Abstract

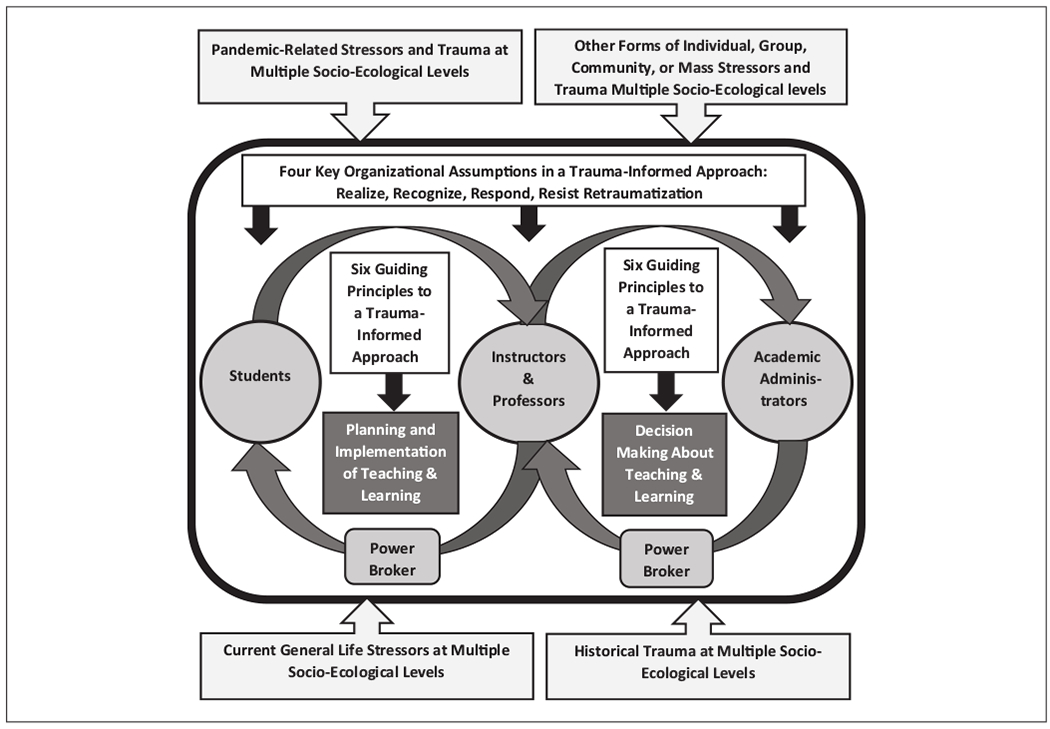

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) realities have demanded that educators move swiftly to adopt new ways of teaching, advising, and mentoring. We suggest the centering of a trauma-informed approach to education and academic administration during the COVID-19 pandemic using the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s (SAMHSA) guidance on trauma-informed approaches to care. In our model for trauma-informed education and administration (M-TIEA), SAMHSA’s four key organizational assumptions are foundational, including a realization about trauma and its wide-ranging effects; a recognition of the basic signs and symptoms of trauma; a response that involves fully integrating knowledge into programs, policies, and practices; and an active process for resisting retraumatization. Since educators during the pandemic must follow new restrictions regarding how they teach, we have expanded the practice of teaching in M-TIEA to include both academic administrators’ decision making about teaching, and educators’ planning and implementation of teaching. In M-TIEA, SAMHSA’s six guiding principles for a trauma-informed approach are infused into these two interrelated teaching processes, and include the following: safety; trustworthiness and transparency; peer support; collaboration and mutuality; empowerment, voice, and choice; and cultural, historical, and gender issues. M-TIEA’s organizational assumptions, processes, and principles are situated within an outer context that acknowledges the potential influences of four types of intersectional traumas and stressors that may occur at multiple socioecological levels: pandemic-related trauma and stressors; other forms of individual, group, community, or mass trauma and stressors; historical trauma; and current general life stressors. This acknowledges that all trauma-informed work is dynamic and may be influenced by contextual factors.

Keywords: COVID-19, model, trauma, trauma-informed teaching

Overview: Trauma-Informed Education and Administration

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) realities demand that educators move swiftly to adopt new ways of teaching, advising, and mentoring their students. This has been documented in numerous blogs, university guidance, and articles about emergency remote learning, online learning, and pandemic pedagogy. While the focus on pedagogy, structure, and format of our teaching has been dominant in this regard, we suggest centering a trauma-informed approach to education and administration during public health emergencies such as the current COVID-19 pandemic. While various models of trauma-informed care exist (Muskett, 2014; Reeves, 2015), we recommend the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s (SAMHSA) six principles for a trauma-informed approach (SAMHSA, 2014a).

Adopting a trauma-informed approach to care and service delivery during a public health emergency, and the use of SAMHSA’s principles, is in alignment with guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) Office of Public Health Preparedness and Response (CDC, 2018). Since we as educators are experiencing the multifaceted traumatic sequelae of the pandemic along with our students, a trauma-informed approach should be applied not only to our interactions with students but also to the interactions between frontline educators and those in administrative positions who are making decisions about how public health education will take place during the pandemic. Administrators possess power over educators, much in the same way that educators possess power over students. The focus on a trauma-informed approach is especially important in the field of health promotion, as many of us are not only examining pandemic-related issues in our classrooms but also engaging in health promotion practices in community.

While the incorporation of trauma-informed principles into health promotion practice is common (Freed & SmithBattle, 2016; Harper et al., 2015), its prominence in discourse about health promotion pedagogy is less common. Carello and Butler (2014) have recommended the use of a trauma-informed approach to pedagogy in all higher education courses, especially those that teach traumatic content and use traumatic materials in lectures and assignments. They encourage educators to recognize the potential risk of secondary traumatization and retraumatization in our courses and to prioritize student safety. In a recent commentary in the American Journal of Public Health about COVID-19-related changes in public health education, Abuelezam (2020) also urges educators to ensure that our pedagogical approaches do not retraumatize students as they are attempting to heal from the trauma of COVID-19, stating that “public health professors must develop discipline-specific tools to make this (a trauma-informed approach) a priority for all public health classrooms (Abuelezam, 2020, p. 976).

SAMHSA’s (2014a) guidance on implementing a trauma-informed approach emphasizes that in addition to trauma-informed services or interventions, it is also critical to incorporate key trauma principles into the organizational culture of the entity that is utilizing a trauma-informed approach. Thus, we suggest that in addition to trauma-informed pedagogy in the classroom, universities expand trauma-informed approaches to their institutional ecosystems and decision-making processes. Although this combination of trauma-informed practice/pedagogy and organizational culture shift has not been explored in university settings, its importance has been well documented in trauma-informed approaches to education for primary and secondary schools (Kataoka et al., 2018; Oehlberg, 2008; Thomas et al., 2019).

Author Perspective

As educators and collaborators, we have been engaged in vibrant dialogue, critical self-reflection, and collaborative inquiry for the past two decades (Bray et al., 2000; Brookfield, 2000; Neubauer, 2013). We investigate and challenge our own hegemonic assumptions about our teaching successes, our failures, and our journeys as lifelong learners, unlearners, and educators. Since March of 2020, our critical dialogues have centered on our students, the implications of our teaching and learning actions, and our roles in education-related decisions during this pandemic. We are also acutely aware of the pandemic realities in our own families and communities across the globe, and the ways in which this pandemic has disproportionately affected those who are already burdened with health inequities. We have developed this model as an extension of our formal training, professional experiences, values, and beliefs as educators and educational leaders. As a clinical psychologist and social epidemiologist (Harper) and critical adult educator and evaluator (Neubauer), our intent is to raise the visibility of the need to center trauma-informed approaches in our work and discuss power in our classrooms and universities.

Centering Trauma in Health Promotion Education During a Pandemic

In this article, we introduce a model that positions trauma-informed approaches to teaching and administration within the context of four types of intersectional traumas and stressors that can occur at multiple socio-ecological levels: pandemic-related trauma and stressors; other forms of individual, group, community, or mass trauma and stressors; historical trauma; and current general life stressors (see Figure 1). The model links the four key organizational assumptions in a trauma-informed approach with the six guiding principles (SAMHSA, 2014a, 2014b). We suggest that the application of this model will increase faculty and student awareness of the impact that pandemic-related trauma can have in our classrooms and on our campuses. We detail various components of the model and discuss implications for consideration in the classroom and in curricular decision making.

Figure 1. Model for trauma-informed education and administration.

Note. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s six guiding principles of trauma-informed care are not linear practices or procedures but instead are principles that should be applied in a setting-specific manner. They include the following: safety; trustworthiness and transparency; peer support; collaboration and mutuality; empowerment, voice, and choice; and cultural, historical, and gender issues.

Throughout our model we utilize the conceptualization of a “stressor” as proposed in the transactional model of stress and coping (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984), and the conceptualization of “trauma” as proposed by the SAMHSA guidance on trauma-informed approaches (SAMHSA, 2014a). These are two interrelated concepts that have shared core assumptions. In both, the reactions and negative effects that people experience because of exposure to a particular stressor or stimulus (e.g., event, interaction, experience) are based on one’s appraisal or evaluation of the stimulus (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984,1987; SAMHSA, 2014a). The transactional model suggests that we go through two stages of appraisal before having a reaction—with the primary appraisal focused on evaluating the potential for threat from the stimulus and the secondary appraisal focused on our ability to utilize resources to cope with any stimuli we appraise as a potential threat (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984, 1987). The SAMHSA (2014a) definition of trauma is based on systematic reviews of research with consultation from providers, researchers, and trauma survivors and has related elements.

Trauma results from an event, series of events, or set of circumstances that is experienced by an individual as physically or emotionally harmful or threatening and that has lasting adverse effects on the individual’s functioning and physical, social, emotional, or spiritual well-being. (p 7)

SAMHSA’s (2014a) definition emphasizes that there are three essential elements to consider in understanding trauma (the 3 Es), the nature of the event, how one experiences the event, and the adverse effects of the event. Traumatic events and experiences are always stressful, but stressors do not always raise to the level of trauma.

Even though we are all living in a point in history dominated by the threat of the COVID-19 pandemic, each of us will experience and appraise the pandemic differently, based on factors such as cultural beliefs, past experiences, social connectedness, developmental stage, and the degree of power one possesses (Engelbrecht & Jobson, 2014; Gómez de La Cuesta et al., 2019; Mitchell et al., 2017). A recent rapid literature review and meta-analysis of studies documenting posttraumatic stress and general psychological distress symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic in six countries clearly demonstrate elevated levels of both posttraumatic and psychological stress associated with COVID-19 (Cooke et al., 2020). Recent data collected between March and May 2020 demonstrate that adults age 18 years and older in the United States report higher levels of mental health concerns and more negative economic consequences from COVID-19 than adults living in nine other high-income countries (Tanne, 2020; Williams et al., 2020). Data from a nationally representative sample of adults ages 18 to 35 years in the United States conducted in April 2020 demonstrated elevated levels of loneliness (as compared to prior data), with higher levels of loneliness being associated with higher levels of clinically significant depression and suicidal ideation (Killgore et al., 2020). Thus, in alignment with the SAMHSA definition of trauma, COVID-19 presents a unique and unprecedented traumatic event in all of our lives, and there is mounting evidence that many people are experiencing it as a form of trauma and suffering adverse effects (cf, Cooke et al., 2020; Killgore et al., 2020; Ran et al., 2020; Ruiz & Gibson, 2020; Williams et al., 2020). But given the nature of trauma, each of us will have different adverse effects (if any), and those may occur immediately or later, last for varying amounts of time, and have varying degrees of severity. No two people will react the same way to traumatic events, so we cannot predict how we, our colleagues, and our students will react to COVID-19. In addition, given the uniqueness, longevity, severity, and complete social disruption associated with the COVID-19 pandemic, there is no way to know about the true extent of the psychological impact this will have on all of us in the future.

How Trauma Influences Administrators, Educators, and Students

There are a range of potential adverse effects from trauma including cognitive, emotional, and physiological reactions (SAMHSA, 2014b; Shepherd & Wild, 2014), but the two most noteworthy with regard to how administrators, professors/instructors, and students function in an academic unit are disruptions in cognitive processes and thought patterns. With regard to cognitive processes, traumatic stress can lead to challenges with memory, concentration, attention, planning, decision making, creativity, and learning (Burriss et al., 2008; Colvonen et al., 2019; Kaplan et al., 2016). Many of these are aspects of executive functioning that are regulated by the prefrontal cortex, one of the primary areas of the brain influenced by traumatic stress and the area of the brain that is not fully developed until the early to mid 20s (Caballero et al., 2016; Nyongesa et al., 2019). During times of trauma, educators need to be careful not to interpret challenges in these areas as resistance to learning, since they may be due to a traumatic stress response. Administrators and educators also need to keep in mind that we are all experiencing some level of collective trauma during the pandemic and that this will affect our ability to lead and teach at our full capacity.

In addition, increases in negative thought patterns can occur in reaction to traumatic stress, including thoughts about the self, the world, and the future (known as the cognitive triad; Beck et al., 1979). Trauma can lead individuals to see themselves as incompetent and worthless, to question their skills and abilities, to see other people and the world as unsafe and unpredictable, and to see their future as hopeless (Grills-Taquechel et al., 2011; Mancini et al., 2011; SAMHSA, 2014b). In addition, those who experience trauma may experience negative intrusive thoughts, and lack awareness that such intrusive trauma-related thoughts are occurring (Green et al., 2016; Takarangi et al., 2014). These negative thought patterns and intrusive thoughts may be associated with poorer mental health outcomes (Brooks et al., 2019; Mancini et al., 2011) and may interfere with students’ ability to focus and learn. Given the lack of meta-awareness of intrusive trauma-related thoughts (Green et al., 2016), such negative thought patterns may appear in written assignments such as reflection papers or journals. Such thoughts should be acknowledged and normalized, and appropriate referrals made when there is a suggestion of severe mental health issues.

Administrators and educators also may experience these negative thoughts, which may impair our ability to fulfill all our responsibilities. Junior faculty members, untenured faculty members, and others whose positions are not guaranteed may be particularly vulnerable to these negative thoughts. Those in positions of power should do their most to assure these educators (to the extent possible) that their work is valued and that all measures will be taken to secure their positions.

Unique Circumstances in Deploying a Trauma-Informed Approach to University-Based Education

Trauma-informed frameworks were developed to be implemented by professionals working with individuals who experience trauma (SAMHSA, 2014a, 2014b). Clients typically have an underlying assumption that the professionals delivering such services are not currently experiencing the same trauma as the client, although they may have experienced trauma in the past. COVID-19 is unique in that we are all experiencing the trauma of living, working, and learning during a pandemic, and thus those who are responsible for delivering trauma-informed educational activities are simultaneously experiencing the same or similar COVID-specific stressors and trauma, as well as other general stressors and trauma.

Unfortunately, the COVID-19 pandemic has negative characteristics associated with both disasters caused by nature and those caused by people (SAMHSA, 2014b; Shamai, 2015). With COVID-19 we are seeing a chain reaction of additional trauma and stressors such as unemployment, scarcity of food, lack of critical medical supplies, and health care workforce exhaustion. This is similar to the radiating and long-term traumas experienced by residents in natural disaster zones, such as with the residents of Louisiana after Hurricane Katrina (LaJoie et al., 2010). In both situations, members of society who are already experiencing social and health inequities often bear the greatest burden with these chain reaction traumas. With COVID-19, CDC data suggest that Black populations in the United States are disproportionately affected (CDC, 2020; Garg et al., 2020), and early evidence shows that unemployment rates are increasing for Black Americans but decreasing for White Americans (Burns, 2020; Gould & Wilson, 2020). This chain reaction of stressors and trauma can also result in more mental health challenges since survivors, first responders, health care professionals, and disaster relief organizations do not have time to process the initial trauma before another occurs (Greenberg et al., 2020; Lai et al., 2020; Torales et al., 2020).

The COVID-19 pandemic also shares some elements with disasters caused by people, such as terrorist acts like 9/11, in that they lead to hypervigilance, hyperarousal, and avoidance among individuals who view themselves as at risk of experiencing a similar traumatic event (Bossini et al., 2016; SAMHSA, 2014b; Shamai, 2015). This can be exacerbated by uncertainty as to when the threat will no longer be present. Over time continued hypervigilance, hyperarousal, and avoidance can result in disruptions to daily functioning, sleep disruptions, exhaustion, as well as subsequent mental and physical health effects including posttraumatic stress disorder (Bossini et al., 2016; Paz García-Vera et al., 2016; Pozza et al., 2019). Unlike trauma related to terrorist attacks, the “common enemy” that causes such disruption is not a person or group of people but instead a virus.

Model for Trauma-Informed Education and Administration

Our model for trauma-informed education and administration (M-TIEA) provides guidance for implementing a trauma-informed approach to education and administration that involves active engagement and participation from the organizational unit where the health promotion educational program lies (e.g., school, college, division), as well as the academic administrators (e.g., deans, chairs, division heads) and frontline educators (e.g., instructors, professors, teaching staff members). In alignment with SAMHSA’s (2014a) guidance for a trauma-informed approach, there must be trauma-informed changes that occur at the level of the organization or system, and at the level of practice, which in this case is teaching and learning. At the organizational level, SAMHSA (2014a) recommends that four key organizational assumptions be met in order to truly enact a trauma-informed approach to practice (i.e., teaching), including a realization about trauma and its wide-ranging effects; a recognition of the basic signs and symptoms of trauma; a response that involves fully integrating knowledge into programs, policies, and practices; and an active process for resisting retraumatization. In our model these are necessary conditions that exist within the academic organizational system (represented by the open rectangle), and these influence the process of teaching and learning.

Attention to power, politics, and individual and collective interests is core to this model. Given that educators during the COVID-19 pandemic must follow new restrictions and limitations regarding how they teach (imposed by public health recommendations and emerging COVID-19 university policies), we have expanded the practice of teaching and learning to include both (a) academic administrators’ decision making about teaching and learning practice and (b) educators’ planning and implementation of teaching and learning practice. These represent two interrelated processes (decision making and planning and implementation), and each involves its own bidirectional relationship between two categories of actors. In the model we indicate which actor is the power broker in these two sets of relationships (a) between academic administrators (power broker) and educators and (b) between educators (power broker) and students. We use the term power broker to convey attention to power, relationships, and politics. Critical adult educators, Cervero and Wilson (2001) stated that the realities of power in higher education

call for a relational analysis that takes seriously the idea that adult education does not stand above the unequal relations of power that structure the wider systems in society (Apple 1990) [. . . ] we believe that the institutions and practices of adult education not only are structured by these relations but also play a role in reproducing or change them. (p. 3)

While the use of the term broker conveys someone with specific self-interests and other interests, it also demands the explicit attention to naming the “brokers’” stakes and interests and to the fundamental distribution of power and knowledge.

Education does not stand above the unequal relationships of power that structure the wider systems in society, noting that institutions and practices of education are structured by these relationships and interests that converge or diverge. We acknowledge the power broker in these relationships since traumatic events create power differentials where one entity (e.g., person, event, biohazard, or natural disaster) has power over another, often resulting in feelings of powerlessness by the person experiencing the traumatic event. Thus, in a trauma-informed approach to teaching and learning, power brokers need to be willing to either share or relinquish their power in order to fully embrace the six guiding principles for a trauma-informed approach.

In the model, SAMHSA’s six guiding principles for a trauma-informed approach are infused into each of the two interrelated teaching and learning practice processes: administrators’ decision making and educators’ planning and implementation. These six principles include the following: safety; trustworthiness and transparency; peer support; collaboration and mutuality; empowerment, voice, and choice; and cultural, historical, and gender issues. These key principles are not rigidly prescribed linear practices or procedures but instead are principles that should be applied in a setting specific manner.

All of the organizational assumptions, processes, and principles described in this model are situated within an outer context that acknowledges the potential influences of four types of intersectional traumas and stressors that may occur at multiple socioecological levels: pandemic-related trauma and stressors; other forms of individual, group, community, or mass trauma and stressors; historical trauma; and current general life stressors. This is to acknowledge that the trauma-informed assumptions, processes, and principles that are occurring within an organizational academic unit are dynamic and may be influenced (either negatively or positively) by these outer-level contextual factors.

Although not presented in the model, it is important to keep in mind that the actions and activities presented in the model will be influenced by the most current scientific data regarding COVID-19 transmission, testing, prevention, and treatment; as well as COVID-related policies and regulations at the level of the university, city, state, and country. Given the rapidly changing landscape of COVID science and policy, educators who are involved in utilizing our proposed trauma-informed approach to education and administration must inform themselves about the latest scientific findings and follow public health guidelines for the safest educational experiences. It is also up to each educator to decide to what extent they have the ability and agency to attempt to shape COVID-19 policies at multiple socioecological levels, especially when these policies are not in alignment with the latest medical and public health science.

Outer Context of Intersectional Trauma

The traumas and stressors in the outer context portion of our model represent those specific to the pandemic, as well as those related to other social and environmental events and happenings. We acknowledge that the COVID-19 pandemic is a type of trauma and that it also has sparked chain reaction traumas such as unemployment and loss of survival resources, so we use the term pandemic-related trauma and stressors. We also acknowledge that besides COVID-19 there are social and environmental events that may be differently evaluated and appraised as either stressors or trauma, and that such events may influence individuals, groups, communities, or societies in different ways. For instance, the trauma of systemic racism is a mass trauma that is currently influencing all of us in the United States. Recent highly publicized incidents of police brutality toward Black people in the United States have increased public awareness of the pervasive and long-standing nature of racial trauma experienced by Black Americans. For the past 20 years psychologists have identified the reactions of people of color and indigenous individuals to witnessing and experiencing dangerous race-based events, as well as other forms of racial discrimination, as a specific type of racial trauma (Comas-Díaz, 2000; Harrell, 2000). They also have recognized and acknowledged that it differs from other forms of trauma due to prolonged and repeated exposure and reexposure to both individual-level and collective race-based stress and violence (Comas-Díaz et al., 2019; Crowell et al., 2017). Thus, race-based traumatic experiences such as police brutality and other forms of racism represent unique multilayered stressors and traumas that present elements of both current and historical trauma (Bryant-Davis et al., 2017), and should be addressed as critical outer context factors in this model.

Historical trauma, sometimes referred to as generational trauma, is focused on events that were so intense and impactful that they have the power to influence members of a community, culture, or society far beyond those who actually experienced the event. We view historical trauma as another critical contextual factor that will likely differentially influence those who belong to groups who experience current or historical oppression and unjust treatment, such as people of color, sexual and gender minorities, and people with differing abilities. Finally, the outer context recognizes that in addition to the aforementioned outer-level factors, each person has current personal stressors that they experience on a daily basis. These general stressors (e.g., family disruption, financial challenges, health issues) do not disappear in the midst intersectional trauma and may be exacerbated during such times.

Four Key Organizational Assumptions

Just as in the delivery of trauma-informed behavioral health services (SAMHSA, 2014b), the context in which trauma-informed educational programs and services are delivered contributes to the outcomes for students, instructors, and academic administrators. To deliver educational programs from a trauma-informed perspective, the organizational unit that houses the educational services must meet the four key organizational assumptions in a trauma-informed approach as proposed by the SAMHSA (2014a, 2014b). This organizational unit may vary from institution to institution depending on how (de) centralized academic programs and services are across the university.

Realization.

For an academic unit to implement a trauma-informed approach to education, members of that unit across all levels should have a basic realization about trauma and understand its wide-ranging effects on individuals, families, communities, organizations, and society.

Recognize.

Members of the academic unit should also be able to recognize the basic signs of trauma and to understand that these may vary depending on the setting and nature of the trauma, as well as the characteristics and resources of the person experiencing the trauma.

Respond.

Another assumption is that the academic unit will respond to the presence of trauma among its members by applying the principles of a trauma-informed approach to all areas of operation and functioning. This is based on a realization that traumatic events touch all people involved, whether directly or indirectly. In the case of the current pandemic, we are all affected in some way.

Resist Retraumatization.

Finally, a trauma-informed approach seeks to resist retraumatization of all within the academic unit, including students, staff, and faculty. This calls for the academic unit to engage in an intentional process of organizational critical reflection to examine policies, practices, and programs that may inadvertently trigger painful memories or retraumatize members of the academic unit.

Six Guiding Principles

The six guiding principles provide a foundation for a system of beliefs and behaviors that guide interactions with those who experience trauma and should be applied in a setting- or sector-specific manner (SAMHSA, 2014a). They do not represent a specific prescriptive intervention to be delivered in a linear manner but instead represent organizational and individual principles that are enacted to create a safe environment for those who have experienced (or are currently experiencing) trauma (Elliott et al., 2005; Harris & Fallot, 2001; Levenson, 2017). When using a trauma-informed approach, the principles are continually interwoven and applied to interactions with all who are receiving some type of educational or therapeutic services, as well as all who work within the organizational unit (Levenson, 2017). Thus, in our model we recommend that these principles be applied within the system of interactions between students and educators, and within the system of interactions between educators and academic administrators. The majority of research on the application of trauma-informed principles is focused on clinical or therapeutic organizations or entities, with a growing number focused on primary and secondary education schools and school districts (Chafouleas et al., 2016; Kataoka et al., 2018; Thomas et al., 2019). In order to implement and enact these principles within education-focused organizational structures, it is critical to have administrative buy-in and support; professional development for educators, staff members, and administrators; policy and procedural changes at the organizational level; and strong collaboration with mental health professionals (Oehlberg, 2008; Thomas et al., 2019).

Safety.

Power brokers should ensure that students, educators, and administrators feel physically and emotionally safe. This is accomplished by ensuring that all people in the academic unit are free from physical danger, especially potential for infection, and that all interpersonal interactions are conducted in a manner that promotes a sense of emotional safety. Physical and emotional safety need to be defined by those with the least amount of power (e.g., students, educators) and should be created and promoted by those with the most power and decision-making authority (e.g., educators, administrators) in the teaching and learning environment.

Transparency and Trustworthiness.

Power brokers should build trust with students, educators, and administrators through transparent decision making and program/policy implementation. This is accomplished by administrators clearly informing educators, and educators clearly informing students, about how and why certain decisions are made about teaching and learning. They should also share changes to initial plans as soon as possible. This process of continually informing students, educators, and administrators about the critical decisions that influence teaching and learning and “keeping them in the loop” when changes occur helps to build and maintain a sense of trust. This transparency also holds the power brokers accountable for their decisions and actions, since all who are influenced by these decisions are informed throughout the process, thus allowing them to ask questions.

Peer Support.

Power brokers should encourage students, educators, and administrators to build supportive connections with those who have shared lived experiences in order to promote peer support and mutual self-help. Such connections can help to facilitate a sense of safety and hope, and can reduce the need for more formalized professional supportive services. This can be accomplished through the development of student–student, faculty–faculty, and administrator–administrator dyads and small groups where members can share their experiences and learn new strategies for success from each other. Often the shared lived experience in trauma recovery work is a fellow trauma survivor, but in this model a peer represents a person with a shared lived experience within the academic institution. Power differentials should be considered in the creation of these peer support structures since those with lower levels of power may be feel “obligated” to participate in activities and not feel comfortable sharing their lived experiences in the academic unit.

Collaboration and Mutuality.

Power brokers should partner with students and educators and actively work to level power differences. This can be accomplished by power brokers actively collaborating with students and educators to make critical decisions about teaching and learning. For administrators this involves engaging educators in collaborative decision making about how they will deliver their courses, and for educators it involves engaging students in collaborative decision making about course content, teaching modalities, assessment strategies, and deadlines. The power-leveling aspect of this principle involves power brokers sharing their power with others to create higher degrees of mutuality in the teaching and learning space, thereby allowing educators to have more control over their courses and students to have more control over their education.

Empowerment, Voice, and Choice.

Power brokers should promote the empowerment of students, educators, and administrators, and actively work to dismantle programs, policies, and practices that have denied people without power their voice and choice. This can be accomplished by power brokers recognizing and promoting the strengths of educators and students and working to support the resilience processes utilized by these individuals. This is based in an underlying assumption that people, organizations, and communities possess inherent strengths, and the ability to not only survive in times of distress but also thrive. In addition, power brokers need to educate themselves about the myriad ways in which groups of people with less power have been denied access to choice in teaching and learning spaces (and in society in general), and often feel that their voice is not heard in these environments. Power brokers can work to reverse this historical narrative by providing educators and students with a voice in the classroom and choices regarding their education and educational practices. This can also be promoted through the cultivation of self-advocacy skills, as well as self-efficacy related to success in teaching and learning for both educators and students. As administrators and educators we should be the facilitators and strengths-focused supporters of teaching and learning, not the controllers of students’ education.

Cultural, Historical, and Gender Issues.

Power brokers should ensure that their interactions with students, educators, and administrators are sensitive to a range of human diversity elements that may influence such interactions, including (but not exclusive to) cultural, historical, and gender factors. This can be accomplished by requiring that power brokers receive training and guidance in cultural humility, with accompanying critical self-reflection regarding how they can engage in a process of continued quality improvement regarding these issues. The organizational unit, administrators, and educators need to reject past cultural stereotypes and biases, offer access to culturally responsive education and services, support cultural connections for educators and students, recognize and address past historical trauma, and review and revise programs, policies, and practices so they are responsive to the various social identity needs of students, educators, and administrators.

Conclusion

COVID-19 will have a long-lasting influence on institutions of higher education and on the way we teach health promotion and public health (Abuelezam, 2020). We present the M-TIEA to provide guidance to universities and academic programs that wish to approach health promotion education and administration from a trauma-informed perspective. This will require changes to the way we teach health promotion and public health, and will require organizational commitment from academic administrators and university leaders who must be willing to participate in a culture shift and share power. Those with power will need to be committed to SAMHSA’s (2014a) four key organizational assumptions (realize, recognize, respond, and resist retraumatization), and administrators and educators must fully embrace SAMHSA’s (2014a) six guiding principles in order to create trauma-informed educational and administrative environments. All involved in the educational process will benefit from recognizing and addressing outer context factors specific to the pandemic, as well as those related to other social and environmental events and happenings such as current social discourse and activism related to systemic racism and police brutality. Given the ever-evolving nature of scientific knowledge regarding COVID-19 and the implications this has for educational practices at the university level, administrators and educators will need to educate themselves about the latest scientific findings and follow public health guidelines for the safest educational experiences. We also need to be vigilant of and prepared for shifting and sometimes conflictual mandates and policies enacted by governmental leaders.

We contend that the culture shift and power-sharing suggested in the M-TIEA demand a reflective examination of the social function of universities. Critically examining the role that educators and institutions play in shaping the course and nature of this influence is imperative, as well as assuring that trauma-informed approaches to both education and administration permeate all of these processes. Attending to one’s own pedagogical practice demands attention to the social function of universities, what Brookfield (2000) suggests is the “extent to which the field and its workers leave unchallenged dominant cultural values and social systems, in which these practices produces existing patterns of inequity” (p. 33). While the COVID-19 pandemic has challenged us to act quickly in order to provide high-quality education in a time of prolonged crisis, it also provides us with the opportunity to think critically about our pedagogical theories and practice as we prepare for new academic terms, and to examine potential patterns of inequity and bias in our educational activities and decisions.

Teaching and learning are directly related to the ideologies, missions, practices, and policies developed by academic administrators and university leaders. This model invites a renewed consciousness and vigilant attention to the ways in which our health promotion and general public health educational programs can center trauma in an effort to provide safe environments for teaching and learning that are free from retraumatization. COVID-19 has put a spotlight on the range of health inequities that exist in the United States and worldwide, so this is an opportunity for educators in health promotion, and public health in general, to assure that our health promotion pedagogy addresses these inequities through trauma-informed approaches to both education and administration.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Abuelezam NN (2020). Teaching public health will never be the same. American Journal of Public Health, 110(7), 976–977. 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Rush AJ, Shaw BF, & Emery G (1979). Cognitive therapy of depression. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bossini L, Ilaria C, Koukouna D, Caterini C, Olivola M, & Fagiolini A (2016). PTSD in victims of terroristic attacks: A comparison with the impact of other traumatic events on patients’ lives. Psychiatria Polska, 50(5), 907–921. 10.12740/PP/65742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray JN, Lee J, Smith LL, & Yorks L (2000). Collaborative inquiry in practice: Action, reflection, and making meaning. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks M, Graham-Kevan N, Robinson S, & Lowe M (2019). Trauma characteristics and posttraumatic growth: The mediating role of avoidance coping, intrusive thoughts, and social support. Psychological Trauma, 11(2), 232–238. 10.1037/tra0000372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brookfield SD (2000). The concept of critically reflective practice In Wilson A & Hayes E (Eds.), Handbook of adult and continuing education (pp. 33–49). Jossey-Bass [Google Scholar]

- Bryant-Davis T, Adams T, Alejandre A, & Gray AA (2017). The trauma lens of police violence against racial and ethnic minorities. Journal of Social Issues, 73(4), 852–871. 10.1111/josi.12251 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burns K (2020). The unemployment rate improved in May, but left black workers behind. https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2020/6/6/21282611/black-workers-left-behind-unemployment

- Burriss L, Ayers E, Ginsberg J, & Powell D (2008). Learning and memory impairment in PTSD: Relationship to depression. Depression and Anxiety, 25(2), 149–157. 10.1002/da.20291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caballero A, Granberg R, & Tseng KY (2016). Mechanisms contributing to prefrontal cortex maturation during adolescence. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 70, 4–12. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.05.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carello J, & Butler LD (2014). Potentially perilous pedagogies: Teaching trauma is not the same as trauma-informed teaching. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 15(2), 153–168. 10.1080/15299732.2014.867571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018). Infographic: 6 guiding principles to a trauma-informed approach. (2018). https://www.cdc.gov/cpr/infographics/6_principles_trauma_info.htm

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). Health equity considerations racial and ethnic minority groups. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/racial-ethnic-minorities.html

- Cervero RM, & Wilson AL (2001). Power in practice: Adult education and the struggle for knowledge and power in society. Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Chafouleas SM, Johnson AH, Overstreet S, & Santos NM (2016). Toward a blueprint for trauma-informed service delivery in schools. School Mental Health, 8(1), 144–162. 10.1080/15299732.2014.867571 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Colvonen PJ, Straus LD, Acheson D, & Gehrman P (2019). A review of the relationship between emotional learning and memory, sleep, and PTSD. Current Psychiatry Reports, 21(1), 2 10.1007/s11920-019-0987-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comas-Díaz L (2000). An ethnopolitical approach to working with people of color. American Psychologist, 55(11), 1319–1325. 10.1037/0003-066X.55.11.1319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comas-Díaz L, Hall GN, & Neville HA (2019). Racial trauma: Theory, research, and healing: Introduction to the special issue. American Psychologist, 74(1), 1–5. 10.1037/amp0000442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke JE, Eirich R, Racine N, & Madigan S (2020). Prevalence of posttraumatic and general psychological stress during COVID-19: A rapid review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Research, 292, 113347 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowell C, Mosley D, Falconer J, Faloughi R, Singh A, Stevens-Watkins D, & Cokley K (2017). Black lives matter: A call to action for counseling psychology leaders. The Counseling Psychologist, 45(6), 873–901. 10.1177/0011000017733048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott DE, Bjelajac P, Fallot RD, Markoff LS, & Reed BG (2005). Trauma-informed or trauma-denied: Principles and implementation of trauma-informed services for women. Journal of Community Psychology, 33(4), 461–477. 10.1002/jcop.20063 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Engelbrecht A, & Jobson L (2014). An investigation of trauma-associated appraisals and posttraumatic stress disorder in British and Asian trauma survivors: The development of the Public and Communal Self Appraisals Measure (PCSAM). SpringerPlus, 3(1), 44 10.1186/2193-1801-3-44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freed P, & SmithBattle L (2016). Promoting teen mothers’ mental health. American Journal of Maternal/Child Nursing, 41(2), 84–89. 10.1097/NMC.0000000000000216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garg S, Kim L, Whitaker M, O’Halloran A, Cummings C, Holstein R, Prill M, Chai SJ, Kirley PD, Alden NB, Kawasaki B, Yousey-Hindes K, Niccolai L, Anderson EJ, Openo KP, Weigel A, Monroe ML, Ryan P, Henderson J, . . .Fry A (2020). Hospitalization rates and characteristics of patients hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed coronavirus disease 2019—COVID-NET, 14 States. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 69(15), 458–469. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6915e3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez de La Cuesta G, Schweizer S, Diehle J, Young J, & Meiser-Stedman R (2019). The relationship between maladaptive appraisals and posttraumatic stress disorder: A meta-analysis. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 10(1), 1620084 10.1080/20008198.2019.1620084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould E, & Wilson V (2020). Black workers face two of the most lethal preexisting conditions for coronavirus-racism and economic inequality. Economic Policy Institute. www.epi.org/publication/black-workers-covid/ [Google Scholar]

- Green DM, Strange D, Lindsay DS, & Takarangi MK (2016). Trauma-related versus positive involuntary thoughts with and without meta-awareness. Consciousness and Cognition, 46, 163–172. 10.1016/jxoncog.2016.09.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg N, Docherty M, Gnanapragasam S, & Wessely S (2020). Managing mental health challenges faced by healthcare workers during covid-19 pandemic. BMJ, 368, m1211 10.1136/bmj.m1211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grills-Taquechel AE, Littleton HL, & Axsom D (2011). Social support, world assumptions, and exposure as predictors of anxiety and quality of life following a mass trauma. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 25(4), 498–506. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.12.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper GW, Tyler D, Vance GJ, & DiNicola J (2015). A family reunification intervention for runaway youth and their parents/guardians: The home free program. Child & Youth Services, 36(2), 150–172. 10.1080/0145935X.2015.1009029 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harrell SR (2000). A multidimensional conceptualization of racism-related stress: Implications for the well-being of people of color. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 70(1), 42–57. 10.1037/h0087722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris ME, & Fallot RD (2001). Using trauma theory to design service systems. Jossey-Bass. 10.1002/yd.23320018903 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan I, Stolk Y, Valibhoy M, Tucker A, & Baker J (2016). Cognitive assessment of refugee children: Effects of trauma and new language acquisition. Transcultural Psychiatry, 53(1), 81–109. 10.1177/1363461515612933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kataoka SH, Vona P, Acuna A, Jaycox L, Escudero P, Rojas C, Ramirez E, Langley A, & Stein BD (2018). Applying a trauma informed school systems approach: Examples from school community-academic partnerships. Ethnicity & Disease, 28(Suppl. 2), 417–426. 10.18865/ed.28.S2.417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killgore W, Cloonan SA, Taylor EC, & Dailey NS (2020). Loneliness: A signature mental health concern in the era of COVID-19. Psychiatry Research, 290, 113117 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, Cai Z, Hu J, Wei N, Wu J, Du H, Chen T, Li R, Tan H, Kang L, Yao L, Huang M, Wang H, Wang G, Liu Z, & Hu S (2020). Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Network Open, 3(3), e203976–e203976. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaJoie AS, Sprang G, & McKinney WP (2010). Long-term effects of Hurricane Katrina on the psychological well-being of evacuees. Disasters, 34(4), 1031–1044. 10.1111/j.1467-7717.2010.01181.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, & Folkman S (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, & Folkman S (1987). Transactional theory and research on emotions and coping. European Journal of Personality, 1(3), 141–169. 10.1002/per.2410010304 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Levenson J (2017). Trauma-informed social work practice. Social Work, 62(2), 105–113. 10.1093/sw/swx001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancini AD, Prati G, & Black S (2011). Self-worth mediates the effects of violent loss on PTSD symptoms. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 24(1), 116–120. 10.1002/jts.20597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell R, Brennan K, Curran D, Hanna D, & Dyer KF (2017). A meta-analysis of the association between appraisals of trauma and posttraumatic stress in children and adolescents. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 30(1), 88–93. 10.1002/jts.22157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muskett C (2014). Trauma-informed care in inpatient mental health settings: A review of the literature. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 23(1), 51–59. 10.1111/inm.12012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neubauer LC (2013). I’m culturally competent, now what? The use of inquiry methodology to explore cultural humility, cultural responsiveness and critical self-reflection in community-based participatory research and practice. Hawaii Journal of Medicine & Public Health, 72(8 Suppl. 3), 26..23901378 [Google Scholar]

- Nyongesa MK, Ssewanyana D, Mutindi A, Chongwo E, Scerif G, Newton C, & Abubakar A (2019). Assessing executive function in adolescence: A scoping review of existing measures and their psychometric robustness. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 311 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oehlberg B (2008). Why schools need to be trauma informed. Trauma and Loss, 8(2), 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Paz García-Vera M, Sanz J, & Gutiérrez S (2016). A systematic review of the literature on posttraumatic stress disorder in victims of terrorist attacks. Psychological Reports, 119(1), 328–359. 10.1177/0033294116658243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pozza A, Bossini L, Ferretti F, Olivola M, Del Matto L, Desantis S, Fagiolini A, & Coluccia A (2019). The effects of terrorist attacks on symptom clusters of PTSD: A comparison with victims of other traumatic events. Psychiatric Quarterly, 90(3), 587–599. 10.1007/s11126-019-09650-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ran L, Wang W, Ai M, Kong Y, Chen J, & Kuang L (2020). Psychological resilience, depression, anxiety, and somatization symptoms in response to COVID-19: A study of the general population in China at the peak of its epidemic. Social Science & Medicine, 262, 113261 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves E (2015). A synthesis of the literature on trauma-informed care. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 36(9), 698–709. 10.3109/01612840.2015.1025319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz MA, & Gibson CAM (2020). Emotional impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on US health care workers: A gathering storm. Psychological Trauma, 12(Suppl. 1), S153–S155. 10.1037/tra0000851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamai M (2015). Systemic interventions for collective and national trauma: Theory, practice, and evaluation. Routledge; 10.4324/9781315709154 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd L, & Wild J (2014). Emotion regulation, physiological arousal and PTSD symptoms in trauma-exposed individuals. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 45(3), 360–367. 10.1016/j.jbtep.2014.03.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2014a). SAMHSA’s concept of trauma and guidance for a trauma-informed approach (HHS Publication No. 14–4884). [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2014b). Trauma-informed care in behavioral health services: Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series 57 (HHS Publication No. 13–4801). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takarangi MK, Strange D, & Lindsay DS (2014). Selfreport may underestimate trauma intrusions. Consciousness and Cognition, 27, 297–305. 10.1016/j.concog.2014.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanne JH (2020). Covid-19: Mental health and economic problems are worse in US than in other rich nations. BMJ, 370, m3110 10.1136/bmj.m3110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas MS, Crosby S, & Vanderhaar J (2019). Trauma-informed practices in schools across two decades: An interdisciplinary review of research. Review of Research in Education, 43(1), 422–452. 10.3102/0091732X18821123 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Torales J, O’Higgins M, Castaldelli-Maia JM, & Ventriglio A (2020). The outbreak of COVID-19 coronavirus and its impact on global mental health. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 66(4), 317–320. 10.1177/0020764020915212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams RD II, Shah A, Tikkanen R, Schneider EC, & Doty MM (2020). Do Americans face greater mental health and economic consequences from COVID-19? Comparing the U.S. with other high-income countries. www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2020/aug/americans-mental-health-and-economic-consequences-COVID19 [Google Scholar]