Abstract

Numerical and/or structural centrosome amplification (CA) is a hallmark of cancers that is often associated with the aberrant tumor karyotypes and poor clinical outcomes. Mechanistically, CA compromises mitotic fidelity and leads to chromosome instability (CIN), which underlies tumor initiation and progression. Recent technological advances in microscopy and image analysis platforms have enabled better-than-ever detection and quantification of centrosomal aberrancies in cancer. Numerous studies have thenceforth correlated the presence and the degree of CA with indicators of poor prognosis such as higher tumor grade and ability to recur and metastasize. We have pioneered a novel semi-automated pipeline that integrates immunofluorescence confocal microscopy with digital image analysis to yield a quantitative centrosome amplification score (CAS), which is a summation of the severity and frequency of structural and numerical centrosome aberrations in tumor samples. Recent studies in breast cancer show that CA increases across the disease progression continuum. While normal breast tissue exhibited the lowest CA, followed by cancer-adjacent apparently normal, ductal carcinoma in situ and invasive tumors, which showed the highest CA. This finding strengthens the notion that CA could be evolutionarily favored and can promote tumor progression and metastasis. In this review, we discuss the prevalence, extent and severity of CA in various solid cancer types, the utility of quantifying amplified centrosomes as an independent prognostic marker. We also highlight the clinical feasibility of a CA-based risk score for predicting recurrence, metastasis, and overall prognosis in patients with solid cancers.

Keywords: Centrosome amplification, prognostic biomarker, solid tumors, formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue sections, DCIS

INTRODUCTION

Over a century ago, Edouard van Beneden (1883) discovered a minute cell organelle [1,2], which Theodore Boveri (1888) called the “cytocentrum” or “cell center”; the organelle was later named “centrosome”. Boveri described centrosomes as the true division organ of the cell, orchestrating the nuclear and cellular division. He observed a spherical refractive body at each end of the mitotic spindle in Ascaris megalocephalia embryos, and named them “polkörperchen” or polar corpuscles [3–5]. In the following decade, Boveri focused on the mechanisms of centrosome duplication, and observed that during cell division, the mother centrosome became ellipsoidal and was cleaved, giving rise to two daughter centrosomes. Based on this finding, he postulated that the daughter centrosomes migrate towards the opposite poles of the cell and induce the formation of the mitotic spindle. Boveri was also the first to propose that centrosome abnormalities lead to aneuploidy-initiated tumor formation.

Commonly called the microtubule organizing center (MTOC), a centrosome consists of two barrel-shaped centrioles, each consisting of nine microtubule (MT) triads embedded in an amorphous cloud of peri-centriolar matrix (PCM) [6–8]. PCM proteins include those involved in centriole assembly, MT anchorage and spindle formation (e.g., pericentrin and γ-tubulin), as well as kinases involved in centriole biogenesis, cell cycle regulation and microtubule nucleation [8,9]. The minuscule (<1 μm in diameter) size of centrosomes does not accurately reflect the enormity of the cellular workload they shoulder. Centrosomes function as coordination centers in eukaryotic cells and orchestrate signal transduction, cell division, polarity and migration. During mitosis, centrosomes are indispensable for bipolar spindle formation and faithful chromosome segregation (Fig. 1, normal cell), and any disruption in their function can lead to disorganized mitotic spindles and chromosomal missegregation, ultimately causing chromosomal instability (CIN) and aneuploidy (Fig. 1, cancer cell) [10–14].

Figure 1:

Confocal immunomicrographs and graphic illustration of a normal and cancer cell with extra centrosomes across the different phases of the cell cycle. Centrosomes and microtubules were immunolabeled for γ-tubulin (green) and α-tubulin (red), respectively, and DNA was counterstained with Hoechst (blue). Scale bar (white) = 5 μm.

Under physiological conditions, the duplication of centrioles is spatially and temporally synchronized with DNA replication in the cell cycle to ensure that each daughter cell receives only one pair of centrioles (and one centrosome) [15,16]. Essentially, the centrioles are first “primed” for duplication in the early G1 phase by the cleavage of pericentrin, which results in centriole disengagement [17]. This process is regulated by cyclin dependent kinase 1 (CDK1), the polo-like kinase 1 (PLK-1), and Aurora kinase A [18]. Duplication of the parental centriole is initiated during G1/S transition by PLK4 that sequentially recruits SIL/STIL, hSAS-6, CEP135, CEP295, CEP152, and γ-tubulin, which are the building blocks of the procentrioles [19–23]. The newly formed procentrioles elongate throughout the G2 phase, and the two mature centrosomes migrate to the opposite ends of the cell to organize the bipolar mitotic spindle as the cell enters the late G2/M phase. Following cytokinesis, each daughter cell is left with one centrosome consisting of two disengaged centrioles. Any defect or disturbance during the duplication and elongation/maturation stages results in centrosomal abnormalities [24,25].

Aberrations in centrosome size, shape, number, and position are collectively known as centrosome amplification (CA) (Fig. 2) [26]. Unsurprisingly, CA is seen across a spectrum of human cancers and is often associated with the aberrant karyotypes and genomic instability of cancer cells, as well as disease progression and poor patient prognosis [27–30]. These findings indicate the potential clinical significance of CA as a diagnostic and prognostic marker in cancer. In this review, we discuss the prevalence, extent and severity of CA in various cancer types, the utility of quantifying amplified centrosomes as an independent prognostic marker, and the clinical feasibility of a CA-based risk score for predicting recurrence, metastasis, and overall prognosis in patients with solid cancers.

Figure 2:

Representative confocal immunomicrographs showing numerical and structural centrosome aberrations in normal and cancerous breast and prostate tissue sections. Centrosomes were immunolabeled for γ-tubulin (green), microtubules were immunolabelled for α-tubulin (red), and DNA was counterstained with Hoechst (blue). Scale bar (white line at the lower right of each panel) = 5 μm.

There are two main types of CA as follows:

Numerical amplification:

Supernumerary centrosomes result from abnormal centriole biogenesis due to centriole overduplication and de novo assembly, or mitotic/cytokinetic failure or fusion which passively increase the centrosome copy number in a sub-population of progeny cells [31–35]. Deregulation of the centrosome duplication cycle leads to centriole overduplication and formation of supernumerary centrosomes via consecutive rounds of centrosome reproduction, or concurrent formation of daughter centrioles around the existing centrioles [36,37]. The possibility of de novo centrosome assembly independent of pre-existing centrioles was first proposed by Khodjakov et al. who observed supernumerary centrosomes in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells following laser-mediated resection of existing centriole pairs [32]. Subsequently, this model of de novo assembly was also demonstrated in centrosome-depleted HeLa cells. In a recent study, Marteil et al. put forth centrosome over-elongation as a novel mechanism of numerical CA. They overexpressed centrosomal P4.1-associated protein (CPAP) in the human osteosarcoma cell line U2OS and observed a significant increase in centriole length. However, once maximum elongation was achieved, the centrioles started to shorten and increase in number, indicating fragmentation of these overlong centrioles that indirectly led to CA. Furthermore, CPAP overexpression restored centriole biogenesis after PLK4 inhibition, pointing to “ectopic procentriole formation” as yet another mechanism of CA [25].

Another bonafide cause of numerical amplification is cytokinesis failure, which generates polyploid cells with supernumerary centrosomes (Fig. 3B) [38,39]. The most frequent cause of cytokinesis failure is a defective spindle assembly checkpoint (SAC), which fails to stall mitosis at anaphase despite improper attachment of the chromosomes to the mitotic spindle. These cells then progress directly to the next G1 phase without cytokinesis, thereby generating twice the number of chromosomes. Although artificial induction of cytokinesis failure in cells lines does not always result in supernumerary centrosomes, high levels of Aurora-A in various tumor cells can override the SAC, indicating a possible link between centrosome over-duplication and tetraploidy [40,34]. Cell fusion is another mechanism through which the genetic material and centrosome number can be doubled. This form of CA is observed in ano-genital cancers, which are often caused by oncogenic virus-mediated cell fusion (Fig. 3D) [31]. Numerical amplification also arises from the fragmentation of the PCM, particularly during drug treatment and exposure to ionizing radiation [41–46]. Regardless of the mechanism, centriole duplication is driven by dysregulation of an array of PCM proteins, including pericentrin and γ-tubulin, in addition to PLK4, PLK1 and Aurora-A (Table 1). Numerically amplified centrosomes may appear as widely scattered supernumerary centrosomes in interphase (dispersed/scattered form) or as supernumerary centrosomes assembled together in interphase either individually distinguishable or clustered tightly (clustered form; Fig. 3A and C) [47,24,48,49,28].

Figure 3:

Representative confocal immunomicrographs of cells with dispersed or clustered amplified centrosomes due to cytokinesis failure or cell-cell fusion. A) Dispersed centrosomes (upper panel; widely dispersed). B) Cytokinesis failure. C) Clustered centrosomes (lower panel; individually distinguishable or tightly clustered). D) Cell-cell fusion configuration depicting supernumerary centrosomes in interphase. Centrosomes and microtubules were immunolabeled for γ-tubulin (green) and α-tubulin (red) respectively, and DNA was counterstained with Hoechst (blue). Scale bar (white line at the lower right of each panel) = 5 μm.

Table 1:

Table summarizing the genes/pathways and factors promoting CA and impact of CA on different cellular processes.

| Site of cancer | Genes/pathways/factors inducing CA | Cellular processes | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Breast | NEK6 and Hsp72 | Centrosome clustering | [113] |

| PLK4 | Invasion and migration by RAC1 | [89] | |

| Mutant p53 | Aberrant mitosis and a more aggressive disease course in vivo | [114] | |

| CEP135 | Multipolar mitosis and anaphase lagging chromosome | [115] | |

| USP9X via CEP131 | [116] | ||

| BRCA1/BARD1 along with OLA1 | Genomic integrity | [117] | |

| HER2 activation | CA induced oxidative stress leads to non-cell autonomous invasion | [118] | |

| PLK4 | Ploidy and CIN leads to de-differentiated cellular state | [12] | |

| HIF-1α | [48] | ||

| Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor (AhR) | [119] | ||

| Low Mol WT Cyclin E | [59] | ||

| CPAP-tubulin | Proliferation | [120] | |

| Invasion and migration | [30] | ||

| Cdk4 and Nek2 | [121] | ||

| Cdk2/ Cyclin A and Aurora-A | [122] | ||

| RACK1 induced CA via BRCA1 | [123] | ||

| Aneuploid tumors; associated with spindle abnormalities | [47] | ||

| Aneuploidy, microtubule nucleation capacity and loss of tissue differentiation | [28] | ||

| IQGAP1 via BRCA1 | Activation of stress and proliferation signals | [124] | |

| Melanoma | PLK4 | Cell proliferation | [125] |

| Ovary | Aurora-A | [126] | |

| KIFC1 | [127] | ||

| Cyclin E | [96] | ||

| WDR62 | [128] | ||

| Prostate | miR-129-3p via CP110 | Metastatic potential | [129] |

| SKA1 overexpression | Tumorigenesis | [130] | |

| Pericentrin overexpression | Spindle defects, genomic instability, and enhanced growth on soft agar | [131] | |

| Urothelial | Abnormal mitosis leading to CIN | [11] | |

| Cyclin E overexpression and loss of p53 | CIN | [86] | |

| Neural | p16 gene | [132] | |

| Cervical | HPV-16 E7 | Nuclear atypia and replication senescence | [133] |

| HPV-16 | Genetic instability | [134] | |

| Chlamydial infection | chromosome segregation errors | [135] | |

| HPV16 E7 | [136] | ||

| Lung | DNA damage | [44] | |

| WDR62 and TPX2 via Aurora-A activation | [137] | ||

| Colorectal | Negative regulation by Cyclin A2 | [138] | |

| KLF4 suppressed CA by negatively regulating the Cyclin E activity | [139] | ||

| Mutant or transcriptionally inactive β-catenin | [140] | ||

| Chromosome segregation errors | [85] | ||

| Pancreatic | Aphidicolin | Invasion and migratory capabilities | [29] |

| Head & Neck | Hypoxia -HIF-1α, miRNA-34a and Cyclin D1 | [141] | |

| BSTT | EVI1 overexpression | [39] | |

| Telomerase transcriptional Elements Interacting Factor modulation | [82] | ||

| Miscellaneous | Loss of KLF14 by upregulating PLK4 | [142] | |

| MdM2 Overexpression | [143] | ||

| Cyclin E overexpression | [79] | ||

| Mutant PIK3CA via AKT/ ROCK, CDK2/ Cyclin E-nucleophosmin pathway | [144] | ||

| PLK4 mediated phosphorylation of CEP131 | [145] | ||

| Loss of 14-3-3γ via Nucleophosmin | [146] | ||

| USP1 induced CA in part through ID-1 | [147] | ||

| CDK2 and CDK4 | [148] | ||

| PLK4 overexpression | [149] | ||

| CEP125 and KIFC1 | [150] | ||

| PLK4 | Aneuploidy and development of spontaneous tumors in multiple organs | [151] | |

| Kank1 depletion via RhoA hyperactivation | [152] | ||

| Epstein Barr Virus protein BNRF1 | CIN | [153] | |

| Liver Kinase B1 activation of PLK1 | Genomic stability | [154] | |

| Chloroquine inhibited etoposide inhibiting CDK2 and ERK activity | [155] | ||

| Mutant p53 | [156] | ||

| PIN 1 overexpression | CIN and tumorigenesis | [157] | |

| KAT2A/2B- mediated acetylation of PLK4 | [158] | ||

| PLK4 | [159] | ||

| Cyclin E, Cyclin A and mutant p53 | [160] |

CIN- chromosomal instability,

BSTT- bone and soft tissue tumor,

Miscellaneous- not studied in a specific tumor model

Structural amplification:

Structural defects in centrosomes can be induced by several events, including the accumulation of excessive PCM around the centrioles, which result in centrosomes that appear altered in size (Fig. 4) [50,51]. The PCM content is regulated by centrioles, free cytoplasmic α and β-tubulin, centrobin, various kinases (i.e., PLK1 and CHK1), and several coiled-coil proteins such as pericentrin and CPAP [52–54]. Thus, dysregulation in the expression of these proteins or alterations in their posttranslational modifications can lead to PCM accumulation. Although several stimulators of PCM assembly (e.g., PLK1 and CHK1) are overexpressed in cancer cells, for, the precise mechanism underlying structural CA remains poorly defined. Cancer cells often harbor supernumerary centrioles that usually recruit excessive PCM, which further expands following DNA damage. Structural defects in centrioles have emerged as another possible cause of structural CA; however, the analysis of centriole structure is challenging due to their minute size and requires highly sophisticated microscopy techniques, especially for detecting structural defects in tumor samples. Recent studies have reported that the length of human centrioles in most cell types is typically 450–500 nm, and is primarily controlled by CP110, a protein that caps the distal ends of centrioles and the loss of which results in overly long centrioles [55]. In addition, the cell cycle-regulated CPAP controls microtubule growth during centriole assembly by directly binding to β-tubulin, and CPAP overexpression in actively cycling human cells results in overly long centrioles and multipolar mitotic spindles [55–57]. A recent study utilizing ultrastructural microscopy showed that over-enlongation of centrioles increased the number of both normal-length centrioles with barrel structure, and multiple fragmented centrioles with unstable structure [25].

Figure 4:

Representative confocal immunomicrographs of cells showing PCM accumulation in both normal and cancer cells. Normal and cancer cells were immunostained for centrin-2 (red), and γ-tubulin (green), and DNA was counterstained with Hoechst (blue). Scale bar (white line at the lower right of each panel) = 5 μm.

Another important factor that deregulates the expression of the several centrosome-associated genes is the tumor microenvironment, especially hypoxia[58]. Studies from our lab have shown that established cancer cell lines exhibited considerably lower CA compared with their parental tissue counterparts in breast, pancreatic, and bladder cancer. To the best of our knowledge, we are the first to report this discrepancy between in vivo and in vitro CA and to pinpoint a tumor microenvironment-related factor that is absent in the in vitro culture system and is responsible for CA in the tumor tissues. Several studies have reported that hypoxia upregulates CA associated proteins such as Aurora-A/STK15 and PLK4. In line with these findings, we observed that exposing triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) cell lines to hypoxic conditions or overexpressing hypoxia inducible factor 1 alpha (HIF-1α) increased the frequency of CA by 1.5-fold. Conversely, exposing HIF-1α knockout cells to hypoxic conditions significantly decreased CA via regulating the expression of PLK4. Therefore, hypoxia seems to be a crucial factor promoting CA in tumor tissues. Our data emphasize that in vitro culture models primarily deploying normoxic conditions do not recapitulate the tumors’ physiological condition and results obtained from such models should be interpreted with caution [48].

How do cancer cells with a centrosomal overload survive?

A strong association between numerical CA and aberrantly high levels of centrosome-associated proteins has been observed in cancers. Furthermore, the frequency of CA often increases during tumors progression and metastasis[59–63,30]. These observations indicate that CA may endow cancer cells with a survival advantage that promotes tumor growth and progression. There are several mechanisms by which cancer cells haul this centrosomal overload to accomplish cell division and gain a growth advantage over normal cells. In most cell types, the multiple centrosomes are localized as a distinct cluster next to the nucleus during interphase. As the cell enters prophase, these centrosomes start scattering across the nuclear material. During prometaphase transition and with the loss of nuclear membrane, centrosomes form multipolar spindles with multiple MTOCs at each spindle pole (Fig. 1 cancer cell). The formation of multipolar mitotic spindles results in chromosome missegregation and CIN, which often precedes malignant transformation and is the primary cause of heterogeneity among tumor cells. However, Ganem et al. showed that multipolar mitosis caused extensive aneuploidy in daughter cells, which eventually underwent apoptosis.[64]. To circumvent this self-destruction, cancer cells employ “clever” mechanisms that allow them to cluster their multiple centrosomes to form a pseudo-bipolar spindle in metaphase (Fig. 1) segregating the chromosomes in two viable daughter cells. During this division process, the centrosomes stay clustered at the two spindle poles [65–68]. The nonessential kinesin motor protein KIFC1 (also known as HSET) is a crucial player in the clustering of centrosomes in cancer cells [69,70]. KIFC1 knockdown induces multipolar spindle defects and cell death in mitotic cancer cell lines containing extra centrosomes (eg. MDA-MB 231) [70]. In contrast, KIFC1 silencing has no effect on cell division in near-normal cell lines that exhibit no CA (e.g., BJ fibroblasts), or low levels of CA (e.g., mouse NIH-3T3 fibroblasts and human breast MCF-7 cells) [70]. KIFC1 expression is elevated in several cancer types [27,71–73], including breast, ovarian, and colon cancer [74]. Seemingly, in cancer cells, the role of KIFC1 is indispensable due to the presence of supernumerary centrosomes. This differential dependence of cancer cells on KIFC1 for viability makes KIFC1 the Achilles’ heel of cancer cells, and fortuitously, a therapeutic target for “centrosome-rich” cancers, including those of the breast, prostate, bladder, colon, and brain. Studies also underscore the overexpression of KIFC1 in breast and prostate cancers resistant to tubulin-targeting drugs, including docetaxel, and taxane[75,76]. Interestingly, KIFC1 inhibition increases the sensitivity of cancer cells to taxanes [77].

Centrosome clustering increases the attachment of a single kinetochore to microtubules emanating from both the spindle poles, also known as merotely [78]. Merotelic kinetochore attachment leads to chromosome segregation maintaining cell viability while introducing aneuploidy and chromosomal breakages. Supernumerary centrosomes create a “multipolar mayhem” that culminates in a spindle configuration increasing the number of “lagging” chromosomes during anaphase and leading to chromosome breakage during cytokinesis. Marteil et al. showed that forced elongation of centrioles via CPAP overexpression also increases multipolar mitoses, chromosome missegregation during anaphase and telophase, and chromosome lagging in several cancer cell lines [25]. These effects are either a direct result of asymmetric kinetochore capturing by the longer centrioles, or an indirect consequence of increased centriole numbers. The presence of extra centrosomes is strongly associated with defective spindle formation, CIN, aneuploidy, telomere shortening, chromosome breakage, and abnormal karyotypes in various human cancers including colorectal cancer, renal cell carcinoma tumors, head and neck carcinoma, lung adenocarcinoma, osteosarcoma, liposarcoma and leiomyosarcoma[79–84] (Table 1). These “centrosome-rich” tumors display complex karyotypes, anaphase bridges, and telomere dysfunction [85–88,83].

Beyond the mitotic spindle, the centrosome is the control center of cell polarity and morphology, intracellular trafficking and cell signaling [8,9]. Epithelial cells that undergo malignant transformation often have skewed polarity, and epithelial-mesenchymal transition facilitates cancer cell metastasis. Both numerical and structural amplification can result in “super centrosomes” with high microtubule nucleation capacity, causing the formation of dense microtubular arrays that promote cell polarization during directional migration. There is mounting evidence of an aneuploidy-independent, direct relationship between CA and tumor cell invasiveness indicating a purely mechanical role of centrosomes in enhancing tumor malignancy [89].

Can amplified centrosomes serve as prognostic and/or predictive biomarkers in human cancers?

The ubiquitous presence of supernumerary centrosomes in tumor tissues has established CA as one of the hallmarks of cancer. Over a century ago, Theodor Boveri postulated that the presence of multiple centrosomes in cells might lead to tumorigenesis. Since then, centrosomes have been studied in numerous human cancers, including bladder, blood, bone and soft tissue, brain, breast, cervix, colorectal, head and neck, hepatobiliary tract, kidney, ovary, prostate, and hematological malignancies. The ability of CA to drive tumorigenesis has remained a long-standing debate for many years. A landmark study by Basto. et.al., demonstrated that induction of CA could initiate tumor formation and metastasis in flies [90], suggesting that supernumerary centrosomes are not merely bystanders but rather drivers of tumor development and progression. Several studies have shown that CA occurs in precancerous and preinvasive lesions, indicating that it is an early event in tumorigenesis and likely involved in tumor progression from early to advanced stages [91–95]. Numerous studies have also shown that CA is associated with high-grade tumors and poor prognosis [30,12,87,96,60,11]. CA has been implicated in the development of colorectal adenoma and its progression to adenocarcinoma, and is associated with higher invasiveness and histological grade of colorectal cancer [92]. The progression of hepato-biliary cancers has also been linked to CA, with advanced stages of liver, bile duct and gall bladder carcinomas exhibiting higher degrees of centrosomal abnormalities than their early-stage counterparts [97]. HPV+ cervical carcinoma also frequently displays CA, wherein it is correlated with increased CIN, dysplasia, and higher invasiveness [10,98]. Similarly, a higher CA load has been observed in the histologically aggressive serous-type ovarian adenocarcinoma than in endometroid-type ovarian cancer [93,96]. Furthermore, the frequency of CA is higher in advanced and metastatic prostate tumors than in localized and less aggressive prostate neoplasms [10,91,99]. High grade gliomas, glioblastomas, and astrocytomas also exhibit higher CA compared with low-grade tumors [60]. Interestingly, CA is concentrated in the aneuploid vascular endothelial cells of glioblastomas, suggesting a role in tumor angiogenesis [100]. High levels of CA have been reported in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas, wherein CA correlates with tumor size and stage, distant metastasis, recurrence, and poor overall survival [101,102,62]. The degree of CA is also associated with osteosarcoma metastasis and recurrence [103,104]. Abnormal centrosomes are frequently observed in B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas (NHL), including follicular lymphoma (FL), diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), and Burkitt’s lymphoma [105,106]. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia is predisposed to structural CA, strongly associated with disease aggressiveness, higher histological grade and tetraploidy [107,108]. Structural CA has also been observed in multiple myeloma, and the proportion of plasma cells harboring extra centrosomes increases with disease progression [94]. Furthermore, the frequency of CA is higher during blast crisis and bone marrow failure compared to the chronic phase, with AML blasts displaying extensive numerical and structural CA, especially in cytogenetically high-risk groups [109]. These studies are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2:

Table summarizing the prognostic role of centrosome amplification in multiple malignancies (CA quantitated in clinical tissue samples).

| Site of Cancer | CA | CA associated genes/ proteins | Correlation with | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast | No | Low Mol WT Cyclin E | Nuclear grade | [59] |

| Yes | Higher in TNBCs; metastatic disease and PFS | [30] | ||

| No | Nek9 | Tumor size, grade, OS, DFMS | [161] | |

| Yes | Tumor (i) subtype (TNBC); (ii) grade; (iii) stage; OS and RFS | [12] | ||

| Yes | Tumor grade | [28] | ||

| Yes | Tissue differentiation | [95] | ||

| Yes | (i) Nodal tumor involvement (ii) Negative hormone receptors | [162] | ||

| Yes | Tumor grade | [163] | ||

| Yes | Nodal metastasis | [47] | ||

| Yes | Tumor grade | [164] | ||

| No association with clinicopathological parameters | [13] | |||

| Yes | Local recurrence | [111] | ||

| Ovary | Yes | Tumor grade and histologic subtype | [93] | |

| Yes | Tumor grade | [96] | ||

| No | Aurora-A | OS | [126] | |

| Urothelial | Yes | Tumor grade | [11] | |

| Yes | Tumor grade | [87] | ||

| Yes | RFS, PFS | [63] | ||

| Yes | Cyclin E | Tumor grade | [86] | |

| Yes | Tumor grade, stage, distant metastasis | [88] | ||

| No | PLK1 | Tumor grade; multiple tumors and positive urine cytology | [165] | |

| No | BUBR1 (mitotic checkpoint protein) | Tumor grade, stage, size, number of tumors and, positive urine cytology | [166] | |

| Yes | RFS | [167] | ||

| Yes | PFS; disease progression and recurrence | [168] | ||

| Adrenal | Yes | Carcinoma | [169] | |

| Neural | Yes | Ploidy status | [170] | |

| No | γ tubulin, Aurora-A | Tumor grade | [60] | |

| Lung | No | Cyclin E | Tumor stage | [79] |

| No association with clinicopathological parameters | [80] | |||

| Colorectal | Yes | Aneuploid tumors | [85] | |

| Yes | Tumor grade | [92] | ||

| Yes | Tumor grade | [171] | ||

| Cervical | Yes | Tumor grade | [98] | |

| Pancreatic | No | CDK1, PIM1, NEK2, PLK4, STIL | OS | [29] |

| Hepato-biliary | Yes | Tumor stage | [97] | |

| Yes | Non diploid tumors | [172] | ||

| Head & Neck | Yes | Tumor recurrence | [102] | |

| No | Aurora-A | Tumor stage, regional lymph node and, distant metastasis | [61] | |

| Yes | Poorly differentiated SCCs | [173] | ||

| Yes | Histological cytologic grade | [101] | ||

| Yes | OS | [141] | ||

| Yes | T category; tumor stage; distant metastasis; DFS and OS | [62] | ||

| Prostate | Yes | Tumor grade and stage | [99] | |

| Yes | Tumor grade | [91] | ||

| BSTT | Yes | Tumor grade | [82] | |

| Yes | Tumor grade | [104] | ||

| Yes | Disease recurrence | [103] |

BSTT- bone and soft tissue tumors,

OS-overall survial,

PFS-progression free survival,

DMFS- distant metastasis free survival,

DFS- disease free survival.

Voluminous evidence posits CA as a potential prognostic and predictive cancer biomarker. However, the lack of quantitative approaches to evaluate CA and systematic and robust validation studies has hindered the clinical implementation of CA as a biomarker. The development of robust CA quantitation methods is a prerequisite to perform such rigorous studies and may facilitate the implementation of CA as a prognostic or predictive biomarker in a clinical setting. The following sections outline the shortcomings in current practice and trace the development of a novel and robust technology to overcome these limitations.

Can we accurately quantify centrosome amplification in clinical tissue specimens?

The aforementioned studies provided at best a semi-quantitative assessment of centrosomal aberrations in tumors, which limit their prognostic utility. Although the extent of CA in tumor samples can be gleaned by simple immunohistochemical methods, which are clinically adaptable and cost-effective, these techniques suffer from serious limitations. Most researchers consider numerical amplification as a measure of CA, and visualize centrosomes by labeling centriolar (e.g., centrin) and PCM (e.g., pericentrin and γ-tubulin) proteins. The evaluation of structural amplification requires the measurement ofthe centriolar length γ-tubulin spots. While a centriolar marker can fairly estimate structural CA, in terms of increased volume and length of the centrioles, high levels of PCM proteins can also result from increased PCM (a structural anomaly). Therefore, the distinction between numerical and structural amplification remains ambiguous (Table 3). Centrin is considered a bonafide marker of both centriole length and number since it localizes to the distal ends of the centrioles. Nonetheless, centrin is also present in centriolar satellites and the long cilia-like structures often seen in cancer cells, which can result in false positives. Recently, Marteil et al. screened the NCI-60 cancer cell line panel using both centrin and the centriole elongation factor CP110 and developed an algorithm to measure the centriole length in a three-dimensional manner. This bi-marker combination detected substantial centriole over-elongation in 22 of the 60 cell lines, especially those of breast, lung and skin cancers, and was validated in a small number of estrogen receptor (ER)-positive and negative breast carcinoma tissues [25]. Thus, the quantification of structural amplification has been mostly limited to cell lines, and limited data is available regarding the correlation between clinicopathological factors (i.e., tumor grade, stage, outcome) and structural CA in tumor tissues. From a clinical perspective, different tumor types require different centriole over-elongation cut-offs for the use of structural CA as a prognostic marker. In addition, multiple centrioles frequently occur in ciliated epithelial cells, and may incorrectly be interpreted as CA in neoplasms arising from the mucosal epithelium. Finally, none of the studies have made a clear distinction between the contribution of structural and numerical amplification towards cancer progression. Thus, a true systematic quantitation technique that includes both structural and numerical amplification is urgently needed as a foundation for centrosome-based risk assessment in clinical tissue samples.

Table 3:

Table summarizing the methods of quantitation of CA in multiple studies.

| Biomarker / Staining | Type of CA | Method of quantitation | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pericentrin | N | M, ≥3/cell | [174] |

| N | M, ≥3/cell | [168] | |

| N & S | IP software (version 3.5, Scanalytics), (i) number >2/cell; (ii) diameter (> 2x of centrosomes of non-tumor control cells); (iii) organized in patchy aggregates >3μm in length. | [172] | |

| N | M, ≥3/cell | [11] | |

| N & S | Image Pro Analysis Software, (i) >2/cell; (ii) size (diameter >2x larger) | [59] | |

| N & S | Adobe Photoshop, (i) >2/cell; (ii) diameter >2x size of control | [131] | |

| γ-tubulin | N & S | Zen Imaging Software, >2/cell and volume >0.76μm3 | [48] |

| N & S | CytoVision® 2.7 System, >3/cell or diameter >2x the diameter of normal centrosomes | [175] | |

| N & S | Adobe Photoshop, (i) >2/cell; (ii) greatest/smallest diameter >2 (iii) diameter >2x the diameter of the centrosomes present in normal epithelium | [91] | |

| N | M, >2/cell | [98] | |

| N | M, >2/cell | [169] | |

| N | M, ≥3 punctate, dot-like immunoreactive signals, and/or robust diffuse staining, in the cytoplasm of individual tumor cells | [100] | |

| N | M, >2/cell | [132] | |

| N | M, ≥3 punctate, dot-like immunoreactive signals, and/or robust diffuse staining, in the cytoplasm of individual tumor cells | [176] | |

| N & S | M, ≥3/cell and size (diameter ≥2μm) | [177] | |

| N & S | WinROOF Software, ≥3/cell and size (>1.27μm) | [13] | |

| N & S | IMARIS Imaging Software, >2/cell and size (volume>0.74 μm3) | ||

| N & S | Vysis Quips SmartCapture, >2/cell; size and shape (different from centrosomes of control cells) | [178] | |

| N | Metamorph Image Software, ≥3/cell | [179] | |

| N | N/A, >2/cell | [102] | |

| N & S | N/A, >2/cell or size (>2x of centrosomes in control cells) | [61] | |

| N | M, ≥3/cell | [165] | |

| N | M, ≥3/cell | [166] | |

| N & S | DIAS Software, (i)>0.878/cell; (ii) size (structural entropy of γ-tubulin signals) | [92] | |

| N & S | OpenLab Imaging Software >2/cell and size (>0.012 μm3) | [87] | |

| N & S | Zen Imaging Software, >2/cell and size (volume >0.56 μm3) | [29] | |

| N | M, >2/cell | [128] | |

| N & S | Zen Imaging Software, >2/cell and volume >0.76μm3 | [30] | |

| N & S | Zen Imaging Software, >2/cell and volume >0.7μm3 | [141] | |

| N & S | Leica Q-FISH software, >2/cell or diameter >2x of centrosomes in control cells | [95] | |

| N | M, >2/cell | [143] | |

| N | M, >2/cell | [126] | |

| N | M, ≥3/cell | [63] | |

| N & S | Adobe Photoshop, (i) number (>2/cell); (ii) diameter (>2x of control) | [91] | |

| N & S | DIAS Software, >2/cell or size (>2x centrosomes in control cells) | [61] | |

| N & S | SAMBA 2005 image analysis system, >2/cell or size (>2x of centrosomes in control cells) | [62] | |

| N & S | Adobe Photoshop, (i) >2/cell; (ii) diameter (>2x of centrosomes in control); (iii) organized in patchy aggregates or elongated in string like structure greater than 3μm in length. | [80] | |

| γ- tubulin, pericentrin, CPAP, Cep152, centrin- 3 | N | M, >2/cell Fiji/ImageJ & Photoshop |

[120] |

| γ-tubulin, β-tubulin | N | M, >2/cell | [170] |

| N | M, >2/cell | [180] | |

| N & S | M, >2/cell and size (>2 centrioles) | [83] | |

| Centrin, pericentrin, γ-tubulin | N & S | M, (i) number (>1.55/cell); (ii) volume (>0.023 μm3) | [28] |

| N | M, >4 centrioles | [181] | |

| γ-tubulin, pericentrin | N | M, >2/cell | [157] |

| N & S | M, >2/cell or size | [173] | |

| N | M, >2/cell; size (punctuate pattern of centrosome enlargement) | [103] | |

| N & S | M, >2/cell or size (diameter >2x centrosomes) | [162] | |

| N & S | M, Centrosome number (>2/cell), size >2μm, or abnormal in shape | [182] | |

| N & S | M, (i) >3/cell; (ii) diameter (>2x centrosomes of control cells); (iii) organized in patchy aggregates greater than 3μm in length | [97] | |

| N | Zeiss LSM Image Browser, >1.01/cell | [99] | |

| γ-tubulin, α-tubulin | N | Zen Software, >2/cell | [127] |

| N & S | M, >2/cell and organization in patchy aggregates (diameter ≥2μm) | [96] | |

| N | M, >2/cell | [82] | |

| Pericentrin, α-tubulin | N | N/A, ≥3/cell | [121] |

| N & S | M, >2/cell; diameter >2x of control Adobe Photoshop | [10] | |

| γ-tubulin, Cyclin E, E2F1, p53 | N & S | N/A, >2/cell or size (greater diameter and elongated shape) | [79] |

| p16(INK4a), p53, and pRb | N & S | M, (i) number (>2/cell); (ii) diameter (>2x centrosomes in normal epithelium); (iii) organized in patchy aggregates or elongated in string like structure greater than 3μm in length. | [80] |

| Pericentrin and polyglutamylated tubulin | N & S | M, >2/cell and size (>0.99μm) | [12] |

| γ-tubulin, AhR | N | M, >2/cell | [119] |

| Centrin, γ-tubulin | S | Analyze Image Processing Program, (1) mean volume (μm3) (i) normal (0.013) (ii) tumor (0.114) (2) Volume per cell (μm3) (i) Normal (0.011) (ii) tumor (0.492) | [163] |

| N | Adobe Photoshop & ImageJ, >4 centrioles/cell | [156] | |

| MIB-1 antibody against Ki-67 | N | Analyze Image Processing Program, Centrioles (>2/cell) | [164] |

| γ-tubulin, α-tubulin, SAS-6 | N | M, Centrioles (>2/cell) | [123] |

| Centrin, pericentrin | N | NIS-Elements AR microscope imaging software; >4 centrin foci | [183] |

| N & S | Metamorph TM Software, >4 centrioles per cell and volume (>0.075μm3) | [47] | |

| Cyclin E, Cyclin A, γ-tubulin | N & S | M, >2/cell or size (diameter >2x centrosomes in control cells) | [95] |

| STK15 | N & S | N/A, >2/cell or size (diameter >2x centrosomes in control cells) | [184] |

| STK15, centrin, pericentrin | N | M, >2/ cell | [185] |

| γ-tubulin, p53, Cyclin E | N | M, ≥3/cell | [86] |

| MLH1, p53, Aurora-A, MSH2 | N | M, ≥3/cell | [165] |

| α, β and γ-tubulin | N & S | MicroMeasure v3.3 Software, ≥3/cell and size (diameter ≥2μm) | [186] |

| Centrins 1 & 2, γ-tubulin, hNinein, Aurora-A, and Aurora-B | N | M, Centriole number per centrosome (>2) | [60] |

| WDR62, y-tubulin | N | M, ≥3/cell | [137] |

| γ-tubulin, β-tubulin | N | M, >2/cell | [143] |

| γ-tubulin, Cep170 | N | M, >2/cell, at least 2 of them positive for Cep170 | [187] |

| γ-tubulin, Cep135 | N | Adode Photoshop, ImageJ, Fiji, >2 CEP135 & γ-tubulin foci | [112] |

N-numerical amplification,

S- structural amplification,

M- manual.

Tracing the development of Centrosome Amplification Score (CAS) technology

Our research group has developed a novel, semi-automated technology to rigorously quantify numerical and structural amplification of centrosomes in tumor samples. Broadly, the technology entails the digital analysis of fluorescence confocal microscopy images to yield a CAS. Our analytical pipeline allows for a robust investigation of the ability of centrosomal overload to predict the risk associated with cancer progression.

During the initial development stage, the pipeline was validated in TNBC and non-TNBC tissues. Fluorochrome-labeled antibodies were used to detect γ-tubulin, with the presence of more than two fluorescent spots indicating numerical CA. The number of cells displaying supernumerary chromosomes was almost two times higher in TNBC tissues than in non-TNBC tissues. For example, to evaluate structural amplification, we measured the volume of γ-tubulin spots from stacked raw confocal images, using a 3D volume rendering software. Based on these metrics, we observed that approximately 68% of cells in TNBC samples and 45% in non-TNBC samples exhibited CA. The above results were further confirmed by measuring additional parameters indicative of CA, such as high expression of PLK4, vimentin and Aurora-A. In TNBC tissues, higher in situ levels of these proteins were observed [30]. The findings strongly suggest that CA is prevalent in breast tumors in general, and more pronounced in histologically aggressive TNBC. Thus, CA can be of great clinical value in the early diagnosis of breast cancer, prediction of metastasis risk, and discrimination fatal tumors from less aggressive ones.

Similarly, we used the above approach to quantify CA in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) tissues. Extra centrosomes were detected in 25–30% of the cells in PDAC tissues compared to only 5% in the adjacent normal epithelial tissues. The maximum centrosomal volume in normal pancreatic tissues was 0.56 μm3, whereas the maximum centrosome volume in PDAC tissues was considerably increased to an average of 1.75 μm3. The severity of CA was associated with tumor differentiation and duodenal metastasis [29]. These data further highlighted CA monitoring as a reliable, economical, non-invasive, and sensitive predictive biomarker for cancer. The above studies paved the way and provided a testbed for further development and fine-tuning of the technology. The current, more advanced version of the CAS technology involves the digital analysis of fluorescent confocal microscopy images using IMARIS Biplane 8.2 3D volume rendering software, to evaluate the centrosome numbers and volume. The composite CAS was computed based on the formula: CAStotal =CASi + CASm, where CASi and CASm are scores that describe numerical and structural CA phenotypes [110], which was applied to analyze centrosome aberrations in samples from different stages of breast cancer (Fig. 5A–C); normal epithelial breast tissue (n=54) from patients who underwent mammoplasty surgery, cancer-adjacent apparently normal terminal duct lobular units (TDLU) (n=94), ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) tissues from a discovery set (n=133), and invasive tumor from the mixed DCIS cohort (n=64). Interestingly, we observed that the CAS score increased significantly with disease progression, with normal samples exhibiting the lowest CAS values followed by the adjacent normal and DCIS, and finally invasive tumors showing the highest CAS values. These findings strongly indicate that CA has a critical role in tumor progression.

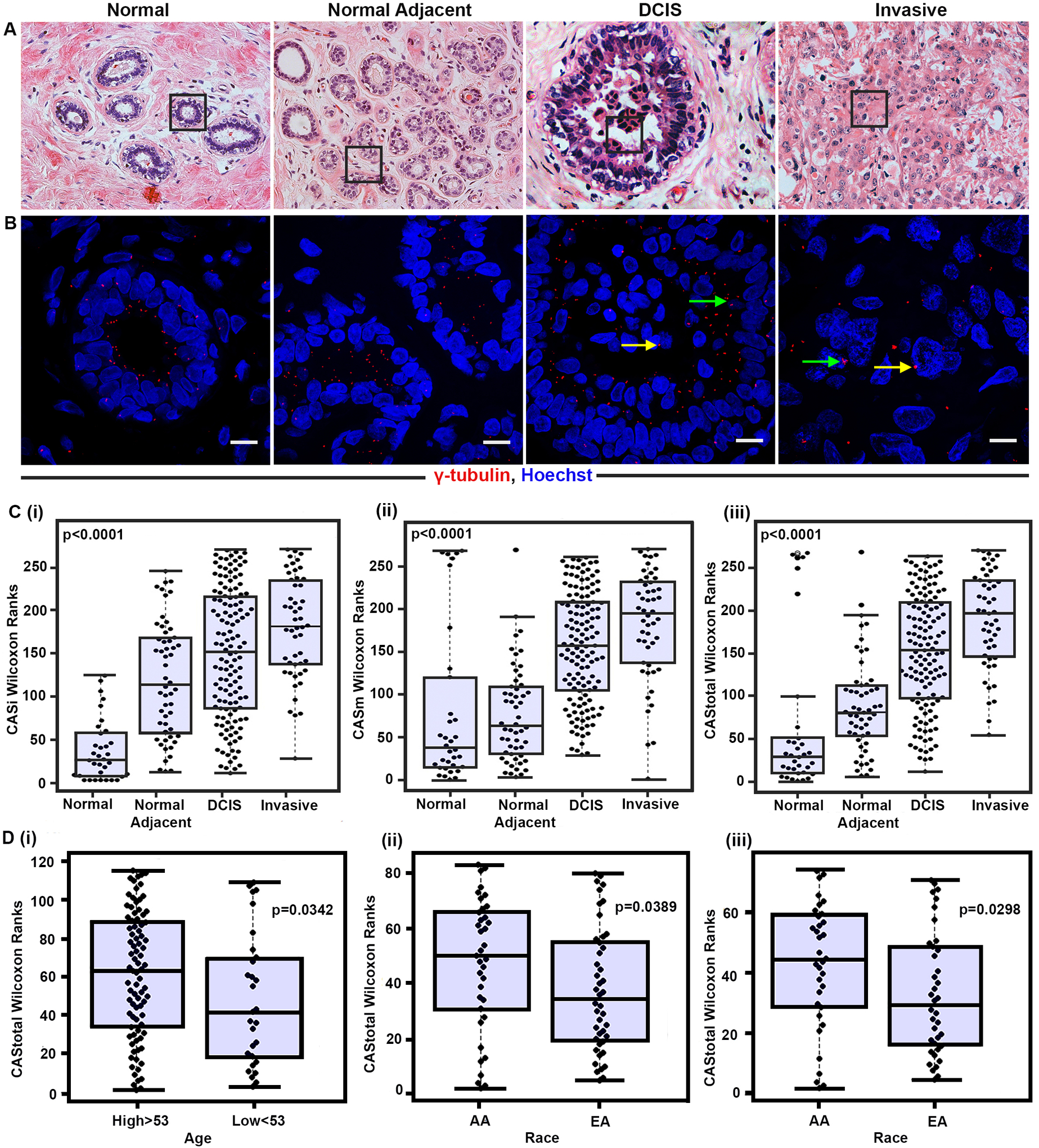

Figure 5:

A) Representative H&E images of normal (n=54), normal adjacent (n=94), pure DCIS (n=133), and invasive (n=64) breast tissue sections (20× magnification). B) Confocal micrographs showing numerical and structural CA. DCIS tissue sections were immunostained for centrosomes (γ-tubulin, red) and counterstained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar (white) = 20 μm. (C) Representative Beeswarm Box plots for (i) CASi, (ii) CASm and (iii) CAStotal in all four groups. (D) Representative Beeswarm Box plots for CAtotal in prostate cancer patients stratified into the i) high and low age groups, ii) African American (AA) and European American (EA) patients with BMI >25, and iii) high grade (Gleason grade >7) AA and EA patients.

Furthermore, we quantified CAS in DCIS tissue sections and observed that higher CAS was associated with a greater risk of recurrence and poor recurrence-free survival (RFS) after adjusting for confounding factors. Moreover, CAS provided a significantly better predictive performance than the Van Nuys Prognostic Index (VNPI) in terms of stratifying patients into recurrence and recurrence-free groups. These exciting results strongly support the use of CAS as a prognostic biomarker that can identify high-risk patients for personalized therapies [111]. Our unpublished data from a study on prostate cancer (n=115) showed that CAS was associated with older age. In addition, the tissue samples from African American patients exhibited higher CAS compared to samples from European Americans with body mass index (BMI) >25 and high-grade tumors (Fig. 5D). These findings further bolster the association of CA with clinicopathological parameters associated with an aggressive phenotype in prostate cancer.

The road ahead

CA is an established hallmark of cancer, and as such, amplified centrosomes have emerged as valuable prognosticators in various cancer types. However, there are no imminent studies aimed at bringing CA within the folds of clinical practice to evaluate prognosis and predict tumor recurrence. The major bottleneck in translating the predictive utility of CA to clinical applications is the lack of a reliable and accurate method to quantify centrosomes in tissue samples, which can be obviated using CAS technology. Furthermore, CAS-based diagnosis can be successfully implemented only with the development of an automated platform for high throughput quantitative analysis. The latter can be challenging due to differences in centrosome length and the size of centrosome foci across different cells and tissue types. Another technical concern is the impact of tissue section thickness on the centrosome number and volume. In a recent study, Wang et al. reported significant centrosome loss in 4 to 5 μm thick breast and prostate tissues, with 30–60% of the cells showing less than two centrosomes while overlapping layers in thicker sections prevented accurate quantification. Therefore, the optimum tissue section thickness should be standardized based on the volume of the resident cell types to avoid both false negative and false positive findings. Well-controlled studies are warranted to validate the quantification methodology that encompasses the severity and magnitude of both numeral and structural aspects of amplification. Once validated, the novel quantification platform can be customized/tailored (tissue thickness, tissue processing, normal centrosome volumes to be optimized/calibrated cancer-wise) to reproducibly measure CA. The development of an easily interpretable and robust CAS classifier (low vs. high risk) may aid clinical decision making. The advent of these organelle-based prognostic and predictive approaches creates an array of possibilities for combination with gene-based signatures, tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte profiling, and with other clinicopathological markers, which would enable a more precise risk stratification. The development of centrosome-based risk prediction strategies also opens up treatment avenues for high CAS patients, who may benefit from centrosome-based therapies. Undeniably, the above mentioned studies will bring much-needed attention to these “minuscule” organelles, and perhaps lead to their inclusion in the armamentarium of clinical biomarkers associated with tumor aggressiveness and metastasis.

In addition, the CAS-based method can greatly assist in studying CA during tumor progression, and rapidly screen for patients at high risk of clinically aggressive cancers. The evolution of centrosome abnormalities during cancer initiation and progression and the predominance of CA in the different tumor stages may also be accurately detected using the CAS technology. Future efforts are required to validate the CAS in larger patient cohorts of various cancer types. Wang et al. recently quantified centrosomes in different human tissue samples at the single-cell level using antibodies against multiple centriolar and PCM proteins, along with antibodies targeting junction proteins (e.g., E-cadherin and integrins) to demarcate cell borders [112]. Combining CAS with this approach to accurately determine CA in individual cells in tissue samples, can help discern intra- and inter-tumor heterogeneity. Furthermore, studies are warranted to evaluate the relationship between CA (and different tumor microenvironment components and characteristics, as this may enhance the prognostic performance of CA. Given the recently established role of the tumor microenvironment in driving CA, decoupling the specific molecular alterations associated with centrosome aberrations may unfold novel mechanistic correlations. Future studies should take on a holistic approach to understanding the molecular circuitry regulating centrosome biology.

Funding:

This study was supported by a grant from the National Cancer Institute (U01 CA179671) to RA.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of a an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethics approval: NA

Consent to participate: NA

Consent for publication: NA

Availability of data and material: NA

Code availability NA

REFERENCES

- 1.Hamoir G (1992). The discovery of meiosis by E. Van Beneden, a breakthrough in the morphological phase of heredity. Int J Dev Biol, 36(1), 9–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Beneden E NA (1887). Nouvelle recherches sur la fécondation et la division mitosique chez l’Ascaride mégalocéphale. . Bull. Acad. Royale Belgique 3éme sér, 14, 215–295. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scheer U (2014). Historical roots of centrosome research: discovery of Boveri’s microscope slides in Wurzburg. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci, 369(1650), doi: 10.1098/rstb.2013.0469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang EC, Schwarz RA, Lang AK, Bass N, Badaoui H, Vohra IS, et al. (2018). In Vivo Multimodal Optical Imaging: Improved Detection of Oral Dysplasia in Low-Risk Oral Mucosal Lesions. Cancer Prev Res (Phila), 11(8), 465–476, doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-18-0032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boveri T (1887). Ueber den Antheil des Spermatozoon an der Theilung des Eies: s.n.].

- 6.Salisbury JL (2004). Centrosomes: Sfi1p and centrin unravel a structural riddle. Curr Biol, 14(1), R27–29, doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2003.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doxsey SJ, Stein P, Evans L, Calarco PD, & Kirschner M (1994). Pericentrin, a highly conserved centrosome protein involved in microtubule organization. Cell, 76(4), 639–650, doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90504-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kirschner M, & Mitchison T (1986). Beyond self-assembly: from microtubules to morphogenesis. Cell, 45(3), 329–342, doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90318-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hinchcliffe EH, Miller FJ, Cham M, Khodjakov A, & Sluder G (2001). Requirement of a centrosomal activity for cell cycle progression through G1 into S phase. Science, 291(5508), 1547–1550, doi: 10.1126/science.1056866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pihan GA, Purohit A, Wallace J, Knecht H, Woda B, Quesenberry P, et al. (1998). Centrosome defects and genetic instability in malignant tumors. Cancer Res, 58(17), 3974–3985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kawamura K, Moriyama M, Shiba N, Ozaki M, Tanaka T, Nojima T, et al. (2003). Centrosome hyperamplification and chromosomal instability in bladder cancer. Eur Urol, 43(5), 505–515, doi: 10.1016/s0302-2838(03)00056-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Denu RA, Zasadil LM, Kanugh C, Laffin J, Weaver BA, & Burkard ME (2016). Centrosome amplification induces high grade features and is prognostic of worse outcomes in breast cancer. BMC Cancer, 16, 47, doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2083-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shimomura A, Miyoshi Y, Taguchi T, Tamaki Y, & Noguchi S (2009). Association of loss of BRCA1 expression with centrosome aberration in human breast cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol, 135(3), 421–430, doi: 10.1007/s00432-008-0472-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giehl M, Fabarius A, Frank O, Hochhaus A, Hafner M, Hehlmann R, et al. (2005). Centrosome aberrations in chronic myeloid leukemia correlate with stage of disease and chromosomal instability. Leukemia, 19(7), 1192–1197, doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holland AJ, Lan W, & Cleveland DW (2010). Centriole duplication: A lesson in self-control. Cell Cycle, 9(14), 2731–2736, doi: 10.4161/cc.9.14.12184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Loncarek J, & Khodjakov A (2009). Ab ovo or de novo? Mechanisms of centriole duplication. Mol Cells, 27(2), 135–142, doi: 10.1007/s10059-009-0017-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsou MF, & Stearns T (2006). Mechanism limiting centrosome duplication to once per cell cycle. Nature, 442(7105), 947–951, doi: 10.1038/nature04985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vader G, & Lens SM (2008). The Aurora kinase family in cell division and cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta, 1786(1), 60–72, doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cizmecioglu O, Arnold M, Bahtz R, Settele F, Ehret L, Haselmann-Weiss U, et al. (2010). Cep152 acts as a scaffold for recruitment of Plk4 and CPAP to the centrosome. J Cell Biol, 191(4), 731–739, doi: 10.1083/jcb.201007107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Habedanck R, Stierhof YD, Wilkinson CJ, & Nigg EA (2005). The Polo kinase Plk4 functions in centriole duplication. Nat Cell Biol, 7(11), 1140–1146, doi: 10.1038/ncb1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Loffler H, Fechter A, Matuszewska M, Saffrich R, Mistrik M, Marhold J, et al. (2011). Cep63 recruits Cdk1 to the centrosome: implications for regulation of mitotic entry, centrosome amplification, and genome maintenance. Cancer Res, 71(6), 2129–2139, doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stearns T, Evans L, & Kirschner M (1991). Gamma-tubulin is a highly conserved component of the centrosome. Cell, 65(5), 825–836, doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90390-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Strnad P, Leidel S, Vinogradova T, Euteneuer U, Khodjakov A, & Gonczy P (2007). Regulated HsSAS-6 levels ensure formation of a single procentriole per centriole during the centrosome duplication cycle. Dev Cell, 13(2), 203–213, doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.D’Assoro AB, Lingle WL, & Salisbury JL (2002). Centrosome amplification and the development of cancer. Oncogene, 21(40), 6146–6153, doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marteil G, Guerrero A, Vieira AF, de Almeida BP, Machado P, Mendonca S, et al. (2018). Over-elongation of centrioles in cancer promotes centriole amplification and chromosome missegregation. Nat Commun, 9(1), 1258, doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03641-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nigg EA (2006). Origins and consequences of centrosome aberrations in human cancers. Int J Cancer, 119(12), 2717–2723, doi: 10.1002/ijc.22245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chan JY (2011). A clinical overview of centrosome amplification in human cancers. Int J Biol Sci, 7(8), 1122–1144, doi: 10.7150/ijbs.7.1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lingle WL, Barrett SL, Negron VC, D’Assoro AB, Boeneman K, Liu W, et al. (2002). Centrosome amplification drives chromosomal instability in breast tumor development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 99(4), 1978–1983, doi: 10.1073/pnas.032479999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mittal K, Ogden A, Reid MD, Rida PC, Varambally S, & Aneja R (2015). Amplified centrosomes may underlie aggressive disease course in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cell Cycle, 14(17), 2798–2809, doi: 10.1080/15384101.2015.1068478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pannu V, Mittal K, Cantuaria G, Reid MD, Li X, Donthamsetty S, et al. (2015). Rampant centrosome amplification underlies more aggressive disease course of triple negative breast cancers. Oncotarget, 6(12), 10487–10497, doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Duelli DM, Hearn S, Myers MP, & Lazebnik Y (2005). A primate virus generates transformed human cells by fusion. J Cell Biol, 171(3), 493–503, doi: 10.1083/jcb.200507069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Khodjakov A, Rieder CL, Sluder G, Cassels G, Sibon O, & Wang CL (2002). De novo formation of centrosomes in vertebrate cells arrested during S phase. J Cell Biol, 158(7), 1171–1181, doi: 10.1083/jcb.200205102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.La Terra S, English CN, Hergert P, McEwen BF, Sluder G, & Khodjakov A (2005). The de novo centriole assembly pathway in HeLa cells: cell cycle progression and centriole assembly/maturation. J Cell Biol, 168(5), 713–722, doi: 10.1083/jcb.200411126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meraldi P, Honda R, & Nigg EA (2002). Aurora-A overexpression reveals tetraploidization as a major route to centrosome amplification in p53−/− cells. EMBO J, 21(4), 483–492, doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.4.483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shekhar MP, Lyakhovich A, Visscher DW, Heng H, & Kondrat N (2002). Rad6 overexpression induces multinucleation, centrosome amplification, abnormal mitosis, aneuploidy, and transformation. Cancer Res, 62(7), 2115–2124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Duensing A, Liu Y, Perdreau SA, Kleylein-Sohn J, Nigg EA, & Duensing S (2007). Centriole overduplication through the concurrent formation of multiple daughter centrioles at single maternal templates. Oncogene, 26(43), 6280–6288, doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Duensing S, Lee LY, Duensing A, Basile J, Piboonniyom S, Gonzalez S, et al. (2000). The human papillomavirus type 16 E6 and E7 oncoproteins cooperate to induce mitotic defects and genomic instability by uncoupling centrosome duplication from the cell division cycle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 97(18), 10002–10007, doi: 10.1073/pnas.170093297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Borel F, Lohez OD, Lacroix FB, & Margolis RL (2002). Multiple centrosomes arise from tetraploidy checkpoint failure and mitotic centrosome clusters in p53 and RB pocket protein-compromised cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 99(15), 9819–9824, doi: 10.1073/pnas.152205299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Karakaya K, Herbst F, Ball C, Glimm H, Kramer A, & Loffler H (2012). Overexpression of EVI1 interferes with cytokinesis and leads to accumulation of cells with supernumerary centrosomes in G0/1 phase. Cell Cycle, 11(18), 3492–3503, doi: 10.4161/cc.21801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Anand S, Penrhyn-Lowe S, & Venkitaraman AR (2003). AURORA-A amplification overrides the mitotic spindle assembly checkpoint, inducing resistance to Taxol. Cancer Cell, 3(1), 51–62, doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00235-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Difilippantonio MJ, Ghadimi BM, Howard T, Camps J, Nguyen QT, Ferris DK, et al. (2009). Nucleation capacity and presence of centrioles define a distinct category of centrosome abnormalities that induces multipolar mitoses in cancer cells. Environ Mol Mutagen, 50(8), 672–696, doi: 10.1002/em.20532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hut HM, Lemstra W, Blaauw EH, Van Cappellen GW, Kampinga HH, & Sibon OC (2003). Centrosomes split in the presence of impaired DNA integrity during mitosis. Mol Biol Cell, 14(5), 1993–2004, doi: 10.1091/mbc.e02-08-0510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Levis AG, & Marin G (1963). Induction of Multipolar Spindles by X-Radiation in Mammalian Cells in Vitro. Exp Cell Res, 31, 448–451, doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(63)90026-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Loffler H, Fechter A, Liu FY, Poppelreuther S, & Kramer A (2013). DNA damage-induced centrosome amplification occurs via excessive formation of centriolar satellites. Oncogene, 32(24), 2963–2972, doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mikule K, Delaval B, Kaldis P, Jurcyzk A, Hergert P, & Doxsey S (2007). Loss of centrosome integrity induces p38-p53-p21-dependent G1-S arrest. Nat Cell Biol, 9(2), 160–170, doi: 10.1038/ncb1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sato C, Kuriyama R, & Nishizawa K (1983). Microtubule-organizing centers abnormal in number, structure, and nucleating activity in x-irradiated mammalian cells. J Cell Biol, 96(3), 776–782, doi: 10.1083/jcb.96.3.776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.D’Assoro AB, Barrett SL, Folk C, Negron VC, Boeneman K, Busby R, et al. (2002). Amplified centrosomes in breast cancer: a potential indicator of tumor aggressiveness. Breast Cancer Res Treat, 75(1), 25–34, doi: 10.1023/a:1016550619925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mittal K, Choi DH, Ogden A, Donthamsetty S, Melton BD, Gupta MV, et al. (2017). Amplified centrosomes and mitotic index display poor concordance between patient tumors and cultured cancer cells. Sci Rep, 7, 43984, doi: 10.1038/srep43984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ogden A, Rida PCG, & Aneja R (2017). Centrosome amplification: a suspect in breast cancer and racial disparities. Endocr Relat Cancer, 24(9), T47–T64, doi: 10.1530/ERC-17-0072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Loncarek J, Hergert P, Magidson V, & Khodjakov A (2008). Control of daughter centriole formation by the pericentriolar material. Nat Cell Biol, 10(3), 322–328, doi: 10.1038/ncb1694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Starita LM, Machida Y, Sankaran S, Elias JE, Griffin K, Schlegel BP, et al. (2004). BRCA1-dependent ubiquitination of gamma-tubulin regulates centrosome number. Mol Cell Biol, 24(19), 8457–8466, doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.19.8457-8466.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bornens M (2002). Centrosome composition and microtubule anchoring mechanisms. Curr Opin Cell Biol, 14(1), 25–34, doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(01)00290-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sonnen KF, Schermelleh L, Leonhardt H, & Nigg EA (2012). 3D-structured illumination microscopy provides novel insight into architecture of human centrosomes. Biol Open, 1(10), 965–976, doi: 10.1242/bio.20122337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vorobjev IA, & Chentsov YS (1980). The ultrastructure of centriole in mammalian tissue culture cells. Cell Biol Int Rep, 4(11), 1037–1044, doi: 10.1016/0309-1651(80)90177-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schmidt TI, Kleylein-Sohn J, Westendorf J, Le Clech M, Lavoie SB, Stierhof YD, et al. (2009). Control of centriole length by CPAP and CP110. Curr Biol, 19(12), 1005–1011, doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tang CJ, Fu RH, Wu KS, Hsu WB, & Tang TK (2009). CPAP is a cell-cycle regulated protein that controls centriole length. Nat Cell Biol, 11(7), 825–831, doi: 10.1038/ncb1889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zheng X, Ramani A, Soni K, Gottardo M, Zheng S, Ming Gooi L, et al. (2016). Molecular basis for CPAP-tubulin interaction in controlling centriolar and ciliary length. Nat Commun, 7, 11874, doi: 10.1038/ncomms11874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mittal K, & Aneja R (2020). Spotlighting the hypoxia-centrosome amplification axis. Med Res Rev, doi: 10.1002/med.21663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bagheri-Yarmand R, Biernacka A, Hunt KK, & Keyomarsi K (2010). Low molecular weight cyclin E overexpression shortens mitosis, leading to chromosome missegregation and centrosome amplification. Cancer Res, 70(12), 5074–5084, doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Loh JK, Lieu AS, Chou CH, Lin FY, Wu CH, Howng SL, et al. (2010). Differential expression of centrosomal proteins at different stages of human glioma. BMC Cancer, 10, 268, doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Reiter R, Gais P, Jutting U, Steuer-Vogt MK, Pickhard A, Bink K, et al. (2006). Aurora kinase A messenger RNA overexpression is correlated with tumor progression and shortened survival in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res, 12(17), 5136–5141, doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Reiter R, Gais P, Steuer-Vogt MK, Boulesteix AL, Deutschle T, Hampel R, et al. (2009). Centrosome abnormalities in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC). Acta Otolaryngol, 129(2), 205–213, doi: 10.1080/00016480802165767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yamamoto Y, Matsuyama H, Furuya T, Oga A, Yoshihiro S, Okuda M, et al. (2004). Centrosome hyperamplification predicts progression and tumor recurrence in bladder cancer. Clin Cancer Res, 10(19), 6449–6455, doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ganem NJ, Godinho SA, & Pellman D (2009). A mechanism linking extra centrosomes to chromosomal instability. Nature, 460(7252), 278–282, doi: 10.1038/nature08136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Anderhub SJ, Kramer A, & Maier B (2012). Centrosome amplification in tumorigenesis. Cancer Lett, 322(1), 8–17, doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Godinho SA, Kwon M, & Pellman D (2009). Centrosomes and cancer: how cancer cells divide with too many centrosomes. Cancer Metastasis Rev, 28(1–2), 85–98, doi: 10.1007/s10555-008-9163-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Milunovic-Jevtic A, Mooney P, Sulerud T, Bisht J, & Gatlin JC (2016). Centrosomal clustering contributes to chromosomal instability and cancer. Curr Opin Biotechnol, 40, 113–118, doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2016.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ogden A, Rida PC, & Aneja R (2012). Let’s huddle to prevent a muddle: centrosome declustering as an attractive anticancer strategy. Cell Death Differ, 19(8), 1255–1267, doi: 10.1038/cdd.2012.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kleylein-Sohn J, Pollinger B, Ohmer M, Hofmann F, Nigg EA, Hemmings BA, et al. (2012). Acentrosomal spindle organization renders cancer cells dependent on the kinesin HSET. J Cell Sci, 125(Pt 22), 5391–5402, doi: 10.1242/jcs.107474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kwon M, Godinho SA, Chandhok NS, Ganem NJ, Azioune A, Thery M, et al. (2008). Mechanisms to suppress multipolar divisions in cancer cells with extra centrosomes. Genes Dev, 22(16), 2189–2203, doi: 10.1101/gad.1700908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Grinberg-Rashi H, Ofek E, Perelman M, Skarda J, Yaron P, Hajduch M, et al. (2009). The expression of three genes in primary non-small cell lung cancer is associated with metastatic spread to the brain. Clin Cancer Res, 15(5), 1755–1761, doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pannu V, Rida PC, Ogden A, Turaga RC, Donthamsetty S, Bowen NJ, et al. (2015). HSET overexpression fuels tumor progression via centrosome clustering-independent mechanisms in breast cancer patients. Oncotarget, 6(8), 6076–6091, doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pawar S, Donthamsetty S, Pannu V, Rida P, Ogden A, Bowen N, et al. (2014). KIFCI, a novel putative prognostic biomarker for ovarian adenocarcinomas: delineating protein interaction networks and signaling circuitries. J Ovarian Res, 7, 53, doi: 10.1186/1757-2215-7-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rath O, & Kozielski F (2012). Kinesins and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer, 12(8), 527–539, doi: 10.1038/nrc3310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.De S, Cipriano R, Jackson MW, & Stark GR (2009). Overexpression of kinesins mediates docetaxel resistance in breast cancer cells. Cancer Res, 69(20), 8035–8042, doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sekino Y, Oue N, Shigematsu Y, Ishikawa A, Sakamoto N, Sentani K, et al. (2017). KIFC1 induces resistance to docetaxel and is associated with survival of patients with prostate cancer. Urol Oncol, 35(1), 31 e13–31 e20, doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2016.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sekino Y, Oue N, Koike Y, Shigematsu Y, Sakamoto N, Sentani K, et al. (2019). KIFC1 Inhibitor CW069 Induces Apoptosis and Reverses Resistance to Docetaxel in Prostate Cancer. J Clin Med, 8(2), doi: 10.3390/jcm8020225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ogden A, Rida PC, & Aneja R (2013). Heading off with the herd: how cancer cells might maneuver supernumerary centrosomes for directional migration. Cancer Metastasis Rev, 32(1–2), 269–287, doi: 10.1007/s10555-012-9413-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Koutsami MK, Tsantoulis PK, Kouloukoussa M, Apostolopoulou K, Pateras IS, Spartinou Z, et al. (2006). Centrosome abnormalities are frequently observed in non-small-cell lung cancer and are associated with aneuploidy and cyclin E overexpression. J Pathol, 209(4), 512–521, doi: 10.1002/path.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jung CK, Jung JH, Lee KY, Kang CS, Kim M, Ko YH, et al. (2007). Centrosome abnormalities in non-small cell lung cancer: correlations with DNA aneuploidy and expression of cell cycle regulatory proteins. Pathol Res Pract, 203(12), 839–847, doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gisselsson D, Jonson T, Yu C, Martins C, Mandahl N, Wiegant J, et al. (2002). Centrosomal abnormalities, multipolar mitoses, and chromosomal instability in head and neck tumours with dysfunctional telomeres. Br J Cancer, 87(2), 202–207, doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gong Y, Sun Y, McNutt MA, Sun Q, Hou L, Liu H, et al. (2009). Localization of TEIF in the centrosome and its functional association with centrosome amplification in DNA damage, telomere dysfunction and human cancers. Oncogene, 28(12), 1549–1560, doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gisselsson D, Gorunova L, Hoglund M, Mandahl N, & Elfving P (2004). Telomere shortening and mitotic dysfunction generate cytogenetic heterogeneity in a subgroup of renal cell carcinomas. Br J Cancer, 91(2), 327–332, doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gisselsson D, Palsson E, Yu C, Mertens F, & Mandahl N (2004). Mitotic instability associated with late genomic changes in bone and soft tissue tumours. Cancer Lett, 206(1), 69–76, doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2003.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ghadimi BM, Sackett DL, Difilippantonio MJ, Schrock E, Neumann T, Jauho A, et al. (2000). Centrosome amplification and instability occurs exclusively in aneuploid, but not in diploid colorectal cancer cell lines, and correlates with numerical chromosomal aberrations. Genes Chromosomes Cancer, 27(2), 183–190. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kawamura K, Izumi H, Ma Z, Ikeda R, Moriyama M, Tanaka T, et al. (2004). Induction of centrosome amplification and chromosome instability in human bladder cancer cells by p53 mutation and cyclin E overexpression. Cancer Res, 64(14), 4800–4809, doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Jiang F, Caraway NP, Sabichi AL, Zhang HZ, Ruitrok A, Grossman HB, et al. (2003). Centrosomal abnormality is common in and a potential biomarker for bladder cancer. Int J Cancer, 106(5), 661–665, doi: 10.1002/ijc.11251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Yamamoto Y, Matsuyama H, Kawauchi S, Furuya T, Liu XP, Ikemoto K, et al. (2006). Biological characteristics in bladder cancer depend on the type of genetic instability. Clin Cancer Res, 12(9), 2752–2758, doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Godinho SA, Picone R, Burute M, Dagher R, Su Y, Leung CT, et al. (2014). Oncogene-like induction of cellular invasion from centrosome amplification. Nature, 510(7503), 167–171, doi: 10.1038/nature13277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Basto R, Brunk K, Vinadogrova T, Peel N, Franz A, Khodjakov A, et al. (2008). Centrosome amplification can initiate tumorigenesis in flies. Cell, 133(6), 1032–1042, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.05.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Pihan GA, Wallace J, Zhou Y, & Doxsey SJ (2003). Centrosome abnormalities and chromosome instability occur together in pre-invasive carcinomas. Cancer Res, 63(6), 1398–1404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kayser G, Gerlach U, Walch A, Nitschke R, Haxelmans S, Kayser K, et al. (2005). Numerical and structural centrosome aberrations are an early and stable event in the adenoma-carcinoma sequence of colorectal carcinomas. Virchows Arch, 447(1), 61–65, doi: 10.1007/s00428-004-1191-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hsu LC, Kapali M, DeLoia JA, & Gallion HH (2005). Centrosome abnormalities in ovarian cancer. International Journal of Cancer, 113(5), 746–751, doi: 10.1002/ijc.20633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Chng WJ, Ahmann GJ, Henderson K, Santana-Davila R, Greipp PR, Gertz MA, et al. (2006). Clinical implication of centrosome amplification in plasma cell neoplasm. Blood, 107(9), 3669–3675, doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-09-3810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kronenwett U, Huwendiek S, Castro J, Ried T, & Auer G (2005). Characterisation of breast fine-needle aspiration biopsies by centrosome aberrations and genomic instability. Br J Cancer, 92(2), 389–395, doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kuhn E, Wang TL, Doberstein K, Bahadirli-Talbott A, Ayhan A, Sehdev AS, et al. (2016). CCNE1 amplification and centrosome number abnormality in serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma: further evidence supporting its role as a precursor of ovarian high-grade serous carcinoma. Mod Pathol, 29(10), 1254–1261, doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2016.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kuo KK, Sato N, Mizumoto K, Maehara N, Yonemasu H, Ker CG, et al. (2000). Centrosome abnormalities in human carcinomas of the gallbladder and intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts. Hepatology, 31(1), 59–64, doi: 10.1002/hep.510310112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Skyldberg B, Fujioka K, Hellstrom AC, Sylven L, Moberger B, & Auer G (2001). Human papillomavirus infection, centrosome aberration, and genetic stability in cervical lesions. Mod Pathol, 14(4), 279–284, doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3880303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Toma MI, Friedrich K, Meyer W, Frohner M, Schneider S, Wirth M, et al. (2010). Correlation of centrosomal aberrations with cell differentiation and DNA ploidy in prostate cancer. Anal Quant Cytol Histol, 32(1), 1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Katsetos CD, Reddy G, Draberova E, Smejkalova B, Del Valle L, Ashraf Q, et al. (2006). Altered cellular distribution and subcellular sorting of gamma-tubulin in diffuse astrocytic gliomas and human glioblastoma cell lines. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol, 65(5), 465–477, doi: 10.1097/01.jnen.0000229235.20995.6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Cai Y, Li BQ, & Cheng QM (2004). [Centrosome hyperamplificationin oral precancerous lesions and squamous cell carcinomas]. Hua Xi Kou Qiang Yi Xue Za Zhi, 22(3), 238–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Gustafson LM, Gleich LL, Fukasawa K, Chadwell J, Miller MA, Stambrook PJ, et al. (2000). Centrosome hyperamplification in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: a potential phenotypic marker of tumor aggressiveness. Laryngoscope, 110(11), 1798–1801, doi: 10.1097/00005537-200011000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Moskovszky L, Dezso K, Athanasou N, Szendroi M, Kopper L, Kliskey K, et al. (2010). Centrosome abnormalities in giant cell tumour of bone: possible association with chromosomal instability. Mod Pathol, 23(3), 359–366, doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2009.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Pinheiro CA, Soares IC, Penna V, Squire J, Reis RMV, da Silva SRM, et al. (2017). Centrosome amplification in chondrosarcomas: A primary cell culture and cryopreserved tumor sample study. Oncol Lett, 13(3), 1835, doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.5633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kramer A, Neben K, & Ho AD (2005). Centrosome aberrations in hematological malignancies. Cell Biol Int, 29(5), 375–383, doi: 10.1016/j.cellbi.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kramer A, Schweizer S, Neben K, Giesecke C, Kalla J, Katzenberger T, et al. (2003). Centrosome aberrations as a possible mechanism for chromosomal instability in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Leukemia, 17(11), 2207–2213, doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Hensel M, Zoz M, Giesecke C, Benner A, Neben K, Jauch A, et al. (2007). High rate of centrosome aberrations and correlation with proliferative activity in patients with untreated B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Int J Cancer, 121(5), 978–983, doi: 10.1002/ijc.22752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Neben K, Ott G, Schweizer S, Kalla J, Tews B, Katzenberger T, et al. (2007). Expression of centrosome-associated gene products is linked to tetraploidization in mantle cell lymphoma. Int J Cancer, 120(8), 1669–1677, doi: 10.1002/ijc.22404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Neben K, Giesecke C, Schweizer S, Ho AD, & Kramer A (2003). Centrosome aberrations in acute myeloid leukemia are correlated with cytogenetic risk profile. Blood, 101(1), 289–291, doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-04-1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Mittal K, Toss MS, Wei G, Kaur J, Choi DH, Melton BD, et al. (2020). A quantitative centrosomal amplification score predicts local recurrence in ductal carcinoma in situ. Clinical Cancer Research, doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-1272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]