Abstract

The need for cell and particle sorting in human health care and biotechnology applications is undeniable. Inertial microfluidics has proven to be an effective cell and particle sorting technology in many of these applications. Still, only a limited understanding of the underlying physics of particle migration is currently available due to the complex inertial and impact forces arising from particle–particle and particle–wall interactions. Thus, even though it would likely enable significant advances in the field, very few studies have tried to simulate particle-laden flows in inertial microfluidic devices. To address this, this study proposes new codes (solved in OpenFOAM software) that capture all the salient inertial forces, including the four-way coupling between the conveying fluid and the suspended particles traveling a spiral microchannel. Additionally, these simulations are relatively (computationally) inexpensive since the arbitrary Lagrangian–Eulerian formulation allows the fluid elements to be much larger than the particles. In this study, simulations were conducted for two different spiral microchannel cross sections (e.g., rectangular and trapezoidal) for comparison against previously published experimental results. The results indicate good agreement with experiments in terms of (monodisperse) particle focusing positions, and the codes can readily be extended to simulate two different particle types. This new numerical approach is significant because it opens the door to rapid geometric and flow rate optimization in order to improve the efficiency and purity of cell and particle sorting in biotechnology applications.

I. INTRODUCTION

High throughput cancer cell detection,1 the separation of leukocytes and erythrocytes from blood,2 and the selective separation of cultured cells3 represent some of the most pressing needs for modern biomedical applications.4–6 Motivated by these needs, numerous active and passive cell/particle sorting techniques have been developed in recent years. Active techniques utilize external force fields (e.g., electric fields or acoustics), whereas passive methods rely upon the inherent physical differences between the cells and the surrounding fluid as the separate tool.7 The advantage of passive techniques is that they can be simple, continuous, and eliminate the labeling procedure requirement. However, the geometric scale of such designs is critical. If their design has a microscale dimension, these devices will utilize substantially different physics in their operation. Critically, it is much easier to achieve high-velocity gradients in a microscale device, which drives the forces that enable focusing of cells to their equilibrium positions.4

Several experimental studies on microscale passive inertial separation devices have been conducted. Early experimental work on inertial separation was conducted by Matas et al. in the year 2004. They examined the particles' equilibrium positions due to inertial forces after traveling in a straight channel for different Reynolds (Re) numbers to confirm the findings of Segre and Silberberg. They concluded that by increasing the Re, the equilibrium positions would shift toward the channel walls.8 A few years later, in 2007, Di Carlo et al. proposed a mathematical model for the lift forces, which push cells toward the centerline and walls of a straight microchannel. Moreover, they investigated the influence of the Dean flow on the particles' equilibrium positions in a rectangular curved microchannel under different Re numbers.9 Alongside them, Seo et al. and Kuntaegowdanahalli and his co-workers reported particle separation in a spiral microchannel by coupling the inertial and Dean forces. Kuntaegowdanahalli et al. indicated that the equilibrium positions are affected by the ratio of the inertial lift forces to the Dean drag forces.10,11 Overall, these investigations have shown that if the microchannel is spiral, a Dean flow field occurs in the channel's cross section, resulting in forces that are helpful in the accumulation of cells/particles in predictable positions. Although many experimental studies have been done to improve the efficiency and sharpness of this passive separation process, it appears that, to date, there are very few studies that have obtained robust computational simulations of particle trajectories in the whole microchannel for these systems. In addition, the underlying physics of a particle's trajectory and its interaction with other particles (and the walls) is still relatively unknown.12

To address this gap, this study aims to simulate the inertial migration of particles/cells under the influence of hydrodynamic forces in a spiral microchannel. The simulations are expected to add fundamental understanding to this field and aid in optimizing the geometric design of such microchannels.

In the realm of simulating particle-laden flows, there are two main options available: (1) the classical Navier–Stokes (NS) approach and (2) the lattice Boltzmann method (LBM). The LBM is a statistical approach and, as such, may be preferred to the NS equations when the continuity approximation does not hold. Since the time marching in LBM is explicit and occurs in a two-step algorithm on a uniform lattice, which is time and memory-consuming, scientists tried to optimize it by combining it with other methods to lower its memory consumption.13 Several recent studies have employed an improved form of LBM for this application.12–17 For instance, Jiang et al. employed the immersed boundary method-lattice Boltzmann method (IBM-LBM) for numerically exploring particle trajectories and the fluid flow field in a serpentine microchannel.15 Ma et al. also utilized IBM-LBM for size-based cell sorting in a microchannel with two inlets and four outlets using a controllable asymmetric pinched flow.16 Haddadi et al. applied the LBM to numerically simulate the separation of cancer cells in a microchannel containing cavities, which was found to induce favorable vortexes.12 In 2020, Jiang et al. optimized the implementation of IBM-LBM for massive particle-laden flows to reduce computation time and memory. This was done by proposing several algorithms such as “symmetry,” “swap,” and “local point-to-node” and also improving the particle–pair collusion search algorithm.13 Nevertheless, researchers still have controversy over which method could be used for particle dynamic simulation in the microscale.

The NS approach or—more precisely—the arbitrary Lagrangian–Eulerian (ALE) formulation of it gives a stable and reliable solution if the density of the particles is higher than the conveying fluid.18,19 However, to successfully apply the NS approach, three fundamental issues must be overcome. First, when the mesh is fine enough to capture the particles, the computational cost becomes very high. Second, the effective applied forces induced by the fluid on the particles should be known a priori. Third, although it is known that changes in the conveying fluid velocity exert reaction forces, these have not yet been precisely determined from experimental findings. Nevertheless, if these issues are solved, the NS equations can provide a more accurate result than LBM.

Motivated by the commentary above, this study implements the ALE approach in an object-oriented code (OpenFOAM) with a finite volume method (FVM) to trace and predict particle/cell movements in microchannels—the results of which are compared against experimental data. In this study, the traditional NS equations are applied to particles with the same size and density as typical biological cells (i.e., and ) suspended in a fluid with the specifications similar to plasma. The density of the particles/cells and the conveying fluid investigated in this study meet the prerequisites of stability and reliability of the NS approach. The ALE formulation was selected because it can capture both phases (continuous and discrete) analyzed in this study. Importantly, this approach enables the results to be obtained with relatively low computational cost (i.e., by increasing the fluid element size to be larger than the particles). Moreover, to determine the velocity of each particle throughout the microchannel, which in turn determines the particle's displacement and equilibrium positions, the conservation of mass/momentum equations for both domains was solved explicitly. Thus, the innovation of this study is its new object-oriented codes, wherein the particle forces are considered within the momentum equations and applied in a way that shows good agreement with the experimental data of a recent study (with solid particles) by Rafeie et al.20 To showcase how this approach can be extended to biological cells, the particles were also considered to be flexible/deformable and simulated as a mixture of two different “cells” [e.g., similar in size and density to circulating tumor cells (CTCs) and red blood cells (RBCs)], which need to be separated from each other.

II. MODELS AND METHODS

In this study, both the continuous (the fluid) and the discrete phase (the particles/cells) were investigated. When the fluid starts to flow, it applies force to each of the suspended particles, which reduces the mismatch between their local velocities. In turn, the particles exert a reaction force to the continuous phase, which can change the fluid's velocity. This two-way coupling of the phases must be included in the equations for both phases. That leads to the arbitrary Lagrangian–Eulerian (ALE) formulation. That is, an Eulerian perspective has been applied for the fluid field, while the particles are tracked with a Lagrangian perspective. The ALE approach uses a finite element formulation, but unlike a pure Eulerian formulation, the computational system is not fixed in space. In addition, unlike a pure Lagrangian approach, the system is not attached to a material. Instead, the reference frame for the ALE's finite elements is arbitrarily assigned. In the current study, the Lagrangian perspective is used for the continuous conveying fluid, and the particles are traced via a moving Lagrangian reference frame. This allows the ALE formulation to overcome several of the shortcomings of traditional Lagrangian-based and Eulerian-based finite element simulations. On the other hand, if the particles collide with each other or the wall, it will create a change in the velocity and displacement directions. Thus, in addition to the two-way coupling (mentioned above), another two-way coupling is needed between particles and between the particles and the wall to account for these forces. Thus, the ALE formulation of this study trades computational cost for complexity in its four-way coupling.

A. The continuous phase: Governing equations

The rectangular cube of Fig. 1 represents the control volume V. The volume contains two phases , where the conveying fluid (i.e., water or plasma) within this cube has a volume equal to . As shown in Fig. 1, the discrete phase (particles) is depicted with spheres, each particle having a volume . If this control volume contains a particles, the subscript a (used in the following equation), represents the number of suspended cells/particles, each having a volume . Summing these volumes together gives the total occupying volume of the particles, .

FIG. 1.

Schematic of the fluid and particles in a control volume.

In the control volume, the conveying fluid has a velocity equal to u. As noted above, when u differs from the particle velocities (), it exerts inertial forces on the particles. Such forces are accounted for each particle with a linear momentum conservation equation (from a Lagrangian perspective). These forces cause each particle to accelerate and change their velocity. In turn, the reaction of these forces is exerted on the fluid domain in the microscale, where they are not negligible. These reaction forces, in turn, change the velocity profile and gradient of the plasma. The continuity and the Navier–Stokes equations for the fluid phase are as below.

1. Continuity

The simplified form of the conservation of mass for an incompressible fluid is as follows:21

| (1) |

In Eq. (1), represents the conveying fluid's density, is its velocity vector, and is the volume fraction of the fluid in the control volume.

2. Conservation of momentum

The well-known Navier–Stokes (NS) equation for an incompressible fluid can be represented by the following:21

| (2) |

In the above equation, and F represent the stress tensor, hydrostatic pressure, gravitational acceleration, and the reaction volumetric force, respectively. It is noteworthy that F is exerted to the fluid by the discrete phase except for stress, hydrostatic pressure, and buoyancy forces. the stress tensor, in turn, is given by22

| (3) |

In Eq. (3), is the kinematic viscosity and represents the Kronecker delta. The force acting from the plasma to the cells and vice versa, F, is described as follows:21

| (4) |

is the volume of each particle and the total number of particles has been assumed to be a. The listed forces are the most important known forces in this scale.

B. The discrete phase: Governing equations

Applying the Lagrangian reference frame for each particle, the conservation of mass and linear and angular momentum will result in the following equations.

1. Conservation of mass

As depicted in Fig. 1, since the mass of particles is not being consumed or transformed to energy, it will remain constant over time as per the following equation:21

| (5) |

where is the density of that certain particle in the discrete phase and is its volume.

2. Conservation of linear momentum

As mentioned before, a four-way coupling was used to solve the domains' equations. In this way, the velocity of each particle is not only influenced by the distance to the neighboring particles and microchannel walls but also by the plasma velocity. As such, Eq. (6) describes this coupling by linking the change in velocity to these reaction forces,

| (6) |

More specifically, Eq. (6) links the particle velocity vector, v, to the total force induced to the particles by the conveying fluid, , the total force induced by the particles on the fluid, (which is equal to since they are action and reaction forces), and the impact force of the particles colliding with each other and with the wall, . The cohesion and van der Waals forces between particle–particle and wall–particle have been neglected since their order is not comparable with other forces. The expanded form of , the first term of Eq. (6), is

| (7) |

Each of these terms can be defined as follows.

a. The steady-state drag force

The first term on the right-hand side of Eq. (7) is the steady-state drag force, which only takes into account the drag induced to the particle due to constant relative velocity and the Laplacian of the conveying fluid,21

| (8) |

In the above equation, the effect of the volume fraction of plasma on the drag force has been taken into account by the first coefficient.23 The terms, , D, and represent, respectively, the plasma viscosity, the particle diameter, and the relative Reynolds number, which is defined as . Finally, is the drag factor, as proposed by Clift and Gauvin,24 which is particularly important for simulating biological cells, such as spherical CTCs, which can be calculated as follows:

| (9) |

As shown in Eq. (8), the drag force consists of two terms. The first term is the Stokes drag acting on the particles and the second term is the Faxen force that corrects and evaluates the effect of the particles on the curvature of the fluid's velocity profile at the location of each particle.

Since biological cells are not perfectly spherical, using an equivalent diameter in the equations is necessary (which is usually the volume-equivalent sphere diameter, ). Moreover, the drag factor due to the particular form of biological cells can vary, which can be captured with the equation described below:25

| (10) |

where is the cross-wise sphericity, which depends on the ratio of the two cross sections. The projected area of the particle in the flow direction, , is a function of the angle of inclination. The shape factor from Eq. (10) is a criterion that measures the degree of non-sphericity of the cells and is defined as , where is the equivalent sphere area and A is the actual surface area.

b. The lift force

The second term in Eq. (7) is the Saffman lift force, which is calculated as21

| (11) |

where is derived from the Mei lift force coefficient26 and is the curl of the fluid vector that is equal to ,

| (12) |

In the equation mentioned above, is the rotational Reynolds defined as .

c. The virtual mass force

The third term refers to the virtual mass force, which arises from the form drag due to relative acceleration,21

| (13) |

where and are time derivatives of the fluid and particle velocities, respectively.

d. The Basset force

The fourth term on the right side of Eq. (7) is the history or Basset force, which is a type of drag force developed due to the fluid's viscous effects. It carries the influence of the boundary layer changes at each time step from the beginning to the current time due to the changes of the relative velocity with time,21

| (14) |

The Basset coefficient is described as27

| (15) |

In Eq. (15), represents the non-dimensional Strouhal number, which is defined as . In this relationship, f is the oscillation frequency and is the momentum response time defined to be . Since the flow is not oscillatory in a microchannel, the Strouhal number tends to infinity, which makes .

The Basset force accounts for the effect of changes of the developed boundary layer on the particle. It is calculated in each previous time step and is then added to the current time step. It is notable that the coefficient from each previously calculated term, which should be summed, constantly changes for every time step. Since implementing this force in a discrete manner is difficult, the following equation is proposed in this research:

| (16) |

where N is the total number of time steps and is the time step, and and are the plasma and particle velocity at time , respectively. The proposed coefficient in this study is a linear average of the upper and lower bound of the above-mentioned dynamic coefficients.

e. The Magnus force

The particle's rotation due to the collisions or the difference of pressure distribution on its surface, which in turn is a resultant of the plasma velocity gradient, will create the Magnus lift force that is defined as21

| (17) |

In the above equation, is the particle angular velocity vector and the Magnus lift coefficient, , is defined to be28

| (18) |

f. The stress, buoyancy, and pressure gradient forces

The last three terms of Eq. (7) are defined to be , , and .

Table I gives a summary of the fluid-induced forces, . The distinguishing feature of this research is that it takes these forces into account in a complete and detailed form to increase force determination accuracy. For example, if we assume that the fluid and the particle velocity vectors are in the y direction and the quantity of u is greater than the particle's velocity , a schematic of the fluid-induced forces, , is depicted in Fig. 2. Notably, the direction of the particle's angular velocity vector and fluids curl should be known to precisely predict each force's direction. Also, if the particles collide with other particles or the microchannel's wall, additional forces such as and should be considered in Eq. (6).

TABLE I.

Summary of the forces exerted to each particle by the conveying fluid, ff.

| Force | Equations from Refs. 21 and 23–28 | |

|---|---|---|

| Steady-state drag force | ||

| Drag factor for spherical particles (e.g., CTCs) | ||

| Drag factor for non-spherical particles (e.g., RBCs) | ||

| Lift force | fLift = Vp ρc Cl[(u − v) × ωc] | |

| Lift coefficient | ||

| Virtual mass force | ||

| Basset force | ||

| Basset coefficient | CB = 1 − 0.527(1 − exp( − 0.14 Re Sl0.82)2.5) | |

| Magnus force | ||

| Magnus lift coefficient | ||

| Stress force | ||

| Buoyancy force | fBuoyancy = ρcgVp | |

| Pressure gradient force | ||

FIG. 2.

A schematic of the fluid-induced forces.

Focusing on Table I and Fig. 2, when the particles lag behind the conveying fluid, the inertial forces such as drag, Basset, and virtual mass force directly help the particles to accelerate and increase their velocity. This increase may lead to a change in the sign of the relative velocity and thus reverse the direction of the drag, Magnus, and lift forces, which would cause particle deceleration. Thus, both the magnitude and direction of these forces are subject to change before balance is achieved. Taken together, in a well-designed inertial microfluidic device, this balance should be achieved well before the exit (usually a bifurcation) of the channel. Thus, understanding the underlying physical forces of particle acceleration can improve both the design and operation of inertial microfluidic devices.

As described earlier in Eq. (6), and arise from the particle colliding with other cells or the microchannel wall. These impact forces can be divided into a tangential and normal components acting on the surface of the particle. The normal force is aligned with the line connecting the two centers of the colliding cells, and the tangential force is perpendicular to it. Since colliding cells are not rigid, they can overlap each other. The amount of this overlap is represented by , a parameter that indicates the degree of deformation. A soft sphere model that consists of a spring–slider–dashpot system is used to model and .29 Thus, the stiffness, k, the friction factor, f, and the damping coefficient, , should be defined for each colliding pair.

g. Particle–particle collisions

Since the colliding particle may impact q other particles at the same time, the equations for should account for the sum of all the impact forces in the above-mentioned perpendicular directions. So is described as21

| (19) |

For a 3D spherical particle, based on the Hertzian contact theory, the normal component of the particle impact force is defined to be21

| (20) |

Assuming that a collision of particles l and m has occurred, assuming that the suffixes l and m designate the corresponding parameters of each particle, then is the relative velocity vector of particles l and m, and is the nonlinear spring stiffness in the normal direction. In this calculation, is the normal overlap, is the normal damping coefficient, and finally, n is a unit vector in the direction of a line connecting the centers of the colliding particles. In turn, can be defined as30

| (21) |

in which , and D are, respectively, Young's modulus, Poisson’s ratio, and the diameter of particles l and m. According to the findings of Tsuji et al., is related to and is equal to . Moreover, for a nonlinear spring, it can be determined as31

| (22) |

where is a constant related to the restitution coefficient as and is the mass of particle l.

In addition, the term is described as21

| (23) |

in which is the nonlinear spring stiffness in the tangential direction, is the overlap projection in the tangential direction, is the tangent damping coefficient, is the particles angular velocity vector, and is the slip velocity vector of the contact point and described to be . According to the theory presented by Mindlin via Crowe et al., can be determined as21

| (24) |

where is the shear modulus and is defined as for each particle.

h. Particle–wall collisions

To obtain the equations for this case, since the channel walls are stationary, one could simplify Eqs. (19)–(24) by changing the suffix m to W and substituting and .

3. Conservation of angular momentum

The conservation of angular momentum equation for the particle mentioned above can be written as21

| (25) |

where is the moment of inertia of the particle determined as , and is the torque caused by the tangential collision force defined as . The second term on the right-hand side of the equation is the torque arising from the shear stress distribution.

Taken together, the above-mentioned transient pressure–velocity coupled partial differential equations and contact forces can now be discretized and solved using a four-way coupling to calculate them simultaneously. The results from this approach will enable predictions to be made for the position, transitional, and angular velocity of each particle and also the velocity contours and vortices of the fluid domain throughout the microchannel.

C. Simulation procedure

To visualize the flow field and the Dean vortices throughout the whole channel and also to track the particles and cells as they travel to their equilibrium positions, the code for the microchannel geometry was written in OpenFOAM. The reason for choosing this software was that it allows total control of the codes; thus, the equations for this study and the particle forces can be manipulated as needed. Another advantage of this software is that it is an open-source C++ code operating in Linux under the GNU General Public License by the OpenFOAM Foundation. OpenFOAM has the capability of being coupled with LIGGGHTS for computational fluid dynamics-discrete element method (CFD-DEM) problems to reduce the computational time and also to model the non-spherical contact forces. However, the main drawback of such coupling is that it cannot consider all of the interaction forces that are important in the microscale. Overall, this type of coupling is beneficial in the molecular scales where cohesion and van der Waals forces should be calculated.

To make OpenFOAM applicable to the circumstances of this research, two stages were done. First, to obtain the four-way coupling, the codes for each of the aforementioned forces induced by the fluid [Eqs. (8)–(18)] and the soft contact model [Eqs. (19)–(24)] were written, debugged, compiled, and validated against experimental data. Next, the codes were modified to include two different types of particles and their relevant particle–particle interactions.

1. Microchannel and particle specifications

The investigated geometry is an eight-loop spiral microchannel with one inlet and two outlets, as illustrated in Fig. 3(a). The reason for using this geometry is to verify it with the experimental spiral microchannel of Rafeie et al., which consisted of eight loops.20 Similar to the design by Rafeie et al., the straight entry of the channel was considered to ensure that the flow becomes fully developed before entering the spiral part. In this study, the microchannel has been redesigned twice: once with a rectangular cross section [Fig. 3(b)] and second with a trapezoidal one with the dimensions shown in Fig. 3(c); the codes for each geometry are written in OpenFOAM. Lines a and b that have the same alignment of x and z axes divide the cross sections into four regions, and their intersection point is the center of each cross-sectional area.

FIG. 3.

(a) The geometry of the spiral microchannel; (b) Rectangular cross-sectional areas of the microchannel and (c) Trapezoidal cross-sectional areas of the microchannel.

In the experimental setting of Rafeie et al., water was employed instead of plasma and polystyrene microbeads as surrogates to real cells.20 Thus, to investigate a more realistic situation, the present simulation investigated three cases. Initially, to verify the written codes of this study, a suspension of water and beads, the same as the situation experimentally tested by Rafeie and colleagues, was investigated. Next, to approach a more accurate situation, a suspension containing a fluid similar to plasma (instead of water) with particles similar to CTCs (i.e., MCF7 cells, which are breast cancer cells) was simulated. Finally, a third simulation was done where particles similar to RBCs were also added to the previous suspension. The assumed physical and mechanical properties of the cells are listed in Table II.32–38

TABLE II.

Physical and mechanical properties of commonly used cells/particles in microscale separation devices.

| Cell type | Diameter (μm) | Density | Young's modulus (KPa) | Poisson ratio | Friction factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polystyrene | 15 | 1050 | 3.3 × 106 | 0.33 | 0.515 |

| CTC (i.e., MCF7) | 15 | 1066 | 1.8 | 0.5 | 0.245 |

| RBC | 5 | 1110 | 0.143 | 0.5 | 0.206 |

As shown (Table II), the CTCs are not only denser but notably less rigid and with lower friction factors compared to polystyrene particles. RBCs are smaller, denser, and less rigid than the CTCs or polystyrene particles. In all simulations, the fluid flow rate, Q, ranged from to . In case 1, the assumed specifications of water were the same as that of Rafeie et al., which leads Re to over a range between and . The density and viscosity of plasma were assumed to be and at , respectively, resulting in Re values over the range of 11–243.

2. Solution procedure

The finite volume method was used to discretize the relevant partial differential equations. The discretization scheme used for time, divergence, gradient, and the Laplacian terms were Euler, Upwind, Gauss, and the Gauss-linear corrected schemes, respectively. The PIMPLE scheme was applied to solve the transient pressure–velocity coupled equations. The fluid and the particles were assumed to be stagnant initially. A Dirichlet velocity boundary condition was applied to the inlet. A pressure boundary condition equal to the atmospheric pressure was placed at the microchannel outlets, and the no-slip condition was imposed at the microchannel walls. The numerical computations and simulations were done using parallel processing in the high-performance computing facility of the University of New South Wales (UNSW) and the Australian government clusters (e.g., Trentino and Raijin). To reach mesh independence, the element sizes were investigated in two situations: the elements' dimensions being larger than the particles' diameter and vice versa. For this part, the following considerations were made to ensure accurate numerical results: reducing the angle between the flow direction and the meshes and monitoring orthogonality, smoothness, and aspect ratio of elements while avoiding skewness.

III. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

In this section, first, the mesh independence for both the Eulerian and the Lagrangian phase was investigated. Next, for the chosen mesh size, the results of simulations for two different rectangular and trapezoidal microchannel cross sections are presented (see Sec. II C 1). For the rectangular cross section, polystyrene particles, in the first case, and particles similar to CTCs, in the second case, were simulated and driven within the channel. For the trapezoidal cross section, three cases of particle combination within the microchannel were investigated: (1) particles similar to polystyrene, (2) particles similar to CTCs, and (3) a mixture of particles similar to two cell types (RBC and CTCs).

A. Mesh independence

To ensure the results are independent of the element size, mesh independence was investigated for both phases. As listed in Table III, eight different mesh densities were investigated.

TABLE III.

Mesh sizes investigated in the simulation.

| Mesh indication | Element size | |

|---|---|---|

| Rectangular microchannel | Trapezoidal microchannel | |

| A | 37.5 × 40 × 30 | 37.5 × 40 × 20–37.5 × 40 × 32.5 |

| B | 24 × 32 × 30 | 24 × 32 × 20–24 × 32 × 32.5 |

| C | 30 × 32 × 24 | 30 × 32 × 16–30 × 32 × 26 |

| D | 20 × 22.7 × 17.1 | 20 × 22.7 × 11.4–20 × 22.7 × 18.6 |

| E | 15 × 16 × 12 | 15 × 16 × 8–15 × 16 × 13 |

| F | 10 × 10.7 × 8 | 10 × 10.7 × 5.3–10 × 10.7 × 8.7 |

| G | 7.5 × 8 × 6 | 7.5 × 8 × 4–7.5 × 8 × 6.5 |

| H | 3.8 × 4 × 3 | 5 × 5.4 × 2.7–5 × 5.4 × 4.3 |

To avoid skewness, the spiral was divided into quarters for all the mesh densities mentioned above, each having their unique division numbers increasing with the quarter length growth.

1. Continuous phase

For this purpose, considering the conveying fluid within the microchannel to be water, the velocity profile of the covarying fluid in the y direction at cross section B-B shown in Fig. 3(a) for is investigated and compared for mesh densities, varying from A to H for both rectangular and trapezoidal cross sections [see Figs. 4(a) and 4(b)].

FIG. 4.

The velocity profile in the y direction at the B-B section for (a) rectangular microchannel in the middle of the width and (b) trapezoidal microchannel in one-sixth of the width near the outer wall.

As shown in Fig. 4(b), by reducing the element size to (which is larger than the diameter of the CTCs), the fluid velocity becomes independent of the mesh size with less than 2% error, and the Eulerian phase result is independent of the mesh size. In addition, for this mesh size, the particles' equilibrium positions are not dependent on the grid size. Thus, the Lagrangian phase mesh independence is achieved, and the results agree well with the experimental data (see Figs. 5–7).

FIG. 5.

Particle positions for different mesh sizes at the end of the straight entry of the spiral microchannel: (a) rectangular microchannel and (b) trapezoidal microchannel.

FIG. 6.

Particle initial distribution and equilibrium positions in the rectangular spiral microchannel (a) at , (b) at , and (c) the experimental findings of particles equilibrium positions from Rafeie et al. Reprinted with permission from Rafeie et al., Biomicrofluidics, 13, 034117 (2019). Copyright 2019 AIP Publishing LLC.

FIG. 7.

Particle distribution and equilibrium positions in a trapezoidal spiral microchannel: (a) at , (b) at , and (c) Experimental observations of Rafeie et al. Reprinted with permission from Rafeie et al., Biomicrofluidics, 13, 034117 (2019). Copyright 2019 AIP Publishing LLC.

2. Discrete phase

According to the findings of Segre and Silberberg, particles traveling in a straight, circular microchannel tend to focus as an annulus after traveling a certain distance in the microchannel.39 For the situation investigated here, this obligatory traveling length for the particles to migrate is about , which is less than the length of the straight entry of the spiral. Moloudi et al. expanded the work done by Segre and Silberberg and investigated the particles' equilibrium positions traveling in a straight microchannel with rectangular and trapezoidal cross sections. They revealed that the particles tend to focus in an equilibrium spectrum. This spectrum's location varies with the conveying fluid's Reynolds number and the particle size (i.e., the ratio of the particle to the shortest height of the channel).40 They concluded that for particles with a diameter equal to , at relatively low Res (equal to 53), the particles traveling in a rectangular microchannel focus in the middle of the microchannel. For a trapezoidal straight microchannel, when the particles had a diameter and Re equal to 20, the particles tend to focus in a line somewhere between the middle and the outer wall of the microchannel.

To investigate Lagrangian phase mesh independence, five particles similar to polystyrene were positioned at five different coordinates at the A-A section of Fig. 3. One was placed in the center of the cross-sectional area at the microchannel entry, and the other four were placed with a offset from its center along the a and b lines. These initial conditions were used for both the rectangular cross section and the trapezoidal cross section, as discussed below.

As shown in Fig. 5(a), for Re equal to 23, the particles flowing in fluids having eight different mesh densities have several equilibrium positions, mostly not having any specific arrangement. However, for the C and H mesh densities, this defers since particles not only focus in the middle of the channel but also tend to migrate to two points align the z axis, with about a offset from the x axis on both sides. Interestingly, the particles initially placed on the x axis all tend to settle down in the point having a negative z-component. This type of focusing matches the experimental observation of Moloudi et al.40 The mesh independence for the trapezoidal microchannel is investigated in Fig. 5(b). Once again, it is seen that for Re equal to almost 24, among several mesh densities investigated, only two cases maintain the same result, following a certain rule, not having chaotic equilibrium positions, and also matching with the experimental observation of Moloudi et al.40 For this cross section, the initially placed particles have shifted toward the outer wall.

In this simulation, the fluid field results remain independent of the element size by reducing the mesh size further from the C mesh density. However, the particles’ equilibrium positions in the Lagrangian phase seem to become illogical unless the mesh dimension is fine enough to be at least fivefold less than the particle's diameter. In other words, mesh independence was obtained for two situations: (1) when the smallest dimension of the fluid element is larger than the particle diameter (while the Eulerian phase results do not any further rely on the mesh size), and (2) when the smallest dimension of the fluid element was five times smaller than the particle diameter (mesh density H). Moreover, obtaining results with such a fine mesh requires a large amount of computational allocation, even when processing in parallel with high-performance clusters, which makes it unreasonable to be a beneficial substitute for experimental testing. Therefore, it was found that the best choice involved decreasing the element size to the degree that the shortest length of the fluid element is larger than the biggest cell diameter. Moreover, at least one dimension of the element should be greater or equal to twice the particle diameter to allow at least one particle collision. Thus, for the rectangular microchannel and the trapezoidal cross section, the C density was chosen for further simulations.

B. Rigid particle simulation

In the next step to validate the written codes, conditions similar to the experimental work done by Rafeie et al.20 were simulated. For the same fluid specifications and the same five particles placed at the aforementioned positions described in Sec. III A, the particle movements for both the rectangular and trapezoidal cross sections were investigated.

1. The rectangular microchannel

In this part, the rectangular microchannel geometry containing the particles was simulated. This channel is illustrated in Fig. 3(b) and described in Sec. II C 1. Figures 6(a) and 6(b) depict and compare the initial positions at the A-A section (shown with subscripts “I” and with pale colors) with the final equilibrium positions at the C-C section (marked with subscripts “F” and bold colors) for Q values equal to and . The experimental findings of Rafeie et al.20 are presented in Fig. 6(c) with dashed boxes highlighting the relevant flow rates for comparison. For , by comparing the equilibrium positions obtained by simulation [Fig. 6(a)] with those of the experimental results [Fig. 6(c)], a very reasonable match is seen; that is, the particles migrate toward the inner wall and settle at a distance about 120–150 μm away from the inner wall.

Table IV compares the equilibrium spectrum formed by particles in numerical simulation and experimental observation. All distances are measured from the inner wall. As shown in this table, the focusing positions shift from the inner wall to the outer wall by increasing the flow rate. It starts at and the particles approach the outer wall at . By further increasing the flow rate, the equilibrium position of the particles almost remains constant [see also Fig. 6(c)]. This is while in our simulation, this critical flow rate at which the particles start to shift toward the outer wall is higher and is about .

TABLE IV.

Comparison between the simulation results and experimental data.20

| Flow rate | Equilibrium spectrum of the rectangular microchannel (μm) | Equilibrium spectrum of the trapezoidal microchannel (μm) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Numerical simulation | Experimental results | Numerical simulation | Experimental results | |

| 0.5 | 60–86 | 55–97 | 145–308 | 128–306 |

| 1 | 63–102 | 60–105 | 113–158 | 96–186 |

| 1.5 | 70–132 | 75–140 | 36–102 | 24–144 |

| 2 | 88–144 | 90–170 | 46–112 | 24–120 |

| 2.5 | 99–148 | 105–150 | 65–136 | 78–486 |

| 3 | 121–152 | 120–167.5 | 129–308 | 438–504 |

| 3.5 | 155–190 | 170–230 | 286–477 | 462–516 |

| 4 | 196–257 | 250–305 | 455–502 | 462–519 |

| 5 | 271–330 | 330–405 | 469–525 | 480–531 |

| 6 | 367–429 | 400–470 | 485–544 | 486–534 |

| 7 | 409–480 | 460–518 | 486–540 | 486–540 |

| 8 | 445–510 | 460–520 | 482–542 | 486–540 |

| 9 | 448–512 | 425–525 | 484–540 | 468–534 |

It is observed in Fig. 6(b) that the particles’ equilibrium positions for is almost similar to when the experimental flow rate is equal to and the particles focus closer to the center of the microchannel. To investigate the effect of each particle force on the equilibrium positions, they were added one by one in the simulation codes. It was revealed that the particles did not shift toward the outer wall for high flow rates when excluding the Basset force. A possible explanation for this occurrence is that the Basset force takes on a dominating role in shifting the particles to the outer wall.

2. The trapezoidal microchannel

In this section, simulations were done to validate the written codes for a trapezoidal asymmetric cross-sectional microchannel depicted in Fig. 3(c). The dimensions of this microchannel were the same as the dimensions of one of the microchannels, which was experimentally examined by Rafeie et al.20 The results of the simulation for when is presented in Fig. 7(a). By comparing these results with the results of fluorescent particles obtained by Rafeie et al. [dashed boxes highlighting the relevant flow rates for comparison in Fig. 7(c)], it is seen that for this flow rate, the agreement is reasonable, and the particles shift toward the inner wall of the microchannel and rest at a distance between 36 and 102 μm before reaching the inner wall.

As shown in Table IV, in this study, the critical flow rate in which the particles tend to change their equilibrium position from the inner wall toward the outer wall occurs at ; this is higher than what was experimentally observed () and is shown in Fig. 7(c). However, for flow rates higher than , both simulation and experimental results agree well; for instance, the results describing the initial and final positions of the particles at the A-A section and C-C section for is depicted in Fig. 7(b).

C. Deformable particle simulation

In order to investigate a condition closer to clinical reality, the polystyrene beads were replaced with particles similar to CTCs to study the effect of particle deformability on inertial migration. In addition, the conveying fluid was no longer water and was changed to a fluid having specifications similar to plasma as described in Sec. II C 1. Same as Sec. III B, these five particles were positioned at the coordinates mentioned above of polystyrene beads and were repeated for both the rectangular and the trapezoidal cross sections, as discussed below.

1. The rectangular microchannel

Although the flow regime is laminar in all of the simulations, a secondary flow arises due to the channel's curvature causing a centrifugal force. This secondary flow is the Dean flow that forms two counter-rotating vortices, as depicted in Fig. 8(a). The induced circulation caused by these vortices leads to useful inertial forces that can be used to help focus particles. Thus, the water (or plasma) velocity profile has some secondary velocity turning points, often called inflection points (IPs), which play a significant role in predicting the particles’ equilibrium positions. A characteristic velocity distribution and vectors of the secondary flow at in the B-B cross section are shown in Fig. 8(b). It should be noted that by increasing the Re number, the magnitude of the vortices increases.

FIG. 8.

(a) The distribution of the -component of the vorticity of the secondary flow in the B-B section. (b) The distribution of the -component of the secondary flow velocity in the B-B section at .

The velocity profile in the middle of this cross section including the inflection points (red dots) for is shown in Fig. 9(a). The maximum positive velocity in the x direction occurs near the sidewalls and is about 7.3-fold greater than the central maximum negative velocity. This differs from the computational findings presented by Rafeie et al.20 The reason for this occurrence, besides considering two different types of fluids (water and plasma), may be due to the high speed of the main flow in the y direction in the central regions in comparison to the secondary flow that could result in driving the Dean flow away and preventing it from flowing freely. As shown in Fig. 9(b), the region formed by IPs in our study for each flow rate is concentrated near the central line A, having a notable distance from the top and bottom walls, and by increasing the flow rate, this region grows and IPs shift toward the sidewalls.

FIG. 9.

(a) Velocity profile and IPs in the middle of the B-B section at . (b) Inflection points for different flow rates.

Investigating the particles’ equilibrium positions, the simulation results indicate that when the flow rate equals , the five aforementioned particles shift and focus near the center after traveling in the straight part of the microchannel. They remain there while not changing their streamlines until they reach the end of the microchannel and exit from the inner outlet. Since, for this case, Re is low, the Dean flow is weak, and the inertial lift may play the main role in determining the equilibrium positions. For , the cells shift and focus near the inner wall after traveling a half loop and remain there for the rest of the route. With the increase of the Re number by changing the flow rate from to , the particles migrate toward the center of the cross section, settling in a region about one-third of the width before completely reaching the inner wall after traveling three-quarter loops. Then the cells get trapped in the stagnation area formed by IPs. Table III shows the initial coordinates of the particles at the “initial” A-A section (as defined in Fig. 3) for the flow rates equal to 6 and . In addition, it reports their “final” coordinates (at section C-C of Fig. 3). Since the particles are located at different positions and constantly change their streamlines, it is expected that they may not reach the outlets at the same time. As shown in Table V, the particles gradually tend to focus near the outer wall by further increasing the Re. Interestingly, for these flow rates, the particles circulate and migrate to the inner and outer walls many times before reaching the end of the channel. For instance, for , the particles circulate eight times around the cross section of the channel. In addition, the more loops the particles travel, the more time they spend near the outer wall.

TABLE V.

The initial and final coordinates of particles for trapezoidal spiral at cross section C-C for and .

| Flow rate | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Particle number | Initial position (μm) | Final position (μm) | Initial position (μm) | Final position (μm) | ||||

| x | z | x | z | x | z | x | z | |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | −137 | −21 | 0 | 0 | 170 | 20 |

| 2 | 0 | −30 | −67 | −23 | 0 | −30 | 206 | −21 |

| 3 | 0 | 30 | −148 | 15 | 0 | 30 | 186 | −26 |

| 4 | 30 | 0 | −112 | 22 | 30 | 0 | 195 | 23 |

| 5 | −30 | 0 | −108 | 24 | −30 | 0 | 162 | −24 |

Figures 10(a) and 10(b) compares the initial positions at the A-A section (shown with subscript “I” and with pale colors) with the equilibrium positions at the C-C section (illustrated with subscript “F” and bold colors) for Q equal to and . To investigate their migration, each particle is marked with its allocated number listed in Table V and an initial (I) or final (F) position subscript.

FIG. 10.

Particles’ initial distribution and equilibrium positions in the rectangular spiral microchannel (a) at and (b) at .

Two important points should be considered in comparing Fig. 10(a) with the results of rigid particle simulation reported in Sec. III B 1 [Fig. 6(b)]. The first is that in Sec. III B 1, we used rigid polystyrene particles, whereas in this section, deformable particles were used. The second is that the results of Figs. 6(a) and 6(b) are for water, whereas Figs. 10(a) and 10(b) use the physical properties of plasma as the conveying fluid. Even though the inlet velocity and geometry are similar in both mentioned sections, these two differences will lead to lower Reynolds numbers for equal flow rates. Having lower Re numbers, in turn, could cause an increase in the critical flow rate at which the particles start to shift their equilibrium positions from the inner wall toward the outer wall.

2. The trapezoidal microchannel

Since the Dean flow aids particle focusing, researchers have proposed that trapezoidal cross sections might be used to further enhance the focusing forces by adding flow asymmetry. As illustrated by the trapezoidal design shown in Fig. 11(a), this is indeed the case since strong, counter-rotating vorticity occurs due to the eccentricity of the flow and the forces. The velocity distribution and vectors of the secondary flow at in the B-B cross section for the trapezoidal cross section is depicted in Fig. 11(b). The depicted vectors show the effect of the centrifugal force in forming the two above-mentioned vorticities.

FIG. 11.

(a) Vorticity distribution in the B-B section. (b) Secondary flow velocity distribution in the B-B section.

The main flow distribution is depicted in Fig. 12(a) as illustrated; in the regions where the main flow has a high velocity in the y direction, the velocity of the secondary flow in the x direction decreases. The velocity profile in the one-sixth of the width near the outer wall of this cross section is shown in Fig. 12(b). The maximum velocity of the secondary flow at the side paths is about 6.9-fold greater than the maximum negative velocity formed in the central regions. This, as mentioned earlier, could be due to the greater velocity in the mainstream in the y direction. Figure 12(c) depicts IPs of the simulation for flow rates between and , since the cross section is not symmetrical; for different Re numbers, the IPs form non-symmetrical contours compared to the rectangular cross section of Fig. 9(b). Moreover, when the flow rate decreases, the IPs concentrate near line A, increasing their distance from the sidewalls.

FIG. 12.

(a) Main flow velocity distribution in the B-B section. (b) Velocity profile and IPs in one-sixth of the width near the outer wall of the B-B section at . (c) Inflection points for different flow rates.

Once again, for this cross section, when Q equals , the particles concentrate in the central region, having traveled the straight portion of the channel's entry. This occurrence confirms that for a Re equal to , the velocity of each particle is lower than the velocity of the conveying fluid. Their relative velocity is positive; therefore, similar to the results obtained for the rectangular cross section, the Saffman lift force calculated in Eq. (11) pushes the particles toward the central regions inclining to the inner wall. By increasing the flow rate from to , the Dean flow plays a larger role in specifying the particles’ equilibrium positions. This leads to forcing them to migrate toward the inner wall after traveling three loops and getting trapped in the region formed by IPs. As depicted in Fig. 13(a), for , the number of the required loops to reach the equilibrium positions reduces to less than two loops. In Fig. 13(b), it can be seen that as particles trace their third loop, and they tend to focus close to the inner wall of the microchannel.

FIG. 13.

trapezoidal microchannel at : (ai) Upper view of particle positions in the first loop, (aii) cross section of the specified area in the first loop, (bi) upper view of particle positions in the third loop, and (bii) cross section of the specified area in the third loop.

By increasing Re further, not only do the Basset force and Dean force become dominant but the relative velocity also seems to become negative, which in turn leads to reversing the direction of the Saffman lift force. These forces cause the particles to accumulate near the outer walls gradually. The initial positions and the results for the equilibrium positions of the five particles as mentioned earlier at cross section C-C for are listed in Table VI and depicted in Fig. 14(a). The initial positions at the A-A section are shown with pale colors, while the equilibrium positions at the C-C section are illustrated with bold colors. As shown, for this cross section, the particles migrate toward the low-speed area of the secondary Dean flow formed by the IPs and get trapped in that region. For this trapezoidal cross section, at , particle circulation from the inner wall toward the outer wall occurs five times, which is fewer than those of the rectangular cross section with the same flow rate. Once again, as the traveling distance through the channel increases, the particles tend to focus near the outer wall more quickly.

TABLE VI.

Particle locations for the trapezoidal spiral at cross section C-C (defined in Fig. 3), for flow rates of 6 and .

| Flow rate | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Particle number | Initial position (μm) | Final position (μm) | Initial position (μm) | Final position (μm) | ||||

| x | z | x | z | x | z | x | z | |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 126 | −5 | 0 | 0 | −50 | −32 |

| 2 | 0 | −30 | 174 | −12 | 0 | −30 | −20 | −31 |

| 3 | 0 | 30 | 145 | 15 | 250 | −30 | 233 | −32 |

| 4 | 30 | 0 | 181 | −20 | −250 | −30 | −271 | −31 |

| 5 | −30 | 0 | 113 | −9 | 0 | 30 | −10 | −32 |

| 6 | … | … | … | … | 250 | 70 | 222. | −32 |

| 7 | … | … | … | … | −250 | 30 | −261 | −29 |

| 8 | … | … | … | … | 30 | 0 | −16 | −32 |

| 9 | … | … | … | … | −30 | 0 | −127 | −32 |

FIG. 14.

Particle distribution and equilibrium positions in a trapezoidal spiral microchannel for (a) and (b) .

Next, to investigate the equilibrium position for more particles, four particles were added to the initial particles near the microchannel's corners. For , their initial and equilibrium positions are listed in Table VI and depicted in Fig. 14(b).

As shown in Fig. 14(b), for a low Re (), these four newly added particles do not tend to focus in the central region of the cross section. This could be the effect of not having a large number of particles in the corners, which eliminates the effect of particle collisions, which in turn could force the particles to change their streamlines. In addition, the findings indicate that after traveling the whole channel, the particles not only move in the x direction but tend to settle down in the z direction, which could be due to gravity. Rafeie et al.20 believed that gravity has a neglectable effect in microscale devices; thus, in their experimental setup, the microchannel was rotated 90° clockwise around the x axis before the test; this could have been the reason why they have not observed and reported the influence of gravity in low flow rates.

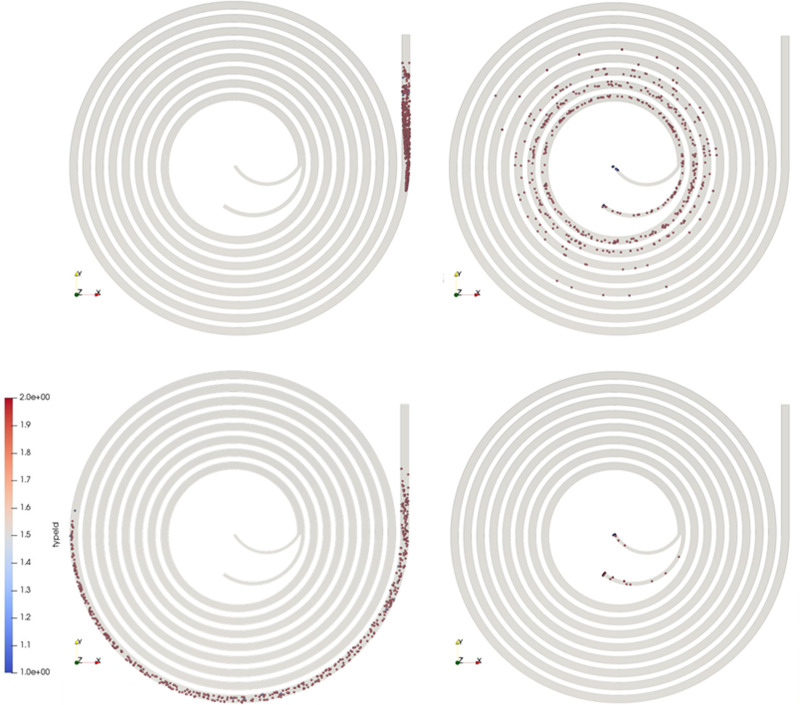

D. Deformable particle separation simulation

The next step of this study was to simulate the separation of two types of particles (e.g., particles with the size, shape, and deformity similar to CTCs and RBCs). When there are many particles in the microchannel, the influence of particle collision on the particle motion becomes important. Thus, in this part, the codes were modified so that the equations could be solved for two different types of particles with different properties. In addition, we had to consider two types of particle–particle impacts: (1) the impact between two similar particles colliding with each other and (2) the impact of two different types of particles colliding with each other. We simulated the movement of 9 particles that were similar to CTC cells and with 489 particles similar to RBCs within the trapezoidal microchannel. The CTC-like particles were initially placed at the same positions as Fig. 14(b), and the 489 RBC-like particles were initially arranged in a manner to have a offset with other particles in each column. They also had a offset from the inner and outer walls of the microchannel, as shown in Fig. 15(a).

FIG. 15.

RBC- and CTC-like particle distribution in the trapezoidal cross section of a spiral microchannel for (a) their initial positions (e.g., the A-A section as defined in Fig. 3) and (b) their equilibrium positions (e.g., at section C-C as defined in Fig. 3).

As depicted in Fig. 15(b), at , RBC- and CTC-like particles tend to focus in two different regions. As illustrated in Figs. 16(a) and 16(b), after both types of particles start to flow in the microchannel, they collide and do not remain in their initial streamlines. It is shown in Figs. 15(b) and 16(c) that the RBC-like particles mainly focus near the outer wall after traveling almost seven loops and exit at the outer outlet. In contrast, the CTC-like particles migrate toward the inner wall and focus near the inner outlet [see Fig. 16(d)]. For the same geometry, Warkiani et al. used deformable particles [actual CTCs and white blood cells (WBCs)]. In their examination, when the flow rate was equal to , the CTCs being larger and stiffer than the WBCs (same as this study that simulates deformable particles similar to CTCs and RBCs) tend to focus toward the inner wall while the WBCs migrated toward the outer wall.41

FIG. 16.

RBC- and CTC-like particles flowing through a trapezoidal spiral microchannel for Q = 0.5 ml/min: (a) particle distribution near the entry, (b) particle distribution at the first loop, (c) particle distribution near the end, and (d) particle distribution at the end of the separation process.

Interestingly, by comparing the results for this case with when having only particles with the specifications of CTC, the effects of cell collisions are thoroughly observed. In addition, the migration of the particles in the gravity direction reinforces the hypothesis of gravity's dominant effect in predicting the particles’ equilibrium positions in low Res. The separation efficiency, which is defined as the ratio of the target cells imported into the microchannel to the target cells collected at the desired outlet, is ∼88.9%. Furthermore, the purity of separation, which is the ratio of the target cells to total cells, is equal to 29%. Since the particle size, density, Young's modulus, and friction factor are different, the quantity of each inertial particle force varies; this may be a plausible reason for having two distinct equilibrium positions for each particle type. Nevertheless, particle collision disturbs this type of separation, reducing its efficiency and avoiding it from being 100%.

IV. CONCLUSIONS

In this study, C++ object-oriented codes in OpenFOAM were written to simulate particle-laden flows in inertial microfluidic channels. This was motivated by a lack of accurate simulation software for these emerging applications. The innovation of this research is that it presents C++ codes that consider a four-way coupling between NS equations and particles’ mass and momentum conservation equations, including the particle forces in a complete and modified form. To the authors’ knowledge, this represents the first time all the known inertial forces that play a role in predicting particle equilibrium positions have been considered at each time step in an inertial microfluidics simulation. That includes the lift, drag, Faxen, virtual mass, Basset, Magnus, shear stress, buoyancy, and pressure gradient forces. Importantly, this study also accounts for the effect of the particle volume fraction, particle shape, and particle deformability in determining the inertial forces.

In addition to this fuller picture of the salient forces, the proposed approach is very computationally efficient (averaging h per simulation with 64 parallel processors) while still achieving reasonable agreement with available experimental data from Rafeie et al.20 (e.g., 0%–10% discrepancy). This was made possible because a relatively large mesh size (of ) is suitable for capturing the particle-laden flow in the proposed arbitrary Lagrangian–Eulerian approach, as compared to the very fine mesh (about ) needed for the standard LBM or NS approaches. This enables a ∼1000-fold computational time savings over these methods. This low computational cost could be put to great use in future studies that optimize the geometry of microchannels for a wide range of biotechnology applications.

In terms of the specific simulations, the conveying fluid flow was simulated and visualized first to investigate the velocity profile of the main flow and the secondary Dean flow for Reynolds numbers. Next, the particle movements due to inertial, impact forces, and Dean flow were simulated to investigate their equilibrium positions in two cross-sectional geometries of spiral microchannels. The simulations were conducted for (1) water with rigid particles (e.g., mimicking polystyrene) and (2) a fluid similar to plasma containing deformable particles (e.g., mimicking CTCs and RBCs).

The findings of this study indicated that for water and polystyrene beads, at flow rates between and , the equilibrium positions agreed very well with those observed experimentally by Rafeie et al.20 The shifting of particles toward the outer wall occurred at a flow rate of 20% higher than what was reported by Rafeie et al. for higher flow rates. Although the agreement between the experimental and simulation results is remarkable, the discrepancy at higher flow rates is likely due to rounding errors and/or imprecise input coefficients.

For the plasma-like simulations with particles similar to CTCs, it was found that particles migrate toward the inner wall and also the outer wall at higher flow rates. In contrast, the settling of the polystyrene beads occurs at lower flow rates. These discrepancies are likely due to two reasons. First, since plasma's viscosity is 1.8-fold of that of water, the Re for each flow rate is about half of what was considered by Rafeie et al.,20 leading to a reduction of the Dean flow (and the associated focusing forces). Second, as mentioned earlier, in contrast to rigid particles investigated by Rafeie et al., the cells are deformable, so this might cause a delay in their migration to the predicted positions. Since there were no experimental findings available for this case, it is suggested that for further confirmation of this study's findings, such experimental investigations should be done in future work. Additionally, the electrical double layer, van der Waals, and cohesion forces were not considered in this study, so future work is needed to investigate the influence of these within a more realistic plasma carrier fluid. Overall, this study confirms that this technique is very promising as a computationally efficient means to gain fundamental insights into particle/cell separation in inertial microfluidic devices.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by access to computational resources on the Australian NCI National Facility, Raijin, through the National Computational Merit Allocation Scheme. Also, we would like to thank UNSW's high performance computing service. In addition, we would like to acknowledge Dr. Mehdi Rafeie for his help via discussions about the technology, providing data for validation, and for permission to reprint figures and results from his publication with the permission of AIP publishing LLC.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rafeie M., Zhang J., Asadnia M., Li W., and Warkiani M. E., Lab Chip 16(15), 2791–2802 (2016). 10.1039/C6LC00713A [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Catarino S. O., Rodrigues R. O., Pinho D., Miranda J. M., Minas G., and Lima R., Micromachines 10(9), 593 (2019). 10.3390/mi10090593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Syed M. S., Rafeie M., Vandamme D., Asadnia M., Henderson R., Taylor R. A., and Warkiani M. E., Bioresour. Technol. 252, 91–99 (2018). 10.1016/j.biortech.2017.12.065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Voronin D. V., Kozlova A. A., Verkhovskii R. A., Ermakov A. V., Makarkin M. A., Inozemtseva O. A., and Bratashov D. N., Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21(7), 2323 (2020). 10.3390/ijms21072323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dalili A., Samiei E., and Hoorfar M., Analyst 144(1), 87–113 (2019). 10.1039/C8AN01061G [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liang W., Liu J., Yang X., Zhang Q., Yang W., Zhang H., and Liu L., Microfluid. Nanofluid. 24(4), 1–19 (2020). 10.1007/s10404-020-2331-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karimi A., Yazdi S., and Ardekani A., Biomicrofluidics 7(2), 021501 (2013). 10.1063/1.4799787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matas J.-P., Morris J. F., and Guazzelli É., J. Fluid Mech. 515, 171–195 (2004). 10.1017/S0022112004000254 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Di Carlo D., Irimia D., Tompkins R. G., and Toner M., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104(48), 18892–18897 (2007). 10.1073/pnas.0704958104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuntaegowdanahalli S. S., Bhagat A. A. S., Kumar G., and Papautsky I., Lab Chip 9(20), 2973–2980 (2009). 10.1039/b908271a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seo J., Lean M. H., and Kole A., Appl. Phys. Lett. 91(3), 033901 (2007). 10.1063/1.2756272 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haddadi H., Naghsh-Nilchi H., and Di Carlo D., Biomicrofluidics 12(1), 014112 (2018). 10.1063/1.5009037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jiang M., Li J., and Liu Z., arXiv:2002.08855v1 (2020).

- 14.Chen S., Liu Z., Shi B., He Z., and Zheng C., Acta Mech. Sin. 21(6), 574–581 (2005). 10.1007/s10409-005-0070-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jiang D., Tang W., Xiang N., and Ni Z., RSC Adv. 6(62), 57647–57657 (2016). 10.1039/C6RA08374A [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ma J.-T., Xu Y.-Q., and Tang X.-Y., Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2016, 28–35 (2016). 10.1155/2016/2564584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tan J., Ding Z., Hood M., and Li W., Biomicrofluidics 13(6), 064105 (2019). 10.1063/1.5129787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bazaz S. R., Mashhadian A., Ehsani A., Saha S. C., Krüger T., and Warkiani M. E., Lab Chip 20(6), 1023–1048 (2020). 10.1039/C9LC01022J [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dai Y., Li P., Li L., Luo J., and Huang C., paper presented at the 2016 IEEE International Nanoelectronics Conference (INEC), Chengdu, China, 9–11 May 2016.

- 20.Rafeie M., Hosseinzadeh S., Taylor R. A., and Warkiani M. E., Biomicrofluidics 13(3), 034117 (2019). 10.1063/1.5109004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crowe C. T., Schwarzkopf J. D., Sommerfeld M., and Tsuji Y., Multiphase Flows with Droplets and Particles (CRC Press, 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fox R. W., McDonald A. T., and Mitchell J. W., Fox and McDonald's Introduction to Fluid Mechanics (John Wiley & Sons, 2020). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Di Felice R., Int. J. Multiphase Flow 20(1), 153–159 (1994). 10.1016/0301-9322(94)90011-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clift R. and Gauvin W., Can. J. Chem. Eng. 49(4), 439–448 (1971). 10.1002/cjce.5450490403 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hölzer A. and Sommerfeld M., Powder Technol. 184(3), 361–365 (2008). 10.1016/j.powtec.2007.08.021 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mei R., Int. J. Multiphase Flow 18(1), 145–147 (1992). 10.1016/0301-9322(92)90012-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Michaelides E. E. and Roig A., AIChE J. 57(11), 2997–3002 (2011). 10.1002/aic.12498 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pan Y., Tanaka T., and Tsuji Y., Int. J. Multiphase Flow 28(4), 527–552 (2002). 10.1016/S0301-9322(01)00084-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cundall P. A. and Strack O. D., Geotechnique 29(1), 47–65 (1979). 10.1680/geot.1979.29.1.47 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johnson K., Contact Mechanics (Cambridge University Press, 1985), pp. 84–106. 10.1017/CBO9781139171731 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tsuji Y., Tanaka T., and Ishida T., Powder Technol. 71(3), 239–250 (1992). 10.1016/0032-5910(92)88030-L [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lara O., Tong X., Zborowski M., and Chalmers J. J., Exp. Hematol. 32(10), 891–904 (2004). 10.1016/j.exphem.2004.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schrader D., The Wiley Database of Polymer Properties (John Wiley & Sons, 2003). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu Z., Lee Y., hee Jang J., Li Y., Han X., Yokoi K., Ferrari M., Zhou L., and Qin L., Sci. Rep. 5, 14272 (2015). 10.1038/srep14272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hu S., Wang R., Tsang C. M., Tsao S. W., Sun D., and Lam R. H., RSC Adv. 8(2), 1030–1038 (2018). 10.1039/C7RA10750A [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li M., Liu L., Xi N., Wang Y., Dong Z., Xiao X., and Zhang W., Sci. China Life Sci. 55(11), 968–973 (2012). 10.1007/s11427-012-4399-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hayase T., Shirai A., Sugiyama H., and Hamaya T., Trans. Jpn. Soc. Mech. Eng. 68(676), 3386–3391 (2002). 10.1299/kikaib.68.3386 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Norouzi N., Bhakta H. C., and Grover W. H., PLoS One 12(7), e0180520 (2017). 10.1371/journal.pone.0180520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Segre G. and Silberberg A., Nature 189(4760), 209–210 (1961). 10.1038/189209a0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moloudi R., Oh S., Yang C., Warkiani M. E., and Naing M. W., Microfluid. Nanofluid. 22(3), 33 (2018). 10.1007/s10404-018-2045-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Warkiani M. E., Guan G., Luan K. B., Lee W. C., Bhagat A. A. S., Chaudhuri P. K., Tan D. S.-W., Lim W. T., Lee S. C., and Chen P. C., Lab Chip 14(1), 128–137 (2014). 10.1039/C3LC50617G [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.