Abstract

A 32-year-old female patient presented with severe facial pain, right eye proptosis and diplopia. Endoscopy revealed ipsilateral crusting, purulent discharge and bilateral nasal polyps. Imaging demonstrated a subperiosteal abscess on the roof of the right orbit. Due to patient’s significant ocular manifestations, surgical management was decided. The abscess was drained using combined endoscopic and external approach, via a Lynch-Howarth incision. Following rapid postoperative improvement, patient’s regular follow-up remains uneventful. A subperiosteal orbital abscess is a severe complication of rhinosinusitis that can ultimately endanger a patient’s vision. It is most commonly located on the medial orbital wall, resulting from direct spread of infection from the ethmoid cells. The rather uncommon superiorly based subperiosteal abscess occurs superiorly to the frontoethmoidal suture line, with frontal sinusitis being its main cause. Treating it solely endoscopically is more challenging than in medial wall abscesses, and a combined approach is often necessary.

Keywords: ear, nose and throat, infections, nose and throat/otolaryngology, otolaryngology / ENT

Background

Orbital complications of rhinosinusitis are progressive infections that can ultimately endanger a patient’s vision and can occur at any age but are most common in children.1 The classifications by Chandler et al2 and Moloney et al3 are most commonly used, when staging these complications. A subperiosteal orbital abscess (SOA) consists of a purulent collection, developed under the periosteum, between the periorbita and the bony wall of the orbit.4 It can cause deviation of the globe, leading to proptosis, and restriction of extraocular muscles, thus impairing ocular mobility. Imaging is crucial for diagnosis and preoperative planning. SOA is most commonly located on the medial orbital wall, usually resulting from direct spread of infection from the ethmoid cells. The superiorly based subperiosteal orbital abscess (SSOA) refers to a relatively rare site of subperiosteal purulent collection, superiorly to the frontoethmoidal suture line. Frontal sinusitis appears to be its cause in the majority of cases.5 This location is harder to access endoscopically, and either an external or a combined approach is, most often, used for treatment.

Case presentation

A 32-year-old female patient presented with severe facial pain, mostly on the right half of her face, and frontal headache, without fever. The symptoms were reported deteriorating over the last 6 days. During the past 24 hours, she had also developed ipsilateral periorbital oedema and proptosis. The patient was a non-smoker, with a history of chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps (CRSwNP). She had undergone endoscopic sinus surgery 4 years ago; however, no information was provided regarding the findings or the extent of the surgery. At present, the patient was under rupatadine (10 mg orally per day) and intranasal fluticasone (50 µg two times per day). Nasal endoscopy revealed bilateral polyps. Examination of the left nasal cavity showed no postoperative lesions or discharge, and the polyps were confined in the middle meatus. Conversely, purulent discharge and crusting were found in the right nasal cavity, along with extensive oedema. Findings of a previous maxillary antrostomy were noted as were polyps, extending beyond the middle meatus.

Investigations

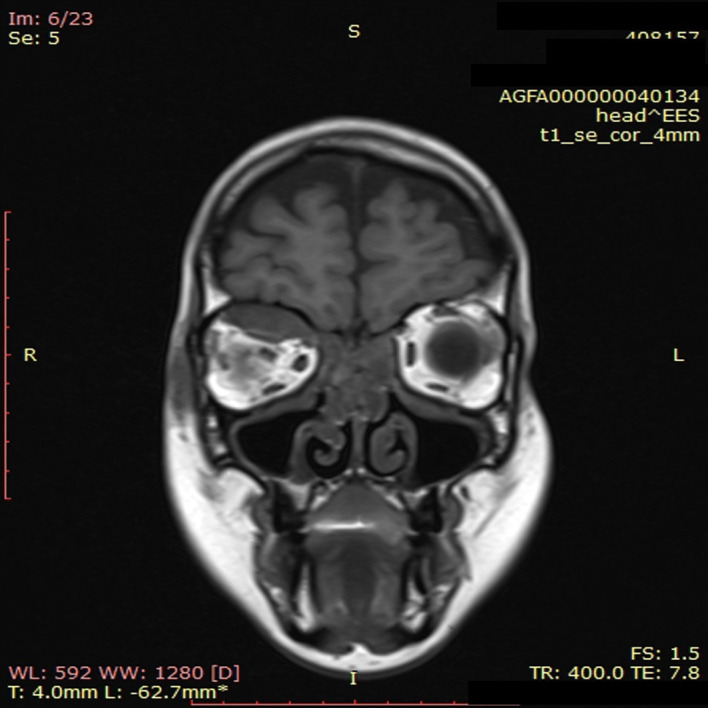

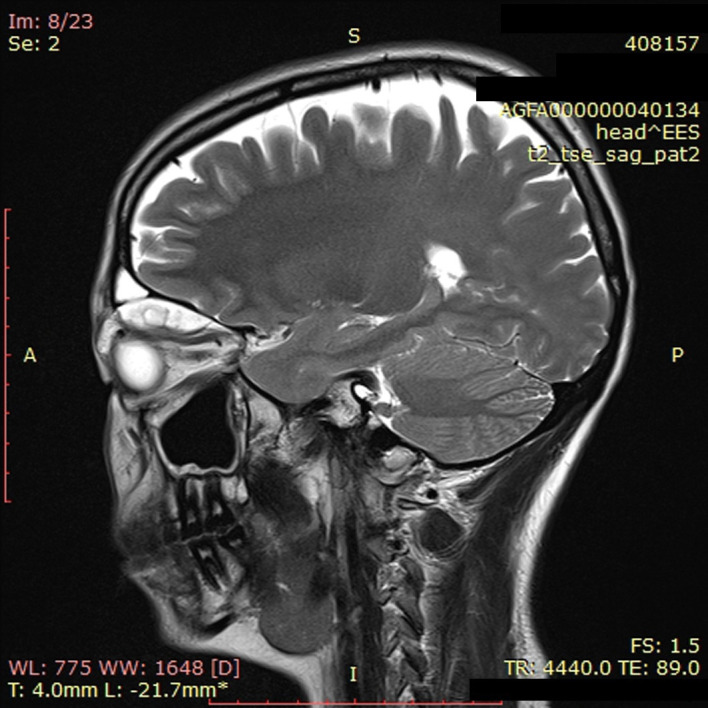

A complete blood count showed no elevation of white blood cells (9220×109/L), and the C-Reactive Protein (CRP) levels were normal (2.5 mg/L). Ophthalmology consultation was provided, which demonstrated binocular diplopia and limited right ocular mobility, especially in upward position. The patient underwent a CT scan that showed soft-tissue density lesions in the right frontal sinus, the ethmoid cells and the right orbit (figures 1 and 2). Right ocular proptosis is also apparent. A subsequent MRI clearly demonstrated a 3 cm subperiosteal abscess, at the anteromedial part of the right orbital roof, pressing the extraocular muscles (figures 3 and 4). No intracranial extension was noted. However, an erosion of the superior part of the right lamina papyracea was deemed probable.

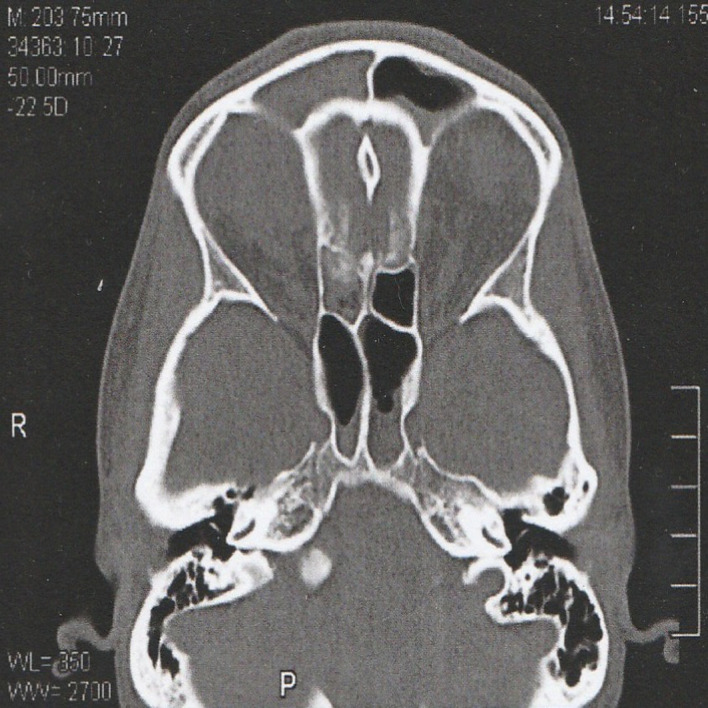

Figure 1.

Axial CT showing the affected right frontal sinus and ethmoid cells.

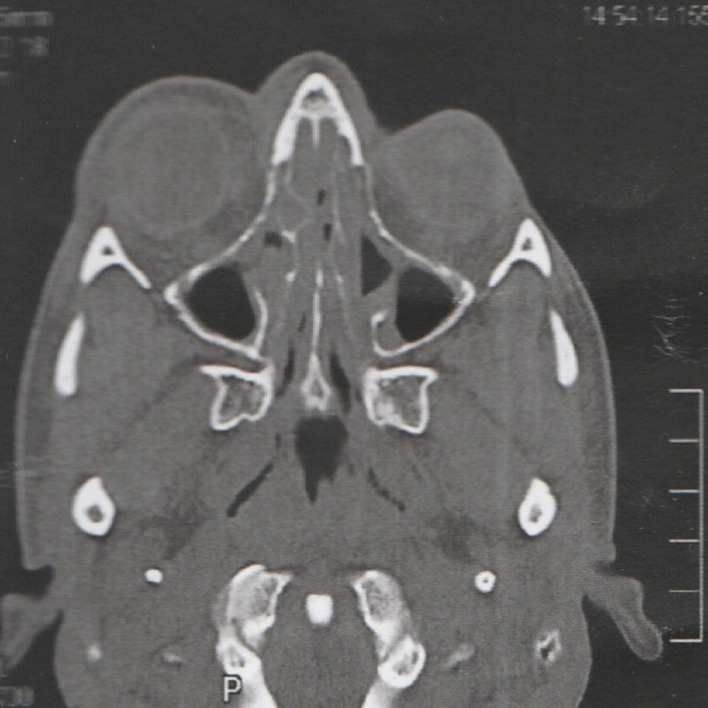

Figure 2.

Axial CT showing the affected right orbit. Right ocular proptosis is apparent.

Figure 3.

Coronal MRI demonstrating the superiorly based subperiosteal orbital abscess.

Figure 4.

Sagittal MRI showing the abscess at the anteromedial part of the right orbital roof and its extent posteriorly.

Treatment

The patient was admitted in our department, and intravenous medication was administered that consisted of ceftriaxone (1 g three times a day), metronidazole (500 mg three times a day) and analgesics. Given the patient’s proptosis and impaired ocular mobility, it was decided to proceed with surgery rather than wait for response to medical treatment. The patient was thoroughly informed, and consent was obtained. The patient underwent endoscopic surgery in order to address the abscess. The nasal polyps located in the right middle meatus and on the medial surface of the middle turbinate were excised. The previous maxillary antrostomy was revised, and the right maxillary sinus was found normal, except for some mild mucosal oedema. Subsequently, complete ethmoidectomy and right frontal sinusotomy (Draf IIa) were performed. Samples of the purulent discharge from the nasal cavity and frontal sinuses, following sinusotomy, were taken separately and sent for microbiological examination and culture. The right anterior ethmoid artery was recognised, and the lamina papyracea was gently removed superiorly and towards the sphenoid, given the fact that the abscess extended posteriorly. The orbital periosteum was manipulated, and the abscess was reached, with subsequent purulent discharge. However, the amount of discharge was troubling, as it was significantly less than expected (approximately <0.5 cc), given the size of the abscess. Further manipulation did not result in any additional purulent discharge, making obvious that complete endoscopic drainage of the abscess was not accomplished, probably because of the location of the abscess in combination with the extensive inflammation that rendered manipulation unsuccessful. Therefore, it was decided to proceed with external completion of the cavity drainage, through a Lynch-Howarth incision. Subperiosteal access was obtained, fibrous adhesions within the cavity were broken down and the abscess was completely drained. Two short Penrose drain tubes were placed.

Outcome and follow-up

Postoperative course was uneventful. The patient showed immediate postoperative decrease of proptosis along with significant improvement of the facial pain. Diplopia was completely resolved on the first postoperative day. The patient regained full ocular mobility on the second postoperative day. The Penrose drain tubes were removed on the third postoperative day. She was discharged, following a total of 6 days of hospitalisation, with instructions about subsequent oral and intranasal medication. She was examined 2 weeks later; healing process was normal, and she was asymptomatic. She was regularly followed-up for 2 years since surgery, with the main focus being her CRSwNP. During the follow-up period, she experienced no exacerbations of chronic rhinosinusitis nor had she developed any new orbital complications.

Discussion

SOAs present with a varying prevalence among different studies, comprising approximately 12%–20% of orbital complications of rhinosinusitis.6–8 They are usually located medially, developing under the periosteum of the bony orbital wall. However, approximately 15%–40% of SOAs can be found in a superior or superolateral position.9–12 Infection of ethmoid cells, during rhinosinusitis, is generally considered responsible for dissemination to the orbital wall, through the thin lamina papyracea. Interestingly, in superior or inferior SOAs, unilateral paranasal sinus involvement has been noted, as demonstrated also in our case.10 There seems to be a shift in the literature towards frontal sinusitis as the main causative factor of an SSOA. Dissemination to the orbital wall appears to happen through existing bony foramina or dehiscences, through valveless vein connections in the frontal sinus floor or due to direct extension.11 Furthermore, patients with frontal sinus involvement tend to have more serious disease and larger abscesses.12 There is no consensus among authors regarding initial treatment of an SOA, and several studies have been published, comparing medically and surgically treated patients. In most of them, paediatric patients are studied, and risk factors for prompt surgical intervention are identified. The criteria set by Garcia and Harris13 appear to be the base contemplated in most studies. Data appear to accumulate regarding the use of age, with a cut-off point at 9 years, and the size of the abscess as risk factors for surgical treatment.14 15 Ryan et al define ‘large abscess’ as any abscess larger than 10 mm and found that it was more likely to necessitate surgery (92% vs 19%, respectively, p<0.001). Todman et al found that abscess volume <1250 mm3 was a statistically significant parameter, in patients that did not need surgery (p<0.001). Further evidence is necessary for establishing these risk factors as standard of care. However, most authors conclude that ocular symptoms, such as proptosis, diplopia, impaired visual acuity and ophthalmoplegia, should prompt surgical treatment.16 Rahbar et al found proptosis to be the only significant multivariate predictor of surgical intervention.17 A suggestion is made by Quintanilla-Dieck et al that SSOAs are more likely to need initial surgical intervention, compared with medial SOAs, given that they present more often with clinical manifestations, such as proptosis.18 Our patient had a sizeable SSOA and demonstrated significant ocular symptoms, leading to prompt surgical management, in accordance with the available evidence. Surgical treatment must address sinus disease and achieve complete abscess drainage. Traditionally, either external or combined external and endoscopic approaches have been used for the treatment of SOAs. External ethmoidectomy via a Lynch-Howarth incision is the classic external approach, and transcaruncular approach combined with endoscopic technique has also been presented.9 As endoscopic techniques evolve, they have become the most common approach, treating both sinus disease and the SOA. Froehlich et al have described a minimal endoscopic approach limited to the opening of the bulla ethmoidalis and abscess cavity.4 However, only two cases of a SSOA, treated exclusively via endoscopic approach, are reported in the literature.19 20 A SSOA, therefore, located at a site more challenging to be approached via endoscopic techniques generally requires either external or a combined approach.

Learning points.

Subperiosteal orbital abscesses can ultimately endanger a patient’s vision.

Superiorly based subperiosteal orbital abscesses (SSOAs) are usually associated with unilateral sinus involvement.

SSOAs are most often caused by frontal sinusitis and demonstrate more severe clinical manifestations.

Patients with ocular symptoms and sizeable abscesses will most probably require surgical management.

The surgeon should be prepared to combine external and endoscopic approach to achieve complete drainage.

Footnotes

Contributors: GC reviewed the case and the literature and wrote the first draft. PK reviewed and edited the draft and figures. EK reviewed the manuscript and provided supervision. AC was the attending surgeon and reviewed and edited the final manuscript. The final manuscript was approved by all authors.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Segal N, Nissani R, Kordeluk S, et al. Orbital complications associated with paranasal sinus infections – a 10-year experience in Israel. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2016;86:60–2. 10.1016/j.ijporl.2016.04.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chandler JR, Langenbrunner DJ, Stevens ER. The pathogenesis of orbital complications in acute sinusitis. Laryngoscope 1970;80:1414–28. 10.1288/00005537-197009000-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moloney JR, Badham NJ, McRae A. The acute orbit. Preseptal (periorbital) cellulitis, subperiosteal abscess and orbital cellulitis due to sinusitis. J LaryngolOtol Suppl 1987;12:1–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Froehlich P, Pransky SM, Fontaine P, et al. Minimal endoscopic approach to subperiosteal orbital abscess. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1997;123:280–2. 10.1001/archotol.1997.01900030054006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sciarretta V, Demattè M, Farneti P, et al. Management of orbital cellulitis and subperiosteal orbital abscess in pediatric patients: a ten-year review. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2017;96:72–6. 10.1016/j.ijporl.2017.02.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Emmett Hurley P, Harris GJ. Subperiosteal abscess of the orbit: duration of intravenous antibiotic therapy in nonsurgical cases. Ophthalmic PlastReconstr Surg 2012;28:22–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williams BJ, Harrison HC. Subperiosteal abscesses of the orbit due to sinusitis in childhood. Aust N Z J Ophthalmol 1991;19:29–36. 10.1111/j.1442-9071.1991.tb01796.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pond F, Berkowitz RG. Superolateral subperiosteal orbital abscess complicating sinusitis in a child. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 1999;48:255–8. 10.1016/S0165-5876(99)00019-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kayhan FT, Sayn İbrahim, Yazc ZM, et al. Management of orbital subperiosteal abscess. J Craniofac Surg 2010;21:1114–7. 10.1097/SCS.0b013e3181e1b50d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ketenci İbrahim, Ünlü Y, Vural A, et al. Approaches to subperiosteal orbital abscesses. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2013;270:1317–27. 10.1007/s00405-012-2198-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gavriel H, Jabrin B, Eviatar E. Management of superior subperiosteal orbital abscess. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2016;273:145–50. 10.1007/s00405-015-3557-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dewan MA, Meyer DR, Wladis EJ. Orbital cellulitis with subperiosteal abscess: demographics and management outcomes. Ophthalmic PlastReconstr Surg 2011;27:330–2. 10.1097/IOP.0b013e31821b6d79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garcia G, Harris GJ. Criteria for nonsurgical management of subperiosteal abscess of the orbit analysis of outcomes 1988–1998. Ophthalmology 2000;107:1454–6. 10.1016/S0161-6420(00)00242-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ryan JT, Preciado DA, Bauman N, et al. Management of pediatric orbital cellulitis in patients with radiographic findings of subperiosteal abscess. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2009;140:907–11. 10.1016/j.otohns.2009.02.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Todman MS, Enzer YR. Medical management versus surgical intervention of pediatric orbital cellulitis: the importance of subperiosteal abscess volume as a new criterion. Ophthalmic PlastReconstr Surg 2011;27:255–9. 10.1097/IOP.0b013e3182082b17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bedwell JR, Choi SS. Medical versus surgical management of pediatric orbital subperiosteal abscesses. Laryngoscope 2013;19:2337–8. 10.1002/lary.24014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rahbar R, Robson CD, Petersen RA, et al. Management of orbital subperiosteal abscess in children. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2001;127:281–6. 10.1001/archotol.127.3.281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Quintanilla-Dieck L, Chinnadurai S, Goudy SL, et al. Characteristics of superior orbital subperiosteal abscesses in children. Laryngoscope 2017;127:735–40. 10.1002/lary.26082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roithmann R, Uren B, Pater J, et al. Endoscopic drainage of a superiorly based subperiosteal orbital abscess. Laryngoscope 2008;118:162–4. 10.1097/MLG.0b013e31814cf39d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim JH, Kim S-H, Song CI, et al. Image-Guided nasal endoscopic drainage of an orbital superior subperiosteal abscess. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2016;54:e26–8. 10.1016/j.bjoms.2015.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]