Abstract

Background

Severe Combined Immune Deficiency (SCID) is an inherited defect in lymphocyte development and function that results in life-threatening opportunistic infections in early infancy. Data on SCID from developing countries are scarce.

Objective

To describe clinical and laboratory features of SCID diagnosed at immunology centers across India.

Methods

A detailed case proforma in an Excel format was prepared by one of the authors (PV) and was sent to centers in India that care for patients with primary immunodeficiency diseases. We collated clinical, laboratory, and molecular details of patients with clinical profile suggestive of SCID and their outcomes. Twelve (12) centers provided necessary details which were then compiled and analyzed. Diagnosis of SCID/combined immune deficiency (CID) was based on 2018 European Society for Immunodeficiencies working definition for SCID.

Results

We obtained data on 277 children; 254 were categorized as SCID and 23 as CID. Male-female ratio was 196:81. Median (inter-quartile range) age of onset of clinical symptoms and diagnosis was 2.5 months (1, 5) and 5 months (3.5, 8), respectively. Molecular diagnosis was obtained in 162 patients - IL2RG (36), RAG1 (26), ADA (19), RAG2 (17), JAK3 (15), DCLRE1C (13), IL7RA (9), PNP (3), RFXAP (3), CIITA (2), RFXANK (2), NHEJ1 (2), CD3E (2), CD3D (2), RFX5 (2), ZAP70 (2), STK4 (1), CORO1A (1), STIM1 (1), PRKDC (1), AK2 (1), DOCK2 (1), and SP100 (1). Only 23 children (8.3%) received hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT). Of these, 11 are doing well post-HSCT. Mortality was recorded in 210 children (75.8%).

Conclusion

We document an exponential rise in number of cases diagnosed to have SCID over the last 10 years, probably as a result of increasing awareness and improvement in diagnostic facilities at various centers in India. We suspect that these numbers are just the tip of the iceberg. Majority of patients with SCID in India are probably not being recognized and diagnosed at present. Newborn screening for SCID is the need of the hour. Easy access to pediatric HSCT services would ensure that these patients are offered HSCT at an early age.

Keywords: severe combined immune deficiency, India, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, newborn screening, BCG

Introduction

Severe Combined Immune Deficiency (SCID) is an inborn error of immunity characterized by defect in T lymphocyte development and function. Children with SCID often develop life-threatening opportunistic fungal, bacterial, or viral infections in early infancy. SCID is considered a medical emergency and affected children often succumb to severe infections if diagnosis and definitive treatment are delayed. The estimated incidence of SCID is 1 in 50,000 to 100,000 live births (1). Recent data also suggest an incidence of SCID as high as 1 in 3,000 live births in countries with high consanguinity rates (2). However, due to lack of awareness and diagnostic facilities in developing countries, diagnosis is often missed. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) is the definitive management for SCID. Early diagnosis and management are essential for successful outcomes. Several countries such as United States of America, Israel, Germany, Switzerland, Sweden, Norway, Iceland, New Zealand, and Taiwan have initiated newborn screening for SCID based on quantification of T-cell receptor excision circles (TRECs) to facilitate early diagnosis (3).

Opportunistic infections in SCID are recurrent, typically start in early infancy, and result in failure to thrive. Common infection patterns seen in SCID include oral thrush, disseminated BCGosis, disseminated cytomegalovirus, and life-threatening bacterial and fungal infections. Non-infective manifestations of SCID include Omenn syndrome (OS), graft versus host reaction, autoimmunity, and hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (4). CD3+ T lymphocyte numbers are usually decreased in SCID (T-). However, in cases of maternal T-cell engraftment or OS, CD3+ T cell numbers can be normal or increased. The expanded T cells are autoreactive in OS, whereas, they are alloreactive in cases with transplacental-acquired maternal T-cell engraftment. T lymphocyte function and naïve T cell numbers are reduced in such cases. T- SCID can be classified based on presence or absence of B lymphocytes and natural killer cells as T-B-NK+, T-B-NK-, T-B+NK-, and T-B+NK+. Combined immunodeficiencies (CID) are also characterized by presence of opportunistic infections and immune dysregulation; however, the age of onset is little older and have a milder immunodeficiency compared to SCID (5).

Until date, 58 different monogenic defects have been identified to result in immunodeficiencies affecting both cellular and humoral immunity and 18 amongst these are known to result in SCID (5). Molecular defects in SCID can be broadly classified as abnormalities in VDJ recombination (RAG1, RAG2, DCLRE1C, NHEJ1, LIG4, PRKDC), abnormalities of cytokine signaling (IL2RG, JAK3, IL7RA), toxic metabolite accumulation (ADA, PNP), defective survival of hematopoietic precursors (AK2, RAC2), abnormalities of T-cell receptor and signaling (PTPRC, CD3D, CD3E, CD3Z, LAT), and abnormalities of actin cytoskeleton (CORO1A). While X-linked SCID due to defect in IL2RG is considered to be the commonest form of SCID in the US, Canada, and Europe, autosomal recessive form of SCID due to defects in RAG1/2 are the commonest forms of SCID in countries where consanguinity rates are high (6–8). However, after initiation of newborn screening program, defects in RAG1/RAG2 are now increasingly being identified even in countries like US and Canada where consanguinity rates are low (9).

Reports of clinical data and outcomes of SCID from developing nations are scarce. Being a tropical nation with universal coverage of BCG vaccination in newborns, microbiological pattern of infections in SCID in India is expected to be different from other cohorts. Molecular spectrum is also expected to be different considering high rates of consanguinity and endogamous marriages in India (6–8). A recent cohort of 57 patients from Mumbai, India showed a high incidence of autosomal recessive forms of SCID with RAG1/2 defects being the commonest (7). We aim to describe the clinical, immunological, and molecular features of children with SCID in this large multicentric cohort from India.

Methods

A detailed case proforma in an Excel format was prepared by one of the authors (PV) and was sent to centers that are recognized as Foundation for Primary Immunodeficiency Diseases (FPID) centers for care of primary immunodeficiencies in India. The format was also sent to tertiary-care centers that manage patients with primary immunodeficiency diseases (PIDs). Information on clinical, laboratory, and molecular details of patients with SCID and their outcomes was sought and collated. Twelve (12) centers provided details of 319 patients that were then compiled and analyzed. Fifteen (15) patients from 2 other centers with either flow-cytometry or mutation-proven SCID are not included in final analysis as data were incomplete. Twenty-three (23) children did not fulfil the criteria for clinical definition for SCID and were not included for analysis. Duplicate entries (n=4) were also noted and excluded.

Data of 277 children who had a clinical profile suggestive of SCID were taken for final analysis ( Supplementary Table 1 ). Children were categorized as SCID/OS/CID/atypical SCID as per the European Society for Immunodeficiencies (ESID) working definition (10). Three (3) patients were classified as possible SCID as they did not fulfil the complete ESID definition, however, the treating team had a high index of suspicion based on clinical and immunological features ( Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Clinical and immunological features of children with clinical features suggestive of SCID in our cohort.

| S No | Age/Sex | Clinical features | Organisms isolated | Absolute lymphocyte count | Immunoglobulin profile | Lymphocyte subsets | Molecular defect | ESID Working Definition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pt. 1 | 8 months/male | Recurrent episodes of diarrhea, failure to thrive, pneumonia, meningitis | Stool: Clostridium difficile toxin assay positive | 2.260 | IgG <1.64 g/L IgA <0.36 g/L IgM- 0.25 g/L |

CD3- 0.3% (No: 6-7) CD19- 66% (No: 1492) CD56- 30% (No: 675) |

Not done | SCID |

| Pt. 2 | 5 months/male | Recurrent episodes of pneumonia, diarrhea, failure to thrive, elder male sibling expired at 6 months due to severe infections | Blood culture: Alcaligens faecalis | 0.410 | IgG <2.26 g/L IgA <0.1 g/L IgM<0.2 g/L |

CD3- 0.15% (No: 0-1) CD19- 0% (No: 0) CD56- 84% (No: 345) |

Not done | SCID |

| Pt. 3 | 6.5 months/male | Recurrent episodes of pneumonia, meningitis, hepatosplenomegaly, pancytopenia, transaminitis (HLH), 3 elder male siblings died at early infancy due to recurrent infections | Blood culture: Pseudomonas aeruginosa

Disseminated BCGosis and angioinvasive aspergillosis in lungs in autopsy |

0.940 | IgG<2.99 g/L IgA- 0.49 g/L IgM- 0.88 g/L |

CD3- 0% CD19- 86% (808) CD56- 0.3% |

IL2RG | SCID |

| Pt. 4 | 5 months/male | 2 episodes of pneumonia, recurrent diarrhea, umbilical sepsis, failure to thrive, 3 elder male siblings died at early infancy due to recurrent infections | N.A. | 2.050 | IgG- 2.64 g/L IgA <0.46 g/L IgM- 0.18 g/L |

CD3- 0% CD19- 96.1% (1968) CD56- 0% |

IL2RG | SCID |

| Pt. 5 | 3 months/male | Erythroderma, generalized adenopathy, diarrhea, lymphocytosis, eosinophilia (Omenn syndrome), failure to thrive, elder male sibling died due to eczema and pneumonia at 3rd month | N.A. | 18.540 | N.A. | CD3- 70.94% (13,124) CD19- 0.1% CD56- 7% (1,295) |

RAG2 | Omenn syndrome |

| Pt. 6 | 6 months/male | Persistent pneumonia, oral thrush, 7 maternal uncles died at early infancy due to recurrent infections | N.A. | 2.322 | IgG- 0.65 g/L IgA- 0.22 g/L IgM- 0.24 g/L |

CD3- 0% CD19- 96.75% (2,245) CD56- 3.2% (74) |

IL2RG | SCID |

| Pt. 7 | 3 months/male | Recurrent episodes of pneumonia, diarrhea, meningitis, generalized erythroderma (incomplete Omenn), elder male sibling died at early infancy due to rash and pneumonia | N.A. | 1.566 | IgG- 2.14 g/L IgM- 0.24 g/L |

CD3- 74.79% (1167) CD19- 0.27% (42) CD56- 23% (360) CD3+45RA+ 45RO-: 18.65% compared to 82% in control |

Not done | Omenn syndrome |

| Pt. 8 | 10 months/male | Recurrent episodes of diarrhea, pneumonia, otitis media, failure to thrive, BCG site ulceration, hepatosplenomegaly, generalized adenopathy, erythroderma, eosinophilia (Omenn syndrome), 5 maternal uncles died at early infancy due to recurrent infections | Disseminated BCGosis, disseminated Mycobacterium avium, disseminated CMV, and Aspergillus pneumonia in autopsy | 3.600 | IgG- 1.04 g/L IgA- 0.07 g/L IgM- 0.31 g/L IgE- 700 U/L (Normal: 0.-6 U/L) |

CD3- 95.79% (3,448) CD19- 0.2% (7) CD56- 1% (36) |

IL2RG | Omenn syndrome |

| Pt. 9 | 2 months/female | Recurrent episodes of oral thrush, failure to thrive, 1 elder male sibling expired due to sepsis in early infancy | N.A. | 0.648 | IgG- 2.72 g/L IgA- 0.09 g/L IgM- 0.41 g/L |

CD3- 1.1% (7) CD19- 0.2% (1) CD56- 93.6% (607) |

DCLRE1C | SCID |

| Pt. 10 | 3 months/male | Recurrent episodes of pneumonia, diarrhea, rickets, nephrocalcinosis, distal renal tubular acidosis, oral thrush, failure to thrive | N.A. | 0.896 | IgG- 0.88 g/L IgA <0.06 g/L IgM- 0.19 g/L |

CD3- 1.1% (10) CD19- 92.2% (8,26) CD56- 6.4% (57) |

IL7RA | SCID |

| Pt. 11 | 6 months/male | Pustulosis, hepatosplenomegaly, BCG site ulceration, transfusion-associated GVHD, elder male sibling died at 5 months due to pneumonia | Disseminated BCGosis, Blood culture: Enterobacter sp. | 1.462 | N.A. | CD3- 1.25% (183) CD19- 95% (1389) CD56- 0.45% (6-7) |

No gene variants found in IL2RG, JAK3, RAG1, RAG2 | SCID |

| Pt. 12 | 4 months/male | Recurrent episodes of pneumonia, diarrhea, failure to thrive, meningitis, oral thrush, hepatosplenomegaly, rash, eosinophilia (Omenn phenotype), one elder female sibling expired in early infancy | Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia, disseminated CMV in autopsy | 4.176 | IgG- 2.06 g/L IgA- 0.08 g/L IgM- 0.41 g/L |

CD3- 71.6% (2,993) CD19- 1.0% (42) CD56- 12% (504) CD3+45RO-45RA+: 24% as compared to 82% in control |

Not done | Omenn syndrome |

| Pt. 13 | 6 months/male | Persistent pneumonia, diarrhea, oral thrush, erythematous rash, hepatosplenomegaly (incomplete Omenn), nephrotic range proteinuria, two elder siblings (one male and other female) expired in early infancy | Blood culture: Acinetobacter sp.; Pneumonia and meningitis due to Aspergillus sp. and ventriculitis due to CMV in autopsy | 1.404 | IgG- 2.46 g/L IgA- 0.37 g/L IgM- 1.38 g/L |

CD3- 93.7% (1,312) CD19- 0.2% (3) CD56- 5.6% (78) |

Not done | Omenn syndrome |

| Pt. 14 | 7 months/male | Recurrent pneumonia, failure to thrive, oral thrush | Endotracheal aspirate: Klebsiella sp.; RSV pneumonia and disseminated CMV in autopsy | 0.156 | IgG- 7.86 g/L IgA- 0.61 g/L IgM <0.11 g/L |

CD3- 45.7% (72) CD19- 1.6% (2-3) CD56- 21.7% (34) |

PNP | SCID |

| Pt. 15 | 6 months/male | Recurrent episodes of pneumonia, failure to thrive, 5 elder siblings died at early infancy | N.A. | 1.391 | IgG <0.93 g/L IgA <0.16 g/L IgM <0.11 g/L |

CD3- 0% CD19- 0% CD56- 92.2% (1,291) |

RAG2 | SCID |

| Pt. 16 | 6 months/female | Recurrent pneumonia, diarrhea, failure to thrive, hepatosplenomegaly | Blood culture: Candida sp. | 0.785 | IgG- 6.33 g/L IgA- 0.07 g/L IgM <0.11 g/L |

CD3- 0.2% (1-2) CD19- 38.9% (312) CD56- 52.2% (407) |

IL7RA | SCID |

| Pt. 17 | 4 months/male | Recurrent pneumonia, pus discharging sinuses in neck, generalized rash (incomplete Omenn), 3 elder siblings (one female and 2 male) died in early infancy | CMV PCR+, Blood culture: Enterococcus cloacae | 1.800 | IgG <0.95 g/L IgA <0.17 g/L IgM- 0.12 g/L |

CD3- 83.3% (1,499) CD19- 0.2% (3-4) CD56- 14.3% (257) CD3+45RO-45RA+: 27.5% compared to 82% in control |

RAG2 | Omenn syndrome |

| Pt. 18 | 9 months/male | 2 episodes of pneumonia, failure to thrive, meningoencephalitis and hydrocephalus, MRI Brain: multiple tuberculomas noted over parietal and occipital area, 2 elder male siblings expired in early infancy | N.A. | 0.612 | IgG <0.95 g/L IgA <0.17 g/L IgM <0.15 g/L |

CD3- 4.2% CD19- 0.2% CD56- 85% |

RAG1 | SCID |

| Pt. 19 | 2 months/male | Recurrent episodes of pneumonia, failure to thrive | N.A. | 0.655 | IgG- 2.02 g/L IgA <0.16 g/L IgM <0.11 g/L |

CD3- 0% CD19- 0.13% (1) CD56- 72% (468) |

RAG1 | SCID |

| Pt. 20 | 5 months/male | Generalized rash, alopecia, loose stools (incomplete Omenn), failure to thrive, meningitis | N.A. | 1.372 | IgA <0.17 g/L IgM <0.12 g/L |

CD3- 69.6% (954) CD19- 0.15% (2) CD56- 10.7% (147) |

DCLRE1C | Omenn syndrome |

| Pt. 21 | 5 months/male | Younger sibling of Pt. 15, recurrent episodes of pneumonia, diarrhea, failure to thrive | CMV DNA PCR positive | 0.480 | IgG <0.94 g/L IgA- 0.18 g/L IgM <0.12 g/L |

CD3- 21.7% (109) CD19- 1% (5) CD56- 86% (430) |

RAG2 | SCID |

| Pt. 22 | 1.5 months/male | Persistent pneumonia, diarrhea, elder female sibling expired at early infancy | Blood culture: Candida sp. | 0.328 | IgG <2.02 g/L IgA <0.17 g/L |

CD3- 75% (248) CD19- 8.3% (27) CD56- 7.1% (23) |

ADA | SCID |

| Pt. 23 | 5 months/male | Oral thrush, pneumonia, meningitis, one elder female sibling expired due to anemia and pneumonia in early infancy | Disseminated CMV and early invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in autopsy | 0.788 | IgG- 2.49 g/L | CD3- 0.79% (6) CD19- 1.02% (8) CD56- 92.7% (744) |

RAG1 | SCID |

| Pt. 24 | 2 years/male | Recurrent pneumonia, diarrhea, otitis media, failure to thrive, esophageal candidiasis | N.A. | 8.567 | IgG- 5.19 g/L IgA <0.17 g/L IgM- 0.85 g/L |

CD3- 25.76% (2,236) CD3+CD4+- 33.5% (737) CD3+CD8+- 50.2% (1,104) CD19- 51.95% (4,451) CD56- 11.6% (994) CD3+45RA+45RO-: 31.7% compared to 74% in control |

No gene variants found | CID |

| Pt. 25 | 4 months/male | Younger sibling of pt. 8, recurrent episodes of pneumonia and diarrhea, failure to thrive | N.A. | 5.280 | IgG <2.05 g/L IgM <0.25 g/L |

CD3- 0.23% (12) CD19- 94.6% (4,995) CD56- 0.47% (25) |

IL2RG | SCID |

| Pt. 26 | 10 months/male | Recurrent episodes of pneumonia, failure to thrive | N.A. | 0.378 | N.A. | CD3- 2.7% CD19- 2.15% CD56- 85.2% |

DCLRE1C | SCID |

| Pt. 27 | 2.5 months/female | Recurrent pneumonia, otitis media, oral thrush, diarrhea, erythroderma, hepatosplenomegaly, eosinophilia (incomplete Omenn syndrome), elder female sibling expired in early infancy | N.A. | 1.650 | IgG- 1.23 g/L IgA <0.17 g/L IgM <0.25 g/L |

CD3- 7.67% (127) CD19- 0.69% (11) CD56- 82.7% (1,365) CD3+45RA+45RO-: 6.42% compared to 72% of control |

RAG2 | SCID/Omenn syndrome |

| Pt. 28 | 5 months/male | Recurrent episodes of pneumonia, failure to thrive | BAL: Pseudomonas sp.; Blood culture: Candida sp. | 0.360 | IgG <2.05 g/L IgA- 0.07 g/L IgM <0.05 g/L |

CD3- 2.3% (8) CD19- 3.8% (14) CD56- 92.2% (332) |

RAG1 | SCID |

| Pt. 29 | 8 months/female | Persistent pneumonia, recurrent episodes of diarrhea, failure to thrive, chorioretinitis, hepatosplenomegaly | Disseminated CMV; Blood culture: Acinetobacter baumanii | 1.316 | IgG- 4.17 g/L IgA- 0.22 g/L |

CD3- 11.3% (149) CD19- 69.8% (921) CD56- 1.75% (23) |

JAK3 | SCID |

| Pt. 30 | 1.5 months/male | Recurrent episodes of pneumonia, diarrhea, failure to thrive, elder male sibling died in early infancy | Blood culture: Acinetobacter baumanii | 0.204 | IgG- 1.96 g/L IgM <0.25 g/L |

CD3- 54% (108) CD19- 24% (48) CD56- 20% (40) |

ADA | SCID |

| Pt. 31 | 4 years/male | Recurrent episodes of pneumonia since early infancy, failure to thrive | N.A. | 0.116 | IgG- 4.73 g/L IgA- 1.05 g/L IgM- 1.12 g/L |

CD3- 64.8% (78) CD19- 4% (5) CD56- 7% (8-9) |

ADA | Atypical SCID |

| Pt. 32 | 9 months/male | Recurrent episodes of pneumonia, diarrhea, failure to thrive | N.A. | 0.154 | IgG- 2.27 g/L IgA- 0.27 g/L IgM <0.25 g/L |

CD3- 44.4% (67) CD19- 38.5% (58) CD56- 5.7% (9) |

Not done | SCID |

| Pt. 33 | 2 months/female | Recurrent episodes of pneumonia, diarrhea, failure to thrive | N.A. | 0.977 | IgG- 2.45 g/L IgA- 0.23 g/L IgM- 0.29 g/L |

CD3- 32% (314) CD19- 57% (559) CD56- 1.2% (12) |

Not done | SCID |

| Pt. 34 | 5 months/male | Recurrent diarrhea, failure to thrive, BCG site ulceration, pneumonia, erythroderma, eosinophilia, alopecia (Omenn syndrome) | Blood culture: Enterococcus sp.; Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia and disseminated BCGosis in autopsy | 2.498 | IgG <2.05 g/L IgM- 0.34 g/L IgE- 369 kU/L (up to 7.3) |

CD3- 78.01% (1,950) CD19- 4.44% (110) CD56- 13.12% (325) CD3+45RA+RO-: 2.26% compared to 83.7% in control CD3+HLA-DR+: 86.25% compared to 8.6% in control |

No gene variants found | Omenn syndrome |

| Pt. 35 | 6 months/male | Recurrent pneumonia, failure to thrive, elder male sibling expired in early infancy due to pneumonia | N.A. | 0.868 | N.A. | CD3- 3% (26) CD19- 94% (818) CD56- 0.4% (3) |

IL2RG | SCID |

| Pt. 36 | 1.5 months/female | Anasarca, nephrotic range proteinuria, pneumonia, failure to thrive, erythematous rash (incomplete Omenn), elder male sibling expired in early infancy | N.A. | 0.722 | IgG- 8.29 g/L IgA- 0.75 g/L |

CD3- 89% CD3+CD4+- 8% CD3+CD8+- 85.1% CD19- 0.3% CD56- 0.8% CD3+45RA+45RO-: 30% compared to 90% in control CD3+45RA-45RO+: 79.14% compared to 19.24% in control CD3+HLA-DR+: 90.13% compared to 12.7% in control |

ADA | Omenn syndrome |

| Pt. 37 | 5 months/female | Recurrent pneumonia, diarrhea, failure to thrive, BCG site ulceration | N.A. | 0.861 | IgG <2.0 g/L IgA <0.17 g/L |

CD3- 34% (292) CD3+CD4+- 29.7% (89) CD3+CD8+- 55.3% (165) CD19- 45% (387) CD56- 12.1% (103) |

Not done | SCID |

| Pt. 38 | 5 months/male | Recurrent pneumonia, diarrhea, failure to thrive | N.A. | 0.140 | N.A. | CD3- 9.6% (13) CD19- 8.7% (12) CD56- 80% (112) |

RAG1 | SCID |

| Pt. 39 | 2 months/male | Recurrent episodes of diarrhea, failure to thrive, sacral abscess, 2 elder siblings died in early infancy due to repeated infections | Blood culture: Staphylococcus aureus; Disseminated CMV in autopsy | 0.06 | N.A. | CD3- 50% (30) CD19- 7.7% (4-5) CD56- 34.6% (21) |

ADA | SCID |

| Pt. 40 | 2.5 months/male | Recurrent pneumonia, otitis media, failure to thrive, 6 maternal uncles and 2 elder male siblings died at early infancy due to repeated infections | N.A. | 1.406 | N.A. | CD3- 0.07% (01) CD19- 91.5% (1,598) CD56- 1.8% (33) |

Not done | SCID |

| Pt. 41 | 4 years/female | Eczematoid eruptions and chronic otitis media since early infancy, autoimmune hemolytic anemia, generalized adenopathy | N.A. | 1.922 | IgG- 21.56 g/L IgA- 4.77 g/L IgM- 0.57 g/L IgE- 933 U/L (Normal: up to 60) |

CD3- 24.79% (912) CD3+CD4+- 21.2% (193) CD3+CD8+- 55% (500) CD19- 42.3% (812) CD56- 2.7% (58) CD3+45RA+RO-: 45% compared to 76% in control CD3+CD4+45RA+RO-: 14.9% compared to 67% in control CD3+CD8+45RA+45RO-: 35.8% compared to 72% in control |

STK4 | CID |

| Pt. 42 | 4 months/male | Recurrent pneumonia, diarrhea, failure to thrive, oral thrush, 1 maternal uncle died at 2 years due to repeated infections | Blood culture: Moraxella sp. | 1.302 | N.A. | CD3- 1.3% (17) CD19- 85.16% (1,109) CD56- 2.9% (37) |

Not done | SCID |

| Pt. 43 | 2.5 months/male | Chronic diarrhea, failure to thrive, esophageal candidiasis, maternal cousin (male) expired at early infancy due to pneumonia | N.A. | 0.415 | N.A. | CD3- 3.8% (15) CD19- 84% (336) CD56- 3% (12) |

IL2RG | SCID |

| Pt. 44 | 3 months/male | Recurrent pneumonia, diarrhea, failure to thrive, erythroderma, eosinophilia, hepatosplenomegaly (maternal T cell engraftment), 1 maternal uncle died at early infancy due to pneumonia | Blood culture: Weisella confusa | 7.457 | N.A. | CD3- 15.9% (1,192) CD19- 76.4% (5,692) CD56- 1.9% (142) CD3+45RA+RO-: 5.43% compared to 59% in control CD3+45RA-45RO+: 96.9% compared to 60% in control CD3+HLA-DR+: 83.5% compared to 15.7% in control |

IL2RG | Atypical SCID |

| Pt. 45 | 4 months/male | Recurrent pneumonia, diarrhea, failure to thrive, oral thrush, BCG site ulceration | N.A. | 2.831 | IgG <0.87 g/L IgA <0.16 g/L |

CD3- 0.2% (5-6) CD19- 97.7% (2,765) CD56- 0.48% (13-14) |

No gene variants found | SCID |

| Pt. 46 | 5 months/male | Recurrent fever, BCG site ulceration, hepatosplenomegaly, oral thrush | Disseminated BCGosis | 2.086 | IgG <1.46 g/L | CD3- 0.6% (13) CD19- 97.8% (2,044) CD56- 0.2% (4) |

Not done | SCID |

| Pt. 47 | 15 days/male | Younger sibling of pt. 31, pneumonia, recurrent diarrhea, failure to thrive | Blood culture: Candida sp. | 0.094 | N.A. | CD3- 42% (38) CD19- 40% (36) CD56- 16% (14) |

ADA | SCID |

| Pt. 48 | 4 months/male | Younger sibling of pt. 27, recurrent pneumonia, diarrhea, failure to thrive, erythroderma, hepatosplenomegaly, eosinophilia (Omenn syndrome) | N.A. | 1.896 | N.A. | CD3- 74% (1,406) CD19- 0.4% (8) CD56- 22% (418) CD3+45RA+45RO-: 16% compared to 71% in control |

RAG2 | Omenn syndrome |

| Pt. 49 | 3 years/male | Recurrent sinopulmonary infections, diarrhea, failure to thrive, 1 episode of liver abscess, intra-cranial B cell lymphoma, defective T lymphocyte proliferation on stimulation with PHA. | N.A. | 3.265 | IgG- 4.02 g/L | CD3- 45.14% (1,467) CD3+CD4+- 6.9% (103) CD3+CD8+- 70.3% (1,033) CD19- 6.83% (222) CD56- 25.01% (816) CD3+45RA+45RO-: 71.06% compared to 64% in control CD3+CD4+45RA+45RO-: 3.6% compared to 72% in control CD3+CD8+45RA+45RO-: 75.3% compared to 68% in control |

CORO1A | Atypical SCID |

| Pt. 50 | 6 months/male | Recurrent episodes of pneumonia, failure to thrive | N.A. | 0.411 | IgG <0.95 g/L IgA <0.17 g/L IgM <0.25 g/L |

CD3- 20% (80) CD19- 73% (292) CD56- 1.4% (5-6) |

JAK3 | SCID |

| Pt. 51 | 10 months/male | Pneumonia, diarrhea, failure to thrive, meningoencephalitis | Endotracheal aspirate: Klebsiella pneumoniae | 0.810 | IgG <0.95 g/L IgA <0.17 g/L IgM <0.25 g/L |

CD3- 4% (32) CD19- 95% (760) CD56- 1% (8) |

IL2RG | SCID |

| Pt. 52 | 3 months/male | Recurrent pneumonia, diarrhea, failure to thrive | N.A. | 0.199 | N.A. | CD3- 0.82% (2) CD19- 1.17% (2-3) CD56- 88.9% (178) |

DCLRE1C | SCID |

| Pt. 53 | 5 months/male | Pneumonia, failure to thrive, complicated otitis media with facial nerve palsy, transfusion-associated GVHD | N.A. | 0.292 | N.A. | CD3- 0.2% (0-1) CD19- 29% (87) CD56- 60% (180) |

Not done | SCID |

| Pt. 54 | 3.5 years/male | Severe eczema since early infancy, pustules, otitis media, pneumonia, chest wall abscess, eosinophilia (incomplete Omenn) | Pus culture- Staphylococcus aureus | 1.244 | IgG- 1.64 g/L IgA- 1.56 g/L IgE- 4269 kU/L (upto 32) IgG1- 1.01 g/L IgG2- 0.95 g/L IgG3- 0.23 g/L IgG4- 0.71 g/L |

CD3- 60% (744) CD3+CD4+- 17.3% (128) CD3+CD8+- 71.5% (529) CD19- 2.3% (28) CD56- 15% (186) CD3+45RA-45RO-: 36.6% compared to 65% in control CD3+45RA-45RO+: 67% compared to 31% in control CD3+HLA-DR+: 64.2% compared to 19.3% in control |

No gene variants found | Omenn syndrome |

| Pt. 55 | 5 months/male | Recurrent pneumonia, diarrhea, failure to thrive, hyperferritinemia, hypofibrinogenemia, pancytopenia (HLH) | ET aspirate: Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumanii; PCR positivity for H1N1 | 1.547 | IgG- 2.32 g/L IgA <0.2 g/L IgM- 0.22 g/L |

CD3- 1.74% (27) CD19- 91.6% (1,426) CD56- 5% (78) |

IL2RG | SCID |

| Pt. 56 | 6 months/female | Pneumonia, failure to thrive, diarrhea, BCG site ulceration | N.A. | 1.098 | IgG- 0.54 g/L IgA <0.2 g/L IgM <0.17 g/L |

CD3- 0% (0) CD19- 2% (22) CD56- 79% (869) |

DCLRE1C | SCID |

| Pt. 57 | 7 months/male | Pneumonia, diarrhea, failure to thrive, hepatosplenomegaly, BCG site ulceration | N.A. | 0.855 | N.A. | CD3- 5.1% (43) CD19- 77.5% (667) CD56- 17% (146) |

Not done | SCID |

| Pt. 58 | 11 months/male | Recurrent pneumonia, failure to thrive, hepatosplenomegaly, generalized adenopathy, BCG site ulceration, erythematous rash (incomplete Omenn), meningitis with hydrocephalus | Disseminated BCGosis, CMV DNA PCR positive, Endotracheal aspirate: Klebsiella pneumoniae | 1.832 | IgG- 7.74 g/L IgA- 0.36 g/L IgM- 2.42 g/L |

CD3- 68% (1,244) CD3+CD4+- 7.8% (97) CD3+CD8+- 45.1% (558) CD19- 5.6% (102) CD56- 23.5% (430) CD3+CD4+45RA-45RO+: 90.4% compared to 30.2% in control CD3+HLA-DR+: 67.9% compared to 5.8% in control |

RAG1 | Omenn syndrome |

| Pt. 59 | 5 months/male | BCG site ulceration, persistent diarrhea, generalized papular rash | M. bovis | 0.931 | IgA<0.10 g/L | CD3- <1% CD19- 97% (902) CD56- <1% |

IL2RG | SCID |

| Pt. 60 | 6 months/male | BCG site ulceration, oral thrush, septicemia | Candida sp. | 2.129 | N.A | CD3- 29% (617) CD19- 62% (1320) CD56- 8% (170) |

No gene variants identified | SCID |

| Pt.61 | 5 months/female | BCG site ulceration, pneumonia, erythroderma, alopecia, CMV DNA PCR- positive | CMV, M. bovis | 1.144 | IgG-9.03 g/L IgA-0.17 g/L IgM-0.41 g/L |

CD3-70.70% (806) CD19-0.14% (2) CD56-17.70% (202) CD3+45RA+-12.57% compared to 86% in control |

RAG2 | Omenn syndrome |

| Pt. 62 | 4 months/male | Severe pneumonia, CT chest: diffuse bilateral ground glass opacities with multifocal consolidation | Nil | 0.507 | IgG- <2.02 g/L IgA- <0.17 g/L IgM- <25 g/L |

CD3- 57.23% (290) CD19-0.05% (1) CD56-35.08% (179) |

RAG1 | SCID |

| Pt. 63 | 5 months/male | Severe pneumonia, CT chest: bilateral small random nodules | Nil | 1.236 | IgG- <2.03 g/L IgA- <0.17 g/L IgM- <0.25 g/L |

CD3- 0.28% (4) CD19-96.20% (1193) CD56-0.51% (6) |

IL2RG | SCID |

| Pt. 64 | 5 months/female | Persistent pneumonia- pneumothorax, oral thrush | Candida sp. | 0.180 | IgG- <2.03 g/L IgA- <0.17 g/L IgM- 0.33 g/L |

CD3-0.16% (1) CD19-0.16% (1) CD56-74.40% (134) |

DCLRE1C | SCID |

| Pt. 65 | 1.5 months/female | Left ear complicated otitis media, pneumonia, diarrhea | S. aureus | 2.443 | IgG-8.04 g/L IgA-0.75 g/L IgM-1.38 g/L |

CD3-22.87% (559) CD19-73.60% (1776) CD56-1.43% (34) |

No gene variants identified | SCID |

| Pt. 66 | 7 months/male | BCG adenitis, encephalitis | M. bovis | 0.506 | IgG- <2.05 g/L IgA- <0.17 g/L IgM- <0.26 g/L |

CD3-18.19% (93) CD19-0.08% (1) CD56-77.24% (394) |

DCLRE1C | SCID |

| Pt. 67 | 8 months/female | Recurrent diarhea, failure to thrive, pneumonia, axillary adenopathy | Nil | 6.864 | IgG-<2.03 g/L IgM->4 g/L |

CD3-69.75% (4785) CD3+CD4+ - 32% of CD3+ lymphocytes (1530) CD3+CD8+ - 62% of CD3+ lymphocytes (2967) CD3+45RA+ - 24.3% compared to 85% in healthy control CD19-8.95% (617) CD56-2.57% (178) |

No gene variants identified | SCID |

| Pt. 68 | 10 months/male | recurrent gastroenteritis, pneumonia, DCT+ autoimmune hemolytic anemia | CMV | 2.200 | IgG-3.33 g/L IgA- <0.17 g/L IgM- 1.19 g/L |

CD3-86.75% (1910) CD19-0.64% (13) CD56-6.50% (143) CD3+CD45RA+ -38.2% compared to 79% in control |

NHEJ1 | Atypical SCID |

| Pt. 69 | 5 months/male | persistent pneumonia, absent BCG scar | Nil | 0.287 | IgG-3.47 g/L IgA- 0.21 g/L IgM-0.76 g/L |

CD3-51.62% (150) CD19-31.30% (91) CD56-9.46% (28) |

No gene variants identified | SCID |

| Pt. 70 | 4 months/male | Recurrent pneumonia, diarrhoea, generalized erythematous macular rash, CMV retinitis, seizures, GVHD skin lesions | CMV | 4.921 | IgG- <1.99 g/L IgA- <0.36 g/L IgM- <0.25 g/L |

CD3-0.54% (25) CD19-0.54% (25) CD56-91.74% (4512) |

DCLRE1C | SCID |

| Pt. 71 | 6 months/male | Recurrent pneumonia, otitis media, ulceration at BCG site, hepatosplenomegaly | Enterococcus sp. | 0.816 | IgA-0. 56 g/L | CD3-1.39% (12) CD19-90.95% (746) CD56-5.4% (44) |

IL2RG | SCID |

| Pt. 72 | 11 months/male | Skin pustule and abscess, generalized erythematous macular rash, oral thrush | Nil | 1.118 | IgG-<0.90 g/L IgA- <0.21 g/L |

CD3-24.80% (278) CD19-6.20% (69) CD56-67.6% (757) |

NHEJ1 | SCID |

| Pt. 73 | 3.5 months/male | Recurrent pneumonia, diarrhoea, generalized erythematous macular rash | Nil | 2.420 | IgG- 1.62 g/L IgA- 0.09 g/L IgM- 0.48 g/L |

CD3-5% (121) CD19- 47% (1137) CD56- 42% (1016) |

No gene variants identified | SCID |

| Pt. 74 | 3 months/male | Recurrent pneumonia, diarrhoea | Nil | 1.643 | IgG- 3.09 g/L IgA- <0.07 g/L |

CD3-87.90% (1442) CD19-1.7% (28) CD56-2.2% (33) CD3+45RA+ -1.6% compared to 78% in control |

ADA | Atypical SCID |

| Pt. 75 | 3 months/male | Recurrent pneumonia, diarrhoea, failure to thrive | Nil | 2.862 | IgG- 2.14 g/L IgA- <0.20 g/L |

CD3-35.90% (1026) CD19-3.11% (89) CD56- 38% (1087) |

No gene variants identified | SCID |

| Pt. 76 | 12 months/female | Recurrent pneumonia, diarrhoea, oral thrush | Nil | 4.300 | IgG- 3.28 g/L IgA- 1.46 g/L IgM- 2.99 g/L |

CD3-3.29% (142) CD19-79.37% (3414) CD56-9.63% (413) |

No gene variants identified | SCID |

| Pt. 77 | 1.5 months/female | Recurrent pneumonia, otitis media, generalized erythematous macular rash | Pichia fermentans; E. coli | 4.720 | IgG- 4.27 g/L IgA- <0.16 g/L IgM- 0.35 g/L |

CD3-49.03% (2303) CD19-1.27% (61) CD56-37.44% (1765) CD3+45RA+ - 1.46% compared to 73% in control |

RAG1 | Omenn syndrome |

| Pt. 78 | 6 months/male | Recurrent pneumonia, diarrhoea, generalized erythematous macular rash | Nil | 1.808 | IgG- <2.02 g/L IgA- 0.20 g/L IgM-1.71 g/L |

CD3-95.65% (1732) CD19-1.78% (32) CD56-0.53% (9) CD3+45RA+ - 11% compared to 86% in control |

IL2RG | Atypical SCID |

| Pt. 79 | 6.5 months/male | Recurrent pneumonia, diarrhoea | Nil | 0.600 | IgG- 3.65 g/L IgA- 0.38g/L IgM- 0.41 g/L |

CD3-29.54% (177) CD19-41.13% (247) CD56-18.87% (114) |

No gene variants identified | SCID |

| Pt. 80 | 15 months/male | Recurrent pneumonia, diarrhoea, oral thrush | Klebsiella pneumoniae, CMV | 7.191 | IgG-2.02 g/L IgA-0.18 g/L IgM-0.46 g/L |

CD3-12.36% (892) CD19-0.74% (53) CD56-51.5% (3703) CD3+45RA+ - 14.29% (decreased) |

No gene variants identified | SCID |

| Pt. 81 | 42 months/female | Recurrent pneumonia, oral thrush | Nil | 1.615 | IgG-21.77 g/L IgA-1.23 g/L IgM-1.81 g/L |

CD3-37.40% (606) CD4- 5.7% CD8- 14.7% CD19-22.6% (366) CD56- 46% (743) |

No gene variants identified | SCID |

| Pt. 82 | 3 months/male | Recurrent pneumonia, failure to thrive, oral thrush, one elder female sibling expired due to pneumonia in early infancy | Nil | 2.492 | IgG-2.72 g/L IgA-0.09 g/L IgM-0.73 g/L |

CD3-30% (747) CD19-9.10% (227) CD56- 41% (1021) |

No gene variants identified | SCID |

| Pt. 83 | 3 months/female | Recurrent pneumonia, diarrhoea, otitis media, oral thrush | Nil | 2.608 | IgG-<2.02 g/L IgA-<0.17 g/L IgM-0.90 g/L |

CD3-32.68% (853) CD19-29.79% (783) CD56-33.41% (872) CD3+ 45RA+ -2.23% (decreased) |

No gene variants identified | SCID |

| Pt. 84 | 4 months/male | Recurrent pneumonia, diarrhoea, otitis media, ulceration at BCG site | Nil | 0.663 | IgG-<2.02 g/L IgA-<0.17 g/L IgM-<0.25 g/L |

CD3-87.66% (579) CD19-0.05% (1) CD56-10.22% (66) |

RAG1 | SCID |

| Pt. 85 | 4 months/male | Recurrent pneumonia, severe erythroderma, developmental delay | Nil | 1.441 | IgG-<2.02 g/L IgA-<0.17 g/L |

CD3-0.16% (3) CD19-94.81% (1365) CD56-0.67% (10) |

IL2RG | SCID |

| Pt. 86 | 15 months/male | Recurrent pneumonia, generalized eczematoid macular rash, developmental delay, myopathy | Nil | 14.84 | IgG-13.16 g/L IgA-1.70 g/L IgM<0.26 g/L IgE- 8423 U/L |

CD3-92.20% (13,683) CD19-2.85% (416) CD56-3.21% (475) CD4+45RA+ - 12.17% compared to 56% in control CD8+45RA+ - 18.6% compared to 72% in control |

STIM1 | CID |

| Pt. 87 | 6 months/male | Recurrent pneumonia, extensive eczematoid rash | CMV | 6.556 | IgG-13.75 g/L IgA-0.42 g/L IgM-1.88 g/L IgE- 622 U/L |

CD3-53.90% (3536) CD4- 4.9% (320) CD8- 30.2% (1968) CD19-25.9% (1706) CD56-5.6% (368) |

No gene variants identified | Omenn syndrome |

| Pt. 88 | 2.5 months/female | Recurrent pneumonia, diarrhoea, BCG site abscess | Nil | 0.055 | IgG-2.33 g/L IgA<0.17 g/L IgM<0.25 g/L |

CD3-95.58% (48) CD19-0.07% (1) CD56-0.79% (1) |

ADA | SCID |

| Pt. 89 | 4 months/female | Recurrent diarrhoea, otitis media, generalized erythematous macular rash, ulceration at BCG site | Enterococcus faecalis | 2.352 | IgG<2.02 g/L IgM<0.21 g/L |

CD3-68.95% (1621) CD19-0.05% (1) CD56-25.37% (597) CD3+ 45RA+ -6.79% compared to 70% in control HLA DR in CD3+ - 74.2% compared to 15% in control |

RAG1 | Omenn syndrome |

| Pt. 90 | 4.5 months/male | Recurrent pneumonia, | Nil | 0.724 | IgG-<0.95 g/L IgA<0.17 g/L |

CD3-2.41% (17) CD19-0.45% (4) CD56-90.91% (655) |

DCLRE1C | SCID |

| Pt. 91 | 4 months/male | Recurrent pneumonia, chorioretinitis, failure to thrive, 3 maternal uncles died at early infancy due to severe infections | Blood CMV PCR positive | 1.760 | IgG < 2.7 g/L IgA <0.4 g/L IgM- 1.07 g/L |

CD3- 1% (18) CD19- 61% (1,098) CD56- 1% (18) |

IL2RG | SCID |

| Pt. 92 | 4 months/male | Oral thrush, pneumonia, failure to thrive | N.A. | 0.650 | N.A. | CD3- 0.4% (2-3) CD19- 97% (631) CD56- 0.4% (2-3) |

IL2RG | SCID |

| Pt. 93 | 6 months/female | Recurrent pneumonia, CMV chorioretinitis | Blood CMV PCR positive | 2.200 | IgG <2.7 g/L IgA <0.4 g/L IgM <0.25 g/L |

CD3- 7.6% (167) CD19- 1% (22) CD56- 40% (880) |

RAG2 | SCID |

| Pt. 94 | 4.5 months/male | Persistent pneumonia, failure to thrive, elder sibling died at 6 months due to severe pneumonia | N.A. | 1.750 | IgG <1.37 g/L IgA <0.26 g/L IgM <0.16 g/L |

CD3- 4% (70) CD19- 47% (823) CD56- 25% (438) |

IL7RA | SCID |

| Pt. 95 | 6 months/male | Recurrent pneumonia, failure to thrive | N.A. | 2.000 | IgG <1.37 g/L IgA <0.26 g/L IgM- 0.53 g/L |

CD3- 20% (400) CD19- 80% (1,600) CD56- 0.1% (2) |

IL2RG | SCID |

| Pt. 96 | 3 months/female | Oral thrush, septicemia | N.A. | 0.720 | IgG- 0.8 g/L IgA <0.26 g/L IgM <0.18 g/L |

CD3- 5% (36) CD19- 7% (50) CD56- 53% (382) |

RAG2 | SCID |

| Pt. 97 | 5 months/male | Recurrent episodes of pneumonia, diarrhea, failure to thrive, oral thrush, BCG site ulceration, elder female sibling expired at 6 months due to recurrent infections | N.A. | 0.850 | IgG <2.7 g/L IgA <0.4 g/L IgM <0.25 g/L |

CD3- 5% (43) CD19- 2.3% (20) CD56- 46% (391) |

Not done | SCID |

| Pt. 98 | 3 months/female | Recurrent pneumonia, failure to thrive | N.A. | 0.700 | IgG <2.7 g/L IgA <0.4 g/L IgM <0.25 g/L |

CD3- 6.5% (46) CD19- 3.6% (25) CD56- 34% (238) |

Not done | SCID |

| Pt. 99 | 3 months/female | Recurrent pneumonia, failure to thrive | N.A. | 0.680 | IgG- 0.65 g/L IgA <0.5g/L IgM <0.25 g/L |

CD3- 2% (14) CD19- 4% (27) CD56- 53% (360) |

DCLRE1C | SCID |

| Pt. 100 | 3.5 months/male | Persistent pneumonia, failure to thrive | N.A. | 4.911 | IgG- 0.82 g/L IgA <0.26 g/L IgM <0.18 g/L |

CD3- 9.4% (461) CD19- 0.4% (20) CD56- 90% (4,410) |

Not done | SCID |

| Pt. 101 | 6 months/female | Persistent pneumonia, failure to thrive | N.A. | 5.756 | IgG- 6.7 g/L IgA <0.26 g/L IgM- 0.78 g/L |

CD3- 2% (116) CD19- 41% (2,362) CD56- 47% (2,707) |

Not done | SCID |

| Pt. 102 | 7.5 months/male | Recurrent pneumonia, diarrhea, failure to thrive | N.A. | 0.750 | IgG- 0.76 g/L IgA- 0.08 g/L IgM- 0.08 g/L |

CD3- 26% (195) CD19- 67% (503) CD56- 6% (45) |

JAK3 | SCID |

| Pt. 103 | 1 month/male | Erythroderma, loss of eyelashes, eosinophilia (incomplete Omenn), failure to thrive, two siblings (one male and one female) expired in early infancy due to erythroderma, generalized lymphadenopathy, and severe infections | N.A. | 3.358 | IgG- 5.86 g/L IgA <0.26 g/L IgM- 0.36 g/L IgE >2,500 U/L |

CD3- 9% (302) CD19- 48% (1,613) CD56- 11% (370) |

No variants identified | Omenn syndrome |

| Pt. 104 | 5 months/female | Recurrent pneumonia, otitis media, failure to thrive, oral thrush, pancytopenia, hepatosplenomegaly, seizures, encephalopathy (HLH) | N.A. | 1.890 | IgG <2.7 g/L IgA <0.4 g/L IgM <0.25 g/L |

CD3- 32% (605) CD3+CD4+- 87% (528) CD3+CD8+- 13% (78) CD19- 65% (1,229) CD56- 3% (57) |

SP110 | SCID |

| Pt. 105 | 11 months/male | Chronic diarrhea, failure to thrive | Stool culture: Acinetobacter sp. | 0.691 | IgG- 3.0 g/L IgA- 0.52 g/L IgM- 0.39 g/L |

CD3- 13.6% (94) CD19- 56% (386) CD56- 28% (193) |

RAG1 | SCID |

| Pt. 106 | 4.5 months/male | Oral thrush, recurrent pneumonia, diarrhea, failure to thrive, BCG site ulceration, 3 maternal uncles died at early infancy due to repeated infections | N.A. | 0.900 | IgG- 1.1 g/L IgA- 0.05g/L IgM- 0.07g/L |

CD3- 5% (45) CD19- 91% (819) CD56- 2% (18) |

IL2RG | SCID |

| Pt. 107 | 5 months/male | Recurrent pneumonia, oral thrush, failure to thrive, BCG site ulceration, encephalopathy | N.A. | 1.120 | IgG <1.4g/L IgA <0.17g/L IgM <0.19g/L |

CD3- 6% (66) CD19- 92% (1,012) CD56- 1% (11) |

JAK3 | SCID |

| Pt. 108 | 8 months/male | Recurrent pneumonia, diarrhea, failure to thrive | N.A. | 0.380 | IgG <1.4g/L IgA <0.17g/L IgM <0.19g/L |

CD3- 0% CD19- 94% (357) CD56- 4% (15) |

IL7R | SCID |

| Pt. 109 | 4.5 months/male | Persistent pneumonia, failure to thrive | N.A. | 2.092 | IgG <1.4g/L IgA <0.17g/L IgM- 0.24g/L |

CD3- 0.8% (17) CD19- 98% (2,048) CD56- 0% |

Not done | SCID |

| Pt. 110 | 4.5 months/male | Persistent pneumonia, recurrent diarrhea, skin abscess, failure to thrive, situs inversus, one elder sibling died at early infancy due to pneumonia | N.A. | 0.780 | IgG- 1.92 g/L IgA- 0.04 g/L IgM- 0.02 g/L |

CD3- 0.04% CD19- 0.29% CD56- 96% |

Not done | SCID |

| Pt. 111 | 5.5 months/female | Recurrent pneumonia, failure to thrive, 3 elder male siblings died within first year of life due to severe infections | N.A. | 1.425 | IgG- 0.42 g/L IgA <0.03 g/L IgM- 0.34 g/L |

CD3- 1.2% (17) CD19- 71% (1,012) CD56- 25% (356) |

CD3D | SCID |

| Pt. 112 | 6 months/female | Recurrent pneumonia, failure to thrive | N.A. | 0.336 | IgG <1.36 g/L IgA <0.25 g/L IgM <0.18 g/L |

CD3- 0.2% (0-1) CD19- 0% CD56- 99% (335) |

Not done | SCID |

| Pt. 113 | 3.5 months/female | Recurrent pneumonia, failure to thrive, one elder female sibling died at 4 months due to a probable infection | N.A. | 2.210 | IgG <1.36 g/L IgA <0.25 g/L IgM <0.18 g/L |

CD3- 0.8% (18) CD19- 97.4% (2,153) CD56- 1% (22) |

No variants identified | SCID |

| Pt. 114 | 8 months/male | Recurrent pneumonia, BCG site ulceration, failure to thrive, one elder male sibling died at early infancy due to pneumonia | Disseminated BCGosis | 1.650 | IgG- 0.15 g/L IgA <0.24 g/L IgM- 0.2 g/L |

CD3- 0% CD19- 61% (1,007) CD56- 38% (627) |

IL7R | SCID |

| Pt. 115 | 7 months/female | Persistent pneumonia, failure to thrive, two elder siblings (one male, one female) died in early infancy due to severe infections, one had disseminated BCGosis | N.A. | 0.870 | IgG <2.0 g/L IgA <0.3 g/L IgM <0.2 g/L |

CD3- 15% (131) CD19- 0% CD56- 40% (350) |

DCLRE1C | SCID |

| Pt. 116 | 7 months/female | Persistent pneumonia, failure to thrive, autoimmune hemolytic anemia | Disseminated CMV, pulmonary aspergillosis | 1.700 | IgG- 3.2 g/L IgA- 0.38 g/L IgM- 0.4 g/L |

CD3- 4% (68) CD19- 0% CD56- 72% (1,224) |

RAG2 | SCID |

| Pt. 117 | 8 months/male | Recurrent pneumonia, persistent diarrhoea, BCG site ulceration | Disseminated BCGosis | 2.400 | IgG- 2.9 g/L IgA- 0.32 g/L IgM- 0.24 g/L |

CD3- 0% CD19- 70% (1,680) CD56- 24% (576) |

CD3E | SCID |

| Pt. 118 | 5 months/male | Recurrent pneumonia, failure to thrive | Pneumocystis jirovecii from endotracheal aspirate | 3.200 | IgG- 3.64 g/L IgA- 0.42 g/L IgM- 0.38 g/L |

CD3- 2% (64) CD19- 64% (2,048) CD56- 1% (32) |

IL2RG | SCID |

| Pt. 119 | 3.5 months/male | Recurrent pneumonia, septicemia | None | 0.064 | IgG- 1.49 g/L IgA- <0.26 g/L IgM- <0.16 g/L |

CD3- 63% (27) CD19- 2.4% (1) CD56- 2.4% |

ADA | SCID |

| Pt. 120 | 1 month 8 days/female | Recurrent pneumonia, cupping of ribs with blunting of lower end of scapula in radiology | None | 0.160 | IgG- 3.54 g/L IgA- <0.05 g/L IgM- <0.03 g/L |

CD3- 32% (51) CD19- 8.9% (14) CD56- 58% (93) |

ADA (probable); Gene sequencing not done | SCID |

| Pt. 121 | 10 months/male | Recurrent pneumonia, persistent diarrhoea, oral candidiasis | Adenovirus | 0.582 | IgG- 3.54 g/L IgA- <0.05 g/L IgM- <0.03 g/L |

CD3-11% (47.8) CD19-68.7% (298.7) CD56-18% (79.2) |

JAK3 | SCID |

| Pt. 122 | 7 months/female | Recurrent pneumonia, persistent diarrhoea, septicemia | Rhinovirus, Blood- Candida sp. | 0.952 | IgG- 16.55 g/L IgA- 0.29 g/L IgM- 1.12 g/L |

CD3-4.7% (12) CD19-0% CD56-91% (231) |

Not done | SCID |

| Pt. 123 | 6 months/male | Recurrent pneumonia, persistent diarrhoea | Nil | 0.780 | IgG- 3.06 g/L IgA- 0.26 g/L IgM- 0.30 g/L |

CD3-85% (665) CD19-3% (26) CD56-11% (87) |

ADA | SCID |

| Pt. 124 | 6 months/male | Recurrent pneumonia, persistent diarrhoea, cellulitis, hepatosplenomegaly, panniculitis | M. bovis | 0.370 | IgG- 0.19 g/L IgA- <0.01 g/L IgM- 0.16 g/L |

CD3-4.94% (22) CD19-84% (404) CD56-0.09% (3) |

Not done | SCID |

| Pt. 125 | 36 months/male | Recurrent pneumonia, persistent diarrhoea | Nil | 0.480 | IgG- 11.80 g/L | CD3-33.3% (156.5) CD19-33.4% (156.3) CD56- 28.3% (112) |

Not done | SCID |

| Pt. 126 | 7 months/female | Recurrent pneumonia, persistent diarrhoea, septicemia | Blood- Acinetobacter baumanni, Candida sp. | 1.090 | IgG- 9.80 g/L IgA- 0.17 g/L IgM- 0.43 g/L |

CD3-0.35% (4) CD19-82.7% (1048) CD56- 4.56% (58) |

Not done | SCID |

| Pt. 127 | 11 months/male | Recurrent pneumonia, persistent diarrhoea, otitis media | Ear pus- P. aeruginosa | 0.824 | IgG- 12.40 g/L | CD3-3.0% (26) CD19-84% (682) CD56- 3.56% (48) |

Not done | SCID |

| Pt. 128 | 4 months/female | Recurrent pneumonia, persistent diarrhoea, otitis media, cellulitis | BAL- Adenovirus | 0.160 | IgG- 7.30 g/L IgA- 0.34 g/L IgM- 0.92 g/L |

CD3-0% CD19-30% (75) CD56- 42% (103) |

Not done | SCID |

| Pt. 129 | 8 months/male | Recurrent pneumonia, persistent diarrhoea, otitis media, septicemia | Blood- S. aureus, P. aeruginosa | 0.340 | IgG- 3.30 g/L IgA- 0.24 g/L IgM- 0.17 g/L |

CD3-2.0% (6) CD19-93% (310) CD56- 4% (18) |

JAK3 | SCID |

| Pt. 130 | 22 months/male | Recurrent pneumonia, persistent diarrhoea, septicemia | Blood- Streptococcus pneumoniae | 0.357 | IgG- 18.80 g/L IgA- 1.62 g/L IgM- 0.85 g/L |

CD3-5% (18) CD19-27% (97) CD56- 72% (222) |

Not done | SCID |

| Pt. 131 | 60 months/female | Recurrent pneumonia, persistent diarrhoea, septicemia, microcephaly | Nil | 0.760 | IgG- 13.80g/L IgA- 0.34 g/L IgM- 1.20 g/L |

CD3-4.0% (24) CD19-92.0% (696) CD56- 3% (18) |

Not done | SCID |

| Pt. 132 | 4 months/male | Recurrent pneumonia, persistent diarrhoea | Nil | 1.378 | IgG- 9.60 g/L IgA- 0.22 g/L IgM- 0.55 g/L |

CD3-4.0% (44) CD19-91% (986) CD56- 5.3% (58) |

Not done | SCID |

| Pt. 133 | 30 months/male | Recurrent pneumonia, persistent diarrhoea, otitis media, septicemia | CMV | 0.357 | IgG- 10.70 g/L IgA- 0.30 g/L IgM- 0.79 g/L |

CD3-5.0% (17.5) CD19-12% (93) CD56- 34.6% (124) |

Not done | SCID |

| Pt. 134 | 8 months/male | Recurrent pneumonia, otitis media, septicemia | Nil | 3.485 | IgG- 6.80 g/L IgA- 0.31 g/L IgM- 0.43 g/L |

CD3-1.0% (6) CD19-82% (2830) CD56- 18% (654) |

Not done | SCID |

| Pt. 135 | 5 months/male | Recurrent pneumonia, persistent diarrhoea, septicemia | Candida sp. | 3.240 | IgG- 2.80 g/L IgA- 0.18 g/L IgM- 0.26 g/L |

CD3-12% (388) CD19-0% CD56- 86% (2786) |

Not done | SCID |

| Pt. 136 | 6 month/male | Two elder male sibling death at early infancy | Nil | 0.300 | N.A. | CD3-0.7% (1) CD19-97.6% (290) CD56-0.4% (1) |

IL2RG | SCID |

| Pt. 137 | 6 months/male | Recurrent pneumonia, septicemia, eczematoid rash | Candida sp. | 2.436 | IgG- 2.70 g/L IgA- 0.35 g/L IgM- 0.36 g/L IgE- 24,200 U/L |

CD3-66% (1610) CD19-26% (634) CD56-8% (195) CD3+45RO+ - 97.5% (elevated) |

CD3D | Omenn syndrome |

| Pt. 138 | 2 months/female | Recurrent pneumonia, cellulitis, OS, abscess | Candida sp. | 32.600 | IgG- <0.33 g/L IgA- <0.06 g/L IgM- <0.04 g/L |

CD3-87% (28,362) CD19-0% CD56-7.6% (2478) |

Not done | Omenn syndrome |

| Pt. 139 | 1 months/female | Cellulitis, rash | N.A | 1.230 | IgG- 9.40 g/L IgA- <0.25 g/L IgM- N.A |

CD3-1% (12) CD19-N.A. CD56-N.A. |

Not done | SCID |

| Pt. 140 | 36 months/male | Recurrent pneumonia, persistent diarrhoea | Clostridium difficle, CMV | 3.024 | IgG- 12.90 g/L IgA- 1.53 g/L IgM- 0.56 g/L |

CD3-56% (1680) CD19-1.4% (42) CD56-26% (780) |

RAG1 | Atypical SCID |

| Pt. 141 | 6 months/female | Recurrent pneumonia, septicemia | Candida sp., Staphylococcus sp. | 2.405 | IgG- <0.75 g/L IgA- 0.24 g/L IgM- N.A |

CD3-0.6% (14) CD19-62.4% (1504) CD56-22.9% (552) |

Not done | SCID |

| Pt. 142 | 8 months/male | Recurrent pneumonia, persistent diarrhoea, septicemia | candida | 2.075 | IgG- 0.09 g/L IgA- <0.26 g/L IgM- <0.16 g/L |

CD3-1% (21) CD19-93% (1934) CD56-0.2% (4) |

Not done | SCID |

| Pt. 143 | 8 months/male | Recurrent pneumonia | Nil | 2.650 | IgG- 7.62 g/L IgA- 0.25 g/L IgM- 0.64 g/L |

CD3-18.36% (488) CD19-5% (133) CD56- N.A. |

Not done | SCID |

| Pt. 144 | 7 months/female | Recurrent pneumonia, persistent diarrhoea, BCG site ulceration | Nil | 1.090 | IgG- 0.10 g/L IgA- 0.02 g/L IgM- N.A |

CD3- 1.1% (12) CD19- 0% CD56- 22% (231) |

Not done | SCID |

| Pt. 145 | 5 months/male | Recurrent pneumonia, | Nil | 0.060 | IgG- 1.08 g/L IgA- 0.10 g/L IgM- 0.14 g/L |

CD3-0.01% (1) CD19-NA (151) CD56- 62.33% (206) |

Not done | SCID |

| Pt. 146 | 7 months/male | Recurrent pneumonia, | Nil | 4.200 | N.A | CD3-18.31% (838) CD19-51.69% (2682) CD56- 15.9% (826) |

Not done | SCID |

| Pt. 147 | 9 months/female | Recurrent pneumonia, Septicemia, disseminated BCGosis | E. coli, M. bovis | 0.994 | IgG- 0.06 g/L IgA- 0.26 g/L IgM- 0.30 g/L |

CD3-1.53% (10) CD19-84.69% (692) CD56- 2.76% (23) |

Not done | SCID |

| Pt. 148 | 16 months/male | Recurrent pneumonia, Septicemia | Candida sp. | 1.316 | IgG- 12.20 g/L IgA- 1.08 g/L IgM- 6.54 g/L |

CD3-0.54% (2) CD19-0.64% (3) CD56- 10.93% (46) |

Not done | SCID |

| Pt. 149 | 5 months/male | Recurrent pneumonia, persistent diarrhea, BCG site ulceration | Nil | 1.5 | IgG- 0.02 g/L IgA- 0.37 g/L IgM- 0.21 g/L |

CD3- 0.1% (2) CD19- 0% CD56- 95% (1425) |

Not done | SCID |

| Pt. 150 | 7 months/male | Recurrent pneumonia, | BAL – M. tuberculosis, Pseudomonas sp. | 3.000 | IgG- <2.0 g/L IgA- 0.10 g/L IgM- 0.90 g/L |

CD3-0.20% (6) CD19-70% (2100) CD56- 36% (1080) |

CD3E | SCID |

| Pt. 151 | 6 months/male | Recurrent pneumonia, oral thrush | Enterococcal sepsis | 0.6 | IgG- 1.24 g/L IgA- <0.01 g/L IgM- <0.01 g/L |

CD3- 47.2% (283) CD19- 0.1% (1) CD56- 46% (276) |

RAG1 | SCID |

| Pt. 152 | 5 months/male | Recurrent pneumonia, persistent diarrhoea | Nil | 1.099 | IgG- <0.75 g/L IgA- <0.10 g/L IgM- 0.35 g/L |

CD3-0% CD19-93% (1015) CD56- 2% (23) |

IL2RG | SCID |

| Pt. 153 | 2 months/male | Recurrent pneumonia, septicemia | Candida sp. (blood) | 0.080 | IgG- 1.90 g/L IgA- <0.05 g/L IgM- <0.05 g/L |

CD3-10.4% (2.4) CD19-5.6 (1.29) CD56- 64% (14.84) |

ADA | SCID |

| Pt. 154 | 3 months/male | Acute fever, cough | Nil | 0.323 | IgG- <1.46 g/L IgA- <0.24 g/L IgM- 0.97 g/L |

CD3-26% (84) CD19-65% (202) CD56-40% (129) |

ADA | SCID |

| Pt. 155 | 7 months/male | Persistent diarrhoea | Nil | 2.538 | IgG-1.59 g/L IgA- <0.24 g/L IgM- <0.17 g/L |

CD3-0% (0) CD19-86% (2183) CD56%-11% (279) |

IL7R | SCID |

| Pt. 156 | 21 months/male | Meningoencephalitis, right chorioretinitis, left vitreal hemorrhage | CMV | 0.508 | N.A. | CD3-5% (25) CD19-12% (61) CD56-62% (315) |

PNP | SCID |

| Pt. 157 | 5 months/male | Pneumonia | Citrobacter sp. | 1.520 | IgG- <1.34 g/L IgA- <0.28 g/L IgM- 0.25 g/L |

CD3-0% (0) CD19-0% (0) CD56-96% (146) |

RAG1 | SCID |

| Pt. 158 | 24 months/male | Recurrent pneumonia, diarrhoea, meningoencephalitis | E. coli | 16.624 | N.A. | CD3-85% (14130) CD4- 7% (1164) CD8- 70% (11637) CD19-10% (1662) CD56- 4% (665) HLA-DR expression on B cells- 0% |

RFXANK | CID |

| Pt. 159 | 5 months/male | Pneumonia, diarrhoea, rash | S. epidermidis | 0.320 | N.A. | CD3-1% (1) CD19-32% (102) CD56-14% (45) |

ADA | SCID |

| Pt. 160 | 5 months, female | Pneumonia | P. jirovecii, H1N1 | 1.967 | N.A. | CD3-2% (39) CD19-0% (0) CD56-95% (1869) |

Not done | SCID |

| Pt. 161 | 3 months, female | Pneumonia, diarrhoea | Nil | 0.203 | N.A. | CD3-0% (0) CD19-0% (0) CD56- 82% (166) |

Not done | SCID |

| Pt. 162 | 12 months/male | Recurrent diarrhoea, left empyema | Nil | 1.958 | IgG- 15.7 g/L IgA- 3.94 g/L IgM- 2.13 g/L |

CD3-43% (842) CD4- 2% (39) CD8- 30% (387) CD19-15% (294) CD56-38% (744) |

Not done | SCID |

| Pt. 163 | 7 months, male | Pneumonia, global developmental delay | M. tuberculosis | 0.979 | NA | CD3-7% (69) CD19-86% (842) CD56-3% (29) |

Not done | SCID |

| Pt. 164 | 2 months, male | Scaly erythrodermic rash (OS) | Nil | 3.854 | IgG-1.89 g/L IgA-0.28 g/L IgM-2.08 g/L |

CD3-55% (2120) CD4- 33% (1272) CD8- 11% (424) CD4+ 45RA+ - 3% (decreased) CD19-18% (694) CD56-25% (964) |

Not done | Omenn syndrome |

| Pt. 165 | 12 months, male | Abscesses in lung, liver, oral thrush | Nil | 0.548 | IgG-5.63 g/L IgA- <0.70 g/L IgM- <1.07 g/L |

CD3-42% (230) CD19-18% (694) CD56-20% (110) |

Not done | SCID |

| Pt. 166 | 2 months, male | Recurrent pneumonia, rash | Acinetobacter sp. | 1.620 | N.A. | CD3-68% (1102) CD4- 12% (194) CD8- 36% (583) CD4+ 45RA+ - 0% CD19-21% (340) CD56-6% (97) |

Not done | Omenn syndrome |

| Pt. 167 | 10 months, male | Chronic fever, pneumonia, hepatomegaly, pancytopenia | Nil | 0.954 | IgG- <1.34 g/L IgA- <0.28 g/L IgM- <0.17 g/L |

CD3-24% (229) CD19-63% (601) CD56-7% (67) |

Not done | SCID |

| Pt.168 | 12 months, male | N.A. | N.A. | 3.080 | IgG- <0.29 g/L IgA- 0.64 g/L IgM- 0.34 g/L |

CD3- 4.5% (138) CD19- 71.3% (2197) CD56- 1.9% (60) |

IL2RG | SCID |

| Pt.169 | 60 months, male | NA | NA | 0.870 | IgG- <0.10 g/L IgA- <0.001 g/L IgM- <0.01 g/L |

CD3- 0.5% (6) CD19- 89.7% (1076) CD56- 7.8% (94) |

IL2RG | SCID |

| Pt.170 | 7 months, male | NA | NA | 0.330 | IgG- 0.06 g/L IgA- 0.001 g/L IgM- 0.002 g/L |

CD3- 7% (23) CD19- 0.3% (1) CD56- 80.9% (267) |

RAG1 | SCID |

| Pt.171 | 48 months, male | NA | NA | 1.160 | IgG-0.59 g/L IgA-0.005 g/L IgM-0.007 g/L |

CD3- 31.6% (367) CD19- 35.3% (410) CD56- 31.4% (364) |

RAG1 | SCID |

| Pt.172 | 12 months, female | NA | NA | 7.220 | IgG-2.36 g/L IgA-0.002 g/L IgM-0.01 g/L |

CD3- 0.3% (22) CD19- 0.7% (54) CD56- 56% (4044) |

RAG2 | SCID |

| Pt.173 | 48 months, male | Otitis media, recurrent pneumonia since early infancy | NA | 1.800 | IgG-1.16 g/L IgA-0.008 g/L IgM-0.006 g/L |

CD3- 9.4% (169) CD19- 58.3% (1049) CD56- 22.5% (406) |

DOCK2 | CID |

| Pt.174 | 4 months, female | Chronic diarrhoea, pneumonia, failure to thrive, absent thymus | E. coli, Cryptosporidium | 1.63 | IgG- 5.35 g/L IgA- 0.31 g/L IgM- 1.82 g/L |

CD3- 89.7% (1462) CD19- 1.2% (19) CD56- 4% (65) |

Not done | Possible SCID*** |

| Pt.175 | 30 months, male | Recurrent pneumonia, diarrhoea, failure to thrive | Nil | 0.35 | IgG-7.02 g/L IgA-1.31 g/L IgM- 0.82 g/L |

CD3- 56.3% (197) CD19- 0.8% (3) CD56- 39.4% (138) |

Not done | SCID |

| Pt.176 | 9 months, male | Chronic diarrhoea, pneumonia, failure to thrive | P. aeruginosa, Candida sp. | 0.60 | IgG- 0.99 g/L IgA-0.7 g/L IgM-0.4 g/L |

CD3- 35.8% (215) CD19- 6.7% (40) CD56- 47.8% (287) |

Not done | SCID |

| Pt.177 | 14 months, female | Recurrent pneumonia, diarrhoea, failure to thrive | Nil | 2.63 | IgG-1.46 g/L IgA- <0.25 g/L IgM- <0.18 g/L |

CD3- 74% (1947) CD4- 14% (368) CD8- 34% (895) CD19- 2% (53) CD56- 23% (605) |

Not done | CID |

| Pt.178 | 3 months, male | Recurrent pneumonia, fungal skin infection, 2 early sibling death | P. aeruginosa, Streptococcus sp. | 2.12 | IgG-2.52 g/L IgA- <0.25 g/L IgM- 1.12 g/L |

CD3- 57.3% (1215) CD4- 0.5% (11) CD8- 56.3% (1194) CD19- 38.2% (810) CD56- 1% (21) |

Not done | SCID |

| Pt.179 | 7 months, male | Pneumonia, scaly erythrodermic rash | Nil | 0.42 | IgG- 0.18 g/L IgA-0.52 g/L IgM-0.42 g/L |

CD3- 83.3% (350) CD19- 1% (4) CD56- 1% (4) |

Not done | Omenn syndrome |

| Pt.180 | 14 months, male | Recurrent pneumonia, eczematoid rash, failure to thrive | Cryptosporidium | 2.19 | IgG- 2.16 g/L IgA-1.21 g/L IgM-1.22 g/L |

CD3- 41% (897) CD4- 4% (88) CD8- 17% (372) CD19- 1% (22) CD56- 17% (372) |

Not done | CID |

| Pt.181 | 6 months, male | Chronic diarrhoea, failure to thrive, septicemia | E. coli, Candida sp. | 1.37 | IgG-9.52 g/L IgA-1.79 g/L IgM-0.26 g/L |

CD3- 87.1% (1194) CD4- 34% (466) CD8- 53.1% (727) CD19- 0.2% (3) CD56- 12% (165) |

Not done | SCID |

| Pt.182 | 3 months, male | Meningitis, pneumonia, oral thrush, early sibling death | P. aeruginosa | 3.55 | N.A. | CD3- 35% (1244) CD4- 10% (355) CD8- 15% (533) CD19- 0.1% (4) CD56- 56% (1990) |

Not done | SCID |

| Pt.183 | 16 months, male | Pneumonia, eczematoid rash, Varicella infection, early sibling death due to pneumonia | Acinetobacter sp., Pseudomonas sp. | 2.55 | N.A. | CD3- 46% (1174) CD4- 14% (357) CD8- 33% (842) CD19- 4% (102) CD56- 50% (1276) |

Not done | CID |

| Pt.184 | 3 months, female | Pneumonia, abdominal distension, diarrhoea, failure to thrive | Nil | 1.80 | IgG-1.63 g/ IgA- <0.06 g/L IgM- <0.16 g/L |

CD3- 35% (630) CD19- 0.8% (14) CD56- 63% (1134) |

Not done | SCID |

| Pt.185 | 3 months, male | Pneumonia, failure to thrive | M. tuberculosis | 0.50 | IgG-9.03 g/L IgA- 0.39 g/L IgM-2.23 g/L |

CD3- 45% (315) CD19- 50% (350) CD56- 1.4% (10) |

Not done | SCID |

| Pt.186 | 9 months, male | Persistent diarrhoea, pneumonia, left forearm abscess | Nil | 2.43 | IgG-4.0 g/L IgA-0.74 g/L IgM- 1.1 g/L |

CD3- 43.9% (1068) CD3+CD4+- 26% (631) CD3+CD8+- 14% (340) CD19- 54.9% (1335) CD56- 1% (24) |

Not done | Possible SCID*** |

| Pt.187 | 4 months, male | Developmental delay, pneumonia, diarrhoea, failure to thrive, 1 early sibling death | E. coli | 1.50 | IgG-2.95 g/L IgA-0.07 g/L IgM- 1.04 g/L |

CD3- 44.9% (674) CD19- 44.9% (674) CD56- 10% (150) |

Not done | Possible SCID*** |

| Pt.188 | 3 months, female | Otitis media, oral thrush, failure to thrive | Nil | 1.86 | IgG-2.95 g/L IgA-0.07 g/L IgM- 1.04 g/L |

CD3- 9% (167) CD19- 0.5% (9) CD56- 87.8% (1633) |

Not done | SCID |

| Pt.189 | 96 months, female | Recurrent pneumonia, ear discharge, failure to thrive | Nil | 1.21 | IgG-2.14 g/L IgA- 7.05 g/L IgM-1.54 g/L |

CD3- 39% (473) CD19- 16% (194) CD56- 41.2% (498) |

Not done | CID |

| Pt.190 | 24 months, female | Ear discharge, diarrhoea, scaly rash (Omenn phenotype) | Nil | 8.75 | N.A. | CD3- 80% (7003) CD4- 5% (438) CD8- 30% (2626) CD19- 2% (175) CD56- 14% (1226) |

Not done | CID |

| Pt.191 | 1 month, female | Septicemia, 3 early siblings died at early infancy | Nil | 2.89 | N.A. | CD3- 63.9% (1847) CD4- 55.9% (1616) CD8- 8% (231) CD19- 18% (520) CD56- 15% (433) |

Not done | SCID |

| Pt.192 | 6 months, male | Multiple hypodense lesions in liver and spleen, necrotic retroperitoneal lymph nodes | Nil | 0.01 | N.A. | CD- 0 CD19- 0 CD56- 0 |

Not done | SCID |

| Pt.193 | 7 months, male | Recurrent pneumonia, diarrhoea, early sibling death due to disseminated BCGosis | Acid-fast bacilli, Candida sp. (BAL) | 2.15 | N.A. | CD3- 0% CD19- 98.9% (2128) CD56- 0.3% (6) |

Not done | SCID |

| Pt.194 | 2.5 months, male | Diarrhoea, ear discharge, pneumonia, dermatitis, knee joint swelling, axilla abscess, 1 elder sibling expired due to SCID | Blood, pus: S. aureus (Methicillin sensitive) | 2.85 | N.A. | CD3- 57% (1624) CD4- 17% (484) CD8- 31% (883) CD19- 0.3% (9) CD56- 40% (1140) |

Not done | SCID |

| Pt.195 | NA, male | Pneumonia, otitis media, septicemia | Pseudomonas sp. | 1.51 | IgG-4.0 g/L IgA-0.52 g/L IgM-0.32 g/L |

CD3- 0.3% (5) CD19- 0 CD56- 4% (62) |

Not done | SCID |

| Pt.196 | 3 months, male | Pneumonia, oral thrush | Nil | 0.01 | N.A. | N.A. | ADA | SCID |

| Pt.197 | 3 months, male | Recurrent pneumonia, 1 early sibling death | Nil | 2.86 | N.A. | N.A. | IL2RG | SCID |

| Pt.198 | 2 months, female | Pneumonia, colitis | Nil | 4.40 | IgG-0.89 g/L IgA- <0.24 g/L IgM- <0.17 g/L |

CD3- 0.5% (22) CD19- 87.3% (3839) CD56- 2% (88) |

JAK3 | SCID |

| Pt.199 | 1.5 months, female | Pneumonia, oral thrush, 2 elder female siblings died at early infancy | Nil | 1.50 | N.A. | CD3- 0 CD19- 63.1% (947) CD56- 34.7% (521) |

Not done | SCID |

| Pt.200 | 8 months, male | Recurrent pneumonia, BCGosis | Nil | N.A. | N.A. | CD3- 0% CD19- 64% (443) CD56- 31% (214) |

IL7RA | SCID |

| Pt.201 | 8 months, female | Recurrent pneumonia, oral thrush, BCGosis | Nil | 0.55 | IgG- <0.06 g/L IgA- <0.24 g/L IgM- <0.17 g/L |

CD3- 0 CD19- 16.7% (92) CD56- 65.3% (359) |

Not done | SCID |

| Pt.202 | 7 months, female | Recurrent pneumonia, diarrhoea | CMV viremia, Candida sp. | 2.48 | IgG-0.97 g/L IgA-1.82 g/L |

CD3- 70.8% (1755) CD4- 2.6% (65) CD8- 59% (1463) CD19- 30.2% (748) CD56- 22.3% (553) |

Not done | SCID |

| Pt.203 | 24 months, male | Recurrent pneumonia, otitis media | S. aureus (Methicillin resistant) | 1.60 | IgG-1.61 g/L IgA-0.29 g/L IgM-0.29 g/L |

CD3- 22% (352) CD19- 58% (928) CD56- 13% (208) |

Not done | SCID |

| Pt.204 | 24 months, female | Chronic diarrhoea, pneumonia | Corona virus 229E, Alpha hemolytic streptococci (blood), esophageal candidiasis | 1.16 | IgG-1.14 g/L IgA-0.15 g/L IgM-0.27 g/L |

CD3- 23.4% (272) CD19- 9.1% (105) CD56- 42.3% (491) |

RAG1 | SCID |

| Pt.205 | 192 months, male | Recurrent pneumonia, varicella infection, madarosis, Hodgkin lymphoma | Epstein Barr viremia | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | RAG1 | Atypical SCID |

| Pt.206 | 5 months, male | Recurrent pneumonia, diarrhoea, elder male sibling died in early infancy, 4 maternal uncles expired < 6 months age | Adenovirus | N.A. | N.A. | NA; CD132 expression very low in monocytes (0.2%) compared to normal expression in controls | Not done | SCID |

| Pt.207 | 5 months, male | Pneumonia, diarrhoea, ear discharge, oral thrush, rash, early sibling death | VAPP in stool, Enterovirus, Klebsiella (BAL), CSF- Enterovirus, Mycoplasma | 0.39 | IgG- <1.46 g/L IgA- <0.28 g/L IgM- 0.17 g/L |

CD3- 28% (109) CD19- 1% (4) CD56- 68% (265) |

RAG2 | SCID |

| Pt.208 | 20 days, male | Pneumonia, diarrhoea, rash, renal abscess | Corona OC43, Rhinovirus | 0.25 | N.A. | CD3- 19% (47) CD19- 0 CD56- 24.4% (61) |

ADA | SCID |

| Pt.209 | 5 months, female | Chest wall abscess, recurrent pneumonia, oral thrush, diarrhoea | P. jirovecii, Rotavirus (stool), Mycoplasma (nasopharyngeal aspirate) | 0.97 | IgG- <1.46 g/L IgA- <0.17 g/L IgM- <0.28 g/L |

CD3- 1.3% (13) CD19- 0 CD56- 60% (581) |

RAG2 | SCID |

| Pt.210 | 6 months, male | Recurrent pneumonia, diarrhoea, scalp abscess, 1 male sibling death | CMV, Rhinovirus, Enterovirus | N.A. | IgG-0.26 g/L IgA-0.02 g/L IgM- 1.70 g/L |

N.A. | CIITA | CID |

| Pt.211 | 84 months, female | Recurrent diarrhoea, oral ulcer, pneumonia, colitis | Nil | 0.84 | IgG-4.97 g/L IgA- <0.67 g/L IgM-1.7 g/L |

CD3- 77% (649) CD19- 15.5% (130) CD56- 3% (28) HLA-DR expression in B cells- 0% |

RFX5 | CID |

| Pt.212 | 18 months, male | Recurrent pneumonia, diarrhoea, failure to thrive | VDPV, M. tuberculosis, Cryptosporidium, Enterobacter sp. (blood) | 3.75 | IgG- <1.41 g/L IgA- <0.24 g/L IgM-0.20 g/L |

CD3- 53.04% (1989) CD4- 22% (826) CD19- 4% (150) CD56- 42% (1576) |

Not done | CID |

| Pt.213 | 132 months, female | Recurrent pneumonia, diarrhoea, oral thrush, otitis media, meningitis | Hemophilus influenzae (CSF) | 2.94 | IgG-0.22 g/L IgA- <0.24 g/L IgM-0.44 g/L |

CD3- 34.7% (1022) CD4- 16.7% (490) CD8- 13.7% (405) CD19- 34% (1001) CD56- 2.2% (64) |

Not done | CID |

| Pt.214 | 4 months, male | Failure to thrive, recurrent pneumonia, diarrhoea | Nil | 1.22 | NA | NA | JAK3 | SCID |

| Pt.215 | 7 months, male | Otitis media, septicemia | Staphylococcus aureus | 6.23 | IgG- <0.3 g/L IgA- <0.05 g/L IgM- 0.11 g/L |

NA | IL2RG | SCID |

| Pt.216 | 8 months, male | Pneumonia, diarrhoea, rash | Nil | 5.02 | IgG- <0.11 g/L IgA- <0.05 g/L IgM- <0.11 g/L |

NA | IL2RG | SCID |

| Pt.217 | 1 month, male | Failure to thrive, persistent diarrhea, perianal rash | Nil | 0.97 | IgG- 0.42 g/L IgA- 0.06 g/L IgM- 0.59 g/L |

CD3- 4% (39) CD19- 39% (378) CD56- 54% (524) |

Not done | SCID |

| Pt.218 | 2 months, female | Recurrent episodes of pneumonia and diarrhoea, failure to thrive, doing well after HSCT | Nil | NA | NA | CD3- 3476 (Very low CD4 counts with CD4/CD8 reversal) CD19- 1765 CD56- 156 |

Probable MHC Class 2 defect | CID |

| Pt.219 | 1 month, female | Recurrent episodes of pneumonia and diarrhoea | Nil | NA | NA | NA | IL7R | SCID |

| Pt.220 | 1 month, male | Recurrent episodes of diarrhoea and failure to thrive | Nil | NA | NA | NA | IL2RG | SCID |

ESID, European Society for Immunodeficiencies; CMV, Cytomegalovirus; BCG, Bacillus Calmette-Guerin; BAL, Bronchoalveolar lavage; CSF, Cerebrospinal fluid; OS, Omenn syndrome; PJP, Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia; EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; VDPV, Vaccine-derived polio virus; VZV, Varicella zoster virus; AIHA, Autoimmune hemolytic anemia; VAPP, Vaccine-associated paralytic polio; CID, Combined Immune Deficiency.

Clinical details of patients 221-277 are previously reported (7).

***Possible SCID is categorized if patients did not fulfil the complete ESID definition, however, the treating team had a high index of suspicion based on clinical and immunological features.

Clinical profile of all patients was obtained along with family history and other demographic details. Clinical features included number of infections, type of infections, site of infections, organism involved, age of presentation, age of onset, presence of skin rash, BCG ulceration, history of administration of vaccines and complications, if any. Basic hematological, biochemistry, and immunological investigations including immunoglobulin profile and lymphocyte subsets were also recorded.

Analysis of lymphocyte subsets by flow cytometry had been carried out in most patients. Methodology for laboratory assay of lymphocyte subsets, naïve, memory T cells, HLA-DR expression, CD132 expression, CD127 expression, and lymphocyte proliferation assays at Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research (PGIMER), Chandigarh and National Institute of Immunohematology (NIIH), Mumbai have been previously described (11, 12). Other centers performed conventional lymphocyte subsets (CD3, CD19, CD4, CD8, CD56) by flow cytometry in private laboratories.

Adenosine deaminase (ADA) levels and percentage of deoxyadenosine nucleotides (%dAXP) from dried blood filter paper spot were assayed at Duke University, North Carolina for patients with ADA deficiency SCID who were diagnosed at PGIMER, Chandigarh.

Molecular Assays

Before the facility for in-house next-generation sequencing was made available in 2018, centre at PGIMER, Chandigarh had established academic collaborations with centers at Hong Kong (The University of Hong Kong), Japan (Kazusa DNA Research Institute, Kisarazu, Chiba; National Defense Medical College, Saitama), and USA (Duke University, North Carolina) for molecular work-up of patients. The centre at Hong Kong provided final molecular diagnosis for 12 patients (Pt. 8-10, Pt. 14-19, Pt. 21, Pt. 50-51) ( Table 1 ). Molecular diagnosis for 4 patients was established at Kazusa DNA Research Institute, Japan (Pt. 3–6). Thirty-four (34) patients (Pt. 59–90, pt. 119, pt. 127) with SCID were worked-up for molecular diagnosis using NGS at National Defense Medical College, Saitama and Tokyo Medical and Dental University, Tokyo, Japan (Kato T et al. manuscript in submission). Final molecular diagnosis of a patient with ADA defect (pt. 22) was also established at Duke University, North Carolina.

Sanger sequencing for IL2RG and RAG1/2 genes were initiated at PGIMER, Chandigarh (North India) in 2016. Sanger sequencing for patients with SCID at NIIH, Mumbai (West India) was previously described by Aluri et al. (7). Methodology for NGS at Christian Medical College, Vellore (South India) was described previously (13).

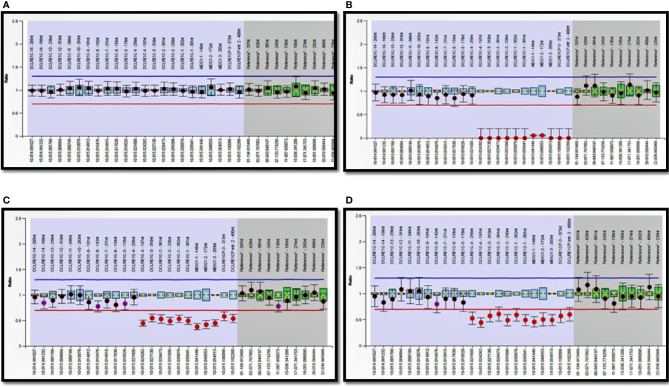

Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) at PGIMER, Chandigarh

Next-generation sequencing (Ion Torrent, Thermo Fisher Scientific India Pvt. Ltd.) for clinical care was started in July 2018 at the Advanced Pediatrics Centre, PGIMER, Chandigarh. A targeted PID gene panel comprising 44 genes was used that covered 6 genes for SCID—ADA, RAG1, RAG2, IL2RG, IL7RA, and LIG4. Preparation of DNA target amplification reaction using 2-primer pools, amplification of target, combination of target amplification reactions, ligating adaptors to the amplicons and their purification was carried out as per the manufacturer’s protocol using Ion AmpliSeq™ Library kit plus (Catalog numbers 4488990, A35121 A31133, A31136, A29751, 4479790). Amplified library was quantified using Qubit™ 2.0 fluorometer instrument. Dilution that results in a concentration of ~100pm was then determined. Template preparation on Ion One Touch™ Instrument, recovery, washing and enrichment of template-positive ISPs was done as per the manufacturer’s protocol using Ion 520™ and Ion 530™ Kit-OT2 (catalog number A27751). Ion S5™ sequencer instrument was then initialized. Annealing of primers to enriched ISPs and chip loading was carried out using Ion 520 and 530 Loading Reagents OT2 Kit. Sequencing run was initiated and Torrent Browser was used to review results. Raw data were analyzed on Ion Reporter software and on integrative genome viewer.

NGS using a targeted gene panel was also performed for some patients (n = 6) in private laboratories (Medgenome Labs Pvt. Ltd., India).

NGS at Other Centers

Other centers in India obtained molecular testing results from private laboratories (Medgenome Labs Pvt. Ltd., India; Strand Genomics Pvt. Ltd., India; Neuberg Anand Diagnostics Pvt. Ltd., India). Illumina platform was used for sequencing in private laboratories with coverage of >80X. Sanger sequencing was used to confirm variants obtained by NGS.

Multiplex Ligation Probe Amplification (MLPA) Assay for DCLERC1 Exon 1-3 Deletion at PGIMER, Chandigarh

SALSA MLPA probe-mix P368 DCLRE1C kit was used in this protocol. MLPA was performed according to the instructions provided by the manufacturer (MRC Holland). 50–100ng/µL of DNA was denatured in thermocycler and hybridized with 1.5 µL of probe-mix along with 1.5µL of MLPA buffer. Content was mixed and incubated for 1 min at 95°C followed by incubation at 60°C for 18 h. After hybridization, probes were ligated using a ligase mix at 54°C for 15 min. Ligase was inactivated at 98°C for 5 min. PCR was performed using PCR primers, polymerase, buffers and required amount of water. Following conditions were used for amplifications—95°C for 20 s, 65°C for 80 s, for 35 cycles, followed by a final extension for 20 min at 72°C. ABI 3100 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) was used for capillary electrophoresis. Later, 0.7µL of PCR reaction, 8.9µL of HI-DI formamide, and 0.4µL of DNA standard LIZ 600 provided by GeneScan were mixed and then denatured for 2 min at 95°C. The sample was then loaded and MLPA data were analyzed using a Coffalyser software.

Results

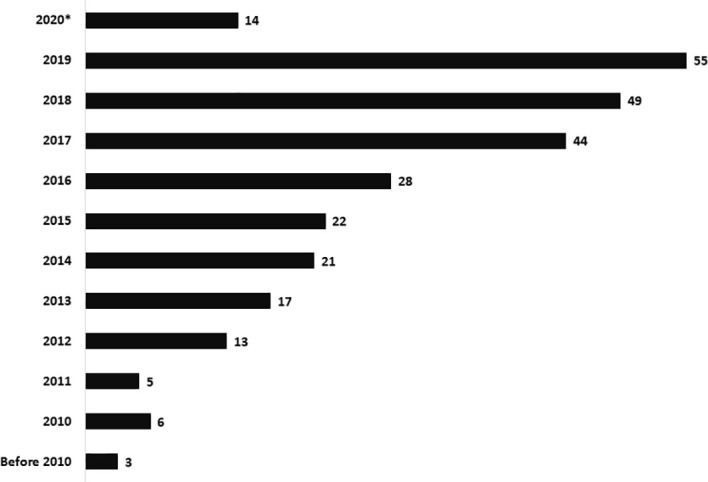

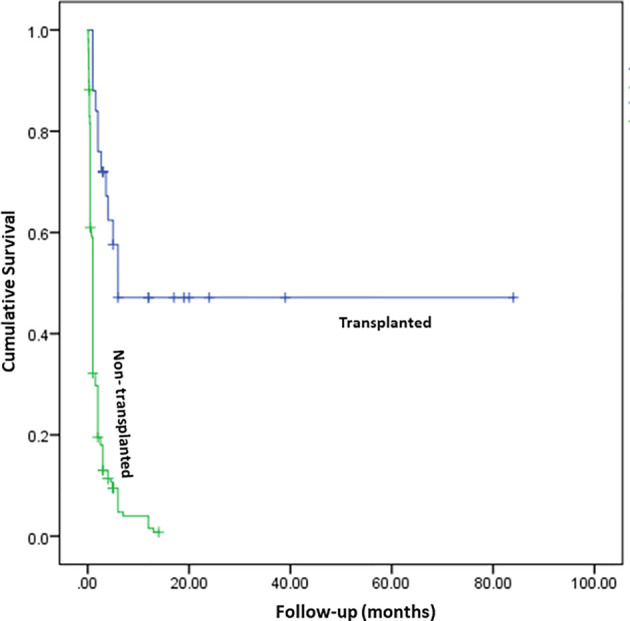

Current study included data of patients diagnosed and managed at centers in Northern, Southern, and Western parts of India. Amongst the 277 patients, 254 were categorized as SCID (208 – SCID; 17 – atypical SCID; 26 – OS; 3 – possible SCID) and 23 as CID ( Table 1 ). A steady increase in number of diagnosed cases was noted over last 10 years. The unit at PGIMER, Chandigarh (North India) diagnosed its first case of SCID in year 2001. Only 14 cases of SCID were identified until 2011 and an exponential rise in number of cases was noted after 2011 ( Figure 1 ). Rise in number of cases over years paralleled the expansion of available manpower resources and laboratory facilities for pediatric immunology at Advanced Pediatrics Centre, PGIMER (North India). Ninety (90) children (Pt. 1-90) with SCID have been diagnosed at PGIMER, Chandigarh until date. Fifty-eight (58) and 27 cases of SCID were enrolled from Bai Jerbai Wadia Children’s Hospital, Mumbai (West India) and Aster CMI, Bengaluru (South India), respectively.

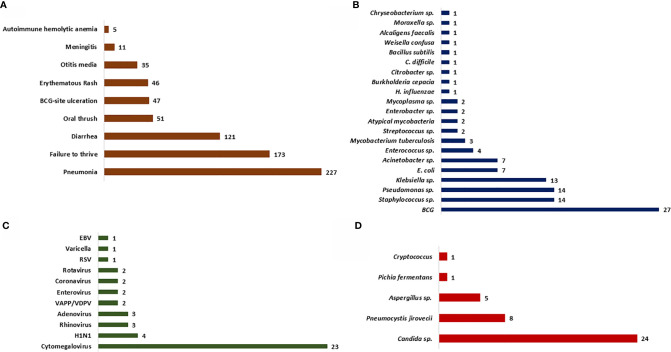

Figure 1.

Bar graph depicting the rise in number of cases diagnosed over last 10 years.

Male-female ratio was 196:81 ( Table 1 ). Median [inter-quartile range (IQR)] age of onset of clinical symptoms and diagnosis was 2.5 months (1, 5) and 5 months (3.5, 8), respectively. Consanguinity was noted in 78 families (28.2%), and was noticeably more in Southern region (32.3%) of our country compared to Northern (22.4%). Family history of early childhood deaths was noted in 120 children (43.3%). Median (IQR) age at diagnosis in children who had a positive family history was 4.5 months (3, 6) compared to 6 months (4, 9) in children who did not have a family history, p<0.05 (Mann-Whitney U test).

Opportunistic infections were the presenting manifestation in most patients. These included pneumonia (82%), diarrhoea (43.7%), oral thrush (18.4%), BCG site ulceration (17%), otitis media (12.6%), and meningitis (4%) ( Figures 2 , 3 ). Blood-culture proven septicemia was seen in 63 children (23%)—Candida sp. (16), Staphylococcus sp. (10), Escherichia coli (5), Acinetobacter sp. (5), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (8), Klebsiella pneumoniae (5), Enterococcus sp. (3), Enterobacter sp. (2), Streptococcus sp. (1), Pichia fermentans (1), Burkholderia cepacia (1), Chryseobacterium sp. (1), Bacillus subtilis (1), Citrobacter sp. (1), Moraxella sp. (1), Alcaligens faecalis (1), and Weisella confusa (1). Bacteria isolated from respiratory tract included Mycobacterium bovis (15), Klebsiella pneumoniae (5), P. aeruginosa (4), M. tuberculosis (3), atypical mycobacterium (1), E. coli (1), Staphylococcus aureus (1), and Acinetobacter sp. (1). Microbiology proven disseminated BCG infection was noted in 27 patients (9.7%). Apart from oral thrush and candidemia, other fungal infections noted were pneumonia due to Pneumocystis jirovecii (8), invasive aspergillosis (5), esophageal candidiasis (5), and pulmonary cryptcoccosis (1). Disseminated cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection was documented in 23 (8.3%) children and 6 amongst these had evidence of CMV retinitis. Intestinal lymphangiectasia due to CMV was noted on autopsy of a child with X-linked SCID (pt.8). Prolonged excretion of vaccine-derived poliovirus was documented in a child with leaky SCID at Mumbai (14, 15). Vaccine-associated paralytic poliovirus strain was also isolated in a child with RAG1 defect at Mumbai. He had presented with persistent diarrhea, developmental delay, and hypotonia.

Figure 2.

Bar graph depicting the clinical manifestations and microbiological profile. (A) Clinical manifestations noted at first clinical presentation; (B–D) Microbiological profile of the organisms isolated—bacteria (B), fungi (C), and viruses (D).

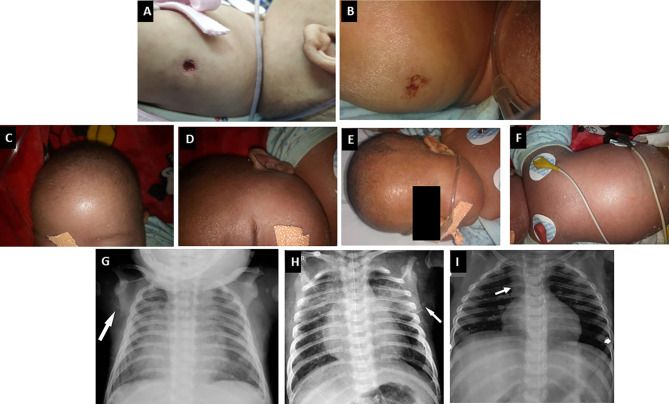

Figure 3.

Clinical manifestations of children with SCID. (A, B) BCG site ulceration and pus discharge (Pt. 46 and 34); (C–F) Features of Omenn syndrome such as generalized erythema, scaling, loss of hair, and eyebrows (Pt. 34); (G, H) Chest radiograph of a child with ADA SCID showing radiological abnormalities—scapular spur and flattening of lower border of scapula (Pt. 39); (I) Chest radiograph of a child with CORO1A defect showing normal thymus shadow (Pt. 49).

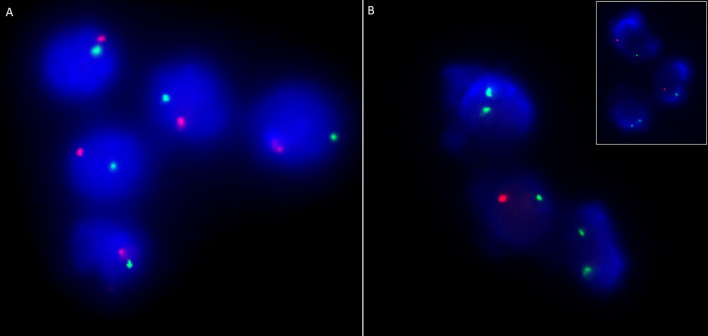

Clinical features of OS were seen in 33 children (11.9%)—classical OS in 11 and incomplete OS in 22 ( Figure 3 ). Molecular defects associated with OS include RAG1 (7), RAG2 (5), ADA (2), NHEJ1 (1), IL2RG (1), JAK3 (1), STIM1 (1), CD3D (1), DCLRE1C (1), and RFXANK (1). Two children with IL2RG defect had features of engraftment of transplacental-acquired maternal T cells that mimicked clinical features of OS ( Figure 4 ). Warm autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA) requiring immunosuppressive medications was observed in 5 children. While anemia responded to intravenous (IV) methylprednisolone pulses in 2 patients (RAG1 and NHEJ1 defect each), pt.42 with STK4 defect received IV rituximab (375 mg/m2 2 doses) for control of AIHA and she did not have further relapse of AIHA for next 1.5 years. Transfusion-associated graft-vs-host reaction was documented in 4 patients (2 X-linked SCID; 2 AR-SCID); all had development of rash and transaminitis following transfusion of non-irradiated blood products. Four (4) children had features of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH). Possible triggers for HLH included disseminated BCG (2) and H1N1 (1) infections. The child with SP110 defect did not have any identifiable trigger for HLH (pt.104). Hodgkin lymphoma and intra-cranial B cell lymphoma were noted in children with RAG1 and CORO1A defects, respectively.

Figure 4.

Chimerism analysis using dual colour FISH probes targeting centromeres of X (DXZ1; green) and Y (DYZ1, orange) chromosomes in a male child suspected with transplacental-acquired maternal T cell engraftment (Pt. 44). (A) Immunomagnetically sorted CD19 positive cells (B cells) showing XY pattern in all cells while; (B) Immunomagnetically sorted CD3 positive cells showing XX pattern in two out of three cells suggesting maternal T cell engraftment. Inset shows XX pattern in a lymphocyte and XY pattern in neutrophils.

Four of 18 children with ADA defect were noted to have radiographic abnormalities—scapular spurring and flattening of lower end of scapula ( Figure 3 ). Glomerular involvement was seen in 4 children—3 children with OS and 1 with atypical/leaky SCID. Nephrotic range proteinuria was noted in 3 patients and one child (pt.13) had features of mesangial sclerosis on autopsy. Another child (pt. 12) with OS had features of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis on autopsy. One child (pt.10) with IL7RA defect had features of distal renal tubular acidosis and nephrocalcinosis. This patient had deletion of exons 2–5 of CAPSL along with exon 4–8 deletion of IL7RA in chromosome 5p13.2. A child with PNP defect (pt.14) had evidence of horse-shoe kidney at autopsy (16).

Median (IQR) absolute lymphocyte count (ALC) observed was 1.33 × 109/L (0.6, 2.5). Normal ALC (≥ 3 × 109/L) was observed in 51 children (18.4%)—of these 26 had OS, 2 had transplacental-acquired maternal T-cell engraftment, and 23 had leaky SCID/combined immunodeficiency. Eosinophilia was observed in 37 children, and 26 amongst these had features of OS. One child (Pt. 105) with RAG1 defect had unexplained monocytosis (2.7-3.0 × 109/L) that resolved after HSCT. Results of immunoglobulin profile was available for 198 children. Fifty-five (55) children had normal or elevated levels of IgM levels—30 in SCID (14.2%), 7 in atypical SCID (41.2%), 8 in OS (30.8%), and 10 in CID (43.5%). We observed elevated levels of IgE in 12 children—8 had OS, 1 had eczema and STK4 defect, and 3 had unexplained eosinophilia.