Abstract

Purpose

By directly engaging with women diagnosed with ovarian cancer, this study aimed to explore and identify their view of the health symptoms and outcomes that matter most to them as they traverse their disease pathway.

Background

Patient-reported outcome measures in ovarian cancer have tended to focus on physical symptoms rather than the more complex psychosocial aspects of living with the disease. Using a “ground-up approach”, this study sought to comprehensively understand the health concerns that matter most to women with ovarian cancer as a first step in generating items for development into an ovarian cancer–specific patient-reported outcome measure.

Patients and Methods

Following an extensive literature review, we sought to capture the “patient voice” through a qualitative descriptive approach including a community conversation with ovarian cancer patients, their carers and clinicians, and interviews and focus groups with women with ovarian cancer. Thirteen women were interviewed individually, and two focus groups were conducted. A template thematic analysis was used to analyze the data.

Results

Key themes included challenges related to clinical diagnosis, treatment phase, altered relationships with family/friends, financial issues, relationships with health professionals and coping strategies. Within each key theme, several sub-themes emerged that were identified as various challenges experienced by participants. Diagnostic delay, chemotherapy and surgery-related challenges, negative impact of sexual well-being on partner relationship, communicational challenges with health professionals were among the few issues identified. In addition, self-empowerment was identified as a coping mechanism among participants.

Conclusion

By identifying priorities for women diagnosed with ovarian cancer we have highlighted the need for strategies to reduce diagnostic delays and improve quality of life for these women. Data will inform the development of an ovarian cancer–specific patient-reported outcome measure.

Keywords: focus groups, health-related quality of life, qualitative descriptive, patient-reported outcome measures, semi-structured interviews

Introduction

Ovarian cancer (OC) affects women of all ages but is most commonly diagnosed after menopause. More than 75% of affected women are diagnosed at an advanced stage because early-stage disease is usually asymptomatic, and symptoms of late-stage disease are nonspecific. The strongest risk factors are advancing age and family history of ovarian and breast cancer.1 Currently there is no effective population-level screening test for OC.2,3 Treatment usually involves radical surgery and chemotherapy with subsequent lines of chemotherapy for disease recurrence.4 Treatments can impair health-related quality of life (HRQOL), a concept that pertains to general well-being or outcomes surrounding a specific disease.5,6

Over the previous two decades, patients have had increasing roles in providing information and participating in clinical decisions for managing their cancer. Structured patient provided information without clinician modification and/or interpretation is termed a patient-reported outcome measure (PROM).7 PROMs can be either generic tools such as the hospital anxiety and depression scale or disease-specific tools designed for specific groups of patients such as those with gynecologic cancers.8 Patient involvement has a profound impact on PROM development as it is only the patients who can determine item relevance and comprehensibility of the tool.9,10

Currently, four validated OC specific PROMs have been developed to measure HRQOL of the patients: The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire of Cancer Patients – Ovarian Cancer module (EORTC QLQ-OV28), Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy Ovarian Cancer (FACT-O), FACT Ovarian Symptom Index (FOSI) and Measure of Ovarian Symptoms and Treatment Concerns (MOST).11–13 However, these tools do not identify all aspects of HRQOL and differences exist in the level of patient involvement in the development of these PROMs, which is vital for PROM development.14

This study is affiliated with an overarching project, Patients First: Continuous Improvement in Care-Cancer (“CIC” Cancer), that aims to develop an OC PROM to measure HRQOL, through a “ground-up approach” that includes meaningful patient involvement. As an initial step, this phase of the study involved the collection and analysis of qualitative data to inform the subsequent generation of items necessary for the development of an ovarian cancer–specific HRQOL tool.

Patients and Methods

Study Design

Based on an extensive literature review and assessment of the content of existing cancer PROMs, this study utilized a qualitative descriptive approach. A qualitative descriptive approach enables the researcher to obtain comprehensive details of personal events as experienced by individuals and is appropriate for health science researchers as it provides rich and descriptive information from the participant’s perspective.15 This study employed a community conversation for women with OC, their carers and a clinician (PAC) to shape the subsequent semi-structured interviews and focus groups.

Participants

Purposive sampling (non-probability) using a maximum variation sampling strategy was used to identify participants. Purposive sampling enables the researcher to intentionally select participants who have in-depth personal knowledge of the topic which will contribute to the study in alignment with the research aims.16 The participant inclusion criteria were women diagnosed with OC aged above 18 years, who were living in Western Australia and fluent in English. Carers of participants were also invited to participate in the study. Participants were recruited at various time-points from their diagnosis.17

Recruitment Procedure

Community conversation, interview and focus group participants were recruited through an advertisement distributed through the media and relevant agencies including Cancer Council Western Australia (CCWA) and Ovarian Cancer Australia (OCA). Interested participants were asked to contact the researcher(s) and/or CCWA & OCA directly. Thereafter, the participants were contacted by the researchers (CB, SB) who provided them with the choice to participate in either interviews or focus groups. Details of date and time along with venue for the community conversations, interviews and focus groups were sent out by e-mails to participants through both the CCWA member database and the OCA networks along with the CCWA regional support coordinator. The initial “community conversation” facilitated by a qualitative research expert (CB) was held with 15 women with OC (different to those who participated in the interview and focus groups), two consumer advocates, and a gynecologist with experience in gynecological oncology (PAC) to explore some of the key issues of personal importance to key stakeholder groups.

Data Collection

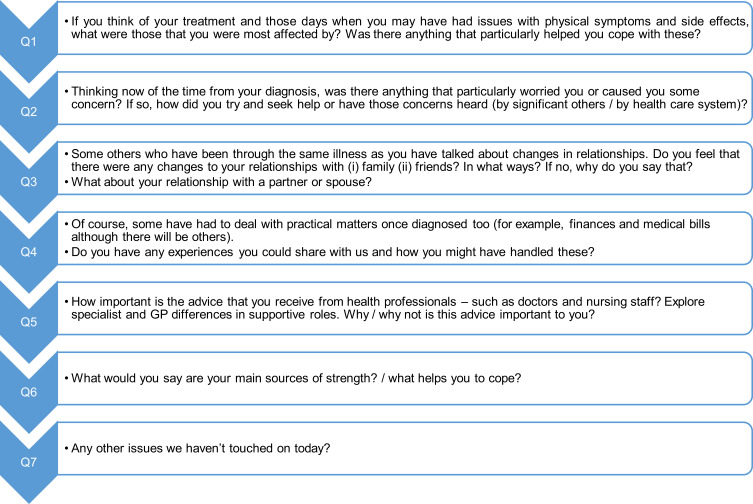

Ethics approval for this study was granted by the Human Research Ethics Committee at University of Notre Dame Australia (018158F) and conforms to Australian “2018 Update of the National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research”. The participant information sheet and consent form were provided to participants and the signed consent form was obtained from the participants prior to data collection. All participants provided consent for their de-identified data to be published. Guided by the literature review and the field notes during community conversation, similar question formats were formulated for both interviews and focus groups, Figure 1. In addition, our study processes complied with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Figure 1.

Question format used during semi-structured telephone interviews and focus groups.

Along with the qualitative research expert, the student researcher (SB) independently conducted individual telephone interviews of approximately 30 minutes duration with 13 OC patients at their place of convenience. The research team (CB, SB) then conducted two focus groups in metropolitan Perth, Western Australia. A total of 13 participants attended one of the two focus groups, each lasting approximately 90 minutes, with participation of three carers in the second focus group. Participants varied in their age. Most participants were employed and were married/defacto. Four participants were over 5 years since diagnosis, but one participant had received a diagnosis less than 6 months at the time of the interview. Disease status of the participants at the time of the interview was obtained. Six participants were undergoing active treatment, with a completion of at least two full cycles of chemotherapy. The remaining participants confirmed that they were in remission or awaiting treatment. The number of cases of OC in Western Australia is small compared to some other cancers (eg breast, prostate) and it was important to recruit as many women with OC across the disease trajectory as possible. Thus, the focus of this study was the importance of the different experiences of the participants.

Analysis

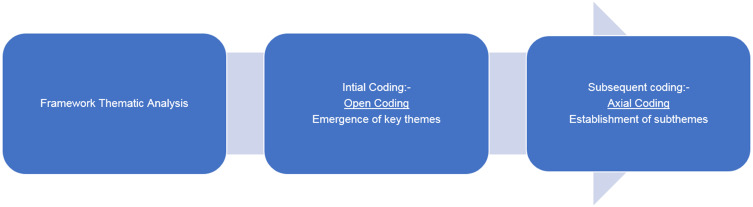

Data saturation was achieved, and collected data were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim by the student researcher (SB). Template thematic analysis was performed which included open and axial coding using the qualitative data management program, QSR NVivo (version 12), Figure 2.18 Template analysis is defined as a method for identifying, analysing19 and reporting themes in the data based on the task question format. It enables the researcher to identify emerging themes in understanding a phenomenon or event.20,21 Key themes identified were categorized as core themes and further emerging themes then became the categorical sub-themes for analysis.

Figure 2.

Stages of qualitative analysis process: an illustration.

Member checking also included sending the summary of coding and themes back to four participants who had indicated that they were willing to receive this summary via the CCWA and OCA support group coordinators.

Results

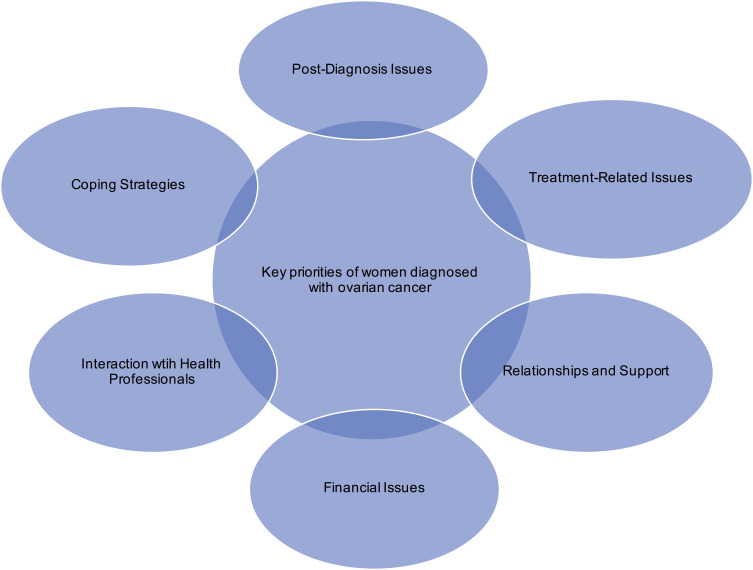

Six key themes emerged regarding various aspects of illness and treatment experiences described by the women and their carers (Figure 3). Within each key theme, several sub-themes and relative sub-themes emerged that were identified as various challenges experienced by participants as detailed below.

Figure 3.

Representation of key themes emerged from interviews and focus groups.

Diagnosis, Treatment and Related Issues

Four factors were identified in relation to the symptomatic presentation pertaining to the disease and are shown in Table 1. Participants experienced pre-diagnostic symptoms including abdominal/bowel discomfort and pain, urinary urgency, fatigue, weight gain, abnormal menstrual bleeding and/or menopausal symptoms. Lack of awareness of disease symptoms by both patients and health professionals (HPs) was a related issue. Due to work and family commitments, several participants intentionally ignored their symptoms. In further, majority of the participants expressed diagnostic delay as another challenge faced during their clinical diagnosis phase.

Table 1.

Percentage of Participants with Symptoms and Presentation

| Symptoms | Percentage of Participants |

|---|---|

| Abdominal discomfort | 19.2 |

| Bloating | 11.5 |

| Bowel movement pain | 7.7 |

| Constipation | 3.8 |

| Eye issues | 3.8 |

| Fatigue | 7.7 |

| Joint pain | 3.8 |

| Menopause symptoms | 11.5 |

| Perineal pain | 3.8 |

| Urinary urgency | 19.2 |

| Weight gain | 7.7 |

| Symptom presentation | |

| Lack of disease symptoms awareness | 42.3 |

| Asymptomatic presentation | 19.2 |

| Self-monitoring of symptoms | 7.7 |

Notes: The percentage for each symptom/symptom presentation is calculated as per the number of interview/focus groups participants reporting it. Thus, for total number of participants (n=26), the total percentage of symptoms/symptom presentation does not equate to 100 percentage.

Challenges related to receiving treatments were highlighted with at least half of the participants feeling vulnerable at times since receiving their diagnosis. Most of the participants were challenged by side-effects. Fatigue, nausea, neuropathy, memory loss and loss of appetite were the most common side-effects identified, with less common side-effects such as mucositis and organ failure also described. Support of family and friends provided strength for the majority of the participants. Some women indicated having to modify their usual diet, lifestyle and physical activity during treatment. Activities such as meditation, cycling, gardening and yoga helped them cope during and after treatment. However, some participants also mentioned how empowering themselves during treatment was vital. Maintaining and having a relaxed mind, a positive attitude and a sense of humor were practiced by a few, despite the situations they were facing at that time.

Another participant spoke of how she had lost the chance of experiencing motherhood. Rurally located participants faced further travel challenges of time and distance. And furthermore, two participants highlighted the issues around having lack of treatment options while travelling, either it be a rural destination or an interstate travel.

Living with the OC Trajectory

Other key themes related to living with a diagnosis of OC across the disease trajectory.

Relationships and Support

All participants agreed that relationships with their family and friends influenced their lives. Some participants spoke of experiencing lack of support with unpredictable reactions and withdrawal of family and/or friends. Other participants spoke of being avoided and noticed that people around them “react differently” which then created emotional reactions such as upset and insecurity. Furthermore, sexual relations and a changed level of intimacy with a partner/spouse were identified as an important subtheme in their lives. Many participants described how a lack of intimacy had put pressure on their partner/spouse relationship and affected their emotional well-being. A few participants described their sexual relationship as “non-existent” and that a counsellor had been consulted.

Most of the participants agreed and acknowledged having support from family and/or friends had a profound impact on their lives. A positive relationship with close family boosted their journey particularly following the diagnosis and during treatment. Participants described drawing strength and emotional support, and an increased interpersonal relationship bond with family and friends.

Financial Issues

Almost all participants reported having financial issues such as out-of-pocket expenses for scans, surgery and other practical issues including hospital parking and medication costs. Several participants reported lack of information about accessing health services. Some mentioned the financial toxicity associated with their illness and that they lacked knowledge of how to access support services such as paying the bills without going into debt and having to access their superannuation funds for urgent and necessary expenses.

“I guess it was not even initially when I wasn’t told about certain things I could access like my super. I had to find out I think two years down the track or something. So it wasn’t, nobody even gave me that sort of information.”

Some participants had to stop work during treatment and others had to reduce their workload to cope with the challenges and issues faced during their clinical journey.

Interaction with Health Professionals

Participants spoke of their relationships and experiences with their respective HPs. In general, most participants acknowledged having a positive relation with HPs including general practitioners (GPs), gynecological oncology and medical oncology providers in terms of the support and medical treatment provided to them. The advice received by the oncology team was described by one participant as “absolutely phenomenal … (they) answered any questions with patience and understanding”.

Meanwhile, some participants spoke of a perceived negative relationship with their HPs. Overall, many participants felt there were communication gaps in the healthcare system, particularly during treatment, and participants experienced various forms of communication challenges either with or between oncologists and GPs and specialist departments.

“Because of my complex medical problem, I’ve been out for a few months affected by surgery and by several treatments. So, I found that (hospital’s) communication between the different departments just wasn’t there.”

Furthermore, issues around clinician lack of empathy and compassion, and providing inconsistent information about prognosis negatively impacted the emotional well-being of many participants. A majority had a less than satisfactory relationship with GPs. Half of the participants described the excessive length of time for their symptoms to be investigated leading to a delay in their diagnosis. Some perceived being ignored or that GPs were “pretty dismissive” about their symptoms thinking they were due to a urinary tract infection or perimenopause and no further action was taken. Furthermore, participants mentioned having difficulties requesting tests such as ultrasound scans and pressed for these.

Insufficient provision of information was one of the key issues in relation to treatment and participants complained that oncologists, did not fully explain the side effects of the prescribed medications. Some participants also reported a lack of involvement in decisions about their treatment and not being provided with treatment options including at disease recurrence.

Coping Strategies

Participants were asked to share their experiences on how they coped with difficult situations through their clinical journey. They described support from family and friends, lifestyle and physical activity assisted them to cope with difficult situations and kept them moving forward. Walking, listening to music, meditation, nutrition and crafts were some examples. Two participants mentioned how making time for themselves was important for both their mind and body. Several participants sought help from support group organisations through which telephone support services, information booklets and complementary services such as yoga were provided.

Self-Empowerment

Some participants emphasized that taking control of their own lives was their one main strength. Identified factors were being able to look forward, having an attitude of not giving up and learning how to “stick up” for oneself. Participants expressed that by being independent and knowing their innermost selves provided them motivation and strength throughout their lives. In addition, providing self-encouragement through positive attitude and feeling gratitude helped them.

“I do need and want to practice gratitude every day. I am grateful for what I’ve got. And I’m much more in tune with the little things in life.”

Further to this, having a strong spiritual belief system helped to calm them and became a source of comfort explicitly during chemotherapy. In addition, having spiritual belief helped not only the participants but also their families to gain strength in order to cope with difficult situations.

Discussion

In this study women with OC were able to express their own voices based on their individual experiences. Therefore, the six themes identified describe both HRQOL and contextual themes. Post diagnosis and treatment-related issues, relationships and supports with family and friends, financial issues, relationships with healthcare providers and self-perceived coping strategies were the key themes identified. Each theme had a number of overlapping sub-themes that were identified as priorities for the women. In particular, challenges related to relationships, financial issues, relationships with health-care providers and coping strategies were experienced during and after diagnosis and treatment.

Diagnostic delay was a key concern and our data suggested that lack of early symptom awareness due to insufficient OC knowledge and symptom recognition by participants and HPs contributed to the delay. This is consistent with studies that have low levels of OC symptom awareness are associated with delayed diagnosis.22–24 While, lack of cancer detection and inexpedient referral patterns influenced incorrect diagnosis by the physicians,25 and greater public education to increase knowledge of disease symptoms could be helpful.26,27

Most participants received a combination of surgery and chemotherapy. Treatments adversely affected physical well-being with prevalent symptoms such as fatigue, nausea and neuropathy. Research is now focusing on symptom management interventions guided by the implementation of PROMs into clinical settings and trials.5,28,29 Several surgery-related outcomes including change in body image, premature and sudden onset of menopause, and loss of reproductive function may affect psychological well-being.30 The possible loss of fertility during treatment with cancer can be more distressing than cancer itself, according to recent reports where efforts to maintain fertility through techniques such as fertility-sparing surgery are essential in younger women diagnosed with gynecological cancers as they could lead to an improvement in quality of life.31 Another recent study indicated high levels of psychological distress when diagnosed women reach childbearing age as menstrual function and fertility were lost. It is therefore important to monitor the progression of cancer but should also provide appropriate fertility preservation counselling. This has potential to alleviate stress, anxiety and depression and a smaller negative effect on the quality of life.32 Consistent with our findings, a past study showed that those who underwent surgery have experienced psychological distress such as lack of self-esteem, self-worth and loss of femininity.33,34

Survivorship is important in cancer care and recent improvements in treatment have resulted in an increased number of survivors.35 However, our findings highlighted the need for patient-centered care. Patient involvement is vital in clinical care, where a recent study pointed to the significance of patient–clinician communication. This communication style provides patients with the platform to raise and discuss issues with clinicians thereby shaping subsequent clinical care processes and outcomes.36

One of the contextual themes of HRQOL identified was perceived lack of provision of adequate information and services. Studies show that educating and communicating patients and their families regarding treatment options and their underlying side-effects will prepare patients to realize the likely outcome of treatment and will assist them in facing upcoming challenges.30,37 Inadequate services such as counselling were identified. Studies show that psychological and other supports are essential in these women’s lives, focusing on psychological well-being as well as counselling related to financial and nutritional needs.30,38

Further, our findings illustrated some communication gaps between the women and their health-care providers. Research shows that engagement of patients with their health-care team strengthens and increases the provision of patient-centered care and thus potentially aids cancer control.39 A 2013 study described that patient–clinician communication may assist adherence and agreement to treatment, where, for example, two-way communication on treatment-based symptoms could aid in symptom management.40 A recent study that focused on the sexual function of women diagnosed with OC reported that not only was there a communication gap between patient and clinicians, the clinicians expected patients to have disease-related sexual problems and waited until patients spoke about their concerns.41 Improving survival, functional recovery and quality of life while minimizing long-term side-effects are key priorities in cancer care.

Social well-being is consistent with the concept of HRQOL. The importance of being supported by family and friends, especially partners/spouses, was a critical factor for well-being. Some participants experienced changes in their relationships. Time spent with family was reduced due to treatment demands and withdrawal of loved ones from them. Previous studies have reported that women have felt displeasure from their friends and were unwilling to discuss about the disease.37

Overall, participants experienced highly compromised HRQOL, around the time of diagnosis and during treatment. There is an urgent need to develop new strategies for early detection and screening,3 as diagnostic delay was associated with psychological distress such as anxiety, fear of death, parental stress and uncertainty in the current study and has also been previously reported.37 Additionally, participants experienced challenge in obtaining appropriate information to access and benefit from the healthcare system post diagnosis. Multiple studies have found that unreliable provision of knowledge and information is a driver of poor medical care in many high-income countries, including Australia.42 Involvement of patients in decision-making and public engagement could improve the evidence-based value of their health care43

Emotional domain is another aspect of HRQOL. Emotional distress was experienced particularly during treatment phase. Fear of recurrence was a source of emotional distress. Previous studies related to gynecological and OC research show that women have fear of disease recurrence during the treatment and post-treatment phases and that these fears are poorly understood.44,45 Frustration was also of concern with almost all women frustrated due to their treatment side-effects and symptoms. A 2020 qualitative study that investigated the life experiences of women diagnosed with OC found similar results on how women fall into frustration following treatment completion.46

Understanding and measuring HRQOL outcomes related to the sexual well-being of women diagnosed with OC is vital. Half of the participants had poorer sexual function impacting their overall health and well-being. Changes to body image, sudden onset of menopause, infertility and lack of intimacy were identified and negatively impact emotional well-being with a sense of losing feminine identity. It has also been found that difficulties with body image and lack of intimacy are associated with impaired quality of life.41

Not only do individuals diagnosed with cancer have detrimental impacts on their sexual functioning, it often influences their partners. Studies suggest that cancer partners may suffer equal or even higher levels of distress relative to their sick spouses. Partners of cancer survivors do not often have the resources to offer sufficient care to their female partners.47 Findings from a 2009 study indicate that the sexual perceptions of the partners were influenced by loss of interest in the individual with cancer and tension and fatigue correlated with care tasks. Carers agreed that reduced happiness with the partnership could be followed by poorer quality of life as well as higher levels of anxiety and depression.48

Financial aspects were described, and this influenced participant wellbeing. Due to the amount of time required to spend in treatments, some participants had lost their income stability either due to change to their employment status or being unable to continue in the workforce, impairing their emotional well-being and overall HRQOL.49 Some issues might appear to be more minor, such as related to the lack of car parking availability at respective clinical settings, but when needed on multiple occasions, this was a more major concern. Studies in women with OC found that disease and treatment-related burdens create several issues including social and financial effects on their lives.38,50

Participants also described current strategies they used in daily life. Participants utilized numerous coping strategies such as modified diet and lifestyle, which could be considered as a contextual factor that could influence HRQOL. Family and friend support was another major help sought by these women, which in turn helped improve and maintain their quality of life.51 Self-empowerment techniques such as ability to look to the future, having positive attitude and sense of humor were a few techniques employed by the participants. Recent studies also show similar coping strategies used by women and how changed views and adding humor to their personal experiences was a means of self-healing.52,53 Overall, the participants were able to maintain their HRQOL and continue a modified normal life with the implementation of various strategies and self-management techniques into their lives.54

Limitations and Strengths of This Study

There are approximately 115 new diagnoses of OC per year in Western Australia,55 potentially compromising data collection using a small sample size. However, maximum variability and data saturation were achieved using small sample size56 and thus should not be considered as a limitation but a strength. While the study sought to explore patient outcomes across the clinical trajectory, participants might not have accurately recalled their perspectives, constituting another limitation.

Moreover, rich and descriptive data were obtained using the qualitative methods,57 where intentionality of the participants and their carers were explored. In addition, utilizing a qualitative approach has enabled a holistic understanding of patients’ and carers’ lived experiences. The “bottom-up” approach of involving patients from commencement and throughout the study will ensure that going forward, priorities are clearly identified by the consumers (women with OC themselves) in consultation with clinicians. We envisage that the proposed OC specific PROM to be developed in a future study would be used in clinical settings to identify and measure specific problems that patients encounter that needed to be discussed.

Conclusion

By identifying key priorities for women with OC using a “ground-up community-based approach”, we have highlighted the need for strategies to reduce diagnostic delays, assist patients in navigating the healthcare system, and improve their HRQOL and potentially develop a OC specific PROM that will enable better identification and earlier treatment of symptoms during the entire course of the disease.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful for the generous involvement of participants, and their carers for sharing their experiences with us.

Funding Statement

This work was carried out with the support of a Grant provided by the Cancer Research Trust and is part of the CIC Cancer Project, a multi-institutional program of research that seeks to bring value-based health care public and private health-care settings in Western Australia.

Abbreviations

CCWA, Cancer Council Western Australia; CIC Cancer Project, Continuous Improvement in Care-Cancer Project; GPs, general practitioners; HPs, health professionals; HRQOL, health-related quality of life; OC, ovarian cancer; OCA, Ovarian Cancer Australia; PROMs, patient-reported outcome measures.

Author Contributions

All authors made significant contributions to the study conception and design, execution, performance of the research, data acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data, took part in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; agreed to submit to the current journal; gave final approval of the version to be published; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

Paul Cohen reports personal fees from Seqirus, outside the submitted work. The authors report no other potential conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Doubeni CA, Doubeni ARB, Myers AE. Diagnosis and management of ovarian cancer. Am Fam Physician. 2016;93(11):937–944. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Natarajan P, Taylor SE, Kirwan JM. Ovarian cancer: current management and future directions. Obstetrics Gynaecology Reproduct Med. 2018;28(6):171–176. doi: 10.1016/j.ogrm.2018.04.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Henderson JT, Webber EM, Sawaya GF. Screening for ovarian cancer updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2018;319(6):595–606. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.21421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Monk BJ, Anastasia PJ. Ovarian cancer: current treatment and patient management. J Adv Pract Oncol. 2016;7(3):271–273. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chase DM, Wenzel L. Health-related quality of life in ovarian cancer patients and its impact on clinical management. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2011;11(4):421–431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Post MWM. Definitions of quality of life: what has happened and how to move on. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. 2014;20(3):167–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meadows KA. Patient-reported outcome measures: an overview. Br J Community Nurs. 2011;16(3):146–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moss HA, Havrilesky LJ. The use of patient-reported outcome tools in Gynecologic Oncology research, clinical practice, and value-based care. Gynecol Oncol. 2018;148(1):12–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trujols J, Portella MJ, Iraurgi I, Campins MJ, Siñol N, Cobos J. Patient-reported outcome measures: are they patient-generated, patient-centred or patient-valued? J Ment Health. 2013;22(6):555–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Staniszewska S, Adebajo A, Barber R, et al. Developing the evidence base of patient and public involvement in health and social care research: the case for measuring impact. Int J Consum Stud. 2011;35(6):628–632. doi: 10.1111/j.1470-6431.2011.01020.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Questionnaires. EORTC Quality of Life; 2019. Available from: https://qol.eortc.org/. Accessed April29, 2020..

- 12.Questionnaires FACIT; 2019. Available from: https://www.facit.org/. 29, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 13.King MT, Stockler MR, O’Connell RL, et al. Measuring what matters MOST: validation of the Measure of Ovarian Symptoms and Treatment, a patient-reported outcome measure of symptom burden and impact of chemotherapy in recurrent ovarian cancer. Qual Life Res. 2018;27(1):59–74. doi: 10.1007/s11136-017-1729-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wiering BM, De Boer D, Delnoij D. Patient involvement in the development of patient-reported outcome measures: the developers’ perspective. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):635. doi: 10.1186/s12913-017-2582-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Colorafi KJ, Evans B. Qualitative Descriptive Methods in Health Science Research. HERD. 2016;9(4):16–25. doi: 10.1177/1937586715614171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Polit DF, Beck CT. Essentials of Nursing Research: Appraising Evidence for Nursing Practice. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Willis GB. Cognitive Interviewing: A Tool for Improving Questionnaire Design. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage Publications; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frey B, Vivo N. The SAGE Encyclopedia of Educational Research, Measurement, and Evaluation. Vols. 1–4 Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications, Inc; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fereday J, Muir-Cochrane E. Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: a hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. Int J Qual Methods. 2006;5(1):80–92. doi: 10.1177/160940690600500107 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liamputtong P, Ezzy D. Qualitative Research Methods: A Health Focus. New York: Oxford University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Freij M, Al Qadire M, Khadra M, et al. Awareness and knowledge of ovarian cancer symptoms and risk factors: a survey of jordanian women. Clin Nurs Res. 2018;27(7):826–840. doi: 10.1177/1054773817704749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brain KE, Smits S, Simon AE, et al. Ovarian cancer symptom awareness and anticipated delayed presentation in a population sample. BMC Cancer. 2014;14(1):171. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Forbes LJL, Simon AE, Warburton F, et al. Differences in cancer awareness and beliefs between Australia, Canada, Denmark, Norway, Sweden and the UK (the International Cancer Benchmarking Partnership): do they contribute to differences in cancer survival? Br J Cancer. 2013;108(2):292–300. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vandborg MP, Edwards K, Kragstrup J, Vedsted P, Hansen DG, Mogensen O. A new method for analyzing diagnostic delay in gynecological cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2012;22(5):712. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0b013e31824c6d0e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Robinson KM, Christensen KB, Ottesen B, Krasnik A. Socio-demographic factors, comorbidity and diagnostic delay among women diagnosed with cervical, endometrial or ovarian cancer. Eur J Cancer Care. 2011;20(5):653–661. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2011.01259.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Puckett MC, Townsend JS, Gelb CA, et al. Ovarian cancer knowledge in women and providers following education with inside knowledge campaign materials. J Cancer Educ. 2018;33(6):1285–1293. doi: 10.1007/s13187-017-1245-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Friedlander ML, King MT. Patient-reported outcomes in ovarian cancer clinical trials. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(uppl_10):x64–x68. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Friedlander ML, Stockler M, O’Connell R, et al. Symptom burden and outcomes of patients with platinum resistant/refractory recurrent ovarian cancer: a reality check: results of stage 1 of the gynecologic cancer intergroup symptom benefit study. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2014;24(5):857–864. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0000000000000147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wenzel L, Vergote I, Cella D. Quality of life in patients receiving treatment for gynecologic malignancies: special considerations for patient care. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2003;83:211–229. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7292(03)90123-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.La Rosa VL, Garzon S, Gullo G, et al. Fertility preservation in women affected by gynaecological cancer: the importance of an integrated gynaecological and psychological approach. Ecancermedicalscience. 2020;14:1035. doi: 10.3332/ecancer.2020.1035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.La Rosa VL, Shah M, Kahramanoglu I, et al. Quality of life and fertility preservation counseling for women with gynecological cancer: an integrated psychological and clinical perspective. J Psychosomatic Obstetrics Gynecol. 2020;41(2):86–92. doi: 10.1080/0167482X.2019.1648424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schulman-Green D, Ercolano E, Dowd M, Schwartz P, McCorkle R. Quality of life among women after surgery for ovarian cancer. Palliat Support Care. 2008;6(3):239–247. doi: 10.1017/S1478951508000497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McCorkle R, Pasacreta J, Tang ST. The silent killer: psychological issues in ovarian cancer. Holist Nurs Pract. 2003;17(6):300–308. doi: 10.1097/00004650-200311000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fitzmaurice C, Allen C, Barber RM, et al. Global, regional, and national cancer incidence, mortality, years of life lost, years lived with disability, and disability-adjusted life-years for 32 cancer groups, 1990 to 2015: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(4):524. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.5688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Greenhalgh J, Gooding K, Gibbons E, et al. How do patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) support clinician-patient communication and patient care? A realist synthesis. J Patient Rep Outcomes. 2018;2(1):1–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Howell D, Fitch MI, Deane KA. Impact of ovarian cancer perceived by women. Cancer Nurs. 2003;26(1):1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grzankowski KS, Carney M. Quality of life in ovarian cancer. Cancer Control. 2011;18(1):52–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lavallee DC, Chenok KE, Love RM, et al. Incorporating patient-reported outcomes into health care to engage patients and enhance care. Health Aff. 2016;35(4):575–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Street RL. How clinician–patient communication contributes to health improvement: modeling pathways from talk to outcome. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;92:286–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fischer OJ, Marguerie M, Brotto LA. Sexual function, quality of life, and experiences of women with ovarian cancer: a mixed-methods study. Sex Med. 2019;7(4):530–539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Saini VD, Garcia-Armesto SMD, Klemperer DMD, et al. Drivers of poor medical care. Lancet. 2017;390(10090):178–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Elshaug AG, Rosenthal MB, Lavis JN, et al. Levers for addressing medical underuse and overuse: achieving high-value health care. Lancet. 2017;390(10090):191–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oza AM, Matulonis UA, Malander S, et al. Quality of life in patients with recurrent ovarian cancer treated with niraparib versus placebo (ENGOT-OV16/NOVA): results from a double-blind, Phase 3, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19(8):1117–1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Holliday CM, Morte M, Byrne JM, Holliday AT. experience and expectations of ovarian cancer patients in australia. J Oncol. 2018;2018:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tsai L-Y, Tsai J-M, Tsay S-L. Life experiences and disease trajectories in women coexisting with ovarian cancer. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;59(1):115–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Iżycki D, Woźniak K, Iżycka N. Consequences of gynecological cancer in patients and their partners from the sexual and psychological perspective. Prz Menopauzalny. 2016;15(2):112–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gilbert E, Ussher JM, Hawkins Y. Accounts of disruptions to sexuality following cancer: the perspective of informal carers who are partners of a person with cancer. Health. 2009;13(5):523–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bhugwandass CS, Pijnenborg JMA, Pijlman B, Ezendam NPM. Effect of chemotherapy on health-related quality of life among early-stage ovarian cancer survivors: a study from the population-based PROFILES registry. Curr Oncol. 2016;23(6):e556–e562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.von Gruenigen VE, Huang HQ, Gil KM, et al. Assessment of factors that contribute to decreased quality of life in Gynecologic Oncology Group ovarian cancer trials. Cancer. 2009;115(20):4857–4864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wen Q, Shao Z, Zhang P, Zhu T, Li D, Wang S. Mental distress, quality of life and social support in recurrent ovarian cancer patients during active chemotherapy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2017;216:85–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rose SL, Spencer RJ, Rausch MM. The use of humor in patients with recurrent ovarian cancer: a phenomenological study. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2013;23(4):775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tsai L-Y, Wang K-L, Liang S-Y, Tsai J-M, Tsay S-L. The lived experience of gynecologic cancer survivors in Taiwan. J Nurs Res. 2017;25(6):447–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schulman‐Green D, Jaser S, Martin F, et al. Processes of self‐management in chronic illness. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2012;44(2):136–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Australia DoHW. Western Australian Cancer Registry Statistics; 2017. Available from: https://ww2.health.wa.gov.au/Articles/U_Z/Western-Australian-Cancer-Registry-Statistics. Accessed September30, 2020.

- 56.Malterud K, Siersma VD, Guassora AD. Sample size in qualitative interview studies: guided by information power. Qual Health Res. 2016;26(13):1753–1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mason M. Sample size and saturation in PhD studies using qualitative interviews. FQS. 2010;11(3):1–19. [Google Scholar]