Abstract

Background:

Older adults have worse outcomes after sepsis than young adults. Additionally, alterations of the gut microbiota have been demonstrated to contribute to sepsis-related mortality. We sought to determine if there were alterations in the gut microbiota with a novel sepsis model in old adult mice, which enter a state of persistent inflammation, immunosuppression and catabolism (PICS), as compared to young adult mice, which recover with the sepsis model.

Methods:

Mixed sex old (~20 mo) and young (~4 mo) C57Bl/6J mice underwent cecal ligation and puncture with daily chronic stress (CLP+DCS) and were compared to naive age-matched controls. Mice were sacrificed at CLP+DCS day 7 and feces collected for bacterial DNA isolation. The V3-V4 hypervariable region was amplified, 16S rRNA gene sequencing performed, and cohorts compared. α-Diversity was assessed using Chao1 and Shannon indices using rarefied counts, and β-diversity was assessed using Bray-Curtis dissimilarity.

Results:

Naïve old adult mice had significantly different α and β-diversity compared to naïve adult young adult mice. After CLP+DCS, there was a significant shift in the α and β-diversity (FDR=0.03 for both) of old adult mice (naïve vs. CLP+DCS). However, no significant shift was displayed in the microbiota of young mice that underwent CLP+DCS in regards to α-diversity (FDR=0.052) and β-diversity (FDR=0.12), demonstrating a greater overall stability of their microbiota at 7 days despite the septic insult. The taxonomic changes in old mice undergoing CLP+DCS were dominated by decreased abundance of the order Clostridiales and genera Oscillospira.

Conclusion:

Young adult mice maintain an overall microbiome stability 7 days after CLP+DCS after compared to old adult mice. The lack of microbiome stability could contribute to PICS and worse long-term outcomes in older adult sepsis survivors. Further studies are warranted to elucidate mechanistic pathways and potential therapeutics.

Keywords: Sepsis, microbiome, elderly, persistent inflammation immunosuppression and catabolism syndrome, PICS

Introduction

Sepsis is one of the most common, expensive and inadequately managed syndromes in modern medicine (1). As a leading cause of death (2), sepsis accounts for >$20 billion (5.2%) of total hospital costs in the United States (3). Improved in-hospital mortality has yielded a rapidly expanding population of early sepsis survivors who develop chronic critical illness (CCI) characterized by persistent organ dysfunction requiring prolonged intensive care unit (ICU) treatment. CCI frequently manifests thereafter in the host as low grade systemic inflammation, global immunosuppression and cachexia/muscle wasting (4). Our group has labeled this state the persistent inflammation, immunosuppression and catabolism syndrome (PICS) (4, 5). Sepsis survivors with CCI/PICS are often discharged to long-term acute care facilities, where they experience dismal outcomes, sepsis recidivism, and ~40% post-discharge mortality in 1 year (6–8). Specific treatments for these sepsis survivors are lacking, due in part to: 1) inadequate knowledge of its pathobiology; and 2) a paucity of studies of older adults, the relevant cohort that makes up the majority of adult septic patients (9).

While the frequency of hospitalizations with sepsis for young patients 18 49 years old has barely changed, the frequency of hospitalization with sepsis for older patients age 50–64 years has increased and has risen dramatically for patients age 65 years or greater (10). Overall, in-hospital sepsis mortality is decreasing, but remains significantly higher in older adults (4, 10). In addition, older patients are more likely to endure critical illness and poor acute, subacute and chronic outcomes after sepsis than the young (11, 12). In fact, the aged are at a greater risk for subsequent disability and death, particularly within the first year after the onset of critical illness (11, 12). Add to this a dramatically increasing number of aged individuals around the world (11, 12) and it is unsurprising that the World Health Organization (WHO) has made sepsis a global health priority since 2017 (13). Although septic older adults are much more likely to enter PICS (14), the precise mechanisms that initiate and maintain PICS in older individuals remain undefined.

The microbiota is the collection of trillions of microorganisms that form a symbiont and pathobiont relationship with its host. Alterations in the microbiota have been associated with a variety of disease processes (15). Previous research has revealed an association of the host microbiota to outcomes after sepsis (16). In addition, recent data indicate that aging plays a role in how the host microbiota responds to an inflammatory insult (17). Our laboratory has recently developed a novel murine model of surgical/abdominal sepsis that combines cecal ligation and puncture with daily chronic stress (CLP+DCS), that not only follows all the recommendations of the “Minimum Quality Threshold in Pre-Clinical Sepsis Studies” (18) but induces PICS in older mice over a period of 1–2 weeks (19). Using this novel model, our goal was to determine differences in the murine microbiome at 7 days between old and young adult mice after CLP+DCS. Furthermore, we sought to determine if differences existed in the gut microbiota in old adult mice (in post-sepsis PICS) versus young adult mice (in post-sepsis recovery), as differences in the microbiome are potentially pathogenic and targets of therapy (20).

Methods

Animals.

All animal experiments were approved by the University of Florida Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and followed Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments (ARRIVE) guidelines (https://www.nc3rs.org.uk/arrive-guidelines). The animals were cared for and used according to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (21). Mixed gender C57BL/6J (B6) mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) and the National Institute on Aging (Baltimore, MD). Mice were cared for by the University of Florida Animal Care Services and housed in transparent cages (three to four animals of same sex/age per cage) under specific pathogen-free conditions in a single room. Animals were provided standard irradiated pelleted diet and water ad libitum for the duration of the study. Prior to initiation of the experiment, mice were acclimated to a 12-hour light-dark cycle for 14 days. Due to the coprophagic nature of mice, this assured that mice in the same cage would have similar microbiota composition and structure (22). Only animals of the same sex, age, and treatment group were housed together.

Intra-Abdominal Sepsis and Daily Chronic Stress Model.

In order to recapitulate the human condition of PICS, a murine model of sepsis and inflammation previously described by our laboratory was utilized (19). Briefly, old (18–22 month old, n=11) and young (3–5 month old; n=11) B6 mice underwent general anesthesia with isoflurane. Cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) was performed via a midline laparotomy with exteriorization of the cecum. The cecum was ligated with 2–0 silk suture 1 cm from its tip, a 25-gauge needle was used to puncture the cecum, and the laparotomy was closed in one layer with surgical clips. Buprenorphine analgesia was provided for 48 hours post-surgery. Imipenem monohydrate (25mg/kg in 1mL 0.9% normal saline) was administered subcutaneously 2 hours post-CLP and then continued twice daily for 72 hours. Subsequently, we added a component of daily chronic stress (DCS) to mimic the ICU stay of human patients who develop CCI (19). DCS was conducted by placing mice in weighted plexiglass animal restraint holders (Kent Scientific; Torrington, CT) for 2 hours daily starting the day after CLP. The CLP+DCS mice, along with mixed-gender naïve mice (old n=13, young n=13), were euthanized on day 7 post-CLP+DCS. Mice were euthanized via cervical dislocation following isoflurane inhalation, after which stool from the descending colon was collected under sterile conditions in a laminar flow hood into sterile Eppendorf tubes (Fisher Scientific) and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen immediately.

Our previous work revealed that by 7–14 days after CLP+DCS, compared to young, old mice demonstrated the key aspects of PICS, including increased inflammation, immunosuppression and continued weight loss (19). Additionally, by 7 days post CLP+DCS, young mice had stabilized and even increased their weight, while old mice continued to lose weight (19). Thus, we determined 7 days post CLP+DCS to be an appropriate time to euthanize the mice to collect descending colon for bacterial sequencing.

Bacterial DNA Isolation and 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing.

Whole genome bacterial DNA was isolated from individual animal stool pellets using the QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD) per manufacturer guidelines. Library preparation was performed utilizing the Quick-16S NGS (Next Generation Sequencing) Library Prep Kit (Zymo Research; Irvine, CA) according to manufacturer protocol. The V3-V4 hypervariable region of the 16S rRNA gene was amplified and paired-end adapter sequences with unique 8 nucleotide barcodes were used during library preparation to allow multiplexing. The final PCR products were quantified with quantitative PCR and pooled based on equal molarity. The final pooled library was purified utilizing the Mag-Bind TotalPure NGS kit (Omega Bio-tek, Inc; Norcross, GA); quality control and quantification was performed with TapeStation (Agilent Technologies; Santa Clara, CA) and Qubit (Thermo Fisher Scientific; Waltham, WA). Sequencing was subsequently completed using the Ilumina MiSeq sequencer (Ilumina, Inc; San Diego, CA), producing paired end reads, 300 bases long, which produced 11,834,108 total reads (each end) for the 48 samples.

Statistical analyses.

Reads were preprocessed using Quantitative Insights into Microbial Ecology (QIIME) version 1.9.1(23) including merging, trimming, and filtering at Q20 followed by a filtering step to remove PhiX and mouse sequences using KneadData (http://huttenhower.sph.harvard.edu/kneaddata) utilizing Illumina iGenome PhiX and Mus musculus Ensembl GRCm38 as references. The surviving reads were fed to QIIME’s pick_open_reference_otus.py to pick OTUs at 97% similarity level using the Greengenes 97% reference dataset (release 13_8). Chimeric sequences were detected and removed using QIIME. OTUs that had ≤ 0.005% of the total number of sequences were excluded according to Bokulich and colleagues (24) and the final set contained 9,124,343 reads. Taxonomic assignment was done using the RDP (ribosomal database project) classifier version 2.2 (25) through QIIME with confidence set to 50%. Counts were then normalized and log10 transformed according to the following formula (26):

where RC is the read count for a particular OTU in a particular sample, n is the total number of reads in that sample, the sum of x is the total number of reads in all samples and N is the total number of samples.

Principle Coordinate Analysis (PCoA) was performed on Bray-Curtis distance of the normalized and log10 transformed counts using the phyloseq R package (27). Alpha diversity was assessed using Chao1 and Shannon indexes using rarefied counts (set to 71,621 reads representing the minimum number of reads among all samples). All statistical analyses were performed in R version 3.4.0 (28). A linear Mixed-Effects Model (lme function) in the R nlme package (version 3.1–140), with the REML method was used to fit a generalized mixed linear model of the following form: var ~ state + 1|cage, where var is PCoA axis, Chao1 index, Shannon index, taxa normalized, and log10 transformed count (considering only taxa present in at least 25% of the samples) or log10 read count in each sample. The latter was performed to ensure the sparsity of 16S rRNA count data did not contribute to samples clustering. State is defined as old/young and post-CLP+DCS/naïve and 1|cage indicates that we used the cage as a random effect to account for cohousing effects (26) P-values were obtained from Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) on the above model and were false discovery rate (FDR) corrected using the Benjamini & Hochberg approach (29).

A two-way analysis of variance with Sidak multiple comparison test was used to compare weight loss based on age using Prism 7 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

Results

The microbiota differs between young and old B6 adult mice at baseline.

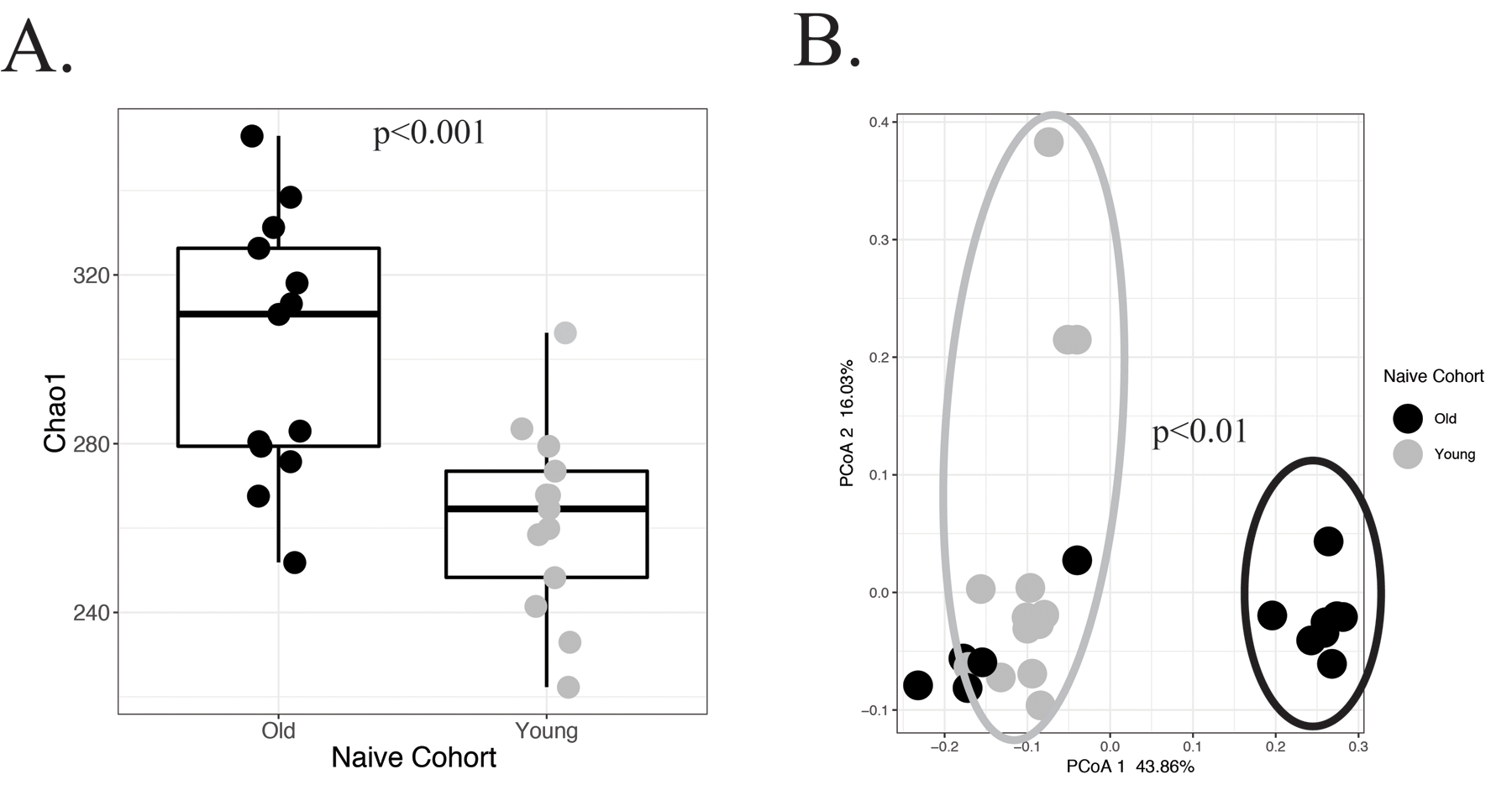

In order to determine compositional differences in the gut microbiota in the old and young adult mice at baseline, stool was collected for 16S rRNA gene sequencing. Genomic analysis of these mice demonstrated increased alpha diversity by Chao1 index (p<0.001; Figure 1A) in old compared to young naïve mice. Furthermore, there was significant clustering at the genus level based on PCoA stratified by age (p<0.01; Figure 1B). The discrimination between aged cohorts for alpha (FDR=0.056) and beta (FDR=0.09) diversity was not significant after FDR correction for cage effect, likely because of the small cohort size. There was increased abundance of multiple bacterial taxa (Table 1) in the naïve old versus naïve young mice, notably genera of Lactobacillus (78.3-fold, FDR<0.0061), Ruminococcus (47.8-fold, FDR=0.02), and Coprococcus (46.1-fold, FDR=0.006). Of note, there was no difference in either alpha (FDR=0.9) or beta (FDR=0.2) diversity between sexes (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Microbiota differences between naïve young and old B6 mice. 16S rRNA gene sequencing was performed of the V3-V4 hypervariable region of old and young B6 mice. (A) A significant difference was demonstrated in the alpha diversity between the two different age cohorts of mice (p<0.001). Additionally, (B) principle coordinate analysis revealed distinct clustering of the microbiota between young and old mice (p<0.01).

Table 1.

Baseline taxonomic differences of young versus old mice prior to CLP+DCS.

| Analysis with cage effect | Analysis without cage effect | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taxon Classification | Fold Change (Old vs Young) |

P value# | FDR# | P value* | FDR* |

| g_Lactobacillus | 78.3 | 0.0395 | 0.291 | <0.001 | <0.01 |

| f_S24–7 | 67.1 | 0.0281 | 0.291 | <0.001 | <0.01 |

| o_Clostridiales | 62.1 | 0.0622 | 0.293 | <0.001 | <0.01 |

| o_Clostridiales | 54.8 | 0.0991 | 0.355 | <0.01 | 0.025 |

| g_Ruminococcus | 47.8 | 0.1413 | 0.404 | <0.01 | 0.022 |

| g_Coprococcus | 46.1 | 0.0301 | 0.291 | <0.001 | <0.01 |

| g_Mucispirillum | 45.9 | 0.0321 | 0.291 | <0.001 | <0.01 |

| f_Ruminococcaceae | 44.6 | 0.0828 | 0.331 | <0.01 | 0.02 |

| f_Ruminococcaceae | 40.7 | 0.0457 | 0.291 | <0.01 | 0.01 |

| f_Lachnospiraceae | 33.5 | 0.162 | 0.422 | 0.016 | 0.05 |

Analysis performed both to control for cage effect (#) and without (*); False discovery rate (FDR) correction for multiple hypothesis testing.

Old mice fail to recover alterations in their microbiota 7 days after CLP+DCS.

Similar to the results of our published model for CLP+DCS (19), there was a significant loss of weight from baseline for both old and young mice (p <0.05) after CLP+DCS. The mean percent weight loss at 7 days post CLP+DCS was greater in old adult mice (19.6%, p<0.05) as compared to young adult mice (9.6%, p<0.05), again consistent with our previously published results (19). Additionally, old mice had increased mortality compared to young mice subjugated to CLP+DCS. A greater proportion of young mice survived (92%) compared with old mice (57%) as expected given our previously published data (19).

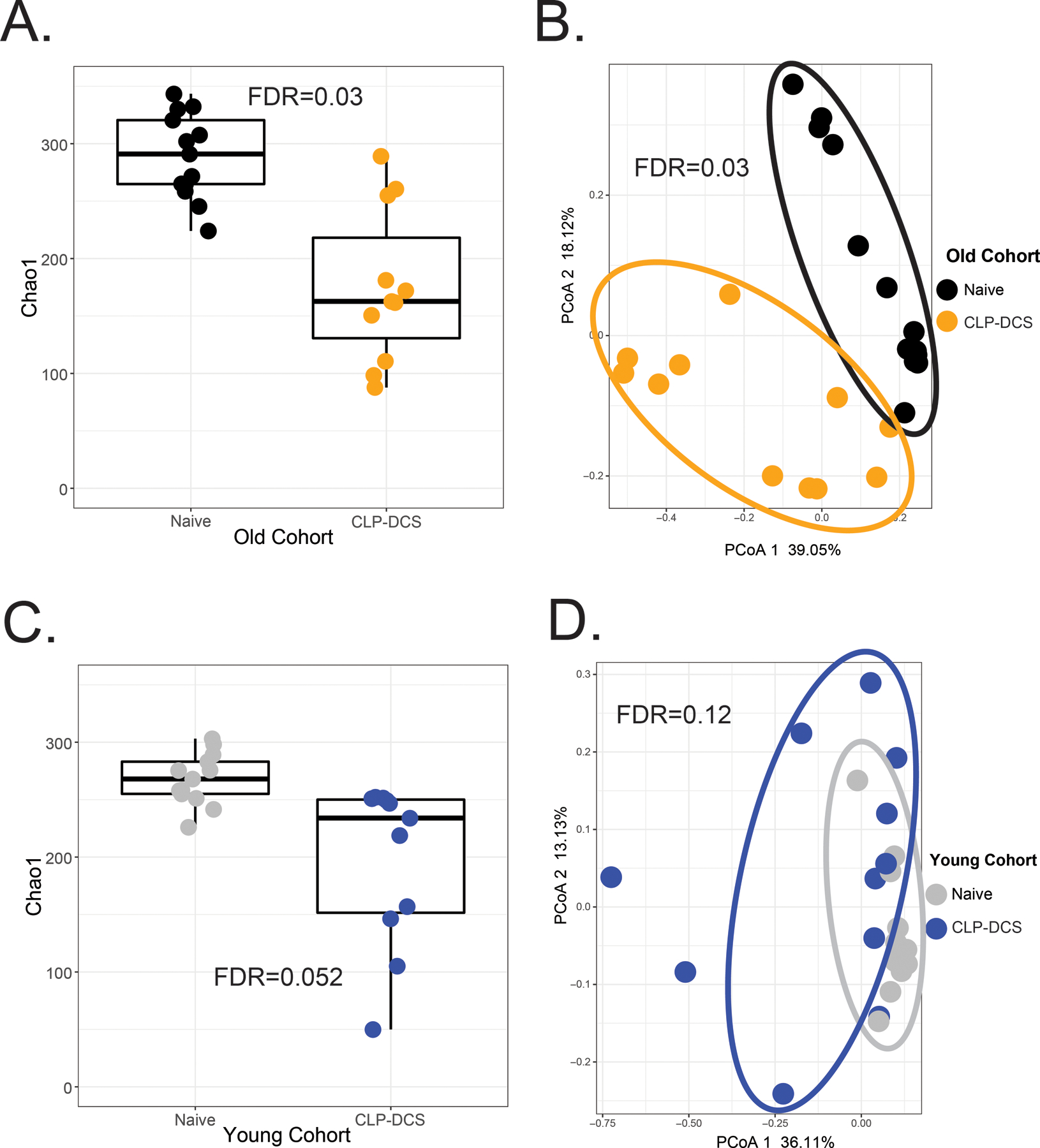

The 16S rRNA sequencing analysis of samples demonstrated a significant difference in alpha and beta diversity between old naïve mice compared to old CLP+DCS mice, whereas young mice maintained microbiota stability between their naïve and CLP+DCS cohorts as evidenced by a lack of significant difference between the young cohorts. Specifically, there was a decrease in alpha diversity based on Chao1 index in old adult CLP+DCS mice compared to old naïve control (Figure 2A; FDR [for cage effect]=0.03). Furthermore, old adult mouse cohorts clustered differently on PCoA analysis (Figure 2B; FDR=0.03). This change was overwhelmingly dominated by the Firmicutes phylum with various microbes of the order Clostridiales and genus Oscillospira noted on sequencing, with a 78-fold and 44-fold increase, respectively, in naïve old adult mice compared to old adult CLP+DCS mice (Table 2; FDR=0.004 and FDR=0.007, respectively). Alterations in microbiota richness and diversity were not observed in young adult naïve mice versus young adult CLP+DCS mice, demonstrating stability of the microbiome in these animals at 7 days after sepsis. These young cohorts demonstrated similar alpha diversity on Chao1 index (Figure 2C; FDR=0.052) and beta diversity on PCoA plot (Figure 2D; FDR=0.12) regardless of exposure to CLP-DCS.

Figure 2.

Microbiota richness and diversity of old and young mice 7 days after CLP+DCS. (A and B). Sequencing of the V3-V4 hypervariable region of isolated16S rRNA gene demonstrated significantly different alpha (A; FDR=0.03) and beta (B; FDR=0.03) diversity in old mice that underwent CLP+DCS (n=11) versus non-septic (naïve old adult controls, n=13) based on Chao1 index and principle coordinate analysis (PCoA), respectively. (C and D) Changes in microbiota alpha diversity were not evident in young mice undergoing CLP+DCS (C; FDR=0.052). Young mice 7 days after CLP+DCS (n=11) demonstrated relative stability in their microbiota despite sepsis, as evident by the lack of cohort separation on PCoA (D; FDR=0.12).

Table 2.

Taxonomic changes of naïve old mice versus old mice after CLP+DCS.

| Analysis with cage effect | Analysis without cage effect | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taxon Classification | Fold Change (Naive vs CLP+DCS) |

P value# | FDR# | P value* | FDR* |

| o_Clostridiales | 78.5 | 0.011 | 0.094 | <0.001 | <0.01 |

| o_Clostridiales | 51.4 | 0.027 | 0.159 | <0.01 | 0.014 |

| o_Clostridiales | 44.9 | 0.003 | 0.04 | <0.001 | <0.01 |

| g_Oscillospira | 44.1 | 0.016 | 0.112 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| o_Clostridiales | 41.9 | 0.026 | 0.157 | <0.01 | 0.018 |

| o_Clostridiales | 39.8 | <0.01 | 0.04 | <0.001 | <0.01 |

| g_Oscillospira | 39.4 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| o_Clostridiales | 32.9 | <0.001 | <0.01 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| o_RF39 | 27.3 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| o_Clostridiales | 24.8 | <0.01 | 0.037 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

Analysis performed both to control for cage effect (#) and without (*); False discovery rate (FDR) correction for multiple hypothesis testing.

Discussion

Using our mouse sepsis model (CLP+DCS) emulating the human condition of PICS (19), we found that old adult mice failed to stabilize their gut microbiota 7 days after a septic insult. Despite the higher microbial diversity compared to young before CLP+DCS, young mice maintained a stable microbiota at 7 days after sepsis despite the CLP+DCS insult. This difference in baseline diversity is likely secondary to a more developed microbial community structure in the aged mice, which is also seen in humans (30).

Maturation of the gut microbiome and diversification begins in infancy, substantially increases in the first three years of life due to exposure to various food products and to environmental factors, and attains relative stability through adulthood (30). The gut microbiome interacts and shapes the immune system to maintain homeostasis and intestinal integrity to protect host from the invasion of host tissues’ opportunistic pathogens (31), and can interact with distant organs (32). The homeostatic relationship between the gut microbiota and the host can be compromised by disrupting and destabilizing the microbiota in immunodeficient states such as aging and related comorbidities (31, 33). In particular, multi-factorial age-related changes decrease the microbial diversity, change proportions toward dominance of pro-inflammatory microbes related to low-grade systemic inflammation, reduce intestinal integrity, and, thus, contribute to the development of age-related conditions such as muscle loss and neurodegeneration (32). Compositional changes in the microbiota are also associated with inflammatory and metabolic conditions, such as inflammatory bowel disease (34), rheumatoid arthritis (35), obesity and diabetes (33).

Aging is associated with a shift in microbial diversity toward commensals such as TM7 bacteria and Proteobacteria, producing pro-inflammatory metabolites like pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) (e.g. lipopolysaccharide), microbe-associated molecular patterns (MAMPs) that activate toll-like receptors 2,4,7 in serum and upregulate cytokine production (interferon gamma, TNF-alpha, interleukin-6 and interleukin-1) leading to increased low-grade inflammation (36, 37). For example, Langille et al. reported lower microbial diversity with taxonomic clustering and dominance of Rikenellaceae, Lachnospiraceae, Ruminococcaceae, especially Alistipes bacterial, and Clostridiaceae genera in older compared to young B6 mice (38), which have been reported as pro-inflammatory bacteria (39, 40). Our results demonstrate taxonomic clustering and increased abundance of Lactobacillus, Ruminococcus and Coprococcus genera in older naïve compared to young mice.

It is accepted that older individuals have a unique response to infection as compared to their younger counterparts (41). The underlying mechanisms of this phenomenon are not fully understood but are presumed to be due to multiple factors. A significant part of this phenomenon has been attributed to senescence (normal aging) and ‘inflammaging’ (chronic low-grade systemic inflammation). These elements prevent older individuals from returning to a physiologic pre-sepsis state (42). Sepsis destabilizes the gut microbiota as shown in this study and others (43). These alterations, referred to as a ‘pathobiome’ (a biome associated with a particular disease) have been shown to contribute to the pathology of sepsis-induced organ failure and mortality (16). As in our old post-CLP+DCS adult mice, human studies have revealed that after sepsis, bacterial diversity is decreased and specific bacterial species are overgrown (44). This has also been demonstrated in septic mice and associated with inflammation in the host (45). Despite reduced diversity and changes in the composition due to aging, the gut microbiome maintains relative stability over time (46). In a study comparing stability of microbiota between community-dwelling and long-stay care of older adults over six months, long-stay care older adults had overall reduced microbial diversity. However, the diversity was not different between subjects with stable or unstable microbiota in both groups. Overall, change in diversity was significant in unstable older adults, and importantly higher diversity at baseline was protective in maintaining the stability of the microbiota (47). Thus, the suboptimal microbiome diversity that can occur with aging and comorbid states can potentially induce in the host an increase susceptibility to impaired microbiota or lead to the host’s failure to stabilize microbiota. Sepsis as a pathological condition and the use of antibiotics have a disruptive effect on the microbiota composition, which in cross-sectional analyses is associated with poor outcomes and PICS (48). Importantly, our results show that only young adult mice maintain an overall stability of the microbiota 7 days after CLP+DCS, in contrast with old adult CLP+DCS mice. This relates to our previous findings of old mice failing to recover from sepsis and entering PICS 7–14 days post CLP+DCS (19). If the stability of the host microbiota is directly associated with the immunologic stability of the post-septic host, potentially providing a survival benefit, it is an area that is deserving of further investigation.

Although our brief report has revealed a key difference in the microbiome response in old versus young adult mice, it has also revealed key questions that need to be answered in future research. In our previous publication (19) our laboratory demonstrated that both CLP and DCS were required to induce PICS in the mouse. However, one limitation of our study is that in the absence of DCS alone group, it is not clear if the changes in microbiome are due to CLP, DCS or both. Previous studies in mice have shown that CLP alone disrupts the gut inflammation barrier and induces a significant increase in intestinal permeability which contributes to the development of multiple organ dysfunction and sepsis (49, 50). We also understand that administration of antibiotics alters the intestinal microbiota (51). Additionally, it has been noted that chronic stress models in mice induces alterations within the gut microbiome (52). Future studies addressing the effect of each component alone will be important in understanding which effect may be key to the microbiome alterations we observed in the old adult mice. Additional studies are required to determine whether the emerging treatment of fecal microbiota transplant (FMT) can change the clinical trajectory or improve the mortality of old CLP+DCS mice. Confirming the clinical utility of FMT in pre-clinical models have clinical relevance in that this can potentially be used for human treatment, potentially altering the current dismal outcomes of the aged human after sepsis.

In conclusion, old naïve mice fail to maintain microbiota stability in response to sepsis. Worse outcomes after sepsis in older individuals may be in part secondary to the inability of the host to maintain or return stability to its gut microbiome. Further animal and human studies are warranted to elucidate mechanistic pathways of microbiome instability, which may in part drive PICS, and potential therapeutics to improve short-term and long-term outcomes in older sepsis patients. This includes investigating gut microbiome axes (i.e. gut-bone marrow, gut-brain, gut-muscle) that exist in mammals that are known to impact the elderly host (53, 54).

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported, in part, by the following National Institutes of Health grants: R01 GM-113945 (PAE), R01 GM-040586 and R01 GM-104481 (LLM), and P50 GM-111152 (LLM, PAE), awarded by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS). In addition, this work was supported, in part, by a postgraduate training grant T32 GM-008721 (DBD) in burns, trauma, and perioperative injury by NIGMS. Finally, the work was supported, in part, by American Heart Association grant 18CDA34080001 (RTM.)

Footnotes

Note: This work was accepted for an oral presentation in at the Shock Society’s 43rd Annual Conference on Shock (Toronto, Canada) before cancellation due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Declarations: The authors declare that they have no relevant conflicts of interests.

References

- 1.Angus DC, van der Poll T: Severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med 369(21):2063, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gaieski DF, Edwards JM, Kallan MJ, Carr BG: Benchmarking the incidence and mortality of severe sepsis in the United States. Crit Care Med 41(5):1167–1174, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Torio CM, Moore BJ: National Inpatient Hospital Costs: The Most Expensive Conditions by Payer, 2013: Statistical Brief #204. In: Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs. Rockville (MD); 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gentile LF, Cuenca AG, Efron PA, Ang D, Bihorac A, McKinley BA, Moldawer LL, Moore FA: Persistent inflammation and immunosuppression: a common syndrome and new horizon for surgical intensive care. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 72(6):1491–1501, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stortz JA, Murphy TJ, Raymond SL, Mira JC, Ungaro R, Dirain ML, Nacionales DC, Loftus TJ, Wang Z, Ozrazgat-Baslanti T et al. : Evidence for Persistent Immune Suppression in Patients Who Develop Chronic Critical Illness After Sepsis. Shock 49(3):249–258, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goodwin AJ, Rice DA, Simpson KN, Ford DW: Frequency, cost, and risk factors of readmissions among severe sepsis survivors. Crit Care Med 43(4):738–746, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stortz JA, Mira JC, Raymond SL, Loftus TJ, Ozrazgat-Baslanti T, Wang Z, Ghita GL, Leeuwenburgh C, Segal MS, Bihorac A et al. : Benchmarking clinical outcomes and the immunocatabolic phenotype of chronic critical illness after sepsis in surgical intensive care unit patients. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 84(2):342–349, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brakenridge SC, Efron PA, Cox MC, Stortz JA, Hawkins RB, Ghita G, Gardner A, Mohr AM, Anton SD, Moldawer LL et al. : Current Epidemiology of Surgical Sepsis: Discordance Between Inpatient Mortality and 1-year Outcomes. Ann Surg 270(3):502–510, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stortz JA, Raymond SL, Mira JC, Moldawer LL, Mohr AM, Efron PA: Murine Models of Sepsis and Trauma: Can We Bridge the Gap? ILAR J 58(1):90–105, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kumar G, Kumar N, Taneja A, Kaleekal T, Tarima S, McGinley E, Jimenez E, Mohan A, Khan RA, Whittle J et al. : Nationwide trends of severe sepsis in the 21st century (2000–2007). Chest 140(5):1223–1231, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baldwin MR: Measuring and predicting long-term outcomes in older survivors of critical illness. Minerva Anestesiol 81(6):650–661, 2015. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brummel NE, Balas MC, Morandi A, Ferrante LE, Gill TM, Ely EW: Understanding and reducing disability in older adults following critical illness. Crit Care Med 43(6):1265–1275, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Organization WH: Improving the prevention, diagnosis and clinical management of sepsis (WHA70.7). Geneva: WHO, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brakenridge SC, Efron PA, Stortz JA, Ozrazgat-Baslanti T, Ghita G, Wang Z, Bihorac A, Mohr AM, Brumback BA, Moldawer LL et al. : The impact of age on the innate immune response and outcomes after severe sepsis/septic shock in trauma and surgical intensive care unit patients. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 85(2):247–255, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thomas H: Gut microbiota: Targeting of specific microbial species mitigates colitis. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 15(3):132, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alverdy JC, Krezalek MA: Collapse of the Microbiome, Emergence of the Pathobiome, and the Immunopathology of Sepsis. Crit Care Med 45(2):337–347, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wheatley EG, Curtis BJ, Hulsebus HJ, Boe DM, Najarro K, Ir D, Robertson CE, Choudhry MA, Frank DN, Kovacs EJ: Advanced Age Impairs Intestinal Antimicrobial Peptide Response and Worsens Fecal Microbiome Dysbiosis Following Burn Injury in Mice. Shock 53(1):71–77, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Osuchowski MF, Ayala A, Bahrami S, Bauer M, Boros M, Cavaillon JM, Chaudry IH, Coopersmith CM, Deutschman CS, Drechsler S et al. : Minimum Quality Threshold in Pre-Clinical Sepsis Studies (MQTiPSS): An International Expert Consensus Initiative for Improvement of Animal Modeling in Sepsis. Shock 50(4):377–380, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stortz JA, Hollen MK, Nacionales DC, Horiguchi H, Ungaro R, Dirain ML, Wang Z, Wu Q, Wu KK, Kumar A et al. : Old Mice Demonstrate Organ Dysfunction as well as Prolonged Inflammation, Immunosuppression, and Weight Loss in a Modified Surgical Sepsis Model. Crit Care Med 47(11):e919–e929, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim SM, DeFazio JR, Hyoju SK, Sangani K, Keskey R, Krezalek MA, Khodarev NN, Sangwan N, Christley S, Harris KG et al. : Fecal microbiota transplant rescues mice from human pathogen mediated sepsis by restoring systemic immunity. Nat Commun 11(1):2354, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Research Council (US) Committee for the Update of the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. 8th ed. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Franklin CL, Ericsson AC: Microbiota and reproducibility of rodent models. Lab Anim (NY) 46(4):114–122, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Caporaso JG, Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J, Bittinger K, Bushman FD, Costello EK, Fierer N, Pena AG, Goodrich JK, Gordon JI et al. : QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat Methods 7(5):335–336, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bokulich NA, Subramanian S, Faith JJ, Gevers D, Gordon JI, Knight R, Mills DA, Caporaso JG: Quality-filtering vastly improves diversity estimates from Illumina amplicon sequencing. Nat Methods 10(1):57–59, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang Q, Garrity GM, Tiedje JM, Cole JR: Naive Bayesian classifier for rapid assignment of rRNA sequences into the new bacterial taxonomy. Appl Environ Microbiol 73(16):5261–5267, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McCafferty J, Muhlbauer M, Gharaibeh RZ, Arthur JC, Perez-Chanona E, Sha W, Jobin C, Fodor AA: Stochastic changes over time and not founder effects drive cage effects in microbial community assembly in a mouse model. ISME J 7(11):2116–2125, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McMurdie PJ, Holmes S: phyloseq: an R package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of microbiome census data. PLoS One 8(4):e61217, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Team RC: R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y: Controlling the False Discovery Rate - a Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. J R Stat Soc B 57(1):289–300, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yatsunenko T, Rey FE, Manary MJ, Trehan I, Dominguez-Bello MG, Contreras M, Magris M, Hidalgo G, Baldassano RN, Anokhin AP et al. : Human gut microbiome viewed across age and geography. Nature 486(7402):222–227, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hooper LV, Littman DR, Macpherson AJ: Interactions between the microbiota and the immune system. Science 336(6086):1268–1273, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lahiri S, Kim H, Garcia-Perez I, Reza MM, Martin KA, Kundu P, Cox LM, Selkrig J, Posma JM, Zhang H et al. : The gut microbiota influences skeletal muscle mass and function in mice. Sci Transl Med 11(502), 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cani PD, Possemiers S, Van de Wiele T, Guiot Y, Everard A, Rottier O, Geurts L, Naslain D, Neyrinck A, Lambert DM et al. : Changes in gut microbiota control inflammation in obese mice through a mechanism involving GLP-2-driven improvement of gut permeability. Gut 58(8):1091–1103, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Franzosa EA, Sirota-Madi A, Avila-Pacheco J, Fornelos N, Haiser HJ, Reinker S, Vatanen T, Hall AB, Mallick H, McIver LJ et al. : Gut microbiome structure and metabolic activity in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Microbiol 4(2):293–305, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van den Broek MF, van Bruggen MC, Koopman JP, Hazenberg MP, van den Berg WB: Gut flora induces and maintains resistance against streptococcal cell wall-induced arthritis in F344 rats. Clin Exp Immunol 88(2):313–317, 1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fransen F, van Beek AA, Borghuis T, Aidy SE, Hugenholtz F, van der Gaast-de Jongh C, Savelkoul HFJ, De Jonge MI, Boekschoten MV, Smidt H et al. : Aged Gut Microbiota Contributes to Systemical Inflammaging after Transfer to Germ-Free Mice. Front Immunol 8:1385, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hearps AC, Martin GE, Angelovich TA, Cheng WJ, Maisa A, Landay AL, Jaworowski A, Crowe SM: Aging is associated with chronic innate immune activation and dysregulation of monocyte phenotype and function. Aging Cell 11(5):867–875, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Langille MG, Meehan CJ, Koenig JE, Dhanani AS, Rose RA, Howlett SE, Beiko RG: Microbial shifts in the aging mouse gut. Microbiome 2(1):50, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maffei VJ, Kim S, Blanchard Et, Luo M, Jazwinski SM, Taylor CM, Welsh DA: Biological Aging and the Human Gut Microbiota. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 72(11):1474–1482, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moschen AR, Gerner RR, Wang J, Klepsch V, Adolph TE, Reider SJ, Hackl H, Pfister A, Schilling J, Moser PL et al. : Lipocalin 2 Protects from Inflammation and Tumorigenesis Associated with Gut Microbiota Alterations. Cell Host Microbe 19(4):455–469, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Horiguchi H, Loftus TJ, Hawkins RB, Raymond SL, Stortz JA, Hollen MK, Weiss BP, Miller ES, Bihorac A, Larson SD et al. : Innate Immunity in the Persistent Inflammation, Immunosuppression, and Catabolism Syndrome and Its Implications for Therapy. Front Immunol 9:595, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hazeldine J, Lord JM, Hampson P: Immunesenescence and inflammaging: A contributory factor in the poor outcome of the geriatric trauma patient. Ageing Res Rev 24(Pt B):349–357, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zaborin A, Smith D, Garfield K, Quensen J, Shakhsheer B, Kade M, Tirrell M, Tiedje J, Gilbert JA, Zaborina O et al. : Membership and behavior of ultra-low-diversity pathogen communities present in the gut of humans during prolonged critical illness. mBio 5(5):e01361–01314, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wan YD, Zhu RX, Wu ZQ, Lyu SY, Zhao LX, Du ZJ, Pan XT: Gut Microbiota Disruption in Septic Shock Patients: A Pilot Study. Med Sci Monit 24:8639–8646, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu Z, Li N, Fang H, Chen X, Guo Y, Gong S, Niu M, Zhou H, Jiang Y, Chang P et al. : Enteric dysbiosis is associated with sepsis in patients. FASEB J:fj201900398RR, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Claesson MJ, Cusack S, O’Sullivan O, Greene-Diniz R, de Weerd H, Flannery E, Marchesi JR, Falush D, Dinan T, Fitzgerald G et al. : Composition, variability, and temporal stability of the intestinal microbiota of the elderly. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108 Suppl 1:4586–4591, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jeffery IB, Lynch DB, O’Toole PW: Composition and temporal stability of the gut microbiota in older persons. ISME J 10(1):170–182, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Krezalek MA, DeFazio J, Zaborina O, Zaborin A, Alverdy JC: The Shift of an Intestinal “Microbiome” to a “Pathobiome” Governs the Course and Outcome of Sepsis Following Surgical Injury. Shock 45(5):475–482, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Haak BW, Wiersinga WJ: The role of the gut microbiota in sepsis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2(2):135–143, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yoseph BP, Klingensmith NJ, Liang Z, Breed ER, Burd EM, Mittal R, Dominguez JA, Petrie B, Ford ML, Coopersmith CM: Mechanisms of Intestinal Barrier Dysfunction in Sepsis. Shock 46(1):52–59, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Knoop KA, McDonald KG, Kulkarni DH, Newberry RD: Antibiotics promote inflammation through the translocation of native commensal colonic bacteria. Gut 65(7):1100–1109, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bailey MT: Influence of stressor-induced nervous system activation on the intestinal microbiota and the importance for immunomodulation. Adv Exp Med Biol 817:255–276, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Santisteban MM, Kim S, Pepine CJ, Raizada MK: Brain-Gut-Bone Marrow Axis: Implications for Hypertension and Related Therapeutics. Circ Res 118(8):1327–1336, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Grosicki GJ, Fielding RA, Lustgarten MS: Gut Microbiota Contribute to Age-Related Changes in Skeletal Muscle Size, Composition, and Function: Biological Basis for a Gut-Muscle Axis. Calcif Tissue Int 102(4):433–442, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]