Abstract

Background

We aimed to systematically review the clinical and laboratory features of patients with the multisystem inflammatory syndrome in pediatrics diagnosed during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Data sources

A literature search in Web of Science, PubMed, Scopus, and Science Direct was made up to June 29, 2020.

Results

Analysis of 15 articles (318 COVID-19 patients) revealed that although many patients presented with the typical multisystem inflammatory syndrome in pediatrics, Kawasaki-like features as fever (82.4%), polymorphous maculopapular exanthema (63.7%), oral mucosal changes (58.1%), conjunctival injections (56.0%), edematous extremities (40.7%), and cervical lymphadenopathy (28.5%), atypical gastrointestinal (79.4%) and neurocognitive symptoms (31.8%) were also common. They had elevated serum lactic acid dehydrogenase, D-dimer, C-reactive protein, procalcitonin, interleukin-6, troponin I levels, and lymphopenia. Nearly 77.0% developed hypotension, and 68.1% went into shock, while 41.1% had acute kidney injury. Intensive care was needed in 73.7% of cases; 13.2% were intubated, and 37.9% required mechanical ventilation. Intravenous immunoglobulins and steroids were given in 87.7% and 56.9% of the patients, respectively, and anticoagulants were utilized in 67.0%. Pediatric patients were discharged after a hospital stay of 6.77 days on average (95% CI 4.93–8.6).

Conclusions

Recognizing the typical and atypical presentation of the multisystem inflammatory syndrome in pediatric COVID-19 patients has important implications in identifying children at risk. Monitoring cardiac and renal decompensation and early interventions in patients with multisystem inflammatory syndrome is critical to prevent further morbidity.

Keywords: COVID-19, Kawasaki-like syndrome, Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in pediatrics, SARS-CoV-2

Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has led to a global pandemic with significant morbidity and mortality [1]. The pediatric population appears to be affected in a much smaller number than adults, with only 1.7% of cases in the United States occurring in children younger than 18. In other European countries, the number of cases in children is less than 2% [2–4]. Currently, it is unclear whether this is due to lower infection susceptibility in children or if the asymptomatic disease is much more common in those under the age of 18 [5, 6].

Significant numbers of children and teenagers who tested positive for COVID-19 antibodies have developed a severe inflammatory condition with many Kawasaki disease characteristics [7]. As case reports pile up, the world is suddenly paying attention to this pediatric condition that may be related to COVID-19 [8]. This condition is named “multisystem inflammatory syndrome in pediatrics” which shares many features with Kawasaki disease and toxic shock syndrome [9, 10]. Kawasaki disease is a rare acute pediatric vasculitis. It usually involves small- to medium-sized arteries in various organs and tissues and can cause coronary artery aneurysms, myocardial infarction, and pericarditis [11]. It is characterized by fever, exanthema, lymphadenopathy, conjunctival injection, and changes to the mucosa and extremities. Kawasaki disease is relatively uncommon, with an incidence rate of 20.8 per 100,000 in the United States, mainly in children aged 5 years or younger [12]. Unexpectedly, published reports of illness like “multisystem inflammatory syndrome in pediatrics” occurring in China are lacking, with most reports of hospitalized COVID-19 children in China indicating that their illness is not severe [13, 14]. The etiology of the multisystem inflammatory syndrome remains unknown; however, antigen-driven delayed immune reaction following viral infection in genetically susceptible individuals is the current leading hypothesis [11]. In the last two decades, the coronavirus family has been proposed to be one of the Kawasaki-like syndrome triggers. Human New Haven coronavirus (HCoV-NH) was identified in the respiratory secretions of 72.7% of children with Kawasaki disease [15], and positive CoV-229E antibodies were detected by immunofluorescence assay in patients with Kawasaki disease [16], eliciting a putative link with COVID-19 disease.

Verdoni et al. described an outbreak of a Kawasaki-like disease occurring in Bergamo, Italy, at the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic [17]. As of May 21, other suspected or confirmed children of similar presentations have been reported throughout the United States [18]. This Kawasaki-like disease appears to cause a hyperinflammatory shock state. Hypotension with a requirement for fluid resuscitation seems to be common [19]. Some patients required inotropic support. In addition, patients with this syndrome appear to respond well to intravenous immunoglobulin. However, the disease course seems more severe than the typical Kawasaki disease as adjunct anti-inflammatory treatments were necessary for several patients, with some requiring high-dose corticosteroids. The use of biologics, such as infliximab, has also been described [17, 20].

Despite these findings, much remains unknown about this rare Kawasaki-like disease (i.e., multisystem inflammatory syndrome in pediatrics). Some children have needed intensive care unit (ICU), others recovered quickly. The goal of this meta-analysis was to summarize the clinical and laboratory features of patients with the multisystem inflammatory syndrome in pediatrics diagnosed during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

Search strategy

This current meta-analysis was carried out according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) statement [21]. Relevant literature was retrieved from Web of Science, PubMed, Scopus, and Science Direct search engines up to June 29, 2020. Our search strategy included the following terms: (“Novel coronavirus 2019”, “2019 nCoV”, “COVID-19”, “Wuhan coronavirus,” “Wuhan pneumonia,” or “SARS-CoV-2”) and (“Kawasaki-like disease”, “Kawasaki-like syndrome”, “multisystem inflammatory syndrome”, “pediatric inflammatory syndrome”, or “pediatric inflammatory, multisystem syndrome”). Besides, we manually screened out the relevant potential article in the references selected. The above process was performed independently by three participants.

Study selection

No time or language restriction was applied. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) types of studies: retrospective, prospective, observational, descriptive or case–control studies reporting COVID-19 patients with the multisystem inflammatory syndrome; (2) subjects: diagnosed patients with COVID-19; (3) exposure intervention: COVID-19 patients diagnosed with reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)/antibody testing, radiological imaging, or both with the principal criteria of the syndrome (i) patients < 21 years presented with (ii) persistent fever ≥ 38.0 °C for ≥ 24 hours or report of subjective fever lasting ≥ 24 hours, (iii) severe illness leading to hospitalization, (iv) laboratory evidence of inflammation, including, but not limited to, one or more of the followings: an elevated C-reactive protein (CRP), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), fibrinogen, procalcitonin, D-dimer, ferritin, lactic acid dehydrogenase (LDH), or interleukin-6 (IL-6), elevated neutrophils, reduced lymphocytes and low albumin, (v) multisystem organ involvement (i.e. involving at least two systems), and (vi) laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection (by RT-PCR or antibody test during hospitalization) or an epidemiologic link to a person with Covid-19 [22]. In addition, according to the center for disease control and prevention, any pediatric death with evidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection, and if individuals fulfill full or partial criteria for Kawasaki disease but meet the case definition for multiple inflammatory syndrome, they should be considered as having this syndrome. The Kawasaki disease signs and symptoms that might be associated with the multisystem inflammatory syndrome include bilateral conjunctival injection, oral changes such as cracked and erythematous lips and strawberry tongue, cervical lymphadenopathy, extremity changes such as erythema or palm and sole desquamation, and polymorphous rash [23]. Lastly, (4) outcome indicators: the mean and standard deviation or median and interquartile range for COVID-19-related complications and mortality.

The following exclusion criteria were considered: (1) case reports, reviews, editorial materials, conference abstracts, summaries of discussions, (2) insufficient reported data information; or (3) in vitro or in vivo studies.

Data abstraction

Two investigators (RME and RM) separately conducted literature screening, data extraction, and literature quality evaluation, and any differences were resolved through a third reviewer (MHH). Information was extracted from eligible articles in a predesigned form in excel, including the last name of the first author, date and year of publication, journal name, study design, country of the population, and sample size. Variables were stratified into eight categories: demographic data, Kawasaki-like disease features, other clinical presentations, comorbidities, hospitalization, laboratory measurements, SARS-CoV-2 screening, and medications.

Statistical analysis

All data analyses were performed using OpenMeta[Analyst] [24] and comprehensive meta-analysis software version 3.0 [25]. First, a single-arm meta‐analysis for laboratory tests was performed. The mean or untransformed proportion and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were used to estimate pooled results from studies. A continuous random-effects model was applied using the DerSimonian–Laird (inverse variance) method [26, 27]. Heterogeneity was evaluated using Cochran’s Q statistic and quantified using I2 statistics, representing the total variation across studies beyond chance. Articles were considered to have significant heterogeneity between studies when the p value less than 0.1 or I2 > 50%. Finally, publication bias was assessed using a funnel plot and quantified using Begg’s and Mazumdar rank correlation with continuity correction and Egger’s linear regression tests. Asymmetry of the collected studies’ distribution by visual inspection or P value < 0.1 indicated obvious publication bias [28].

Results

Literature search

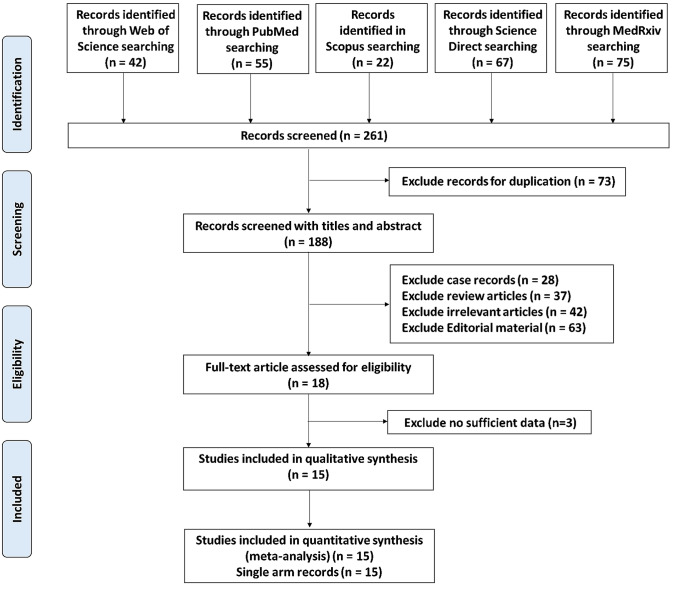

The flow chart summarizing the literature search of this meta-analysis study is illustrated in Fig. 1. A total of 261 articles were recorded using 5 major online databases (Web of Science, PubMed, Scopus, ScienceDirect, and MedRxiv) till June 29, 2020. After inspection of the retrieved records, 73 articles were removed due to duplication, and 188 records were recognized. Upon screening the title and abstract, our team excluded various articles, including case reports (n = 28), review articles (n = 37), irrelevant reports (n = 42), or editorial items (n = 63). A final of 18 records was appraised for eligibility, with 3 records excluded for no sufficient data. Eventually, a total of 15 eligible reports were identified for the quantitative assessment of this meta-analysis, with 15 records characterized single-arm analysis.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart for the systematic literature search

Characteristics of the included studies

The main characteristics of the included records in this meta-analysis are demonstrated in Table 1 [17, 20, 29–40]. The articles published online from May 6 until June 29, 2020, included five records from France [Paris (5)], five records from the USA [New York (4), and Pennsylvania (1)], four records from UK [London (2), and Birmingham (2)], and one record from Italy [Bergamo (1)]. A total of 318 children with a pediatric inflammatory, multisystem syndrome (Kawasaki-like disease) associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection were registered in this meta-analysis. Nine records were retrospective studies, another two were prospective studies, while descriptive case series accounted for four studies.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies in the meta-analysis

| First author | DOP | Journal name | City | Country | Regional geography | Study design | Sample Size | Mean age (SD) | Girls (%) | Boys (%) | PICU (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Riphagen et al. [20] | 6-May | The Lancet | London | UK | European | Case series | 8 | 8.87 (3.68) | 37.5 | 62.5 | 100 |

| Verdoni et al. [17] | 13-May | The Lancet | Bergamo | Italy | European | Retrospective | 10 | 7.93 (3.81) | 30 | 70 | NA |

| Chiotos et al. [29] | 28-May | J Ped Infect Dis Soc | Pennsylvania | USA | American | Case series | 6 | 8.5 (3.83) | 83.3 | 16.7 | 33.3 |

| Grimaud et al. [30] | 1-June | Ann Intensive Care | Paris | France | European | Retrospective | 20 | 9.17 (9.26) | 50 | 50 | 100 |

| Toubiana et al. [31] | 3-June | BMJ | Paris | France | European | Prospective | 21 | 9.4 (9.56) | 57 | 43 | 81 |

| Miller et al. [32] | 4-June | Gastroenterology | New York | USA | American | Retrospective | 44 | 9.43 (14.07) | 55 | 45 | NA |

| Perez-Toledo et al. [33] | 7-June | MedRxiv (Pre-print) | Birmingham | UK | European | Retrospective | 8 | 10 (5.19) | 37 | 63 | NA |

| Whittaker et al. [34] | 8-June | JAMA | London | UK | European | Retrospective | 58 | 9.57 (6.15) | 57 | 43 | NA |

| Cheung et al. [7] | 8-June | JAMA | New York | USA | American | Case series | 17 | 8.6 (10.52) | 53 | 47 | 88 |

| Blondiaux et al. [35] | 9-June | Radiology | Paris | France | European | Case series | 4 | 9.25 (2.75) | 75 | 25 | 100 |

| Pouletty et al. [36] | 11-June | Ann Rheum Dis | Paris | France | European | Retrospective | 16 | 9.07 (5.78) | 50 | 50 | 44 |

| Ramcharan et al. [37] | 12-June | Pediatr Cardiol | Birmingham | UK | European | Retrospective | 15 | 8.8 (3.56) | 26.7 | 73.3 | 53.3 |

| Kaushik et al. [38] | 14-June | The J of Pediatrics | New York | USA | American | Retrospective | 33 | 9.67 (5.19) | 39 | 61 | 100 |

| Capone et al. [39] | 14-June | J Pediatr | New York | USA | American | Retrospective | 33 | 8.9 (5.26) | 39 | 61 | 79 |

| Moisan-Delaunay et al. [40] | 29-June | MedRxiv (Pre-print) | Paris | France | European | Prospective | 25 | 9.1 (4.3) | 60 | 40 | NA |

All articles were published in 2020. DOP date of publication, PICU pediatric intensive care unit admission, Ref. reference number, NA not applicable

Demographic characteristics of pediatric patients

Our meta-analysis included 318 COVID-19 patients presenting with the multisystem inflammatory syndrome. Their mean age was 9.10 years (95% CI 8.49–9.71), while the mean BMI 19.34 kg/m2 (95% CI 17.86–20.82). The pooled prevalence of boys accounted for 50.5% across the studies. Proportion of Black patients was 36.8% (95% CI 26.3–47.4%) higher than the White (16.4%, 95% CI 10.7–22.1%) and Asian cohorts (13.6%, 95% CI 4.7–22.6%) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Pooled estimates of single-arm meta-analysis for COVID-19 patients

| Characteristics | # Studies | Sample size | Association measure | Effect size | Heterogeneity | Publication bias | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | 95% CI | P value | I2 | P value | P value | ||||

| Demographic data | |||||||||

| Age, y | 15 | 318 | M | 9.10 | 8.494, 9.714 | < 0.001 | 0.0% | 1.00 | 0.715 |

| Sex: (girls) | 15 | 318 | P | 49.50 | 43.0, 56.1 | < 0.001 | 27.89% | 0.15 | 0.775 |

| Sex: (boys) | 15 | 318 | P | 50.50 | 43.9, 57.0 | < 0.001 | 27.89% | 0.15 | 0.774 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 5 | 95 | M | 19.34 | 17.86, 20.82 | < 0.001 | 19.0% | 0.29 | 0.063 |

| Race: (Black) | 8 | 229 | P | 36.80 | 26.3, 47.4 | < 0.001 | 65.77% | 0.005 | 0.501 |

| Race: (Asian) | 7 | 185 | P | 13.60 | 4.70, 22.6 | 0.003 | 74.51% | < 0.001 | 0.032 |

| Race: (White) | 8 | 229 | P | 16.40 | 10.7, 22.1 | < 0.001 | 27.76% | 0.20 | 0.285 |

| SARS-CoV-2 screening | |||||||||

| Nasopharyngeal RT-PCR | 7 | 138 | P | 46.50 | 12.9, 80.1 | 0.007 | 96.25% | < 0.001 | 0.277 |

| Anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG | 8 | 167 | P | 69.60 | 48.9, 90.2 | < 0.001 | 91.31% | < 0.001 | 0.471 |

| C. Kawasaki dis criteria | |||||||||

| Fever | 9 | 177 | P | 82.40 | 69.8, 95.1 | < 0.001 | 94.23% | < 0.001 | 0.018 |

| Lips/oral cavity changes | 6 | 124 | P | 58.10 | 38.6, 77.6 | < 0.001 | 82.64% | < 0.001 | 0.585 |

| Conjunctival injection | 10 | 227 | P | 56.00 | 40.0, 71.9 | < 0.001 | 85.56% | < 0.001 | 0.227 |

| Rash | 11 | 235 | P | 63.70 | 53.8, 73.5 | < 0.001 | 59.62% | 0.006 | 0.267 |

| Changes to extremities | 4 | 101 | P | 40.70 | 12.9, 68.5 | 0.004 | 86.67% | < 0.001 | 0.537 |

| Cervical lymphadenopathy | 6 | 136 | P | 28.50 | 13.9, 43.1 | < 0.001 | 73.13% | 0.002 | 0.918 |

| Presentations | |||||||||

| Gastrointestinal | 14 | 303 | P | 79.40 | 68.1, 90.7 | < 0.001 | 92.48% | < 0.001 | 0.012 |

| Neurocognitive | 11 | 271 | P | 31.80 | 21.9, 41.8 | < 0.001 | 70.30% | < 0.001 | 0.757 |

| Respiratory | 8 | 232 | P | 29.60 | 19.6, 39.6 | < 0.001 | 66.65% | 0.004 | 0.948 |

| E. Comorbidities | |||||||||

| Asthma | 3 | 82 | P | 14.60 | 6.9, 22.2 | < 0.001 | 0.0% | 0.96 | NA |

| Obesity | 4 | 126 | P | 26.00 | 7.1, 44.9 | 0.007 | 85.99% | < 0.001 | 0.092 |

| Investigations | |||||||||

| Abnormal ECG | 6 | 89 | P | 55.30 | 45.1, 65.6 | < 0.001 | 0.0% | 0.88 | 0.365 |

| Abnormal Chest X-ray | 3 | 70 | P | 45.50 | 24.9, 66.0 | < 0.001 | 68.97% | 0.040 | 0.187 |

| Laboratory tests | |||||||||

| WBCs, × 109/L | 8 | 228 | M | 13.20 | 10.82, 15.59 | < 0.001 | 84.99% | < 0.001 | 0.198 |

| Lymphocytes, × 109/L | 9 | 208 | M | 0.93 | 0.737, 1.125 | < 0.001 | 70.06% | < 0.001 | 0.067 |

| Neutrophils, × 109/L | 4 | 115 | M | 12.67 | 8.56, 16.76 | < 0.001 | 87.44% | < 0.001 | 0.471 |

| Platelets, × 109/L | 9 | 239 | M | 180.01 | 154.4, 205.6 | < 0.001 | 65.77% | 0.003 | 0.027 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 7 | 106 | M | 10.4 | 9.55, 11.39 | < 0.001 | 80.20% | < 0.001 | 0.703 |

| Troponin, ng/L | 12 | 241 | M | 110.71 | 59.08, 162.3 | < 0.001 | 72.76% | < 0.001 | 0.426 |

| NT-proBNP, pg/mL | 12 | 241 | M | 5648.78 | 3823, 7474 | < 0.001 | 95.45% | < 0.001 | 0.374 |

| LDH, U/L | 5 | 158 | M | 637.21 | 358.7, 915.7 | < 0.001 | 96.02% | < 0.001 | 0.205 |

| ALT, U/L | 8 | 232 | M | 46.86 | 39.1, 54.6 | < 0.001 | 36.71% | 0.13 | 0.009 |

| AST, U/L | 4 | 127 | M | 52.89 | 45.9, 59.8 | < 0.001 | 0.0% | 0.56 | 0.299 |

| Albumin, g/L | 9 | 239 | M | 27.15 | 23.5, 30.7 | < 0.001 | 95.65% | < 0.001 | 0.324 |

| Creatinine, μmol/L | 6 | 151 | M | 74.93 | 59.4, 90.4 | < 0.001 | 38.58% | 0.14 | 0.039 |

| Sodium, mmol/L | 8 | 150 | M | 131.70 | 129.3, 134.1 | < 0.001 | 88.98% | < 0.001 | 0.094 |

| CRP, mg/L | 12 | 262 | M | 215.58 | 192.5, 238.7 | < 0.001 | 55.15% | 0.011 | 0.652 |

| ESR, mm/h | 4 | 102 | M | 64.64 | 54.28, 74.99 | < 0.001 | 38.30% | 0.18 | 0.335 |

| Ferritin, ng/mL | 9 | 194 | M | 763.24 | 658.8, 867.6 | < 0.001 | 16.93% | 0.29 | 0.018 |

| Fibrinogen, g/L | 4 | 144 | M | 6.24 | 4.68, 7.80 | < 0.001 | 96.03% | < 0.001 | 0.166 |

| Procalcitonin, ng/mL | 6 | 117 | M | 19.24 | 8.67, 29.80 | < 0.001 | 73.16% | 0.002 | 0.002 |

| Interleukin-6, pg/mL | 4 | 115 | M | 189.67 | 145.4, 233.8 | < 0.001 | 0.0% | 0.512 | 0.122 |

| D-dimer, μg/mL | 8 | 191 | M | 3.79 | 2.57, 5.02 | < 0.001 | 89.25% | < 0.001 | 0.025 |

| Prothrombin time, sec | 3 | 56 | M | 4.09 | 2.92, 5.27 | < 0.001 | 99.07% | < 0.001 | 0.318 |

| Complications | |||||||||

| Shock | 5 | 158 | P | 68.10 | 51.9, 84.3 | < 0.001 | 80.67% | < 0.001 | 0.085 |

| Hypotension | 5 | 75 | P | 77.00 | 56.9, 97.0 | < 0.001 | 82.18% | < 0.001 | 0.147 |

| Acute kidney injury | 4 | 141 | P | 41.10 | 15.0, 67.1 | 0.002 | 91.83% | < 0.001 | 0.665 |

| PICU admission | 10 | 173 | P | 73.70 | 60.3, 87.1 | < 0.001 | 86.52% | < 0.001 | 0.137 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 9 | 198 | P | 37.90 | 28.3, 47.6 | < 0.001 | 46.46% | 0.060 | 0.887 |

| Intubation | 2 | 102 | P | 13.2 | 0.5, 82.1 | 0.27 | 97.16% | < 0.001 | NA |

| Length of stay, days | 5 | 112 | M | 6.77 | 4.93, 8.60 | < 0.001 | 86.81% | < 0.001 | 0.392 |

| Medications | |||||||||

| Epinephrine | 3 | 61 | P | 40.20 | 7.2, 73.2 | 0.017 | 86.03% | < 0.001 | 0.942 |

| Norepinephrine | 3 | 61 | P | 45.10 | 9.0, 81.2 | 0.014 | 91.26% | < 0.001 | 0.470 |

| Milrinone vasodilator | 3 | 61 | P | 42.90 | 2.7, 83.0 | 0.036 | 91.94% | < 0.001 | 0.954 |

| Intravenous Ig | 12 | 258 | P | 87.70 | 80.8, 94.7 | < 0.001 | 77.75% | < 0.001 | 0.001 |

| Steroids | 7 | 188 | P | 56.90 | 33.6, 80.2 | < 0.001 | 94.68% | < 0.001 | 0.878 |

| Anakinra (anti-IL1) | 5 | 184 | P | 9.40 | 4.6, 14.2 | < 0.001 | 20.31% | 0.28 | 0.155 |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 2 | 33 | P | 13.5 | 5.1, 31.0 | 0.001 | 5.99% | 0.30 | NA |

| Infliximab (anti-TNF) | 2 | 91 | P | 8.5 | 2.0, 29.6 | 0.002 | 74.61% | 0.047 | NA |

| Anticoagulants | 8 | 170 | P | 67.00 | 47.6, 86.3 | < 0.001 | 94.12% | < 0.001 | 0.447 |

The random-effects model was applied. Association measure: pooled mean (M) was estimated for quantitative variables and untransformed proportions (P) were calculated for categorical events; I2: the ratio of true heterogeneity to total observed variation; publication bias: assessed by Egger’s test. CI confidence interval; BMI body mass index; Gastrointestinal symptoms included vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain; Neurocognitive symptoms included headache, irritability, lethargy, vision change; Respiratory symptoms included cough and dyspnea; ECG electrocardiogram; PICU pediatric intensive care unit; NT-proBNP N‐terminal-prohormone B‐type natriuretic peptide; CK creatine kinase; LDH lactate dehydrogenase; ALT alanine aminotransferase; AST aspartate aminotransferase; CRP c-reactive protein; ESR erythrocyte sedimentation rate; WBCs white blood cell counts; RT-PCR reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction; Ig immunoglobulins; Anti-TNF anti-tumor necrosis

Clinical presentations of COVID-19 patients

Young patients underwent confirmatory tests for COVID-19 disease by either RT-PCR of nasopharyngeal swab (proportion = 46.5%, 95% CI 12.9–80.1%) or anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG analysis (proportion = 69.6%, 95% CI 48.9–90.2%) (Table 2). For the clinical criteria of the multisystem inflammatory syndrome and Kawasaki-like features, fever (proportion = 82.4%, 95% CI 69.8–95.1%) and polymorphous maculopapular exanthema (proportion = 63.7%, 95% CI 53.8–73.5%) were the most frequent principal features, followed by changes of lips and oral cavity (proportion = 58.1%, 95% CI 38.6–77.6%) and bilateral non-purulent conjunctival congestion (proportion = 56.0%, 95% CI 40.0–71.9%). Changes of peripheral extremities (proportion = 40.7%, 95% CI 12.9–68.5%) and acute non-purulent cervical lymphadenopathy (proportion = 28.5%, 95% CI 13.9–43.1%) were the least presenting features (Table 2). Children presented more often with gastrointestinal symptoms including abdominal pain, nausea, and diarrhea (proportion = 79.4%, 95% CI 68.1–90.7%) and shock (proportion = 68.1%, 95% CI 51.9–84.3%). Neurocognitive symptoms as headache, irritability, lethargy, or visual change were reported in 31.8% of patients (95% CI 21.9–41.8%), while the prevalence of respiratory symptoms as cough and dyspnea accounted for 29.6% (95% CI 19.6–39.6%) (Table 2). Obesity (proportion = 26.0%, 95% CI 7.1–44.9%) and asthma (proportion = 14.6%, 95% CI 6.9–22.2%) were two comorbid conditions reported in pediatric cases presented with Kawasaki-like features (Table 2). Abnormal Chest X-ray was observed in 45.5% (95% CI 24.9–66.0%), while ECG abnormalities was found in 55.3% of patients (95% CI 45.1–65.6%) (Table 2F). Apart of studies reporting ECG findings and asthma, there was evidence of considerable heterogeneity across studies. In addition, coronary artery aneurysm data (identified based on a z score of ≥ 2.5 in the left anterior descending or right coronary artery) were reported only in two studies by Whittaker et al. (13.8%) [34] and Capone et al. (15.1%) [39].

Laboratory data of COVID-19 patients

Pooled summary of complete blood picture showed leukocytosis (mean = 13.20 × 109/L, 95% CI: 10.82–15.59), lymphopenia (mean = 0.93 × 109/L, 95% CI 0.737–1.125), neutrophilia (mean = 12.67 × 109/L, 95% CI 8.56–16.76), and anemia (mean = 10.4 g/dL, 95% CI 9.55–11.39) in positively confirmed COVID-19 children.

Elevated liver enzyme levels (ALT: mean = 46.86 U/L, 95% CI 39.1–54.6 and AST: (mean = 52.89 U/L, 95% CI 45.9–59.8) and hypoalbuminemia (mean = 27.15 g/L, 95% CI 23.5–30.7) was reported across the studies. There was marked elevated cardiac markers: troponin (mean = 110.71 ng/L, 95% CI 59.08–162.3), NT-proBNP (mean = 5648.78 pg/mL, 95% CI 3823.17–7474.3), and LDH (mean = 637.21 U/L, 95% CI 358.7–915.7). Elevated inflammatory markers were observed: C-reactive protein (mean = 215.58 mg/L, 95% CI 192.50–238.67), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (mean = 64.64 mm/h, 95% CI 54.28–74.99), procalcitonin (mean = 19.24 ng/mL, 95% CI 8.67–29.80), ferritin (mean = 763.24 ng/mL, 95% CI 658.86–867.63), and interleukin-6 (mean = 189.67 pg/mL, 95% CI 145.48–233.87). There was an increased evidence for coagulopathy represented as a high blood concentration of fibrinogen (mean = 6.24 g/L, 95% CI 4.68–7.80) and D-dimer (mean = 3.79 μg/mL, 95% CI 2.57–5.02) (Table 2).

Pooled analysis of COVID-19 complications

Of the affected children and teenagers, 77.0% (95% CI 56.9–97.0%) developed hypotension, 68.1% (95% CI 51.9–84.3%) went into shock, and 41.1% (15.0–67.1%) had acute kidney injury. Intensive care was needed in 73.7% of cases (95% CI 60.3–87.1%), 13.2% (95% CI 0.5–82.1%) were intubated and 37.9% (95% CI 28.3–47.6%) required mechanical ventilation, with only one reported fatality case. Pediatric patients were discharged after a mean hospital stay of 6.77 days (95% CI 4.93–8.6) (Table 2).

Received medications

Intravenous immunoglobulins and steroids were given in 87.7% (95% CI 80.8–94.7%) and 56.9% (95% CI 33.6–80.2%) of the children. Anticoagulants were utilized in 67.0% (95% CI 47.6–86.3%) of pediatric patients. Anakinra (Anti-IL-1) was prescribed in only 9.4% (95% CI 4.6–14.2%) of cases (Table 2).

Discussion

Pediatric patients have largely been overlooked during the COVID-19 pandemic, as the largest cohort of morbidity and mortality has come in elderly adult populations [41]. More recently, the insidious connection between COVID-19 infections and a syndrome similar to Kawasaki disease has been investigated as healthcare professionals noticed outbreaks of the rare constellation of symptoms throughout the United States and the world [39]. The context of these reports is essential as officials weigh the risks of reopening schools with the pandemic ongoing, and physicians are treating pediatric patients with severe inflammatory responses. The association of Kawasaki-like disease to coronaviruses is still a continuous area of research, and the COVID-19 pandemic provides a unique opportunity to investigate the connection of coronavirus infection to a pediatric inflammatory response that mimics Kawasaki disease.

The COVID-19-associated multisystem inflammatory syndrome patients tended to be much older than typical Kawasaki disease patients. A large sample of Korean Kawasaki disease patients showed a mean age of just 2.54 years compared with 9.10 in this meta-analysis [42]. This finding is especially important because children with onset of Kawasaki disease aged nine or older are at a significantly higher risk of developing coronary artery aneurysms and left ventricular abnormalities; a feared outcome is up to 25% of untreated children [43]. Older age may be one of many factors in the multiple inflammatory syndrome that contributed to such high proportions of patients experiencing shock and hypotension, along with elevated troponin and BNP levels. Although the cardiac manifestations of Kawasaki disease typically resolve within two years, the long-term effects of an inflammatory response in Kawasaki disease are not fully known, with microvascular changes and intimal thickening proposed as possible sequelae [44].

Patients in this meta-analysis presented with many typical symptoms of Kawasaki disease and several atypical ones. A previous study on Kawasaki disease risk factors for developing coronary artery aneurysms showed that having more of the typical five symptoms is a protective factor. At the same time, atypical presentations are a risk factor [45]. Although the patients in our analysis who developed multisystem inflammatory syndrome in pediatrics met the typical criteria defined by the centers of disease control and prevention [22], nearly half of them had Kawasaki disease-like clinical features as polymorphous maculopapular exanthema, oral mucosal changes, and/or conjunctival injections, cervical lymphadenopathy, or peripheral edematous changes to extremities. Notably, some of these features are also seen in other severe disorders like toxic shock syndrome, which impact multiple systems and have been associated with other viruses. Unlike Kawasaki disease, cases presented with the specified syndrome were children and adolescents older than 5 years of age and had more frequent cardiovascular involvement [18].

In addition, atypical gastrointestinal and neurocognitive symptoms are frequent and may have contributed to delayed recognition of the children’s condition as an inflammatory disease similar to Kawasaki disease, thus delaying intravenous immunoglobulin administration. Abnormal electrocardiograms and chest X-rays are also common findings on admission for the multisystem inflammatory syndrome. The differences between this clinical picture and Kawasaki disease will likely lead to delays in treatment that could be detrimental to patients. It will be necessary for pediatric tertiary care centers to stay apprised of the evolving presentation of this inflammatory illness. A patient’s number of symptoms correlated with a lower risk of coronary artery aneurysms. A possible explanation for this is that more Kawasaki like symptoms led to earlier suspicion for inflammatory disease, causing there to be less delay in administering treatments like intravenous immunoglobulin. Another possibility is that dysfunctional immune systems are less likely to produce as many classic disease symptoms [45].

The massive inflammatory response to infection with COVID-19 is a significant point of focus for research, novel therapeutic developments, and vaccine research trials. Pediatric patients in this meta-analysis had markedly elevated inflammatory markers, including C-reactive protein and procalcitonin, previously associated with an increased risk of coronary artery aneurysms in Kawasaki disease [45]. About 69.6% of the patients in this meta-analysis tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibodies, a higher number than tested positive for the nasal swab polymerase chain reaction, supporting the etiopathology of this syndrome in that a COVID-19 infection weeks earlier could trigger the syndrome and hemodynamic shock.

Many of the laboratory findings in this pediatric population were consistent with findings in adult patients who developed severe respiratory disease from SARS-CoV-2. Elevated lactic acid dehydrogenase, D-dimer levels, procalcitonin levels, troponin I level, and lymphopenia have been demonstrated as markers of worse outcomes in adult COVID-19 patients [46]. IL-6 has been associated with the “cytokine storm”, or macrophage activation syndrome-like disease thought to be a factor in developing acute respiratory distress syndrome in adult patients [47]. IL-6 also plays a role in the pathogenesis and, more recently, targeted therapy of childhood inflammatory disorders like systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis [48]. Similarly, children who developed multisystem inflammatory syndrome in this meta-analysis had remarkably high IL-6 levels with a mean of 189.67 pg/mL, exhibiting the role of systemic inflammation. Further research could evaluate whether immunomodulatory therapies like tocilizumab (considering the potential acceleration of the coronary artery aneurysm formation reported previously) [49], in addition to intravenous immunoglobulin, could be useful for pediatric patients at risk of developing progressing to multisystem inflammatory syndrome.

One of the limitations of this meta-analysis was that the studies were conducted in the United States and Europe. East Asian countries, which historically have higher rates of Kawasaki disease, have pediatric populations that have had longer COVID-19 exposure times, and retrospective studies could be helpful to assess differences in prevalence and outcomes. This region is also known to have different phylogenetic SARS-CoV-2 genomes, which could influence the inflammatory response seen in multisystem inflammatory syndrome patients [50]. In addition, differences in infection rates, host factors, including racial differences, immunomodulators early treatment, or incomplete reporting, should be considered [22]. Second, in the absence of a comparison group and the presence of considerable heterogeneity across studies, caution is warranted in interpreting the current data.

Conclusions

The findings presented in the meta-analysis have important implications worldwide, as many countries still struggle with COVID-19, and hotspots put children at risk for infection. More research into the pathophysiology of multisystem inflammatory syndrome is needed to understand how it differs from Kawasaki disease. It could also begin to provide an idea of why some children experience shock and hypotension, while others have less acute complications. In addition, comparing relative rates of coronary artery aneurysms in multisystem inflammatory syndrome versus Kawasaki disease would help medical decision making. In addition, future meta-analyses that consider comparing Kawasaki disease with/without COVID-19 cases would be far more interesting to clarify the clinical differences between these overlapping entities.

Although multisystem inflammatory syndrome still appears to be a rare occurrence in COVID-19 positive children, it has become clear that this syndrome requires aggressive medical management with a multidisciplinary team and close, long-term follow-up. Recognizing the atypical presentation of the multisystem inflammatory syndrome, monitoring patients for cardiac and renal decompensation, and early interventions to treat the exaggerated immune response in these patients are critical to prevent further morbidity.

Author contributions

MHH, RME, EAT, JD, and MSF contributed to study design. MHH, RME, RM, and NS contributed to the systematic search, screening, and data abstraction. MHH, RME, and EAT contributed to statistical analysis. MHH, RME, MSF, and EAT contributed to data interpretation. MHH, RME, AK, ST, MSF, and EAT contributed to writing the first draft. All the authors revised and approved the manuscript.

Funding

There is no funding source.

Compliance with ethical statements

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Conflict of interest

No financial or nonfinancial benefits have been received or will be received from any party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Toraih EA, Elshazli RM, Hussein MH, Elgaml A, Amin M, El-Mowafy M, et al. Association of cardiac biomarkers and comorbidities with increased mortality, severity, and cardiac injury in COVID-19 patients: a meta-regression and decision tree analysis. J Med Virol. 2020;92:2473–2488. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Covid CDC, Bialek S, Gierke R, Hughes M, McNamara LA, Pilishvili T, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 in children—United States, February 12–April 2, 2020. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:422. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6914e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Docherty AB, Harrison EM, Green CA, Hardwick HE, Pius R, Norman L, et al. Features of 20 133 UK patients in hospital with covid-19 using the ISARIC WHO Clinical Characterisation Protocol: prospective observational cohort study. BMJ. 2020;369:m1985. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Viner RM, Whittaker E. Kawasaki-like disease: emerging complication during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 2020;395(10239):1741–1743. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31129-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bi Q, Wu Y, Mei S, Ye C, Zou X, Zhang Z, et al. Epidemiology and transmission of COVID-19 in 391 cases and 1286 of their close contacts in Shenzhen, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:911–919. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30287-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang J, Litvinova M, Liang Y, Wang Y, Wang W, Zhao S, et al. Changes in contact patterns shape the dynamics of the COVID-19 outbreak in China. Science. 2020;368:1481–1486. doi: 10.1126/science.abb8001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheung EW, Zachariah P, Gorelik M, Boneparth A, Kernie SG, Orange JS, et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome related to COVID-19 in Previously Healthy Children and Adolescents in New York City. JAMA. 2020;324:294–296. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.10374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chiu JS, Lahoud-Rahme M, Schaffer D, Cohen A, Samuels-Kalow M. Kawasaki disease features and myocarditis in a patient with COVID-19. Pediatr Cardiol. 2020;41:1526–1528. doi: 10.1007/s00246-020-02393-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kanegaye JT, Wilder MS, Molkara D, Frazer JR, Pancheri J, Tremoulet AH, et al. Recognition of a Kawasaki disease shock syndrome. Pediatrics. 2009;123:e783–e789. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gamez-Gonzalez LB, Moribe-Quintero I, Cisneros-Castolo M, Varela-Ortiz J, Muñoz-Ramírez M, Garrido-García M, et al. Kawasaki disease shock syndrome: unique and severe subtype of Kawasaki disease. Pediatr Int. 2018;60:781–790. doi: 10.1111/ped.13614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rowley AH, Shulman ST. Pathogenesis and management of Kawasaki disease. Expert Rev Antiinfect Ther. 2010;8:197–203. doi: 10.1586/eri.09.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holman RC, Belay ED, Christensen KY, Folkema AM, Steiner CA, Schonberger LB. Hospitalizations for Kawasaki syndrome among children in the United States, 1997–2007. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2010;29:483–488. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181cf8705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Castagnoli R, Votto M, Licari A, Brambilla I, Bruno R, Perlini S, et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection in children and adolescents: a systematic review. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174:882–889. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qiu H, Wu J, Hong L, Luo Y, Song Q, Chen D. Clinical and epidemiological features of 36 children with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Zhejiang, China: an observational cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:689–696. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30198-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Esper F, Shapiro ED, Weibel C, Ferguson D, Landry ML, Kahn JS. Association between a novel human coronavirus and Kawasaki disease. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:499–502. doi: 10.1086/428291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shirato K, Imada Y, Kawase M, Nakagaki K, Matsuyama S, Taguchi F. Possible involvement of infection with human coronavirus 229E, but not NL63, Kawasaki disease. J Med Virol. 2014;86:2146–2153. doi: 10.1002/jmv.23950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Verdoni L, Mazza A, Gervasoni A, Martelli L, Ruggeri M, Ciuffreda M, et al. An outbreak of severe Kawasaki-like disease at the Italian epicentre of the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic: an observational cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1771–1778. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31103-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feldstein LR, Rose EB, Horwitz SM, Collins JP, Newhams MM, Son MB, et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in US children and adolescents. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:334–346. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2021680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pilania RK, Jindal AK, Srikrishna VV, Samprathi M, Singhal M, Singh S. Hypotension in a Febrile child—beware of Kawasaki disease Shock Syndrome. JCR J Clin Rheumatol. 2020;26:e130-e1. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0000000000001002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Riphagen S, Gomez X, Gonzalez-Martinez C, Wilkinson N, Theocharis P. Hyperinflammatory shock in children during COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 2020;395:1607–1608. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31094-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McInnes MDF, Moher D, Thombs BD, McGrath TA, Bossuyt PM, Clifford T, et al. Preferred reporting items for a systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy studies: the PRISMA-DTA statement. JAMA. 2018;319:388–396. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.19163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Godfred-Cato S, Bryant B, Leung J, Oster ME, Conklin L, Abrams J, et al. COVID-19–associated multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children—United States, March–July 2020. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1074. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6932e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Behmadi M, Alizadeh B, Malek A. Comparison of clinical symptoms and cardiac lesions in children with typical and atypical Kawasaki disease. Med Sci. 2019;7:63. doi: 10.3390/medsci7040063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wallace BC, Dahabreh IJ, Trikalinos TA, Lau J, Trow P, Schmid CH. Closing the gap between methodologists and end-users: R as a computational back-end. J Stat Softw. 2012;49:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pierce CA. Comprehensive meta-analysis. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications Inc; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 26.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials revisited. Contemp Clin Trials. 2015;45:139–145. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2015.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Andreano A, Rebora P, Valsecchi MG. Measures of single arm outcome in meta-analyses of rare events in the presence of competing risks. Biom J. 2015;57:649–660. doi: 10.1002/bimj.201400119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin L, Chu H. Quantifying publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. 2018;74:785–794. doi: 10.1111/biom.12817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chiotos K, Bassiri H, Behrens EM, Blatz AM, Chang J, Diorio C, et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children during the COVID-19 pandemic: a case series. J Pediatr Infect Dis Soc. 2020;9:393–398. doi: 10.1093/jpids/piaa069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grimaud M, Starck J, Levy M, Marais C, Chareyre J, Khraiche D, et al. Acute myocarditis and multisystem inflammatory emerging disease following SARS-CoV-2 infection in critically ill children. Ann Intensive Care. 2020;10:1–5. doi: 10.1186/s13613-020-00690-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Toubiana J, Poirault C, Corsia A, Bajolle F, Fourgeaud J, Angoulvant F, et al. Kawasaki-like multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children during the covid-19 pandemic in Paris, France: prospective observational study. BMJ. 2020;369:m2094. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miller J, Cantor A, Zachariah P, Ahn D, Martinez M, Margolis KG. Gastrointestinal symptoms as a major presentation component of a novel multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children that is related to coronavirus disease 2019: a single center experience of 44 cases. Gastroenterology. 2020;159:1571–1574. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.05.079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Perez-Toledo M, Faustini SE, Jossi SE, Shields AM, Kanthimathinathan HK, Allen JD, et al. Serology confirms SARS-CoV-2 infection in PCR-negative children presenting with paediatric inflammatory multi-system syndrome. MedRxiv [Preprint], 2020.

- 34.Whittaker E, Bamford A, Kenny J, Kaforou M, Jones CE, Shah P, et al. Clinical characteristics of 58 children with a pediatric inflammatory multisystem syndrome temporally associated with SARS-CoV-2. JAMA. 2020;324:259–269. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.10369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blondiaux E, Parisot P, Redheuil A, Tzaroukian L, Levy Y, Sileo C, et al. Cardiac MRI of children with multisystem inflammatory syndrome (MIS-C) associated with COVID-19: case series. Radiology. 2020;297:E283–E288. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020202288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pouletty M, Borocco C, Ouldali N, Caseris M, Basmaci R, Lachaume N, et al. Paediatric multisystem inflammatory syndrome temporally associated with SARS-CoV-2 mimicking Kawasaki disease (Kawa-COVID-19): a multicentre cohort. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;79:999–1006. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-217960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ramcharan T, Nolan O, Lai CY, Prabhu N, Krishnamurthy R, Richter AG, et al. Paediatric inflammatory multisystem syndrome: temporally associated with SARS-CoV-2 (PIMS-TS): cardiac features, management and short-term outcomes at a UK Tertiary Paediatric Hospital. Pediatr Cardiol. 2020;41:1391–1401. doi: 10.1007/s00246-020-02391-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kaushik S, Aydin SI, Derespina KR, Bansal PB, Kowalsky S, Trachtman R, et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection (MIS-C): a multi-institutional study from New York City. J Pediatr. 2020;224:24–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.06.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Capone CA, Subramony A, Sweberg T, Schneider J, Shah S, Rubin L, et al. Characteristics, cardiac involvement, and outcomes of multisystem inflammatory syndrome of childhood associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection. J Pediatr. 2020;224:141–145. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.06.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moisan-Delaunay A, Mesplees B, Auriau J, Kariyawasam D, Orliaguet G, Bader-Meunier B, et al. Prior infection by seasonal coronaviruses does not prevent SARS-CoV-2 infection and associated Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in children. medRxiv. 2020.

- 41.Xia W, Shao J, Guo Y, Peng X, Li Z, Hu D. Clinical and CT features in pediatric patients with COVID-19 infection: different points from adults. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2020;55:1169–1174. doi: 10.1002/ppul.24718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Park YW, Han JW, Park IS, Kim CH, Yun YS, Cha SH, et al. Epidemiologic picture of Kawasaki disease in Korea, 2000–2002. Pediatr Int. 2005;47:382–387. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200x.2005.02079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Song D, Yeo Y, Ha K, Jang G, Lee J, Lee K, et al. Risk factors for Kawasaki disease-associated coronary abnormalities differ depending on age. Eur J Pediatr. 2009;168:1315. doi: 10.1007/s00431-009-0925-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.de La Harpe M, Di Bernardo S, Hofer M, Sekarski N. Thirty years of Kawasaki disease: a single-center study at the University hospital of Lausanne. Front Pediatr. 2019;7:11. doi: 10.3389/fped.2019.00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yan F, Pan B, Sun H, Tian J, Li M. Risk factors of coronary artery abnormality in children with Kawasaki disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Pediatr. 2019;7:374. doi: 10.3389/fped.2019.00374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, Fan G, Liu Y, Liu Z, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McGonagle D, Sharif K, O'Regan A, Bridgewood C. The role of cytokines including interleukin-6 in COVID-19 induced pneumonia and macrophage activation syndrome-like disease. Autoimmunity Rev. 2020;19:102537. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2020.102537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.De Benedetti F, Brunner HI, Ruperto N, Kenwright A, Wright S, Calvo I, et al. Randomized trial of tocilizumab in systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:2385–2395. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1112802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nozawa T, Imagawa T, Ito S. Coronary-artery aneurysm in tocilizumab-treated children with Kawasaki’s Disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1894–1896. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1709609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Forster P, Forster L, Renfrew C, Forster M. Phylogenetic network analysis of SARS-CoV-2 genomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2020;117:9241–9243. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2004999117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]