Abstract

Background

The study aimed to clarify the efficacy of the “3‐Day Surprise Question (3DSQ)” in predicting the prognosis for advanced cancer patients with impending death.

Patients and Methods

This study was a part of multicenter prospective observational study which investigated the dying process in advanced cancer patients in Japan. For patients with a Palliative Performance Scale ≤20, the 3DSQ “Would I be surprised if this patient died in the next 3 days?” was answered by their physicians. In addition to the sensitivity and specificity of the 3DSQ, the characteristics of patients who survived longer than expected were examined via multivariate analysis.

Results

Among the 1896 patients enrolled, 1411 were evaluated. Among 1179 (83.6%) patients who were classified into the “Not surprised” group, 636 patients died within 3 days. Among 232 (16.4%) patients of “Yes surprised” group, 194 patients lived longer than 3 days. The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value of the 3DSQ were 94.3% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 92.7% to 95.8%), 26.3% (95% CI: 24.8% to 27.6%), 53.9% (95% CI: 53.0% to 54.7%), and 83.6% (95% CI: 78.7% to 87.7%), respectively. Multivariate analysis showed palpable radial artery, absent respiration with mandibular movement, SpO2 ≥ 90%, opioid administration, and no continuous deep sedation as characteristics of patients who lived longer than expected.

Conclusions

The 3‐Day Surprise Question can be a useful screening tool to identify advanced cancer patients with impending death.

Keywords: advanced cancer, end‐of‐life care, impending death, predict prognosis, surprise question

Survival prediction in cancer patients with impending death is important for patients, families, and physicians. The 3‐Day Surprise Question can be a useful screening tool to identify advanced cancer patients with impending death.

1. INTRODUCTION

Survival prediction in cancer patients with impending death is important for patients, families, and physicians. This sets the timeline to achieving a “good death”, where the patient's final wishes are accommodated and harmful interventions are stopped. 1 The Palliative Prognosis Score (PaP score), Palliative Prognostic Index (PPI), Prognosis in Palliative care Study predictor models (PiPS models), and Surprise Question were helpful for prognosis prediction. 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 Particularly, the Surprise Question (SQ), “Would I be surprised if this patient died in the next 12 months?,” was simple, sensitive, and specific. Thus, it was useful for predicting the prognosis of cancer patients in the next 12 months. Although these tools can predict the prognosis in a weekly, monthly, or yearly basis, a new prognostic tool is necessary to predict the prognosis patients impending death within days.

Prediction of a cancer patient's prognosis within 3 days may be helpful in accommodating the patient's final wishes while still receiving high quality end‐of‐life care. 7 Previous studies attempted to predict a cancer patient's prognosis within 3 days. Hui et al., used physical signs and showed that Cheyne–Stokes breathing, pulselessness of the radial artery, peripheral cyanosis, drooping of nasolabial folds, and Palliative Performance Scale (PPS) ≤20 were predicted the prognosis within 3 days. These physical signs had high specificity but low sensitivity for death within 3 days. 8 , 9 It is necessary to develop highly‐sensitive prognostic tools. In a previous study, Hamano et al., reported that a 7‐day surprise question, “Would I be surprised if this patient died in the next 7 days?,” and a 30‐day surprise question, “Would I be surprised if this patient died in the next 30 days?,” were highly sensitive tools for predicting prognosis at 7 and 30 days, respectively. 10 With this, we considered the 3‐Day Surprise Question (3DSQ) “Would I be surprised if this patient died in the next 3 days?” could be as a high sensitive prognostic tool as well as them.

The purpose of this study was to clarify the usefulness of the 3DSQ in predicting the prognosis for advanced cancer patients with impending death. In addition, we aimed to estimate the characteristics that led physicians to incorrectly predict that patients live longer.

2. METHODS

2.1. Participants

This study was a secondary analysis from a multicenter prospective observational study, which was conducted to uncover the dying process and end‐of‐life care in advanced cancer patients in Japan. The study was named East‐Asian collaborative cross‐cultural Study to Elucidate the Dying process (EASED). Consecutive eligible patients were enrolled if they had been newly referred to the participating Palliative Care Units (PCUs) during the study period. Observations were implemented within daily medical practice.

Adult patients (aged 18 years or older) who were diagnosed with locally extensive or metastatic cancer and admitted to PCUs were included in this study. On the contrary, patients who were scheduled for discharge within a week and refused approval were excluded from this study.

All data were prospectively recorded by physicians on a structured data‐collecting sheet made for this study which was piloted prior to study initiation.

2.2. Data collection

We analyzed the required data for our analysis from EASED.

We collected information on the patients’ characteristics at hospitalization (age, sex, primary cancer site, metastasis, complication, and medical treatment histories, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status [ECOG PS] and PPS) and treatment received during hospitalization (oxygen therapy, presence of opioid administration, sedation). In addition, we also collected the physical signs (Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale score [RASS], response to verbal stimuli, response to visual stimuli, peripheral cyanosis, pulse of radial artery, respiration with mandibular movement, bronchial secretions, and dysphagia of liquids), vital signs (body temperature, oxygen saturation of peripheral artery, and respiratory rate), and patients’ clinical symptoms (pain, dyspnea, fatigue, edema, pleural effusion, and ascites) on the first day when each patient had PPS ≤20. Patients’ clinical symptoms (pain, dyspnea, and fatigue) were evaluated by Integrated Palliative care Outcome Scale [IPOS]. The above factors were selected as representative prognostic factors, which the authors considered to be prognostic in daily clinical practice.

Physicians were asked the 3DSQ, “Would I be surprised if this patient were to die within 3 days?,” on the first day, when each patient had PPS ≤20. The physicians answered the 3DSQ with “Not surprised” or “Surprised”.

2.3. Data analysis and statistics

The patients were followed up until death. We set “day one” as the first day when each patient had PPS ≤20, and we defined "death within 3 days" as death from day 1 to day 3.

The patients were initially classified into “Not surprised” and “Surprised” groups based on the 3DSQ response of their physicians and the patient's status (alive or dead) on day 3. Moreover, sensitivity and specificity as well as positive and negative predictive values were calculated using simple statistical analysis by 2 × 2 contingency tables.

Second, to identify the factors of all patients who lived longer than 3 days contrary to the expectations of their physicians, we divided the patients into four groups. Group A consisted of patients whose physicians answered “not surprised” and actually died within 3 days. Group B (defined as “lived longer group”) were patients whose physicians answered “not surprised” and did not actually die within 3 days, Group C consisted of patients whose physicians answered “surprised” and actually died within 3 days. Lastly, Group D consisted of patients whose physicians answered “surprised” and did not actually die within 3 days. We then divided the four groups into two groups in order to analyze the data. The “lived longer group” consisted of patients whose physicians answered "not surprised" and did not actually die within 3 days. The “other group” consisted of patients whose physicians’ expectations were correct or who died earlier than expected. In other words, the "other group" is the sum of groups A, C, and D.

Third, we performed a Cochran–Armitage trend test for ordinal variables and a Fisher's exact test for categorical variables to identify the factors related to the "Lived longer group".

Fourth, to identify the factors associated with "Lived longer group," we performed a multivariate logistic regression analysis, using seven typical signs that were previously used to predict prognosis (RASS, Dyspnea, Pain, Dysphagia of liquids, Edema, Delirium, Prediction of prognosis at PPS ≤20) and signs that were significant in univariate analysis. A p value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant in this study.

Statistical analysis was performed with JMP pro version 14 for Windows (SAS). In addition, all statistical analyses were performed with the advice of the Statistics Department.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Patients’ characteristics

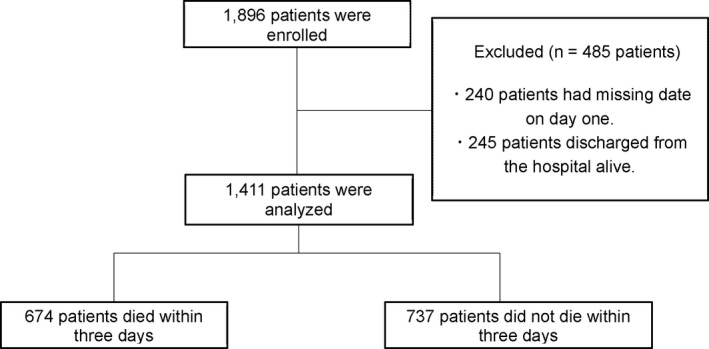

A total of 1,896 patients were enrolled from 22 PCUs in Japan from January 2017 to December 2017. The median length of hospitalization period was 16 days (range 0–375 days). The overall median survival was 17 days (range 0–375 days). A total of 485 patients were excluded because 240 patients did not have an exact date for day one and 245 patients were discharged from the hospital alive. Thus, a total of 1,411 patients were evaluated (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Patients selection for this study

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the analyzed 1411 patients. The mean [SD] age was 72.6 [12.2] (range 25–100), and 716 (50.7%) patients were male. The primary sites were more commonly found in the lungs (17.1%), upper gastrointestinal tract (14.6%), lower gastrointestinal tract (13.1%), and pancreas (10.3%). The average prognosis for patients predicted by physicians on day one was 7.2 days.

TABLE 1.

Patient's characteristics of the analyzed 1411 patients at hospitalize

| Total (n = 1411) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | No. (%) | Characteristics | No. (%) |

| Age(years), mean (SD) [range] | 72.6 (12.2) [25–100] | Comorbidity | |

| Male sex | 716 (50.7) | Cardiovascular | 82 (5.8) |

| Primary cancer site | Cerebrovascular | 112 (7.9) | |

| Lung | 242 (17.1) | Lung | 83 (5.8) |

| Stomach/Esophagus | 207 (14.67) | Diabetes mellitus | 184 (13.0) |

| Colon/Rectum | 186 (13.1) | Dementia | 125 (8.8) |

| Prostate/Bladder/Kidney/Testis | 102 (7.2) | Eastern cooperative oncology group performance status | |

| Pancreas | 146 (10.3) | ||

| Ovary/Uterus | 82 (5.8) | 0–1 | 8 (0.6) |

| Liver/Biliary system | 121 (8.5) | 2 | 79 (5.6) |

| Others | 325 (23.0) | 3 | 549 (38.9) |

| Metastatic site | 4 | 775 (54.9) | |

| Liver | 565 (40.0) | Palliative Performance Scale | |

| Bone | 380 (26.9) | 20 or less | 326 (23,1) |

| Lung | 530 (37.5) | 30 | 296 (21.0) |

| Cancer treatment | 40 | 410 (29.0) | |

| Surgery | 594 (42.0) | 50 | 281 (20.0) |

| Chemotherapy | 866 (61.3) | 60 and above | 98 (6.9) |

| Hormonal therapy | 14 (0.9) | ||

| Radiation therapy | 11 (0.7) | Prediction of prognosis (days), mean(SD) [range] | 27.1 (22.9) [0–180] |

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

Table 2 shows a 2 × 2contingency table. For 1179 (83%) of the patients, physicians answered that they would not be surprised if the patient died within 3 days. The sensitivity of the 3DSQ ‘‘not surprised” result showed a sensitivity of 94.3% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 92.7% to 95.8%) and specificity of 26.3% (95% CI: 24.8% to 27.6%). The positive predictive value was 53.9% (95% CI: 53.0% to 54.7%), the negative predictive value was 83.6% (95% CI: 78.7% to 87.7%) and the accuracy was 58.8% (95% CI: 57.2% to 60.2%).

TABLE 2.

2 × 2 contingency table

| Group | Death within 3 days | Not death within 3 days | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Not surprised | Group A; 636 | Group B; 543 | |

| Surprised | Group C; 38 | Group D; 194 | |

| Sensitivity | 94.3% (95% CI: 92.7%–95.8%) | Positive predictive value | 53.9% (95% CI: 53.0%–54.7%) |

| Specificity | 26.3% (95% CI: 24.8%–27.6%) | Negative predictive value | 83.6% (95% CI: 78.7%–87.7%) |

Group A: "Patients who physicians answered "not surprised" and actually die within three days". Group B: "Group that lived longer than expected (defined as "Lived longer group"): patients who physicians answered "not surprised" and did not actually die within three days". Group C: "Patients who physicians answered "surprised" and actually die within three days". Group D: "Patients who physicians answered "surprised" and did not actually die within three days".

Abbreviation: CI, Confidence interval.

The results of all variables for which univariate analysis was performed are shown in Table S1. Table 3 summarized 11 variables which associated with the factors related to the "Lived longer group" in Table S1. These variables included a decreased response to verbal stimuli (p = 0.001), decreased response to visual stimuli (p = 0.001), peripheral cyanosis (p = 0.004), radial artery (p < 0.001), respiration with mandibular movement (p < 0.001), increased bronchial secretions (p = 0.009), respiratory rate (p = 0.041), SpO2 (p < 0.001), opioid administration (p = 0.002), continuous deep sedation (p = 0.005), and infusion therapy (p = 0.035).

TABLE 3.

The results of univariate analysis which associated with the factors related to the "Lived longer group"

| Total (n = 1411) | Total | Lived longer group | Other group | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | n | n | % | n | % | ||

| Decreased response to verbal stimuli | No | 1172 | 477 | 40.7 | 695 | 59.3 | 0.002* |

| Yes | 224 | 66 | 29.5 | 158 | 70.5 | ||

| Decreased response to visual stimuli | No | 1012 | 420 | 41.5 | 592 | 58.5 | 0.001* |

| Yes | 384 | 123 | 32 | 261 | 68 | ||

| Peripheral cyanosis | No | 1146 | 466 | 40.7 | 680 | 59.3 | 0.004* |

| Yes | 250 | 77 | 30.8 | 173 | 69.2 | ||

| Pulselessness of radial artery | No | 1327 | 531 | 40 | 796 | 60 | <0.001* |

| Yes | 69 | 12 | 17.4 | 57 | 82.6 | ||

| Respiration with mandibular movement | No | 1346 | 540 | 40.1 | 806 | 59.89 | <0.001* |

| Yes | 50 | 3 | 6 | 47 | 94 | ||

| Increased bronchial secretions | No | 1067 | 435 | 40.8 | 632 | 59.2 | 0.009* |

| Yes | 329 | 108 | 32.8 | 221 | 67.2 | ||

| Respiratory rate | 24 times or less per minute | 1100 | 449 | 40.8 | 651 | 59.2 | 0.041* |

| 25 times or more per minute | 76 | 22 | 29 | 54 | 71 | ||

| SpO2 | 90% and above | 123 | 27 | 22 | 96 | 78 | <0.001* |

| 89% or less | 1162 | 492 | 42.2 | 674 | 57.8 | ||

| Presence of opioid administration | No | 324 | 150 | 46.3 | 174 | 53.7 | 0.002* |

| Yes | 1072 | 393 | 36.7 | 679 | 63.3 | ||

| Continuous deep sedation | No | 1349 | 534 | 39.6 | 815 | 60.4 | 0.006* |

| Yes | 47 | 9 | 19.2 | 38 | 80.8 | ||

| Infusion therapy | No | 514 | 181 | 35.2 | 333 | 64.8 | 0.035* |

| Yes | 882 | 362 | 42 | 520 | 58 | ||

A p value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Table 4 listed the results of the multivariate analysis. Five factors were reported to be independently associated with the "Lived longer group". These factors were the radial artery (palpable vs. pulselessness) (odds ratio [OR] 2.29; 95% CI: 1.13 to 4.64; p = 0.021), respiration with mandibular movement (absent vs. present) (OR 6.76; 95% CI: 2.02 to 22.50; p = 0.002), SpO2 (≥90% vs. <89%) (OR 1.93; 95% CI: 1.19 to 3.10; p = 0.007), opioid administration (present vs. absent) (OR 1.48; 95% CI: 1.08 to 2.01; p = 0.013), and continuous deep sedation (no vs. yes) (OR 2.64; 95% CI: 1.12 to 6.17; p = 0.017).

TABLE 4.

The results of multivariate analysis which associated with the factors related to the "Lived longer group"

| Variables | OR(95%CI) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Radial artery | Palpable | 2.29 (1.13–4.64) | 0.021* |

| Pulselessness | ref | ||

| Respiration with mandibular movement | Absent | 6.76 (2.02–22.5) | 0.002* |

| Present | ref | ||

| SpO2 | 90% and above | 1.93 (1.19–3.10) | 0.007* |

| 89% or less | ref | ||

| Opioid administration | Present | 1.48 (1.08–2.01) | 0.013* |

| Absent | ref | ||

| Continuous deep sedation | No | 2.64 (1.12–6.17) | 0.017* |

| Yes | ref |

Abbreviations: CI, Confidence interval; OR, Odds ratio.

A p value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

4. DISCUSSION

In this study, we showed that the 3‐Day Surprise Question was a viable screening tool in identifying advanced cancer patients impending death, especially within 3 days. Moreover, we showed five variables associated with the patients who were more likely to survive for more than 3 days, contrary to the physician's prediction. These variables were a palpable radial artery, absent respiration with mandibular movement, SpO2 ≥ 90%, opioid administration, and no continuous deep sedation.

The sensitivity and specificity of the 3DSQ for predicting death in advanced cancer patients within 3 days was 94.3% and 26.3%, respectively. In previous studies, the sensitivity of SQ to predict prognosis cancer patients within 12 months was 48.2–83.7%, and the specificity was 69.3–89.8%. 11 , 12 , 13 Additionally, the sensitivity and specificity of the 30‐day Surprise Question proposed by Hamano et al., were 95.6% and 37%, respectively. 10 Compared to these results, the 3DSQ had a higher sensitivity. The ability to avoid missing a patient who may die within 3 days is one of the 3DSQ's greatest strengths because families were reported to be most stressed during an unexpected death of a patient. 14

One possible reason for the high sensitivity of the 3DSQ is the standardization of the questions to when the patient had PPS ≤20. A lot of physicians knew that patients with PPS ≤20 had a poorer prognosis. This may have caused the physicians to respond with "Not Surprised". PPS ≤20 is a physical sign that has a predictable prognosis within 3 days. However, its sensitivity was 64%, 9 and the current study showed that 3DSQ was more sensitive. SQ is partly dependent on the physician's intuition 15 and this suggests that the sensitivity was increased by the addition of the physician's intuition based on the patient's condition (age, primary disease, symptoms, and general condition etc.) to the PPS≤20 physical signs. It is possible that the physician's intuition elicited by SQ may have increased sensitivity.

Based on the results of the SQ from the current and previous studies, the specificity tended to decrease from 69.3–89.8% at 12 months, 11 , 12 , 13 37% at 30 days, 10 and 26.3% at 3 days. This implies that as the prediction period gets shorter, the SQ is less accurate in determining which patients will die. 10 This may be the reason for the low specificity of the 3DSQ. However, it is important that the 3DSQ was found to be a highly sensitive prognostic tool in this study. If physicians answered "Not surprised" to the 3DSQ, the physicians had to ‘carefully explain to the patient's family the likelihood that the patient will die within 3 days. At the same time, the possibility of missing predictions due to the low specificity needed to be carefully explained as well. Consequently, we believe the 3DSQ is a useful tool for identifying patients who are likely to die within 3 days.

Physicians sometimes make wrong predictions that patients would live longer. This may be exhausting for the patient's families and damaging to the physician's relationship with them. When the patient is close to death, their family members hope to stay with the patients. 16 However, in today's society, families are not always able to stay with their patients for as long as they would like because most of their families have to take time off from work and household chores and childcare to visit patients. In this study, we associated five variables with the “Lived longer group.” Pulselessness of radial artery, respiration with mandibular movement, and low oxygen saturation were known specific physical signs associated with death within 2 to 3 days. 17 Thus, the absence of these signs predicts patient survival for more than 3 days. Patients who were given opioids were predicted to have poorer prognosis, and this may be related to delirium. Several studies proved that opioid administration was significantly associated with an increased risk of delirium. 18 There were also reports that patients with hypoactive delirium were more common than expected in advanced cancer patients. 19 Hence, the poor response of patients due to hypoactive delirium may have caused the poorer prognosis. This study revealed that patients who were not on continuous deep sedation were more likely to have long‐term survival, contrary to the physician's prognosis. The patients in the group that did not receive continuous deep sedation may have been in a poor general condition, so they did not need sedation. 20 , 21

This study has some limitations. First, the treatment plans differed from that of the general wards because the facilities were limited to cancer patients admitted to the palliative care units. However, it is unlikely that multidisciplinary therapy will be used for patients with advanced cancer in general wards especially in those with a PPS ≤20. Second, the physicians may have used other prognostic tools (i.e., PaP score, PPI, PiPS models, etc.) in clinical practice and their response to the 3DSQ may have been influenced by other prognostic tools. However, we consider that these prognostic tools do not affect this study because they were not designed to predict imminent death. Third, all assessments were performed by palliative care physicians. Therefore, studies involving physicians in other departments may yield different results in terms of sensitivity and specificity. In the future, we need to expand the scope of the study to include a wider range of diseases and institutions to confirm the usefulness of the 3DSQ.

5. CONCLUSION

The 3‐Day Surprise Question is a viable screening tool to identify advanced cancer patients with impending death, especially within 3 days.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Tomoo Ikari: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing.

Yusuke Hiratsuka: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, —review and editing.

Takuhiro Yamaguchi: data curation, formal analysis, writing—review, and editing.

Isseki Maeda: Investigation, Writing—review and editing.

Masanori Mori: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing—review and editing.

Yu Uneno: Investigation, Writing—review and editing.

Tomohiko Taniyama: Investigation, Writing—review and editing.

Yosuke Matsuda: Investigation, Writing—review and editing.

Kiyofumi Oya: Investigation, Writing—review and editing.

Keita Tagami: Investigation, Writing—review and editing.

Akira Inoue: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing—original draft.

FUNDING INFORMATION

EASED study was supported by a Grant‐in‐Aid from the Japanese Hospice Palliative Care Foundation.

ETHICS STATEMENT

We conducted this study in accordance with the ethical standards of the Helsinki Declaration and the ethical guidelines for epidemiological research of the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare in Japan. All patients had access to the study information and were free to refuse to participate or secede. The local institutional review boards of all participating institutions approved the study.

The study was approved by the independent ethics committee of Tohoku University School of Medicine (approval no. 2016‐1‐689) and the local ethics committee of each participating center.

ETHICAL APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

Procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the independent ethics committee of Tohoku University School of Medicine (approval no. 2016‐1‐689) and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Written consent was unnecessary and patients were provided the opportunity to opt out.

Supporting information

Table S1

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

This study was performed in the East‐Asian collaborative cross‐cultural Study to Elucidate the Dying process (EASED). The participating study sites and site investigators in Japan were as follows: Satoshi Inoue, MD (Seirei Hospice, Seirei Mikatahara General Hospital), Naosuke Yokomichi, MD, PhD (Department of Palliative and Supportive Care, Seirei Mikatahara General Hospital), Kengo Imai, MD (Seirei Hospice, Seirei Mikatahara General Hospital), Tatsuya Morita, MD (Department of Palliative and Supportive Care, Seirei Mikatahara General Hospital), Hiroaki Tsukuura, MD, PhD (Department of Palliative Care, TUMS Urayasu Hospital), Toshihiro Yamauchi, MD (Seirei Hospice, Seirei Mikatahara General Hospital), Akemi Shirado Naito, MD (Department of palliative care Miyazaki Medical Association Hospital), Akira Yoshioka, MD, PhD (Department of Oncology and Palliative Medicine, Mitsubishi Kyoto Hospital), Shuji Hiramoto, MD (Department of Oncology and Palliative Medicine, Mitsubishi Kyoto Hospital), Ayako Kikuchi, MD (Department of Oncology and Palliative Medicine, Mitsubishi Kyoto Hospital), Tetsuo Hori, MD (Department of Respiratory surgery, Mitsubishi Kyoto Hospital), Hiroyuki Kohara, MD, PhD (Hiroshima Prefectural Hospital), Hiromi Funaki, MD (Hiroshima Prefectural Hospital), Keiko Tanaka, MD, PhD (Department of Palliative Care Tokyo Metropolitan Cancer & Infectious Diseases Center Komagome Hospital), Kozue Suzuki, MD (Department of Palliative Care Tokyo Metropolitan Cancer & Infectious Diseases Center Komagome Hospital), Tina Kamei, MD (Department of Palliative Care, NTT Medical Center Tokyo), Yukari Azuma, MD (Home Care Clinic Aozora Shin‐Matsudo), Koji Amano, MD (Department of Palliative Medicine, Osaka City General Hospital), Teruaki Uno, MD (Department of Palliative Medicine, Osaka City General Hospital), Jiro Miyamoto, MD (Department of Palliative Medicine, Osaka City General Hospital), Hirofumi Katayama, MD (Department of Palliative Medicine, Osaka City General Hospital), Hideyuki Kashiwagi, MD, MBA. (Aso Iizuka Hospital/Transitional and Palliative Care), Eri Matsumoto, MD (Aso Iizuka Hospital/Transitional and Palliative Care), Takeya Yamaguchi, MD (Japan Community Health care Organization Kyushu Hospital/Palliative Care), Tomonao Okamura, MD, MBA. (Aso Iizuka Hospital/Transitional and Palliative Care), Hoshu Hashimoto, MD, MBA. (Inoue Hospital/Internal Medicine), Shunsuke Kosugi, MD (Department of General Internal Medicine, Aso Iizuka Hospital), Nao Ikuta, MD (Department of Emergency Medicine, Osaka Red Cross Hospital), Yaichiro Matsumoto, MD (Department of Transitional and Palliative Care, Aso Iizuka Hospital), Takashi Ohmori, MD (Department of Transitional and Palliative Care, Aso Iizuka Hospital), Takehiro Nakai, MD (Immuno‐Rheumatology Center, St Luke's International Hospital), Takashi Ikee, MD (Department of Cardiorogy, Aso Iizuka Hospital), Yuto Unoki, MD (Department of General Internal Medicine, Aso Iizuka Hospital), Kazuki Kitade, MD (Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Saga‐Ken Medical Centre Koseikan), Shu Koito, MD (Department of General Internal Medicine, Aso Iizuka Hospital), Nanao Ishibashi, MD (Environmental Health and Safety Division, Environmental Health Department, Ministry of the Environment), Masaya Ehara, MD (TOSHIBA), Kosuke Kuwahara, MD (Department of General Internal Medicine, Aso Iizuka Hospital), Shohei Ueno, MD (Department of Hematology/Oncology, Japan Community Healthcare Organization Kyushu Hospital), Shunsuke Nakashima, MD (Oshima Clinic), Yuta Ishiyama, MD (Department of Transitional and Palliative Care, Aso Iizuka Hospital), Akihiro Sakashita, MD, PhD (Department of Palliative Medicine, Kobe University School of Medicine), Ryo Matsunuma, MD (Department of Palliative Medicine, Kobe University Graduate School of Medicine), Hana Takatsu, MD (Division of Palliative Care, Konan Medical Center), Takashi Yamaguchi, MD, PhD (Division of Palliative Care, Konan Medical Center), Satoko Ito, MD (Hospice, The Japan Baptist Hospital), Toru Terabayashi, MD (Hospice, The Japan Baptist Hospital), Jun Nakagawa, MD (Hospice, The Japan Baptist Hospital), Tetsuya Yamagiwa, MD, PhD (Hospice, The Japan Baptist Hospital), Akira Inoue, MD, PhD (Department of Palliative Medicine Tohoku University School of Medicine), Mitsunori Miyashita, R.N., PhD (Department of Palliative Nursing, Health Sciences, Tohoku University Graduate School of Medicine), Saran Yoshida, PhD (Graduate School of Education, Tohoku University), Hiroaki Watanabe, MD (Department of Palliative Care, Komaki City Hospital), Takuya Odagiri, MD (Department of Palliative Care, Komaki City Hospital), Tetsuya Ito, MD, PhD (Department of Palliative Care, Japanese Red Cross Medical Center), Masayuki Ikenaga, MD (Hospice, Yodogawa Christian Hospital), Keiji Shimizu, MD, PhD (Department of Palliative Care Internal Medicine, Osaka General Hospital of West Japan Railway Company), Akira Hayakawa, MD, PhD (Hospice, Yodogawa Christian Hospital), Rena Kamura, MD (Hospice, Yodogawa Christian Hospital), Takeru Okoshi, MD, PhD (Okoshi Nagominomori Clinic), Tomohiro Nishi, MD (Kawasaki Municipal Ida Hospital, Kawasaki Comprehensive Care Center), Kazuhiro Kosugi, MD (Department of Palliative Medicine, National Cancer Center Hospital East), Yasuhiro Shibata, MD (Kawasaki Municipal Ida Hospital, Kawasaki Comprehensive Care Center), Takayuki Hisanaga, MD (Department of Palliative Medicine, Tsukuba Medical Center Hospital), Takahiro Higashibata, MD, PhD (Department of General Medicine and Primary Care, Palliative Care Team, University of Tsukuba Hospital), Ritsuko Yabuki, MD (Department of Palliative Medicine, Tsukuba Medical Center Hospital), Shingo Hagiwara, MD, PhD (Department of Palliative Medicine, Yuai Memorial Hospital), Miho Shimokawa, MD (Department of Palliative Medicine, Tsukuba Medical Center Hospital), Satoshi Miyake, MD, PhD (Professor, Department of Clinical Oncology Graduate School of Medical and Dental Sciences Tokyo Medical and Dental University (TMDU)), Junko Nozato, MD (Specially Appointed Assistant Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, Palliative Care, Medical Hospital, Tokyo Medical and Dental University), Hiroto Ishiki, MD (Department of Palliative Medicine, National Cancer Center Hospital), Tetsuji Iriyama, MD (Specially Appointed Assistant Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, Palliative Care, Medical Hospital, Tokyo Medical and Dental University), Keisuke Kaneishi, MD, PhD (Department of Palliative Care Unit, JCHO Tokyo Shinjuku Medical Center), Mika Baba, MD, PhD (Department of Palliative medicine Suita Tokushukai Hospital), Tomofumi Miura, MD, PhD (Department of Palliative Medicine, National Cancer Center Hospital East), Yoshihisa Matsumoto, MD, PhD (Department of Palliative Medicine, National Cancer Center Hospital East), Ayumi Okizaki, PhD (Department of Palliative Medicine, National Cancer Center Hospital East), Yuki Sumazaki Watanabe, MD (Department of Palliative Medicine, National Cancer Center Hospital East), Yuko uehara, MD (Department of Palliative Medicine, National Cancer Center Hospital East), Eriko Satomi, MD (Department of palliative medicine, National Cancer Center Hospital), Kaoru Nishijima, MD (Department of Palliative Medicine, Kobe University Graduate School of Medicine), Junichi Shimoinaba, MD (Department of Hospice Palliative Care, Eikoh Hospital), Ryoichi Nakahori, MD (Department of Palliative Care, Fukuoka Minato Home Medical Care Clinic), Takeshi Hirohashi, MD (Eiju General Hospital), Jun Hamano, MD, PhD (Assistant Professor, Faculty of Medicine, University of Tsukuba), Natsuki Kawashima, MD (Department of Palliative Medicine, Tsukuba Medical Center Hospital), Takashi Kawaguchi, PhD (Tokyo University of Pharmacy and Life Sciences Department of Practical Pharmacy), Megumi Uchida, MD, PhD (Dept. of Psychiatry and Cognitive‐Behavioral Medicine, Nagoya City University Graduate School of Medical Sciences), Ko Sato, MD, PhD (Hospice, Ise Municipal General Hospital), Yoichi Matsuda, MD, PhD (Department of Anesthesiology & Intensive Care Medicine/Osaka University Graduate School of Medicine), Yutaka Hatano, MD, PhD (Hospice, Gratia Hospital), Satoru Tsuneto, MD, PhD (Professor, Department of Human Health Sciences, Graduate School of Medicine, Kyoto University Department of Palliative Medicine, Kyoto University Hospital), Sayaka Maeda, MD (Department of Palliative Medicine, Kyoto University Hospital), Yoshiyuki Kizawa MD, PhD, FJSIM, DSBPMJ. (Designated Professor and Chair, Department of Palliative Medicine, Kobe University School of Medicine), Hiroyuki Otani, MD (Palliative Care Team, and Palliative and Supportive Care, National Kyushu Cancer Center).

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of current study are available on request from the corresponding author.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ellershaw J, Ward C. Care of the dying patient: the last hours or days of life. BMJ. 2003;326(7379):30‐34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Anderson F, Downing GM, Hill J, Casorso L, Lerch N. Palliative performance scale (PPS): a new tool. J Palliat Care. 1996;12(1):5‐11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Morita T, Tsunoda J, Inoue S, Chihara S. The palliative prognostic index: a scoring system for survival prediction of terminally ill cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 1999;7(3):128‐133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gwilliam B, Keeley V, Todd C, et al. Development of prognosis in palliative care study (PiPS) predictor models to improve prognostication in advanced cancer: Prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2011;343:d4920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Billings JA, Bernacki R. Strategic targeting of advance care planning interventions: the goldilocks phenomenon. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(4):620‐624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Baba M, Maeda I, Morita T, et al. Survival prediction for advanced cancer patients in the real world: a comparison of the palliative prognostic score, delirium‐palliative prognostic score, palliative prognostic index and modified prognosis in palliative care study predictor model. Eur J Cancer. 2015;51(12):1618‐1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. White N, Reid F, Vickerstaff V, Harries P, Stone P. Specialist palliative medicine physicians and nurses accuracy at predicting imminent death (within 72 hours): a short report. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2020;10(2):209‐212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hui D, Hess K, dos Santos R, Chisholm G, Bruera E. A diagnostic model for impending death in cancer patients: preliminary report. Cancer. 2015;121(21):3914‐3921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hui D, dos Santos R, Chishoim G, et al. Clinical signs of impending death in cancer patients. Oncologist. 2014;19:681‐687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hamano J, Morita T, Inoue S, et al. Surprise questions for survival prediction in patients with advanced cancer: a multicenter prospective cohort study. Oncologist. 2015;20(7):839‐844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. White N, Kupeli N, Vickerstaff V, Stone P. How accurate is the ‘Surprise Question’ at identifying patients at the end of life? A systematic review and meta‐analysis. BMC Med. 2017;15(1):139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Moroni M, Zocchi D, Bolognesi D, et al. The ‘surprise’ question in advanced cancer patients: a prospective study among general practitioners. Palliat Med. 2014;28(7):959‐964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lefkowits C, Chandler C, Sukumvanich P, et al. Validation of the “surprise question” in gynecologic oncology: comparing physicians, advanced practice providers, and nurses. Gynecol Oncol. 2016;141:128.26867989 [Google Scholar]

- 14. Barry LC, Kasl SV, Prigerson HG. Psychiatric disorders among bereaved persons: the role of perceived circumstances of death and preparedness for death. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;10:447‐457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gerlach C, Goebel S, Weber S, Weber M, Sleeman KE. Space for intuition ‐ the ‘Surprise'‐Question in haemato‐oncology: qualitative analysis of experiences and perceptions of haemato‐oncologists. Palliat Med. 2019;33(5):531‐540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hwang IC, Ahn HY, Park SM, Shim JY, Kim KK. Clinical changes in terminally ill cancer patients and death within 48 h: when should we refer patients to a separate room? Support Care Cancer. 2013;21(3):835‐840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bruera S, Chisholm G, Santos RD, Crovador C, Bruera E, Hui D. Variations in vital signs in the last days of life in patients with advanced cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014;48(4):510‐517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Grudreau JD, Gagnon P, Roy MA, Harel F, Tremblay A. Opioid medications and longitudinal risk of delirium in hospitalized cancer patients. Cancer. 2007;109:2365‐2373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lawlor PG, Gagnon B, Mancini IL, et al. Occurrence, causes, and outcome of delirium in patients with advanced cancer: a Prospective study. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(6):786‐794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sykes N, Thorns A. The use of opioids and sedatives at the end of life. Lancet Oncol. 2003;4:312‐318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Maltoni M, Pittureri C, Scarpi E, et al. Palliative sedation therapy does not hasten death: results from a prospective multicenter study. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of current study are available on request from the corresponding author.