Abstract

Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) is an important cause of permanent damage to central nervous system (CNS) that may result in neonatal death or manifest later as mental retardation, epilepsy, cerebral palsy, or developmental delay. The primary cause of this condition is systemic hypoxemia and/or reduced cerebral blood flow with long-lasting neurological disabilities and neurodevelopmental impairment in neonates. About 20 to 25% of infants with HIE die in the neonatal period, and 25-30% of survivors are left with permanent neurodevelopmental abnormalities. The mechanisms of hypoxia-ischemia (HI) include activation and/or stimulation of myriad of cascades such as increased excitotoxicity, oxidative stress, N-methyl-d-aspartic acid (NMDA) receptor hyperexcitability, mitochondrial collapse, inflammation, cell swelling, impaired maturation, and loss of trophic support. Different therapeutic modalities have been implicated in managing neonatal HIE, though translation of most of these regimens into clinical practices is still limited. Therapeutic hypothermia, for instance, is the most widely used standard treatment in neonates with HIE as studies have shown that it can inhibit many steps in the excito-oxidative cascade including secondary energy failure, increases in brain lactic acid, glutamate, and nitric oxide concentration. Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) is a glycoprotein that has been implicated in stimulation of cell survival, proliferation, and function of neutrophil precursors and mature neutrophils. Extensive studies both in vivo and ex vivo have shown the neuroprotective effect of G-CSF in neurodegenerative diseases and neonatal brain damage via inhibition of apoptosis and inflammation. Yet, there are still few experimentation models of neonatal HIE and G-CSF’s effectiveness, and extrapolation of adult stroke models is challenging because of the evolving brain. Here, we review current studies and/or researches of G-CSF’s crucial role in regulating these cytokines and apoptotic mediators triggered following neonatal brain injury, as well as driving neurogenesis and angiogenesis post-HI insults.

Keywords: Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, Neonatal, Pro-inflammatory cytokine, Apoptosis, Hypoxia ischemia, Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor, Angiogenesis, Neurogenesis

Background

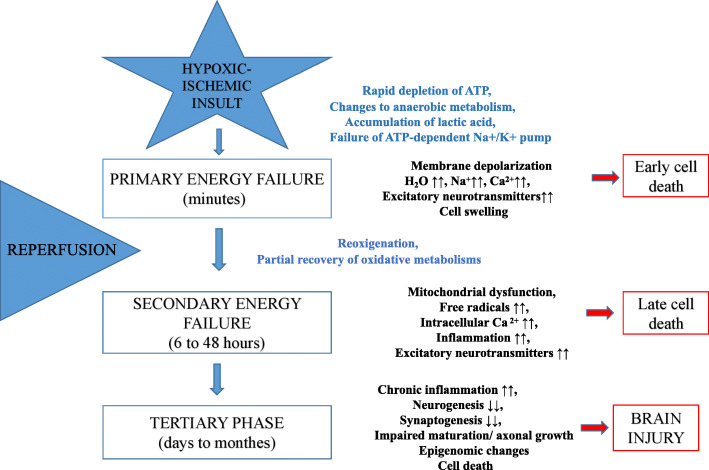

Numerous studies have shown that the most common contributor to early neonatal mortality is birth asphyxia with prematurity, infections, and low birth weight being other major contributors [1]. Birth asphyxia leads to significant brain injury with about 20-25% of asphyxiated newborns with hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) dying within the newborn period and another 25% developing long-term sequelae, most commonly, cerebral palsy, epilepsy, autism spectrum disorder, and sensory deficits [2]. These neurological insults result in significant short-term and long-term physical, emotional, and financial cost [3]. HIE has a myriad of etiologies commonly categorized into prenatal and perinatal [4]. The pathophysiological presentation of HIE has been extensively explored, including but not limited to activation of inflammatory agents, apoptotic cascades, excitotoxicity, activation of microglia and astrocytes, N-methyl-d-aspartic acid (NMDA) receptor hyperexcitability, mitochondrial impairment and oxidative stress, and delayed cell death post-HI [5–8], categorized into three phases outlined in Fig. 1 [1, 9].

Fig. 1.

Schematic illustration of pathogenic mechanisms of HIE following HI brain injury. Primary energy failure occurs immediately after the hypoxic–ischemic insult. After reperfusion, there is a secondary energy failure, which can extend in duration from 6 to 48 h. Brain injury (tertiary phase) continues to occur months to years after the injury resulting in decreased plasticity and reduced number of neurons. Latent period following resuscitation is ideal for interventions to decrease the impact of secondary energy failure. However, strategies are developed to attenuate tertiary brain damage which will expand the therapeutic window, substantially increasing the beneficial effects of neuroprotection in these infants and hence its impact on long-term outcome. The up arrows represent an increase while the down arrows show a decrease in the corresponding metabolite/process

The clinical manifestations of neonatal HIE are insidious because the immature brain is more resistant to injury from hypoxia-ischemia (HI) events due to lower cerebral metabolic rate, plasticity of immature central nervous system (CNS), and immaturity in the development of balance in the functional neurotransmitters [10]. Thus, neonates suffering from HIE will go unnoticed during the early stages of HI, rendering them more susceptible to secondary injury occurring 6 to 72 h after the initial insults (Fig. 1). Similarly, clinical assessments are sometimes inconclusive or vague due to the nature of disease status and presentation in these infants. Diagnostic guidelines have been set out in neonates with HIE by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG) [4] for initial assessment and appropriate management strategies. Routine serum biomarkers, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and electroencephalogram (EEG) [11–15] are the most commonly used diagnostic tools in recognizing brain injury in neonate that helps guide timely intervention and assessment of treatment outcome and prognostication.

Potential neuroprotective strategies targeting different pathways leading to neuronal cell death in response to hypoxic-ischemic insult have been investigated, including hypothermia, erythropoietin, magnesium, allopurinol, xenon, melatonin, growth factors (G-CSF, SCF, Epo), barbiturates, statins, and stem cells in various animal models of neonatal HIE [2, 16–18]. Therapeutic hypothermia (TH) is the most widely used standard treatment in neonatal HIE [19, 20], by inhibiting inflammatory cascades, reduced production of reactive oxygen species, inhibited apoptosis, an endogenous neuroprotective effect, reduced concentrations of free radicals, and neurotransmitters such as glutamate, glutamine, GABA, and aspartate [17, 21, 22], while others report ineffectiveness and/or adverse effects [23–25]. For instance, Arteaga et al. [9] reported that about 50% of infants treated with TH had adverse outcomes, such as cognitive impairment. A randomized control trial (RCT) by Shankaran et al. [26] concluded that cooling for 120 h or to 32.0 °C, or both, may be deleterious. Subsequently, TH did not improve EEG recovery when cooling was extended from 72 to 120 h and that it further impaired neuronal survival [27]. Thus, other neuroprotective agents are being explored that offer promise either as a monotherapy or in combination with therapeutic hypothermia.

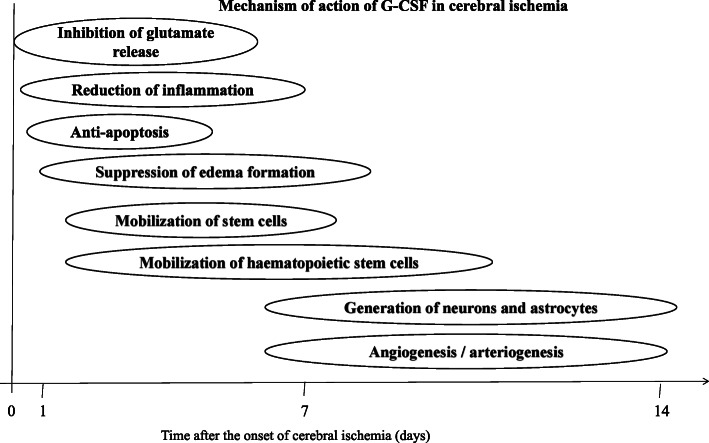

Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) is a 20-kDa protein that readily crosses the blood-brain barrier (BBB), which is a member of the hematopoietic growth factor family, that promote the proliferation, differentiation, and survival of hematopoietic stem cells with the obvious protective effect on neurons in peripheral and central nervous system [28–30]. The past few decades have explored its role from neutropenia-induced chemotherapy to neurological diseases and traumatic brain injury through regulation of both inflammatory and apoptotic mediators and enhancing neurogenesis and angiogenesis (Fig. 2) [29, 31–34]. G-CSF and its receptors are expressed by neurons, and their expression is regulated by ischemia, which points to an autocrine protective signaling mechanism [35]. Extensive studies in both in vivo and ex vivo have shown the neuroprotective effect of G-CSF in neurodegenerative diseases (Table1) such as Parkinson’s disease [53, 54], Alzheimer’s disease [55], and stroke [56–58], and clinical trials are ongoing to determine its efficacy and safety in these neurological diseases [59, 60]. Recent studies have focused on its neuroprotective effect in neonatal brain injury by regulating inflammatory and apoptotic mediators, thus attenuating neuroinflammation and neuronal apoptosis as well as enhancing neurogenesis and angiogenesis. Indeed, there are current reviews on HIE that have detailed its pathogenesis [4, 27], diagnostic modalities [13, 15], treatment interventions [2, 17], and emerging therapeutic agents [1], including G-CSF. In addition to these reviews, ours mainly focused on G-CSF role in modulating inflammatory and apoptotic mediators, driving of neurogenesis and angiogenesis, and signalling pathways mediated by G-CSF in attenuating neonatal ischemic brain damage. We therefore review current studies and/or researches of G-CSF’s crucial role in regulating these cytokines and apoptotic cascades triggered following neonatal hypoxia-ischemia injury and subsequently its role in promoting neurogenesis and angiogenesis, thus shedding more light on the current understanding of G-CSF’s potential protective mechanism(s) in neonatal brain injury.

Fig. 2.

Schematic illustration of the potential mechanism of G-CSF action in hypoxia ischemia injury. In the acute phase of cerebral ischemia, G-CSF can protect the brain by inhibiting glutamate release, anti-inflammatory, anti-apoptotic, and inhibit edema formation. In subacute phase, GCSFR can stimulate endogenous neuronal regeneration, mobilization of bone marrow stem cells, driving neuronal regeneration and functional repair, and promote neovascularization (angiogenesis and neurogenesis) during the chronic phase

Table 1.

An Overview of G-CSF application in Hypoxia-schaemia Brain Injury Models

| Model | Adult/Neonate | Dosage (μg/kg) | Application/Duration | Outcome | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute ischaemic cerebral injury (MCAO) | Adult SD rats | 100 | s.c. injected immediately after injury for 7d | Reduced infarct volume & necrotic cells | [29] |

| Increased Egr-1 & VEGF expression levels | |||||

| Stroke (BCAO) | adult male Swiss Webster mice | 50 | s.c. injected 30min afterocclusion for 4 to 7 consecutive days | Increased expression of G-CSF receptor | [36] |

| Decreased GRP78 expression & decreased ATF6 cleavage levels | |||||

| Decreased apoptotic protein signalling (DRI1 & P53) & increased pro-survival signalling (OPAI) | |||||

| Upregulated anti-apoptotic protein Bcle-2 and downregulated pro-apoptotic proteins Bax & Bak | |||||

| Increased locomotor sensitisation | |||||

| Cerebral ischaemia reperfusion (tMCAO) | Adult SD rats | 50 | s.c. injected 1h after restoring CBF for 5 consecutive days | Reduced infarct volume & oedema | [37] |

| Improved neurological function & reduced apoptotic neurons | |||||

| Downregulated the activation of the JNK apoptosis pathway | |||||

| Ischaemic brain injury (DHCA) | Newborn piglets | 34 | iv. 2h prior to inintiation of bypass | Reduced neuronal injury in the hippocampus | [38] |

| Focal cerebral ischaemia (MCAO) | Adult male SD rats | 50 | s.c. injected at the onset of reperfusion; 2nd injected at onset of reperfusion for 2d | Attenuated infarct volume & early neurological deficits | [39] |

| Elevated STAT3 phosphorylation & nuclear Pim-1 expression | |||||

| Increased expression of cIAP2 & Bcl-2 & decreased caspase-3 & Bax levels | |||||

| Hypoxia-ischaemia (RCCA ligation) | Neonatal SD rats | 50 | s.c. injected 1h after HI for 56 | Less vacuolization, neuron loss & tissue breakqown | [33] |

| Increased brain weight & G-CSF receptor expression | |||||

| Reduced cleaved caspase-3 activity | |||||

| Increased expression of anti-apoptotic pathway mediators | |||||

| Hypoxic-ischaemic brain damage (RCCA ligation) | Neonatal SD rats | 50 | s.c. injected 1h after HI for 6 days & 11 days | Promoted physical development & improved functional deficits | [40] |

| Reduced brain atrophy & increased systemic organ weight | |||||

| Increased exploratory behaviour & shorm-term memory | |||||

| Hypoxia- ischaemia (RCCA ligation) | Neonatal SD rat pups | 50 | s.c. injected 1h after HI | Reduced infarct volume & corticosterone levels | [41] |

| Decreased cleaved caspase-3 level & lowered Bax/Bcl-2 ratio | |||||

| G-CSF did not influence ACTH response | |||||

| Hypoxia- ischaemia (RCCA ligation) | Neonatal SD rat pups | 50 | s.c. or i.p. 1h after HI for 4d | Reduced infarct volume & lung injury | [30] |

| Increased neutrophil count & less brain tissue atrophy | |||||

| Improved physical development & neurological function | |||||

| Hypoxia-ischaemia (RCCA ligation) | Neonatal SD rat pups | 50 | s.c. injected 1h after HI | Reduced infarct volume & increased expression of G-CSF receptor in neurons | [42] |

| Increased p-AKt expression & decreased p-GSK-3β/GSK-3β ratio | |||||

| Decreased aopototic markers & TUNEL positice cells in neuron | |||||

| Perinatal hypoxia | Neonatal SD rat pups | 10, 30, 50 | s.c. injected 1d after HI | Attenuated PSD-95 protein expression levels & improved long-term deficits | [43] |

| Increased phosphorylated activity of pRaf-pERK1/2-PCREB pathway | |||||

| Enhanced increase expression of neurogenesis in hippocampal neuron | |||||

| Stroke (MCA ligation) | Adult male SD rats | 15 | s.c. injected 1h after restoring CBF for 15d | Decreased mortality rate & less effect in reducing infarct volume | [44] |

| Improved functional recovery of motor function | |||||

| Increased number of proliferating cells & new neurons in the SVZ | |||||

| Hypoxia-ischaemia (RCCA ligation) | Neonatal SD rats | 50 | i.p. immediately after HI induction | Attenuated cerebral infarction & improved body weight | [45] |

| Inhibited apoptosis by decreasing apoptotic cells & increased brain volume | |||||

| Focal cerebral ischaemia (MCAO) | Male Wistar rats | 60 | iv 30min after occlusion | Reduced infarct volume & mortality rate | [46] |

| Increased STAT3 expression & anti-excitotoxic effect | |||||

| Stroke (MCAO/CCA) | 50 | iv 60min after induction | Elevated neutrophil count & reduced infarct volume | [47] | |

| Increased expression of G-CSF receptor in neurons | |||||

| (MCAO) | 60 | iv 2h after onset of occlusion for 5d | Increased protein level of STAT3 & increased AKt phosphorylation | ||

| Improved long-term behaviour | |||||

| Hypoxic-ischaemic brain injury (MCAO) | Neonatal mice pups | 200 | s.c. injected 1h after injury & 60h after injury for 5d | Did not improved neurobehavioural outcomes & brain injuries | [48] |

| Perinatal hypoxia | Neonatal rat pups | 30 | i.p. 1d after HI induction for 6d | Enhanced neurogenesis & improved long-term cognitive function | [49] |

| Hypoxia- ischaemia (RCCA ligation) | Neonatal SD rat pups | 50 | i.p. 2.5h after HI induction | Decreased expression levels of TNF-α and IL-1β & increased IL-10 levelsDecreased expression levels of TNF-α and IL-1β & increased IL-10 levels | [50] |

| Increased Bcl-2 expression levels & decreased CC3 and Bax expression levels | |||||

| Upregulated p-mTOR and p-P70S6K protein expression levels | |||||

| Hypoxia-ischaemia (RCCA ligation) | Neonatal SD rat pups | 50 | s.c. injected 1h after HI | Showed localisation of G-CSF receptor in enthothial cells | [51] |

| Decreased β-catenin and p120-catenin phosphorylationDecreased β-catenin and p120-catenin phosphorylation | |||||

| Attenuated PICs (IKKβ, NF-κB, TNF-α, IL-1β) & enhanced IL-10 levelsAttenuated PICs (IKKβ, NF-κB, TNF-α, IL-1β) & enhanced IL-10 levels | |||||

| Decreased adheren proteins & increased tight junction proteins expression | |||||

| Hypoxia-ischaemia (RCCA ligation) | Neonatal SD rat pups | 50 | s.c. injected 1h after hypoxia | Inhibited corticosterone synthesis by activating its receptor in cortical cells | [52] |

| Increased expression of JAK2, PI3K, AKt and PDE3B proteins | |||||

| Inhibited cAMP elevation induced by cholera toxin | |||||

| Decreased infarct volume and increased body weight |

Abbreviations: G-CSF Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor, MCAO Middle cerebral artery occlusion, BCAO Bilateral cerebral artery occlusion, tMCAO transient middle cerebral artery occlusion, DHCA Deep hypothermic circulation arrest, RCCA Right common carotid artery, VEGF Vascular endothelial growth factor, HI Hypoxia-ischaemia, Egr-1 Early growth response-1, s.c subcutaneous, iv intravenous, i.p intraperitoneal, GRP78 Glucose regulated protein 78, ATF6 Activating transcription factor 6, DRP1 Dynamin-related protein 1, OPA1 Optic atrophy protein 1, JNK c-Jun N-terminal kinase, Bcl-2 B-cell lymphoma 2, cIAP2 cellular inhibitor of apoptosis protein 2, ACTH Adrenocorticotropic hormone, p-GSK-3β phosphorylated glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta, p-AKt phosphorylated protein kinase B, PSD-95 Postsynaptic density protein-95, pCREB phosphorylated cAMP-responsive element binding protein, pERK phosphorylated exracellular signal-regulated kinase, pRaf phosphorylated mitogen-activated protein-kinase-kinase-kinase, SVZ Subventricular zone, CC3 Cleaved caspase-3, STAT3 Signal transducer and activated protein kinase 3, p-P70S6K Phosphorylated p70 ribosomal s6 protein kinase, p-mTOR Phosphorylated mammalian target of rapamycin, IL-10 Interleukin 10, IL-1β Interleukin 1 beta, TNF-α Tumour necrosis factor-alpha, NF-κB Nuclear factor-kappa B, IKKB Inhibitor of kappa B kinase, PICs Pro-inflammatory cytokines, PDE3B Phosphodiesterase 3B, AKt Protein kinase B, PI3K Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, JAK2 Janus kinase 2, cAMP cyclic adenosine monophosphate, CBF Cerebral blood flow

Regulation of cytokines and apoptosis by G-CSF in neonatal HIE

There are numerous studies that have shown the neuroprotective effect of G-CSF via inhibition of apoptosis and inflammation as well as by stimulating angiogenesis and neurogenesis both in adults and neonatal animal HI models [61–64]. Indeed, G-CSF is implicated in the regulation of cytokines that are being disrupted following HI insults by decreasing pro-inflammatory and increasing anti-inflammatory cytokines. Similarly, G-CSF inhibits pro-apoptotic factors and increases anti-apoptotic factors.

Regulation of cytokines by G-CSF in neonatal HIE

Prior studies have shown that interleukin-1 beta (IL-1ß) and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) are early response cytokines in neuronal injury [65]. Increased expression of TNF-α induces neutrophil infiltration that increases endotheliocyte permeability and activates the matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), which damage the blood-brain barrier (BBB) leading to swelling and degeneration of neurons and glial cells [66], while IL-1ß acts primarily through transcriptional activation of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) gene and nitric oxide (NO) generation thereby exacerbating brain injury [42]. These cytokines’ inflammatory response even persist in school-age children with neonatal encephalopathy (NE) showing poor neurodevelopmental outcome [48, 67]. Increased TNF-α expression also results in increase of caspase-3 cleavage and causes neuronal apoptosis [68]. Thus, TNF-α not only participates in neuronal inflammation but also in inducing apoptosis in neonatal HI injury. The imbalance between pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines caused by HI damage also favors oligodendrocyte precursor proliferation into astrocytes instead of oligodendrocytes, and as a result, there is subsequent impairment of myelination, increased production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (PICs), and suppression of anti-inflammatory cytokine levels [69]. Activated astrocyte (astrogliosis) has both positive and negative roles in cytokine regulation following brain injury [70]; activated microglia have similar effects by expressing both pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory mediators depending on the degree and duration of insult being inflicted [4, 5, 71, 72].

The effect of G-CSF is demonstrated by preventing neuronal and glial pro-inflammatory cytokine expression. This is evidenced by preventing an overactivation of monocytes and lymphocytes by reducing the release of pro-inflammatory mediators while simultaneously activating the anti-inflammatory defense neutrophils [73]. Our previous study has shown that TNF-α and IL-1ß were upregulated after HI in neonatal rat model and were further elevated by rapamycin treatment with increased immunoreactivity of neuronal cell bodies. Their expression levels were subsequently decreased by G-CSF treatment [74]. Treatment with IL-10 is thought to decrease the level of TNF-α and IL-1ß after traumatic brain injury (TBI) [38]. Similarly, our previous study showed a decreased level of IL-10 expression after HI injury, while G-CSF administration was associated with its increased expression level thereby reducing further surges of TNF-α and IL-1ß and thus improving neurologic outcomes [74]. Xiao et al. [40] demonstrated that G-CSF treatment increased the mobilization of circulating CD34+ cells, polarizes T cell differentiation from Th1 to Th2 cells, and induces Th2 responses with the production of IL-4 and IL-10, accompanied by a decrease in production of IFN-ɣ and IL-2, thereby suppressing T cell proliferative responses to allogeneic stimulation that are anti-inflammatory and decreasing HI-induced injury, especially in the dentate gyrus by generating new neurons. G-CSF is said to significantly elevate the CD4 + CD25+ regulatory T cell subset in microglia-mediated reactive T cells as well as to inhibit MHC-II expression of microglia after lipopolysaccharide (LPS) activation or in the interactions of microglia and reactive T cells [75]. Other studies have shown that G-CSF effectively mobilized CD34-positive hematopoietic stem cells (HSC) in the preterm sheep thereby promoting proliferation of endogenous neural stem cells [76]. G-CSF can also stabilize the BBB and modulate neuroinflammation, and G-CSF is more neuroprotective in neonatal HI injury compared to adults [77].

Certain other studies have reported mixed results about the effectiveness of G-CSF treatment in ischemic stroke in terms of improving neurodegenerative and neurobehavioral outcomes, especially during the hyperacute and acute stage of HI injury [64, 78–80]. One study reported that G-CSF exacerbate brain damage as G-CSF increases the availability of neutrophils, which in turn enhances the inflammatory response in the brains of newborns [81]. Kallmunzer et al. [36] also reported a lack of neuroprotective or neuroregenerative effects of G-CSF in a rodent model of intracerebral hemorrhage. In a meta-analysis, England et al. [80] reported that G-CSF did not improve stroke outcome in individual patient with ischemic stroke when assessed by the National Institute of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) or Barthel Index (BI) while Huang et al. [64] analyzed 14 trials of G-CSF therapy in stroke and did not identify adequate evidence for the beneficial effects of this treatment modality in patients. Specifically, no favorable effects were noted on stroke outcomes including NIHSS score, the incidence of severe adverse events (SAEs), and mortality in patients treated with G-CSF versus control or placebo-treated patients. In another trial, the efficacy and tolerability of G-CSF were examined in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), a neurodegenerative disease, and the authors concluded that it has no clinical benefit in subjects with ALS [41], in contrast to previous studies [82, 83].

As some of these results and findings are mainly focused on adult ischemic stroke, it should be noted that differences do exist between the adult and neonate reaction to HI-induced brain insults, possibly due to immaturity of neonatal neurons. Specifically, there are differences in functional BBB response to acute experimental stroke between neonates and adults, as well as in gene expression of cerebral endothelial cells [25]. Other striking factors include initiation of G-CSF treatment, that is, the timing of G-CSF treatment might influence its neuroprotective effect; different dosages have been used both in ischemic stroke and neonatal HIE animal models, ranging from 10 to 250 μg/kg for subcutaneous injection and 5 to 60 mg/kg for intravenous injection [43, 61, 78]; route of administration varies according to each study; and duration of treatment ranges from 3 to 10 days [64, 80, 84]. Intranasal administration of G-CSF has also been examined in ischemic brain injury as potentially more effective and feasible [57]. All these factors influence the effectiveness of G-CSF across treatment modalities both in vivo and ex vivo. Therefore, such results should be judiciously interpreted and translated into neonates with HIE. Hence, there are still some loopholes and more studies are needed to examine the neuroprotective effect of G-CSF in neonatal brain injury at different times, doses, and duration in relation to regulation of neuroinflammatory and apoptotic cascades. Similarly, long-term neurofunctional assessment of G-CSF in neonatal hypoxia-ischemia brain injury should be warranted.

Regulation of apoptosis by G-CSF in neonatal HIE

Apoptosis can be triggered via the extrinsic pathway, which involves activation of cell surface death receptors, or the intrinsic pathway, which requires mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP) [85], which leads to loss of mitochondrial transmembrane potential, formation of transition pores, and production of reactive oxygen species, subsequently leading to release of cytochrome c from mitochondria resulting in activation of caspases and other effectors of DNA fragmentation and cell death [7, 86, 87]. Increased expression of pro-apoptotic mediators causes translocation of apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF) from the mitochondria to the nucleus, where it interacts with DNA and stimulates chromatin condensation. Overexpression of AIF can aggravate neonatal brain injury after HI that further increases its translocation [39].

Studies have shown that neonatal HI injury is associated with Bax translocation to mitochondria with a concomitant decrease in BCL-2, resulting in activation of caspase-3 leading to apoptotic cell death that peaks from 24 to 72 h post HI brain injury [33]. BAD is involved in apoptotic and nonapoptotic processes, and these dual activities are regulated by post-transcriptional modifications. Activation of BAX and BAD also promote MOMP [88]. The BCL-2 family proteins are key regulators of MOMP and play critical role in the intrinsic apoptotic pathway, classified into anti-apoptotic (Bcl-2, Bcl-xl, Bcl-w) and pro-apoptotic (Bax, Bak, Bim, Bid, Bad) [45]. The increased expression of pro-apoptotic markers is also influenced by the hormones involved in the pituitary–adrenal response [89], while in the extrinsic pathway, binding ligands to death receptors (TNF-α, Fas, TRAIL, etc.) leads to activation of caspase-8 [49]. In addition, BCL-2 has been demonstrated to play a critical role in preventing apoptosis induced by rapamycin derivatives that have been approved for the treatment of patients with various malignancies, thus suggesting that overexpression of antiapoptotic proteins such as BCL-2 might serve as a surrogate marker for resistance to rapalogues [90]. GSK-3ß is highly expressed in brain regions including the cerebral cortex, hippocampus, and cerebellum, and its overactivation is involved in neuronal pro-apoptosis, and dysregulation of this kinase has a devastating effect on neurodevelopment [91]. Its overexpression can increase caspase-3 activity [92], which in turn activates apoptosis.

G-CSF administration downregulates GSK-3ß activity, resulting in reduced neuronal cell death, apoptosis, and infarct volume, as well as upregulating anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 expression levels [45, 77]. Our previous study has demonstrated that increased Bax expression levels and cleaved caspase-3 (CC3) activation were attenuated significantly by G-CSF treatment and simultaneously increasing BCL-2 expression levels that were decreased following HI-induced injury. We further stated that the effect of G-CSF in modulating these apoptotic factors was abolished by rapamycin, an inhibitor of mTOR [74]. Other studies have reported similar neuroprotective effects of G-CSF by inhibiting apoptosis [63]. The neuronal anti-apoptotic action of G-CSF may also be mediated in part by the anti-apoptotic protein cIAP2 [93]. G-CSF also inhibits the mitochondrial-dependent activation of caspase-3, an apoptotic activator during HI injury [94]. Thus, G-CSF’s underlying mechanism(s) in the neuronal anti-apoptotic effect can be indirect through suppression of TNF-α, which increases caspase-3 cleavage or directly inhibiting caspase-3 and other pro-apoptotic mediators.

G-CSF in neurogenesis and angiogenesis

Neurogenesis is an important process for the reconstruction of neural networks and recovery of functional outcomes that are believed to continue throughout adulthood. It mainly occurs in the subventricular zone (SVZ) and subgranular layer of the hippocampal dentate gyrus, where the local environment tightly regulates neurogenesis [2]. Nonetheless, endogenous neurogenesis, stimulated by cerebral ischemia is not sufficient for the recovery of neurological functions [2]. The SVZ is more susceptible to neonatal HI brain injury located in the hippocampal dentate gyrus. Previous studies have shown that G-CSF facilitates bone marrow cell mobilization to the brain and drives neurogenesis and synaptic efficacy recovery thereby improving long-term functional outcome, which is mainly observed in the SVZ of the injured neonatal brain post-HI insult [61, 95, 96]. G-CSF also enhances concentrations of neurotrophic factors (GDNF and BDNF) that stimulate hippocampal neurogenesis as well as neuroplasticity by altering synaptic activity and possesses anti-apoptotic properties augmenting the neurogenic response to brain injury [97]. Endogenous role of G-CSF in the brain neuroprotective mechanism has also been demonstrated in ischemic model, where mice deficient of G-CSF showed overwhelming upregulation of matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9), a key factor in the activation of microglia and astrocytes, while treatment of G-CSF suppresses its expression [2, 98].

Angiogenesis is a physiological process by which new blood vessels are formed from pre-existing blood vessels. It is a complex and highly ordered process that relies upon extensive signaling networks both among and within endothelial cells (ECs) and their associated cells such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) proteins and angiopoietin-1 (Ang-1), which are required for angiogenesis [99]. Hypoxia-inducing factor-1 alpha (HIF-1α) is involved in early brain development and proliferation of neuronal progenitor cells. HIF also modulates cerebral hypoxic stress responses and activates endogenous neuroprotective systems during acute and late stages of HI damage of the developing brain [100]. HIF-1α induces VEGF expression and its receptors FMS-like tyrosine kinase (FLK-1) and fetal liver kinase-1 (Flk-1) in neurons facilitating blood reperfusion recovery, correlating with angiogenesis [25]. Late-stage of HIF-1α induction increases VEGF production that improves functional recovery and brain repair [101].

G-CSF administration increases local VEGF expression, which is necessary for vascular angiogenesis [102], thus corroborating its role in promoting angiogenesis through upregulation of VEGF expression via signaling pathways. Angiopeitin-1 (Ang-1), which is upregulated by G-CSF, is thought to reduce vascular solute permeability and contributes to vascular maturation and BBB stabilization by increasing the expression of BBB-related tight junction proteins (occludin, claudin-5, and zonula occludens protein 1) [103]. G-CSF treatment regulates the expression of VEGF and early growth response-1 (Erg-1) thereby ameliorating acute ischemic cerebral injury [29]. Mobilization of monocyte into blood vessels by G-CSF also stimulate angiogenesis [40]. Other reports argued that VEGF and MMP are involved in the initial opening of BBB within hours of an HI insult, which disrupt the basilar membrane and cause further damage to the BBB, especially VEGF-A which increases vascular permeability by uncoupling endothelial cell-cell junctions, resulting in BBB leakage and worsened outcomes [2, 103, 104]. Zhang et al. [25] stated that acute increases of VEGF results in the BBB leakage, whereas delayed upregulation of VEGF around the ischemic boundary area may prompt angiogenesis and reconstruction of the neurovascular unit (NVU). Thus, further research is needed to elucidate the pertinent role of VEGF after neonatal HI injury and its subsequent regulation by G-CSF.

Combinational therapy with other agents

Recent reports have advocated for combination strategies in neonatal HI brain injury and that it is more effective than G-CSF monotherapy. For instance, Yu and colleagues [105] demonstrated that both erythropoietin (Epo) and G-CSF combined produce functional recovery in a mouse model of hypoxic-ischemic brain injury in a time-dependent manner, and the underlying mechanisms may be the induction of HIF-1α activity in both cytosol and nucleus, and an early change in the cell fate determination from astrogliosis toward neurogenesis. Erythropoietin (EPO) a glycoprotein that controls erythropoiesis is expressed in neural progenitor cells, mature neurons, astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, microglia, and endothelial cells. Epo has anti-apoptotic and anti-inflammatory effects and supports tissue remodeling by promoting neurogenesis, oligodendrogenesis, and angiogenesis [106]. Both G-CSF and EPO can readily cross the BBB, making them a possible candidate in neonates with HI insults. Liu et al. [107] reported that combination of G-CSF and EPO could synergistically promote proliferation of neural progenitor cells residing in the hippocampus and subventricular region of the brain. Another study examined the repetitive and long-term use of G-CSF+ EPO in stroke patients and reported similar neuroprotective effect with good tolerability and no associated adverse effects observed [108]. But in Yu and colleagues’ study, they reported that combined G-CSF and EPO does not show improvement during the chronic phase of HI injury [105]. Thus, the neuroprotective effects of combinational therapy of G-CSF and EPO in neonatal HIE need to be elucidated further to understand the underlying mechanisms.

Doycheva et al. [109] also concluded that G-CSF + SCF (stem cell factor) improved body weight, reduce brain-tissue atrophy, and improved neurological outcome following HI in the neonatal rat pup. Specifically, G-CSF + SCF induced more stable and long-lasting functional improvement in chronic strokes by increasing angiogenesis and neurogenesis through bone marrow-derived cells and the direct effects on stimulating neurons to form new neuronal networks [110, 111]. Hence, both G-CSF and SCF may work synergistically in improving the overall outcome of neonatal HI brain damage. Caspase-3 activation is reduced when G-CSF and SCF treatment are combined resulting in decreased apoptotic cell death, though other studies further reported that G-CSF/SCF and FL treatment did not affect apoptosis-inducing factor-dependent apoptosis or cell proliferation, and thus does not convey neuroprotection in neonatal HIE [112, 113]. Indeed, there are mixed reports about the neuroprotective effect of combinational G-CSF and SCF treatment in neonatal HI-induced brain injury. One study on HI mice demonstrated that G-CSF and SCF, given separately or in combination, have no neuroprotective effect, but rather a deleterious impact on neonatal excitotoxic brain damage [81].

G-CSF + hUCB can also decrease the number of MHCII+ cells not only in the corpus callosum and fornix but also in the cerebral peduncle. As G-CSF crosses the BBB, it acts upon neurons and glial cells through the G-CSF receptor. Indeed, glial cell activation has been demonstrated to downregulate expression of proinflammatory cytokines and to enhance neurogenesis [114]. One study demonstrated that intranasal administration of umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells (UC-MSCs) significantly reduces neuroinflammation and protects hippocampal neurons, as well as increased concentration of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 in serum, thus contributing to neuroprotection [23]; similarly, UCB, especially its subtype EPCs (endothelial progenitor cells), has the ability to modulate neuroinflammation and reduce brain injury and behavioral deficits in perinatal HI brain injury [115]. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) derived from human umbilical cord blood (hUCB) conferred neuroprotective and neuroregenerative benefits by improving angiogenesis and vasculogenesis [116]. MSCs plus G-CSF also decreased oxidative stress factors aggravated by HI brain injury [117]. G-CSF in combination with taurine is protective in primary cortical neurons against excitotoxicity induced by glutamate as well as suppresses endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress [118]. Thus, synergistic therapies may exert and offer better functional improvements in neonatal HI brain injury, though more research is needed to explore the underlying mechanism(s).

Recently, Griva et al. [119] reported that the combination of neuroprotective treatments of G-CSF and enriched environment (EE) may enhance neuroprotection and it might be a more effective strategy for the treatment of neonatal hypoxic-ischemic brain injury by altering synaptic plasticity reflected by increased synaptophysin expression levels thus further enhancing cognitive function. Doycheva et al. [30] demonstrated that G-CSF + Ab improved body weight, reduced brain tissue damage, and improved long-term neurological function when assessed at 96 h and 5 weeks post HI in the neonatal rat pups, as well as conferring greater neuroprotection by depleting neutrophil accumulation, while G-CSF + metyrapone treatment not only lower caspase-3 expression level but also reduce corticosterone levels in neonates after HI injury [89]. Surprisingly, there has not been any study evaluating combinational therapy of G-CSF and therapeutic hypothermia (TH), as other modalities have been tried and underwent and/or are undergoing clinical trials in neonatal HIE, such as with epo and TH [120–122], xenon and TH [51, 123, 124], melatonin and TH [46, 47], and allopurinol and TH [125]. Thus, more study is needed to explore and evaluate the neuroprotective effect of G-CSF in combination with therapeutic hypothermia as well as other emerging agents.

G-CSF-mediated signaling pathways in neonatal HIE

Stimulation of G-CSF by its receptor activates many downstream signaling pathways such as the Janus kinase (JAK)/signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT), the Ras/mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), and the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (Akt) pathways [50] thereby exerting its neuroprotective effect.

The JAK-STAT signaling pathway is a chain of interactions between protein cells and is involved in many cellular processes that communicate information from chemical signals outside of a cell to the cell nucleus, resulting in the activation of genes through transcriptional processes [126]. The neuroprotective effect of G-CSF is manifested by activating the anti-apoptotic pathway via the JAK/STAT3 signaling, and it does so by suppressing the pro-apoptotic mediators and upregulating anti-apoptotic mediators via binding to its receptors (G-CSFR) in neurons. Moreover, G-CSF increases the activation of STAT3 pathway in glial cells together with increased cIAP2 expression which is a member of the inhibitor of apoptosis protein (IAP) family, subsequently regulating the activity of both initiator (caspase-9) and effector caspases (caspase-3 and -7) in ischemic mouse models [40, 94]. It can directly activate the JAK/STAT3 pathway as well [33, 93, 127], thereby promoting neurogenesis. Pim-1 increases cell survival through the regulation of bcl-2 proteins and that its upregulation after HI is enhanced by G-CSF treatment. Its expression is said to be paralleled to STAT3 expression, suggesting an association between the two in ischemic pathology [33, 94]. G-CSF also increased expression of STAT3 in the penumbra mediated by G-CSFR [128]. In short, these substrates and/or proteins are regulated by G-CSF and its receptor along the JAK/STATS signaling pathway following HI injury, which in turn favors neuroprotection.

The PI3K/AKT pathway is a key signaling pathway that participates in various cellular processes such as cell proliferation, survival, differentiation, and apoptosis [129, 130]. G-CSF enhances neurogenesis and neuroblast migration after stroke by regulating the PI3K/Akt pathway as well as modulates the NMDA receptor of glial cells exposed to PLS-induced brain damage [68]. The nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) is a central transcriptional factor that is regulated and activated by Akt accompanied by activation of the inhibitor of κB (IKB) kinase (IKK) [131]. Activation of NF-κB, especially the canonical pathway, triggers the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (PICs) and nitric oxide (NO) [132]. Phosphorylated Akt by G-CSF inactivates the canonical NF-κB pathway and inhibit the production of PICs and NO, further ameliorating neuroinflammation. Moreover, G-CSF phosphorylates Akt leading to downstream inactivation of GSK-3ß that will ultimately decrease apoptosis. G-CSF as well reduces adherens (VCAM-1 and ICAM-1) and increases tight junction (claudin 3 and 5) protein expression levels via the G-CSFR/PI3K/Akt/GSK-3ß signaling pathway [50].

The mammalian target of rapamycin/p70 ribosomal S6 protein kinase (mTOR/p70S6K) pathway has been implicated in neurogenesis as well, by decreasing the expression of PICs [133], as well as increasing IL-10 expression [134]. mTOR acts as a molecular system integrator to support organismal and cellular interactions with the environment [135], which regulates cellular metabolism, growth, and proliferation through two protein complexes, mTORC1 and mTORC2. mTOR activity is also thought to upregulate the translation of synaptic mRNAs via 4E-BP and S6K [136] by facilitating neuronal plasticity and activity [137]. Previous studies have demonstrated a decreased activation of S6K by rapamycin, an mTOR inhibitor, as well as loss of S6K function leads to increased astrocyte death in ischemic models, while G-CSF treatment increases S6K expression levels [138, 139], driving cellular functions as S6K phosphorylates and activates several substrates that promote mRNA translation initiation and other cellular processes [140]. Our previous study has shown that treatment with G-CSF decreases inflammatory mediators and apoptotic factors, attenuating neuroinflammation and neuronal apoptosis via the mTOR/p70S6K signaling pathway, which represents a potential target for treating HI induced brain damage in neonatal HIE [74].

The PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway is an intracellular signaling pathway important in regulating the cell cycle. Therefore, it is directly related to cellular quiescence, proliferation, cancer, and longevity. PI3K activation phosphorylates and activates AKT, localizing it in the plasma membrane [52, 141]. G-CSF can upregulate brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) which in turn induces autophagy through the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway [2]. The neurotrophic nuclear transcription factor phosphorylated cAMP-responsive element-binding protein at serine 133 (pCREBSer-133) serves an important role in neurological regulation of ion channel function, neuronal differentiation and maturation, and the processes of learning and memory. This transcription factor is decreased during HI insult, while treatment of G-CSF was shown to significantly increase the expression of pRaf-pERK1/2-pCREBSer-133 pathway in neonates exposed to perinatal hypoxia [61]. One study has demonstrated that G-CSF treatment inhibits steroidogenesis through activation of the JAK2/PI3K/PDE3B signaling pathway by reducing the levels of cAMP expression in HI-induced brain injury [142]. Activation of ERK has been shown to be neuroprotective, both in adults and neonatal brain injury, while MAPK p38 is best known for transduction of stress-related signals, regulation of inflammatory gene production, and NF- κB recruitment to selected targets, and both ERK and MARK p38 are regulated by G-CSF [37]. G-CSF downregulates the activation of the phosphorylated JNK and c-jun pathway in the cerebral ischemia-reperfusion rats model [44].

Thus, G-CSF plays diverse roles in neonatal HIE through diverse signaling pathways. Modi et al. [45] summarizes the steps and effect of G-CSF across the signaling pathways that have been implicated in neonatal HI injury either through inhibition or upregulation and phosphorylation of their substrates thereby eliciting neuroprotection.

Conclusion

There are numerous studies that have shown the important role G-CSF plays in neurodegenerative diseases, ischemic stroke, and traumatic brain injury both using in vivo and ex vivo models. Recent research has specifically focused on its neuroprotective effect in neonatal HIE with both positive and mixed results. Indeed, G-CSF exerts a pivotal role in the control of immune response and acts as an anti-inflammatory cytokine, preventing an overactivation of monocytes and lymphocytes by reducing the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines as well as stabilizing the BBB and modulating neuroinflammation; inhibits pro-apoptotic mediators; enhances concentration of neurotrophic factors and facilitates bone marrow cell mobilization thereby driving neurogenesis; increases local VEGF expression necessary for vascular angiogenesis; upregulates Ang-1 that reduces vascular solute permeability; and contributes to vascular maturation and BBB stabilization. Despite these progresses being made, there are still few experimentation models of neonatal HIE and G-CSF’s neuroprotectiveness either directly or through signaling pathways, and extrapolation of adults’ stroke models is challenging due to the evolving neonatal brain. Also, there are mixed results about the effectiveness of G-CSF in improving HI-induced brain injury in neonates, specifically in the area of initiation of treatment, dosage, route of administration, and duration of treatment; this calls for more in-depth research to elucidate its underlying mechanisms and pertinent role in neuroprotection, as well as its long-term effect in neurological and behavioral outcomes.

Recent studies have focused on combinational treatment in neonatal HI brain injury and that it is more effective than G-CSF monotherapy. Therapeutic hypothermia has also been advocated for with other agents such as EPO, melanin, xenon, stem cells, and anticonvulsants with promising results. As most of these agents have controversial effectiveness in improving HI-induced brain injury and most of them are under clinical trials for efficacy and safety, at present, it appears that combination of these therapeutic agents with TH could be the promising intervention strategies to treat newborns suffering from HIE, while awaiting the outcomes of both preclinical and clinical trials that are under investigation.

In this review, we highlighted recent researches in the role of G-CSF in regulating cytokines and inhibition of apoptotic mediators, as well as promoting neurogenesis and angiogenesis thereby enhancing cell survival and proliferation, and modulation of inflammatory responses in the injured neonatal brain through activation of multistep signaling pathways.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- AIP

Apoptosis-inducing factor

- Akt

Protein kinase B

- Ang-1

Angiopoietin-1

- BAD

Bcl-2-antagonist of cell death

- BAX

Bcl-2-associated X protein

- BBB

Blood-brain barrier

- BLC-2

B cell lymphoma 2

- BDNF

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor

- cAMP

Cyclic adenosine monophosphate

- CC3

Cleaved caspase-3

- CNS

Central nervous system

- EE

Enriched environment

- EEG

Electroencephalogram

- EPCs

Endothelial progenitor cells

- EPO

Erythropoietin

- FL

Fms-related tyrosine kinase 3 ligand

- FLK-1

Fms-like tyrosine kinase 1

- GABA

Gamma-aminobutyric acid

- G-CSF

Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor

- G-CSFR

Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor receptor

- GDNF

Growth-derived neurotrophic factor

- GSK-3β

Glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta

- HI

Hypoxia ischemia

- HIE

Hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy

- HIF-1α

Hypoxia inducing factor-1 alpha

- HSCs

Hematopoietic stem cells

- hUCB

Human umbilical cord blood

- IAP

Inhibitor of apoptosis protein

- ICAM1

Intracellular adhesion molecule 1

- IL-1β

Interleukin-1 beta

- iNOS

Inducible nitric oxide synthase

- JAK

Janus kinase

- MAPK

Mitogen-associated protein kinase

- MHC

Major histocompatibility complex

- MMPs

Matrix metalloproteinases

- MMP-9

Matrix metalloproteinase-9

- MOMP

Mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization

- mTOR

Mammalian target of rapamycin

- NF-κB

Nuclear factor-kappa B

- NMDA

N-methyl-d-aspartic acid

- NO

Nitric oxide

- NVU

Neurovascular unit

- PI3K

Phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase

- PICs

Pro-inflammatory cytokines

- PDKI

Pyruvate dehydrogenase isoenzyme

- P70S6K

P70 ribosomal S6 protein kinase

- RCT

Randomized control trial

- SAEs

Severe adverse effects

- SCF

Stem cell factor

- STAT

Signal transducer and activator of transcription

- SVZ

Subventricular zone

- TBI

Traumatic brain injury

- TH

Therapeutic hypothermia

- TNF-α

Tumor necrosis factor alpha

- TRAIL

TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand

- UCB

Umbilical cord blood

- UC-MSCs

Umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells

- VCAM1

Vascular cell adhesion molecule 1

- VEGF

Vascular endothelial growth factor

Authors’ contributions

The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Nair J, Kumar VHS. Current and emerging therapies in the management of hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy in neonates. Children. 2018;5(7):99. doi: 10.3390/children5070099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dixon BJ, Reis C, Ho WM, Tang J, Zhang JH. Neuroprotective strategies after neonatal hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16(9):22368–22401. doi: 10.3390/ijms160922368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jelin AC, Salmeen K, Gano D, Burd I, Thiet MP. Perinatal neuroprotection update. F1000Res. 2016;5:F1000 Faculty Rev–1939. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.8546.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Riljak V, Kraf J, Daryanani A, Jiruška P, Otáhal J. Pathophysiology of perinatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy - biomarkers, animal models and treatment perspectives. Physiol Res. 2016;65(Suppl 5):S533–S545. doi: 10.33549/physiolres.933541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Qin X, Cheng J, Zhong Y, et al. Mechanism and treatment related to oxidative stress in neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. Front Mol Neurosci. 2019;12(88) Published 2019 Apr 11. 10.3389/fnmol.2019.00088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Zhao M, Zhu P, Fujino M, Zhuang J, Guo H, Sheikh I, Zhao L, Li XK. Oxidative stress in hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(12):2078. doi: 10.3390/ijms17122078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kochanek PM, Jackson TC, Ferguson NM, Carlson SW, Simon DW, Brockman EC, Ji J, Bayır H, Poloyac SM, Wagner AK, Kline AE, Empey PE, Clark RS, Jackson EK, Dixon CE. Emerging therapies in traumatic brain injury. Semin Neurol. 2015;35(1):83–100. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1544237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnston MV, Fatemi A, Wilson MA, Northington F. Treatment advances in neonatal neuroprotection and neurointensive care. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10(4):372–382. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70016-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arteaga O, Álvarez A, Revuelta M, Santaolalla F, Urtasun A, Hilario E. Role of antioxidants in neonatal hypoxic-ischemic brain injury: new therapeutic approaches. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(2):265. doi: 10.3390/ijms18020265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.James A, Patel V. Hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy. Paediatr Child Health. 2014;24:9. doi: 10.1016/j.paed.2014.02.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chalak LF, Sánchez PJ, Adams-Huet B, Laptook AR, Heyne RJ, Rosenfeld CR. Biomarkers for severity of neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy and outcomes in newborns receiving hypothermia therapy. J Pediatr. 2014;164(3):468–74.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.10.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Graham EM, Everett AD, Delpech JC, Northington FJ. Blood biomarkers for evaluation of perinatal encephalopathy: state of the art. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2018;30(2):199–203. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0000000000000591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mathur AM, Neil JJ, Inder TE. Understanding brain injury and neurodevelopmental disabilities in the preterm infant: the evolving role of advanced magnetic resonance imaging. Semin Perinatol. 2010;34(1):57–66. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2009.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Horn AR, Swingler GH, Myer L, et al. Early clinical signs in neonates with hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy predict an abnormal amplitude-integrated electroencephalogram at age 6 hours. BMC Pediatr. 2013;13:52. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-13-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abbasi H, Unsworth CP. Electroencephalogram studies of hypoxic ischemia in fetal and neonatal animal models. Neural Regen Res. 2020;15(5):828–837. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.268892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buonocore G, Perrone S, Turrisi G, Kramer BW, Balduini W. New pharmacological approaches in infants with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. Curr Pharm Design. 2012;18:3086. doi: 10.2174/1381612811209023086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singhi S, Johnston M. Recent advances in perinatal neuroprotection. F1000Res. 2019;8:F1000 Faculty Rev–2031. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.20722.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koehler RC, Yang ZJ, Lee JK, Martin LJ. Perinatal hypoxic-ischemic brain injury in large animal models: relevance to human neonatal encephalopathy. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2018;38(12):2092–2111. doi: 10.1177/0271678X18797328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dereymaeker A, Matic V, Vervisch J, et al. Automated EEG background analysis to identify neonates with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy treated with hypothermia at risk for adverse outcome: a pilot study. Pediatr Neonatol. 2019;60(1):50–58. doi: 10.1016/j.pedneo.2018.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Romeo DM, Bompard S, Serrao F, et al. Early neurological assessment in infants with hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy treated with therapeutic hypothermia. J Clin Med. 2019;8(8):1247. doi: 10.3390/jcm8081247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee CYZ, Chakranon P, Lee SWH. Comparative efficacy and safety of neuroprotective therapies for neonates with hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy: a network meta-analysis. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:1221. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2019.01221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Silveira RC, Procianoy RS. Hypothermia therapy for newborns with hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy. J Pediatr. 2015;91(6 Suppl 1):S78–S83. doi: 10.1016/j.jped.2015.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McDonald CA, Djuliannisaa Z, Petraki M, et al. Intranasal delivery of mesenchymal stromal cells protects against neonatal hypoxic ischemic brain injury. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(10):2449. doi: 10.3390/ijms20102449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reiss J, Sinha M, Gold J, Bykowski J, Lawrence SM. Outcomes of infants with mild hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy who did not receive therapeutic hypothermia. Biomed Hub. 2019;4(3):1–9. doi: 10.1159/000502936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang W, Zhu L, An C, et al. The blood brain barrier in cerebral ischemic injury – disruption and repair. Brain Hemorrhages. 2020;1:34–53. doi: 10.1016/j.hest.2019.12.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shankaran S, Laptook AR, Pappas A, et al. Effect of depth and duration of cooling on deaths in the NICU among neonates with hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;312(24):2629–2639. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.16058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wassink G, Davidson JO, Lear CA, et al. A working model for hypothermic neuroprotection. J Physiol. 2018;596(23):5641–5654. doi: 10.1113/JP274928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Calipari ES, Godino A, Peck EG, et al. Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor controls neural and behavioral plasticity in response to cocaine. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):9. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01881-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhou DG, Shi YH, Cui YQ. Impact of G-CSF on expressions of Egr-1 and VEGF in acute ischemic cerebral injury. Exp Ther Med. 2018;16(3):2313–2318. doi: 10.3892/etm.2018.6486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Doycheva DM, Hadley T, Li L, Applegate RL, 2nd, Zhang JH, Tang J. Anti-neutrophil antibody enhances the neuroprotective effects of G-CSF by decreasing number of neutrophils in hypoxic ischemic neonatal rat model. Neurobiol Dis. 2014;69:192–199. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2014.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.D’Souza A, Jaiyesimi I, Trainor L, Venuturumili P. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor administration: adverse events. Transfus Med Rev. 2008;22(4):280–290. doi: 10.1016/j.tmrv.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Molineux G. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factors. Cancer Treat Res. 2011;157:33–53. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-7073-2_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yata K, Matchett GA, Tsubokawa T, Tang J, Kanamaru K, Zhang JH. Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor inhibits apoptotic neuron loss after neonatal hypoxia-ischemia in rats. Brain Res. 2007;1145:227–238. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.01.144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang H, Zhang Q, Liu J, Hao H, Jiang C, Han W. Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) accelerates wound healing in hemorrhagic shock rats by enhancing angiogenesis and attenuating apoptosis. Med Sci Monit. 2017;23:2644–2653. doi: 10.12659/MSM.904988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wallner S, Peters S, Pitzer C, Resch H, Bogdahn U, Schneider A. The granulocyte-colony stimulating factor has a dual role in neuronal and vascular plasticity. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2015;3(48) 10.3389/fcell.2015.00048 PMID: 26301221; PMCID: PMC4528279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Kallmünzer B, Tauchi M, Schlachetzki JC, et al. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor does not promote neurogenesis after experimental intracerebral haemorrhage. Int J Stroke. 2014;9(6):783–788. doi: 10.1111/ijs.12217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vexler ZS, Yenari MA. Does inflammation after stroke affect the developing brain differently than adult brain? Dev Neurosci. 2009;31(5):378–393. doi: 10.1159/000232556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kamm K, Vanderkolk W, Lawrence C, Jonker M, Davis AT. The effect of traumatic brain injury upon the concentration and expression of interleukin-1beta and interleukin-10 in the rat. J Trauma. 2006;60(1):152–157. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000196345.81169.a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li T, Li K, Zhang S, et al. Overexpression of apoptosis inducing factor aggravates hypoxic-ischemic brain injury in neonatal mice. Cell Death Dis. 2020;11(1):77. doi: 10.1038/s41419-020-2280-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xiao BG, Lu CZ, Link H. Cell biology and clinical promise of G-CSF: immunomodulation and neuroprotection. J Cell Mol Med. 2007;11(6):1272–1290. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2007.00101.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Amirzagar N, Nafissi S, Tafakhori A, Modabbernia A, Amirzargar A, Ghaffarpour M, Siroos B, Harirchian MH. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of Iranian patients. J Clin Neurol. 2015;11(2):164–171. doi: 10.3988/jcn.2015.11.2.164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ziemka-Nalecz M, Jaworska J, Zalewska T. Insights into the neuroinflammatory responses after neonatal hypoxia-ischemia. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2017;76(8):644–654. doi: 10.1093/jnen/nlx046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pastuszko P, Schears GJ, Kubin J, Wilson DF, Pastuszko A. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor significantly decreases density of hippocampal caspase 3-positive nuclei, thus ameliorating apoptosis-mediated damage, in a model of ischaemic neonatal brain injury. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2017;25(4):600–605. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivx047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li YG, Liu XL, Zheng CB. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor regulates JNK pathway to alleviate damage after cerebral ischemia reperfusion. Chin Med J. 2013;126(21):4088–4092. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Modi J, Menzie-Suderam J, Xu H, et al. Mode of action of granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) as a novel therapy for stroke in a mouse model. J Biomed Sci. 2020;27(1):19. doi: 10.1186/s12929-019-0597-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Paprocka J, Kijonka M, Rzepka B, Sokół M. Melatonin in hypoxic-ischemic brain injury in term and preterm babies. Int J Endocrinol. 2019;2019:9626715. doi: 10.1155/2019/9626715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Robertson NJ, Martinello K, Lingam I, et al. Melatonin as an adjunct to therapeutic hypothermia in a piglet model of neonatal encephalopathy: a translational study. Neurobiol Dis. 2019;121:240–251. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2018.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zareen Z, Strickland T, Eneaney VM, et al. Cytokine dysregulation persists in childhood post neonatal encephalopathy. BMC Neurol. 2020;20(1):115. doi: 10.1186/s12883-020-01656-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thornton C, Leaw B, Mallard C, Nair S, Jinnai M, Hagberg H. Cell death in the developing brain after hypoxia-ischemia. Front Cell Neurosci. 2017;11:248. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2017.00248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li L, McBride DW, Doycheva D, et al. G-CSF attenuates neuroinflammation and stabilizes the blood-brain barrier via the PI3K/Akt/GSK-3β signaling pathway following neonatal hypoxia-ischemia in rats. Exp Neurol. 2015;272:135–144. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2014.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sabir H, Osredkar D, Maes E, Wood T, Thoresen M. Xenon combined with therapeutic hypothermia is not neuroprotective after severe hypoxia-ischemia in neonatal rats. PLoS One. 2016;11(6):e0156759. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0156759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.King D, Yeomanson D, Bryant HE. PI3King the lock: targeting the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway as a novel therapeutic strategy in neuroblastoma. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2015;37(4):245–251. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0000000000000329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.McCollum M, Ma Z, Cohen E, et al. Post-MPTP treatment with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor improves nigrostriatal function in the mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. Mol Neurobiol. 2010;41(2-3):410–419. doi: 10.1007/s12035-010-8118-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Meuer K, Pitzer C, Teismann P, et al. Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor is neuroprotective in a model of Parkinson’s disease. J Neurochem. 2006;97(3):675–686. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03727.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wu J-Y, Modi J, Menzie J, Chou HY, Tao R, Morrell A, Trujillo P, Medley K, Altamimi A, Jasica Shen J, Prentice H. Granulocyte colony stimulating factor (GCSF) gene therapy in stroke and Alzheimer’s disease model. J Neurol Exp Neurosci. 2018;4(Supplement 1):S17. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lee ST, Chu K, Jung KH, Ko SY, Kim EH, Sinn DI, Lee YS, Lo EH, Kim M, Roh JK. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor enhances angiogenesis after focal cerebral ischemia. Brain Res. 2005;1058(1-2):120–128. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.07.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sun BL, He MQ, Han XY, Sun JY, Yang MF, Yuan H, Fan CD, Zhang S, Mao LL, Li DW, Zhang ZY, Zheng CB, Yang XY, Li YV, Stetler RA, Chen J, Zhang F. Intranasal delivery of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor enhances its neuroprotective effects against ischemic brain injury in rats. Mol Neurobiol. 2016;53(1):320–330. doi: 10.1007/s12035-014-8984-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hasselblatt M, Jeibmann A, Riesmeier B, Maintz D, Schäbitz WR. Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) and G-CSF receptor expression in human ischemic stroke. Acta Neuropathol. 2007;113(1):45–51. doi: 10.1007/s00401-006-0152-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schäbitz WR, Laage R, Vogt G, et al. AXIS: a trial of intravenous granulocyte colony-stimulating factor in acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2010;41(11):2545–2551. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.579508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ringelstein EB, Thijs V, Norrving B, et al. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor in patients with acute ischemic stroke: results of the AX200 for Ischemic Stroke trial. Stroke. 2013;44(10):2681–2687. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.001531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chen WF, Hsu JH, Lin CS, et al. Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor alleviates perinatal hypoxia-induced decreases in hippocampal synaptic efficacy and neurogenesis in the neonatal rat brain. Pediatr Res. 2011;70(6):589–595. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3182324424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Popa-Wagner A, Stöcker K, Balseanu AT, Rogalewski A, Diederich K, Minnerup J, Margaritescu C, Schäbitz WR. Effects of granulocyte-colony stimulating factor after stroke in aged rats. Stroke. 2010;41(5):1027–1031. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.575621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kim BR, Shim JW, Sung DK, et al. Granulocyte stimulating factor attenuates hypoxic-ischemic brain injury by inhibiting apoptosis in neonatal rats. Yonsei Med J. 2008;49(5):836–842. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2008.49.5.836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Huang X, Liu Y, Bai S, Peng L, Zhang B, Lu H. Granulocyte colony stimulating factor therapy for stroke: a pairwise meta-analysis of randomized controlled trial. PLoS One. 2017;12(4):e0175774. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0175774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sun Y, Calvert JW, Zhang JH. Neonatal hypoxia/ischemia is associated with decreased inflammatory mediators after erythropoietin administration. Stroke. 2005;36(8):1672–1678. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000173406.04891.8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Borjini N, Sivilia S, Giuliani A, et al. Potential biomarkers for neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration at short and long term after neonatal hypoxic-ischemic insult in rat. J Neuroinflammation. 2019;16(1):194. doi: 10.1186/s12974-019-1595-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Aslam S, Molloy EJ. Biomarkers of multiorgan injury in neonatal encephalopathy. Biomark Med. 2015;9(3):267–275. doi: 10.2217/bmm.14.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yang YN, Su YT, Wu PL, et al. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor alleviates bacterial-induced neuronal apoptotic damage in the neonatal rat brain through epigenetic histone modification. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2018;2018:9797146. doi: 10.1155/2018/9797146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sisa C, Agha-Shah Q, Sanghera B, Carno A, Stover C, Hristova M. Properdin: a novel target for neuroprotection in neonatal hypoxic-ischemic brain injury. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2610. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Welcome MO. Neuroinflammation in CNS diseases: molecular mechanisms and the therapeutic potential of plant derived bioactive molecules. Pharma Nutr. 2020;11:100176. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Liu F, McCullough LD. Inflammatory responses in hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2013;34(9):1121–1130. doi: 10.1038/aps.2013.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chaparro-Huerta V, Flores-Soto ME, Merin Sigala ME, et al. Proinflammatory cytokines, enolase and S-100 as early biochemical indicators of hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy following perinatal asphyxia in newborns. Pediatr Neonatol. 2017;58(1):70–76. doi: 10.1016/j.pedneo.2016.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Boneberg EM, Hartung T. Molecular aspects of anti-inflammatory action of G-CSF. Inflamm Res. 2002;51(3):119–128. doi: 10.1007/PL00000283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dumbuya JS, Chen L, Shu SY, et al. G-CSF attenuates neuroinflammation and neuronal apoptosis via the mTOR/p70SK6 signaling pathway in neonatal hypoxia-ischemia rat model. Brain Res. 2020;1739:146817. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2020.146817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Peng W. Neuroprotective effects of G-CSF administration in microglia-mediated reactive T cell activation in vitro. Immunol Res. 2017;65(4):888–902. doi: 10.1007/s12026-017-8928-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Jellema RK, Lima Passos V, Zwanenburg A, et al. Cerebral inflammation and mobilization of the peripheral immune system following global hypoxia-ischemia in preterm sheep. J Neuroinflammation. 2013;10:13. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-10-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Li L, Klebe D, Doycheva D, et al. G-CSF ameliorates neuronal apoptosis through GSK-3β inhibition in neonatal hypoxia-ischemia in rats. Exp Neurol. 2015;263:141–149. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2014.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Schlager GW, Griesmaier E, Wegleiter K, et al. Systemic G-CSF treatment does not improve long-term outcomes after neonatal hypoxic-ischaemic brain injury. Exp Neurol. 2011;230(1):67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2010.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Prasad K, Kumar A, Sahu JK, et al. Mobilization of stem cells using G-CSF for acute ischemic stroke: a randomized controlled, pilot study. Stroke Res Treat. 2011;2011:283473. doi: 10.4061/2011/283473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.England TJ, Sprigg N, Alasheev AM, et al. Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) for stroke: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2016;6:36567. doi: 10.1038/srep36567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Keller M, Simbruner G, Górna A, et al. Systemic application of granulocyte-colony stimulating factor and stem cell factor exacerbates excitotoxic brain injury in newborn mice. Pediatr Res. 2006;59(4 Pt 1):549–553. doi: 10.1203/01.pdr.0000205152.38692.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zhang Y, Wang L, Fu Y, Song H, Zhao H, Deng M, Zhang J, Fan D. Preliminary investigation of effect of granulocyte colony stimulating factor on amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2009;10(5-6):430–431. doi: 10.3109/17482960802588059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Duning T, Schiffbauer H, Warnecke T, Mohammadi S, Floel A, Kolpatzik K, Kugel H, Schneider A, Knecht S, Deppe M, Schäbitz WR. G-CSF prevents the progression of structural disintegration of white matter tracts in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a pilot trial. PLoS One. 2011;6(3):e17770. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Fathali N, Lekic T, Zhang JH, Tang J. Long-term evaluation of granulocyte-colony stimulating factor on hypoxic-ischemic brain damage in infant rats. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36(9):1602–1608. doi: 10.1007/s00134-010-1913-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sarosiek KA, Chi X, Bachman JA, et al. BID preferentially activates BAK while BIM preferentially activates BAX, affecting chemotherapy response. Mol Cell. 2013;51(6):751–765. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.08.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lilly M, Sandholm J, Cooper JJ, Koskinen PJ, Kraft A. The PIM-1 serine kinase prolongs survival and inhibits apoptosis-related mitochondrial dysfunction in part through a bcl-2-dependent pathway. Oncogene. 1999;18(27):4022–4031. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Thornton C, Hagberg H. Role of mitochondria in apoptotic and necroptotic cell death in the developing brain. Clin Chim Acta. 2015;451(Pt A):35–38. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2015.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Chipuk JE, Moldoveanu T, Llambi F, Parsons MJ, Green DR. The BCL-2 family reunion. Mol Cell. 2010;37(3):299–310. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Charles MS, Ostrowski RP, Manaenko A, Duris K, Zhang JH, Tang J. Role of the pituitary–adrenal axis in granulocyte-colony stimulating factor-induced neuroprotection against hypoxia–ischemia in neonatal rats. Neurobiol Dis. 2012;47(1):29–37. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2012.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Faivre S, Decaens T. Raymond E. mTOR and cancer therapy: clinical development and novel prospects. In: Polunovsky VA, Houghton PJ, editors. mTOR Pathway and mTOR inhibitors in Cancer therapy, Cancer drug discovery and development. 2010. pp. 133–148. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Huang S, Wang H, Turlova E, et al. GSK-3β inhibitor TDZD-8 reduces neonatal hypoxic-ischemic brain injury in mice. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2017;23(5):405–415. doi: 10.1111/cns.12683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.King TD, Bijur GN, Jope RS. Caspase-3 activation induced by inhibition of mitochondrial complex I is facilitated by glycogen synthase kinase-3beta and attenuated by lithium. Brain Res. 2001;919(1):106–114. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(01)03005-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Solaroglu I, Cahill J, Tsubokawa T, Beskonakli E, Zhang JH. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor protects the brain against experimental stroke via inhibition of apoptosis and inflammation. Neurol Res. 2009;31(2):167–172. doi: 10.1179/174313209X393582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Solaroglu I, Tsubokawa T, Cahill J, Zhang JH. Anti-apoptotic effect of granulocyte-colony stimulating factor after focal cerebral ischemia in the rat. Neuroscience. 2006;143(4):965–974. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Yang YN, Lin CS, Yang CH, Lai YH, Wu PL, Yang SN. Neurogenesis recovery induced by granulocyte-colony stimulating factor in neonatal rat brain after perinatal hypoxia. Pediatr Neonatol. 2013;54(6):380–388. doi: 10.1016/j.pedneo.2013.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Yang DY, Chen YJ, Wang MF, Pan HC, Chen SY, Cheng FC. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor enhances cellular proliferation and motor function recovery on rats subjected to traumatic brain injury. Neurol Res. 2010;32(10):1041–1049. doi: 10.1179/016164110X12807570510013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Song S, Kong X, Acosta S, Sava V, Borlongan C, Sanchez-Ramos J. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor promotes behavioral recovery in a mouse model of traumatic brain injury. J Neurosci Res. 2016;94(5):409–423. doi: 10.1002/jnr.23714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Sevimli S, Diederich K, Strecker JK, Schilling M, Klocke R, Nikol S, Kirsch F, Schneider A, Schäbitz WR. Endogenous brain protection by granulocyte-colony stimulating factor after ischemic stroke. Exp Neurol. 2009;217(2):328–335. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Adams RH, Alitalo K. Molecular regulation of angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8(6):464–478. doi: 10.1038/nrm2183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Trollmann R, Gassmann M. The role of hypoxia-inducible transcription factors in the hypoxic neonatal brain. Brain Dev. 2009;31(7):503–509. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Liang X, Liu X, Lu F, Zhang Y, Jiang X, Ferriero DM. HIF1α signaling in the endogenous protective responses after neonatal brain hypoxia-ischemia. Dev Neurosci. 2019:1–10 10.1159/000495879 [published online ahead of print, 2019 Mar 5]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 102.Hong Y, Deng C, Zhang J, Zhu J, Li Q. Neuroprotective effect of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor in a focal cerebral ischemic rat model with hyperlipidemia. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technolog Med Sci. 2012;32(6):872–878. doi: 10.1007/s11596-012-1050-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Zhou S, Yin DP, Wang Y, Tian Y, Wang ZG, Zhang JN. Dynamic changes in growth factor levels over a 7-day period predict the functional outcomes of traumatic brain injury. Neural Regen Res. 2018;13(12):2134–2140. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.241462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Larpthaveesarp A, Ferriero DM, Gonzalez FF. Growth factors for the treatment of ischemic brain injury (growth factor treatment) Brain Sci. 2015;5(2):165–177. doi: 10.3390/brainsci5020165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Yu JH, Seo JH, Lee JE, Heo JH, Cho SR. Time-dependent effect of combination therapy with erythropoietin and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor in a mouse model of hypoxic-ischemic brain injury. Neurosci Bull. 2014;30(1):107–117. doi: 10.1007/s12264-013-1397-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]