NMR spectroscopic data support the intermediate formation of P2I4 from the remaining PI3 and P4, which reacts with P5I2 + (85) ultimately affording P3I6 + (86) and P4.

Scheme 15.

Halogenation of P4 by silver complexes (a,b) and arylation of P4 with organolithium compounds in the coordination sphere of N‐heterocyclic carbene (NHC) gold cations.

In the same work, a different approach, namely the in situ reaction of [Ag(CH2Cl2)][Al(ORF)4] (87[Al(ORF)4]), P4 and various halogenating agents was also presented (Scheme 15 b). The lighter congener of 85, P5Br2 + (88), was synthesized almost quantitatively by stirring 87[Al(ORF)4] with equimolar amounts of P4 and PBr3 at −78 °C for 8 h. An NMR scale reaction of 87[Al(ORF)4] with white phosphorus and bromine in CS2 at room temperature gave several colorless crystals after redissolving the crude mixture in CDCl3 for an NMR experiment. XRD analysis revealed that these crystals consisted of a dichlorodiorganophosphonium cation [Cl2P(CDCl2)2]+ (89), as its [(RFO)3Al‐F‐Al(ORF)3]− salt. It must be noted that, in this case, the [Al(ORF)4]− anion present in the starting material decomposed to the fluoride bridged [(RFO)3Al‐F‐Al(ORF)3]− anion. 89 is suggested to form via double insertion of a very electrophilic intermediate P+ unit into the C‐Cl bond of CDCl3. Finally, the reaction of 87[Al(ORF)4], P4, and I2 in a molar ratio of 1:2:3.5 resulted in a mixture containing P2I4 and 86[(RFO)3Al‐F‐Al(ORF)3]. Both were identified by XRD analysis performed on single crystals, which were obtained from concentrated CS2 extracts of the crude product.

Lammertsma and co‐workers recently reported that the N‐heterocyclic carbene (NHC) gold complex 90 readily reacts with aryl lithium compounds at low temperatures (Scheme 15 c). [52] The controlled P−C bond formation and concomitant cleavage of one P−P bond gives rise to the proposed intermediate butterfly species 91. Immediate addition of a second [(NHC)Au] fragment, derived through formal loss of P4 from a second equivalent of 90, affords the cationic complex 92 in high yield.

2.6. [1.1.0]Bicyclotetraphosphan‐1,4‐diyl ligands (“butterfly‐P4” ligands)

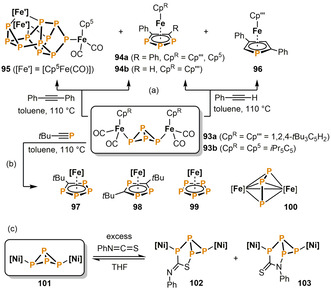

The first functionalizations of [1.1.0]bicyclotetraphosphan‐1,4‐diyl (“butterfly‐P4”) ligands were reported by Scherer et al. Thermolysis of the diiron complexes 93 in the presence of diphenylacetylene affords the triphospholyl species 94 a in moderate yields (Scheme 16 a). [53] In the case of the related compound containing a sterically more demanding pentaisopropylcyclopentadienyl ligand (93 b), the remarkable P11 cage compound 95 is also formed in small quantities. Scheer and co‐workers later extended this concept to other alkynes. Phenylacetylene gives a mixture of the monophospholyl (96) and 1,2,3‐triphospholyl species (94 b). [54] The reaction of 93 a with the phosphaalkyne tBuC≡P produces several compounds (Scheme 16 b). [55] While the tetraphospholyl (97) and the 1,2,4‐ triphospholyl (98) complexes are the main products, minor amounts of pentaphosphaferrocene 99 and the dinuclear triphosphaallyl complex 100 can also be isolated. It is proposed that key steps in these reactions are [3+1] fragmentation of the butterfly framework and subsequent addition of one or two equivalents of alkyne.

Scheme 16.

Addition reactions of unsaturated organic molecules to P4 butterfly complexes; [Ni]=[CpNi(IMes)] (IMes=1,3‐bis(2,4,6‐trimethylphenyl)imidazolin‐2‐ylidene); [Fe]=[Cp′′′Fe].

Wolf and co‐workers found that the N=C and C=S bonds of the heterocumulene phenyl isothiocyanate (PhNCS) reversibly insert into a P−P bond of the P4 butterfly scaffold of the dinuclear nickel complex 101 (Scheme 16 c). [56] The products are the two isomeric bicyclo[3.1.0]heterohexane species 102 and 103, which can be isolated as pure compounds, although they slowly equilibrate with the starting materials 101 and PhNCS in solution.

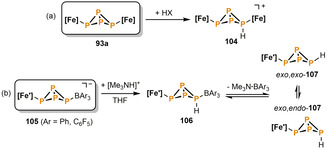

Protonation of the iron butterfly compound 93 a was also investigated by Scheer and co‐workers. According to 31P NMR and computational studies, the acidic proton selectively attacks the more nucleophilic, metal‐bound (“wing tip”) P atom to give the cation 104 (Scheme 17 a). [57] A similar observation was made by Lammertsma and co‐workers. [58] The reaction of the anionic Lewis acid‐stabilized P4‐butterfly compound 105 with [Me3NH][BPh4] initially forms the intermediate wing tip protonated species 106 (Scheme 17 b). Immediate loss of the amine‐borane adduct Me3N⋅BAr3 (Ar=Ph, C6F5) leads to the formation of the neutral bicyclo[1.1.0]tetraphosphabutane isomers exo,endo‐107 and exo,exo‐107. The two isomers were calculated to lie close in energy and readily undergo Lewis acid‐catalyzed isomerization. Moreover, they decompose within one day due to a lack of kinetic stabilization.

Scheme 17.

Iron‐mediated protonation of P4‐butterfly ligands; HX=[(Et2O)H][BF4], [(Et2O)2H][Al(OC(CF3)3]; [Fe]=[Cp′′′Fe(CO)2]; [Fe′]=[Cp*Fe(CO)2].

As also reported by Scheer and co‐workers, the reaction of [Cp′′2Zr(κ2 P‐P4)] (108, Cp′′=1,3‐tBu2C5H3) with the monochlorosilylene 109 in toluene at room temperature gives compounds 110 and 111, which are remarkable phosphorus/silicon analogues of benzene and cyclobutadiene, respectively (Scheme 18 a). [59] Computational studies indicated that 110 possesses considerable aromatic character, whereas 111 is weakly antiaromatic. The aromaticity in both compounds is substantially influenced by the additional donating nitrogen lone pairs of the bidentate PhC(NtBu)2 substituents.

Scheme 18.

Synthesis of phosphorus/silicon analogues of benzene (a) and phosphorus‐rich cage compounds (b) by Zr‐mediated P4 functionalization (L=[PhC(NtBu)2], [Zr]=[Cp′′2Zr], Cp′′=1,3‐tBu2C5H3).

Scheer and co‐workers further reacted 108 with tBuC≡P in boiling toluene to access phosphorus‐rich cage compounds (Scheme 18 b). [60] According to 31P NMR spectroscopic analysis the major product [Cp′′2Zr(κ2 P‐P3CtBu)] (112) is formed along with minor amounts of the carbon/phosphorus cages 113 and 114, which both incorporate a cuneane‐like P5C3 or P6C2 subunit. The authors suggested that 112 is formed by elimination of a P2 unit from 108 and subsequent reaction with tBuC≡P. The released P2 species may be trapped by multiple phosphaalkyne molecules to give metal‐free cages such as 113. 114 derives from the formal addition of two equivalents of tBuC≡P to the starting material 108. The products were successfully separated by fractional crystallization and column chromatography.

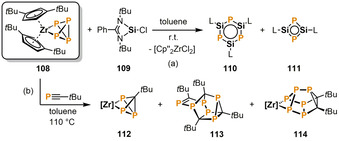

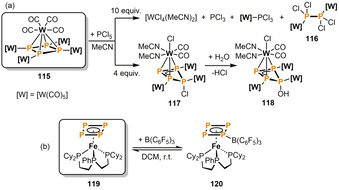

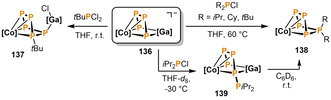

2.7. cyclo‐P4 ligands

Functionalization at cyclo‐P4 ligands is less common than at tetrahedral and butterfly‐P4 ligands, and was first demonstrated by Scheer and co‐workers (Scheme 19). [61] When a tenfold excess of PCl5 is reacted with the pentanuclear cyclo‐P4 complex 115, the main products in the reaction mixture are [WCl4(MeCN)2], PCl3, [W(CO)5(PCl3)], and the dinuclear tetrachlorodiphosphane complex 116. However, these species are only found in minor quantities when the reaction is performed with a smaller amount of PCl5 (4 equiv). The main product in this case is 117, in which a [WCl(CO)2(MeCN)2] fragment is coordinated by a chlorinated cyclo‐P4 ligand through its triphosphaallyl subunit. The isolation of 117 as a pure compound was not successful, because it readily reacts with traces of moisture to give the corresponding hydrolysis product 118.

Scheme 19.

Tungsten‐ and iron‐promoted transformations of cyclo‐P4 ligands; [W]=[W(CO)5].

Mézailles and co‐workers investigated the reactivity of the end‐deck cyclo‐P4 iron complex 119 toward electrophiles (Scheme 19 b). [62] The P‐borylated Lewis adduct 120 is formed in an equilibrium reaction upon treatment of 119 with B(C6F5)3 in DCM.

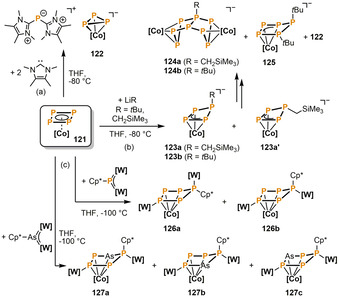

Recently, Scheer and co‐workers reported on the N‐heterocyclic carbene‐induced ring contraction of the end‐deck cyclo‐P4 cobalt sandwich complex 121 (Scheme 20 a). [63] The treatment of 121 with two equivalents of 1,3,4,5‐tetramethylimidazol‐2‐ylidene (NHC) leads to selective abstraction of one phosphorus cation from the four‐membered tetraphosphorus ring. The resulting ionic product consists of a [(NHC)2P]+ cation and a [Cp′′′Co(η3‐cyclo‐P3)]− anion (122, Cp′′′=1,2,4‐tBu3C5H2). This methodology is also applicable to some triple‐decker sandwich complexes bearing cyclo‐P6 middle decks (see Scheme 26, section 2.5).

Scheme 20.

Functionalization of the cyclo‐P4 ligands in the cobalt sandwich complex 121; [Co]=[(1,2,4‐tBu3C5H2)Co].

Scheme 26.

Functionalization of the cyclo‐P6 middle deck in early transition‐metal triple‐decker complexes; [Mo]=[Cp*Mo], [V]=[Cp*V].

The reactivity of 121 towards carbon based nucleophiles was also studied, by the same group. [64] Treatment of 121 with tBuLi and LiCH2SiMe3 in THF at −80 °C gave the axially substituted tetraphosphido complexes [Cp′′′Co(η3‐P4R)]− (123, R=tBu, CH2SiMe3), respectively as initial kinetic products (Scheme 20 b). The anions 123 are metastable, however they can be sufficiently stabilized by trapping the Li+ counter cations with 12‐crown‐4 or [2.2.2]‐cryptand in the cold reaction mixture. By this manner, the authors were able to isolate the [Li(12‐crown‐4)2]‐salt of 123 a as a mixture with its equatorial isomer 123 a′, and pure 123 b as its [Li([2.2.2]‐cryptand)]‐salt at room temperature. Note that a corresponding equatorial isomer of 123 b was not detected. In the absence of complexing crown ethers, 123 a decomposes upon warming to room temperature to give a mixture of products including the abovementioned cyclo‐P3 sandwich anion 122, and the dinuclear complex [(Cp′′′Co)2(μ,η3:η3‐P8CH2SiMe3)]− (124 a), which features an alkyl substituted bicyclo[3.3.0]octaphosphane ligand. Interestingly, a different product mixture is obtained from the decomposition of 123 b. Besides the analogous P8 tBu complex 124 b and 122, in this case, [Cp′′′Co(η3‐P5 tBu2)]− (125) is also formed, which bears a 1,2‐diorgano substituted cyclo‐P5 ligand.

Scheer and co‐workers also investigated ring expansions of 121 upon reaction with the pnictinidene complexes [Cp*E{W(CO)5}2] (E=P, As, Scheme 20 c). [65] The insertion of the phosphinidene into the P4 ring is followed by a shift of one [W(CO)5] unit and affords the two isomeric η4‐cyclo‐P5 species 126 a and 126 b, which differ only in the orientation of the tungsten pentacarbonyl and the Cp* substituents. Interestingly, when 121 is reacted with the analogous arsinidene, all substituents previously bound to arsenic migrate to phosphorus resulting in several η4‐cyclo‐P4As isomers (127 a‐c), which differ in the location of the arsenic atom within the five‐membered ring.

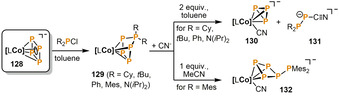

Very recently, Wolf and co‐workers described a highly selective P4 functionalization and subsequent fragmentation in the coordination sphere of a cobalt α‐diimine complex (Scheme 21). [66] The reaction of the cyclo‐P4 cobaltate anion [LCo(η4‐P4)]− (128, L=bis(2,6‐diisopropylphenyl)phenanthrene‐9,10‐diimine) with R2PCl (R=Cy, tBu, Ph, Mes, N(iPr)2) quantitatively gives the neutral cyclo‐P5R2 complexes 129 in up to 77 % isolated yield. Depending on the substituent R, different reaction outcomes are observed upon treatment of 129 with cyanide salts ([K(18‐crown‐6)]CN, [Et4N]CN, [nBu4N]CN). When R=Cy, tBu, Ph or N(iPr)2 reaction with two equivalents of CN− induces a remarkable [3+2] fragmentation, resulting in formation of the anionic cyclotriphosphido cobalt complex 130 and 1‐cyanodiphosphan‐1‐ide anions 131. By contrast, if 129 bears bulky mesityl substituents, the reaction reaches full conversion with only one equivalent of CN−. The product in this case is 132, which features a rearranged P5Mes2 ligand. The authors suggested that similar cyclotetraphosphido complexes may be key intermediates in the fragmentations that ultimately lead to 130 and 131, but that the bulky mesityl substituent in 129 hinders such onward reactivity.

Scheme 21.

Functionalization of a cyclo‐P4 ligand with diorganochlorophosphanes R2PCl (R=Cy, tBu, Ph, Mes, N(iPr)2) mediated by a low valent α‐diimine cobalt complex, and subsequent rearrangement and fragmentation reactions (L=bis(2,6‐diisopropylphenyl)phenanthrene‐9,10‐diimine).

2.8. P4 chains

Wolf and co‐workers demonstrated the first functionalization of P4 chains in the coordination sphere of 3d metalate anions. Reaction of the diiron compound 133 with one equivalent of Et3N⋅HCl or [H(Et2O)2][BArF 4] (ArF=3,5‐(CF3)2C6H3) affords the protonated ferrate 134 in moderate yields (Scheme 22). [67] Crystallographic, spectroscopic and computational investigations indicated that the proton is highly mobile, and simultaneously bound to both iron and phosphorus. Treatment of 133 with an excess of Me3SiCl results in liberation of the phosphorus scaffold from the iron center to give a mixture of PH(SiMe3)2, P(SiMe3)3 and the nortricyclane compound P7(SiMe3)3 (135) in a ratio of 1:1:10.

Scheme 22.

Functionalization of the bridging P4 chain in the ferrate 133 with electrophiles (Ar=4‐ethylphenyl; ArF=3,5‐(CF3)2C6H3).

The heterodinuclear complex 136, which features a catena‐P4 unit, readily undergoes P−P condensation reactions with chlorophosphanes (Scheme 23). [68] The reaction with tBuPCl2 affords a cyclo‐P5 cobalt complex 137 with a concomitant chloride shift from P to Ga. By contrast, a different outcome is observed upon reaction of 136 with the dialkylmonochlorophosphanes R2PCl (R=iPr, Cy, tBu). In this case, the N‐heterocyclic gallylene [Ga(nacnac)] (nacnac=CH[CMeN(2,6‐iPr2C6H3)]2) is released, affording the mononuclear cyclo‐P5R2 cobalt complexes 138. Variable temperature NMR studies on the reaction with iPr2PCl revealed the formation of two intermediate species, likely being constitutional isomers, of which the more abundant could be crystallographically identified as the neutral catena‐P5 iPr2 complex 139.

Scheme 23.

Functionalization of the catena‐P4 unit in the cobaltate complex 136 with chlorophosphanes; [Co]=[CoBIAN] (BIAN=bis(mesityl)iminoacenaphthene); [Ga]=[Ga(nacnac)] (nacnac=CH[CMeN(2,6‐iPr2C6H3)]2).

2.9. Functionalization of Pn ligands (n≥5)

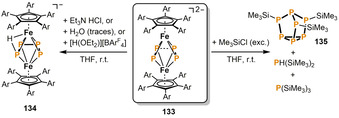

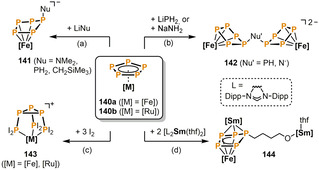

To date the functionalization of white phosphorus‐derived Pn ligands with n≥5 has been only scarcely explored. Scheer and co‐workers treated the pentaphosphaferrocene [Cp*Fe(η5‐P5)] (140 a) with a set of main group nucleophiles and thus obtained P‐functionalized η4‐P5 ferrate complexes. [69] Distinct reactivity was observed depending on the nucleophile. While LiCH2SiMe3, LiNMe2, and LiPH2 gave rise to mononuclear complexes 141 (Scheme 24 a, minor product for LiPH2), the formation of dinuclear complexes 142 (Scheme 24 b) occurred upon reaction with NaNH2 and LiPH2 (major product). The iodination of 140 a and its heavier congener [Cp*Ru(η5‐P5)] (140 b) was also investigated by the same group (Scheme 24 c). [70] Layering dichloromethane solutions of 140 with three equivalents of iodine dissolved in MeCN selectively gives the monocationic complexes 143 as insoluble crystalline solids. Compounds 143 feature a unique tripodal cyclo‐P3(PI2)3 ligand in an all‐cis conformation.

Scheme 24.

Functionalization of a cyclo‐P5 ligand by nucleophiles (a,b), iodination (c) and thf ring‐opening (d); [Fe]=[Cp*Fe], [Ru]=[Cp*Ru], [Sm]=[L2Sm], L=N,N′‐bis(2,6‐diisopropylphenyl)formamidinate).

Roesky and co‐workers reported on the SmII induced reduction and concomitant functionalization of the cyclo‐P5 ligand in 140 a (Scheme 24 d). [71] The trinuclear complex 144 was obtained in 59 % yield by reacting 140 a with two equivalents of the bulky samarium complex [L2Sm(thf)2] (L=N,N′‐bis(2,6‐diisopropylphenyl)formamidinate) in refluxing heptane for seven days. During the reaction the P5 unit is reduced and ring opening of a coordinated thf molecule occurs. The formation of a new P−C bond ultimately affords an oxidobutyl substituted pentaphosphido ligand bridging the [Cp*Fe], [L2Sm] and [L2Sm(thf)] fragments in an η4:η3:η1‐fashion.

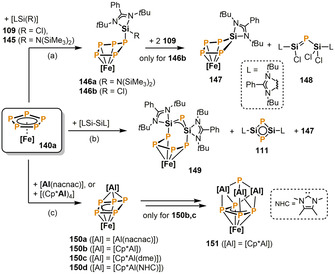

Furthermore, the reactivity of 140 a was also investigated toward silylenes in a very recent collaboration between the groups of Scheer and Roesky. [72] Treatment of 140 a with one equivalent of the sterically encumbered silylene [LSi{N(SiMe3)2}] (145, L=[PhC(NtBu)2]) affords the Si‐substituted η4‐P5 compound 146 a in 79 % isolated yield (Scheme 25 a). A different reaction outcome is observed when the less bulky silylene [LSi(Cl)] (109, three equivalents) is reacted with 140 a. A simultaneous extrusion and insertion process results in the selective formation of the phosphasilene species 148 and [Cp*Fe(η4‐P4SiL)] (147), which was formally described as a P4 4− ligand bridging between [Cp*Fe]+ and [LSi]3+ cations. According to a 31P{1H} VT‐NMR experiment, in this case, 146 b, a cyclo‐P5 species analogous to 146 a, is formed only as an intermediate at −70 °C. The reaction of 140 a with an equimolar amount of the formal SiI compound [LSi‐SiL] gives [Cp*Fe{η4‐P5(SiL)2}] (149) via double ring expansion of the cyclo‐P5 ring to afford a remarkable seven‐membered cyclo‐Si2P5 ring (Scheme 25 b). Considerable quantities of 147 and [L2Si2P2] (111, see Scheme 18, section 2.4.2) were detected as by‐products in the 31P{1H} NMR spectrum of the crude reaction mixture.

Scheme 25.

Functionalization of the cyclo‐P5 ligand in pentamethylpentaphosphaferrocene 140 a by heavy carbene analogues. [Fe]=[Cp*Fe], L=[PhC(NtBu)2, nacnac=CH[CMeN(2,6‐iPr2C6H3)]2), dme=dimethoxyethane, NHC=1,3,4,5‐tetramethylimidazol‐2‐ylidene.

Roesky and co‐workers also studied the reaction of 140 a toward related low valent aluminium compounds. [73] Treatment of 140 a with an equimolar amount of [Al(nacnac)] (nacnac=CH[CMeN(2,6‐iPr2C6H3)]2) at room temperature afforded the triple‐decker type complex [(nacnacAl)(μ2,η3:η4‐P5)FeCp*] (150 a), which features a bent cyclo‐P5 middle‐deck (Scheme 25 c). By contrast, reacting 140 a with [(Cp*Al)4] led to the Al‐Fe cluster compound 151, containing a bridging monophosphido ligand (η3‐P) and a tetraphosphorus chain. A related [4+1] fragmentation of the cyclo‐P5 ring in 140 a was also observed in the abovementioned reactions with silylenes (c.f. 149). The authors suggest that the reaction proceeds via the intermediate formation of 150 b and subsequent regioselective insertion of [Cp*Al] fragments into two adjacent P−P bonds. In fact, the donor stabilized compound 150 c was detected by NMR spectroscopy in the presence of dimethoxyethane (dme) and 150 d could even be successfully isolated and characterized by trapping with 1,3,4,5‐tetramethylimidazol‐2‐ylidene (NHC).

As mentioned in section 2.4.3 (Scheme 20), Scheer and co‐workers have demonstrated that the N‐heterocyclic carbene 1,3,4,5‐tetramethylimidazol‐2‐ylidene (NHC) is a valuable reagent for the contraction of a cyclo‐P4 ring. [63] In the same work, this concept was also applied to the early transition‐metal triple‐decker sandwich complexes [(Cp*M)2(μ,η6:η6‐P6)] (152, M=V, Mo, Scheme 26). Thus, the reaction of the dimolybdenum species 152 a with two equivalents of NHC selectively extracts a phosphorus cation from the cyclo‐P6 middle deck, affording the bis(NHC)‐supported PI cation [(NHC)2P]+ and the molybdate anion 153. According to the crystallographic data, the anticipated cyclo‐P5 ring in 153 is best described as separated P3 and P2 units. The reaction of the divanadium complex 152 b with NHC is less selective. The two ionic species [(NHC)2P][(Cp*V)2(μ,η6:η6‐P6)] (154) and [(NHC)2P][(Cp*V)2(μ,η5:η5‐P5)] (155) were isolated as a co‐crystalline mixture from a THF extract. While 154 is probably formed by one electron reduction of the starting material 152 b, 155 derives from phosphorus cation abstraction from 152 b. The third identified product was the neutral complex 156, which features two bridging ligands: a triphosphaallylic P3 chain and an NHC‐P phosphinidenide unit.

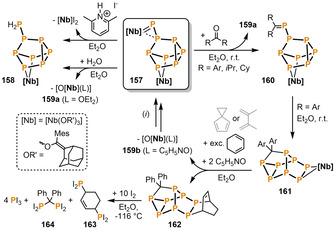

Separately, Cummins and co‐workers found that the diniobium octaphosphide complex 157 possesses a reactive phosphinidene moiety, which readily hydrolyzes to give the mononuclear phosphanyl‐substituted heptaphosphide complex 158 and the oxo niobium species 159 a (Scheme 27). [74] The former compound could also be synthesized in a more selective manner by protonation of 157 with two equivalents of 2,6‐dimethylpyridinium iodide. In this case, the corresponding niobium diiodide complex is the stoichiometric by‐product. Remarkably, 157 also undergoes Nb=P/O=C metathesis with ketones. [75] While the resulting alkyl substituted phosphaalkene complexes 160 are stable for up to several days at ambient temperature, the corresponding aryl derivatives immediately undergo an electrocyclic rearrangement ultimately affording the saturated organophosphorus cluster compounds 161. The carbophosphorus cluster can be liberated from niobium by treatment with two equivalents of pyridine‐N‐oxide in the presence of an excess of 1,3‐cyclohexadiene, leading to the Diels–Alder product 162. [76] Moreover, [4+2] cycloaddition with the niobium‐bound diphosphene moiety in 161 also takes place when 2,3‐dimethylbutadiene or spiro[2.4]hepta‐4,6‐diene are used as dienes, and the niobium oxo compounds 159 a and 159 b can be recycled by step‐wise deoxygenation, reduction and P4 activation. Furthermore, Cummins and co‐workers described the remarkable reactivity of 162 towards ten equivalents of iodine, which cleanly affords four molecules of PI3 along with the bis(diiodophosphanyl)‐substituted hydrocarbons 163 and 164.

Scheme 27.

Niobium‐mediated functionalization of a P8 framework; [Nb]=[Nb(OR′)3] (OR′=(adamantane‐2‐ylidene)(mesityl)methanolate); Ar=Ph, 4‐Cl‐C6H4, 4‐Me‐C6H4, 4‐OMe‐C6H4, 4‐NMe2‐C6H4, 4‐CF3‐C6H4). (i) Recovery of starting material 157 (0.5 equiv) proceeds by: 1. +O(OCCF3)2, +2 equiv Me3SiI/‐Me3SiO(OCCF3) in Et2O; 2. +SmI2/‐SmI3 in THF; 3. +P4 in toluene.

2.10. Radical functionalization of P4

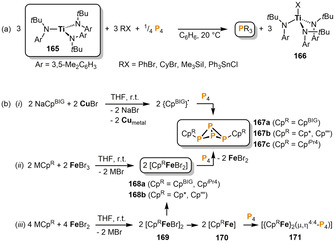

While the reactions described thus far have all proceeded through direct coordination of Pn fragments, it has also proven possible for transition metals to mediate the functionalization of P4 in an outer sphere manner, not necessarily involving the formation of intermediate (poly)phosphorus complexes. In particular, it has been found that transition metals can be used to induce the formation of free carbon‐ (or other main group element‐) centered radicals, which induce successive, homolytic P−P bond cleavage reactions, resulting in stepwise degradation of the P4 molecule. A related, metal‐free concept was originally demonstrated by Barton and co‐workers, using alkyl radicals generated by the decomposition of pyridine thione oxycarbonyl esters (Barton's PTOC esters). [77] Cummins and co‐workers used the three‐coordinate TiIII complex [Ti(N[tBu]Ar)3] (165, Ar=3,5‐C6H3Me2) for stoichiometric halogen radical abstraction from main group element halides RX (RX=PhBr, CyBr, Me3SiI, Ph3SnCl) to give the TiIV species 166 (Scheme 28 a). [78] The concomitantly‐formed R. radicals successively break down the P4 tetrahedron, ultimately affording the respective phosphanes PR3 in certain cases. While quantitative conversion is observed for the heavier group 14 element halides Me3SiI and Ph3SnCl, considerable amounts of the diphosphanes P2R4 are found as by‐products in the analogous reactions with CyBr and PhBr. However, with an excess (5 equiv) of 165 and RX, these reactions also become quantitative. When more sterically demanding aryl groups such as Mes and Ar* (2,6‐Mes2C6H3) are used, the stepwise P4 degradation does not proceed to completion, but instead results in the triphosphirane P3Mes3 or the bicyclo[1.1.0]tetraphosphabutane (butterfly) species exo,endo‐Ar*2P4, respectively.

Scheme 28.

Radical functionalization of P4 mediated by early (a) and late (b) transition metals. (i) only for CpBIG; (ii) MCpR=NaCpBIG, NaCp′′′, LiCp*, NaCpiPr4; (iii) only for MCpR=NaCp′′′, LiCp* (CpBIG=C5(4‐nBu‐C6H4)5; Cp′′′=C5H2 tBu3; Cp*=C5Me5; CpiPr4=C5HiPr4).

Scheer reported on the synthesis of the organic exo,exo‐substituted P4 butterfly compounds 167 by the one‐pot reactions of P4 with metal‐generated cyclopentadienyl radicals (Scheme 28 b). [79] The required radicals were formed via three different pathways: (i) The treatment of NaCpBIG (CpBIG=C5(4‐nBu‐C6H4)5) with CuBr led to precipitation of metallic copper along with dark blue {CpBIG}. radicals, which were detected by EPR spectroscopy and selectively give 167 a upon addition of P4. (ii) The reaction of the alkali cyclopentadienide salts MCpR (=NaCpBIG, NaCp′′′, LiCp*, NaCpiPr4) with FeBr3 afforded the intermediate FeIII complexes 168, which readily transfer CpR. radicals onto the P4 tetrahedron, giving 167 upon loss of FeBr2. (iii) The corresponding FeII complexes 169 synthesized from MCpR (=NaCp′′′, LiCp*) and FeBr2 resulted in the P4 butterfly species 167 b when reacted with P4. The reaction mechanism in this case is suggested to involve disproportionation of 169 into the FeIII complexes 168 b, which undergo the abovementioned reaction with P4, and FeI intermediates 170 that form the dinuclear species 171 bearing a bridging catena‐P4 ligand.

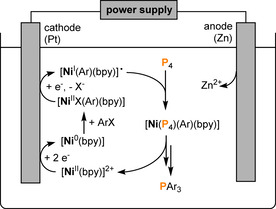

Furthermore, Yakhvarov and Budnikova have reported on electrochemical methods for radical functionalization of P4.[ 80 , 81 ] Their work has recently been reviewed in detail.[ 82 , 83 ] The reaction principle is based on the electrocatalytic C−P bond formation mediated by bipyridine (bpy) nickel complexes. Figure 2 exemplifies a suggested schematic catalytic cycle for the nickel‐promoted transformation of P4 into organophosphorus compounds. The proposed mechanism involves the cathodic electrogeneration of active Ni0 complexes from the corresponding NiII species, followed by the oxidative addition of aryl halides ArX. [81] The resulting organonickel aryl complex [NiX(Ar)(bpy)] is inert towards P4. However, after electrochemical one‐electron reduction, the radical species [Ni(Ar)(bpy)]. immediately incorporates the P4 molecule. [83] Subsequent aqueous work‐up ultimately affords tertiary phosphanes and phosphane oxides. Note that the metal ions generated from the electrochemically soluble (sacrificial) anode are required to stabilize anionic phosphido intermediates and thus prevent undesired phosphorus polymerization processes. Depending on the anode material, different organophosphorus products are formed. [84] While a zinc anode mainly leads to the formation of tertiary phosphanes, an aluminium anode instead results in phosphane oxide formation. By contrast, use of a magnesium anode gives cyclic polyphosphorus compounds, such as (PhP)5.

Figure 2.

Proposed mechanism for nickel‐electrocatalyzed arylation of white phosphorus in DMF or MeCN carried out in an undivided cell (bpy=2,2′‐bipyridine).

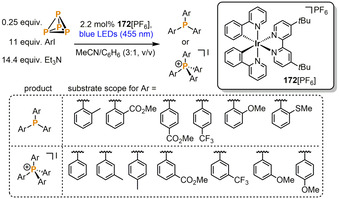

Very recently, Wolf and co‐workers described the direct and photocatalytic synthesis of triarylphosphanes and tetraarylphosphonium salts from P4, aryl iodides, and triethylamine as a terminal electron donor (Scheme 29). [85] Based on the phosphorus atoms (0.25 equiv P4), the reaction uses an excess of aryl iodide (11 equiv) and Et3N (14.4 equiv) and is catalyzed by the commercially available photocatalyst [Ir(dtbbpy)(ppy)2][PF6] (172[PF6], 2.2 mol %, dtbbpy=4,4′‐di‐tert‐butyl‐2,2′‐bipyridine, ppy=2‐(2‐pyridyl)phenyl) under blue LED light (455 nm). Depending on the steric and electronic nature of the aryl iodide substrate the formation of either the triarylphosphanes or tetraarylphosphonium salts is favored (Scheme 29). The resulting organophosphorus compounds can be isolated in up to 71 % yield. Both electron‐withdrawing groups and additional steric bulk at the ortho‐position support the formation of phosphanes over phosphonium salts. Further increase of the steric demand of the substrate gives even less substituted phosphanes: the secondary phosphane Mes2PH is formed from mesityl iodide, and use of 2,6‐dimesitylphenyl iodide (Ar*I) gives rise to the primary phosphane Ar*PH2. These observations are in line with mechanistic studies performed on the reaction using iodobenzene, which support a stepwise mechanism that sequentially produces primary phosphanes (PhPH2), secondary phosphanes (Ph2PH), tertiary phosphanes (Ph3P) and finally the phosphonium salts (Ph4P+). According to emission quenching experiments and redox potential measurements it is likely that the excited state of the photocatalyst 172 + is reductively quenched by Et3N, generating the neutral complex 172, which in turn reduces PhI to the corresponding phenyl radical Ph⋅. White phosphorus is then rapidly consumed by these radicals. As well as aryl‐substituted products, the same methodology could also be used to prepare the tin‐substituted phosphane P(SnPh3)3, starting from Ph3SnCl.

Scheme 29.

Photocatalytic functionalization of P4 to triarylphosphanes and tetraarylphosphonium salts.

3. Summary and Outlook

Building on the pioneering work of Green, Stoppioni and Peruzzini in the 1970s and 1980s, the transition‐metal‐mediated functionalization of white phosphorus has developed greatly over the past several decades. Scientists from around the globe have contributed to this branch of phosphorus chemistry, and demonstrated the synthetic potential of P4 functionalization for the formation of diverse and unprecedented phosphorus compounds. A considerable number of transition‐metal complexes bearing Pn ligands derived from P4 activation have been used for subsequent P4 functionalization (sections 2.2–2.5). By contrast, only a few hydrido or alkyl complexes have shown the potential to both activate and functionalize P4 in a single reaction (section 2.1), and even fewer complexes are currently capable of promoting outer sphere, radical functionalization (section 2.6). To date, neutral complexes have been employed more often for P4 functionalization than ionic ones. However, out of the charged systems, anionic complexes have generally proven to be better platforms than cations. This may be attributed to the fact that by far the most common reactants for P4 functionalizations are electrophiles. Attack at nucleophilic phosphorus sites is often accompanied by metathetical halide abstraction, which provides the driving force for these reactions. Hydrolyses, oxidations, cycloadditions, and reactions with nucleophiles have been reported much less frequently. Many of these functionalizations have given rise to remarkable new mono‐ or oligophosphorus complexes. However, the liberation of these P‐rich species from the complexing metal centers is challenging and thus far has seldom been achieved. Nevertheless, some fascinating compounds, such as EP3 (E=As, Sb) prepared by Cummins and the P‐Si analogue of benzene reported by Scheer have been synthesized via these approaches. It is worth noting that, while P4 functionalization at both early and late transition metals has been established to similar extents, release from the metal has mostly been observed at early transition‐metal systems. This is probably due to the higher oxophilicity of these metals, which can be exploited in ligand liberation reactions with oxidizing agents (e.g. pyridine‐N‐oxide).

Despite the growing number of successful phosphorus functionalization reactions, the ultimate goal, namely the general circumvention of chlorine gas and PCl3 in the industrial formation of useful organophosphorus species, is still far from being reached. Nevertheless, we hope that careful evaluation of the above‐mentioned literature may help chemists to begin to predict the outcome of their prospective functionalization reactions, and hence further accelerate the progress being made in this fundamental area of modern phosphorus chemistry.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Biographical Information

Christian M. Hoidn was born in Zwiesel, Germany, in 1991 and studied chemistry at the University of Regensburg, Germany, where he received his bachelor's degree in 2013 and his M.Sc. diploma in 2015. Recently, he completed his doctoral studies under the supervision of Prof. Dr. Robert Wolf, which focused on the synthesis and characterization of low‐valent 3d metal complexes and their application for the activation and functionalization of white phosphorus. He was awarded with a Ph.D. scholarship of the Foundation of German Business (Stiftung der Deutschen Wirtschaft, sdw).

Biographical Information

Daniel Scott earned his PhD from Imperial College London under the supervision of Dr. Andrew Ashley and Prof. Matthew Fuchter. He subsequently completed an EPSRC doctoral prize fellowship at the same institution, and is currently an Alexander von Humboldt fellow working at the University of Regensburg within the research group of Prof. Dr. Robert Wolf. His research interests revolve around the activation and functionalization of small molecules, mediated by both main group systems and low‐valent transition‐metal complexes.

Biographical Information

Robert Wolf started his research career at the University of Cambridge, UK, under the guidance of Dominic S. Wright. He was awarded a PhD from Leipzig University for work in phosphorus chemistry supervised by Evamarie Hey‐Hawkins. After postdoctoral research with Philip P. Power (UC Davis, USA) and Koop Lammertsma (VU Amsterdam, The Netherlands), he started his independent career at the University of Münster (mentor: Werner Uhl). He became Professor of Inorganic Chemistry at the University of Regensburg in 2011. In 2017, he received an ERC Consolidator Grant for the development of new methods for the functionalization of white phosphorus.

Acknowledgements

R.W. would like thank a number of dedicated former and present co‐workers for their vital contributions to the group's research in the field. Their names are in the references. In addition, generous financial support by the European Research Council (CoG 772299), the Alexander von Humboldt foundation (fellowship to D.J.S.), and the Stiftung der Deutschen Wirtschaft (sdw, PhD scholarship to C.M.H.) is gratefully acknowledged. Open access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

C. M. Hoidn, D. J. Scott, R. Wolf, Chem. Eur. J. 2021, 27, 1886.

References

- 1. Holleman A. F., Wiberg E., Wiberg N., Anorganische Chemie, Band 1 Grundlagen und Hauptgruppenelemente, de Gruyter, Berlin, 2017, p. 846. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Peruzzini M., Gonsalvi L., Romerosa A., Chem. Soc. Rev. 2005, 34, 1038–1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cossairt B. M., Piro N. A., Cummins C. C., Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 4164–4177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Corbridge D., Phosphorus: An Outline of its Chemistry, Biochemistry and Technology, Elsevier, New York, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Elvers B., Ullmann F., Ullmann's encyclopedia of industrial chemistry, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Some recent reports have also sought to bypass P4 entirely and prepare P1 products directly from phosphate materials:

- 6a. Geeson M. B., Ríos P., Transue W. J., Cummins C. C., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 6375–6384; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6b. Geeson M. B., Cummins C. C., Science 2018, 359, 1383–1385; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6c. Geeson M. B., Cummins C. C., ACS Cent. Sci. 2020, 6, 848–860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Caporali M., Gonsalvi L., Rossin A., Peruzzini M., Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 4178–4235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Scheer M., Balázs G., Seitz A., Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 4236–4256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.

- 9a. Borger J. E., Ehlers A. W., Slootweg J. C., Lammertsma K., Chem. Eur. J. 2017, 23, 11738–11746; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9b. Giffin N. A., Masuda J. D., Coord. Chem. Rev. 2011, 255, 1342–1359; [Google Scholar]

- 9c. Khan S., Sen S. S., Roesky H. W., Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 2169–2179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Green J. C., Green M. L. H., Morris G. E., J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1974, 212–213. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cannillo E., Coda A., Prout K., Daran J.-C., Acta Crystallogr. B 1977, 33, 2608–2611. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Etkin N., Benson M. T., Courtenay S., McGlinchey M. J., Bain A. D., Stephan D. W., Organometallics 1997, 16, 3504–3510. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chirik P. J., Pool J. A., Lobkovsky E., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2002, 41, 3463–3465; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2002, 114, 3613–3615. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hey E., Lappert M. F., Atwood J. L., Bott S. G., J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1987, 597–598. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Peruzzini M., Ramirez J. A., Vizza F., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1998, 37, 2255–2257; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 1998, 110, 2376–2378. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Barbaro P., Peruzzini M., Ramirez J. A., Vizza F., Organometallics 1999, 18, 4237–4240. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Barbaro P., Ienco A., Mealli C., Peruzzini M., Scherer O. J., Schmitt G., Vizza F., Wolmershäuser G., Chem. Eur. J. 2003, 9, 5195–5210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hoidn C. M., Rödl C., McCrea-Hendrick M. L., Block T., Pöttgen R., Ehlers A. W., Power P. P., Wolf R., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 13195–13199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bispinghoff M., Benkő Z., Grützmacher H., Calvo F. D., Caporali M., Peruzzini M., Dalton Trans. 2019, 48, 3593–3600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Scherer O. J., Braun J., Walther P., Heckmann G., Wolmershäuser G., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1991, 30, 852–854; [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 1991, 103, 861–863. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Scherer O. J., Vondung C., Wolmershäuser G., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1997, 36, 1303–1305; [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 1997, 109, 1360–1362. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Davies J. E., Klunduk M. C., Mays M. J., Raithby P. R., Shields G. P., Tompkin P. K., Dalton Trans. 1997, 715–720. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Davies J. E., Mays M. J., Pook E. J., Chem. Commun. 1997, 1997–1998. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Scherer O. J., Kemény G., Wolmershäuser G., Chem. Ber. 1995, 128, 1145–1148. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Laplaza C. E., Davis W. M., Cummins C. C., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1995, 34, 2042–2044; [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 1995, 107, 2181–2183. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Johnson M. J. A., Odom A. L., Cummins C. C., Chem. Commun. 1997, 1523–1524. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Piro N. A., Cummins C. C., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 9524–9535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tofan D., Cossairt B. M., Cummins C. C., Inorg. Chem. 2011, 50, 12349–12358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Figueroa J. S., Cummins C. C., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 4592–4596; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2005, 117, 4668–4672. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Figueroa J. S., Cummins C. C., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004, 43, 984–988; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2004, 116, 1002–1006. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Figueroa J. S., Cummins C. C., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 13916–13917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Figueroa J. S., Cummins C. C., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 4020–4021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Piro N. A., Figueroa J. S., McKellar J. T., Cummins C. C., Science 2006, 313, 1276–1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Piro N. A., Cummins C. C., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 8764–8765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Umbarkar S., Sekar P., Scheer M., Dalton Trans. 2000, 1135–1137. [Google Scholar]

- 36.

- 36a. Alvarez M. A., García M. E., García-Vivó D., Ramos A., Ruiz M. A., Inorg. Chem. 2011, 50, 2064–2066; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36b. Alvarez M. A., García M. E., García-Vivó D., Ruiz M. A., Vega M. F., Organometallics 2015, 34, 870–878. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Capozzi G., Chiti L., Di Vaira M., Peruzzini M., Stoppioni P., J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1986, 1799–1800. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Barth A., Huttner G., Fritz M., Zsolnai L., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1990, 29, 929–931; [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 1990, 102, 956–958. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Di Vaira M., Stoppioni P., Midollini S., Laschi F., Zanello P., Polyhedron 1991, 10, 2123–2129. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mädl E., Balázs G., Peresypkina E. V., Scheer M., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 7702–7707; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2016, 128, 7833–7838. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Cossairt B. M., Cummins C. C., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 1595–1598; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2010, 122, 1639–1642. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Velian A., Cummins C. C., Chem. Sci. 2012, 3, 1003–1006. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Cossairt B. M., Diawara M.-C., Cummins C. C., Science 2009, 323, 602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Di Vaira M., Frediani P., Costantini S. S., Peruzzini M., Stoppioni P., Dalton Trans. 2005, 2234–2236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.

- 45a. Di Vaira M., Peruzzini M., Seniori Costantini S., Stoppioni P., J. Organomet. Chem. 2006, 691, 3931–3937; [Google Scholar]

- 45b. Caporali M., Gonsalvi L., Kagirov R., Mirabello V., Peruzzini M., Sinyashin O., Stoppioni P., Yakhvarov D., J. Organomet. Chem. 2012, 714, 67–73. [Google Scholar]

- 46. de los Rios I., Hamon J.-R., Hamon P., Lapinte C., Toupet L., Romerosa A., Peruzzini M., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2001, 40, 3910–3912; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2001, 113, 4028–4030. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Barbaro P., Di Vaira M., Peruzzini M., Seniori Costantini S., Stoppioni P., Chem. Eur. J. 2007, 13, 6682–6690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Barbaro P., Di Vaira M., Peruzzini M., Seniori Costantini S., Stoppioni P., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 4425–4427; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2008, 120, 4497–4499. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Barbaro P., Di Vaira M., Peruzzini M., Seniori Costantini S., Stoppioni P., Inorg. Chem. 2009, 48, 1091–1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Barbaro P., Bazzicalupi C., Peruzzini M., Seniori Costantini S., Stoppioni P., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 8628–8631; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2012, 124, 8756–8759. [Google Scholar]

- 51.

- 51a. Krossing I., Raabe I., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2001, 40, 4406–4409; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2001, 113, 4544–4547; [Google Scholar]

- 51b. Krossing I., J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. 2002, 500–512. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Borger J. E., Bakker M. S., Ehlers A. W., Lutz M., Slootweg J. C., Lammertsma K., Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 3284–3287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Scherer O. J., Hilt T., Wolmershäuser G., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2000, 39, 1425–1427; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2000, 112, 1483–1485. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Deng S., Schwarzmaier C., Eichhorn C., Scherer O., Wolmershäuser G., Zabel M., Scheer M., Chem. Commun. 2008, 4064–4066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Scheer M., Deng S., Scherer O. J., Sierka M., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 3755–3758; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2005, 117, 3821–3825. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Pelties S., Ehlers A. W., Wolf R., Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 6601–6604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Schwarzmaier C., Heinl S., Balázs G., Scheer M., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 13116–13121; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2015, 127, 13309–13314. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Borger J. E., Jongkind M. K., Ehlers A. W., Lutz M., Slootweg J. C., Lammertsma K., ChemistryOpen 2017, 6, 350–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Seitz A. E., Eckhardt M., Erlebach A., Peresypkina E. V., Sierka M., Scheer M., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 10433–10436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Vogel U., Eberl M., Eckhardt M., Seitz A., Rummel E.-M., Timoshkin A. Y., Peresypkina E. V., Scheer M., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 8982–8985; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2011, 123, 9144–9148. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Scheer M., Dargatz M., Jones P. G., J. Organomet. Chem. 1993, 447, 259–264. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Cavaillé A., Saffon-Merceron N., Nebra N., Fustier-Boutignon M., Mézailles N., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 1874–1878; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2018, 130, 1892–1896. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Piesch M., Reichl S., Seidl M., Balázs G., Scheer M., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 16563–16568; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2019, 131, 16716–16721. [Google Scholar]

- 64. Piesch M., Seidl M., Scheer M., Chem. Sci. 2020, 11, 6745–6751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Piesch M., Seidl M., Stubenhofer M., Scheer M., Chem. Eur. J. 2019, 25, 6311–6316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Hoidn C. M., Maier T. M., Trabitsch K., Weigand J. J., Wolf R., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 18931–18936; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2019, 131, 19107–19112. [Google Scholar]

- 67. Chakraborty U., Leitl J., Mühldorf B., Bodensteiner M., Pelties S., Wolf R., Dalton Trans. 2018, 47, 3693–3697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Ziegler C. G. P., Maier T. M., Pelties S., Taube C., Hennersdorf F., Ehlers A. W., Weigand J. J., Wolf R., Chem. Sci. 2019, 10, 1302–1308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Mädl E., Butovskii M. V., Balázs G., Peresypkina E. V., Virovets A. V., Seidl M., Scheer M., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 7643–7646; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2014, 126, 7774–7777. [Google Scholar]

- 70. Brake H., Peresypkina E., Virovets A., Piesch M., Kremer W., Zimmermann L., Klimas C., Scheer M., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 16241–16246; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2020, 132, 16377–16383 [Google Scholar]

- 71. Schoo C., Bestgen S., Schmidt M., Konchenko S. N., Scheer M., Roesky P. W., Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 13217–13220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Yadav R., Simler T., Reichl S., Goswami B., Schoo C., Köppe R., Scheer M., Roesky P. W., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 1190–1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Yadav R., Simler T., Goswami B., Schoo C., Köppe R., Dey S., Roesky P. W., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 9443–9447; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2020, 132, 9530–9534. [Google Scholar]

- 74. Cossairt B. M., Cummins C. C., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 169–172; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2008, 120, 175–178. [Google Scholar]

- 75. Cossairt B. M., Cummins C. C., Inorg. Chem. 2008, 47, 9363–9371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Cossairt B. M., Cummins C. C., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 8863–8866; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2008, 120, 8995–8998. [Google Scholar]

- 77.

- 77a. Barton D. H. R., Zhu J., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993, 115, 2071–2072; [Google Scholar]

- 77b. Barton D. H. R., Vonder Embse R. A., Tetrahedron 1998, 54, 12475–12496. [Google Scholar]

- 78. Cossairt B. M., Cummins C. C., New J. Chem. 2010, 34, 1533–1536. [Google Scholar]

- 79. Heinl S., Reisinger S., Schwarzmaier C., Bodensteiner M., Scheer M., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 7639–7642; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2014, 126, 7769–7773. [Google Scholar]

- 80.

- 80a. Budnikova Y. G., Tazeev D. I., Kafiyatullina A. G., Yakhvarov D. G., Morozov V. I., Gusarova N. K., Trofimov B. A., Sinyashin O. G., Russ. Chem. Bull. 2005, 54, 942–947; [Google Scholar]

- 80b. Budnikova Y. G., Yakhvarov D. G., Kargin Y. M., Mendeleev Commun. 1997, 7, 67–68. [Google Scholar]

- 81. Yakhvarov D. G., Budnikova Y. G., Sinyashin O. G., Russ. J. Electrochem. 2003, 39, 1261–1270. [Google Scholar]

- 82.