Abstract

Current estimates of flood hazards are often based on the assumption that topography is static. When tectonic and/or anthropogenic processes change the land surface elevation, the spatial patterns of floods might also change. Here, we employ the hydrological and hydraulic modeling to simulate floods in the Kujukuri Plain, Japan, in the years 2004 and 2013, when two severe floods occurred. In between the two floods, land surface elevations were changed by the 2011 Tohoku-Oki earthquake. The effects of land surface elevation changes on inundation areas were quantified by changing input topographies. Our results showed that, without taking into account land surface elevation changes, around 10% of inundation areas were underestimated at the time of flood events in the year 2013. The spatial distribution of inundation locations varied with local topographical features, for example, the areas with backmarsh and valley fill deposits were sensitive to the extent of inundation by land surface elevation changes. The sub-watershed near the coastal shoreline having below-zero meter elevation areas showed that the earthquake-induced land surface elevation changes exacerbated an additional 22% inundation area. This study suggests that the inundation areas will increase in catchments suffering severe settlements, which highlights the necessity of taking into account the spatio-temporal changes of land surface elevations on the assessment of flood hazards.

Subject terms: Hydrology, Natural hazards

Introduction

Floods are one of the most common disasters, causing devastating catastrophes worldwide1–3. The intensity and severity of floods affect human society and its economic development4–7. Due to climate change, the floods are anticipated to increase in future8–11. Globally, 42% of the land shows an increase in the frequency of flood occurrence under the Representative Concentration Pathways (RCP) 8.5 (Ref.12–14). The local floods would even cause potentially negative repercussions with the propagation to the supply network and trade1,15,16. Therefore, understanding the physical and spatial characteristics of floods in a catchment scale would be of great benefit for developing mitigation measures and adaptation policies to reduce the negative influences.

Having fine resolution digital elevation models (DEM) is advantageous to investigate catchment scale flood events17–20. The flood model, which includes full integration of hydrological and hydraulic cycles, was suggested in constructing flood hazard maps21. The model can take into account the hydrodynamic features in the atmosphere, surface, and subsurface, which enables a realistic representation of the flood assessment22–25. Urbanization-induced land use and land cover change26, sea level rise27, and tidal effect28 can also be considered through the flood model. Land surface elevations are crucial in both overland and channel routing during heavy rainfalls, which can be adequately evaluated by the hydrological and hydraulic model.

Both natural and human activities can lead to land surface elevation changes, such as earthquake-induced tectonic movement29,30, sediment compaction31–33, coal mining34, sand mining35, and groundwater abstraction36,37. These temporal geomorphological processes were frequently occurred in coastal cities and caused significant impacts on flood hazards38–41.

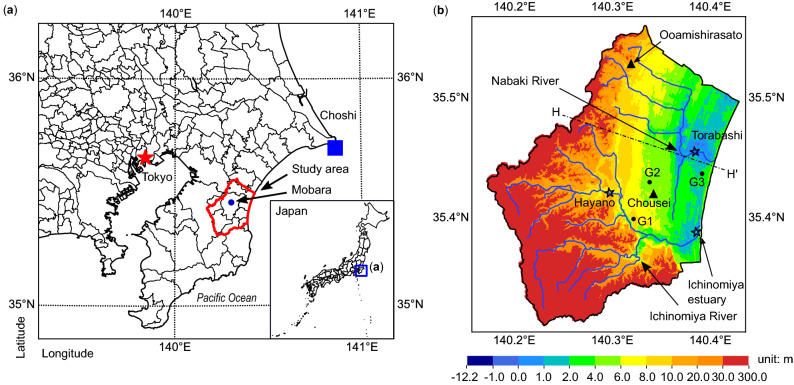

In this study, we employed the hydrological and hydraulic model to quantitatively evaluate the influence of land surface elevation changes on flood hazards in the Kujukuri Plain, Chiba Prefecture, Japan (Fig. 1a). The 2011 magnitude-9 Tohoku-Oki earthquake caused more than 0.1 m of subsidence in this area29. Specifically, the observed data showed around 0.11 m subsidence in the Chosei station, and 0.13 m in the Oamishirasato station. Figure 1b shows the topographic map in the year 2013. Two river systems—Nabaki River, with a catchment area of around 116.5 km2, and Ichinomiya River, with that of around 203.0 km2, flow through the study area. To examine the impacts of the 2011 earthquake-induced land surface elevation changes on the floods, the years 2004 and 2013 were chosen as the simulation periods because the typhoons Tokage and Wipha, respectively, hit the Kujukuri Plain42,43.

Figure 1.

Location and topographic map of the study area. (a) The location of research site. Choshi is a tidal station, and the measured sea levels at Choshi were used as the coastal boundary conditions in the model. (b) The topographic map in the year 2013. Two river systems: Nabaki River and Ichinomiya River, flow through the study area. The Chosei station showed around 0.11 m subsidence, and the Oamishirasato station around 0.13 m subsidence due to the 2011 Tohoku earthquake29. Torabashi, Hayano and Ichinomiya Estuary are the river gauging stations, and the measured river water levels were used to calibrate model parameters (Fig. S3). G1, G2 and G3 are groundwater observation wells, and the measured groundwater levels were also used to calibrate the model parameters (Fig. S4). The modeled geological cross-section along the line H–H’ is shown in Fig. S2(c). (Figure generated using Matplotlib v. 2.2.3, http://www.matplotlib.org. Local basemaps from Geospatial Information Authority of Japan, Global Map Japan v. 2.2, http://www.gsi.go.jp, accessed 29 Jul 2020).

The hydrological and hydraulic model was applied in the research site by employing the coupled MIKE SHE44 and MIKE HYDRO River45 software to evaluate the inundation areas (see “Methods” section for more details). The simulated scenarios are listed in Table 1. The sensitive parameters, e.g., Manning’s coefficients and hydraulic conductivities, were calibrated by comparing the simulation results with the observations during the years 2018 and 2019 (Scenario Cal in Table 1). The flood events in the years 2004 and 2013 were simulated as cases 04A and 13A (the numbers represent the year of input topography, and the letter “A” represents the actual case), and compared with the surveyed inundation area. Comparisons between simulated and observed river water levels, groundwater levels, and the extents of floods, revealed that the developed flood model can reasonably well reproduce the hydrological processes in the area. Subsequently, the input topographies of the cases 04A, 13A, were changed to the topographies of 2013 (13P, “P” represents the parametric case) and 2004 (04P), respectively, while keeping the others unchanged, to quantify the effects of land surface elevation changes on flood features. Our results indicated that, without considering the land surface elevation change, the inundation areas were underestimated at around 10%.

Table 1.

The simulated scenarios for calibration, validation, and quantification of the hydrological and hydraulic model. Cal means the simulation for calibration. The numbers in the scenarios column represent the year of input topography, and the letter “A” is for the actual simulations and “P” is for the parametric simulations.

| Scenarios | Purpose | Topography | Simulation period | Examination duration | Typhoon | TP* | MP** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cal*** | Calibration | 2013 | 2018.01–2019.10 | 2018.12 and 2019.04–2019.07 | No | 604 | 17.5 |

| 04A | Actual | 2004 | 2004.01–2004.12 | 2004.10.08–2004.10.09 | Tokage | 209 | 49.0 |

| 13A | Actual | 2013 | 2013.01–2013.12 | 2013.10.15–2013.10.16 | Wipha | 272 | 42.0 |

| 04P | Parametric | 2004 | 2013.01–2013.12 | 2013.10.15–2013.10.16 | Wipha | 272 | 42.0 |

| 13P | Parametric | 2013 | 2004.01–2004.12 | 2004.10.08–2004.10.09 | Tokage | 209 | 49.0 |

*Total precipitation during the examination period (mm).

**Hourly maximum precipitation during the examination period (mm).

***There was no typhoon during the examination duration.

Results

Comparison with observations

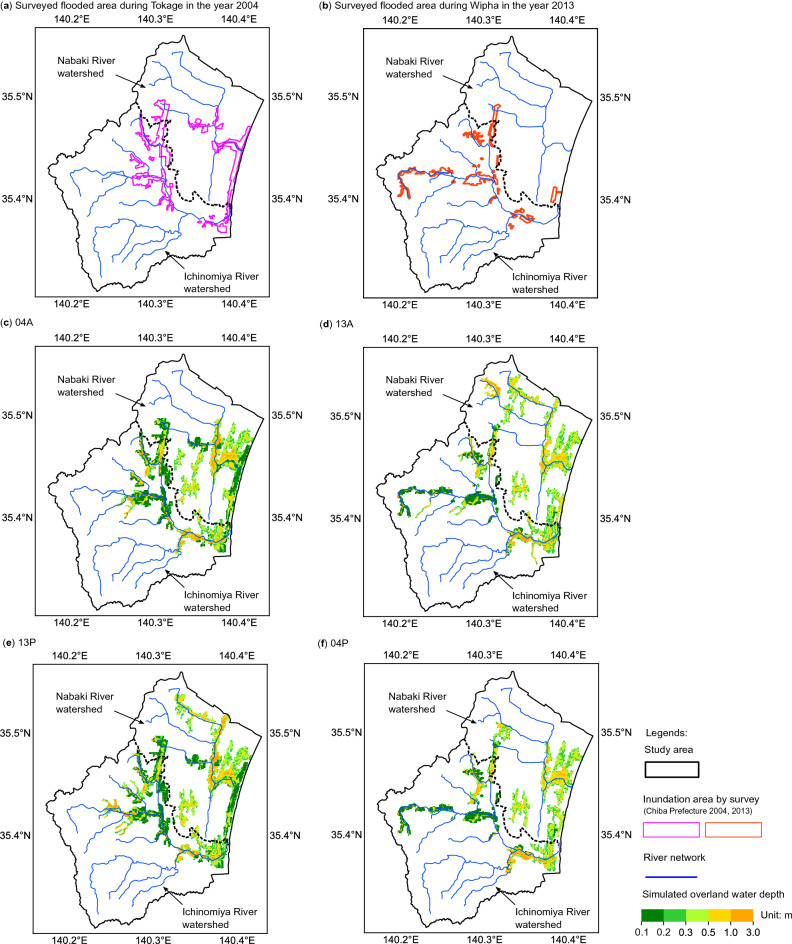

The simulated inundation areas of the four scenarios (Table 1) are presented in Fig. 2, together with the observations. The regions surrounded by magenta lines in Fig. 2a were the reported flooded areas by Chiba Prefecture at the time of flood event in the year 2004 (Ref.42), and those surrounded by orange lines in Fig. 2b are those at the flood event in the year 2013 (Ref.43). The field investigation in the year 2013 was mainly conducted in the Ichinomiya River watershed and not thoroughly in the Nabaki River watershed; therefore, the following quantitative discussions were only focused on the Ichinomiya River watershed. Table 2 shows the surveyed and calculated extents of the inundation areas. A comparison of the field investigated (Fig. 2a,b) and calculated (Fig. 2c,d) inundation areas indicated that the simulation could reproduce around 98% of the surveyed flooded area for both cases. For the simulated inundation areas in the Ichinomiya River watershed, approximately 80% of the simulated flooded areas were reported to be flooded in both the years 2004 and 2013.

Figure 2.

Observed and simulated inundation areas in both Nabaki and Ichinomiya River watersheds for four scenarios. The regions surrounded by magenta lines in (a) were the reported flooded areas in the year 2004 (Ref.42), and those surrounded by the orange lines in (b) were the surveyed flooded areas mainly in the Ichinomiya River watershed at the flood event in the year 2013 (Ref.43). (c) 04A and (d) 13A were employed to compare the calculated flooded areas with the observed ones. (e) 13P and (f) 04P were conducted to quantify the influence of land surface elevation changes on the spatial features of the inundation areas. The boundary of river watersheds is based on Dutta et al.18. (Figure generated using Matplotlib v. 2.2.3, http://www.matplotlib.org).

Table 2.

Comparison of observed and simulated flood extents.

The numerical results suggested a potential overestimation of the extents in the inundation areas, which might be resulted from the spatial resolution of overland flow modeling. The resolution of original DEM is 1 m with the accuracy in elevation to be 0.03 m. The river cross-sectional profiles were obtained from official report, 1 m resolution DEM, and site investigation, thus, the levees and embankments were accounted for in the channel flow simulation by MIKE HYDRO River. However, the overland flow was simulated in the 50 m size cells by MIKE SHE, upscaled from the 1 m resolution DEM, due to the compromise between the computational power and accuracy. Even though this caused an enlargement of depression areas, which then led to an overestimation of the inundation areas compared to the observed flood extents, the fact that the numerical modeling can reproduce most of the reported inundation areas indicated that the current model could yield reasonable quantification of land surface elevation changes on the inundation impacts.

Quantification on inundation areas

When comparing the inundation areas of 04A with 13P (Fig. 2c,e), and 13A with 04P (Fig. 2d,f), for the same examination durations but different topographies, the inundation maps demonstrated that the changes of land surface elevations would alter the total inundation areas and spatial patterns of flood hazards.

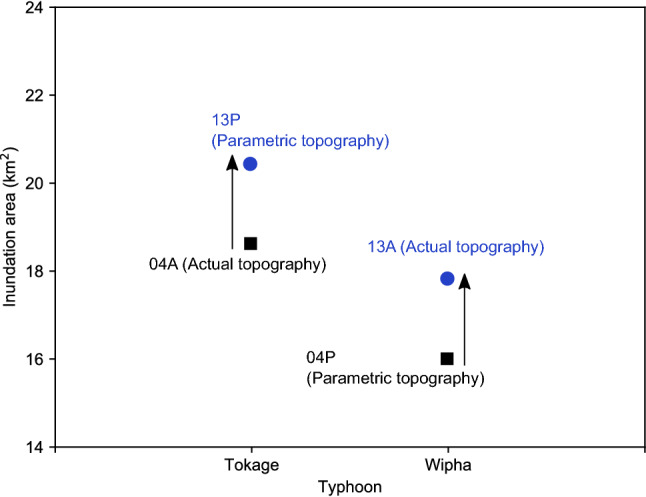

A summary of the total inundation areas is shown in Fig. 3. For the typhoon Tokage, the calculated result with the topography of the year 2004 showed around 18.6 km2 of flooded area in the Ichinomiya River watershed, whereas, that with the topography of the year 2013 around 20.4 km2, indicating additional 10% were calculated to be possibly inundated due to land surface elevation change. A similar increase of inundation areas with typhoon Wipha was also noted in Fig. 3, which illustrated that the land surface elevation changes could exaggerate the inundation areas in the study site during the examination period.

Figure 3.

Quantification of the inundation areas considering the effects of land surface elevation changes in the Ichinomiya River watershed. 04A and 04P are the cases with the topographies before the earthquake, while 13P and 13A are those after the earthquake, which represents the results considering the influence of earthquake-induced land surface elevations.

Spatial distribution of inundation areas

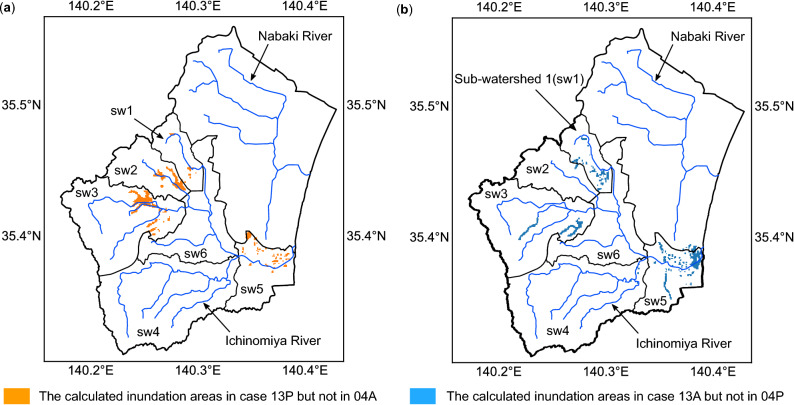

The difference of the calculated flooded areas between 04A and 13P, i.e., the area flooded by 13P but not by 04A, is shown in Fig. 4a. A similar comparison between 13A and 04P was shown in Fig. 4b. For both flood events in 2004 and 2013, the sub-watersheds 4 and 6 showed small inundation areas, and the majority of inundation locations with different input topographies were almost the same. In the flood plain area, at the time of flood event in 2004, sub-watersheds 1, 2, 3, and 5 showed differences in the calculated flood patterns. Sub-watersheds 1, 3, and 5 showed differences at the 2013 flood event.

Figure 4.

Comparison of the simulated inundation areas at the time of flood events in the year 2013 and 2004, respectively. (a) The difference of the calculated flooded areas between 04A and 13P, i.e., the area flooded by 13P but not by 04A. (b) The difference of the calculated flooded areas between 13A and 04P, i.e., the area flooded by 13A but not by 04P. (Figure generated using Matplotlib v. 2.2.3, http://www.matplotlib.org).

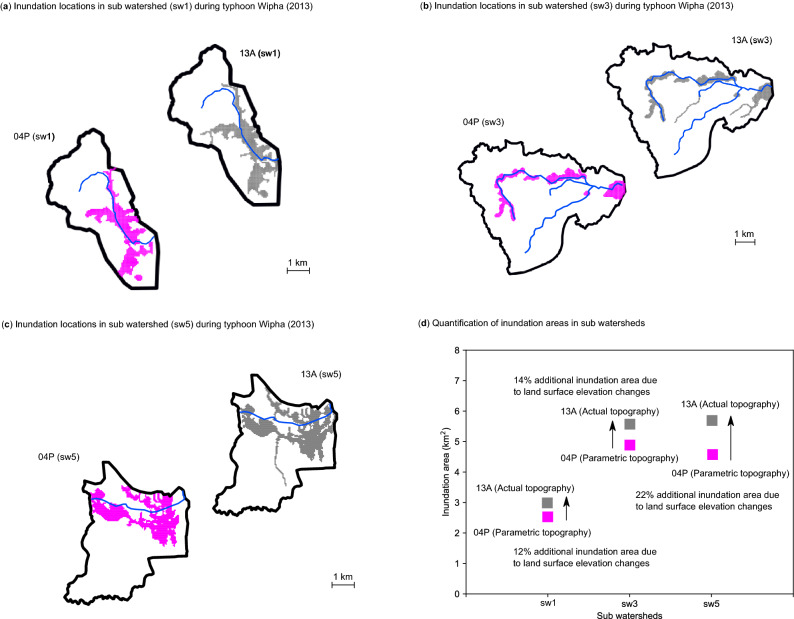

To quantify the spatial distribution of flood hazard affected by earthquake-induced surface elevation change, the details of inundation locations in sub-watersheds 1, 3, and 5 at the 2013 flood event in cases 13A and 04P are presented in Fig. 5. The simulated inundation areas of cases 13A and 04P in subwatersheds 1, 3, and 5 are summarized in Table 3. Regarding sub-watershed 1, an additional 12% were calculated to be possibly flooded by the land surface elevation changes during the typhoon Wipha. In sub-watershed 3, around 14% of inundation areas would be underestimated if the topography in the year 2004 was applied for the simulation. The sub-watershed 5 showed that more than 4.6 km2 of the land was suffered from flooding for both 13A and 04P cases. An additional 22% of the lands were calculated to be flooded by the land surface elevation changes.

Figure 5.

Detailed examination of the inundation areas in sub-watersheds during typhoon Wipha in 2013. (a) Inundation locations in sub-watershed 1. (b) Inundation locations in sub-watershed 3. (c) Inundation locations in sub-watershed 5. (d) Quantification of inundation areas in the sub-watersheds (Figure generated using Matplotlib v. 2.2.3, http://www.matplotlib.org).

Table 3.

Summary of the calculated inundation areas during 2013 typhoon Wipha in sub-watersheds 1, 3, and 5.

| Scenarios | Simulated inundation areas in sub-watershed (km2) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| sw1 | sw3 | sw5 | |

| 13A | 2.9 | 5.6 | 5.6 |

| 04P | 2.6 | 4.9 | 4.6 |

Based on the 1 m resolution DEMs obtained by the Light Detection and Ranging (Lidar) and used in this study, we obtained the subsidence map in between the years 2004 and 2013 in the study area. The whole area showed subsidence due to the 2011 Tohoku-Oki earthquake. Since the results and discussions were mainly focused on the Ichinomiya River watershed, the subsidence of the Ichinomiya River watershed was presented in Fig. S1(a). Figure S1(b) showed the difference of the calculated flooded areas between 13A and 04P, i.e., the area flooded by 13A but not by 04P. The difference of the simulated inundation areas by hydrological and hydraulic model (Fig. S1(b)) noted that the Ichinomiya River watershed would not be totally inundated although the whole area showed subsidence (Fig. S1(a)). More specifically, the inundation areas might not be exacerbated in some locations where severe subsidence was presented, suggesting that the locations where earthquake caused surface elevation change would not be always correlated with the locations where additional inundation was occurred.

Discussion

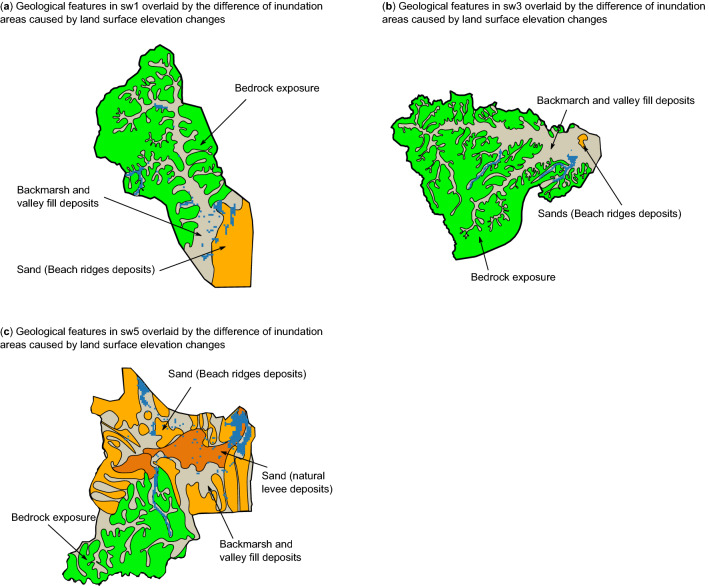

Our results showed that the surface elevation changes would affect the total inundation areas and the spatial patterns of floods in the coastal basin at the time of floods. Because the characteristics of geology were considered to affect the extent of the flood hazards, the simplified geologic map of sub-watersheds 1, 3, and 5 (Refs.46,47), overlaid by the difference of inundation areas, are presented in Fig. 6. The additional inundation areas calculated to be accounted for by land surface elevation changes in sub-watersheds 1 (Fig. 6a) and 3 (Fig. 6b) indicated that areas containing backmarsh and valley fill deposits and enclosed by terraces or beach ridges were sensitive to floods by elevation changes. For example, in sub-watershed 3, the majority of the difference of inundation areas was found in the valley areas (Fig. 6b). The valleys in sub-watersheds 1, 2, and 3 only have small outlets for the discharge of river water flow, which possibly affects the inundation features during heavy rainfall periods. This influence might be exaggerated by the surface elevation changes, resulting in some additional inundation areas in sub-watersheds 1 and 3 at the flood event in the year 2013. The surface elevations in sub-watershed 5 (Fig. 6c) were very low, and some areas were even below zero meters, which makes it quite vulnerable to floods. The simulation results showed that the elevation changes would exacerbate the inundation areas in sub-watershed 5 by 22% in the 2013 flood events. Our study demonstrated that the spatial impacts of land surface elevation changes on the inundation areas vary with locations, which can be impacted by the geological characteristics, and to obtain a comprehensive picture of the flood hazard map, the hydrological and hydraulic flood modeling can be useful to provide more detailed information.

Figure 6.

Simplified geologic map of the sub-watersheds (a) sw1, (b) sw3, and (c) sw5, overlaid by the difference of inundation areas during typhoon Wipha in the year 2013. (Figure generated using Matplotlib v. 2.2.3, http://www.matplotlib.org. Local geological maps from Geological Survey of Japan, http://www.gsj.jp, assessed 29 Jul 2020).

Comparison of inundation areas in between the years 2004 and 2013 (04A, 13A in Fig. S2(a) and (b)) revealed that the inundation patterns were not always constant and would be affected by the precipitation patterns, which were reported to be an important factor controlling the flood hazards22,48. The spatial distributions of precipitation during the typhoons Tokage and Wipha, respectively, were obtained from the composite data of radar and Automated Meteorological Data Acquisition System (AMeDAS)49,50 (Fig. S2(c) and (d)). The spatial resolution of the precipitation data in the year 2004 was 2.5 km mesh, and that in the year 2013 was 1.0 km mesh, respectively. To compare these two cases, precipitations of the years 2004 and 2013 were remapped to the same resolution with 0.05 km using a simple nearest-neighbor remapping algorithm. Observation of the precipitation at the time of the 2013 flood event (Fig. S2(d)) revealed that the sub-watershed 3 received a large amount of rainfall, which might have corresponded to the flood hazards along the river in sw3 (Fig. S2(b)). During the typhoon Tokage in 2004, the intensive rainfall in sub-watershed 3 was not recorded (Fig. S2(c)), thus, the inundation was not observed (Fig. S2(a)). Interestingly, the sub-watershed 5 received less rainfall during the typhoon Wipha (2013) than during the typhoon Tokage (2004). However, the confluence zones suffered severer flood hazard in the 2013 flood event (Fig. S2(b)) than that in the 2004 flood event (Fig. S2(a)), as indicated in blue square boxes. This might be responsible for the river flow features, i.e., sub-watershed 4 is situated in the upstream of the Ichinomiya River which received a large amount of rainfall in 2013 and flowed to the downstream, and it resulted in severe flood hazards in the confluence zones located in the intersection of sw4, sw5, and sw6 (Fig. S2(a) and (b)).

The inundation areas were expanded due to land surface elevation changes in the study site during the examination period. The framework presented here to account for the land surface elevation changes on flood hazards is transferable to other cities and can be used to assess the flood risks and inform policy decisions affecting environmental activities. New approaches and models are still needed for better understanding and representation of the dynamic features of floods51,52. It was reported that employing the new elevation data could triple estimate the coastal flood vulnerability due to sea level rise39, and here we presented that earthquake-induced land surface elevation changes exacerbate the inundation areas due to heavy rainfall. The results of this study suggested that for large-scale flood hazard assessment, the spatio-temporal changes of elevations are necessary to be taken into account in preparing the model parameters. The topography considering the spatio-temporal changes within the designated period should be used as the input DEM to assess the flood hazard. The study site, the Kujukuri Plain, has also been suffering from continuous land surface elevation changes, i.e., around 0.01 m per year subsidence at maximum, possibly due to groundwater exploitation37. The next step would tackle the effect of groundwater abstraction-induced land subsidence on the changes in the possible flood patterns and the assessment of future floods.

Methods

Research flow

Both earthquake and flood are natural hazards which would cause devastating catastrophes. Land surface elevation changes caused by earthquake has been reported in some catchments29,30. In this study, we aim to quantify the flood hazard impacts of earthquake-induced surface elevation change. The focus of this research was not to discuss the effects of uncertain topography on the flood hazard53–56, but to quantify the inundation areas in the catchments where certain earthquake-induced surface elevation change was observed. To reach this target, the hydrological and hydraulic model was employed to map the flood inundation areas57. The calibration, validation against measured data, and uncertainty analysis against the most affecting factors58,59, were conducted to ensure that the model was appropriate to evaluate the flood hazard. Our study presented an approach to link one hazard, earthquake-induced surface elevation change, with another, flood, and demonstrated that the spatio-temporal changes of topography was necessary to be considered in flood model.

Model principle

We coupled MIKE SHE44 and MIKE HYDRO River45 to evaluate the inundation impacts of land surface elevation changes in the Kujukuri Plain. Following processes were included in the model: the spatially distributed precipitation, evaporation and transpiration; 1D Saint Venant’s equation for the river channel flow; 2D shallow-water equation for the overland flow based on the kinematic routing; 1D Richards’ equation for the unsaturated zone; 3D groundwater flow. The model has been widely applied for both academic types of research and engineering management, focusing on the water management60, climate effects on hydrology61, water quality62 and eco-hydrology63 etc.

Model development

The total area of the model domain is 370.5 km2 with a spatial cell size of 50 × 50 m in MIKE SHE. The chosen resolution produced 148,187 cells in horizontal plane within the model domain. The thickness of each cell is 0.1 m for the simulation of subsurface flow.

The river network was digitized in the MIKE HYDRO River from the raster data. The river cross-sectional profiles were modeled based on the official reports64, 1 m resolution DEM, and site investigation, which suggested that the river levees and embankments were considered in the hydrological and hydraulic model. The high resolution DEMs were measured by Lidar with targeting vertical error of 0.05 m in our case. The leveling data in the study area were also obtained, and were compared with the Lidar data. The standard deviation of the Lidar data to the leveling data was 0.03 m, which suggested that the Lidar data showed a smaller vertical error than the targeting one. Figure S3 presented the histogram of the land surface elevation changes of the input data obtained from the 1 m resolution Lidar DEMs of the years 2004 and 2013 in the Ichinomiya River watershed. The downstream boundaries of the rivers were set to follow the sea levels observed at the Choshi station. Manning’s channel roughness coefficient was calibrated and listed in Table S1.

Due to the limitation of computational power, for the simulations of overland flow and subsurface flow in MIKE SHE, the input topography was remapped to 50 m resolution by inverse distance weighting through 1 m resolution DEM.

The land use land cover data were obtained from Chen et al.36. They constructed the land use land cover data from the Landsat-5 TM image, which was divided into eight classes, i.e., building estate, cropland, forest, grassland, paddy field, sands, urban, and water (Fig. S4(a)). The mean reproduction through the comparison between the band classified results and aerial photography was around 86% for each class36. The leaf area index (LAI) and root zone depth were obtained through the Ref.17, and presented in Table S1.

The subsurface formation was divided into three layers, i.e., 2-m shallow soil layer, the Holocene unconsolidated sand unit, and low-permeable Plio-Pleistocene Kazusa Group in descending order65, which was illustrated in Fig. S4(b). The hydraulic conductivities were treated as calibration parameters, and were shown in Table S1. The boundary conditions of saturated groundwater flow at the coast were assigned as hydrostatic pressure equal to seal level, and other boundaries were assigned as no flow.

The distribution of surface soil profile was obtained from the Chiba Prefecture official reports (Refs.46,47), with the spatial resolution of 50 m. Seven categories of soils were applied to this study area36, i.e., gley soil, immature soil, peat, gley lowland soil, brown lowland soil, brown forest soil, and andosols soil (Fig. S4(c)). The parameters for calculating unsaturated flow were obtained from the previous research17, and were listed in Table S1.

Composite precipitation data of Radar and Automated Meteorological Data Acquisition System (AMeDAS)49,50 were the data source for the spatially distributed precipitation. The spatial resolution of the precipitation data in the year 2004 was 2.5 km, and that in the year 2013 was 1.0 km. A simple nearest-neighbor remapping algorithm was used to allow the comparison in the same resolution of 0.05 km. The accuracy of the Radar/Raingauge-Analyzed precipitation was 96% (Refs.49,50). Actual evapotranspiration was calculated from the potential evaporation and soil moisture in the root zone by Kristensen and Jensen method66.

Parametric study

After developing the model, the hydrological process was calibrated through the comparison of simulated and observed river water levels (Fig. S5); and the groundwater levels (Figs. S6 and S7), by bootstrapping67. The detailed comparison of simulated and observed river water levels at the Torabashi, Hayano and Ichinomiya Estuary stations (Fig. S5(b), (d), and (f)) showed good agreements, suggesting that the model and parameter settings were reasonable to reproduce the hydrodynamic processes. The calibration ranges of the parameters within 3-standard-deviations from the observations are listed in Table S1.

To ensure the appropriateness of the parameters used, and to examine the characteristics of floods, the typhoon Tokage which attacked the study area from 8 to 9 Oct 2004, and the typhoon Wipha from 15 to 16 Oct 2013, were selected to further validate the models (scenarios 04A and 13A). The good reproducibility of the flooded areas (see “Inundation map projection” section, Fig. 7) by comparing the simulated results with the actual flooded areas (Fig. 2; Table 2) was achieved, and the parameters were considered to be appropriate in this study. In order to investigate the necessity of considering the earthquake-induced elevation changes in the hydrological and hydraulic modeling, the input topographies and the patterns of precipitations were interchanged. Accordingly, the inundation areas and spatial distribution of flooded locations can be quantified and discussed. Although the simulation of flood in 2004 using the topography of 2013 (13P) would not contribute to the practical implications, two simulations considering the change of surface elevation could increase the persuasiveness of our results.

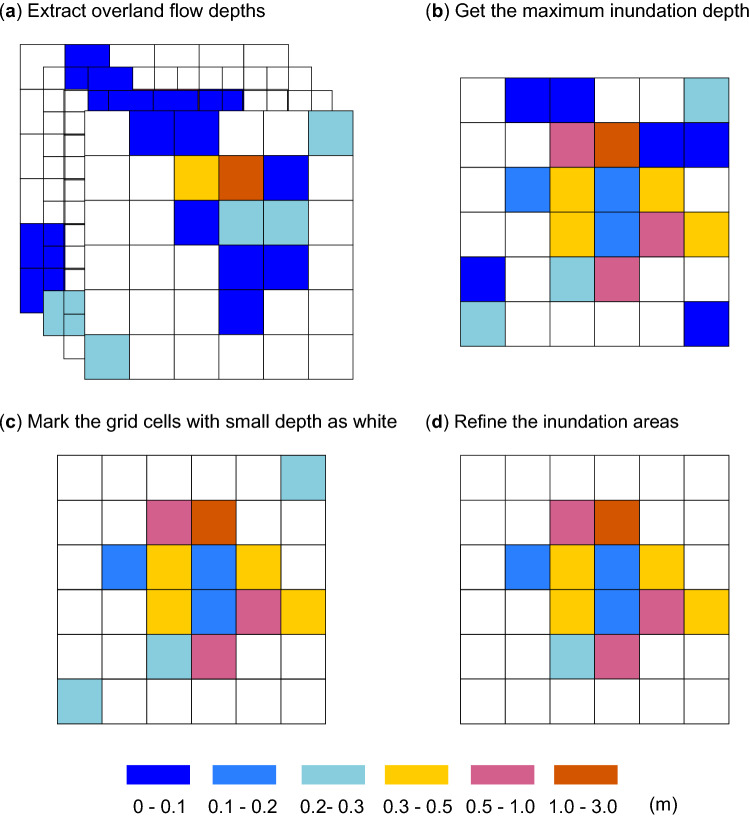

Figure 7.

Method of obtaining the inundation areas from the calculated results. (a) Collect the calculated overland flow depths with a one-hour interval during the examination periods. (b) Compare and obtain the maximum inundation depth in each cell. (c) Mark the cells with the small inundation depth (0.1 m) as white. (d) Refine the inundation areas to ignore the areas where the number of connected cells is smaller than 10.

Inundation map projection

Figure 7 demonstrates the approaches of obtaining inundation area maps in this study. The computed depths of overland flow during the examination periods were collected first with a one-hour interval during the examination periods. Through the comparison of water depths at the same locations, the maximum inundation depth map was obtained22. Then, the grid cells with very small inundation depth were marked as white (0.1 m in this study) based on the assumption that the very small water depth might generally not cause disasters12,28. Finally, the inundation map was refined by ignoring the regions where the connected number of grids are smaller than 10 in this study, which might represent the small rivers and lakes, and was hard to be surveyed in the field.

Parameter sensitivity

Most of the parameters in the developed dynamic flood model were derived from the related previous studies17,36,65, while the Manning’s roughness coefficient of rivers were empirically determined19. To answer the question if a small change in the Manning’s roughness coefficient of rivers makes large enough change in flood extent without the need to account for the modified topography, the sensitivity of the flood model to Manning’s channel roughness coefficient was studied by keeping all but the Manning’s channel roughness coefficient fixed in the scenarios 04A and 13P, respectively. According to Arcement and Schneider68, the Manning’s channel roughness coefficients were estimated to be varied from 0.017 to 0.025 for the channels with fine sands, therefore, the cases that changed the Manning’s channel roughness coefficient by -20% (n = 0.016) and + 20% (n = 0.024) were conducted, and were named M-20 and M + 20, respectively. The obtained flood extents were then compared with the reference models (04A and 13P). The calculated inundation areas in the Ichinomiya River watershed were illustrated in Fig. S8. The flood patterns were rarely altered by the change of Manning’s channel roughness coefficient within the range of the changes in this study. Figure S9 quantified the sensitivity of Manning’s channel roughness coefficient to the inundation areas. Results revealed that the simulated inundation area became larger (smaller) when the Manning’s channel roughness coefficient was larger (smaller). Twenty percent change of Manning’s channel roughness coefficient caused around 2% change of inundation areas. This is because flooding from river channels happens more easily when the roughness coefficient is larger19. According to the 1D Saint Venant’s equation, the river flow velocity becomes slower with larger roughness coefficient, so that water tends to be inundated to the surrounding floodplains rather than being discharged to downstream side.

For the same Manning’s channel roughness coefficients, the simulated inundation areas with the input topography of the year 2013 (simulations based on 13P) were always larger than those with input topography of the year 2004 (simulations based on 04A). The change of topography caused around 10% change of the simulated inundation areas.

Besides the Manning’s channel roughness coefficient, the input precipitation was suggested to be another affecting source of uncertainty according to global sensitivity analysis in flood inundation model57,59. Japan Meteorological Agency50 reported that the precipitation obtained from AMeDAS showed an error of 4%. Thus, the sensitivity analysis was conducted by changing the amount of distributed precipitation with − 4% and + 4% in each grid cell, and was named P − 4 and P + 4, respectively. The inundation areas with the sensitivity of input precipitation were compared with reference models (04P and 13A), as shown in Fig. S10. The results indicated that the calculated inundation areas were not strongly affected by the change of ± 4% input precipitation. However, the change of topography resulted in around 10% change of the simulated inundation areas. This suggested that the exacerbation of flood extent due to dynamic topography was significant enough to be distinguishable from the changes in the flood extents caused by the uncertainty of Manning’s channel roughness coefficient and the input precipitation.

Limitation

It should be noted that our calculated inundation area is an estimation based on the current state of precision, and the quantities in the results should be interpreted with caution because of several methodological challenges. The DEM, precipitation, and land use land cover patterns have uncertainty in the representation of flood events because of their spatial resolutions. The parameters of the model could also have uncertainty in computing the hydrological processes. The other limitation is that during the substantial rainfall period, the inundation flow was reported to be strongest near the levees, and erosion features were frequently found69. The eroded deposits vary their features corresponding to the types, extents, intensity of floods and surrounding environments. These replenished sediments would change the geomorphological situation of the rivers and affect flow directions70, which might change the inundation characteristics during extreme weather. An improved understanding of the feedback effects, the effects of floods on land surface elevation changes, would be useful to fully understand the compound hazards between floods and the land surface elevation changes71.

Supplementary Information

Author contributions

M.O. and T.T. conceived of the study. Y.I. and M.O. collated the database. M.O. performed the modeling and analysis. M.O. wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to framing and revising the paper.

Data availability

The spatial distributed precipitations and sea levels are obtained from the Japan Meteorology Agency49,50. The high-resolution digital elevation data are measured with Lidar by Kokusai Kogyo Corporation. Earthquake-induced land surface elevation data are available from the Geospatial Information Authority of Japan29,30. Land cover data are constructed from the Landsat-5 TM images36,37. The soil profiles are obtained from the National Land Agency of soil map in Chiba Prefecture. The river network was digitized from the raster data, and the cross-sections are obtained from official reports64 and site investigations. The elevations of groundwater levels are measured by the Keiyo Natural Gas Association. The river water levels, surveyed inundation areas during the flood events are provided by the government of Chiba Prefecture42,43,64. All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in this contribution are presented in the paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-021-83309-7.

References

- 1.Willner SN, Otto C, Levermannn A. Global economic response to river floods. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2018;8:594–598. doi: 10.1038/s41558-018-0173-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Winsemius HC, Van Beek LPH, Jongman B, Ward PJ, Bouwman A. A framework for global river flood risk assessments. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2013;17:1871–1892. doi: 10.5194/hess-17-1871-2913. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scott DT, Gomez-Velez JD, Jones CN, Harvey JW. Floodplain inundation spectrum across the United States. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:5194. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13184-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jongman B, et al. Declining vulnerability to river floods and the global benefits of adaptation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2015;112:E2271–E2280. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1414439112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kron W. Flood risk = hazard · values · vulnerability. Water Int. 2005;30:58–68. doi: 10.1080/02508060508691837. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhou Q, Leng G, Feng L. Predictability of state-level flood damage in the conterminous United States: The role of hazard, exposure and vulnerability. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:5354. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-05773-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hino M, Belanger ST, Field CB, Davies AR, Mach KJ. High-tide flooding disrupts local economic activity. Sci. Adv. 2019;5:eaau2736. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aau2736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Winsemius NC, et al. Global drivers of future river flood risk. Nat. Clim. Change. 2015;6:381–385. doi: 10.1038/nclimate2893. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blöschl G, et al. Changing climate both increases and decreases European river floods. Nature. 2019;573:108–111. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1495-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arnell NW, Gosling SN. The impacts of climate change on river flood risk at the global scale. Clim. Change. 2016;134:387–401. doi: 10.1007/s10584-014-1084-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ward PJ, et al. A global framework for future costs and benefits of river-flood protection in urban areas. Nat. Clim. Change. 2017;7:642–646. doi: 10.1038/nclimate3350. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hirabayashi Y, et al. Global flood risk under climate change. Nat. Clim. Change. 2013;3:816–821. doi: 10.1038/nclimate1911. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Vuuren DP, et al. The representative concentration pathways: An overview. Clim. Change. 2011;109:5–31. doi: 10.1007/s10584-011-0148-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moss RH, et al. The next generation of scenarios for climate change research and assessment. Nature. 2010;463:747–756. doi: 10.1038/nature08823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koks E. Moving flood risk modelling forwards. Nat. Clim. Change. 2018;8:561–562. doi: 10.1038/s41558-018-0185-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paprotny D, Sebastian A, Morales-Nápoles O, Jonkman SN. Trends in flood losses in Europe over the past 150 years. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:1985. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-04253-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dutta D, Herath S, Musiake K. Flood inundation simulation in a river basin using a physically based distributed hydrological model. Hydrol. Process. 2000;14:497–519. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)109-1085(20000228)14:3<497::AID_HYP951>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dutta D, Herath S, Musiake K. An application of a flood risk analysis system for impact analysis of a flood control plan in a river basin. Hydrol. Process. 2006;20:1365–1384. doi: 10.1002/hyp.6092. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamazaki D, Kanae S, Kim H, Oki T. A physically based description of floodplain inundation dynamics in a global river routing model. Water Resour. Res. 2011;47:W04501. doi: 10.1029/2010WR009726. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith A, et al. New estimates of flood exposure in developing countries using high-resolution population data. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:1814. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09282-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barnard PL, et al. Dynamic flood modeling essential to assess the coastal impacts of climate change. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:4309. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-40742-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luo P, et al. Flood inundation assessment for the Hanoi Central Area, Vietnam under historical and extreme rainfall conditions. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:12623. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-30024-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ly S, Charles C, Degré A. Different methods for spatial interpolation of rainfall data for operational hydrology and hydrological modeling at watershed scale. A review. Biotechnol. Agron. Soc. Environ. 2013;17:392–406. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Larsen MAD, Christensen JH, Butts MB, Refsgaard JC. Local control on precipitation in a fully coupled climate-hydrology model. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:22927. doi: 10.1038/srep22927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seneviratne SI, et al. Investigating soil moisture–climate interactions in a changing climate: A review. Earth Sci. Rev. 2010;99:125–161. doi: 10.1016/j.earscirev.2010.02.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keilholz P, Disse M, Halik U. Effects of land use and climate change on groundwater and ecosystems at the middle reaches of the Tarim River using the MIKE SHE integrated hydrological model. Water. 2015;7:3040–3056. doi: 10.3390/w7063040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moftakhari HR, Salvadori G, Aghakouchak A, Sanders BF, Matthew RA. Compounding effects of sea level rise and fluvial flooding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2017;114:9785–9790. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1620325114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Willner SN, Levermann A, Zhao F, Frieler K. Adaptation required to preserve future high-end river flood risk at present levels. Sci. Adv. 2018;4:eaao1914. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aao1914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ozawa S, et al. Coseismic and postseismic slip of the 2011 magnitude-9 Tohoku-Oki earthquake. Nature. 2011;475:373–376. doi: 10.1038/nature10227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sasajima R, Shibazaki B, Iwamori H, Nishimura T, Nakai Y. Mechanism of subsidence of the Northeast Japan forearc during the late period of a gigantic earthquake cycle. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:5726. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-42169-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dixon TH, et al. Subsidence and flooding in New Orleans. Nature. 2006;441:587–588. doi: 10.1038/441587a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shirzaei M, Bürgmann R. Global climate change and local land subsidence exacerbate inundation risk to the San Francisco Bay Area. Sci. Adv. 2018;4:eaap9243. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aap9243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yin J, Yu D, Wilby R. Modelling the impact of land subsidence on urban pluvial flooding: A case study of downtown Shanghai, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2016;544:744–753. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.11.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang J, et al. Simulating the hydrological cycle in coal mining subsidence areas with a distributed hydrological model. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:39983. doi: 10.1038/srep39983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yao J, Zhang Q, Ye X, Zhang D, Bai P. Quantifying the impact of bathymetric changes on the hydrological regimes in a large floodplain lake: Poyang Lake. J. Hydrol. 2018;561:711–723. doi: 10.1016/j.jhydrol.2018.04.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen H, Ito Y, Sawamukai M, Tokunaga T. Flood hazard assessment in the Kujukuri Plain of Chiba Prefecture, Japan, based on GIS and multicriteria decision analysis. Nat. Hazards. 2015;78:105–120. doi: 10.1007/s11069-015-1699-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen H, Ito Y, Sawamukai M, Su T, Tokunaga T. Spatial and temporal changes in flood hazard potential at coastal lowland area: A case study in the Kujukuri Plain, Japan. Nat. Hazards. 2016;84:1513–1527. doi: 10.1007/s11069-016-2495-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miller MM, Shirzaei M. Land subsidence in Houston correlated with flooding from Hurricane Harvey. Remote Sens. Environ. 2019;225:368–378. doi: 10.1016/j.rse.2019.03.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kulp SA, Strauss BH. New elevation data triple estimates of global vulnerability to sea-level rise and coastal flooding. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:4844. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-12808-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sofia G, Roder G, Dalla Fontana G, Tarolli P. Flood dynamics in urbanised landscape: 100 years of climate and humans’ interaction. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:40527. doi: 10.1038/srep40527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hallegatte S, Green C, Nicholls RJ, Corfee-Morlot J. Future flood losses in major coastal cities. Nat. Clim. Change. 2013;3:802–806. doi: 10.1038/nclimate1979. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chiba Prefecture. Flooding report in Chiba Prefecture (2004) (in Japanese).

- 43.Chiba Prefecture. Flooding report in Chiba Prefecture (2013) (in Japanese).

- 44.DHI Water & Environment. MIKE SHE User Manual, Volume 1: User Guide. DHI Water & Environment: Hørsholm, Denmark (2017).

- 45.DHI Water & Environment . MIKE HYDRO River User Guide. Hørsholm: DHI Water & Environment; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Aonuma K, Ishitani F, Miyoshi H, Watanabe H, Ito K. Soil Map of Japan 1:50,000. Mobara: National Land Agency; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nakamura C, Anzai T, Matsumoto N, Iwai H, Ishitani F. SoilMap of Japan 1:50,000. Anesaki: National Land Agency; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen J, Hill AA, Urbano LD. A GIS-based model for urban flood inundation. J. Hydrol. 2009;373:184–192. doi: 10.1016/j.jhydrol.2009.04.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Japan Meteorological Agency. Radar-AMeDAS Precipitation. CD-ROM (2004).

- 50.Japan Meteorological Agency. Radar-AMeDAS Precipitation. CD-ROM (2013).

- 51.Bui DT, et al. Novel hybrid evolutionary algorithms for spatial prediction of floods. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:15364. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-33755-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tanoue M, Hirabayashi Y, Ikeuchi H. Global-scale river flood vulnerability in the last 50 years. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:36021. doi: 10.1038/srep36021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cook A, Merwade V. Effect of topographic data, geometric configuration and modeling approach on flood inundation mapping. J. Hydrol. 2009;377:131–142. doi: 10.1016/j.jhydrol.2009.08.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Md Ali A, Solomatine DP, Di Baldassarre G. Assessing the impact of different sources of topographic data on 1-D hydraulic modelling of floods. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2015;19:631–643. doi: 10.5194/hess-19-631-2015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yan K, Di Baldassarre G, Solomatine DP. Exploring the potential of SRTM topographic data for flood inundation modelling under uncertainty. J. Hydroinformatics. 2013;15:849–861. doi: 10.2166/hydro.2013.137. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yan K, Di Baldassarre G, Solomatine DP, Schumann GJ-P. A review of low-cost space borne data for flood modelling: Topography, flood extent and water level. Hydrol. Process. 2015;29:3368–3387. doi: 10.1002/hyp.10449. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Di Baldassarre G, Schumann G, Bates PD, Freer JE, Beven KJ. Flood-plain mapping: A critical discussion of deterministic and probabilistic approaches. Hydrol. Sci. J. J. Des. Sci. Hydrol. 2010;55:364–376. doi: 10.1080/02626661003683389. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brandimarte L, Di Baldassarre G. Uncertainty in design flood profiles derived by hydraulic modelling. Hydrol. Res. 2012;43:753–761. doi: 10.2166/nh.2011.086. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pappenberger F, Beven KJ, Ratto M, Matgen P. Multi-method global sensitivity analysis of flood inundation models. Adv. Water Resour. 2008;31:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.advwatres.2007.04.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wijesekara GN, Farjad B, Gupta A, Qiao Y, Marceau DJ. A comprehensive landuse/hydrological modeling system for scenario simulations in the Elbow River watershed, Alberta, Canada. Environ. Manag. 2014;53:357–381. doi: 10.1007/s00267-013-0220-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Thompson JR, Green AJ, Kingston DG. Potential evapotranspiration-related uncertainty in climate change impacts on river flow: An assessment for the Mekong River basin. J. Hydrol. 2014;510:259–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jhydrol.2013.12.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Long SA, et al. Modeling the impacts of restoration efforts on phosphorus loading and transport through Everglades Nation Park, FL, USA. Sci. Total Environ. 2015;520:81–95. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.01.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Loinaz MC, Gross D, Unnasch R, Butts M, Bauer-Gottwein P. Modeling ecohydrological impacts of land management and water use in the Silver Creek basin, Idaho. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosciences. 2014;119:487–507. doi: 10.1002/2012JG002133. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transportation. River water level information. http://www.river.go.jp/ (2020).

- 65.Tamura T, Masuda F, Sakai T, Fujiwara O. Temporal development of prograding beach-shoreface deposits: The Holocene of Kujukuri coastal plain, eastern Japan. Mar. Geol. 2003;198:191–207. doi: 10.1016/S0025-3227(03)00123-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kristensen KJ, Jensen SE. A model for estimate actual evapotranspiration from potential evapotranspiration. Hydrol. Res. 1975;6:170–188. doi: 10.2166/hn.1975.0012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Efron B, Tibshirani RJ. An Introduction to the Bootstrap. Chapman and Hall/CRC Monographs on Statistics and Applied Probability. London: Taylor & Francis; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Arcement GJ, Schneider VR. Guide for Selecting Manning’s Roughness Coefficients for Natural Channels and Flood Plains. Water Supply Paper. Washington, DC: U.S. Geological Survey; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Matsumoto D, et al. Erosion and sedimentation during the September 2015 flooding of the Kinu River, central Japan. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:34168. doi: 10.1038/srep34168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Stähly S, Franca MJ, Robinson CT, Schleiss AJ. Sediment replenishment combined with an artificial flood improves river habitats downstream of a dam. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:5176. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-41575-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Vahedifard F, Aghakouchak A, Jafari NH. Compound hazards yield Louisianca flood. Science. 2016;353:1374–1374. doi: 10.1126/science.aai8579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The spatial distributed precipitations and sea levels are obtained from the Japan Meteorology Agency49,50. The high-resolution digital elevation data are measured with Lidar by Kokusai Kogyo Corporation. Earthquake-induced land surface elevation data are available from the Geospatial Information Authority of Japan29,30. Land cover data are constructed from the Landsat-5 TM images36,37. The soil profiles are obtained from the National Land Agency of soil map in Chiba Prefecture. The river network was digitized from the raster data, and the cross-sections are obtained from official reports64 and site investigations. The elevations of groundwater levels are measured by the Keiyo Natural Gas Association. The river water levels, surveyed inundation areas during the flood events are provided by the government of Chiba Prefecture42,43,64. All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in this contribution are presented in the paper.