Abstract

Objective:

To determine the influence of high-risk HPV genotype on outcomes in HNSCC patients.

Materials and Methods:

This is a retrospective analysis of The Cancer Genome Atlas HNSCC cohort.

Results:

Using multivariate Cox regression analysis, we revealed that HPV33+ HNSCC patients have inferior overall survival compared to HPV16+ HNSCC patients independent of anatomical site (HR 3.59, 95% CI 1.58 to 8.12; p=0.002). A host anti-viral immune response, apolipoprotein B mRNA editing enzyme, and catalytic polypeptide-like mutational signature, was under represented and, aneuploidy and 3p loss were more frequent in in HPV33+ tumors. A deconvolution RNA-Seq algorithm to infer immune cell fractions revealed that CD8+ cytotoxic T-cell infiltration was reduced in HPV33+ compared to HPV16+ tumors (1.3% vs. 2.7%, p=0.007). TGFβ, a negative modulator of T-cell infiltration and function, showed expression and pathway enrichment in HPV33+ tumors.

Conclusions:

Our work reveals that HPV genotype, in particular HPV33, has a powerful impact on HNSCC patient survival. We argue that p16 immunohistochemistry as a surrogate biomarker for HPV+ status will lead to sub-optimal risk stratification and advocate HPV genotype testing as standard of care.

Introduction

Human papillomaviruses (HPVs) include more than 200 genotypes which, based on oncogenic potential, are divided into low-risk HPV (lrHPV) and high-risk HPV (hrHPV). lrHPVs are non-oncogenic but may promote benign hyper-proliferative diseases1,2. In contrast, hrHPVs are known to cause a cadre of solid malignancies including head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC)3–5. In the head and neck region, HPV+ malignancies predominantly arise in the oropharynx but may involve other anatomical sites. Several independent studies reported that among HPV+ oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas (OPSCCs), HPV16 accounts for ~80% of cases6–9. The distribution of HPV genotypes in HPV+, non-oropharynx HNSCC is similarly skewed toward HPV1610–12.

There is emerging literature that HPV genotypes may be associated with distinct outcomes in HPV+ HNSCC. Analysis of the HPV+ HNSCC subset from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) showed patients with hrHPV genotypes other than HPV16 (hrHPV-other) have inferior survival compared to HPV16+ HNSCC patients13. Two additional studies focused on OPSCC patients in the United States similarly reported survival benefit associated with HPV16+ over hrHPV-other6,8. These findings were replicated in a Norwegian OPSCC cohort9. In contrast, data published from a single institution in the United States showed no difference in overall survival (OS) between HPV16+ and hrHPV-other OPSCC7. Careful examination of these studies revealed variable distribution of hrHPV genotypes in the hrHPV-other group. HPV33 comprised more than 55% of hrHPV-other cases in three of the four publications reporting unfavorable clinical outcome for this group, suggesting that HPV33 may carry a distinctly poor prognosis.

Our analysis of the updated TCGA HNSCC dataset revealed that OS in HPV33+ HNSCC was inferior to HPV16+ HNSCC and this intriguing finding was independent of anatomical site. HPV33+ tumors were distinguished from HPV16+ tumors by higher aneuploidy and 3p loss events, and under-representation of the mutation signature of apolipoprotein B mRNA editing enzyme, catalytic polypeptide-like (APOBEC), a regulator of innate anti-viral immunity. CD8+ T-cell (CTL) fraction was lower in HPV33+ tumors and inversely correlated with transforming growth factor beta 1 (TGFB1). The distinct genomic and immune landscapes associated with these two HPV genotypes may contribute to their disparate clinical outcomes.

Materials and Methods

Study cohort.

Clinical data were downloaded from the Genomic Data Commons data portal from TCGA Research Network: http://cancergenome.nih.gov/. Overall and disease-specific survival information was obtained from the updated Pan-Cancer dataset14. Only HPV16+ or HPV33+ cases were included in the analysis; other HPV genotypes or cases with multiple HPV genotypes were excluded. HPV annotation was provided by the TCGA and based on analyses of whole genome and exome sequencing datasets. Five hundred and twenty-one cases, including 429 HPV-, 75 HPV16+, and 16 HPV33+, were analyzed. One HPV- patient did not have survival data and was not used in the survival analysis. The Kaplan-Meier survival curves were calculated using the R package survival15,16. Univariate analysis and multivariate Cox regression model were used to identify the risk associated with hrHPV genotypes and other clinical co-variates15. These clinical co-variates were obtained from published TCGA clinical data, with the exception of p53 states which were determined based on variant calling17.

COSMIC mutation signatures.

Whole exome sequencing data was available for 70 HPV16+ and 16 HPV33+ tumors. Mutational signatures of each patient sample were based on the TCGA exome sequencing data17 and identified with SignatureAnalyzer18. The identified mutational signatures were compared to the 30 COSMIC signatures and the closest match was selected by using a cosine correlation and average linkage18. One of the signatures did not match any of the COSMIC signatures and was described as CCN > CAN because of the prominence of this pattern. χ2 tests were used to calculate significance.

Aneuploidy.

The copy number of each gene was based on TCGA SNP 6.0 data processed with GISTIC2.019. Chromosomal, focal, and arm level SCNAs were based on the “SCNA level normalized by size” score as previously described20. A key difference is that we decided to increase the score for both amplifications and deletions rather than increasing for amplifications and decreasing it for deletions. Each cytogenetic band was assigned a score of 0, 1, or 2 based on the mode value of the genes in the band according to the following rules:

Where cx represents the mode log value for the cytogenetic band, t is equal to half the mean purity of the tumor samples21, and Cxi represents the score for the cytogenetic band x of patient i. For each patient, focal copy number score was calculated as the combined value of all the cytogenetic bands that were not involved in chromosomal or arm level copy number alterations. Arm level events were events where greater than 50% of the length of the chromosome arm shared the same log value. The entire arm was scored in the same way as a cytogenetic band from the focal copy number score. Each chromosome arm was considered independently; any arm that was part of a chromosome copy number alteration was counted only as part of the chromosome copy number score, and any part of the arm that was uninvolved in the arm level event was considered as a part of the focal copy number score. A copy number alteration was considered chromosomal if all of the cytogenetic bands for the chromosome shared exactly the same log change. The chromosomal copy number alteration score was the sum of the scores for all the chromosomal levels events, which were scored the same way as a cytogenetic band in the focal copy number score. Another measure of aneuploidy, aneuploidy score, was calculated based on data from Affymetrix SNP 6.0 arrays from TCGA data22. Scores were available for 75 HPV16+ and 16 HPV33+. A Shapiro-Wilk test showed that the SCNA and aneuploidy score dataset had a non-normal distribution; therefore, Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test was used to calculate significance. χ2 tests were used to assess the difference in 3p loss and p53 mutation status between HPV16+ and HPV33+ tumors.

RNA-Seq data and immune cell prediction.

Batch corrected RNA-Seq data was obtained from the supplemental materials of the Pan-Cancer dataset21. RNA-Seq data was available for 74 HPV16+ and 15 HPV33+ tumors. Log base two modified data was used to run Generally Applicable Gene-set Enrichment (GAGE) to identify differentially expressed pathways between HPV16+ and HPV33+ tumors23. Fractions of various cell types for each patient sample were identified using the R package EPIC24. Since the Shapiro-Wilk test showed non-normal distribution, significance was calculated using a Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test. A χ2 test was used to assess the difference in CTL, TGFB1, and INFG between HPV16+ and HPV33+ tumors. CTL fraction was compared to other variables using Spearman correlation. A multivariate Cox regression model was used to identify the risk associated with each immune component and was adjusted for hrHPV genotype15. Expression of co-inhibitory receptors was normalized to CTL fraction with the outliers removed (CTL fraction < 0.00125) and the expression of co-inhibitory ligands was normalized to tumor purity quantitated by ABSOLUTE. Expression heat maps were spliced based on HPV status with unsupervised clustering.

Results

Inferior survival in HPV33+ HNSCC.

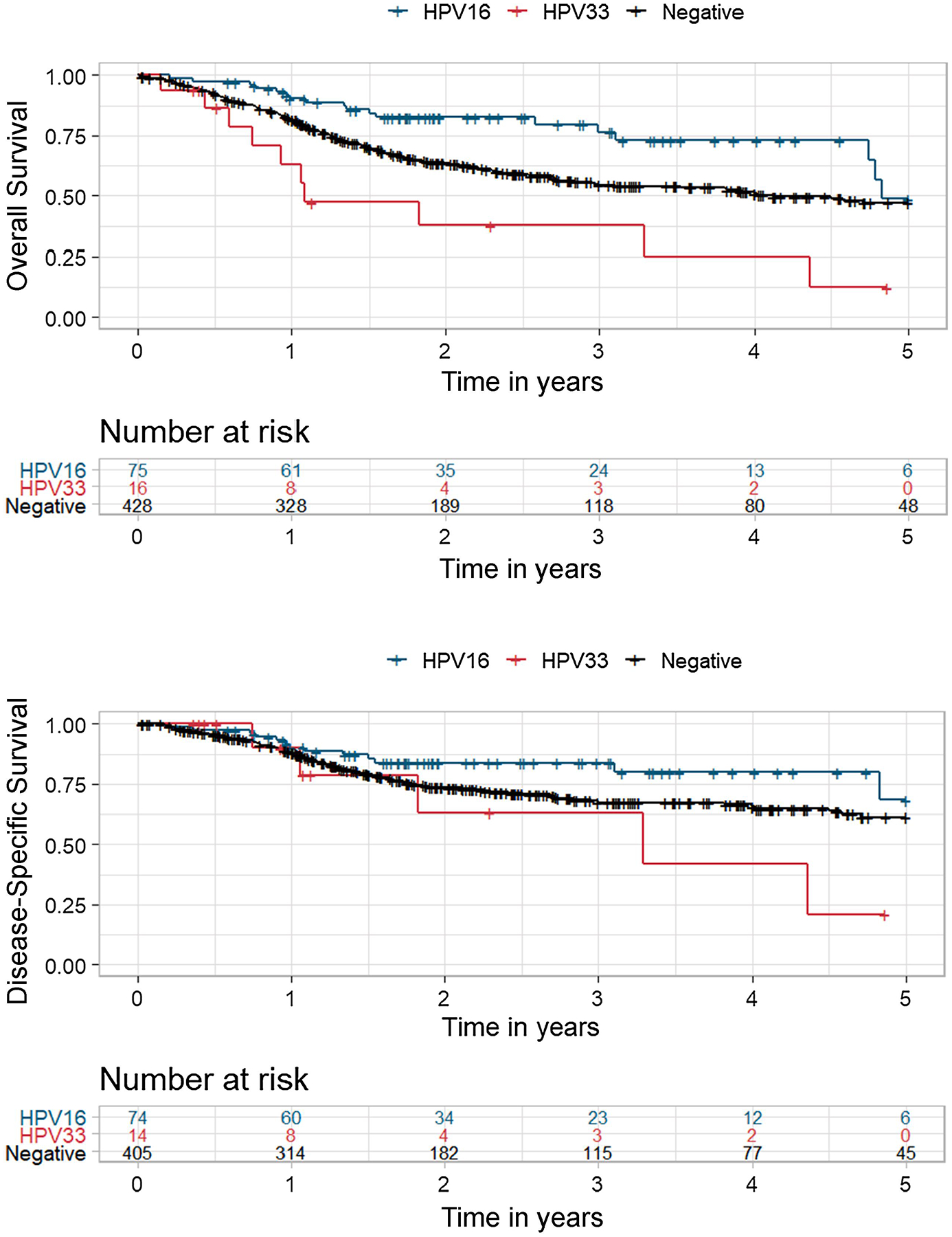

The updated TCGA HNSCC dataset contains 429 HPV-, 75 HPV16+, 16 HPV33+, 3 HPV18+, 3 HPV35+, 1 HPV56+, and 1 HPV16+/HPV33+. We focused our investigation on HPV16+ and HPV33+ patients based on our hypothesis that HPV33+ may confer an exceptionally poor prognosis. Distribution of clinical co-variates was similar between HPV16+ and HPV33+ patients with the exception of anatomical subsite (OPSCC vs. non-OPSCC); HPV33+ patients tend to present with non-oropharynx tumors (p=0.043; Supplemental Table 1). As shown in Figure 1, HPV33+ patients had inferior OS (p<0.001) and disease-specific survival (DSS) (p=0.041) compared to HPV16+. Multivariate Cox regression analysis, adjusted for clinical and lifestyle co-variates, showed that the risk of death was 3.59 (95% CI 1.58 to 8.12; p=0.002) times higher in HPV33+ patients than in HPV16+ patients (Table 1). Age, gender, nodal status, smoking status, and p53 state were significant co-variates but had less impact on OS than HPV33+ status. Anatomical subsite (non-OPSCC vs. OPSCC) was included in this regression model and was not found to be a significant co-variate (HR 1.03, p=0.91). For DSS, after adjusting for co-variates in a Cox regression analysis, HPV33+ status had the greatest impact on disease recurrence (HR 2.73, 95% CI 0.95 to 7.81; p=0.061); however, this association trended but did not reach statistical significance (Table 2).

Figure 1. Association of HPV16+ and HPV33+ with overall survival in the TCGA HNSCC cohort.

A, Kaplan-Meier analysis of overall survival stratified by HPV status and genotype. HPV33+ vs. HPV16+, log-rank p<0.001; HPV33+ vs. HPV-, log-rank p=0.009. B, Kaplan-Meir analysis of disease specific survival stratified by HPV status and genotype. HPV33+ vs. HPV16+, log-rank p=0.043; HPV33+ vs. HPV-, log-rank p=0.19.

Table 1:

Univariate and multivariate analyses for overall survival.

| Overall Survival | Univariate | Multivariate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Co-variates | HR (95% CI) | p-value | HR (95% CI) | p-value |

| HPV Genotype (HPV33 vs HPV16) | 4.26 (1.98–9.17) | <0.001 | 3.59 (1.58–8.12) | 0.002 |

| HPV Status (HPV33 vs HPV-) | 2.28 (1.20–4.31) | 0.012 | 2.95 (1.43–6.05) | 0.003 |

| HPV Status (HPV16 vs HPV-) | 1.87 (1.17–3.00) | 0.009 | 1.22 (0.67–2.20) | 0.52 |

| Age | 1.02 (1.01–1.03) | <0.001 | 1.02 (1.01–1.04) | 0.005 |

| Gender (female vs male) | 1.37 (1.04–1.82) | 0.028 | 1.42 (1.04–1.95) | 0.030 |

| T stage (III/IV vs I/II) | 1.32 (0.99–1.76) | 0.056 | 1.19 (0.86–1.63) | 0.29 |

| N Status (N2/N3 vs N0/N1) | 1.35 (1.02–1.78) | 0.038 | 1.58 (1.16–2.15) | 0.004 |

| Smoking Status (smoker vs non-smoker) | 1.33 (1.00–1.76) | 0.051 | 1.39 (1.02–1.90) | 0.034 |

| p53 State (mutant vs wild-type) | 1.54 (1.12–2.12) | 0.007 | 1.64 (1.11–2.42) | 0.013 |

| Anatomical Site (non-OPSCC vs OPSCC) | 1.60 (1.02–2.51) | 0.041 | 1.03 (0.59–1.80) | 0.91 |

Table 2:

Univariate and multivariate analyses for disease-specific survival.

| Disease-Specific Survival | Univariate | Multivariate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Co-variates | HR (95% CI) | p-value | HR (95% CI) | p-value |

| HPV Genotype (HPV33 vs HPV16) | 2.87 (1.03–7.98) | 0.043 | 2.73 (0.95–7.81) | 0.061 |

| HPV Status (HPV33 vs HPV-) | 1.83 (0.75–4.50) | 0.19 | 2.11 (0.81–5.51) | 0.13 |

| HPV Status (HPV16 vs HPV-) | 1.57 (0.90–2.73) | 0.11 | 1.29 (0.63–2.64) | 0.48 |

| Age | 1.01 (0.99–1.03) | 0.28 | 1.01 (0.99–1.03) | 0.25 |

| Gender (female vs male) | 1.04 (0.70–1.54) | 0.86 | 1.17 (0.76–1.79) | 0.48 |

| T stage (III/IV vs I/II) | 1.53 (1.03–2.25) | 0.033 | 1.32 (0.87–2.02) | 0.19 |

| N Status (N2/N3 vs N0/N1) | 1.56 (1.10–2.23) | 0.014 | 1.85 (1.26–2.72) | 0.002 |

| Smoking Status (smoker vs non-smoker) | 1.29 (0.89–1.86) | 0.18 | 1.27 (1.02–1.90) | 0.23 |

| p53 State (mutant vs wild-type) | 1.40 (0.93–2.10) | 0.10 | 1.33 (0.85–2.17) | 0.26 |

| Anatomical Site (non-OPSCC vs OPSCC) | 1.49 (0.85–2.59) | 0.16 | 1.09 (0.55–2.17) | 0.80 |

Distinct genomic landscape in HPV33+ HNSCC.

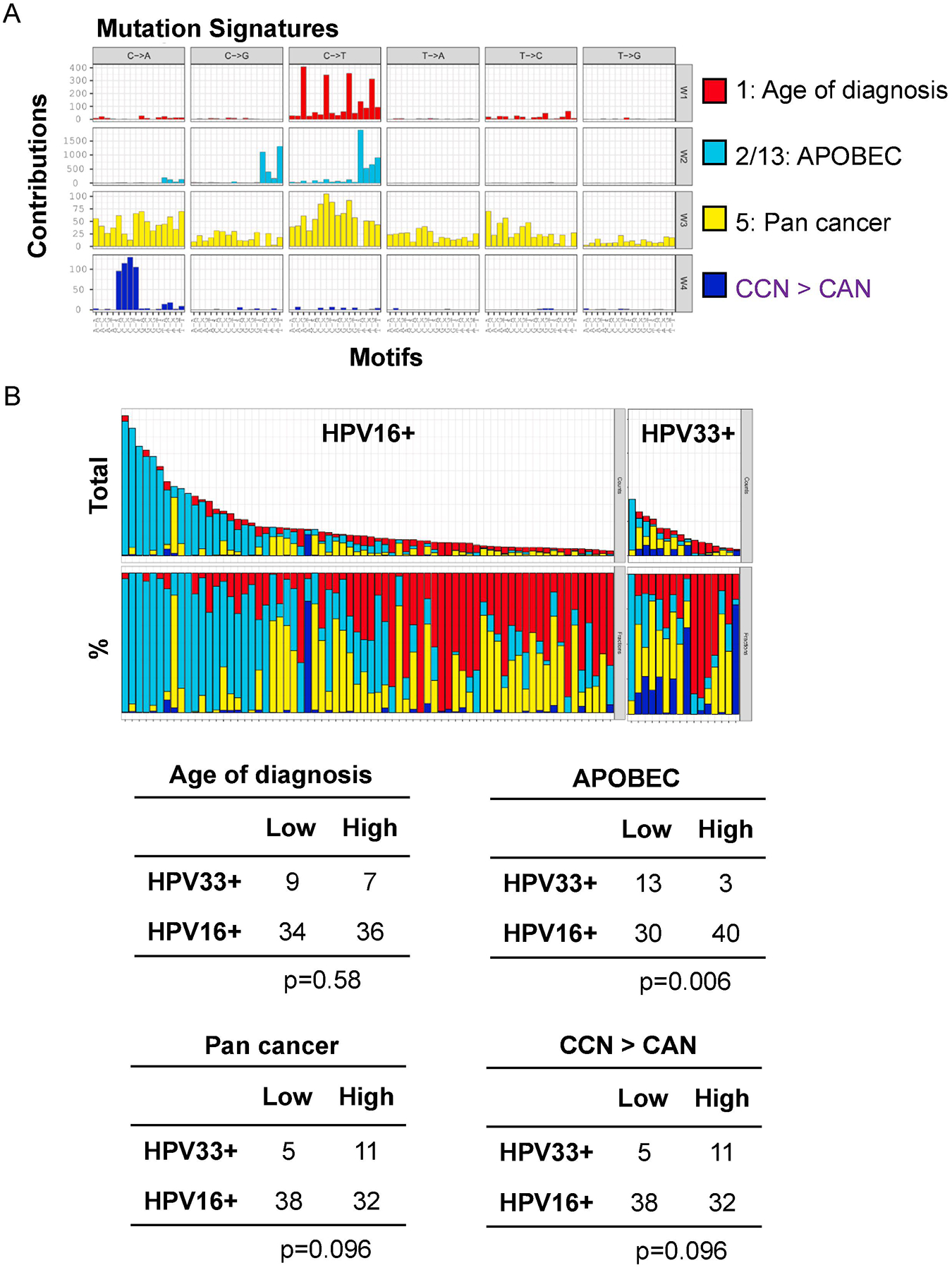

Total exome mutational burden and global methylation profile were similar between HPV16+ and HPV33+ tumors (Supplemental Figures 1 and 2). Four mutational signatures were enriched in HPV16+ and HPV33+ tumors (Figure 2). Three signatures closely matched COSMIC signatures: signature 1 (related to age of diagnosis), signature 2/13 (APOBEC), and signature 5 (pan-cancer). The APOBEC signature reflects DNA damage from APOBEC3A/B activity in response to viral infection25. Moreover, APOBEC-directed mutational events and signatures are more frequent in HPV+ compared to HPV- HNSCC26. In our analysis, HPV16+ tumors had a higher proportion of APOBEC-mediated mutations than HPV33+ tumors; 57% APOBEC high in HPV16+ vs. 23% APOBEC high in HPV33+ (χ2, p=0.006).

Figure 2. Mutational signatures in HPV16+ and HPV33+ HNSCC.

A, SignatureAnalyzer analysis of HPV16+ and HPV33+ tumors identified four mutational signatures: COSMIC signature 1 (related to age of diagnosis), COSMIC signature 2/3 (APOBEC), COSMIC signature 5 (pan cancer), and CCN > CAN. B, Four mutational signatures for each patient are represented as total number of mutations (top) and percentage of mutations (bottom).

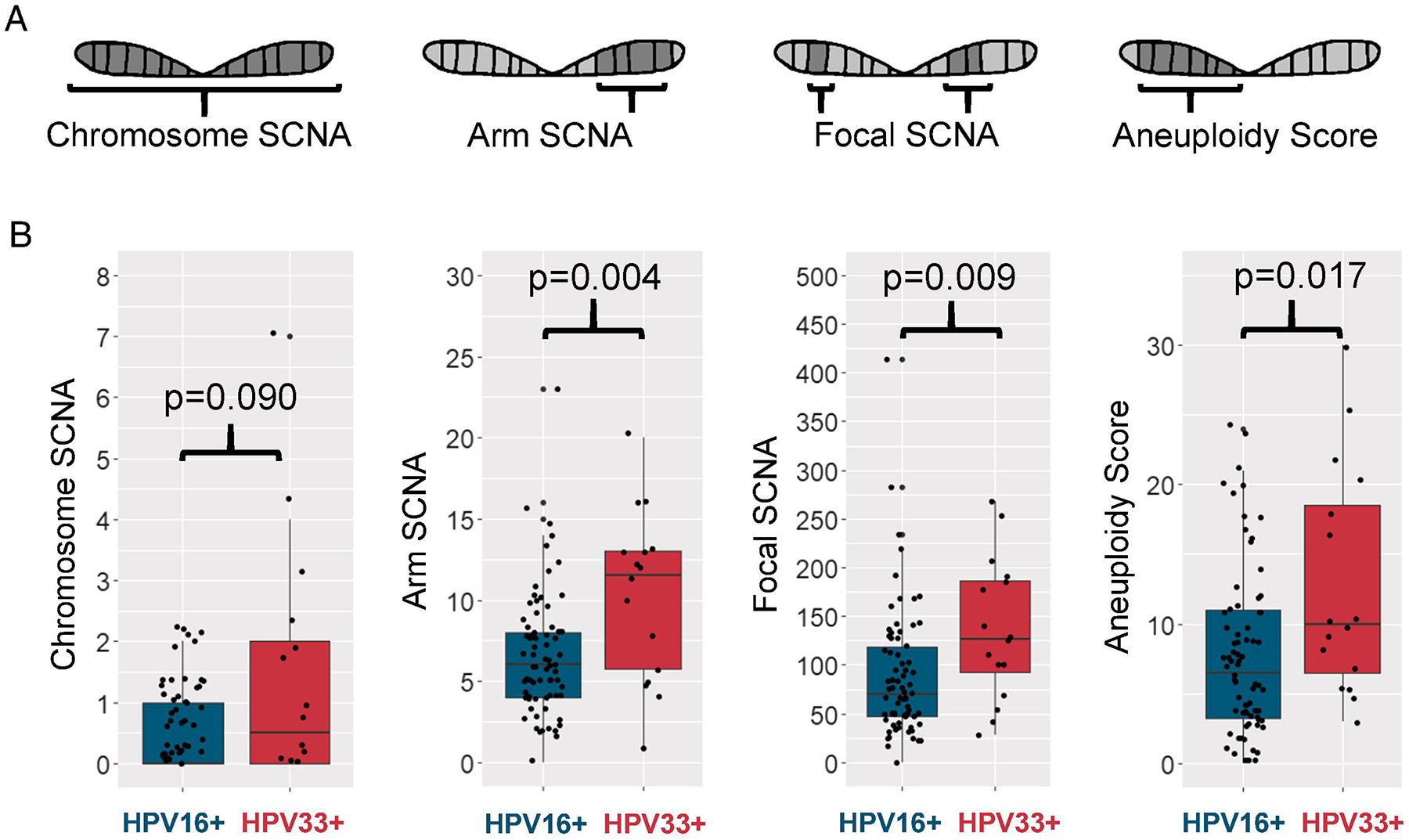

Another measure of genomic landscape is somatic copy number alterations (SCNAs). We assessed SCNAs at three levels: whole chromosome, arm, and focal events. HPV33+ tumors did not differ from HPV16+ tumors in chromosome level alterations but had higher arm level (median score 11.5 vs. 6, p=0.004) and focal level (median score 127 vs. 69.5, p=0.009) SCNAs (Figure 3A). An additional measure of SCNA, aneuploidy score, was higher in HPV33+ than HPV16+ tumors (median score 10 vs. 6.5, p=0.017).

Figure 3. Somatic copy number alterations in HPV16+ and HPV33+ HNSCC.

A, Schematic of the four levels of somatic copy number alterations (SCNAs): whole chromosome SCNA, arm level SCNA that cover at least 50% of an arm, focal level SCNA that covers less than 50% of an arm, and aneuploidy score which looks at arm level events that cover at least 80% of the arm. B, Somatic copy number alterations at different levels in HPV16+ and HPV33+ tumors.

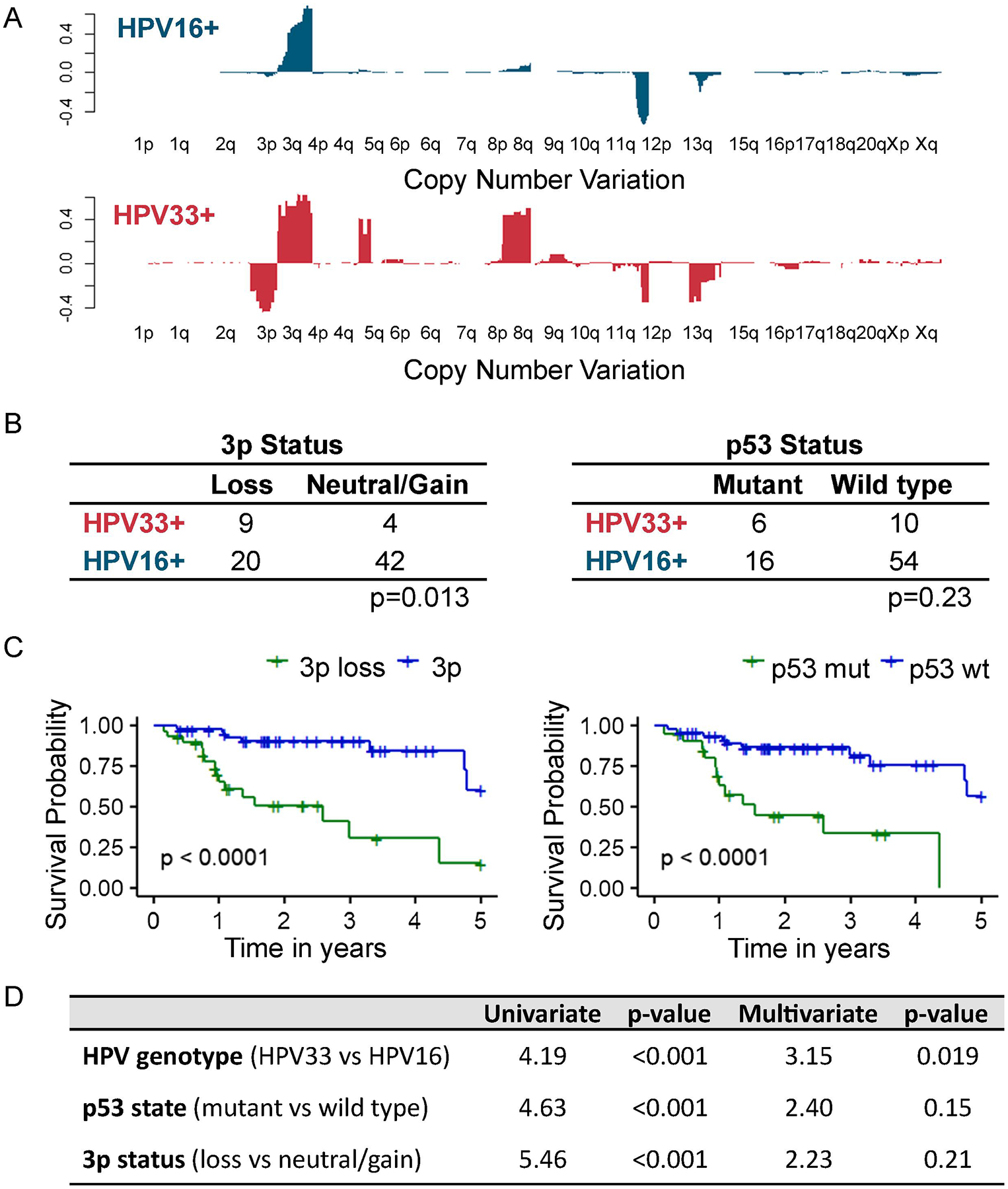

At the level of individual cytobands, HPV33+ tumors showed a greater tendency for 3p loss and 8q gain compared to HPV16+ tumors (Figure 4A). Chromosomal 3p loss and p53 mutation are concurrent genomic events in HPV- HNSCC and associated with inferior OS compared to p53 mutation alone27. The clinical impact of 3p loss is not restricted to HPV- HNSCC but extends to HPV+ HNSCC to drive an aggressive tumor phenotype27. In HPV33+ tumors, loss of 3p, using aneuploidy score, occurred at a higher frequency than in HPV16+ tumors (χ2, p=0.013). p53 mutational rate was similar between HPV33+ and HPV16+ tumors (χ2, p=0.23). In this HPV+ cohort, 3p loss (long-rank, p<0.0001) and p53 mutation (log-rank, p<0.0001) were negative prognostic biomarkers for OS (Figure 4C). Multivariate Cox regression model with three co-variates, 3p status, HPV genotype, and p53 state, showed that HPV33+ status had the greatest impact on OS (HR 3.15, 95% CI 1.21 to 8.25; p=0.022) and this association was independent of 3p status and p53 state.

Figure 4. Chromosomal 3p loss in HPV16+ and HPV33+ tumors.

A, Cytoband alterations at individual chromosome levels. B, 3p loss and p53 mutation. C, Kaplan-Meier analyses of overall survival stratified based on 3p status or p53 state. 3p loss vs. 3p neutral/gain, log-rank p<0.0001; p53 wildtype vs. p53 mutation, log-rank p<0.0001. D, Multivariate Cox regression model using 3p status, HPV genotype, and p53 state.

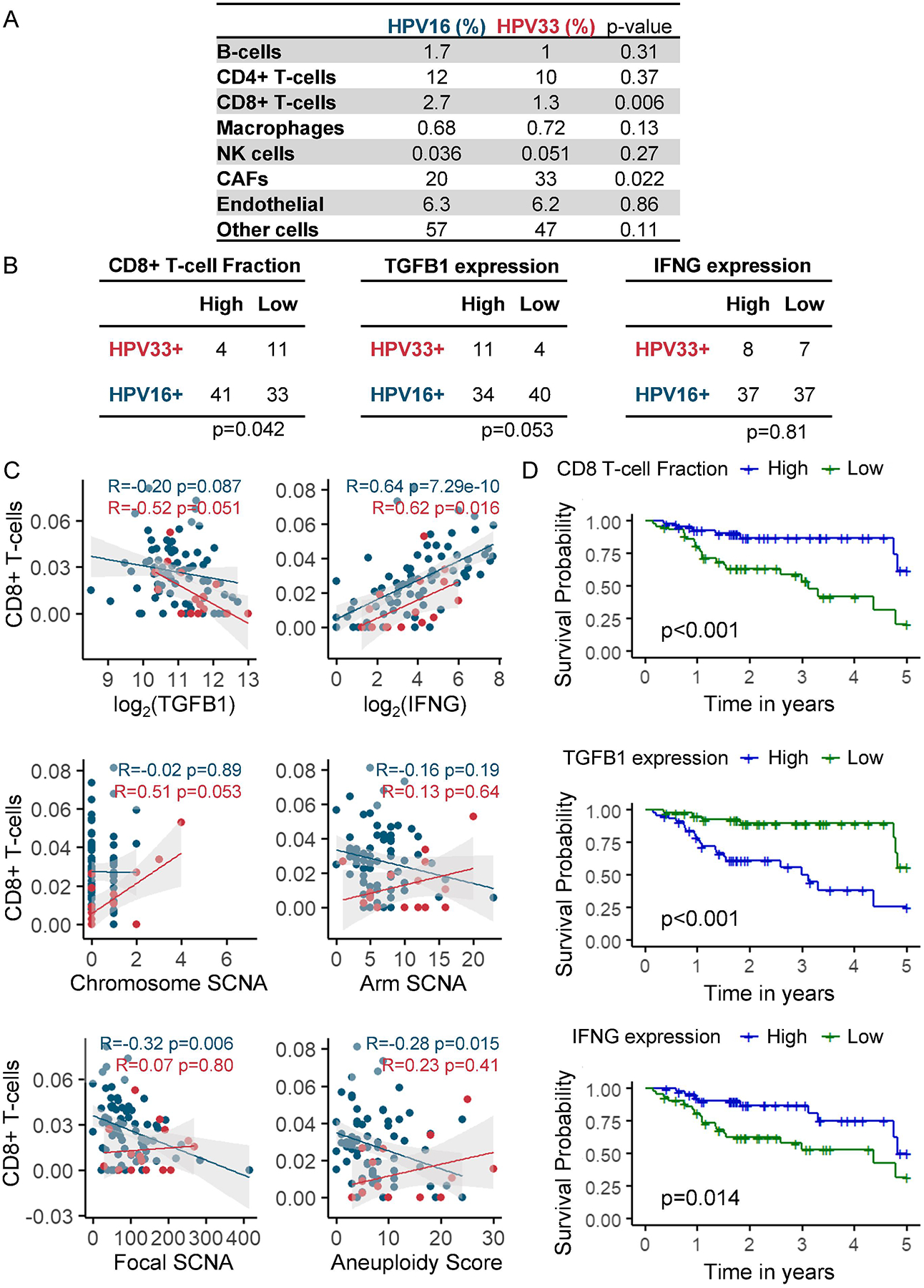

Distinct immune landscape in HPV33+ HNSCC.

A deconvolution algorithm, EPIC24, inferred a lower CTL fraction in HPV33+ than in HPV16+ tumors (1.3% vs. 2.7%, p=0.006) (Figure 4A). Correlation between CTL infiltration and two well-recognized mediators of CTLs, TGFB1 and interferon-γ (INFG) was investigated. Pathway analysis demonstrated TGFβ signal enrichment in the HPV33+ tumors relative to the HPV16+ tumors (p=0.049). Consistent with this finding, high TGFB1 expression was more frequent in HPV33+ tumors (73.3% vs. 45.9%; p=0.053) (Figure 4B). An inverse correlation was observed between TGFB1 and CTL fraction in HPV33+ tumors (R=−0.52, p=0.051) but not in HPV16+ tumors (R=−0.20, p=0.087) (Figure 4C). IFNG, an immunoregulatory cytokine that is secreted by a spectrum of immune cells including CTLs, was correlated with CTL fraction in both HPV16+ (R=0.64, p=7.29×10−10) and HPV33+ (R=0.62, p=0.016) tumors.

Aneuploidy has been shown to negatively correlate with cytotoxic immune infiltration in numerous solid malignancies20. In line with published literature, an inverse correlation between CTL fraction and aneuploidy was shown for HPV16+ tumors for focal SCNA (R=−0.32, p=0.006) and aneuploidy index (R=−0.28, p=0.015). In contrast, there was no correlation between CTL fraction and aneuploidy in HPV33+ tumors. CTL fraction was prognostic for superior OS (HR 0.60, 95% CI 0.44 to 0.80; p<0.001) independent of HPV genotype, underscoring the importance of tumor immunogenicity in patient outcome (Figure 4D). Also, high TGFB1 (HR 2.37, 95% CI 1.39 to 4.03; p=0.002) and low IFGN (HR 0.67, 95% CI 0.54 to 0.83; p=0.001) were associated with poor prognosis independent of HPV genotype.

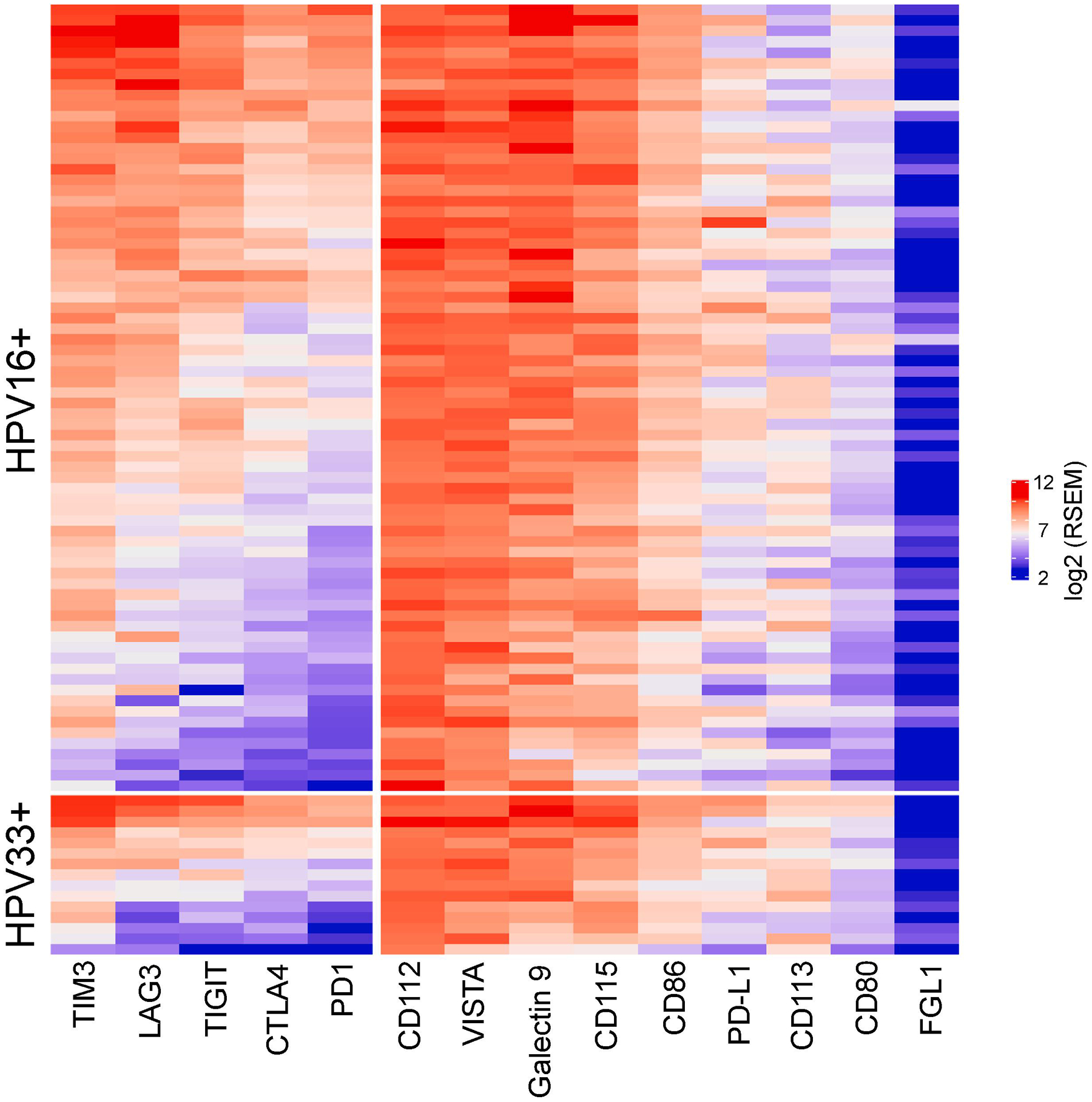

Expression of immune checkpoint pathways in HPV33+ HNSCC.

Immunotherapy targeting the immune checkpoint receptor programmed cell death protein-1 (PD-1) have resulted in dramatic responses in a subset of HPV+ HNSCC patients in the metastatic/recurrent setting, however, most of these patients did not respond to this treatment paradigm. In addition to PD-1 and its cognate ligand, PD-L1, there are other co-inhibitory pathways that may be co-opted by tumor cells to impair T-cell function in the tumor microenvironment. As shown in Figure 5, the expression profile of key co-inhibitory receptors and ligands was similar, with co-expression of several immune checkpoint pathway genes, between HPV16+ and HPV33+ tumors. T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin-domain containing 3 (TIM3) and galectin 9 was the predominant receptor-ligand pair that was over-represented in these HPV+ tumors. Moreover, V-domain Ig suppressor of T cell activation (VISTA), which can function as a co-inhibitory receptor and ligand, is universally over-expressed.

Figure 5. Immune landscape in HPV16+ and HPV33+ HNSCC.

A, Mean percentage of various cell types inferred by EPIC. B, CD8+ T-cell fraction, TGFB1, and IFNG. Median was used to divide the cohort into two groups: high (>median) and low (<median). C, Correlation between CD8+ T-cell fraction and TGFB1, IFNG, or SCNAs. D, Kaplan-Meier analyses of overall survival stratified by CD8+ T-cell fraction, TGFB1 expression, or IFNG expression. Median was used to divide the cohort into two groups: high (>=median) and low (<median). CD8+ T-cell high vs. CD8+ T-cell low, log-rank p<0.001; TGFB1 high vs. TGFB1 low, log-rank p<0.001; INFG high vs. IFNG low, log-rank p=0.014.

Discussion

Patients with p16+ OPSCC consistently demonstrate better treatment responses than those with p16- OPSCC5,28–31. Consequently, treatment de-escalation strategies for the p16+ OPSCC population are actively being investigated. However, despite their better prognosis, a subset of p16+ OPSCC patients experience early treatment failure. Established biomarkers to distinguish this subgroup are needed and would substantially improve risk stratification for OPSCC patients.

In OPSCC, p16 IHC is widely used as a surrogate marker for hrHPV infection. While useful and cost effective in this application, its inability to distinguish individual HPV genotypes is a limitation. As we have shown, HPV genotype matters to patient survival. Our analysis reveals dramatically inferior outcomes for HPV33+ HNSCC compared to HPV16+ HNSCC, even after adjusting for co-variates including anatomical site (OPSCC vs. non-OPSCC), smoking status, and p53 states. Strikingly, OS among HPV33+ patients was even poorer than for HPV- HNSCC patients (HR 2.95, 95% CI 1.43 to 6.05; p=0.003). Our results argue that p16 IHC may be sub-optimal for HPV+ OPSCC risk stratification and further investigation of the prognostic utility of non-HPV16 genotypes in an independent OPSCC cohort is warranted.

Concerns have been raised that population-level HPV vaccination may shift the distribution of hrHPV genotypes toward non-vaccine hrHPV genotypes. This phenomenon, known as genotype replacement, has been observed following implementation of the heptavalent pneumococcal vaccine32. Genotype replacement presumes a fitness competition exists for hrHPV genotypes to colonize distinct niches in the head and neck region; however, this remains an open question. The distribution of hrHPV genotypes in the post-HPV vaccination world is difficult to predict but, a sobering possibility that has not been put forth is the replacement of HPV16 by hrHPV genotypes with poorer prognoses, such as HPV33. It is likely that the evolving landscape of HPV genotypes carries a potential for significant prognostic impact in HNSCC and other HPV-driven malignancies.

It is becoming clear that current knowledge based on HPV16+ OPSCC does not generalize to other hrHPV genotypes and head and neck sub-sites. Much remains to be elucidated about the clinical behavior and pathogenesis of hrHPV-other HNSCC. To understand the poor clinical outcomes observed for HPV33+ HNSCC, we first looked for global genomic and transcriptomic differences in HPV16+ and HPV33+ tumors. Total mutational burden and, methylation and gene expression profiles showed a high degree of overlap (Supplemental Figures 1, 2, and 3). Analysis of mutational signatures did reveal a difference in COSMIC signature 2/13, which was enriched in HPV16+ compared to HPV33+ tumors. This mutational signature reflects the activity of APOBEC, which is a family of cytidine deaminases that promote the conversion of deoxycytidine to deoxythymidine. APOBEC enzymes play an intimate role in innate immunity and are activated in response to viral infections, including HPV33. Interestingly, while the APOBEC signature showed enrichment in HPV16+ tumors, expression of APOBEC3 enzymes was similar for tumors of both HPV genotypes (Supplemental Figure 4). Enrichment of this signature in HPV16+ tumors could reflect past differences in APOBEC activity, perhaps at the stage of initial infection, and/or differences in post-transcriptional regulation.

Since APOBEC plays a central role in viral immune response, we looked for differences in various immune cells and immunomodulatory cytokines between HPV16+ and HPV33+ tumors. CTLs were the only immune cell type examined that was differentially represented between HPV16+ and HPV33+ tumors. Analysis of the TCGA datasets from 12 disease sites showed an inverse correlation between cytotoxic immune cell expression signature, in particular CTLs, and aneuploidy20. Our work corroborates this finding, revealing a negative correlation between CTLs and aneuploidy in HPV16+ tumors. High levels of CTLs may reflect better immune surveillance and immune editing, with more efficient elimination of cancer cells with chromosomal derangements resulting in a low aneuploidy tumor state34. This possibility assumes a critical threshold of active CTLs in the tumor microenvironment and appears to occur in HPV16+ tumors. In contrast to HPV16+ tumors, no correlation between CTLs and aneuploidy was shown in HPV33+ tumors. We speculate that in high aneuploidy HPV33+ tumors, a subset of cancer cells autonomously or in concert with stromal cells have intrinsic capacity or dynamically evolved to secrete immunosuppressive factors, such as TGFB1, to thwart CTL infiltration and evade immunoediting.

In our analysis, HPV16+ and HPV33+ tumors showed unique distributions among head and neck subsites. Consistent with published literature, HPV16+ SCC exhibited a marked predilection for the oropharynx. The reasons for this site preference are not completely clear; however, it has been proposed that the tonsillar crypts provide an “immune-protected” environment that shields HPV16+ cells from immune surveillance and elimination35. Elevated expression of the immune checkpoint ligand PD-L1 has been demonstrated in the reticular epithelium of these crypts and could dampen the CTL response to viral antigens, allowing proliferation of a tumor that would otherwise elicit a strong immune response35. Compared to HPV16+ tumors, HPV33+ tumors showed reduced CTL and appeared to lack a preference for an immune-protected environment, which may suggest lower intrinsic immunogenicity of these tumors.

Checkpoint blockade with anti-PD-1 antibodies, pembrolizumab and nivolumab, is approved for metastatic/recurrent HNSCC and under investigation for other indications. Treatment with these PD-1 inhibitors in some of the metastatic/recurrent HNSCC patients resulted in dramatic responses but for the majority, oncologic control has been limited36,37. Improved understanding of the tumor immune landscape may provide insights into resistance mechanisms to PD-1 blockade. TCGA HNSCC patients were surgically managed with a subset receiving adjuvant radiation or chemoradiation and failures in this treatment population are likely candidates for checkpoint blockade. Our analyses showed co-expression of several co-inhibitory receptors to varying degrees; although, in the panel of co-inhibitory receptors we analyzed, TIM3 and VISTA had the highest expression. PD-1 was not exclusively nor dominantly expressed in most of the HPV33+ and HPV16+ tumors; this finding may offer an explanation for the sub-optimal response rates to PD-1 inhibition in HPV+ HNSCC patients. As inhibitors against other immune checkpoint pathways are developed and moved to the clinic, careful consideration of the tumor immune landscape on an individual patient level is needed in order to recommend a precision immunotherapeutic strategy for optimal clinical management.

A limitation of our analysis, as with most studies examining hrHPV-other HNSCC, is the relatively small number of hrHPV-other cases, which limits statistical power. Additionally, the representation of each genotype within a study cohort can vary widely, both regionally and temporally. While in our study, HPV33 accounted for more than half of the non-HPV16+ cases, HPV18 was the predominant hrHPV-other genotype in several Korean cohorts and was associated with poorer prognosis than HPV1638,39. A 2016 study looking at cervical HPV infections in women living in San Luis Potosi, Mexico, found HPV33 infections to be twice as common as HPV16 infections40. In contrast, the group’s earlier 2008 study conducted in the same city showed infections with HPV16 to be 59 times as frequent than with HPV3341. The authors suggest that their later findings are consistent with an outbreak of HPV33; however, the reasons for such an outbreak are unclear. Given the variable frequency of individualgenotypes, however, caution should be exercised in generalizing findings from a single study to broader settings.

We showed that HPV genotype, in particular HPV33, has a powerful impact on HNSCC patient survival. Well-designed prospective studies are needed to monitor the evolving landscape of HPV genotypes and its prognostic impact in an increasingly vaccinated population. The optimal clinical management of hrHPV-other associated HNSCCs is still unclear; however, improved understanding of their unique pathogenetic mechanisms would facilitate the development of rationally designed targeted therapies including immunotherapies. In the meantime, caution should be exercised when extending knowledge based on HPV16 to other hrHPV genotypes.

Supplementary Material

Figure 6. Expression profiles of immune checkpoint pathways in HPV16+ and HPV33+ HNSCC.

Heat maps for co-inhibitory receptors and ligands were plotted with unsupervised clustering within HPV16+ and HPV33+ groups using log2 normalized RSEM.

Highlights.

HPV33+ HNSCC has a worse overall survival compare to HPV16+ HNSCC

The APOBEC associated mutation signature was higher in HPV16+ than HPV33+ HNSCC

Aneuploidy was higher in HPV33+ HNSCC than in HPV16+ HNSCC

CD8 T-cell infiltration was reduced in HPV33+ compared to HPV16+ tumors

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported, in part, by the National Institute of Craniofacial and Dental Research and the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award numbers R01DE023555 and R01CA193590, and Seidman Cancer Center, University Hospitals.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Brown DR, Schroeder JM, Bryan JT, Stoler MH, Fife KH. Detection of Multiple Human Papillomavirus Types in Condylomata Acuminata Lesions from Otherwise Healthy and Immunosuppressed Patients. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37(10):3316–3322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wiatrak BJ, Wiatrak DW, Broker TR, Lewis L. Recurrent Respiratory Papillomatosis: A Longitudinal Study Comparing Severity Associated With Human Papilloma Viral Types 6 and 11 and Other Risk Factors in a Large Pediatric Population. The Laryngoscope. 2004;114(S104):1–23. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.000148224.83491.0f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daling JR, Madeleine MM, Johnson LG, et al. Human papillomavirus, smoking, and sexual practices in the etiology of anal cancer. Cancer. 2004;101(2):270–280. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walboomers JMM, Jacobs MV, Manos MM, et al. Human papillomavirus is a necessary cause of invasive cervical cancer worldwide. J Pathol. 1999;189(1):12–19. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fakhry C, Westra WH, Li S, et al. Improved Survival of Patients With Human Papillomavirus-Positive Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma in a Prospective Clinical Trial. JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100(4):261–269. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goodman MT, Saraiya M, Thompson TD, et al. Human Papillomavirus Genotype and Oropharynx Cancer Survival in the United States. Eur J Cancer Oxf Engl 1990. 2015;51(18):2759–2767. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.09.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Varier I, Keeley BR, Krupar R, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of oropharyngeal carcinoma related to high-risk non–human papillomavirus16 viral subtypes. Head Neck. 2016;38(9):1330–1337. doi: 10.1002/hed.24442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mazul AL, Rodriguez-Ormaza N, Taylor JM, et al. Prognostic significance of non-HPV16 genotypes in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2016;61:98–103. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2016.08.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fossum GH, Lie AK, Jebsen P, Sandlie LE, Mork J. Human papillomavirus in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma in South-Eastern Norway: prevalence, genotype, and survival. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2017;274(11):4003–4010. doi: 10.1007/s00405-017-4748-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lingen MW, Xiao W, Schmitt A, et al. Low etiologic fraction for high-risk human papillomavirus in oral cavity squamous cell carcinomas. Oral Oncol. 2013;49(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2012.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Castillo A, Koriyama C, Higashi M, et al. Human papillomavirus in upper digestive tract tumors from three countries. World J Gastroenterol WJG. 2011;17(48):5295–5304. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i48.5295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zammit AP, Sinha R, Cooper CL, Perry CFL, Frazer IH, Tuong ZK. Examining the contribution of smoking and HPV towards the etiology of oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma using high-throughput sequencing: A prospective observational study. Tornesello ML, ed. PLOS ONE. 2018;13(10):e0205406. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0205406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bratman SV, Bruce JP, O’Sullivan B, et al. Human Papillomavirus Genotype Association With Survival in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2(6):823. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.6587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu J, Lichtenberg T, Hoadley KA, et al. An Integrated TCGA Pan-Cancer Clinical Data Resource to Drive High-Quality Survival Outcome Analytics. Cell. 2018;173(2):400–416.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.02.052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Therneaus TM, Grambsch PM. Modeling Survival Data: Extending the Cox Model. New York: Springer; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wickham H Ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ellrott K, Bailey MH, Saksena G, et al. Scalable Open Science Approach for Mutation Calling of Tumor Exomes Using Multiple Genomic Pipelines. Cell Syst. 2018;6(3):271–281.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2018.03.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim J, Mouw KW, Polak P, et al. Somatic ERCC2 Mutations Are Associated with a Distinct Genomic Signature in Urothelial Tumors. Nat Genet. 2016;48(6):600–606. doi: 10.1038/ng.3557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mermel CH, Schumacher SE, Hill B, Meyerson ML, Beroukhim R, Getz G. GISTIC2.0 facilitates sensitive and confident localization of the targets of focal somatic copy-number alteration in human cancers. Genome Biol. 2011;12(4):R41. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-4-r41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davoli T, Uno H, Wooten EC, Elledge SJ. Tumor aneuploidy correlates with markers of immune evasion and with reduced response to immunotherapy. Science. 2017;355(6322):eaaf8399. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf8399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoadley KA, Yau C, Hinoue T, et al. Cell-of-Origin Patterns Dominate the Molecular Classification of 10,000 Tumors from 33 Types of Cancer. Cell. 2018;173(2):291–304.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.03.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taylor AM, Shih J, Ha G, et al. Genomic and Functional Approaches to Understanding Cancer Aneuploidy. Cancer Cell. 2018;33(4):676–689.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2018.03.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luo W, Friedman MS, Shedden K, Hankenson KD, Woolf PJ. GAGE: generally applicable gene set enrichment for pathway analysis. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10:161. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Racle J, de Jonge K, Baumgaertner P, Speiser Daniel E., Gfeller David. Simultaneous enumeration of cancer and immune cell types from bulk tumor gene expression data. eLife. 2017;6:e26476. doi: 10.7554/elife.26476.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Warren CJ, Westrich JA, Van Doorslaer K, Pyeon D. Roles of APOBEC3A and APOBEC3B in Human Papillomavirus Infection and Disease Progression. Viruses. 2017;9(8). doi: 10.3390/v9080233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Faden DL, Thomas S, Cantalupo PG, Agrawal N, Myers J, DeRisi J. Multi-modality analysis supports APOBEC as a major source of mutations in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2017;74:8–14. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2017.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gross AM, Orosco RK, Shen JP, et al. Multi-tiered genomic analysis of head and neck cancer ties TP53 mutation to 3p loss. Nat Genet. 2014;46(9):939–943. doi: 10.1038/ng.3051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ang KK, Harris J, Wheeler R, et al. Human Papillomavirus and Survival of Patients with Oropharyngeal Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(1):24–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0912217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gillison ML, Zhang Q, Jordan R, et al. Tobacco Smoking and Increased Risk of Death and Progression for Patients With p16-Positive and p16-Negative Oropharyngeal Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(17):2102–2111. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.4099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O’Sullivan B, Huang SH, Siu LL, et al. Deintensification Candidate Subgroups in Human Papillomavirus–Related Oropharyngeal Cancer According to Minimal Risk of Distant Metastasis. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(5):543–550. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.0164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sedghizadeh PP, Billington WD, Paxton D, et al. Is p16-positive oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma associated with favorable prognosis? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Oral Oncol. 2016;54:15–27. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2016.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weinberger DM, Malley R, Lipsitch M. Serotype replacement in disease following pneumococcal vaccination: A discussion of the evidence. Lancet. 2011;378(9807):1962–1973. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62225-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roberts SA, Lawrence MS, Klimczak LJ, et al. An APOBEC cytidine deaminase mutagenesis pattern is widespread in human cancers. Nat Genet. 2013;45(9):970–976. doi: 10.1038/ng.2702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mandal R, Şenbabaoğlu Y, Desrichard A, et al. The head and neck cancer immune landscape and its immunotherapeutic implications. JCI Insight. 2016;1(17). doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.89829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lyford-Pike S, Peng S, Young GD, et al. Evidence for a Role of the PD-1:PD-L1 Pathway in Immune Resistance of HPV-Associated Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2013;73(6):1733–1741. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ferris RL, Blumenschein G, Fayette J, et al. Nivolumab for Recurrent Squamous-Cell Carcinoma of the Head and Neck. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(19):1856–1867. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1602252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cohen EEW, Soulières D, Le Tourneau C, et al. Pembrolizumab versus methotrexate, docetaxel, or cetuximab for recurrent or metastatic head-and-neck squamous cell carcinoma (KEYNOTE-040): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. The Lancet. 2019;393(10167):156–167. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31999-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yoo SH, Ock C-Y, Keam B, et al. Poor prognostic factors in human papillomavirus-positive head and neck cancer: who might not be candidates for de-escalation treatment? Korean J Intern Med. November 2018. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2017.397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.No JH, Sung M-W, Hah JH, et al. Prevalence and prognostic value of human papillomavirus genotypes in tonsillar squamous cell carcinoma: A Korean multicenter study: HPV Genotypes in Tonsillar Cancer. Cancer. 2015;121(4):535–544. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.DelaRosa-Martínez R, Sánchez-Garza M, López-Revilla R. HPV genotype distribution and anomalous association of HPV33 to cervical neoplastic lesions in San Luis Potosí, Mexico. Infect Agent Cancer. 2016;11. doi: 10.1186/s13027-016-0063-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.López-Revilla R, Martínez-Contreras LA, Sánchez-Garza M. Prevalence of high-risk human papillomavirus types in Mexican women with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and invasive carcinoma. Infect Agent Cancer. 2008;3:3. doi: 10.1186/1750-9378-3-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.