Abstract

Background

Some patients with prostate cancer regret their treatment choice. Treatment regret is associated with lower physical and mental quality of life. We investigated whether, in men with prostate cancer, spirituality is associated with lower decisional regret 6 months after treatment and whether this is, in part, because men with stronger spiritual beliefs experience lower decisional conflict when they are deciding how to treat their cancer.

Methods

One thousand ninety three patients with prostate cancer (84% white, 10% black, and 6% Hispanic; mean age = 63.18; SD = 7.75) completed measures of spiritual beliefs and decisional conflict after diagnosis and decisional regret 6 months after treatment. We used multivariable linear regression to test whether there is an association between spirituality and decisional regret and structural equation modeling to test whether decisional conflict mediated this relationship.

Results

Stronger spiritual beliefs were associated with less decisional regret (b = −0.39, 95% CI = −0.53, −0.26, P < .001, partial η2 = 0.024, confidence interval = −0.55, 39%, P < .001, partial η2 = 0.03), after controlling for covariates. Decisional conflict partially (38%) mediated the effect of spirituality on regret (indirect effect: b = −0.16, 95% CI = −0.21, −0.12, P < .001).

Conclusions

Spirituality may help men feel less conflicted about their cancer treatment decisions and ultimately experience less decisional regret. Psychosocial support post-diagnosis could include clarification of spiritual values and opportunities to reappraise the treatment decision-making challenge in light of these beliefs.

Keywords: cancer, oncology, prostate cancer, spirituality, treatment decision making, treatment regret

1 |. BACKGROUND

Regret has been described as a comparison of reality versus what might have been. It is not uncommon for about a quarter of patients with prostate cancer to experience some regret about their treatment choice1,2; Estimates, however, have varied, ranging from 4 to 57%.3–5 Long-term treatment regret has been associated with lower psychosocial quality of life and well-being in patients with prostate cancer.2,6 Men with localized prostate cancer have multiple treatment options, including surgery and radiotherapy, with different side-effect profiles that include incontinence, erectile dysfunction, and bowel pain and dysfunction. Active surveillance, or periodic monitoring of the cancer, is also a viable option for men with low-risk disease.7,8 Given multiple treatment options and high risk for significant side effects from definitive therapies, it has been recommended that patients and providers collectively weigh clinical indicators with the benefits and risks of each intervention.9–11 Choice and uncertainty about what might have been may exacerbate the potential for regret, and the absence of treatment regret has become one measure of a “good” treatment decision.12

We hypothesize that personal beliefs and values such as spiritual beliefs may play a role in impacting the level of regret experienced by patients. The goal of the present study was to explore the relationship between spirituality and decisional regret and to test whether spirituality impacts regret though lower decisional conflict, shown to be lower in men with stronger spiritual beliefs.13 Results inform the development of strategies for mitigating regret and improving quality of life in patients with clinically localized prostate cancer.

Four classes of determinants of regret have emerged in the cancer literature. Decisional regret has been associated with patients with prostate cancer’s perceptions of treatment efficacy, the degree to which patients experience treatment side effects,2,4,14 and overall quality of life.3,5,15 In addition, negative body image15,16 and a decreased ability to maintain an active and functional life6 are associated with regret in patients with prostate cancer. Patient control over the decision-making process may also be a determinant of regret. In both breast and prostate cancers, where there may be opportunities for increased involvement in making decisions, participants can assume active, passive, or collaborative roles in the decision-making process.17 Studies show that when patients with breast and prostate cancers assume the role they desire, they are less likely to have decisional regret.17,18 Personal characteristics, including being unmarried,18 having greater anxiety, and less than college educational level,18,19 have also been associated with higher decisional regret in men with localized prostate cancer.

Finally, decisional conflict and uncertainty, a focus of the present paper, may be an important determinant of decisional regret. Patients may experience uncertainty, difficulty, anxiety, and decisional conflict during the decision-making process,20–22 and research demonstrates an association between decisional conflict and subsequent decisional regret.23 Patients with prostate cancer who experience decisional conflict and those who go on to experience negative outcomes such as side effects, especially those who experience both, might go on to regret their treatment decision.23 We have previously reported that stronger spiritual beliefs are associated with lower decisional conflict, greater decision-making satisfaction, and less decision-making difficulty.13 Given that a number of previous studies have shown that greater decisional conflict is associated with a higher likelihood of regretting one’s treatment decision,1,19,23,24 we anticipate that a way spirituality may impact well-being among cancer survivors is by reducing decisional conflict, thereby protecting against treatment decisional regret. Consistent with this hypothesis, Hu and colleagues1 found that spirituality was associated with decreased treatment regret in a cross-sectional study of low-income, uninsured men with prostate cancer, but they did not test potential reasons for this association.

The present study extends our previous analysis of a similar sample25 in significant ways. The goal of this study was to answer 2 questions1: Do men diagnosed with clinically localized prostate cancer who have stronger spiritual beliefs prior to treatment experience lower decisional regret 6 months post treatment? and2 Does decisional conflict partially mediate the association between spirituality and decisional regret? Testing whether strength of spiritual beliefs prior to treatment is causally related to decisional regret 6 months after treatment is important because regret is a key indicator of whether men have made a good treatment decision.12 Furthermore, if quality of the decision-making experience mediates this effect, then this gives us insight into the long-term value of incorporating spirituality-based elements into treatment decision-making resources such as decision-making tools and counseling by social workers, psychologists, and chaplains.

Finally, in previous studies, optimism, or generalized expectancies for positive outcomes in life,26 and resilience, the ability to recover from stressors,27 have played a role in the relationship between spiritual beliefs and adjustment during illness.26,28,29 We thus included these variables in our models for the current study.

2 |. METHODS

2.1 |. Procedure

Data for the current analyses are from a larger multi-site longitudinal study of treatment decision-making in men newly diagnosed with prostate cancer, recruited from 5 clinical facilities (2 academic cancer centers and 3 community practices) between 2010 and 2014. Participants were approached at or shortly after diagnosis when they completed an informed consent and initial baseline questionnaire. Participants who were unable to complete the questionnaire returned it by mail. Subsequent surveys were either mailed in or completed at follow-up visits. Data sources included the baseline questionnaire, a second mail-in questionnaire completed after participants had made their treatment decision but before they were treated, a follow-up survey completed 6 months after treatment, and participant medical records. Study procedures were institutional review board approved.

2.2 |. Participants

Of 3337 patients approached to participate in the study, 2476 (74.2%) consented to participate and 2008 completed the first survey. At the time of the analyses, 1152 of those who completed baseline data had data for the 3 questionnaires of interest, as well as medical record-abstracted clinical data. Cases with missing data on any of the variables included in the multivariable model were dropped (n = 30), as were participants who reported “other” race/ethnicity (n = 29). Analyses were performed on data from 1093 individuals (94.9% of the final sample).

2.3 |. Measures

2.3.1 |. Predictor variable

Spirituality was assessed after the treatment decision but prior to treatment with the functional assessment of chronic illness therapy—spiritual well-being scale (FACIT-Sp).30 The FACIT-Sp is a 12-item instrument that measures global beliefs assessing (a) faith during illness and (b) the sense of meaning and purpose in illness provided by spirituality (α = 0.86). Scores are summative (range = 0–48), and higher scores indicate greater spirituality.

2.3.2 |. Hypothesized mediating variable

Decisional conflict was also assessed after the participants had made their treatment decision and prior to treatment. We utilized the 16-item decisional conflict scale,31 which assesses degree of uncertainty about the decision, feelings of being uninformed or unclear about personal values, or whether the choice was made appropriately (α = 0.89). Scores are summative (range = 0–100), with higher scores indicating greater conflict.

2.3.3 |. Outcome variable

Decisional regret, the extent to which men regretted their treatment decision, was assessed by using the 5-item decision regret scale23 (α = 0.89) at 6 months post treatment. Level of decisional regret was assessed with ratings of agreement with statements such as, “I regret the choice that was made” and “I would go for the same choice if I had to do it over again.” Responses on the scale are summative (range = 0–100), with higher scores indicating greater decisional regret.

2.3.4 |. Covariates

Optimism was assessed at baseline with the Life Orientation Test—revised,26 measuring the participants’ level of optimism based on the extent to which the respondents agree with statements including, “I hardly ever expect things to go my way” and “I’m always optimistic about my future.” The participants respond to 6 test items and 4 filler items. Scores on the 6-item scale are summative (range = 6–30), with higher scores indicating greater levels of optimism (α = 0.83).

Resilience was assessed at baseline with the brief resilience scale.27 Items assess agreement with statements such as, “I tend to bounce back quickly after hard times” and “It is hard for me to snap back when something bad happens” (α = 0.86). Scores on this 6-item instrument are averaged (range = 1–5).

2.3.5 |. Demographic data and clinical variables

Based upon previous work exploring decisional regret in localized prostate cancer, we included the following covariates in the multivariable model.1 Demographic and clinical data were assessed with the baseline questionnaire completed shortly after diagnosis and medical record abstraction completed after treatment. Biopsy Gleason score, a grading of prostate cancer where higher scores indicate higher grade cancer, was abstracted from the patient’s medical record. The participants self-reported highest level of education completed (less than high school, high school, bachelor’s degree, master’s degree, doctoral degree, and professional degree), date of birth from which the researchers calculated age at diagnosis, marital status (single/never married/divorced/widowed vs married/cohabitating), and race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic black, non-Hispanic white, and Hispanic, hereafter referred to as black, white, and Hispanic). The clinic site where participants were recruited was recorded by participant recruiters.

2.4 |. Statistical analyses

All analyses were conducted with Stata Statistical software, version 13.32 We performed univariate and multivariable linear regressions with robust standard errors to examine the association between spirituality and decisional regret while controlling for optimism, resilience, Gleason score, education, age at diagnosis, race/ethnicity, marital status, and recruiting site. We did not include decisional conflict in the model because we had hypothesized that this was a mediator of the effect of spirituality on regret. We then tested for mediation by using path analysis to test whether decisional conflict mediated the relationship between spirituality and decisional regret 6 months post treatment, controlling for the same covariates. Income was not included in either the multivariable regression or structural equation model due to the large number of missing values for the variable (15.28%). Income was associated with education which was included in the models (r = 0.41, P < .001).

3 |. RESULTS

3.1 |. Descriptive statistics

Our total sample included 1093 participants. It was predominately white (84%), and 57.5% had a college degree or greater. The mean age at diagnosis was 63.18 (SD = 7.75), and 89.30% had a Gleason score of 6 or 7 (see Table 1 for participant characteristics and mean scores for spirituality, decisional regret, decisional conflict, optimism, and resilience).

TABLE 1.

Participant characteristics (total n = 1093)

| Characteristic | n | % or mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Gleason score | ||

| 6 | 463 | 42.36% |

| 7 | 513 | 46.94% |

| 8 | 77 | 7.04% |

| 9 | 39 | 3.57% |

| 10 | 1 | 0.09% |

| Education | ||

| <High school | 20 | 1.83% |

| HS/GED | 297 | 27.17% |

| Some college | 148 | 13.54% |

| Bachelor’s degree | 298 | 27.26% |

| Master’s degree | 216 | 19.76% |

| Doctorate | 53 | 4.85% |

| Professional | 61 | 5.58% |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White | 918 | 83.99% |

| Black | 107 | 9.79% |

| Hispanic | 68 | 6.22% |

| Marital status | ||

| Not married/cohabitating | 157 | 14.36% |

| Married/cohabitating | 936 | 85.64% |

| Age at diagnosis | 1093 | 63.18 (7.75) |

| Spiritualitya (0–48) | 1093 | 36.13 (7.85) |

| Decisional regretb (0–100) | 1093 | 12.72 (15.87) |

| Decisional conflicta (0–100) | 1090 | 7.78 (10.07) |

| Optimisma,6–30 | 1093 | 22.91 (4.02) |

| Resiliencea,1–5 | 1093 | 3.85 (0.65) |

Spiritual well-being, decisional conflict, optimism, and resilience were assessed after patients made their treatment decision but prior to treatment.

Decisional regret was assessed 6 months post treatment.

3.2 |. Unadjusted predictors of decisional regret

In unadjusted analyses, greater spirituality was associated with less decisional regret (b = −0.42; 95% confidence interval (CI) = −0.53, −0.30; P < .001, η2 = 0.043). Greater decisional conflict was significantly associated with greater decisional regret (b = 0.47; 95% CI = 0.39, 0.56; P < .001, η2 = 0.094). Among covariates, a higher Gleason score was associated with greater regret (b = 1.49; 95% CI = 0.28, 2.71; P = .02, η2 = 0.005), and participants who were black (b = 3.70; 95% CI = 0.62, 6.78; P = .02, η2 = 0.005) or Hispanic (b = 5.61; 95% CI = 1.73, 9.50; P < .01, η2 = 0.007) reported significantly greater regret than whites. Participants who reported greater levels of optimism (b = −0.73; 95% CI = −0.96, −0.50, P < .001, η2 = 0.035) and resilience (b = −4.39; 95% CI = −5.79, −2.98; P < .001, η2 = 0.032) reported significantly lower levels of regret, as did those with a higher educational level (b = −1.22; 95% CI = −1.84, −0.60; P < .001, η2 = 0.013).

3.3 |. Adjusted predictors of decisional regret

In the multivariable model (Table 2), greater spirituality was associated with less decisional regret (b = −0.39; 95% CI = −0.53, −0.26; P < .001, partial η2 = 0.024). Of covariates, only race/ethnicity was significantly associated with regret. Participants who were black (b = 4.90; 95% CI = 1.29, 8.51; P = 0.01, partial η2 = 0.007) or Hispanic (b = 5.39; 95% CI = 0.54, 10.25; P = 0.03, partial η2 = 0.004) had significantly greater levels of decisional regret when compared with white participants. It is important to note that the size of the spirituality effect was larger than for any other predictors in the model.

TABLE 2.

Multivariable model of effect of spirituality on decisional regreta (n = 1093)

| Predictor Variable | Bb | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spiritualityc | −0.39 | [−0.53, −0.24] | <0.001 |

| Optimismc | −0.17 | [−0.51, 0.18] | 0.35 |

| Resiliencec | −1.65 | [−3.78, 0.49] | 0.13 |

| Chart abstracted Gleason score | 0.92, 95% | [−0.38, 2.22] | 0.16 |

| Education | −0.52, 95% | [−1.18, 0.14] | 0.13 |

| Age at diagnosis | 0.01, 95% | [−0.13, 0.15] | 0.89 |

| Race | |||

| African American | 4.89, 95% | [1.29, 8.50] | 0.01 |

| Hispanic | 5.38, 95% | [0.53, 10.24] | 0.03 |

| Marital status | −1.85 | [−5.07, 1.37] | 0.26 |

Referent groups were white for race/ethnicity, high school, and less for education.

Decisional regret was assessed 6 months post treatment.

Unstandardized B-weight coefficients.

Spirituality, optimism, and resilience were assessed after patients made their treatment decision but prior to treatment.

To verify that both FACIT-Sp subscales (having a sense of peace and meaning and faith during illness) were associated with decisional regret after controlling for covariates, we tested the multivariable models by using scores on the subscale as the primary predictors. The scores on the meaning/peace subscale were associated with less decisional regret (b = −0.78; 95% CI = −1.02, −0.54; P < .001, partial η2 = 0.036), and the scores on the faith in illness subscale were associated with less decisional regret (b = −0.32; 95% CI = −0.56, −0.07; P = .01, partial η2 = 0.006).1

3.4 |. Mediational analysis

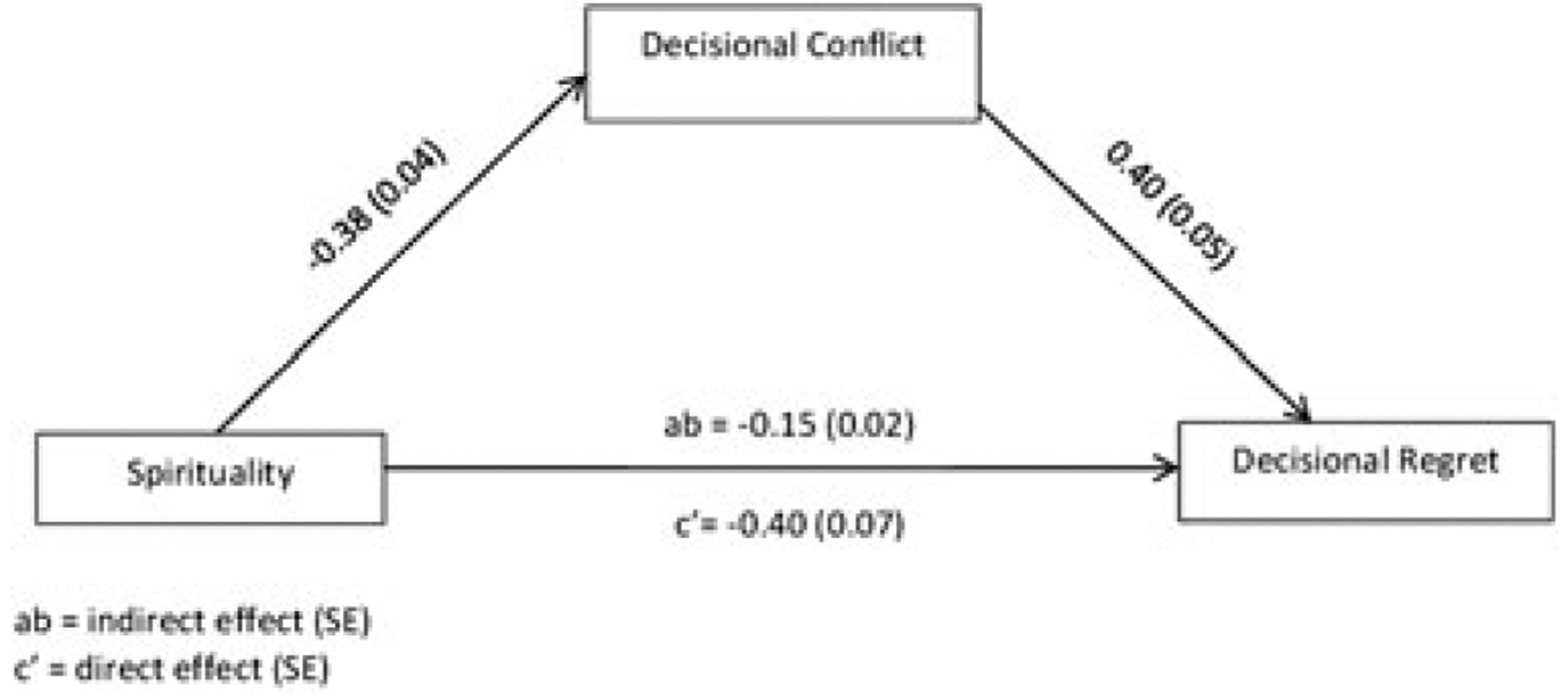

We previously reported that spirituality was associated with decisional conflict. We hypothesized that the effect of spirituality on regret might be at least partially mediated through decisional conflict. Controlling for covariates, decisional conflict did partially mediate the relationship between spirituality and decisional regret (Figure 1). The figure presents the coefficients and associated standard errors for the decisional regret mediational model. There was a significant indirect effect of spirituality on regret mediated through decisional conflict (b = −0.16; 95% CI = −0.21, −0.12; P < .001). Decisional conflict was a partial mediator (39% of the total effect); the direct effect of spirituality on decisional regret remained significant (b = −0.49; 95% CI = −0.46, −0.31; P < .001).2,3

FIGURE 1.

Unstandardized coefficients and associated standard errors for the decisional regret model are presented. In the model, decisional conflict after making treatment decision but before treatment partially mediates the influence of spirituality on decisional regret 6 months after treatment at P < .05. Although not illustrated, demographic and clinical characteristics (Gleason score, education, age at diagnosis, marital status, and race/ethnicity), optimism, and resilience were included in the model as control variables

4 |. DISCUSSION

We examined the relationship between spirituality assessed prior to treatment and decisional regret assessed 6 months after treatment of patients with prostate cancer. As predicted, higher levels of spirituality were associated with less decisional regret, and this relationship was partially mediated by decisional conflict. Both were true after accounting for patients’ clinical and demographic characteristics, type of treatment received, and optimism and resilience, personality characteristics previously shown to be associated with spirituality.26,28,29,33 Study results are consistent with the cross-sectional analysis by Hu and colleagues1 that greater spirituality was associated with lower decisional regret in a sample of low-income, uninsured men with prostate cancer. The present findings complement this previous work, as they are based on a large sample of insured men that was assessed longitudinally. Our study also builds upon our previous work in which we found that spirituality was associated with greater decision-making satisfaction, less decisional conflict, and less decision-making difficulty.13 In the present study, we extend this work by identifying a pathway through which spirituality influences regret.

There are a number of ways spirituality might influence decisional conflict and, ultimately, decisional regret in men with localized prostate cancer. First, in our previous work,13 we argue that spiritual beliefs may help men clarify their priorities and values when making their treatment decision, thereby decreasing decisional conflict. Second, spiritual beliefs may encourage patients to positively reappraise the treatment decision process as an opportunity to gain insights about life or make meaning out of their illness.34 In addition, the ability to reframe the treatment decision-making process as a challenge rather than a threat might increase an individual’s perceived self-efficacy for decision-making behaviors such as information seeking and processing. It might also reduce anxiety. Emotional distress can limit patients with prostate cancer’s ability to process new information about their disease,35 and basic behavioral research has demonstrated that it may cause people to avoid decision making altogether.36 If spiritual beliefs reduce anxiety and foster confidence in one’s ability to take the steps necessary to make a good treatment decision, then they may reduce decisional regret because individuals ultimately make involved and informed decisions. Third, feeling supported by a higher power may lead to increased confidence in having made the best possible decision (i.e., lower decisional conflict), reducing the likelihood of eventual decisional regret.

Decisional conflict was a partial mediator of the relationship between spirituality and decisional regret, and therefore, spirituality is affecting decisional regret through other means as well. Patients who believe, for example, that their illness is part of a divine plan from a higher power, may engage in more positive reframing and acceptance of suffering from treatment-associated side effects or uncertainty about prognosis. These individuals should be less likely to regret their treatment decision. Also, the effect size for the association between the meaning/peace subscale of the FACIT-Sp and regret in the multivariate model was larger than that of the faith subscale. It is possible that men regret their treatment decision less if they believe that this universe is purposeful and that things happen for a reason.

The fact that decisional regret in prostate cancer is such an important facet of well-being in cancer survivorship1,2,19,37,38 provides an impetus to identify resources to assist with the decision making under uncertainty. There is increasing recognition that spiritual needs of patients with cancer are often unmet and that patients would benefit if providers engaged them in discussions about their spiritual beliefs and implications of their beliefs for treatment planning and psychological adjustment.39 Incorporation of spiritual beliefs into clinical care for patients with cancer is typically most prevalent in end-of-life supportive care for terminal patients,39 but application during the decision-making phase is novel and may be a helpful addition. Such support after diagnosis of illness could help elicit potentially latent beliefs that can be utilized as resources in the positive reappraisal of decision-making challenges. A psychologist or spiritual support liaison, for example, could meet with newly diagnosed patients to discuss how spiritual beliefs might be utilized as resources. These discussions may support those with existing spiritual beliefs, including individuals with latent spiritual beliefs that they have not fully articulated. Patients may benefit from spiritual supportive care that helps clarify and make salient their spiritual values and beliefs. For these individuals, spirituality allows for deep consideration of what is most important in an individual’s life, so that they can make the best treatment decision based on the information presented. Reflecting on spiritual beliefs may also lead to feelings of support and strength to be able to proceed through the steps of the decision-making process. It may help patients think of ways they can mobilize support and resources from their religious affiliation if they have one, prayer, contemplation, or religious texts. Whether this kind of spiritual decision-making support might be acceptable in the form of a structured decision aid could be explored in future research.

5 |. LIMITATIONS AND STRENGTHS

Use of the FACIT-Sp to assess spirituality is not without limitations. The instrument does not assess potentially maladaptive spiritual beliefs (e.g., feelings of abandonment by a higher power or that illness is a punishment). Also, there may be ambiguity regarding what the FACIT-Sp measures. Although the scale has been referred to as measure of quality of life,30 the items were developed based on input of “cancer patients, psychotherapists, and religious/spiritual experts (e.g., hospital chaplains), who were asked to describe the aspects of spiritual and/or faith that contribute to quality of life”30 (pp. 50–51). Accordingly, the items tend to assess enduring cognitive representations about the self and the self’s relationship to the world (e.g., “I feel a sense of purpose in my life,” “I have a reason for living,” and “I find comfort in my faith or spiritual beliefs”) rather than quality of life per se. These beliefs are likely influential in coping appraisal processes that ultimately influence the physiological and emotional states that partially constitute well-being, as well as a basis for appraisals of overall life satisfaction. We suggest that the FACIT-Sp therefore assesses cognitions that are important determinants of well-being or quality of life. It would be valuable to conduct additional studies to better understand how other measures of spirituality are related to the quality of the treatment decision-making process and decisional regret. For example, spirituality as measured by the FACIT-Sp is distinct from but may overlap with religious affiliation and involvement. Involvement in a religious organization may provide a source of resources for coping with the treatment decision (e.g., social support from other members and religious leaders). Future studies might examine whether religious affiliation moderates the association between spirituality and regret or is even an additional determinant of regret. Other weaknesses include sample attrition and lack of sample diversity. Finally, associations between spirituality and decisional regret were modest.

Examination of spirituality and treatment decision-making and regret is novel, with the exception of the work by Hu and colleagues.1 Inferences from the current study are strengthened by the large sample and longitudinal design, allowing the ability to make causality inferences. Including optimism and resilience, constructs associated with spirituality, allows the opportunity to account for potential confounding of these personality dimensions and spiritual beliefs. Finally, in our previous study,13 we utilized a self-reported Gleason score; however, in the current analysis, we used a medical record-abstracted Gleason score. Finally, the results from the present study show that the relationship between spirituality and decisional conflict holds regardless of how Gleason score was assessed.

6 |. CONCLUSION

In summary, these results extend our current knowledge of spirituality and adjustment to illness, indicating that spiritual beliefs may help patients with prostate cancer navigate treatment decision-making by reducing decisional conflict, and ultimately, decisional regret after prostate cancer treatment. Decisional regret is one of many important patient-centered outcomes related to overall quality of life. Preventing decisional regret has become a key intervention target.40 The findings suggest the importance of initiating spiritual supportive care as early as possible to influence the decision-making process, thereby mitigating regret and positively impacting quality of life.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no financial disclosures or conflicts to report.

When we used a 3-factor model and regressed decisional regret on each of the faith, peace, and meaning subscales, higher scores on each scale were associated with lower decisional regret (results not shown).

In Mollica et?al. (2015), we reported significant relations between spirituality and decision-making satisfaction and difficulty. Associations between the latter and decisional regret are not reported here in detail to avoid redundancy; however, in analyses with the same sample, decision-making satisfaction and difficulty were associated with decisional regret (satisfaction: b = −9.31; 95% CI = −11.52, −7.09; P < .001; partial η2 = 0.091; difficulty: b = 1.23; 95% CI = 0.91, 1.55; P < .001; partial η2 = 0.043). There were also small but significant indirect effect of spirituality on regret mediated through decision-making satisfaction (b = −0.14; 95% CI = −0.19, −0.10; P < .001) and difficulty (b = −0.08; 95% CI = −0.12, −0.05; P < .001).

These results hold true when controlling for both quality of life and treatment type in both multivariable and mediational models.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hu J, Kwan L, Krupski T, et al. Determinants of treatment regret in low-income, uninsured men with prostate cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2008;72(6):1274–1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clark J, Wray N, Ashton C. Living with treatment decisions: regret and quality of life among men treated for metastatic prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(1):72–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steer A, Aherne N, Gorzynski K. Decision regret in men undergoing dose-escalated radiation therapy for prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2013;86(4):716–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davison B, So A, Goldenberg S. Quality of life, sexual function and decisional regret at 1 year after surgical treatment for localized prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2007;100:780–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gilts C, Lorenzo C, Pettaway C, Parker P. Treatment regret and quality of life following radical prostatectomy. Support Care Cancer 2013;21(12):1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Diefenbach M, Mohamed N, Horwitz E, Pollak A. Longitudinal associations among quality of life and its predictors in patients treated for prostate cancer: the moderating role of age. Psychological Health Medicine. 2008;13:146–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klotz L, Zhang LY, Lam A, Nam R, Mamedov A, Loblaw A. Clinical results of long-term follow-up of a large, active surveillance cohort with localized prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(1):126–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mohler J, Bahnson RR, Boston B, et al. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: prostate cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2010;8(2):162–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bill-Axelson A, Holmberg L, Ruutu M. Radical prostatectomy versus watchful waiting in early prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(18):1708–1717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cooperberg M, Broering J, Carroll P. Time trends and local variation in primary treatment of localized prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(7):1117–1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilt T, Brawer M, Jones K. Radical prostatectomy versus observation for localized prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(3):203–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aning JJ, Wassersug RJ, Goldenberg SL. Patient preference and the impact of decision-making aids on prostate cancer treatment choices and post-intervention regret. Current oncology. 2012;19(Suppl 3):S37–S44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mollica M, Underwood WI, Homish GG, Homish DL, Orom H. Spirituality is associated with better prostate cancer treatment decision making experiences. J Behav Med. 2015; in press [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kinsella J, Acher P, Ashfield A. Demonstration of erectile management techniques to men scheduled for radical prostatectomy reduces long term regret: a comparative cohort study. BJU Int. 2012;109(2):254–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parekh A, Chen M, Hoffman K. Reduced penile size and treatment regret in men with recurrent prostate cancer after surgery, radiotherapy plus androgen deprivation, or radiotherapy alone. Urology. 2013;81(1):130–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sheehan J, Sherman K, Lam T. Regret associated with the decision for breast reconstruction: the association of negative body image, distress and surgery characteristics with decision regret. Psychology and Health. 2008;23(2):207–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mancini J, Genre D, Dalenc F J, Kerbrat P, Martin A, Roche H, et al. Patient’s regret after participating in a randomized controlled trial depended on their involvement in the decision making. J Clin Epidemiol 2012;65:635–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berry D, Wang Q, Halpenny B, Hong F. Decision, preparation, satisfaction and regret in a multi-center sample of men with newly diagnosed localized prostate cancer. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;88(2):262–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hu J, Kwan L, Saigal C, Litwin M. Regret in men treated for localized prostate cancer. J Urol. 2003;169:2279–2283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dale W, Bilir P, Han M, Meltzer D. The role of anxiety in prostate carcinoma: a structured review of the literature. Cancer. 2005;104:467–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zeliadt S, Ramsey S, Penson D, et al. Why do men choose one treatment over another? A review of patient decision making for localized prostate cancer. Cancer. 2006;106(9):1865–1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Orom H, Penner L, West B, Downs T, Rayford W, Underwood WI. Personality predicts prostate cancer treatment decision-making difficulty and satisfaction. Psycho-oncology. 2009;18:290–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brehaut J, O’Connor A, Wood T, Hack T, Siminoff L, Gordon E. Validation of a decision regret scale. Med Decis Making. 2003;23(4):281–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Connolly T, Reb J. Regret in cancer-related decisions. Health Psychol. 2005;24:S29–S34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mollica MA, Underwood W 3rd, Homish GG, Homish DL, Orom H. Spirituality is associated with better prostate cancer treatment decision making experiences. J Behav Med. 2015; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scheier M, Carver C, Bridges M. Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): a re-evaluationof the Life Orientation Test. Journal of Personal Social Psychology. 1994;67:1063–1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith B, Dalen J, Wiggins K, Tooley E, Christopher P, Bernard J. The brief resilience scale: assessing the ability to bounce back. Int J Behav Med. 2008;15:194–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Salsman J, Brown T, Brechting E, Carlson C. The link between religion and spirituality and psychological adjustment: the mediating role of optimism and social support. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2005;31:522–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stewart D, Yuen T. A systematic review of resilience in the physically ill. Psychosomatics. 2011;52(3):199–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peterman AH, Fitchett G, Brady MJ, Hernandez L, Cella D. Measuring spiritual well-being in people with cancer: the functional assessment of chronic illness therapy—spiritual well-being scale (FACIT-Sp). Ann Behav Med. 2002;24(1):49–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O’Connor A. Validation of a decisional conflict scale. Med Decis Making. 1995;15:25–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.StataCorp LP. Stata Statistical Software: Release 13. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gall T, Charbonneau C, Clarke N, Grant K. Understanding the nature and role of spirituality in relation to coping and health: a conceptual framework. Canadian Psychology. 2005;46(2):88–104. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Park C. Religiousness/spirituality and health: a meaning systems perspective. J Behav Med. 2007;30:319–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hovey RB, Cuthbertson KE, Birnie KA, Robinson JW, Thomas BC, Massfeller HF. The influence of distress on knowledge transfer for men newly diagnosed with prostate cancer. J Cancer Educ. 2012;27:540–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Luce MF, Bettman JR, Payne JW. Choice processing in emotionally difficult decisions. J Exp Psychol Learn Mem Cogn. 1997;23:384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Davison B, Goldenberg S. Decisional regret and quality of life after participating in medical decision-making for early-stage prostate cancer. Br J Urol. 2003;91:14–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Krupski T, Kwan L, Fink A, Sonn G, Maliski S, Litwin M. Spirituality influences health related quality of life in men with prostate cancer. Psycho-oncology. 2006;15:121–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Puchalski CM. Spirituality in the cancer trajectory. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:49–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hack T, Degner L, Watson P. Do patients benefit from participating in medical decision making? Longitudinal follow-up of women with breast cancer. Psycho-oncology. 2006;15(1):9–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]