Abstract

Introduction

Safety and efficacy results of the phase 1 study and phase 1/2 extension study of the bispecific antibody emicizumab in patients with severe haemophilia A with or without factor VIII inhibitors for up to 2.8 years were reported previously.

Aim

To evaluate further longer‐term data including patients’ perceptions at study completion.

Methods

Emicizumab was administered subcutaneously once weekly at maintenance doses of 0.3, 1 or 3 mg/kg with potential up‐titration. All patients were later switched to the approved maintenance dose of 1.5 mg/kg.

Results

Eighteen patients received emicizumab for up to 5.8 years. Most adverse events were mild and unrelated to emicizumab. Annualized bleeding rates (ABRs) for bleeds treated with coagulation factors decreased from pre‐emicizumab rates or remained zero in all patients. The median ABRs were low at 1.25, 0.83 and 0.22 during the 0.3, 1 and 3 mg/kg dosing periods, respectively. Of 8 patients who decreased their doses from 3 to 1.5 mg/kg, ABRs decreased in 4, remained at zero in 2, and increased in 2. Total time spent with symptoms associated with treated bleeds decreased in all patients except 2. All patients answered ‘improved’ for bleeding severity and time until bleeding stops, except 1 answering ‘slightly improved’. Most patients answered ‘improved’ or ‘slightly improved’’ for daily life and feelings; in particular, all patients except 1 answered ‘improved’ or ‘slightly improved’ for anxiety.

Conclusions

Long‐term emicizumab prophylaxis for up to 5.8 years was safe and efficacious, and may improve patients’ daily lives and feelings, regardless of inhibitor status.

Keywords: bispecific antibody, clinical trial, emicizumab, haemophilia A, long‐term observation, prophylaxis

1. INTRODUCTION

Patients with congenital haemophilia A present with an increased bleeding tendency as a result of deficient or dysfunctional factor VIII (FVIII). FVIII prophylaxis is a current standard of care for patients with severe haemophilia A without neutralizing antibodies against FVIII (inhibitors). 1 Even with frequent intravenous administration of FVIII, patients are still at risk of bleeding and joint damage. 2 , 3 , 4 Moreover, inhibitors develop in approximately 30% of patients with severe haemophilia A receiving FVIII, 5 , 6 which hinders FVIII, makes bleeding control difficult, and leads to significant medical complications. 7 , 8 For patients undergoing immune tolerance induction therapy to eradicate inhibitors or those refractory to such therapy, bleeds are controlled with bypassing agents (BPAs) such as activated prothrombin complex concentrate (aPCC) or recombinant activated factor VIIa (rFVIIa), although efficacy can be sub‐optimal. 9 , 10

Emicizumab (HEMLIBRA®; Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) is a bispecific antibody mimicking the cofactor function of activated FVIII. 11 Clinically, meaningful efficacy for bleeding prevention was demonstrated with subcutaneous maintenance doses of 1.5 mg/kg every week (QW), 3 mg/kg every 2 weeks (Q2 W) and 6 mg/kg every 4 weeks (Q4 W) in patients with haemophilia A with or without inhibitors regardless of age. 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 However, experiences in long‐term administration are limited. Previously, we reported the safety and efficacy of emicizumab in patients with severe haemophilia A for up to 2.8 years in the phase 1 study and phase 1/2 extension study. 17 , 18 Here, we report the results at study completion to evaluate further longer‐term data for up to 5.8 years. Also, included are data on patients’ and their families’ perceptions, data after changing their doses to the approved maintenance dose, and time profile data of FVIII inhibitor titres.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

The multicentre, open‐label, non‐randomized phase 1 study (which started May 2013) and phase 1/2 extension study (which started August 2013) were conducted to investigate the safety and efficacy of subcutaneous emicizumab prophylaxis in patients with severe haemophilia A. The protocols were approved by the institutional review board at each centre, and the studies were conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki, the ICH Guideline for Good Clinical Practice and the Good Post‐marketing Study Practice. All patients and/or their legally authorized representatives provided written informed consent. The studies were registered at http://www.clinicaltrials.jp (JapicCTI‐121934 and JapicCTI‐132195). Details of the materials and methods, such as inclusion and exclusion criteria, were described previously. 17 , 18

2.1. Study design

Eighteen Japanese patients with severe haemophilia A with or without inhibitors aged ≥12 years were enrolled. Before emicizumab prophylaxis, patients had received episodic or prophylactic treatment with coagulation factors. In the 12‐week phase 1 study, 6 patients were enrolled in each of 3 groups: 0.3, 1, 3 mg/kg QW group. Patients with sub‐optimal bleeding control were offered an opportunity to up‐titrate the dose to 1 or 3 mg/kg in the phase 1/2 study. In all patients, their doses were changed to the approved maintenance dose of 1.5 mg/kg QW. The phase 1/2 study continued until emicizumab became commercially available for all patients. FVIII or BPAs were administered for breakthrough bleeds as necessary. At the time of study initiation, patients were instructed to treat breakthrough bleeds according to standard clinical practice. Following the occurrence of thromboembolic events and thrombotic microangiopathy in the HAVEN 1 study, 12 a guidance requesting patients with inhibitors to use the lowest expected dose of BPAs, preferably rFVIIa, to achieve haemostasis for breakthrough bleeds was issued by sponsor in November 2016.

2.2. Outcome measures

The primary endpoint was safety, including adverse events (AEs), physical examination, laboratory tests, vital signs, 12‐lead electrocardiography and immunogenicity. Inhibitors were measured by a clotting time‐based Bethesda assay with emicizumab in plasma samples neutralized by adding two anti‐emicizumab idiotype monoclonal antibodies ex vivo. 19

Information on bleeds, such as dates of onset and resolution of bleeding symptoms and treatment with coagulation factors, were collected to evaluate efficacy outcomes including annualized bleeding rates (ABRs) for bleeds treated with coagulation factors and total time spent with symptoms associated with treated bleeds.

To investigate changes in patients since starting emicizumab prophylaxis, we invited patients and their families to complete a questionnaire (Appendix S1), on a voluntary basis, reporting their perceptions regarding bleeding symptoms, joint symptoms, daily life and feelings at several time points. We also asked patients with up‐titration to answer the questionnaire to investigate changes from before up‐titration.

2.3. Statistical analysis

All analyses were conducted using combined data from the phase 1 study and phase 1/2 extension study. All efficacy analyses were exploratory. ABRs for treated bleeds during emicizumab prophylaxis were compared with those during the 6 months before starting emicizumab prophylaxis which were calculated retrospectively from medical records. ABRs were calculated as the number of treated bleeds normalized to 1 year. Bleeds that occurred after dose modification were summarized according to the modified dose. Total time spent with symptoms associated with bleeds was derived from dates of onset and resolution of treated bleeds reported by patients. The percentage of total time spent with bleeding symptoms to the total observation period (‘total time spent with bleeding symptoms’) was calculated for the periods before and during emicizumab prophylaxis. The perceptions of patients and family members on the first questionnaire are summarized. SAS software version 9.2 was used for the analyses.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Study population

In the 12‐week phase 1 study, 18 patients (11 with inhibitors and 7 without inhibitors) aged 12–58 years were enrolled in 3 dose groups (6 patients for each). Of the 18 patients, 1 patient in the 1 mg/kg QW group discontinued emicizumab administration on Day 29 due to AE; all the other 17 patients completed the phase 1 study. Of those 17 patients, 16 patients were enrolled in the phase 1/2 study (6, 5, and 5 patients in the 0.3, 1 and 3 mg/kg QW groups, respectively). Demographics and baseline characteristics of patients have been reported previously. 17 The medians (ranges) of total treatment duration through the phase 1 study plus its extension phase 1/2 study were 5.2 years (5.2–5.8 years), 4.8 years (29 days–5.3 years) and 4.3 years (85 days–4.8 years) in the 0.3, 1 and 3 mg/kg QW groups, respectively.

3.2. Safety

No new significant safety findings were identified since the previous report. 18 All patients experienced at least 1 AE, and 226 AEs were reported. The frequency of AEs was constant over time. Most AEs (89.4%) were mild. Three AEs (appendicitis, mesenteric haematoma and femur fracture) were severe and considered serious but unrelated to emicizumab. Eight patients experienced mild injection site reactions. One mild injection site erythema resulted in discontinuation of treatment on Day 29, but resolved. No thrombotic events including thrombotic microangiopathy or deaths were reported. All AEs related to emicizumab were mild: injection site erythema, injection site haematoma, and injection site pruritus in 3 patients each, and injection site discomfort, injection site induration, injection site pain, injection site rash, malaise, diarrhoea, nausea, blood creatine phosphokinase increased, C‐reactive protein increased, urinary tract infection and pain in extremity in 1 patient each. No clinically significant changes in physical examination, laboratory tests, vital signs and electrocardiography were observed.

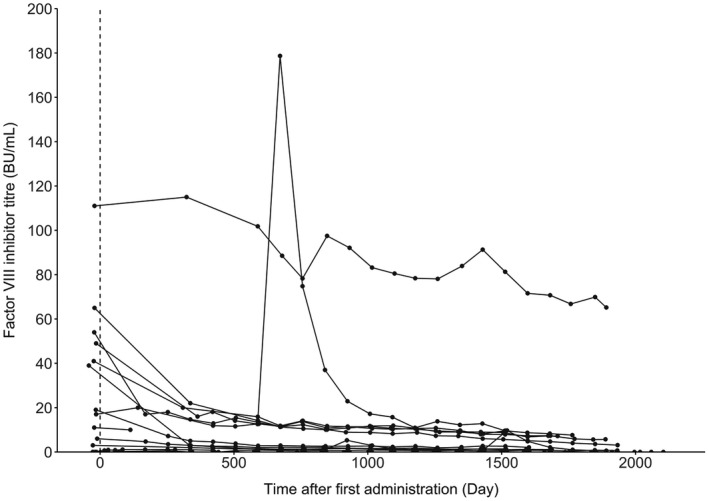

Four patients tested positive for anti‐emicizumab antibodies, but there was no impact on their pharmacokinetics or pharmacodynamics such as activated partial thromboplastin time or activated factor XI‐triggered thrombin generation, indicating the anti‐emicizumab antibodies were non‐neutralizing and did not affect the efficacy of emicizumab. FVIII inhibitor titres declined in the majority of the 11 patients with inhibitors even without immune tolerance induction therapy (Figure 1). A transient spike in FVIII inhibitor titres was observed on Day 672 in 1 patient with inhibitors after repeated administrations of aPCC (38.5–115.4 U/kg/day on 7 days out of Days 624–635). The D‐dimer level during the aPCC treatment remained under 0.5 µg/mL and no thrombophilia was observed. Two patients without inhibitors at baseline tested positive for inhibitors during emicizumab prophylaxis: one patient (3–5) who had inhibitors before enrolment tested positive (0.6 BU/mL) at only 1 time point (Day 253) transiently, and the other patient (2–6) who never had inhibitors before enrolment tested positive with a low‐titre values (0.6–1.1 BU/mL) at all time points throughout the studies except Day 442. Both patients were adult and had received FVIII prophylaxis for at least 6 months before enrolment. Titre values for the patient (2–6) never reached the level of a high responder (≥5 BU/mL), and did not show any increasing trend throughout the treatment period. This patient had 4 bleeds requiring episodic FVIII treatment. All bleeds occurred after the first positive inhibitor testing, but were successfully treated with FVIII agents, the dose of which (average amount per bleed: 36.4 IU/kg) was lower than that used in the pre‐emicizumab period (average amount per bleed: 66.5 IU/kg).

Figure 1.

Individual time courses of factor VIII inhibitor titre

Breakthrough bleeds during emicizumab prophylaxis were successfully managed with episodic treatment with either FVIII or BPAs without any related safety events reported. The FVIII dose per administration did not change after the guidance was issued (Table 1): the median (range) was 28.9 (12.3–41.6) IU/kg in the pre‐guidance period and 27.8 (16.3–41.6) IU/kg in the post‐guidance period. The aPCC and rFVIIa doses per administration decreased: the medians (range) in the pre‐ and post‐guidance periods were 84.0 (72.5–101.4) U/kg and 43.5 (38.5–43.5) U/kg for aPCC and 252.1 (85.7–252.1) μg/kg and 87.0 (49.0–97.5) μg/kg for rFVIIa.

Table 1.

Coagulation factor products required for the treatment of breakthrough bleeds under emicizumab prophylaxis before and after issuing the guidance

| Pre‐guidance | Post‐guidance | |

|---|---|---|

| FVIII | ||

| Number of patients administered more than once | 5 | 3 |

| Number of administrations | 230 | 218 |

| Dose per administration [IU/kg] | 28.9 (12.3–41.6) | 27.8 (16.3–41.6) |

| Number of administrations per bleed | 3 (1–41) | 2 (1–40) |

| Cumulative dose per bleed [IU/kg] | 73.5 (12.3–1184.2) | 65.4 (20.8–1111.1) |

| aPCC | ||

| Number of patients administered more than once | 4 | 2 |

| Number of administrations | 22 | 6 |

| Dose per administrations [U/kg] | 84.0 (72.5–101.4) | 43.5 (38.5–43.5) |

| Number of administrations per bleed | 1 (1–4) | 3 (1–5) |

| Cumulative dose per bleed [U/kg] | 84.0 (72.5–405.8) | 127.9 (38.5–217.4) |

| rFVIIa | ||

| Number of patients administered more than once | 4 | 3 |

| Number of administrations | 54 | 57 |

| Dose per administration [μg/kg] | 252.1 (85.7–252.1) | 87.0 (49.0–97.5) |

| Number of administrations per bleed | 1 (1–4) | 2 (1–54) |

| Cumulative dose per bleed [μg/kg] | 252.1 (85.7–1008.4) | 194.9 (49.0–4695.7) |

Only treatment for bleeding was included. Data are reported as median (min–max).

Abbreviations: aPCC, activated prothrombin complex concentrate; FVIII, factor VIII; rFVIIa, recombinant activated factor VII.

3.3. Efficacy

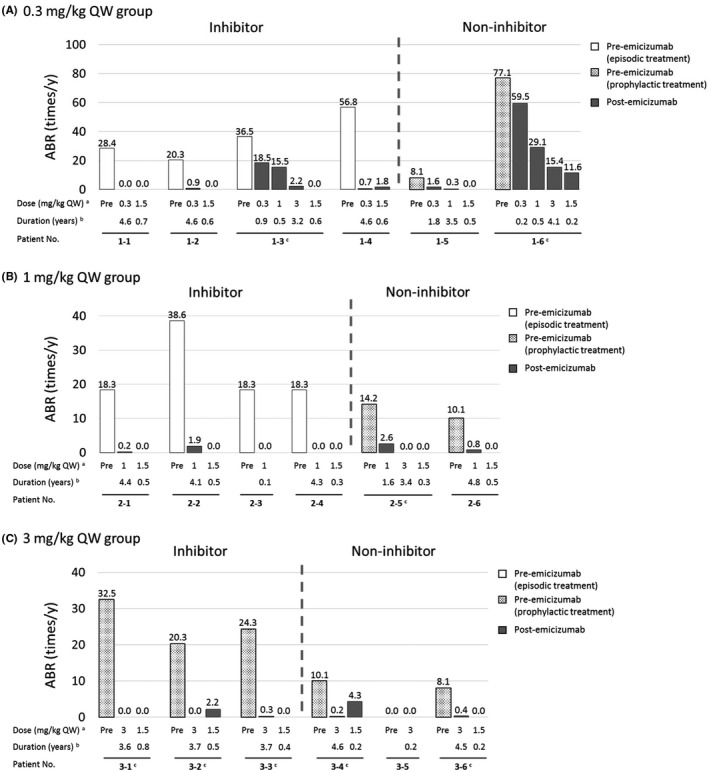

In all patients, ABRs for bleeds treated with coagulation factors during emicizumab prophylaxis decreased from pre‐emicizumab rates or remained zero, regardless of inhibitor status or usage of prior prophylactic treatment (Figure 2). In the 0.3 mg/kg QW group, 3 patients had their doses increased to 1 mg/kg QW, and 2 of the 3 patients had their doses further increased to 3 mg/kg QW. In the 1 mg/kg QW group, 1 patient had his dose increased to 3 mg/kg QW. The medians (ranges) of ABRs for treated bleeds in the periods before and during emicizumab prophylaxis were, respectively, 32.46 (8.1–77.1) and 1.25 (0–59.5) in the 0.3 mg/kg dosing period (N = 6), 18.26 (8.1–77.1) and 0.83 (0–29.1) in the 1 mg/kg dosing period (N = 9), and 20.29 (0–77.1) and 0.22 (0–15.4) in the 3 mg/kg dosing period (N = 9) (Table S1). For treated joint bleeds only, the medians (ranges) of ABRs in the periods before and during emicizumab prophylaxis were, respectively, 27.39 (8.1–69.0) and 0.87 (0–59.5) in the 0.3 mg/kg dosing period (N = 6), 16.23 (8.1–69.0) and 0.41 (0–27.0) in the 1 mg/kg dosing period (N = 9), and 12.17 (0–69.0) and 0 (0–14.4) in the 3 mg/kg dosing period (N = 9). The median ABRs for treated muscle and subcutaneous bleeds were zero in all dosing periods. Out of 8 the patients who decreased their doses from 3 to 1.5 mg/kg, ABRs for treated bleeds decreased in 4, remained at zero in 2 and increased in 2. The 2 patients with increased ABRs each had 1 traumatic treated bleed in the 1.5 mg/kg dosing period. One patient (1–6) without FVIII inhibitors with FVIII prophylaxis before enrolment had an unusually large number of bleeding episodes, whose majority was at joints, probably due to very high levels of physical activities and haemophilic arthropathy. 18

Figure 2.

Individual annualized bleeding rates for treated bleeds in the periods before and during emicizumab prophylaxis. ABR, annualized bleeding rate; QW, every week.aOrder of dose administered in each patient was indicated from left to right below the corresponding data bars.bDuration of pre‐emicizumab was 0.5 years for all patients.cPatients who decreased their doses from 3 to 1.5 mg/kg QW

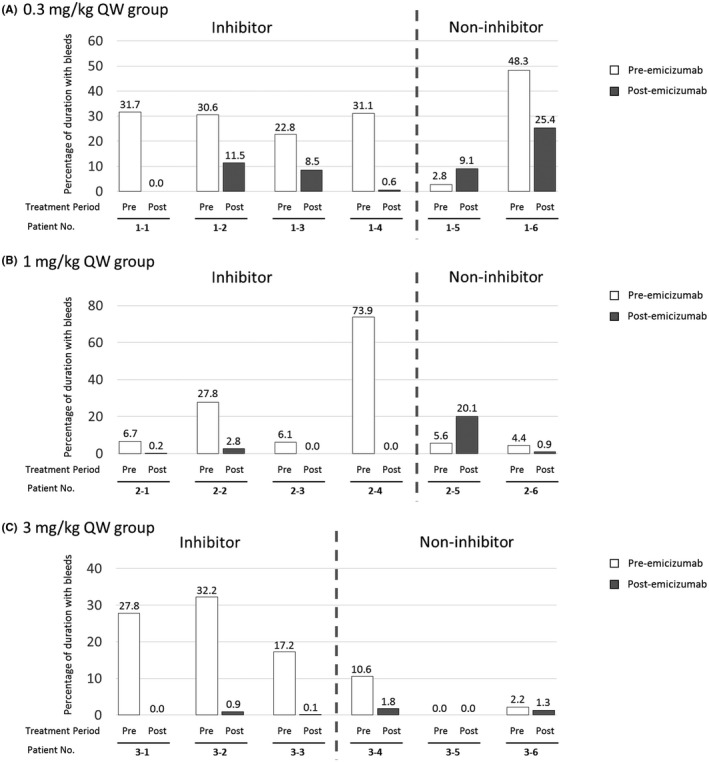

Total time spent with bleeding symptoms decreased from the pre‐emicizumab period in all patients except 2 patients without inhibitors: 2.8% (5/180 days) to 9.1% (192/2104 days) in one patient (1–5), and 5.6% (10/180 days) to 20.1% (388/1930 days) in the other patient (2–5) despite their decreased ABRs (Figure 3). In the former patient, the majority of time spent with bleeding symptoms (129/192 days) was in the 0.3 mg/kg dosing period (671 days), and the rest (63/192 days) was in the 1 mg/kg dosing period (1263 days), and there was no time spent with bleeding symptoms in the 1.5 mg/kg dosing period (170 days). The longest‐lasting symptom (94 days) this patient experienced was associated with gastrointestinal bleeding followed by epistaxis. In the latter patient, the total time spent with bleeding symptoms was 388 days, and all treated bleeds occurred in the 1 mg/kg dosing period (567 days). No treated bleeds occurred in the 3 mg/kg (1253 days) or 1.5 mg/kg (110 days) dosing period. The longest‐lasting symptom (353/388 days) this patient experienced was associated with mesenteric haematoma.

Figure 3.

Proportion of total time spent with symptoms associated with treated bleeds to the total observation period. QW, every week. Duration of pre‐emicizumab was 0.5 years for all patients. For bleeding that was continuing until the end date of the study, the end date of bleeding was imputed with the end date of the study

In line with the decreased ABRs and total time spent with bleeding symptoms, annualized consumption of all coagulation factors for episodic treatment decreased from the pre‐emicizumab period in all patients, regardless of whether before or after issuing the guidance (Figure S1).

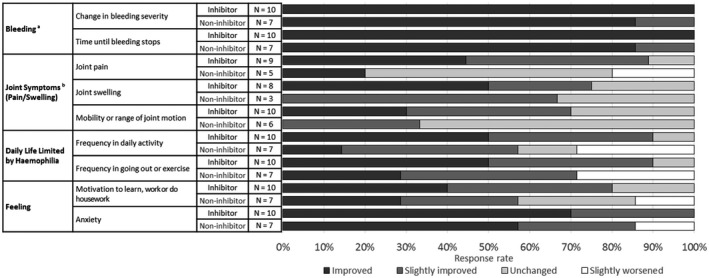

3.4. Patients’ perceptions

Seventeen patients recorded their perceptions on an original questionnaire 1 to 5 times (Appendix S1), and their responses on the first questionnaire are summarized in Figure 4. All patients answered ‘improved’ for bleeding severity and time until bleeding stops, except 1 patient answering ‘slightly improved’. All patients answered ‘improved’, ‘slightly improved’ or ‘unchanged’ for joint symptoms (joint pain, joint swelling, and mobility or range of joint motion) except 1 patient answering ‘slightly worsened’ for joint pain. The majority of patients answered ‘improved’ or ‘slightly improved’ for daily life (frequency or amount of daily activities and frequency of going out or exercising) and feelings (motivation to learn, work or do housework, and anxiety); in particular, all patients except 1 answered ‘improved’ or ‘slightly improved’ for anxiety. Two patients gave negative answers for some items. One patient (1–6) answered ‘slightly worsened’ for joint pain, daily life and feelings in the 0.3 mg/kg dosing period, but all these answers were improved after up‐titration to 3 mg/kg QW. The other patient (2–5) answered ‘slightly worsened’ for daily life, which was due to reduced frequency of exercise by quitting his club activity. Four families of patients with inhibitors answered the questionnaire as well. All of them answered ‘improved’ or ‘slightly improved’ for all items except for 1 family answering ‘unchanged’ for joint pain and swelling (Figure S2). Three patients (1–3, 1–5 and 1–6) answered questions about changes after up‐titration due to sub‐optimal bleeding control, and all of those patients answered ‘improved’ or ‘slightly improved’ at some time points in all items (Appendix S1).

Figure 4.

Response rate of perception questionnaire by patients (the first answer). a‘No bleeding’ and ‘Improved’ were grouped together as ‘Improved’. bPatients without symptoms or who did not answer this question are not included.

4. DISCUSSION

In the phase 1 study and phase 1/2 extension study, there were no safety concerns with emicizumab for up to 5.8 years; most AEs were mild and unrelated to emicizumab. ABRs for treated bleeds decreased from the pre‐emicizumab period or remained zero in all patients. After changing their doses from 3 to 1.5 mg/kg, ABRs decreased or maintained in most patients. Robust evaluation of the long‐term effect on ABRs would be difficult since ABRs can be affected by dose modification. However, a gradual downward trend on ABRs over about 2 years was reported in phase 3 studies, 20 which supported the validity of our finding of the long‐term effect.

The total time spent with bleeding symptoms decreased from the pre‐emicizumab period in all patients except 2, indicating change in bleeding phenotype by emicizumab prophylaxis. In addition to the conventional assessment of bleeding frequency, collection of the timing of onset and resolution data of bleeding symptoms enabled us to capture additional characteristics of the disease together with the potential of emicizumab. Self‐reported perceptions of patients and their families also supported the favourable characteristics of emicizumab prophylaxis. Patients felt that the disease phenotype changed to a milder one, that the time until bleeding stopped was shortened, and that their daily lives and feelings were improved. Their families, too, were aware of the positive effects on bleeding symptoms, joint symptoms, daily life and feelings. Even the 2 patients whose total time spent with bleeding symptoms increased, reported improvement of symptoms and feelings in their responses on the questionnaire. Taken together, improving disease conditions, both in the quantity and quality of bleeding, might motivate patients to participate more in social activities than before emicizumab administration and relieve them from some of the psychological burden associated with haemophilia A.

The decreasing trend seen in FVIII inhibitor titres over time may be due to reduced use of aPCC involving trace amounts of FVIII 21 for breakthrough bleeds; annualized consumption of aPCC for episodic treatment decreased from the pre‐emicizumab period in all using patients. A transient spike in FVIII inhibitor titres in 1 patient with inhibitors might be attributed to repeated administrations of aPCC. Two patients without inhibitors at baseline tested positive for inhibitors (transient in 1 patient, and sustained with low titres in the other patient) after starting emicizumab prophylaxis. Given the fact that emicizumab shares no structural homology with FVIII, the emergence of inhibitors would not be caused by emicizumab prophylaxis. This may be related to the fact that low‐titre inhibitors are often known to be false positive. 22 Importantly, the titre values were considered not clinically relevant in the patient with sustained low titres, since breakthrough bleeds were successfully managed with FVIII, the dose of which was lower than that used in the pre‐emicizumab period. For patients with low‐titre inhibitors receiving emicizumab, FVIII may be an effective episodic treatment option in case of major bleeding in an emergency situation. 23 However, there are uncertainties with this potential treatment strategy since the FVIII inhibitor titre could spike in response to being exposed to FVIII.

The main limitations to this study include the small number of patients and the open‐label, non‐randomized study design, which make it difficult to draw robust conclusions. The method of collecting bleeding and treatment data in these studies does not conform to current standard practice, since these studies were initiated before issuing the standardized definition of a bleed advocated by the International Society on Thrombosis and Hemostasis. 24 Pre‐emicizumab ABRs based on data collected retrospectively may induce a bias for intra‐patient comparisons. The interpretation of perception from the questionnaire is limited since it is voluntarily reported and not enough validated.

5. CONCLUSION

This study showed the remarkable efficacy and favourable safety of emicizumab prophylaxis for up to 5.8 years in patients with severe haemophilia A, and highlights the potential of emicizumab prophylaxis to improve both in the quantity and quality of patients’ bleeding symptoms, daily lives and feelings.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

This study was sponsored by Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., M. Shima received research funding from Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., F. Hoffmann‐La Roche Ltd., Bioverativ Inc., Shire Plc, CSL Behring, KM Biologics Co., Ltd. and Novo Nordisk A/S; and consulting fee from Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.; and payment for lectures on speaker's bureau from Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Bioverativ Inc., Bayer AG and Sysmex corporation; and is listed as an entity's board of directors or advisory committee member for Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., F. Hoffmann‐La Roche Ltd., BioMarin Pharmaceutical Inc., Bayer AG and Sanofi S.A.; and is an inventor of patents related to anti‐FIXa/FX bispecific antibodies. A. Nagao received research funding from Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. and Bayer AG; and consulting fee and payment for lectures on speaker's bureau from Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Sanofi S.A. Bayer AG, Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. and CSL Behring. M. Taki received research funding from Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., F. Hoffmann‐La Roche Ltd., Bioverativ Inc., CSL Behring and Novo Nordisk A/S; and payment for lectures on speaker's bureau from Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., CSL Behring, Bayer AG, Shire Plc, Bioverativ Inc. and Novo Nordisk A/S; and is listed as an entity's board of directors or advisory committee member for Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Novo Nordisk A/S, Bioverativ Inc. and Bayer AG. T. Matsushita is listed as an entity's board of directors or advisory committee member for Baxalta Inc., Shire Plc, Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Bayer AG, Novo Nordisk A/S, Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. and Pfizer Inc.; and received educational and investigational fee from Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. and Novo Nordisk A/S. K. Oshida received research funding from Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. and F. Hoffmann‐La Roche Ltd.; and payment for lectures on speaker's bureau from Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. and Novo Nordisk A/S. K. Amano received research funding from Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., F. Hoffmann‐La Roche Ltd. and KM Biologics Co., Ltd.; and consulting fee from Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.; and payment for lectures on speaker's bureau from Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Sanofi S.A., Bayer AG, Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Novo Nordisk A/S, CSL Behring, KM Biologics Co., Ltd., Pfizer Inc. and Japan Blood Products Organization; and is listed as an entity's board of directors or advisory committee member for Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., S. Nagami is an employee of Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.; and holds stock in Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.; and is an inventor of patents related to anti‐FIXa/FX bispecific antibodies. N. Okada is an employee of Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., S. Maisawa is an employee of Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., K. Nogami received research funding from Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., F. Hoffmann‐La Roche Ltd., Shire Plc, Bioverativ Inc., Novo Nordisk A/S and Bayer AG; and consulting fee from Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.; and payment for lectures on speaker's bureau from Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Shire Plc, Bioverativ Inc., Novo Nordisk A/S and Bayer AG; and is listed as an entity's board of directors or advisory committee member for Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. and F. Hoffmann‐La Roche Ltd.; and is an inventor of patents related to anti‐FIXa/FX bispecific antibodies.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

M. Shima, S. Nagami and S. Maisawa designed the study, interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript. A. Nagao, M. Taki, T. Matsushita, K. Oshida, K. Amano and K. Nogami collected and interpreted the data. N. Okada analysed and interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript.

Supporting information

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank all patients and their family members; Dr. Hoyu Takahashi at Niigata Prefectural Kamo Hospital; investigators and staff at participating medical institutions; and colleagues at Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., especially Yuki Sato, Ryu Kasai, Koichiro Yoneyama, Naoki Kotani and Takashi Funatogawa.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Qualified researchers may request access to individual patient‐level data through the clinical study data request platform (www.clinicalstudydatarequest.com). For further details on Chugai's Data Sharing Policy and how to request access to related clinical study documents, see www.chugai-pharm.co.jp/english/profile/rd/ctds_request.html

REFERENCES

- 1. Srivastava A, Brewer AK, Mauser‐Bunschoten EP, et al. Guidelines for the management of hemophilia. Haemophilia. 2013;19:e1‐e47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Valentino LA, Mamonov V, Hellmann A, et al. Prophylaxis Study Group. A randomized comparison of two prophylaxis regimens and a paired comparison of on‐demand and prophylaxis treatments in hemophilia A management. J Thromb Haemost. 2012;10:359‐367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mahlangu J, Powell JS, Ragni MV, et al. Phase 3 study of recombinant factor VIII Fc fusion protein in severe hemophilia A. Blood. 2014;123:317‐325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Warren BB, Thornhill D, Stein J, et al. Early prophylaxis provides continued joint protection in severe hemophilia A: Results of the Joint Outcome Continuation Study. Blood. 2018;132(Suppl 1):382. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fischer K, Lewandowski D, Marijke van den Berg H, Janssen MP. Validity of assessing inhibitor development in haemophilia PUPs using registry data: the EUHASS project. Haemophilia. 2012;18:e241‐e246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Peyvandi F, Mannucci PM, Garagiola I, et al. A Randomized trial of factor VIII and neutralizing antibodies in hemophilia A. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:2054‐2064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Morfini M, Haya S, Tagariello G, et al. European study on orthopaedic status of haemophilia patients with inhibitors. Haemophilia. 2007;13:606‐612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Walsh CE, Soucie JM, Miller CH. United States Hemophilia Treatment Center Network. Impact of inhibitors on hemophilia A mortality in the United States. Am J Hematol. 2015;90:400‐405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Antunes SV, Tangada S, Stasyshyn O, et al. Randomized comparison of prophylaxis and on demand regimens with FEIBA NF in the treatment of haemophilia A and B with inhibitors. Haemophilia. 2014;20:65‐72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Konkle BA, Ebbesen LS, Erhardtsen E, et al. Randomized, prospective clinical trial of recombinant factor VIIa for secondary prophylaxis in hemophilia patients with inhibitors. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5:1904‐1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kitazawa T, Esaki K, Tachibana T, et al. Factor VIIIa‐mimetic cofactor activity of a bispecific antibody to factors IX/IXa and X/Xa, emicizumab, depends on its ability to bridge the antigens. Thromb Haemost. 2017;117:1348‐1357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Oldenburg J, Mahlangu JN, Kim B, et al. Emicizumab prophylaxis in hemophilia A with inhibitors. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:809‐818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mahlangu J, Oldenburg J, Paz‐Priel I, et al. Emicizumab prophylaxis in patients who have hemophilia A without inhibitors. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:811‐822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pipe SW, Shima M, Lehle M, et al. Efficacy, safety, and pharmacokinetics of emicizumab prophylaxis given every 4 weeks in people with haemophilia A (HAVEN 4): a multicentre, open‐label, non‐randomised phase 3 study. Lancet Haematol. 2019;6:e295‐305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Young G, Liesner R, Chang T, et al. A multicenter, open‐label phase 3 study of emicizumab prophylaxis in children with hemophilia A with inhibitors. Blood. 2019;134:2127‐2138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Shima M, Nogami K, Nagami S, et al. A multicentre, open‐label study of emicizumab given every 2 or 4 weeks in children with severe haemophilia A without inhibitors. Haemophilia. 2019;25:979‐987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Shima M, Hanabusa H, Taki M, et al. Factor VIII‐mimetic function of humanized bispecific antibody in hemophilia A. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:2044‐2053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shima M, Hanabusa H, Taki M, et al. Long‐term safety and efficacy of emicizumab in a phase 1/2 study in hemophilia A patients with or without inhibitors. Blood Advances. 2017;1:1891‐1899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nogami K, Soeda T, Matsumoto T, et al. Routine measurements of factor VIII activity and inhibitor titer in the presence of emicizumab utilizing anti‐idiotype monoclonal antibodies. J Thromb Haemost. 2018;16:1383‐1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Callaghan M, Negrier C, Paz‐Priel I, et al. Emicizumab treatment is efficacious and well tolerated long term in persons with haemophilia A (PwHA) with or without FVIII inhibitors: Pooled data from four HAVEN studies. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2019;3(Suppl 1):116. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gomperts ED. FEIBA safety and tolerability profile. Haemophilia. 2006;12(Suppl 5):14‐19. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Miller CH, Rice AS, Boylan B, et al. Characteristics of hemophilia patients with factor VIII inhibitors detected by prospective screening. Am J Hematol. 2015;90:871‐876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chou SC, Nagami S, Lin SW, Tien HF. Successful management with a major trauma caused by vehicle accident in a severe hemophilia A patient with inhibitor under emicizumab treatment. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2019;3(Suppl 1):422. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Blanchette VS, Key NS, Ljung LR, et al. Subcommittee on Factor VIII, Factor IX and Rare Coagulation Disorders of the Scientific and Standardization Committee of the International Society on Thrombosis and Hemostasis. Definitions in hemophilia: communication from the SSC of the ISTH. J Thromb Haemost. 2014;12:1935‐1939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material

Data Availability Statement

Qualified researchers may request access to individual patient‐level data through the clinical study data request platform (www.clinicalstudydatarequest.com). For further details on Chugai's Data Sharing Policy and how to request access to related clinical study documents, see www.chugai-pharm.co.jp/english/profile/rd/ctds_request.html