Conspectus:

Immunotherapies harness an individual’s immune system to battle diseases such as cancer and autoimmunity. During cancer the immune system often fails to detect and destroy cancerous cells, whereas during autoimmune disease, the immune system mistakenly attacks self-tissue. Immunotherapies can help guide more effective responses in these settings, as evidenced by recent advances with monoclonal antibodies and adoptive cell therapies. However, despite the transformative gains of immunotherapies for patients, many therapies are not curative, work only for a small subset of patients, and lack specificity in distinguishing between healthy and diseased cells, which can cause severe side effects. From this perspective, self-assembled biomaterials are promising technologies that could help address some of the limitations facing immunotherapies. For example, self-assembly allows precision control over the combination and relative concentration of immune cues, and directed cargo display densities. These capabilities support selectivity and potency that could decrease off-target effects and enable modular or personalized immunotherapies. The underlying forces driving self-assembly of most systems in aqueous solution result from hydrophobic interactions or charge polarity. In this Account, we highlight how these forces are being used to self-assemble immunotherapies for cancer and autoimmune disease.

Hydrophobic interactions can create a range of intricate structures, including peptide nanofibers, nanogels, micelle-like particles, and in vivo assemblies with protein carriers. Certain nanofibers with hydrophobic domains uniquely benefit from the ability to elicit immune responses without additional stimulatory signals. This feature can reduce non-specific inflammation but may also limit the nanofiber’s application because of their inherent stimulatory properties. Micelle-like particles have been developed with the ability to incorporate a range of tumor-specific antigens for immunotherapies in mouse models of cancer. Key observations have revealed that both the total dose of antigen and display density of antigen per particle can impact immune response and efficacy of immunotherapies. These developments are promising benchmarks that could reveal design principles for engineering more specific and personalized immunotherapies.

There has also been extensive work to develop platforms using electrostatic interactions to drive assembly of oppositely charged immune signals. These strategies benefit from the ability to tune biophysical interactions between components by altering the ratio of cationic to anionic charge during formulation, or the density of charge. Using a layer-by-layer assembly method, our lab developed hollow capsules composed entirely of immune signals for therapies in cancer and autoimmune disease models. This platform allowed for 100% of the immunotherapy to be composed of immune signals and completely prevents onset of disease in a mouse model of multiple sclerosis. Layer-by-layer assembly has also been used to coat microneedle patches to target signals to immune cells in the dermal layer. Alternative to layer-by-layer assembly, one step assembly can be achieved by mixing cationic and anionic components in solution. Additional approaches have created molecular structures that leverage hydrogen bonding for self-assembly. The creativity of engineered self-assembly has led to key insights that could benefit future immunotherapies and revealed aspects that require further study. The challenge now remains to utilize these insights to push development of new immunotherapeutics into clinical settings.

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

i). Immunotherapies promote immune responses to fight cancer and autoimmune disease

Immunotherapies harness an individual’s immune system to better fight disease. When treating cancer, immunotherapies attempt to boost immune response to destroy cancer cells that otherwise evade and suppress the immune system. Conversely, during autoimmune disease – where the immune system mistakenly attacks one’s own tissues – immunotherapies seek to suppress inflammatory responses to prevent dysfunctional attacks against the body. As this Account highlights, self-assembly technologies create many exciting opportunities to control how immune signals are presented and encountered to drive effective therapeutic responses in both cancer and autoimmunity.

Antigen presenting cells (APCs), such as dendritic cells (DCs) and macrophages, survey our tissues, constantly clearing the body of cellular debris and engulfing foreign substances. During this activity, APCs process and present molecular fragments of engulfed material – termed antigens – on their surface to activate the highly-specific “adaptive” arm of the immune system. Concurrently, cells in our body present self-antigens from their own internal machinery to ensure the immune system can distinguish between host cells and foreign pathogens. After APCs encounter foreign antigen, they migrate to secondary lymphoid tissues, such as lymph nodes, to present antigens to T and B lymphocytes. Activation of T and B cells typically requires three signals. The first is recognition of an antigen that matches the specificity of the T or B cell; this is the “cognate” antigen. The second signal is recognition of costimulatory molecules APCs present to lymphocytes along with the cognate antigen. The third is secreted proteins called cytokines that direct polarization of lymphocytes towards specific functional phenotypes. If a T cell binds its cognate antigen in the presence of costimulatory signals, the T cell activates, proliferates, and migrates to the periphery in search of cells or pathogens expressing the cognate antigen. CD4 T cells adopt helper phenotypes that shape adaptive immune responses by secreting cytokines that influence immune clearance mechanisms. CD8 T cells become cytotoxic T cells that directly kill cells expressing the cognate antigen. Activated B cells produce antibodies that bind to cells or pathogens expressing cognate antigen, which neutralizes the target and tags it for clearance. If APCs present antigen without the appropriate costimulatory signals, as in the case of self-antigens originating from host cells, lymphocytes can be rendered inactive against cognate antigen or adopt regulatory phenotypes that maintain tolerance and prevent attack of host cells expressing those antigens.

During cancer the immune system often fails to generate effective anti-tumor responses because many of the antigens on tumors are indistinguishable from those on healthy host cells. Additionally, cancer cells actively suppress the immune system by overexpressing molecules such as PD-1 and CTLA-4, which are natural suppressors the immune system normally used to restrain immune function. Important clinical strategies include monoclonal antibodies,5 such as rituximab which targets B cells in certain types of cancers, and more recently, the exciting development of checkpoint inhibitor antibodies.6 For example, anti-PD-1 and anti-CTLA-4 antibodies unleash the stimulatory immune pathways that tumors normally block. Likewise, in autoimmune disease, new immunotherapies are leveraging molecularly specific targeting, providing new benefits relative to existing suppressive options that can leave patients immunocompromised. One new monoclonal antibody, ocrelizumab, is the first FDA approved drug for the progressive form of multiple sclerosis (MS), an autoimmune disease in which the central nervous system is attacked. Despite the transformative gains these breakthroughs have provided for patients, a limitation of immunotherapies for both cancer and autoimmune disease continues to be lack of specificity in targeting or in the specificity of the resulting immune response. For example, monoclonal antibodies do not distinguish between the target markers expressed on healthy cells and diseased cells, such as those that attack self-tissue during autoimmunity. Likewise, immunotherapies that stimulate immunity create risk of uncontrolled immunotoxicity that can drive severe – sometimes fatal – side effects.

ii). Self-assembly technologies offer unique benefits to improve immunotherapies

Biomaterials have emerged as promising technologies to overcome some of the limitations of immunotherapy highlighted above.7–9 Biomaterials allow for co-delivery of multiple immune signals in particulate form, which can improve uptake and potency of the signals.1,10,11 This capability enables the programming of immune responses against specific antigens, thereby limiting non-specific effects that may occur from targeting of broad populations of cells or tissue. This can be achieved by delivering antigen to APCs along with a modulatory signal that directs processing of antigen towards inflammatory or regulatory mechanisms. However, biomaterials also introduce additional challenges into the clinical translation process. Material formulations are often hindered by inefficient cargo loading or heterogenous distributions in size or other biophysical properties. Further, inclusion of polymer carriers or heterogenous mixtures can complicate characterization and assessment of safety required for clinical trials and FDA approval.12

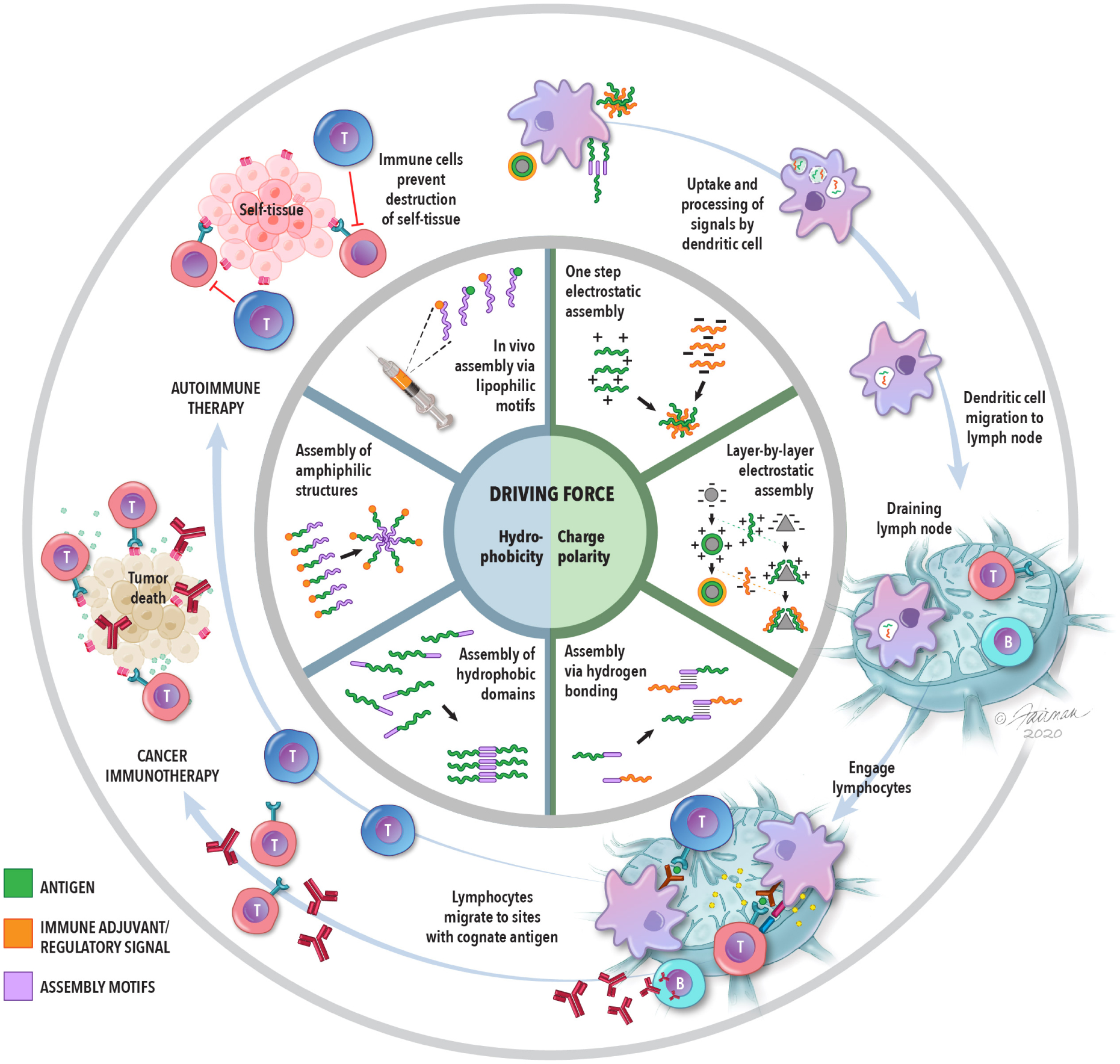

Self-assembling materials are a class of biomaterials that spontaneously assemble in aqueous solution to create entropically favorable structures.13 In light of the challenges just mentioned, self-assembling materials offer the same benefits of biomaterials, as well as the potential to overcome some of the complexity and formulation limitations described. Self-assembled materials require little to no additional energy input due to the spontaneous nature of assembly, allowing for facile, low-energy manufacturing methods that are scalable. Further, the precise structures and interactions that govern self-assembly reduce heterogeneity, complications in characterization, and loading inconsistencies. Self-assembled materials generally assemble owing to two underlying driving forces: hydrophobic interactions and/or charge polarity (Fig. 1). Hydrophobic interactions drive assembly of molecules into entropically favorable states, with hydrophobic regions “hidden” from the surrounding aqueous environment. Charge polarity drives electrostatic adsorption of oppositely charged components, creates a countervailing force that prevents assembly between like-charged components, and allows for hydrogen bonding to occur between polar molecules. In this Account, we highlight how these driving forces have been utilized to develop self-assembly approaches for candidate immunotherapies for cancer and autoimmune disease and to gain insights that could improve the effectiveness and translatability of future immunotherapies.

Figure 1.

The inner-most circle highlights the two main driving forces of self-assembled immunotherapies. The middle circle identifies the general strategies that utilized these forces to create self-assembled structures. The outer-most circle illustrates the general strategy of immunotherapies for cancer and autoimmune disease, as described in the introduction and throughout this Account. Self-assembled materials are being explored in all of the stages depicted in the outer-most ring.

2. Hydrophobic interactions promote self-assembly of biomaterials into entropically-favorable states

i). Biomaterials can be designed for self-assembly with hydrophobic domains

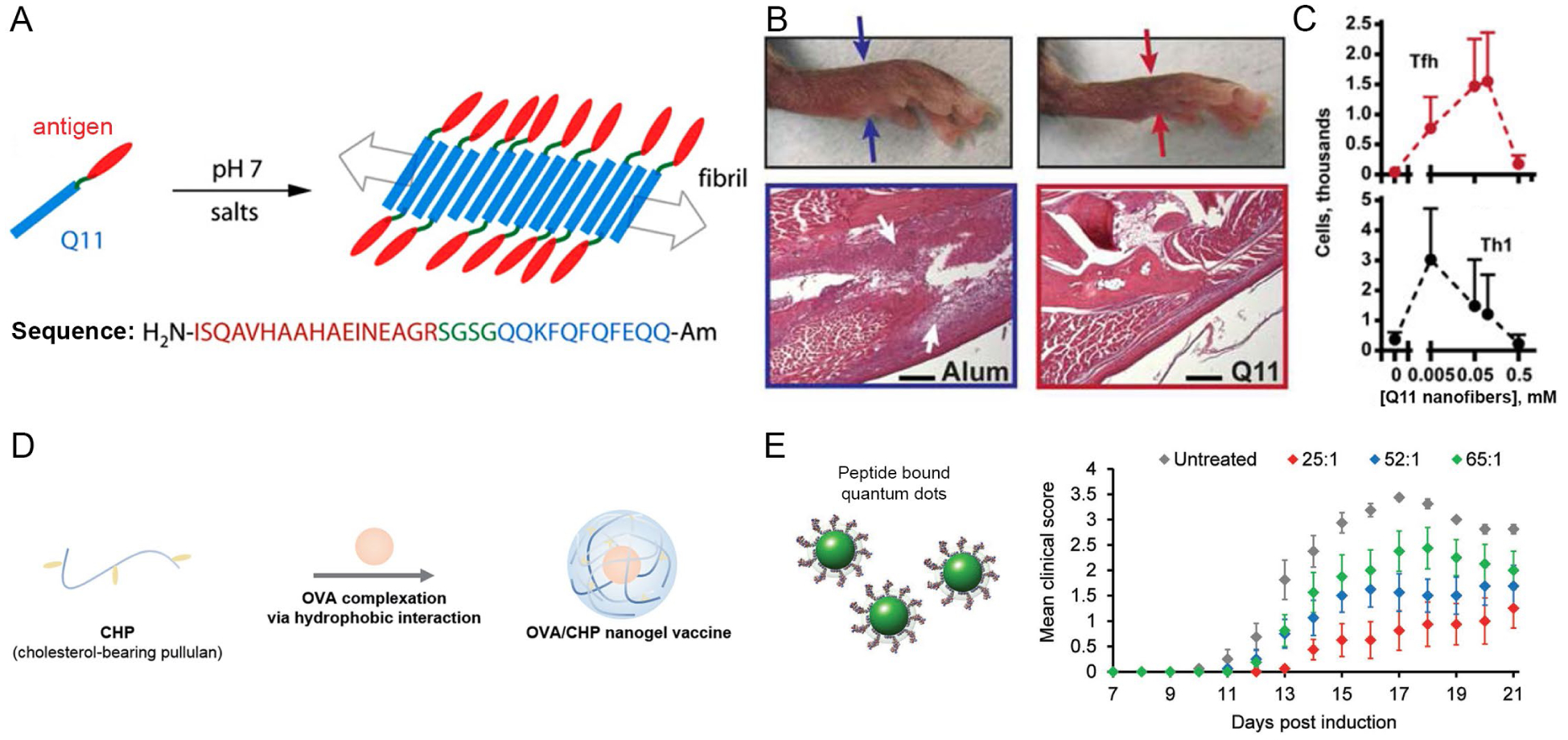

One method of driving self-assembly is conjugating biomaterials with hydrophobic motifs. For example, the Collier lab developed the peptide Q11 to spontaneously assemble into β-sheet nanofibers.14 The assembly is driven by the peptide’s alternating hydrophobic/hydrophilic primary structure, with all hydrophobic residues positioned on one face of the β-sheet and all hydrophilic residues positioned on the other face (Fig. 2A). Several research efforts have tested Q11’s ability to assemble and deliver antigens to APCs to enhance immune responses.15–21 These self-assembled structures induced robust antibody responses to the antigen without any additional adjuvants. Adjuvants are stimulatory signals often included in vaccines and immunotherapies to stimulate responses against an antigen of interest. The ability to induce an immune response without addition of adjuvant is an intriguing property that could potentially simplify formulations and limit undesired inflammation caused by off-target effects. This benefit was highlighted in studies where vaccination of mice with peptide nanofibers did not cause swelling (Fig. 2B) or accumulation of immune cells and inflammatory cytokines at injection sites, a common side effect with many adjuvants.18 Additionally, the nanofibers selectively activated DCs, but not macrophages, even though both cell types were able to engulf the nanofibers.18 The selective activation could be a useful property for directing specific immune responses, which may be more difficult with conventional adjuvants that are broadly stimulatory. Despite the lack of inflammation, the nanofibers were able to activate antigen-specific CD8 T cells, which are important in anti-tumor immune responses.20 This platform could also be tuned to generate a particular type of immune response depending on the dose of antigen that was incorporated into the nanofibers. In particular, the dose of antigen that maximized T cell responses important in activating B cells (Tfh) was nearly a magnitude higher than the dose that maximized helper T cells (Th1) that secrete inflammatory cytokines (Fig. 2C).19 Fibers that formed either α-helical structures or β-sheets both produced antibody responses.22,23 However, APCs internalized and presented antigen when nanofibers were positively, but not negatively, charged.21

Figure 2.

A) Q11 nanofibers conjugated with antigen. B) Reduced swelling in mouse footpads after treatment with Q11 nanofibers (right) compared to treatment containing adjuvant (left). Reproduced with permission from ref. 18. Copyright 2013 Elsevier. C) Dose of antigen impacted overall immune response. Adapted with permission from ref. 19. Copyright 2014 Wiley. D) Nanogels containing ovalbumin (OVA). Adapted with permission from ref. 25. Copyright 2020 The Royal Society of Chemistry. E) Therapeutic efficacy was altered as a function of antigen density per quantum dot. Adapted with permission from ref. 30. Copyright 2017 Wiley.

Hydrophobic motifs have also been used to create a variety of other self-assembled structures. Purwada et al. created self-assembling protein nanogels containing a polymer backbone with a functionalized hydrophobic pyridine side chain.24 In the presence of aqueous protein, entropic forces drove the self-assembly of the pyridine groups into an inner layer, while proteins in solution formed the outer layer. Another example from the Akiyoshi lab used cholesterol-bearing pullulan to create a self-assembling nanogel incorporating the common protein antigen ovalbumin (Fig. 2D).25 Treatment with nanogels alone or in combination with anti-PD1 antibodies significantly reduced tumor growth in a lymphoma mouse model that expresses ovalbumin, relative to treatment only with anti-PD1 or a combination of soluble ovalbumin and anti-PD1. Interestingly, when the nanogels were modified to increase anionic surface charge, these nanogels were distributed in different areas of lymph nodes compared to the distribution observed with unmodified nanogels, which were near-neutral.26 The anionic nanogels were internalized more effectively by several distinct subsets of DCs involved in activation of helper T cells and B cells.

The size, shape, and surface chemistry of immunotherapies can all impact biological responses.7,27 In the case of the Q11 nanofibers, the cationic charge may have facilitated adsorption with the anionic cell membrane and thus improved uptake via non-specific electrostatic interactions. Conversely, the anionic charge of the nanogels could have prevented the non-specific interactions with the cell membrane, resulting in uptake only by particular subsets of phagocytic cells. The ability to activate immune responses without additional adjuvants may also be impacted by biophysical properties. For example, immune responses can be activated through recognition of hydrophobic groups,28 which may contribute to the ability of Q11 nanofibers to generate immune response without explicit adjuvant molecules. However, another study using self-assembled peptide nanovesicles induced strong CD8 T cell responses and delayed tumor growth only when administered with an adjuvant.29 These nanovesicles might hide hydrophobic motifs in a core, thus preventing or reducing recognition by and activation of immune cells.

In addition to accessibility of molecular motifs in self-assembled materials, the density of immune signals displayed on constructs can also impact response during immunotherapy. Our lab has investigated this idea in the context of immunotherapies for MS.30 In our studies we self-assembled and displayed peptide self-antigens on quantum dots at defined densities. These particles slowed disease progression as a function of total antigen dose. Intriguingly, at fixed antigen dose, particles displaying a low density of antigen on a greater number of particles (e.g., 25:1) were more efficacious than particles displaying antigen at a high density on fewer particles (e.g., 65:1), indicated by lower mean clinical scores (Fig. 2E). Our discovery suggests that availability of more therapeutic “events” (i.e., particles) may be more effective in modulating the integrated signaling in immune response. This discovery is one example of a parameter that may allow rational design of selective immunotherapies for autoimmune disease as well as cancer.

ii). Chemically synthesized amphiphilic molecules form micelle-like particles

Hydrophobic interactions can also be used to self-assemble amphiphilic molecules into ordered phases, such as micelle-like structures.1,31,32 One important area where this idea has been used for immunotherapies is the design of peptide amphiphiles composed of a hydrophobic, lipid-like tail that is linked to a hydrophilic peptide headgroup.1 In aqueous conditions, the peptide amphiphiles self-assemble into micelles, burying the hydrophobic tails within the core while the hydrophilic headgroups are displayed on the surface.

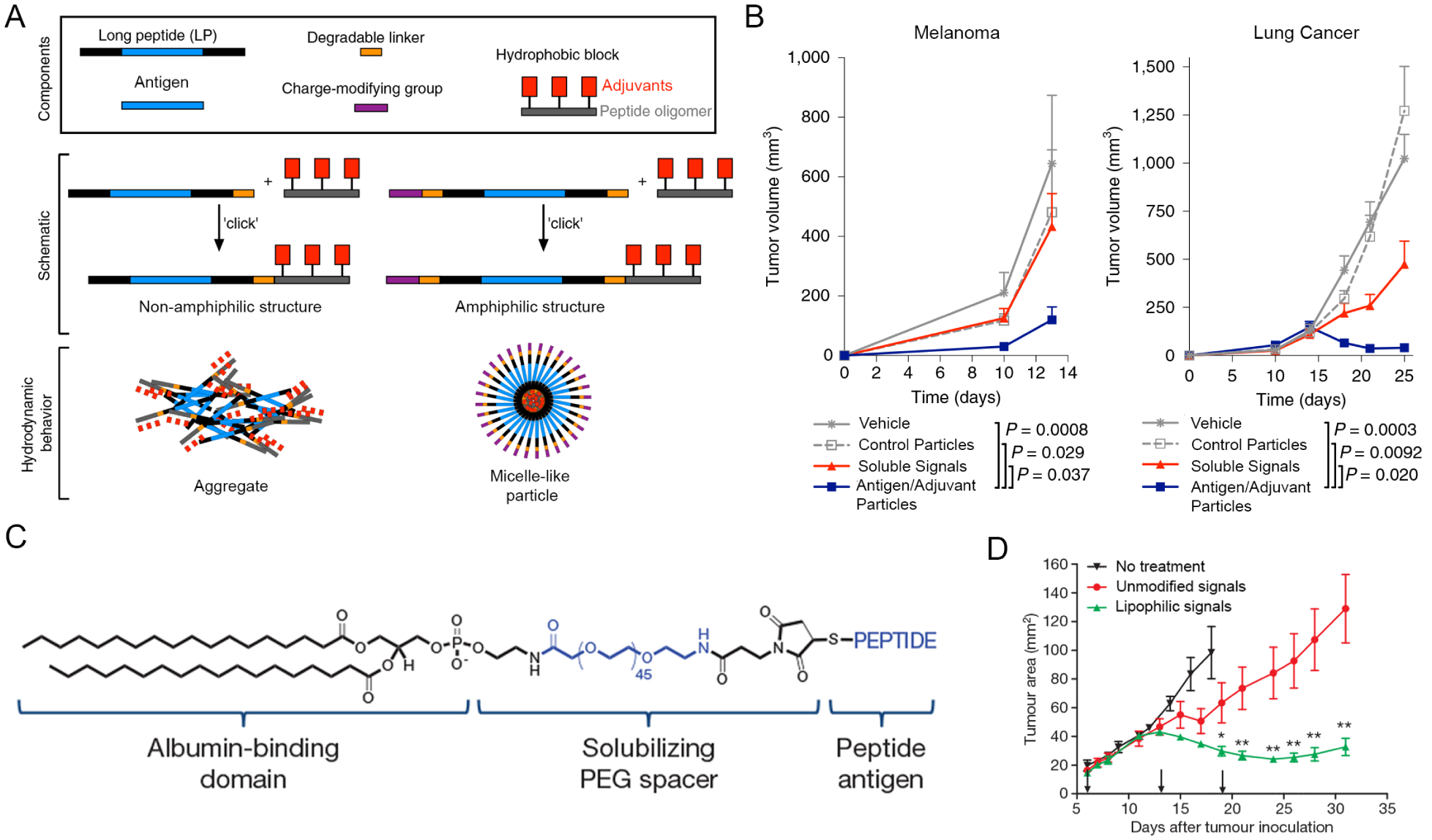

Toward a standardized platform for manufacturing personalized cancer therapies, the Seder lab recently developed antigen-adjuvant conjugates that self-assemble into micelle-like particles of uniform size, irrespective of the antigen sequence.1 The self-assembly was driven by charge-modified peptide sequences and hydrophobic oligopeptides that were anchored to the C and N termini via enzyme degradable linkers. The hydrophobic blocks were further linked to a defined number of small molecule adjuvants specifically selected based on their hydrophobic properties and ability to drive T cell response. Upon resuspension in aqueous solution, the hydrophobic components promoted assembly of micelle-like structures, while the charge modifying groups established uniform surface charge that provided a countervailing force to prevent formation of aggregates (Fig. 3A). The micelles could incorporate a range of different tumor-specific antigens and adjuvants without disturbing the integrity of the particles. Furthermore, the micelle platform improved loading of antigens compared to other commonly used biomaterials, such as poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) or liposomes, where loading varied between different antigens and can sometimes vary batch to batch. Micelles conferred markedly improved efficacy in mouse models of skin and lung cancer relative to administration of soluble antigen and adjuvant (Fig. 3B). Importantly, vaccination of non-human primates with micelles activated both CD4 and CD8 T cell responses, a promising indicator that this platform has potential for application in clinical settings.

Figure 3.

A) Micelle-like particles containing antigen and adjuvant. B) Reduction in tumor volume in two models of cancer after treatment with micelle-like particles (blue). A+B were adapted with permission from ref. 1. Copyright 2020 Springer Nature. C) Structure of lipophilic molecules. D) Reduction in tumor volume after treatment with lipophilic antigen and adjuvant. C+D were adapted with permission from ref. 33. Copyright 2014 Springer Nature.

The development of this micelle platform is exciting, representing a standardized formulation approach that successfully incorporates a range of antigen and adjuvants. The consistent assembly of particles irrespective of composition is important for overcoming downstream hurdles specific to manufacturing and regulatory characterization. From a clinical perspective, the ability to incorporate a range of tumor-specific antigens is also relevant in the area of personalized cancer therapies, which seek anti-cancer immune responses without side effects or alteration to healthy immune function. Combining such approaches with technologies to identify tumor-specific antigens could represent a new paradigm for cancer immunotherapy.

iii). Lipophilic motifs promote in vivo self-assembly with protein carriers

Hydrophobic interactions can be leveraged within the body to more efficiently target immunotherapies to lymph nodes, increasing their potency. One strategy draws on the ability of lipophilic moieties to self-assemble with protein carriers, such as albumin. Albumin is a natural transporter molecule that shuttles cargo in the body to lymph nodes. Liu et al. first discovered the promise of an “albumin hitchhiking” idea by modifying a stimulatory adjuvant and other antigens with lipophilic motifs (Fig. 3C).33 These signals drained more efficiently to lymph nodes and decreased systemic toxicity compared to unmodified components, which were not concentrated in lymph nodes. By investigating the fate of these lipophilic structures, the authors discovered that lymph node resident DCs must cleave the bond between peptide and amphiphile before presenting the antigen to T cells. Because of improved lymph node targeting and subsequent presentation, T cells specific for the antigen were proliferated and inflammatory cues increased. When mice bearing skin or metastatic lung cancers were vaccinated with these immunotherapies, survival was significantly improved (Fig. 3D). Zhu et al. built on this idea using Evan’s blue, a clinical lymphatic tracer dye, as an albumin-binding domain due to its established safety profile.34 A lipophilic construct was created by conjugating the dye with an adjuvant. Co-delivery of this construct with a model antigen to mice resulted in a four-fold increase of antigen-specific CD8 T cells relative to an oil-in-water emulsion of antigen, which is a current benchmark for vaccination in these pre-clinical studies.

Building off their prior work, Appelbe et al. combined albumin-complexed adjuvant with radiation to improve cancer immunotherapy.35 In healthy vasculature, albumin is too large to drain out of blood vessels and instead is selectively processed through lymphatics.34 However, when a tumor is irradiated, the vasculature becomes more permeable. With this increased permeability, lipophilic adjuvant delivered intravenously binds to albumin and accumulates in tumors. The authors showed that this targeted accumulation increased inflammatory responses in the tumor environment and reduced systemic toxicity. This body of work suggests potential for in-vivo assembly of hydrophobic domains to increase potency of existing immunotherapies. Lipophilic modifications for lymph node targeting offer promise as a flexible platform by modifying different combinations of adjuvants and antigens. The flexibility of this system could be useful for modifying and improving other immunotherapies for cancer, as additional immune signals help amplify the immune response at the tumor site. Conversely, efforts could also explore targeting of signals to lymph nodes to direct immune responses away from inflammation that causes autoimmune disease. Additionally, the facile formulation and ability to modify different antigens could enable better precision in production, purity and screening of future immunotherapeutics.

3. Charge polarity has been utilized in a variety of methods to self-assemble immune signals

i). Alternating cationic and anionic moieties allows for layer-by-layer electrostatic assembly

Electrostatic interactions are a powerful driving force that can facilitate assembly of alternating anionic and cationic components into layered structures. This strategy has been employed in the development of immunotherapeutics to create polyelectrolyte multilayer (PEM) capsules. Earlier work established that PEMs can encapsulate antigen by coating antigen-loaded calcium carbonate particles with alternating layers of anionic dextran sulfate and cationic polylysine polymers. The calcium carbonate was subsequently dissolved out to create PEM capsules with antigen in their core.36 Compared to vaccination with soluble antigen, PEMs improved delivery of antigen to APCs and generated immunity in mice against melanoma.37 Subsequently, PEMs were developed by incorporating an adjuvant as the anionic layer. The PEM capsules could induce APC and T cell activation in response to antigen and adjuvant within the capsules.38 Whereas past systems incorporated polymers or other materials as structural components, our lab has recently developed PEMs composed entirely of immune signals.39 To support assembly, these immune polyelectrolyte multilayers (iPEMs) were composed of peptide antigens anchored with cationic amino acids on the C-terminal end and anionic nucleic-acid based adjuvants coated on gold nanoparticles using a layer-by-layer assembly process. These iPEM-coated nanoparticles induced antigen-specific T cell activation in mice after vaccination, indicating both signals remained bioactive after being assembled in iPEM coatings. Further, the responses generated by iPEMs were more potent than those observed when mice received vaccines containing equivalent doses of soluble signals.

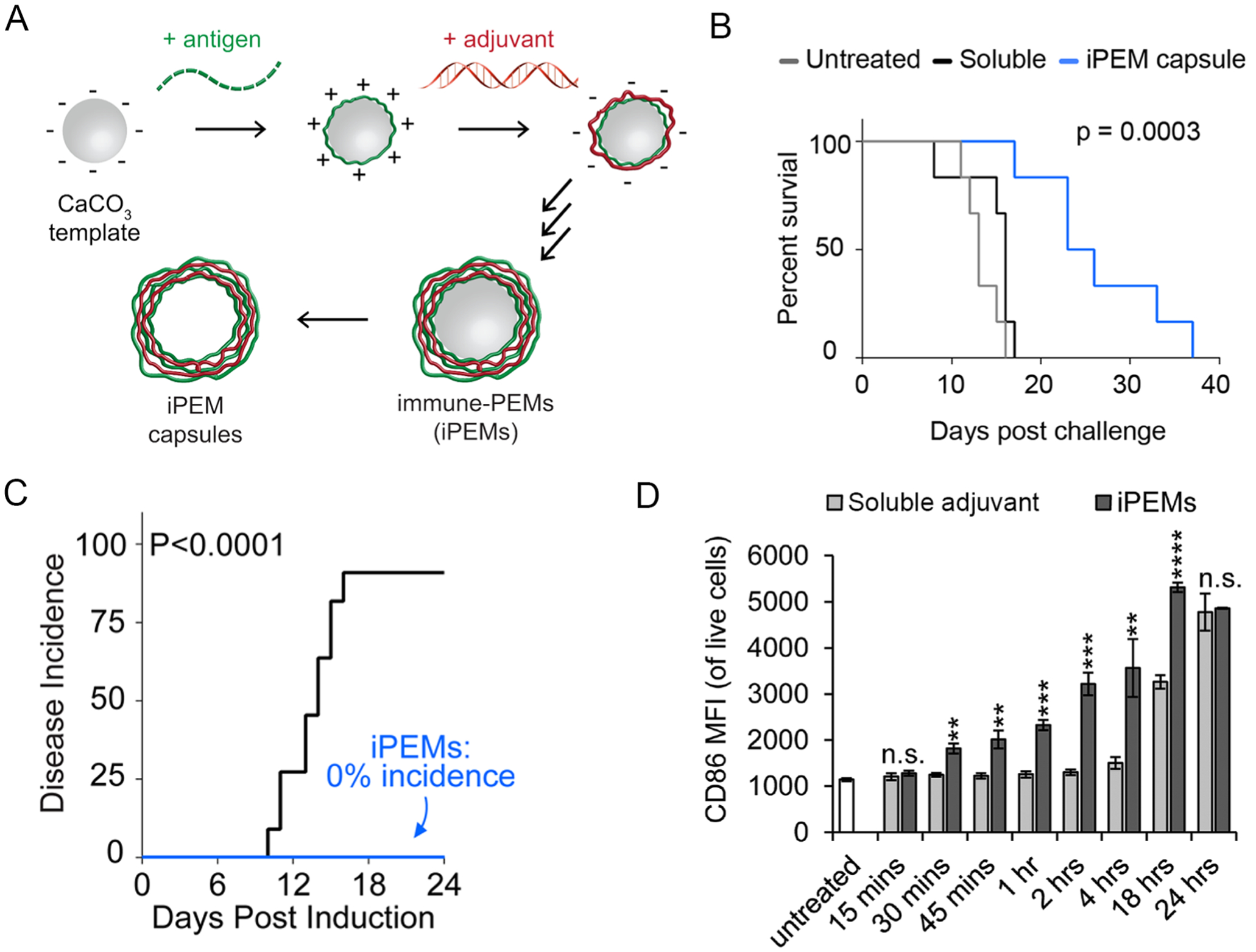

Commonly used biomaterial polymers used to encapsulate therapeutic agents exhibit intrinsic immunogenic features that that can elicit inflammation even in the absence of other immune signals.40,41 These effects can be a confounding variable in developing therapeutic strategies that require precise understanding and control of therapeutic outcomes to establish safety and clinical translation. With this challenge in mind, our lab developed stable iPEM capsules that did not rely on a particle core.2,42 This was achieved by assembling alternating layers of cationic peptide antigens and anionic adjuvants on a calcium carbonate template. The template was then dissolved out to create hollow capsules composed entirely of immune signals (Fig. 4A). These structures juxtapose immune signals at tunable ratios with 100% cargo loading; this is unique relative to polymer or lipid-based particles in which the carrier represents a significant fraction of the formulation. In a melanoma mouse model, mice vaccinated with iPEMs containing a melanoma antigen and adjuvant significantly slowed tumor growth and increased median survival time (Fig. 4B).42

Figure 4.

A) Assembly of iPEMs B) Treatment with iPEMs lengthened survival time in a mouse tumor model. A+B were adapted with permission from ref. 42. Copyright 2015 American Chemical Society. C) iPEMs completely prevented onset of disease in a mouse model of multiple sclerosis. Adapted with permission from ref. 2. Copyright 2016 American Chemical Society. D) iPEMs activated DCs faster than soluble adjuvant, measured by expression of the activation marker CD86. Adapted with permission from ref. 44. Copyright 2018 Wiley.

Because of the modular assembly of iPEMs, we extended the concept to autoimmune disease therapies and promotion of immunological tolerance.2 The goal of immunotherapies for autoimmune disease is to deliver self-antigens attacked during disease to APCs and have the APCs present self-antigen without co-stimulatory signals. The hypothesis is that when T cells bind cognate self-antigen without co-stimulatory signals, T cells will not become activated or will be polarized towards regulatory phenotypes that maintain tolerance to self-tissue. To achieve this outcome, we developed iPEMs composed of antigen targeted by T cells in a mouse model of multiple sclerosis and a regulatory immune signal that inhibits an inflammatory pathway that is active during autoimmunity. In vitro studies indicated that iPEMs successfully inhibited presentation of co-stimulatory signals by DCs and reduced antigen-specific T cell activation in response to cognate antigen. When tested in vivo, iPEM treatment completely prevented disease in mice (Fig. 4C), establishing the promise of this platform to promote tolerance.

From a manufacturing perspective, iPEMs are relatively simple compared to other common formulation methods that involve complex polymers or excipients and additional energy input for encapsulation of immune signals. We have shown that assembly of iPEMs is pH dependent with respect to both antigen and adjuvant components, and the relative loading of both components can be tuned by controlling the pH.43 With increasing understanding of the engineering criteria that drive assembly, iPEMs create the possibility of incorporating and delivering a range of antigens and adjuvants with control over the relative combinations of signals.

Other aspects of immunotherapies, such as cellular trafficking and route of injection, are also important to understand to develop clinically relevant therapies. We have shown that the signals delivered by iPEMs were co-localized in lymph nodes and induced more potent T cell activation than when signals were delivered in soluble form.42 Using quantitative analysis, we have also confirmed that 95% of cells that contained at least one signal present in iPEMs (i.e., antigen or adjuvant) also contained the other signal.43 iPEMs also activated DCs faster than soluble signals (Fig. 4D) and quickly trafficked through endosomal/lysosomal pathways involved in antigen presention.44 These are desired outcomes to achieve efficient delivery of immunotherapeutics that incorporate signals that target endosomal receptors. Utilizing layer-by-layer assembly, the Hammond lab recently revealed that targeting of particular cells and trafficking pathways can be tuned as a function of the surface chemistry.45 This observation is intriguing as it indicates that the choice of signals incorporated into iPEMs can be extended to target a broad range of pathways with the right design. Thus, iPEMs mimic key benefits of micro- and nanoparticles, such as co-delivery of signals in particulate form, and eliminate some of the disadvantageous. For example, iPEMs do not have additional components that could exhibit carrier effects or create intrinsic immunogenicity; the latter could be problematic in exacerbating autoimmune diseases.

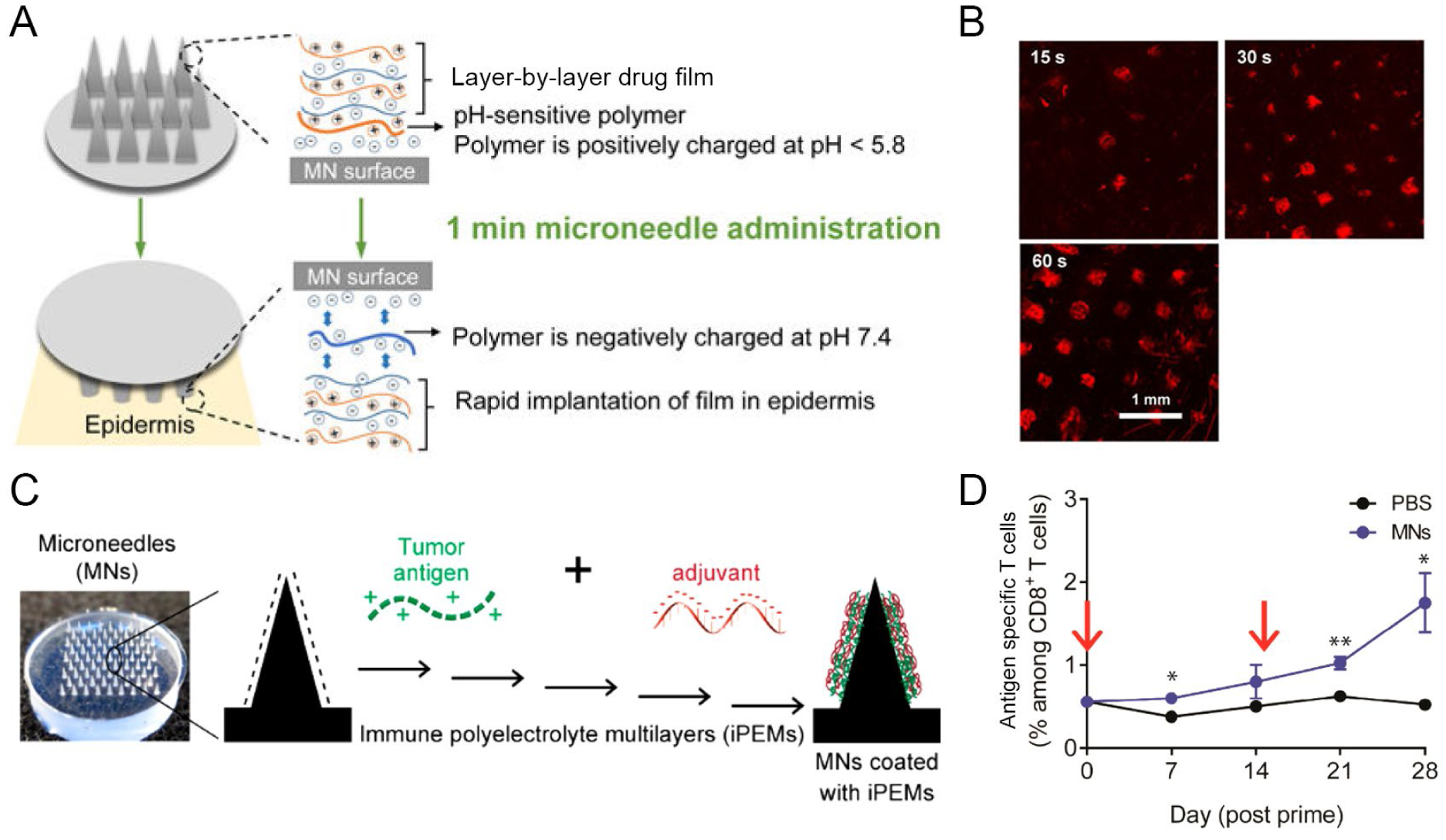

In addition to some of the targeting concepts discussed above, the route of administration can impact this aspect. In particular, the skin is an environment rich with immune cells, and thus has significant potential for immunotherapies. For example, intradermal injection often leads to efficient immune responses relative to intramuscular or subcutaneous injections, and we have seen similar effects with iPEM capsules.46 It is not surprising then that microneedle patches have seen increasing interest as alternative technologies to needle-based injections. These patches utilize polymer needles that are long enough to penetrate the skin but too short to reach pain receptors. Thus, microneedles allow pain-free treatment, and more specifically for immunotherapy, efficient delivery to the immune cell-rich dermal layer. The Irvine and Hammond labs employed layer-by-layer assembly to develop microneedles coated with polycationic polymers, anionic nucleic-acid based adjuvant, and plasmid DNA encoding a model antigen for transfection of APCs in the skin.47 Microneedles successfully delivered cargo to APCs in the dermal region of mice and non-human primates. In these studies, UV light was used to activate the surface of the microneedles and initiate release of the layers from the microneedle surface. In an attempt to develop more practical methods of cargo release, the Hammond lab recently developed charge invertible microneedles that rapidly released the signals upon insertion into the skin (Fig. 5A).48 Charge inversion due to the shift to physiological pH resulted in three consecutive layers of negative charge that strongly repelled each other and detached the film from the microneedle surface within one minute (Fig. 5B). These microneedles efficiently delivered antigen to APCs in mice, induced a strong antibody response, and were able to deliver adjuvant to APCs in human skin ex vivo.

Figure 5.

A) Charge invertible microneedles. B) Release of microneedle films (red) into the skin of mice. A+B were adapted with permission from ref. 48. Copyright 2018 American Chemical Society. C) iPEM coated microneedles. D) Expansion of melanoma specific T cells after microneedle vaccination. C+D were adapted with permission from ref. 3. Copyright 2017 American Chemical Society.

Our lab recently applied iPEM coatings on microneedles for cancer vaccination (Fig. 5C).3 The advantage of iPEMs in this context is the ability to concentrate tumor antigens and adjuvants to specialized immune cells in the skin. For the specific application of melanoma, skin delivery is also relevant because the skin is the location of many melanomas. Upon vaccination of mice with microneedles coated with a human melanoma antigen and adjuvant, the signals were co-localized at the site of injection. T cells specific for the melanoma antigen expanded over 4 weeks in response to a prime-boost immunotherapy strategy (Fig. 5D), indicating the iPEM-coated microneedles promoted a tumor-specific immune response against the melanoma antigen. Studies from our lab indicate that modulation of immune responses over extended periods of time can be achieved by controlling the release kinetics of iPEM films.49 Thus, an interesting direction could be the development of rapidly releasing but slowly degrading iPEM films that release from microneedle substrates to form depots of immune signals within the dermal layer and modulate immune responses over time.

ii). One step electrostatic adsorption provides a facile method of conjugation

Another self-assembly approach is to simply mix two oppositely charged components in aqueous solution, allowing assembly into complexes due to electrostatic interactions. Several efforts have used electrostatic assembly to adsorb antigen and/or adjuvants with preformed carrier components, such as micelles or nanofibers.50–54 A common observation among these studies is improved T cell activation and higher antibody titers compared to when antigen and adjuvant are delivered in soluble form. This recurring observation further highlights the importance of co-delivering immune signals and delivery in a particulate form to increase signal potency.

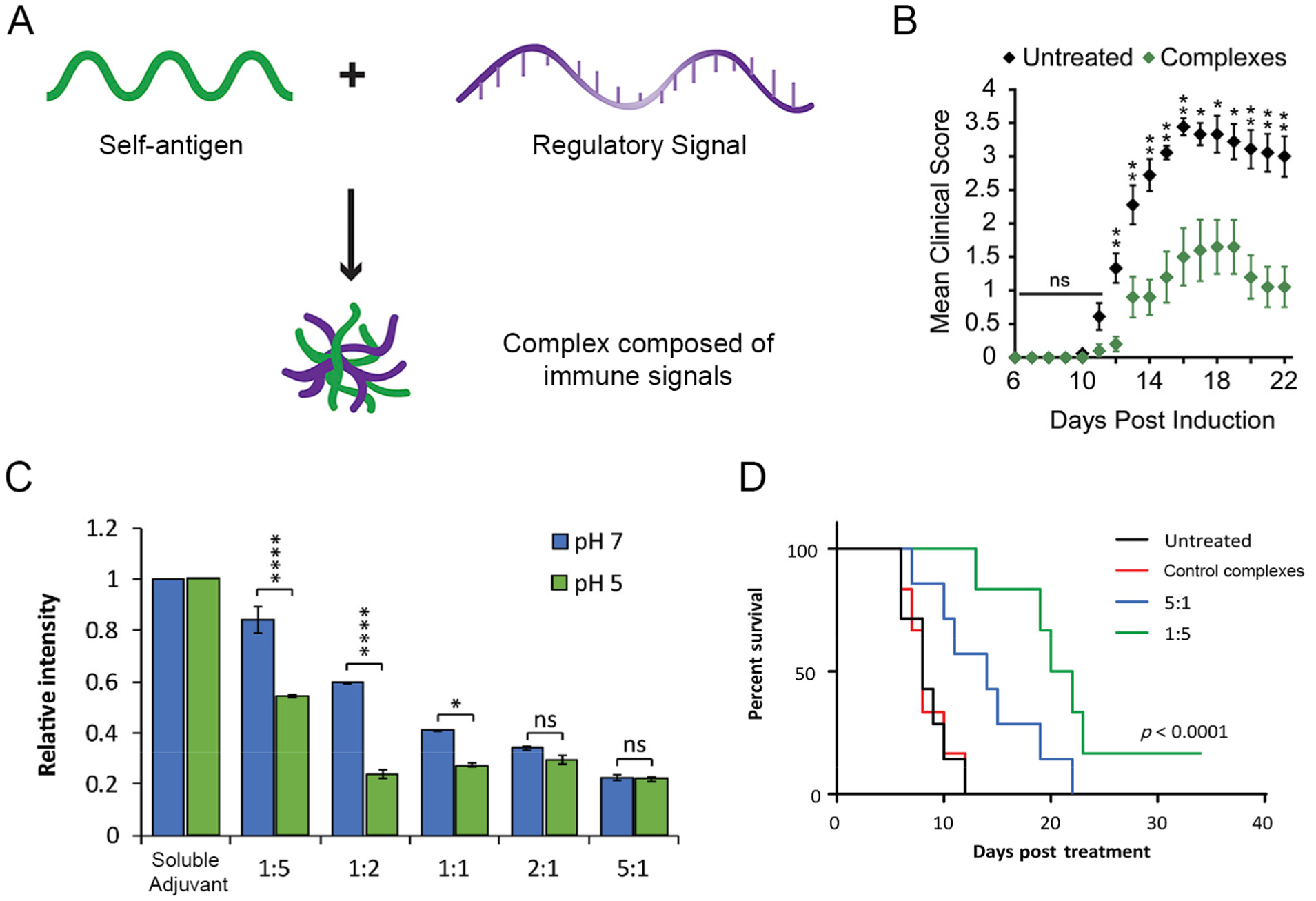

Our lab has used electrostatic assembly to create complexes composed entirely of immune signals by incubating oppositely charged signals in aqueous conditions.4 For example, using analogous signals discussed above for iPEMs, these complexes can be created from self-antigens and regulatory immune signals to combat autoimmune disease (Fig. 6A). Compared to layer-by-layer assembly, this approach sacrifices the ability to control the relative loading of multiple signals but simplifies assembly into a single step. However, these complexes still retain other benefits, such as eliminating any confounding carrier effects, enable co-delivery of signals, and allowing 100% of the administered dose to be therapeutic cargo (i.e., no carrier). Treating mice with complexes in a mouse model of multiple sclerosis reduced the severity of disease over time (Fig. 6B), highlighting the method’s potential for therapeutic application. Mechanistic studies using this one-step approach revealed some interesting correlations between biophysical properties during complex formation and biological effects. For example, a binding assay indicated high cationic to anionic charge ratios resulted in stronger adjuvant binding (Fig. 6C).55 However, complexes assembled with a low cationic to anionic charge ratio were more effective in prolonging survival in a melanoma mouse model (Fig. 6D). Reconciling these findings revealed high cationic to anionic charge ratio could result in tighter binding but hindered accessibility and functionality of the signals in therapeutic settings. Thus, the studies revealed a balance between driving forces needed to promote assembly and the need to maintain accessibility of the cargo to promote desired immunotherapeutic functions.

Figure 6.

A) Complexes for autoimmune disease. B) Treatment with complexes reduced severity of disease, indicated by reduced mean clinical score. A+B were adapted with permission from ref. 4. Copyright 2017 Elsevier. C) Relative intensity decreased as cationic to anionic charge ratio increased, indicating stronger binding of adjuvant at higher ratios. D) Cancer survival after treatment with complexes. C+D were adapted with permission from ref. 55. Copyright 2018 Springer Nature.

iii). Hydrogen bonding is a driving force with abundant engineering potential

Recent studies have utilized hydrogen bonds to create intricately self-assembled structures for immunotherapies.56–61 For example, one group utilized lipid-modified DNA sequences and either adjuvant and/or antigen sequences that were elongated with a complementary sequence to the DNA.57,58 Hybridization of DNA and its complementary sequence on the elongated immune signals facilitated assembly of components into nanoparticles. Another approach developed an antigen aptamer-adjuvant fused sequence that integrated into DNA hydrogels via hybridization with a DNA linker.59 When administered to mice in combination with doxorubicin, the hydrogel induced an inflammatory immune response and decreased tumor growth in a breast cancer model. Most recently, Li et al. utilized hydrogen bonding to create a treatment employing immunotherapy, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy all in one.61 Particles were composed of diselemide, which is an inhibitor of antigen presentation, and pemetrexel, an approved chemotherapy. The two drugs self-assembled due to triple hydrogen bonds between the cytosine on diselemide and guanine on pemetrexel. Until recently, hydrogen bonding has scarcely been used as the main driving force for self-assembly of immunotherapies. However, as evidenced by natural phenomena such as formation of the DNA helix, hydrogen bonds have the capacity to facilitate assembly of highly intricate and stable natural structures. Further exploration of hydrogen bonding in bioengineering contexts could reveal novel assembly strategies for development of controlled and precisely tuned immunotherapies.

4. Conclusion

Strategies utilizing self-assembly benefit from facile, low energy manufacturing methods that result in consistent and controlled formulation of immunotherapies. The aspect of co-delivering immune cues to program responses against specific antigens provides exciting potential for overcoming challenges related to off-target effects. To realize these benefits in clinical settings, a better understanding of how to design immune signals for assembly needs to be developed. Electrostatic assemblies may benefit from utilizing hydrophobic and/or hydrogen bonding motifs that stabilize formulation and increase the capacity to incorporate a range of signals. Elucidating some general principles of what biophysical properties can achieve self-assembly irrespective of the specific immune cue would increase the modulatory of self-assembly strategies and allow for more practical development of personalized immunotherapies. Additionally, we identified several observations that indicated physical properties, such as surface charge and antigen density, impact immunological responses and therapeutic efficacy. Thus, in addition to the specific immune cues, the biophysical properties of immunotherapies seem to be important considerations when designing therapies to program specific responses. Yet, the connection between biophysical properties and immune responses is poorly defined. With a better understanding of how to design immunotherapies, self-assembly could be a powerful modality for the development of new and improved clinical immunotherapies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by the United States Department of Veterans Affairs (Award # I01BX003690) and the National Institutes of Health (Awards R01EB027143, R01EB026896, and R01AI144667) to CMJ, and a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program Grant (DGE 1840340) to EF. CE is funded by the Clark Doctoral Fellows Program, supported by the A. James & Alice B. Clark Foundation at the University of Maryland

AUTHOR BIOGRAPHIES

Eugene Froimchuk is a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellow in the Fischell Department of Bioengineering at the University of Maryland, College Park. He received his B.S. in biochemistry and biological sciences from the University of Maryland, College Park, and then worked at the National Institutes of Health as an Intramural Research Training Award (IRTA) Fellow for a year before beginning his graduate training.

Sean Carey is a doctoral student in the Fischell Department of Bioengineering at the University of Maryland, College Park. He received his B.S. in chemical engineering from the Swanson School of Engineering at the University of Pittsburgh.

Camilla Edwards is a Clark Doctoral Fellow in the Fischell Department of Bioengineering at the University of Maryland, College Park. She completed her B.S. in materials science and engineering from the Herbert Wertheim School of Engineering at the University of Florida, then worked for two years at Procter and Gamble as a packaging engineer before beginning graduate training.

Christopher M. Jewell is the Minta Martin Professor of Engineering and Associate Chair for Research in the Fischell Department of Bioengineering at the University of Maryland. Dr. Jewell is also a Research Biologist with the United States Department of Veterans Affairs at the VA Maryland Healthcare System. His group’s research integrates engineering and immunology to study immune function for therapeutic vaccines targeting autoimmunity and cancer. He earned his PhD in Chemical Engineering from the University of Wisconsin, then worked as a consultant at the Boston Consulting Group in the Healthcare Practice. Dr. Jewell completed his postdoctoral training at MIT and Harvard.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

C.M.J. is an employee of the VA Maryland Health Care System. The views reported in this paper do not reflect the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government. C.M.J. has an equity position in Cellth Systems, LLC and Avidea Technologies.

REFERENCES

- (1).Lynn GM; Sedlik C; Baharom F; Zhu Y; Ramirez-Valdez RA; Coble VL; Tobin K; Nichols SR; Itzkowitz Y; Zaidi N; Gammon JM; Blobel NJ; Denizeau J; de la Rochere P; Francica BJ; Decker B; Maciejewski M; Cheung J; Yamane H; Smelkinson MG; Francica JR; Laga R; Bernstock JD; Seymour LW; Drake CG; Jewell CM; Lantz O; Piaggio E; Ishizuka AS; Seder RA Peptide-TLR-7/8a Conjugate Vaccines Chemically Programmed for Nanoparticle Self-Assembly Enhance CD8 T-cell Immunity to Tumor Antigens. Nat. Biotechnol 2020, 38, 320–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This effort utilized peptide amphiphilies to create an immunotherapy containing tumor-specific antigens and stimulatory adjuvants as a platform for the development of personalized cancer treatment.

- (2).Tostanoski LH; Chiu YC; Andorko JI; Guo M; Zeng X; Zhang P; Royal W 3rd; Jewell CM Design of Polyelectrolyte Multilayers to Promote Immunological Tolerance. ACS Nano 2016, 10, 9334–9345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This effort utilized electrostatic interactions to assemble hollow capsules composed entirely of antigens and regulatory immune signals as a platform for the development of immunotherapies for autoimmune disease.

- (3).Zeng Q; Gammon J; Tostanoski LH; Chiu YC; Jewell CM In Vivo Expansion of Melanoma-Specific T Cells Using Microneedle Arrays Coated with Immune-Polyelectrolyte Multilayers. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng 2017, 3, 195–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This effort utilized electrostatic interactions to coat microneedle patches with alternating cationic and anionic melanomar-specific antigen and adjuvant to target immune signals to the dermal layer.

- (4).Hess KL; Andorko JI; Tostanoski LH; Jewell CM Polyplexes assembled from self-peptides and regulatory nucleic acids blunt toll-like receptor signaling to combat autoimmunity. Biomaterials 2017, 118, 51–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; As an alternative to layer-by-layer assembly, this effort electrostatically assembled complexes composed entirely of immune signals by a one step mixing process for the development of immunotherapies for autoimmune disease.

- (5).Weiner LM; Dhodapkar MV; Ferrone S Monoclonal Antibodies for Cancer Immunotherapy. Lancet 2009, 373, 1033–1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Darvin P; Toor SM; Sasidharan Nair V; Elkord E Immune checkpoint inhibitors: recent progress and potential biomarkers. Exp. Mol. Med 2018, 50, 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Bookstaver ML; Tsai SJ; Bromberg JS; Jewell CM Improving Vaccine and Immunotherapy Design Using Biomaterials. Trends Immunol 2018, 39, 135–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Oakes RS; Froimchuk E; Jewell CM Engineering Biomaterials to Direct Innate Immunity. Adv. Ther. (Weinheim, Ger.) 2019, 2, pii: 1800157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Eppler HB; Jewell CM Biomaterials as Tools to Decode Immunity. Adv. Mater 2019, 32, 1903367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Lin AY; Almeida JP; Bear A; Liu N; Luo L; Foster AE; Drezek RA Gold nanoparticle delivery of modified CpG stimulates macrophages and inhibits tumor growth for enhanced immunotherapy. PLoS One 2013, 8, e63550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Chen N; Wei M; Sun Y; Li F; Pei H; Li X; Su S; He Y; Wang L; Shi J; Fan C; Huang Q Self-assembly of poly-adenine-tailed CpG oligonucleotide-gold nanoparticle nanoconjugates with immunostimulatory activity. Small 2014, 10, 368–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Riley RS; June CH; Langer R; Mitchell MJ Delivery technologies for cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2019, 18, 175–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Tostanoski LH; Jewell CM Engineering self-assembled materials to study and direct immune function. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev 2017, 114, 60–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Collier JH; Messersmith PB Enzymatic Modification of Self-Assembled Peptide Structures With Tissue Transglutaminase. Bioconjugate Chem 2003, 14, 748–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Rudra JS; Tian YF; Jung JP; Collier JH A Self-Assembling Peptide Acting as an Immune Adjuvant. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2010, 107, 622–627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Huang ZH; Shi L; Ma JW; Sun ZY; Cai H; Chen YX; Zhao YF; Li YM A Totally Synthetic, Self-Assembling, Adjuvant-Free MUC1 Glycopeptide Vaccine for Cancer Therapy. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134, 8730–8733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Rudra JS; Sun T; Bird KC; Daniels MD; Gasiorowski JZ; Chong AS; Collier JH Modulating Adaptive Immune Responses to Peptide Self-Assemblies. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 1557–1564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Chen J; Pompano RR; Santiago FW; Maillat L; Sciammas R; Sun T; Han H; Topham DJ; Chong AS; Collier JH The Use of Self-Adjuvanting Nanofiber Vaccines to Elicit High-Affinity B Cell Responses to Peptide Antigens Without Inflammation. Biomaterials 2013, 34, 8776–8785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Pompano RR; Chen J; Verbus EA; Han H; Fridman A; McNeely T; Collier JH; Chong AS Titrating T-cell Epitopes Within Self-Assembled Vaccines Optimizes CD4+ Helper T Cell and Antibody Outputs. Adv. Healthcare Mater 2014, 3, 1898–1908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Chesson CB; Huelsmann EJ; Lacek AT; Kohlhapp FJ; Webb MF; Nabatiyan A; Zloza A; Rudra JS Antigenic Peptide Nanofibers Elicit Adjuvant-Free CD8+ T Cell Responses. Vaccine 2014, 32, 1174–1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Wen Y; Waltman A; Han H; Collier JH Switching the Immunogenicity of Peptide Assemblies Using Surface Properties. ACS Nano 2016, 10, 9274–9286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Wu Y; Norberg PK; Reap EA; Congdon KL; Fries CN; Kelly SH; Sampson JH; Conticello VP; Collier JH A Supramolecular Vaccine Platform Based on alpha-Helical Peptide Nanofibers. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng 2017, 3, 3128–3132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Wu Y; Kelly SH; Sanchez-Perez L; Sampson JH; Collier JH Comparative study of α-helical and β-sheet self-assembled peptide nanofiber vaccine platforms: influence of integrated T-cell epitopes. Biomater. Sci 2020, 8, 3522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Purwada A; Tian YF; Huang W; Rohrbach KM; Deol S; August A; Singh A Self-Assembly Protein Nanogels for Safer Cancer Immunotherapy. Adv. Healthcare Mater 2016, 5, 1413–1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Miura R; Sawada S; Mukai S; Sasaki Y; Akiyoshi K Synergistic anti-tumor efficacy by combination therapy of a self-assembled nanogel vaccine with an immune checkpoint anti-PD-1 antibody. RSC Adv 2020, 10, 8074–8079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Miura R; Sawada SI; Mukai SA; Sasaki Y; Akiyoshi K Antigen Delivery to Antigen-Presenting Cells for Adaptive Immune Response by Self-Assembled Anionic Polysaccharide Nanogel Vaccines. Biomacromolecules 2020, 21, 621–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Fröhlich E The role of surface charge in cellular uptake and cytotoxicity of medical nanoparticles. Int. J. Nanomed 2012, 7, 5577–5591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Seong SY; Matzinger P Hydrophobicity: An Ancient Damage-Associated Molecular Pattern That Initiates Innate Immune Responses. Nat. Rev. Immunol 2004, 4, 469–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Rad-Malekshahi M; Fransen MF; Krawczyk M; Mansourian M; Bourajjaj M; Chen J; Ossendorp F; Hennink WE; Mastrobattista E; Amidi M Self-Assembling Peptide Epitopes as Novel Platform for Anticancer Vaccination. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2017, 14, 1482–1493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Hess KL; Oh E; Tostanoski LH; Andorko JI; Susumu K; Deschamps JR; Medintz IL; Jewell CM Engineering Immunological Tolerance Using Quantum Dots to Tune the Density of Self-Antigen Display. Adv. Funct. Mater 2017, 27, 1700290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Black M; Trent A; Kostenko Y; Lee JS; Olive C; Tirrell M Self-assembled peptide amphiphile micelles containing a cytotoxic T-cell epitope promote a protective immune response in vivo. Adv. Mater 2012, 24, 3845–3849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Da Silva CG; Camps MGM; Li T; Chan AB; Ossendorp F; Cruz LJ Co-delivery of immunomodulators in biodegradable nanoparticles improves therapeutic efficacy of cancer vaccines. Biomaterials 2019, 220, 119417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Liu H; Moynihan KD; Zheng Y; Szeto GL; Li AV; Huang B; Van Egeren DS; Park C; Irvine DJ Structure-based programming of lymph-node targeting in molecular vaccines. Nature 2014, 507, 519–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Zhu G; Lynn GM; Jacobson O; Chen K; Liu Y; Zhang H; Ma Y; Zhang F; Tian R; Ni Q; Cheng S; Wang Z; Lu N; Yung BC; Lang L; Fu X; Jin A; Weiss ID; Vishwasrao H; Niu G; Shroff H; Klinman DM; Seder RA; Chen X Albumin/vaccine nanocomplexes that assemble in vivo for combination cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Commun 2017, 8, 1954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Appelbe OK; Moynihan KD; Flor A; Rymut N; Irvine DJ; Kron SJ Radiation-enhanced delivery of systemically administered amphiphilic-CpG oligodeoxynucleotide. J. Controlled Release 2017, 266, 248–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).De Koker S; De Geest BG; Singh SK; De Rycke R; Naessens T; Van Kooyk Y; Demeester J; De Smedt SC; Grooten J Polyelectrolyte microcapsules as antigen delivery vehicles to dendritic cells: uptake, processing, and cross-presentation of encapsulated antigens. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl 2009, 48, 8485–8489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).De Geest BG; Willart MA; Hammad H; Lambrecht BN; Pollard C; Bogaert P; De Filette M; Saelens X; Vervaet C; Remon JP; Grooten J; De Koker S Polymeric multilayer capsule-mediated vaccination induces protective immunity against cancer and viral infection. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 2136–2149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).De Geest BG; Willart MA; Lambrecht BN; Pollard C; Vervaet C; Remon JP; Grooten J; De Koker S Surface-engineered polyelectrolyte multilayer capsules: synthetic vaccines mimicking microbial structure and function. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl 2012, 51, 3862–3866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Zhang P; Chiu YC; Tostanoski LH; Jewell CM Polyelectrolyte Multilayers Assembled Entirely from Immune Signals on Gold Nanoparticle Templates Promote Antigen-Specific T Cell Response. ACS Nano 2015, 9, 6465–6477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Andorko JI; Hess KL; Pineault KG; Jewell CM Intrinsic immunogenicity of rapidly-degradable polymers evolves during degradation. Acta Biomater 2016, 32, 24–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Dold NM; Zeng Q; Zeng X; Jewell CM A poly(beta-amino ester) activates macrophages independent of NF-kappaB signaling. Acta Biomater 2018, 68, 168–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Chiu YC; Gammon J; Andorko JI; Tostanoski LH; Jewell CM Modular Vaccine Design Using Carrier-Free Capsules Assembled from Polyionic Immune Signals. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng 2015, 1, 1200–1205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Chiu YC; Gammon JM; Andorko JI; Tostanoski LH; Jewell CM Assembly and Immunological Processing of Polyelectrolyte Multilayers Composed of Antigens and Adjuvants. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 18722–18731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Bookstaver ML; Hess KL; Jewell CM Self-Assembly of Immune Signals Improves Codelivery to Antigen Presenting Cells and Accelerates Signal Internalization, Processing Kinetics, and Immune Activation. Small 2018, 14, e1802202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Correa S; Boehnke N; Barberio AE; Deiss-Yehiely E; Shi A; Oberlton B; Smith SG; Zervantonakis I; Dreaden EC; Hammond PT Tuning Nanoparticle Interactions with Ovarian Cancer through Layer-by-Layer Modification of Surface Chemistry. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 2224–2237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Zhang P; Andorko JI; Jewell CM Impact of dose, route, and composition on the immunogenicity of immune polyelectrolyte multilayers delivered on gold templates. Biotechnol. Bioeng 2017, 114, 423–431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).DeMuth PC; Min Y; Huang B; Kramer JA; Miller AD; Barouch DH; Hammond PT; Irvine DJ Polymer multilayer tattooing for enhanced DNA vaccination. Nat. Mater 2013, 12, 367–376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).He Y; Hong C; Li J; Howard MT; Li Y; Turvey ME; Uppu DS; Martin JR; Zhang K; Irvine DJ; Hammond PT Synthetic Charge-Invertible Polymer for Rapid and Complete Implantation of Layer-by-Layer Microneedle Drug Films for Enhanced Transdermal Vaccination. ACS Nano 2018, 12, 10272–10280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Tostanoski LH; Eppler HB; Xia B; Zeng X; Jewell CM Engineering release kinetics with polyelectrolyte multilayers to modulate TLR signaling and promote immune tolerance. Biomater. Sci 2019, 7, 798–808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Wilson JT; Keller S; Manganiello MJ; Cheng C; Lee CC; Opara C; Convertine A; Stayton PS pH-Responsive nanoparticle vaccines for dual-delivery of antigens and immunostimulatory oligonucleotides. ACS Nano 2013, 7, 3912–3925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Luo Z; Li P; Deng J; Gao N; Zhang Y; Pan H; Liu L; Wang C; Cai L; Ma Y Cationic polypeptide micelle-based antigen delivery system: a simple and robust adjuvant to improve vaccine efficacy. J. Controlled Release 2013, 170, 259–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Wilson JT; Postma A; Keller S; Convertine AJ; Moad G; Rizzardo E; Meagher L; Chiefari J; Stayton PS Enhancement of MHC-I antigen presentation via architectural control of pH-responsive, endosomolytic polymer nanoparticles. AAPS J 2015, 17, 358–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Brubaker CE; Panagiotou V; Demurtas D; Bonner DK; Swartz MA; Hubbell JA A Cationic Micelle Complex Improves CD8+ T Cell Responses in Vaccination Against Unmodified Protein Antigen. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng 2016, 2, 231–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Xu Y; Wang Y; Yang Q; Liu Z; Xiao Z; Le Z; Yang Z; Yang C A versatile supramolecular nanoadjuvant that activates NF-κB for cancer immunotherapy. Theranostics 2019, 9, 3388–3397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Tsai SJ; Andorko JI; Zeng X; Gammon JM; Jewell CM Polyplex interaction strength as a driver of potency during cancer immunotherapy. Nano Res 2018, 11, 5642–5656. [Google Scholar]

- (56).Zhu G; Mei L; Vishwasrao HD; Jacobson O; Wang Z; Liu Y; Yung BC; Fu X; Jin A; Niu G; Wang Q; Zhang F; Shroff H; Chen X Intertwining DNA-RNA nanocapsules loaded with tumor neoantigens as synergistic nanovaccines for cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Commun 2017, 8, 1482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Jin JO; Park H; Zhang W; de Vries JW; Gruszka A; Lee MW; Ahn DR; Herrmann A; Kwak M Modular delivery of CpG-incorporated lipid-DNA nanoparticles for spleen DC activation. Biomaterials 2017, 115, 81–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Jin JO; Kim H; Huh YH; Herrmann A; Kwak M Soft matter DNA nanoparticles hybridized with CpG motifs and peptide nucleic acids enable immunological treatment of cancer. J. Controlled Release 2019, 315, 76–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Wei H; Zhao Z; Wang Y; Zou J; Lin O; Duan Y One-Step Self-Assembly of Multifunctional DNA Nanohydrogels: An Enhanced and Harmless Strategy for Guiding Combined Antitumor Therapy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 46479–46489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Wang Z; Shang Y; Tan Z; Li X; Li G; Ren C; Wang F; Yang Z; Liu J A supramolecular protein chaperone for vaccine delivery. Theranostics 2020, 10, 657–670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Li T; Pan S; Gao S; Xiang W; Sun C; Cao W; Xu H Diselenide-Pemetrexed Assemblies for Combined Cancer Immuno-, Radio-, and Chemotherapies. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl 2020, 59, 2700–2704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]