Abstract

Background:

Despite evidence demonstrating the utility of using Person-Centred Outcome Measures within palliative care settings, implementing them into routine practice is challenging. Most research has described barriers to, without explaining the causal mechanisms underpinning, implementation. Implementation theories explain how, why, and in which contexts specific relationships between barriers/enablers might improve implementation effectiveness but have rarely been used in palliative care outcomes research.

Aim:

To use Normalisation Process Theory to understand and explain the causal mechanisms that underpin successful implementation of Person-Centred Outcome Measures within palliative care.

Design:

Exploratory qualitative study. Data collected through semi-structured interviews and analysed using a Framework approach.

Setting/participants:

63 healthcare professionals, across 11 specialist palliative care services, were purposefully sampled by role, experience, seniority, and settings (inpatient, outpatient/day therapy, home-based/community).

Results:

Seven main themes were developed, representing the causal mechanisms and relationships underpinning successful implementation of outcome measures into routine practice. Themes were: Subjectivity of measures; Frequency and version of Integrated Palliative care Outcome Scale; Training, education, and peer support; Building and sustaining community engagement; Electronic system readiness; The art of communication; Reinforcing use through demonstrating value.

Conclusions:

Relationships influencing implementation resided at individual and organisational levels. Addressing these factors is key to driving the implementation of outcome measures into routine practice so that those using palliative care services can benefit from the systematic identification, management, and measurement of their symptoms and concerns. We provide key questions that are essential for those implementing and using outcome measures to consider in order to facilitate the integration of outcome measures into routine palliative care practice.

Keywords: Outcome measures, implementation science, qualitative research, palliative care

What is already known about the topic?

Routine use of Person-Centred Outcome Measures improves health status and well-being in patients through enhancing quality of care and facilitating healthcare professionals in addressing symptoms and concerns that are most important to patients

Outcome measures are used inconsistently (if at all) in routine palliative care practice

Barriers to the implementation of outcome measures into routine practice include lack of knowledge, time, and feedback, and the absence of champions driving change

What this paper adds

Understanding of distinct implementation challenges for specific outcome measures and how these may impact quality and safety of care

A theoretically informed explanation of the causal mechanisms behind how individual and team interactions within different palliative care settings impact on the implementation of outcome measures

A key set of implementation questions for leaders and users to consider before and during the implementation of outcome measures into routine palliative care

Implications for practice, theory or policy

Accessible I.T. infrastructure for inputting, viewing, sharing, and extracting outcomes data is an essential but not sufficient condition for the implementation of outcome measures

‘Buy-in’ to implementation requires the involvement of all team members in the implementation process and the ‘normalisation’ of outcome measures into routine organisational practices

The use of appropriate theory can provide insight into complex implementation challenges where individuals and teams interact within organisations and wider systems of care

Introduction

Measuring outcomes is an integral part of evidence-based practice because it provides healthcare professionals with the information that they need to make decisions regarding diagnosis, prognosis, and the evaluation of clinical interventions.1,2 Person-centred outcome measures (herein referred to as ‘outcome measures’) are standardised and validated questionnaires that provide healthcare professionals with information of a person’s own perception of their well-being.3 Because many patients with advanced disease may have impaired cognition, or may be too unwell to complete outcome measures,4 they also include proxy-reported ratings which are reported by others.3

There is strong evidence for the utility of outcome measures within palliative care settings in: (a) improving communication between patients and clinicians; (b) identifying unrecognised needs and monitoring symptoms; (c) increasing the amount of clinical action taken; (d) improving outcomes through person-centred care; and (e) demonstrating the value of palliative care.3,5–9 Because they help to improve patient outcomes, their implementation into routine practice has been advocated by the European Association for Palliative Care Task Force on Outcome Measurement.10 Despite these recommendations, outcome measures are still used inconsistently (if at all) in palliative care settings. Common challenges to routine use include time constraints, lack of training/knowledge, tools being perceived as burdensome, negative attitudes, availability of champions to drive change, and fear of added work.1,8,11–14 This evidence, however, has not been translated into meaningful changes to clinical practice.

Implementation science – the systematic study of methods to promote the integration of evidence-based practices/interventions into routine practice15,16 – presents a potential solution by providing a menu of theories and determinant frameworks to facilitate the implementation of outcome measures.16 Determinant frameworks – such as the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research and Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services – have been used in palliative care research to describe the barriers/enablers to using outcome measures.1,13 However, these frameworks are limited to description and categorisation rather than delivering the ‘explanatory power’ that is crucial in specifying the causal mechanisms that underpin implementation.15 This makes it difficult to explain how and why implementation is likely to succeed or fail ‘thus restrain[s] opportunities to identify factors that predict the likelihood of implementation success and develop better strategies to achieve more successful implementation’.15 Consequently, there has been calls for theoretical development in outcome measure implementation within palliative care.8,10,16–18

Implementation theories go beyond description by providing comprehensive and generalisable explanations of individual, organisational, and structural mechanisms underpinning implementation, including how, why and in which contexts specific relationships between barriers/enablers might improve implementation effectiveness.15 They offer an opportunity to ‘move the field beyond simply identifying barriers and enablers of [outcome measure] implementation’ by proactively specifying ‘practical steps in translating research evidence into practice’.16

Whilst implementation theories have proved useful in implementing outcome measures in other fields,16 they have not been used in palliative care outcomes research. In this study, our a priori awareness of implementation as a contextualised, dynamic process contingent on achieving alignment at multiple social levels, led us to select Normalisation Process Theory as the theoretical framework offering the greatest potential to provide insight into the implementation of outcome measures.19,20 Normalisation Process Theory consists of four interconnecting constructs that describes the ‘work’ that individuals and organisations do in ‘normalising’ outcome measures (i.e. such deep embedment into everyday routines that they become invisible, see Table 1)21,22 and has been used to good effect in understanding and facilitating implementation work in a variety of settings.20 This study contributes to the literature through using Normalisation Process Theory to understand and explain the causal mechanisms underpinning the implementation of outcome measures into routine palliative care practice, and by proposing theoretically informed strategies to address challenges.

Table 1.

A description of the different Normalisation Process Theory constructs that underpin the implementation of person-centred outcome measures into routine practice. Derived from May (2013).22

| Normalisation Process Theory construct | Description |

|---|---|

| Coherence | Sense making work: How individuals and groups understand what outcome measures are and how/when to use them |

| Cognitive participation | Relational work: What people do to engage in using outcome measures in order to legitimise, and build a community around, their use |

| Collective action | Operational work: The ways in which people – individually and collectively – work to implement outcome measures into routine practice |

| Reflexive monitoring | Appraisal work: How people appraise and assess the value of outcome measures after using them |

Methods

Design

An exploratory design grounded in an interpretive paradigm.23 Thus, we sought to explore the mechanisms underpinning successful implementation, whilst appreciating that the knowledge developed was subjective and co-constructed between researchers and participants within particular socio-cultural contexts.

Participants and setting

This was a multi-site project conducted with 11 services delivering specialist palliative care in Yorkshire, England. Participants were recruited using a purposive maximum variation sampling technique24 to reflect variations in age, experience, role, and settings (inpatient, outpatient/day therapy, home-based/community). Participants were approached via email and provided with a participant information sheet. Written informed consent was obtained. Recruitment and data collection took place between May-Dec 2019.

Data collection

Single, face-to-face semi-structured interviews were conducted by one of three researchers with prior interviewing experience [AB (male, research fellow), MS (female, research nurse), MM (female, PhD candidate)] within participants’ workplaces. The interview guide (supplementary file 1) was developed through a literature search seeking the most common challenges regarding the implementation of outcome measures in healthcare settings. This included questions on their collection, transfer, and feedback, and how these issues may be addressed to aid implementation. Data collection continued until the research team were confident that data saturation25 had been achieved. Interviews were audio recorded, anonymised, and transcribed verbatim.

Analysis

Interview data were analysed deductively using a thematic Framework approach26,27 whereby data was reviewed, and themes were developed, in correspondence to the different components of Normalisation Process Theory. The Framework approach was adopted because it allows for iteration between raw data and developing findings to preserve the context of participants’ experiences26 but has a greater emphasis than thematic analysis on making the process of data analysis transparent.27,28 Analysis was conducted in NVivo (version 12) and entailed seven, interconnected steps: (1) transcription; (2) familiarisation; (3) coding; (4) developing an analytic framework; (5) indexing; (6) charting; and (7) interpreting the data. Whilst themes are presented under the different constructs of Normalisation Process Theory, the boundaries between these were porous, meaning that some constructs crossed over and interacted with one another.

Quality

A relativist approach to judging quality29 was adopted. This entailed using lists of criteria on what constitutes high quality qualitative research30,31 as a starting point, and then selecting criteria that was appropriate for the context, purposes, and methodology of this study. A list of selected criteria and how these were fulfilled can be seen in Table 2.

Table 2.

List of quality criteria selected and how it was fulfilled in this study.

| Quality criteria | How it was fulfilled? |

|---|---|

| Worthy topic | Timely study of a topic that is relevant and important within the field of palliative care |

| Substantive contribution | First study to use implementation theory (Normalisation Process Theory) to understand and explain the causal mechanisms underpinning successful implementation of outcome measures into practice and propose practical recommendations to solve challenges |

| Rich rigor | A multi-site study (n=11) conducting 63 semi-structured interviews with participants who were reflective of the various ages, roles, experiences, and settings of the palliative care workforce |

| Sincerity | Transparency of methods used and all members of the research team acting as ‘critical friends’ during analysis to offer alternative explanations and interpretations of findings and development of themes |

| Credibility | A wealth of interview data that allowed for thick description and concrete detail that shows the reader the processes underpinning implementation of outcome measures into practice |

| Resonance | Thick description of findings and a wide sample allows readers to make generalisations based on transferability and resonance with personal experiences |

| Meaningful coherence | Uses methodology and methods that are appropriate to the aims of this study, alongside connecting theory (Normalisation Process Theory) to the development and interpretation of findings |

Ethical approval

Approved by Hull York Medical School Ethical Committee [19 15, 26/03/2019].

Results

A total of 63 participants were recruited (see Table 3). Interviews lasted on average 37 minutes.

Table 3.

Participant characteristics.

| Participant characteristics (n = 63) | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| 25–34 | 4 |

| 35–44 | 13 |

| 45–55 | 31 |

| 55+ | 15 |

| Gender | |

| Female | 59 |

| Male | 4 |

| Professional background | |

| Nurse | 29 |

| Doctor/consultant | 16 |

| Allied health professional | 8 |

| Healthcare assistant | 4 |

| Chief executive | 2 |

| I.T. | 2 |

| Other | 2 |

| Setting | |

| Inpatient | 27 |

| Across settings | 16 |

| Home-based/Community | 15 |

| Outpatient/Day therapy | 5 |

| Experience in palliative care (years) | |

| 0–5 | 16 |

| 6–10 | 9 |

| 11–15 | 14 |

| 16–20 | 9 |

| 21–25 | 7 |

| 25+ | 8 |

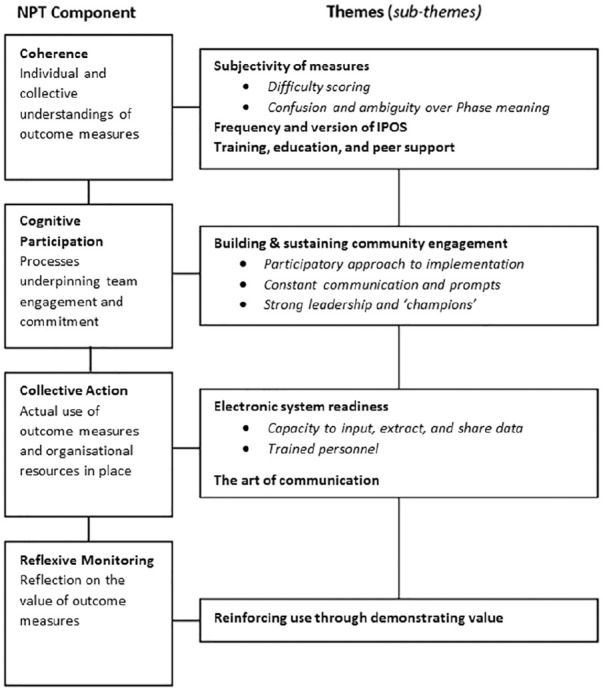

Seven themes (and seven sub-themes) encompassed within different, interconnecting constructs of Normalisa-tion Process Theory were identified as important processes in the implementation of outcome measures (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Main themes and sub-themes in relation to Normalisation Process Theory constructs.

Coherence

Three themes represent how individual and collective understandings of outcome measures impacted imple-mentation.

Theme 1: Subjectivity of measures

Sub-theme 1: Difficulty scoring

Many participants commented on how they perceived outcome measures to be inherently subjective which made confidently and consistently scoring patients difficult:

With the IPOS, I think it can be so subjective. Nursing staff may fill them in, or doctors may fill the IPOS in, or doctors give the Karnofsky score and then we might look at it and think, ‘ah hang on a minute’, and even within our team, therapists, we can argue against somebody’s Karnofsky. So although they’re validated tools, they still are subjective. [physiotherapist, inpatient]

Participants also found scoring psychosocial items on the Integrated Palliative care Outcome Scale difficult. The ‘at peace’ item was perceived as especially difficult to score because participants felt as though staff and patients found it hard to understand what was meant by this question:

From the staff to patient perspective, it’s more of the psychosocial side can be quite difficult for the patient to answer. There’s the lack of understanding in the one ‘are you at peace?’ It’s always the peace one that gets everybody, so it’s more of the patient’s understanding on completion of some of the questions. [nurse, inpatient unit]

Subjectivities over scoring interrupted implementation because instead of measures becoming an ‘invisible’ process completed with little thought, participants spent time deliberating over, as opposed to efficiently using, the measures.

Sub-theme 2: Confusion and ambiguity over Phase of Illness meaning

The meaning of the Palliative Phase of Illness measure caused many participants confusion. This was because the meanings of terms within this measure were different within palliative care compared to other medical settings:

I’ve only been working for 10 months or so in palliative medicine and I think it was tricky to begin with in terms of categorising patients, because obviously the words used, like stable, unstable and deteriorating have very different meanings in a clinical sphere compared to how they are used in the Phase of Illness. I remember when I worked in the hospital team in [location], and often we would write ‘Phase of Illness is stable’ on patients who were medically quite unstable and that often created quite a lot of confusion. [doctor, inpatient]

This was problematic to successful implementation because it meant that whilst this measure was being used throughout practice, it was often being used incorrectly.

Theme 2: Frequency and version of Integrated Palliative care Outcome Scale

Some participants reported that their ability to collect full Integrated Palliative care Outcome Scale (IPOS) data was thwarted by poor understandings of the frequency through which to use it. These misunderstandings led to excessive and unnecessary assessment that overburdened already unwell and fatigued patients, causing them to disengage from completing measures:

it was absolutely counterproductive, they were like ‘I’m sick of this’ . . . it does depend how unwell the patient is when they come in, they might not be conscious enough, or they might be too tired to be engaged in what could potentially be quite a long conversation . . . some patients are like ‘ooh I can’t be bothered, I don’t want to know, not this again’. We absolutely got that when we were doing them routinely, twice a week. [hospice educator, inpatient]

Misunderstandings of which version of IPOS to use was also problematic. Use of patient reported IPOS when the staff version might have been better meant that some patients were asked to continuously reflect on symptoms and concerns that were not improving, making them feel emotionally distressed:

The other challenge is – I’m going to actually relate this personally – my [relative] was a patient here within the Inpatient Centre. [Name] actually died here and could not cope with the IPOS forms at all. [Name] found them terrifying. For some reason it used to push them into an emotional block and [Name] felt tested. [Name] just found it wearing to keep doing it every day and to see that [Name] had a form coming towards him/her every day and he/she found that really hard, and I think if that’s happened to my [relative] that would have happened to other people. [nurse, outpatient and community]

Whilst this theme highlights challenges to implementing IPOS, it also raises concerns about how poor knowledge of outcome measures may lead to them being used in ways that compromise the quality and safety of care delivered to patients.

Theme 3: Training, education, and peer support

In addressing subjectivity of measures, participants spoke about the importance of training and education. This was so that they clearly understood what the measures were, their value, and how to collect data in clinically meaningful ways:

I don’t feel like I’ve had any training. . . I think if you’ve got no onus of what happens to it then you’re not really that bothered about making sure it’s as accurate as it can be and that we’re recording correctly . . . I think that in terms of improving that doubt, or getting rid of that doubt, educating people as to what they are, why they’re used, the benefits of them, what happens to them once you’ve collated them, and what they mean on a wider scale rather than just an individual basis. [doctor, inpatient]

Participants also valued peer support in which more experienced team members shared their skills and knowledge of outcome measures to facilitate their confident and consistent use by others:

I think we’ve all sort of, not struggled with [Palliative Phase of Illness], but it’s not always clear cut. If we’re not sure, we tend to get a bit of guidance from the consultant or we’ll just discuss it as a team . . . we’ve supported each other, which I think is important in any change, isn’t it? I think any change in any sort of job. [nurse, community]

Cognitive participation

One theme, comprised of three sub-themes, represented the processes that underpinned team engagement and commitment to using outcome measures in everyday practice.

Theme 4: Building and sustaining community engagement

Sub-theme 1: Participatory approach to implementation

If teams were to embrace change, it was crucial that implementation came from the bottom up, allowing those who used outcome measures the agency to shape how they were being implemented:

the buy-in shouldn’t be top down, you need to target the people that are doing it. I think that’s the problem with a lot of things, it’s like the top are telling us to do this but actually if you can get the people actually doing it to really understand and believe in what they’re doing then it’ll happen. [specialist doctor, inpatient]

This linked to participants’ coherence of measures because involvement in implementation helped them to understand how using outcome measures formed a legitimate part of their role. It also allowed them to feel a sense of responsibility and ownership by feeling a valid part of something that was meaningful to patient care:

I’ve tried to engage everybody in the process . . . and that has helped because they see it as their role and their project now . . . they’re more encouraged as a result because they have a responsibility . . . it’s about the involvement of the team. [consultant, community]

Sub-theme 2: Constant communication and prompts

Participants spoke about the importance of constantly communicating with outcome measures through using them to drive discussions and decisions regarding patient care. This was so that the measures were continuously in view and people saw how they connected to their roles daily:

I think being discussed all of the time [is key to outcome measures being embedded in practice]. Constantly saying ‘what’s the Karnofsky?’, ‘what’s the Phase?’, ‘what’s their Barthel?’ at every handover. . . and so we get into the habit of talking about it all of the time, so we talk about it daily but then we have a wider discussion at the ward rounds twice a week. [nurse, inpatient]

Over time, this helped to normalise their consistent collection and use until they became so ingrained that it was something that participants did not need to think about:

[within the organisation] they [outcome measures] were just fully integrated. . . it wasn’t even a question of whether or not to use them. It’s part of the process of what we do. It’s as integrated in what we do here as writing in medical notes. So I came in and I just picked up and got on with it. That was quite easy for me I have to be honest. [consultant, inpatient and community]

Sub-theme 3: Strong leadership and ‘champions’

Participants perceived that leaders were important in introducing and driving the use of outcome measures. These people were passionate and experienced in using these measures, and were integral in ensuring that the measures were understood and used in everyday discussions:

We’ve got a IPOS champion and their role is to chivvy everybody else and tell a little bit more information to everybody else to get the information collected and support new people when they come and so I think that’s a good role to have . . . You need that drive behind you because that’s somebody who’s really enthusiastic about it, who really believes in it and so she’ll talk to everybody really enthusiastically, getting them all on board. [nurse, inpatient]

Collective action

Two themes represent the ways in which participants’ use of outcome measures, and the resources and skill-sets already in place within organisations, impacted the implementation process.

Theme 5: Electronic system readiness

Three sub-themes demonstrate how having appropriate electronic systems in place was a linchpin to implementation. Electronic system readiness directly connected to how participants appraised the value of outcome measures (reflexive monitoring) and, in turn, their coherence of why they were using them. This was because efficient electronic systems were key to feeding back outcomes data to staff who collected them. Where this was possible, healthcare professionals were more likely to understand the clinical utility of outcome measures, thus appraise them as useful tools within clinical practice.

Sub-theme 1: Capacity to input, extract, and share data

Having an electronic system with the capability of inputting, viewing, sharing, and extracting data was ‘worth its weight in gold’ [nurse consultant, community]. This was because it helped to legitimise the use of outcome measures by allowing staff to use information easily and effectively:

we go into our assessment and click on specialist and you’ve got your scoring from doing your [IPOS] scoring on that day on your symptom, and you can see the previous scores. So you can see the pain, so if you’ve not met the patient before and it’s a 4 and you’ve gone in and the patient’s a lot better and it’s more of a 2, you can see the graph going down, so it links really well to the previous visits and it always reads excellent . . . I think SystmOne is fantastic, they used to see our essays in our assessments but now they can see the template and go to the plan that’s been highlighted from the problems and the issues that patients have and I think it’s a lot clearer for everybody, so I think it’s been great, definitely. [nurse, community]

In organisations where this was not the case, the implementation of outcome measures was severely disrupted, and in extreme instances, abandoned. This was because many participants questioned the value of, and time that it took to collect, data if this information sat dormant in electronic systems without being used for patient benefit:

because of the I.T. systems, we don’t have anything to pull it off that makes it meaningful, we did use IPOS in the day therapy a while ago which was helpful but the holding block was we didn’t have anything to pull it off I.T.-wise . . . so we put a hold on that until we had something useful I.T.-wise to pull it off to make it meaningful . . . it’s always the I.T. that holds us back. . .. otherwise it’s just data that’s sat there that’s not reaching its full potential, so that’s where people get annoyed because they’re asked to do stuff and then they can’t see the completeness of it, the value of it, so the more you can demonstrate that and embed what you want to do. [lead nurse, community]

Sub-theme 2: Trained personnel

Having people within organisations that had the skills and knowledge to tailor electronic systems to local needs, resources, and structures, alongside supporting the workforce’s effective use of these systems, was important to implementation:

having somebody with a good knowledge of SystmOne I think is the main thing [that was a helpful source of support] . . . I know when I get stuck with something I’ll go down and speak to our senior admin person and say ‘I’m having a bit of trouble here’, and she will put together the whole thing to do with stats and she did these brilliant set of stats that we have to do, she just did it and it cut down the time that I had to spend looking for things. So she’s got a really good knowledge . . . So I think we need the admin support. Somebody who’s got a good working knowledge of SystmOne but also of how to pull off the particulars of the Karnofsky. [lead nurse, inpatient]

Theme 6: The art of communication

Participants spoke about how the communication skills required to effectively collect IPOS data were akin to an art form in which patients should be made to feel empowered and listened to:

There’s an art to it. . . I think it’s just about being able to have that communication with somebody. . . I think the worst thing is just to not even make that person feel like that they’re a person and that they are just a tick-box exercise, ‘What’s your name? What’s your address? Have you got any medical problems? . . . you have to make them feel that they’re important, that we’re listening to them, that we’re there for them, and not just getting information [nurse, community]

This art entailed being able to ‘integrate it into your own assessment in a way that’s natural’ [consultant, community] and adequately explain what the measures were so that they were not presented to patients as a futile, tick-box questionnaire:

explaining the reason for it [the IPOS] is important because I think a lot of times people think ‘oh god, another survey’ and we have to say ‘well not really a survey, this is about your personal care on a week to week basis and it’s really important that we have an understanding of how you’re feeling’ so most of the time that works . . . I think the way you kind of sell it to them, if you like, will determine whether they’re going to fill it out or not. [healthcare assistant, inpatient]

However, many participants recognised that because of the intimate and unpredictable nature of the psychosocial and spiritual questions included in IPOS, that collecting full data was sometimes thwarted because it led to ‘avoidance tactic[s] from staff’ [lead nurse, community]:

it’s easier to talk about physical symptoms than emotional pain and distress or concerns for the future . . . it’s kind of natural human fears, it’s like opening up a can of worms, isn’t it? . . . sometimes we avoid it and we shouldn’t . . . some of its blocking by the patients, some of it’s probably blocking by us as professionals, there’s a bit of both that goes on, and so some of those questions on the second page of it are harder really to necessarily address or quantify. [lead nurse, community]

Reflexive monitoring

One theme captures the ways in which participants appraised the value of using outcome measures and how this affected implementation.

Theme 7: Reinforcing use through demonstrating value

Crucial to implementation was that the use of outcome measure was reinforced by providing those who collected data with real-life feedback of how they were being used to improve patient care and outcomes:

If people can see how it’s had an impact on the service, or patients, then people will always look keener to get involved in kind of any audit or work using the [outcome] scores . . . I think its feedback isn’t it: ‘this is what we did with it, and this is what we changed as a result of that, and that kind of always tends to motivate continued involvement in that . . . I think it’s [positive feedback] really powerful . . . You can’t get enough of that for frontline staff. [lead nurse, inpatient]

Without feedback on their clinical utility, measures were viewed as a pointless exercise. This undermined staff buy-in required for successful implementation because it led to ambivalence and loss of motivation in accurately collecting outcomes data:

I don’t think we ever knew what the information was going towards, so I don’t think we ever got feedback on it. So you’d do it, and it would be discussed at MDT [multi-disciplinary team meeting], but then it never went much further from what I remember . . . you think it’s a bit of a waste of time don’t you because you’re collecting information that nobody is doing anything with . . . So obviously it has an effect on your morale, but we do it, I’m not saying we don’t do it, but you do kind of think sometimes ‘oh what are we doing this for?’ Because it’s not actually telling us anything is it, or it doesn’t appear to be, but they might be telling somebody somewhere something that I’m just not aware of. . . you would hope that perhaps we would get more feedback on it or more information on it. [nurse, outpatient]

Discussion

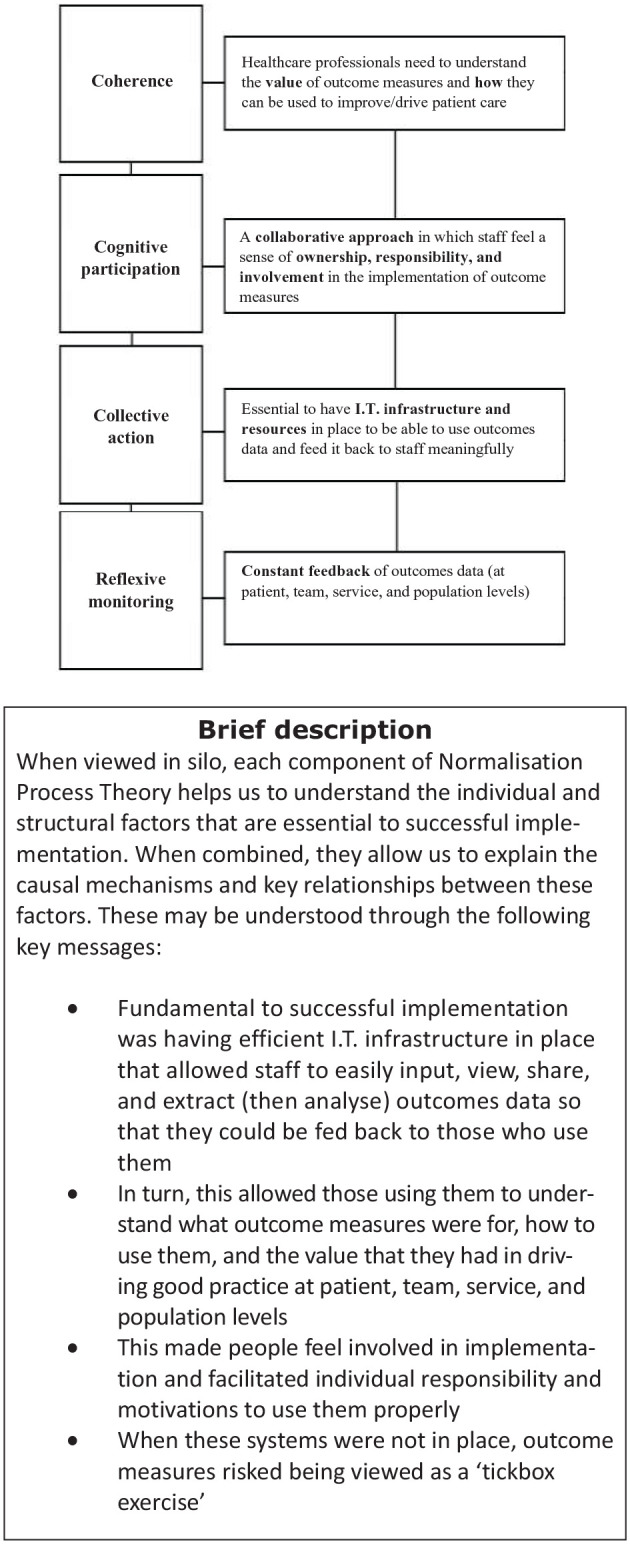

The main findings of this study may be understood through the constructs of Normalisation Process Theory. For coherence, it was important that those using outcome measures understood their value/how to use them appropriately and were provided with up-to-date training within their organisation. For cognitive participation, it was key that organisations built practices around outcome measures through adopting a participatory approach to implementation and having strong leaders/champions driving their integration into practice. Within collective action, it was key that there was efficient electronic infrastructure in place to operationalise outcomes and that healthcare professionals were able to communicate effectively using the measures with patients. Finally, within reflexive monitoring, it was crucial that those using the measures were provided with regular, meaningful feedback of data. These findings corroborate others that have reported similar challenges to implementing outcome measures in routine palliative care practice across Europe.1,8,11–14,17,32,33

What this study adds

This study contributes to theoretical development in this area by going beyond descriptive lists of barriers/challenges/enablers to implementation by drawing on Normalisation Process Theory to explain the causal mechanisms/relationships through which individual and structural challenges impact implementation (see Figure 2) and proposing theoretically-informed questions to address these challenges (see Table 4). Through demonstrating the value of Normalisation Process Theory as a robust theory for explaining the implementation of outcome measures in palliative care, this study also adds knowledge on implementation, acting on recent calls to ‘advance our collective understanding of how, why, and in what circumstances [implementation science] frameworks and implementation strategies [may] produce successful implementation’.16

Figure 2.

A summary explanation of the key relationships and causal mechanisms between the different Normalisation Process Theory constructs in the successful implementation of outcome measures into routine practice.

Note. The bold outline of collective action represents how this component is a central part of successful implementation of outcome measures.

Table 4.

Questions to consider when implementing outcome measures into routine practice.

| Level of action | Who should take action? | Questions to consider |

|---|---|---|

| Those leading implementation of outcome measures | Services managers; Chief executives; Outcome ‘champions’; Team leaders | Is there up-to-date and regular training/education in place for new and existing staff using outcome measures? |

| How will you include your team in the implementation of outcome measures? | ||

| Do you have electronic systems and support in place that allows staff to easily input, view, share, and extract outcomes data? | ||

| Have you considered how to feedback outcomes information to staff? | ||

| Have you planned on how to integrate the use of outcome measures into everyday clinical practice and team working (e.g. at multi-disciplinary team meetings, ward rounds, handovers, etc.)? | ||

| Can you identify staff members within your service who would be an appropriate outcomes champion? | ||

| Those using outcome measures | Nurses; Doctors; Allied healthcare professionals; Healthcare assistants | Within the setting that you work (inpatient, outpatient/day therapy, home-based/community), do you: |

| Understand which outcome measures to use, when to use them, and why you are using them? | ||

| Know which version of IPOS to use and when to collect it? | ||

| Know how to input, view, and extract outcomes information into (and out of) your service’s electronic system? | ||

| Understand how to clinically act on/respond to information collected through outcome measures? | ||

| Know where to go for additional help and advice on how to use outcome measures? |

Our data also presents novel contributions regarding the measure-specific challenges that healthcare professionals experience when using outcome measures, thus challenging a recent systematic review that argued ‘challenges in implementing [outcome measures] are not exclusive to the characteristic of the chosen measure’.1 Measure-specific challenges included confusion and ambiguity with regards to using Palliative Phase of Illness, and the art of communication required to effectively collect IPOS information. Furthermore, we also demonstrated how misunderstandings of which IPOS version to use and when disrupted implementation and raised concerns about the ways in which excessive person-centred assessments may compromise the quality and safety of care for patients. These issues need to be considered when planning for safe implementation of outcome measures into routine practice.

Implications for research and clinical practice

Through interpreting the findings of this study, we have proposed a set of questions – based on Normalisation Process Theory – that professionals who are leading rollout and using outcome measures should consider before and during implementation (Table 4). Critical application of these questions may potentially be transferable to healthcare settings outside of palliative care that are seeking to implement outcome measures into routine practice.

Strengths and limitations

A strength of this study is that it was a multi-site project conducted across an entire geographical region. Purposive sampling was used to recruit a diverse range of participants that were broadly representative of the palliative care workforce and settings in which specialist palliative care is delivered. This may allow naturalistic generalisations34 to be made for healthcare professionals using outcome measures within a palliative care context. That is, the findings of this study are likely to resonate with the personal experiences of staff using outcome measures within palliative care. Potential limitations of this study are that it relied on one-off interviews that may not have been able to capture how the processes of implementing outcome measures identified in this study may have changed over time. We also did not explore patients’ perspectives regarding how the implementation of outcome measures impacted their experiences of palliative care. Finally, we found that some concepts included within Normalisation Process Theory overlapped, making these more difficult to use.

Future directions

This study highlights the mechanisms underpinning the successful implementation of outcome measures into routine palliative care and adds to the development of strategies to overcome implementation challenges. How effective these interventions are at facilitating implementation still needs to be established, and future work using process evaluations will be beneficial in assessing and understanding which implementation strategies are most effective for integrating outcome measures into practice.

Conclusion

The aim of this study was to understand and explain the processes that underpin successful implementation of outcome measures within a palliative care context. Factors influencing implementation resided at individual and organisational levels. For individuals, it was important that staff were confident in their understanding of which measures to use, when, how, and why, and felt included in the implementation process. At an organisational level, important factors to implementation included: ensuring up-to-date and regular training for staff, that effective electronic systems were in place to input, view, and extract outcome measures, everyday practice was built around their use, and that staff using measures were provided with timely feedback. Addressing these factors is key to driving the implementation and sustained use of outcome measures by facilitating behaviour change in staff and creating environments in which their effective and safe use is possible. We provide key questions that are essential to consider in dealing with these issues.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-pmj-10.1177_0269216320972049 for Implementing person-centred outcome measures in palliative care: An exploratory qualitative study using Normalisation Process Theory to understand processes and context by Andy Bradshaw, Martina Santarelli, Malene Mulderrig, Assem Khamis, Kathryn Sartain, Jason W. Boland, Michael I. Bennett, Miriam Johnson, Mark Pearson and Fliss E. M. Murtagh in Palliative Medicine

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Rebecca Corridan for proof-reading and formatting.

Footnotes

Author contributions: A.B.: conceptualisation and design, data collection, analysis, interpretation of data, led the writing process and drafted original article and reviewing for critically important content. M.S.: data collection, interpretation of data and reviewing for critically important content. M.M.: data collection. A.K.: interpretation of data and reviewing for critically important content. K.S.: interpretation of data and reviewing for critically important content. J.B.: interpretation of data and reviewing for critically important content. M.B.: interpretation of data and reviewing for critically important content. M.J.: interpretation of data and reviewing for critically important content. M.P.: conceptualisation and design; interpretation of data and reviewing for critically important content. F.E.M.: conceptualisation and design, interpretation of data and reviewing for critically important content. All authors take responsibility for appropriate portions of the content of this article

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was supported by Yorkshire Cancer Research through the RESOLVE Programme [L412].

ORCID iDs: Andy Bradshaw  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1717-1546

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1717-1546

Assem Khamis  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5567-7065

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5567-7065

Jason W. Boland  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5272-3057

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5272-3057

Miriam Johnson  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6204-9158

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6204-9158

Mark Pearson  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7628-7421

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7628-7421

Fliss E. M. Murtagh  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1289-3726

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1289-3726

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Antunes B, Harding R, Higginson IJ, et al. Implementing patient-reported outcome measures in palliative care clinical practice: a systematic review of facilitators and barriers. Palliat Med 2014; 28(2): 158–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. De Vet HC, Terwee CB, Mokkink LB, et al. Measurement in medicine: a practical guide. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Etkind SN, Daveson BA, Kwok W, et al. Capture, transfer, and feedback of patient-centered outcomes data in palliative care populations: does it make a difference? A systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manag 2015; 49(3): 611–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hill N. Use of quality-of-life scores in care planning in a hospice setting: a comparative study. Int J Palliat Nurs 2002; 8(11): 540–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Currow DC, Allingham S, Yates P, et al. Improving national hospice/palliative care service symptom outcomes systematically through point-of-care data collection, structured feedback and benchmarking. Support Care Cancer 2015; 23(2): 307–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dudgeon D. The impact of measuring patient-reported outcome measures on quality of and access to palliative care. J Palliat Med 2018; 21(S1): S-76–S-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Milazzo S, Hansen E, Carozza D, et al. How effective is palliative care in improving patient outcomes? Curr Treat Options Oncol 2020; 21(2): 12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Krawczyk M, Sawatzky R, Schick-Makaroff K, et al. Micro-meso-macro practice tensions in using patient-reported outcome and experience measures in hospital palliative care. Qual Health Res 2019; 29(4): 510–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Högberg C, Alvariza A, Beck I. Patients’ experiences of using the integrated palliative care outcome scale for a person-centered care: a qualitative study in the specialized palliative home-care context. Nurs Inq 2019; 26(4): e12297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bausewein C, Daveson BA, Currow DC, et al. EAPC white paper on outcome measurement in palliative care: improving practice, attaining outcomes and delivering quality services–recommendations from the European association for palliative care (EAPC) task force on outcome measurement. Palliat Med 2016; 30(1): 6–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dunckley M, Aspinal F, Addington-Hall JM, et al. A research study to identify facilitators and barriers to outcome measure implementation. Int J Palliat Nurs 2005; 11(5): 218–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lind S, Sandberg J, Brytting T, et al. Implementation of the integrated palliative care outcome scale in acute care settings–a feasibility study. Palliat Support Care 2018; 16(6): 698–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pinto C, Bristowe K, Witt J, et al. Perspectives of patients, family caregivers and health professionals on the use of outcome measures in palliative care and lessons for implementation: a multi-method qualitative study. Ann Palliat Med 2018; 7(Suppl 3): S137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lind S, Wallin L, Fürst CJ, et al. The integrated palliative care outcome scale for patients with palliative care needs: factors related to and experiences of the use in acute care settings. Palliat Support Care 2019; 17(5): 561–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nilsen P. Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implement Sci 2015; 10(1): 53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Stover AM, Haverman L, van Oers HA, et al. Using an implementation science approach to implement and evaluate patient-reported outcome measures (PROM) initiatives in routine care settings. Qual Life Res. [published online ahead of print 10 Jul 2020. DOI: 10.1007/s11136-020-02564-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bausewein C, Schildmann E, Rosenbruch J, et al. Starting from scratch: implementing outcome measurement in clinical practice. Ann Palliat Med 2018; 7(S3): S253–S261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kislov R, Pope C, Martin GP, et al. Harnessing the power of theorising in implementation science. Implement Sci 2019; 14(1): 103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. May CR, Mair F, Finch T, et al. Development of a theory of implementation and integration: normalization process theory. Implement Sci 2009; 4(1): 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. May CR, Cummings A, Girling M, et al. Using normalization process theory in feasibility studies and process evaluations of complex healthcare interventions: a systematic review. Implement Sci 2018; 13(1): 80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Murray E, Treweek S, Pope C, et al. Normalisation Process Theory: a framework for developing, evaluating and implementing complex interventions. BMC Med 2010; 8(1): 63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. May C. Towards a general theory of implementation. Implement Sci 2013; 8(1): 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Burr V. Social constructionism. London: Routledge, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Etikan I, Musa SA, Alkassim RS. Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. Am J Theor Appl Stat 2016; 5(1): 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Saunders B, Sim J, Kingstone T, et al. Saturation in qualitative research: exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual Quant 2018; 52(4): 1893–1907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, et al. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol 2013; 13(1): 117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ritchie L, Lewis J, Nicholls CM, et al. Qualitative research practice: a guide for social science students and researchers. 2nd ed. Los Angeles, CA: Sage, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pope C, Ziebland S, Mays N. Qualitative research in health care: analysing qualitative data. BMJ 2000; 320(7227): 114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sparkes AC, Smith B. Judging the quality of qualitative inquiry: criteriology and relativism in action. Psychol Sport Exerc 2009; 10(5): 491–497. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tracy SJ. Qualitative quality: eight “big-tent” criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qual Inq 2010; 16(10): 837–851. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Smith B, Caddick N. Qualitative methods in sport: a concise overview for guiding social scientific sport research. Asia Pac J Sport Soc Sci 2012; 1(1): 60–73. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bausewein C, Simon ST, Benalia H, et al. Implementing patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) in palliative care-users’ cry for help. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2011; 9(1): 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Daveson B, Simon S, Benalia H, et al. Are we heading in the same direction? European and African doctors’ and nurses’ views and experiences regarding outcome measurement in palliative care. Palliat Med 2012; 26(3): 242–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Smith B. Generalizability in qualitative research: misunderstandings, opportunities and recommendations for the sport and exercise sciences. Qual Res Sport Exerc Health 2018; 10(1): 137–149. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-pmj-10.1177_0269216320972049 for Implementing person-centred outcome measures in palliative care: An exploratory qualitative study using Normalisation Process Theory to understand processes and context by Andy Bradshaw, Martina Santarelli, Malene Mulderrig, Assem Khamis, Kathryn Sartain, Jason W. Boland, Michael I. Bennett, Miriam Johnson, Mark Pearson and Fliss E. M. Murtagh in Palliative Medicine