Abstract

Background

Acute appendicitis is the most common cause of the acute abdomen, with an incidence of 1 per 1000 persons per year. It is one of the main differential diagnoses of unclear abdominal conditions.

Methods

This review is based on pertinent publications that were retrieved by a selective search in the PubMed and Cochrane Library databases.

Results

In addition to the medical history, physical examination and laboratory tests, abdominal ultrasonography should be performed to establish the diagnosis (and sometimes computed tomography [CT] or magnetic resonance imaging [MRI], if ultrasonography is insufficient). Before any treatment is provided, appendicitis is classified as either uncomplicated or complicated. In both types of appendicitis, the decision to treat surgically or conservatively must be based on the overall clinical picture and the patient’s risk factors. Appendectomy is the treatment of choice for acute appendicitis in all age groups. In Germany, appendectomy is mainly performed laparoscopically in patients with low morbidity. Uncomplicated appendicitis can, alternatively, be treated conservatively under certain circumstances. A meta-analysis of five randomized, controlled trials has revealed that ca. 37% of adult patients treated conservatively undergo appendectomy within one year. Complicated appendicitis is a serious disease; it can also potentially be treated conservatively (with antibiotics, with or without placement of a drain) as an alternative to surgical treatment.

Conclusion

Conservative treatment is being performed more frequently, but the current state of the evidence does not justify a change of the standard therapy from surgery to conservative treatment.

Appendectomy is among the more commonly performed operations in Germany, with more than 108 000 procedures per year (1). Acute appendicitis has an incidence of 100 new cases per 100 000 persons per year and is the most common cause of the acute abdomen (2, 3). The lifetime risk of acute appendicitis is slightly higher in men than in women (8.6% versus 6.7%), but women have a higher lifetime risk of undergoing appendectomy (23.1% versus 12.0%) (4). Adolescent girls (age 12–16) are the group at greatest risk for appendectomy (5). In Germany, laparoscopic appendectomy is universally available and has become the usual treatment, replacing conventional appendectomy. Approximately 25% of appendectomies in children are performed by open surgery, there being as yet no unequivocal evidence for the superiority of the laparoscopic approach (3, 5). Appendectomy is associated with very low surgical risk; the morbidity and mortality of patients who have undergone appendectomy is largely determined by the severity of the appendicitis itself and its comorbidities (3, 6). The vermiform appendix plays a physiological role as a reservoir for the intestinal flora (intestinal microbiome), e.g., after antibiotic treatment, as well as the site of origin of mesenchymal stem cells in the colon (7– 9). Three guidelines on appendicitis have been published to date internationally (10– 12), but none yet in Germany.

Incidence.

Acute appendicitis has an incidence of 100 new cases per 100,000 persons per year and is the most common cause of the acute abdomen.

Surgical risk.

Appendectomy is associated with very low surgical risk; the morbidity and mortality of patients who have undergone appendectomy is largely determined by the severity of the appendicitis itself and its comorbidities.

Method

A selective literature search was carried out in the PubMed and Cochrane Library databases, with the search terms “acute appendicitis,” “acute appendicitis diagnostics,” “acute appendicitis therapy,” “appendectomy,” “uncomplicated appendicitis,” “complicated appendicitis,” “appendicitis in children,” and “appendicitis in adults.”

Learning objectives

This article should enable the reader to:

distinguish uncomplicated and complicated appendicitis

know the diagnostic and therapeutic options in acute appendicitis in children and adults.

Classification

Appendicitis is defined as an inflammation of the vermiform appendix. The European Association of Endoscopic Surgery (EAES) classifies acute appendicitis as either “uncomplicated” or “complicated” (12). Uncomplicated appendicitis is defined as inflammation in the absence of phlegmon, gangrene, free purulent fluid, or an abscess. Complicated appendicitis is accompanied by a periappendiceal phlegmon with or without perforation, gangrene, or a perityphlitic abscess (table 1).

Table 1. Overview of critieria for uncomplicated vs. complicated appendicitis, adapted from those of the European Association of Endoscopic Surgery (EAES), 2016 (12), and of diagnostic measures in suspected acute appendicitis.

| Uncomplicated | Complicated | |

| Criteria for uncomplicated vs. complicated appendicitis | ||

| Inflammation | + | + |

| Gangrene | − | + |

| Phlegmon | − | + |

| Perityphlitic abscess | − | + |

| Free fluid | − | + |

| Perforation | − | + |

| Diagnostic measures | ||

| History | + | + |

| Physical examination, including appendicitis pressure points | + | + |

| Digital rectal examination | − | − |

| Laboratory tests | + | + |

| Body temperature measurement | + | + |

| Urine test strip and pregnancy test*1 | + | + |

| Gynecological consultation | ± | ± |

| Abdominal ultrasonography*2 | + | + |

| Computed tomography | − | ± |

| Magnetic resonance imaging | − | ± |

+ yes; - no; ± possible

Complicated appendicitis is present, by definition, if any criterion in addition to inflammation is met.

*1 In female patients of child-bearing age; *2 method of first choice.

Diagnostic evaluation

Cases of acute appendicitis vary widely in their clinical presentation, and the diagnosis is made more difficult by a multiplicity of differential diagnoses. Acute appendicitis has been called the chameleon of surgery (13). Up to half of all cases in children present with nonspecific symptoms. There is a wide range of differential diagnoses depending on age; the incidence peak is during the primary-school years and adolescence (table 2) (4, 14, 15). In our view, appendicitis should already be classified before treatment as either uncomplicated or complicated, in order to enable stage-appropriate treatment.

Table 2. Modified list of differential diagnoses of appendicitis in childhood and adolescence, after Stundner-Ladenlauf and Metzger (e57).

| Children and adolescents in general | Infants and children <6 years old | 6 –12 years old | > 12 years old |

| – constipation – gastroenteritis – ileus – pneumonia – urinary tract infection – trauma – abuse |

– volvulus – intussusception – malrotation – colic – testicular torsion – epididymitis – inguinal hernia – Hirschsprung’s disease – constipation |

– functional abdominal pain – testicular or ovarian torsion – epididymitis – Henoch-Schönlein purpura – intussusception – volvulus |

– ovarian torsion – testicular torsion – ovarian cyst – ovulatory pain – extrauterine pregnancy – infectious monomucleosis – chronic inflammatory bowel diseases |

History, physical examination, and laboratory tests

The state of the evidence.

Three guidelines on appendicitis have been published to date internationally, but none yet in Germany.

Clinical presentation.

Acute appendicitis has a highly variable clinical presentation and has therefore been called the chameleon of surgery.

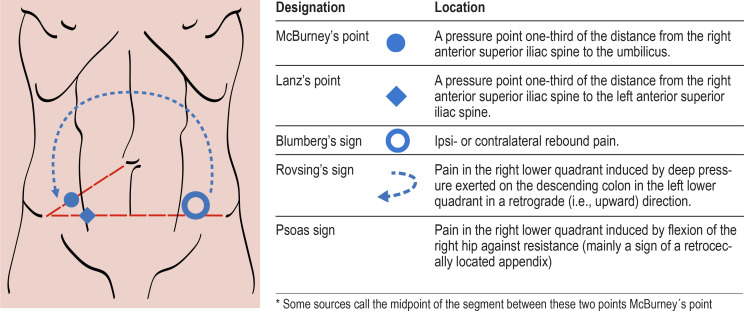

The patient should always be asked about the time of onset of symptoms and the site of the pain, as well as the past medical history and current medications (table 1). A change in the localization of pain from the upper abdomen to the right lower quadrant is often associated with appendicitis (16). In children and adolescents, the history and physical examination should be adapted to the patient’s age and developmental stage. The experience of the examiner is important, particularly when the patient is a small child. Appropriate analgesic medication does not mask the physical findings to any relevant extent (17). In children, the absence of nausea and vomiting, abdominal tenderness, and leukocytosis rules out appendicitis with 98% reliability (18). In pregnant women, the appendix may be cranially displaced by the enlarged uterus, with the result that pain is felt in the upper abdomen, rather than the right lower quadrant; this can make the diagnosis more difficult. Whenever acute appendicitis is suspected, physical examination for the known signs of appendicitis is mandatory (Figure, Table 1) in addition to blood tests (19).

Figure.

A diagram of the pain and pressure points to be checked when acute appendicitis is suspected.

Local guarding in the right lower abdominal quadrant indicates irritation of the parietal peritoneum, while diffuse guarding indicates a severe, complicated case of appendicitis. Leukocytosis/neutrophilia and an elevated serum concentration of C-reactive protein (CRP) are considered nonspecific signs of inflammation (20, 21). Procalcitonin plays no role in routine diagnostic testing (22, 23). The body temperature should be measured, and a simple urinalysis with a test strip should be performed, as should a pregnancy test in girls and women of child-bearing age (20). These measures serve to rule out a number of differential diagnoses of right lower quadrant pain, for example, urolithiasis, urinary tract infection, or an ectopic pregnancy. Gynecological consultation should be obtained for stable female patients with unclear clinical presentations in whom the diagnosis remains uncertain. A digital rectal examination is of low diagnostic yield and need not be performed (24).

Scoring systems

Findings on palpation.

Local guarding in the right lower abdominal quadrant indicates irritation of the parietal peritoneum, while diffuse guarding indicates a severe, complicated case of appendicitis.

A variety of scoring systems have been developed for the purpose of investigating and objectifying a suspected diagnosis of acute appendicitis independently of the clinical experience of the examiner. The most commonly used ones are the Alvarado score (1986) and the Appendicitis Inflammatory Response (AIR) score (2008) (table 3) (6). The criterion of an Alvarado score ≥ 5 diagnoses appendicitis with 99% sensitivity, but only 43% specificity; setting the threshold higher (≥ 7) leads to increased specificity (81%), at the cost of lower sensitivity (82%). The Alvarado score, therefore, is most useful for ruling out appendicitis, rather than diagnosing it. In contrast, an AIR score >8 is both highly sensitive and highly specific (99%) for appendicitis (6, 11). In Germany, scoring systems like these are not generally used as an aid to diagnosis in routine clinical practice.

Table 3. Modified summary of the Alvarado (e58) and AIR scores (e59) for evaluating the possible presence of appendicitis.

| Criterion | Alvarado Score | AIR Score | |

| Symptoms | |||

| Vomiting | – | 1 | |

| Nausea or vomiting | 1 | – | |

| Anorexia | 1 | – | |

| RLQ pain | 2 | 1 | |

| Migratory RLQ pain | 1 | – | |

| Signs | |||

| RLQ rebound pain or guarding | 1 | – | |

| mild | – | 1 | |

| moderate | – | 2 | |

| severe | – | 3 | |

| Body temperature | >37.5°C | 1 | – |

| >38.5°C | – | 1 | |

| Laboratory parameters | |||

| Leukocyte count | >10 000/L | 2 | – |

| 10 000–14 900/L | – | 1 | |

| >15 000/L | – | 2 | |

| Leukocyte shift | 1 | – | |

| PMN granulocytes | 70–84% | – | 1 |

| ≥ 85% | – | 2 | |

| CRP value | 10–49 mg/L | – | 1 |

| ≥ 50 mg/L | – | 2 | |

| Sum | 10 | 12 | |

| Alvarado score | <5 | low probability | |

| 5–6 | unclear | ||

| 7–8 | likely | ||

| >8 | high probability | ||

| AIR score | <5 | low probability | |

| 5–8 | intermediate probability | ||

| >8 | high probability | ||

AIR, Appendicitis Inflammatory Response; CRP, C-reactive protein;

RLQ, right lower abdominal quadrant; PMN, polymorphonuclear.

Imaging

Ultrasonography, CT, and MRI are all used in the evaluation of suspected acute appendicitis. Ultrasonography is the method of first choice, particularly for children (25). It has the disadvantage that its diagnostic benefit depends on the examiner’s experience, and a negative finding may not suffice to rule out appendicitis (sensitivity 71–94%, specificity 81–98%) (12, 26). In children, its sensitivity and specificity are higher: sensitivity 96% [83–99%], specificity 100% [87–100%] (25).

Imaging techniques.

Abdominal ultrasonography is the imaging method of first choice for confirming a diagnosis, or evaluating a suspected diagnosis, of acute appendicitis.

CT is superior to ultrasonography (sensitivity 76–100%, specificity 83–100%) (12), yet its role in the evaluation of suspected acute appendicitis is a matter of controversy in Western countries, and it is used to a variable extent depending on location. In the USA, CT is routinely performed in 20–95% of patients, presumably contributing to the less than 5% rate of negative appendectomies (removal of a histopathologically normal appendix) (27– 29). In Europe, on the other hand, the diagnosis is often made on clinical grounds, and there is a higher laparoscopy rate as well as a higher rate of negative appendectomies (up to 32%) (30, 31). The use of low-dose rather than conventional CT does not significantly affect the negative appendectomy rate (difference 0.3%, 95% confidence interval [-3.8; 4.6]); avoiding the administration of oral contrast medium and giving intravenous contrast medium lowers radiation exposure while preserving diagnostic sensitivity (95% versus 92%) (32– 36). Nonetheless, even though CT is both highly sensitive and highly specific, it may not be able to distinguish complicated from uncomplicated appendicitis. In obese persons (BMI >30 kg/m2), the ultrasonographic signs of appendicitis are hard to evaluate; CT is performed more often in this patient group (12). The same holds for persons over age 65, because their symptoms are usually atypical, and because increasing age is associated with higher comorbidity and thus also with a broader differential diagnosis.

Obesity.

In obese persons (BMI >30 kg/m2), the ultrasonographic signs of appendicitis are hard to evaluate; CT is performed more often in this patient group.

MRI, compared to CT, has comparable sensitivity (97 versus 76–100%) and specificity (95 versus 83–100%) for the diagnosis of acute appendicitis (12), but it is not universally available in an emergency. MRI is a safe alternative to CT for children and pregnant women, as it does not involve ionizing radiation, and is thus preferable to CT, in our view, if the ultrasonographic findings are equivocal (37). Children under age 5 often require sedation or general anesthesia for MRI to be performed.

Treatment

Guidelines and literature

Children and pregnant women.

MRI is a safe alternative to CT for children and pregnant women, as it does not involve ionizing radiation, and is thus preferable to CT, in our view, if the ultrasonographic findings are equivocal.

According to the World Society of Emergency Surgery (WSES), the Society of Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES), and the European Association for Endoscopic Surgery (EAES), appendectomy is the treatment of choice for uncomplicated acute appendicitis in all age groups (10– 12). Harrison, in 1953, was the first to propose conservative treatment for acute appendicitis (38). A few authors reported spontaneous cures (39). Now that many publications have documented the successful conservative treatment of uncomplicated appendicitis with antibiotics in childhood and adulthood, this approach is attracting increased attention (12, 40, e1– e3). In a recent meta-analysis, children and adolescents with uncomplicated appendicitis who were treated conservatively became free of symptoms in 92% ([88; 96]) of cases, although 16% (10–22%) went on to undergo appendectomy because of a recurrence (follow-up: 8 weeks to 4.5 years) (e3). Another meta-analysis, in 2016, showed no difference with regard to complications or length of hospital stay (e4). In a comparative analysis, Kessler et al. found that conservative management in childhood led to a higher hospital readmission rate (relative risk [RR] 6.98; [2.07; 23.6]) and a lower rate of becoming free of symptoms (RR 0.77; [0.71; 0.84]) (e5). Because the studies analyzed in these publications were not randomized and recruited fewer patients than would have been desirable, it can practically be assumed that the children were more likely to be treated conservatively if they were less clinically ill. The follow-up was inadequate as well, as shown by 5-year follow-up studies both in children (appendectomy rate five years after primary conservative treatment of uncomplicated appendicitis: 46%) (e6) and in adults (APPAC trial appendectomy rates of 27% and 39% at one and five years, respectively) (e7, e8). Moreover, in the APPAC trial, the non-inferiority criterion for antibiotic treatment was not met at one year. In all three of the analyses mentioned above, the state of the evidence is insufficient to justify a change of clinical strategy, although conservative treatment can be regarded as safe (e3– e5). In a meta-analysis of five randomized and controlled trials published in 2019, appendectomy was found to be the more effective method for the definitive treatment of uncomplicated appendicitis in adulthood (37.4% appendectomy rate within one year after conservative treatment; treatment effectiveness [i.e., lack of recurence or appendectomy] with at least one year of follow-up, 62.6% versus 96.3% in the surgical group, RR 0.65 [0.55; 0.76]) (e9). Current evidence is insufficient to enable the detection of any advantage for conservative treatment, and surgery thus remains the treatment of choice for acute uncomplicated appendicitis in both children and adults (e3). The potential long-term adverse effects of conservative treatment (drug side effects, antibiotic resistance) have not been adequately described to date and will be studied in upcoming trials (APPAC-III, MAPPAC) (e10, e11).

For all these reasons, the rest of this article will deal mainly with the surgical treatment of acute uncomplicated and complicated appendicitis in children and adults.

Laparoscopy

The treatment of choice.

Appendectomy is the treatment of choice for uncomplicated acute appendicitis in all age groups.

Conservative treatment.

Current evidence is insufficient to enable the detection of any advantage for conservative treatment of acute uncomplicated appendicitis.

In Germany, appendectomy is now performed laparoscopically as a standard. The reasons for this are the shorter hospital stay, lower wound infection rate, and lower morbidity (1.5% versus 11.9% for wound-healing disturbances) and mortality (0.1 versus 1.2%) compared to open surgery, although the negative selection of seriously ill patients must be taken into account (3). Laparoscopy enables abdominal exploration to rule out various differential diagnoses, e.g., adnexitis and Meckel’s diverticulitis. It remains controversial whether a macroscopically normal appendix should be removed if no alternative diagnosis can be made, just as conservative treatment remains controversial (12, e12, e13). In our view, incidental appendectomy can be performed if there is no contraindication. In 18–29% of cases, histological study reveals appendicitis or another type of appendiceal pathology, such as endometriosis (0.0–0.9%), neoplasia (0.23–1.2%), or obstruction by an appendicolith (2.7–6.0%) or parasites (1.2–2.5%), despite a macroscopically normal appendix (e14, e15).

Complicated appendicitis

There is no standard evidence-based approach to the treatment of complicated acute appendicitis. In principle, it can either be treated with urgent surgery or managed conservatively (i.e., with antibiotics alone or with the interventional placement of a drain). Certainly, the clinical condition of the patient and any risk factors that are present should be taken into account in deciding upon the treatment (12). Moreover, if conservative management is adopted, the associated risks must be borne in mind (e16, e17). In Germany, the usual treatment is immediate appendectomy (3). The EAES and WSES have not defined any clear way to proceed in the management of complicated appendicitis (11, 12). They consider initial conservative management a possible option but point out the need for further studies to clarify the role of interval appendectomy, i.e., appendectomy during an inflammation-free interval (12). The WSES recommends primary conservative treatment for an abscess or phlegmon, with the comment that laparoscopy is a feasible alternative (11). Internationally, there is increasing evidence in favor of conservative treatment for complicated appendicitis (mixed meta-analysis: 17 retrospective studies, one prospective study, and three randomized, controlled trials), with low rates of complications (odds ratio [OR] 3.16; [1.73; 5.79], intra-abdominal retentions (OR 3.13; [1.18; 8.3]), and wound infections (OR 3.95; [1.95; 8.00]) compared to surgery. The subgroup analysis of the included randomized, controlled trials did not reveal any significant difference in intra-abdominal retentions (OR 0.46; [0.17; 1.29]) between conservative and laparoscopic treatment. On the other hand, these high-quality randomized and controlled trials did show laparoscopic appendectomy to be associated with a hospital stay that was one day shorter (mean difference [MD] -0.99; [-1.31; –0.67]), without any elevation of the complication rate (e18). Another meta-analysis (three randomized, controlled trials [RCTs] and four controlled clinical studies) favored immediate laparoscopic surgery for appendicitis in the presence of an abscess, rather than conservative management, because of a higher rate of unproblematic recovery (OR 11.91; [4.59; 30.88]), a shorter hospital stay (weighted MD: -2.98; [-5.96; -0.01]), and fewer recurrent abscesses (OR 0.07; [0.3; 0.20]) (e19). Future studies will be needed to determine what treatment is truly best for complicated appendicitis in consideration of the patient’s risk factors and clinical condition. It has been suggested that interval appendectomy might be best reserved for symptomatic patients (e21), in view of the associated higher conversion rate (1.9 versus 0.13%; p <0.001), and higher rates of intraoperative complications (2.8% versus 0.3%; p <0.001) and intra-abdominal retentions (4.7 versus 1.2%, p = 0.003) (e20).

The management of a perityphlitic abscess (drainage before surgery)

In view of the heterogeneous data that are currently available, there is no uniform, evidence-based way to proceed when a perityphlitic abscess is demonstrated (e16– e19, e22). In this situation, we recommend risk-stratified interdisciplinary management, depending on size. A macroabscess can be treated with the interventional placement of a drain combined with antibiotic treatment and, depending on the further course, an interval appendectomy. A microabscess can be treated with immediate surgery, because puncturing the abscess is generally not technically feasible.

The timing of surgery

Perityphlitic abscess.

Perityphlitic abscesses should be managed by an interdisciplinary team in risk-stratified fashion, depending on size. A macroabscess can be treated with interventional drain placement combined with antibiotic treatment and, depending on the further course, an interval appendectomy.

Microabscess.

A microabscess can be treated with immediate surgery, because puncturing the abscess is generally not technically feasible.

It was once the rule to operate on acute appendicitis as rapidly as possible to avoid perforation and the ensuing complications (12). To date, however, there have been no randomized, controlled trials on this topic. Certain observations—such as a lower risk of perforation with a longer wait before surgery—may well be related to bias in the evidence, because patients who are clinically more severely ill (those with perforation or complicated appendicitis) have tended to be given priority for rapid surgery (e23, e24). In a Swedish multicenter study involving 1675 patients, the perforation rate only rose significantly 12, 18, and 24 hours after admission to the hospital (e23). Accordingly, in a study from the USA, surgery at a delay of more than 12 hours was associated with a longer length of hospital stay (44.6 versus 34.5 hours) and increased costs (e25). In an American study of 857 children in whom the initial CT revealed no evidence of perforation, a weak association was found between triage (i.e., a delay) till the incision was made and the intraoperative finding of a perforation (adjusted odds ratio 1.02 [1.00; 1.04] per hour of delay) (e26). It is also concluded in the up-to-date meta-analysis of Li et al. that a brief (<12-hour) delay is not associated with complicated appendicitis, but that there is nonetheless a progressively strong association between the time since the onset of symptoms, or since hospital admission, and the likelihood of perforated appendicitis—the odds ratio is 1.84 ([1.05; 3.21]) at 24 hours and 7.57 at 48 hours ([6.14; 9.35]) (e27). In adults, delaying appendectomy by 12–24 hours from the time of diagnosis, while giving antibiotics, does not increase the perforation rate (e28– e30). The operation should not be delayed by more than 12 hours for patients with comorbidities or who are age 65 or older. Appendectomy more than 48 hours after diagnosis is associated with a higher surgical infection rate (adjusted OR 2.24; p = 0.039) (e31). In view of the heterogeneous evidence base that is currently available, we recommend a risk-stratified approach. A delay of up to 12 hours in children or 24 hours in adults while antibiotics are given seems not to elevate the morbidity of patients with uncomplicated appendicitis to any relevant extent.

Adequate data are lacking concerning the appropriate timing of surgery for complicated appendicitis; the timing of surgery depends on the findings (phlegmon, free fluid, abscess) and on the patient’s clinical condition and comorbidities. In a meta-analysis comparing conservative and surgical treatment of complicated appendicitis with a free perforation in children, based on two randomized, controlled trials and twelve observational studies, the surgical group experienced significantly fewer complications (RR 1.86; [1.20; 2.87]) and hospital readmissions (RR 3.33; [1.49; 7.44]) (e32). We do not know of any comparable study in adults, but one study has shown that the timing of surgery is correlated with survival (e33). Thus, whenever free intraperitoneal air is seen, in a child or adult patient, surgery should be performed urgently.

Antibiotics

The conservative treatment of acute appendicitis is based on the administration of antibiotics (Cochrane Review: 45 studies, including RCTs and CCTs) (e34). A cephalosporin combined with a nitroimidazole (usually metronidazole) is most commonly used, followed by a penicillin with a beta-lactamase inhibitor and by quinolones. The evidence base is derived from the WSES guideline and a prospective, worldwide multicenter observational study (6, 11). Antibiotics are usually given parenterally for one to three days and then orally for a further 5–7 days (11, e21). The optimal duration of treatment is not clear; the length of treatment generally depends on the clinical course and the normalization of inflammatory parameters (12). Antibiotics should be given perioperatively as part of the treatment of any type of appendicitis (11, e34). A meta-analysis of 12 randomized, controlled trials and one Cochrane Review (47 studies) showed that perioperative antibiotics can lower both the rate of wound infections (Peto OR: 0.33; [0.29; 0.38]) and the abscess incidence (Peto OR: 0.43; [0.25; 0.73]) (e35). Continuing the antibiotics postoperatively is recommended in complicated appendicitis, particularly in case of an abscess, peritonitis, or free perforation (e35).

Postoperative and other complications

Therapeutic decision-making in acute appendicitis in persons belonging to special risk groups.

Conservative treatment has a higher risk of failure in patients with a demonstrated appendicolith, obesity (BMI >30 kg/m2), age over 65, or immune suppression or acquired immune deficit, as well as in pregnant women.

Delayed appendectomy.

In adults with uncomplicated acute appendicitis, delaying appendectomy by 12 to 24 hours from the time of diagnosis, while giving antibiotics, does not lead to an increased rate of perforation.

The overall rate of postoperative complications after appendectomy in Germany has been reported as up to 2.1% (e36). Postoperative complications can be categorized as early or late. The former include wound infection, hemorrhage, abdominal wall abscess, and appendiceal stump insufficiency, as well as intra-abdominal retentions (Douglas or loop abscess). The latter include incisional hernias, intra-abdominal adhesions possibly causing bowel obstruction, and stump appendicitis. Whenever a postoperative complication is suspected, the patient should be re-examined by the operating surgeon, and further diagnostic studies should be undertaken including laboratory testing and abdominal ultrasonography.

Patient information on the conservative treatment of appendicitis should include the fact that the incidence of bowel cancer is slightly higher than in the normal population (Swedish population cohort study, SIR: 4.1 [3.7; 4.6]) (e37). Nor is there yet any definitive information from RCTs on the possible risk of adhesion formation, or the potentially higher probability of infertility, after conservative treatment. A Swedish study employing a historical cohort for comparison did not reveal any higher frequency of infertility after perforated appendicitis in childhood than after appendectomy of an unperforated, or even healthy, appendix (e38).

In 0.5% of children who undergo appendectomy, histopathological study of the surgical specimen reveals a neuroendocrine tumor of the appendix, a so-called appendiceal carcinoid, as an incidental finding (e39). Depending on the size of the tumor, more extensive surgery, such as an ileocecal resection or a hemicolectomy, may be necessary. The further course of treatment should always be decided upon in collaboration with a pediatric oncologist (e40).

Risk groups

Therapeutic decision-making should also take certain special risk groups into consideration. According to the pertinent literature, conservative treatment has a higher risk of failure, and correspondingly higher morbidity, in patients with a demonstrated appendicolith (e41), obesity (BMI > 30 kg/m2) (e42), age over 65 (e43– e47), or immune suppression or acquired immune deficit (e48), as well as in pregnant women (e49– e51) (12). The demonstration of an appendicolith on an imaging study is highly likely to be followed by the failure of conservative treatment (Mantel-Haenszel estimator RR: 10.43 [1.46; 74.26] (e41). Thus, these patients should be treated with early appendectomy (eCase Illustration with eFigures 1 and 2).

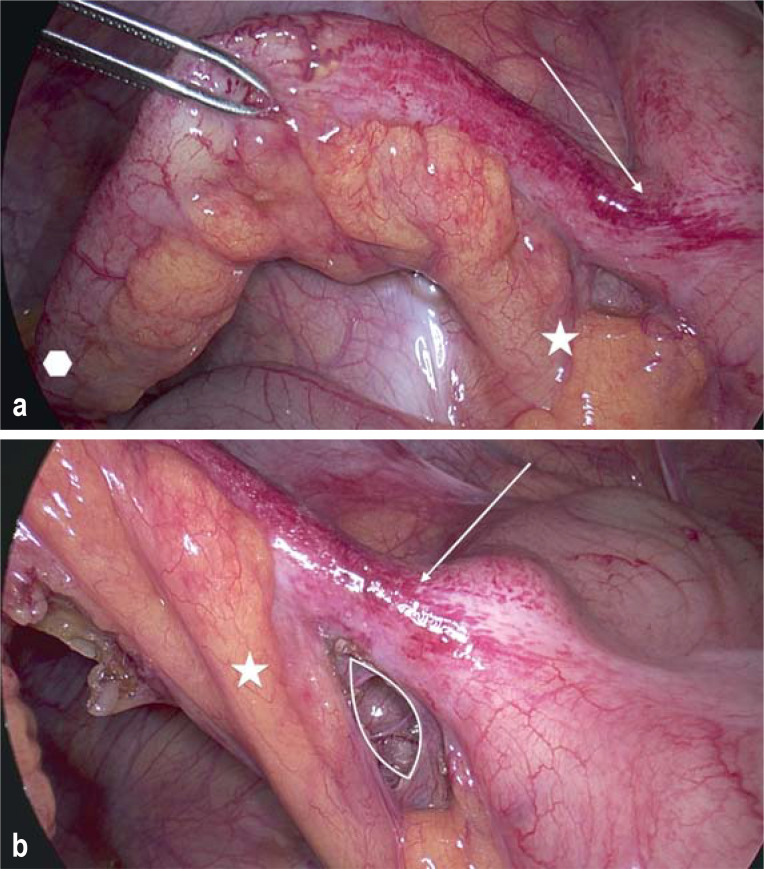

eFigure 1.

a) intraoperative view a) before and b) after exposure.

Arrow: base of appendix; polygon: tip of appendix, star: mesoappendix; white border: window created in the mesoappendix.

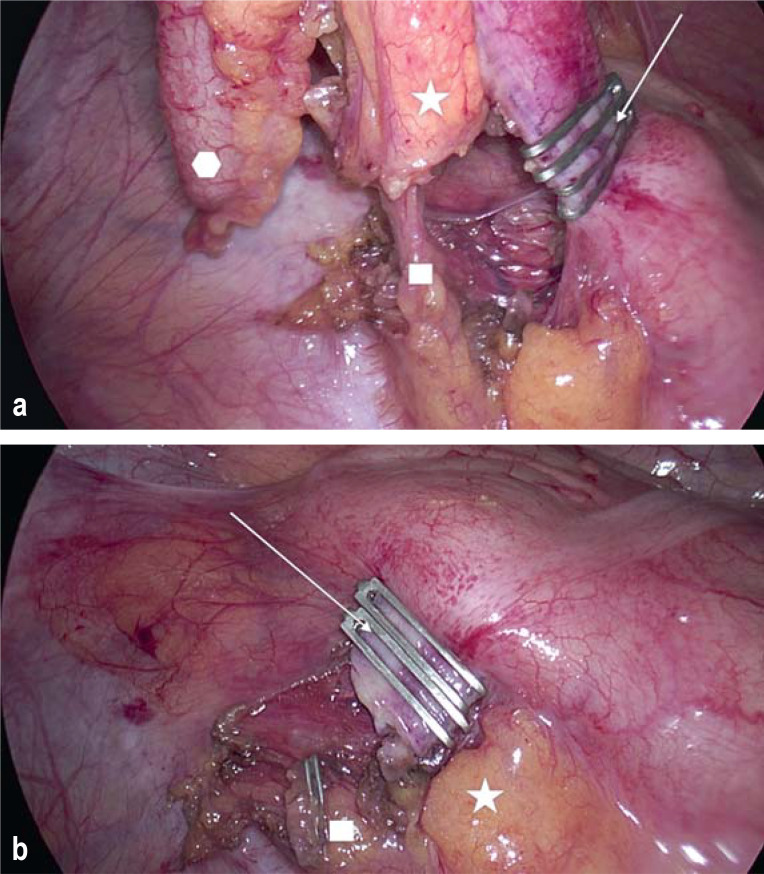

eFigure 2.

intraoperative view after a) clipping and b) division of the main structures.

Arrow: base of appendix; polygon: tip of appendix, star: mesoappendix; rectangle: appendicular artery.

Overall postoperative complication rate.

The overall rate of postoperative complications after appendectomy in Germany has been reported as up to 2.1%.

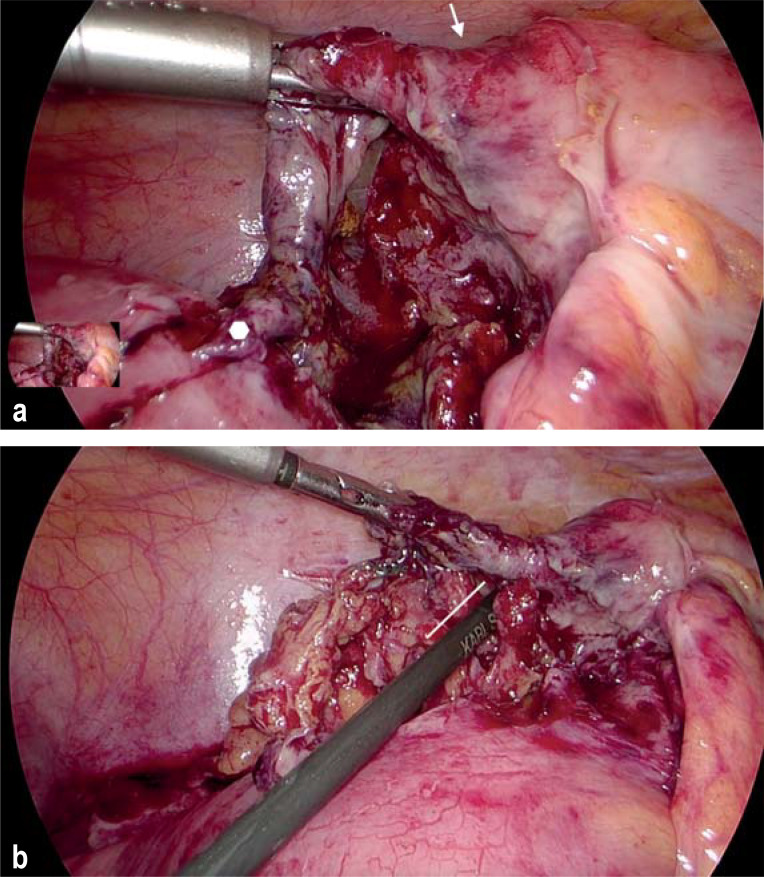

In this patient collective, high leukocyte counts and CRP values are correlated with the risk of gangrenous appendicitis (Figures 1a and b). Laparoscopic appendectomy is considered a safe treatment in this situation as well (12, e52). In pregnancy, too, acute appendicitis is the most common cause of the acute abdomen, and spontaneous abortion is its most feared complication (e53). Miscarriage is more common in complicated appendicitis than in uncomplicated appendicitis (20% versus 1.5%) (e54, e55). The threshold for operating should, therefore, be set low; appendectomy can be carried out safely in all three trimesters (e56).

Figure 1.

Intraoperative view of gangrenous appendicitis

a) after exposure and b) before removal with a stapler.

Arrow: base of appendix; polygon: tip of appendix;

line: parallel to the dissector with which the surgeon is checking the freely exposed window of the mesoappendix.

Discussion

In the diagnosis and treatment of acute appendicitis in childhood and adulthood, there is increasing discussion of the possibility of nonsurgical treatment, of the optimal timing of surgery, and of the appropriate postoperative care (12, 40, e1, e2). Nonetheless, the available evidence base does not suffice to justify a change from primarily surgical treatment, in either children or adults (e3, e5, e9). Moreover, there have not yet been any randomized, placebo-controlled, blinded trials investigating the long-term course with regard to the undesired side effects of conservative treatment; such trials are to begin soon (e10, e11). Thus, appendectomy remains the treatment of choice for uncomplicated acute appendicitis in all age groups (10– 12). In adults with uncomplicated acute appendicitis, delaying appendectomy by 12 to 24 hours from the time of diagnosis, while giving antibiotics, does not lead to an increased rate of perforation (e28– e30). Surgery should not, however, be delayed by more than 12 hours in children and adolescents, patients over age 65, or patients with comorbidities (e23– e27, e31).

Appendicitis and pregnancy.

In pregnancy, too, acute appendicitis is the most common cause of the acute abdomen, and spontaneous abortion is its most feared complication.

Complicated acute appendicitis is a severe illness that can be managed conservatively, as an alternative to surgical treatment, under certain circumstances. The state of the evidence regarding the morbidity and efficacy of conservative management is mixed (e18, e19, e32). Future studies will be needed for a definitive determination of the best way to treat complicated appendicitis in consideration of the patient’s risk factors and clinical condition.

The timing of surgery.

Surgery should not be delayed by more than 12 hours in children and adolescents, patients over age 65, or patients with comorbidities.

Supplementary Material

eCase illustration

A 22-year-old man presented to the emergency department complaining of feeling unwell since the morning, with a migrating pain in the right lower abdominal quadrant. The further history was negative with respect to past medical illnesses, past operations, medications taken, and allergies. Laboratory tests revealed a leukocytosis of 22 000/L, a core body temperature of 37.6°C, and an unremarkable urine test strip. Physical examination revealed incipient peritoneal signs in the right lower quadrant, without guarding but with positive appendicitis pressure points and contralateral rebound pain. Ultrasonography revealed a small amount of periappendicular echo-free fluid without any circumscribed mass. The appendix was 9 mm in diameter, and an appendicolith was seen ultrasonographically. In view of the free fluid and the overall clinical picture, the patient was deemed to have a complicated case of appendicitis. After extensive discussion with the patient, and because of the likelihood that conservative treatment would fail, a decision was taken to perform a laparoscopic appendectomy. Perioperatively, the patient was given antibiotic treatment based on a cephalosporin and a nitroimidazole, and surgery ensued within 12 hours of the diagnosis. The intraoperative findings confirmed acute appendicitis. A laparoscopic appendectomy with clip application was performed. eFigure 2 shows the intraoperative view before and after exposure of the base of the appendix. eFigure 2 shows the twofold clip application at the base of the appendix, as well as the freely dissected appendicular artery before and after the artery was clipped and its distal portion removed together with the appendix itself. No further antibiotics were given postoperatively. The patient was discharged home on the second postoperative day after an uneventful course, feeling well and with an unremarkable abdominal examination.

Further information on CME.

Participation in the CME certification program is possible only over the Internet: cme.aerzteblatt.de. This unit can be accessed until 5 November 2021. Submissions by letter, e-mail or fax cannot be considered.

Once a new CME module comes online, it remains available for 12 months. Results can be accessed 4 weeks after you start work on a module. Please note the closing date for each module, which can be found at cme.aerzteblatt.de.

This article has been certified by the North Rhine Academy for Continuing Medical Education. Participants in the CME program can manage their CME points with their 15-digit “uniform CME number” (einheitliche Fortbildungsnummer, EFN), which is found on the CME card (8027XXXXXXXXXXX). The EFN must be stated during registration on www.aerzteblatt.de (“Mein DÄ”) or else entered in “Meine Daten,” and the participant must agree to communication of the results.

CME credit for this unit can be obtained via cme.aerzteblatt.de until 5 November 2021.

Only one answer is possible per question. Please select the answer that is most appropriate.

Question 1

Which of the following can be present in either of the two types of appendicitis (complicated and uncomplicated)?

perforation

phlegmon

inflammation

gangrene

abscess

Question 2

What is an important differential diagnosis of appendicitis in women and girls of child-bearing age?

adnexitis

endometriosis

coprostasis

volvulus

pregnancy

Question 3

What imaging finding is highly correlated with the failure of conservative treatment of acute appendicitis?

free fluid

appendicolith

appendiceal wall thickening

circumscribed intra-abdominal retention

ileus

Question 4

According to current evidence, how many hours from the diagnosis of uncomplicated appendicitis can surgery be delayed, while antibiotics are given, in an adult patient with no risk factors, without increasing the risk of perforation?

1 to 4 hours

4 to 8 hours

8 to 12 hours

12 to 24 hours

24 to 48 hours

Question 5

When can an appendectomy be performed safely in a pregnant woman?

first trimester

second trimester

first and second trimesters

second and third trimesters

first, second, and third trimesters

Question 6

If acute appendicitis is suspected and free air is demonstrated, what is the appropriate management?

conservative, with antibiotics

conservative, with antibiotics and interventional drain placement

urgent surgery

surgery within 24 hours

elective surgery

Question 7

What percentage of appendectomies in children are still performed by open surgery?

circa 10%

circa 25%

circa 40%

circa 60%

circa 75%

Question 8

What is the imaging method of first choice?

MRI

CT

abdominal ultrasonography

abdominal plain films

contrast ultrasonography

Question 9

Girls of what age are at highest risk for appendectomy?

1–5 years

5–9 years

9–13 years

13–17 years

14–18 years

Question 10

What combination of antibiotics is now used most commonly in Germany and abroad in the conservative management of acute appendicitis?

quinolones and nitroimidazole

penicillin and a beta-lactamase inhibitor

cephalosporins and nitroimidazole

lincosamides and nitroimidazole

glycopeptides and nitroimidazole

?Participation is possible only via the Internet: cme.aerzteblatt.de

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Ethan Taub, M.D.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement The authors state that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Statistisches Bundesamt (ed.) Fallpauschalenbezogene Krankenhausstatistik (DRG-Statistik) Operationen und Prozeduren der vollstationären Patientinnen und Patienten in Krankenhäusern (4-Steller) 2018. Wiesbaden: Destatis. 2019 5231401187014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buckius MT, McGrath B, Monk J, Grim R, Bell T, Ahuja V. Changing epidemiology of acute appendicitis in the United States: study period 1993-2008. J Surg Res. 2012;175:185–190. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2011.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sahm M, Koch A, Schmidt U, et al. Akute Appendizitis - Klinische Versorgungsforschung zur aktuellen chirurgischen Therapie. Zentralbl Chir. 2013;138:270–277. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1283947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Addiss DG, Shaffer N, Fowler BS, Tauxe RV. The epidemiology of appendicitis and appendectomy in the United States. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;132:910–925. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rolle U, Maneck M. Versorgungstrends, regionale Variation und Qualität der Versorgung bei Appendektomien Versorgungsreport 2015/2016. In: Klauber J, Günster C, Gerste B, Robra B-P, Schmacke N, Abbas S, editors. Schattauer. Stuttgart: 2016. pp. 217–238. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sartelli M, Baiocchi GL, Di Saverio S, et al. Prospective observational study on acute appendicitis worldwide (POSAW) World J Emerg Surg. 2018;13 doi: 10.1186/s13017-018-0179-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Coppi P, Pozzobon M, Piccoli M, et al. Isolation of mesenchymal stem cells from human vermiform appendix. J Surg Res. 2006;135:85–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2006.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bollinger RR, Barbas AS, Bush EL, Lin SS, Parker W. Biofilms in the large bowel suggest an apparent function of the human vermiform appendix. J Theor Biol. 2007;249:826–831. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2007.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bollinger RR, Barbas AS, Bush EL, Lin SS, Parker W. Biofilms in the normal human large bowel: fact rather than fiction. Gut. 2007;56:1481–1482. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Korndorffer JR Jr, Fellinger E, Reed W. SAGES guideline for laparoscopic appendectomy. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:757–761. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0632-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Di Saverio S, Birindelli A, Kelly MD, et al. WSES Jerusalem guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of acute appendicitis. World J Emerg Surg. 2016;11 doi: 10.1186/s13017-016-0090-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gorter RR, Eker HH, Gorter-Stam MA, et al. Diagnosis and management of acute appendicitis EAES consensus development conference 2015. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:4668–4690. doi: 10.1007/s00464-016-5245-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zachariou Z. Appendizitis Kinderchirurgie: Viszerale und allgemeine Chirurgie des Kindesalters. In: von Schweinitz D, Ure B, editors. Springer. Berlin, Heidelberg: 2009. pp. 413–420. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stein GY, Rath-Wolfson L, Zeidman A, et al. Sex differences in the epidemiology, seasonal variation, and trends in the management of patients with acute appendicitis. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2012;397:1087–1092. doi: 10.1007/s00423-012-0958-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Almström M, Svensson JF, Svenningsson A, Hagel E, Wester T. Population-based cohort study on the epidemiology of acute appendicitis in children in Sweden in 1987-2013. BJS Open. 2018;2:142–150. doi: 10.1002/bjs5.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Humes D, Speake WJ, Simpson J. Appendicitis. BMJ Clin Evid. 2007;2007 0408. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kang K, Kim WJ, Kim K, et al. Effect of pain control in suspected acute appendicitis on the diagnostic accuracy of surgical residents. CJEM. 2015;17:54–61. doi: 10.2310/8000.2013.131285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kharbanda AB, Taylor GA, Fishman SJ, Bachur RG. A clinical decision rule to identify children at low risk for appendicitis. Pediatrics. 2005;116:709–716. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Humes DJ, Simpson J. Acute appendicitis. BMJ. 2006;333:530–534. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38940.664363.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shogilev DJ, Duus N, Odom SR, Shapiro NI. Diagnosing appendicitis: evidence-based review of the diagnostic approach in 2014. West J Emerg Med. 2014;15:859–871. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2014.9.21568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Andersson RE. Meta-analysis of the clinical and laboratory diagnosis of appendicitis. Br J Surg. 2004;91:28–37. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yu C-W, Juan L-I, Wu M-H, Shen C-J, Wu J-Y, Lee C-C. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the diagnostic accuracy of procalcitonin, C-reactive protein and white blood cell count for suspected acute appendicitis. Br J Surg. 2013;100:322–329. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li Y, Zhang Z, Cheang I, Li X. Procalcitonin as an excellent differential marker between uncomplicated and complicated acute appendicitis in adult patients. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2019 2020;46:853–858. doi: 10.1007/s00068-019-01116-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takada T, Nishiwaki H, Yamamoto Y, et al. The role of digital rectal examination for diagnosis of acute appendicitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0136996. e0136996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Soundappan SS, Karpelowsky J, Lam A, Lam L, Cass D. Diagnostic accuracy of surgeon performed ultrasound (SPU) for appendicitis in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2018;53:2023–2027. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2018.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Doria AS, Moineddin R, Kellenberger CJ, et al. US or CT for diagnosis of appendicitis in children and adults? A meta-analysis. Radiology. 2006;241:83–94. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2411050913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garcia EM, Camacho MA, et al. Expert Panel on Gastrointestinal Imaging, ACR Appropriateness Criteria® right lower quadrant pain-suspected appendicitis. J Am Coll Radiol. 2018;15:373–387. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2018.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.National Surgical Research Collaborative. Multicentre observational study of performance variation in provision and outcome of emergency appendicectomy. Br J Surg. 2013;100:1240–1252. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pickhardt PJ, Lawrence EM, Pooler BD, Bruce RJ. Diagnostic performance of multidetector computed tomography for suspected acute appendicitis. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154:789–796. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-12-201106210-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lim J, Pang Q, Alexander R. One year negative appendicectomy rates at a district general hospital: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Int J Surg. 2016;31:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brockman SF, Scott S, Guest GD, Stupart DA, Ryan S, Watters DA. Does an acute surgical model increase the rate of negative appendicectomy or perforated appendicitis? ANZ J Surg. 2013;83:744–747. doi: 10.1111/ans.12211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yun SJ, Ryu C-W, Choi NY, Kim HC, Oh JY, Yang DM. Comparison of low- and standard-dose CT for the diagnosis of acute appendicitis: a meta-analysis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2017;208:W198–W207. doi: 10.2214/AJR.16.17274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim K, Kim YH, Kim SY, et al. Low-dose abdominal CT for evaluating suspected appendicitis. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1596–1605. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ramalingam V, Bates DD, Buch K, et al. Diagnosing acute appendicitis using a nonoral contrast CT protocol in patients with a BMI of less than 25. Emerg Radiol. 2016;23:455–462. doi: 10.1007/s10140-016-1421-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anderson BA, Salem L, Flum DR. A systematic review of whether oral contrast is necessary for the computed tomography diagnosis of appendicitis in adults. Am J Surg. 2005;190:474–478. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2005.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Farrell CR, Bezinque AD, Tucker JM, Michiels EA, Betz BW. Acute appendicitis in childhood: oral contrast does not improve CT diagnosis. Emerg Radiol. 2018;25:257–263. doi: 10.1007/s10140-017-1574-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jung JY, Na JU, Han SK, Choi PC, Lee JH, Shin DH. Differential diagnoses of magnetic resonance imaging for suspected acute appendicitis in pregnant patients. World J Emerg Med. 2018;9:26–32. doi: 10.5847/wjem.j.1920-8642.2018.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Harrison PW. Appendicitis and the antibiotics. Am J Surg. 1953;85:160–163. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(53)90476-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Andersson RE. The natural history and traditional management of appendicitis revisited: spontaneous resolution and predominance of prehospital perforations imply that a correct diagnosis is more important than an early diagnosis. World J Surg. 2007;31:86–92. doi: 10.1007/s00268-006-0056-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vons C, Barry C, Maitre S, et al. Amoxicillin plus clavulanic acid versus appendicectomy for treatment of acute uncomplicated appendicitis: an open-label, non-inferiority, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;377:1573–1579. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60410-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E1.Podda M, Cillara N, Di Saverio S, et al. Antibiotics-first strategy for uncomplicated acute appendicitis in adults is associated with increased rates of peritonitis at surgery. A systematic review with meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing appendectomy and non-operative management with antibiotics. Surgeon. 2017;15:303–314. doi: 10.1016/j.surge.2017.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E2.Podda M, Gerardi C, Cillara N, et al. Antibiotic treatment and appendectomy for uncomplicated acute appendicitis in adults and children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2019;270:1028–1040. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E3.Maita S, Andersson B, Svensson JF, Wester T. Nonoperative treatment for nonperforated appendicitis in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatr Surg Int. 2020;36:261–269. doi: 10.1007/s00383-019-04610-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E4.Georgiou R, Eaton S, Stanton MP, Pierro A, Hall NJ. Efficacy and safety of nonoperative treatment for acute appendicitis: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2017;139 doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-3003. e20163003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E5.Kessler U, Mosbahi S, Walker B, et al. Conservative treatment versus surgery for uncomplicated appendicitis in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Dis Child. 2017;102:1118–1124. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2017-313127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E6.Patkova B, Svenningsson A, Almström M, Eaton S, Wester T, Svensson JF. Nonoperative treatment versus appendectomy for acute nonperforated appendicitis in children: five-year follow up of a randomized controlled pilot trial. Ann Surg. 2020;271:1030–1035. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E7.Salminen P, Paajanen H, Rautio T, et al. Antibiotic therapy vs appendectomy for treatment of uncomplicated acute appendicitis: the APPAC randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;313:2340–2348. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.6154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E8.Salminen P, Tuominen R, Paajanen H, et al. Five-year follow-up of antibiotic therapy for uncomplicated acute appendicitis in the APPAC randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;320:1259–1265. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.13201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E9.Prechal D, Damirov F, Grilli M, Ronellenfitsch U. Antibiotic therapy for acute uncomplicated appendicitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2019;34:963–971. doi: 10.1007/s00384-019-03296-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E10.Vanhatalo S, Munukka E, Sippola S, et al. Prospective multicentre cohort trial on acute appendicitis and microbiota, aetiology and effects of antimicrobial treatment: study protocol for the MAPPAC (Microbiology APPendicitis ACuta) trial. BMJ Open. 2019;9 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-031137. e031137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E11.Sippola S, Grönroos J, Sallinen V, et al. A randomised placebo-controlled double-blind multicentre trial comparing antibiotic therapy with placebo in the treatment of uncomplicated acute appendicitis: APPAC III trial study protocol. BMJ Open. 2018;8 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023623. e023623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E12.Gomes CA, Sartelli M, Di Saverio S, et al. Acute appendicitis: proposal of a new comprehensive grading system based on clinical, imaging and laparoscopic findings. World J Emerg Surg. 2015;10 doi: 10.1186/s13017-015-0053-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E13.Phillips AW, Jones AE, Sargen K. Should the macroscopically normal appendix be removed during laparoscopy for acute right iliac fossa pain when no other explanatory pathology is found? Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2009;19:392–394. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e3181b71957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E14.Chang AR. An analysis of the pathology of 3003 appendices. Aust N Z J Surg. 1981;51:169–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1981.tb05932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E15.Chandrasegaram MD, Rothwell LA, An EI, Miller RJ. Pathologies of the appendix: a 10-year review of 4670 appendicectomy specimens. ANZ J Surg. 2012;82:844–847. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2012.06185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E16.Simillis C, Symeonides P, Shorthouse AJ, Tekkis PP. A meta-analysis comparing conservative treatment versus acute appendectomy for complicated appendicitis (abscess or phlegmon) Surgery. 2010;147:818–829. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2009.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E17.Shekarriz S, Keck T, Kujath P, et al. Comparison of conservative versus surgical therapy for acute appendicitis with abscess in five German hospitals. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2019;34:649–655. doi: 10.1007/s00384-019-03238-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E18.Gavriilidis P, de’Angelis N, Katsanos K, Di Saverio S. Acute appendicectomy or conservative treatment for complicated appendicitis (phlegmon or abscess)? A systematic review by updated traditional and cumulative meta-analysis. J Clin Med Res. 2019;11:56–64. doi: 10.14740/jocmr3672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E19.Dong Y, Tan S, Fang Y, Yu W, Li N. Meta-analysis of laparoscopic surgery versus conservative treatment for appendiceal abscess. Zhonghua Wei Chang Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2018;21:1433–1438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E20.Al-Kurd A, Mizrahi I, Siam B, et al. Outcomes of interval appendectomy in comparison with appendectomy for acute appendicitis. J Surg Res. 2018;225:90–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2018.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E21.Becker P, Fichtner-Feigl S, Schilling D. Clinical management of appendicitis. Visc Med. 2018;34:453–458. doi: 10.1159/000494883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E22.Mentula P, Sammalkorpi H, Leppäniemi A. Laparoscopic surgery or conservative treatment for appendiceal abscess in adults? A randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg. 2015;262:237–242. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E23.Busch M, Gutzwiller FS, Aellig S, Kuettel R, Metzger U, Zingg U. In-hospital delay increases the risk of perforation in adults with appendicitis. World J Surg. 2011;35:1626–1633. doi: 10.1007/s00268-011-1101-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E24.Beecher S, O’Leary DP, McLaughlin R. Hospital tests and patient related factors influencing time-to-theatre in 1000 cases of suspected appendicitis: a cohort study. World J Emerg Surg. 2015;10 doi: 10.1186/1749-7922-10-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E25.Aiken T, Barrett J, Stahl CC, et al. Operative delay in adults with appendicitis: Time is money. J Surg Res. 2020;253:232–237. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2020.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E26.Meltzer JA, Kunkov S, Chao JH, et al. Association of delay in appendectomy with perforation in children with appendicitis. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2019;35:45–49. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000000850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E27.Li J, Xu R, Hu D-M, Zhang Y, Gong T-P, Wu X-L. Effect of delay to operation on outcomes in patients with acute appendicitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2019;23:210–223. doi: 10.1007/s11605-018-3866-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E28.van Dijk ST, van Dijk AH, Dijkgraaf MG, Boermeester MA. Meta-analysis of in-hospital delay before surgery as a risk factor for complications in patients with acute appendicitis. Br J Surg. 2018;105:933–945. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E29.Cameron DB, Williams R, Geng Y, et al. Time to appendectomy for acute appendicitis: A systematic review. J Pediatr Surg. 2018;53:396–405. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2017.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E30.Serres SK, Cameron DB, Glass CC, et al. Time to appendectomy and risk of complicated appendicitis and adverse outcomes in children. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171:740–746. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.0885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E31.Bhangu A United Kingdom National Surgical Research Collaborative. Safety of short, in-hospital delays before surgery for acute appendicitis: multicentre cohort study, systematic review, and meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2014;259:894–903. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E32.Fugazzola P, Coccolini F, Tomasoni M, Stella M, Ansaloni L. Early appendectomy vs conservative management in complicated acute appendicitis in children: A meta-analysis. J Pediatr Surg. 2019;54:2234–2241. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2019.01.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E33.Hecker A, Schneck E, Röhrig R, et al. The impact of early surgical intervention in free intestinal perforation: a time-to-intervention pilot study. World J Emerg Surg. 2015;10 54 doi: 10.1186/s13017-015-0047-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E34.Andersen BR, Kallehave FL, Andersen HK. Antibiotics versus placebo for prevention of postoperative infection after appendicectomy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001439.pub2. CD001439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E35.Daskalakis K, Juhlin C, Påhlman L. The use of pre- or postoperative antibiotics in surgery for appendicitis: a systematic review. Scand J Surg. 2014;103:14–20. doi: 10.1177/1457496913497433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E36.Baum P, Diers J, Lichthardt S, et al. Mortality and complications following visceral surgery—a nationwide analysis based on the diagnostic categories used in German hospital invoicing data. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2019;116:739–746. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2019.0739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E37.Enblad M, Birgisson H, Ekbom A, Sandin F, Graf W. Increased incidence of bowel cancer after non-surgical treatment of appendicitis. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2017;43:2067–2075. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2017.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E38.Andersson R, Lambe M, Bergström R. Fertility patterns after appendicectomy: historical cohort study. BMJ. 1999;318:963–967. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7189.963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E39.Gutiérrez MC, Cefrorela N, Palenzuela SA. Carcinoid tumors of the appendix. Pediatr Pathol Lab Med. 1995;15:641–642. doi: 10.3109/15513819509026999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E40.Pape U-F, Perren A, Niederle B, et al. ENETS Consensus Guidelines for the management of patients with neuroendocrine neoplasms from the jejuno-ileum and the appendix including goblet cell carcinomas. Neuroendocrinology. 2012;95:135–156. doi: 10.1159/000335629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E41.Huang L, Yin Y, Yang L, Wang C, Li Y, Zhou Z. Comparison of antibiotic therapy and appendectomy for acute uncomplicated appendicitis in children: a meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171:426–434. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.0057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E42.Clarke T, Katkhouda N, Mason RJ, et al. Laparoscopic versus open appendectomy for the obese patient: a subset analysis from a prospective, randomized, double-blind study. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:1276–1280. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-1359-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E43.Yeh C-C, Wu S-C, Liao C-C, Su L-T, Hsieh C-H, Li T-C. Laparoscopic appendectomy for acute appendicitis is more favorable for patients with comorbidities, the elderly, and those with complicated appendicitis: a nationwide population-based study. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:2932–2942. doi: 10.1007/s00464-011-1645-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E44.Masoomi H, Mills S, Dolich MO, et al. Does laparoscopic appendectomy impart an advantage over open appendectomy in elderly patients? World J Surg. 2012;36:1534–1539. doi: 10.1007/s00268-012-1545-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E45.Southgate E, Vousden N, Karthikesalingam A, Markar SR, Black S, Zaidi A. Laparoscopic vs open appendectomy in older patients. Arch Surg. 2012;147:557–562. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2012.568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E46.Wang D, Dong T, Shao Y, Gu T, Xu Y, Jiang Y. Laparoscopy versus open appendectomy for elderly patients, a meta-analysis and systematic review BMC Surg. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6540400/ (last accessed on 26 May 2020) 2019;19 doi: 10.1186/s12893-019-0515-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E47.Kim MJ, Fleming FJ, Gunzler DD, Messing S, Salloum RM, Monson JRT. Laparoscopic appendectomy is safe and efficacious for the elderly: an analysis using the National Surgical Quality Improvement Project Database. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:1802–1807. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-1467-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E48.Kitaoka K, Saito K, Tokuuye K. Significance of CD4+ T-cell count in the management of appendicitis in patients with HIV. Can J Surg. 2015;58:429–430. doi: 10.1503/cjs.015714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E49.Bakker OJ, Go PM, Puylaert JB, Kazemier G, Heij HA. Werkgroup en klankbordgroup „Richtlijn acute appendicitis“: Guideline on diagnosis and treatment of acute appendicitis: imaging prior to appendectomy is recommended. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2010;154 A303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E50.Gorter RR, Heij HA, Eker HH, Kazemier G. Laparoscopic appendectomy: State of the art Tailored approach to the application of laparoscopic appendectomy? Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;28:211–224. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2013.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E51.Walker HGM, Al Samaraee A, Mills SJ, Kalbassi MR. Laparoscopic appendicectomy in pregnancy: a systematic review of the published evidence. Int J Surg. 2014;12:1235–1241. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.08.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E52.Dowgiałło-Wnukiewicz N, Kozera P, Wójcik W, Lech P, Rymkiewicz P, Michalik M. Surgical treatment of acute appendicitis in older patients. Pol Przegl Chir. 2019;91:12–15. doi: 10.5604/01.3001.0012.8556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E53.Wilasrusmee C, Sukrat B, McEvoy M, Attia J, Thakkinstian A. Systematic review and meta-analysis of safety of laparoscopic versus open appendicectomy for suspected appendicitis in pregnancy. Br J Surg. 2012;99:1470–1478. doi: 10.1002/bjs.8889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E54.Fallon WF, Newman JS, Fallon GL, Malangoni MA. The surgical management of intra-abdominal inflammatory conditions during pregnancy. Surg Clin North Am. 1995;75:15–31. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(16)46530-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E55.Palanivelu C, Rangarajan M, Senthilkumaran S, Parthasarathi R. Safety and efficacy of laparoscopic surgery in pregnancy: experience of a single institution. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2007;17:186–190. doi: 10.1089/lap.2006.0037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E56.Lee SH, Lee JY, Choi YY, Lee JG. Laparoscopic appendectomy versus open appendectomy for suspected appendicitis during pregnancy: a systematic review and updated meta-analysis. BMC Surg. 2019;19 doi: 10.1186/s12893-019-0505-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E57.Stundner-Ladenhauf H, Metzger R. Appendizitis im Kindesalter. Monatsschr Kinderheilkd. 2019;167:547–560. [Google Scholar]

- E58.Alvarado A. A practical score for the early diagnosis of acute appendicitis. Ann Emerg Med. 1986;15:557–564. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(86)80993-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E59.Andersson M, Andersson RE. The appendicitis inflammatory response score: a tool for the diagnosis of acute appendicitis that outperforms the Alvarado score. World J Surg. 2008;32:1843–1849. doi: 10.1007/s00268-008-9649-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eCase illustration

A 22-year-old man presented to the emergency department complaining of feeling unwell since the morning, with a migrating pain in the right lower abdominal quadrant. The further history was negative with respect to past medical illnesses, past operations, medications taken, and allergies. Laboratory tests revealed a leukocytosis of 22 000/L, a core body temperature of 37.6°C, and an unremarkable urine test strip. Physical examination revealed incipient peritoneal signs in the right lower quadrant, without guarding but with positive appendicitis pressure points and contralateral rebound pain. Ultrasonography revealed a small amount of periappendicular echo-free fluid without any circumscribed mass. The appendix was 9 mm in diameter, and an appendicolith was seen ultrasonographically. In view of the free fluid and the overall clinical picture, the patient was deemed to have a complicated case of appendicitis. After extensive discussion with the patient, and because of the likelihood that conservative treatment would fail, a decision was taken to perform a laparoscopic appendectomy. Perioperatively, the patient was given antibiotic treatment based on a cephalosporin and a nitroimidazole, and surgery ensued within 12 hours of the diagnosis. The intraoperative findings confirmed acute appendicitis. A laparoscopic appendectomy with clip application was performed. eFigure 2 shows the intraoperative view before and after exposure of the base of the appendix. eFigure 2 shows the twofold clip application at the base of the appendix, as well as the freely dissected appendicular artery before and after the artery was clipped and its distal portion removed together with the appendix itself. No further antibiotics were given postoperatively. The patient was discharged home on the second postoperative day after an uneventful course, feeling well and with an unremarkable abdominal examination.