Abstract

Purpose

Fertility is an important issue among adolescent and young adult female (AYA-F) cancer survivors. This study examined AYA-F survivors’ unmet needs and recommendations for care to address fertility/family-building in post-treatment survivorship.

Methods

Semi-structured interviews (45–60 minutes) explored themes related to fertility and family-building after cancer. Coding categories were derived based on grounded theory methods. Themes were identified through an iterative process of coding and review.

Results

Participants (N=25) averaged 29 years old (SD=6.2; range, 15–39), were primarily White and well educated, and averaged 5.81 years post-treatment (SD=5.43); 32% had undergone fertility preservation (pre- or post-cancer). Six recommendations for improving care were identified: addressing patient-provider communication, need to provide informational, emotional, and peer support, financial information, and decision-making support. AYA-Fs believed the best way to learn about resources was through online platforms or doctor-initiated discussions. Telehealth options and digital resources were generally considered acceptable. Face-to-face interactions were preferred for in-depth information, when AYA-Fs anticipated having immediate questions or distressing emotions, and with concerns about Internet security. Thus, a combined approach was preferred such that information (via web-based communication) should be provided first, with follow-up in-person visits and referral when needed.

Conclusion

Informational and support services are needed to better educate patients about gonadotoxic effects and options to have children after cancer treatment is completed. Future work should evaluate how to best support oncology providers in meeting the needs of survivors concerned about fertility and family-building including referral to clinical specialties and supportive resources.

Keywords: young adult cancer, adolescent cancer, cancer survivorship, oncofertility, reproductive health

Adolescent and young adult female (AYA-F) cancer survivors are at increased risk of gonadal dysfunction depending on the type and extent of treatment [1], and fertility is an important survivorship issue [2]. Fertility counseling is a core component of care for reproductive aged patients [3, 4] and clinical guidelines highlight the need to follow-up post-treatment [5, 6]. AYA-Fs report multiple needs for oncofertility counseling after cancer [7, 8]. A better understanding of AYA-Fs’ preferences for oncofertility care in post-treatment survivorship is important to building patient-centered services.

For AYA-Fs that experience fertility problems after cancer, family-building options may include assistive reproductive technology (ART) and surrogacy (with fresh/frozen/donated gametes), or adoption or fostering. The majority of AYA-Fs are uncertain of their fertility post-treatment and receive limited reproductive health care, and fertility distress is associated with lower quality of life [9, 10]. Many have questions about reproductive potential, health risks, and family-building options if natural conception is not feasible or is not desired [11]. Most AYA-Fs do not undergo fertility preservation before treatment and, among those who do, there is a limited awareness of the challenges involved in using frozen eggs/embryos later in life (e.g., high costs, low rates of success) [12–14]. There are also emotional, financial, legal, and logistical considerations for surrogacy, using donor gametes, and adoption or fostering [15]. Likewise, individual- and institution-level factors affect providers’ likelihood of addressing fertility with patients including lack of knowledge, diffusion of responsibility, and lack of referral options [16]. Survivors should be educated about their options and connected to resources as needed [17, 18].

We previously found high rates of worry and decision-making uncertainty among AYA-F survivors prompted to consider fertility and family-building [19]. We proposed a model of how AYA-Fs make decisions about family-building after cancer including areas of uncertainty, cognitions and emotions, and coping behaviors [20]. Building on this work, this study aimed to explore survivors’ recommendations for addressing their fertility and family-building needs after cancer.

Methods

This study was part of a larger study examining AYA-Fs’ fertility and family-building experiences after cancer [20]. Study procedures were approved by the Northwell Health Institutional Review Board.

Participants

Eligibility criteria included: 1) female, 2) aged 15–39 years old, 3) cancer history (at least one diagnosis of malignancy) and completion of gonadotoxic treatment (e.g., systemic chemotherapy and/or pelvic radiation), 4) had not had a child since cancer diagnosis, and 5) reported parenthood desires or undecided family-building plans. AYA-Fs could have been on long-term adjuvant or endocrine treatment or currently pregnant (or a surrogate was pregnant).

Procedure

Purposeful sampling aimed to recruit participants across the AYA age range. Hospital-based recruitment identified patients through electronic medical records and introductory letters were mailed. Study advertisements were also posted on patient organizations’ social media pages (e.g., Stupid Cancer, Lacuna Loft) with a link to provide contact information using a HIPPA-compliant platform. Follow-up calls confirmed eligibility and completed informed consent and enrollment. Parental consent and participant assent were obtained for minors.

Qualitative interviews (45–60 minutes) were conducted over the phone following a standardized, semi-structured interview guide (Supplementary Table 1). Interviewees (CB and ALH) were trained in qualitative research methodology and had expertise in young adult cancer survivorship and oncofertility. Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim by a professional transcription service, and kept confidential. Participants received $20 for completing the interview.

Qualitative Analysis

Qualitative research guidelines were followed including the use of an audit trail, member checking among the coding team, triangulation of researchers, and data saturation [21]. All transcripts were read at least twice, and inter-rater reliability was established for all codes (>0.70; Dedoose platform). For the data reported here, grounded theory coding was utilized, which is an exploratory approach that allows unexpected but salient themes to emerge from the data [21]. Coding was completed in dyads (ALH, AM, and JN), reviewed by a third coder (CB), and discussed weekly in team meetings. First, open coding was conducted to establish an initial code set. Sampling was completed once data saturation was reached. A code book was created through iterative independent and collaborative analysis. Codes were defined and evaluated through interpretation of participant quotes. All transcripts were read another time to confirm coded data and to categorize the coded data based on themes and conceptual similarities. Agreement was reached among coding team members to ensure themes/subthemes accurately represented the data.

Results

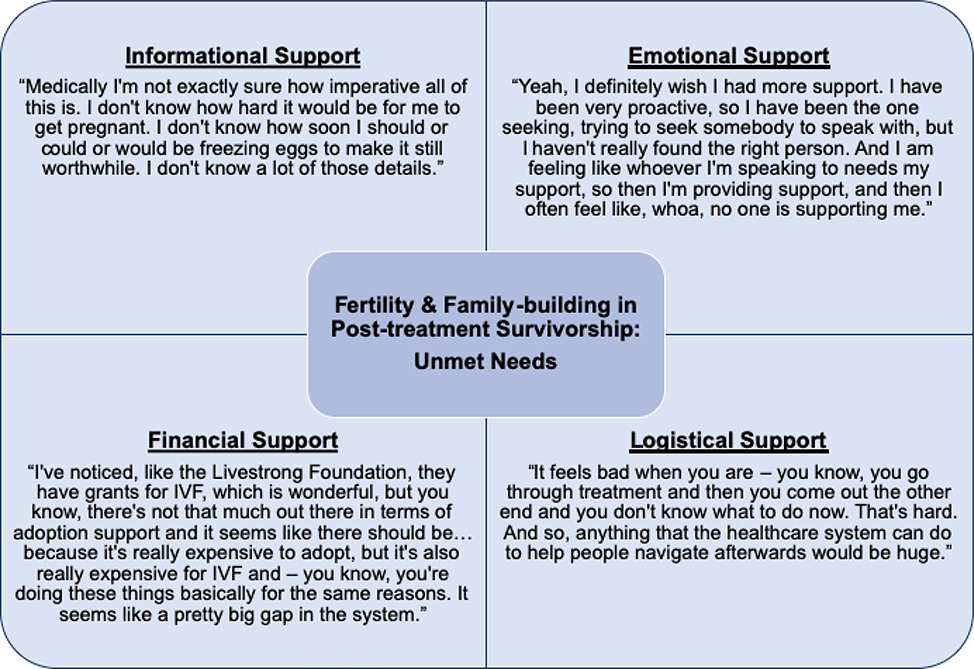

Table 1 reports sociodemographic and medical characteristics. Participants (N=25) averaged 29 years old (SD=6.2; range, 15–39) and 32% had undergone fertility preservation prior to treatment. For context, multiple challenges were discussed including lack of information about fertility and family-building, and unmet needs for emotional support, information about costs, and navigating healthcare systems (Figure 1). AYA-Fs felt lost about how to access information and services. They wondered if their worries and fears were justified, questioned whether to access medical care and, if so, how. They were particularly unsure about a recommended timeline of when to pursue a fertility evaluation. Many worried about missing their window of reproductive opportunity, fearing early menopause. Fertility worries became more salient and relevant after treatment was completed and they had “survived” their cancer. Themes related to uncertainty, cognitions, emotions, and coping behaviors were previously reported [20].

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and Medical Characteristics.

| Sociodemographic and medical characteristics (N=25) | |||

| M (SD) | Median | Range | |

| Current age (years) | 29.44 (6.20) | 28.00 | 15 – 39 |

| Age at cancer diagnosis (years) ± | 22.68 (8.46) | 22.00 | 9 – 38 |

| Age finished most recent treatment (years) ± | 23.92 (8.12) | 21.50 | 10 – 38 |

| Time since most recent treatment (years)1 | 5.81 (5.43) | 2.00 | 0.5 – 16 |

| Diagnosed in childhood (<15 years old), n=4 | |||

| n | % | ||

| Diagnosis (first cancer) | |||

| Hodgkin Lymphoma | 6 | 24.0 | |

| Breast | 5 | 20.0 | |

| Gynecological cancers (Ovarian, Cervical, Uterine) | 4 | 16.0 | |

| Leukemia | 3 | 12.0 | |

| Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma | 1 | 4.0 | |

| Anal, rectal, colon, colorectal | 1 | 4.0 | |

| Sarcoma | 1 | 4.0 | |

| Myelodysplastic Syndrome | |||

| Recurrence(s) or secondary primary cancer | 3 | 12.0 | |

| Race± | |||

| White | 20 | 80.0 | |

| More than one race | 2 | 8.0 | |

| Other | 2 | 8.0 | |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic | 21 | 84.0 | |

| Hispanic | 4 | 16.0 | |

| Relationship status | |||

| Married/partnered | 17 | 68.0 | |

| Geographic locality | |||

| Suburban | 19 | 76.0 | |

| Urban | 4 | 16.0 | |

| Rural | 2 | 8.0 | |

| Annual income (household total) | |||

| Less than $50,000 | 9 | 36.0 | |

| $50,000 – $100, 000 | 9 | 36.0 | |

| More than $100,000 | 5 | 20.0 | |

| Prefer not to answer | 2 | 8.0 | |

| Education | |||

| College Degree | 12 | 48.0 | |

| Post-Graduate Degree | 7 | 28.0 | |

| High school degree/ Vocational training | 5 | 20.0 | |

| Some high school, no degree | 1 | 4.0 | |

| Employed, full- or part-time | 22 | 88.0 | |

| Family-building characteristics | N | % | |

| Took steps to preserve fertility before treatment2 | 8 | 32.0 | |

| Lupron Injection | 4 | 16.0 | |

| Froze eggs | 2 | 8.0 | |

| Frozen embryos | 2 | 8.0 | |

| Frozen Ovarian Tissue | 1 | 4.0 | |

Variable includes missing data; not included in SD and median calculations

Excluding hormone therapy (e.g., tamoxifen for breast cancer survivors) and long-term targeted therapy(e.g., Gleevec or Herceptin).

Categories not mutually exclusive.

Figure 1. Patient-reported Unmet Needs for Fertility Care and Family-building in Post-treatment Survivorship.

Participants discussed multiple challenges related to fertility and family-building after cancer including lack of information and unmet needs for emotional support, information about costs, and navigating healthcare systems

Recommendations for Providing Support

When asked how to improve post-treatment care around fertility and family-building, AYA-Fs provided suggestions based on their experiences. Six primary recommendations were identified (Table 2).

Table 2.

Patient-driven Recommendations for Improving Follow-up Fertility Counseling Post-treatment.

| Patient Recommendations | Sample Quotes |

|---|---|

|

1. Provide Informational

Support | |

| - Provide more information post-treatment about reproductive health, options for evaluating fertility, and options for family- building | “For starters, don’t assume that we know anything, because for the most part, we walk in knowing very little. We probably know how our ovaries work, generally speaking, and why we get a period every month. … And we’re walking in scared, so combine those two things, and just assume that there’s – start at the beginning, start at the stupid level, because talking above our heads is (a) just gonna confuse us, and (b) you’re just gonna have to go back and explain it all over again, twice.” |

|

2. Offer Emotional Support | |

| - Provide resources to support emotional

difficulties including distress and confusion - Mental health counseling is helpful to address fertility distress and decision-making uncertainty |

“…to have somebody available

after your [fertility] consultation with your doctor to talk about just

your feelings that you’re having that moment that have a sort of

specialty in the fertility loss because it is a loss. … and

they’d be able to give you information to say if you’re

not prepared talk about this right now here’s my number.

We’ll contact you; you can contact us in a few days or a week or

whatever. to have access to that even if the talk is about making the

decision and what you should do.” “I think the medical stuff is easier in a lot of ways, like, oh, okay, you want to start a family, here is a pamphlet on how to start a family. But being emotionally there and ready to make that decision has been a way harder struggle for me. So, I think having either medical providers or psychological providers that are kind of involved in that process and kind of letting you know. that would be helpful to me.” |

|

3. Provide Guidance for “Next Steps” | |

| - Give survivors a “roadmap” for options and decision points | “I think that especially for young

adults, like have something for me when I’m done with treatment,

some kind of guidance for me on what I should or shouldn’t be

doing relating to fertility afterwards.” “What kind of tests, what kind of scans, what you should I be looking for. Maybe if there’s even a list of physicians that are specialist…because for me that’s the most difficult part, where do I start and what do I even have to be looking for? How do I know that the fertility specialist that I choose is going to know what I need? How do I know that I’m getting the correct tests, the correct scans that should be looking for what could be an issue for me?” |

| - Guidance was needed for accessing care and to self- advocate for information and referral | “Like ten questions that you should ask about your fertility to your doctor before seeking treatment, and then - or like ten questions after you’ve completed treatment, stuff like that. Like there’s a guide, I guess, so you’re asking the right questions and you’re not going to be brushed off would be a good way of putting it.” |

| - Professional counseling may help facilitate decision-making processes | “My fertility clinic has in-house

psychiatrists and counseling… and I started to go to those

counseling sessions, because it helped me understand cancer and

infertility, and what was the best option for me. And I think that was

probably the best - our counseling, individual, private counseling is

what helped me decide what was the best option.” “So if I’m trying to decide on whether I should try and preserve my fertility or if I’m trying to decide whether I should adopt or foster or whatever, maybe somebody can ask me those types of questions that would get me to think about these things in a different light that would get me to evaluate whether this is a good decision for me, and kind of keep track with me about what these pros and cons are.” “I feel like talking to someone in real time that could give you answers right away and see where you’re at or where you’d like to be would be helpful instead of falling down into a black hole of internet research and not really getting anywhere.” “… if I’m trying to decide whether I should adopt or foster or whatever, maybe somebody can ask me those types of questions that would get me to think about these things in a different light that would get me to evaluate whether this is a good decision for me, and kind of keep track with me about what these pros and cons are.” |

|

4. Improve Communication | |

| - Initiate honest, open dialogues that can

continue over time - Have developmental appropriate conversations with minors |

“I would tell them that they should

ask young women about what their thoughts are on having a child or not.

Like, none of my doctors brought anything up about do I want to have a

kid in the future. After I finished treatment and stuff, I just started

looking into it myself. So maybe if they brought it up when I was like

21 or 22, maybe I would have had a better chance of being able to freeze

my eggs instead of now, 28 might have been too late. So maybe if they

started asking me what I want to do about the future. There’s a

possibility of infertility with your case and stuff. So yeah, I think

they should start talking about it early.” “I think that specifically pediatric oncologists who are dealing with girls who are going through puberty or have just recently gone through puberty, I think it’s extremely important for the issue to be brought up… when you’re so young you can’t really advocate for yourself as well, and especially if you don’t have parents who are advocating for you, so [providers] need to be the ones that are bringing this up.” |

| - Spend more time discussing fertility and family-building topics during clinic visits | “I wish doctors would take more time with the patient, and clearly discuss their options, and what is life after cancer, what does that look like for them.” |

| - Communicate with more empathy - Be inclusive of gender identity and sexual orientation |

“I think there’s a level of - I

don’t want to call it ‘lack of compassion’ because

that sounds too strong - but the doctor, it’s their job, and they

do it every day… And so, I think over time, the impact is less

for them, whereas, for us, the impact is very big, and it’s very

personal, because we only experience this once. This is the first time

we experience it. And so, I think it’s important to realize that

a hug or a touch on the shoulder, or a smile, little things like that,

that make it more personal are very helpful, and go a really long way in

letting us know that the doctor cares.” “I would hope that as time goes by that, you know, the language used in [resources] is inclusive of all life experiences, including LGBTQ people. I think sometimes it’s very, like, okay, so you’re a woman and you’re going to get pregnant, you know, with your husband, and there is this kind of expectation of the heterosexual couple. So, I would just say, I would hope that the language and the intent is a little bit more inclusive than that.” |

|

5. Provide Financial Information | |

| - Connect patients to information about the

cost of family-building options - Information about potential financial support resources to help cover the costs of family- building, such as grants and loans, is also needed |

“I would say work on the financial end

of it, because that’s incredibly important and stressful. That

was actually way more stressful than any other part of cancer was,

‘How am I going to pay for fertility treatments’ and

‘Am I ever going to have kids?…that stuff is not covered

by insurance generally, so that’s very stressful. So having

somebody explain the finances was very helpful. … if you can come

up with a financial plan to help people that would be great

too.” “I’m sure there’s money grants and stuff out there for stuff like this but how do I get a hold of that information besides Google.” “Yeah, I don’t think I’ve ever thought about actually bringing that up in particular with a financial advisor but I think if and when I’m ready to pursue [family-building] that would be something that I would have to do in order to figure out how to pay all of this.” |

|

6. Refer to Peer Support Resources | |

| - Oncology providers should refer patients to relevant peer support resources and patient organizations | “I think once a young woman who is done with treatment and stuff, I think the oncologist should be able to help her find support groups and stuff if she would be interested in talking about infertility and stuff, so she has the option out there to talk with other people if she doesn’t have a good support system.” |

| - Connecting with peers helps normalize feelings | “I think one of the main things - it happens a lot with some of these weird cancer feelings - I think having the ability to know that those feelings are really normal. It’s happened several times where I’m like, oh my gosh, this thought just seems absolutely crazy, why am I thinking this, and then you go online, or you reach out to a cancer survivor and you realize that those thoughts are really normal.” |

| - Peers can provide guidance about family-building options and the process involved | “How is it gonna be for us through

the whole process, trying to conceive the child… stories of

success or no success in order to know which route to go on, like if

it’s gonna be the route to adopt, the route to in vitro,

surrogate, and things like that. Stories that we can identify our future

selves with.” “So, you know, if there was support groups for mothers of adopted children or - and they were willing to talk to those considering adoption, that kind of thing. Like, if there was a - or even like a chat or something like that, where you can get connected with people who have already used these family planning options.” |

| - There may also be a burden to peer support group participation; e.g., worrying about others’ reactions | “I had a very difficult time talking about my personal problems with surrogacy and infertility in my cancer support group, because I felt like I was causing more harm to other people by talking about this option that I had, where some of them wished they would have had that option. That’s why I only talk about it in my infertility group, because it’s a little bit easier atmosphere, and even though it’s better for me to talk about in cancer group, I notice a lot of people are very upset, and I didn’t want to hurt them more.” |

1. Provide Informational Support

Most AYA-Fs wanted providers to offer more information about fertility/family-building, irrespective of pre-treatment counseling and post-treatment fertility status (80%). It was important to provide background reproductive health information, as many felt uninformed about basic fertility topics. As one survivor stated, “Don’t assume we know anything… start at the beginning, start at the stupid level.” Among those with more knowledge and/or in the case of obvious reproductive limitations (e.g., posthysterectomy), there was uncertainty about alternative parenthood options. Survivors were careful to explain that providers should not make assumptions about patients’ family-building desires or intentions and should provide information about all options, without encouraging or discouraging one over another. The importance of provider-initiated informational exchange was highlighted among minors, as they saw their young age as an impediment to accessing information and wished to be a part of these discussions. For all ages, information was perceived as a first step, such that providers should present the topic and avail themselves as questions arose. AYA-Fs recognized that they may need additional resources and care once they were better informed and hoped providers would be able to provide referrals.

2. Offer Emotional Support

For many, addressing the emotional context surrounding fertility was considered necessary (64%). Providing information alone was not seen as adequate. As one survivor stated, “The science part is helpful, but really it’s the emotional aspects.” AYA-Fs wished providers better recognized the emotional aftermath of receiving unexpected or upsetting news and provided guidance about accessing support resources. One survivor emphasized the importance of addressing emotional support needs post-treatment as support networks often fall away; “people will support you in cancer, but they can’t support you in [pursuing motherhood] that’s also my dream in life.” Counseling to help with uncertainty and distress was highlighted. A few survivors had previously or were currently participating in psychotherapy and described its benefit; others imagined that such support would be helpful in the future. Having access to emotional support outlets was emphasized by those closer in age or readiness for parenthood and by those more informed about potential challenges.

3. Provide Guidance for "Next Steps"

Survivors described an overarching need for guidance about how to translate information into actionable next steps (64%). AYA -Fs described wanting “step-by-step instructions” based on their family-building goals and/or someone who could “walk them through the process”; e.g., “some kind of guidance on what I should or shouldn’t be doing relating to fertility afterwards.” Several AYA-Fs imagined that a mental health professional would be valuable in helping them understand their options for next steps and decision-making, personalized to their goals and medical situation. One participant stated, “get me to evaluate whether this is a good decision for me.” Guidance was also needed to facilitate discussions with providers. Several survivors wished for help to guide their efforts interacting with care teams and health systems. As part of family-building decision-making, many faced a multistep process of accessing reproductive medical care, which would then inform next steps and there was uncertainty about what would come and how to access care. As one survivor stated, “It feels bad when you go through treatment and then you come out the other end and you don’t know what to do. Thaťs hard. …anything that the healthcare system can do to help people navigate afterwards would be huge.”

4. Improve Communication

Communication was cited as an important aspect of oncofertility care (discussed by 40%). Three main points were discussed: AYA-Fs wished providers communicated with more empathy; initiated honest, open dialogues that could continue over time; and spent more time discussing fertility and family-building during clinic visits. Lack of fertility/family-building discussions was perceived as lacking empathy around the importance of these topics and failure to treat the “whole person.” They wanted conversations to be initiated by providers and felt providers should regularly check-in to assess their readiness for information, which should be done with sensitivity to accompanying emotions (e.g., anxiety, fear). AYA-Fs wanted providers to guide decisions about if and when a fertility risk/problem should be addressed. That is, they wanted reassurance that they could rely on providers to prompt action if needed. Thus, a balanced approach of giving AYA-Fs control over discussions, while providing a safety-net that critical issues would not be missed, was desired.

Notably, the need to be inclusive with language and resources was highlighted by some participants, so as not to marginalize sexual and gender minorities. One survivor discussed the hetero-normative assumptions that many providers approach discussions with and voiced her hope that this would change to have greater recognition and acceptance of all gender and sexual identities and lifestyle choices.

5. Provide Financial Information

A subgroup of survivors was aware of the high costs associated with alternative family-building options and wanted more financial information (40%) and/or expressed a need for monetary support to help with costs (16%). Costs were described as “scary” and family-building decisions were considered “serious financial decisions”; while searching for financial resources was “overwhelming.” Among those with awareness of high costs, the desire for individualized, face-to-face financial counseling was reported. Information about financial assistance programs was seen as an important resource to include in AYA cancer informational packets. Being provided financial information “upfront” was described as important by multiple participants to allow time for financial planning, recognizing that “it takes a while to save money.” One survivor mentioned that she knew of several grants to support fertility preservation costs but was unaware of any for IVF or adoption and wished she had help to search for such resources. Some AYA-Fs thought that financial planning advice from a specialized financial counselor would be helpful. Two survivors mentioned receiving financial counseling to pay off medical bills and for retirement planning and wondered how to access a similar service for family-building financial planning.

6. Refer to Peer Support Resources

Some AYA-Fs discussed a desire for greater access to peer support related to fertility/family-building specifically (36%). Cancer care teams were seen as an easy and appropriate channel to learn of peer support outlets. AYA-Fs were connected with cancer and infertility organizations through online and social media outlets. These outlets served two key functions. First, peer support was an important part of normalizing experiences and reducing isolation; e.g., “knowing that those feelings are really normal.” Peer connections filled a critical need, even when survivors had strong support networks of family and friends. One survivor described her husband as loving and adoring, yet still felt “essentially alone” as she struggled with frustrations that they were unable to “have a child like someone normal.” Another described the pressure to be positive with family/friends, whereas with peers she could be “as negative as I want to be.” Second, hearing others’ experiences served as an example for how the future might look; “stories to identify our future selves with.” This type of experiential information was seen as useful in guiding decisions and provided hope that family-building pursuits would be successful. One survivor feared discrimination in the adoption process and was comforted by other survivors’ stories of successful adoption. Some AYAs felt empowered by being support providers and “giving back.”

Preferences for Delivery of Services

The need for post-treatment resources related to fertility/family-building was contextualized within a broader need for age-specific AYA cancer resources. An AYA cancer program, physically located in the hospital and/or existing within a virtual platform (e.g., “clearinghouse for information online”), was seen as an obvious way to have easy access to relevant information. This was separate from, and in addition to, the desire for provider-initiated discussions during clinic visits. Survivors discussed ideas for useful resources they would want within a centralized program including access to up-to-date medical information and an online database of relevant specialty care services (e.g., reproductive endocrinology, psychology/psychiatry).

Format: Face-to-face vs. Digital Platforms

Most AYA-Fs believed the best way to initially learn about fertility/family-building topics and resources was through online platforms (72%) and/or doctor-initiated discussions (40%). Following initial introduction of the topic, face-to-face interactions was preferred for in-depth, individualized medical information and counseling. A preference for face-to-face communication was also preferred when fertility was deemed a highly emotional topic, when it was perceived as a complicated situation and AYA-Fs anticipated having immediate questions, and when there were concerns about Internet security. Survivors noted the downside of delivering information face-to-face given the infrequency of visits in survivorship, requiring long wait periods. Digital platforms were considered an acceptable and more time-sensitive means for accessing initial information. Thus, a combined approach was preferred such that general information (via digital communication) about fertility-related topics should be provided first, with options for follow-up in-person visits for individualized care. Some survivors referenced telehealth options as acceptable, though scheduling visits was still seen as a barrier to timely information.

AYA-Fs wanted multiple points of access to information including online, face-to-face consultation, pamphlets (e.g., within discharge packets), and email or telehealth communication. In part, this was one way to ensure information was delivered and to safeguard against gaps in care. Multiple information modalities also allowed AYA-Fs greater control over access and timing. As one survivor described, having a fertility nurse navigator and written information provided options for her to decide when and in what way to address the topic; i.e., “when I was ready and on my terms.”

Timing

Although interviews focused on post-treatment oncofertility care, many AYA-Fs referenced the time period after diagnosis as a critical juncture for information (48%). Equally, AYA-Fs discussed the importance of follow-up fertility counseling early in post-treatment survivorship (52%). Ideally, conversations started at diagnosis would continue into survivorship with greater detail and referrals based on patients’ evolving needs. As one survivor recommended: “So having that continued conversation as they go through their treatment and then beyond, post cancer – continuing to inform them about their options as they get closer to wanting to have a family, that discussion can dive a bit deeper.” One woman spoke of regret that her provider had not brought up family-building after she was done with treatment, perceiving this as a missed opportunity to better her chances for having a biologically related child. Another participant clarified that conversations in survivorship care were important “even if someone froze eggs” prior to treatment.

A few participants discussed wanting resources prior to visits to enable more meaningful clinical discussions. One survivor wanted to be more informed to better evaluate her provider’s recommendations and determine her need to advocate for additional or alternative care options. Others described wanting resources after meeting with a provider to review information and refer back to.

Discussion

This study explored AYA-F cancer survivors’ recommendations for addressing fertility and family-building topics in post-treatment survivorship care. Six recommendations were identified including the types of support patients desired and ways to improve provider communication. Additional recommendations referred to the format and timing for delivering services. Survivors wished their care teams would regularly check-in about oncofertility issues with emotional sensitivity. Provider-initiated discussions relieved patients from the burden of bringing up concerns themselves and worry about missing critical information or reproductive time windows. Both in-person discussions and digital resources were considered important. Having multiple options for accessing informational and supportive care allowed flexibility for survivors to have control over when and in what way they could engage this aspect of their care.

Findings highlighted the importance of addressing fertility and family-building across the continuum of cancer care. In a recent study, 62% of AYA-F survivors with severely reduced ovarian reserve after cancer treatment pursued fertility preservation post-treatment when offered [22]. Discussions may also prompt counseling about other important and actionable sexual and reproductive health topics such as contraception, safe sexual practices, and gynecologic care [23]. Ongoing check-ins help to identify patients’ evolving needs, while reassuring patients that providers may be a first-stop resource when questions arise.

Findings add to the literature by delineating patient preferences for support post-treatment to plan for long-term parenthood goals, which may involve adjusting to reproductive limitations. In some ways, recommendations paralleled pre-treatment fertility counseling needs including the need for basic education about reproductive health and family-building options if natural conception is not possible or desired, information about costs, and peer support [24]. Patient needs after treatment, however, also differ from the time of diagnosis in which counseling typically focuses on fertility preservation decisions, and patients are overwhelmed by impending treatment. Other topics become more salient as patients complete treatment but face lasting gonadotoxic effects. Interestingly, only 40% of participants worried about the financial burden of family-building options, possibly due to lack of knowledge about costs. Prior work has demonstrated significant financial stress among AYAs pursuing IVF, surrogacy, and adoption [25], suggesting the potential benefit of early financial planning. Reducing isolation and providing peer support opportunities were also top priorities, along with the need for practical knowledge, skills, and support for navigating healthcare systems, similar to AYA survivorship needs more broadly [26].

Technology-based resources are deemed acceptable and convenient by AYAs when designed for their age group [27]. Utilizing digital platforms, patient resources should be readily available early in patients’ cancer journey with reminders about where and how to access them. Resources may then be easily accessed and distributed, making it convenient for patients and helpful to providers to facilitate ongoing discussions.

Notably, strategies are needed to support providers in addressing oncofertility issues and establish institution-wide systems of care. Improving care may include: providing education to providers and automatic reminders; availability of patient resources, which providers may refer patients to; establishing a referral network for needed services such as reproductive endocrinologists and mental health providers; and promoting a multidisciplinary approach to oncofertility care [28]. Guidelines for creating oncofertility services exist [29, 30], as well as training programs and scripts for providers [31–33]. Kelvin et al. reviewed organizational strategies for overcoming barriers to address fertility preservation in oncology settings [28], which may be expanded to address post-treatment topics. It may be ideal for one member of the care team to acquire oncofertility expertise (e.g., “fertility navigator”) [34]. The ECHO (Enriching Communication Skills for Health Professionals in Oncofertility) training program is designed for oncology allied health providers [35]. At minimum, providers should be familiar with oncofertility considerations (medical, psychosocial, ethical, and legal) to be prepared to introduce fertility/family-building topics and make referrals [29, 33, 36].

Lastly, provider communication and patient resources should be developmentally appropriate and inclusive of gender and sexual identities. Institutions with a dedicated AYA program should be intentional about “brand presence” to be welcoming for all patients and relevant for this age group [26]. Most institutions, however, will not have a centralized AYA program and providers may want to refer to AYA cancer organizations (e.g., Stupid Cancer, Lacuna Loft, Elephants and Tea, and Young Survival Coalition). AYA-Fs in this study desired peer support to normalize their experiences and for guidance. Integrating clinical care programs with AYA survivorship resources should be a priority [37].

Limitations

Participants were primarily White non-Hispanic AYA-Fs, with a greater proportion of young adults (18–39 years old) than adolescents (15–17 years old), and recruitment was largely through social media, which may limit generalizability [38]. Greater effort to engage diverse subgroups and employ methodology that leads to representative samples is needed. Longitudinal data was not collected, and AYA-Fs' support needs and recommendations may change over time.

Conclusion

Patients described six recommendations for improving cancer survivorship care with respect to posttreatment fertility and family-building. Future work should evaluate how to best support oncology providers and developing patient-centered supportive resources. Better communication that allows AYA-Fs to feel supported but also in control of information delivery, while connecting them with peer support outlets, particularly those delivered via digital platforms, may be important to improving care.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the support provided from our patient organization partners with recruitment efforts, including Stupid Cancer, Lacuna Loft, The Samfund, Alliance for Fertility Preservation, and Army of Women.

Funding: This research was supported by a grant from the National Cancer Institute (R03CA212924, PI: Catherine Benedict).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: Catherine Benedict is a member of the Stupid Cancer Board of Directors and a member of the Advisory Council for the Alliance for Fertility Preservation. These organizations assisted in recruitment efforts. There are no financial relationships to disclose. All co-authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Code availability: Not applicable.

Research Involving Human Subjects: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee (Northwell Health Institutional Review Board; Protocol #16–876) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Welfare of Animals: This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of a an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

References

- [1].van Dorp W, Haupt R, Anderson RA, et al. (2018) Reproductive function and outcomes in female survivors of childhood, adolescent, and young adult cancer: a review. J Clin Oncol 36:2169–2180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Logan S, Perz J, Ussher JM, et al. (2019) Systematic review of fertility-related psychological distress in cancer patients: Informing on an improved model of care. Psycho-Oncology 28:22–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Quinn GP, Block RG, Clayman ML, et al. (2015) If you did not document it, it did not happen: rates of documentation of discussion of infertility risk in adolescent and young adult oncology patients? medical records. J Oncol Pract 11:137–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Lewin J, Ma JMZ, Mitchell L, et al. (2017) The positive effect of a dedicated adolescent and young adult fertility program on the rates of documentation of therapy-associated infertility risk and fertility preservation options. Support Care Cancer 25:1915–1922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Oktay K, Harvey BE, Partridge AH, et al. (2018) Fertility preservation in patients with cancer: ASCO Clinical Practice Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol 36:1994–2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].van Dorp W, Mulder RL, Kremer LCM, et al. (2016) Recommendations for premature ovarian insufficiency surveillance for female survivors of childhood, adolescent, and young adult cancer: a report from the International Late Effects of Childhood Cancer Guideline Harmonization Group in collaboration with the PanCareSurFup Consortium. J Clin Oncol 34:3440–3450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Massarotti C, Scaruffi P, Lambertini M, et al. (2019) Beyond fertility preservation: role of the oncofertility unit in the reproductive and gynecological follow-up of young cancer patients. Hum Reprod 34:1462–1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Murphy D, Klosky JL, Reed DR, et al. (2015) The importance of assessing priorities of reproductive health concerns among adolescent and young adult patients with cancer. Cancer 121:2529–2536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Gorman JR, Su HI, Roberts SC, et al. (2015) Experiencing reproductive concerns as a female cancer survivor is associated with depression. Cancer 121:935–942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Benedict C, Thom B, Friedman DN, et al. (2018) Fertility information needs and concerns posttreatment contribute to lowered quality of life among young adult female cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer 26:2209–2215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Gorman JR, Su HI, Pierce JP, et al. (2014) A multidimensional scale to measure the reproductive concerns of young adult female cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv 8:218–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Goldman RH, Racowsky C, Farland LV, et al. (2017) Predicting the likelihood of live birth for elective oocyte cryopreservation: a counseling tool for physicians and patients. Hum Reprod 32:853–859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Luke B, Brown MB, Missmer SA, et al. (2016) Assisted reproductive technology use and outcomes among women with a history of cancer. Hum Reprod 31:183–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Doyle JO, Richter KS, Lim J, et al. (2016) Successful elective and medically indicated oocyte vitrification and warming for autologous in vitro fertilization, with predicted birth probabilities for fertility preservation according to number of cryopreserved oocytes and age at retrieval. Fertil Steril 105:459–466.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Rosen A (2005) Third-party reproduction and adoption in cancer patients. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 2005:91–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Covelli A, Facey M, Kennedy E, et al. (2019) Clinicians? perspectives on barriers to discussing infertility and fertility preservation with young women with cancer. JAMA Netw Open 2:e1914511–e1914511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Gorman JR, Whitcomb BW, Standridge D, et al. (2017) Adoption consideration and concerns among young adult female cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv 11:149–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Armuand GM, Wettergren L, Rodriguez-Wallberg KA, et al. (2014) Desire for children, difficulties achieving a pregnancy, and infertility distress 3 to 7 years after cancer diagnosis. Support Care Cancer 22:2805–2812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Benedict C, Thom B, N Friedman D, et al. (2016) Young adult female cancer survivors? unmet information needs and reproductive concerns contribute to decisional conflict regarding posttreatment fertility preservation. Cancer 122:2101–2109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Benedict C, Hahn AL, McCready A, et al. (2020) Toward a theoretical understanding of young female cancer survivors? decision-making about family-building post-treatment. Support Care Cancer. 10.1007/s00520-020-05307-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Saldana J (2012) The coding manual for qualitative researchers Second Edition. London: SAGE Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Lehmann V, Kutteh WH, Sparrow CK, et al. Fertility-related services in pediatric oncology across the cancer continuum: a clinic overview. Support Care Cancer. 10.1007/s00520-019-05248-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Benedict C, Ahmad Z, Lehmann V, et al. (2020) Adolescents and Young Adults In: Watson M, Kissane D (eds) Sexual health, fertility, and relationships in cancer care. Oxford University Press; 10.1093/med/9780190934033.001.0001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Speller B, Sissons A, Daly C, et al. (2019) An evaluation of oncofertility decision support resources among breast cancer patients and health care providers. BMC Health Serv Res 19:101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Benedict C, McLeggon J-A, Thom B, et al. (2018) 'Creating a family after battling cancer is exhausting and maddening': Exploring real-world experiences of young adult cancer survivors seeking financial assistance for family building after treatment. Psychooncology 27:2829–2839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Cheung CK, Zebrack B (2017) What do adolescents and young adults want from cancer resources? Insights from a Delphi panel of AYA patients. Support Care Cancer 25:119–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Rabin C, Simpson N, Morrow K, et al. (2011) Behavioral and psychosocial program needs of young adult cancer survivors. Qual Health Res 21:796–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Kelvin JF. Organizational strategies to overcome barriers to addressing fertility preservation in the oncology setting In: Azim HA Jr, Demeestere I, Peccatori FA (eds) Fertility challenges and solutions in women with cancer. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 57–66. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Anazodo A, Laws P, Logan S, et al. (2019) How can we improve oncofertility care for patients? A systematic scoping review of current international practice and models of care. Hum Reprod Update 25:159–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Micro-video: Creating a Comprehensive Fertility Preservation Program | American Society for Reproductive Medicine, https://www.asrm.org/resources/videos/micro-videos/2019-micro-videos/creating-a-comprehensive-fertility-preservation-program/ (accessed 21 January 2020).

- [31].Vadaparampil ST, Gwede CK, Meade C, et al. (2016) ENRICH: a promising oncology nurse training program to implement ASCO clinical practice guidelines on fertility for AYA cancer patients. Patient Educ Couns 99:1907–1910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Vadaparampil S, Kelvin J, Murphy D, et al. (2016) Fertility and fertility preservation: scripts to support oncology nurses in discussions with adolescent and young adult patients. J Clinical Outcomes Management https://www.mdedge.com/jcomjournal/article/146948/practice-management/fertility-and-fertility-preservation-scripts-support (accessed 17 July 2019).

- [33].Woodruff TK, Gosiengfiao YC (2017) Pediatric and adolescent oncofertility: best practices and emerging technologies. Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- [34].van den Berg M, Nadesapillai S, Braat DDM, et al. (2020) Fertility navigators in female oncofertility care in an academic medical center: a qualitative evaluation. Support Care Cancer. 10.1007/s00520-020-05412-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [35].The ECHO Training Program – Enriching Communication Skills for Health Professionals in Oncofertility, https://echo.rhoinstitute.org/ (accessed 26 February 2020).

- [36].Quinn G, Bleck J, Stern M (2020) A review of the psychosocial, ethical, and legal considerations for discussing fertility preservation with adolescent and young adult cancer patients. Clinical Practice in Pediatric Psychology 8:86–96. [Google Scholar]

- [37].Levin NJ, Zebrack B, Cole SW (2019) Psychosocial issues for adolescent and young adult cancer patients in a global context: a forward-looking approach. Pediatric Blood & Cancer e27789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Benedict C, Hahn AL, Diefenbach MA, et al. (2019) Recruitment via social media: advantages and potential biases. Digital Health 5:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.