Abstract

Background:

Chronic pain is a common and distressing symptom reported by patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD). Clinical practice and research in this area do not appear to be advancing sufficiently to address the issue of chronic pain management in patients with CKD.

Objectives:

To determine the prevalence and severity of chronic pain in patients with CKD.

Design:

Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Setting:

Interventional and observational studies presenting data from 2000 or later. Exclusion criteria included acute kidney injury or studies that limited the study population to a specific cause, symptom, and/or comorbidity.

Patients:

Adults with glomerular filtration rate (GFR) category 3 to 5 CKD including dialysis patients and those managed conservatively without dialysis.

Measurements:

Data extracted included title, first author, design, country, year of data collection, publication year, mean age, stage of CKD, prevalence of pain, and severity of pain.

Methods:

Databases searched included MEDLINE, CINAHL, EMBASE, and Cochrane Library, last searched on February 3, 2020. Two reviewers independently screened all titles and abstracts, assessed potentially relevant articles, and extracted data. We estimated pooled prevalence of overall chronic pain, musculoskeletal pain, bone/joint pain, muscle pain/soreness, and neuropathic pain and the I2 statistic was computed to measure heterogeneity. Random effects models were used to account for variations in study design and sample populations and a double arcsine transformation was used in the model calculations to account for potential overweighting of studies reporting either very high or very low prevalence measurements. Pain severity scores were calibrated to a score out of 10, to compare across studies. Weighted mean severity scores and 95% confidence intervals were reported.

Results:

Sixty-eight studies representing 16 558 patients from 26 countries were included. The mean prevalence of chronic pain in hemodialysis patients was 60.5%, and the mean prevalence of moderate or severe pain was 43.6%. Although limited, pain prevalence data for peritoneal dialysis patients (35.9%), those managed conservatively without dialysis (59.8%), those following withdrawal of dialysis (39.2%), and patients with earlier GFR category of CKD (61.2%) suggest similarly high prevalence rates.

Limitations:

Studies lacked a consistent approach to defining the chronicity and nature of pain. There was also variability in the measures used to determine pain severity, limiting the ability to compare findings across populations. Furthermore, most studies reported mean severity scores for the entire cohort, rather than reporting the prevalence (numerator and denominator) for each of the pain severity categories (mild, moderate, and severe). Mean severity scores for a population do not allow for “responder analyses” nor allow for an understanding of clinically relevant pain.

Conclusions:

Chronic pain is common and often severe across diverse CKD populations providing a strong imperative to establish chronic pain management as a clinical and research priority. Future research needs to move toward a better understanding of the determinants of chronic pain and to evaluating the effectiveness of pain management strategies with particular attention to the patient outcomes such as overall symptom burden, physical function, and quality of life. The current variability in the outcome measures used to assess pain limits the ability to pool data or make comparisons among studies, which will hinder future evaluations of the efficacy and effectiveness of treatments. Recommendations for measuring and reporting pain in future CKD studies are provided.

Trial registration:

PROSPERO Registration number CRD42020166965

Keywords: systematic review, meta-analysis, chronic pain, prevalence, chronic kidney disease

Abrégé

Contexte:

La douleur chronique est un symptôme affligeant fréquemment rapporté par les patients atteints d’insuffisance rénale chronique (IRC). Pourtant, la recherche et la pratique clinique dans ce domaine ne semblent pas progresser suffisamment pour aborder sa gestion dans cette population.

Objectif:

Déterminer la prévalence et l’intensité de la douleur chronique chez les patients atteints d’IRC.

Type d’étude:

Revue systématique et méta-analyse.

Sources:

Les études observationnelles et interventionnelles présentant des données depuis l’an 2000. Ont été exclus les cas d’insuffisance rénale aigüe et les études portant sur une population ayant une cause, un symptôme ou une maladie concomitante en particulier.

Sujets:

Des adultes atteints d’IRC de stade 3 à 5, y compris des patients dialysés et des patients non dialysés pris en charge de façon conservatrice.

Mesures:

Les données extraites comprenaient le titre de l’article, le nom de l’auteur principal, le type d’étude, le pays où s’est tenue l’étude, l’année de collection des données, l’année de publication, l’âge médian des sujets, le stade de l’IRC, la prévalence de la douleur et son intensité.

Méthodologie:

Les données ont été colligées dans MEDLINE, CINAHL, EMBASE et la bibliothèque Cochrane. La dernière consultation date du 3 février 2020. Deux examinateurs ont, de façon indépendante, trié les titres et les abrégés, évalué les articles potentiellement pertinents et extrait les données. La prévalence combinée de la douleur chronique globale, de la douleur musculo-squelettique, de la douleur osseuse/articulaire, de la douleur musculaire et de la douleur neuropathique a été évaluée, et le calcul de la statistique I2 a servi à mesurer l’hétérogénéité. Des modèles à effets aléatoires ont été employés pour tenir compte des variations selon le type d’étude et les populations échantillonnées. Les calculs de ces modèles ont subi une double transformation arc-sinus pour tenir compte d’une potentielle surpondération des études comportant des mesures de prévalence très importantes ou très faibles. Pour fins de comparaison, les scores d’intensité de la douleur ont été étalonnés à un score sur 10. Des scores d’intensité moyenne pondérée et des intervalles de confiance à 95 % ont été mentionnés.

Résultats:

Soixante-huit études ont été incluses, lesquelles portaient sur un total de 16 558 patients dans 26 pays. La prévalence moyenne de la douleur chronique chez les patients hémodialysés était de 60,5 %; la prévalence moyenne de la douleur modérée ou sévère était de 43,6 %. Quoique limitées, les données portant sur des patients sous dialyse péritonéale (35,9 %), des patients suivant des traitements conservateurs sans dialyse (59,8 %), des patients ayant arrêté la dialyse (39,2 %) ou des patients atteints d’un stade inférieur d’IRC (61,2 %) suggèrent une prévalence tout aussi élevée.

Limites:

Les études incluses manquaient de cohérence dans leur approche pour définir la chronicité et la nature de la douleur. Les mesures utilisées pour déterminer l’intensité de la douleur étaient variables, ce qui a limité la comparaison des résultats entre les populations. La plupart des études indiquaient des scores moyens d’intensité pour l’ensemble de la cohorte plutôt que la prévalence (numérateur et dénominateur) de chacune des catégories d’intensité (légère, modérée et sévère). Les scores moyens d’intensité pour une population ne permettent pas « les analyses de répondants » et la compréhension de la douleur cliniquement pertinente.

Conclusion:

La douleur chronique est fréquente et souvent intense dans les diverses populations de patients atteints d’IRC, ce qui confirme la gestion de la douleur chronique comme priorité clinique et de recherche. Les recherches futures devraient permettre une meilleure compréhension des déterminants de la douleur chronique et évaluer l’efficacité des stratégies de gestion de la douleur en accordant une attention particulière aux résultats des patients, notamment au fardeau global des symptômes, à la fonction physique et à la qualité de vie. La capacité de regrouper des données ou de faire des comparaisons entre les études est limitée par la variabilité actuelle des mesures utilisées pour évaluer la douleur, ce qui entravera les futures évaluations de l’efficacité des traitements. Des recommandations pour mesurer et signaler la douleur dans les futures études sur l’IRC sont fournies.

Introduction

Patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) experience multiple and burdensome symptoms, the number and severity of which have been described as being similar to those of cancer patients hospitalized in palliative care settings.1-9 The high symptom burden in patients with CKD negatively affects patients’ health-related quality of life (HRQL) and functional capacity. Hence, symptom management has been identified as a top priority for patients with CKD.10 A recent scoping review conducted as part of Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes’ (KDIGO) effort to develop formal international recommendations for kidney supportive care reinforced that chronic pain is a common and distressing symptom reported by patients with CKD.11 It is often not possible to completely alleviate chronic pain. The clinical aim is to reduce pain to levels where function is not adversely affected, which is typically perceived as “mild” pain or pain rated as 0 to 3 on a 0 to 10 numerical rating scale (NRS).12,13 However, clinical practice and research in this area do not appear to be advancing sufficiently to address the issue of chronic pain management in patients with CKD. If quality person-centered care is to be delivered, assessment and treatment strategies must be developed and integrated to align care with patient preferences and treatment goals.

Our main objective was to determine the prevalence and severity of chronic pain across broad populations of patients with CKD glomerular filtration rate (GFR) categories (G) 3 to 5. We hypothesized that extensive data exists illustrating a high pain burden across CKD G3-5.

Methods

Eligibility Criteria and Search Strategy

The literature search was developed and conducted by an experienced librarian; PROSPERO Registration number CRD42020166965. Inclusion and exclusion criteria are listed in Table 1. We included all interventional and observational studies that presented original data of the prevalence and severity of chronic pain in patients with CKD G3-5. We included studies presenting data from 2000 or later, given that the CKD population, especially those starting dialysis, have become increasingly older with greater comorbidity, which may add to the burden of chronic pain. Single case studies or case series were excluded, as were studies that were presented only as abstracts, posters, or letters to the Editor. Articles published in a language other than English were translated and included. Eligible patient populations included CKD G3-5 and ≥18 years of age. Studies that only enrolled patients with a primary diagnosis of acute kidney injury or kidney transplant patients were excluded as were studies that limited the study population to a specific cause, symptom, and/or comorbidity (with the exception of chronic pain) of CKD as these studies were outside the scope of our study objectives. Dialysis patients also experience acute pain syndromes, but these are distinct entities from chronic pain with different trajectories and impact on HRQL and function. Hence, studies that were limited to acute pain or pain related to dialysis treatment were also excluded.

Table 1.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria.

| Description | |

|---|---|

| Population | CKD GFR categories 3,4,5 (pre-dialysis, dialysis, or CKM) ≥18 years of age Any treatment type (peritoneal dialysis, hemodialysis, or CKM) Must be identified as having CKD prior to enrollment in study |

| Outcome | Prevalence of pain (%) Prevalence of pain in categories of severity (%) (eg, mild/mod/severe; or 0-3/10, 4-6/10, 7-10/10, respectively) Studies must have identified cases (pain) and total cohort number to calculate prevalence |

| Study design | Cross-sectional studies Observational studies Case-control studies Cross-over trials Clinical trials Chart reviews |

| Exclusion criteria | <18 years of age Case series, abstracts, posters, reviews, opinions Acute kidney injury Kidney transplant, unless clearly identified as having CKD (stage 3-5 or eGFR lower than 60) Data (initial assessment) prior to 2000 Population limited to a specific cause of ESKD or selected based on specific symptom/comorbidity (except for chronic pain) Acute pain or pain related to dialysis treatment Missing raw data, numerator, or denominator |

Note. CKD = chronic kidney disease; GFR = glomerular filtration rate; CKM = conservative kidney management; eGFR = estimated glomerular filtration rate; ESKD = end-stage kidney disease.

Data Items

Outcomes of interest were prevalence and severity of chronic or persistent pain, as defined by the individual studies, recognizing that definitions of chronic pain were likely to vary. To determine prevalence, both the number of cases of pain and the total number within the cohort had to be reported. In addition, eligible studies needed to report pain as either general overall pain or pain broken down into categories of musculoskeletal pain, bone/joint pain, muscle pain/soreness, and/or neuropathic pain. This was considered important as the commonly used symptom screening tools in CKD use a combination of these categories to classify pain.11 In cases when more than one study appeared to report on the same cohort of patients, the study with the most complete data or highest methodological quality was included.

Information Sources

Information sources included electronic databases, reference lists of relevant literature, and Web sites of relevant networks, organizations, and societies. Relevant information sources that were obtained from colleagues and stakeholders and unpublished studies were also considered for inclusion. The electronic databases searched included MEDLINE, CINAHL, EMBASE, and Cochrane Library databases. These were last searched on February 3, 2020.

Study Selection, Data Collection, and Quality Assessment

Two reviewers independently screened all titles and abstracts to identify potentially relevant articles. Full texts of potentially relevant articles were retrieved and independently assessed by 2 reviewers for possible inclusion based on the predetermined selection criteria. The reference lists of reviews, systematic reviews, and guidelines were also reviewed to ensure all relevant studies were identified. The 2 reviewers compared individually recorded decisions for inclusion and exclusion and disagreements were resolved based on discussion and consensus with a third reviewer. The research team developed a standardized data extraction table using Microsoft Excel. The 2 reviewers independently populated the table from the selected full-text articles. The data extracted from each study included year and country of study, number of study participants, patient population, age, definition of pain, pain assessment tools used, and the prevalence and severity of pain. The 2 data extraction tables were subsequently compared and cross-checked for accuracy and then merged into a single unified table for data analysis and presentation in the article. Study quality was also reviewed independently by 2 reviewers using the McMaster University Critical Review for Quantitative Studies.14 This included assessing the study design, study sample, outcomes of interest, statistical analysis, and final conclusions.

Data Analysis

Meta-analyses of prevalence data were conducted in Microsoft R Open version 3.4.1, using package meta to estimate the pooled prevalence and 95% confidence intervals.15,16 Random effects models were used to account for variations in study design and sample populations with results plotted using forest plots. A double arcsine transformation was used in the model calculations to account for the possible overweighting of studies reporting either very high or very low prevalence measurements.17 Heterogeneity between the estimates was assessed using I2 statistics.18 The I2 value is the percentage of total observed variation across studies due to real heterogeneity rather than chance; a value of greater than 75% is indicative of high heterogeneity. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist was used in the reporting of this work.

The prevalence of overall chronic pain, musculoskeletal pain, bone/joint pain, muscle pain/soreness, and neuropathic pain were estimated. Some studies presented the prevalence of pain based on severity characterized as mild, moderate, or severe, with others reporting the prevalence of moderate to severe chronic pain. For those studies that reported prevalence by pain intensity, information on clinically relevant moderate to severe and severe pain was included.

Pain severity scores were calibrated to a score out of 10, to compare across studies. We ensured all scales were oriented such that a severity score of 0 represented no pain and 10 represented the worst pain. One of the studies had its score presented in the opposite orientation, which was reversed for the sake of this analysis.19 Pain scores of zero were assumed for patients not reporting pain. Mean pain severity scores were recalculated to reflect the severity of pain for patients reporting pain in the cases where reported severity scores included those not experiencing pain (ie, removal of scores equaling 0). Weighted mean severity scores and 95% confidence intervals were reported.20

Meta-regressions were conducted where the number of studies was sufficiently large enough to yield robust results (ie, 10 or more).21,22 Funnel-plot asymmetry was tested using a Peters’ regression to assess the possibility of publication bias.16,23 Meta-regressions on various categorical and continuous variables were conducted, both to estimate the effect of these variables on estimated prevalence and to investigate possible sources of heterogeneity. Covariates included publication year, sample size, age, country, definition of pain, and type of measurement scale used. Bubble plots were used to illustrate the effect of continuous covariates and stratified forest plots to illustrate the effects of categorical covariates.

Results

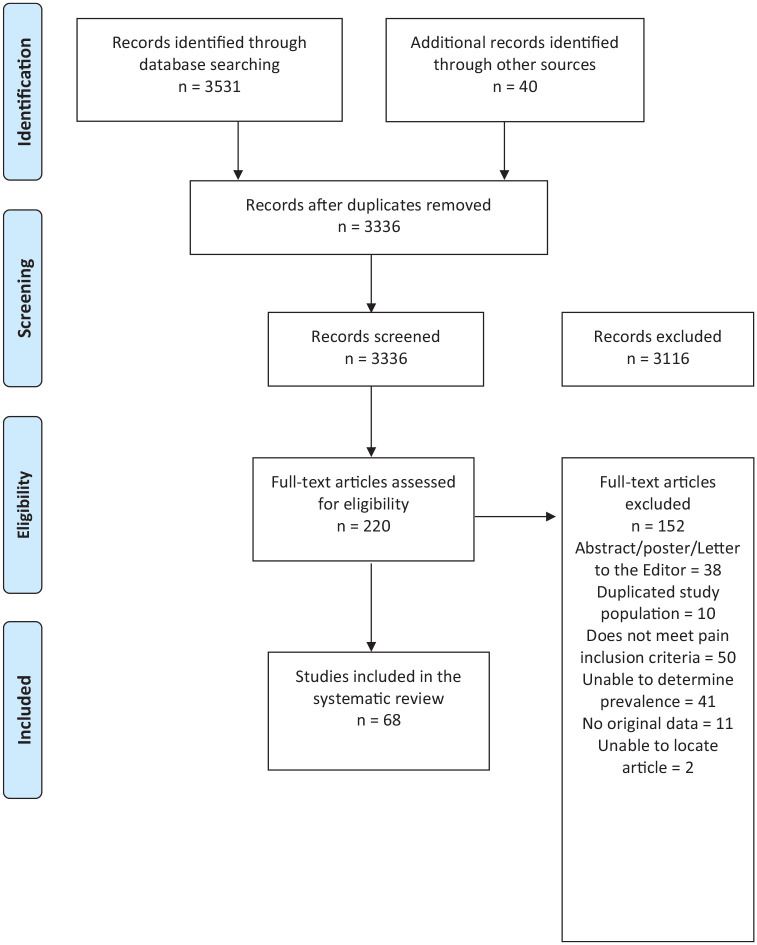

The literature review yielded 3336 citations of which 220 were deemed eligible for full-text review. Of these, 152 studies were excluded leaving 68 studies for inclusion in the analysis.2,3,5,7,8,14,19,24-84 The flow chart in Figure 1 outlines this process, including reasons for exclusion. Supplemental Table S1 provides a list of excluded studies with reasons for exclusion.

Figure 1.

Literature search PRISMA flow diagram.

PRISMA = Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Details of Included Studies

Details of the 68 included studies are reported in Table 2 and include data from 16 558 patients from 26 countries. Forty-eight of the studies examined 8464 hemodialysis (HD) patients from 23 countries,5,7,8,14,24,28,29,32,34-41,43-46,49,51-56,58,59,61-63,65-68,70,72,73,75,76,78-84 3 studies from 3 countries included data from 679 peritoneal dialysis (PD) patients,24,49,81 and 8 studies from 6 countries reported data from 3701 patients on either HD or PD (without separating treatment groups).2,3,25,26,60,69,71,77 Two studies assessed 112 patients from Canada and the United States following the withdrawal of dialysis.19,33 Eight studies explored pain in 1361 conservative kidney management (CKM), ie, GFR category 4 (G4) and/or 5 (G5), patients from 5 countries who had chosen conservative (non-dialytic) kidney management (CKM).27,30,47,48,58,64,74,75 Nine studies from Malaysia, Saudi Arabia, Spain, Taiwan, and the United States presented data from 2241 pre-dialysis patients with various stages of CKD.24,31,42,50,57,60,71,72,78

Table 2.

Characteristics and Results of Included Studies.

| Study | Country | Patient population | Number of patients | Mean age (years) | Pain definition/tool | Type of severity scale | Description of severity scale | Mean pain severity | Pain prevalence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abdel-Kader et al60 | United States | CKD G3-5ND (Pre-dialysis) Prevalent HD or PD |

177 CKD: 87 HD: 70 PD: 20 |

CKD: 51 HD/PD: 54 |

Pain in the last 7 days as measured by the Dialysis Symptom Index | 1-5 VRS | 1 = Not at all bothersome 5 = Bothers very much |

Median Bone/Joint Pain Score: CKD: 3/5 Dialysis: 2.5/5 Median Muscle Soreness Score: CKD: 2/5 Dialysis: 2/5 |

Prevalence of bone/joint pain in the dialysis group was 33.3% and 39.1% in the CKD group. Prevalence of muscle soreness pain in the dialysis group was 33.3% and 24.1% in the CKD group. |

| Almutary et al24 | Saudi Arabia | CKD G4-5ND (Pre-dialysis) Prevalent HD or PD |

436 HD: 287 PD: 42 G4: 69 G5ND: 38 |

48 | Pain as measured by the Chronic Kidney Disease Symptom Burden Index, duration not specified | 0-10 NRS | 0 = None 10 = Very much |

Bone/Joint Pain Overall: 5.24/10 HD: 5.85/10 PD: 3.15/10 G4: 3.48/10 G5ND: 2.69/10 Muscle Soreness HD: 4.76/10 PD: 2.67/10 G4: 2.36/10 G5ND: 2.75/10 |

Prevalence of bone/joint pain in total cohort was 60.3%. Prevalence bone/joint in dialysis patients was 68.7%. Prevalence of bone/joint pain in CKD G4-5ND was 34.6%. The prevalence of bone/joint pain in the individual groups was 71.4% for HD, 50.0% for PD, 30.4% for CKD G4, and 42.1% for CKD G5ND. Prevalence of muscle soreness in total cohort was 46.1%. The prevalence of muscle soreness in the individual groups was 55.4% for HD, 21.4% for PD, 36.2% for CKD G4, and 21.1% for CKD G5ND. |

| Amro et al25 | Norway | Prevalent HD or PD | 301 HD: 243 PD: 58 |

60 | Pain in last 4 weeks as measured by the Kidney Disease and Quality of Life Short Form | 1-5 VRS | 1 = Not bothered at all 5 = Extremely bothered |

N/A | Prevalence of muscle soreness in total cohort was 77%. Approximately 50% of patients reported mild-moderate pain (2-3/5) and ~27% reported severe pain (4-5/5). |

| Amro et al26 | Norway | Prevalent HD or PD | 110 | 51 | Pain in last 4 weeks as measured by the Kidney Disease and Quality of Life Short Form | 1-5 VRS | 1 = Not bothered at all 5 = Extremely bothered |

Muscle Soreness: 63/100 (scores recalculated to 0-100; 0 = extremely bothered; 100 = not bothered at all) |

Prevalence of muscle soreness in total cohort was 78%. Prevalence of severe muscle soreness (4-5/5) was 27%. |

| Bah et al27 | Republic of Guinea | CKD G5ND (CKM) | 69 | 49 | Pain in last 4 weeks as measured by the 36 item Short Form Health-Survey | 1-6 VRS | 1 = None 6 = Very severe |

N/A | 100% of patients reported pain; either mild or severe. The prevalence of severe pain was 39.1%. |

| Balhara et al84 | United Stated | Prevalent HD | 49 Cases: 25 Control: 24 |

Cases: 54 Control: 55 |

Pain in the past 4 weeks as measured by the Kidney Disease and Quality of Life questionnaire (does not specify version) | 1-6 VRS | 1 = None 2 = Very mild 3 = Mild 4 = Moderate 5 = Severe 6 = Very severe |

N/A | Of the group that had missed at least one dialysis session prior to a visit to the emergency department 12% reported very mild/mild pain, 12% reported moderate pain, and 64% reported severe/very severe pain. Of the group that missed no dialysis sessions 45.8% reported very mild/mild pain, 4.2% reported moderate pain, and 8.3% reported severe/very severe pain. |

| Barakzoy and Moss61 | United States | Prevalent HD | 62 | 65 | Pain measured by the Short-Form McGill Pain Questionnaire, duration not specified | 10 cm VAS | 0 = No pain 10 = Worst possible pain |

N/A | Of the 143 patients that met the study inclusion criteria 54% reported pain. Of the patients reporting pain, the study recruited 62 participants. |

| Berman et al28 | United States | Prevalent HD | 57 Transplant Ineligible: 32 Transplant Eligible: 25 |

Transplant Ineligible: 70 Transplant Eligible: 72 |

Pain in the last 7 days as measured by the Dialysis Symptom Index | 1-5 VRS | 1 = Not at all 5 = Quite a bit |

Bone/Joint Pain (estimated from figure): Transplant Ineligible = ~4/5 Transplant Eligible = ~3.3/5 Muscle Soreness (estimated from figure): Transplant Ineligible = ~3.6/5 Transplant Eligible = ~2.3/5 |

Prevalence of bone/joint pain ~40% and the prevalence of muscle soreness was ~31%. |

| Bossola et al62 | Italy | Prevalent HD | 37 Fatigued: 107 Not Fatigued: 30 |

Fatigued: 64 Not Fatigued: 57 |

Pain in the last 7 days as measured by the Dialysis Symptom Index | 1-5 VRS | 1 = Not bothersome 5 = Bothers very much |

Bone/joint pain: Fatigued: 2.63/5 Not fatigued: 1.45/5 Muscle soreness: Fatigued: 1.68/5 Not fatigued: 1.56/5 |

Total prevalence of bone or joint pain was 58.4%. The fatigued group reported a higher prevalence of bone and joint pain than the non-fatigued group (64.4% vs 36.6%, respectively). The total prevalence of muscle soreness was 46.7%. The fatigued group reported a higher prevalence of muscle soreness than the non-fatigued group (54.2% vs 20%, respectively). |

| Bouattar et al29 | Morocco | Prevalent HD | 67 | 44 | Pain lasting more than 3 months | 0-10 VDS | 0 = Absent 2 = Low 4 = Moderate 6 = Severe 8 = Very severe 10 = Beyond |

N/A | Prevalence of pain was 50.7%. The intensity of pain was low in 3%, moderate in 41%, severe in 44%, and very severe in 12% of patients reporting pain. |

| Brennan et al30 | Australia | CKD G5ND (CKM) | 42 | 83 | Pain in the last 7 days as measured by the Patient Outcome Scale symptom module (renal version) | 1-5 VRS | 1 = None 5 = Overwhelming |

N/A | Pain was reported by 45% of patients at their first visit to the renal supportive care clinic. Prevalence of moderate pain was ~17% and prevalence of severe and overwhelming pain was ~16%. |

| Caravaca et al31 | Spain | CKD G4-5ND | 1169 | 65 | Pain for more than 3 months, not attributed to trauma and requiring analgesic therapy at least 3 times/week | Yes/No | N/A | N/A | Prevalence of chronic musculoskeletal pain was 38%. |

| Carreon et al32 | United States | Prevalent HD | 75 | 59 | Pain in the last 7 days as measured by the Dialysis Symptom Index | 1-5 VRS | 1 = None 5 = Overwhelming |

N/A | Bone and/or joint pain was reported by 37% of patients; 71% of patients described it as moderate to severe. Of those reporting bone and joint pain, ~29% where a little bothered, ~36% were somewhat bothered, ~21% were bothered quite a bit, and ~14% were bothered very much (estimated from graph). |

| Chan et al64 | Hong Kong | CKD G5ND (CKM) | Total: 253 Patients with Pain: 107 Patients without Pain: 146 |

Patients with Pain: 79 Patients without pain: 80 |

Chronic Pain lasting more than 3 months | 10 cm VAS | 0-3 = Mild 4-6 = Moderate 7-10 = Intense |

N/A | Of those with pain at the first consultative visit, 49% had chronic pain. |

| Chater et al33 | Canada | Dialysis Withdrawal | 33 over study period 32 for last 24 hours |

70 | Pain during the entire dialysis discontinuation period and in the last 24 hours | Yes/No | N/A | N/A | Pain prevalence was 53% at the time of withdrawal of dialysis and decreased to 20% in the last 24 hours with provision of palliative care. |

| Cho et al63 | South Korea | Prevalent HD | 230 | 61 | Pain in the last 7 days as measured by the Dialysis Symptom Index—Korean Version | 0-4 VRS | 0 = Not at all bothersome 4 = Very bothersome |

Bone/Joint Pain: 2.41/4 Muscle Pain: 2.24/4 |

The prevalence of bone/joint pain was 42.2% and the prevalence of muscle soreness was 38.3%. |

| Claxton et al34 | United States | Prevalent HD | 62 | 59 | Pain in the last 7 days as measured by the Dialysis Symptom Index | 0-4 VRS | 0 = Not bothersome 4 = Bothers me very much |

2.8/4 | Prevalence of bone and joint pain was 53%. |

| Cohen et al19 | United States and Canada |

Dialysis Withdrawal | 79 | 70 | Pain in the last 24 hours of life as measured by the Dialysis Discontinuation Quality of Dying questionnaire | 1-5 VRS | 1 = Severe 5 = Absent |

N/A | Pain was the most common symptom in the last 24 hours; prevalence was 42% and prevalence of severe pain was 5%. |

| Danquah et al35 | United States | Prevalent HD | 100 | 56 | Pain since last dialysis session as measured by the Dialysis Frequency, Severity, and Symptom Burden Index | 1-10 NRS | 1 = Least severe 10 = Most severe | Bone/Joint Pain: 2.76/10 | Prevalence of bone/joint pain was 39%. |

| da Costa et al37 | Brazil | Prevalent HD | 49 | Ranged from 20 to 88 (46.9% were older than 50) | Pain in last 4 weeks as measured by the Kidney Disease and Quality of Life Short Form | 1-5 VRS | 1 = Not bothered at all 5 = Extremely bothered |

N/A | Prevalence of muscle pain was 69.4%. 34.7% of patients were bothered a little by pain, 14.3% were moderately bothered, 14.3% were very much bothered, and 6.1% were extremely bothered by muscle soreness. |

| Davison36 | Canada | Prevalent HD | 205 | 60 | Pain lasting more than 3 months measured by the Brief Pain Inventory | 0-10 NRS | 0 = No pain 10 = Severe pain |

5.61/10 | Prevalence of pain was 50%. Moderate/severe pain was reported in 82.5% of the patients with pain (41.3% of total study cohort). |

| Davison et al3 | Canada | Prevalent HD or PD | 507 | 64 | Pain in the last 7 days as measured by the modified Edmonton Symptom Assessment System | 0-10 NRS | 0 = No pain 10 = Severe pain |

3.6/10 | The prevalence of moderate or severe pain was 47.7% of total study cohort. |

| Davison and Jhangri2 | Canada | Prevalent HD or PD | 591 | 61 | Pain as measured by the modified Edmonton Symptom Assessment System, duration not stated | 0-10 NRS | 0 = No pain 10 = Severe pain |

3.5/10 | Prevalence of pain in total cohort was 72.4%. Prevalence of moderate or severe pain was 46.5% of those with pain (33.7% of the total study cohort). |

| de Freitas et al65 | Brazil | Prevalent HD (≥60 years old) |

35 | N/A | Pain in the last 4 weeks as measured by the Kidney Disease and Quality of Life Short Form | 1-5 VRS | 1 = Do not bother me at all 5 = Extremely bothered |

N/A | The total prevalence of muscle aches was 54.2%. Of the total study sample, 31.4% reported muscle pain that bothered them a little bit, 11.4% reported moderately bothered by pain, 2.9% reported being very bothered by pain, and 8.6% reported being extremely bothered. |

| Demirci et al83 | Turkey | Prevalent HD | 140 FMS: 20 Non-FMS: 120 |

FMS: 55 Non-FMS: 55 |

Chronic widespread pain for at least 3 months | N/A | N/A | N/A | Prevalence of chronic widespread pain in the total study cohort was 44.9%. |

| El Harraqui et al38 | Morocco | Prevalent HD | 93 | 55 | Pain lasting more than 3 months | 10 cm VAS | 0 = None 1-4 = Mild 5-6 = Moderate 7-8 = Severe 9-10 = Unbearable |

N/A | Prevalence of pain was 70.9%. It was mild, moderate, severe, or unbearable in 42.8%, 23.8%, 19%, and 14.2% in those with pain, respectively. |

| Er et al39 | Turkey | Prevalent HD | 95 | 52 | Pain lasting more than 3 months measured by the McGill-Melzack pain questionnaire | 0-5 VRS | 0 = No pain 1 = Mild 2 = Disturbing 3 = Severe 4 = Very severe 5 = Intolerable |

N/A | Prevalence of chronic pain was 32.6%. Prevalence of disturbing to intolerable (moderate to severe) pain was 71.7% of those with instant, acute, or chronic pain. |

| Fidan et al66 | Turkey | Prevalent HD | 50 | 56 | Presence of musculoskeletal problems recorded patient’s medical history via yes/no | N/A | N/A | N/A | The prevalence of bone pain was 48%. The prevalence of myalgia was 62% and the prevalence of arthralgia was 60%. |

| Fleishman et al67 | Israel | Prevalent HD | 336 | 64 | Pain over the past 24 hours as measured by the Brief Pain Inventory | 10 cm VAS | 0 = None 10 = Worst possible |

7.2/10 | Of the study participants, 82% had experienced pain in the 24-hour period before their interview. Of patients with current pain lasting more than 24 hours, 61.5% experienced neuropathic pain. The most common locations of pain were foot pain (62.5%), lower back pain (52.7%), shin pain (50.5%), and knee pain (46.6%). |

| Flythe et al68 | United States | Prevalent HD | 87 | N/A | Pain in the past 4 weeks as measured by a 28-question online survey created by Investigators | N/A | N/A | N/A | The prevalence of body aches or pain (other than cramps) was 75.6%. |

| Galain et al69 | Uruguay | Prevalent HD or PD | 493 | 61 | Pain in the last 4 weeks as measured by the Kidney Disease and Quality of Life 36 Items | 100 mm VAS | 0 = Extremely bothered 100 = Not bothered at all |

Muscle Soreness: 70/100 | The prevalence of muscle soreness was 58.7%, and 20.8% rated their muscle soreness as moderate to severe. |

| Gamondi et al8 | Southern Switzerland | Prevalent HD or HDF | 123 | 71 | Pain in the last 4 weeks | 10 cm VAS | 0 = No pain 10 = Unbearable pain |

~5.8/10 (estimated from figure) | Prevalence of pain was 66%. 60.5% of the patients with pain reported severe pain (defined as severity score of 8-10/10) representing 40.0% of the total study cohort. 21% reported moderate pain (pain score of 5-7/10), representing 13.9% of the total study cohort. Prevalence of musculoskeletal pain was 64%, neuropathic pain was 17%, and arteriopathic pain was 9%. |

| Golan et al40 | Israel | Prevalent HD | 100 | 65 | Pain lasting more than 3 months measured by the Brief Pain Inventory | 0-10 NRS | 0 = No pain 10 = Pain as bad as you can imagine |

N/A | Prevalence of chronic pain was 51%. Prevalence of severe pain was 19.6% (pain score of 7-10/10). Prevalence of moderate pain was 31.4% (pain score of 5-6/10). Of those with pain, 41.2% had neuropathic pain, 25.5% had back pain, 21.6% had other musculoskeletal pain, and 11.8% had joint pain. |

| Gómez Pozo et al70 | Spain | Prevalent HD | 134 | 68 | Pain in the last 7 days as measured by Brief Pain Inventory and McGill Pain Questionnaire (Spanish Versions) | 10 cm VAS | 0-4 = Mild 5-7 = Moderate 8-10 = Severe |

N/A | The prevalence of musculoskeletal pain was 24.6%. The prevalence of neuropathic pain was 1.5% and 11.9% for ischemic pain. |

| Gutiérrez Sánchez et al71 | Spain | CKD G4-5ND (Pre-dialysis) Prevalent HD or PD |

180 Pre-dialysis: 124 Dialysis: 56 (HD: 44, PD: 12) |

66 | Pain in the last 7 days as measured by the Palliative Outcome Symptom Scale-Renal | 0-4 VRS | 0 = None 4 = Overwhelming |

N/A | The total prevalence of pain was 53.1%. The prevalence of pain in dialysis patients was ~60% and ~51% in pre-dialysis patients. The prevalence of severe to overwhelming pain was 14.6%, ~21.8% moderate, and ~34.5% mild. |

| Hage et al82 | Lebanon | Prevalent HD | 89 | 68 | Clinical diagnosis of musculoskeletal symptoms | N/A | N/A | N/A | Musculoskeletal symptoms were reported by 76.4% of the patients. The main musculoskeletal symptom was pain (44.9%). |

| Harris et al41 | United States | Prevalent HD | 128 | 57 | Pain at times between dialysis sessions as measured by the Modified McGill Pain Questionnaire | 10 cm VAS | 0 = No pain 10 = Pain as bad as you can imagine |

Non-dialysis Days: 3.1/10 | Pain prevalence was 44%. The prevalence of moderate pain (4-6/10) was ~8.6 and 18.8% for severe pain (7-10/10) (estimated from figure). |

| Hsu et al42 | Taiwan | CKD G1-5ND (GFR <90, Pre-dialysis) |

456 G1: 129 G2: 110 G3: 113 G4: 81 G5ND: 23 |

63 | Non-traumatic musculoskeletal pain with a VAS score of >1 for more than 3 months | 100 mm VAS | 0 = No pain 100 = Very painful |

N/A | Prevalence of chronic musculoskeletal pain in the total study cohort was 53.3%. Of those with pain, 15.6% reported mild pain, 28.4% moderate pain, and 58% severe pain. Prevalence of chronic musculoskeletal pain in early CKD (CKD G1-2) was 49.4%. Of those with pain, 17.8% reported mild pain, 28% moderate pain, and 54.2% severe pain. Prevalence of chronic musculoskeletal pain in patients with CKD G3-4 was 58.2%. Of those with pain, 13.3% reported mild pain, 31.9% moderate pain, and 54.9% severe pain. Prevalence of chronic musculoskeletal pain in CKD G5ND was 52.2%. Of those with pain, 16.7% reported mild pain, 0% moderate pain, and 83.3% severe pain. |

| Jablonski43 | United States | Prevalent HD | 130 Clinic A: 83 Clinic B: 47 |

60 | Pain not defined. Investigators created an 11-item symptom measure. | 1-5 VRS | 1 = Not at all severe 5 = Very severe |

Bone/Joint Pain: 3.83/5 | Prevalence of joint pain was 48%. |

| Jhamb et al72 | United States | CKD G4-5ND (Pre-dialysis) Prevalent Dialysis (does not specify) |

Pre-dialysis: 82 Dialysis: 149 |

Pre-dialysis: 52 Dialysis: 56 |

Pain in the last 4 weeks as measured by the Short-Form 36. Clinically significant pain (≥50/100) |

0-100 NRS | 0 = Greatest pain 100 = Least pain |

N/A | The prevalence of clinically significant pain was 28.4% for the pre-dialysis CKD G4-5ND group and 30.1% for the dialysis group. |

| Kusztal et al73 | Poland | Prevalent HD | 205 | 60 | Chronic pain lasting more than 3 months. | 0-10 VRS 100 mm VAS |

VRS: 0 = None 1-3 = Mild 4-6 = Moderate 7-10 = Severe VAS: 0 = No pain 100 = Extreme pain |

N/A | Prevalence of chronic pain was 63.4%. Of those with chronic pain, 84% had bone-joint-muscle pain. Also, of those with pain 43% reported mild pain (1-3/10) and 57% reported moderate pain (4-6/10). The locations of pain were as follows: neck and shoulders 20.6%, back 13.7%, lumbar region 25%, bones in general 6.8%, lower extremity 28%, knee 15%, foot 23%, hand/wrist 7.6%, upper extremity 9.1%, and hips 10%. |

| Leinau et al5 | United States | Prevalent HD | 109 | 61 | Pain measured by a Short-form McGill Pain Questionnaire score > 0, duration not specified | 0-3 VRS | 0 = None 3 = Severe |

N/A | Prevalence of pain was 81%. Prevalence of pain for patients less than 60 years was 85% and for patients more than 60 years was 76%. |

| Lowney et al44 | United Kingdom/ Ireland | Prevalent HD | 893 United Kingdom: 529 Ireland: 364 |

65 | Pain in the last 7 days as measured by the Patient Outcome Scale symptom module (renal version) | 0-4 VRS | 0 = Absent 4 = Overwhelming |

N/A | Prevalence of pain was 64%. Pain was rated as severe or overwhelming by 16% of those that reported pain and moderate by 28%. |

| Masajtis-Zagajewska et al45 | Poland | Prevalent HD Transplant |

278 HD: 164 Transplant: 114 |

61 | Pain lasting for at least 3 months as measured by the Short-form McGill Pain Questionnaire | 0-5 VRS | 0 = No pain 1 = Mild 2 = Disturbing 3 = Severe 4 = Very severe 5 = Intolerable |

N/A | Pain prevalence was 73% for patients treated with HD. 54% of the HD group experienced more than 1 pain location. Pain was reported as severe in 55% of those with pain (40.2% of total study cohort), moderate in 40% (29.2% of total study cohort), and mild in 5% (3.7% of total study cohort). |

| Mathews46 | India | Prevalent HD | 110 | Majority (63.64%) were 50-60 | Pain not defined | Yes/No | N/A | N/A | Prevalence of pain was 81.8%. |

| Murphy et al74 | United Kingdom | CKD G4-5ND (CKM) |

55 | 82 | Pain in the last 3 days as measured by a modified Patient Outcome Scale symptom module | 0-4 VRS | 0 = Absent 4 = Overwhelming |

N/A | The overall prevalence of pain was 56.4%. Of those reporting pain, mild pain prevalence was 51.6%, moderate pain was 25.8%, severe pain was 12.9%, and overwhelming pain prevalence was 9.7% |

| Murtagh et al47 | United Kingdom | CKD G5ND (CKM) | 66 | 82 | Pain in the last 7 days as measured by the Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale Short Form. Investigators appended an additional 7 renal symptoms to survey | 0-5 VRS | 0 = Not at all 5 = Very much |

N/A | Physical symptoms identified using Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale Short Form: Prevalence of pain was 53%. Prevalence of moderate/severe pain was 32%. Prevalence of Added Renal Symptoms: Prevalence of Bone/Joint Pain was 58%; 20% experienced moderate/severe pain. Prevalence of muscle soreness was 30%; 5% experienced moderate/severe pain. |

| Murtagh et al48 | United Kingdom | CKD G5ND (CKM) | 49 | 81 | Pain in the last 7 days as measured by the Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale Short Form. Investigators appended an additional 7 renal symptoms to survey | 0-5 VRS | 0 = Not at all 5 = Very much |

N/A | Physical symptoms identified using Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale Short Form: Prevalence of pain was 73%. 41% had “very” distressing pain in the last month of life. Prevalence of Added Renal Symptoms: Prevalence of bone/joint pain was 57%; 24% had very distressing bone/joint pain. Prevalence of muscle soreness was 49%; 12% had very distressing muscle soreness. |

| Noordzij et al49

(NECOSAD) |

Netherlands | Prevalent HD or PD | 1469 HD: 896 PD: 573 |

59 | Pain in last 4 weeks as measured by the Kidney Disease and Quality of Life Short Form | 1-5 VRS | 1 = Not bothered at all 5 = Extremely bothered |

N/A | Prevalence of muscle pain in total cohort was 68%. Prevalence of muscle pain was significantly higher in patients treated with HD (71%) compared to patients treated with PD (64%), P = .02. The prevalence of muscle pain in total cohort at baseline was 68% and increased to 81% by year 4. In the total cohort the prevalence of muscle pain at baseline was significantly higher in patients who died (73% vs 67%, P = .03). |

| Pham et al50 | United States | CKD G1-5ND (Pre-dialysis) (Compared to 100 non-CKD controls) |

130 G1: 45 G2: 40 G3: 24 G4-5ND: 21 |

52 | Pain lasting at least 2 weeks | 10-point Rating Scale, does not specify type | Does not specify | G1: 4.9/10 G2: 4.8/10 G3: 5.4/10 G4-5ND: 5.7/10 |

Prevalence of overall chronic pain lasting at least 2 weeks for the entire cohort was 72.9%. Prevalence of pain in CKD G1 was 64%, 70% in G2, 71% in G3, and 75% for G4-5ND (estimated from figure). |

| Raj et al51 | Australia | Prevalent HD | 43 | 64 | Pain as measured by the Patient Outcome Scale symptom module (renal version), duration not specified | 0-4 VRS | 0 = None 4 = Overwhelming |

N/A | Prevalence of patients reporting pain as major (severe) was 35%. |

| Rodriguez Calero et al52 | Spain | Prevalent HD | 32 | 67 | Pain in the past 24 hours (outside the dialysis session) as measured by the Brief Pain Inventory | 0-10 NRS | 0 = No pain 10 = Worst pain you can imagine |

2.41/10 | The prevalence of pain felt outside of dialysis was 82.1%. 53.1% had pain severity scores between 0-2.5/10, 37.5% had scores 2.6-5/10, 9.3% had scores 5.1-7.5/10, and 0% had scores 7.6-10/10. |

| Saffari et al53 | Iran | Prevalent HD | 362 | 58 | Pain as measured by the EQ-5D-3L, duration not specified | 1-3 VRS | 1 = No pain/ discomfort 3 = Severe pain/ discomfort | N/A | Prevalence of pain/discomfort was 47.8%. |

| Sanchez et al54 | Spain | Prevalent HD | 47 | 62 | Pain as measured by the EQ-5D-3L, duration not specified | 1-3 VRS | 1 = No pain/ discomfort 3 = Severe pain/ discomfort | N/A | Prevalence of moderate pain/discomfort was 62%. Prevalence of severe pain/discomfort was 5%. |

| Senanayake et al75 | Sri Lanka | CKD G1-4 (GFRm > 15) CKD G5ND (CKM) Prevalent HD |

1174 G1-3: 259 G4: 629 G5ND CKM: 153 HD: 38 |

58 | Pain in the last 7 days as measured by the CKD Symptom Index—Sri Lanka | 1-5 VRS | 1 = Very mild 5 = Very severe |

N/A | The overall prevalence of bone/joint pain was 87.6%. Of those that experienced bone/joint pain 52.1% had moderate pain (3/5), 18.7% had severe pain (4/5), and 4.8% had very severe pain (5/5). Prevalence of bone/joint pain in CKD G1-3 was 85.7%, 87.4% in G4, 91% for G5ND CKM, and 97.4% for HD. |

| Sheshadri et al76 | United States | Prevalent HD | 48 | Median Age: 57 (52,65) | Pain in the last 7 days as measured by the Dialysis Symptom Index | 1-5 VRS | 1 = Not at all 5 = Very much |

N/A | The prevalence of muscle soreness was 21% and the prevalence of bone/joint pain was 44%. |

| Surendra et al81 | Malaysia | Prevalent HD or PD | 141 HD: 77 PD: 64 |

54 HD: 54 PD: 54 |

Current pain measured by the EQ-5D-3L | 1-3 VRS | 1 = No pain/ discomfort 3 = Severe pain/ discomfort |

N/A | The prevalence of pain/discomfort was 32.5% of patients treated with HD and 35.9% of patients treated with PD. The overall pain prevalence was 34%. |

| Thong et al77

(NECOSAD-2) |

Netherlands | Prevalent HD or PD | 1553 HD: 1010 PD: 543 |

HD: 63 PD: 53 |

Pain in last 4 weeks as measured by the Kidney Disease and Quality of Life Short Form | 1-5 VRS | 1 = Not bothered at all 5 = Extremely bothered |

N/A | Prevalence of muscle pain was approximately 71%. ~35% of patients were somewhat bothered (2/5), ~19% were moderately bothered (3/5), ~12% were very much bothered (4/5), and ~5% were extremely bothered (5/5) by muscle soreness (estimated from figure). |

| Wan Zukiman et al78 | Malaysia | CKD G5ND (CKM) Prevalent Dialysis (Does not specify) |

187 Not Dialyzed: 100 Dialyzed: 87 |

Not Dialyzed: 61 Dialyzed: 58 |

Pain in the last 7 days as measured by the Dialysis Symptom Index | 0-5 VRS | 0 = Not at all bothersome 5 = Very bothersome |

N/A | The total prevalence of bone/joint pain was 36.4%. The prevalence of bone and joint pain was 38% for the not dialyzed group and 34.5% for the dialyzed group. The prevalence of mild-moderate bone/joint pain was 35% and 3% for severe bone/joint pain in the non-dialyzed group. The prevalence of mild-moderate bone/joint pain was 29.9% and 4.6% for severe bone/joint pain in the dialyzed group. The total prevalence of muscle soreness was 32.1%. The prevalence of muscle soreness was 37% for the not dialyzed group and 26.4% for the dialyzed group. The prevalence of mild-moderate muscle soreness was 37.0% and 0% for severe muscle soreness in the non-dialyzed group. The prevalence of mild-moderate muscle soreness was 25.3% and 1.1% for severe muscle soreness in the dialyzed group. |

| Weisbord et al7 | United States | Prevalent HD | 162 | 62 | Pain in the last 7 days as measured by the Dialysis Symptom Index | 1-5 VRS | 1 = Not at all bothersome 5 = Bothers very much |

Bone/Joint Pain: 3.61/5 Muscle soreness: 3.14/5 |

Prevalence for bone/joint pain was 50% and the prevalence of muscle soreness was 28%. |

| Weisbord et al14 | United States | Prevalent HD | 75 | 59 | Pain in the last 7 days as measured by the Dialysis Symptom Index | 1-5 VRS | 1 = Not at all bothersome 5 = Bothers very much |

Bone/Joint Pain: 3.2/5 Muscle Soreness: 2.6/5 |

Prevalence of bone/joint pain was 37% and the prevalence of muscle soreness was 29%. |

| Weisbord et al79 | United States and Italy | Prevalent HD | Italian Patients: 61 | 63 | Pain in the last 7 days as measured by the Dialysis Symptom Index | 1-5 VRS | 1 = Not at all bothersome 5 = Bothers very much |

Median Score Bone/Joint Pain: 3/5 Muscle Soreness: 1/5 |

United States patient group data reported in Weisbord (Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology) 2007 article. Prevalence for bone/joint pain was 64% and 48% for muscle soreness in the Italian patient group. |

| Weisbord et al55 | United States | Prevalent HD | 286 | Median Age = 64 [56-73] | Pain measured by the Short-form McGill Pain Questionnaire, duration not specified | 0-3 VRS | 0 = None 1 = Mild 2 = Moderate 3 = Severe |

N/A | Prevalence of pain reported on at least one assessment was 71.3% and 13.3% reported pain on ≥75% of assessments. Of those reporting pain, 30% reported mild pain, 37% moderate pain, and 33% severe pain. Prevalence of severe pain at baseline was 35%. |

| Weiss et al56 | Germany | Prevalent HD | 860 | 68 | Pain in the past 6 weeks | 1-5 VRS | 1 = Not at all 5 = A lot |

N/A | Prevalence of pain was 85.5%. Prevalence of moderate to severe pain was 48.6%. |

| Wu et al57 | United States | CKD G3-5ND (GFR < 60, Pre-dialysis) |

308 | No Pain: 66 Mild Pain: 67 Severe Pain: 65 |

Pain lasting weeks, months, or even years measured by Wong-Baker Faces Pain Rating Scale | 0-10 VRS | 0 = No hurt 10 = Hurts worst |

N/A | Prevalence of chronic pain was 60.7%. Prevalence of mild chronic pain 31.5%. Prevalence of severe chronic pain was 29.2%. |

| Yong et al58 | China | CKD G5ND (CKM) Prevalent HD or PD |

179 HD: 107 PD: 27 G5ND CKM: 45 |

62 | Pain as measured by the Brief Pain Inventory, duration not specified | 0-10 NRS | 0 = Nil 10 = Extreme |

Total: 4.1/10 Dialysis: 4.1/10 G5ND CKM: 4.2/10 |

Prevalence of pain in total study cohort was 40.8%; 38% in the dialysis group (HD and PD combined) and 48.9% in the G5ND CKM group. Neither pain prevalence nor severity differed statistically between patient groups. |

| Yu et al59 | Taiwan | Prevalent HD | 117 | 52 | Pain in the past 7 days as measured by the Somatic Symptoms Disturbance Scale | 0-3 VRS | 0 = Absent 3 = Severe |

Joint Pain: 1.30/3 | Prevalence of joint pain was 36.8%. |

| Zuo et al80 | Malaysia | CKD G5ND (CKM) Prevalent Dialysis (Does not specify) |

187 Not Dialyzed: 100 Dialyzed: 87 |

Not Dialyzed: 61 Dialyzed: 58 |

Pain in the last 7 days as measured by the Dialysis Symptom Index | 0-5 VRS | 0 = Not at all bothersome 5 = Very bothersome |

N/A | The total prevalence of bone/joint pain was 36.4%. The prevalence of bone and joint pain was 38% for the not dialyzed group and 34.5% for the dialyzed group. The prevalence of mild-moderate bone/joint pain was 35% and 3% for severe bone/joint pain in the non-dialyzed group. The prevalence of mild-moderate bone/joint pain was 29.9% and 4.6% for severe bone/joint pain in the dialyzed group. The total prevalence of muscle soreness was 32.1%. The prevalence of muscle soreness was 37% for the not dialyzed group and 26.4% for the dialyzed group. The prevalence of mild-moderate muscle soreness was 37.0% and 0% for severe muscle soreness in the non-dialyzed group. The prevalence of mild-moderate muscle soreness was 25.3% and 1.1% for severe muscle soreness in the dialyzed group. |

Note. CKD = chronic kidney disease; HD = hemodialysis; PD = peritoneal dialysis; VRS = verbal rating scale; G4 = glomerular filtration rate category G4; G5ND = glomerular filtration rate category G5 not treated with maintenance dialysis; NRS = numerical rating scale; N/A = not available; CKM = conservative kidney management; VAS = visual analogue scale; VDS = verbal descriptive scale; FMS = fibromyalgia syndrome; HDF = hemodiafiltration; GFR = glomerular filtration rate; G1 = glomerular filtration rate category G1; G2 = glomerular filtration rate category G2; G3 = glomerular filtration rate category G3; NECOSAD = Netherlands Cooperative Study on the Adequacy if Dialysis.

Sample sizes varied widely from 21 to 1553 patients. Five studies31,33,46,80,83 used a yes/no categorization to determine presence of pain, one created a 28-point survey which included a pain question but was not validated,68 one study50 used a 10-point rating scale without further description, and one82 study referenced a data collection sheet without further description. Of the remaining 60 studies, there was tremendous variability in the tools and severity rating scales used. A summary of the pain assessment tools used for reporting of pain prevalence and severity is presented in Table 3. Fifty-four studies used 1 of 23 different multidimensional or multi-symptom assessment tools. Most importantly, these tools used 11 different severity scales that started at either 0 or 1 with a range to 3, 4, 5, 6, 10, or 100. These scales were the NRS, the visual analogue scale (VAS), or the verbal rating scale (VRS). The VRS uses a Likert scale to ask respondents to select the verbal descriptor (eg, “mild,” “moderate,” “severe,” or “overwhelming”) that best reflects the severity of pain. A VAS consists of a horizontal line, usually 10 cm (or 100 mm) in length that is anchored with verbal descriptors. The NRS is a segmented version of the VAS in which a respondent selects a whole number that best reflects the intensity of pain, usually rated 0 for no pain to 10 for the most severe pain. Most studies characterized pain as mild when rated 1 to 3/10, moderate pain was usually defined as 4 to 6/10, and severe as 7 to 10/10. Two additional studies used a multidimensional tool with either binary yes/no or undefined responses. Fourteen studies used 1 of 7 different single-item unidimensional tools. Only 36 (53%) studies reported the prevalence of moderate and/or severe pain.2,3,8,19,25-27,29,30,32,36-42,44,45,47,48,51,52,54-57,65,67,69,72-74,77,78,84 Nine of these studies also reported mean or median severity scores.2,3,8,26,36,41,52,67,69 An additional 14 studies reported mean or median severity scores for their study cohort but without separate prevalence rates for mild, moderate, or severe pain.7,14,24,28,34,35,43,50,58-60,62,63,79

Table 3.

Summary of Pain Assessment Tools Used for the Reporting of Pain Prevalence and Severity.

| Tool | Severity scale | Study |

|---|---|---|

| Multidimensional or Multi-Symptom Assessment Tools | ||

| 36-Item Short Form Health Survey | 1-6 VRS | 27 |

| Brief Pain Inventory | 0-10 NRS | 36,40,52,58 |

| 10 cm VAS | 67 | |

| Chronic Kidney Disease Dialysis Symptom Burden Index (adapted from the Dialysis Symptom Index) | 0-10 NRS | 24 |

| Chronic Kidney Disease Symptom Index | 1-5 VRS | 75 |

| Dialysis Discontinuation Quality of Death | 1-5 VRS (this scale was reversed) | 19 |

| Dialysis Frequency, Severity, and Symptom Burden Index (adapted from the Dialysis Symptom Index) | 1-10 NRS | 35 |

| Dialysis Symptom Index | 1-5 VRS | 7,14,28,32,60,62,76,78,79 |

| 0-4 VRS | 34 | |

| Dialysis Symptom Index—Korean Version | 0-4 VRS | 63 |

| Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale: renal | 0-10 NRS | 2,3 |

| EQ-5D-3L | 1-3 VRS | 53,54,81 |

| Kidney Disease and Quality of Life | 1-6 VRS | 84 |

| Kidney Disease and Quality of Life Short Form | 1-5 VRS | 25,26,37,49,65,69,77 |

| Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale Short Form (with additional 7 renal symptom appended to end of survey) | 0-5 VRS | 47,48 |

| Palliative Outcome Symptom Scale—Renal | 0-4 VRS | 71 |

| Patient Outcome Scale Symptom Module (renal version) | 1-5 VRS | 30 |

| 0-4 VRS | 44,51,74 | |

| Short Form 36 | 0-100 NRS (this scale was reversed) | 72 |

| Short Form McGill Pain Questionnaire | 0-3 VRS | 5,55,61 |

| 10 cm VAS | 41 | |

| 0-5 VRS | 39,45 | |

| Somatic Symptom Distress Scale (adapted from the Dialysis Symptom Index) | 0-3 VRS | 59 |

| Spanish Pain Questionnaire | 10 cm VAS | 70 |

| Unnamed 11-Item Symptom Measure (created for the study but used a validated severity scale) | 1-5 VRS | 43 |

| Unnamed 28-Item Symptom Measure | 1-5 VRS | 68 |

| Unnamed Y/N Demographic Questionnaire | Binary | 80 |

| Unnamed Data Collection Sheet | Unknown | 82 |

| Unidimensional, Single Item Pain Scales | ||

| 0-10 VDSa | 29 | |

| 1-5 VRS | 56 | |

| 10 cm VAS | 8,38,64,66 | |

| 10 Point Rating Scale | 50 | |

| 100 mm VAS | 42,73 | |

| Wong-Baker FACES Pain Rating Scale, 0-10 Likert Scale | 57 | |

| Binary Yes/No | 31,33,46,83 | |

Note. VRS = verbal rating scale; NRS = numerical rating scale; VAS = visual analogue scale; VDS = verbal descriptive scale.

The VDS is a combination of a NRS and a VRS in that each numbers has a verbal descriptor (eg, no pain, slight pain, mild pain, moderate pain, severe pain, very severe pain, the most intense pain imaginable).

There was variation and often a lack of detail regarding what constituted chronic pain. Three studies defined chronic pain as pain experienced outside of the dialysis sessions.35,41,52 Two studies defined pain at the withdrawal of dialysis, or in the last 24 hours of life following the withdrawal of dialysis.19,33 Other definitions of chronic pain ranged from pain in the past 24 hours in 1 study,67 a duration of pain of 3 days in 1 study,74 7 days in 20 studies,3,7,14,28,30,32,34,44,47,48,59,60,62,63,70,71,75,76,78,79 2 weeks in 1 study,50 4 weeks in 12 studies,8,25-27,37,49,65,68,69,72,77,84 6 weeks in 1 study,56 3 months in 11 studies,29,31,36,38-40,42,45,64,73,83 and “lasting weeks, months, or even years” in 1 study.57 Fifteen studies did not specify a duration, despite the intent to understand chronic pain burden.2,5,24,43,46,51,53-55,58,61,66,80-82 Further details of the quality assessment for each included study are presented in Supplemental Table S2.

Prevalence and Severity of Pain

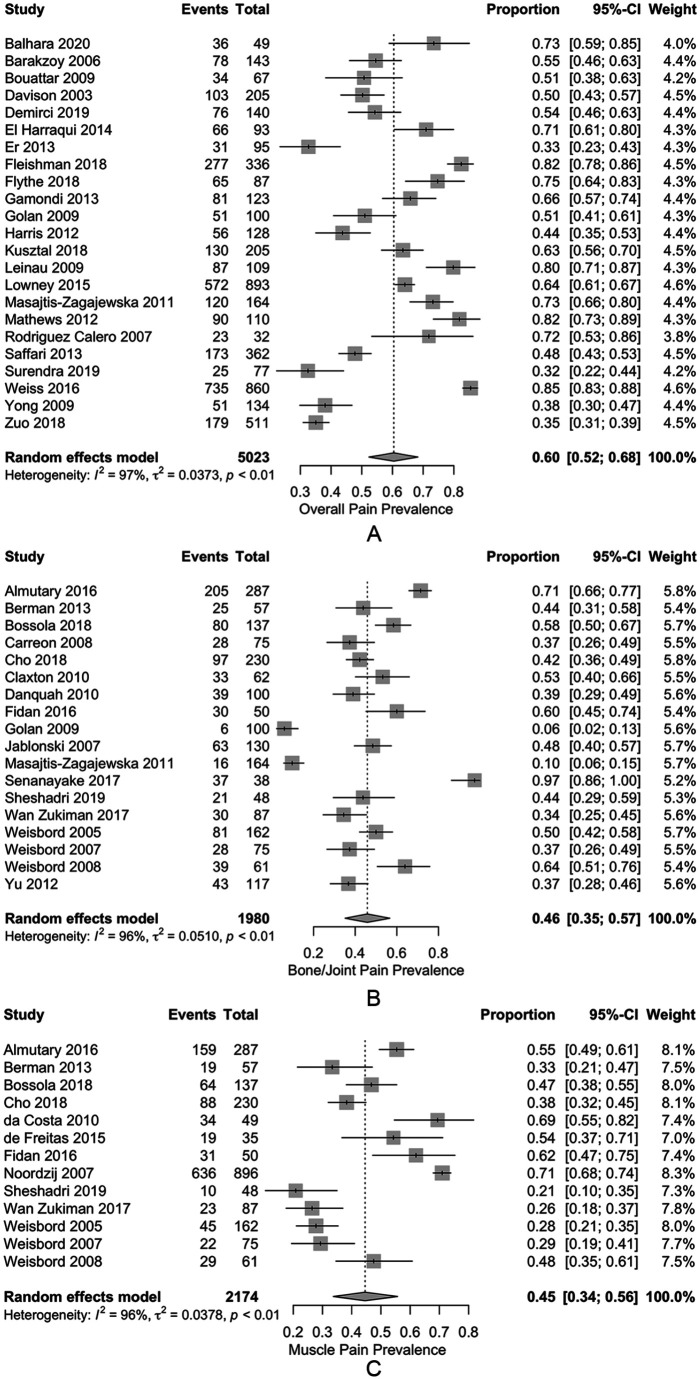

Tables 4 and 5 outline the estimated pooled prevalence of pain, and weighted mean severity of pain, for various CKD cohorts. Across the studies reporting overall pain in patients on HD, the estimated pooled prevalence was 60.5% (52.3%-68.3%) (Figure 2A). The estimated pooled prevalence of moderate or severe overall chronic pain was 43.6% (34.8%-52.7%), and the estimated pooled prevalence of severe overall chronic pain was 21.1% (12.2%-31.6%). Chronic bone/joint pain and muscle pain in patients on HD were also common with estimated pooled prevalence rates of 45.8% (35.2%-54.5%) and 44.6% (33.7%-55.7%), respectively (Figure 2B and 2C). In all cases heterogeneity was extremely high (ie, I2 > 95%). For those reporting pain, the mean severity score was 6.4 (3.7-9.0) out of 10 for overall pain, 5.9 (3.4-8.3) for bone/joint pain, and 5.3 (3.3-7.4) for muscle pain. For studies reporting median pain scores, severity of overall, bone/joint, and muscle pain were reported as 5.8, 6.0, and 2.0 out of 10, respectively. Median scores could not be adjusted for the removal of patients not experiencing pain, as such these should be interpreted with caution.

Table 4.

Pain Prevalence by CKD Cohort.

| CKD cohort | Measure | Studies | Pooled prevalence (95% CI) | I 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dialysis | ||||

| HD | Pain5,8,29,36,38-41,44-46,52,53,56,58,61,67,68,73,80,81,83,84 | 23 | 60.5% (52.3%-68.3%) | 96.9% |

| Moderate to Severe8,29,36,38-41,44,45,52,54,56,67,72,73,84 | 16 | 43.6% (34.8%-52.7%) | 96.2% | |

| Severe8,29,38,40,41,44,45,51,52,54,55,67,73,84 | 14 | 21.1% (12.2%-31.6%) | 96.9% | |

| Musculoskeletal Pain8,40,45,70,73,82 | 6 | 30.6% (17.1%-46.0%) | 95.2% | |

| Bone or Joint Pain7,14,24,28,32,34,35,40,43,45,59,62,63,66,75,76,78,79 | 18 | 45.8% (35.2%-54.5%) | 95.7% | |

| Moderate to Severe32 | 1 | 26.7% (17.2%-37.3%) | N/A | |

| Severe32,78 | 2 | 8.4% (1.8%-18.8%) | 73.6% | |

| Muscle Soreness7,14,24,28,37,49,62,63,65,66,76,78,79 | 13 | 44.6% (33.7%-55.7%) | 95.6% | |

| Moderate to Severe37,65 | 2 | 29.4% (18.6%-41.3%) | 23.6% | |

| Severe37,65,78 | 3 | 9.0% (0.2%-26.0%) | 87.9% | |

| Neuropathic Pain8,40,70 | 3 | 9.6% (1.1%-24.2%) | 93.0% | |

| HD or PD | Pain2,71 | 2 | 68.3% (56.6%-78.9%) | 69.5% |

| Moderate to Severe2,3 | 2 | 40.5% (27.4%-54.3%) | 95.4% | |

| Bone or Joint Pain60 | 1 | 38.9% (29.0%-49.2%) | N/A | |

| Muscle Soreness25,26,60,69,77 | 5 | 65.7% (53.9%-74.8%) | 95.5% | |

| Moderate to Severe69,77 | 2 | 25.0% (17.5%-33.3%) | 92.3% | |

| Severe25,26,77 | 3 | 23.1% (15.4%-31.8%) | 89.8% | |

| PD | Pain81 | 1 | 35.9% (52.3%-68.3%) | N/A |

| Bone or Joint Pain24 | 1 | 50.0% (34.9%-65.2%) | N/A | |

| Muscle Soreness24,49 | 2 | 42.9% (7.4%-83.3%) | 96.7% | |

| Pre-Dialysis | ||||

| G3 | Pain50 | 1 | 70.8% (50.8%-87.6%) | N/A |

| G3-4 | Musculoskeletal Pain42 | 1 | 58.3% (51.2%-64.1%) | N/A |

| Moderate to Severe42 | 1 | 50.5% (43.5%-57.6%) | N/A | |

| Severe42 | 1 | 32.0% (25.6%-38.7%) | N/A | |

| G3-5ND | Pain57 | 1 | 60.7% (55.2%-66.1%) | N/A |

| Severe57 | 1 | 29.2% (24.3%-34.4%) | N/A | |

| Bone or Joint Pain60 | 1 | 33.3% (23.9%-43.5%) | N/A | |

| Muscle Soreness60 | 1 | 24.4% (16.1%-33.9%) | N/A | |

| G4 | Bone or Joint Pain24 | 1 | 30.4% (20.1%-41.9%) | N/A |

| Muscle Soreness24 | 1 | 36.2% (25.2%-48.0%) | N/A | |

| G4-5ND | Pain50,71 | 2 | 61.8% (36.8%-84.1%) | 78.9% |

| Moderate to Severe72 | 1 | 28.4% (19.0%-38.8%) | N/A | |

| Musculoskeletal Pain31 | 1 | 37.7% (35.0%-40.5%) | N/A | |

| G5ND | Musculoskeletal Pain42 | 1 | 52.2% (31.5%-72.5%) | N/A |

| Moderate to Severe42 | 1 | 43.5% (26.7%-64.4%) | N/A | |

| Severe42 | 1 | 43.5% (26.7%-64.4%) | N/A | |

| Bone or Joint Pain24,78 | 2 | 39.1% (31.0%-47.5%) | 0.0% | |

| Severe78 | 1 | 3.0% (0.4%-7.5%) | N/A | |

| Muscle Soreness24,78 | 2 | 29.9% (15.9%-46.1%) | 68.8% | |

| Severe78 | 1 | 0.0% (0.0%-1.7%) | N/A | |

| Post-Dialysis | ||||

| At withdrawal | Pain33 | 1 | 54.6% (37.3%-71.3%) | N/A |

| 24 hours prior to death | Pain19,33 | 2 | 32.6% (15.1%-52.8%) | 74.7% |

| Severe19 | 1 | 5.1% (1.1%-11.2%) | N/A | |

| CKM | ||||

| G4 | Bone or Joint Pain75 | 1 | 87.4% (84.7%-90.0%) | N/A |

| G4-5ND | Pain74 | 1 | 56.4% (43.0%-69.3%) | N/A |

| Moderate to Severe74 | 1 | 27.3% (16.2%-39.9%) | N/A | |

| Severe74 | 1 | 12.7% (5.0%-23.0%) | N/A | |

| G5ND | Pain27,30,47,48,58,64 | 6 | 60.4% (27.7%-88.8%) | 98.0% |

| Moderate to Severe30,47,48 | 3 | 35.0% (27.6%-42.7%) | 0.0% | |

| Severe27,30 | 2 | 27.7% (9.0%-51.5%) | 84.4% | |

| Bone or Joint Pain47,48,75 | 3 | 70.7% (41.4%-92.9%) | 95.3% | |

| Moderate to Severe47,48 | 2 | 13.0% (7.3%-19.9%) | 0.0% | |

| Muscle Soreness47,48 | 2 | 39.1% (21.8%-57.8%) | 75.4% | |

| Moderate to Severe47,48 | 2 | 3.3% (0.1%-9.1%) | 37.8% | |

Note. CKD = chronic kidney disease; CI = confidence interval; HD = hemodialysis; PD = peritoneal dialysis; CKM = conservative kidney management; G3 = glomerular filtration rate category G3; G4 = glomerular filtration rate category G4; G5ND = glomerular filtration rate category G5 not treated with maintenance dialysis.

Table 5.

Pain Severity Synthesis by CKD Cohort.

| CKD cohort | Measure | Studies | Weighted mean severity (95% CI) | Studies | Median severitya |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dialysis | |||||

| HD | Pain8,36,41,52,58,67 | 5 | 6.38 (3.72-9.04) | 1 | 5.8 |

| Bone or Joint Pain7,14,24,28,34,35,43,59,62,63,79 | 10 | 5.88 (3.42-8.34) | 1 | 6.0 | |

| Muscle Soreness7,14,24,28,62,63,79 | 6 | 5.34 (3.29-7.39) | 1 | 2.0 | |

| HD and PD | Pain2,3 | 2 | 4.39 (2.75-6.03) | ||

| Bone or Joint Pain60 | 1 | 5.0 | |||

| Muscle Soreness26,60,69 | 2 | 5.02 (4.59-5.45) | 1 | 4.0 | |

| PD | Bone or Joint Pain24 | 1 | 3.15 (2.18-4.12) | ||

| Muscle Soreness24 | 1 | 2.67 (2.24-3.10) | |||

| Pre-Dialysis | |||||

| G3 | Pain50 | 1 | 5.40 (4.48-6.32) | ||

| G3-5ND | Bone or Joint Pain60 | 1 | 6.0 | ||

| Muscle Soreness60 | 1 | 4.0 | |||

| G4 | Bone or Joint Pain24 | 1 | 3.48 (3.06-3.90) | ||

| Muscle Soreness24 | 1 | 2.36 (2.07-2.66) | |||

| G4-5ND | Pain50 | 1 | 5.70 (4.80-6.60) | ||

| G5ND | Bone or Joint Pain24 | 1 | 2.69 (2.23-3.15) | ||

| Muscle Soreness24 | 1 | 2.75 (2.31-3.19) | |||

| CKM | |||||

| G5ND | Pain58 | 1 | 4.20 (3.50-4.90) | ||

Note. CKD = chronic kidney disease; CI = confidence interval; HD = hemodialysis; PD = peritoneal dialysis; G3 = glomerular filtration rate category G3; G4 = glomerular filtration rate category G4; G5ND = glomerular filtration rate category G5 not treated with maintenance dialysis; CKM = conservative kidney management.

Median severity may include patients who reported no pain.

Figure 2.

Forest plot of pooled prevalence estimates for (A) overall chronic pain, (B) bone/joint pain, and (C) muscle pain for patients on hemodialysis.

Note. Random effects model with 95% CIs plotted, double arcsine transformation used. CI = confidence interval.

Pain prevalence rates and severity scores were similar across the other CKD cohorts. For patients on either HD or PD, the estimated pooled prevalence of overall pain was 68.3% (56.6%-78.9%), moderate to severe overall pain 40.5% (27.4%-54.3%), bone/joint pain 38.9% (29.0%-49.2%), and muscle pain 65.7% (53.9%-74.8%). Severe overall pain was not reported for this group. Heterogeneity in all groups was extremely high except for the overall pain measurement, where heterogeneity was moderate (I2 = 69.5%). Patients on PD had prevalence estimates for overall pain, bone/joint pain, and muscle pain of 35.9% (52.3%-68.3%), 50.0% (34.9%-65.2%), and 42.9% (7.4%-83.3%), respectively, although only 3 studies provided measures. Weighted mean severity scores for those reporting pain on either HD or PD were 4.4 (2.8-6.0) out of 10 for overall pain, and 5.0 (4.6-5.5) for muscle pain. Reported median severity scores for bone/joint pain and muscle pain were 5.0 and 4.0 out of 10, respectively. Peritoneal dialysis severity scores for bone/joint pain and muscle pain were reported as 3.2 (2.2-4.1) and 2.7 (2.2-3.1) out of 10, respectively.

Overall pain prevalence remained high in patients following withdrawal from dialysis (54.6%; 37.3%-71.3%), even in the last 24 hours of life (32.6%; 15.1%-52.8%). For patients with G4-5 CKD not on dialysis, the estimated pooled prevalence of overall pain and moderate to severe pain was 56.4% (43.0%-69.3%) and 27.3% (16.2%-39.9%), respectively. Cohorts specifying only G5 CKD patients managed conservatively had higher estimated pooled prevalence of overall pain and moderate to severe pain at 60.4% (27.7%-88.8%) and 35.0% (27.6%-42.7%), respectively. Heterogeneity was extremely high for overall pain reporting, but negligible in the studies reporting moderate to severe pain (I2 = 0%). The reported mean severity for these patients was 4.2 (3.5-4.9) out of 10.

Data were limited for the prevalence of pain in patients with earlier stages of CKD. While there was some variability in the reported prevalences, the combining of CKD G category in some studies and separation in others made the data difficult to interpret. In one small study, there were no statistically or clinically significant differences in mean overall pain severity scores between CKD G3 and G4-5, which ranged from 5.4 to 5.7 out of 10.50

Meta-regressions were completed for pain prevalence in HD patients reporting overall pain, moderate to severe and severe overall pain, bone/joint pain, and muscle pain. No evidence was found for a publication bias in any of the above measures (P = .61, .89, .64, .62, and .10, respectively).

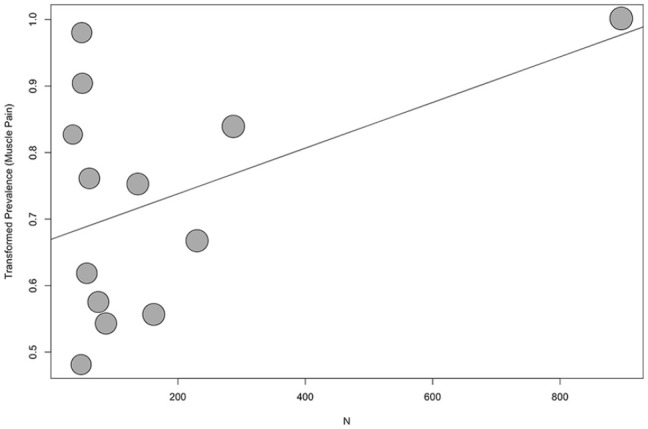

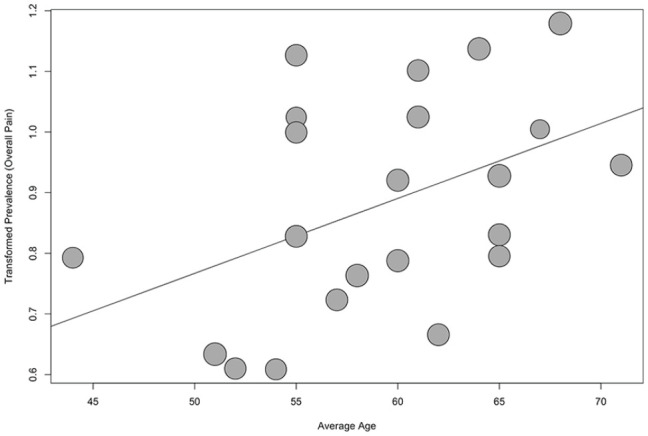

None of the meta-regressions returned evidence suggesting a difference in prevalence by either publication year or scale type. While there was evidence that muscle pain prevalence increased with larger sample sizes (P = .03), this appears to be the result of one very large sample49 influencing results (Figure 3). There was also evidence that overall pain prevalence reports increase with cohort average age (P = .02, Figure 4). In both cases, heterogeneity was only marginally reduced (I2 = 86.7% and 94.4%, respectively).

Figure 3.

Bubble plot of transformed prevalence of muscle pain against sample size for patients on hemodialysis.

Note. Regression line plotted (P = .03).

Figure 4.

Bubble plot of transformed prevalence of overall pain against average age for patients on hemodialysis.

Note. Regression line plotted (P = .02), one study omitted due to missing age reporting.

There was strong evidence to suggest an effect of both country and pain definition on bone/joint pain as well as muscle pain (P < .001 in all cases). Supplemental Figures S1-S4 illustrate the model results in stratified forest plots. Stratifying by country significantly reduced heterogeneity in both cases: residual I2 was 15.3% in bone/joint pain prevalence and approximately 0% in muscle pain prevalence. In both groups, there was a small cluster of Italian studies with negligible heterogeneity (I2 = 0% in both cases), at or above the ungrouped estimated pooled prevalence estimates (stratified estimates for bone/joint pain were 60.1% [53.2%-66.8%] and 47.0% [40.0%-54.0%] for muscle pain), and a larger cluster of studies out of the United States with negligible or low heterogeneity (I2 = 0% and 21.6%, respectively), estimating stratified pooled prevalence at or below the ungrouped estimates (44.6% [40.4%-48.8%] for bone/joint pain and 27.9% [23.3%-32.9%] for muscle pain). One additional cluster of 2 studies out of Brazil was present in the muscle pain model, which had a high estimated pooled prevalence and moderate heterogeneity (62.7% [47.5%-76.7%], I2 = 48.5%). The remaining countries (Malaysia, Netherlands, Saudi Arabia, South Korea, Turkey, Poland, Israel, Sri Lanka, and Taiwan) were present in one or both of the models, each with only one study and large variations of reported prevalence, with ranges of 6.0% to 97.4% for bone/joint pain and 26.4% to 71.0% for muscle pain.

When stratified by pain definition, bone/joint pain prevalence heterogeneity improved marginally, but remained high (residual I2 = 87.8). Groups included pain lasting more than 3 months, pain lasting 7 days, pain between dialysis, and no definition. The 3-month group had significantly lower scores than the rest, with an estimated pooled prevalence of 8.2% (5.0%-12.0%) and had low heterogeneity (I2 = 6.3%). Both the 7-day group and the no definition group had high pooled prevalence estimates and high heterogeneity (50.2% [41.5%-58.9%] with I2 = 88.2%, and 60.4% [44.0%-75.7%] with I2 = 90.2%, respectively). The between dialysis group only contained one study (with a reported prevalence of 39.0%). Stratification of muscle pain prevalence by pain definition only decreased heterogeneity to a moderate level (residual I2 = 66.8%). Three clusters of pain definitions in the model were pain lasting 4 weeks, pain lasting 7 days, and no definition. The stratified pooled prevalence estimates for each group were 67.6% (58.8%-75.8%), 33.9% (27.7%-40.4%), and 56.4% (51.0%-61.7%), with subgroup heterogeneity scores of I2 = 52.4%, 72.2%, and 0%, respectively.

Discussion

This systematic review contributes to the overall aim to address gaps in current knowledge around effective approaches to the evaluation and management of chronic pain for patients with CKD. The findings illustrate that chronic pain is extremely common and often severe across diverse CKD populations. Most patients who report pain rate their pain as either moderate (typically defined as 4-6 out of 10) or severe (7-10 out of 10) in severity. Data on PD patients and those cared for conservatively without dialysis are more limited, as are studies involving patients with CKD G3-5 not yet requiring renal replacement therapy, although the pain prevalence rates appear similar. The lowest reported prevalence of severe pain was in patients managed conservatively; this finding may reflect active pain management in CKM. Prevalence rates in patients with earlier stages of CKD were also high and did not appear to change with the severity of their CKD. This may reflect the fact that much of the pain in CKD is associated with the burden of comorbidity.

A recent qualitative systematic review explored prevalence and severity of pain in HD patients.85 The 2 distinct syndromes of acute and chronic pain were synthesized together and no quantitative analyses or meta-analyses were conducted. However, the main message of the review that pain is common in patients with CKD and is typically perceived as moderate or severe in intensity is consistent with our results.

These findings have clinical implications, particularly given that symptom management is a top priority for patients with CKD.10 Routine screening for pain in all patients with CKD should be integrated into nephrology care. This is consistent with KDIGO recommendations that state “Symptom assessment and management is an integral component of quality care for patients with advanced CKD.” Regular global symptom screening using validated tools such as the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System-revised: Renal (ESAS-r: Renal) and Palliative Care Outcome Scale-Renal (POS-renal) should be incorporated into routine clinical practice.86 This systematic review suggests that routine symptom assessment should extend to patients with earlier GFR categories of CKD as well. The ESAS-r:Renal3,9,87 and the POS-renal74,88 are simple assessment tools that screen for several common symptoms experienced by patients with CKD. Both tools have been translated into several languages, are appropriate for screening patients even when they are pre-terminal, and perhaps, most importantly, provide the opportunity to redirect care toward a more patient-centered model. More comprehensive pain assessment tools with evidence for validity in patients with CKD are also available.11 The VAS, VRS, and the NRS are all valid, reliable, and appropriate for use in clinical practice, although the VAS tends to be more difficult to use than the other two.89 The NRS is often recommended as it has good sensitivity and generates data that can be more easily analyzed for research and audit purposes.89

Many health care providers have limited expertise and feel unprepared to pursue effective treatment options for chronic pain. Some feel that it is not their responsibility to treat symptoms that are not directly related to CKD or dialysis and are therefore reluctant to prescribe and monitor analgesics.90 Many of these barriers result from inadequate training in the basic principles of palliative care such as symptom and pain management. Several surveys of renal fellows reported that they receive little education in palliative and end-of-life care; only 44% of fellows in 2013 reported being explicitly taught how to treat dialysis patients’ pain91 (although this was an increase from 30% in 2003)92 and only 9.4% felt very comfortable treating pain in patients with advanced CKD.93 However, nearly all the fellows thought that it was important to receive education on appropriate palliative care. Enhanced education in pain management will be required to address the burden of pain experienced by patients with CKD.86

These findings also have research implications. Developing and evaluating the relative effectiveness of pain management strategies should be assessed with particular attention to the impact on patient outcomes such as overall symptom burden, physical function, and HRQL. Most treatment recommendations have been extrapolated from treatments used successfully in the general population, with special considerations made for the selection of various analgesics based on their different pharmacokinetic properties in renal failure. In addition, future studies should be more inclusive across CKD G3-5 populations and renal replacement modalities, including patients cared for with CKM, to ensure appropriate strategies are in place for the monitoring and management of pain for all patients in need.

Several limitations of the studies included in this review were identified. If these limitations are not addressed in future studies, this will introduce bias, limit our ability to interpret the data, and ultimately compromise our ability to improve pain management. First, studies lacked a consistent approach to determining or reporting the chronicity of pain. Dialysis patients also experience recurring episodes of acute pain such as intra-dialytic headaches and cramps. This acute pain is often associated with tissue damage but typically has no progressive pattern, lasts a predictable period, subsides as healing occurs, and is episodic with periods of no pain. In contrast, chronic pain is more likely to result in functional impairment and disability, psychological distress (eg, anxiety or depression), sleep deprivation, disruption of activities of daily living, and poor HRQL as it is present for long periods of time and is often out of proportion with the extent of pain from the originating injury. Chronic pain is most commonly defined as any painful condition that persists for greater than 3 months.94 Studies that report pain should make a clear and consistent distinction between these 2 different pain syndromes. Given the variability in the reporting and defining of chronic pain in these studies, patients with acute pain may also have been included, falsely elevating the prevalence rates of true chronic pain.

There was also variability in the measures used to determine pain severity that differed in range and format (including numerical, visual, or verbal scales). Hence, a recalibration of different scales was required to compare different studies which may have introduced bias in the results of the meta-analysis. While each of these approaches has evidence for validity, they may be interpreted differently by patients, limiting the ability to compare findings across populations. There are data around what constitutes clinically significant pain and what constitutes clinically important differences in pain relief based on 0 to 10 scales and the consensus recommendation from the Initiative on Methods, Measurement, and Pain Assessment in Clinical Trials (IMMPACT) to use a 0 to 10 NRS in pain studies.95

Substantial variability in the reported prevalence of pain was present in nearly all of the pooled groups, yielding very high heterogeneity measurements. As such the estimates should be interpreted with caution and may not reflect the true prevalence of pain. However, stratification by country and pain definition in some cases decreased the I2 substantially, which suggests that at least some of this variability may be explained by regional practices and differences in what constitutes chronic pain.

Another limitation was that these studies reported mean severity scores for the entire cohort. The reporting of average severity scores is problematic as the distribution of pain tends to be “U-shaped” rather than bell shaped. This highly skewed distribution has the maximum frequencies at the 2 extremes of the range of variables, ie, patients with no pain and patients with severe pain, or patients having good pain relief or poor pain relief. If few patients are “average,” the use of average values is misleading. To better understand patterns of pain, it is important to determine the prevalence of clinically significant pain (such as moderate and severe pain) and for those with pain to report its severity. Finally, we did not reach out to primary authors for additional information. Recommendations for future studies that explore pain prevalence and severity are outlined in Table 6 and are in keeping with international recommendations for the reporting of pain in clinical studies.