Abstract

Objectives:

The objective of this study was to compare survival outcomes and intra-arrest arterial blood pressures between children receiving cardiopulmonary resuscitation for bradycardia and poor perfusion and those with pulseless cardiac arrests.

Design:

Prospective, multicenter observational study.

Setting:

PICUs and cardiac ICUs of the Collaborative Pediatric Critical Care Research Network.

Patients:

Children (< 19 yr old) who received greater than or equal to 1 minute of cardiopulmonary resuscitation with invasive arterial blood pressure monitoring in place.

Interventions:

None.

Measurements and Main Results:

Of 164 patients, 96 (59%) had bradycardia and poor perfusion as the initial cardiopulmonary resuscitation rhythm. Compared to those with initial pulseless rhythms, these children were younger (0.4 vs 1.4 yr; p = 0.005) and more likely to have a respiratory etiology of arrest (p < 0.001). Children with bradycardia and poor perfusion were more likely to survive to hospital discharge (adjusted odds ratio, 2.31; 95% CI, 1.10–4.83; p = 0.025) and survive with favorable neurologic outcome (adjusted odds ratio, 2.21; 95% CI, 1.04–4.67; p = 0.036). There were no differences in diastolic or systolic blood pressures or event survival (return of spontaneous circulation or return of circulation via extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation). Among patients with bradycardia and poor perfusion, 49 of 96 (51%) had subsequent pulselessness during the cardiopulmonary resuscitation event. During cardiopulmonary resuscitation, these patients had lower diastolic blood pressure (point estimate, −6.68 mm Hg [−10.92 to −2.44 mm Hg]; p = 0.003) and systolic blood pressure (point estimate, −12.36 mm Hg [−23.52 to −1.21 mm Hg]; p = 0.032) and lower rates of return of spontaneous circulation (26/49 vs 42/47; p < 0.001) than those who were never pulseless.

Conclusions:

Most children receiving cardiopulmonary resuscitation in ICUs had an initial rhythm of bradycardia and poor perfusion. They were more likely to survive to hospital discharge and survive with favorable neurologic outcomes than patients with pulseless arrests, although there were no differences in immediate event outcomes or intra-arrest hemodynamics. Patients who progressed to pulselessness after cardiopulmonary resuscitation initiation had lower intra-arrest hemodynamics and worse event outcomes than those who were never pulseless.

Keywords: bradycardia, cardiac arrest, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, hemodynamics, pediatrics

More than 15,000 children receive cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) while hospitalized in the United States annually (1). As opposed to adult in-hospital cardiac arrests (IHCAs), the majority of pediatric IHCAs occur in the ICU and greater than 85% have a nonshockable initial rhythm (2–4). As with adult IHCAs, most are the result of progressive shock or respiratory failure (5–7).

In children, bradycardia and poor perfusion is a life-threatening response to hypoxemia and/or profound circulatory shock that often progresses to pulseless cardiac arrest within minutes (8–10). As such, Pediatric Advanced Life Support guidelines recommend the provision of CPR for children with bradycardia and poor perfusion (11). In several contemporary studies, bradycardia and poor perfusion is the initial cardiac arrest rhythm in the majority of events (2, 4, 7, 12). These children have higher rates of survival to hospital discharge compared with children with pulseless nonshockable rhythms (8). Additionally, a recent registry study found that 31% of children with bradycardia and poor perfusion subsequently became pulseless during CPR. These patients had lower rates of survival to hospital discharge than either those with initial pulselessness or those with bradycardia that never became pulseless (4). The precise mechanisms driving these survival differences are not entirely known, but superior hemodynamics during CPR has been speculated perhaps because CPR is initiated at an earlier stage in the process of cardiorespiratory collapse.

The Pediatric Intensive Care Quality of CPR (PICqCPR) study was a multicenter, prospective cohort study that established that mean diastolic blood pressure (DBP) values greater than or equal to 25 mm Hg during CPR for infants and greater than or equal to 30 mm Hg for older children were associated with higher rates of survival to hospital discharge and survival with favorable neurologic outcome (2). We aimed to perform a secondary study of PICqCPR patients to compare rates of survival and intra-arrest hemodynamics between children with CPR initiated for bradycardia and poor perfusion versus those with pulseless IHCA. Our primary hypotheses were that children with bradycardia and poor perfusion would have both higher rates of survival and higher intra-arrest blood pressures (BPs), thus providing a potential physiologic mechanism for these superior outcomes. Additionally, among patients with bradycardia and poor perfusion, we aimed to compare patients with and without subsequent pulselessness during CPR.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Setting and Design

The PICqCPR study was a prospective, multicenter, observational cohort study of CPR events occurring in the ICUs of 11 institutions between July 1, 2013, and June 30, 2016. The study was conducted by the Collaborative Pediatric Critical Care Research Network (CPCCRN), a Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development funded research collaborative. The main PICqCPR study evaluated the association of invasively measured BPs during CPR with survival outcomes (2). This study was a secondary analysis of data from the PICqCPR study. The institutional review boards of each clinical site and of the CPCCRN Data Coordinating Center (DCC) at the University of Utah approved the PICqCPR study protocol with waiver of informed consent.

Patient Population

All children less than 19 years old and greater than or equal to 37 weeks’ corrected gestational age who received greater than or equal to 1 minute of CPR for an index IHCA event in the ICU of a participating center and who had invasive arterial BP monitoring at the time of CPR were eligible for inclusion. Events were required to have the beginning of CPR captured in arterial BP waveform data; greater than or equal to 1 minute of continuous arterial BP waveform available; and central venous pressure, respiratory plethysmography, or electrocardiographic waveform data sufficient to determine stops and starts in CPR.

Measurements and Waveform Analyses

Trained research coordinators at each site collected standardized Utstein-style data elements (2, 13–17). Waveforms were printed from central monitoring stations, deidentified, and transmitted to the DCC. Only index IHCA event data were collected. Investigators at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, who were blinded to patient characteristics and outcomes, then digitized, manually reviewed, and analyzed the waveforms. The central venous pressure, respiratory plethysmography, and electrocardiographic waveforms were used to determine starts, stops, and interruptions in CPR. For each individual compression, systolic BP (SBP) was sampled at the peak of the arterial pressure waveform and DBP at the mid-point of the relaxation phase. Values of SBP and DBP for each minute of CPR and for the entire event, up to 10 minutes, were calculated by averaging each individual compression value, excluding periods of interruptions in chest compressions. Patients were categorized according to the rhythm at the time CPR commenced as follows: 1) bradycardia and poor perfusion or 2) pulseless cardiac arrest (asystole, pulseless electrical activity [PEA], ventricular fibrillation [VF], or pulseless ventricular tachycardia). For the secondary analysis, based on review of the entire waveform for identification of subsequent pulselessness, patients with bradycardia and poor perfusion were classified as follows: 1) subsequently pulseless or 2) never pulseless. Pulselessness was defined by pulse pressure less than 10 mm Hg and SBP less than 50 mm Hg (≥ 1 yr) or less than 40 mm Hg (< 1 yr) (18, 19).

Outcomes and Statistical Analysis

The primary survival outcome was survival to hospital discharge with favorable neurologic outcome, defined by a Pediatric Cerebral Performance Category (PCPC) score of less than or equal to 3 or no worse than baseline (20, 21). Secondary survival outcomes were event outcome (return of spontaneous circulation [ROSC] ≥ 20 min [13], return of circulation via extracorporeal CPR [ECPR], or death); survival to hospital discharge; and new morbidity among survivors, defined as an increase in Functional Status Scale (FSS) score by greater than or equal to 3 (22). The primary hemodynamic outcome was mean event DBP. Secondary hemodynamic outcomes were mean event SBP and whether or not mean event DBP met threshold targets (≥ 25 mm Hg for infants and ≥ 30 mm Hg for older children) (2).

Patient and cardiac arrest characteristics and outcomes were compared between the primary groups with the Fisher exact test for categorical variables, Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables, and Cochran-Armitage test for trend for baseline PCPC and duration of CPR. Logistic and linear regression models adjusting a priori for age category (< 1 yr, ≥ 1 yr), location of CPR (PICU, cardiac ICU), and study site were used to compare hemodynamic outcomes, survival to hospital discharge, and survival to discharge with favorable neurologic outcome (6, 23, 24). Among patients with bradycardia and poor perfusion, the same analyses above were used to compare those with subsequent pulselessness and those who were never pulseless. All analyses were performed with SAS Version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Over the 3-year study period, 164 patients met all criteria and were included in the final cohort. The majority of patients (96/164; 59%) had bradycardia and poor perfusion as the initial CPR rhythm. Patient characteristics and CPR event characteristics, including their univariable associations with bradycardia versus pulseless rhythms are detailed in Tables 1 and 2, respectively.

TABLE 1.

Patient Characteristics by Initial Rhythm

| Patient Characteristic | Overall (n = 164) | Bradycardia and Poor Perfusion (n = 96) | Pulseless (n = 68) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr, median (IQR) | 0.7 (0.1–3.1) | 0.4 (0.1–1.5) | 1.4 (0.3–7.4) | 0.005a |

| Age, yr, n (%) | < 0.001b | |||

| < 1 | 98 (60) | 68 (71) | 30 (44) | |

| ≥ 1 | 66 (40) | 28 (29) | 38 (60) | |

| Male, n (%) | 90 (55) | 55 (57) | 35 (51) | 0.525b |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | 0.702b | |||

| Hispanic or Latino | 28 (17) | 16 (17) | 12 (18) | |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 120 (73) | 69 (72) | 51 (75) | |

| Unknown or not reported | 16 (10) | 11 (11) | 5 (7) | |

| Race, n (%) | 0.487b | |||

| White | 82 (50) | 47 (49) | 35 (51) | |

| Black or African American | 37 (23) | 19 (20) | 18 (26) | |

| Other | 8 (5) | 6 (6) | 2 (3) | |

| Unknown or not reported | 37 (23) | 24 (25) | 13 (19) | |

| Preexisting conditions, n (%) | ||||

| Respiratory insufficiency | 132 (80) | 79 (82) | 53 (78) | 0.551b |

| Hypotension | 128 (78) | 72 (75) | 56 (82) | 0.339b |

| Congestive heart failure | 19 (12) | 7 (7) | 12 (18) | 0.050b |

| Pneumonia | 13 (8) | 8 (8) | 5 (7) | 1.000b |

| Sepsis | 44 (27) | 24 (25) | 20 (29) | 0.593b |

| Trauma | 8 (5) | 4 (4) | 4 (6) | 0.719b |

| Renal insufficiency | 24 (15) | 10 (10) | 14 (21) | 0.077b |

| Malignancy | 5 (3) | 1 (1) | 4 (6) | 0.161b |

| Congenital heart disease | 99 (60) | 64 (67) | 35 (51) | 0.054b |

| Illness category, n (%) | 0.186b | |||

| Surgical cardiac | 88 (54) | 58 (60) | 30 (44) | |

| Medical cardiac | 25 (15) | 12 (13) | 13 (19) | |

| Surgical noncardiac | 13 (8) | 7 (7) | 6 (9) | |

| Medical noncardiac | 37 (23) | 18 (19) | 19 (28) | |

| Unknown | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | |

| Baseline Pediatric Cerebral Performance Category score, n (%) | 0.589c | |||

| Normal (1) | 77 (47) | 47 (49) | 30 (44) | |

| Mild disability (2) | 47 (29) | 27 (28) | 20 (29) | |

| Moderate disability (3) | 23 (14) | 12 (13) | 11 (16) | |

| Severe disability (4) | 13 (8) | 8 (8) | 5 (7) | |

| Coma/vegetative state (5) | 4 (2) | 2 (2) | 2 (3) | |

| Baseline Functional Status Scale score, median (IQR) | 8.0 (6.0–11.0) | 8.0 (6.0–10.5) | 8.0 (6.0–11.5) | 0.933a |

IQR = interquartile range.

Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

Fisher exact test.

Cochran-Armitage trend test.

TABLE 2.

Event Characteristics by Initial Rhythm

| Event Characteristic | Overall (n = 164) | Bradycardia and Poor Perfusion (n = 96) | Pulseless (n = 68) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prearrest hemodynamics, median (IQR) | ||||

| Mean DBP (6–10 min prearrest) | 41.5 (34.0–50.2) | 42.1 (33.2–52.0) | 40.8 (35.2–49.6) | 0.686a |

| Mean SBP (6–10 min prearrest) | 75.0 (59.2–92.0) | 75.5 (60.8–94.0) | 67.6 (55.6–89.6) | 0.357a |

| Mean DBP (1–5 min prearrest) | 39.8 (31.0–48.8) | 38.1 (30.1–49.2) | 40.8 (32.4–45.3) | 0.322a |

| Mean SBP (1–5 min prearrest) | 66.0 (54.0–88.8) | 65.1 (53.9–92.1) | 68.0 (54.0–84.4) | 0.704a |

| Immediate cause, n (%) | ||||

| Hypotension | 110 (67) | 66 (69) | 44 (65) | 0.616b |

| Respiratory decompensation | 72 (44) | 53 (55) | 19 (28) | < 0.001b |

| Location of CPR event, n (%) | 0.516b | |||

| PICU | 64 (39) | 35 (36) | 29 (43) | |

| Cardiac ICU | 100 (61) | 61 (64) | 39 (57) | |

| Initial pulseless rhythm, n (%) | ||||

| Asystole/pulseless electrical activity | 49 (72) | |||

| Ventricular fibrillation/pulseless ventricular tachycardia | 19 (28) | |||

| Duration or CPR, min, median (IQR) | 8.0 (3.0–27.0) | 7.0 (3.0–23.0) | 12.0 (4.0–36.5) | 0.092a |

| Duration of CPR, min, n (%) | 0.105c | |||

| 1–5 | 69 (42) | 43 (45) | 26 (38) | |

| 6–15 | 34 (21) | 21 (22) | 13 (19) | |

| 16–35 | 29 (18) | 18 (19) | 11 (16) | |

| > 35 | 31 (19) | 13 (14) | 18 (26) | |

| Unknown | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | |

| Timed, n (%) | 0.948b | |||

| Weekday | 102 (62) | 60 (63) | 42 (62) | |

| Weeknight | 34 (21) | 19 (20) | 15 (22) | |

| Weekend | 28 (17) | 17 (18) | 11 (16) | |

| Interventions in place, n (%) | ||||

| Central venous catheter | 142 (87) | 84 (88) | 58 (85) | 0.817b |

| Vasoactive infusion | 128 (78) | 73 (76) | 55 (81) | 0.566b |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation | 134 (82) | 77 (80) | 57 (84) | 0.683b |

| Noninvasive ventilation | 19 (12) | 12 (13) | 7 (10) | 0.806b |

| Pharmacologic interventions | ||||

| Epinephrine, n (%) | 143 (87) | 86 (90) | 57 (84) | 0.344b |

| Number of doses (when used), median (IQR) | 3 (1–5) | 2 (1–4) | 3 (2–6) | 0.061b,e |

| Calcium, n (%) | 78 (48) | 41 (43) | 37 (54) | 0.155a |

| Sodium bicarbonate, n (%) | 93 (57) | 54 (56) | 39 (57) | 1.000a |

CPR = cardiopulmonary resuscitation, DBP = diastolic blood pressure, IQR = interquartile range, SBP = systolic blood pressure.

Fisher exact test is used for categorical variables.

The Wilcoxon rank-sum test is used for continuous variables.

The Cochran-Armitage test for trend is used for duration of CPR category variables.

Weekdays: Monday to Friday, 07:00 to 22:59; weeknights: Monday to Friday, 23:00 to 06:59; and weekends: Saturday to Sunday.

The comparison of the number of epinephrine doses is based only on index events for which epinephrine was used.

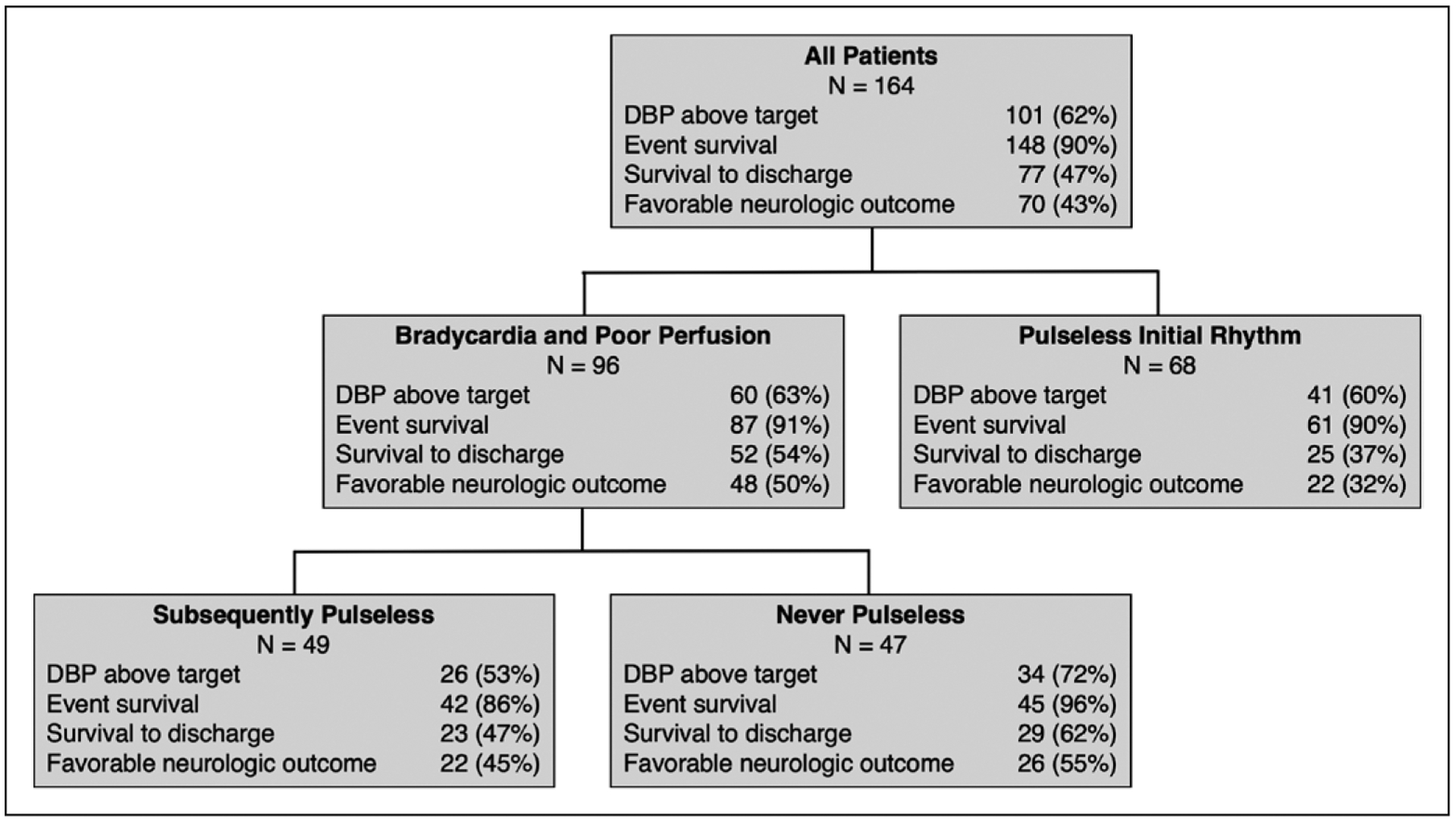

Event hemodynamics and survival outcomes and their univariable association with initial rhythm are contained in Table 3 and Figure 1. The median intra-arrest DBP was 29.3 mm Hg (22.8–37.9 mm Hg); 101 of 164 patients (62%) met mean DBP goals. The median intra-arrest SBP was 74.4 mm Hg (54.9–98.2 mm Hg). Event survival occurred in 148 of 164 (90%), 112 (68%) via sustained ROSC and 36 (22%) via ECPR. Seventy-seven of 164 (47%) survived to hospital discharge and 70 of 164 (43%) survived with favorable neurologic outcome. There were no differences in hemodynamics between children with bradycardia and poor perfusion versus those with pulseless rhythms on univariable (Table 3) or multivariable analyses (Table 4). Event outcomes did not differ between groups, but patients with bradycardia and poor perfusion were more likely to survive to hospital discharge (52/96 [54%] vs 25/68 [37%]; p = 0.039) and to survive with favorable neurologic outcome (48/96 [50%] vs 22/68 [32%]; p = 0.026) (Table 3). On multivariable analysis, bradycardia with poor perfusion was associated with higher odds of survival to hospital discharge (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 2.31; 95% CI, 1.10–4.83; p = 0.025) and survival with favorable neurologic outcome (aOR, 2.21; 95% CI, 1.04–4.67; p = 0.036) (Table 4).

TABLE 3.

Associations Between Hemodynamic and Survival Outcomes by Initial Rhythm

| Outcome | Overall (n = 164) | Bradycardia and Poor Perfusion (n = 96) | Pulseless (n = 68) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Event hemodynamicsa | ||||

| Above DBP targetsb, n (%) | 101 (61.6) | 60 (63) | 41 (60) | 0.871c |

| DBP, mm Hg, median (IQR) | 29.3 (22.8–37.9) | 29.5 (22.0–36.4) | 29.0 (24.9–39.0) | 0.502d |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg, median (IQR) | 74.4 (54.9–98.2) | 72.8 (55.0–97.4) | 77.6 (54.0–99.1) | 0.716d |

| Outcome of cardiopulmonary resuscitation event, n (%) | 0.658c | |||

| Return of spontaneous circulation ≥ 20 min | 112 (68) | 68 (71) | 44 (65) | |

| Return of circulation via extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation | 36 (22) | 19 (20) | 17 (25) | |

| Died | 16 (10) | 9 (9) | 7 (10) | |

| Survival outcomes, n (%) | ||||

| 24-hr survival | 135 (82) | 80 (83) | 55 (81) | 0.684c |

| Survival to hospital discharge | 77 (47) | 52 (54) | 25 (37) | 0.039c |

| Survival with favorable neurologic outcomee | 70 (43) | 48 (50) | 22 (32) | 0.026c |

| Outcomes among survivors, n (%) | ||||

| New morbidityf | 22/77 (29) | 16/52 (31) | 6/25 (24) | 0.600c |

| New domain morbidityg | 30/77 (39) | 21/52 (40) | 9/25 (36) | 0.805c |

DBP = diastolic blood pressure, IQR = interquartile range.

Average over (up to) the first 10 min of cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

Average DBP ≥ 25 mm Hg for infants or ≥ 30 mm Hg for children.

Fisher exact test.

Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

Discharge Pediatric Cerebral Performance Category ≤ 3 or no worse than baseline.

Increase in Functional Status Scale (FSS) ≥ 3 from baseline.

Increase in a single FSS domain ≥ 2 from baseline.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram depicting frequency of outcomes between groups. DBP = diastolic blood pressure.

TABLE 4.

Multivariable Models of Initial Rhythm With Hemodynamic and Survival Outcomes

| Outcome | Adjusted Estimatea (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|

| Event hemodynamicsb | ||

| Above DBP targetsc | 0.92 (0.44–1.92)d | 0.817 |

| DBP, mm Hg | −3.28 (−7.49 to 0.94)e | 0.129 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 3.33 (−6.36 to 13.02)e | 0.501 |

| Survival outcomes | ||

| Survival to hospital discharge | 2.31 (1.10–4.83)d | 0.025 |

| Survival with favorable neurologic outcomef | 2.21 (1.04–4.67)d | 0.036 |

DBP = diastolic blood pressure.

Results are based on multiple logistic or linear regression models, adjusting for age category (< 1 yr, ≥ 1 yr), location of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), and study site. All estimates show bradycardia and poor perfusion vs asystole/pulseless electrical activity/ventricular fibrillation/ventricular tachycardia.

Average over (up to) the first 10 min of CPR.

Average DBP ≥ 25 mm Hg for infants or ≥ 30 mm Hg for children.

Odds ratio estimate.

Linear effect estimate.

Discharge Pediatric Cerebral Performance Category ≤ 3 or no worse than baseline.

Of the 96 patients with bradycardia and poor perfusion, 49 (51%) subsequently became pulseless and 47 (49%) were never pulseless. The patient and arrest characteristics of these groups are detailed in Supplemental Table 1 (Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/CCM/F410) and Supplemental Table 2 (Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/CCM/F411), respectively. Of the 49 patients with subsequent pulselessness, the initial pulseless rhythm was PEA in 44 (90%), asystole in four (8%), and VF in one (2%). The median time to subsequent pulselessness was 1.0 minutes (0.4–1.7 min).

Event hemodynamics and survival outcomes in patients with bradycardia and poor perfusion and their association with subsequent pulselessness are contained in Supplemental Table 3 (Supplemental Digital Content 3, http://links.lww.com/CCM/F412), Supplemental Table 4 (Supplemental Digital Content 4, http://links.lww.com/CCM/F413), and Figure 1. Those with subsequent pulselessness had lower DBP during CPR than those who were never pulseless (25.3 mm Hg [19.0–33.0 mm Hg] vs 33.0 mm Hg [25.0–41.5 mm Hg]; p = 0.009). On multivariable analysis, patients with subsequent pulselessness had lower DBP (point estimate, −6.68 mm Hg [−10.92 to −2.44 mm Hg]; p = 0.003) and lower SBP (point estimate −12.36 mm Hg [−23.52 to −1.21 mm Hg]; p = 0.032). Event outcomes varied between groups, as those with subsequent pulselessness had lower rates of ROSC and higher rates of ECPR or death (p < 0.001). There were no differences in survival to hospital discharge or survival with favorable neurologic outcome in univariable or multivariable analyses.

DISCUSSION

In this multicenter study of pediatric IHCA, the majority of children (59%) had bradycardia and poor perfusion as their initial CPR rhythm. Consistent with previous studies (4, 8), these children were more likely to survive to hospital discharge and to survive with favorable neurologic outcomes compared with children with pulselessness at the time of CPR. Contrary to our hypothesis, intra-arrest hemodynamics were not different between these groups. However, within the group with bradycardia and poor perfusion, half of patients subsequently became pulseless during CPR, and those patients had lower BPs and lower rates of ROSC than those who were never pulseless.

This high proportion of bradycardia and poor perfusion is consistent with a recent registry study in which 50% of index CPR events were in children with bradycardia and poor perfusion (4). In contrast to this registry data in which rhythm determination is based on clinical impressions and retrospective medical record abstraction, all children in our study had arterial catheters in place and continuous monitoring in an ICU setting. Therefore, bedside clinicians had more objective data regarding pulselessness at the time of CPR onset, although the manner in which it influenced their decision making regarding the provision of CPR cannot be ascertained. Furthermore, we were able to determine whether or not patients subsequently became pulseless rather than relying entirely on clinician observation and report.

Most IHCA deaths occur after initially successful resuscitation (7, 25). Indeed, in this study, 90% of children survived the CPR event—the survival differences between groups were observed at the time of hospital discharge. By promptly supporting myocardial and cerebral perfusion rather than awaiting “no flow” from a pulseless cardiac arrest, aggressive CPR for children with bradycardia and poor perfusion presumably lessened hypoxic-ischemic injury and optimized the chances for meaningful recovery and survival. It is also possible that children with this initial rhythm may represent a less critically ill cohort with less severe IHCA mechanisms. However, while children with bradycardia and poor perfusion were more likely to have a respiratory etiology of their cardiac arrest, they did not have substantial pre- or intra-arrest clinical differences or BP differences during the 10 minutes preceding CPR. Although it could be argued that CPR was provided unnecessarily or when other interventions would have sufficed, all of these critically ill children decompensated despite ICU care. Furthermore, half of these events progressed to pulseless IHCA. Cumulatively, these findings stand in support of current guidelines that recommend the provision of CPR for bradycardia and poor perfusion (26).

Coronary perfusion pressure is the principal determinant of myocardial blood flow, the generation of which is imperative for successful resuscitation from cardiac arrest (27–30). Previous investigations, including the parent study from this same cohort of patients, have found that DBP, the upstream pressure of coronary perfusion pressure, is correlated with survival (2, 29). Therefore, we expected that patients with more favorable initial CPR rhythms would have higher BPs, providing a physiologic mechanism for superior outcomes. BPs during CPR were similar between patients with and without pulses at the onset of CPR. However, in children with bradycardia with poor perfusion, BPs were significantly higher in those without subsequent pulselessness. This may suggest that achieving adequate hemodynamics early in CPR can prevent the development of pulselessness and improve outcomes.

In addition to their lower BPs during CPR, patients with bradycardia and subsequent pulselessness had longer CPR duration (14 vs 3 min), lower rates of ROSC, higher rates of ECPR, and equivalent rates of survival to discharge compared with those who were never pulseless. These data indicate that those patients in whom CPR efforts were effective responded early while those in whom they were insufficient deteriorated early—the median onset of pulselessness in this group was 1 minute after CPR commencement. Among this group with bradycardia that progressed to pulselessness, the clinical team deemed ECPR to be necessary in a high proportion. Overall, these findings demonstrate that while children receiving CPR for bradycardia with poor perfusion are more likely to have favorable outcomes than those with pulseless arrests, this group’s characteristics and event outcomes are dichotomized by whether or not subsequent pulselessness develops. The specific association between timing of pulselessness and outcome should be a focus of future studies.

This study had limitations. First, its observational nature allowed us to measure associations yet precluded ascertainment of causality. Second, the relatively small sample size limited statistical power. It is possible that event survival, intra-arrest hemodynamics, or other characteristics would have differed in a larger study. Determining the association between hemodynamics and survival within individual patient groups (e.g., specific rhythms or arrest etiologies) would also be of value. Third, we only collected waveform data for the first 10 minutes of CPR. Therefore, in the group with bradycardia and poor perfusion, we were unable to identify subsequent pulselessness during CPR if it first occurred more than 10 minutes after the initiation of CPR. Given the median CPR duration of 3 minutes in the group that never had pulselessness identified, we anticipate that there were few cases of unidentified subsequent pulselessness. Fourth, although we reported SBP, its physiologic significance as an indirect measure of blood flow is likely modest relative to DBP. Furthermore, the accuracy of measuring the narrow systolic peak generated by chest compressions is unknown. Finally, PCPC is a gross measure of neurologic status and likely underestimated functional morbidity among survivors—importantly, there were no differences in the incidence of new morbidity between patients with bradycardia and poor perfusion and those with pulseless IHCA using FSS, a more granular outcome scale.

CONCLUSIONS

In this multicenter observational study of pediatric IHCA, bradycardia and poor perfusion was the initial CPR rhythm in 59% of arrests. Compared to pulseless rhythms, children with bradycardia and poor perfusion were more likely to survive to hospital discharge and survive with favorable neurologic outcomes, although there were no differences in immediate event outcomes or intra-arrest hemodynamics. Patients who progressed to pulselessness after CPR initiation had lower intra-arrest hemodynamics and lower rates of ROSC than those who were never pulseless during CPR.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Robert Tamburro and Tammara Jenkins of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development/Collaborative Pediatric Critical Care Research Network.

Supported, in part, by the following cooperative agreements from the National Institute of Health’s Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development: UG1HD050096, UG1HD049981, UG1HD049983, UG1HD063108, UG1HD083171, UG1HD083166, UG1HD083170, U10HD050012, U10HD063106, U10HD063114, and U01HD049934.

APPENDIX

Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development/Collaborative Pediatric Critical Care Research Network (CPCCRN) Pediatric Intensive Care Quality of Cardio-Pulmonary Resuscitation (PICqCPR) Investigators: Athena F. Zuppa, MD, MSCE (Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Care Medicine, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia & University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA); Carolann Twelves, RN (Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Care Medicine, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia & University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA); Mary Ann Diliberto, RN (Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Care Medicine, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia & University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA); Elyse Tomanio, RN (Department of Pediatrics, Children’s National Medical Center, Washington, DC); Jeni Kwok, JD (Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Care Medicine, Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles, University of Southern California Keck College of Medicine, Los Angeles, CA); Michael J. Bell, MD (Department of Pediatrics, Children’s National Medical Center, Washington, DC and Department of Critical Care Medicine, Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA); Alan Abraham, MBA (Department of Critical Care Medicine, Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA); Anil Sapru, MD (Department of Pediatrics, Benioff Children’s Hospital, University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, CA and Department of Pediatrics, Mattel Children’s Hospital, University of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA); Mustafa F. Alkhouli, BA (Department of Pediatrics, Benioff Children’s Hospital, University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, CA); Sabrina Heidemann, MD (Department of Pediatrics, Children’s Hospital of Michigan, Wayne State University, Detroit, MI); Ann Pawluszka, RN (Department of Pediatrics, Children’s Hospital of Michigan, Wayne State University, Detroit, MI); Mark W. Hall, MD (Department of Pediatrics, Nationwide Children’s Hospital, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH); Lisa Steele, RN (Department of Pediatrics, Nationwide Children’s Hospital, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH); Thomas P. Shanley, MD (Department of Pediatrics, C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI and Department of Pediatrics, Lurie Children’s Hospital, Northwestern University, Chicago, IL); Monica Weber, RN (Department of Pediatrics, C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI); Heidi J. Dalton, MD (Department of Pediatrics, Phoenix Children’s Hospital, Phoenix, AZ); Aimee La Bell, RN (Department of Pediatrics, Phoenix Children’s Hospital, Phoenix, AZ); Peter M. Mourani, MD (Department of Pediatrics, Children’s Hospital of Colorado, University of Colorado, Denver, CO); Kathryn Malone, RN (Department of Pediatrics, Children’s Hospital of Colorado, University of Colorado, Denver, CO); Christopher Locandro, MSPH (Department of Pediatrics, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT); R. Whitney Coleman (Department of Pediatrics, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT); Alecia Peterson, MS (Department of Pediatrics, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT); Julie Thelen (Department of Pediatrics, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT); and Allan Doctor, MD (Department of Pediatrics, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO).

Footnotes

Dr. Morgan, Dr. Reeder, Dr. Meert, Dr. Telford, Dr. Yates, Dr. Berger, Ms. Graham, Mr. Landis, Dr. Kilbaugh, Dr. Newth, Dr. Carcillo, Dr. McQuillen, Dr. Harrison, Dr. Moler, Dr. Pollack, Dr. Notterman, Dr. Holubkov, Dr. Dean, Dr. Nadkarni, Dr. Berg, and Dr. Sutton received funding from the National Institutes of Health’s Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institutes of Child Health and Human Development. Dr. Berger’s institution received funding from Actelion and the Association for Pediatric Pulmonary Hypertension. Dr. Kilbaugh received funding from the Department of Defense, Neurovive Pharmaceuticals, Ischmemix, Astrocyte Pharmaceuticals, and Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Newth received funding from Philips Research North America and he reports consulting services for both Philips Research of North America and Medtronics; also received funding from Hamilton Medical AG. Dr. Pollack reports grant funding from the Department of Defense, collaborative projects with Cerner, and philanthropy from Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Notterman received funding from the University of Utah and Princeton University. Dr. Holubkov received funding from Pfizer (Data and Safety Monitoring Board [DSMB]) Medimmune (DSMB), Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine (biostatistical consultant), Revance (DSMB), American Burn Association (DSMB), Armaron Bio (DSMB), DURECT (biostatistical consulting), and St. Jude Medical (biostatistical consulting). Dr. Sutton’s institution received funding from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, and disclosed he is the Vice-Chair of the Pediatric Research Task Force of the American Heart Association Get With the Guidelines Resuscitation Registry. The remaining authors have disclosed that they do not have any potential conflicts of interest.

The Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development/Collaborative Pediatric Critical Care Research Network (CPCCRN) Pediatric Intensive Care Quality of Cardio-Pulmonary Resuscitation (PICqCPR) Investigators are listed in the Appendix.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s website (http://journals.lww.com/ccmjournal).

REFERENCES

- 1.Holmberg MJ, Ross CE, Fitzmaurice GM, et al. ; American Heart Association’s Get With The Guidelines-Resuscitation Investigators: Annual incidence of adult and pediatric in-hospital cardiac arrest in the United States. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2019; 12:e005580. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berg RA, Sutton RM, Reeder RW, et al. ; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Collaborative Pediatric Critical Care Research Network (CPCCRN) PICqCPR (Pediatric Intensive Care Quality of Cardio-Pulmonary Resuscitation) Investigators: Association between diastolic blood pressure during pediatric in-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation and survival. Circulation 2018; 137:1784–1795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holmberg MJ, Moskowitz A, Raymond TT, et al. ; American Heart Association’s Get With The Guidelines-Resuscitation Investigators: Derivation and internal validation of a mortality prediction tool for initial survivors of pediatric in-hospital cardiac arrest. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2018; 19:186–195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khera R, Tang Y, Girotra S, et al. ; American Heart Association’s Get With the Guidelines-Resuscitation Investigators: Pulselessness after initiation of cardiopulmonary resuscitation for bradycardia in hospitalized children. Circulation 2019; 140:370–378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berg RA, Sutton RM, Holubkov R, et al. ; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Collaborative Pediatric Critical Care Research Network and for the American Heart Association’s Get With the Guidelines-Resuscitation (formerly the National Registry of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation) Investigators: Ratio of PICU versus ward cardiopulmonary resuscitation events is increasing. Crit Care Med 2013; 41:2292–2297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matos MR, Watson RS, Nadkarni VM, et al. : Response to letters regarding article, “Duration of cardiopulmonary resuscitation and illness category impact survival and neurologic outcomes for in-hospital pediatric cardiac arrests.” Circulation 2013; 128:e102–e103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berg RA, Nadkarni VM, Clark AE, et al. ; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Collaborative Pediatric Critical Care Research Network: Incidence and outcomes of cardiopulmonary resuscitation in PICUs. Crit Care Med 2016; 44:798–808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donoghue A, Berg RA, Hazinski MF, et al. ; American Heart Association National Registry of CPR Investigators: Cardiopulmonary resuscitation for bradycardia with poor perfusion versus pulseless cardiac arrest. Pediatrics 2009; 124:1541–1548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walsh CK, Krongrad E: Terminal cardiac electrical activity in pediatric patients. Am J Cardiol 1983; 51:557–561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeBehnke DJ, Hilander SJ, Dobler DW, et al. : The hemodynamic and arterial blood gas response to asphyxiation: A canine model of pulseless electrical activity. Resuscitation 1995; 30:169–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Caen AR, Berg MD, Chameides L, et al. : Part 12: Pediatric Advanced Life Support: 2015 American Heart Association guidelines update for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation 2015; 132:S526–S542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meert KL, Donaldson A, Nadkarni V, et al. ; Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network: Multicenter cohort study of in-hospital pediatric cardiac arrest. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2009; 10:544–553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jacobs I, Nadkarni V, Bahr J, et al. ; International Liason Committee on Resusitation: Cardiac arrest and cardiopulmonary resuscitation outcome reports: Update and simplification of the Utstein templates for resuscitation registries. A statement for healthcare professionals from a task force of the international liaison committee on resuscitation (American Heart Association, European Resuscitation Council, Australian Resuscitation Council, New Zealand Resuscitation Council, Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, InterAmerican Heart Foundation, Resuscitation Council of Southern Africa). Resuscitation 2004; 63:233–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berg RA, Reeder RW, Meert KL, et al. ; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Collaborative Pediatric Critical Care Research Network (CPCCRN) Pediatric Intensive Care Quality of Cardio-Pulmonary Resuscitation (PICqCPR) investigators: End-tidal carbon dioxide during pediatric in-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Resuscitation 2018; 133:173–179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sutton RM, Reeder RW, Landis W, et al. ; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Collaborative Pediatric Critical Care Research Network (CPCCRN) Investigators: Chest compression rates and pediatric in-hospital cardiac arrest survival outcomes. Resuscitation 2018; 130:159–166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Topjian AA, Sutton RM, Reeder RW, et al. ; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Collaborative Pediatric Critical Care Research Network (CPCCRN) Investigators: The association of immediate post cardiac arrest diastolic hypertension and survival following pediatric cardiac arrest. Resuscitation 2019; 141:88–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sutton RM, Reeder RW, Landis WP, et al. ; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Collaborative Pediatric Critical Care Research Network (CPCCRN): Ventilation rates and pediatric in-hospital cardiac arrest survival outcomes. Crit Care Med 2019; 47:1627–1636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tibballs J, Russell P: Reliability of pulse palpation by healthcare personnel to diagnose paediatric cardiac arrest. Resuscitation 2009; 80:61–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morgan RW, Landis WP, Marquez A, et al. : Hemodynamic effects of chest compression interruptions during pediatric in-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Resuscitation 2019; 139:1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fiser DH: Assessing the outcome of pediatric intensive care. J Pediatr 1992; 121:68–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Becker LB, Aufderheide TP, Geocadin RG, et al. ; American Heart Association Emergency Cardiovascular Care Committee; Council on Cardiopulmonary, Critical Care, Perioperative and Resuscitation: Primary outcomes for resuscitation science studies: A consensus statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2011; 124:2158–2177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pollack MM, Holubkov R, Glass P, et al. ; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Collaborative Pediatric Critical Care Research Network: Functional Status Scale: New pediatric outcome measure. Pediatrics 2009; 124:e18–e28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meaney PA, Nadkarni VM, Cook EF, et al. ; American Heart Association National Registry of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Investigators: Higher survival rates among younger patients after pediatric intensive care unit cardiac arrests. Pediatrics 2006; 118:2424–2433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gupta P, Rettiganti M, Jeffries HE, et al. : Risk factors and outcomes of in-hospital cardiac arrest following pediatric heart operations of varying complexity. Resuscitation 2016; 105:1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Girotra S, Spertus JA, Li Y, et al. ; American Heart Association Get With the Guidelines–Resuscitation Investigators: Survival trends in pediatric in-hospital cardiac arrests: An analysis from Get With the Guidelines-Resuscitation. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2013; 6:42–49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Atkins DL, Berger S, Duff JP, et al. : Part 11: Pediatric Basic Life Support and Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Quality: 2015 American Heart Association guidelines update for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation 2015; 132:S519–S525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kern KB, Ewy GA, Voorhees WD, et al. : Myocardial perfusion pressure: A predictor of 24-hour survival during prolonged cardiac arrest in dogs. Resuscitation 1988; 16:241–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Raessler KL, Kern KB, Sanders AB, et al. : Aortic and right atrial systolic pressures during cardiopulmonary resuscitation: A potential indicator of the mechanism of blood flow. Am Heart J 1988; 115:1021–1029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sanders AB, Ewy GA, Taft TV: Prognostic and therapeutic importance of the aortic diastolic pressure in resuscitation from cardiac arrest. Crit Care Med 1984; 12:871–873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berkowitz ID, Chantarojanasiri T, Koehler RC, et al. : Blood flow during cardiopulmonary resuscitation with simultaneous compression and ventilation in infant pigs. Pediatr Res 1989; 26:558–564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.