Abstract

Multiple organizations around the world have issued evidence-based exercise guidance for patients with cancer and cancer survivors. Recently, the American College of Sports Medicine has updated its exercise guidance for cancer prevention as well as for the prevention and treatment of a variety of cancer health-related outcomes (eg, fatigue, anxiety, depression, function, and quality of life). Despite these guidelines, the majority of people living with and beyond cancer are not regularly physically active. Among the reasons for this is a lack of clarity on the part of those who work in oncology clinical settings of their role in assessing, advising, and referring patients to exercise. The authors propose using the American College of Sports Medicine’s Exercise Is Medicine initiative to address this practice gap. The simple proposal is for clinicians to assess, advise, and refer patients to either home-based or community-based exercise or for further evaluation and intervention in outpatient rehabilitation. To do this will require care coordination with appropriate professionals as well as change in the behaviors of clinicians, patients, and those who deliver the rehabilitation and exercise programming. Behavior change is one of many challenges to enacting the proposed practice changes. Other implementation challenges include capacity for triage and referral, the need for a program registry, costs and compensation, and workforce development. In conclusion, there is a call to action for key stakeholders to create the infrastructure and cultural adaptations needed so that all people living with and beyond cancer can be as active as is possible for them.

Keywords: exercise, physical medicine and rehabilitation, physical therapy, supportive care

Introduction

Multiple US and international organizations have published exercise recommendations for patients living with and beyond cancer, including the American Cancer Society (ACS),1 the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM),2 Exercise and Sports Science Australia,3 Cancer Care Ontario,4 and the Clinical Oncology Society of Australia.5 In March 2018, the ACSM convened a Second Roundtable on Exercise and Cancer Prevention and Control. This second Roundtable included 17 organizations from multiple disciplines (see Supporting Table 1) and set out to review and update prior recommendations on cancer prevention and control. The products of this Roundtable include 3 articles.

The first article from the 2018 ACSM Roundtable presents the evidence that exercise is associated with a lower risk of developing cancer and improved survival after a cancer diagnosis.6 A summary of the evidence from this review and the other recent reviews on this topic7,8 is provided in Table 1. The ACSM expert panel concurred with other recent reviews, concluding that exercise prevents at least 7 types of cancer and that there is substantial evidence suggesting exercise is associated with improved cancer-specific survival in patients with breast, colon, and prostate cancer.

Table 1.

Summary of evidence that physical activity prevents cancer and improves cancer-specific survival6

| LEVEL OF EVIDENCE | PHYSICAL ACTIVITY AND LOWER RISK OF DEVELOPING CANCERa |

SEDENTARY TIME AND HIGHER RISK OF DEVELOPING CANCERa |

PREDIAGNOSIS PHYSICAL ACTIVITY AND LOWER RISK OF CANCER-SPECIFIC SURVIVALb |

POSTDIAGNOSIS PHYSICAL ACTIVITY AND LOWER RISK OF CANCER-SPECIFIC SURVIVALb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strong | Colon, breast, endometrial, kidney,c bladder,c esophageal (adenocarcinoma),d stomach (cardia)c | |||

| Moderate | Lungc | Endometrial,d colon,c lungc | Breast, colon | Breast, colon, prostate |

| Limited | Myeloma and hematologic,c head and neck,c pancreas,c ovary,c prostatec | Livere |

Level of evidence was based on the Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee (PAGAC)8 and World Cancer Research Fund (WCRF)7 reports (2018).

Level of evidence was based on a review by the American College of Sports Medicine Roundtable6.

Level of evidence conclusion was only by the PAGAC8.

Level of evidence was considered limited by the WCRF7.

Level of evidence conclusion was only by the WCRF7.

A second article provides an update on the growing scientific evidence base supporting the prescription of exercise to improve cancer-related health outcomes (other than cancer diagnosis, tumor burden, recurrence, and mortality).10 The ACSM expert panel concluded that there is sufficient evidence to support the efficacy of specific doses of exercise training to address cancer-related health outcomes, including fatigue, quality of life, physical function, anxiety, and depressive symptoms.10 There is also sufficient evidence to confirm the safety of resistance exercise training among patients with and at risk for breast cancer– related lymphedema.10 A summary of this evidence is provided in Table 2. This 2018 review of evidence retained the conclusions from the 2010 Roundtable that exercise training and testing was generally safe for cancer survivors and that every survivor should “avoid inactivity.”2 For the update, specific exercise prescriptions were generated for cancer-related health outcomes when there was strong evidence of an exercise benefit. In brief, the expert panel found that the majority of cancer health-related outcomes in the “strong” evidence category of Table 2 are improved by doing thrice-weekly aerobic activity for 30 minutes and that there is also evidence of a benefit for most of those same outcomes from twice-weekly resistance exercise: one exercise per major muscle group, 8 to 15 repetitions per set, 2 sets per exercise, progressing with small increments. When there was moderate or insufficient evidence of an exercise benefit, either an emerging exercise prescription or no prescription was generated, respectively.

Table 2.

Level of evidence for the benefit of exercise on cancer-related health outcomes10

| STRONG EVIDENCEa | MODERATE EVIDENCE | INSUFFICIENT EVIDENCE |

|---|---|---|

| Reduced anxiety | Sleep | Cardiotoxicity |

| Fewer depressive symptoms | Bone health (for osteoporosis prevention, not bone metastases) | Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy |

| Less fatigue | Cognitive function | |

| Better QOL | Falls | |

| Improved perceived physical function | Nausea | |

| No risk of exacerbating upper extremity lymphedema | Pain Sexual function Treatment tolerance |

Abbreviation: QOL, quality of life.

Effective exercise programs for improving these outcomes are thrice-weekly, moderate-intensity, aerobic and/or resistance training with one exception. Anxiety and depressive symptoms do not appear to be improved by a program of resistance training alone but do improve with aerobic training alone or in combination with resistance training. The scientific evidence review and scheme used for evidence evaluation are described in another article from the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) Roundtable.10

The current article, the third in this triad, identifies and uses elements from the ACSM’s Exercise Is Medicine (EIM) initiative to propose solutions to overcoming barriers to exercise referrals by oncology clinicians.1-5,11

Despite the exercise recommendations noted above, an analysis of greater than 9000 cancer survivors from the ACS Study of Cancer Survivors II (SCS-II) cohort indicated that only between 30% and 47% met current physical activity guidelines.12,13 In the Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS) cohort, approximately 45% of cancer survivors reported regular physical activity, although this varied by tumor site (32% vs 53% in breast cancer vs prostate cancer survivors, respectively).9 Data from the United Kingdom indicated that 31% of people living with and beyond cancer are completely inactive.14 Reasons for a lack of regular exercise among people living with and beyond cancer are multifactorial, but multiple studies have documented a lack of recommendation from an oncology clinician.15-17 Multiple studies of breast, colorectal, prostate, and a mixed cohort of cancer survivors noted that greater than 80% of patients were interested in receiving advice from their oncology care team.18-20 Despite this, studies suggest that 9% of nurses and from 19% to 23% of oncology physicians refer patients with cancer to exercise programming.13,17,21,22 A recent survey of 971 oncology clinicians that was conducted by the American Society of Clinical Oncology indicated that 78.9% of respondents agreed that oncology clinicians should recommend physical activity to their patients.23 Observed barriers to clinicians referring patients to exercise programming include lack of awareness of the potential value of exercise in cancer populations, uncertainty regarding the safety or suitability of exercise for a particular patient, lack of awareness regarding available programs to help facilitate exercise in cancer populations, need for education and skills development for making referrals, and a belief that referrals to exercise programming are not within the scope of practice for oncology clinicians.21,22,24-26

In summary, the scientific evidence base supports exercise, and patients and clinicians generally agree that patients should be moving throughout their cancer therapy and survivorship. Translating from the current state to exercise assessment, advice, referral, and engagement as standard practice for all people living with and beyond cancer is a multifactorial puzzle to be solved. We recognize the need for improved awareness of benefits, clinician referrals, programming, workforce, systems for triage and referral, and other changes needed to realize a sustainable increase in exercise among people living with and beyond cancer. At the end of this article, we present a call to action intended to clarify the many parts of a multiple systems-level change needed to sustainably increase the proportion of people affected by cancer who exercise and/or keep physically active. Improvements in any one of these elements has the potential to solve a portion of this complex puzzle.

As such, the primary goal of this article is to address the above-noted barriers to oncology clinicians making exercise referrals standard practice, including the provision of straightforward tools intended to make it easier for clinicians to recommend and refer patients to safe, effective, and appropriate exercise programming. Other professionals can then take over for further assessment, triage, referral, or intervention, as appropriate. This article provides instructions for advising and referring patients to appropriate exercise programming, guidance regarding the incorporation of patient preferences and behavioral considerations when referring to exercise, and a description of examples of currently available exercise programs. We also present challenges to implementation and propose actions required from relevant stakeholders to help move oncology toward making exercise referrals a standard practice: a “call to action.”

What Oncology Clinicians Can Do Now: Assess, Advise, and Refer

The EIM initiative was launched by the ACSM in 2007 with the goal of incorporating physical activity assessment, advice, and referral as a standard part of patient health care for the prevention and treatment of chronic diseases.27 The EIM approach arose in part from successful clinical trials that trained primary health care providers (HCPs) to refer patients to exercise programming.28,29 These trials were informed by earlier successes in changing clinician behavior regarding use of the “5 A’s” for effective counseling for smoking cessation (eg, ask, advise, agree, assist, and arrange for follow-up).30 To date, the EIM approach has been adopted in several primary health care clinics31 as well as broadly across 3 large health care systems in the United States.32-35 To date, very few studies have used elements of EIM in the oncology care setting,16 but there is ample scope and a need to examine integration into cancer care. The evidence base strongly supports adoption of the EIM approach for all patients with chronic conditions, including people living with and beyond cancer.1-3,5,10,23 Therefore, we propose the EIM approach as a way forward in the oncology setting.

Indeed, a recent publication from the American Society of Clinical Oncology recommends the “5 A’s” approach that is the basis of the EIM approach noted below.23 The safety of these recommendations is supported by the finding of no adverse effects of exercise after cancer in general or as recommended by oncology clinicians in multiple trials16,36 and multiple meta-analyses.37-39

Step 1: Assess

The EIM approach includes the assessment of physical activity as a vital sign, and a review of the assessment by clinicians or their team prompts counseling and advice. Assessing patients’ physical activity at regular intervals, during medical visits, can function as a prompt to the patient—even if the patient has not acted on the provider’s prior advice to become active. Asking about physical activity behavior conveys to the patient that their HCP believes exercise is important to their functioning and recovery. Physical activity could become a vital sign, similar to blood pressure, and be recorded in the electronic health record.40 Multiple health systems across the United States have instituted the physical activity vital sign, including Prisma Health in South Carolina, Intermountain Health in Utah, and Kaiser Permanente.32-35 In one study, it was observed that patients with advanced, unresectable lung cancer assumed their oncologists were familiar with their functional status and activity profile, and they interpreted silence on these topics as tacit approval to maintain inactivity.25 Whether this is the case for all people living with and beyond cancer is unknown. That said, there is clear evidence that patients are more likely to exercise if their oncologist tells them to do so.16,17,36 When patients understand that exercise can help in the management of cancer-specific symptoms (eg, fatigue, poor physical functioning), they may become likely to act on provider advice.

Step 2: Advise

Clinicians can advise patients to increase physical activity if they are not currently reaching recommended activity levels, which leads to referrals.

Step 3: Refer

Patients need referral to appropriate exercise programming based on their current activity levels, medical status, and preferences.41,42 Some patients may already be regular exercisers and/or may prefer to exercise on their own. However, especially during treatment, patients are at risk for developing side effects that are a barrier to exercise. Patients may underestimate how the treatment might affect their ability to exercise on their own. Also, current evidence indicates that exercise under supervision yields better outcomes.10,43-47 Therefore, even for currently active patients, regular evaluation of activity levels is needed, and referral to exercise programming could be valuable. The provider’s willingness to discuss exercise during patient visits expresses confidence in the benefits of regular exercise during and after treatment. Referral to appropriate and effective programs and follow-up with an assessment of progress (or lack thereof ) at subsequent visits can serve as key transition points to change a patient’s behavior and affect their tolerance of or recovery from treatment.

It is also key that the clinical team repeat these 3 steps (assess, advise, and refer) and reinforce patients’ efforts to increase exercise at regular intervals with assessment of new late effects or other comorbidities that may impede or modify participation in exercise programming. This approach is consistent with the UK National Health Service “Making Every Contact Count” program,48 which provides evidence-based, hands-on guidance for the implementation of assessment, advice, and referrals to exercise programming at every clinical encounter.

The recommendation is that these 3 steps (assess, advise, and refer) occur at regular intervals, at oncology clinical encounters of medical importance, as medical treatment changes occur, and/or as a patient reports a change in their functional status. It is recommended that a process be developed for the incorporation of physical activity screening and referral into the standard care of oncology patients, much as has been recommended for distress screening.49 These steps can also become part of care plans for survivors.

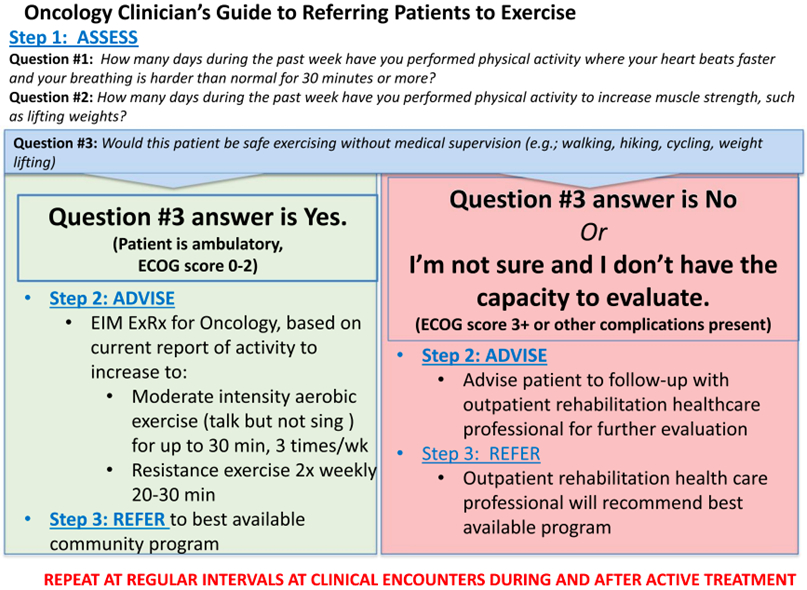

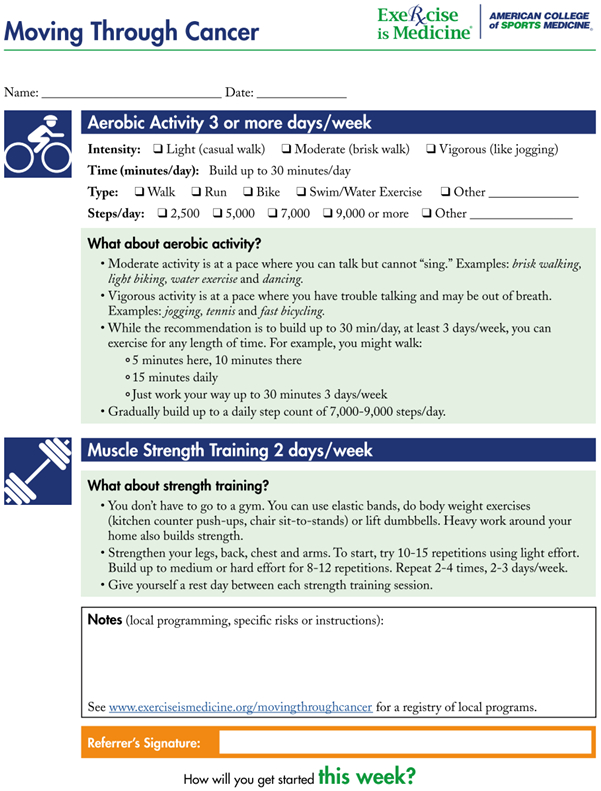

Within the first step (assess), there are 2 questions to ask the patient (Fig. 1). Multiple valid and reliable short surveys have been developed for brief physical activity screening assessment in the clinical setting. Herein, we recommend 1 question each about aerobic and resistance exercise derived from 2 brief physical activity screening surveys shown to have predictive validity for changes in obesity and other chronic disease outcomes.33-35,50 These 2 questions allow the clinical team to compare current activity levels with recommended levels. The clinician then asks himself or herself the third question (“Would this patient be safe exercising without medical supervision?”) to determine whether the patient is a suitable candidate for exercise outside of supervision by a health care professional (eg, physical therapist or clinical exercise physiologist). If the answer to question 3 is yes, oncologists are urged to provide the patient with a standardized prescription form (Fig. 2; also downloadable from exerciseismedicine.org/movingthroughcancer), which calls for the patient to perform an exercise dose of up to 30 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity 3 times a week and up to 20 to 30 minutes of resistance exercise 2 times a week.10 On the basis of the evidence review from the 2018 ACSM International, Multidisciplinary Roundtable on Exercise and Cancer Prevention and Control, this prescription is consistent with the minimal safe and effective dose to address anxiety, depressive symptoms, fatigue, quality of life, and physical function deficits.10 Clinicians will, of course, customize this prescription as they see fit.

Figure 1.

Oncology Clinicians’ Guide to Referring Patients to Exercise. ECOG indicates Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; EIM ExRx, Exercise is Medicine exercise prescription.

Figure 2.

Exercise prescription pad for clinicians. Downloadable from exerciseismedicine.org/movingthroughcancer.

However, there may be situations when the oncology clinician may not think the patient is safe to perform unsupervised exercise or may be unable to determine the answer to the third assessment question (eg, the example of patient 1 below). In this scenario, the patient should be referred to an outpatient rehabilitation health care professional for further evaluation and referral (Fig. 1). Referral to outpatient rehabilitation may also be appropriate if the goal is to address a specific therapeutic outcome.10

To illustrate this system, we offer 2 examples. Patient 1 is a 75-year-old man with metastatic prostate cancer who has been receiving hormonal therapy for 12 months. He has controlled hypertension, a body mass index in the obese range, and a history of non–insulin-dependent diabetes. He underwent a hip replacement 3 years ago. He still limps. In answer to the first 2 questions, he reports being completely sedentary. His Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status is 2, but the patient reports difficulty walking. The clinician would refer him to an outpatient rehabilitation clinician (ie, physiatrist, physical or occupational therapist). The outpatient rehabilitation clinician is well suited to assess, triage, and refer the patient to the appropriate exercise or rehabilitative programming.

Patient 2 is a 39-year-old woman with stage III colon cancer who completed surgery 8 weeks ago, entering a 6-month course of chemotherapy. Her body mass index is in the obese range, but she has no other chronic conditions. In answer to the first 2 questions, she reports walking at lunch once or twice a week. Her Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status is 0. The clinician can use the Moving Through Cancer exercise referral form (Fig. 2) to recommend increased exercise to 30 minutes of aerobic exercise 3 times a week and resistance training 2 or 3 times a week. If there is a local exercise oncology program known to the clinician, the patient can be referred directly there.

One key point to clarify is that oncology clinicians are not expected to give specifics of exercise prescriptions (eg, to prescribe specific resistance training exercises, equipment, or progression of weights) or to do extensive screening and triage to determine whether exercise needs to be done in a rehabilitative versus community setting. Oncology clinicians, however, play a vital role in telling the patient that it is important to exercise and pointing patients in the right direction to make that happen. An analogy to this might be when the oncology clinician refers a patient to resources for psychosocial distress. The oncology clinician is not asked to clinically evaluate for depression, anxiety, or other conditions as if they had the same training as a clinical psychologist. However, the oncology clinician can play a crucial role in pointing the patient toward psychological services in the cancer center and in the community. The American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer finds evaluation of psychosocial distress to be important enough that it is required to be evaluated at regular intervals and that accredited cancer treatment centers must have a plan in place for evaluation and referral. The approach proposed herein could be the first step toward a similar accreditation requirements for exercise referrals and a plan for regular assessment, advice, and referral.10

Ideally, for the third step (refer), oncology clinicians can also identify local HCP-supervised or community-based programming to which patients can be referred as a source of education, support, and supervision for meeting the recommended dose of exercise. As part of the efforts of the 2018 ACSM Roundtable, the authors have developed a registry with 150 programs from 25 countries, as described below.

Care Coordination: Transitioning Into and Between HCP-Supervised Versus Community Exercise Programming

At this time, referral to appropriate exercise programming is the goal, ideally achieved by having a health care professional with appropriate training for risk stratification and the early detection of treatment-related adverse effects integrated into patients’ clinical pathways. Integration of triage and referral into exercise programming directly into clinical pathways would ensure timely referral to the best suited professional, providing the right level of supervision, and practicing in the right setting. Multidisciplinary interventions would use a modular approach to ensure optimal tailoring to the needs of individual patients. One model, as yet substantially untested, would be to hire exercise professionals and have them work alongside physicians and nurses in oncology practices, clinics, or inpatient units. A major barrier to implementing this approach is that, at present, there is no payment model that would support it. Regardless, in an ideal setting, a modular, multidisciplinary approach, including assessments of physical capacity and performance, would be done at baseline and at predetermined time points downstream and would be integrated into all exercise programs. Validated patient-reported outcomes would be used to monitor health status, progress, and evaluate the effectiveness of interventions. Periodic, structured evaluation of processes and outcomes (uptake, adherence, waiting lists) of HCP-supervised exercise programs would be undertaken to ensure continuous improvement of services. Finally, explicit attention would be paid to the timely, appropriate, and successful transition from HCP-supervised exercise programs to community-based or home-based services.51-53 Transitions between HCP-supervised exercise programs and community programs are notoriously challenging. This underscores the need for the development of validated, evidence-based, clear, safe, and acceptable 2-way triage guidelines that clarify who is not able to go directly to a community program run by trained fitness instructors, as well as symptoms that community-based fitness instructors should monitor for referral back to health care professionals. There is programming in Canada and the Netherlands that has achieved many of these aspirational goals.51,52 To expand the availability of such high-quality, multidisciplinary, integrated exercise oncology care will require addressing reimbursement and workforce development issues, as reviewed below. In particular, it is currently unclear who should be in charge of the referral and triage process; who should begin the process; or who should be reimbursed or rewarded for actions related to assessment, advice, and referral to exercise and rehabilitative programming. In light of this current state, we recommend the use of the simple EIM approach described above. In the absence of fully integrated systems, this will at least alert patients that their oncology clinicians hold the expectation of regular physical activity during and beyond treatment. A subset of patients is likely to be able to use these recommendations in self-directed programming. Another subset of patients will follow-up on a referral to outpatient rehabilitation.54 The remainder likely will need a greater infrastructure to support exercise for people living with and beyond cancer than currently exists in many settings. Waiting to start referrals until the full infrastructure is in place misses the opportunity for a greater proportion of patients to become active through the admittedly imperfect infrastructure that currently exists.

Behavioral Considerations and Patient Preferences

Exercise is only effective in improving clinical outcomes if the patient “fills the script” (does the exercise program). Changing behavior is complex and depends on personal, social, and environmental factors as well as individual and community resources. Referral to an appropriate exercise specialist who can assess these factors and guide the patient to a program that best fits their needs and preferences not only will facilitate exercise adoption but also will reduce the time burden on the medical professional (eg, oncologist). The clinician’s role of addressing the relevance of exercise for the specific patient, reinforcing behavior change, and making appropriate referrals is key to starting the process. For example, some patients need the support of group settings to adhere to exercise recommendations. Others may be unwilling to participate in community-based group exercise classes (cancer-specific or not) or in HCP-supervised programs or may have concerns about body image (eg, scars from surgery, dramatic weight gain or loss). Variability in confidence, self-efficacy, caregiver support, and psychological factors (depression, anxiety) are important considerations in choosing exercise programming recommendations that are likely to net real and lasting behavior change. Environmental factors, such as population density, local culture, walkability, safety concerns, and transportation constraints, may limit the choice of exercise setting. The availability of HCP-supervised exercise programs may be limited by workforce challenges. Providers trained in cancer rehabilitation or cancer exercise training are unavailable in many geographical locations. Distance from clinical or community settings, program cost, local traffic conditions, or a lack of eldercare or childcare may make home-based exercise the best choice for many patients.55-57 There is consistent evidence that supervised exercise is more effective but that there is still benefit to home-based exercise.10 Telemedicine or other distance-based approaches may help when HCP supervision is needed but local programs do not exist. The ACSM registry of exercise programs for patients with cancer can help providers find programs that would be feasible, safe, and appropriate for patients.

There have been numerous programs offered to improve an individual patient’s adoption of exercise (see reviews by Fong et al58 and Stout et al59). Several theoretical approaches have been used in such interventions (see reviews by Pinto,60 Stacey et al,61 and Pudkasam et al62). Across the efficacy studies, techniques such as self-monitoring, goal setting, social support, feedback and problem solving, modeling, and feedback have been shown to be effective behavior change techniques.44,63 A meta-analysis of 14 randomized controlled trials among breast cancer survivors found that, although large effects on physical activity were reported by programs that provided more supervision, interventions by telephone or email were also effective.44 A recent comprehensive review of interventions for cancer survivors across different approaches, samples, and settings (128 randomized controlled trials, for a total of 13,050 patients with cancer) revealed that supervised programs produced larger effects on physical activity than unsupervised programs. 47 Another review concluded that interventions that have used behavioral theory tend produce the largest overall effect size for behavior change.64 Interventions that may be less intensive can produce smaller effects on outcomes, such as fitness and functioning; however, these interventions (distance-based by print, telephone, web, etc) can reach more survivors and can be less burdensome for patients who experience travel and scheduling barriers. An update of a 2013 Cochrane review (23 studies, for a total of 1372 patients treated for breast, prostate, colorectal, and lung cancer) showed that programs that achieved adherence of 75% or greater to exercise guidelines used techniques of goal-setting, setting graded exercise tasks and instructions on how to exercise.65 A synthesis of exercise programs that examined exercise maintenance (exercise assessed at least 3 months after program completion) revealed that graded tasks, social support, and action planning were used in studies that sustained significant behavior change.66

The successful promotion of exercise programming along the cancer continuum requires behavior change for many people affected by cancer. The behavior change is not only at the level of the individual patient, as is commonly assumed, but also at the level of oncology clinicians, family, and community. The majority of programs require physician approval before patient participation; hence, the behaviors of oncology clinicians (eg, medical, surgical, or radiation oncologists; oncology nurse practitioners; oncology nurses; allied health professionals) are key to patients being informed about and eligible to participate in programs and ongoing support for engagement in exercise programs. Although there are many competing considerations during oncology visits, particularly for patients undergoing treatment, the steps in recommending exercise do not require much time or skill by the oncology clinician and have been successfully integrated into cancer care follow-up visits.67 Macmillan Cancer Support (a cancer charity in the United Kingdom) has developed a guide to implementing exercise programming for those diagnosed with cancer.36 Although this “how-to” guide assumes access to the health care system in the United Kingdom, the document includes evidence-based instructions on implementation that are likely to be useful, and adaptable, to other countries with different health care delivery landscapes (eg, the United States).

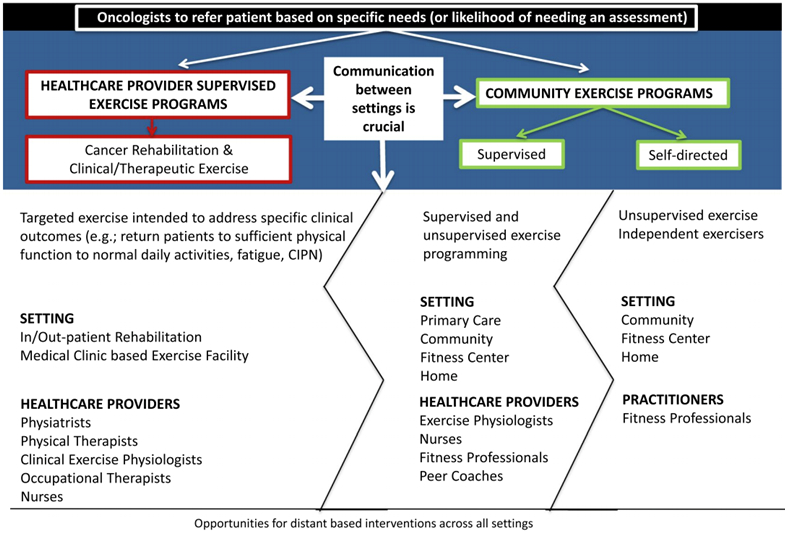

Types of Programming

In Figure 3, we have illustrated the range of possible programming to which patients can be referred during and after cancer treatment. The primary settings in which exercise can take place include: 1) HCP-supervised exercise programs (inpatient or outpatient ambulatory centers, public and private practice, in which exercise is overseen by licensed HCPs); and 2) community-based or home-based settings (specific, local, structured exercise programs in community or home settings in which individuals with cancer can participate). The selection of setting is based on medical complexity and the ability of the patient to self-manage their condition.

Figure 3.

Types of programs. CIPN indicates chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy.

First, however, it is important to clarify that patients are generally not referred once to one setting. The representation of the 2 types of programs described below are provided here as examples but, in truth, there is a sequential (and perhaps even iterative) trajectory to referring patients to one type and then another type of exercise or rehabilitative programming, given an aim of supporting patients throughout the cancer journey until the restoration of physical and emotional health and even beyond, for the balance of life. There is a need to clarify and simplify the process of getting patients into these programs by way of a referral from the oncology clinician. There is also a need to clarify how the practitioners in each setting can best refer to the other possible settings. This is denoted in Figure 3 by the jagged line between the 2 program types, which are described below.

HCP-Supervised Exercise Programming

An HCP-supervised exercise program offers services that are delivered in formal medical settings, such as inpatient and outpatient rehabilitation units, exercise facilities housed within medical settings, primary care settings, and palliative or hospice care units. Health care professionals (eg, physiatrists, physical therapists, clinical exercise physiologists, nurses, and/or occupational therapists) with expertise in the therapeutic use of exercise supervise these programs. Patients can self-refer, but referrals are typically made by a physician, with a patient’s clinical status often determining the need.68 HCP-supervised exercise programs seek to progressively improve the physical fitness and the physical function of the patient with cancer and the survivor at all points along the cancer continuum. Programs offered during treatment seek to minimize treatment-related side effects and functional decline. Posttreatment programs optimize recovery of physical functioning to a level that enables the survivor to engage in activities of daily living and to participate in the broader community, including long-term maintenance of regular exercise in community settings.68

Patients with cancer-related comorbidities or physical impairments, those at risk for developing these conditions, and those who require an individualized program to address a specific therapeutic outcome (ie, peripheral neuropathy) may be best managed by a referral to an HCP-supervised exercise program. Such programs are staffed by health care professionals with the appropriate knowledge and skills to deliver exercise programs safely and efficaciously. Highacuity cancer survivors may have needs in health domains (ie, physical, psychosocial, nutritional) beyond just physical rehabilitation.2,3,53,68 HCP-supervised exercise programs typically have qualified staff to meet these additional needs.

There has been much discussion of the proportion of cancer survivors who would need this type of HCPsupervised exercise program. A public health viewpoint might have clinicians refer every patient to (at the very least) a walking program. In contrast, clinicians who work in the setting of oncology rehabilitation have noted that even patients with metastatic breast cancer who are unable to ambulate are not referred to rehabilitation.69 To address the question of the proportion of survivors who might need supervised programming, a series of articles reviewed this issue in a variety of tumor sites, including breast, endometrial, head and neck, and colorectal cancer. All 4 articles examined the likelihood of needing a supervised program at 6 months after the end of active cancer therapy given a review of published expert guidelines for discerning the need for supervision.70 The proportion of endometrial, colorectal, head and neck, and breast cancer survivors who would need a supervised program were 80%, 58%, 60%, and 35%, respectively.53,70-73 Older age at diagnosis predicted the need for exercise supervision in survivors who had all 4 tumor sites. Predictors of the need for exercise supervision also varied by tumor site: higher body mass index in endometrial cancer survivors; a greater number of chronic disease comorbidities in colorectal cancer survivors; higher body mass index and receipt of radiation therapy among head and neck cancer survivors; and finally black race, treatment with chemotherapy, and treatment with radiation predicted the need for supervision among breast cancer survivors. Ultimately, it is likely that there is a subset of patients for whom the best approach is referral to outpatient rehabilitation for additional assessment and referral to appropriate programming. The challenge is determining who these patients are without overburdening oncology clinicians.

A minimal requirement for providing services in an HCP-supervised exercise program is the availability of qualified health care professionals with specialized knowledge in physical therapy or clinical exercise physiology, exercise prescriptions, and oncology (disease management, acute and late effects of treatment). An HCP-supervised exercise program should also have a structured process to identify those who are ready to be referred to community-based or home-based exercise programming or referred back to the oncology clinician for more specialized care. Clear communication among professionals who provide clinical exercise services and clinicians involved in cancer treatment should be ensured at all times.

An example of best practice in HCP-supervised exercise programs includes the ActivOnco51 program in Quebec, Canada. Common to these programs are a well-defined, multidisciplinary cancer care team; a person who guides the cancer survivor through the evaluation and treatment process; defined screening and evaluation processes that triage patients according to their medical status, rehabilitation needs, and exercise eligibility; and well-defined referral pathways to guide patient care and communications between all parties involved.

Community-Based Programs

Community-based programs, by definition, are not based in a formal medical setting (eg, hospital or rehabilitation center). Venues for these programs include local government municipal/community gyms; community halls, libraries, and leisure centers; local charities; and private gyms. Those referred to self-directed exercise programs may seek out community-based generic exercise classes and engage in outdoor activities such as walking or cycling. Patients connect to these programs either by self-referral or by referral from oncology clinicians. Many community programs involve screening and approval by the oncology clinician. The registry at exerciseismedicine.org/movingthroughcancer suggests that qualified fitness professionals, coaches, exercise physiologists, or volunteers mostly provide the exercise instruction in the community setting.

Community-based programs are generally perceived to be more accessible and affordable and reduce the barriers of distance, cost, and time compared with participation in HCP-supervised exercise programs.74,75 In several community settings, fitness instructors are trained specifically in cancer, including exercise guidelines and prescription, to supervise the exercise sessions/classes. Examples of such training courses designed by professionals with cancer exercise expertise include ACSM/ACS Certified Cancer Exercise Trainer (acsm.org/get-stay-certified/get-certified/ specialization/cet) and CanRehab cancer exercise specialist courses (canrehab.co.uk/fitness-workshops/). This skilled workforce is relatively inexpensive and accessible compared with physical or occupational therapists or clinical exercise physiologists.76 If neither is available, or if a patient is sufficiently mentally and physically able to participate in “regular” community exercise, directing patients to the most appropriate exercise opportunities (called “signposting” in the United Kingdom) can be an effective way of providing access to a wide range of generic activities in the community. However, ongoing monitoring and behavioral change support by a cancer exercise professional for those opting for generic activities are essential for success. Currently, there are more than 20 publications describing the implementation and, in many cases, the evaluation of community-based programs for patients with cancer and survivors in North America,77 Australia,78 and Northern Europe.79 Below, we describe the largest programs in the United Kingdom and the United States, respectively.

United Kingdom: MoveMore program

The UK cancer charity Macmillan Cancer Support worked with clinicians, service users, local decision makers, service providers, and academics to develop an exercise intervention delivered as part of an integrated care pathway. This program is initiated in the clinical setting and is followed by a behavior change–based intervention and utilization of exercise opportunities available in the community. MoveMore is not a typical, very structured, community-based program but rather aims to provide a variety of exercise opportunities in the community to suit the service user and thus ensure behavior change. MoveMore is based on guidelines stating that support should be provided for at least 1 year to bring about long-term behavior change, and the regularity and format of that support is informed by the individual’s personal needs and preferences.80 The exercise intervention options are varied and always include “closed” (ie, cancer-specific) options in gyms and community-funded facilities. Staff training for MoveMore is through the CanRehab cancer exercise specialist courses. Macmillan Cancer Support has provided 3 years of free programming for all people living with and beyond cancer, supporting the transition from local programs to a more sustainable model of care by providing resources and using lessons learned to influence provision across the United Kingdom.

United States: LIVESTRONG at the YMCA

The LIVESTRONG at the YMCA program adheres to ACSM guidelines for survivors engaging in exercise and has currently served over 60,600 people in 707 communities.81 The program consists of two 90-minute sessions per week for up to 12 weeks of small groups (6-16 participants) led by YMCA exercise instructors who have completed specific training before working in the program (ie, nationally accredited fitness trainer certification, multiple prerequisite training sessions, a 2-day in-person workshop, and a required online training on lymphedema). The program is free to survivors for at least 12 weeks, although some YMCAs allow repeated participation without cost. Instructors with strong relationship-building skills and expertise in exercise instruction are selected to become LIVESTRONG instructors. Instructors must maintain their certifications with qualified continuing education credits.

Both MoveMore and the LIVESTRONG at the YMCA programs have been independently evaluated and shown to be effective in significantly improving self-reported physical activity levels, quality-of-life physical function, and cardiorespiratory fitness.76,82

Implementation Issues

Capacity for Triage and Referral

The precipitously increasing demands placed on oncology clinicians represent an important consideration in advancing the systematic integration of exercise into cancer care. A key factor not resolvable at this time is one of ensuring that every exercise program is safe while still effective. The literature suggests that there are few adverse events from exercise in those living with and beyond cancer.2,9,37-39 However, the concern regarding keeping patients safe continues to be raised.22,23,26 In truth, adverse event reporting in the field of exercise oncology is not standardized. Event reporting should become standardized within exercise programs for people living with and beyond cancer to gain the trust of the oncology clinical community.

Above, we described the ideal scenario in which a multidisciplinary team would work alongside oncology clinicians in assessing, triaging, and referring patients to appropriate programming. Until that occurs, there is a need for simple systems whereby referrals can be made to the appropriate source to further assess and triage, much like what currently happens with psychosocial distress assessment and referrals.

This all occurs within the setting of demographic shifting to a more geriatric and multimorbid cancer population, as well as an expanding therapeutic arsenal and extended, late-stage survival that collectively tax the human and institutional resources devoted to cancer care. Furthermore, providers are being tasked with addressing multiple health conditions among patients with cancer in addition to exercise counseling (eg, fertility preservation, distress screening and management, and survivorship care planning). All of these health conditions are to be addressed during patient visits of shrinking duration. The challenging reality of an underresourced system confronting formidable demands is unlikely to change in the near term. Therefore, effective strategies are needed that provide support to oncology clinicians as they work to assist their patients in becoming more active after a cancer diagnosis.

Possible solutions could include better integration of electronic medical record (EMR) data. Current-generation EMRs have unprecedented capability to collect and synthesize diverse sources of information related to patients’ function, physical activity (self-report and from wearables), and adherence. By triangulating patient-reported outcome, performance, and clinical data, EMRs can populate algorithms that drive important dimensions of patient-EMR and provider-EMR interfaces, including alerts, messaging, document formatting, etc. Furthermore, with the increased use of online portals for patient-provider communication, these algorithms can trigger the automated delivery of educational materials for fitness and other activities directly to patients. The implications for directing survivors to needs-matched exercise and rehabilitation programming could be farreaching and impactful. However, the net pros and cons of relying on EMRs to automate aspects of care that have historically been restricted to in-person, clinic-based delivery are not known. There is a pressing need for implementation science research on incorporation of the 3 proposed steps (assess, advise, and refer) into oncology clinical care, with and beyond use of the EMR.

Identification/Awareness of HCP-Supervised and Community-Based Exercise Programming: The Need for a Registry

To refer to exercise programming requires knowledge of existing programming and trust in the quality and safety of that programming. In preparation for the 2018 ACSM Roundtable on exercise and cancer, we conducted an online survey of currently available exercise and rehabilitation programs worldwide. The survey was accessible via a public link. Respondents to the survey were recruited by emails to opinion leaders and organizations offering established programs and to researchers or clinicians identified through our professional network or based on prior scientific publications. In addition, we used snowball sampling: everyone receiving the email invitation was asked to forward the email to anyone they thought might be able to provide further information on available programs. Also, a call for respondents was published through professional networks, including the network for oncology/HIV of the World Confederation of Physical Therapy (International Physical Therapists for HIV/AIDS, Oncology, Hospice, and Palliative Care [IPTHOPE]), LIVESTRONG, ACSM, and the Commission on Accrediting Rehabilitation Facilities (CARF).

Of the 150 programs identified through this process, 90 are HCP-supervised exercise programs, and 60 are community programs. These programs are located in South America, North America, Europe, Asia, Oceania, and the Middle East. The ACSM is committed to keeping the registry updated with new programs on a regular basis, and it is now available online at exerciseismedicine.org/movingthroughcancer.

A screening process for entry of validated programs into the registry and automated annual confirmation from the key contact is under development. To be included in the registry, all programs will provide evidence that the interventionists are appropriately trained and certified in that locality (eg, ACSM anywhere, CanRehab in the United Kingdom). Programs will also provide information regarding location, cost, length, and frequency of sessions, as well as a detailed description of the program with regard to frequency, intensity, time, type, overload, and progression of exercise. Finally, all programs will document their emergency procedures and referrals to and from health care professionals. Programs run within health care settings will be asked to provide evidence of licensure. Programs will be reviewed annually, and lack of compliance will result in being removed from the registry.

The primary purpose of this registry is to provide a resource for clinicians and patients to more easily connect with HCP-supervised and community-based exercise programs for people living with and beyond cancer.2,10,37-39

Cost and Compensation

Sustainable coverage for exercise programming remains an ongoing challenge in all countries, as does clarifying which stakeholders will contribute. Some countries reimburse rehabilitative exercise programming under specific conditions (ie, Australia, Germany, the Netherlands). Underfunding, however, is common even in countries with government subsidies.83 For HCP-supervised exercise programs, thirdparty payers may offer partial coverage, yet gaps between insurance coverage and program costs may be insurmountable for many patients without institutional support. Funding for community-based programs is often vulnerable and shortterm.84 Some LIVESTRONG at the YMCA and UK-based MoveMore projects transition into fee-based models after set intervals. These user-pay models potentially provide a sustainable option provided there is committed baseline financial support from a community partner.

A potential barrier to consistent third-party coverage is marked variation in program costs. Inconsistencies can be partially explained by programs’ differing resource intensities. Center-based, clinician-supervised programs are notably more expensive. For example, OncoMove, a homebased, self-managed exercise program, costs $53 per patient, whereas OnTrack, a physical therapist-supervised, facility-based exercise program, costs $866 per patient.85 Both programs extend from the first chemotherapy visit to 3 weeks after the last chemotherapy visit. The expertise of the supervisory personnel also influences cost. The LIVESTRONG at the YMCA program costs less than OnTrack at $500 per patient, partially because of its reliance on exercise trainers rather than physical therapists.86

Reports suggest that resource-intensive programs are more likely to be cost-effective. A comparison of OncoMove and OnTrack found that OncoMove was unlikely to be cost-effective apart from very high willingness-to-pay thresholds. OnTrack, in contrast, had an incremental costeffectiveness ratio compared with usual care of €26,916 per quality-adjusted life-year, which falls within some endorsed willingness-to-pay thresholds.85

In addition, reports suggest that analyses including comprehensive costs, which capture reductions in health care utilization more consistently, favor resource-intensive and exercise-intensive programs. A randomized trial that compared high-intensity and low-intensity exercise programs found that the former were cost-effective, mostly due to significantly lower health care costs in the high-intensity exercise group.87 Several studies noted reductions in unplanned hospitalizations, lengths of stay, and emergency room visits among patients who participated in exercise programming.88,89 Although it is often assumed that multidimensional programs offer larger benefits, they are also inherently more expensive. It is as yet unclear whether such programs are more cost-effective compared with monodimensional programs.90 The association of greater value with more resource-intensive programs complicates the challenge facing provider organizations seeking to offer programming that will benefit their patients.85,89

Workforce Issues

The evidence base supporting referral to exercise programming during and after cancer treatment is not matched by a robust workforce prepared to triage, refer, coordinate care, and intervene with the 18.1 million new diagnoses annually or 44 million survivors currently alive worldwide.91 For the full benefits of exercise during and after cancer treatment to be realized, workforce development is needed on multiple fronts.

Oncology clinicians

Educational programs are needed to ensure that medical, surgical, and radiation oncologists; oncology nurse practitioners; nurses; and all other members of the cancer care team are cognizant of the value of exercise for their patients before, during, and after active cancer therapies.92 The ACSM is committed to developing and frequently updating an evidence review for oncology clinicians.

Health care professionals to deliver supervised exercise

Delivering high-quality care for individuals with cancer requires specialized knowledge and competency skills across the workforce of HCPs.93 The current system for education and training in the specialty practice of oncology exercise and rehabilitation, however, is more aligned with health care and medical continuing education programming rather than codified in standardized medical, nursing, and physical therapy curriculum content and board specialty training and certification. HCP disciplines such as clinical exercise physiologists, physical therapists, and physiatrists have welldescribed and standardized pathways for education and training that should be leveraged to improve knowledge and competency in oncology. Future opportunities to advance knowledge and skills in clinical exercise physiologists and physical therapists who deliver oncology exercise and rehabilitation include: standardizing entry-level curriculum content in oncology for degree and licensure,94 developing and expanding oncology rehabilitation residency programs,95 and developing cross-discipline clinical competencies that can be measured and translated into clinical practice.96

Although these efforts are unique to each health care profession’s scope of practice, there is a need for collaboration across disciplines to identify core, common oncology knowledge domains required to support safe and effective exercise programming and rehabilitation services. Workforce development for the health care professionals suited to lead oncology exercise programming will improve the density, credentialing, and visibility of these programs to meet the needs of those diagnosed with cancer during and beyond their treatment.

Community-based exercise professionals

In a community setting, the workforce most likely (knowingly or unknowingly) to work with the cancer population are fitness instructors/personal trainers based in locally funded community halls and gyms and in privately funded gyms and leisure centers. This workforce consists of 3 groups: staff directly employed by the community halls, gyms, and leisure centers; volunteers who work within this setting; and self-employed fitness instructors and personal trainers. There are few validated training pathways for preparing fitness instructors or volunteers to safely and effectively provide exercise programming to the cancer population in the community setting. One exception is in the United Kingdom, where a structured pathway to gaining qualification as a cancer exercise fitness instructor is available with all courses on the pathway validated and quality controlled by an overarching awarding body (the Chartered Institute for the Management of Sport and Physical Activity [CIMSPA]; cimspa.co.uk). Many qualified fitness instructors around the globe are part of a registry of exercise professionals. Individual countries manage their own exercise professional registries (eg, the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand). The umbrella organization for these registries of certified exercise professionals is called the International Coalition of Registers for Exercise Professionals; (icreps. org). Registries within specific countries can be accessed from the International Coalition of Registers for Exercise Professionals website.

The training company CanRehab has provided the Level 4 Cancer Exercise Training for >700 fitness instructors in the United Kingdom. A prerequisite to obtaining this certification is to hold a nationally accredited personal trainer/ exercise referral qualification, attend a 4-day training course, complete a case study submission, and pass a practical and written examination (>70%). Medical and allied health care professionals have endorsed the course. Most volunteers working with clients with cancer in the United Kingdom go through a standard core cancer awareness training program provided by Macmillan Cancer Support for all its volunteers. The rough equivalent to the CanRehab training and certification in the United States is a professional certification developed by the ACSM in 2008 in partnership with the ACS for exercise professionals seeking to provide safe, effective exercise programming to those who have been diagnosed with cancer (ACSM/ACS Cancer Exercise Trainer Certification). The certification is undergoing an update in 2019.

Exercise Is Medicine in Oncology—A Call to Action

Overcoming the above-noted barriers and making exercise assessment, advice and referral a standard practice within clinical oncology will require action from multiple stakeholders.

Oncology Clinicians

Assess physical activity for all patients at regular intervals, continuously along the cancer continuum. Advise patients to move more and sit less. Refer to local HCP-supervised and community or home programs as appropriate. Develop a process to incorporate these steps into the standard care of oncology patients.

Policy Makers

Develop policies, programs, and initiatives that facilitate the translation and funding (reimbursement) for the implementation of clinical and community exercise programming across all cancer diagnoses and at all points on the cancer continuum. There are many documented benefits of exercise during and after cancer treatment.10 A drug with a similar benefit profile would likely be prescribed broadly.

Researchers

Adapt effective interventions for community-based and home-based settings. Conduct implementation science and health services research on clinical and community exercise during and after active cancer care to drive improvements in infrastructure, reimbursement, and other policies that will make exercise standard practice in oncology.

Clinical Educators

Expand physical activity education in the training of all HCPs and social workers who are or will be a part of the oncology workforce. Develop the workforce for clinical and community exercise practitioners in oncology.

Health Care Providers (Physical Therapists, Clinical Exercise Professionals)

Seek additional training to meet the unique needs of patients with cancer and cancer survivors. Demand new curriculum development to meet this unmet educational need.

Mainstream Health and Fitness Industry

Although LIVESTRONG at the YMCA and the MoveMore program form successful models, they are not ubiquitous. There are many places in the United States and beyond where there are no available exercise programs for patients with cancer and cancer survivors. In 2014, revenues in the US fitness industry topped $24 billion, and memberships are increasing steadily.97 The industry has noted that smaller niche gyms gather cult followings. At 16 million survivors in the United States, cancer survivors might be prevalent enough to form a niche (or 2). The industry could benefit from, and benefit, patients with cancer and cancer survivors with high-quality programming to which oncology clinicians could make referrals. Although this evaluation is admittedly United States–centric, the facts are likely easily replicated around the world.

Oncology Patients and Survivors

Oncology patients and cancer survivors have a powerful voice in shaping oncology care. Multiple funding agencies now require patient advocates on projects to ensure that the voice of the patient is considered. If patient advocates spoke with one voice in asking for exercise assessment, advice, and referral to be standard practice, it would facilitate forward motion toward this goal.

Summary

The exponential growth of exercise oncology research has driven the need for revised cancer exercise guidelines10 and a roadmap for oncology clinicians to follow to improve physical and psychological outcomes from cancer diagnosis and for the balance of life. This call to action details pathways for exercise programming (clinical, community, and selfdirected) tailored to the different levels of support and intervention needed by a given patient with cancer or cancer survivor. Preserving activity and functional ability is integral to cancer care, and oncology clinicians are key to providing these referrals. At the very least, oncology clinicians should:

Assess current physical activity at regular intervals;

Advise patients with cancer on their current and desired level of physical activity and convey the message that moving matters; and

Refer patients to appropriate exercise programs or to the appropriate health care professionals who can evaluate and refer to exercise.

Upon full development of the exercise oncology workforce, experts in cancer rehabilitation and exercise oncology recommend further changes to oncology clinical practice. These aspirations would elevate the potential to address the rehabilitative, exercise, and functional goals and outcomes during and after treatment.

Current practice is failing those diagnosed with cancer. This call to action for oncology clinicians, policy makers, researchers, educators, patients, and the health and fitness industry has the potential to transform health and well-being from cancer diagnosis, through treatment, and for the balance of life.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

This manuscript is endorsed by the following organizations: American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, American Cancer Society, American College of Lifestyle Medicine, American College of Sports Medicine, American Physical Therapy Association, Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology, Commission on Accreditation of Rehabilitation Facilities, Exercise and Sports Science Australia, German Union for Health Exercise and Exercise Therapy, Macmillan Cancer Support, National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Royal Dutch Society for Physical Therapy, Society for Behavioral Medicine, and Sunflower Wellness.

Footnotes

Disclosures: Bernardine M. Pinto reports grant support from the National Cancer Institute during the conduct of the study. Lynn H. Gerber reports funding from AAPMR and FPMR. Nicole L. Stout reports travel expenses from the American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine for meeting attendance during the conduct of the study and personal fees from BSN Medical, Survivorship Solutions, and Zansors LLC outside the submitted work. Charles E. Matthews effort was supported by the National Institutes of Health Intramural Research Program. The remaining authors made no disclosures. The American College of Sports Medicine International Multidisciplinary Roundtable was funded by the American College of Sports Medicine, the American Cancer Society, the American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, the American Physical Therapy Association, Macmillan Cancer Support, the Royal Dutch Society for Physiotherapy, the German Union for Health Exercise and Exercise Therapy, Exercise and Sports Science Australia, the Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology, and Sunflower Wellness.

Contributor Information

Kathryn H Schmitz, Department of Public Health Sciences, Penn State College of Medicine, Hershey, Pennsylvania.

Anna M Campbell, School of Applied Sciences, Edinburgh Napier University, Edinburgh, United Kingdom.

Martijn M Stuiver, Center for Quality of Life, Netherlands Cancer Institute, Amsterdam, The Netherlands; ACHIEVE, Faculty of Health, Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences, Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Department of Clinical Epidemiology, Biostatistics, and Bioinformatics, Amsterdam UMC, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Bernadine M Pinto, College of Nursing, University of South Carolina, Columbia, South Carolina.

Anna L Schwartz, School of Nursing, Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, Arizona.

G Stephen Morris, Department of Physical Therapy, Wingate University, Wingate, North Carolina.

Jennifer A Ligibel, Division of Women’s Cancers, Dana Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, Massachusetts.

Andrea Cheville, Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota.

Daniel A Galvao, Exercise Medicine Research Institute, Edith Cowan University, Joondalup, Western Australia, Australia.

Catherine M Alfano, Survivorship, American Cancer Society, Atlanta, Georgia.

Alpa V Patel, Behavioral and Epidemiology Research, American Cancer Society, Atlanta, Georgia.

Trisha Hue, Data and Information Management, University of California at San Francisco, San Francisco, California.

Lynn H Gerber, Health Administration and Policy, George Mason University, Fairfax, Virginia.

Robert Sallis, Family Medicine, Kaiser Permanente Southern California, Pasadena, California.

Niraj J Gusani, Department of Surgery, Penn State Cancer Institute, Hershey, Pennsylvania.

Nicole L Stout, Rehabilitation Medicine Department, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland.

Leighton Chan, Rehabilitation Medicine Department, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland.

Fiona Flowers, Community Settings, Macmillan Cancer Support, London, United Kingdom.

Colleen Doyle, Department of Cancer Control, American Cancer Society, Atlanta, Georgia.

Susan Helmrich, Patient Advocate, Berkeley, California.

William Bain, Sunflower Wellness, San Francisco, California.

Jonas Sokolof, Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, New York University Langone Medical Center, New York, New York.

Kerri M. Winters-Stone, Knight Cancer Institute, School of Nursing, Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, Oregon

Kristin L Campbell, Department of Physical Therapy, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada.

Charles E Matthews, Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, Maryland.

References

- 1.Rock CL, Doyle C, Demark-Wahnefried W, et al. Nutrition and physical activity guidelines for cancer survivors. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:242–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schmitz KH, Courneya KS, Matthews C, et al. American College of Sports Medicine roundtable on exercise guidelines for cancer survivors. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010;42:1409–1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hayes SC, Newton RU, Spence RR, Galvao DA. The Exercise and Sports Science Australia position statement: exercise medicine in cancer management. J Sci Med Sport. Published online May 10, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2019.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Segal R, Zwaal C, Green E, et al. Exercise for people with cancer: a clinical practice guideline. Curr Oncol. 2017;24:40–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cormie P, Atkinson M, Bucci L, et al. Clinical Oncology Society of Australia position statement on exercise in cancer care. Med J Aust. 2018;209:184–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patel AV, Friedenreich CM, Moore SC, et al. American College of Sports Medicine roundtable report on physical activity, sedentary behavior, and cancer prevention and control. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2019; In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. Diet, Nutrition, Physical Activity and Cancer: A Global Perspective. Continuous Update Project Expert Report. World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 8.2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee. 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Scientific Report. US Department of Health and Human Services; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mayer DK, Terrin NC, Menon U, et al. Health behaviors in cancer survivors. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2007;34:643–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Campbell KL, Winters-Stone K, Wiskemann J, et al. Exercise guidelines for cancer survivors: consensus statement from international multidisciplinary roundtable. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2019; In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Denlinger CS, Ligibel JA, Are M, et al. Survivorship: healthy lifestyles, version 2.2014. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2014;12: 1222–1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blanchard CM, Courneya KS, Stein K, American Cancer Society’s SCS, II. Cancer survivors’ adherence to lifestyle behavior recommendations and associations with health-related quality of life: results from the American Cancer Society’s SCS-II. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2198–2204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Webb J, Foster J, Poulter E. Increasing the frequency of physical activity very brief advice for cancer patients. Development of an intervention using the behaviour change wheel. Public Health. 2016;133:45–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Department of Health-Quality Health. Quality of Life of Cancer Survivors in England—Report on a Pilot Survey Using Patient Reported Outcome Measures (PROMS). Crown Copyright; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hardcastle SJ, Maxwell-Smith C, Kamarova S, Lamb S, Millar L, Cohen PA. Factors influencing non-participation in an exercise program and attitudes towards physical activity amongst cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26: 1289–1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kirkham AA, Van Patten CL, Gelmon KA, et al. Effectiveness of oncologist-referred exercise and healthy eating programming as a part of supportive adjuvant care for early breast cancer. Oncologist. 2018;23: 105–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nyrop KA, Deal AM, Williams GR, Guerard EJ, Pergolotti M, Muss HB. Physical activity communication between oncology providers and patients with early-stage breast, colon, or prostate cancer. Cancer. 2016;122:470–476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Demark-Wahnefried W, Peterson B, McBride C, Lipkus I, Clipp E. Current health behaviors and readiness to pursue life-style changes among men and women diagnosed with early stage prostate and breast carcinomas. Cancer. 2000;88:674–684. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anderson AS, Steele R, Coyle J. Lifestyle issues for colorectal cancer survivors— perceived needs, beliefs and opportunities. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21:35–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Williams K, Beeken RJ, Wardle J. Health behaviour advice to cancer patients: the perspective of social network members. Br J Cancer. 2013;108:831–835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hardcastle SJ, Kane R, Chivers P, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and practice of oncologists and oncology health care providers in promoting physical activity to cancer survivors: an international survey. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26:3711–3719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nadler M, Bainbridge D, Tomasone J, Cheifetz O, Juergens RA, Sussman J. Oncology care provider perspectives on exercise promotion in people with cancer: an examination of knowledge, practices, barriers, and facilitators. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25:2297–2304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ligibel JA, Jones LW, Brewster AM, et al. Oncologists’ attitudes and practice of addressing diet, physical activity, and weight management with patients with cancer: findings of an ASCO survey of the oncology workforce. J Oncol Pract. 2019;15:e520–e528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smaradottir A, Smith AL, Borgert AJ, Oettel KR. Are we on the same page? Patient and provider perceptions about exercise in cancer care: a focus group study. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2017;15: 588–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cheville AL, Dose AM, Basford JR, Rhudy LM. Insights into the reluctance of patients with late-stage cancer to adopt exercise as a means to reduce their symptoms and improve their function. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012;44:84–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fong AJ, Faulkner G, Jones JM, Sabiston CM. A qualitative analysis of oncology clinicians’ perceptions and barriers for physical activity counseling in breast cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26:3117–3126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lobelo F, Stoutenberg M, Hutber A. The Exercise Is Medicine Global Health Initiative: a 2014 update. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48:1627–1633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.James EL, Ewald BD, Johnson NA, et al. Referral for expert physical activity counseling: a pragmatic RCT. Am J Prev Med. 2017;53:490–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shuval K, Leonard T, Drope J, et al. Physical activity counseling in primary care: insights from public health and behavioral economics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67:233–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Glynn TJ, Manley MW. How to Help Your Patients Stop Smoking. A National Cancer Institute Manual for Physicians. US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute; 1989. NIH publication 89-3964. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heath GW, Kolade VO, Haynes JW. Exercise Is Medicine: a pilot study linking primary care with community physical activity support. Prev Med Rep. 2015;2:492–497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Trilk JL, Phillips EM. Incorporating ‘Exercise Is Medicine’ into the University of South Carolina School of Medicine Greenville and Greenville Health System. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48:165–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ball TJ, Joy EA, Gren LH, Cunningham R, Shaw JM. Predictive validity of an adult physical activity “vital sign” recorded in electronic health records. J Phys Act Health. 2016;13:403–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ball TJ, Joy EA, Gren LH, Shaw JM. Concurrent validity of a self-reported physical activity “vital sign” questionnaire with adult primary care patients. Prev Chronic Dis. 2016;13:E16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Coleman KJ, Ngor E, Reynolds K, et al. Initial validation of an exercise “vital sign” in electronic medical records. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2012;44:2071–2076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Foster J, Worbey S, Chamberlin K, Horlock R, Marsh T. Integrating Physical Activity into Cancer Care: Evidence and Guidance. MacMillan Cancer Support; macmillan.org.uk/_image s/integrating-physical-activity-into-cancer-care-evidence-and-guidance_tcm9-339684.pdf. Accessed August 25, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schmitz K, Holtzman J, Courneya K, Masse L, Duval S, Kane R. Controlled physical activity trials in cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:1588–1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Speck RM, Courneya KS, Masse LC, Duval S, Schmitz KH. An update of controlled physical activity trials in cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cancer Surviv. 2010;4:87–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Singh B, Spence RR, Steele ML, Sandler CX, Peake JM, Hayes SC. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the safety, feasibility, and effect of exercise in women with stage II+ Breast cancer. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2018;99:2621–2636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lobelo F, Rohm Young D, Sallis R, et al. Routine assessment and promotion of physical activity in healthcare settings: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018;137:e495–e522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Agasi-Idenburg CS, Zuilen MK, Westerman MJ, Punt CJA, Aaronson NK, Stuiver MM. “I am busy surviving”—views about physical exercise in older adults scheduled for colorectal cancer surgery. J Geriatr Oncol. Published online May 20, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.igo.2019.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ten Tusscher MR, Groen WG, Geleijn E, et al. Physical problems, functional limitations, and preferences for physical therapist-guided exercise programs among Dutch patients with metastatic breast cancer: a mixed methods study. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27:3061–3070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Knobf MT, Jeon S, Smith B, et al. The Yale Fitness Intervention Trial in female cancer survivors: cardiovascular and physiological outcomes. Heart Lung. 2017;46:375–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bluethmann SM, Vernon SW, Gabriel KP, Murphy CC, Bartholomew LK. Taking the next step: a systematic review and meta-analysis of physical activity and behavior change interventions in recent post-treatment breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2015;149:331–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Buffart LM, Kalter J, Sweegers MG, et al. Effects and moderators of exercise on quality of life and physical function in patients with cancer: an individual patient data meta-analysis of 34 RCTs. Cancer Treat Rev. 2017;52:91–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sweegers MG, Altenburg TM, Brug J, et al. Effects and moderators of exercise on muscle strength, muscle function and aerobic fitness in patients with cancer: a meta-analysis of individual patient data. Br J Sports Med. 2019;53:812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]