Abstract

Fast oxidation of proteins (FPOP) is a hydroxyl radical protein footprinting (HRPF) method used to study protein structure, protein-ligand interactions, and protein-protein interactions. FPOP utilizes a KrF excimer laser at 248 nm for photolysis of hydrogen peroxide to generate hydroxyl radicals which in turn oxidatively modify solvent-accessible amino acid side chains. Recently, we expanded the use of FPOP of in vivo oxidative labeling in Caenorhabditis elegans (C. elegans), entitled IV-FPOP. The transparent nematodes have been used as model systems for many human diseases. Structural studies in C. elegans by IV-FPOP is feasible because of the animal’s ability to uptake hydrogen peroxide, their transparency to laser irradiation at 248 nm, and the irreversible nature of the modification. The assembly of a microfluidic flow system for IV-FPOP labeling, IV-FPOP parameters, protein extraction, and LC-MS/MS optimized parameters are described herein.

Keywords: Biochemistry, Issue 158, Caenorhabditis elegans, hydroxyl radical protein footprinting, FPOP, mass spectrometry, in vivo, proteomics

Introduction

Protein footprinting coupled to mass spectrometry (MS) has been used in recent years to study protein interactions and conformational changes. Hydroxyl radical protein footprinting (HRPF) methods probe protein solvent accessibility by modifying protein amino acid side chains. The HRPF method, fast photochemical oxidation of proteins (FPOP)1, has been used to probe protein structure in vitro2, in-cell (IC-FPOP)3, and most recently in vivo (IV-FPOP)4. FPOP utilizes a 248 nm wavelength excimer laser in order to rapidly generate hydroxyl radicals by photolysis of hydrogen peroxide to form hydroxyl radicals1. In turn, these radicals can label 19 out of 20 amino acids on a microsecond time scale, faster than proteins can unfold. Although, the reactivity of each amino acid with hydroxyl radicals extends 1000-fold, it is possible to normalize side chain oxidation by calculating a protection factor (PF)5.

Since FPOP can oxidatively modify proteins regardless of their size or primary sequence, it proves to be advantageous for in-cell and in vivo protein studies. IV-FPOP probes protein structure in C. elegans similarly to in vitro and in-cell studies4. C. elegans are part of the nematode family and are widely used as a model to study human diseases. The ability of the worm to uptake hydrogen peroxide by both passive and active diffusion allows for the study of protein structure in different body systems. In addition, C. elegans are suited for IV-FPOP due to their transparency at the 248 nm laser wavelength needed for FPOP6. Coupling of this method to mass spectrometry allows for the identification of multiple modified proteins using traditional bottom-up proteomics approaches.

In this protocol, we describe how to perform IV-FPOP for the analysis of protein structure in C. elegans. The experimental protocol requires the assembly and set-up of microfluidic flow system for IV-FPOP adapted from Konermann et al7. After IV-FPOP, samples are homogenized for protein extraction. Protein samples are proteolyzed and peptides are analyzed by liquid chromatograph (LC) tandem MS, followed by quantification.

Protocol

1. C. elegans maintenance and culture

Grow and synchronize worms colonies to their fourth larvae (L4) stage following standard laboratory procedures8.

The day of IV-FPOP experiment, wash L4 worms from bacterial lawns (OP50 E. coli) with M9 buffer (0.02 M KH2PO4, 0.08 M Na2HPO4, 0.08 M NaCl, 1 mM MgSO4).

Obtain 500 μL aliquots of ~10,000 worms per IV-FPOP sample.

2. Microfluidic flow system assembly

Start the flow system assembly by cutting a 2 cm piece of fluorinated ethylene propylene (FEP) tubing (1/16 in. outer diameter (o.d.) × 0.020 in. inner diameter (i.d.)).

-

Using a clean dissecting needle, widen the i.d. of the FEP tubing in order to make a small crater at one end only, ~50 mm in length. The crater should be big enough to fit two 360 μm o.d. pieces of fused silica.

NOTE: Do not widen the opposite end as this end will only be used to fit the outlet capillary.

With a ceramic cutter, cut two 15 cm pieces of 250 μm i.d. fused silica. These two pieces will become the infusing lines of the flow system.

-

Using self-adhesive tape, tape the two 250 μm i.d. capillaries together ensuring they are parallel to each other and their ends are 100% flushed.

NOTE: To ensure the fused silica ends are not crushed after cutting, and are straight and 100% flushed against each other, it is recommended to examine them using a magnifying glass or under a stereo microscope.

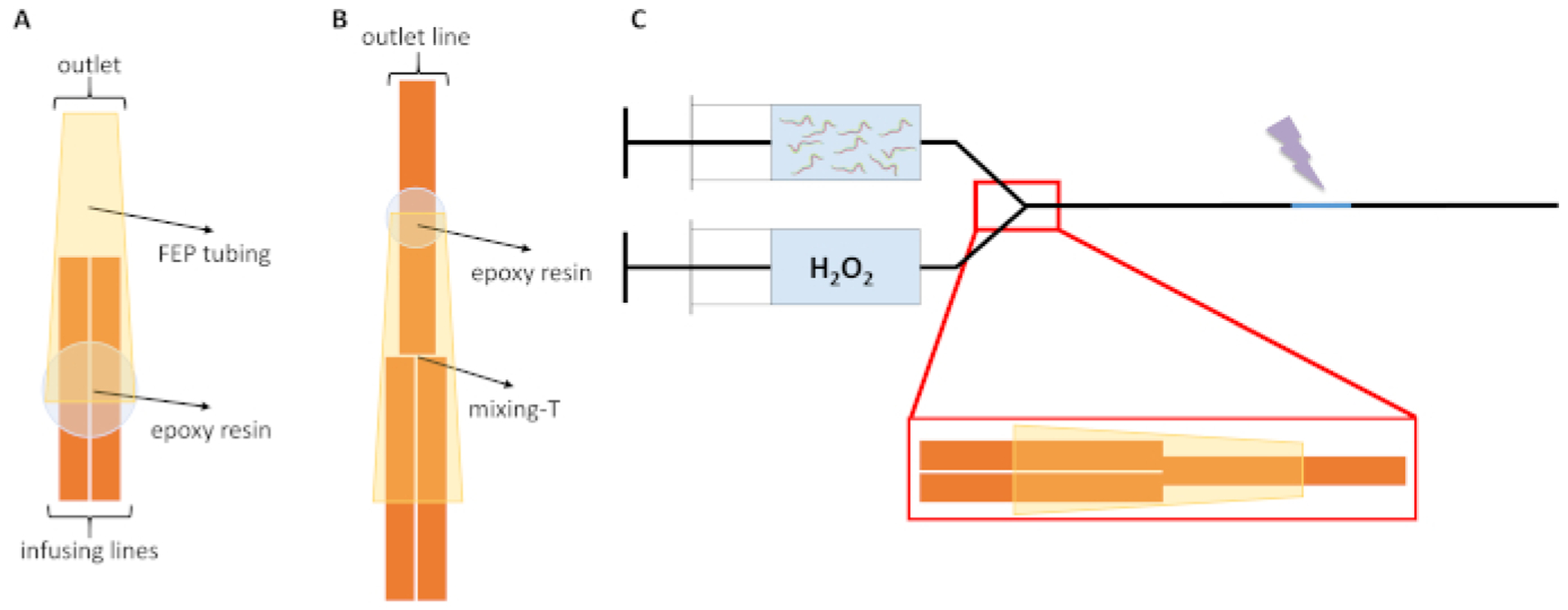

Insert the two taped capillaries into the handmade crater of the FEP tubing. Push the capillaries up to the very edge of the handmade crater. CAUTION: To maintain the efficacy of the flow system, do not push past the handmade crater (Figure 1a).

Place a small dot of epoxy resin on a clean surface and mix with a dissecting needle.

Quickly, using the same needle, place a small drop of resin at the end of the infusing capillaries where they connect with the FEP tubing and allow the resin to dry, hanging outlet-side up, for a few minutes (Figure 1a).

-

While the resin dries, binding the FEP tubing and two capillaries together, cut a new 250 μm i.d. capillary. The new capillary will become the outlet capillary of the flow system. The desired length of the capillary can be calculated using the equation below:

Where ℓ is length of the capillary to be cut in centimeters, t is the desired reaction time in minutes, f is the flow rate in mL/min, and i.d. is the inner diameter of the capillary in centimeters.

NOTE: After cutting the outlet capillary, examine the ends ensuring they are straight and not crushed.

Once the resin has dried, insert the new capillary through the FEP tubing outlet end. The inside ends of the outlet capillary and the two infusing capillaries should be flush against each other inside the FEP tubing, this creates the mixing-T (Figure 1b).

Bind the outlet capillary and FEP tubing with fresh epoxy resin as described in steps 2.6 and 2.7.

Allow the resin to dry overnight binding the flow system together. Set up the microfluidic flow system the next day (Figure 1c).

Figure 1. In vivo FPOP microfluidic flow system schematic.

(A) The two infusing lines (orange) of the IV-FPOP flow system are shown inside the FEP tubing (yellow), the correct binding position of the epoxy resin is represented by the light blue circle. (B) Complete assembled mixing-T formed by the three 250 μm i.d. capillaries. The correct resin binding position of the outlet capillary to the FEP tubing is represented by the light blue circle. (C) The complete assembled flow system for in vivo covalent labeling of C. elegans. Prior to FPOP, worms are kept separated from H2O2 until just prior to labeling; the laser irradiation window is shown in light blue and the laser beam is represented by the purple lightning bolt. Figures are not to scale. This figure has been modified from Espino et al.4.

3. Microfluidic flow system for in vivo FPOP

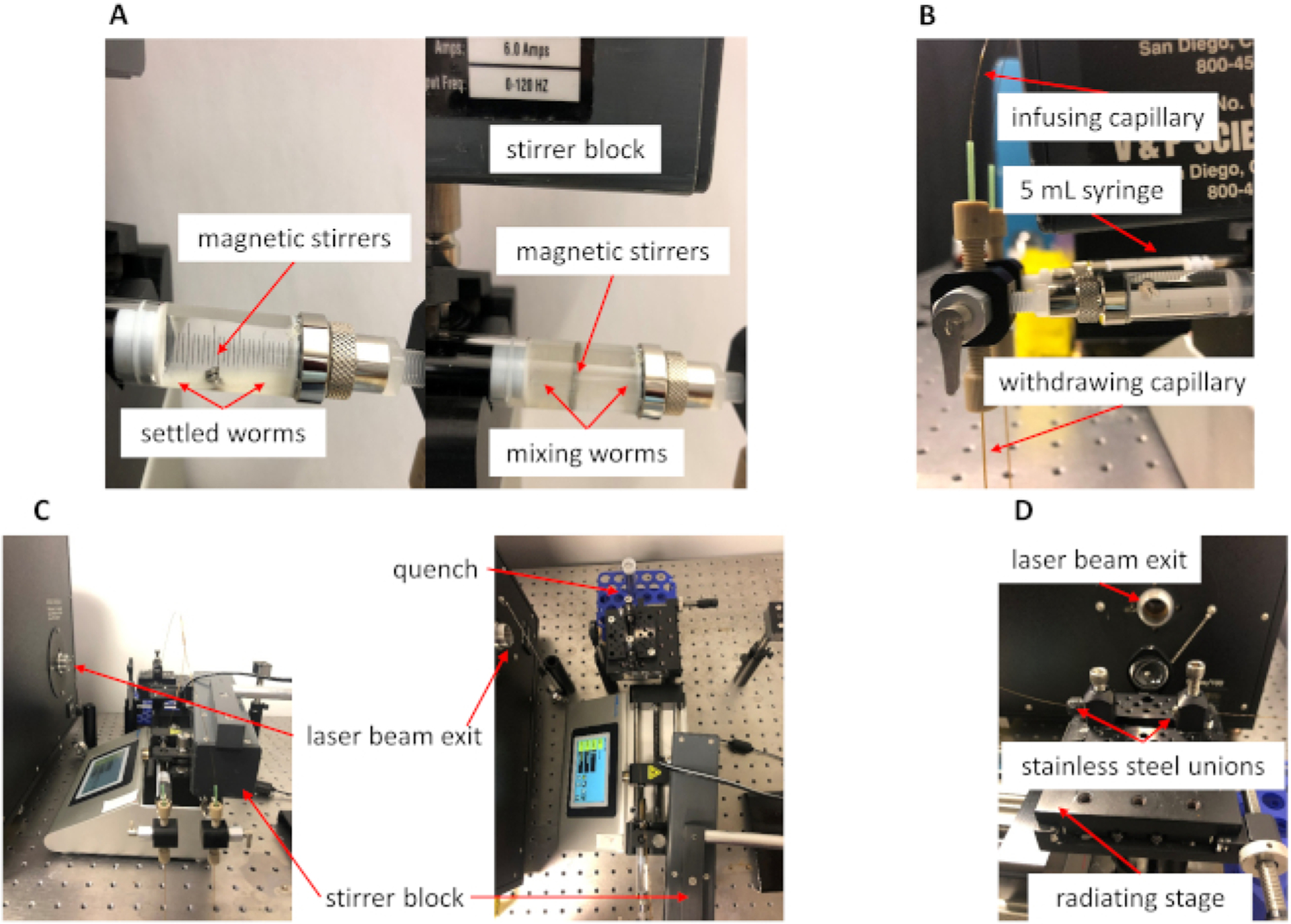

Insert four magnetic stirrers inside one 5 mL syringe. This syringe becomes the sample syringe. The magnetic stirrers prevent the worms from settling inside the syringe during IV-FPOP (Figure 2A).

Fill the two 5 mL syringes with M9. Make sure there are no air bubbles inside each syringe as they can affect the flow rate and mixing efficiency.

Connect a Luer adapter to each 5 mL syringe ensuring they are finger tight and secured in place.

Attach each syringe to a single 3–2 valve. The syringe should be attached to the middle port of the valve (Figure 2B).

Secure each 5 mL syringe to the dual syringe pump and adjust the mechanical stop collar to prevent over pressure to the syringe from the pusher block. Keep in mind the addition of the magnetic stirrers when setting the stop collar.

Attach each infusing capillary end of the homemade microfluidic flow system to the top port of each 3–2 valve using a super flangeless nut, FEP sleeve, and super flangeless ferrule (Figure 2B).

To the remaining opened port of the 3–2 valve (bottom port), attach a 10 cm 450 μm i.d. capillary using a super flangeless nut, FEP sleeve, and super flangeless ferrule (Figure 2B). These capillaries become the withdrawing sample capillaries.

-

Start the pump flow and check all connections of the microfluidic flow system for visual leaks. Flow at least three syringe volumes using the experimental flow rate. The final flow rate is dependent on the laser irradiation window, laser frequency, and a zero-exclusion fraction volume.

NOTE: For this protocol, a final flow rate of 375.52 μL/min was calculated from a laser irradiation window of 2.55 mm, 250 μm i.d. fused silica, zero exclusion fraction, and 50 Hz frequency.-

The flow path is marked by the arrows on the 3–2 valve handle. Each syringe can be refilled manually by moving the valve handle from the expelling position to the withdrawing position.NOTE: Leaks at the 3–2 valve can be fixed by re-screwing the super flangeless nut or replacing any of the valve connections (super flangeless nut, FEP sleeve, or super flangeless ferrule). Leaks at the mixing-T require a reassembly of the microfluidic flow system (steps 2.1 to 2.11).

-

Move the microfluidic flow system to the experimental bench and secure the outlet capillary to the radiating stage using a 360 μm o.d. stainless steel union (Figure 2C,D).

-

Using a long-reach lighter, burn the coating of the fused silica at the laser irradiation window. Clean the burned coating using lint-free tissue and methanol.

NOTE: Alternate between burning cycles and methanol cleaning cycles to avoid over-heating the capillary as excess heat can melt and/or break the capillary.

Position the magnetic stirrer block above the 5 mL syringe containing the magnetic stirrers. Adjust the speed and position of the magnetic stirrer block so that the magnetic stirrers inside the 5 mL syringe are rotating slowly and constantly.

Figure 2. Microfluidic system during IV-FPOP.

(A) Representative picture of C. elegans inside the 5 mL syringe. Without stirring, the worms settle at the bottom of the syringe (left). The magnetic stirrers and stirrer block keep the worms in suspension during the IV-FPOP experiments (right). (B) Representative picture of a 5 mL syringe, infusing capillary, and withdrawing capillary connected to the 3–2 valve. The 3–2 valve handle is shown in the withdrawing position. (C) Microfluidic flow system during IV-FPOP, the magnetic stirrer block is position above the worms’ 5 mL syringe. (D) Outlet capillary secured to the radiating stage.

4. In vivo FPOP

-

Turn on the KrF excimer laser and allow the thyratron to warm-up.

CAUTION: The laser emits visible and invisible radiation at 248 nm wavelength that can damage eyes. Proper eye protection should be worn before turning on the laser and opening the beam exit window.

-

Measure the laser energy at a frequency of 50 Hz for at least 100 pulses by placing the optical sensor at the beam exit window.

NOTE: For this protocol, a 2.55 mm irradiation window was used with a laser energy of 150 ± 2.32 mJ.

Obtain approximatively 10,000 worms (500 μL) and manually withdraw the sample into the sample syringe.

Fill the sample syringe with 2.5 mL of M9 buffer for a final sample volume of 3 mL. Make sure that no air bubbles are introduced into the sample syringe.

Fill the second syringe with 3 mL of 200 mM H2O2, again ensuring no air bubbles are introduced into the syringe.

At the end of the outlet capillary, place a 15 mL conical tube wrapped in aluminum foil containing 6 mL of 40 mM N’-Dimethylthiourea (DMTU), 40 mM N-tert-Butyl-α-phenylnitrone (PBN), and 1% dimethyl sulfoxide to quench excess H2O2, hydroxyl radicals, and inhibit methionine sulfoxide reductase activity, respectively.

-

Start the excimer laser from the software window, wait for the first pulse, and start the sample flow from the dual syringe.

NOTE: Samples should be run in biological duplicates in technical triplicates under 3 samples conditions: laser irradiation with H2O2 (sample), no laser irradiation with H2O2 and no laser irradiation no H2O2 (controls), totaling to 9 samples per biological set.

Collect the entire sample in the 15 mL tube, while actively monitoring the sample flow for any visual leaks as some back pressure from the sample syringe can sometimes build-up.

Following IV-FPOP, pellet worms by centrifugation at 805 × g for 2 min. Remove quench solution, add 250 μL of lysis buffer (8 M urea, 0.5% SDS, 50 mM HEPES, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF]). Transfer the sample to a clean microcentrifuge tube, flash freeze, and store at −80 °C until sample digestion.

5. Protein extraction, purification, and proteolysis

Thaw frozen samples on ice and homogenize by sonication for 10 s, followed by a 60 s ice incubation. Multiple rounds of sonication may be required, homogenate can be observed under a stereomicroscope by placinga 2 μL sample aliquot on a microscope slide. Sample homogenization is complete when small to no pieces of worms are seen.

Centrifuge homogenized worms at 400 × g for 5 min at 4 °C and collect the supernatant into a clean microcentrifuge tube.

-

Determine sample protein concentrations using a bicinchoninic acid assay (BCA assay) using the manufacturer’s instructions.

NOTE: Sample concentration can be determined using any biochemical protein concentration assay of choice. Keep in mind reagent compatibility with lysis buffer (8 M urea, 0.5% SDS, 50 mM HEPES, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM PMSF). Additionally, a buffer dilution may be necessary.

Obtain 100 μg of protein from each sample and place in clean microcentrifuge tubes.

Add dithiothreitol (DTT) to a 10 mM final concentration to reduce disulfide bonds in allsamples. Vortex, spindown, and incubate samples at 50 °C for 45 min.

Cool samples to room temperature for 10 min.

Add iodoacetamide (IAA) to a 50 mM final concentration to alkylate reduced residues. Vortex, spin down, and incubate sample for 20 min at room temperature protected from light.

Immediately after alkylation, precipitate the protein sample by adding 4 volumes of 100% pre-chilled acetone and incubate at −20 °C overnight.

The next day, pellet protein precipitate by centrifugation at 16,000 × g for 10 min. Wash sample pellet with 90% acetone, remove supernatant, and allow pellet to dry for 2–3 min.

Re-suspend the protein pellet in 25 mM Tris-HCl (1 μg/μL). Add trypsin at a final protease to protein ratio of 1:50 (w/w) and digest samples at 37 °C overnight.

-

The next day quench the trypsin digestion reaction by adding 5% formic acid.

NOTE: A minimum of 0.5 μg of peptides per sample is needed for LC-MS/MS analysis (steps 6.1–6.5). Determine sample peptide concentrations using a quantitative colorimetric peptide assay (see the Table of Materials) as described by the manufacturer’s protocol.

Materials

| Name | Company | Catalog Number | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| 15mL Conical Centrifuge Tubes | Fisher Scientific | 14-959-53A | any brand is sufficient |

| 5 mL Gas Tight Syringe, Removable Luer Lock | SGE Analytical Science | 008760 | 2 minimum |

| 60 Sonic Dismembrator | Fisher Scientific | FM3279 | This item is no longer available. Any low-volume sonicator will be sufficient |

| Acetone, HPLC Grade | Fisher Scientific | A929-4 | 4 L quantity is not necessary |

| Acetonitrile with 0.1% Formic Acid (v/v), LC/MS Grade | Fisher Scientific | LS120-500 | |

| ACQUITY UPLC M-Class Symmetry C18 Trap Column, 100Å, 5 μm, 180 μm × 20 mm, 2G, V/M, 1/pkg | Waters | 186007496 | |

| ACQUITY UPLC M-Class System | Waters | ||

| Aluminum Foil | Fisher Scientific | 01-213-100 | any brand is sufficient |

| Aqua 5 μm C18 125 Å packing material | Phenomenex | ||

| Centrifuge | Eppendorf | 022625501 | |

| Delicate Task Wipers | Fisher Scientific | 06-666A | |

| Dissecting Needle | Fisher Scientific | 50-822-525 | only a couple are needed |

| Dithiothreiotol (DTT) | AmericanBio | AB00490-00005 | |

| DMSO, Anhydrous | Invitrogen | D12345 | |

| Epoxy instant mix 5 minute | Loctite | 1365868 | |

| Ethylenediaminetetraaceti c acid (EDTA) | Fisher Scientific | S311-100 | |

| EX350 excimer laser (248 nm wavelength) | GAM Laser | ||

| FEP Tubing 1/16” OD × 0.020” ID | IDEX Health & Sciene | 1548L | |

| Formic Acid, LC/MS Grade | Fisher Scientific | A117-50 | |

| HEPES | Fisher Scientific | BP310-500 | |

| HV3-2 VALVE | Hamilton | 86728 | 2 minimum |

| Hydrochloric Acid | Fisher Scientific | A144S-500 | |

| Hydrogen Peroxide | Fisher Scientific | H325-100 | any 30% hydrogen peroxide is sufficient |

| lodoacetamide (IAA) | ACROS Organics | 122270050 | |

| Legato 101 syringe pump | KD Scientific | 788101 | |

| Luer Adapter Female Luer to 1/4-28 Male Polypropylene | IDEX Health & Sciene | P-618L | 2 minimum |

| Magnesium Sulfate | Fisher Scientific | M65-500 | |

| Methanol, LC/MS Grade | Fisher Scientific | A454SK-4 | 4 L quantity is not necessary |

| Microcentrifuge | Thermo Scientific | 75002436 | |

| N,N’-Dimethylthiourea (DMTU) | ACROS Organics | 116891000 | |

| NanoTight Sleeve Green 1/16” ID × .0155” ID ×1.6”’ | IDEX Health & Sciene | F-242X | |

| NanoTight Sleeve Yellow 1/16” OD × 0.027” ID × 1.6” | IDEX Health & Sciene | F-246 | |

| N-tert-Butyl-α-phenylnitrone (PBN) | ACROS Organics | 177350250 | |

| OmniPur Phenylmethyl Sulfonyl Fluoride (PMSF) | Sigma-Aldrich | 7110-OP | any protease inhibitor is sufficient |

| Orbitrap Fusion Lumos Tribrid Mass Spectrometer | Thermo Scientific | other high resolution instruments (e.g. Q exactive Orbitrap or Orbitrap Fusion) can be used | |

| PE50-C pyroelectric energy meter | Ophir Optronics | 7Z02936 | |

| Pierce Quantitative Colorimetric Peptide Assay | Thermo Scientific | 23275 | |

| Pierce Rapid Gold BCA Protein Assay Kit | Thermo Scientific | A53225 | |

| Pierce Trypsin Protease, MS Grade | Thermo Scientific | 90058 | |

| Polymicro Cleaving Stone, 1” × 1” × 1/32” | Molex | 1068680064 | any capillary tubing cutter is sufficient |

| Polymicro Flexible Fused Silica Capillary Tubing, Inner Diameter 250μm, Outer Diameter 350μm, TSP250350 | Polymicro Technologies | 1068150026 | |

| Polymicro Flexible Fused Silica Capillary Tubing, Inner Diameter 450μm, Outer Diameter 670μm, TSP450670 | Polymicro Technologies | 1068150625 | |

| Polymicro Flexible Fused Silica Capillary Tubing, Inner Diameter 75μm, Outer Diameter 375μm, TSP075375 | Polymicro Technologies | 1068150019 | |

| Potassium Phosphate Monobasic | Fisher Scientific | P382-500 | |

| Proteome Discover (bottom-up proteomics software) | Thermo Scientific | OPTON-30799 | |

| Rotary Magnetic Tumble Stirrer | V&P Scientific, Inc. | VP710D3 | |

| Rotary Magnetic Tumble Stirrer, accessory kit for use with Syringe Pumps | V&P Scientific, Inc. | VP 710D3-4 | |

| Scissors | Fisher Scientific | 50-111-1315 | any scissors are sufficient |

| Self-Adhesive Label Tape | Fisher Scientific | 15937 | one roll is sufficient |

| Snap-Cap Microcentrifuge Flex-Tube Tubes | Fisher Scientific | 05-402 | any brand is sufficient |

| Sodium Chloride | Fisher Scientific | S271-500 | |

| Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) | Fisher Scientific | 15-525-017 | |

| Sodium Phosphate Dibasic Heptahydrate | Fisher Scientific | S373-500 | |

| Stereo Zoom Microscope | Fisher Scientific | 03-000-014 | a magnifying glass is sufficient |

| Super Flangeless Ferrule w/SST Ring, Tefzel (ETFE), 1/4-28 Flat-Bottom, for 1/16” OD | IDEX Health & Sciene | P-259X | |

| Super Flangeless Nut PEEK 1/4-28 Flat-Bottom, for 1/16” & 1/32” OD | IDEX Health & Sciene | P-255X | |

| Super Tumble Stir Discs, 3.35 mm diameter, 0.61 mm thick | V&P Scientific, Inc. | VP 722F | |

| Tris Base | Fisher Scientific | BP152-500 | |

| Universal Base Plate, 2.5” × 2.5” × 3/8” | Thorlabs Inc. | UBP2 | |

| Urea | Fisher Scientific | U5378 | |

| VHP MicroTight Union for 360μm OD | IDEX Health & Sciene | UH-436 | 2 minimum |

| Water with 0.1% Formic Acid (v/v), LC/MS Grade | Fisher Scientific | LS118-500 | |

| Water, LC/MS Grade | Fisher Scientific | W6-4 |

6. High performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS)

Use the following LC mobile phases: water in 0.1 % FA (A) and ACN in 0.1 % FA (B).

Load 0.5 μg of peptides onto a trap column (180 μm × 20 mm) containing C18 (5 μm, 100 Å) and wash sample with 99% solvent A and 1% B for 15 min at 15 μL/min flow rate.

Separate peptides using an in-house packed column (0.075 mm i.d. × 20 mm) with C18 reverse phase material (5 μm, 125 Å).

Use the following analytical separation method: the gradient was pumped at 300 nL/min for 120 min: 0–1 min, 3% B; 2–90 min, 10–45% B; 100–105 min, 100% B; 106–120 min, 3% B.

-

Perform data acquisition of peptides in positive ion mode nano-electrospray ionization (nESI) using a high-resolution mass spectrometer.

NOTE: For this protocol, an ultra-performance LC (UPLC) instrument couple to a high-resolution mass spectrometer was utilized. Data dependent acquisition was utilized. The m/z scan range for MS1 was 3750–1500 at 60,000 resolution and 60 s dynamic exclusion. Ions with charge states of +1 and >6 were excluded. An automatic gain control (AGC) target of 5.5e5 was used with a maximum injection time of 50 ms and an intensity threshold of 5.5e4. Ions selected for MS2 were subjected to higher-energy collisional dissociation (HCD) fragmentation using 32% normalized collision energy. Fragment ions were detected in the spectrometer with 15,000 resolution and a 5.0e4 AGC target.

7. Data analysis

Search tandem MS files with a bottom-up proteomics analysis software against the C. elegans database.

Set the protein analysis search parameters as follow: one trypsin missed cleavage, 375–1500 m/z peptide mass range, fragment mass tolerance of 0.02, and precursor mass tolerance of 10 ppm. Carbamidomethylation is set as a static modification and all know hydroxyl radical side-chain modifications9,10 as dynamic. Peptide identification is established at 95% confidence (medium) and residue at 99% confidence (high). The false discovery rate (FDR) is set a 1%.

-

Export data to an electronic database and summarize the extent of oxidation per peptide or residue using the equation below11:

NOTE: Where EIC area modified is the extracted ion chromatographic area (EIC) of the peptide or residue with an oxidative modification, and EIC area is the total area of the same peptide or residue with and without the oxidative modification.

Representative Results

In the microfluidic flow system used for IV-FPOP, H2O2 and the worms are kept separated until just prior to laser irradiation. This separation eliminates breakdown of H2O2 by endogenous catalase and other cellular mechanisms12. The use of a 250 μm i.d. capillary shows a total sample recovery between 63–89% across two biological replicates, while the 150 μm i.d. capillary only shows 21–31% recovery (Figure 3A). The use of a larger i.d. capillary (250 μm) leads to better worm flow during IV-FPOP and single worm flow (Figure 3B) when compared to a smaller i.d. capillary (150 μm) (Figure 3C). The 150 μm i.d. capillary does not allow for single worm flow (Figure 3C) and multiple worms are seen flowing together at the laser irradiating window which decreases the amount of laser exposure per single worm.

Figure 3. Comparison of C. elegans flow and recovery using two i.d. capillaries.

(A) Percent recovery of worms after IV-FPOP for two biological replicates (BR) with 250 (gray) and 150 (black) μm i.d. capillaries. Error bars are calculated from the standard deviation across technical triplicates. C. elgans flowing through the laser irradiating window through a 250 μm (B) and 150 μm (C) i.d. capillaries. The worms are more tightly compacted in the smaller capillary. The 150 μm i.d. capillary shows clumping of worms. This figure has been modified from Espino et al.4.

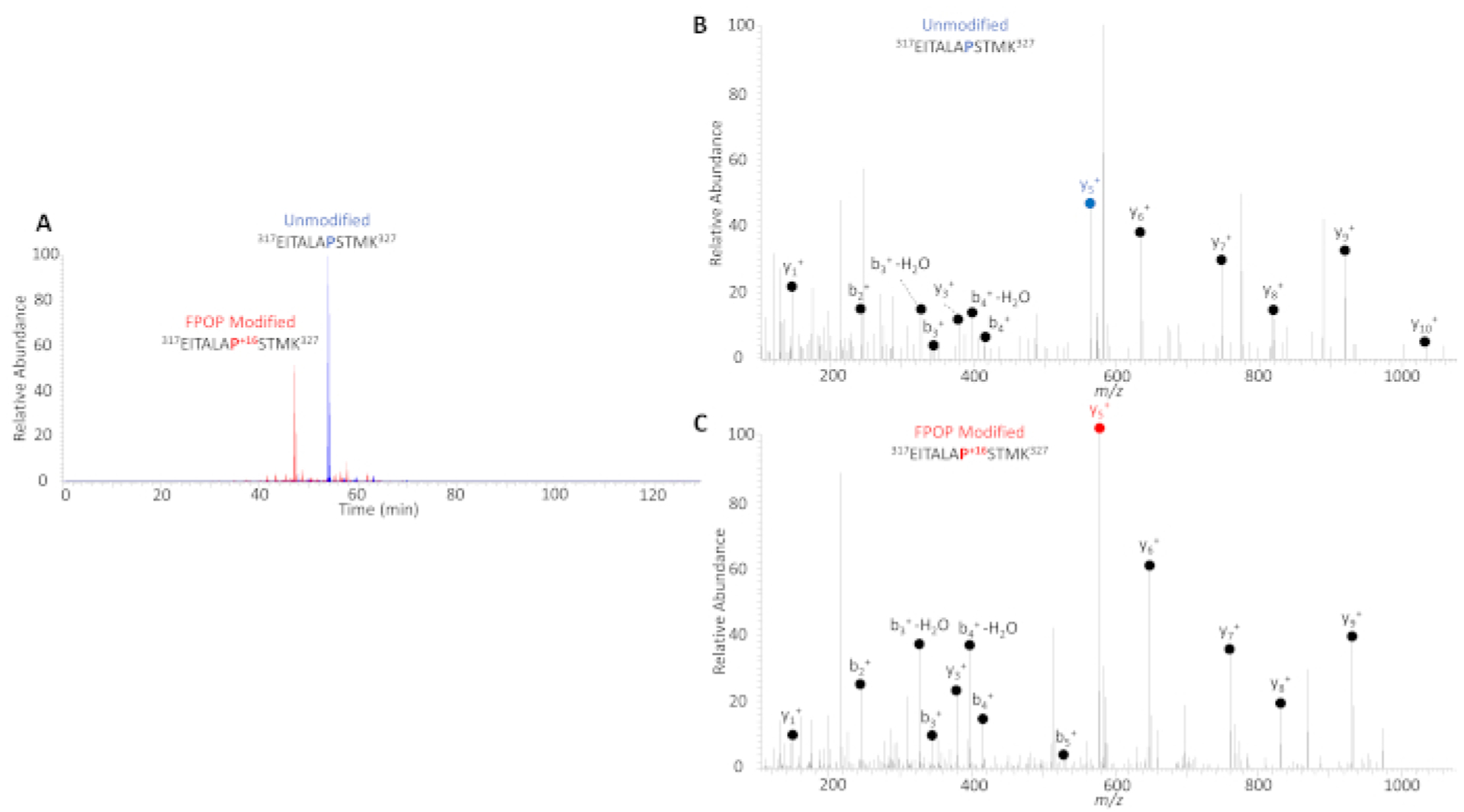

IV-FPOP is a covalent labeling technique that probes solvent accessibility in C. elegans. Figure 4A shows a representative extracted ion chromatograms (EIC) of a FPOP modified and unmodified peptide. The hydroxyl radical label changes the chemistry of oxidatively modified peptides, thus making FPOP modified peptides more polar. In reverse phase chromatography, IV-FPOP modified peptides have earlier retention times than unmodified peptides. MS/MS fragmentation of isolated peptides allows for the identification of oxidatively modified residues (Figure 4B).

Figure 4. Representative LC-MS/MS results following IV-FPOP.

(A) EIC of a FPOP modified peptide (red) and unmodified (blue). The selected peptide belongs to the actin-1 protein. (B) MS/MS spectrum of doubly charged unmodified actin-1 peptide 317–327. (C) MS/MS spectrum of doubly charged FPOP modified actin-1 peptide 317–327, in this example P323 was oxidatively modified (y5+ ion, red).

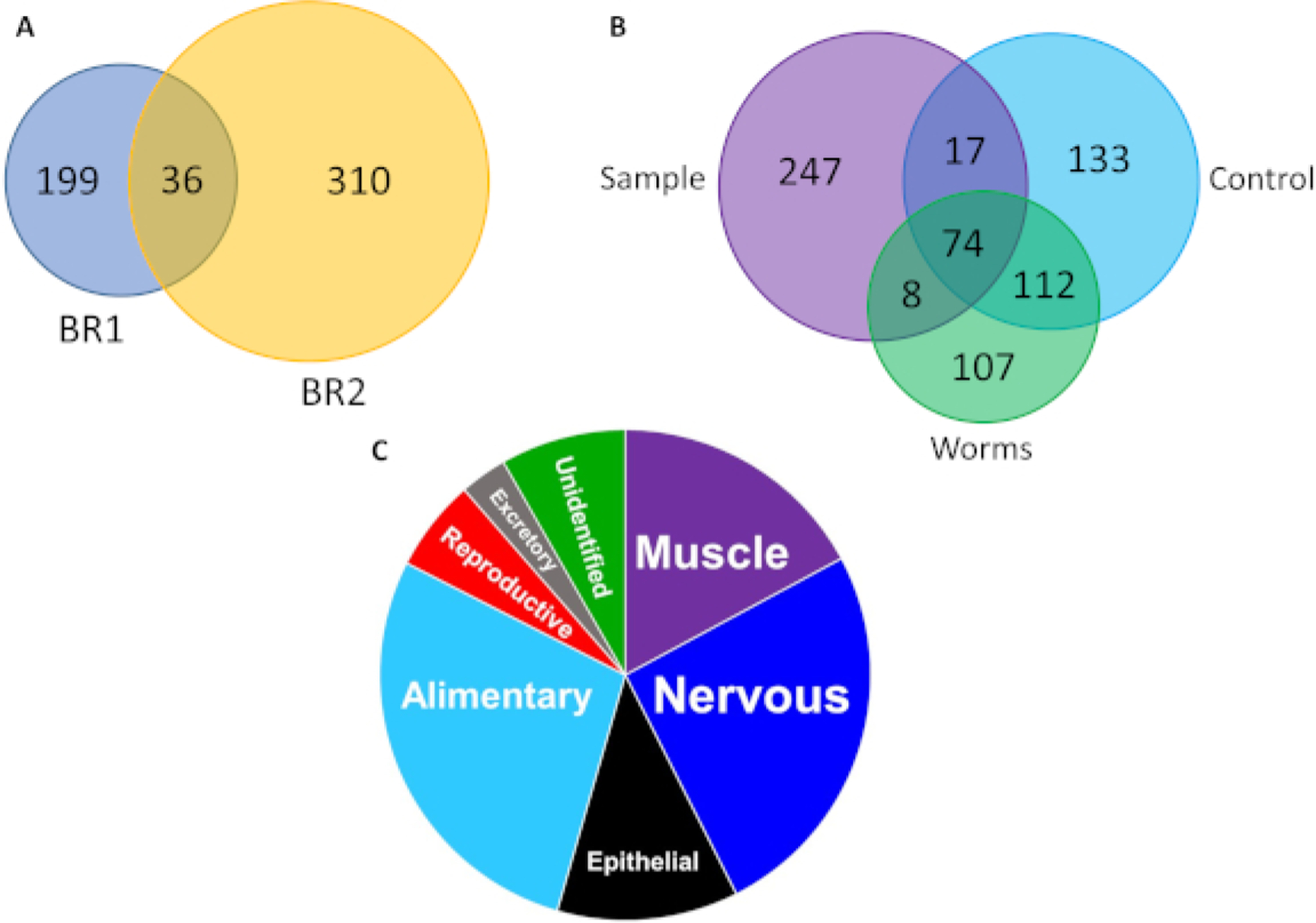

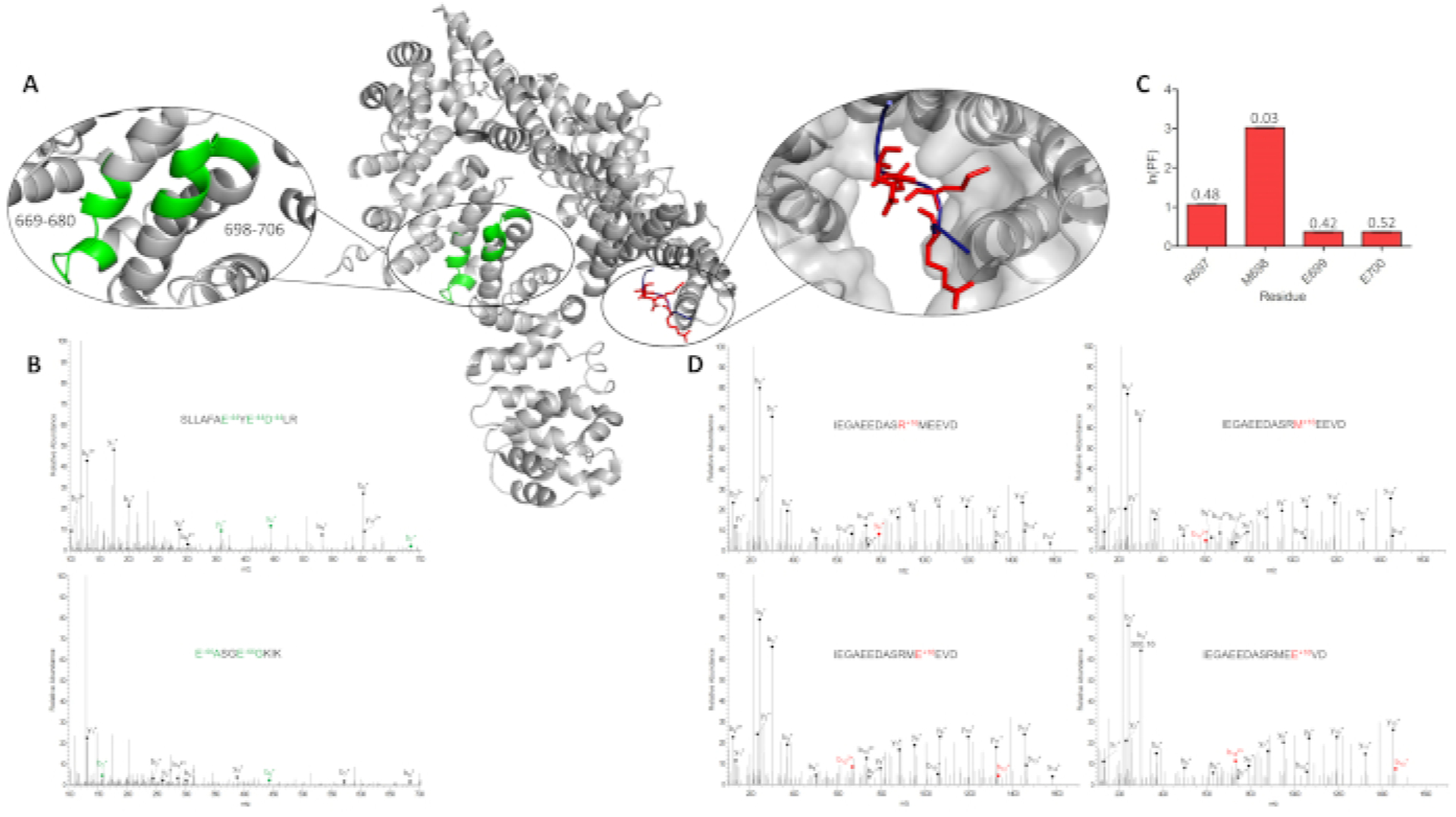

IV-FPOP has shown to oxidatively modified a total of 545 proteins across two biological replicates within C. elegans (Figure 5A,B). An advantage of IV-FPOP as a protein footprinting method relies on the technique’s ability to modify proteins in a variety of body systems within the worms (Figure 5C). This method would allow to probe protein structure and protein interactions regardless of body tissue or organ within the worm. Further, tandem MS analysis confirms IV-FPOP probes solvent accessibility in vivo. The oxidation pattern of the heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90) in complex with the myosin chaperon protein UNC-45 was analyzed (Figure 6). MS/MS analysis for Hsp90 shows four oxidatively modified residues (Figure 6C,D), the normalized extent of FPOP modification (ln(PF))5 indicates Hsp90’s residue M698 to be less solvent accessible than residues R697, E699, and E700 when bound to UNC-45 (Figure 6C). These differences in oxidation are validated by literature solvent accessible surface area (SASA) calculations (PDB 4I2Z13). Residue M698 has a SASA value of 0.03 which is consider to be a buried residue when compared to residues R697, E699, and E700 with higher SASA values (Figure 6C).14

Figure 5. IV-FPOP oxidatively modifies proteins within C. elegans.

(A) Venn diagram of oxidatively modified proteins in the presence of 200 mM hydrogen peroxide at 50 Hz across two biological replicates (BR), BR1 is in blue and BR2 is in yellow. (B) Venn diagram of oxidatively modified proteins identified in irradiated samples, hydrogen peroxide control, and worm-only control in BR2 across technical triplicates. (C) Pie chart of oxidatively modified proteins within different C. elegans body systems. This figure has been modified from Espino et al.4.

Figure 6. Correlating IV-FPOP modifications to solvent accessibility.

(A) Myosin chaperon protein UNC-45 (gray) (PDB ID 4I2Z13) highlighting two modified peptides identified by LC/MS/MS analysis, 669–680 and 698–706 (green, left inset). UNC-45 is bound to the Hsp90 peptide fragment (blue). Oxidatively modified residues within this fragment are shown in sticks (red), and UNC-45 is rendered as a surface (right inset). (B) Tandem MS spectra of UNC-45 peptide 669–680 (top) and 698–706 (bottom) showing b- and y-ions for the loss of CO2, an FPOP modification. (C) The calculated ln(PF) for the Hsp90 oxidatively modified residues, R697, M698, E699, and E700. Calculated SASA values for Hsp90 are denoted above each residue. (D) Tandem MS spectra for R697, M698, E699, and E700 showing a +16 FPOP modification. This figure has been modified from Espino et al.4.

Discussion

The current benchmark for the study of in vivo protein-protein interactions (PPI) is fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET). In its most simple form, this technique studies PPI by energy transfer between two molecules when they are in close proximity to one another15. Unlike MS techniques, FRET does not have the resolution to characterize conformational changes and interaction sites at the amino-acid level. MS based techniques have been increasingly utilized for the study of PPI16. IV-FPOP is a HRPF method that allows for the in vivo protein structural analysis in C. elegans. In order to successfully label C. elegans by IV-FPOP, it is important to properly assemble the microfluidic flow system to reduce sample loss. The 250 μm i.d. capillary has shown to maximize sample recovery when compared to smaller i.d. capillaries4. Larger i.d. capillaries have not been tested, however the microfluidic flow system is designed using a capillary with the same i.d. as a commercially available flow cytometry system for the sorting of C. elegans.11 The worm sample size is also important, a sample size of less than ~10,000 per sample prior to FPOP does not yield protein concentrations high enough for LC-MS/MS analysis. Higher samples sizes (>10,000 worms) can also be used by adjusting the initial starting volume (step 4.5).

Proper assembly of the microfluidic flow system is important. Leaks in the sample pathway result in an inconsistent flow of the worms or H2O2. The ferrules, sleeves, and 3–2 valves can be reused from multiple IV-FPOP experiments if properly cleaned after each experiment. However, we recommend to assemble a new microfluidic flow system for every biological replicate. If the microfluidics is properly assembled, the worms and H2O2 will mix at the mixing-T with minimal back pressure. As quality control (QC) of the microfluidic flow system, we recommend testing the mixing efficiency by using colored dyes. It is important to monitor the motion of the magnetic stirrers inside the worm syringe during IV-FPOP, improper sample mixing at the worm syringe or the mixing-T can result in back pressure causing leaks. In addition, poor mixing conditions lead to large sample losses, poor laser exposure of worms at the laser window, and clogging.

C. elegans maintenance is important in order to decrease background oxidation. We recommend growing the worms at low temperatures under low stress conditions as high temperatures can affect total background oxidation. A control sample set of worms only, no H2O2 and no laser irradiation, is recommended for all IV-FPOP experiments to account for background oxidation due to laboratory maintenance. One of the current limitations of this technique is total number of oxidatively modified peptides identified and the total number of residues oxidized per peptide in order to gain higher protein structural information. Although not recommended, an increase in oxidative modifications could be achieve by using higher concentrations of hydrogen peroxide. An increase in hydrogen peroxide could significantly alter important biological pathways as well as lead to oxidation-induced unfolding. If the hydrogen peroxide concentration for IV-FPOP is increased, it is recommended to test worm viability and background oxidation as concentrations higher than 200 mM have not been tested.

The LC-MS/MS protocol described can be optimized and modified to meet the MS QC of other laboratories. The use of 2D-chromatography techniques has been previously shown to increase the identification of oxidatively modified peptides and proteins18. Nonetheless, protein enrichment techniques that target a specific protein of interest are not recommend, including but not limited to antibody precipitation or pull-down assays. These techniques can bias towards one protein conformer if the epitope/binding site of the protein has been oxidatively modified by IV-FPOP. New developments in footprinting radical reagents, such as sulfate radical anion10 or trifluoromethylation19 could increase the versatility of IV-FPOP. Although the only labeling reagent tested in vivo thus far is hydrogen peroxide, other laser-activated radicals could be optimized. The use of other radicals should prove to be compatible with worm viability, cell permeable, and the 248 nm laser wavelength. Owing to the use of C. elegans as a model system for many human diseases, IV-FPOP has the potential to have a strong impact in studying the role of protein structure in disease pathogenesis.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by start-up funds from the University of Maryland, Baltimore and the NIH 1R01 GM 127595 awarded to LMJ. The authors thank Dr. Daniel Deredge for his help in editing the manuscript.

Footnotes

Video Link

The video component of this article can be found at https://www.jove.com/video/60910/

Disclosures

This publication was written in partial fulfillment of JAE Ph.D. thesis. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Hambly DM, Gross ML Laser flash photolysis of hydrogen peroxide to oxidize protein solvent-accessible residues on the microsecond timescale. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 16 (12), 2057–2063, (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones LM, B. Sperry J, A. Carroll J, Gross ML Fast Photochemical Oxidation of Proteins for Epitope Mapping. Analytical Chemistry. 83 (20), 7657–7661, (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Espino JA, Mali VS, Jones LM In Cell Footprinting Coupled with Mass Spectrometry for the Structural Analysis of Proteins in Live Cells. Analytical Chemistry. 87 (15), 7971–7978, (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Espino JA, Jones LM Illuminating Biological Interactions with in Vivo Protein Footprinting. Analytical Chemistry. 91 (10), 6577–6584, (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang W, Ravikumar KM, Chance MR, Yang S Quantitative mapping of protein structure by hydroxyl radical footprinting-mediated structural mass spectrometry: a protection factor analysis. Biophysical Journal. 108 (1), 107–115, (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keller CI, Calkins J, Hartman PS, Rupert CS UV photobiology of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans: action spectra, absence of photoreactivation and effects of caffeine. Photochemistry and Photobiology. 46 (4), 483–488, (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Konermann L, Collings BA, Douglas DJ Cytochrome c Folding Kinetics Studied by Time-Resolved Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry. Biochemistry. 36 (18), 5554–5559, (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brenner S The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 77 (1), 71–94, (1974). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu G, Chance MR Hydroxyl radical-mediated modification of proteins as probes for structural proteomics. Chemical Reviews. 107 (8), 3514–3543, (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gau BC, Chen H, Zhang Y, Gross ML Sulfate radical anion as a new reagent for fast photochemical oxidation of proteins. Analytical Chemistry. 82 (18), 7821–7827, (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rinas A, Espino JA, Jones LM An efficient quantitation strategy for hydroxyl radical-mediated protein footprinting using Proteome Discoverer. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry. 408 (11), 3021–3031, (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wagner BA, Witmer JR, van ‘t Erve TJ, Buettner GR An Assay for the Rate of Removal of Extracellular Hydrogen Peroxide by Cells. Redox Biology. 1 (1), 210–217, (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gazda L et al. The myosin chaperone UNC-45 is organized in tandem modules to support myofilament formation in C. elegans. Cell. 152 (1–2), 183–195, (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Willard L et al. VADAR: a web server for quantitative evaluation of protein structure quality. Nucleic Acids Research. 31 (13), 3316–3319, (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Broussard JA, Green KJ Research Techniques Made Simple: Methodology and Applications of Forster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) Microscopy. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 137 (11), e185–e191, (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaur U et al. Evolution of Structural Biology through the Lens of Mass Spectrometry. Analytical Chemistry. 91 (1), 142–155, (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pulak R in C. elegans: Methods and Applications (ed Strange Kevin) 275–286 Humana Press, (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rinas A, Jones L Fast Photochemical Oxidation of Proteins Coupled to Multidimensional Protein Identification Technology (MudPIT): Expanding Footprinting Strategies to Complex Systems. Journal of the American Society for Mass Spectrometry. 26 (4), 540–546, (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cheng M, Zhang B, Cui W, Gross ML Laser-Initiated Radical Trifluoromethylation of Peptides and Proteins: Application to Mass-Spectrometry-Based Protein Footprinting. Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 56 (45), 14007–14010, (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]