Abstract

Background

There are limited data on the outcomes of adults with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) and atrial fibrillation (AF). The objectives were to (i) examine associations between AF, 30‐day thromboembolic events and mortality in adults with COVID‐19 and (ii) examine associations between COVID‐19, 30‐day thromboembolic events and mortality in adults with AF.

Methods

A study was conducted using a global federated health research network. Adults aged ≥50 years who presented to 41 participating healthcare organizations between 20 January 2020 and 1 September 2020 with COVID‐19 were included.

Results

For the first objective, 6589 adults with COVID‐19 and AF were propensity score matched for age, gender, race, and comorbidities to 6589 adults with COVID‐19 without AF. The survival probability was significantly lower in adults with COVID‐19 and AF compared to matched adults without AF (82.7% compared to 88.3%, Log‐Rank test P < .0001; Risk Ratio (95% confidence interval) 1.61 (1.46, 1.78)) and risk of thromboembolic events was higher in patients with AF (9.9% vs 7.0%, Log‐Rank test P < .0001; Risk Ratio (95% confidence interval) 1.41 (1.26, 1.59)). For the second objective, 2454 adults with AF and COVID‐19 were propensity score matched to 2454 adults with AF without COVID‐19. The survival probability was significantly lower for adults with AF and COVID‐19 compared to adults with AF without COVID‐19, but there was no significant difference in risk of thromboembolic events.

Conclusions

AF could be an important risk factor for short‐term mortality with COVID‐19, and COVID‐19 may increase risk of short‐term mortality amongst adults with AF.

Keywords: atrial fibrillation, coronavirus‐2019, COVID‐19, mortality, thromboembolic events

Study of 6,589 adults with COVID‐19 and atrial fibrillation propensity score matched to 6,589 adults with COVID‐19 without atrial fibrillation. After 1:1 propensity score matching, the cohorts with and without atrial fibrillation were well balanced. Survival probability within 30‐days was significantly lower in COVID‐19 patients with atrial fibrillation compared to matched patients (82.7% compared to 88.3%, Log‐Rank test p<0.0001)

1. INTRODUCTION

The World Health Organisation announced coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) as a public health emergency on 30 January 2020. 1 As of 5 October 2020, over 35 million cases of COVID‐19 and over one million deaths with COVID‐19 had been reported worldwide. 2 Preexisting cardiovascular disease has been shown to be a risk factor for adverse outcomes and mortality in adults with COVID‐19. 3

Some evidence suggests cardiac arrhythmias may be common in adults with COVID‐19, such as in a hospitalised cohort of 138 adults with COVID‐19 in China, cardiac arrhythmias were reported in 16.7%, 4 but details of these arrhythmias including preexisting arrhythmias is not known. A study of 99 individuals hospitalised with COVID‐19 in Northern Italy suggested atrial fibrillation (AF) was more common in patients who died (46.2% vs 15.1%), but this was not adjusted for other characteristics of the patients. 5 Furthermore, AF increases the risk of ischemic stroke fivefold, 6 and increasing evidence also points to a propensity to thrombosis and thrombosis‐related complications in adults with COVID‐19. 7

There is a paucity of data available on the outcomes of adults with COVID‐19 and AF, and it is unclear if AF impacts risk of mortality with COVID‐19 after accounting for other comorbidities associated with AF, such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and cerebrovascular disease. The objectives of this study were to (i) examine associations between AF and risk of 30‐day mortality, and risk of thromboembolic events within 30 days for patients with COVID‐19 and to (ii) examine associations between COVID‐19 and risk of 30‐day mortality, and 30‐day thromboembolic events for patients with AF. For the first objective, we compared 30‐day all‐cause mortality and 30‐day incidence of thromboembolic events in two cohorts with COVID‐19, with and without a history of AF. For the second objective, we examined 30‐day all‐cause mortality and 30‐day incidence of thromboembolic events for patients with AF and COVID‐19 compared to a historical control group with AF without COVID‐19. For both objectives we used propensity score matching to balance demographic characteristics and comorbidities between the groups.

2. METHODS

A study was performed by utilising TriNetX which is a global federated health research network which provides researchers with access to statistics on electronic medical records (EMRs) from participating healthcare organisations, predominately in the United States (US). The healthcare organisations include academic medical centres, specialty physician practices and community hospitals.

For the first study objective, patients within the TriNetX research network aged ≥50 years with COVID‐19 recorded in their EMRs between 20 January 2020 and 1 September 2020 were included. For the second study objective, cases were included if they were aged ≥50 years with COVID‐19 and AF recorded in EMRs between 20 January 2020 and 1 September 2020, and historical controls were included if they were aged ≥50 years with AF recorded in EMRs between 20 January 2019 and 1 September 2019. We only included patients with a first‐recording of AF in EMRs during the specified time periods. AF was determined by searching for the ICD‐10‐CM code I48 (AF or flutter) in the EMRs.

The searches were run in TriNetX on 1 October 2020 which allowed for at least 30 days follow‐up for all participants from the time COVID‐19 was recorded in their EMRs (first objective) or from when AF was recorded in their EMRs (second objective). When the searchers were run, there were 41 participating healthcare organisations within the TriNetX research network.

The start date was chosen as 20 January 2020 because COVID‐19 was first confirmed in the US on this date, and the TriNetX network is predominately US‐based. 8 COVID‐19 was identified using criteria provided by TriNetX based on Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) coding guidelines. 9 COVID‐19 status was determined using codes in electronic medical records or a positive test result identified with COVID‐19‐specific laboratory codes. Specifically, COVID‐19 was identified by one or more of the following International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision and Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD‐10‐CM) codes in the electronic medical records of the patients: U07.1 COVID‐19; U07.2 COVID‐19, virus not identified; B97.29 Other coronavirus as the cause of diseases classified elsewhere; B34.2 Coronavirus infection, unspecified; or a positive test result identified with COVID‐19‐specific laboratory Logical Observation Identifiers Names and Codes (LOINCs). Patients with ICD‐9 code 079.89 were excluded because this code may still be used code for >50 viral infections.

Thromboembolic events included in analyses were cerebral infarction (ICD‐10‐CM code: I63), transient cerebral ischemic attacks and related syndromes (G45), pulmonary embolism (I26), arterial embolism and thrombosis (I74), and other venous embolism and thrombosis (I82).

2.1. Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were completed on the TriNetX online research platform. Baseline characteristics were compared with chi‐squared tests for categorical variables and independent‐sample t tests for continuous variables. The TriNetX platform was used to run 1:1 propensity score matching using logistic regression. The platform uses nearest‐neighbor matching with a tolerance level of 0.01 and difference between propensity scores ≤0.1. The following variables were included in propensity score matching: age, gender, race, and the following health conditions identified from ICD‐10‐CM codes in EMRs hypertensive diseases, ischemic heart diseases, heart failure, cerebrovascular diseases, diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, diseases of the respiratory system, diseases of the digestive system, diseases of the nervous system, and neoplasms. These conditions were chosen because they are established risk factors for AF or mortality and were significantly different between the cohorts with and without AF.

For the first study objective, Kaplan‐Meier survival curves for 30‐day mortality and 30‐day incident thromboembolic events by COVID‐19 status were produced with log‐rank tests after propensity score matching. Risk Ratios with 95% confidence intervals for 30‐day mortality and 30‐day incident thromboembolic events were also calculated after propensity score matching. Statistical significance was prespecified as P < .05.

2.2. Data access from TriNetX

To gain access to the data in the TriNetX research network, a request can be made to TriNetX (https://live.trinetx.com), but costs may be incurred, a data sharing agreement would be necessary, and no patient identifiable information can be obtained.

2.3. Ethical approval

As a federated network, research studies using the TriNetX research network do not require ethics approvals as no patient identifiable identification is received.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Comparison of individuals with COVID‐19, with and without AF

In total, 68 975 people were included who were aged ≥50 years and had COVID‐19 coded in their EMRs using the specified codes and time period described in the Methods. Of these patients, 10.3% (n = 7109) had AF identified from their EMRs. The cohort with AF were significantly older and had a significantly higher proportion of males, white patients and all comorbid conditions included in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics of the populations aged ≥ 50 years with COVID‐19 and with and without atrial fibrillation or flutter before and after propensity‐score matching

| Initial populations | Propensity score matched populations | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COVID‐19 and no AF (n = 61 866) | COVID‐19 and AF (n = 7109) | P‐value | COVID‐19 and no AF (n = 6589) | COVID‐19 and AF (n = 6589) | P‐value | |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 64.2 (10.7) | 74.1 (11.0) | <0.001 | 73.3 (10.9) | 73.6 (10.9) | 0.16 |

| Femalea a | 53.6 (33 189) | 44.9 (3189) | <0.001 | 45.2 (2978) | 45.6 (3002) | 0.67 |

| Race b | ||||||

| White | 55.1 (34 104) | 63.6 (4520) | <0.001 | 62.9 (4143) | 62.6 (4126) | 0.56 |

| Black or African American | 23.2 (14 348) | 19.6 (1396) | <0.001 | 22.1 (1457) | 20.6 (1358) | 0.04 |

| Asian | 2.4 (1499) | 1.6 (111) | 0.001 | 1.5 (99) | 1.6 (105) | 0.67 |

| Native Hawaiian/other Pacific Islander | 0.3 (202) | 0.3 (18) | 0.30 | 0.2 (16) | 0.2 (16) | 1.00 |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 0.5 (291) | 0.3 (21) | 0.04 | 0.3 (17) | 0.3 (21) | 0.52 |

| Unknown | 18.4 (11 390) | 14.7 (1042) | <0.001 | 12.9 (851) | 14.6 (962) | 0.01 |

| Hypertensive diseases | 42.3 (26 185) | 79.1 (5620) | <0.001 | 79.3 (5223) | 77.4 (5101) | 0.01 |

| Ischemic heart diseases | 12.6 (7824) | 49.6 (3523) | <0.001 | 46.5 (3062) | 46.1 (3038) | 0.68 |

| Heart Failure | 6.7 (4145) | 44.5 (3162) | <0.001 | 37.5 (2474) | 40.1 (2643) | 0.03 |

| Cerebrovascular diseases | 8.2 (5090) | 30.5 (2169) | <0.001 | 27.0 (1776) | 27.4 (1804) | 0.58 |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 22.1 (13 681) | 41.7 (2963) | <0.001 | 41.7 (2746) | 40.9 (2692) | 0.34 |

| Chronic Kidney Disease | 9.5 (5857) | 35.3 (2509) | <0.001 | 32.4 (2137) | 32.5 (2142) | 0.93 |

| Diseases of the respiratory system | 54.2 (33 542) | 80.3 (5708) | <0.001 | 80.7 (5315) | 79.0 (5205) | 0.02 |

| Diseases of the digestive system | 42.1 (26 041) | 68.3 (4856) | <0.001 | 67.9 (4438) | 66.7 (4392) | 0.39 |

| Diseases of the nervous system | 38.1 (24 189) | 67.9 (4825) | <0.001 | 66.8 (4403) | 65.9 (4344) | 0.28 |

| Neoplasms | 24.7 (15 287) | 39.7 (2820) | <0.001 | 37.9 (2497) | 38.2 (2519) | 0.69 |

Values are % (n) unless otherwise stated. Baseline characteristics were compared using a chi‐squared test for categorical variables and an independent‐sample t test for continuous variables.

AF, atrial fibrillation; COVID‐19, coronavirus disease 2019; SD, standard deviation.

Sex unknown for 0.1% of patients.

Data are taken from structured fields in the electronic medical record systems of the participating healthcare organisations, therefore, there may be regional or country‐specific differences in how race categories are defined.

After propensity score matching, there were 6589 individuals included in both cohorts, and the cohorts were better balanced on age, gender and race, apart from proportions of patients identified Black or African American or unknown race which remained significantly different. The cohorts were also better balanced on the included comorbid conditions. Diseases of the respiratory system and hypertensive disease became more prevalent for the cohort without AF (80.7% vs 79.0%, P = .02 for diseases of the respiratory system and 79.3% vs 77.4%, P = .01 for hypertensive diseases). History of heart failure was better balanced between the groups after propensity score matching, but remained statistically significantly higher for the cohort with AF (40.1% vs 37.5%, P = .03).

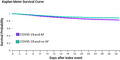

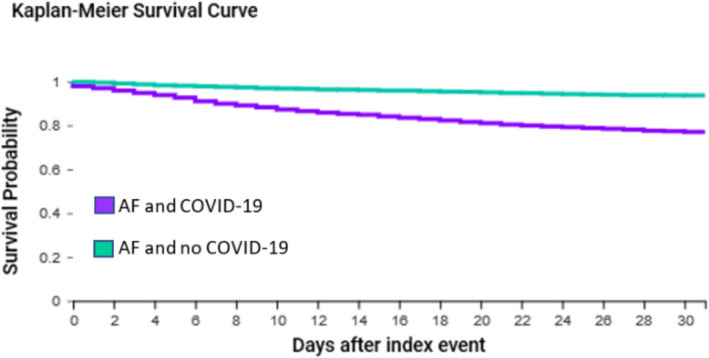

After propensity score matching, Kaplan‐Meier analysis showed that 30‐day survival probability after COVID‐19 was significantly lower in adults with AF compared to those without AF (82.7% compared to 88.3%, Log‐Rank test P < .0001, Figure 1; risk ratio (95% confidence interval) 1.61 (1.46, 1.78)). The risk of developing thromboembolic events within 30 days after COVID‐19 was significantly higher for patients with AF compared to those without AF (9.9% vs 7.0%, Log‐Rank test P < .0001, Figure S1; risk ratio (95% confidence interval) 1.41 (1.26, 1.59)).

FIGURE 1.

Kaplan‐Meier survival curve of 30‐day mortality for patients aged ≥ 50 years with COVID‐19 with and without history of AF after propensity score matching. AF: Atrial fibrillation. Propensity score matched for age, gender, race, and history of hypertensive diseases, ischemic heart diseases, heart failure, cerebrovascular diseases, diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, diseases of the respiratory system, diseases of the digestive system, diseases of the nervous system, and neoplasms. Log‐Rank test: P < .0001

3.2. Comparison of individuals with AF, with and without COVID‐19

Of the participating sites within the TriNetX network, 99 881 patients met the inclusion criteria for historical controls with newly reported AF and 2455 patients met the inclusion criteria for cases with newly reported AF and COVID‐19. Compared to cases with COVID‐19 and AF, historical controls with AF without COVID‐19 were older, had a higher proportion of females and people who identified as white, and had a lower proportion of people with comorbid health conditions including heart failure, cerebrovascular diseases, diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, diseases of the respiratory system, digestive system, and nervous system (Table 2). There were no statistically significant differences in the history of hypertensive diseases, ischemic heart diseases or neoplasms between the cases and controls. After 1:1 propensity score matching, there were 2454 cases and 2454 historical controls and they were well balanced for age, gender, race, and all health conditions included in the propensity score matching (all P > .05).

TABLE 2.

Baseline characteristics of the populations aged ≥ 50 years with newly diagnosed atrial fibrillation or flutter and COVID‐19 (cases) or newly diagnosed atrial fibrillation or flutter and no COVID‐19 (historical controls) before and after propensity score matching

| Initial populations | Propensity score matched populations | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AF and COVID‐19 (n = 2455) | AF and no COVID‐19 (n = 99 881) | P‐value | AF and COVID‐19 (n = 2454) | AF and no COVID‐19 (n = 2454) | P‐value | |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 73.2 (11.1) | 73.8 (10.5) | 0.004 | 73.2 (11.1) | 73.1 (10.9) | 0.66 |

| Female a | 40.5 (995) | 43.8 (43 765) | 0.001 | 40.5 (995) | 40.3 (988) | 0.84 |

| Race b | ||||||

| White | 58.4 (1433) | 79.7 (79 614) | <0.001 | 58.4 (1433) | 59.8 (1468) | 0.31 |

| Black or African American | 22.9 (563) | 8.9 (8868) | <0.001 | 22.9 (562) | 22.5 (553) | 0.76 |

| Asian | 1.6 (40) | 1.5 (1520) | 0.67 | 1.6 (40) | 1.3 (33) | 0.41 |

| Native Hawaiian/other Pacific Islander | 0.4 (10) | 0.1 (120) | <0.001 | 0.4 (10) | 0.4 (10) | 1.00 |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 0.4 (11) | 0.3 (259) | 0.07 | 0.4 (11) | 0.4 (11) | 1.00 |

| Unknown | 16.7 (409) | 9.5 (9529) | <0.001 | 16.7 (409) | 16.1 (395) | 0.59 |

| Hypertensive diseases | 66.6 (1635) | 67.7 (67 612) | 0.25 | 66.6 (1635) | 66.7 (1638) | 0.93 |

| Ischemic heart diseases | 36.3 (892) | 35.4 (35 347) | 0.33 | 36.3 (892) | 34.9 (857) | 0.30 |

| Heart Failure | 31.3 (768) | 27.0 (26 947) | <0.001 | 31.3 (768) | 30.6 (752) | 0.62 |

| Cerebrovascular diseases | 19.4 (476) | 16.2 (16 162) | <0.001 | 19.4 (476) | 18.8 (462) | 0.61 |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 35.8 (879) | 28.0 (27 920) | <0.001 | 35.8 (878) | 33.1 (813) | 0.051 |

| Chronic Kidney Disease | 26.6 (652) | 18.7 (18 641) | <0.001 | 26.5 (651) | 25.6 (629) | 0.47 |

| Diseases of the respiratory system | 75.6 (1856) | 46.0 (45 926) | <0.001 | 75.6 (1855) | 76.6 (1880) | 0.40 |

| Diseases of the digestive system | 53.1 (1304) | 44.2 (44 127) | <0.001 | 53.1 (1304) | 53.1 (1303) | 0.98 |

| Diseases of the nervous system | 51.7 (1270) | 67.9 (4825) | <0.001 | 51.7 (1270) | 52.4 (1285) | 0.67 |

| Neoplasms | 25.9 (635) | 25.1 (25 083) | 0.40 | 25.9 (635) | 25.1 (615) | 0.51 |

Values are % (n) unless otherwise stated. Baseline characteristics were compared using a chi‐squared test for categorical variables and an independent‐sample t test for continuous variables.

AF, atrial fibrillation; COVID‐19, coronavirus disease 2019; SD, standard deviation.

Sex unknown for 0.1% of patients.

Data are taken from structured fields in the electronic medical record systems of the participating healthcare organisations, therefore, there may be regional or country‐specific differences in how race categories are defined.

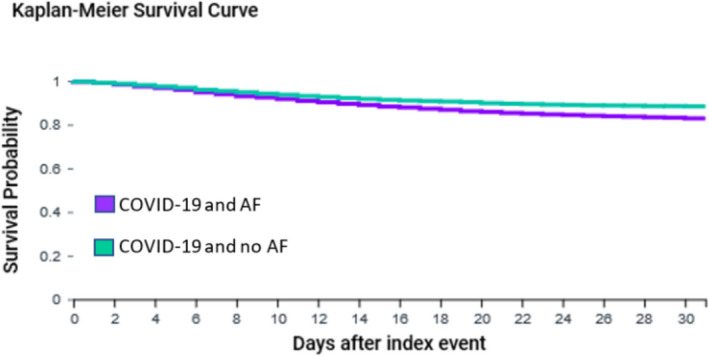

After propensity score matching, Kaplan‐Meier analysis showed that 30‐day survival probability after newly reported AF was significantly lower in adults with COVID‐19 compared to historical controls (80.0% compared to 93.6%, Log‐Rank test P < .0001, Figure 2; Risk Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) 3.63 (3.02, 4.36)). The risk of developing thromboembolic events within 30 days after newly reported AF was not statistically significantly different for adults with COVID‐19 compared to historical controls (14.5% vs 13.7%, Log‐Rank text P = .27, Figure S2; risk ratio (95% confidence interval) 1.06 (0.93, 1.22)).

FIGURE 2.

Kaplan‐Meier survival curve of 30‐day mortality for patients aged ≥ 50 years with AF and COVID‐19 and historical controls with AF without COVID‐19 after propensity score matching. AF: Atrial fibrillation. Propensity score matched for age, gender, race, and history of hypertensive diseases, ischemic heart diseases, heart failure, cerebrovascular diseases, diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, diseases of the respiratory system, diseases of the digestive system, diseases of the nervous system, and neoplasms. Log‐Rank test: P < .0001

4. DISCUSSION

In this study of over 13 000 patients aged ≥50 years with COVID‐19, patients with AF had significantly higher 30‐day risk of thromboembolic events and all‐cause mortality, when compared to patients with no history of AF, propensity score matched for age, gender, race, and history of comorbid conditions. Furthermore, in almost 5000 patients with AF that COVID‐19 was associated with higher risk of mortality compared to propensity score matched historical controls with AF without COVID‐19. However, there was no evidence that the risk of incident 30‐day thromboembolic events was higher for patients with AF and COVID‐19 compared to historical controls with AF without COVID‐19.

In a meta‐analysis of eight studies, cerebrovascular disease was identified to be significantly associated with higher mortality in participants with COVID‐19. 10 The present analyses suggest that history of AF is a risk factor for 30‐day mortality among adults with COVID‐19 independent of history of cerebrovascular disease and cardiovascular and noncardiovascular conditions. A study using nationwide Danish registries showed a 47% decline in registered new‐onset AF in the first three weeks of a nationwide lockdown in Denmark. 11

Diagnosis of AF is critical to ensure appropriate treatment strategies are implemented including stroke risk reduction with anticoagulants, heart rate and rhythm‐control, and management of comorbidities and lifestyle factors. 12 Guidance for the short‐term management of AF for patients with COVID‐19 has been published which includes considerations of important potential drug‐drug interactions of anticoagulants and antiarrhythmic drugs with emerging COVID‐19 treatments. 13

This study has limitations. The main limitation is that the data were collected from the healthcare organisation electronic medical records and some health conditions may be underreported. Previous studies have shown that recording of ICD codes in electronic medical records may vary by factors including age, comorbidities, severity of illness, length of stay in hospital, and in‐hospital mortality. 14 Race was based on limited prespecified race categories within TriNetX and was unknown for up to 18% of the cohorts investigated. Further residual confounding may include lifestyle factors such as alcohol consumption and physical activity which were not available. Furthermore, propensity scores are a method used to balance covariates, but in observational studies propensity scores are estimated and therefore there is no certainty that the propensity scores are 100% accurate. 15 We also could not determine if there was any impact of attending different healthcare organizations because of data privacy restrictions. We examined all deaths of the included patients captured within the TriNetX network; however, deaths outside of the participating healthcare organizations are not well captured. This study did not find an association between COVID‐19 and higher risk of thromboembolic events, but causes of death could not be ascertained within the TriNetX network which may impact the validity of this finding. Further research is needed to confirm the finding that COVID‐19 is not associated with higher risk of thromboembolic events among AF patients and to decipher the underlying causes of higher risk of mortality with AF and COVID‐19.

5. CONCLUSIONS

This study utilised a global research network and propensity score matched over 13 000 older adults with COVID‐19. The results suggest that AF is a risk factor for thromboembolic events and mortality 30‐days following COVID‐19 after taking into account important demographic factors and comorbidities. COVID‐19 was also associated with higher risk of 30‐day mortality compared to historical controls with AF without COVID‐19 among nearly 5000 older adults with AF. However, there was no difference in risk of thromboembolic events for people with AF and COVID‐19 compared to historical controls. AF could be an important risk factor to consider for inclusion in risk modeling and subsequent stratification of adults with COVID‐19 and targeting of intervention strategies.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Stephanie L Harrison: None declared. Elnara Fazio‐Eynullayeva and Paula Underhill are employees of TriNetX Inc Deirdre A Lane has received investigator‐initiated educational grants from Bristol‐Myers Squibb (BMS), has been a speaker for Boehringer Ingeheim and BMS/Pfizer, and has consulted for BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Daiichi‐Sankyo. Gregory Lip: consultant for Bayer/Janssen, BMS/Pfizer, Medtronic, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, Verseon, and Daiichi‐Sankyo and speaker for Bayer, BMS/Pfizer, Medtronic, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Daiichi‐Sankyo. No fees are directly received to Gregory Lip personally.

Supporting information

Figure S1

Figure S2

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

There was no specific funding received for this study. TriNetX Inc funded the acquisition of the data used.

Harrison SL, Fazio‐Eynullayeva E, Lane DA, Underhill P, Lip GYH. Atrial fibrillation and the risk of 30‐day incident thromboembolic events and mortality in adults ≥ 50 years with COVID‐19. J Arrhythmia.2021;37:231–237. 10.1002/joa3.12458

REFERENCES

- 1. World Health Organization . Novel Coronavirus (2019‐nCoV) Situation Report ‐ 11. 2020. [cited 07/07/2020]. Available from https://www.who.int/docs/default‐source/coronaviruse/situation‐reports/20200131‐sitrep‐11‐ncov.pdf?sfvrsn=de7c0f7_4

- 2. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control . Situation update worldwide, as of 5 August 2020. [cited 04/05/2020]. Available from https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/geographical‐distribution‐2019‐ncov‐cases

- 3. Driggin E, Madhavan MV, Bikdeli B, Chuich T, Laracy J, Biondi‐Zoccai G, et al. Cardiovascular considerations for patients, health care workers, and health systems during the COVID‐19 pandemic. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75(18):2352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, Zhu F, Liu X, Zhang J, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323(11):1061–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Inciardi RM, Adamo M, Lupi L, Cani DS, Di Pasquale M, Tomasoni D, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of patients hospitalized for COVID‐19 and cardiac disease in Northern Italy. Eur Heart J. 2020;41(19):1821–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kirchhof P, Benussi S, Kotecha D, Ahlsson A, Atar D, Casadei B, et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with EACTS. Eur Heart J. 2016;37(38):2893–962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bikdeli B, Madhavan MV, Jimenez D, Chuich T, Dreyfus I, Driggin E, et al. COVID‐19 and thrombotic or thromboembolic disease: implications for prevention, antithrombotic therapy, and follow‐up. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020. 75(23):2950–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Holshue ML, DeBolt C, Lindquist S, Lofy KH, Wiesman J, Bruce H, et al. First case of 2019 novel coronavirus in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(10):929–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . ICD‐10‐CM official coding guidelines ‐ supplement coding encounters related to COVID‐19 coronavirus outbreak. 2020. [cited 8 June 2020]. Available from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/icd/ICD‐10‐CM‐Official‐Coding‐Gudance‐Interim‐Advice‐coronavirus‐feb‐20‐2020.pdf

- 10. Wang Y, Shi L, Wang Y, Duan G, Yang H. Cerebrovascular disease is associated with the risk of mortality in coronavirus disease. Neurol Sci. 2019;2020:1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Holt A, Gislason GH, Schou M, Zareini B, Biering‐Sørensen T, Phelps M, et al. New‐onset atrial fibrillation: incidence, characteristics, and related events following a national COVID‐19 lockdown of 5.6 million people. Eur Heart J. 2020;41(32):3072–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lip GYH. The ABC pathway: an integrated approach to improve AF management. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2017;14(11):627–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rattanawong P, Shen W, El Masry H, Sorajja D, Srivathsan K, Valverde A, et al. Guidance on short‐term management of atrial fibrillation in coronavirus disease 2019. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9(14):e017529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chong WF, Ding YY, Heng BH. A comparison of comorbidities obtained from hospital administrative data and medical charts in older patients with pneumonia. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Austin PC. An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies. Multivariate Behav Res. 2011;46(3):399–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1

Figure S2