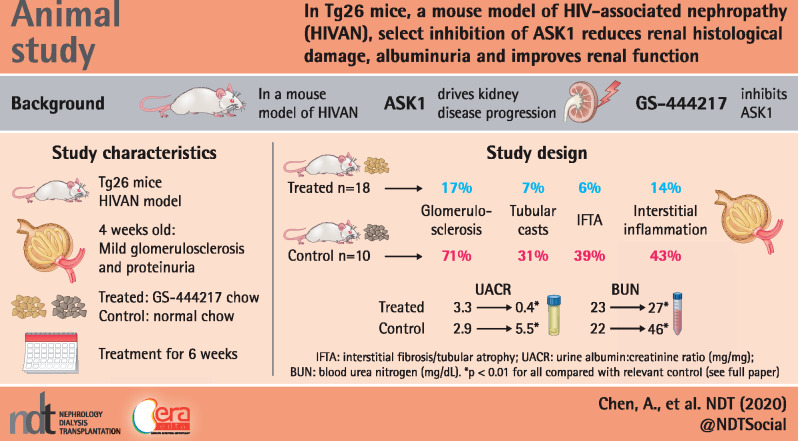

Graphical Abstract

Keywords: albuminuria, ASK1, fibrosis, glomerulosclerosis, HIVAN, inflammation, podocyte

Abstract

Background

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a common cause of morbidity and mortality in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive individuals. Among the HIV-related kidney diseases, HIV-associated nephropathy (HIVAN) is a rapidly progressive renal disease characterized by collapsing focal glomerulosclerosis (GS), microcystic tubular dilation, interstitial inflammation and fibrosis. Although the incidence of end-stage renal disease due to HIVAN has dramatically decreased with the widespread use of antiretroviral therapy, the prevalence of CKD continues to increase in HIV-positive individuals. Recent studies have highlighted the role of apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 (ASK1) in driving kidney disease progression through the activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase and c-Jun N-terminal kinase and selective ASK-1 inhibitor GS-444217 was recently shown to reduce kidney injury and disease progression in various experimental models. Therefore we examined the efficacy of ASK1 antagonism by GS-444217 in the attenuation of HIVAN in Tg26 mice.

Methods

GS-444217-supplemented rodent chow was administered in Tg26 mice at 4 weeks of age when mild GS and proteinuria were already established. After 6 weeks of treatment, the kidney function assessment and histological analyses were performed and compared between age- and gender-matched control Tg26 and GS-444217-treated Tg26 mice.

Results

GS-444217 attenuated the development of GS, podocyte loss, tubular injury, interstitial inflammation and renal fibrosis in Tg26 mice. These improvements were accompanied by a marked reduction in albuminuria and improved renal function. Taken together, GS-4442217 attenuated the full spectrum of HIVAN pathology in Tg26 mice.

Conclusions

ASK1 signaling cascade is central to the development of HIVAN in Tg26 mice. Our results suggest that the select inhibition of ASK1 could be a potential adjunctive therapy for the treatment of HIVAN.

KEY LEARNING POINTS

What is already known about this subject?

chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a common cause of morbidity and mortality in HIV-positive individuals;

among the HIV-related kidney diseases, HIV-associated nephropathy (HIVAN) is a rapidly progressive renal disease characterized by severe glomerular and tubular injury, interstitial inflammation and fibrosis and

effective therapeutic treatment against HIVAN is not currently available.

What this study adds?

recently, inhibition of ASK1 activation by GS-444217 was shown to reduce renal fibrosis and disease progression in various rodent models of CKD;

in this article, we utilize a transgenic mouse model of HIVAN, Tg26, to show that GS-444217 attenuates the entire spectrum of HIVAN and improved kidney function in vivo.

What impact this may have on practice or policy?

the clinical analog of GS-444217, selonsertib (Gilead Sciences), was recently reported to slow the decline in renal function in patients with diabetic kidney disease and

our results provide a pre-clinical basis for select inhibition of ASK1 as a potential adjunctive therapy for the treatment of HIVAN.

INTRODUCTION

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-related kidney disease is associated with significant morbidity and mortality in the HIV population. Among these, HIV-associated nephropathy (HIVAN) is a major cause of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) in individuals with advanced HIV disease, occurring primarily among those of African descent [1, 2]. Although the overall mortality attributed to HIVAN has declined with the introduction of combination antiretroviral therapy in the recent years [3], there is an increased prevalence of noncollapsing focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) and other forms of CKD in HIV-positive individuals [4–6].

Classic HIVAN is histologically characterized by the collapsing form of FSGS, tubular cell apoptosis, microcystic tubular dilation, interstitial inflammation and fibrosis [7]. The ultrastructural changes observed in HIVAN include podocyte foot process effacement and their dedifferentiation [8]. The understanding of the molecular mechanisms driving the pathogenesis of HIVAN has been greatly advanced by the use of a mouse model of HIVAN, Tg26 mice, which expresses the gag/pol-deleted HIV-1 provirus transgene under the endogenous HIV promoter [9]. Tg26 mice in the FVB/N background develop advanced glomerulosclerosis (GS), tubulointerstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy and microcystic dilatation [10, 11]. The progression of kidney disease to renal failure in Tg26 mice occurs rapidly, resulting in death by uremia between the ages of 12–24 weeks. Using the Tg26 mouse model, we and others have identified several key pathways that are implicated in HIVAN progression [11–16]. However, despite growing knowledge about the pathogenesis of HIVAN [7], therapeutic options are still lacking.

Recently, apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 (ASK1) was shown to be an important target for CKD progression [17]. ASK1 is a member of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase (MAP3K) family that regulates the downstream signaling cascade of p38 and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) in response to a variety of cellular stresses [18], and ASK1-mediated sustained activation of p38 and JNK leads to apoptosis [19, 20]. In kidney cells, its function is implicated in the tubular p38 activation in ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury and promoting renal fibrosis in a murine model of the obstructed kidney [21, 22]. The select antagonism of ASK1 by the use of a small molecule ASK1 inhibitor, GS-444217, was shown to mitigate the renal inflammation and fibrosis in various experimental models of kidney injury [23–25]. Liles et al. [25] recently showed that GS-444217 administration reduced tubular injury and cell death in the rodent I/R model of acute kidney injury; reduced tubular cell death, interstitial inflammation and fibrosis in the unilateral ureteral obstruction (UUO) model of renal fibrosis; and reduced glomerular injury and improved renal function in a model of diabetic kidney disease (DKD). GS-444217 was also shown to attenuate glomerular damage, renal inflammation and fibrosis in the rodent model of nephrotoxic serum nephritis [24]. The ASK1 pathway does not impact hemodynamics or vascular tone [26], indicating that an ASK1 inhibitor could be complementary to current CKD therapies, such as inhibitors of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system and sodium–glucose cotransporter 2, that improve renal outcomes by reducing glomerular hemodynamic stress.

Given that renal cell apoptosis, inflammation and tubulointerstitial fibrosis are key features in human HIVAN kidneys, in the present study we explored the role of ASK1 in HIVAN progression. The antagonism of ASK1 by GS-444217 resulted in significant protection against glomerular and podocyte damage, tubular injury, renal inflammation and fibrosis to mitigate the rapid progression of HIVAN in Tg26 mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

HIVAN mouse model

Tg26 mice on an FVB/N genetic background bearing a defective HIV-1 provirus lacking gag-pol were previously described [27]. GS-444217, provided by Gilead Sciences (Foster City, CA, USA), was homogeneously incorporated into standard rodent chow (Purina chow 5001, Research Diets, New Brunswick, NJ, USA) before being pelleted. The serum concentration of GS-444217 in Tg26 mice after feeding GS-444217-incorporated chow (0.1–0.3% by weight) was performed using iquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC-MS) by Agilux Laboratories (Worcester, MA, USA). Heterozygous Tg26 mice and their corresponding wild-type and Tg26 littermates were fed with regular rodent chow or chow containing 0.1% or 0.2% GS-444217, starting at 4 weeks of age for 6 weeks. Since renal disease severity and progression can widely differ in Tg26 mice, we selected Tg26 mice with established mild proteinuria (1–2+ with urine dipstick test) at 4 weeks of age for random selection into control and treatment groups, as performed previously [28]. All mice were euthanized at 10 weeks of age for blood, urine and tissue collection. All animal studies were performed according to the protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine (IACUC-2015-0090).

Kidney function assessment

Urine albumin was measured using a commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Bethyl Laboratory, Houston, TX, USA). Urine creatinine levels were quantified using the Creatinine Colorimetric Assay Kit (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI, USA). Urine albumin excretion is expressed as an albumin:creatinine ratio. Blood urea nitrogen (BUN) content was measured using a commercially available kit (BioAssay Systems, Hayward, CA, USA).

Histological analysis

Kidney samples were fixed in 10% formalin, embedded in paraffin and sectioned to 4-μm thickness. Periodic acid–Schiff (PAS)-stained sections were used for the assessment of histologic changes. A kidney pathologist masked to the experimental groups quantified the extent of renal damage using histologic criteria as described previously [29]. In addition to the histological scoring of PAS-stained kidneys, renal fibrosis was additionally evaluated by picrosirius red staining on paraffin-embedded kidney sections according to the manufacturer’s instructions (ab150681, Abcam, Cambridge, UK).

Transmission electron microscopy and morphometric studies

Tissues were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde with 0.1 M sodium cacodylate (pH 7.4) for 72 h at 4°C. Samples were further incubated with 2% osmium tetroxide and 0.1 M sodium cacodylate (pH 7.4) for 1 h at room temperature. Ultrathin sections were stained with lead citrate and uranyl acetate and viewed on a H7650 microscope (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan). Briefly, negatives were digitized and images with a final magnitude of up to ×10 000 were obtained. ImageJ version 1.26t software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA; rsb.info.nih.gov) was used to measure the width of the peripheral glomerular basement membrane (GBM), and the number of slit pores overlying this GBM length was counted. The arithmetic mean of the foot process width (WFP) was calculated as shown below:

where ΣSlits indicates the total number of slits counted; ΣGBM Length indicates the total GBM length measured in one glomerulus and π/4 is the correction factor for the random orientation by which the foot processes were sectioned, as described in Koop et al. [30].

Immunostaining

Immunostaining was conducted on paraffin-embedded or frozen kidney sections using standard procedures using the following primary antibodies: phospho- and total p38, phospho-JNK and CD68; antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA, USA). CD3, CD31 and Wilms' tumor-1 (WT-1) antibodies were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA, USA). The anti-synaptopodin antibody used for immunostaining was supplied by Mundel et al. [31]. Secondary antibodies were obtained from Jackson Immuno Research Labs (West Grove, PA, USA). Immunostained images were acquired with the Zeiss LSM microscope (Carl Zeiss Microscopy, Thornwood, NY, USA) and analyzed with ZEN (Zeiss) and ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health; https://imagej.nih.gov). For quantitative analysis of immunostained images, 20–30 glomeruli were scored per mouse and averaged per mouse.

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from kidney cortices using TRIzol (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). First-strand complementary DNA (cDNA) was prepared from total RNA (2.0 μg) using the Superscript III first-strand synthesis kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and cDNA (1 μL) was amplified in triplicate using SYBR GreenER quantitative PCR (qPCR) Supermix (Thermo Fisher Scientific) on an ABI PRISM 7900HT (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). LightCycler analysis software (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) was used to determine crossing points using the second derivative method. Data were normalized to a housekeeping gene and presented as a fold increase compared with RNA isolated from control animals using the 2−ΔΔCT method.

Statistical analysis

Data are reported as mean [standard deviation (SD)]. For the comparison between two groups, an unpaired two-tailed t-test was used. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s test was used for comparison between three or more groups. Prism version 7 software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA) was used for statistical analyses. Data were considered statistically significant when P < 0.05.

RESULTS

GS-444217 reduced the ASK1-mediated activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) in Tg26 mouse kidneys

The heterozygous Tg26 mice have rapid progression of kidney disease that proceeds to renal failure between the ages of 2–6 months [9, 10, 27]. Our previous study, in which the transcriptomic profiles were analyzed from serial biopsies of Tg26 kidneys, demonstrated the presence of mild GS by 4 weeks of age, moderate GS and mild tubulointerstitial injury by 8 weeks of age and advanced GS and tubulointerstitial fibrosis, tubular atrophy and dilatation by 12 weeks of age [11]. Querying of this transcriptomic dataset showed that the messenger RNA (mRNA) expression levels of ASK1 (Map3k5) and its downstream targets p38 MAPK (Mapk14) and JNK (Mapk8) did not significantly differ over time and were comparable to healthy wild-type controls (Supplementary data, Figure S1).

To determine the appropriate dosing regimen of GS-444217 in Tg26 mice, Tg26 mice were given rodent chow supplemented with 0.1, 0.2 or 0.3% GS-444217 (by weight) and the circulating levels of GS-444217 were tested after 4 days. While the levels of GS-444217 in Tg26 mice in blood samples drawn in the morning following the nocturnal feeding window varied among the three groups, their levels normalized to comparable degrees in all groups by the afternoon (Supplementary data, Figure S2). Based on the previous studies of GS-444217 in rodent models of CKD [23, 25], 0.1 and 0.2% GS-444217 were selected as the appropriate dosing for Tg26 mice. However, because the results of the renal outcome and histologic analyses were indistinguishable between 0.1 and 0.2% GS-444217-treated Tg26 mice, the data are shown hereafter as a combined single treatment group compared with control Tg26 and wild-type littermates.

To test the efficacy of ASK1 inhibition in attenuating the course of HIVAN in Tg26 mice, Tg26 mice were fed with GS-444217-containing chow for 6 weeks starting at 4 weeks of age (Tg26-GS444217, n = 18). Age- and gender-matched Tg26 (Tg-control, n = 10) and wild-type littermates in the FVB/N background (FVB WT, n = 9) fed regular rodent chow were used as controls. Since renal disease severity and progression can vary significantly in Tg26 mice, we selected Tg26 mice with established mild proteinuria (1–2+ with urine dipstick test) at 4 weeks of age for random selection into control and treatment groups, as performed previously [28]. There were no appreciable differences in the body weight or kidney:body weight ratio after 6 weeks of GS-444217 administration in Tg26 mice (Supplementary data, Figure S3). GS-444217 also did not appear to change the HIV gene expression in Tg26 mice, as assessed by nef mRNA expression in kidney cortices by qPCR (Supplementary data, Figure S4).

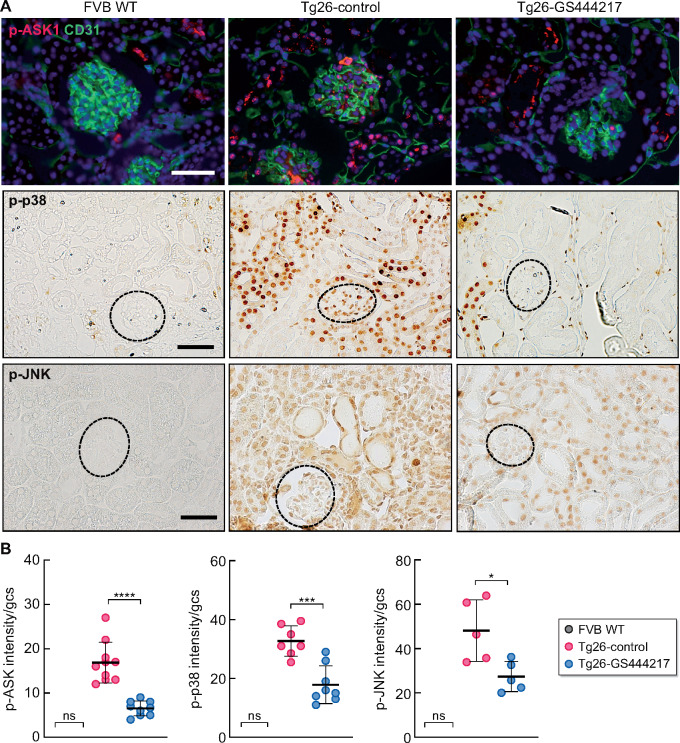

As anticipated, a significant increase in the activation of ASK1 and p38 proteins was observed in Tg26-control kidneys compared with FVB WT kidneys, which were markedly attenuated in Tg26-GS444217 kidneys (Figure 1). In Tg26 kidneys, phosphorylated ASK1, p38 and JNK (p-ASK1, p-p38 and p-JNK) were pronounced in the tubular and interstitial cells, as well as in glomerular cells (Figure 1A). Using p-p38 as a surrogate of ASK1 activation, we further observed that high levels of p-p38 costained with podocyte and endothelial markers in the glomeruli of Tg26 kidneys (Supplementary data, Figure S5A), although the total level of p38 expressed in kidney cells remained comparable in all three groups (Supplementary data, Figure S5B). Western blot analysis of kidney cortices confirmed the increase in p38 phosphorylation in Tg26 kidneys that were attenuated with GS-444217 without changes in the total levels of p38 protein (Supplementary data, Figure S5C), indicating an effective blockade of ASK1 by GS-444217 in Tg26 kidney cells.

FIGURE 1.

GS-444217 administration reduces the activation of ASK1 and its downstream targets p38 and JNK in Tg26 HIVAN kidneys. (A) Expression of phosphorylated ASK1, p38 and JNK in wild-type FVB controls (FVB WT), control Tg26 mice (Tg-control) and Tg26 mice after GS-444217 treatment (Tg26-GS444217). Top panels show the representative images of phosphorylated ASK1 (pASK1, red) immunofluorescence co-stained with CD31 endothelial marker (green). DNA is counterstained in blue. The middle and bottom panels show representative immunohistochemical staining of phosphorylated p38 and JNK (p-p38, p-JNK). Glomeruli are outlined with dotted lines. Scale bars, 50 μm. (B) Average intensity of p-ASK1, p-p38 and p-JNK (in arbitrary units) in the glomerular cross section (gcs) per mouse of FVB WT and Tg26 mice. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001 and ***P < 0.0001 when compared between indicated groups by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test.

GS-444217 treatment reduced HIVAN injuries and improved kidney function in Tg26 mice

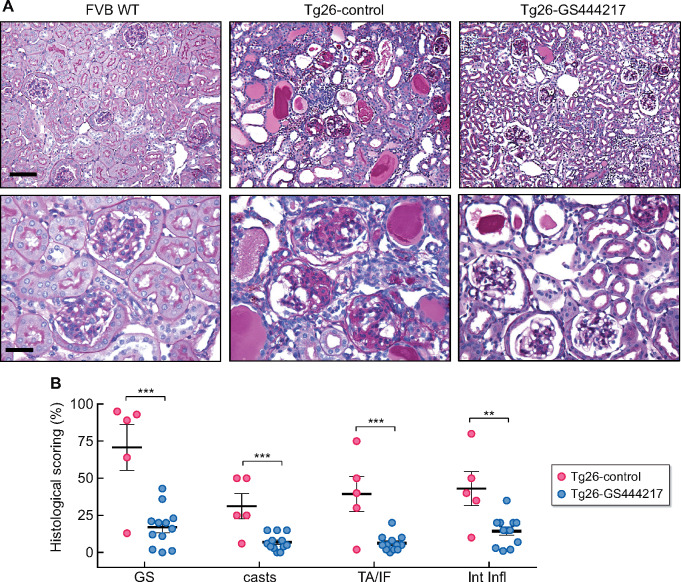

We next examined the effect of reduced ASK1 activation in Tg26 kidney pathology. PAS-stained kidneys of Tg26 mice showed the typical pathological features of HIVAN (Figure 2A), namely severe GS (∼71% of glomeruli), the presence of tubular casts (∼31% of cortex area), tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis (∼39%) and interstitial inflammation (∼43%) (Figure 2B). All of these parameters were significantly blunted in Tg26-GS444217 mouse kidneys, such that GS was reduced to ∼17%, tubular casts to ∼7%, tubular atrophy and fibrosis to ∼6% and interstitial inflammation to ∼14% (Figure 2A and B).

FIGURE 2.

GS-444217 administration attenuates the histopathologic changes in Tg26 mice. (A) Representative images of PAS-stained kidneys at low and high magnifications. Scale bars, 50 μm (top panel) and 20 μm (bottom panel). (B) Histological scoring of percent GS, tubular casts (casts), tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis (TA/IF) and interstitial inflammation (Int Infl) after 6 weeks of treatment (n = 5 mice for FVB WT and Tg26-control, n = 12 mice for Tg26-GS444217). **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 when compared between Tg26-control and Tg26-GS444217 groups by unpaired two-tailed t-test.

The amelioration in these histopathological features in Tg26-GS444217 mice was accompanied by improvements in their renal function. At baseline before the treatment, 4-week-old Tg26 mice in both groups were comparable and showed mild albuminuria (Table 1). After 6 weeks, the average urinary creatinine:albumin ratio (UACR) nearly doubled in Tg26-control mice, whereas its average was lower than the baseline before treatment in Tg26-GS444217 mice (Table 1). Interestingly, the change in UACR for individual mice showed two distinct groups in the Tg26-control mice, in which one group had a rapid elevation of UACR and the other only a mild elevation (Supplementary data, Figure S6A), likely reflecting faster and slower disease progression phenotypes [32]. Importantly, all Tg26-GS444217 mice showed the decreased UCAR compared with their baseline levels at week 0 (Supplementary data, Figure S6A), suggesting that the mitigation of glomerular damage by GS-444217 treatment may have sufficiently restored the glomerular function in Tg26 mice. The overall renal function, as measured by BUN levels, was also significantly improved after 6 weeks of GS-444217 treatment in Tg26 mice (Table 1). While the average BUN level had nearly doubled in Tg26-control mice (22.1 ± 5.9 to 45.5 ± 15.3 mg/dL) in 6 weeks, it remained relatively unchanged in Tg26-GS444217 mice (22.6 ± 5.8 to 26.6 ± 12.1 mg/dL). The individual changes for BUN confirm the rapid increase in the majority of Tg26-control mice, whereas an indolent increase was observed for most Tg26-GS444217 mice (Supplementary data, Figure S6B). Together, these results indicate an effective blockade of HIV-induced renal damage, resulting in improved renal function in Tg26 mice by ASK1 inhibition in vivo.

Table 1.

Renal function in control and Tg26 mice

| Groups | n (% male) | UACR (mg/mg), | BUN (mg/dL), | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mean ± SD | mean ± SD | ||||

| [median (IQR)] |

[median (IQR)] |

||||

| Week 0 | Week 6 | Week 0 | Week 6 | ||

| FVB WT | 9 (56) | 0.016 ± 0.007 | 0.017 ± 0.008 | 10.82 ± 0.425 | 13.76 ± 0.831 |

| [0.016 (0.011–0.017)] | [0.017 (0.009–0.022)] | [10.98 (10.39–11.18)] | [13.82 (12.96–14.54)] | ||

| Tg26-control | 10 (50) | 2.900 ± 2.100 | 5.526 ± 5.907** | 22.10 ± 5.944 | 45.52 ± 15.32**** |

| [2.388 (1.431–3.992)] | [1.985 (0.910–10.960)] | [20.91 (17.82–22.86)] | [50.51 (30.30–56.0)] | ||

| Tg26-GS444217 | 18 (61) | 3.274 ± 4.153 | 0.419 ± 0.610## | 22.61 ± 5.837 | 26.55 ± 12.13*,### |

| [2.449 (0.464–3.792)] | [0.146 (0.051–0.530)] | [23.63 (17.35–27.63)] | [26.05 (16.85–32.4)] | ||

UCAR and BUN are indicated for the baseline levels (Week 0) and after 6 weeks of treatment (Week 6).

P < 0.05,

P < 0.01 and

P < 0.0001 versus FVB WT.

P < 0.01 and

P < 0.0001 versus Tg26-control at each time point by ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc analysis.

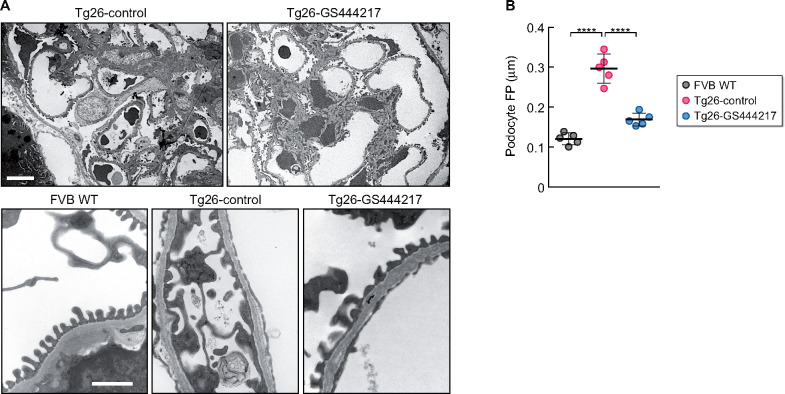

GS-444217 reduced podocyte foot process effacement and loss in Tg26 mice

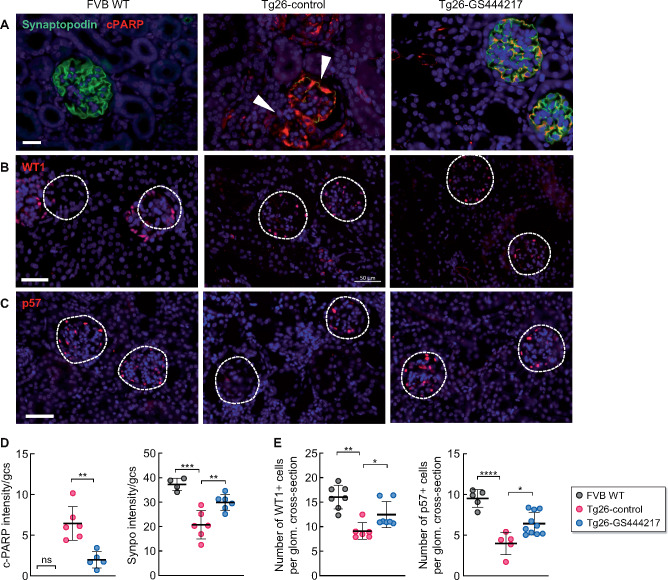

Several studies have indicated that podocyte injury is a key driver of HIVAN [12, 33]. Given that the albuminuria was significantly improved in Tg26-GS444217 mice, we next examined the ultrastructural changes in podocyte foot processes in Tg26 mice. As expected, the transmission electron microscopy images showed broadened podocyte foot processes in Tg26-control mice kidneys (Figure 3A and B). Notably, GS-444217 treatment resulted in significant improvement in the podocyte foot process architecture (Figure 3A and B). Consistent with increased podocyte injury and death in HIVAN kidneys, synaptopodin expression was markedly reduced in many of the glomeruli in Tg26-control kidneys (Figure 4A), which inversely correlated with increased expression of the cleaved form of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (cPARP) (Figure 4B), indicative of activation of programmed cell death in podocytes of Tg26 kidneys. The synaptopodin expression was largely preserved in Tg26-GS444217 kidneys, with a concomitant reduction in cPARP expression (Figure 4A and B). Semiquantitative analysis of podocyte number per glomerular cross section by Wilms' tumor 1 (WT-1) and p57 immunostaining [34, 35] further confirmed that podocytes were significantly preserved in Tg26-GS444217 kidneys compared with Tg26-control mice (Figure 4A and C). Together, these results indicate that ASK1 antagonism by GS-444217 effectively thwarts podocyte injury and loss in HIVAN kidneys.

FIGURE 3.

Ultrastructural analysis of podocyte architecture in Tg26 mice with GS-444217 treatment. (A) Representative transmission electron microscopy images of podocyte foot processes (FPs). Scale bars, 10 μm (top panel) and 1 μm (bottom panel). (B) Quantification of average podocyte FP widths per mouse. n = 5 mice per group. ****P < 0.0001 when compared between indicated groups by ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test.

FIGURE 4.

GS-444217 attenuates podocyte injury and loss in Tg26 mice. (A) Representative immunofluorescence images of synaptopodin (green) and cPARP (red). Scale bar, 20 μm. Arrowheads highlight the glomeruli (outlined) with little synaptopodin expression in Tg26-control kidneys. (B and C) Representative immunofluorescence images of (B) WT1 and (C) p57. Glomeruli are outlined with dotted lines. DNA is counterstained in blue. Scale bars, 50 μm. (D) Quantification of cPARP and synaptopodin (synpo) intensity per glomerular cross section. The fluorescence intensity is shown in arbitrary units. (E) Quantification of WT1+ and p57+ podocytes/glomerular section per mouse (n = 4–6 mice for FVB WT and Tg26-control; n = 5–10 mice for Tg26-GS444317; 25–30 glomerular sections were examined per mouse). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 and ****P < 0.0001 when compared between indicated groups by ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test.

GS-444217 reduced interstitial inflammation, tubular injury and renal fibrosis in Tg26 mice

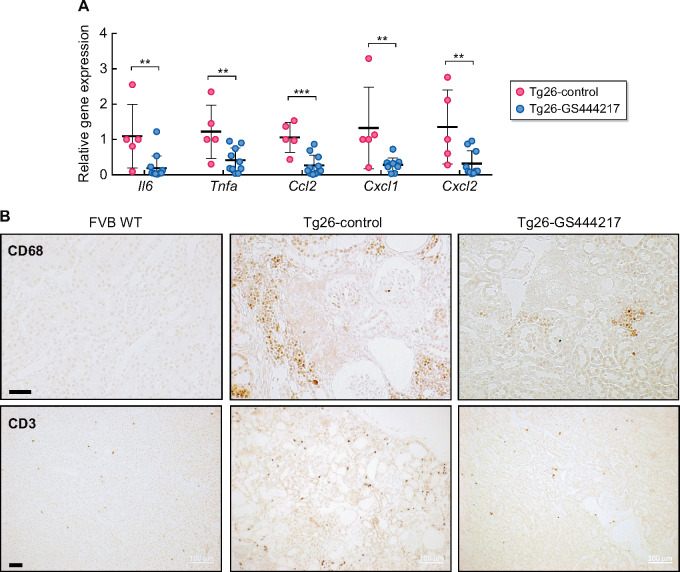

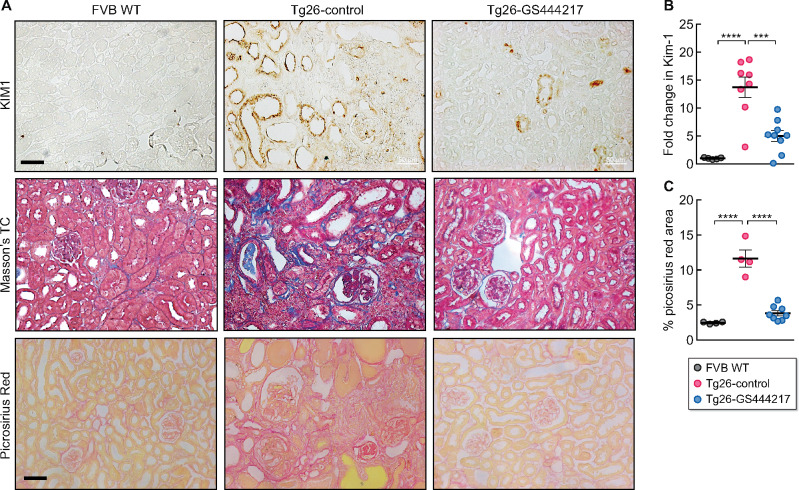

In addition to glomerular injury, prominent features of HIVAN include overt interstitial inflammation, tubular injury and atrophy and renal fibrosis, as demonstrated above in Tg26-control kidneys (Figure 2). The histological analysis indicated that ASK1 antagonism markedly reduced these parameters in Tg26 mice. To further characterize these effects by GS-444217, we first compared the expression of inflammatory cytokine and chemokine transcripts by qPCR directly between the Tg26 mouse groups, as HIV-1 infection is a potent inducer of pro-inflammatory mediators in renal tubular epithelial cells (RTECs) [36]. GS-444217 administration led to a marked reduction in Il-6, Tnfa, Ccl2, Cxcl1 and Cxcl2 mRNA expression in Tg26-GS444217 kidneys compared with Tg26-control kidneys (Figure 5A). CD68+ macrophages and CD3+ T lymphocytes were readily detectable in the interstitial areas in Tg26-control kidneys but were markedly reduced in Tg26-GS444217 kidneys (Figure 5B). In addition, a striking histological feature of GS-444217-mediated renoprotection was the significant attenuation in tubular cast formation and atrophy (Figure 2). The kidneys of Tg26-GS444217 also displayed reduced expression of kidney injury molecule-1 (KIM-1) compared with Tg26-control kidneys (Figure 6A and B). Several previous studies have underscored the pathogenic role of HIV-1 viral protein r (Vpr) and negative regulatory factor in HIVAN in kidney cell injury [37]. Vpr is implicated promoting HIVAN progression by activation of DNA damage response and apoptosis of RTECs [38, 39]. In line with the observed reduction in overall renal damage and inflammation in GS444217-treated Tg26 mice, there was a marked reduction in renal fibrosis, as assessed by the Masson’s trichrome and picrosirius red staining (Figure 6A and C). Taken together, our results indicate that the activation of ASK1 is a key driver of HIVAN progression and demonstrate that the select inhibition of ASK1 by GS-444217 mitigated the entire spectrum of HIVAN pathogenesis in Tg26 mice.

FIGURE 5.

GS-444217 attenuates renal inflammation in Tg26 mice. (A) Quantitative PCR analysis of cytokines and chemokine expression in Tg26 mouse kidney cortices (n = 5 Tg26-control, n = 10–12 Tg26-GS444217 mice). *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 when compared between two groups by unpaired one-tailed t-test. (B) Representative images of CD68 and CD3 immunostaining of control and Tg26 mouse kidneys. Scale bars, 50 μm.

FIGURE 6.

GS-444217 attenuates tubular injury and renal fibrosis in Tg26 mice. (A) Representative images of KIM-1 immunostaining, Masson’s trichrome and picrosirius red staining of control and Tg26 mouse kidneys. Scale bars, 50 μm. (B) Kim-1 mRNA expression in kidney cortices by qPCR analysis (n = 5 for FVB WT, n = 8 for Tg26-control and n = 9 for Tg26-GS444217). (C) Quantification of the picrosirius red–stained area per field (n = 4 for FVB WT and Tg26-control, n = 8 for Tg26-GS444317; 16–20 fields were examined per mouse). ***P < 0.001 and ****P < 0.0001 when compared between indicated groups by ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test.

DISCUSSION

According to Global Health Observatory data, it is estimated that >37.9 million people globally were living with HIV infection at the end of 2018 [40]. Advances in antiretroviral therapy have substantially increased the survival of people living with HIV and decreased the prevalence of HIVAN. Indeed, a recent retrospective clinical and pathological analysis of the kidney biopsy findings in 437 HIV-positive patients collected between 2010 and 2018 at Columbia University Medical Center demonstrates a clear shift in the spectrum of HIV-associated kidney disease toward diverse immune complex glomerulonephritis, diabetic nephropathy and noncollapsing GS [41]. Nevertheless, HIVAN represented 14% of the diagnoses in this patient population rather than being eradicated [41].

Various studies have implicated the role of p38 and JNK signaling cascade in HIV-1 proviral expression and HIV-mediated cellular cytotoxicity and apoptosis [42–46]. Recently the inhibition of ASK1, an upstream regulator of p38 and JNK, was shown to reduce renal cell injury and fibrosis in various rodent experimental models [25]. Therefore, in this study, we sought to assess its effects in the mouse model of HIVAN, Tg26 mice.

Early histological studies of HIVAN kidneys have indicated that glomerular lesions precede tubulointerstitial changes, which are thought to predispose tubular cells to the ensuing injury, inflammation and renal fibrosis. This view is supported by experimental observations that the podocyte-specific expression of HIV-1 genes could recapitulate the full spectrum of HIVAN in mice [33, 47] and, conversely, the podocyte-specific deletion of STAT3 could mitigate both glomerular and tubulointerstitial damages in Tg26 mice [12]. In this study, the inhibition of ASK1 activation by GS-444217 led to significant preservation of podocyte foot process architecture and number, which likely accounts for the significant mitigation of albuminuria in GS-444217-treated Tg26 mice. Indeed, the prominent cPARP immunostaining that colocalizes with synaptopodin in Tg26 kidneys, suggesting an active involvement of cell death program in Tg26 podocytes, was largely abrogated in Tg26-GS-444217 kidneys. However, such an impact of ASK1 antagonism on albuminuria or podocyte loss was not observed in the experimental model of diabetes by Tesch et al. [23], even though it had improved renal function as assessed by serum cystatin-C levels . One possibility in these different observations is that the mechanisms of podocyte injury and ASK1 involvement may differ in HIVAN versus diabetic nephropathy, such that GS-444217 is more effective for podocyte survival in HIVAN than in diabetic nephropathy. Another possibility is that since GS-444217 treatment started in Tg26 mice at an early stage of HIVAN in our study, even though the albuminuria is detectable at this time point, its impact on podocyte injury and viability may be less efficacious in Tg26 mice with advanced HIVAN. Future studies are required to delineate between the role of ASK1 in podocyte injury between various glomerular diseases and to ascertain the effects of ASK1 antagonism on podocyte loss in advanced HIVAN.

Althoug subsequent to glomerular lesions, the tubular damage and ensuing inflammation are important contributors to HIVAN progression. Among the HIV-1 genes, Vpr has been implicated as one of the major culprits in glomerular and tubular damage in HIVAN [9, 33]. Vpr expression alone in cultured RTECs can lead to the activation of DNA damage response and inflammatory cascade, cell cycle arrest in G2/M checkpoint and apoptosis [36, 38, 39, 48]. The histopathological analysis showed that GS-444217 treatment attenuated the tubular atrophy and interstitial inflammation. In nonrenal cells, p38 MAPK was shown to induce G2/M arrest in response to DNA damage by activation of p53 [49–51] and by inhibition of Cdc25B that drives cell cycle progression [52]. Moreover, in the context of acute kidney injury, JNK or p53 inhibition has been shown to mitigate tubular injury and the ensuing fibrosis [53]. Thus it is plausible that the renoprotective effects of GS-444217 extend to the alleviation of cell cycle dysregulation in RTECs and subsequent induction of renal fibrosis. Indeed, GS-444217 led to a marked reduction in renal fibrosis in Tg26 mice. However, whether GS-444217 can indeed alleviate the Vpr-induced G2/M cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in RTECs in vivo remains to be determined.

Both in humans and HIV transgenic mouse models, the genetic background has a strong influence on the susceptibility of HIVAN development [54]. HIVAN occurs predominantly among HIV-infected individuals of African descent, which could be attributed to the polymorphism in apolipoprotein L1 (APOL1; G1 and G2 gene risk variants) [55, 56]. Although the mechanisms by which the APOL1 variants alter kidney cell function remain to be better elucidated, a recent study has linked the cytotoxic effects of APOL1 variant proteins as cation pores with the induction of p38 and JNK signaling cascade [57], and the inhibition of p38 or JNK significantly reduced the G1 or G2 APOL1-induced cytotoxicity and cell death in renal cells in vitro. Whether such APOL1 variant-mediated renal cell cytotoxicity and death is a driver of kidney disease progression in vivo and if ASK1 antagonism would similarly reduce APOL1 variant-mediated kidney injury remains to be explored, particularly since the APOL1 gene is restricted to human and a few other nonhuman primates and not expressed in widely used experimental rodent models of CKD, such as Tg26. But it is noteworthy that while the transgenic overexpression of the G2 variant specifically in podocytes of Tg26 mice did not worsen the HIVAN phenotype, the overexpression of the G0 nonrisk variant reduced podocyte loss and GS in Tg26 mice [58], suggesting that the nonrisk G0 may have a protective function against podocyte injury.

Recently ASK1 inhibition by GS-444217 has been shown in tubular injury and renal fibrosis in rodent models of UUO, I/R injury and DKD [25]. However, these models presented either acute tubular injury (UUO and I/R injury) or mild to moderate glomerular injury without significant progressive tubulointerstitial injury (DKD). Our current data in the Tg26 model demonstrate that interventional treatment with GS-444217 can preserve functional nephrons in a rapidly progressive model of both podocyte and tubular epithelial cell injury and provide further support for future human clinical trials in patients with CKD. Although a recent Phase 2 trial with the ASK1 inhibitor selonsertib (GS-4997, Gilead Sciences, NCT02177786) did not meet its primary endpoint of statistically significant change in estimated glomerular filtration rate from baseline to Week 48, the results were confounded by the acute effects related to inhibition of creatinine secretion by selonsertib [59]. A recent post hoc analysis accounting for these effects demonstrated that selonsertib resulted in a dose-dependent reduction in kidney function decline [59], suggesting a slowing of DKD progression. In summary, our current data in the murine HIVAN model along with the clinical dataset from the Phase 2 trial support further clinical development of selonsertib in patients with progressive glomerular filtration rate decline.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available at ndt online.

FUNDING

Funding for the project was provided by Gilead Sciences (Foster City, CA, USA). A.C. is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China(81800637), Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province (2019J01560) and the Xiamen Science and Technology Project (grant 3502Z20194014). J.C.H. is supported by a Veterans Affairs Merit Award and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK; R01DK078897, R01DK088541 and P01DK56492). K.L. is supported by the NIDDK (R01DK117913).

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

J.C.H. and K.L. designed the research project. A.C., J.X. and H.L. performed the experiments and acquired the data. V.D. performed histological scoring. A.C., J.X., T.-J.G., J.C.H. and K.L. analyzed the data. A.C., S.B., J.L., J.C.H. and K.L. drafted and revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

S.B. and J.L. are employees of Gilead Sciences. J.C.H. and K.L. received research reagents or financial support to conduct studies for Gilead Sciences.

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES

- 1. Winston JA, Klotman ME, Klotman PE. HIV-associated nephropathy is a late, not early, manifestation of HIV-1 infection. Kidney Int 1999; 55: 1036–1040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wyatt CM, Klotman PE, D’Agati VD. HIV-associated nephropathy: clinical presentation, pathology, and epidemiology in the era of antiretroviral therapy. Semin Nephrol 2008; 28: 513–522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Collins AJ, Kasiske B, Herzog C et al. Excerpts from the United States Renal Data System 2004 annual data report: atlas of end-stage renal disease in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis 2005; 45(Suppl 1): A5–7, S1–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Razzak Chaudhary S, Workeneh BT, Montez-Rath ME et al. Trends in the outcomes of end-stage renal disease secondary to human immunodeficiency virus-associated nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2015; 30: 1734–1740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Swanepoel CR, Atta MG, D’Agati VD et al. Kidney disease in the setting of HIV infection: conclusions from a Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) controversies conference. Kidney Int 2018; 93: 545–559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Berliner AR, Fine DM, Lucas GM et al. Observations on a cohort of HIV-infected patients undergoing native renal biopsy. Am J Nephrol 2008; 28: 478–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Medapalli RK, He JC, Klotman PE. HIV-associated nephropathy: pathogenesis. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 2011; 20: 306–311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Barisoni L, Kriz W, Mundel P et al. The dysregulated podocyte phenotype: a novel concept in the pathogenesis of collapsing idiopathic focal segmental glomerulosclerosis and HIV-associated nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 1999; 10: 51–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dickie P, Felser J, Eckhaus M et al. HIV-associated nephropathy in transgenic mice expressing HIV-1 genes. Virology 1991; 185: 109–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rosenstiel P, Gharavi A, D’Agati V et al. Transgenic and infectious animal models of HIV-associated nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 2009; 20: 2296–2304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fan Y, Wei C, Xiao W et al. Temporal profile of the renal transcriptome of HIV-1 transgenic mice during disease progression. PLoS One 2014; 9: e93019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gu L, Dai Y, Xu J et al. Deletion of podocyte STAT3 mitigates the entire spectrum of HIV-1-associated nephropathy. AIDS 2013; 27: 1091–1098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yuan Y, Huang S, Wang W et al. Activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator 1α ameliorates mitochondrial dysfunction and protects podocytes from aldosterone-induced injury. Kidney Int 2012; 82: 771–789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ratnam KK, Feng X, Chuang PY et al. Role of the retinoic acid receptor-alpha in HIV-associated nephropathy. Kidney Int 2011; 79: 624–634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. He JC, Husain M, Sunamoto M et al. Nef stimulates proliferation of glomerular podocytes through activation of Src-dependent Stat3 and MAPK1,2 pathways. J Clin Invest 2004; 114: 643–651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rosenberg AZ, Naicker S, Winkler CA et al. HIV-associated nephropathies: epidemiology, pathology, mechanisms and treatment. Nat Rev Nephrol 2015; 11: 150–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tesch GH, Ma FY, Nikolic-Paterson DJ. ASK1: a new therapeutic target for kidney disease. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2016; 311: F373–F381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shiizaki S, Naguro I, Ichijo H. Activation mechanisms of ASK1 in response to various stresses and its significance in intracellular signaling. Adv Biol Regul 2013; 53: 135–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tobiume K, Matsuzawa A, Takahashi T et al. ASK1 is required for sustained activations of JNK/p38 MAP kinases and apoptosis. EMBO Rep 2001; 2: 222–228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Takeda K, Matsuzawa A, Nishitoh H et al. Roles of MAPKKK ASK1 in stress-induced cell death. Cell Struct Funct 2003; 28: 23–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Terada Y, Inoshita S, Kuwana H et al. Important role of apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 in ischemic acute kidney injury. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2007; 364: 1043–1049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ma FY, Tesch GH, Nikolic-Paterson DJ. ASK1/p38 signalling in renal tubular epithelial cells promotes renal fibrosis in the mouse obstructed kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2014; 307: 1263–1273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tesch GH, Ma FY, Han Y et al. ASK1 inhibitor halts progression of diabetic nephropathy in NOS3-deficient mice. Diabetes 2015; 64: 3903–3913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Amos LA, Ma FY, Tesch GH et al. ASK1 inhibitor treatment suppresses p38/JNK signalling with reduced kidney inflammation and fibrosis in rat crescentic glomerulonephritis. J Cell Mol Med 2018; 22: 4522–4533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Liles JT, Corkey BK, Notte GT et al. ASK1 contributes to fibrosis and dysfunction in models of kidney disease. J Clin Invest 2018; 128: 4485–4500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Budas GR, Boehm M, Kojonazarov B et al. ASK1 inhibition halts disease progression in preclinical models of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2018; 197: 373–385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kopp JB, Klotman ME, Adler SH et al. Progressive glomerulosclerosis and enhanced renal accumulation of basement membrane components in mice transgenic for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1992; 89: 1577–1581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zhong Y, Wu Y, Liu R et al. Roflumilast enhances the renal protective effects of retinoids in an HIV-1 transgenic mouse model of rapidly progressive renal failure. Kidney Int 2012; 81: 856–864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Feng X, Lu TC, Chuang PY et al. Reduction of Stat3 activity attenuates HIV-induced kidney injury. J Am Soc Nephrol 2009; 20: 2138–2146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Koop K, Eikmans M, Baelde HJ et al. Expression of podocyte-associated molecules in acquired human kidney diseases. J Am Soc Nephrol 2003; 14: 2063–2071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mundel P, Gilbert P, Kriz W. Podocytes in glomerulus of rat kidney express a characteristic 44 kD protein. J Histochem Cytochem 1991; 39: 1047–1056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fan Y, Xiao W, Li Z et al. RTN1 mediates progression of kidney disease by inducing ER stress. Nat Commun 2015; 6: 7841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zhong J, Zuo Y, Ma J et al. Expression of HIV-1 genes in podocytes alone can lead to the full spectrum of HIV-1-associated nephropathy. Kidney Int 2005; 68: 1048–1060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Puelles VG, van der Wolde JW, Schulze KE et al. Validation of a three-dimensional method for counting and sizing podocytes in whole glomeruli. J Am Soc Nephrol 2016; 27: 3093–3104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hong Q, Zhang L, Das B et al. Increased podocyte Sirtuin-1 function attenuates diabetic kidney injury. Kidney Int 2018; 93: 1330–1343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ross MJ, Fan C, Ross MD et al. HIV-1 infection initiates an inflammatory cascade in human renal tubular epithelial cells. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2006; 42: 1–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rednor SJ, Ross MJ. Molecular mechanisms of injury in HIV-associated nephropathy. Front Med (Lausanne) 2018; 5: 177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Snyder A, Alsauskas ZC, Leventhal JS et al. HIV-1 viral protein r induces ERK and caspase-8-dependent apoptosis in renal tubular epithelial cells. AIDS 2010; 24: 1107–1119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rosenstiel PE, Gruosso T, Letourneau AM et al. HIV-1 Vpr inhibits cytokinesis in human proximal tubule cells. Kidney Int 2008; 74: 1049–1058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.World Health Organization. Global Health Observatory (GHO) data. https://www.who.int/gho/hiv/en/ (accessed 10 December 2019)

- 41. Kudose S, Santoriello D, Bomback AS et al. The spectrum of kidney biopsy findings in HIV-infected patients in the modern era. Kidney Int 2020; 97: 1006–1016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kumar S, Orsini MJ, Lee JC et al. Activation of the HIV-1 long terminal repeat by cytokines and environmental stress requires an active CSBP/p38 MAP kinase. J Biol Chem 1996; 271: 30864–30869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Muthumani K, Wadsworth SA, Dayes NS et al. Suppression of HIV-1 viral replication and cellular pathogenesis by a novel p38/JNK kinase inhibitor. AIDS 2004; 18: 739–748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Singh IN, El-Hage N, Campbell ME et al. Differential involvement of p38 and JNK MAP kinases in HIV-1 Tat and gp120-induced apoptosis and neurite degeneration in striatal neurons. Neuroscience 2005; 135: 781–790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Mangino G, Percario ZA, Fiorucci G et al. In vitro treatment of human monocytes/macrophages with myristoylated recombinant Nef of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 leads to the activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases, IκB kinases, and interferon regulatory factor 3 and to the release of beta interferon. J Virol 2007; 81: 2777–2791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Gangwani MR, Kumar A. Multiple protein kinases via activation of transcription factors NF-κB, AP-1 and C/EBP-δ regulate the IL-6/IL-8 production by HIV-1 Vpr in astrocytes. PLoS One 2015; 10: e0135633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zuo Y, Matsusaka T, Zhong J et al. HIV-1 genes vpr and nef synergistically damage podocytes, leading to glomerulosclerosis. J Am Soc Nephrol 2006; 17: 2832–2843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Payne EH, Ramalingam D, Fox DT et al. Polyploidy and mitotic cell death are two distinct HIV-1 Vpr-driven outcomes in renal tubule epithelial cells. J Virol 2017; 92: e01718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Bulavin DV, Kovalsky O, Hollander MC et al. Loss of oncogenic H-ras-induced cell cycle arrest and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase activation by disruption of Gadd45a Mol Cell Biol 2003; 23: 3859–3871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Huang C, Ma WY, Maxiner A et al. p38 kinase mediates UV-induced phosphorylation of p53 protein at serine 389. J Biol Chem 1999; 274: 12229–12235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Bulavin DV, Saito S, Hollander MC et al. Phosphorylation of human p53 by p38 kinase coordinates N-terminal phosphorylation and apoptosis in response to UV radiation. EMBO J 1999; 18: 6845–6854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Bulavin DV, Higashimoto Y, Popoff IJ et al. Initiation of a G2/M checkpoint after ultraviolet radiation requires p38 kinase. Nature 2001; 411: 102–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Yang L, Besschetnova TY, Brooks CR et al. Epithelial cell cycle arrest in G2/M mediates kidney fibrosis after injury. Nat Med 2010; 16: 535–543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Wyatt CM, Klotman PE. HIV-associated nephropathy: a case study in race and genetics. Am J Kidney Dis 2006; 47: 1084–1085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Genovese G, Friedman DJ, Ross MD et al. Association of trypanolytic ApoL1 variants with kidney disease in African Americans. Science 2010; 329: 841–845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Tzur S, Rosset S, Shemer R et al. Missense mutations in the APOL1 gene are highly associated with end stage kidney disease risk previously attributed to the MYH9 gene. Hum Genet 2010; 128: 345–350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Olabisi OA, Zhang JY, VerPlank L et al. APOL1 kidney disease risk variants cause cytotoxicity by depleting cellular potassium and inducing stress-activated protein kinases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2016; 113: 830–837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Bruggeman LA, Wu Z, Luo L et al. APOL1-G0 protects podocytes in a mouse model of HIV-associated nephropathy. PLoS One 2019; 14: e0224408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Chertow GM, Pergola PE, Chen F et al. Effects of selonsertib in patients with diabetic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 2019; 30: 1980–1990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.