Abstract

Introduction:

Improving surgical care in a resource-limited setting requires the optimization of operative capacity, especially at the district hospital level.

Methods:

We conducted an analysis of the acute care surgery registry at Salima District Hospital (SDH) in Malawi from June 2018 to November 2019. We examined patient characteristics, interventions, and outcomes. Modified Poisson regression modeling was used to identify risk factors for transfer to a tertiary center, and mortality of patients transferred to the tertiary center.

Results:

888 patients were analyzed. The most common diagnosis was skin and soft tissue infection (SSTI) at 35.9%. 27.5% of patients were transferred to SDH, primarily from health centers, with a third for a diagnosis of SSTI. Debridement of SSTI comprised 59% of performed procedures (n=241). Of the patients that required exploratory laparotomy, only 11 laparotomies were performed, with 59 patients transferred to a tertiary hospital. The need for laparotomy conferred an adjusted risk ratio (RR) of 10.1 (95% CI 7.1, 14.3) for transfer to the central hospital. At the central hospital, for patients who needed urgent abdominal exploration, surgery had a 0.16 RR of mortality (95% CI 0.05, 0.50) while time to evaluation greater than 48 hours at the central hospital had a 2.81 RR of death (95% CI 1.19, 6.66).

Conclusions:

Despite available capacity, laparotomy was rarely performed at this district hospital and delays in care led to a higher mortality. Optimization of the district and health center surgical ecosystems is imperative to improve surgical access in Malawi and improve patient outcomes.

Keywords: general surgery, sub-Saharan Africa, transfers

Introduction

Safe and reliable surgical care remains elusive in many regions throughout the world.1 Investment in surgical capacity in many low and middle-income countries (LMIC) has led to substantial growth in the delivery of surgical care at urban, tertiary hospitals but district-level hospitals have been largely neglected.2, 3 These improvements, while critical, represent only one piece of the puzzle as the development of a national surgical system requires improving available surgical services at multiple levels. In a tiered hospital system, seen in many post-colonial health care systems in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), system building must occur at both district hospitals and community health centers, where most patients enter the health care system. One vital component of health system building is the optimization of currently available resources, which continue to suffer resource limitations despite significant infrastructure investment. Malawi, for example, had only 0.4 physicians per 10,000 people in 2018 compared to 9 per 10,000 people in South Africa and 26 per 10,000 people in the United States.4

Many gaps in clinical care created by resource limitations are filled with task-shifting by providers with less clinical training or by transfer to larger, more equipped tertiary centers. While the transfer to a higher level of care for more complex patients is often necessary, tertiary centers have a finite patient capacity, and travel to tertiary hospitals is often very challenging for patients living in rural areas throughout SSA. Consequently, it is imperative that lower levels of the health care system provide basic, and often life-saving, surgical services.5 These essential surgical services have recently been defined by the ability of a district-level hospital to perform the three “Bellwether Procedures”: laparotomy, cesarean section, and the treatment of open fractures.6 While performing a laparotomy may require complex post-operative care, O’Neill et al provided compelling evidence that the ability to perform this procedure along with cesarean section and open fracture treatment demonstrates that a hospital likely has the necessary infrastructure to provide an array of essential surgical services, avoiding the costly need for transfer to other facilities.

When there is an inappropriate shift of services to a higher level of care from a health center to a district hospital or from a district hospital to the tertiary center, there is an effect on the quality of patient care due to inter-hospital delays and the costs incurred for transportation. There is also a parallel, cascading effect on the entire system as more patients are funneled toward a strained tertiary hospital. These effects ultimately represent an underutilization between available surgical capacity and surgical care delivery. Unfortunately, there is limited data on the extent of this phenomenon among general surgery patients in SSA. As a result, we sought to describe how surgical capacity underutilization is occurring at a district hospital in Malawi and the consequences on mortality for patients with acute general surgery complaints.

Methods

This study is a prospective, observational analysis of patients evaluated at Salima District Hospital (SDH) with an acute general surgery complaint and the patients subsequently transferred to Kamuzu Central Hospital (KCH) in Lilongwe. District hospitals are secondary level hospitals in the healthcare system in Malawi. A surgeon is not available at the district hospital but clinical officers, capable of cesarean section and potentially laparotomy, are available twenty-four hours a day, as well as nurse anesthetists. There are typically only one or two physicians at each district hospital with both clinical and administrative responsibilities. There are no ICU beds available in the district hospitals and blood banking is limited. Lastly, there are usually one or two operating rooms, most often utilized for c-sections. SDH has approximately 100 hospital beds with one operating theatre, staffed 24 hours a day by three clinical officers trained in surgery and three nurse anesthetists. The clinical officer program was established in 1976 in Malawi and requires three years of clinical medicine training at the Malawi College of Medicine followed by the equivalent of a yearlong internship. They are independently licensed and proved a majority of medical care at the district and regional hospital.7 Clinical officers that provide surgical services have two years of dedicated surgical training.

KCH, as the tertiary referral center for the central region of the country, has 6 non-obstetric operating theatres with 24/7 coverage by consultant and trainee physician general surgeons as well as various sub-specialist surgeons. All patients presenting to either hospital were recorded in an acute general surgery registry. The SDH registry was established in June 2018 to record all patients that present to the hospital with a general surgery complaint. The KCH registry was established in 2013. Registry staff collected and record data in casualty and on the wards daily. Data points captured include basic patient demographic information, clinical characteristics, operative intervention, and information regarding prior transfer from the lower-level facility and outcomes (death, discharge, or transfer to a higher level of care) between other facilities. Upper gastrointestinal bleeding is included as a surgical diagnosis because it is primarily managed by surgeons in Malawi due to limited endoscopy availability. Patients less than 12 years old were excluded as they are typically managed by pediatric surgeons. We included patients who presented from the dates June 2018 through March 2020.

We defined underutilization of surgical capacity as a patient transfer for a surgical service from a facility with the potential capacity to offer the appropriate surgical intervention. The primary aim of the study was to describe the potential underutilization of operative capacity at the district hospital for patients needing an exploratory laparotomy. We accomplished this by examining the patients that presented to the district hospital with an acute general surgery complaint and were subsequently transferred to the tertiary hospital, KCH. We examined factors associated with transfer to KCH and the clinical outcomes of those patients that were transferred to the tertiary hospital, KCH, located in Lilongwe, Malawi, approximately a two-hour drive from Salima.

We initially explored the baseline characteristics of all patients in the study, describing demographic and clinical data. We also compared patients based on whether they were transferred to KCH. We performed a bivariate analysis to analyze the relationship between variables and transfer to KCH, using Chi-squared tests for the categorical variables and 2-sample t-tests for continuous variables. For any non-normally distributed continuous variables, we used a Kruskal-Wallis test. Means were reported with standard deviations (SD) and medians with interquartile ranges (IQR). Overall crude mortality was calculated using any in-hospital deaths in the study population.

We used a modified Poisson regression model to estimate the risk factors for transfer to KCH, as well as the risk of mortality for patients transferred to KCH, adjusted for confounders.8,9 After building the model with transfer status and all potential confounders, we used a change-in-effect method to fit the model with significant covariates. We then sequentially removed variables based on their effect on the point estimate. Variables that changed the point estimate < 10% were removed from the model. An estimated adjusted risk ratio (RR) and 95% confidence interval are reported from the final model. The expected need for exploratory laparotomy was defined as patients with laparotomy documented as the reason for transfer or patients with a diagnosis necessitating exploratory laparotomy.

We performed all statistical analyses using Stata/SE 16.0 (Stata- Corp LP, College Station, TX). Ethics approval and a waiver for informed consent was obtained from the University of North Carolina Institutional Review Board and the Malawi National Health Sciences Research Committee. The University of North Carolina Department of Surgery provided funding.

Results

During the study, 888 patients were evaluated at SDH for an acute general surgery complaint. The median age for all patients was 40 years (IQR 25–55), and 65.6% (n=583) were male. The most common admission diagnosis was soft tissue infection at 35.9% (n=319/888) followed by inguinal or abdominal wall hernia at 17.7% (n=157/888), and upper gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding at 13.2% (n=117/888). A quarter of patients (27.5%, n=242/888) were transferred from another facility for evaluation at SDH. Among those transferred to SDH, the majority came from health centers (70.0%, n=169/242) and private hospitals (23.4%, n=57/242). The most common diagnosis for these transferred patients was soft tissue infections at 31.8% (n=77/242). The rest were primarily for upper GI bleeding (16.1%, n=39/242), abdominal or inguinal hernias (13.5%, n=33/242), and bowel obstructions (10.3%, n=25/242).

For all presenting patients to SDH, almost half had an operation at SDH (46.3%, n=411/888), with nearly two-thirds of patients having abscess drainage or debridement of infected soft tissue (58.6%, n=241/411). A small number of patients had an amputation for severe infection (2.9%, n=12/411). Inguinal or abdominal wall hernia repair was also common at 109 patients (26.6%, n=109/411). Only 11 patients (2.6%, 11/411) had an exploratory laparotomy. Overall, crude mortality for all patients was 1.9% (n=17/888).

Transfers to Kamuzu Central Hospital

Among the patients evaluated at SDH, 10.8% (96/888) were transferred to the tertiary hospital, KCH. (Table 1) Ages were similar between those who were transferred and those who were not, at a median of 43 years (IQR 26–59) and 40 years (IQR 25–55, p=0.3), respectively, with a similar sex composition (p=0.4). Patients from both cohorts had relatively normal vital signs on presentation with a mean heart rate of 90 beats per minute (p=0.7) and a mean systolic blood pressure of 125 mmHg (p=0.6). Approximately one-third of patients in both groups were transferred from another facility before evaluation at SDH (p=0.4). Most came from a health center in both groups at 72.3% in the non-transferred cohort and 62.5% in the transferred cohort (p=0.07). The primary admission diagnosis was different between the groups. Soft tissue infection was the most common diagnosis in the non-transferred patients (38.6% vs. 13.5%, p<0.001) with bowel obstruction, the most common in the transferred group (3.3% vs. 42.7%, p<0.001). About half of patients (49.5%, n=392) that were not transferred had an operation at SDH, while 19.8% (n=19/96) of those transferred to KCH had an operation prior to transfer.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients transferred to the tertiary center, Kamuzu Central Hospital (KCH) versus those who were not.

| Non-transferred Patients (n=792) |

Transferred Patients (n=96) |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Age (years) | |||

| Median (IQR) | 40 (25–55) | 43 (26–59) | 0.3 |

| Sex: n (%) | |||

| Female | 356 (33.4) | 35 (31.3) | 0.4 |

| Male | 526 (32.3) | 57 (59.4) | |

| Missing | 10 (1.3) | 1 (1.0) | |

| Presenting Vital Signs: Mean (SD) | |||

| Heart Rate | 89 (32) | 90 (19) | 0.7 |

| Systolic Blood Pressure | 126 (17) | 124 (17) | 0.6 |

| Transferred to SDH: n (%) | |||

| Yes | 210 (26.5) | 32 (33.3) | 0.4 |

| If transferred, from where? n (%) | |||

| Health Center | 149 (72.3) | 20 (62.5) | 0.07 |

| Private Hospital | 49 (23.8) | 8 (25.0) | |

| Other | 12 (5.7) | 4 (12.5) | |

| Common Admission Diagnoses: n (%) | |||

| Soft Tissue Infection | 306 (38.6) | 13 (13.5) | <0.001 |

| Inguinal or Abdominal Hernia | 145 (18.3) | 12 (12.5) | |

| Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding | 109 (13.8) | 8 (8.3) | |

| Bowel Obstruction | 26 (3.3) | 41 (42.7) | |

| Acute Appendicitis | 13 (1.6) | 2 (2.1) | |

| Acute Abdomen | 5 (0.6) | 6 (0.8) | |

| Surgery at SDH: n (%) | |||

| Yes | 392 (49.5) | 19 (19.8) | <0.001 |

When examining those that were transferred, 33.3% (32/96) had been transferred to SDH from another facility prior to a second transfer to KCH. For these patients initially seen at a health center, the median time from initial evaluation by a healthcare provider to arrival at KCH was 3 days (IQR 0–5 days). The majority of all transferred patients (61.4%, n=59/96) were sent to KCH for an expected need for exploratory laparotomy. Of these 59 patients needing exploratory laparotomy at KCH, 39.0% (n=23/59) were initially transferred to SDH from another facility before a second transfer to KCH. The expected need for an exploratory laparotomy conferred an adjusted risk ratio of transfer to KCH of 10.1 (95% CI 7.1, 14.3, p<0.001). No other variables were significantly associated with transfer. (Table 2) Age, gender, admission diagnosis, presentation to a health care center, whether the patient had surgery at SDH, and admission vital signs were not significant in the model testing and were not included.

Table 2.

Risk factors for transfer to Kamuzu Central Hospital (KCH) and mortality at KCH once transferred.

| Relative Risk (95% Confidence Interval) | p value | |

|---|---|---|

| Risk Factors for Transfer to KCH | ||

| Expected Need for Laparotomy | 10.1 (7.1, 14.3) | <0.001 |

| Risk Factors for In-hospital Mortality After T ransfer to KCH | ||

| Operative Exploration | 0.16 (0.05, 0.50) | 0.002 |

| Time to Evaluation at KCH > 48 hours | 2.81 (1.19, 6.66) | 0.018 |

Underutilization

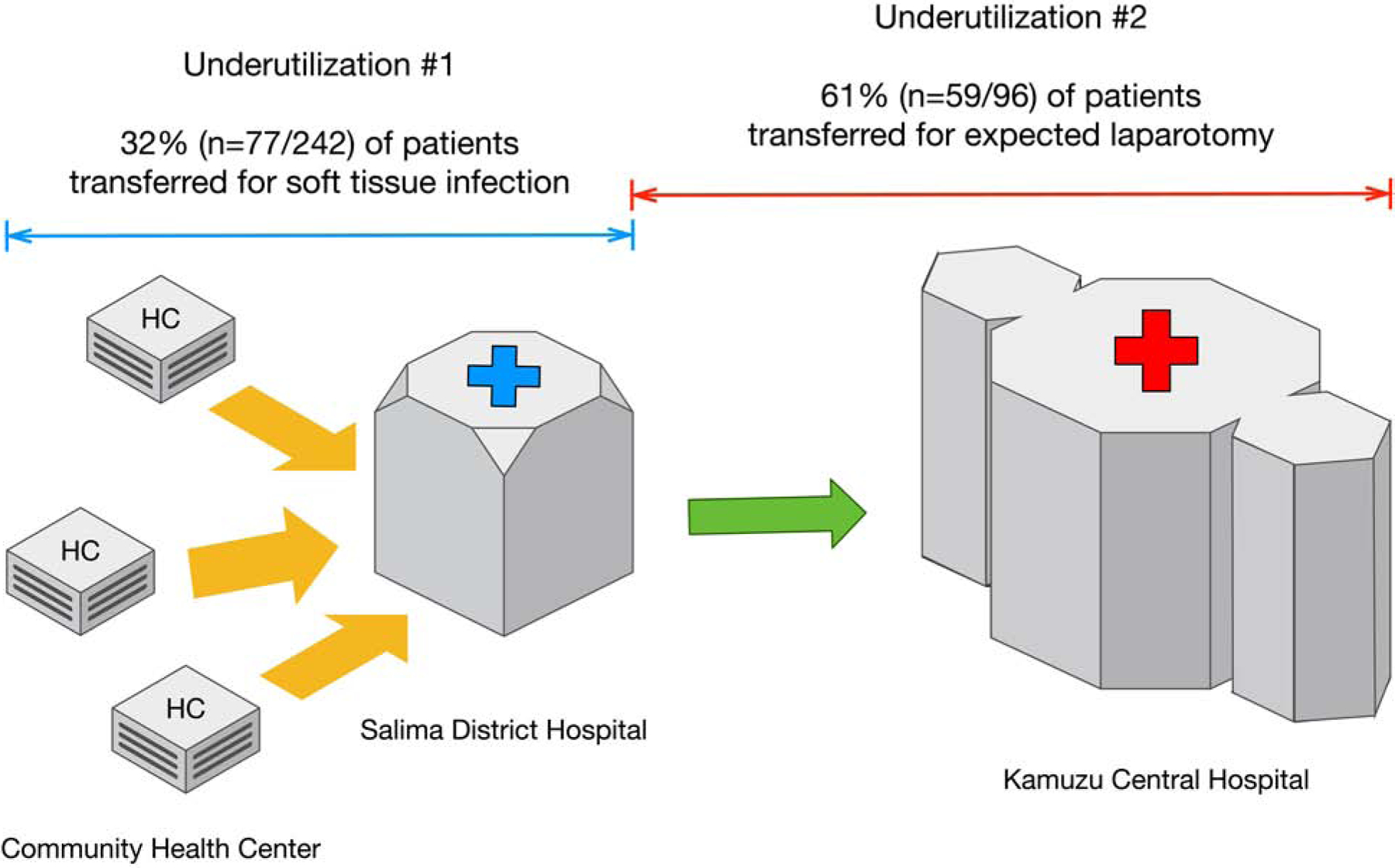

The first underutilization of surgical capacity occurred at the community health center, where a significant number of patients were transferred to SDH for simple soft tissue infections. This diagnosis was the reason for transfer to SDH in almost a third of patients. (Figure 1). The second underutilization of surgical capacity occurred when patients needing exploratory laparotomy presenting to SDH were transferred to the central hospital, despite SDH having the facilities to perform this procedure. Over half of patients transferred to KCH were sent for this reason.

Figure 1.

Underutilization of surgical capacity and surgical intervention between the community health center, Salima District Hospital, and Kamuzu Central Hospital.

Clinical Outcomes at KCH

Ninety-six patients were transferred to KCH. Once there, 63.5% (n=61) of patients had surgery at KCH with a median time to surgery of 2 days (IQR 1–8). A majority of the patients transferred to KCH (67.6%, n=65) had a documented indication for exploratory laparotomy, but only 70.8% (n=46) of these patients had an operation. The median time to surgery for patients who had abdominal exploration was 1 day (IQR 0–4). The most common procedures performed among those who had a laparotomy were colon resection (9.8%, n=6) and Graham patch repair of perforated gastric ulcer (8.2%, n=5). Also, 7 patients had an inguinal hernia repair (11.5%, n=11). Other common non-abdominal procedures were for soft tissue infections, including debridement (13.1%, n=8) or lower extremity amputations (3.3%, n=2).

For all patients transferred to KCH from SDH, in-hospital crude mortality was 16.7% (n=16). Among patients with a documented need for exploratory laparotomy, crude in-hospital mortality was 47.4% (n=9/19) for patients who were not explored and 6.5% (n=3/43, p<0.001) for those who did have surgery at KCH. After modeling for factors associated with death in patients who needed exploratory laparotomy, time to evaluation at KCH, greater than 48 hours from the time of initial presentation to a health care facility, had a RR of mortality of 2.81 (95% CI 1.19, 6.66, p=0.018). Undergoing surgery was protective with an adjusted RR of 0.16 (95% CI 0.05, 0.50, p=0.002). Age, gender, admission diagnosis, presentation to a health care center, and admission vital signs were not significant in the model and were not included. (Table 2)

Discussion

This is one of the first studies in the region to describe the path of general surgery patients following an acute surgical complaint and moving through the health care system from the community health center, to the district hospital, and on to the tertiary center in a resource-limited setting. We demonstrate underutilization between the operative capacity of the district hospital and the delivery of surgical services. Despite having the facilities and staffing to perform an exploratory laparotomy, the district hospital only performed 11 abdominal explorations over a nearly two-year period. For patients that were transferred, non-operative intervention, and time to evaluation at KCH were associated with an increased risk of mortality. Instead of performing needed exploratory laparotomies, the district hospital primarily performed incision and drainage of soft tissue infections or non-urgent inguinal hernia repairs. Our data are consistent with previous findings from both Malawi and nearby Uganda.10, 11

The downstream effects of capacity underutilization affect the entire system. Many hospitals in the region are overwhelmed at baseline with limited resources and a high patient volume.12 Underutilization first occurs with unnecessary transfer to the district hospital for basic surgical issues, which consumes resources and the time of surgical providers in a resource-limited facility. At SDH, over a third of patients were transferred from community health centers, many for simple soft tissue infections that could have been managed locally with basic supplies and training. SDH then subsequently used almost two-thirds of its capacity managing these infections instead of providing more Bellwether procedures. The second level of underutilization occurs as a consequence of the first, as patients are sent to the tertiary center for operations, such as exploratory laparotomy, that could have been managed at the district level. This leads to poor patient outcomes at the overwhelmed tertiary center due to delays or limited patient capacity resulting in improper non-operative management of some patients. We previously showed that patients with acute abdomen transferred to KCH from surrounding district hospitals had increased mortality due to delays in care.13 Our study suggests this increase in mortality is due to delays in care or in the worst-case scenario, no intervention at all, due to overwhelmed staffing and facilities.

The “Bellwether Procedures” include exploratory laparotomy, a procedure rarely offered at SDH, that was the primary reason for transfer to the tertiary center. Many of these patients were diagnosed with a bowel obstruction, not more complex surgical diagnoses requiring tertiary care. This suggests there is room for substantial improvement of capacity utilization at the district level. Public health efforts have identified the vital role of district hospital capacity building in improving health care delivery in LMIC with evidence that increased surgical services at the district level can improve outcomes.14,15 The district hospital is the entry point for medical care for most SSA patients, especially those in rural areas.14 While care in many high-income countries has transitioned to regionalized care at tertiary centers, this is simply not feasible in many countries in SSA with populations predominantly living in rural areas where inter-hospital transportation is scarce or non-existent. Transportation to central hospitals in larger cities is often time-consuming and costly, creating substantial barriers to access to surgical care for a substantial proportion of patients.16,17 While distance to care is not the only barrier, it is clear that patients need affordable, proximal access to hospitals that can provide essential surgical services.

There are certainly challenges to providing this level of surgical care at district hospitals where there are needs across several domains.18 The ability to perform one of the Bellwether procedures requires appropriate facilities, surgical equipment, surgeons, and anesthesia providers. Previous data from other SSA district hospitals have revealed similar laparotomy rates to ours and have identified a lack of trained providers as one of the major limiting factors.19–21 Even in countries with more developed surgical training infrastructure like Ghana, trained surgeons are not routinely working in district hospitals, and care has relied heavily on medical officers with minimal or no surgical training.22 This has led to several regional efforts aimed at either increasing the number of surgeons available in district hospitals or task-shifting certain procedures to other providers that lack surgical training.

Published data suggests task-shifting is a reasonable approach in equipped environments and may improve patient outcomes. For example, a 2009 study from Niger studied the effects of a government initiative to increase surgical services by training general practitioners at three district hospitals for one year on common general surgery procedures and cesarean sections.23 They reported favorable clinical outcomes, even from emergency surgery, and showed a 50–80% reduction in hospital transfer compared to the period before the initiative. Data from a 2017 study in Zambia identified several potential benefits of a similar task-shifting program. Despite some challenges, they showed that such a program was feasible and improved surgical capacity at smaller hospitals.24 A 2011 Medecins Sans Frontieres (MSF) study showed that task-shifting was effective in a conflict zone in Somalia for trauma-related operations.25 Older data from Malawi focused on task shifting for obstetric procedures have also reported good outcomes.26 Other strategies have also been explored in the region including one program that developed a model providing intermittent, scheduled specialist surgeon supervision of non-physician clinicians at district hospitals with an increase in procedures performed and a decrease in transfers.27 In the context of our study, the caveat is that very little data exists on laparotomy specifically, which does carry higher risks than many of the other procedures studied. While we do not have data on why laparotomies were not performed at the district hospital, experience with performing the procedure is certainly an important factor. More investment in these programs is imperative to avoid overwhelming the central hospital and wasting the available the resources at the district level. Going forward, we plan to partner with the district hospital in Salima to improve general surgery training and provide more senior surgical providers for mentorship. This will include training for current clinical officers and for future surgical residents rotating at SDH. Our experience at KCH suggests that clinical officers, with appropriate oversight and training, are more than capable of performing these procedures.

In addition to provider shortages, previous research has also documented there are severe deficiencies in available supplies, medications, basic staffing, surgical equipment, and disposal of hazardous materials at many of district hospitals throughout the region.28 None of these interventions are easy and require a substantial financial commitment from the government. However, data has shown that investment in improving district hospital surgical care is cost-effective. A 2014 systematic review found that providing essential surgical services at a small district hospital was highly cost-effective at only 1 $USD per DALY averted, a better value than most other interventions studied.29 A 2016 study examined the cost-effectiveness of the Bellwether procedures at a single district hospital in Zambia and found that all of them were highly cost-effective, including emergency laparotomy at 8.62 $USD per DALY averted.30 Other cost-effectiveness data from LMIC have provided similar evidence that district hospital surgical care investment is highly cost-effective.31, 32

Our study is limited by the complexities of collecting data in a resource-limited environment at two different hospitals. Linking data between patients at SDH and KCH is challenging, which is exacerbated by an underdeveloped and irregular patient transfer system between the hospitals. A communication system was established between SDH and KCH data clerks to assist providers at the receiving hospital and improve data collection. In addition, we do not have access to routine lab information or advanced imaging such as computerized tomography (CT) scans. This limits our ability to verify diagnoses obtained by providers, and there may be some bias on the severity of a patient’s illness depending on the clinician evaluator. We have mitigated this as much as possible by controlling for available patient variables that may be associated with mortality. Lastly, the number of patients included in our modeling was relatively small. This may overestimate the point estimate of the calculated risk ratios.

Conclusion

Despite available surgical staff and equipment, exploratory laparotomy was rarely performed at this district hospital. Soft tissue infection was overwhelmingly the most common diagnosis and indication for surgery, which was likely treatable at a lower level health facility. For patients that were transferred to the tertiary hospital, operative intervention was life-saving when offered. Still, many patients did not receive needed abdominal exploration, and an increase in time to evaluation at the tertiary hospital was associated with an increased risk of death. Optimization of the district and health center surgical ecosystems is imperative to increase surgical access in Malawi and improve patient outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at UNC. REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) is a secure, web-based application designed to support data capture for research studies, providing: (1) an intuitive interface for validated data entry; (2) audit trails for tracking data manipulation and export procedures; (3) automated export procedures for seamless data downloads to common statistical packages; and (4) procedures for importing data from external sources.

Funding Support:

This work was funded by the Department of Surgery at the University of North Carolina and The National Institutes of Health, Fogarty International Center (Laura N. Purcell: Grant D43TW009340).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Meeting Presentation: Accepted at the American College of Surgeons 106th Annual Clinical Congress, Scientific Forum, Chicago, IL, October 2020.

The authors report no proprietary or commercial interest in any product mentioned or concept discussed in this article

References

- 1.Meara JG, Leather AJ, Hagander L, et al. Global Surgery 2030: evidence and solutions for achieving health, welfare, and economic development. The Lancet. 2015;386:569–624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grudziak J, Gallaher J, Banza L, et al. The Effect of a Surgery Residency Program and Enhanced Educational Activities on Trauma Mortality in Sub-Saharan Africa. World J Surg. 2017;41:3031–3037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Warren AE, Wyss K, Shakarishvili G, et al. Global health initiative investments and health systems strengthening: a content analysis of global fund investments. Global Health. 2013;9(1):30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. The 2018 update, global health workforce statistics. World Health Organization, Geneva: 2018. http://www.who.int/hrh/statistics/hwfstats/. Accessed: July 7, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Henry JA, Bem C, Grimes C, et al. Essential surgery: the way forward. World J Surg 2015;39:822–832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Neill KM, Greenberg SL, Cherian M, et al. Bellwether procedures for monitoring and planning essential surgical care in low-and middle-income countries: caesarean delivery, laparotomy, and treatment of open fractures. World J Surg. 2016;40:2611–2619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tyson AF, Msiska N, Kiser M, et al. Delivery of operative pediatric surgical care by physicians and non-physician clinicians in Malawi. Int J Surg. 2014. May 1;12(5):509–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zou G A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:702–706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen W, Qian L, Shi J, et al. Comparing performance between log-binomial and robust Poisson regression models for estimating risk ratios under model misspecification. Med Res Methodol. 2018;18:63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ozgediz D, Galukande M, Mabweijano J, et al. The neglect of the global surgical workforce: experience and evidence from Uganda. World J Surg. 2008;32:1208–1215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lavy C, Tindall A, Steinlechner C, et al. Surgery in Malawi–a national survey of activity in rural and urban hospitals. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2007;89:722–724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilson RM, Michel P, Olsen S, et al. Patient safety in developing countries: retrospective estimation of scale and nature of harm to patients in hospital. Bmj. 2012;344:e832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Purcell LN, Robinson B, Msosa V, et al. District General Hospital Surgical Capacity and Mortality Trends in Patients with Acute Abdomen in Malawi. World J Surg. 2020;1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rajbhandari R, McMahon DE, Rhatigan JJ, et al. The Neglected Hospital-The District Hospital’s Central Role in Global Health Care Delivery. NEJM. 2020;382:397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Henry JA. Decentralization and Regionalization of Surgical Care as a Critical Scale-up Strategy in Low-and Middle-Income Countries; Comment on “Decentralization and Regionalization of Surgical Care: A Review of Evidence for the Optimal Distribution of Surgical Services in Low-and Middle-Income Countries”. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2020;8(9):521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grimes CE, Bowman KG, Dodgion CM, et al. Systematic review of barriers to surgical care in low-income and middle-income countries. World J Surg. 2011;35:941–950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rutherford ME, Mulholland K, Hill PC. How access to health care relates to under-five mortality in sub-Saharan Africa: systematic review. Trop Med Int Health. 2010;15:508–519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gosselin RA, Gyamfi Y-A, Contini S. Challenges of meeting surgical needs in the developing world. World J Surg. 2011;35:258–261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Galukande M, von Schreeb J, Wladis A, et al. Essential surgery at the district hospital: a retrospective descriptive analysis in three African countries. PLoS medicine. 2010;7(3) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kalu QN, Eshiet AI, Ukpabio EI, et al. A Rapid Need Assessment Survey of Anaesthesia and Surgical Services in District Public Hospitals in Cross River State, Nigeria. Brit J of Med Pract. 2014;7(4) [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abdullah F, Choo S, Hesse AA, et al. Assessment of surgical and obstetrical care at 10 district hospitals in Ghana using on-site interviews. J Surg Res. 2011;171:461–466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Choo S, Perry H, Hesse AA, et al. Surgical training and experience of medical officers in Ghana’s district hospitals. Acad Med. 2011;86:529–533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sani R, Nameoua B, Yahaya A, et al. The impact of launching surgery at the district level in Niger. World J Surg. 2009;33:2063–2068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gajewski J, Mweemba C, Cheelo M, et al. Non-physician clinicians in rural Africa: lessons from the Medical Licentiate programme in Zambia. Hum Resour Health. 2017;15:53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chu KM, Ford NP, Trelles M. Providing surgical care in Somalia: a model of task shifting. Confl Health. 2011;5:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chilopora G, Pereira C, Kamwendo F, et al. Postoperative outcome of caesarean sections and other major emergency obstetric surgery by clinical officers and medical officers in Malawi. Hum Resour Health. 2007;5:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gajewski J, Monzer N, Pittalis C, et al. Supervision as a tool for building surgical capacity of district hospitals: the case of Zambia. Hum Resour Health. 2020;18:1–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hsia RY, Mbembati NA, Macfarlane S, et al. Access to emergency and surgical care in sub-Saharan Africa: the infrastructure gap. Health Policy Plan. 2012;27:234–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grimes CE, Henry JA, Maraka J, et al. Cost-effectiveness of surgery in low-and middle-income countries: a systematic review. World J Surg. 2014;38:252–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roberts G, Roberts C, Jamieson A, et al. Surgery and obstetric care are highly cost-effective interventions in a sub-Saharan African district hospital: a three-month single-institution study of surgical costs and outcomes. World J Surg. 2016;40:14–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gosselin RA, Heitto M. Cost-effectiveness of a district trauma hospital in Battambang, Cambodia. World J Surg. 2008;32:2450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gosselin RA, Thind A, Bellardinelli A. Cost/DALY averted in a small hospital in Sierra Leone: what is the relative contribution of different services? World J Surg. 2006;30:505–511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]