Abstract

Barth syndrome (BTHS) is a rare X‐linked genetic disorder caused by mutations in the gene encoding the transacylase tafazzin and characterized by loss of cardiolipin and severe cardiomyopathy. Mitochondrial oxidants have been implicated in the cardiomyopathy in BTHS. Eleven mitochondrial sites produce superoxide/hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) at significant rates. Which of these sites generate oxidants at excessive rates in BTHS is unknown. Here, we measured the maximum capacity of superoxide/H2O2 production from each site and the ex vivo rate of superoxide/H2O2 production in the heart and skeletal muscle mitochondria of the tafazzin knockdown mice (tazkd) from 3 to 12 months of age. Despite reduced oxidative capacity, superoxide/H2O2 production was indistinguishable between tazkd mice and wild‐type littermates. These observations raise questions about the involvement of mitochondrial oxidants in BTHS pathology.

Keywords: Barth syndrome, cardiomyopathy, ‘ex vivo’ rate of superoxide/H2O2 production, mitochondria, mitochondrial reactive oxygen species, superoxide/H2O2, tafazzin, tazkd mice

Abbreviations

BTHS, Barth syndrome

CL, cardiolipin

EE, energy expenditure

Eh, operating redox potential

H2O2, hydrogen peroxide

MLCL, monolysocardiolipin

QH2, ubiquinol

RER, respiratory exchange ration

ROS, reactive oxygen species

S1QEL, suppressor of site IQ electron leak

S3QEL, suppressor of site IIIQo electron leak

site AF , flavin in 2‐oxoadipate dehydrogenase

site BF, flavin in the branched‐chain 2‐oxoacid (or α‐ketoacid) dehydrogenase complex

site DQ, quinone reducing site in dihydroorotate dehydrogenase Q, ubiquinone

site EF, site in the electron transferring flavoprotein/ETF:ubiquinone oxidoreductase (ETF:QOR), probably the flavin of ETF

site GQ, quinone reducing site in mitochondrial glycerol 3‐phosphate dehydrogenase, mGPDH

site IF, flavin in the NADH‐oxidizing site of respiratory complex I

site IIF, flavin site of respiratory complex II

site IIIQo, outer quinol‐oxidizing site of respiratory complex III

site IQ, ubiquinone‐reducing site of respiratory complex I

site OF, flavin in the 2‐oxoglutarate dehydrogenase complex

site PF, flavin in the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex

Tazkd, tafazzin knockdown

Cardiolipin (CL) is a unique phospholipid; it contains four acyl chains and is exclusively synthetized and found in the mitochondrial membranes [1]. CL interacts with a myriad of mitochondrial proteins, and this interaction is critical for their function [2, 3]. A critical step in CL synthesis and maturation is the remodeling of its acyl chains to a highly symmetric and unsaturated profile [3, 4]. CL remodeling consists in removing a fatty acyl chain from the nascent molecule, generating a monolysocardiolipin (MLCL), which is further re‐acylated by the transacylase, tafazzin (taz) [5] (Fig. 1). In the heart and skeletal muscle, taz‐mediated CL remodeling generates tetralinoleoyl CL (L4CL) molecules [4]. Upon loss of taz, the MLCL/CL ratio is dramatically increased [6, 7]. Mutations in the taz gene cause a rare X‐linked autosomal recessive disease, named after P. Barth who first described the syndrome in 1981 [8]. In humans, Barth syndrome (BTHS) has an early onset, affecting mostly infant male individuals and is characterized by cardiomyopathy, skeletal myopathy, neutropenia, high levels of 3‐methylglutaconic acid in the urine, and growth delay [3, 8, 9]. Nearly a decade ago, the first mouse model expressing an inducible short‐hairpin RNA to promote taz knockdown (tazkd) became available [6, 10]. Tazkd mice recapitulate many aspects of the disease in humans; however, the symptoms in the murine model are characterized by a much later onset where cardiomyopathy becomes evident at 8 months [6, 11].

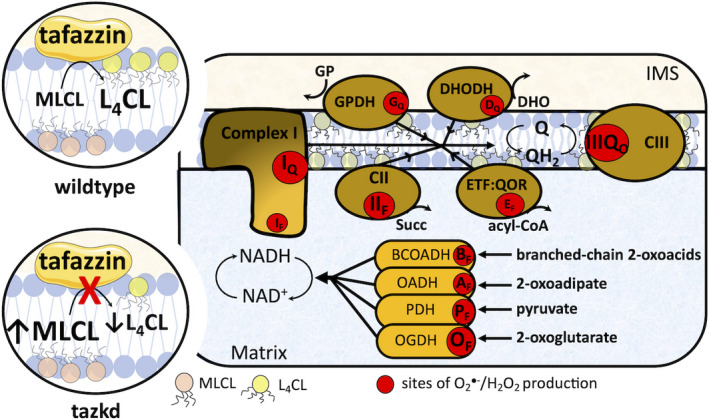

Fig. 1.

Tafazzin deficiency and the sites of superoxide/H2O2 in the mitochondria. Tafazzin is an acyltransferase important for remodeling CL to its physiologically relevant form, tetralinoleoyl CL (L4CL) (circle on top left, wild‐type). Mutations in the tafazzin gene alter the CL profile in the mitochondria and increase the levels of the intermediate, MLCL (circle on bottom left, tazkd). CL tightly interacts with and stabilize components of the electron transport chain (ETC), and aberrant CL profile is associated with higher mitochondrial superoxide () and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) production. There are 11 sites with the capacity to produce /H2O2 in mitochondria. These sites are associated with the ETC and substrate oxidation enzymes and are represented by red circles. Reduced substrates from metabolism are transported into the mitochondria where they are oxidized; the electrons enter the ETC via enzymes that operate in close proximity to the NADH/NAD+redox potential and enzymes that operate in close proximity to the QH2/Q redox potential. The electrons flow from the NADH‐ and Q‐pool to complex III then to cytochromecand to complex IV, which finally transfers four electrons to oxygen, producing water. The sites associated with the enzymes in the NADH isopotential group and able to generate/H2O2 are the flavin/lipoate of the dehydrogenases of branched‐chain 2‐oxoacids (BCOADH, BF), 2‐oxoadipate (OADH, AF), pyruvate (PDH, PF), 2‐oxoglutarate (OGDH, OF), and the flavin site of complex I (IF). The sites in the Q isopotential group are the flavin site of complex II (IIF) and the electron transfer flavoprotein (ETF) and ETF:ubiquinone oxidoreductase (ETF:QOR) system (EF) and the ubiquinone binding sites of dehydrogenases of glycerol phosphate (GPDH, GF) and dihydroorotate (DHODH, DQ) and the outer quinol site of complex III, IIIQo. Electrons are transferred from the NADH‐ to the Q‐poolviasite IQin complex I, which has a high capacity for/H2O2 production. The diameters of the red circles are roughly proportional to their mean capacity for/H2O2 generation in heart and skeletal muscle. IMS, intermembrane space; CII, complex II; CIII, complex III.

The abnormal CL profile due to the loss of taz is associated with mitochondrial dysfunction [3, 9, 10]. In particular, mitochondrial production of reactive oxygen species (ROS)—from here referred to as superoxide and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2)—is considered a key process in the pathogenesis of BTHS [3, 9, 12].

Mitochondrial superoxide/H2O2 generation is not a single process; there are at least 11 sites in the respiratory chain and in different enzymes of substrate oxidation (β‐oxidation, tricarboxylic acid cycle, and pyrimidine biosynthesis) that are able to generate significant amounts of these molecules (Fig. 1). Each site has its own properties and maximum capacity to produce superoxide/H2O2 [13]. The sites are represented in Fig. 1 as red circles and can be didactically separated into two groups based on the redox potential (E h) of their redox centers. The sites that operate close to the redox potential of NADH/NAD+ (E h~ −280 mV) are the sites in the dehydrogenase complexes of branched‐chain 2‐oxoacids, 2‐oxoadipate, pyruvate, and 2‐oxoglutarate, sites BF, AF, PF, and OF, respectively, and site IF in complex I. These sites belong to the same isopotential group [14, 15, 16]. The remaining sites, IIF in complex II, EF in ETF:QOR, GQ and DQ in mitochondrial glycerol 3‐phosphate and dihydroorotate dehydrogenase, respectively, and IIIQo in complex III, belong to the ubiquinone isopotential group (QH2/Q, E h ~ +20 mV) [14, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21].

The rate of superoxide/H2O2 production and the contribution from each site heavily depend on the substrates being oxidized [22]. For example, in skeletal muscle the rate of superoxide/H2O2 production during the oxidation of succinate is 5‐fold faster than the rate during the oxidation of glutamate plus malate. In addition, the sites engaged during the oxidation of succinate or glutamate plus malate are different. While site IQ is the predominant source of superoxide/H2O2 when succinate is used as substrate, sites IF, IIIQo and OF contribute about equally to the rate measured during oxidation of glutamate plus malate [22]. There is no a priori reason to expect that all sites are equally engaged in superoxide/H2O2 production in any given context.

In vivo or in intact cells, mitochondria metabolize multiple substrates simultaneously, which implies that superoxide/H2O2 is generated from multiple sites simultaneously. In addition, metabolic effectors, for example, calcium, ADP, or cytosolic pH, which modulate the rate of superoxide/H2O2 production, vary according to the physiological or pathological context [23, 24, 25]. Therefore, it is challenging to study site‐specific superoxide/H2O2 generation in intact cells or in vivo. Instead, the rate at maximum capacity in isolated mitochondria is widely measured and is often used as a proxy estimation for the generation of these oxidant molecules in vivo. However, the maximum capacity cannot be used to predict the rate of superoxide/H2O2 production in vivo or intact cells [22, 26]. To overcome these difficulties, ‘ex vivo’ media were carefully designed to mimic the cytosol of skeletal muscle at ‘rest’ and during ‘exercise’. These media contained the physiological cytosolic concentrations of all substrates and effectors thought to be relevant to oxidative phosphorylation and superoxide/H2O2 production, allowing more realistic predictions of the rate of superoxide/H2O2 production from ex vivo experiments to in vivo conditions [26].

Due to the fact that different groups have reported higher production rates of mitochondrial oxidants in heart and skeletal muscle in BTHS [7, 35], together with the encouraging effects of some antioxidants, especially mitoTEMPO and linoleic acid [12, 35] for improving cardiomyopathy pathogenesis, mitochondrial superoxide/H2O2 production is considered a key target for therapeutic interventions [3, 11, 12]. However, the precise site(s) responsible for the abnormal production of mitochondrial oxidants in different tissues in BTHS are still unknown.

In the present study we isolated heart and skeletal muscle mitochondria from tazkd mice and systematically measured the maximum capacities of superoxide/H2O2 production from all 11 sites (Fig. 1) during the progression of BTSH disease. We took advantage of the late onset of the disease in the mouse model to study the kinetics of superoxide/H2O2 generation in presymptomatic 3‐month‐old mice and at later time points where cardiomyopathy and skeletal myopathology are already established (7‐ and 12‐month‐old mice). Unexpectedly, our results indicate that there is no difference in the rate of superoxide/H2O2 production between tazkd mice and their wild‐type littermates in heart or skeletal muscle mitochondria during the course of the disease progression.

To estimate the production rate of mitochondrial oxidants in vivo in these tissues, superoxide/H2O2 was measured ‘ex vivo’ in media designed to mimic the cytosol of skeletal muscle [26] and heart. Strikingly, ‘ex vivo’ rates of superoxide/H2O2 production were not altered in tazkd mice in mitochondria from either tissue despite the consistent decrease in oxygen consumption and in vivo exercise intolerance. In this study, we provide a broad and systematic characterization of the maximum capacities of sites of superoxide/H2O2 production in heart and muscle mitochondria from tazkd mice during the progression of BTHS. Our data suggest that (a) the involvement of mitochondrial superoxide/H2O2 production in BTHS pathogenesis should be interpreted carefully and (b) in tazkd mice, cardiac and muscle pathologies may not be related to the production of mitochondrial oxidants.

Experimental procedures

Animals, mitochondria, and reagents

All animal procedures presented here were approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Harvard University. Mice were kept on 12‐h light/12‐h dark cycle in the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health pathogen‐free barrier facility. Tafazzin knockdown (Tazkd) male mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA; B6.Cg‐Gt(ROSA)26Sortm37(H1/tetO‐RNAi:Taz)Arte/ZkhuJ, stock #014648) and crossed with C57BL/6NJ females. Pregnant females were provided with 625 mg·kg−1 doxycycline‐containing chow (C13510i; Research Diets, New Brunswick, NJ, USA) to induce tafazzin silencing in the pups during early development. After weaning, wild‐type and heterozygous male mice were kept on doxycycline chow for the remainder of the study. All mice were checked to be negative for nicotinamide nucleotide transhydrogenase (nnt). Skeletal muscle mitochondria were isolated from hind limb of wild‐type and tazkd mice and dissected at 4 ºC in Chappell‐Perry buffer (CP1‐ 0.1 m KCl, 50 mm Tris, 2 mm EGTA, pH 7.4 and CP2‐ CP1 supplemented with 0.5 % w/v fatty acid‐free BSA, 2 mm MgCl2, 1 mm ATP and 250 U·0.1 ml−1 subtilisin protease type VIII, pH 7.4) as described by [36]. Heart mitochondria were isolated from wild‐type and Tazkd mice. Mice were euthanized by cervical dislocation and the heart was immediately excised, excess blood was removed, and the heart was placed in ice‐cold buffer B [0.25 m sucrose, 10 mm HEPES (pH 7.2) and 5 mm EGTA]. After few seconds to allow the remaining blood to decant, the heart was rapidly diced into very small pieces and the suspension was poured into a 30 mL ice‐jacket Potter‐Elvehjem with motorized Teflon pestle and 10–15 mL buffer A (buffer B supplemented with 0.5 % w/v fatty acid‐free BSA) was added. After 6–10 strokes the homogenate was transferred to an ice‐cold 50 mL centrifuge tube and spun at 500 g for 5 min. The supernatant was transferred to a clean tube and spun at 10 000 g for 10 min. Now, the supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was carefully resuspended in 0.5 mL buffer B. And then, 20 mL buffer B was added followed by a quick centrifugation at 1000 g for 3 min. The supernatant was transferred to a fresh tube and centrifuged at 10 000 g for 10 min. The pellet was resuspended in 200 µL of buffer B and protein concentration was determined using bicinchoninic acid assay.

Western blot analysis

To determine tafazzin levels, 10 µg samples of skeletal muscle and heart isolated mitochondrial protein were boiled in Laemmli loading buffer under reducing conditions. Proteins were separated by 4–12% NU‐PAGE gradient gel using 1× MOPS buffer (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA) and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. Anti‐tafazzin (1 : 1000 dilution) was a kind gift from S.M. Claypool [37] and recognizes a band around 26 kDa. A nonspecific band was also recognized but was higher than 30 kDa, incompatible with tafazzin molecular weight. To determine the levels of catalase (Cell Signaling, Beverly, MA, USA, #12980), manganese superoxide dismutase (Santa Cruz, Dallas, TX, USA, sc‐133254) peroxiredoxin 2 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA, ab109367) and peroxiredoxin 3 (Abcam, ab73349), 10 µg of skeletal muscle and heart protein homogenates were prepared as described above. Proteins were separated using 4–20% Criterion™ TGX Stain‐Free™ gels (Bio‐Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). To determine the dimerization of peroxiredoxins, skeletal muscle and heart tissues were homogenized in KHE medium (120 mm KCl, 5 mm HEPES, 1 mm EGTA) supplemented with 100 mm N‐ethylmaleimide to alkylate the free cysteines and separated by non‐reducing SDS/PAGE [38]. VDAC (Abcam, ab14734) was used as loading control. Chemiluminescence was generated with SuperSignal West Pico (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and quantified with image j software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Mitochondrial oxygen consumption and superoxide/H2O2 production

Oxygen consumption rate (OCR) of freshly isolated heart and skeletal muscle mitochondria was monitored using an XF‐24 extracellular flux analyzer (Seahorse Bioscience; Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Briefly, 2 µg of mitochondrial protein was plated per well in KHE medium supplemented with 0.3% w/v fatty acid‐free BSA, 1 mm MgCl2, 5 mm KH2PO4. Baseline rates with 1 mm ADP were measured for 15 min and 5 mm succinate + 4 µm rotenone were injected from port A. OCR at state 3 was monitored for 9 min and 1 µg·mL−1 oligomycin was injected from port B to induce mitochondrial state 4.

Rates of superoxide/H2O2 production were collectively measured as rates of H2O2 generation, as two superoxide molecules are dismutated by mitochondrial or exogenous superoxide dismutase to yield one H2O2. The maximum capacities for superoxide/H2O2 production from the 11 sites were detected fluorometrically in a 96‐well plate using specific combinations of inhibitors and substrates (see below) in the presence of 5 U·mL−1 horseradish peroxidase, 25 U·mL−1 superoxide dismutase and 50 µm Amplex UltraRed [39]. Heart and skeletal muscle mitochondria (0.1 mg protein·mL−1) were incubated in KHE medium supplemented with 0.3% w/v fatty acid‐free BSA, 1 mm MgCl2, 5 mm KH2PO4, 1 µg·mL−1 oligomycin. Changes in fluorescence signal (Ex 604/Em 640) were monitored for 15 min. using a microplate reader (Molecular Devices [San Jose, CA, USA] SpectraMax Paradigm) and calibrated with known amounts of H2O2 at the end of each run in the presence of all inhibitors and effectors [39]. The sites linked to the NADH/NAD+ isopotential pool were measured in the presence of 4 µm rotenone: Site IF: 5 mm malate, 2.5 mm ATP and 5 mm aspartate; flavin in 2‐oxoadipate dehydrogenase (site AF): 10 mm 2‐oxoadipic acid; BF: 20 mm KMV (3‐methyl‐ 2‐oxopentanoate/alpha‐keto‐methylvalerate); PF: 2.5 mm pyruvate and 5 mm carnitine; OF: 2.5 mm 2‐oxoglutarate and 2.5 mm ADP. Site IQ was measured as the rotenone‐sensitive rate in the presence of 5 mm succinate. The remaining sites were linked to the ubiquinone isopotential pool: Site IIIQo was measured as the myxothiazol‐sensitive rate in the presence of 5 mm succinate, 5 mm malonate, 4 µm rotenone and 2 µm antimycin A. Site IIF was measured as the 1mM malonate‐sensitive rate in the presence of 0.2 mm succinate and 2 µm myxothiazol. Site GQ: 10 mm glycerol‐3‐phosphate, 4 µm rotenone, 2 µm myxothiazol, 2 µm antimycin A and 1 mm malonate; Site DQ: 3.5 mm dihydroorotate, 4 µm rotenone, 2 µm myxothiazol, 2 µm antimycin A and 1 mm malonate; Site EF: 15 µm palmitoylcarnitine, 2 mm carnitine, 5 µm FCCP, 1 mm malonate, 2 µm myxothiazol.

For the measurement of the rate of H2O2 production under native conditions ex vivo, skeletal muscle and heart mitochondria (0.1 mg of protein·mL−1) from 12‐month‐old wild‐type and tazkd mice were incubated at 37 °C for 4–5 min in the appropriate ‘basic medium’ mimicking the cytosol of skeletal muscle or heart during rest, respectively, (basic ‘rest’ medium plus 1 µg·mL−1 oligomycin) and then added to a black 96 well plate containing the complex substrate mix. Changes in fluorescence signal (Ex 604/Em 640) were monitored for 15 min. using a microplate reader (Molecular Devices SpectraMax Paradigm) and calibrated with known amounts of H2O2 at the end of each run in the presence of all substrates.

Skeletal muscle basic medium

Forty millimolar taurine, 3 mm KH2PO4, 3.16 mm NaCl, 52.85 mm KCl, 5.46 mm MgCl2 (targeted free Mg2+ concentration 600 μm), 0.214 mm CaCl2 (targeted Ca2+ concentration 0.05 μm), 10 mm HEPES, 1 mm EGTA, 0.3 % w/v fatty acid‐free BSA, 1 μg·mL−1 oligomycin, pH 7.1. Targeted Na+ concentration was 16 mm and total K+ concentration was 80 mm. The medium had K+ and Cl‐ adjusted to give an osmolarity of 290 mosM. Total Mg2+ and Ca2+ concentrations to give the targeted free values were calculated using the software maxchelator (https://somapp.ucdmc.ucdavis.edu/pharmacology/bers/maxchelator/CaMgATPEGTA‐NIST‐Plot.htm) [26].

Skeletal muscle complex substrate mix

Hundred micro molar acetoacetate, 300 μm 3‐hydroxybutyrate, 2500 μm alanine, 500 μm arginine, 1500 μm aspartate, 1500 μm glutamate, 6000 μm glutamine, 7000 μm glycine, 150 μm isoleucine, 200 μm leucine, 1250 μm lysine, 2000 μm serine, 300 μm valine, 100 μm citrate, 200 μm malate, 30 μm 2‐oxoglutarate, 100 μm pyruvate, 200 μm succinate, 100 μm glycerol‐3‐phosphate, 50 μm dihydroxyacetone phosphate, 1000 μm carnitine, 500 μm acetylcarnitine, 10 μm palmitoylcarnitine, and 6000 μm ATP [26].

Heart basic medium

Seventy millimolar taurine, 6 mm KH2PO4, 6 mm NaCl, 12.8 mm KCl, 9.2 mm MgCl2 (targeted free Mg2+ concentration 1200 μm), 0.42 mm CaCl2 (targeted Ca2+ concentration 0.1 μm), 10 mm HEPES, 1 mm EGTA, 0.3 % w/v fatty acid‐free BSA, 1 μg·mL−1 oligomycin, pH 7.1. Targeted Na+ concentration was 18 mm and total K+ concentration was 55.5 mm. The medium had K+ and Cl‐ adjusted to give an osmolarity of 284 mosM. Total Mg2+ and Ca2+ concentrations to give the targeted free values were calculated using the software maxchelator.

Heart complex substrate mix

Ffity micromolar 50 μm 3‐hydroxybutyrate, 2000 μm alanine, 400 μm arginine, 4500 μm aspartate, 5000 μm glutamate, 8000 μm glutamine, 1000 μm glycine, 80 μm isoleucine, 130 μm leucine, 800 μm lysine, 350 µm proline, 1000 μm serine, 150 μm valine, 100 μm citrate, 150 μm malate, 50 μm 2‐oxoglutarate, 130 μm pyruvate, 135 μm succinate, 400 μm glycerol‐3‐phosphate, 40 μm dihydroxyacetone phosphate, 1700 μm carnitine, 80 μm acetylcarnitine, 5 μm palmitoylcarnitine and 9000 μm ATP (Table S1).

Isolation and quantification of cardiolipin (CL) and monolysocardiolipin (MLC L)

Lipids were extracted from isolated heart and skeletal muscle mitochondria using methanol chloroform (2 : 1). Isolation and quantification of CL and MLCL were performed according to [40].

Body composition, Comprehensive Lab Animal Monitoring System (CLAMS) and exercise challenge

Body composition from wild‐type and Tazkd mice at 3 and 6 months of age was measured with dual‐energy x‐ray absorptiometry (DEXA Lunar PIXImus; GE, Madison, WI, USA). Animals were anesthetized with 100 mg·kg−1 ketamine and 10 mg·kg−1 xylazine. For CLAMS, mice were housed individually and acclimatized for 1 day. Oxygen consumption, carbon dioxide release, energy expenditure (EE) and activity were measured using a Columbus Instruments Oxymax‐CLAMS system according to guidelines for measuring energy metabolism in mice [41, 42].

Mice were physically challenged on a lidded motorized treadmill (Columbus Instrument, Columbus, OH, USA), which had adjustable speed and inclination and electric shock stimulation grid. The stimulus intensity was set to 1 mA. Mice were acclimatized in the treadmill for 3 days before the test. Acclimation protocol: 5 m·min−1 for 5 min, followed by 1 m·min−1 increment in speed every min until 10 min. Mice were allowed to rest for 5 min and then run for 10 min at 10 m·min−1. On the test day, wild‐type and tazkd mice were placed in the treadmill and the test started with the mice running for 5 min at 5 m·min−1; then, the speed was increased 1 m·min−1 every min up to 20 min. Exhaustion was achieved when a mouse stayed more than 10 s on the stimulus grid or touched the grid more than 10 consecutive times.

Statistics

Data are presented as mean ± SEM of n independent values. Student's t‐test was used to calculate statistical significance when two groups were compared (Figs 2, 3 and 6). For multiple comparison tests where age, genotype, and sites of superoxide/hydrogen peroxide production were analyzed, 2‐way ANOVA followed by Sidak's hoc test was used and when appropriate Bonferroni correction was applied. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant (graphpad prism, San Diego, CA, USA).

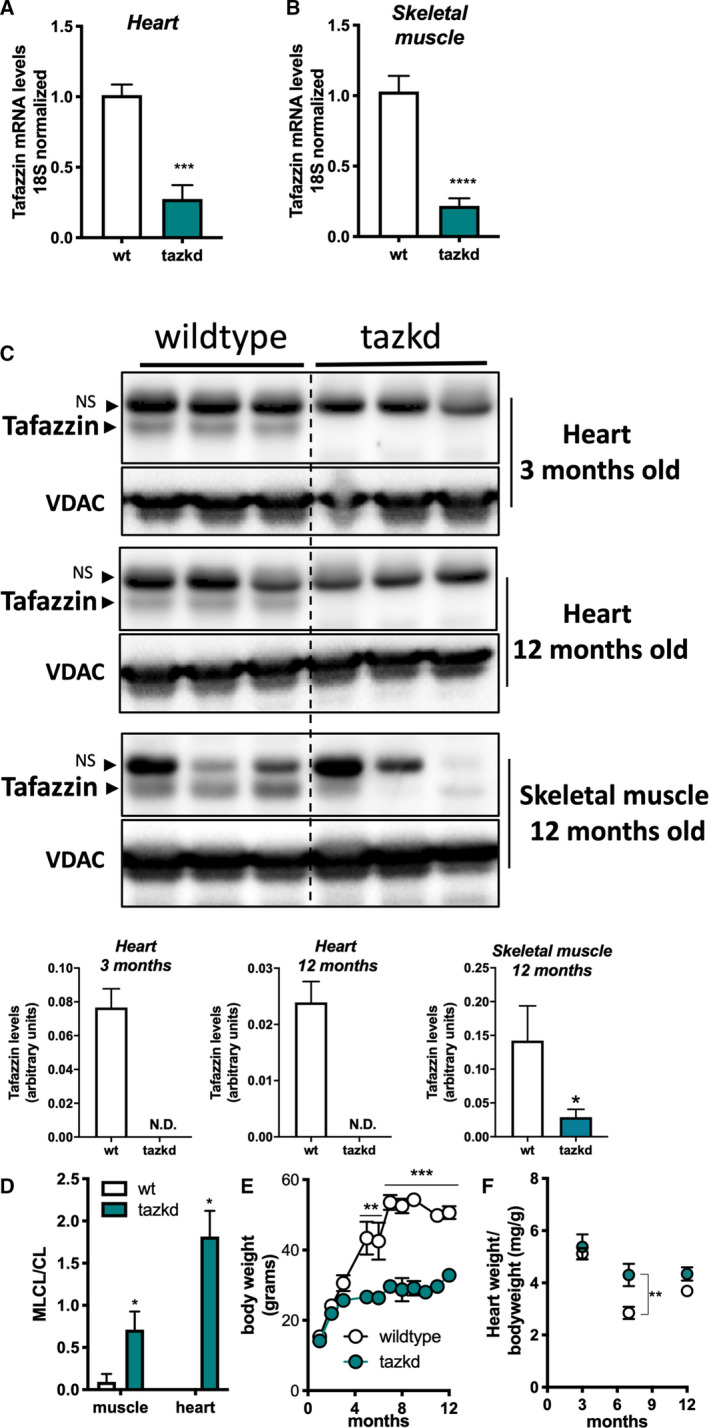

Fig. 2.

Tazkd results in altered CL levels and protects from weight gain. (A) Tafazzin mRNA levels in the heart and (B) in the skeletal muscle of wild‐type and Tazkd mice. (C) Upper, western blot of tafazzin protein in heart extracts of 3‐ and 12‐month‐old wild‐type and tazkd mice and in skeletal muscle extracts of 12‐month‐old wild‐type and Tazkd mice probed with anti‐tafazzin antibodies [36]. VDAC was used as a loading control. Bottom, densitometric analysis of western blots from the upper panel C, tafazzin levels were normalized by VDAC levels, NS, nonspecific band. (D) MLCL and CL levels were determined by high‐performance liquid chromatography in heart and skeletal muscle isolated mitochondria from wild‐type and tazkd mice; an elevated ratio of MLC L/CL indicates a defect in CL remodeling. (E) Body weights of wild‐type and tazkd mice. (F) Heart weight normalized by total body weight. Values are mean ± SEM,n ≧ 3. *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001; ****P< 0.0001, using Student's t‐test. **, 2‐way ANOVA, Sidak's post‐test.

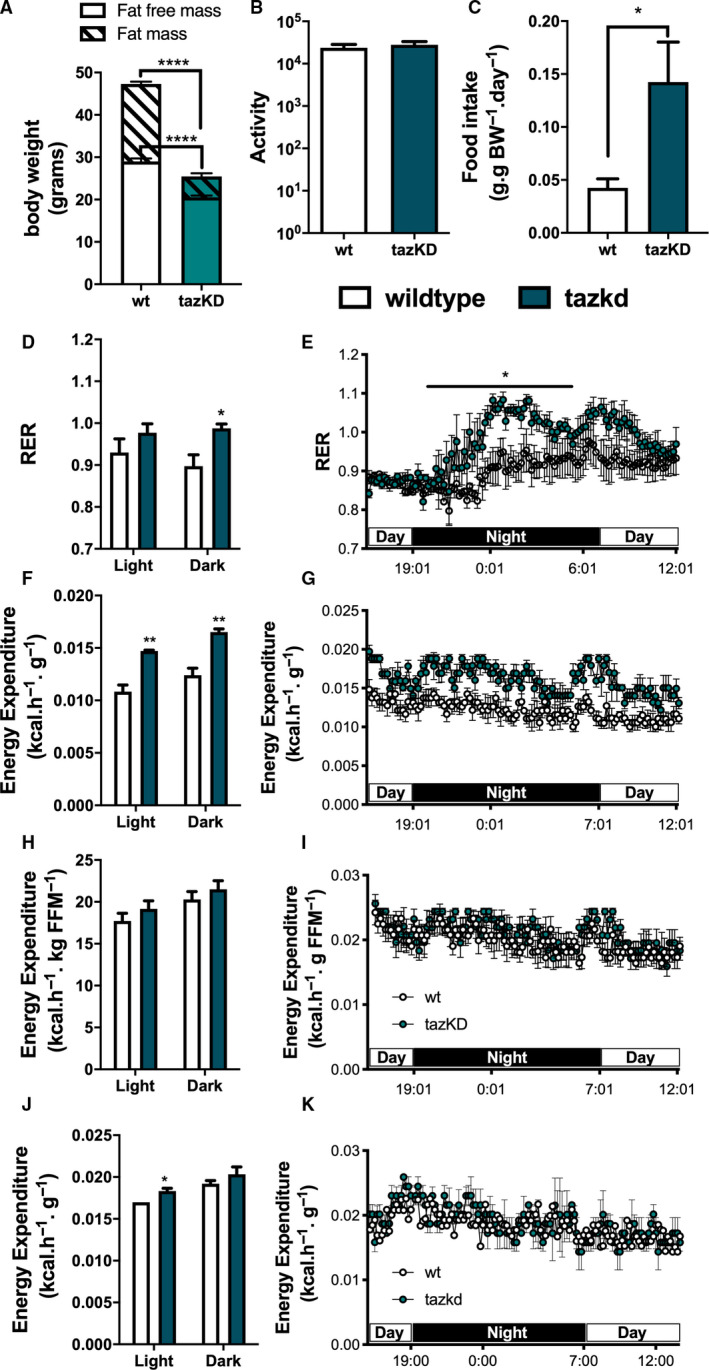

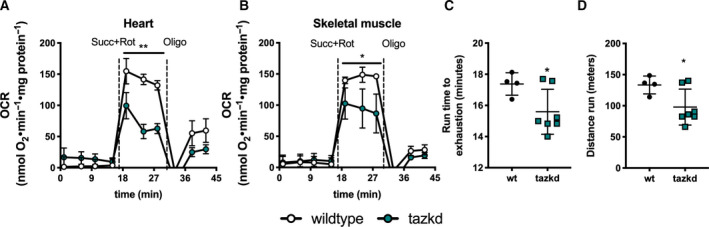

Fig. 3.

Metabolic profile of tazkd mice. (A) body weight, fat mass, and fat‐free mass of 7‐month‐old wild‐type and tazkd mice. (B) activity, measured by the number of beam breaks in the cage. (C) food intake normalized by body weight. (D and E), histogram and representative plot of RER of wild‐type and tazkd mice over a period of 24 h. (F and G) histogram and representative plot of EE (normalized by body weight) of wild‐type and tazkd mice at 6 months of age over a period of 24 h. (H and I) replot from F and G normalized by fat‐free mass. (J and K) histogram and representative plot of EE (normalized by whole body weight) of wild‐type and tazkd mice at 3 months of age over a period of 24 h. Dark and light cycles are shown. Values are mean ± SEM, n = 4. *P < 0.05;**P< 0.01, using Student's t‐test. ****P < 0.0001, 2‐way ANOVA, Sidak's post‐test.

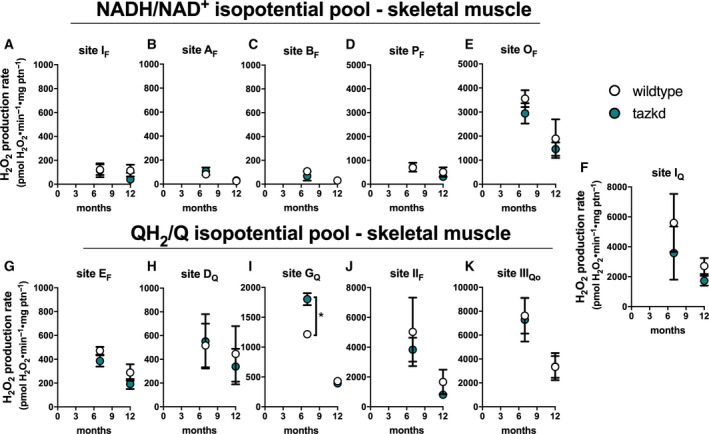

Fig. 6.

Maximum rate of sites generating superoxide/hydrogen peroxide in isolated skeletal muscle mitochondria from wild‐type and tazkd mice at 3, 8, and 12 months of age. The rate of superoxide/hydrogen peroxide generated by sites associated with the NADH/NAD+(A‐E) and QH2/Q (G‐H) isopotential pools. In the NADH/NAD+isopotential pool, the rate of superoxide/H2O2production was measured from the flavin (F) binding sites of: (A) complex I (site IF), (B) site AF, (C) site BF, (D) pyruvate dehydrogenase (site PF), and (E) 2‐oxoglutarate dehydrogenase (site OF). Complex I produces superoxide/H2O2from two sites: (A) site IFand (F) site IQ(ubiquinone (Q) binding site). In sites associated with the QH2/Q isopotential pool, the rate of superoxide/hydrogen peroxide production was measured from (G) site EF, in the electron transfer flavoprotein (ETF) and ETF:ubiquinone oxidoreductase (ETF:QOR) system, (H) site DQ, in dihydroorotate dehydrogenase, (I) site GQ(glycerol 3‐phosphate dehydrogenase), (J) site IIF, in complex II, and (K) site IIIQo, in complex III. Values are mean ± SEM, n ≧ 3 independent mitochondrial preparations and were normalized by mitochondrial protein (ptn). *P < 0.001, 2‐way ANOVA.

Results

Tafazzin deficiency, cardiolipin levels, and metabolic characteristics

The tazkd mouse was the first animal model created to study how loss of tafazzin induces BTHS cardiomyopathy [6, 10]. In this model, an shRNA expression system under the control of doxycycline decreases tafazzin mRNA and protein levels [6, 10]. In our experiments, transgenic male mice (B6.Cg‐Gt(ROSA)26Sortm37(H1/tetO‐RNAi:Taz)Arte/ZkhuJ) were crossed with wild‐type females and kept on standard chow diet containing doxycycline. Tazkd was induced prenatally and male littermates (wild‐type and tazkd) were kept on doxycycline‐containing rodent chow throughout the experiment. Fig. 2A,B show that tafazzin mRNA levels in the tazkd mice were < 30% of their wild‐type littermates in both heart and skeletal muscle. The decreased tafazzin mRNA levels were accompanied by a more dramatic decrease in tafazzin protein levels, reaching undetectable levels in the heart as early as 3 months of age and up to 1 year old (Fig. 2C, heart). In the tazkd mice skeletal muscle tafazzin protein levels were < 15% of wild‐type mice (Fig. 2C, skeletal muscle 12 months old). To confirm that lower tafazzin levels resulted in altered CL remodeling, which is a characteristic of heart and skeletal muscle from BTHS patients, we measured the content of CL and MLCL. In tazkd mice, MLCL accumulated in both tissues, which resulted in significant increases in the MLCL/CL ratio (Fig. 2D) [6].

Consistent with previous reports, wild‐type mice on doxycycline chow gained significantly more weight than their tazkd littermates (Fig. 2E) [30, 33]. Tazkd fat (FM) and fat‐free/lean (FFM) mass were ~ 3.5‐ and 1.4‐fold lower than wild‐type mice, respectively (Fig. 3A). We used indirect calorimetry to better understand whether differences in food intake or EE were responsible for the alteration in bodyweight and composition between wild‐type and tazkd mice 6–7 months of age. There was no difference in locomotor activity (Fig. 3B). Food intake was higher in tazkd than wild‐type mice (Fig. 3C), which was paralleled with a higher respiratory exchange ratio (RER) in tazkd mice (Fig. 3D,E). The RER is the ratio between the volume of CO2 produced to the volume of O2 consumed (VCO2/VO2) and indicates the metabolic substrate preferentially oxidized by the mouse. With an RER closer to 1.0 tazkd mice may oxidize exclusively carbohydrates in contrast to wild‐type mice, which may have more substrate oxidation flexibility (RER = 0.9). EE was also significantly higher in tazkd mice when normalized by total body weight (Fig. 3F,G). However, when EE was normalized by the metabolically active lean mass instead, the difference was no longer observed (Fig. 3H,I). These results indicate that the differences in EE between 6 and 7 months old wild‐type and tazkd are mostly explained by the differences in body weight rather than differences in genotype. However, it is possible that tazkd have slightly higher EE, as we found that at 3 months of age, when body weight was not yet different, EE was already higher in tazkd mice compared to wild‐type controls (Fig. 3J,K), which is also in line with previous reports [30]. As previously reported [33], heart weight normalized by body weight was 34% higher in tazkd mice at 7 months of age, since heart weight per se does not change, this result is driven exclusively due to bodyweight differences (Fig. 2F).

Tafazzin‐deficiency impairs mitochondrial function and endurance capacity

Mitochondrial dysfunction, exercise intolerance, and decreased muscle strength and contractility are some of the hallmarks of cardioskeletal myopathy in BTHS [6, 10, 43, 44]. Since CL interacts with every component of the electron transport chain, it is not surprising that in tazkd mice substrate oxidation and ATP synthesis are compromised [9, 45, 46].

Due to the late onset of the disease in this mouse model [6] and previous reports that at early age mitochondrial oxygen consumption in cardiac mitochondria is not altered [47], we isolated mitochondria from 12‐month‐old mice. As shown in Fig. 4A,B, loss of mature CL in tazkd mice resulted in lower ADP‐stimulated oxygen consumption in heart and skeletal muscle isolated mitochondria oxidizing succinate + rotenone as substrate. Powers et al. [43], previously reported that 4‐ to 5‐month‐old tazkd and their wild‐type littermates can run for about 36 min to a total of 507.4 m. When we challenged 12‐month‐old tazkd and wild‐type mice in a treadmill, exercise endurance, as measured by running time and distance run, was significantly lower in tazkd mice (Fig. 4C,D). Although, the endurance difference between the genotypes was small, at 1 year of age wild‐type mice were obese and weighed 1.6‐fold more than tazkd mice (51 ± 0.9 g, n = 11 vs 32.5 ± 0.9 g, n = 17; P < 0.0001). Considering that the endurance of obese mice is 5–6‐fold lower than their lean littermates [48], the results from Fig. 4C,D stress the high degree of exercise intolerance of tazkd mice.

Fig. 4.

Mitochondrial OCR and animal endurance capacity in 12‐month‐old tazkd mice. (A) OCRs of mitochondria isolated from heart and (B) skeletal muscle oxidizing 5 mm succinate in the presence of 4 µm rotenone. Basal rates were measured in the presence of 1 mm ADP. (C) Duration and (D) distance run by 12‐month‐old wild‐type and tazkd mice until exhaustion. Values are mean ± SEM,n ≧ 3. *P < 0.05;**P < 0.01, using Student's t‐test.

Maximum capacities of the eleven sites of superoxide/H2O2 production

Loss of CL in BTHS is associated with increased production of mitochondrial oxidants [7, 35], which have been considered to have a causative role in the development of cardiomyopathy [12, 34, 35]. However, other reports have failed to find differences in mitochondrial oxidant production in cardiac tissue of tazkd mice [47, 49]. There are 11 sites associated with the electron transport chain and tricarboxylic acid cycle that are known to produce superoxide/H2O2 at significant rates. Their maximum capacities and native uninhibited rates of superoxide/H2O2 have been systematically characterized in rat skeletal muscle mitochondria [13, 26]. Complex I and complex III are often credited as the main source of mitochondrial oxidants [50, 51, 52]. Indeed, complex I‐III activity is decreased in tazkd cardiac mitochondria [43, 44, 49], however, whether this reflects higher superoxide/H2O2 production from these sites or other adjacent sites in tazkd mice is not yet known. We hypothesized that mitochondrial superoxide/ H2O2 generation would be higher in tazkd mice cardiac and skeletal muscle mitochondria and our objective was to identify the site(s) that produced excess oxidants.

Cardiac mitochondria

To gain insight into the dynamics of superoxide/H2O2 production in cardiac mitochondria in BTHS, the maximum capacities of the 11 sites were measured in heart mitochondria isolated from wild‐type and tazkd mice at 3, 7 and 12 months of age (Fig. 5). To compare the maximum rate of H2O2 generation from each site between the two genotypes, we pharmacologically isolated the sites in intact mitochondria by providing the appropriate combination of inhibitors and substrates at saturating concentrations (see Experimental procedures). The sites with the highest maximum capacities were: IIIQo in complex III, IQ in complex I and IIF in complex II (Fig. 5). The maximum capacities of sites IQ and IIIQo were higher at 7 months of age in wild‐type mice (2‐way ANOVA, age: P < 0.003, interaction P = 0.1727) but this difference was absent in tazkd mice (2‐way ANOVA, age: P = 0.6422, interaction: P = 0.9998).

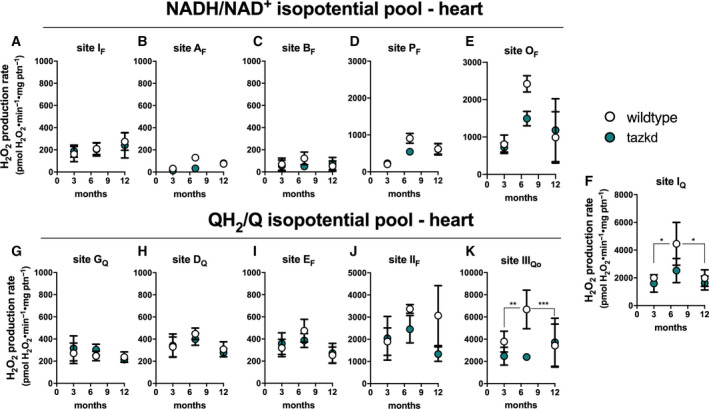

Fig. 5.

Maximum rate of superoxide/hydrogen peroxide production in isolated heart mitochondria from wild‐type and tazkd mice at 3, 8, and 12 months of age. The rate of superoxide/hydrogen peroxide generated by sites associated with the NADH/NAD+(A‐E) and QH2/Q (G‐H) isopotential pools. In the NADH/NAD+isopotential pool, the rate of superoxide/H2O2 production was measured from the flavin (F) binding sites of: (A) complex I (site IF), (B) site AF, (C) branched‐chain 2‐oxoacid dehydrogenase (site BF), (D) pyruvate dehydrogenase (site PF), and (E) 2‐oxoglutarate dehydrogenase (site OF). Complex I produces superoxide/H2O2 from two sites: (A) site IFand (F) site IQ(Q binding site). In sites associated with the QH2/Q isopotential pool, the rate of superoxide/hydrogen peroxide production was measured from (G) site GQ(glycerol 3‐phosphate dehydrogenase), (H) site DQ, in dihydroorotate dehydrogenase, (I) site EF, in the electron transfer flavoprotein (ETF) and ETF:ubiquinone oxidoreductase (ETF:QOR) system, (J) site IIF, in complex II, and (K) site IIIQo, in complex III. Values are mean ± SEM n ≧ 3 independent mitochondrial preparations and were normalized by mitochondrial protein (ptn). Two‐way ANOVA was used to determine significance. H2O2production rate from sites IQ and IIIQo is greater in 7‐month‐old compared to 3‐ and 12‐month‐old in wild‐type (2‐way ANOVA, age: P < 0.003, interaction P = 0.1727) but not in tazkd mice (2‐way ANOVA, age: P = 0.6422, interaction: P = 0.9998).*P< 0.05; **P< 0.01; ***P< 0.0001.

Figure 5 shows the rates of H2O2 generation from the 11 sites grouped according to their operating redox potentials. Sites AF, BF, PF and OF in the matrix dehydrogenases of 2‐oxoadipate, branched‐chain amino acids, pyruvate and 2‐oxoglutarate, respectively, belong to the NADH/NAD+ isopotential pool, together with site IF in complex I (Fig. 5A‐E). The electrons from NADH, generated by these dehydrogenases, are transferred via site IF to site IQ in complex I (Fig. 5F), and then to the next isopotential group, at the redox potential of QH2/Q (Fig. 5G‐K). In this isopotential group are sites GQ, DQ, EF, IIF, which reduce ubiquinone (Q) to ubiquinol (QH2), and the site in complex III (site IIIQo) that oxidizes the QH2 and ultimately transfers the electrons to cytochrome c, complex IV and O2.

Strikingly, the rate of superoxide/H2O2 production was not increased in tazkd mice at any time point analyzed compared to the matched wild‐type controls (2‐way ANOVA was used to identify significant associations with age and genotype for each site). Instead, there was a trend in the opposite direction, and the rate of H2O2 production from sites OF and IIIQo was actually lower in tazkd compared to wild‐type control mice at 7 months of age (Fig. 5E,K) (site OF 2423 ± 219 vs 1491 ± 195; site IIIQo 6680 ± 1735 vs 2390 ± 172.5, mean ± SEM pmol H2O2·min−1·mg protein−1; n = 3).

Skeletal muscle mitochondria

The rate of superoxide/H2O2 production from the 11 distinct sites was also measured in mitochondria isolated from skeletal muscle of wild‐type and tazkd mice at 7 and 12 months of age (Fig. 6) using the same approach described above. The sites with the highest maximum capacities were: site IIIQo, site IQ, site IIF and site OF (in the 2‐oxoglutarate dehydrogenase complex) (Fig. 6). The rate of H2O2 production from site IIIQo was higher in wild‐type and tazkd mice at 7 months of age (2‐way ANOVA P < 0.001, Sidak's post‐test). In tazkd mice, H2O2 production from site GQ, in glycerol phosphate dehydrogenase (GPDH), was the only site to be significantly higher when compared to the wild‐type littermates (1215 ± 34, n = 3 vs 1802 ± 100, n = 3, P = 0.0011; 2‐way ANOVA, Sidak's post‐test followed by Bonferroni correction for testing multiple sites) (Fig. 6I).

The assessment of H2O2 production rate at maximum capacity fundamentally measures the V max of electron leak to O2 and is broadly used to report mitochondrial oxidant production. The advantages of assessing H2O2 production at maximum capacity are discussed elsewhere [13]. However, these measurements are nonphysiological, as conventional substrates are presented in excess together with respiratory chain inhibitors. Under native conditions (i.e., in the absence of inhibitors) the rate of H2O2 generation is much lower [14, 22, 26], therefore maximum capacities cannot be used to predict the actual rate of H2O2 generation in intact cells or in vivo.

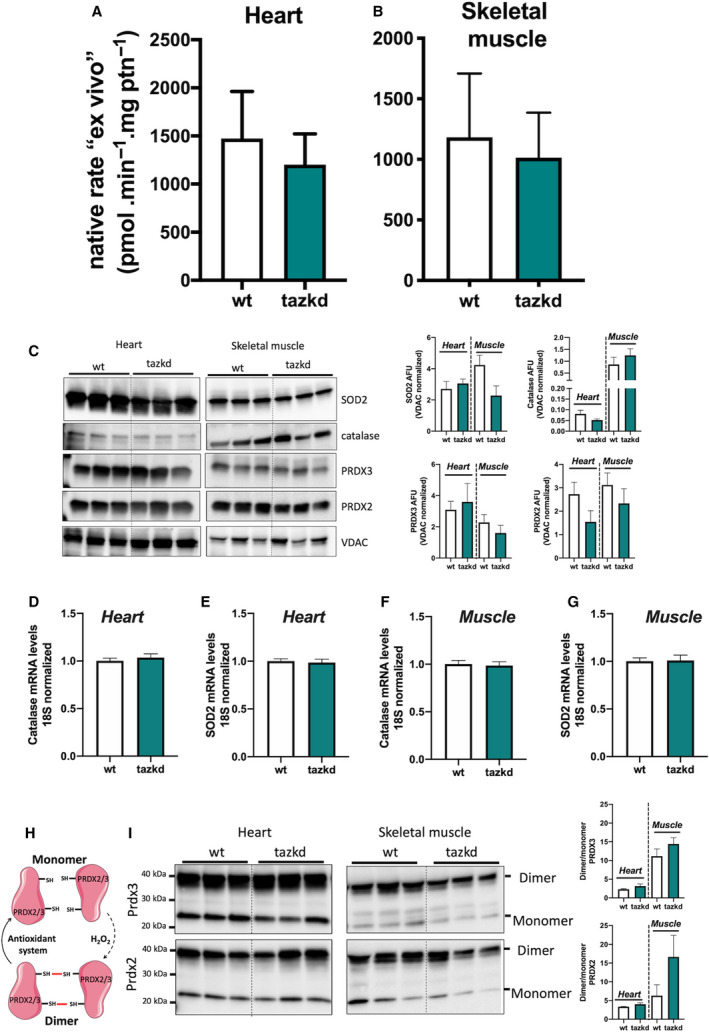

Ex vivo rates of mitochondrial H2O2 production at ‘rest’

In intact cells and tissues multiple substrates are oxidized simultaneously and various sites generate superoxide/H2O2 simultaneously and at different rates [26, 53]. The rate of H2O2 production in vivo is tissue‐specific and depends on many factors, including the substrates being preferentially oxidized and the abundance of the protein complex that contains the site from which the electrons leak to oxygen generating superoxide and then H2O2. For example, the rate of superoxide/H2O2 production from site GQ in 7‐month‐old mice is ~ 5‐fold higher in mitochondria from skeletal muscle than in those from heart (Figs 5G and 6I), which is correlated to the level of GPDH in these tissues [20]. To approach physiology and assess the rate of superoxide/H2O2 in isolated mitochondria under more realistic conditions, we carefully designed media that mimicked the cytosol of skeletal muscle at rest (not contracting) [26] and heart at rest (contracting but not under unusual load). Since individuals with BTHS are exercise intolerant the rest condition is physiologically more relevant. These media contained all the relevant substrates and effectors considered relevant to mitochondrial electron transport and superoxide/H2O2 production at the physiological concentration found in the cytosol of heart and skeletal muscle at ‘rest’ (see Table S1 and [26]). We refer to the rates of superoxide/H2O2 obtained in these media as ‘native’ ‘ex vivo’ rates. In Fig. 7A,B we used these experimental systems to determine the rates of mitochondrial superoxide/H2O2 production in conditions mimicking cardiac and skeletal muscle at rest.

Fig. 7.

Native ex vivo rates of superoxide/hydrogen peroxide production from isolated mitochondria from 12‐month‐old mice. Mitochondrial H2O2production rate was measured in complex media mimicking the cytosol of (A) heart and (B) skeletal muscle ‘at rest’ (see methods for media composition). Values are mean ± SEM, n ≧ 3 independent mitochondrial preparations and were normalized by mitochondrial protein (ptn). P > 0.05 Student's t‐test. (C) protein levels of MnSOD (SOD2), catalase, PRDX2, PRDX3, and VDAC in whole tissue homogenates from heart and skeletal muscle from wild‐type and tazkd mice. Immunoblots were quantified by densitometry normalized to VDAC levels. mRNA levels of catalase and SOD2 in the heart (D‐E) and skeletal muscle (F‐G). (H) schematic representation of the PRDX2 and PRDX3 catalytic cycle. (I) PRDX3 and PRDX2 dimer/monomer assessed under non‐reducing conditions in the presence of NEM. Immunoblots were quantified by densitometry. Values are mean ± SEM, n ≧ 3.

The rest state in our system was defined by a low rate of ATP synthesis, which was achieved by the addition of oligomycin. Although not ideal, oligomycin is necessary due to the contaminating ATPases present in the mitochondrial preparation.

Mitochondria isolated from heart and skeletal muscle from 12‐month‐old mice were incubated in their respective media. Strikingly, the ‘ex vivo’ rates of superoxide/H2O2 production by mitochondria from wild‐type and tazkd mice were indistinguishable when using mitochondria from heart (Fig. 7A) or from skeletal muscle (Fig. 7B). Importantly, there were no differences in the protein and mRNA levels for key enzymes responsible for superoxide and H2O2 scavenging, such as MnSOD, catalase, peroxiredoxin 2 and 3 (PRDX2 and PRDX3) (Fig. 7C‐G). We used the dimerization of PRDX2 and PRDX3 as an endogenous reporter of the subcellular generation of H2O2 in vivo. PRDX monomers can be oxidized by H2O2 forming a homodimer, which can be regenerated by the thioredoxin/thioredoxin reductase system [38] (Fig. 7H). Dimer/monomer ratio values of cytosolic PRDX2 and mitochondrial PRDX3 were indistinguishable between wild‐type and tazkd in the heart and skeletal muscle samples. Taken together, we detected no difference in the rates of superoxide/H2O2 production from most sites in heart or skeletal muscle mitochondria isolated from tazkd mice compared to wild‐type controls. The only exception was the capacity of site GQ, which was significantly increased in the skeletal muscle from tazkd mice at 7 months of age (Fig. 6I).

Discussion

In any intact system, whether cells or tissues in vivo, the rate of mitochondrial oxidant species production is the sum of superoxide/H2O2 production from up to 11 sites (Fig. 1). Mitochondrial oxidants play an important role in the development of many pathological states. In BTHS, excess mitochondrial oxidants are thought to have a causative role in the development of the cardioskeletal myopathy. However, these molecules are also important for normal cell signaling and physiology [52], which may explain why supplementation with broad and unselective antioxidants to prevent BTHS cardioskeletal myopathy has failed [11]. In addition, such nonspecific antioxidants may not target the appropriate oxidant species in the right cellular compartment. Still, a major gap in the field is the ability to identify and selectively target the site or sites from which the excess superoxide/H2O2 arises while at the same time preserving physiological oxidant production from other sites. We hypothesized that in tazkd mice, mitochondrial superoxide/H2O2 production is non‐homogeneous and specific sites (perhaps those in the respiratory chain complexes directly affected by CL) may generate mitochondrial oxidants at abnormally high rates. The excess superoxide/H2O2 production could be then normalized using a new generation of suppressors of mitochondrial electron leak at sites IQ and IIIQo, suppressor of site IQ electron leak (S1QELs) and suppressor of site IIIQo electron leak (S3QELs) [54, 55].

The present study was set out (a) to identify which site(s) have increased capacity to generate excess superoxide/H2O2 in heart and skeletal muscle of tazkd mice and (b) to measure the physiologically relevant rates of superoxide/H2O2 production from these sites ‘ex vivo’ using complex media mimicking cardiac and skeletal muscle cytosol at rest. Strikingly, we found that the overall maximum capacities of superoxide/H2O2 generation in mitochondria isolated from cardiac and skeletal muscle were not different between the genotypes. Site GQ was the only exception and had a higher capacity in tazkd mice than controls at 7 months of age. In the more physiological approach, we found that there was no difference in the ‘ex vivo’ rates of superoxide/H2O2 production in mitochondria from heart and skeletal muscle between tazkd mice and their littermate wild‐type controls.

Mitochondrial ATP supply is crucial to satisfy the high energetic demand of cardiac and skeletal muscle. Therefore, it is not surprising that altered CL composition in BTHS results in cardioskeletal myopathy. Loss of CL alters mitochondrial morphology [56] and causes the destabilization of the components of the oxidative phosphorylation [45, 46, 57]. Different in vitro cellular data overwhelmingly reported that tafazzin deficiency in BTHS is associated with increased production of mitochondrial oxidants [7, 35]. Indeed, targeting mitochondrial redox reactions with mitoTempo and linoleic acid ameliorated myocardial dysfunction in cellular models of BTSH [12, 35], suggesting that mitochondrial oxidants may have a causative role in BTHS pathogenesis.

The reliable measurement of mitochondrial superoxide/H2O2 levels and production rates in tissues in vivo and intact cells is very challenging due to the lack of specific probes. For example, dichlorodihydrofluorescein (DCFH2), which has been widely used to report differences in oxidant production in BTHS [31, 32, 34, 56], does not directly react with H2O2 [58]. Importantly, H2O2‐mediated DCFH2 oxidation is dependent on iron uptake [59] and loss of CL increases the levels of iron uptake genes [60]. Importantly, DCFH2 itself can generate superoxide in the presence of oxygen [58]. MitoSOX has also been widely used to measure levels of mitochondrial superoxide in intact cells and has been used to report mitochondrial oxidants in different BTHS models [7, 12, 29, 34, 35]. However, the results obtained with mitoSOX should be interpreted with caution [58]. MitoSOX red fluorescence can be the result of unspecific oxidation in the presence of iron and therefore does not solely or even dominantly reflect superoxide levels. Also, its accumulation in the mitochondria is dependent on both mitochondrial and plasma membrane potentials and it is advised for the signal to be normalized to correct for this effect. Lastly, depending on the concentrations, mitoSOX disturbs the respiratory chain, which will impact superoxide generation [61]. Taken together, the interpretation of data obtained using these probes should be reevaluated. Finally, the other probe commonly used to report H2O2 in isolated mitochondria in BTHS is Amplex ultraRed [27, 30, 33, 47]. Although one should be aware that this probe can also provide some unspecific signal depending on the source of mitochondria [58, 62], Amplex ultraRed is more specific for H2O2 and is more reliable than its predecessor, Amplex Red [39]. Interestingly, the published data using Amplex ultraRed are more heterogeneous as some studies show a higher rate of H2O2 generation in the context of tazkd [30, 33] while few others reported no difference [33, 47].

In the present work, we provide a comprehensive assessment of the rate of superoxide/H2O2 generation from each individual site in heart and skeletal muscle mitochondria during the progression of BTHS in tazkd mice. Strikingly, we found no major differences in the maximum capacities of the different sites (Figs 5 and 6) despite a clear phenotype of reduced oxidative capacity (Figs 2 and 3). In a complementary approach, it has been shown that mitochondrial‐targeted catalase‐tazkd mice, which overexpress the H2O2‐degrading enzyme catalase (CAT) specifically targeted to the mitochondrial matrix, fails to improve cardioskeletal myopathy despite the lower levels of H2O2 in the mitochondrial matrix [33]. Therefore, either i) matrix H2O2 is not responsible for the development of cardioskeletal myopathologies or ii) cardioskeletal myopathologies is caused by matrix superoxide. Importantly, it was recently reported that the mitochondrial‐targeted antioxidant mitoQ and the general antioxidant n‐acetylcysteine did not improve cardiopathologies in tazkd mice1.

To overcome the drawbacks of trying to measure levels and rates of production of mitochondrial oxidants in intact cells with DCFH2 and mitoSOX and to be able to approach physiology using isolated mitochondria, we designed ‘ex vivo’ media that mimicked the cytosol of heart and skeletal muscle at rest (Fig. 7, Table S1). This approach was previously validated in three different media designed to mimic the cytosol of skeletal muscle at rest and during mild and intense exercise [26]. The rate of superoxide/H2O2 generation was higher at ‘rest’ than in conditions mimicking exercise. At ‘rest’ sites IQ and IIF accounted for half of the total measured rate of superoxide/H2O2 production. Interestingly, the contribution of site IIIQo, which has a high capacity for generating superoxide/H2O2, was similar to the low capacity site IF [26]. The contributions of sites IQ and IIIQo were further confirmed in C2C12 myoblasts using S1QELs and S3QELs [63]. From these results we concluded that the mitochondrial rate of superoxide/H2O2 production measured at maximum capacity (where individual substrates are present in excess in the presence of inhibitors) should not be used to predict the rates in tissues in vivo.

Although the more complex ‘ex vivo’ approach offers notable advantages because it uses all the relevant metabolites and effectors at the physiological concentrations found in the cytosol of cardiac and skeletal muscle cells (Table S1), it is still not perfect. The media design for these experiments were based on the levels of metabolites and effectors found in the cytosol of rat skeletal muscle at rest and cardiac muscle cells in beating hearts not under load (Table S1 and [26]) and may not be a simulacrum of the metabolites in the mouse tissues, particularly since oligomycin was used to inhibit the mitochondrial ATP synthase and prevent high recycling of ATP produced by contaminating ATPases. In addition, and perhaps critically, the concentrations of these metabolites are unknown in tazkd cardiac and skeletal cells, so they were assumed to be similar between wild‐type and tazkd mice. It is noteworthy that the lack of difference in the rate of superoxide/H2O2 generation at maximum capacity or ex vivo between wild‐type and tazkd is not caused by alterations in the antioxidant defense system (Fig. 7C‐I).

Finally, it has been previously described that the doxycycline concentration in the diet used to induce Tazkd in this model does not cause mitochondrial dysfunction and does not modulate mitochondrial superoxide/H2O2 generation [30]. Curiously, wild‐type mice on doxycycline diet gain significant more weight than the tazkd littermates (Figs 2 and 3) [6, 30]. In our facility, 8‐month‐old wild‐type mice weighed as much as genetically obese, ob/ob, mice [48]. Obesity is associated with altered glucose homeostasis and insulin resistance, which has been previously reported in tazkd wild‐type littermate mice on the doxycycline diet [30]. Mitochondrial generation of superoxide/H2O2 is higher in the heart and skeletal muscle of different models of obesity [64, 65]. Therefore, from 8 to 12 months of age, we cannot rule out the possibility that increased mitochondrial oxidant production in the heart and skeletal muscle in the tazkd could be masked by an independent effect of obesity and associated changes on mitochondrial oxidant production in the wild‐type controls. It is important to note, however, that at 3‐months of age, there was no difference in body weight between genotypes and therefore, the potential confounding effect of body weight was absent. Under these conditions, we still failed to detect any differences in the capacity of superoxide/H2O2 production between wild‐type and tazkd (Fig. 5).

Conclusion

We used a systematic approach to determine the maximum capacities and physiologically relevant rates of mitochondrial superoxide/H2O2 production from all known sites associated with substrate oxidation in mitochondria isolated from tazkd mice and their wild‐type littermates. Our results show that cardioskeletal myopathy in tazkd is not associated with increased production of mitochondrial superoxide and H2O2. Future studies using other models of BTHS, such as the tafazzin knockout mice, will be important to elucidate the relationship between mitochondrial oxidant generation and BTSH cardioskeletal pathologies.

Author contributions

RLSG conceptualized the project, performed the experiments, analyzed the data, prepared the figures and wrote the manuscript. MS performed the quantification of CL and MLCL and revised the manuscript. AB performed the CLAMS experiments and revised the manuscript. MD conceptualized and supervised the project, wrote and revised the manuscript. GSH provided laboratory space and consumables, supervised the project, wrote and revised the manuscript.

Funding

RLSG was supported by the BTHS Foundation (Idea Grant) and by the Sabri Ülker Center; AB was supported by a Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft Research Fellowship (BA 4925/1‐1) and a Deutsches Zentrum für Herz‐Kreislauf‐Forschung Junior Research Group Grant; GSH laboratory was supported by grants from The Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation and the National Institutes of Health, USA; and MS was supported by the National Institutes of Health grant (R01 GM115593).

Supporting information

Table S1. Cardiolipin deficiency in Barth syndrome is not associated with increased superoxide/H2O2 production in heart and skeletal muscle mitochondria.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank members of the Hotamisligil laboratory especially Dr. Karen Inouye for her valuable help in the mouse house and Dr. Güneş Parlakgül for the comments. We are grateful to Dr. Steven Claypool for kindly providing an aliquot of anti‐tafazzin antibody and Michael MacArthur for assisting on the treadmill experiments.

Edited by Barry Halliwell

Footnotes

Colin Phoon et al., communication at the Barth Syndrome Foundation Conference in July 2018, Florida.

Data accessibility

All the data presented here are contained in this manuscript.

References

- 1. Horvath SE and Daum G (2013) Lipids of mitochondria. Prog Lipid Res 52, 590–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schlame M, Rua D and Greenberg ML (2000) The biosynthesis and functional role of cardiolipin. Prog Lipid Res 39, 257–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Saric A, Andreau K, Armand AS, Møller IM and Petit PX (2016) Barth syndrome: from mitochondrial dysfunctions associated with aberrant production of reactive oxygen species to pluripotent stem cell studies. Front Genet 6, 359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schlame M, Ren M, Xu Y, Greenberg ML and Haller I (2005) Molecular symmetry in mitochondrial cardiolipins. Chem Phys Lipids 138, 38–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Xu Y, Malhotra A, Ren M and Schlame M (2006) The enzymatic function of tafazzin. J Biol Chem 281, 39217–39224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Acehan D, Vaz F, Houtkooper RH, James J, Moore V, Tokunaga C, Kulik W, Wansapura J, Toth MJ, Strauss A et al (2011) Cardiac and skeletal muscle defects in a mouse model of human Barth syndrome. J Biol Chem 286, 899–908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lou W, Reynolds CA, Li Y, Liu J, Hüttemann M, Schlame M, Stevenson D, Strathdee D and Greenberg ML (2018) Loss of tafazzin results in decreased myoblast differentiation in C2C12 cells: a myoblast model of Barth syndrome and cardiolipin deficiency. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipids 1863, 857–865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Barth PG, Scholte HR, Berden JA, Van Der Klei‐Van Moorsel JM, Luyt‐Houwen IEM, Van’T Veer‐Korthof ET, Van Der Harten JJ and Sobotka‐Plojhar MA (1983) An X‐linked mitochondrial disease affecting cardiac muscle, skeletal muscle and neutrophil leucocytes. J Neurol Sci 62, 327–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dudek J and Maack C (2017) Barth syndrome cardiomyopathy. Cardiovasc Res 113, 399–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Soustek MS, Falk DJ, Mah CS, Toth MJ, Schlame M, Lewin AS and Byrne BJ (2011) Characterization of a transgenic short hairpin RNA‐induced murine model of tafazzin deficiency. Hum Gene Ther 22, 865–871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ren M, Miller PC, Schlame M and Phoon CKL (2019) A critical appraisal of the tafazzin knockdown mouse model of Barth syndrome: what have we learned about pathogenesis and potential treatments? Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 317, H1183–H1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wang G, McCain ML, Yang L, He A, Pasqualini FS, Agarwal A, Yuan H, Jiang D, Zhang D, Zangi L et al (2014) Modeling the mitochondrial cardiomyopathy of Barth syndrome with induced pluripotent stem cell and heart‐on‐chip technologies. Nat Med 20, 616–623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Brand MD (2016) Mitochondrial generation of superoxide and hydrogen peroxide as the source of mitochondrial redox signaling. Free Radic Biol Med. 100, 14–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Quinlan CL, Treberg JR, Perevoshchikova IV, Orr AL and Brand MD (2012) Native rates of superoxide production from multiple sites in isolated mitochondria measured using endogenous reporters. Free Radic Biol Med 53, 1807–1817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Quinlan CL, Goncalves RLS, Hey‐Mogensen M, Yadava N, Bunik VI and Brand MD (2014) The 2‐oxoacid dehydrogenase complexes in mitochondria can produce superoxide/hydrogen peroxide at much higher rates than complex I. J Biol Chem 289, 8312–8325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Goncalves RLS, Bunik VI and Brand MD (2016) Production of superoxide/hydrogen peroxide by the mitochondrial 2‐oxoadipate dehydrogenase complex. Free Radic Biol Med 91, 247–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Perevoshchikova IV, Quinlan CL, Orr AL, Gerencser AA and Brand MD (2013) Sites of superoxide and hydrogen peroxide production during fatty acid oxidation in rat skeletal muscle mitochondria. Free Radic Biol Med 61, 298–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hey‐Mogensen M, Goncalves RLS, Orr AL and Brand MD (2014) Production of superoxide/H2O2 by dihydroorotate dehydrogenase in rat skeletal muscle mitochondria. Free Radic Biol Med 72, 149–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Quinlan CL, Orr AL, Perevoshchikova IV, Treberg JR, Ackrell BA and Brand MD (2012) Mitochondrial complex II can generate reactive oxygen species at high rates in both the forward and reverse reactions. J Biol Chem 287, 27255–27264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Orr AL, Quinlan CL, Perevoshchikova IV and Brand MD (2012) A refined analysis of superoxide production by mitochondrial sn‐glycerol 3‐phosphate dehydrogenase. J Biol Chem 287, 42921–42935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Quinlan CL, Gerencser AA, Treberg JR and Brand MD (2011) The mechanism of superoxide production by the antimycin‐inhibited mitochondrial Q‐cycle. J Biol Chem 286, 31361–31372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Quinlan CL, Perevoshchikova IV, Hey‐Mogensen M, Orr AL and Brand MD (2013) Sites of reactive oxygen species generation by mitochondria oxidizing different substrates. Redox Biol 1, 304–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Arruda AP, Pers BM, Parlakgul G, Güney E, Goh T, Cagampan E, Lee GY, Goncalves RL and Hotamisligil GS (2017) Defective STIM‐mediated store operated Ca2+ entry in hepatocytes leads to metabolic dysfunction in obesity. Elife 6, e29968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cieslar JH and Dobson GP (2000) Free [ADP] and aerobic muscle work follow at least second order kinetics in rat gastrocnemius in vivo . J Biol Chem 275, 6129–6134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Berchtold MW, Brinkmeier H and Müntener M (2000) Calcium ion in skeletal muscle: its crucial role for muscle function, plasticity, and disease. Physiol Rev 80, 1215–1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Goncalves RLS, Quinlan CL, Perevoshchikova IV, Hey‐Mogensen M and Brand MD (2015) Sites of superoxide and hydrogen peroxide production by muscle mitochondria assessed ex vivo under conditions mimicking rest and exercise. J Biol Chem 290, 209–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Szczepanek K, Allegood J, Aluri H, Hu Y, Chen Q and Lesnefsky EJ (2016) Acquired deficiency of tafazzin in the adult heart: Impact on mitochondrial function and response to cardiac injury. Biophys Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipids Biochim 1861, 294–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chen S, He Q and Greenberg ML (2008) Loss of tafazzin in yeast leads to increased oxidative stress during respiratory growth. Mol Microbiol 68, 1061–1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chowdhury A, Aich A, Jain G, Wozny K, Lüchtenborg C, Hartmann M, Bernhard O, Balleiniger M, Alfar EA, Zieseniss A et al (2018) Defective mitochondrial cardiolipin remodeling dampens HIF‐1α expression in hypoxia. Cell Rep 25, 561–570.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cole LK, Mejia EM, Vandel M, Sparagna GC, Claypool SM, Dyck‐Chan L, Klein J and Hatch GM (2016) Impaired cardiolipin biosynthesis prevents hepatic steatosis and diet‐induced obesity. Diabetes 65, 3289–3300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dudek J, Cheng IF, Balleininger M, Vaz FM, Streckfuss‐Bömeke K, Hübscher D, Vukotic M, Wanders RJA, Rehling P and Guan K (2013) Cardiolipin deficiency affects respiratory chain function and organization in an induced pluripotent stem cell model of Barth syndrome. Stem Cell Res 11, 806–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Dudek J, Cheng I, Chowdhury A, Wozny K, Balleininger M, Reinhold R, Grunau S, Callegari S, Toischer K, Wanders RJ et al (2016) Cardiac‐specific succinate dehydrogenase deficiency in Barth syndrome. EMBO Mol Med 8, 139–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Johnson JM, Ferrara PJ, Verkerke ARP, Coleman CB, Wentzler EJ, Neufer PD, Kew KA, de Castro Brás LE and Funai K (2018) Targeted overexpression of catalase to mitochondria does not prevent cardioskeletal myopathy in Barth syndrome. J Mol Cell Cardiol 121, 94–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. He Q, Wang M, Harris N and Han X (2013) Tafazzin knockdown interrupts cell cycle progression in cultured neonatal ventricular fibroblasts. Am J Physiol Hear Circ Physiol 305, H1332–H1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. He Q, Harris N, Ren J and Han X (2014) Mitochondria‐targeted antioxidant prevents cardiac dysfunction induced by tafazzin gene knockdown in cardiac myocytes. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2014, 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Affourtit C, Quinlan CL and Brand MD (2012) Measurement of proton leak and electron leak in isolated mitochondria. Methods Mol Biol 810, 165–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lu YW, Galbraith L, Herndon JD, Lu YL, Pras‐Raves M, Vervaart M, Van Kampen A, Luyf A, Koehler CM, McCaffery JM et al (2016) Defining functional classes of Barth syndrome mutation in humans. Hum Mol Genet 25, 1754–1770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bayer SB, Maghzal G, Stocker R, Hampton MB and Winterbourn CC (2013) Neutrophil‐mediated oxidation of erythrocyte peroxiredoxin 2 as a potential marker of oxidative stress in inflammation. FASEB J 27, 3315–3322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Quinlan CL, Perevoschikova IV, Goncalves RLS, Hey‐Mogensen M and Brand MD (2013) The determination and analysis of site‐specific rates of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species production. Methods Enzymol 526, 189–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sun G, Yang K, Zhao Z, Guan S, Han X and Gross RW (2008) Matrix‐assisted laser desorption/ionization time‐of‐flight mass spectrometric analysis of cellular glycerophospholipids enabled by multiplexed solvent dependent analyte‐matrix interactions. Anal Chem 80, 7576–7585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Tschöp MH, Speakman JR, Arch JRS, Auwerx J, Brüning JC, Chan L, Eckel RH, Farese RV, Galgani JE, Hambly C et al (2012) A guide to analysis of mouse energy metabolism. Nat Methods 9, 57–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bartelt A, Widenmaier SB, Schlein C, Johann K, Goncalves RLS, Eguchi K, Fischer AW, Parlakgül G, Snyder NA, Nguyen TB et al (2018) Brown adipose tissue thermogenic adaptation requires Nrf1‐mediated proteasomal activity. Nat Med 24, 292–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Powers C, Huang Y, Strauss A and Khuchua Z (2013) Diminished exercise capacity and mitochondrial bc 1 complex deficiency in tafazzin‐knockdown mice. Front Physiol 4, 74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kiebish MA, Yang K, Liu X, Mancuso DJ, Guan S, Zhao Z, Sims HF, Cerqua R, Cade WT, Han X et al (2013) Dysfunctional cardiac mitochondrial bioenergetic, lipidomic, and signaling in a murine model of Barth syndrome. J Lipid Res 54, 1312–1325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Huang Y, Powers C, Madala SK, Greis KD, Haffey WD, Towbin JA, Purevjav E, Javadov S, Strauss AW and Khuchua Z (2015) Cardiac metabolic pathways affected in the mouse model of Barth syndrome. PLoS One 10, e0128561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Claypool SM, Oktay Y, Boontheung P, Loo JA and Koehler CM (2008) Cardiolipin defines the interactome of the major ADP/ATP carrier protein of the mitochondrial inner membrane. J Cell Biol 182, 937–950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kim J, Lee K, Fujioka H, Tandler B and Hoppel CL (2018) Cardiac mitochondrial structure and function in tafazzin‐knockdown mice. Mitochondrion 43, 53–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Broderick TL, Wang D, Jankowski M and Gutkowska J (2014) Unexpected effects of voluntary exercise training on natriuretic peptide and receptor mRNA expression in the ob/ob mouse heart. Regul Pept 188, 52–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Soustek MS, Baligand C, Falk DJ, Walter GA, Lewin AS and Byrne BJ (2015) Endurance training ameliorates complex 3 deficiency in a mouse model of Barth syndrome. J Inherit Metab Dis 38, 915–922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kowaltowski AJ, de Souza‐Pinto NC, Castilho RF and Vercesi AE (2009) Mitochondria and reactive oxygen species. Free Radic Biol Med 47, 333–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Turrens JF (2003) Mitochondrial formation of reactive oxygen species. J Physiol 552, 335–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Finkel T (2012) Signal transduction by mitochondrial oxidants. J Biol Chem 287, 4434–4440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Wong HS, Benoit B and Brand MD (2019) Mitochondrial and cytosolic sources of hydrogen peroxide in resting C2C12 myoblasts. Free Radic Biol Med 130, 140–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Brand MD, Goncalves RLS, Orr AL, Vargas L, Gerencser AA, Borch Jensen M, Wang YT, Melov S, Turk CN, Matzen JT et al (2016) Suppressors of superoxide‐H2O2 production at site IQ of mitochondrial complex I protect against stem cell hyperplasia and ischemia‐reperfusion injury. Cell Metab 24, 582–592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Orr AL, Vargas L, Turk CN, Baaten J, Matzen JT, Dardov V, Attle SJ, Li J, Quackenbush DC, Goncalves RLS et al (2015) Suppressors of superoxide production from mitochondrial complex III. Nat Chem Biol 11, 834–839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Khuchua Z, Vaz F, Acehan D and Strauss A (2011) Mouse model of human Barth syndrome, mitochondrial cardiolipin disorder. Mol Genet Metab 102, 295. [Google Scholar]

- 57. McKenzie M, Lazarou M, Thorburn DR and Ryan MT (2006) Mitochondrial respiratory chain supercomplexes are destabilized in Barth syndrome patients. J Mol Biol 361, 462–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Kalyanaraman B, Hardy M, Podsiadly R, Cheng G and Zielonka J (2017) Recent developments in detection of superoxide radical anion and hydrogen peroxide: opportunities, challenges, and implications in redox signaling. Arch Biochem Biophys 617, 38–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Tampo Y, Kotamraju S, Chitambar CR, Kalivendi SV, Keszler A and Kalyanaraman JJB (2003) Oxidative stress‐induced iron signaling is responsible for peroxide‐dependent oxidation of dichlorodihydrofluorescein in endothelial cells role of transferrin receptor‐dependent iron uptake in apoptosis. Circ Res 92, 56–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Patil VA, Fox JL, Gohil VM, Winge DR and Greenberg ML (2013) Loss of cardiolipin leads to perturbation of mitochondrial and cellular iron homeostasis. J Biol Chem 288, 1696–1705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Polster BM, Nicholls DG, Ge SX and Roelofs BA (2014) Use of potentiometric fluorophores in the measurement of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species. Methods in Enzymology 547, 225–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Miwa S, Treumann A, Bell A, Vistoli G, Nelson G, Hay S and Von Zglinicki T (2016) Carboxylesterase converts Amplex red to resorufin: implications for mitochondrial H2O2 release assays. Free Radic Biol Med 90, 173–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Goncalves RLS, Watson MA, Wong HS, Orr AL and Brand MD (2020) The use of site‐specific suppressors to measure the relative contributions of different mitochondrial sites to skeletal muscle superoxide and hydrogen peroxide production. Redox Biol 28, 101341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Anderson EJ, Lustig ME, Boyle KE, Woodlief TL, Kane DA, Lin CT, Price JW, Kang L, Rabinovitch PS, Szeto HH et al (2009) Mitochondrial H2O2 emission and cellular redox state link excess fat intake to insulin resistance in both rodents and humans. J Clin Invest 119, 573–581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Sverdlov AL, Elezaby A, Qin F, Behring JB, Luptak I, Calamaras TD, Siwik DA, Miller EJ, Liesa M, Shirihai OS et al (2016) Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species mediate cardiac structural, functional, and mitochondrial consequences of diet‐induced metabolic heart disease. J Am Heart Assoc 5, e002555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Cardiolipin deficiency in Barth syndrome is not associated with increased superoxide/H2O2 production in heart and skeletal muscle mitochondria.

Data Availability Statement

All the data presented here are contained in this manuscript.