Abstract

Short modified oligonucleotides that bind in a sequence-specific way to messenger RNA essential for bacterial growth could be useful to fight bacterial infections. One such promising oligonucleotide is peptide nucleic acid (PNA), a synthetic DNA analog with a peptide-like backbone. However, the limitation precluding the use of oligonucleotides, including PNA, is that bacteria do not import them from the environment. We have shown that vitamin B12, which most bacteria need to take up for growth, delivers PNAs to Escherichia coli cells when covalently linked with PNAs. Vitamin B12 enters E. coli via a TonB-dependent transport system and is recognized by the outer-membrane vitamin B12-specific BtuB receptor. We engineered the E. coli ΔbtuB mutant and found that transport of the vitamin B12-PNA conjugate requires BtuB. Thus, the conjugate follows the same route through the outer membrane as taken by free vitamin B12. From enhanced sampling all-atom molecular dynamics simulations, we determined the mechanism of conjugate permeation through BtuB. BtuB is a β-barrel occluded by its luminal domain. The potential of mean force shows that conjugate passage is unidirectional and its movement into the BtuB β-barrel is energetically favorable upon luminal domain unfolding. Inside BtuB, PNA extends making its permeation mechanically feasible. BtuB extracellular loops are actively involved in transport through an induced-fit mechanism. We prove that the vitamin B12 transport system can be hijacked to enable PNA delivery to E. coli cells.

Significance

Short sequences of nucleic acid analogs show promise as programmable antibacterial compounds. Such oligonucleotides bind to bacterial DNA or RNA and block the expression of essential genes. However, for antibacterial activity, they must enter the bacterial cell. Unfortunately, bacteria do not import oligonucleotides from the environment, and noninvasive delivery methods have not been found. To sustain life, most bacteria need to take up vitamins, including vitamin B12. We demonstrate that vitamin B12 connected to peptide nucleic acid oligonucleotides delivers them to Escherichia coli cells using the vitamin B12 uptake system and describe this mechanism at atomistic detail. Our work paves the way to use bacterial transport systems to deliver oligonucleotides into bacteria.

Introduction

Limited permeability of the two-membrane cell envelope of Gram-negative pathogens is the primary factor underlying their resistance to classical antibiotics (1). The outer membrane selectively permits free diffusion through either an asymmetric lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-glycerophospholipid bilayer or pore-forming β-barrel proteins. Hydrophobic drugs tend to follow the lipid-mediated pathway, whereby their permeation rate depends on the LPS structure that varies among the strains. If a full-length LPS is expressed, the passage of hydrophobic drugs is virtually excluded. On the other hand, the porin-mediated nonspecific transport is utilized only by small (<600 Da) hydrophilic drugs; thus, the outer membrane is impermeable to large and polar antibiotics. The inner membrane, composed of a mix of glycerophospholipids, is a less selective barrier than the outer membrane and allows for transport of most amphiphilic drugs. However, the inner membrane possesses efflux pumps that cooperate with periplasmic fusion proteins and outer-membrane channel proteins to actively expel xenobiotics from the cell. In addition, some bacteria produce and secrete enzymes that inactivate antibiotics through their structural modifications before even entering the cell. The mechanisms of bacterial defense against antibiotics are not only intrinsic but can also be acquired, which often leads to multidrug-resistant strains. Therefore, some unconventional ideas of developing novel antibacterial agents are urgently needed to crack the security codes of pathogens.

One of the most promising and innovative strategies proposed to treat bacterial infections is based on the inhibition of gene expression using antigene or antisense oligonucleotides complementary to, respectively, selected bacterial genes or gene transcripts (2, 3, 4). If the oligonucleotide targets an essential gene, bacterial growth is suppressed. Furthermore, silencing the expression of genes responsible for bacterial resistance to classical antibiotics could restore their clinical efficiency. Because natural oligonucleotides are enzymatically cleaved in bacterial cells and serum, three generations of their synthetic analogs have been developed. Indeed, many modified oligonucleotides, including locked nucleic acids, bridged nucleic acids, phosphorodiamidate morpholino oligonucleotides, and peptide nucleic acids (PNAs), have shown improved biostability and affinity to their targets (4). For example, in PNA, a ribose-phosphate backbone was replaced by a scaffold composed of neutral N-(2-aminoethyl)glycine units linked by peptide bonds (5). This ensures effective hybridization of PNAs with DNA and RNA even at low salt concentrations (6) and elevates PNA stability in the acidic environment. On the other hand, the uncharged backbone diminishes PNA solubility in water as compared to DNA or RNA, which may lead to sequence-dependent PNA aggregation.

Despite the advances in the chemistry of modified oligonucleotides, their medical application as antibacterial agents has not been achieved. The major reason is the difficulty in noninvasive delivery of oligonucleotides to bacterial cells (7,8). To alleviate this problem, covalent coupling of oligonucleotides to various transporters was proposed. For PNA, the most common approach is its conjugation with cell-penetrating peptides, such as (KFF)3K (9), that are believed to disintegrate the cell membrane (10). Despite a reasonable delivery efficacy of (KFF)3K in vitro, its activity is considerably reduced in serum (11). Furthermore, (KFF)3K was shown to possess hemolytic activity (10) and induce allergic reactions in mammalian cells (12); thus, it is unlikely to have future clinical applications. Other transporters used to introduce oligonucleotides to bacterial cells were steroids (13), antibodies (14), and lipids (15), but none have been effective enough to warrant practical applications.

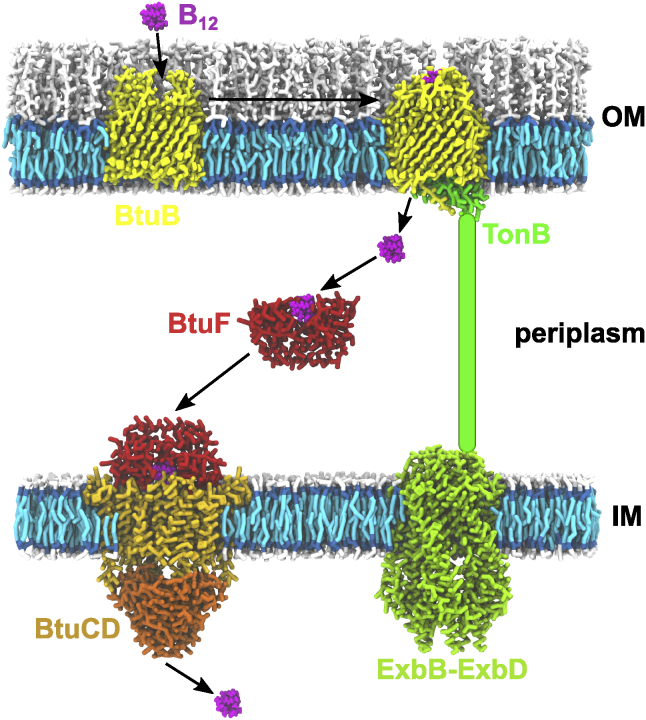

Recently, we have demonstrated that vitamin B12 (B12) efficiently delivered PNA and 2′O-methyl RNA oligomers to Escherichia coli and Salmonella Typhimurium cells (16, 17, 18, 19). However, the delivery route has not been resolved. Vitamin B12, also known as cobalamin, is an enzymatic cofactor critical for mammals and bacteria. Most bacteria cannot produce vitamin B12 and must take it up from the environment. We thus hypothesize that vitamin B12 uses its own transport system to introduce PNA into bacteria. Because cobalamin is a bulky molecule present at low concentrations in the environment, it cannot freely diffuse through the outer-membrane porins or lipid bilayer. Therefore, vitamin B12 is actively imported into bacterial cells by an orchestra of membrane and periplasmic proteins (Fig. 1). In E. coli, vitamin B12 permeates the outer membrane via the BtuB receptor protein (20,21) with the support of the inner-membrane protein TonB. Once in the periplasm, vitamin B12 is captured by the BtuF protein (22). Subsequently, the vitamin B12-BtuF complex is delivered to the inner-membrane BtuCD complex (23), which catalyzes the ATP-hydrolysis-driven transport of vitamin B12 across the inner membrane to the cytoplasm.

Figure 1.

Vitamin B12 transport system in E. coli. Protein models were based on the crystal structures with PDB: 1NQG (only BtuB), 2GSK (BtuB with Cbl and TonB), 1N4A (BtuF), 6TYI (ExbB-ExbD), and 4FI3 (BtuCD). The structure of the periplasmic domain of TonB is unknown, so it was drawn schematically. IM, inner membrane; OM, outer membrane. To see this figure in color, go online.

BtuB belongs to the family of TonB-dependent transporters (TBDTs). TBDTs facilitate uptake of vital but scarce nutrients such as vitamin B12 (BtuB), iron siderophores (FhuA, FhuE, FecA, and FepA), heme (HasR and HemR outer-membrane receptors), sucrose (SuxA), and maltodextrin (MalA) (24,25). TBDTs also serve as a gateway to bacterial cells for colicins (26), bacteriophages (27) and sideromycins (28). BtuB comprises two domains — a 22-stranded β-barrel domain and N-terminal globular-like luminal domain (also termed a hatch or plug domain) that fills the interior of the BtuB barrel. In the holo state of BtuB, cobalamin is bound to the two apices of the luminal domain, where it is partially enclosed by extracellular loops (29,30). Recently, using enhanced sampling molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, we demonstrated that the BtuB loops engage in the induced-fit mechanism during association and subsequent permeation of vitamin B12 through BtuB (31).

Binding of vitamin B12 to BtuB triggers disordering of the N-terminus of the BtuB luminal domain, termed the Ton box (32, 33, 34, 35), so it can extend into the periplasm and be recognized by the TonB protein (36). TonB is fixed in the inner membrane by a single N-terminal helix. The transmembrane region of TonB comprises the extended proline-rich periplasmic domain, whose C-terminus allows TonB to approach the outer membrane (37) and assemble a noncovalent complex with the Ton box of BtuB (30). According to the mechanical pulling model (32), upon the interaction with TonB, the BtuB luminal domain is rearranged to permit the passage of cobalamin through a tunnel that appears inside BtuB. Conformational remodeling of the luminal domain is believed feasible, as long as TonB in the complex with its accessory ExbB and ExbD proteins mediates the proton-motive force generated across the inner membrane (38,39). The noncovalent interaction between the BtuB Ton box and C-terminal domain of TonB is stable under tension up to an ∼200 Å extension of the luminal domain, which was recently demonstrated (40). This corresponds to the unfolding of ∼50 amino acids within the luminal domain, which results in the formation of a channel tailored for vitamin B12 permeation through BtuB (40,41). This also prevents the entry of undesired solutes, such as antibiotics, into the cell, thereby enhancing the specificity of vitamin B12 transport (40).

In this work, we show that the transport of vitamin B12-PNA conjugates across the outer membrane of E. coli occurs through the BtuB protein. For this, we produced the ΔbtuB E. coli mutant and compared the delivery of vitamin B12-PNA into the mutant and wild-type cells. We also provide the details of the permeation mechanism of the vitamin B12-PNA conjugate through BtuB at atomistic resolution using Gaussian force-simulated annealing MD simulations combined with umbrella sampling that we developed (31). We show that the vitamin B12-specific BtuB receptor allows for passage of large PNA oligonucleotides into bacteria, which suggests that this TonB-dependent transport system could also be hijacked by other oligonucleotides.

Materials and methods

Experimental methods

Reagents and conditions

Commercial reagents and solvents were used as received from the supplier. Fmoc-XAL-PEG-PS resin (amine groups loading of 190 μmol/g) for the synthesis of PNA was obtained from Merck (Kenilworth, NJ), and TentaGel S RAM resin (amine groups loading of 240 μmol/g) for the synthesis of peptides was from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Fmoc/Bhoc-protected monomers of PNA (Fmoc-PNA-A(Bhoc)-OH, Fmoc-PNA-G(Bhoc)-OH, Fmoc-PNA-C(Bhoc)-OH, Fmoc-PNA-T-OH) were purchased from Panagene (Daejeon, South Korea). Nα-Fmoc-protected L-amino acids were obtained from Novabiochem (Fmoc-Lys(Boc)-OH) and Sigma-Aldrich (Fmoc-Phe-OH, Fmoc-β-azido-Ala-OH). All reactions were monitored using reverse phase-high-performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC). Preparative chromatography was carried out with C18 reversed-phase silica gel, 90 Å (Sigma-Aldrich), with redistilled water and HPLC-grade MeCN as eluents. HPLC conditions were as follows: column, Eurospher II 100-5 C18, 250 mm × 4.6 mm with a precolumn or Kromasil C18, 5 μm, 250 mm × 4.0 mm; pressure, 10 MPa; flow rate, 1 mL/min; room temperature; detection, UV/Vis at wavelengths of 361 and 267 nm.

Synthesis of vitamin B12 azide derivatives

Cyanocobalamin (100 mg, 75 μmol) was dissolved in 2.5 mL of dry dimethyl sulfoxide at 40°C under argon. Solid 1,10-carbonyl-di(1,2,4-triazole) (50 mg, 300 μmol) was then added and the solution stirred under the atmosphere of argon. After full consumption of the substrate (monitored by RP-HPLC) (∼1.5 h), heating was turned off, and aminoazide NH2-(CH2)12-N3 (100 μL) was added in one portion, followed by Et3N (20 μL). The obtained solution was stirred overnight. After that, it was poured into AcOEt (50 mL) and centrifuged. Further, the precipitate was washed with diethyl ether (2 × 15 mL) and dried in the air. Then, it was dissolved in water and purified by RP column chromatography with a mixture of MeCN and H2O as the eluent. For complete characterization of vitamin B12 azide derivatives and their 1H and 13C NMR spectra, refer to (16).

Synthesis of (KFF)3K-N3

(KFF)3K-N3 was synthesized manually in the solid phase using the Fmoc/t-Bu chemistry on a 100 μmol scale. TentaGel S RAM resin, which has a linker yielding a C-terminal amide upon trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) cleavage of the peptide, was used. Fmoc-protected amino acids, in threefold molar excess, were activated using the mixture of 2-(1H-7-azabenzotriazole-1-yl)-1,1,3,3-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate (HATU), 1-hydroxy-7-azabenzotriazole, and collidine (1:1:2) using the dimethylformamide (DMF)/N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP) (1:1, v/v) solution and coupled for 2 h. The Fmoc groups were deprotected using 20% piperidine in DMF in two cycles (5 and 15 min). To remove the Boc protecting group from Lys and cleave the peptide from the resin, a 60 min treatment with TFA/triisopropylsilane/m-cresol (95:2.5:2.5; v/v/v) mixture was conducted. The obtained crude product was lyophilized and purified by RP-HPLC.

Synthesis of PNA oligomers

PNA oligomers (alkyne-PNA, alkyne-PEG5-PNA, and alkyne-PEG5-PNA scrambled) were in-house synthesized manually using Fmoc solid-phase methodology at 10 μmol scale. Fmoc-XAL PEG PS resin, which has a linker yielding a C-terminal amide upon TFA cleavage of PNA, was used. In all syntheses, Lys was the first monomer attached to the resin. The syntheses were conducted using a 2.5-fold molar excess of the Fmoc/Bhoc-protected monomers and threefold molar excess of the Fmoc-protected Lys and pentynoic acid (or alkyne-PEG5-acid). Double coupling (40 min each) of the monomers, activated by an HATU, N-methylmorpholine, and 2,6-lutidine (0.7:1:1.5) mixture using DMF/NMP (1:1, v/v) solution, was performed. The Fmoc groups were deprotected using 20% (v/v) piperidine in DMF in two cycles (2 × 2 min). After synthesis of the PNA oligomer and N-terminal Fmoc deprotection, the pentynoic acid (or alkyne-PEG5-acid) was attached to the N-terminus. The acids used in threefold molar excess were activated by the use of HATU, 1-hydroxy-7-azabenzotriazole, and collidine (1:1:2) in the DMF/NMP (1:1, v/v) solution and coupled for 2 h. The Fmoc groups of amino acids were removed using 20% piperidine in DMF in two cycles (5 and 15 min). Removal of all protecting groups and cleavage of the PNA oligomer from the resin was accomplished by treatment with a TFA/triisopropylsilane/m-cresol (95:2.5:2.5; v/v/v) mixture for 60 min. The obtained crude products were lyophilized and purified by RP-HPLC.

Synthesis of PNA conjugates with vitamin B12 and (KFF)3K

The conjugates were obtained using copper-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition as reported in (42,43). CuI (1.0 mg, 5 μmol) and tris[(1-benzyl-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)methyl]amine (5.0 mg, 10 μmol) were dissolved in DMF/H2O (0.5 mL, 1:1 v/v) and stirred for 20 min. Further, azide-B12 (or azide-peptide) (3 μmol) and alkyne-PNA (or alkyne-PEG5-PNA) (1 μmol) were added and stirred overnight. The mixtures were then centrifuged and purified by RP-HPLC. For the mass spectra, RP-HPLC chromatograms, and yields of B12-PNA, B12-(CH2)12-PNA, B12-(CH2)12-PNA scrambled, (KFF)3K-PNA, and (KFF)3K-PNA scrambled, refer to (16).

Strain construction

The ΔbtuB E. coli strain from the Keio collection was recently demonstrated to retain an unharmed copy of btuB, in addition to the deleted locus (44), so it was reconstituted.

DNA manipulations were performed using standard procedures and according to the manufacturer’s instructions included in kits for DNA isolation and PCR (Phusion; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Deletion of the E. coli K-12 MG1655 btuB gene was performed using the gene replacement method (45). No antibiotic resistance marker was left in the deletion position to avoid polar effects of the mutation.

Our aim was to remove the btuB open reading frame, leaving intact 1) the region encoding the 5′ untranslated region of messenger RNA (mRNA) of btuB and 2) the murI open reading frame, located downstream of btuB and overlapping (56 bp) with the btuB gene (Figs. S1 and S2). Deletion of btuB was planned in a way to move ATG of the murI gene to the position of ATG of btuB in E. coli MG1655 (Fig. S3) and with the deletion of all of the btuB open reading frame part that does not overlap with murI.

The plasmid for the mutagenesis (pDS132-btuBΔ) was created by the Gibson assembly procedure (Fig. S4; (46)). The DNA fragments used for the assembly were amplified by PCR using the following primer pairs (Table S1): 1) and 2) btuBL/btuBR and murIL/murIR amplification of DNA fragments flanking the btuB gene using MG 1655 genomic DNA as a template, 3) LGM/RGM amplification of the gentamicin resistance cassette from pBBR1-MCS5 (47), and 4) PDS132X/PDS132Y amplification of mobilizable vector pDS132 carrying the sacB gene enabling counterselection with sucrose (48). Oligonucleotides were designed with the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) Genome Database as a template (49).

The assembled plasmid was transformed into E. coli DH5αλ pir cells, carrying the pir gene required for pDS132 replication. Isolated pDS132-btuBΔ plasmid DNA was then used to transform the E. coli strain β2163 (50) (also carrying the pir gene), and a single transformant was used as a donor in a biparental mating with the MG1655 strain (without the pir gene) as the recipient (as described in (51)).

First, the MG1655 derivatives carrying the cointegrate of the chromosome and pDS132-btuBΔ were selected on the lysogeny broth (LB) agar medium containing gentamycin and chloramphenicol. Second, selected strains were cultivated overnight in LB without antibiotics and plated on LB with sucrose. In these conditions, the revertant or strains with the btuB deletion could be obtained. Screening for the btuB deletion was performed by PCR using the LbtuBdXb/RbtuBdBa primers (Table S1). The obtained product of appropriate size was sequenced to confirm proper localization of btuB deletion. Selected ΔbtuB strain was used for further analyses.

Gene expression analysis

E. coli strains (wild-type and ΔbtuB mutant) were grown in LB broth for 16 h as described above. Cells were then settled by centrifugation, and total RNA was isolated using the Total RNA Mini kit (A&A Biotechnology, Gdynia, Poland) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. The RNA of each E. coli strain was extracted from three independent bacterial cultures. Contaminating DNA were removed using DNA-free, DNase Treatment & Removal Kit (Ambion, Austin, TX), according to the manufacturer’s instruction. The RNA concentration and quality were measured using NanoDrop 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Complementary DNA (cDNA) was obtained by reverse transcription of 6 μg of total RNA using the Maxima H Minus First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific), according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Real-time PCR using 5× HOT FIREPol EvaGreen qPCR Mix Plus (ROX) (Solis BioDyne, Tartu, Estonia) was carried out on the LightCycler 96 Instrument (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). Oligonucleotide primer pairs (HPLC purified) specific for the btuB gene were designed using the PrimerQuest software hosted by Integrated DNA Technologies and purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Two pairs of primers for the btuB gene were used: 1) 1query_L1 and 1query_R1 and 2) 2query_L1 and 2query_R1 (Table S2). Relative quantification of gene transcription was performed using the comparative Ct (threshold cycle) method. The relative amount of target cDNA was normalized using the 16S ribosomal RNA gene as internal reference standard and primers F-rrsA and R-rrsA (Tables S2 and S3; (52)).

Transformation of bacterial cells with plasmid carrying red fluorescent protein

The pBBR(rfp) plasmid (16) was isolated using the commercial kit (A&A Biotechnology). The chemically competent E. coli ΔbtuB cells were transformed with pBBR(rfp) according to the method of Kushner (53). The red fluorescent protein (RFP) expression was verified on an ultraviolet transilluminator by measuring red fluorescence.

Determination of the level of red fluorescence

The effect of treating cells with PNA conjugates (at concentrations 0–16 μM) on red fluorescence of E. coli was determined using a standard microdilution method (54). The E. coli strains encoding the mrfp1 gene carried on the pBBR(rfp) plasmid were used (16). After overnight incubation in Davis Minimal Media at 37°C with shaking, cell density (optical density at 600 nm) and fluorescence (λ excitation, 584 nm; λ emission, 610 nm) were measured. Relative fluorescence units (RFUs) were calculated as the background-adjusted fluorescence values divided by the background-adjusted optical density at 600 nm and normalized to the untreated control sample (16). Statistical significance was determined with a two-way ANOVA test using in-house Tcl scripts.

Theoretical methods

System building

The BtuB model was constructed based on the crystal structure of the holo state of BtuB (Protein Data Bank, PDB: 2GSK) (30) adopted from the Orientations of Proteins in Membranes database (55). Four N-terminal amino acids missing in the BtuB crystal structure were added. Protonation states of BtuB titratable groups were set and hydrogen atoms added with Propka 3.0 using the PDB2PQR server (56). Water molecules and calcium ions were preserved as in the crystal structure. The FB15 AMBER force field (57) was used for BtuB.

The B12-(CH2)12-PNA(anti-mrfp1) conjugate with the PNA sequence of CATCTAGTATTTCT-Lys-NH2 (N→C) was built. Parameters for Lys were taken from the FB15 AMBER force field (57). For PNA, the bonded parameters were adopted from Jasiński et al. (58) and the nonbonded from Shields et al. (59). For vitamin B12, the bonded parameters developed by Marques et al. (60) were applied, whereas the nonbonded parameters were set using General Amber Force Field 2 (GAFF2). The atomic charges of vitamin B12 were calculated according to the RESP procedure (61) using Gaussian 09 (62) and antechamber (AmberTools18).

The outer membrane of the E. coli K-12 strain was built as an asymmetric heterogenous lipid bilayer. Lipids were assembled around BtuB using CellMicrocosmos Membrane Editor 2.2 (63). The external leaflet of the membrane was made of 29 LPSs composed of the membrane-forming lipid A and the inner- and outer-core oligosaccharides, without the O antigen. The interior leaflet of the membrane consisted of a mix of six lipids — POPE, PMPE, PMPG, PSPG, QMPE, and OSPE — with the ratio 8:31:8:8:8:6 (64). All phosphate and carboxylic groups in LPS were deprotonated so the total charge of an LPS molecule was −10 e. A combination of Lipid17 (65) and GLYCAM06j (66) force fields was used to assign bonded and nonbonded parameters of the lipid A and oligosaccharide part of LPS, respectively. The average area per lipid of LPS, calculated from the microsecond-long MD simulations of a symmetric bilayer, is 159.36 ± 0.54 Å2, which gives 26.56 ± 0.09 Å2 of area per lipid tail. This agrees with the experimental value of 26 Å2 (67). The interior leaflet phospholipids were parameterized using the Lipid17 force field. The lacking parameters of lipids containing cyclic moieties were set based on the parmchk2 program (AmberTools18) and GAFF2. The atomic charges of all lipids were calculated according to the RESP procedure (61).

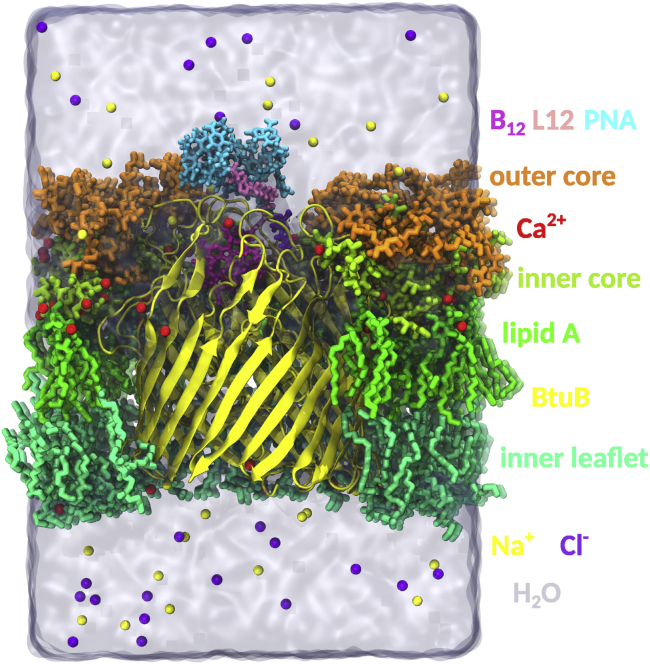

Using xleap (AmberTools18) (68) and Visual Molecular Dynamics (VMD 1.9.3) (69), the system was solvated by adding 20 and 250 Å layers of TIP3P-FB (70) water molecules (in the z-coordinate) over and below the membrane, respectively. The initial system size was 95 × 95 × 330 Å. The negatively charged LPSs were neutralized with calcium ions, and the negative potential of the membrane internal leaflet was balanced with sodium ions. In addition, the ionic strength of 100 mM of NaCl was applied. For the sodium and chloride ions, the parameters adopted from Joung and Cheatham (71) were applied, and for the calcium ions, the parameters of Li and Merz (72) were used. The entire system was composed of ∼242,000 atoms (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

The all-atom model of the complex of vitamin B12-(CH2)12-PNA and BtuB embedded in the asymmetric and heterogenous outer membrane of E. coli K-12 surrounded by explicit water molecules and ions. To see this figure in color, go online.

General MD simulations protocol

Initially, the energy minimization of the system was performed under harmonic restraints of 10 kcal/mol/Å2 set on heavy atoms with the 5000 steps of steepest descent algorithm and 3000 steps of the conjugate gradient method using the sander program (68). The following phases were conducted using NAMD 2.12 (73). In the beginning, the integration time step was set to 0.5 fs. The system was gradually thermalized from 10 to 310 K with solute coordinates fixed in 10 K increments of 125 ps in the NPT ensemble, with a constant pressure of 1 atm controlled using the Langevin piston method. Further, the system was equilibrated for 2.5 ns at 310 K. After that, the whole system was gradually heated from 10 to 310 K in 10 K increments of 50 ps, with harmonic restraints of 10 kcal/mol/Å2 imposed on the nonhydrogen solute atoms. During equilibration, the restraints were released in 10 rounds of 50 ps each. Next, the integration time step was gradually increased from 0.5 to 2 fs, in 0.25 fs increments of 1 ns length, and the system was simulated for 500 ns. Periodic boundary conditions and the particle-mesh Ewald method with a grid spacing of 1.0 Å were used. The hydrogen-containing bonds within nonwater and water molecules were constrained using the RATTLE (74) and SETTLE (75) algorithms, respectively. The cutoff for short-range nonbonded interactions was set to 12 Å, with a switching distance of 10 Å. Trajectories were collected every 5 ps.

Steered molecular dynamics

To perform partial unfolding of the BtuB luminal domain (Fig. S5), we used constant-velocity steered molecular dynamics (SMD) (76,77). The center of mass (COM) of the first N-terminal residue was pulled along the z axis with a constant velocity of 1.0 Å/ns, force constant of 1 kcal/mol/Å2, and force vector of [0, 0, −1]. The COM of the Cα atoms of the lower part of the BtuB barrel domain was harmonically restrained, with a force constant of 100 kcal/mol/Å2, to prevent the protein-membrane system from drifting along the z axis during pulling of the luminal domain.

To achieve the association and permeation of the B12-(CH2)12-PNA(anti-mrfp1) conjugate through BtuB at the luminal domain extension of 197 Å, collective-variable SMD (CVSMD) was applied (78). The steered collective variable was the distance projected onto a normal to the membrane (z axis) between the COM of the conjugate and the dummy atom fixed in the center of the Cbl binding site in BtuB. The Cbl binding site was defined as the average position of the COM of vitamin B12 in the holo state of BtuB with the luminal domain folded. The steering potential moved with an average speed of 1.0 Å/ns, force constant of 50 kcal/mol/Å2, and vector of [0, 0, −1] during permeation and of [0, 0, 1] during association. To enable initial unfolding of the PNA during permeation, we proceeded with pulling Cbl heavy atoms until they completely surpass BtuB. After that, we continued to pull the COM of all nonhydrogen atoms of the conjugate until its full permeation through BtuB. On the association pathway, the COM of all heavy atoms of the conjugate was pulled out of the Cbl binding site in BtuB toward the external environment. During the CVSMD simulations, the luminal domain extension of 197 Å was maintained by a harmonic restraint with a force constant of 100 kcal/mol/Å2 put on the COM of its N-terminus.

Gaussian force-simulated annealing

To enhance conformational sampling and, most importantly, optimize the structure of the BtuB extracellular loops and B12-(CH2)12-PNA conjugate along the conjugate transport pathway, the Gaussian force-simulated annealing (GF-SA) method (31) was used. Artificial Gaussian forces were imposed locally on the BtuB loops to accelerate the torsions around the rotatable bonds within the protein backbone (Cα-C and N-Cα) and side chains (Cα-Cβ). Additionally, external forces were put on PNA to enhance the rotations around the bonds within the PNA backbone (C5∗-C∗ and C2∗-N1∗) and side chains (C7∗-C8∗).

The forces imposed on atoms were calculated as normalized vectors multiplied by a normally distributed pseudorandom number that was generated as previously described (31). The vectors were normal to the planes formed by the following angles: Cα-C-O in the protein backbone and Cα-Cβ-X in the protein side chains, where X is Cγ, Oγ, etc.; C5∗-C∗-O1∗ in the PNA backbone; and C7∗-C8∗-N1 (or C7∗-C8∗-N9) in the PNA side chains. Forces were imposed on the last atoms of these angles.

Gaussian forces were added every second MD step on all of the conjugate PNA monomers and Lys and the following BtuB residues: 177–197 (loop L2), 227–241 (loop L3), 276–289 (loop L4), 323–333 (loop L5), 395–412 (loop L7), 442–458 (loop L8), 487–499 (loop L9), 525–542 (loop L10), and 569–584 (loop L11). The rigid and short loops 1 and 6, as well as prolines, were omitted.

In the GF-SA approach, the standard deviation (SD) of the normally distributed pseudonumbers s was calculated during the simulation according to the function

| (1) |

where a is a maximal SD (35 kcal/mol/Å), b is an integer determining the number of stages during heating or cooling (100), and n is an even integer controlling the gradient of the SD (2). Each heating stage (x ∈ <−100, 0)) lasted 2000 MD steps. Next, the SD was maintained at its maximum (x = 0) for 250,000 MD steps. Cooling (x ∈ (0, 100>) was carried out for 30,000 MD steps in each stage and was followed by 50,000 MD equilibration steps (with no external forces). After 7 ns of the GF-SA procedure, classical MD simulation was performed for 3 ns. Subsequently, the GF-SA-MD procedure was repeated for a number of cycles.

Umbrella sampling

The potential of mean force (PMF) of the association and permeation of the B12-(CH2)12-PNA(anti-mrfp1) conjugate through BtuB was computed with umbrella sampling (US) (79) coupled with the GF-SA approach. The reaction coordinate was the distance projected onto a normal to the membrane (z axis) between the COM of the conjugate and the dummy atom fixed in the center of the vitamin B12-PNA binding site in BtuB. The vitamin B12-PNA binding site was defined as the average location of COM of the conjugate in the holo state of BtuB with the luminal domain folded.

The US windows were initially obtained from CVSMD (for details, see Steered molecular dynamics) and were spaced every 0.5 Å between −25 and 125 Å of the reaction coordinate, with the force constant set to 50 kcal/mol/Å2. To maintain the luminal domain extension of 197 Å, the COM of its N-terminus was harmonically restrained with a force constant of 100 kcal/mol/Å2.

For each window, five consecutive cycles of GF-SA-US were conducted. Each cycle consisted of 7 ns of GF-SA followed by 3 ns of US. So, in total, 15 ns of US with enhanced sampling of BtuB loops and PNA for each window were used to calculate the final PMF.

The PMF was computed using the weighted histograms analysis method (80,81) with the weighted histograms analysis method program (82). The PMF stabilization was tracked every 0.2 ns by measuring the PMF root mean-square deviation calculated from cumulative data (Fig. S7). The reference for the PMF root mean-square deviation calculations was the last PMF (computed based on all collected data).

Data analysis

Trajectories were analyzed with the cpptraj program (Ambertools18) and VMD 1.9.3 using in-house Tcl and C++ scripts. Plots were produced with Gnuplot (v5.2) and Inkscape. Representative conformations were extracted from trajectories using the k-means clustering algorithm. The criteria for hydrogen bonds were donor-acceptor distance ≤3.5 Å and donor-hydrogen-acceptor angle ≥135°. To detect interatomic contacts, only the distance criterion of 3.5 Å was used. To identify the π-π stacking contacts between PNA nucleobases, the distance threshold of 5.5 Å between the base COMs was applied. Descriptive statistics of the data series was computed using in-house C++ scripts. To verify the normality of the data distribution, the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used. The data sets with a not-normal distribution were characterized by median, interquartile range (Q1–Q3), and lower-upper extremes range. In GF-SA-US simulations, only data collected from the conventional US were analyzed.

Results and discussion

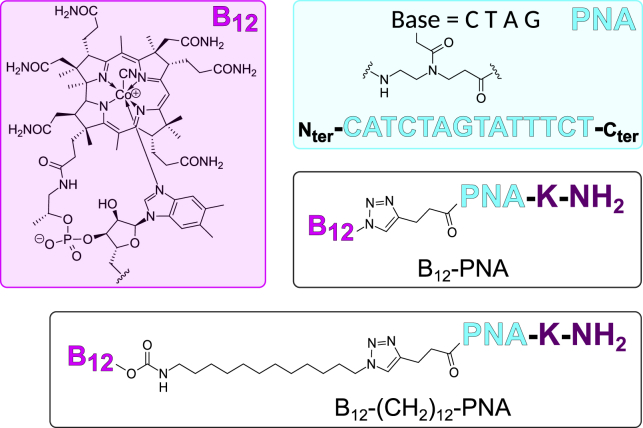

Vitamin B12-PNA conjugates enter E. coli cells through the BtuB receptor

To determine whether vitamin B12 delivers PNA through the outer-membrane BtuB receptor, we investigated the vitamin B12-mediated PNA transport to the wild-type and ΔbtuB mutant E. coli strains. We used cells carrying the mrfp1 gene expressing RFP and a PNA sequence designed to specifically target and silence the mRNA transcript encoding RFP (PNA: Nter-CATCTAGTATTTCT-Cter, Fig. 3). The RFP concentration in the E. coli cells determined their red fluorescence intensity. Therefore, the PNA delivery was quantified by measuring the change in cells’ red fluorescence before and after treatment with vitamin B12-PNA conjugates. Because the number of cells differed between samples (Figs. S8–S10), we applied RFUs that are proportional to the amount of RFP per cell. Transformants of the wild-type and ΔbtuB E. coli strains with the mrfp1 gene were prepared as previously described (16). Next, both strains were cultured in the presence of two different conjugates of vitamin B12 with the anti-mrfp1 PNAs previously shown most effective in silencing the mrfp1 mRNA transcript in E. coli and S. typhimurium cells (16), namely B12-PNA and B12-(CH2)12-PNA. These conjugates bear the same PNA sequence but vary in the length of the spacer and type of the linker connecting vitamin B12 and PNA (Fig. 3). The conjugates were synthesized according to the procedures described in (17,42,43).

Figure 3.

Chemical structure of vitamin B12-PNA and B12-(CH2)12-PNA conjugates. To see this figure in color, go online.

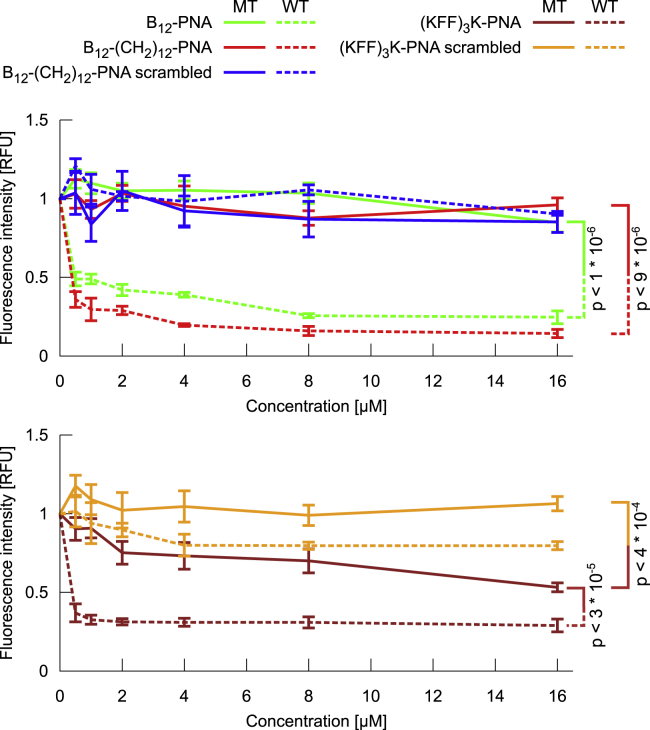

Fluorescence intensity changes of the wild-type and mutant E. coli cells after overnight treatment with the vitamin B12-PNA conjugates are shown in Figs. 4 and S11. We also examined the inhibitory effect of the same PNA sequence but conjugated to a (KFF)3K peptide because the transport of (KFF)3K-PNA does not depend on BtuB. As controls, we used conjugates of vitamin B12 and (KFF)3K with a scrambled PNA sequence (Nter-TTTCTAGTCTCATA-Cter) that is not complementary to mrfp1 mRNA, as well as free vitamin B12, (KFF)3K, and PNA. For all controls and in both E. coli strains, we did not observe any statistically significant concentration-dependent fluorescence changes (Figs. 4 and S12). This ensures that any decrease in red fluorescence of bacteria treated with a conjugate containing the anti-mrfp1 PNA sequence is due to silencing of the mrfp1 mRNA by this PNA; thus, PNA must have been delivered to cells. Indeed, in wild-type E. coli cultured in the presence of the conjugates of vitamin B12-PNA and (KFF)3K-PNA, we observed a concentration-dependent decrease in red fluorescence, which confirms PNA transport by these two carriers and corroborates with (16). Conversely, in mutant ΔbtuB E. coli, the level of RFP production for all vitamin B12-PNA conjugates was virtually unaffected, regardless of the PNA sequence and concentration. Therefore, we argue that vitamin B12 acts as a carrier of PNA to E. coli cells only if the BtuB protein is present in the outer membrane. Otherwise, PNA is not delivered to the mutant cells not possessing BtuB.

Figure 4.

Inhibition of RFP synthesis in E. coli wild-type (WT) and ΔbtuB mutant (MT) strains after the overnight treatment with various concentrations of B12-PNA, B12-(CH2)12-PNA, B12-(CH2)12-PNA scrambled, (KFF)3K-PNA, and (KFF)3K-PNA scrambled. Fluorescence intensity is given in RFUs. The mean values from three (for WT E. coli) and six (for MT E. coli) independent experiments are shown, with error bars calculated as the standard error of the mean. Where relevant, the levels of statistical significance expressed as p-values are also given. To see this figure in color, go online.

In the ΔbtuB E. coli mutant, fluorescence intensity for the (KFF)3K-PNA is lower than for the (KFF)3K-PNA(scrambled). This implies that treating the mutant with anti-mrfp1 (KFF)3K-PNA silences the respective mRNA transcript and inhibits RFP synthesis, confirming the (KFF)3K-PNA uptake. Similarly to the wild-type E. coli, the fluorescence decrease in the presence of (KFF)3K-PNA in the E. coli mutant is dose dependent, although in the wild-type E. coli, the conjugate inhibits the RFP production to a higher extent. We hypothesize that the lower inhibitory effect of (KFF)3K-PNA in the ΔbtuB E. coli may be due to reduced efficiency of transport through the cellular wall, which may have different integrity in the mutant because of a different protein/lipid ratio. Deletion of btuB could alter the activity of the neighboring murI gene whose function is to regulate the biosynthesis of specific components of the cell wall peptidoglycan (83). This may entail lower permeability of (KFF)3K through the cellular wall in the mutant.

In summary, the observed fluorescence intensity changes between wild-type and mutant E. coli demonstrate that vitamin B12-PNA conjugates require BtuB for their transport to E. coli cells.

Mechanism of permeation of vitamin B12-PNA conjugate through BtuB

After confirming that the vitamin B12-PNA conjugate requires BtuB for cell entry, we investigated the mechanism of transport of this conjugate through BtuB. We performed a series of MD simulations of the all-atom model of the system composed of vitamin B12-(CH2)12-PNA bound to BtuB embedded in an asymmetric and heterogeneous lipid bilayer imitating the outer membrane of the E. coli K-12 strain (Fig. 2). We assumed that binding and subsequent permeation of the conjugate through BtuB may occur only after vitamin B12 has been recognized by this receptor. This is in accord with our experiments showing that PNA cannot permeate through BtuB without being conjugated to vitamin B12. Therefore, initially, the conjugate was docked to BtuB to place vitamin B12 at the same position in the binding site as observed in the vitamin B12-BtuB complex. However, because PNA is attached to 5′-OH of vitamin B12 ribose, vitamin B12 orientation in the conjugate is opposite to that of unmodified vitamin B12 in the binding cavity. At the extracellular side of BtuB, PNA adopts a compact and globular structure, similarly as in the bulk solution (Fig. 2; (84)).

Next, we simulated partial unfolding of the BtuB luminal domain using constant-velocity steered MD (Video S1). We assumed that the transport of the conjugate occurs when the extension of the luminal domain is at 197 Å, which is in agreement with the atomic force microscopy experiments (40) and our work on vitamin B12 (31). During steered MD simulations of the luminal domain unfolding, we did not observe any substantial movement of the vitamin B12-PNA conjugate toward the periplasm, probably because of limited conformational sampling. Therefore, to accelerate the permeation of the conjugate, we applied a two-step CVSMD (Video S2).

Furthermore, to evaluate the PMF associated with the transport of vitamin B12-(CH2)12-PNA through BtuB, we applied GF-SA-US (Video S3). This method was developed by us to characterize the PMF of the transport of free vitamin B12 through BtuB (31). We have shown that enhanced sampling of the extracellular loops of BtuB was critical to stabilize the PMF of vitamin B12 permeation. Because PNA conformations in the conjugate obtained during pulling simulations were far from equilibrium, we expanded the GF-SA method to also improve the sampling of PNA.

To compare how enhanced sampling of the BtuB loops and PNA influences the PMF of the conjugate transport through BtuB, we also performed classical US simulations using initial windows as in GF-SA-US. During 15 ns of classical US, the PMF did not stabilize and showed an unphysically high barrier for the permeation of vitamin B12-PNA to the periplasm (Fig. S6). In contrast, in GF-SA-US, PMF already drastically changed after the first GF-SA-US cycle and stabilized after four cycles (Fig. S7). Even though enhanced sampling of the loops and PNA greatly improved the PMF, longer simulations or explicit treatment of additional collective variables may be necessary to achieve convergence of the PMF barrier heights. Nevertheless, from the evolution of PMF after each subsequent GF-SA-US cycle, we do not expect the PMF shape to change significantly by extending the GF-SA-US simulations. Because each GF-SA-US cycle executes a simulated-annealing protocol that optimizes the structure of the BtuB loops and PNA, trapping in local energy minima, a common problem in classical US, does not apply to the GF-SA-US method.

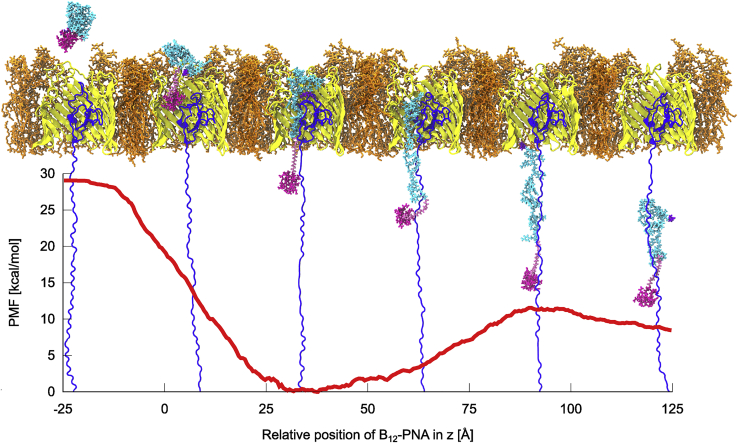

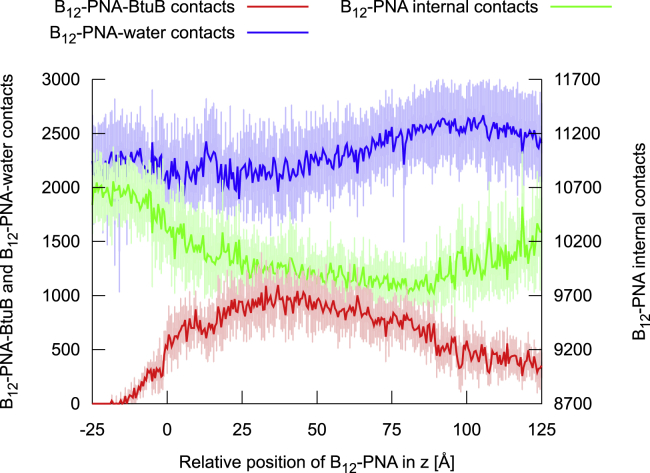

The PMF of both the association of the conjugate with BtuB (z < 0) and its permeation through BtuB (z > 0), together with representative structures, is shown in Fig. 5. When the conjugate is fully dissociated from BtuB at the outer-membrane side (z = −25 Å in Fig. 5), the PMF is leveled at ∼29 kcal/mol. At the beginning of permeation (at z = 0 Å), the PMF is ∼10 kcal/mol lower, suggesting that dissociation of the conjugate from BtuB toward the extracellular side is unlikely. When vitamin B12-PNA enters BtuB (at z = 0–38 Å), the number of contacts between the conjugate and BtuB increases, which corresponds to further decrease in the PMF (Fig. 6). Concurrently, PNA unfolds, which is manifested by a twofold increase in the radius of gyration of the conjugate and longer distances between PNA nucleobases (Fig. 7 A). This is accompanied by a drop in the number of contacts within the conjugate (Fig. 6), including hydrogen bonds and π-π stacking between PNA nucleobases (Fig. S13, A and B).

Figure 5.

The PMF of the transport of vitamin B12-(CH2)12-PNA through BtuB. Insets show representative structures of the system in subsequent transport stages. To see this figure in color, go online.

Figure 6.

The median and lower-upper extremes range of the number of contacts created by vitamin B12-(CH2)12-PNA with BtuB and water molecules and the conjugate internal contacts during its transport through BtuB. To see this figure in color, go online.

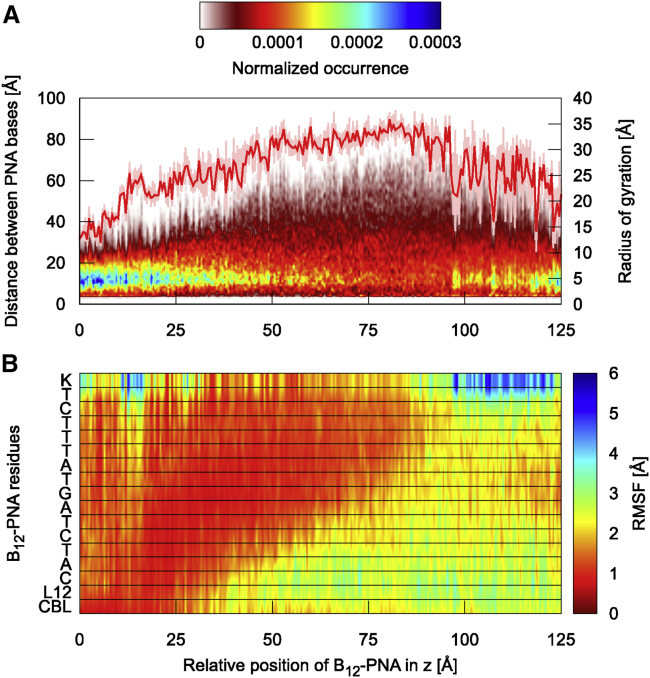

Figure 7.

Radius of gyration and occurrence of the distances measured between PNA nucleobases (A) and residual root mean-square fluctuations (B) of the vitamin B12-(CH2)12-PNA conjugate residues during permeation through BtuB. Labels are defined as follows: L12, linker L12; C, A, T, and G, PNA monomers; K, lysine. For the radius of gyration, the median and lower-upper extremes range are provided. To see this figure in color, go online.

The PMF lowers almost linearly up to z = 38 Å, at which it attains its sole minimum (0 kcal/mol) on the entire transport pathway. The minimal basin is flat, and in the z range of 28–45 Å, the energy does not exceed 1 kcal/mol. The PMF minimum corresponds to the geometry in which the conjugate interacts the most with BtuB (Fig. 6), forming both direct and water-mediated hydrogen bonds (Fig. S14, A and B), as well as nonspecific contacts. In this conformation, vitamin B12 and linker are located outside the BtuB barrel (on its periplasmic side) and bind to the extended luminal domain, whereas the entire PNA moiety is still buried inside BtuB. The PNA strand forms many transient contacts with the BtuB luminal domain, especially with residues 55–68, 71–73, 88–99, 101, and 104–107 (Figs. S15 A and S16 A). Among these, there are groups of amino acids with a hydrophobic side chain, such as Ile, Leu, Gly, Ala, Val, and Phe, or amino acids with a polar uncharged side chain, e.g., Ser, Thr, Glu, and Asp. Only two, D95 and R106, are charged. PNA also interacts with all extracellular loops except L6 (for numbering of loops, see Fig. S5), preferentially with L3 and L8 (Fig. S15 A). Interestingly, among the loops, PNA forms exceptionally durable contacts with ring-containing amino acids such as Y149, F197, Y229, Y232, Y446, H449, Y531, and Y579 or with amino acids possessing rigid and flat groups such as R497 (Fig. S16 B). The majority of contacts with BtuB are formed by PNA bases (Fig. S15 B), which explains the lowest number of π-π stacking interactions within the PNA moiety at this transport stage (Fig. S13 B). Such behavior of the B12-(CH2)12-PNA conjugate ensures low number of contacts between hydrophobic PNA and water molecules (Fig. 6), which is comparable to that in the bulk when PNA is tightly folded and globular. Both binding to BtuB and reducing interactions with water molecules contribute to stabilization of the whole conjugate, which is reflected in the lowest atomic fluctuations at the PMF minimum (Fig. 7 B).

From the PMF minimum, the conformation of vitamin B12-(CH2)12-PNA continues to extend until z equals 85 Å. This coincides with the loss of interactions between the conjugate and BtuB, especially with almost all loops (except L11) (Fig. S15), as well as within the conjugate (Fig. 6). Although the number of hydrogen bonds within the conjugate decreases, the π-π stacking interactions, especially between neighboring PNA bases, become more frequent (Fig. S13). In addition, the conjugate gets increasingly more exposed to solvent; therefore, atomic fluctuations of vitamin B12, the linker, and the PNA N-terminal part, which already exited the BtuB barrel, gradually increase (Fig. 7 B).

At z = 90 Å, when PNA C-terminal bases and Lys make their last contacts with the luminal domain (residues 96–107) and BtuB barrel (residues 470–476 and 508–516) (Figs. S15 and S16, C and D), the PMF reaches its local maximum of 11.5 kcal/mol. In this state, vitamin B12-PNA is internally the least stabilized on the entire transport route (with the lowest number of internal contacts) and the most hydrated (Fig. 6). Afterwards, the conjugate maintains contacts only with the extended luminal domain residues 32–65 (Fig. S15). Concurrently, the number of conjugate internal contacts increases (Fig. 6), including hydrogen bonds and π-π stacking (Fig. S13, A and B). Stacking occurs mainly between neighboring PNA bases, although longer-range base stacking also appears (Fig. S13 C). As a result, the conjugate becomes less extended (Fig. 7 A) and less hydrated (Fig. 6). The fluctuations of the PNA monomers decrease, apart from the C-terminal Lys (Fig. 7 B). This partial refolding of the PNA strand leads to a subtle decrease in PMF, to ∼8.5 kcal/mol, at z = 125 Å. Despite the fact that vitamin B12-PNA bound to the extended luminal domain is less compact and more exposed to solvent than in the bulk, the PMF after the conjugate permeation (at z = 125 Å) is ∼20.5 kcal/mol lower than the PMF of the conjugate dissociated from BtuB on the cell exterior (at z = −25 Å). Probably, binding to the highly mobile extended luminal domain is entropically favored.

Because in our model of transport, the position of the luminal domain was constrained, we cannot evaluate how its extension affects the PMF of vitamin B12-PNA permeation through BtuB. Additionally, we can only speculate about the full release of the conjugate from the BtuB luminal domain to the periplasm. We hypothesize that the conjugate release could be accelerated during refolding of the luminal domain after it disconnects from TonB. However, it is also possible that the conjugate “travels” on the extended luminal domain to interact with TonB and stays there until it is bound by a specific periplasmic binding protein. Such a transport pathway was previously suggested for vitamin B12 (85).

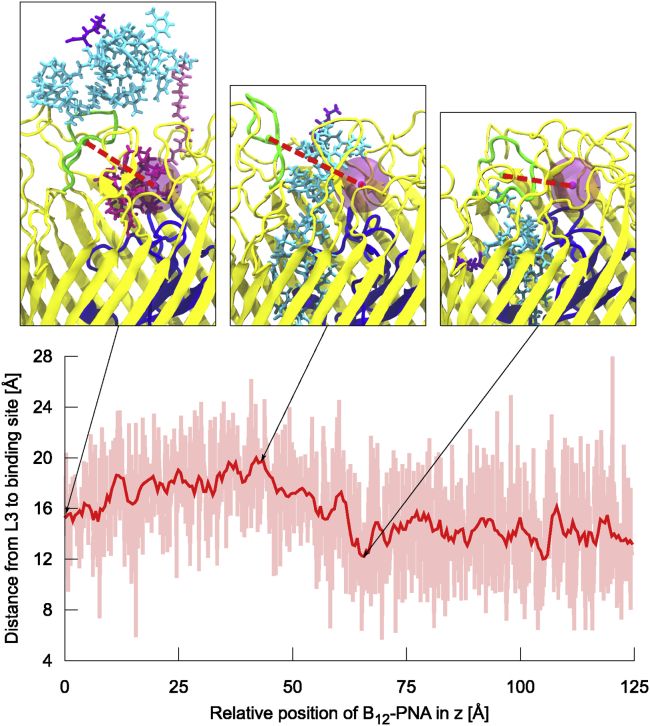

Mobility of extracellular loops of BtuB during transport of vitamin B12-PNA

To analyze the conformations of the BtuB extracellular loops during vitamin B12-PNA transport, we performed principal component (PC) analysis on combined GF-SA-US trajectories considering the Cα atoms of the BtuB barrel. We found that the principal components with the largest variance (PC1–PC3) correspond to the opening and closing motions of BtuB, with loops L3, L2, and L8 showing the largest mobility (Video S4). To assess the contributions of each loop to these motions, we measured the distances between the COMs of the loops and vitamin B12 binding site (Fig. S17). For loops L2 and L8, this distance fluctuates up to ∼6 Å, but its magnitude is on average similar throughout the whole vitamin B12-PNA transport route. On the contrary, loop L3 is not only highly mobile, but its conformation depends on the transport phase (Fig. 8). At the beginning of permeation (at z = 0 Å), loop L3 interacts mainly with vitamin B12 and is moderately distant from the binding site (∼16 Å). Afterwards, as vitamin B12-(CH2)12-PNA passes through BtuB, loop L3 protrudes outside the vitamin B12 binding site more often, and the average distance of L3 to the binding site increases to ∼19.5 Å (at z = 42 Å). This is associated with steric hindrance in the vitamin B12 binding site caused by the migrating PNA moiety. When the conjugate moves further toward the periplasm, until z of ∼65 Å, L3 moves closer to the vitamin B12 binding site area (on average up to 13.5 Å). Next, the loop L3 makes last contacts with the PNA C-terminus. After full permeation of the conjugate through BtuB, L3 maintains its proximity to the binding site because it interacts with the luminal domain. This agrees with our previous observations (31) that the BtuB barrel encloses upon the transport of vitamin B12, thus precluding the return of the ligand to the external environment and the entrance of undesirable species into the cell.

Figure 8.

The median and lower-upper extremes range of the distance from loop L3 (green) to vitamin B12 binding site (magenta sphere) during transport of vitamin B12-(CH2)12-PNA conjugate through BtuB. To see this figure in color, go online.

Conclusions

By combining microbiological and fluorescence assays, we have proven that the transport of vitamin B12-PNA conjugates in E. coli K-12 occurs through the outer-membrane protein BtuB, the same route as naturally taken by free vitamin B12. We also provided the mechanism of permeation of the B12-(CH2)12-PNA conjugate through BtuB employing all-atom molecular dynamics simulations. We applied GF-SA to enhance sampling of the BtuB extracellular loops and PNA along the transport pathway. The GF-SA approach, coupled with US, provided the PMF of the conjugate passage through BtuB. We found that upon partial unfolding of the BtuB luminal domain, the transfer of the conjugate into the BtuB interior is energetically favorable. While inside BtuB, the PNA oligomer unfolds, enabling interactions with the BtuB protein, especially with its luminal domain, and loops L3 and L8. The majority of PNA contacts are formed by its nucleobases, which reduces their exposure to water. The energy barrier on the release path is ∼11.5 kcal/mol, which signifies that the removal of the B12-(CH2)12-PNA conjugate from the BtuB barrel occurs on the microsecond timescale. However, the energy required for the conjugate to dissociate back to the external environment of the cell is ∼29 kcal/mol, which implies that the transport of vitamin B12-PNA through BtuB is unidirectional, toward the periplasm. This is because after leaving the BtuB barrel to the periplasm, the partially refolded conjugate remains bound to the extended luminal domain. We hypothesize that full dissociation of the conjugate from BtuB could be enhanced during refolding of the luminal domain, after its separation from TonB. Furthermore, we demonstrated that BtuB extracellular loops, especially L3, adapt their conformation to efficiently bind large PNA, which corroborates the induced-fit mechanism suggested for binding and permeation of vitamin B12 through BtuB (31). Finally, we propose that BtuB may be used to deliver other compounds, covalently coupled with vitamin B12 through the outer membrane of E. coli. Because the extracellular loops and luminal domain that interact with the ligand during transport are rich in amino acids with hydrophobic or polar uncharged side chains, we anticipate that lipophilic species could be preferentially transported through BtuB. Indeed, we have previously found that the transport of charged vitamin B12-2′O-methyl RNA conjugates to E. coli is less effective than that of the hydrophobic vitamin B12-PNA (18), although still possible. In the future, we plan to extend our research to the inner membrane of E. coli to obtain a complete picture of the transport of the B12-PNA conjugates through the E. coli cell wall.

Author contributions

T.P. and J.T. designed research. T.P. performed and analyzed all simulations and contributed analytic tools. J.C. and M.R. prepared the mutant strain. M.R. performed fluorescence experiments. A.J.W. synthesized the functionalized vitamin B12 derivatives. M.W. synthesized PNA oligomers and conjugated them with vitamin B12 derivatives. T.P. wrote the initial manuscript draft with the help of J.C., M.R., and J.T. T.P., D.G., D.B., and J.T. edited the manuscript. J.T., D.G., and D.B. supervised research and provided resources.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge funding from the National Science Centre, Poland (grants UMO-2014/12/W/ST5/00589 and UMO-2017/27/N/NZ1/00986). Simulations were performed at the Centre of New Technologies and Interdisciplinary Centre for Mathematical and Computational Modelling (GA65-16, GA73-21) of the University of Warsaw and the San Diego Supercomputer Center.

Editor: Alemayehu Gorfe.

Footnotes

Supporting Material can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2021.01.004.

Contributor Information

Tomasz Pieńko, Email: t.pienko@cent.uw.edu.pl.

Joanna Trylska, Email: joanna@cent.uw.edu.pl.

Supporting material

References

- 1.Exner M., Bhattacharya S., Trautmann M. Antibiotic resistance: what is so special about multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria? GMS Hyg. Infect. Control. 2017;12:Doc05. doi: 10.3205/dgkh000290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rasmussen L.C.V., Sperling-Petersen H.U., Mortensen K.K. Hitting bacteria at the heart of the central dogma: sequence-specific inhibition. Microb. Cell Fact. 2007;6:24. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-6-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trylska J., Thoduka S.G., Dąbrowska Z. Using sequence-specific oligonucleotides to inhibit bacterial rRNA. ACS Chem. Biol. 2013;8:1101–1109. doi: 10.1021/cb400163t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xue X.Y., Mao X.G., Luo X.X. Advances in the delivery of antisense oligonucleotides for combating bacterial infectious diseases. Nanomedicine (Lond.) 2018;14:745–758. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2017.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nielsen P.E., Egholm M., Buchardt O. Peptide nucleic acid (PNA). A DNA mimic with a peptide backbone. Bioconjug. Chem. 1994;5:3–7. doi: 10.1021/bc00025a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tomac S., Sarkar M., Gräslund A. Ionic effects on the stability and conformation of peptide nucleic acid complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:5544–5552. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Good L., Sandberg R., Wahlestedt C. Antisense PNA effects in Escherichia coli are limited by the outer-membrane LPS layer. Microbiology (Reading) 2000;146:2665–2670. doi: 10.1099/00221287-146-10-2665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wojciechowska M., Równicki M., Trylska J. Antibacterial peptide nucleic acids - facts and perspectives. Molecules. 2020;25:559. doi: 10.3390/molecules25030559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Good L., Awasthi S.K., Nielsen P.E. Bactericidal antisense effects of peptide-PNA conjugates. Nat. Biotechnol. 2001;19:360–364. doi: 10.1038/86753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vaara M., Porro M. Group of peptides that act synergistically with hydrophobic antibiotics against gram-negative enteric bacteria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1996;40:1801–1805. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.8.1801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bendifallah N., Rasmussen F.W., Koppelhus U. Evaluation of cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs) as vehicles for intracellular delivery of antisense peptide nucleic acid (PNA) Bioconjug. Chem. 2006;17:750–758. doi: 10.1021/bc050283q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nekhotiaeva N., Awasthi S.K., Good L. Inhibition of Staphylococcus aureus gene expression and growth using antisense peptide nucleic acids. Mol. Ther. 2004;10:652–659. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rebuffat A.G., Nawrocki A.R., Frey F.J. Gene delivery by a steroid-peptide nucleic acid conjugate. FASEB J. 2002;16:1426–1428. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0706fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Penichet M.L., Kang Y.S., Shin S.U. An antibody-avidin fusion protein specific for the transferrin receptor serves as a delivery vehicle for effective brain targeting: initial applications in anti-HIV antisense drug delivery to the brain. J. Immunol. 1999;163:4421–4426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kauss T., Arpin C., Barthélémy P. Lipid oligonucleotides as a new strategy for tackling the antibiotic resistance. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:1054. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-58047-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Równicki M., Wojciechowska M., Trylska J. Vitamin B12 as a carrier of peptide nucleic acid (PNA) into bacterial cells. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:7644. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-08032-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wierzba A.J., Maximova K., Gryko D. Does a conjugation site affect transport of vitamin B12 -peptide nucleic acid conjugates into bacterial cells? Chemistry. 2018;24:18772–18778. doi: 10.1002/chem.201804304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giedyk M., Jackowska A., Gryko D. Vitamin B12 transports modified RNA into E. coli and S. Typhimurium cells. Chem. Commun. (Camb.) 2019;55:763–766. doi: 10.1039/c8cc05064c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Równicki M., Da̧browska Z., Trylska J. Inhibition of Escherichia coli growth by vitamin B12–peptide nucleic acid conjugates. ACS Omega. 2019;4:819–824. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Di Girolamo P.M., Bradbeer C. Transport of vitamin B12 in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1971;106:745–750. doi: 10.1128/jb.106.3.745-750.1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.White J.C., DiGirolamo P.M., Bradbeer C. Transport of vitamin B 12 in Escherichia coli. Location and properties of the initial B12 -binding site. J. Biol. Chem. 1973;248:3978–3986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cadieux N., Bradbeer C., Kadner R.J. Identification of the periplasmic cobalamin-binding protein BtuF of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 2002;184:706–717. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.3.706-717.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DeVeaux L.C., Kadner R.J. Transport of vitamin B12 in Escherichia coli: cloning of the btuCD region. J. Bacteriol. 1985;162:888–896. doi: 10.1128/jb.162.3.888-896.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schauer K., Rodionov D.A., de Reuse H. New substrates for TonB-dependent transport: do we only see the ‘tip of the iceberg’? Trends Biochem. Sci. 2008;33:330–338. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2008.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Noinaj N., Guillier M., Buchanan S.K. TonB-dependent transporters: regulation, structure, and function. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2010;64:43–60. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.112408.134247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cascales E., Buchanan S.K., Cavard D. Colicin biology. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2007;71:158–229. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00036-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rabsch W., Ma L., Klebba P.E. FepA- and TonB-dependent bacteriophage H8: receptor binding and genomic sequence. J. Bacteriol. 2007;189:5658–5674. doi: 10.1128/JB.00437-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Braun V., Pramanik A., Bohn E. Sideromycins: tools and antibiotics. Biometals. 2009;22:3–13. doi: 10.1007/s10534-008-9199-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chimento D.P., Mohanty A.K., Wiener M.C. Substrate-induced transmembrane signaling in the cobalamin transporter BtuB. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2003;10:394–401. doi: 10.1038/nsb914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shultis D.D., Purdy M.D., Wiener M.C. Outer membrane active transport: structure of the BtuB:TonB complex. Science. 2006;312:1396–1399. doi: 10.1126/science.1127694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pieńko T., Trylska J. Extracellular loops of BtuB facilitate transport of vitamin B12 through the outer membrane of E. coli. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2020;16:e1008024. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1008024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chimento D.P., Kadner R.J., Wiener M.C. Comparative structural analysis of TonB-dependent outer membrane transporters: implications for the transport cycle. Proteins. 2005;59:240–251. doi: 10.1002/prot.20416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fanucci G.E., Cadieux N., Cafiso D.S. Competing ligands stabilize alternate conformations of the energy coupling motif of a TonB-dependent outer membrane transporter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:11382–11387. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1932486100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lukasik S.M., Ho K.W., Cafiso D.S. Molecular basis for substrate-dependent transmembrane signaling in an outer-membrane transporter. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;370:807–811. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Freed D.M., Horanyi P.S., Cafiso D.S. Conformational exchange in a membrane transport protein is altered in protein crystals. Biophys. J. 2010;99:1604–1610. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.06.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu Q., Ellena J.F., Cafiso D.S. Substrate-dependent unfolding of the energy coupling motif of a membrane transport protein determined by double electron-electron resonance. Biochemistry. 2006;45:10847–10854. doi: 10.1021/bi061051x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Köhler S.D., Weber A., Drescher M. The proline-rich domain of TonB possesses an extended polyproline II-like conformation of sufficient length to span the periplasm of Gram-negative bacteria. Protein Sci. 2010;19:625–630. doi: 10.1002/pro.345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Braun V., Gaisser S., Traub I. Energy-coupled transport across the outer membrane of Escherichia coli: ExbB binds ExbD and TonB in vitro, and leucine 132 in the periplasmic region and aspartate 25 in the transmembrane region are important for ExbD activity. J. Bacteriol. 1996;178:2836–2845. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.10.2836-2845.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ollis A.A., Manning M., Postle K. Cytoplasmic membrane proton motive force energizes periplasmic interactions between ExbD and TonB. Mol. Microbiol. 2009;73:466–481. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06785.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hickman S.J., Cooper R.E.M., Brockwell D.J. Gating of TonB-dependent transporters by substrate-specific forced remodelling. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:14804. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gumbart J., Wiener M.C., Tajkhorshid E. Mechanics of force propagation in TonB-dependent outer membrane transport. Biophys. J. 2007;93:496–504. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.104158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chromiński M., Gryko D. “Clickable” vitamin B12 derivative. Chemistry. 2013;19:5141–5148. doi: 10.1002/chem.201203899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wojciechowska M., Ruczyński J., Bluijssen H. Synthesis and hybridization studies of a new CPP-PNA conjugate as a potential therapeutic agent in atherosclerosis treatment. Protein Pept. Lett. 2014;21:672–678. doi: 10.2174/0929866521666140320102034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yamamoto N., Nakahigashi K., Mori H. Update on the Keio collection of Escherichia coli single-gene deletion mutants. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2009;5:335. doi: 10.1038/msb.2009.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pósfai G., Kolisnychenko V., Blattner F.R. Markerless gene replacement in Escherichia coli stimulated by a double-strand break in the chromosome. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:4409–4415. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.22.4409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gibson D.G., Young L., Smith H.O. Enzymatic assembly of DNA molecules up to several hundred kilobases. Nat. Methods. 2009;6:343–345. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kovach M.E., Elzer P.H., Peterson K.M. Four new derivatives of the broad-host-range cloning vector pBBR1MCS, carrying different antibiotic-resistance cassettes. Gene. 1995;166:175–176. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00584-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Philippe N., Alcaraz J.P., Schneider D. Improvement of pCVD442, a suicide plasmid for gene allele exchange in bacteria. Plasmid. 2004;51:246–255. doi: 10.1016/j.plasmid.2004.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ogata H., Goto S., Kanehisa M. KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:29–34. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.1.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Demarre G., Guérout A.M., Mazel D. A new family of mobilizable suicide plasmids based on broad host range R388 plasmid (IncW) and RP4 plasmid (IncPalpha) conjugative machineries and their cognate Escherichia coli host strains. Res. Microbiol. 2005;156:245–255. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.del Campo I., Ruiz R., de la Cruz F. Determination of conjugation rates on solid surfaces. Plasmid. 2012;67:174–182. doi: 10.1016/j.plasmid.2012.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhou K., Zhou L., Too H.P. Novel reference genes for quantifying transcriptional responses of Escherichia coli to protein overexpression by quantitative PCR. BMC Mol. Biol. 2011;12:18. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-12-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kushner S.R. An improved method for transformation of E. coli with ColE1 derived plasmids. In: Boyer H.B., Nicosia S., editors. Genetic Engineering. Elsevier; 1978. pp. 17–23. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wiegand I., Hilpert K., Hancock R.E. Agar and broth dilution methods to determine the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) of antimicrobial substances. Nat. Protoc. 2008;3:163–175. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lomize M.A., Lomize A.L., Mosberg H.I. OPM: orientations of proteins in membranes database. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:623–625. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btk023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dolinsky T.J., Nielsen J.E., Baker N.A. PDB2PQR: an automated pipeline for the setup of Poisson-Boltzmann electrostatics calculations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:W665–W667. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang L.P., McKiernan K.A., Pande V.S. Building a more predictive protein force field: a systematic and reproducible route to AMBER-FB15. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2017;121:4023–4039. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.7b02320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jasiński M., Feig M., Trylska J. Improved force fields for peptide nucleic acids with optimized backbone torsion parameters. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2018;14:3603–3620. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.8b00291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shields G.C., Laughton C.A., Orozco M. Molecular dynamics simulation of a PNA⋅DNA⋅PNA triple helix in aqueous solution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:5895–5904. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Marques H.M., Ngoma B., Brown K.L. Parameters for the AMBER force field for the molecular mechanics modeling of the cobalt corrinoids. J. Mol. Struct. 2001;561:71–91. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bayly C.I., Cieplak P., Kollman P.A. A well-behaved electrostatic potential based method using charge restraints for deriving atomic charges: the RESP model. J. Phys. Chem. 1993;97:10269–10280. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Frisch M.J., Trucks G.W., Fox D.J. Gaussian Inc.; Wallingford, CT: 2009. Gaussian 09; Revision E.01. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sommer B., Dingersen T., Dietz K.J. CELLmicrocosmos 2.2 MembraneEditor: a modular interactive shape-based software approach to solve heterogeneous membrane packing problems. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2011;51:1165–1182. doi: 10.1021/ci1003619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pandit K.R., Klauda J.B. Membrane models of E. coli containing cyclic moieties in the aliphatic lipid chain. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2012;1818:1205–1210. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2012.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gould, I., A. Skjevik, …, R. Walker. 2018. Lipid17: a comprehensive AMBER force field for the simulation of zwitterionic and anionic lipids.

- 66.Kirschner K.N., Yongye A.B., Woods R.J. GLYCAM06: a generalizable biomolecular force field. Carbohydrates. J. Comput. Chem. 2008;29:622–655. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Snyder S., Kim D., McIntosh T.J. Lipopolysaccharide bilayer structure: effect of chemotype, core mutations, divalent cations, and temperature. Biochemistry. 1999;38:10758–10767. doi: 10.1021/bi990867d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Case D.A., Darden T.A., Kollman P.A. University of California; San Francisco, CA: 2016. AMBER 16. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Humphrey W., Dalke A., Schulten K. VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 1996;14:33–38, 27–28.. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wang L.P., Martinez T.J., Pande V.S. Building force fields: an automatic, systematic, and reproducible approach. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2014;5:1885–1891. doi: 10.1021/jz500737m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Joung I.S., Cheatham T.E., III Determination of alkali and halide monovalent ion parameters for use in explicitly solvated biomolecular simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2008;112:9020–9041. doi: 10.1021/jp8001614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Li P., Merz K.M., Jr. Taking into account the ion-induced dipole interaction in the nonbonded model of ions. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2014;10:289–297. doi: 10.1021/ct400751u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Phillips J.C., Braun R., Schulten K. Scalable molecular dynamics with NAMD. J. Comput. Chem. 2005;26:1781–1802. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Andersen C.H. RATTLE: a “Velocity” version of the SHAKE algorithm for molecular dynamics calculations. J. Comput. Phys. 1983;52:24–34. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Miyamoto S., Kollman P.A. Settle: an analytical version of the SHAKE and RATTLE algorithm for rigid water models. J. Comput. Chem. 1992;13:952–962. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Leech J., Prins J.F., Hermans J. SMD: visual steering of molecular dynamics for protein design. IEEE Comput. Sci. Eng. 1996;3:38–45. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Izrailev S., Stepaniants S., Schulten K. Molecular dynamics study of unbinding of the avidin-biotin complex. Biophys. J. 1997;72:1568–1581. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78804-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Fiorin G., Klein M.L., Hénin J. Using collective variables to drive molecular dynamics simulations. Mol. Phys. 2013;111:3345–3362. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Torrie G.M., Valleau J.P. Nonphysical sampling distributions in Monte Carlo free-energy estimation: umbrella sampling. J. Comput. Phys. 1977;23:187–199. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kumar S., Rosenberg J., Kollman P. Multidimensional free-energy calculations using the weighted histogram analysis method. J. Comput. Chem. 1995;16:1339–1350. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Roux B. The calculation of the potential of mean force using computer simulations. Comput. Phys. Commun. 1995;91:275–282. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Grossfield A. WHAM: an implementation of the weighted histogram analysis method. http://membrane.urmc.rochester.edu/content/wham/

- 83.Doublet P., van Heijenoort J., Mengin-Lecreulx D. The murI gene of Escherichia coli is an essential gene that encodes a glutamate racemase activity. J. Bacteriol. 1993;175:2970–2979. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.10.2970-2979.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Pieńko T., Wierzba A.J., Trylska J. Conformational dynamics of cyanocobalamin and its conjugates with peptide nucleic acids. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2017;121:2968–2979. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.7b00649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.James K.J., Hancock M.A., Coulton J.W. TonB interacts with BtuF, the Escherichia coli periplasmic binding protein for cyanocobalamin. Biochemistry. 2009;48:9212–9220. doi: 10.1021/bi900722p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.