Abstract

Abstract

The objective of this survey was to estimate the prevalence, contamination level, and genetic diversity of Salmonella in selected raw, shelled tree nuts (Brazil nuts, cashews, hazelnuts, macadamia nuts, pecans, pine nuts, pistachios, and walnuts) at retail markets in the United States. A total of 3,374 samples of eight tree nuts were collected from different types of retail stores and markets nationwide between September 2015 and March 2017. These samples (375 g) were analyzed using a modified FDA's BAM Salmonella culture method. Of the 3,374 samples, 15 (0.44%) (95% confidence interval [CI] [0.25, 0.73]) were culturally confirmed as containing Salmonella; 17 isolates were obtained. Among these isolates, there were 11 serotypes. Salmonella was not detected in Brazil nuts (296), hazelnuts (487), pecans (510), pine nuts (500), and walnuts (498). Salmonella prevalence estimates in cashews (510), macadamia (278), and pistachios (295) were 0.20% (95% CI [<0.01, 1.09]), 2.52% (95% CI [1.02, 5.12]), and 2.37% (95% CI [0.96, 4.83]), respectively. The rates of Salmonella isolation from major/big‐chain supermarkets (1381), small‐chain supermarkets (328), discount/variety/drug stores (1329), and online (336) were 0.29% (95% CI [0.08, 0.74]), 0.30% (95% CI [0.01, 1.69]), 0.45% (95% CI [0.17, 0.98]), and 1.19% (95% CI [0.33, 3.02]), respectively. Salmonella prevalence in organic (530) and conventional (2,844) nuts was not different statistically (P = 0.0601). Of the enumerated samples (15), 80% had Salmonella levels ≤0.0092 most probable number (MPN)/g. The highest contamination level observed was 0.75 MPN/g. The prevalence and contamination levels of Salmonella in the tree nuts analyzed were generally comparable to previous reports. Pulsed‐field gel electrophoresis, serotype, and sequencing data all demonstrated that Salmonella population in nuts is very diverse genetically.

Practical Application

The prevalence, contamination level, and genetic diversity of Salmonella in eight types of tree nuts (3,374 samples collected nationwide) revealed in this survey could help the development of mitigation strategies to reduce public health risks associated with consumption of these nuts.

Keywords: diversity, low moisture, low water activity, nuts, Salmonella, serotype, WGS

1. INTRODUCTION

Low‐water‐activity foods, such as tree nuts and peanuts, do not have the favorable characteristics for bacterial growth. However, Salmonella has been detected in almonds, cashews, hazelnuts, macadamia nuts, peanuts, pecans, pine nuts, pistachios, and walnuts in the past worldwide (Bansal, Jones, Abd, Danyluk, & Harris, 2010; Bedard, Kennedy, & Weimer, 2014; Blessington, Theofel, Mitcham, & Harris, 2013; Brar, Strawn, & Danyluk, 2016; Calhoun, Post, Warren, Thompson, & Bontempo, 2013; Danyluk et al., 2007; Davidson, Frelka, Yang, Jones, & Harris, 2015; Little, Jemmott, Surman‐Lee, Hucklesby, & De Pinna, 2009; Miksch et al., 2013; Zhang, Hu, Melka, et al., 2017). Salmonella has been shown to survive for a long period of time on tree nuts at ambient temperature (Abd, McCarthy, & Harris, 2012; Frelka, Davidson, & Harris, 2016; Kimber, Kaur, Wang, Danyluk, & Harris, 2012; Santillana Farakos, Pouillot, & Keller, 2017). In addition to Salmonella, Escherichia coli O157:H7 has been found in hazelnuts, peanuts, and walnuts (Canadian Food Inspection Agency, 2011; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011a; Miksch et al., 2013; Yada, 2019), and was reported to survive on in‐shell hazelnuts, almonds, pistachios, and walnuts (Blessington et al., 2013; Feng, Muyyarikkandy, Brown, & Amalaradjou, 2018; Kimber et al., 2012). Listeria monocytogenes has been found in cashews, almonds, walnuts, macadamia nuts, pine nuts, and mixed nuts (Eglezos, 2010; Ly, Parreira, & Farber, 2019; Yada, 2019). Bacteria with potential health risks especially for the young, old, and immunocompromised people, such as Pseudomonas, Clostridium spp., and Klebsiella spp., have also occasionally been found in nuts (Al‐Moghazy, Boveri, & Pulvirenti, 2014; Atungulu & Pan, 2012). Approximately 40 species of Aspergillus have been implicated in human or animal infections that can infect and cause decay in nuts. Some Aspergillus species produce aflatoxin, which is both a toxin and a carcinogen (Atungulu & Pan, 2012). The presence of such biological contaminants on tree nuts has the potential to lead to foodborne illness.

There were at least 25 recalls in 2015 in the United States alone due to Salmonella contamination of walnuts, pecans, macadamia nuts, pine nuts, almonds, and hazelnuts (Yada, 2019). Worldwide, there have been outbreaks of foodborne illness associated with almonds, cashews, hazelnuts, pine nuts, pistachios, and walnuts, with a majority of them caused by Salmonella. For example, in 2000, an outbreak of Salmonella Enteritidis resulted in 157 cases of human illness in Canada and 11 cases in the United States. The outbreak strain was isolated from almond samples collected from home, retail, distribution, and warehouse sources and from environmental swabs of processing equipment and associated farmers’ orchards (Foodborne Illness Outbreak Database, 2000). In 2011, Turkish pine nuts from bulk bins contaminated with Salmonella Enteritidis caused 43 human illnesses in 5 states (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011b). During 2013–2014, raw cashew cheese contaminated with Salmonella Stanley caused 17 illnesses and 3 hospitalizations in 3 states (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014b). In 2014, 6 people in 5 states were infected with Salmonella Braenderup. Collaborative investigation indicated that almond and peanut butter was the likely source of this outbreak (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014a). In 2016, there was an outbreak of Salmonella Montevideo and Salmonella Senftenberg linked to pistachios involving 9 U.S. states, sickening 11 people (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2016b). These events are examples of the potential public health risk associated with consumption of tree nuts contaminated with Salmonella. Information on the extent of Salmonella contamination, level of contamination, genetic diversity of Salmonella in tree nuts, and type of tree nuts contaminated could provide valuable information to help the development of mitigation strategies to reduce public health risks associated with consumption of nuts.

Pulsed‐field gel electrophoresis (PFGE), multiple‐locus variable‐number tandem‐repeat analysis (MLVA), and DNA microarray‐based comparative genomic indexing (CGI) were used to evaluate the genetic relatedness of Salmonella Enteritidis isolates from three outbreaks associated with raw almonds. All three methods differentiated these Salmonella Enteritidis strains in a manner that correlated with phage type (PT). PFGE and plasmid profiling were capable of differentiating isolates of Salmonella Enteritidis PT1 and PT4. However, different PTs showed the same PFGE pattern; and different PFGE types were determined to be the same PT (Lukinmaa, Schildt, Rinttilä, & Siitonen, 1999). Besides, PFGE, MLVA, and CGI failed to discriminate between Salmonella Enteritidis PT30 strains related to outbreaks from unrelated clinical strains or between strains separated by up to 5 years (Parker, Huynh, Quiñones, Harris, & Mandrell, 2010). In a survey to determine the prevalence of Salmonella enterica in the environment of a major produce region in California, PFGE analysis indicated that some of the Salmonella isolates are indistinguishable and/or highly related (Gorski et al., 2011). High‐resolution subtyping may provide more insight into the genetic makeup of the bacterial population. Whole genome sequencing (WGS) technology is advancing in an unprecedented pace in the last decade. It might be the ultimate tool to differentiate genetically closely related bacterial isolates. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and other public health agencies in the world are routinely using WGS in recent years allowing for significantly greater detailed analysis of isolates and outbreak investigations (Allard et al., 2016; Davis et al., 2015).

The objectives of this study were (1) to estimate the prevalence and contamination level of Salmonella in eight types of raw, shelled tree nuts in the U.S. retail markets, including products derived from conventional and organic production systems; (2) to investigate the diversity of the isolates obtained from these samples by means of PFGE, serotyping, and WGS; and (3) to characterize virulence genes and pathogenicity islands of the isolates using WGS data. The results will provide information about temporal variability in Salmonella prevalence, level of contamination, serotype, and genetic diversity in raw, shelled tree nuts and will assist the U.S. FDA in the development of a quantitative assessment of the risk of human salmonellosis associated with the consumption of tree nuts in the United States (U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2013). This work was performed in the context of an ongoing national survey conducted by U.S. FDA on the prevalence of foodborne pathogens in produce, spices, and nuts (Zhang et al., 2018; Zhang, Hu, Melka, et al., 2017; Zhang, Hu, Pouillot, et al., 2017).

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Tree nuts

From September 30, 2015 to March 29, 2017, a total of 3,374 raw, shelled tree nut samples, including Brazil nuts, cashews, pecans, hazelnuts, macadamia nuts, pistachios, pine nuts, and walnuts, were collected and analyzed (Table 1). Samples were consisted of whole nuts, halves, pieces, and diced or chopped nuts. Tree nuts that had been roasted or coated with candy or chocolate seasonings, nut butters, nut pastes, nut meals, nut flours, or mixed nuts were not included in the sampling.

Table 1.

Salmonella prevalence in raw, shelled tree nut samples from the U.S. retail market, based on 375‐g sample size

| No. of samples tested a | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nut type(Raw, Shelled) | Conventional | Organic | Total | No. of samples positive for Salmonella b | Salmonella prevalence (%) [95% CI] |

| Brazil | 239 | 57 | 296 | 0 | 0 [0, 1.24] |

| Cashews | 343 | 167 | 510 | 1 | 0.20 [<0.01, 1.09] |

| Hazelnuts | 426 | 61 | 487 | 0 | 0 [0, 0.75] |

| Macadamia | 221 | 57 | 278 | 7 | 2.52 [1.02, 5.12] |

| Pecans | 481 | 29 | 510 | 0 | 0 [0, 0.72] |

| Pine Nuts | 438 | 62 | 500 | 0 | 0 [0, 0.74] |

| Pistachios | 241 | 54 | 295 | 7 | 2.37 [0.96, 4.83] |

| Walnuts | 455 | 43 | 498 | 0 | 0 [0, 0.74] |

| Total | 2,844 | 530 | 3,374 | 15 | 0.44 [0.25, 0.73] |

Organic nuts accounted for 15.71% (530/3,374) of the total number of samples analyzed.

Four isolates were from organic macadamia nuts; one isolate was from organic pistachios. Salmonella prevalence was 0.94% (5/530) in organic nuts and 0.35% (10/2,844) in conventional nuts. Chi‐square test: P = 0.0601.

Abbreviation: CI, Clopper–Pearson's 95% confidence interval.

To be as representative as possible, the collection sites were selected using the U.S. Census Bureau map (https://www.census.gov/geo/maps-data/maps/reference.html): California, West Region, Pacific Division; Colorado, West Region, Mountain Division; Georgia, South Region, South Atlantic Division; Maryland, South Region, South Atlantic Division; Minnesota, Midwest Region, West North Central Division; Texas, South Region, West South Central Division; Washington, West Region, Pacific Division; Illinois, Midwest Region, East North Central Division; North Carolina, South Region, South Atlantic Division; and Vermont, Northeast region, New England Division.

Tree nut samples were collected from different types of retail venues categorized as (1) major chain/big‐chain supermarkets, including national and regional supermarkets; (2) small‐chain/independent organic and specialty supermarkets, including retail outlets; and (3) discount/variety/drug stores: discount stores, including large discount clubs such as BJ's, Costco, and Sam's Club, and smaller discount stores such as Dollar stores; other significant points of sale for which foods are just a fraction of their business, including national and regional drug stores, gas stations, and so on; (4) online retailers. The number of samples collected from each market category and the number of unique addresses visited when collecting samples are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Salmonella prevalence in raw, shelled tree nut samples according to retail source and serotypes of isolates recovered from positive samples, based on 375‐g sample size

| Retailer type | No. (%) of samples | No. of points of sale | No. of samples positive for Salmonella | Salmonella prevalence (%)[95% CI] | Salmonella serotype a (No. of isolates) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Major or big chain supermarkets | 1,381 (40.93) | 168 | 4 | 0.29 [0.08, 0.74] | Muenchen (1), Liverpool (1), Senftenberg (2) |

| Small chain supermarkets | 328 (9.72) | 57 | 1 | 0.30 [0.01, 1.69] | diarizonae O61(1) |

| Discount, variety, or drug stores | 1329 (39.39) | 148 | 6 | 0.45 [0.17, 0.98] | Mbandaka (1), Urbana (1), diarizonae N.N. (1), Give (3) |

| Online | 336 (9.96) | 120 | 4 | 1.19 [0.33, 3.02] | Senftenberg (1), Worthington (1), Montevideo (2), Mbandaka (1), Duisburg (1) |

| Total | 3,374 | 493 | 15 | 0.44 [0.25, 0.73] |

Abbreviation: CI, Clopper–Pearson's 95% confidence interval.

aTwo pistachios samples obtained from online retailers had two different serotypes each.

In most cases, the minimum sample size was 800 g. For a few samples of pine nuts, where it was difficult to obtain the required amount from a single lot, 500 g per sample was purchased. The lesser amount was sufficient to ensure that 375 g would be analyzed for Salmonella. When a sample was positive and enumeration by MPN was needed, this lesser amount would not be enough for the 3 × 100 g subsequent dilution series. However, all pine nut samples were negative for Salmonella and thus the smaller sample size did not affect the survey results.

Only prepackaged (e.g., bags, cans, or jars) tree nuts labeled raw were collected. Samples were not repackaged at the time of purchasing to avoid cross‐contamination. Collected samples remained sealed before microbiological analysis. Nuts in open bins, where consumers self‐serve, were not sampled, nor were nuts from displays in the shops. Whenever multiple retail sale units were required to attain a sufficient sample size, all units were from the same lot and were placed in one plastic zip‐style bag. All samples were assigned a unique identifier that identified the producer, or distributor, as well as a “use by” or “sell by” date and/or lot number. Collected nuts were held at 4 °C before microbiological analysis and analyzed in 2 weeks.

2.2. Microbiological analyses

The sample size used for analyzing the presence/absence of Salmonella in tree nuts was 375 g. Nut to pre‐enrichment broth ratio was 1:9 (w/v). Detection, isolation, and confirmation of Salmonella from nuts were performed with a modified method described in the FDA Bacteriological Analytical Method (BAM) Chapter 5, Salmonella (U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2018). Lactose broth used in the BAM Salmonella method was replaced with buffered peptone water.

Enumeration of Salmonella in samples that tested positive was conducted by a three‐tube, five‐dilution (100, 10, 1.0, 0.1, and 0.01 g) most probable number (MPN) method and FDA BAM Chapter 5, Salmonella (U. S. Food and Drug Administration, 2017; U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2018). Lactose broth was replaced with buffered peptone water as above.

2.3. Salmonella serotyping

Serotyping of Salmonella isolates was conducted using the Luminex xMAP® Salmonella serotyping assay (Luminex, Austin, TX). Untypeable isolates by Luminex xMAP® Salmonella serotyping assay were serotyped using the conventional Kauffman–White antigenic formulae scheme (Grimont & Weill, 2007; U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2018).

2.4. PFGE analysis

PFGE laboratory analysis of the Salmonella isolates followed official Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) PulseNet protocols. XbaI was utilized as the primary restriction enzyme and BlnI as the secondary restriction enzyme (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2016c). PFGE patterns were analyzed with the BioNumerics v.7.6 software (Applied Maths, Austin, TX).

2.5. WGS and analysis

Salmonella isolates were grown in tryptic soy broth (TSB, Difco, Franklin Lakes, NJ) overnight at 37 °C. Genomic DNA was extracted using the DNeasy Blood & Tissue kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). DNA concentrations were measured with a Qubit fluorometer (Life Technologies, Invitrogen, CA, USA), standardized to 0.2 ng/µL, and stored at −20 °C prior to library preparation. Libraries were prepared with the Nextera XT DNA sample preparation kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. All genomes were sequenced using the Illumina MiSeq sequencing technology with 500 (2 × 250) cycles (Illumina), pair‐end library with coverage depth of 30 to 90× at the Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition (CFSAN), FDA. Assembled sequenced reads were submitted to the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) of National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) (Allard et al., 2016).

A k‐mer‐based approach, kSNP3.0, was used to generate the pan single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) matrix for the 17 draft genomes, with the optimum k‐mer size of 19, which was determined by Kchooser provided in kSNP 3.0 (Gardner, Slezak, & Hall, 2015). The phylogenetic tree was then inferred on the pan SNP matrix using FastTree 2.1.7 with generalized time‐reversible models of nucleotide evolution, two rate categories of sites, and Gamma likelihoods (Price, Dehal, & Arkin, 2010). We also checked the results by CFSAN SNP pipeline, using the complete genome of Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhimurium str. LT2 (NC_003197.2) as the reference (Davis et al., 2015). Thirteen pathogenicity islands in Salmonella (SPIs; including SPI‐1 to SPI‐10, HPI, SGI‐1, and CS54 island) and 45 selected virulence genes were used to characterize and profile the Salmonella isolates from the eight types of tree nuts studied (Borges et al., 2017; Levin, 2009; Schmidt & Hensel, 2004). The presence and absence of the genes and SPIs were analyzed by blasting WGS data of the isolates against the NCBI database (Camacho et al., 2009).

2.6. Statistical analysis

Confidence intervals (CIs) for prevalence rates were derived using the Clopper and Pearson's procedure; prevalence rates were compared using Fisher's exact test; and the Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel chi‐square test was used to test the conditional independence of a factor (conventional vs. organically grown, types of retail) for each tree nut commodity. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism v7.0 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA).

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1. Salmonella prevalence in tree nuts

The prevalence of Salmonella in raw, shelled nut samples collected at retail in the United States is shown in Table 1. It is important to point out that our analytical sample size is 375 g, instead of the regular 25 g. Theoretically, our method is 15 times more sensitive than the regular 25 g method. Overall, Salmonella was isolated from 15 of 3,374 samples analyzed over the course of the survey. Salmonella was not detected in Brazil nuts (n = 296), hazelnuts (n = 487), pecans (n = 510), pine nuts (n = 500), and walnuts (n = 498). Salmonella prevalence estimates for cashews (n = 510), macadamia nuts (n = 278), and pistachios (n = 295) were 0.20% ([95% CI [<0.01, 1.09]), 2.52% ([95% CI [1.02, 5.12]), and 2.37% ([95% CI [0.96, 4.83]), respectively. Macadamia nuts had the highest Salmonella prevalence nominally among all eight types of nuts. The overall prevalence of Salmonella among all 3,374 samples collected (eight types of tree nuts) was 0.44% (95% CI [0.25, 0.73]). Salmonella was not detected in pecans (n = 623) or in‐shell hazelnuts (n = 80) during a previous nationwide survey (sample size = 375 g) we carried out between October 2014 and October 2015 (Zhang, Hu, Melka, et al., 2017). Moreover, prevalence in raw, shelled cashews (n = 733), hazelnuts (n = 577), pine nuts (n = 630), walnuts (n = 658), and macadamia nuts (n = 355) were 0.55%, 0.35%, 0.48%, 1.22%, and 4.20%, respectively, and overall prevalence in 3,656 samples analyzed was 0.88% (Zhang, Hu, Melka, et al., 2017). In both surveys (n = 7,030), the highest number of positive Salmonella samples was observed in macadamia nuts. Moreover, Salmonella was not detected on pecans in either survey. However, the present results differ from the results in the 2014 to 2015 survey where Salmonella prevalence rates in walnuts, hazelnuts (shelled), and pine nuts were 1.22, 0.35, and 0.48%, respectively (Zhang, Hu, Melka, et al., 2017). A recently published risk assessment of Salmonella on walnuts by the FDA suggested that the higher prevalence of Salmonella observed in the 2014 to 2015 retail survey is a reflection of variability in Salmonella contamination across the supply or an atypical event affecting a portion of the supply (Santillana Farakos et al., 2018). This might also indicate that the industry is working effectively to reduce pathogens in their products under the influence of Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA). The FDA prevalence data were similar to limited published reports (Brar et al., 2016; Danyluk et al., 2007; Davidson et al., 2015; Eglezos, Huang, & Stuttard, 2008; Harris et al., 2016; Little et al., 2009) on Salmonella contamination of different varieties of tree nuts as summarized in our recent publication (Zhang, Hu, Melka, et al., 2017). When comparing the prevalence of Salmonella among different surveys, readers need to take consideration of differences in collection points, sample sizes, and detection methodologies used in different studies. Information on the production, harvest methods, and processing steps for tree nuts as well as the prevalence and levels of Salmonella in tree nuts at harvest, upstream from retail samples may support the development of mitigation strategies to control Salmonella.

Only 530 organic raw, shelled nut samples (15.71% of the total) were analyzed due to the limited availability of such products in the U.S. retail market. Four of the five Salmonella positive organic samples were macadamia nuts and one was pistachio. Salmonella prevalence rate for organic and conventional nuts overall was 0.94 and 0.35%, respectively, although the difference was not statistically significant (Chi‐square test: P = 0.0601) (Table 1). Organic nuts had high Salmonella prevalence rate in this survey mainly due to the higher numbers of positive macadamia nuts samples. In our previous survey (Zhang, Hu, Melka, et al., 2017), macadamia nuts also had higher rate of Salmonella contamination than other nuts surveyed; there was no significant difference for prevalence of Salmonella between organic and conventional tree nuts, which were 0.61% (326) and 0.90% (3330), respectively.

Samples were obtained from 493 sources including 1,381 major/big‐chain supermarkets, 328 small‐chain supermarkets, 1,329 discount/variety/drug stores, and 336 online retailers. Corresponding Salmonella prevalence rates of 0.29, 0.30, 0.45, and 1.19%, respectively, were not statistically different (Chi‐square test: P = 0.1633) (Table 2).

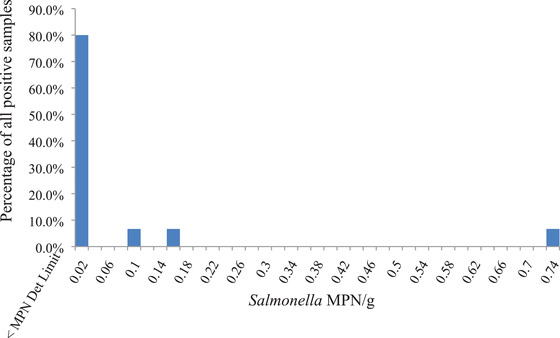

3.2. Estimates of Salmonella populations in contaminated tree nuts

Salmonella populations in the 15 contaminated samples were estimated by a three‐tube, five‐dilution (100, 10, 1.0, 0.1, and 0.01 g) MPN method. The total sample size for MPN analysis was 333.33 g of nuts for each sample. Salmonella populations ranged from <0.003 to 0.75 MPN/g among these nut samples. The highest estimate was 0.75 MPN/g and 80% of the samples contained ≤0.0092 MPN/g (Figure 1). Similar Salmonella population estimates in positive tree nut samples were observed in the previous similarly structured survey, where 60.7% of Salmonella‐positive tree nuts samples had Salmonella below the limit of detection of 0.003 MPN/g, 25% had 0.003 to 0.005 MPN/g, and the highest was 0.092 MPN/g (Zhang, Hu, Melka, et al., 2017). Similar results have been reported for surveys of nut commodities including almonds, peanuts, pecans, walnuts, and pistachios (Brar et al., 2016; Calhoun et al., 2013; Danyluk et al., 2007; Davidson et al., 2015; Harris et al., 2016). An estimate of 8.5 MPN/100 g has been reported for recalled raw almonds associated with a Salmonella outbreak (Danyluk et al., 2007). In another investigation, raw almonds that arrived at processors were positive for Salmonella at a prevalence rate of 0.87% with contamination levels at 1.2 to 2.9 MPN/100 g (Danyluk et al., 2007). In a survey on prevalence of Salmonella on in‐shell California walnuts, an average prevalence rate of 0.14% was determined and contamination levels for positive samples were estimated to be 0.32 to 0.42 MPN/100 g (Davidson et al., 2015). In another study on raw California in‐shell pistachios, prevalence rates of Salmonella for floaters (nuts that float in a float tank containing water during processing) and sinkers (nuts that sink) were 2.0% and 0.37%, respectively, with a weighted average of 0.61% (Harris et al., 2016). In‐shell pecans were tested for Salmonella and a prevalence rate of 0.95% was reported with Salmonella levels at 0.47 to 39 MPN/100 g, averaging at 2.4 MPN/100 g (Brar et al., 2016). In another survey on Salmonella contamination of raw, shelled peanuts, 2.33% of the samples were determined to be positive for Salmonella with concentration levels ranging from <0.03 to 2.4 MPN/g (Calhoun et al., 2013).

Figure 1.

Estimates of Salmonella populations of contaminated raw, shelled tree nut samples, by a three‐tube, five‐dilution (100, 10, 1.0, 0.1, and 0.01 g) most probable number (MPN) assay.

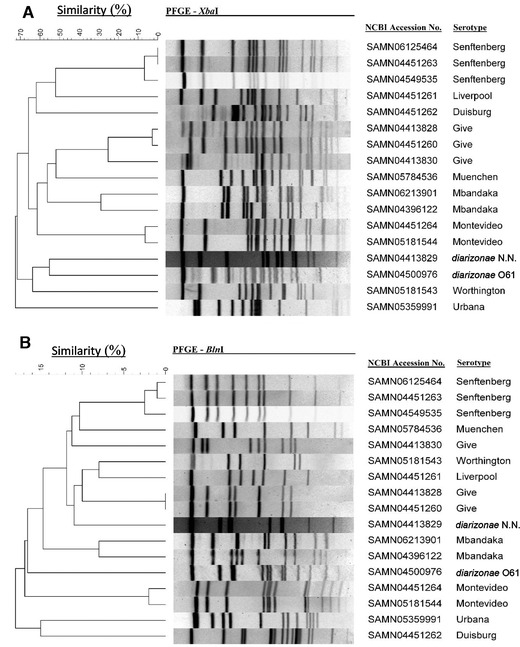

3.3. Diversity of serotypes and PFGE profiles of Salmonella isolated from tree nuts

We obtained 17 Salmonella isolates out of the 15 Salmonella‐positive tree nut samples with two pistachio samples containing two different isolates each (Table 3). Among the 17 isolates, there were 11 different serotypes. Except for one isolate from cashews (Salmonella Mbandaka), all others were isolated from macadamia nuts and pistachios. In macadamia nuts, five different serotypes were found (Salmonella serotypes diarizonae O61, diarizonae N.N., Urbana, Muenchen, and Give) and six different serotypes were isolated in pistachios (Salmonella serotypes Liverpool, Senftenberg, Montevideo, Worthington, Mbandaka, and Duisburg). Salmonella Give and Salmonella Senftenberg were each isolated three times from macadamia and pistachios, respectively; all Salmonella Give isolates were found in macadamia nuts and all Salmonella Senftenberg isolates were found in pistachios. PFGE patterns of Salmonella Give isolates SAMN04413828 and SAMN04451260 were the same (by restriction enzyme BlnI) or similar (by restriction enzyme XbaI) (Figure 2). PFGE profiles of Salmonella Senftenberg isolates SAMN06125464 and SAMN04451263 were the same (by restriction enzyme XbaI) or similar (by restriction enzyme BlnI); they also formed a small cluster with Salmonella Senftenberg isolate SAMN04549535 by both enzymes (Figure 2). The PFGE profile similarities indicate that they were from the same environmental source.

Table 3.

Serotypes and NCBI accession numbers of Salmonella isolates recovered from raw, shelled tree nut samples

| Sample code | NCBI accession number a | Sampling date | Nut | Store type | Salmonella serotype | MPN/g,[95% CI] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1108208‐28 | SAMN04396122 | 12/28/2015 | Cashews | Discount, variety, or drug stores | Mbandaka | <0.003 [N/A, N/A] |

| 1108793‐11 | SAMN04500976 | 2/6/2016 | Macadamia Nuts | Small Chain | diarizonae O61 | 0.0036 [0.00, 0.03] |

| 1110945‐01 | SAMN05359991 | 6/9/2016 | Macadamia Nuts | Discount, variety, or drug stores | Urbana | <0.003 [N/A, N/A] |

| 1112207‐05 | SAMN05784536 | 8/13/2016 | Macadamia Nuts | Major or big Chain | Muenchen | <0.003 [N/A, N/A] |

| 1108248‐25 | SAMN04413829 | 12/31/2015 | Macadamia Nuts, organic | Discount, variety, or drug stores | diarizonae N.N. | <0.003 [N/A, N/A] |

| 1108248‐26 | SAMN04413830 | 12/31/2015 | Macadamia Nuts, organic | Discount, variety, or drug stores | Give | 0.15 [0.01, 0.52] |

| 1108261‐12 | SAMN04413828 | 1/2/2016 | Macadamia Nuts, organic | Discount, variety, or drug stores | Give | 0.75 [0.18, 3.20] |

| 1108447‐08 | SAMN04451260 | 1/16/2016 | Macadamia Nuts, organic | Discount, variety, or drug stores | Give | <0.003 [N/A, N/A] |

| 1108448‐10 | SAMN04451261 | 1/16/2016 | Pistachios | Major or big Chain | Liverpool | <0.003 [N/A, N/A] |

| 1108480‐16 | SAMN04451263, SAMN04451264 | 1/19/2016 | Pistachios | Online | Senftenberg Montevideo | 0.092 [0.02, 0.37] |

| 1109149‐08 | SAMN04549535 | 2/27/2016 | Pistachios | Major or big Chain | Senftenberg | 0.0036 [0.00, 0.03] |

| 1110485‐14 | SAMN05181543, SAMN05181544 | 5/17/2016 | Pistachios | Online | Worthington Montevideo | 0.0092 [0.00, 0.04] |

| 1114245‐01 | SAMN06125464 | 11/30/2016 | Pistachios | Major or big Chain | Senftenberg | <0.003 [N/A, N/A] |

| 1114461‐01 | SAMN06213901 | 12/9/2016 | Pistachios | Online | Mbandaka | <0.003 [N/A, N/A] |

| 1108480‐10 | SAMN04451262 | 1/19/2016 | Pistachios, organic | Online | Duisburg | <0.003 [N/A, N/A] |

Note. MPN was estimated by a three‐tube, five‐dilution (100, 10, 1.0, 0.1, and 0.01 g) assay.

NCBI accession number is isolate identification number assigned by the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) in their database.

Abbreviation: CI, Clopper–Pearson's 95% confidence interval.

Figure 2.

PFGE profiles of Salmonella isolates recovered from raw, shelled tree nuts. Profiles (A) was obtained using restriction enzyme XbaI and (B) restriction enzyme BlnI.

In our previous survey of Salmonella prevalence on tree nuts in the United States (Zhang, Hu, Melka, et al., 2017), a total of 12 serotypes (15 isolates) were isolated from macadamia nuts. In the current survey, there were five serotypes (seven isolates) isolated. Only Salmonella enterica subsp. diarizonae was observed in both surveys. These results showed there is wide genetic variation of Salmonella isolated from macadamia nuts, in both the 2014 to 2015 survey and the 2015 to 2016 survey. Among the 11 serotypes of Salmonella obtained in the current nationwide survey from various nuts (Table 3), only Salmonella Muenchen was on the CDC's top 10 culture‐confirmed Salmonella infections list (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2016a). More information on contamination at different points in the supply chain among producers is needed to interpret these data. We hypothesize that environments where macadamia nuts were produced may be favorable for Salmonella survival. In‐depth investigation of the environment to figure out the factors beneficial for Salmonella survival might help the industry develop better mitigation strategies to control Salmonella.

There were reports on diverse Salmonella populations of isolates recovered from tree nuts and peanuts revealed by serotype and PFGE data, which are similar to our current observations of the isolates obtained in this project (Calhoun et al., 2013; Danyluk et al., 2007; Harris et al., 2016; Zhang, Hu, Melka, et al., 2017). This phenomenon might be caused by the diverse nut production environments, soil contamination during harvesting, and subsequent contamination during processing and in storage facilities. Soil harbors an extremely diverse and complicated microbiota. Soil and dust are heavily involved in harvesting and processing of tree nuts, creating more chances of contamination of nuts.

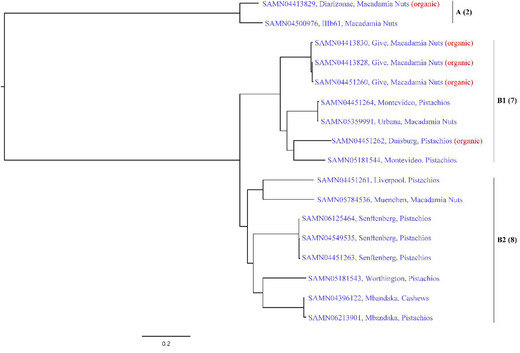

3.4. Genomics of Salmonella isolates from tree nuts

Sequencing data and metadata of the 17 isolates recovered from tree nuts are available from the NCBI database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) with Accession Numbers listed in Table 3. The overall tree topology of Salmonella isolates constructed by kSNP3.0 was concordant with what is obtained when inferring the unfiltered SNP matrix generated by CFSAN SNP pipeline (Figure 3). Two major lineages (Clade A and B) were exhibited among these isolates. Clade A only contained two isolates, S. enterica subsp. diarizonae N.N. (organic macadamia nuts) and S. enterica subsp. diarizonae O61 (macadamia nuts), which was an early diverging lineage to the remaining isolates in Clade B. Clade B is consisted of B1 (seven isolates) and B2 (eight isolates). Previous reports on phylogenetic analysis of Salmonella also revealed two sister lineages for the subspecies (den Bakker et al., 2011; Timme et al., 2013).

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic analysis of Salmonella isolates recovered from contaminated raw, shelled tree nut samples. Diarizonae represents S. enterica subsp. diarizonae N.N.; IIIb61 represents S. enterica subsp. diarizonae O61.

Our data showed that Clade B1 included Salmonella serotypes Give, Montevideo, Urbana, and Duisburg, whereas Clade B2 contained serotypes Liverpool, Muenchen, Senftenberg, Worthington, and Mbandaka. All Salmonella isolates from organic tree nuts, except for SAMN04413829, belonged to Clade B1. The identified Salmonella Give isolates (SAMN04413828 and SAMN04451260) from organic macadamia nuts collected in 2015 were closely linked to Salmonella Give isolated from organic macadamia nuts collected in 2016 (Clade B1), with a distance of 541 to 614 SNPs (Table 4). Three isolates of Salmonella Senftenberg (SAMN06125464, SAMN04549535, and SAMN04451263) obtained from different times in 2016 were all shown in Clade B2 and might be recognized as the same one, due to the close distance between each other (<100 bp). The two Salmonella Mbandaka isolated from cashews in 2015 and pistachios in 2016 were genetically close (279 SNPs difference). In addition, the phylogenetic tree by WGS was similar to the obtained PFGE profiles with different restriction enzymes, XbaI and BlnI (Table 4 and Figure 2). Although it is able to discriminate among Salmonella isolates in a general manner, PFGE might be insufficient when very closely related strains are analyzed and lack the resolution necessary to reveal differences between isolates from the same outbreak; WGS is better fit to solve this problem with a higher level of resolution (Allard et al., 2012; Boxrud et al., 2007). WGS and bioinformatic analyses are revolutionizing the field of Salmonella genomics by rapidly mining sufficient information for the surveillance and investigation of Salmonella outbreaks. Increasing international use of WGS in parallel with other techniques such as PFGE and MLVA hints at their eventual displacement by WGS for typing Salmonella (Nadon et al., 2017; Rantsiou et al., 2017).

Table 4.

Pairwise SNP distances (number of nucleotide differences) between the Salmonella isolates from contaminated tree nut samples

| SAMN04 | SAMN04 | SAMN05 | SAMN04 | SAMN05 | SAMN04 | SAMN04 | SAMN04 | SAMN04 | SAMN04 | SAMN05 | SAMN05 | SAMN04 | SAMN06 | SAMN04 | SAMN04 | SAMN06 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 413829 | 500976 | 359991 | 451262 | 181543 | 451264 | 413830 | 451260 | 413828 | 451261 | 784536 | 181544 | 396122 | 213901 | 549535 | 451263 | 125464 |

| SAMN04 | ||||||||||||||||

| 413829 | ||||||||||||||||

| SAMN04 | 11,941 | |||||||||||||||

| 500976 | ||||||||||||||||

| SAMN05 | 140,578 | 139,559 | ||||||||||||||

| 359991 | ||||||||||||||||

| SAMN04 | 139,107 | 137,990 | 30,754 | |||||||||||||

| 451262 | ||||||||||||||||

| SAMN05 | 139,457 | 138,565 | 31,101 | 31,180 | ||||||||||||

| 181543 | ||||||||||||||||

| SAMN04 | 139,494 | 138,608 | 31,140 | 31,226 | 102 | |||||||||||

| 451264 | ||||||||||||||||

| SAMN04 | 141,373 | 140,259 | 32,102 | 31,605 | 31,101 | 31,081 | ||||||||||

| 413830 | ||||||||||||||||

| SAMN04 | 141,273 | 140,163 | 32,010 | 31,494 | 30,945 | 30,957 | 614 | |||||||||

| 451260 | ||||||||||||||||

| SAMN04 | 141,352 | 140,239 | 32,042 | 31,564 | 31,021 | 31,007 | 541 | 101 | ||||||||

| 413828 | ||||||||||||||||

| SAMN04 | 139,527 | 138,320 | 53,924 | 53,559 | 53,735 | 53,845 | 55,174 | 54,971 | 55,144 | |||||||

| 451261 | ||||||||||||||||

| SAMN05 | 140,289 | 139,405 | 53,879 | 53,558 | 53,434 | 53,638 | 55,147 | 55,016 | 55,183 | 42,137 | ||||||

| 784536 | ||||||||||||||||

| SAMN05 | 135,986 | 134,965 | 44,677 | 44,396 | 44,388 | 44,500 | 45,674 | 45,575 | 45,689 | 41,309 | 40,987 | |||||

| 181544 | ||||||||||||||||

| SAMN04 | 139,842 | 139,003 | 50,282 | 50,072 | 50,298 | 50,363 | 51,554 | 51,445 | 51,505 | 47,097 | 46,844 | 32,360 | ||||

| 396122 | ||||||||||||||||

| SAMN06 | 139,628 | 138,793 | 49,980 | 49,626 | 49,954 | 50,014 | 51,216 | 51,115 | 51,175 | 46,817 | 46,437 | 32,092 | 279 | |||

| 213901 | ||||||||||||||||

| SAMN04 | 140,492 | 139,465 | 51,139 | 50,969 | 50,673 | 50,738 | 52,465 | 52,410 | 52,492 | 46,273 | 45,742 | 35,321 | 41,818 | 41,491 | ||

| 549535 | ||||||||||||||||

| SAMN04 | 140,514 | 139,468 | 51,155 | 50,925 | 50,633 | 50,725 | 52,502 | 52,295 | 52,438 | 46,287 | 45,722 | 35,317 | 41,872 | 41,546 | 92 | |

| 451263 | ||||||||||||||||

| SAMN06 | 140,556 | 139,489 | 51,243 | 51,027 | 50,724 | 50,810 | 52,602 | 52,427 | 52,550 | 46,375 | 45,825 | 35,378 | 41,957 | 41,622 | 69 | 53 |

| 125464 |

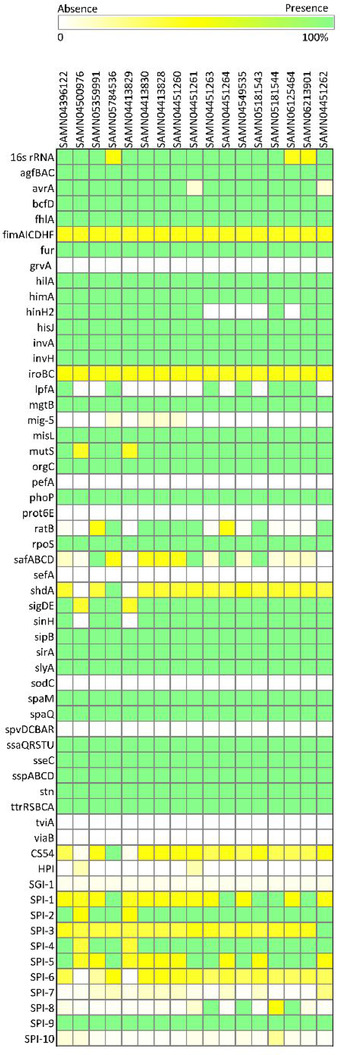

Figure 4 shows that all 17 Salmonella isolates contained many genes/gene clusters studied, such as 16s rRNA, agfBAC, bcfD, fhlA, fur, hilA, himA, hisJ, invA, invH, mgtB, misL, orgC, phoP, rpoS, sipB, sirA, slyA, ssaQRSTU, sseC, sspABCD, stn, and ttrRSBCA. Genes grvA, pefA, prot6E, sefA, sodC, spvDCBAR, tviA, and viaB were completely absent from all these isolates. Some genes only occurred in certain serotypes. For example, avrA gene had low existence (17%) in Salmonella Duisburg and Liverpool, although highly present in other serotypes. sinH gene was absent from the two S. enterica subsp. diarizonae, highly present in the rest of the isolates. ratB gene was present in Salmonella Duisburg, Liverpool, IIIb61, Urbana, Muenchen, Montevideo, and Give; it was absent from most other isolates. shdA gene was absent from S. enterica subsp. diarizonae isolates, and partially present in other serotypes (>72%). In addition, both gene clusters of fimAICDHF (>86%) and iroBC (>89%) were partially present in all Salmonella isolates.

Figure 4.

Presence or absence of virulence genes and gene clusters detected in Salmonella isolates from contaminated raw, shelled tree nut samples.

For the 13 SPIs studied (Figure 4), SGI‐1 was present at <8% among the 17 Salmonella isolates. SPI‐1, SPI‐2, SPI‐3, SPI‐4, and SPI‐9 were present in all isolates. SPI‐5 was prevalent at 73 to 100% among these isolates. SPI‐6 was absent in S. enterica subsp. diarizonae (SAMN04413829 and SAMN04500976) isolates. SPI‐8 was present at 4% and 99% in Salmonella Montevideo isolates SAMN04451264 and SAMN05181544, respectively; and all three Salmonella Senftenberg isolates contained SPI‐8. SPI‐7 was present at <20% in S. enterica subsp. diarizonae, Liverpool, Urbana, Mbandaka, Senftenberg, and Montevideo (SAMN05181544) and at 20 to 49% in other isolates. SPI‐10 sequence was missing in all isolates except for Salmonella Montevideo isolate SAMN05181544, where it was present at 42%. HPI was completely absent from these isolates except for Salmonella Liverpool and IIIb61 (30 to 32%). SPIs 1 to 5 were widespread in genus Salmonella. SPI‐6 was mainly present in Salmonella subspecies I, IIIb, IV, and VII. SPI‐7, SPI‐9, SPI‐10, and SGI‐1 were frequently observed in subspecies I. SPI‐8 was common in Salmonella Typhi. HPI often occurred in Salmonella subspecies IIIa, IIIb, and IV (Hensel, 2004). The gain/loss/mutation of virulence determinant genes and SPIs among the different subspecies and serovars might have contributed to the elevated level of diversities in Salmonella genus. Additionally, the acquisition of SPIs by horizontal gene transfer is often reflected in the base composition of SPIs that are different from that of the core genome of the host, and the association with insertion sites such as tRNA genes (Lamas et al., 2017).

4. CONCLUSION

Salmonella was not detected in 2,291 samples of raw, shelled Brazil nuts, hazelnuts, pecans, pine nuts, and walnuts collected from U.S. retail outlets. In contrast, 17 isolates from 11 serotypes were recovered from 15 of 1,083 samples of contaminated raw, shelled cashews, macadamia nuts, or pistachios. The rate of Salmonella isolation from major/big chain‐supermarkets, small‐chain supermarkets, discount/variety/drug stores, and online was 0.29% (95% CI [0.08, 0.74]), 0.30% (95% CI [0.01, 1.69]), 0.45% (95% CI [0.17, 0.98]), and 1.19% (95% CI [0.33, 3.02]), respectively. The majority of contaminated samples had very low numbers of Salmonella cells (≤0.0092 MPN/g nuts), with the highest contamination level observed being 0.75 MPN/g on a sample of macadamia nuts. More surveillances and surveys should be considered for macadamia and pistachios, including the environments where they are produced. The contamination levels of Salmonella in the tree nuts analyzed were generally comparable to previous reports. Prevalence estimates for walnuts, hazelnuts, and pine nuts were smaller than those observed in the similarly structured 2014 to 2015 survey. Detailed information on the contamination levels at harvest and production processes for these and other tree nuts may help reveal the source of this variability.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

G. Zhang and T. Hammack designed the study and collected the data. L. Hu and G. Zhang analyzed the data. G. Zhang and L. Hu interpreted the results and wrote the manuscript. All other authors reviewed and revised the manuscript.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Mention of trade names or commercial products in the paper is solely for the purpose of providing scientific information and does not imply recommendation or endorsement by the U. S. Food and Drug Administration.

REFERENCES

- Abd, S. J. , McCarthy, K. L. , & Harris, L. J. (2012). Impact of storage time and temperature on thermal inactivation of Salmonella Enteritidis PT 30 on oil‐roasted almonds. Journal of Food Science, 77(1), M42–M47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al‐Moghazy, M. , Boveri, S. , & Pulvirenti, A. (2014). Microbiological safety in pistachios and pistachio containing products. Food Control, 36(1), 88–93. [Google Scholar]

- Allard, M. W. , Luo, Y. , Strain, E. , Li, C. , Keys, C. E. , Son, I. , … Brown, E. W. (2012). High resolution clustering of Salmonella enterica serovar Montevideo strains using a next‐generation sequencing approach. BMC Genomics, 13, 32 10.1186/1471-2164-13-32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allard, M. W. , Strain, E. , Melka, D. , Bunning, K. , Musser, S. M. , Brown, E. W. , & Timme, R. (2016). Practical value of food pathogen traceability through building a whole‐genome sequencing network and database. Journal of Clinical Microbiology, 54(8), 1975–1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atungulu, G. , & Pan, Z. (2012). Microbial decontamination of nuts and spices In Demirci A. & Mgadi M. O. (Eds.), Microbial decontamination in the food industry (pp. 125–162). Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Bansal, A. , Jones, T. M. , Abd, S. J. , Danyluk, M. D. , & Harris, L. J. (2010). Most‐probable‐number determination of Salmonella levels in naturally contaminated raw almonds using two sample preparation methods. Journal of Food Protection, 73(11), 1986–1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedard, B. , Kennedy, B. , & Weimer, A. (2014). Geographical information software and shopper card data, aided in the discovery of a Salmonella Enteritidis outbreak associated with Turkish pine nuts. Epidemiology and Infection, 142(12), 2567–2571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blessington, T. , Theofel, C. G. , Mitcham, E. J. , & Harris, L. J. (2013). Survival of foodborne pathogens on inshell walnuts. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 166(3), 341–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges, K. A. , Furian, T. Q. , de Souza, S. N. , Menezes, R. , Salle, C. T. P. , de Souza Moraes, H. L. , … do Nascimento, V. P. (2017). Phenotypic and molecular characterization of Salmonella Enteritidis SE86 isolated from poultry and salmonellosis outbreaks. Foodborne Pathogens and Disease, 14(12), 742–754. 10.1089/fpd.2017.2327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boxrud, D. , Pederson‐Gulrud, K. , Wotton, J. , Medus, C. , Lyszkowicz, E. , Besser, J. , & Bartkus, J. M. (2007). Comparison of multiple‐locus variable‐number tandem repeat analysis, pulsed‐field gel electrophoresis, and phage typing for subtype analysis of Salmonella enterica serotype Enteritidis. Journal of Clinical Microbiology, 45(2), 536–543. 10.1128/JCM.01595-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brar, P. K. , Strawn, L. K. , & Danyluk, M. D. (2016). Prevalence, level, and types of Salmonella isolated from north American in‐shell pecans over four harvest years. Journal of Food Protection, 79(3), 352–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calhoun, S. , Post, L. , Warren, B. , Thompson, S. , & Bontempo, A. R. (2013). Prevalence and concentration of Salmonella on raw shelled peanuts in the United States. Journal of Food Protection, 76(4), 575–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camacho, C. , Coulouris, G. , Avagyan, V. , Ma, N. , Papadopoulos, J. , Bealer, K. , & Madden, T. L. (2009). BLAST+: Architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics, 10(1), 421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Food Inspection Agency . (2011). Certain bulk and prepackaged raw shelled walnuts may contain E. coli O157:H7 bacteria . Retrieved from http://healthycanadians.gc.ca/recall-alert-rappel-avis/inspection/2011/17101r-eng.php

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . (2011a). Multistate outbreak of E. coli O157:H7 infections associated with in‐shell hazelnuts (Final update) . Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/ecoli/2011/hazelnuts-4-7-11.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . (2011b). Multistate outbreak of human Salmonella Enteritidis infections linked to Turkish pine nuts (Final update) . Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/salmonella/2011/pine-nuts-11-17-2011.html?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Fsalmonella%2Fpinenuts-enteriditis%2Findex.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . (2014a). Multistate outbreak of Salmonella Braenderup infections linked to nut butter manufactured by nSpired Natural Foods, Inc. (Final update) . Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/salmonella/braenderup-08-14/index.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . (2014b). Multistate outbreak of Salmonella Stanley infections linked to raw cashew cheese (Final update) . Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/salmonella/stanley-01-14/index.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . (2016a). Foodborne diseases active surveillance network: Number of infections and incidences per 100,000 persons . Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/foodnet/reports/data/infections.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . (2016b). Multistate outbreak of Salmonella Montevideo and Salmonella Senftenberg infections linked to wonderful pistachios (Final update) . Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/salmonella/montevideo-03-16/index.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . (2016c). PulseNet methods . Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/pulsenet/pathogens/index.html

- Danyluk, M. D. , Jones, T. M. , Abd, S. J. , Schlitt‐Dittrich, F. , Jacobs, M. , & Harris, L. J. (2007). Prevalence and amounts of Salmonella found on raw California almonds. Journal of Food Protection, 70(4), 820–827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, G. R. , Frelka, J. C. , Yang, M. , Jones, T. M. , & Harris, L. J. (2015). Prevalence of Escherichia coli O157: H7 and Salmonella on inshell California walnuts. Journal of Food Protection, 78(8), 1547–1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis, S. , Pettengill, J. B. , Luo, Y. , Payne, J. , Shpuntoff, A. , Rand, H. , & Strain, E. (2015). CFSAN SNP pipeline: An automated method for constructing SNP matrices from next‐generation sequence data. PeerJ ‐ Computer Science, 1, e20. [Google Scholar]

- den Bakker, H. C. , Switt, A. I. M. , Govoni, G. , Cummings, C. A. , Ranieri, M. L. , … Bolchacova, E. (2011). Genome sequencing reveals diversification of virulence factor content and possible host adaptation in distinct subpopulations of Salmonella enterica . BMC Genomics, 12(1), 425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eglezos, S. (2010). The bacteriological quality of retail‐level peanut, almond, cashew, hazelnut, Brazil, and mixed nut kernels produced in two Australian nut‐processing facilities over a period of 3 years. Foodborne Pathogens and Disease, 7(7), 863–866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eglezos, S. , Huang, B. , & Stuttard, E. (2008). A survey of the bacteriological quality of preroasted peanut, almond, cashew, hazelnut, and Brazil nut kernels received into three Australian nut‐processing facilities over a period of 3 years. Journal of Food Protection, 71(2), 402–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng, L. , Muyyarikkandy, M. , Brown, S. , & Amalaradjou, M. (2018). Attachment and survival of Escherichia coli O157: H7 on in‐shell hazelnuts. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(6), 1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foodborne Illness Outbreak Database . (2000). International outbreak involving whole, raw, almonds 2000 . Retrieved from http://outbreakdatabase.com/details/international-outbreak-involving-whole-raw-almonds-2000/?vehicle=nut

- Frelka, J. C. , Davidson, G. R. , & Harris, L. J. (2016). Changes in aerobic plate and Escherichia coli–coliform counts and in populations of inoculated foodborne pathogens on inshell walnuts during storage. Journal of Food Protection, 79(7), 1143–1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, S. N. , Slezak, T. , & Hall, B. G. (2015). kSNP3. 0: SNP detection and phylogenetic analysis of genomes without genome alignment or reference genome. Bioinformatics, 31(17), 2877–2878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorski, L. , Parker, C. T. , Liang, A. , Cooley, M. B. , Jay‐Russell, M. T. , Gordus, A. G. , … Microbiology, E. (2011). Prevalence, distribution and diversity of Salmonella enterica in a major produce region of California. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 77(8), 2734–2748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimont, P. A. , & Weill, F.‐X. (2007). Antigenic formulae of the Salmonella serovars. WHO Collaborating Centre for Reference and Research on Salmonella . Retrieved from https://www.pasteur.fr/sites/default/files/veng_0.pdf. Accessed 25 December 2020.

- Harris, L. J. , Lieberman, V. , Mashiana, R. P. , Atwill, E. , Yang, M. , Chandler, J. C. , … Jones, T. (2016). Prevalence and amounts of Salmonella found on raw California inshell pistachios. Journal of Food Protection, 79(8), 1304–1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hensel, M. (2004). Evolution of pathogenicity islands of Salmonella enterica . International Journal of Medical Microbiology, 294(2‐3), 95–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimber, M. A. , Kaur, H. , Wang, L. , Danyluk, M. D. , & Harris, L. J. (2012). Survival of Salmonella, Escherichia coli O157: H7, and Listeria monocytogenes on inoculated almonds and pistachios stored at −19, 4, and 24°C. Journal of Food Protection, 75(8), 1394–1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamas, A. , Miranda, J. M. , Regal, P. , Vazquez, B. , Franco, C. M. , & Cepeda, A. (2017). A comprehensive review of non‐enterica subspecies of Salmonella enterica . Microbiological Research, 206, 60–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin, R. E. (2009). The use of molecular methods for detecting and discriminating Salmonella associated with foods—A review. Food Biotechnology, 23(4), 313–367. 10.1080/08905430903320982 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Little, C. , Jemmott, W. , Surman‐Lee, S. , Hucklesby, L. , & De Pinna, E. (2009). Assessment of the microbiological safety of edible roasted nut kernels on retail sale in England, with a focus on Salmonella . Journal of Food Protection, 72(4), 853–855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukinmaa, S. , Schildt, R. , Rinttilä, T. , & Siitonen, A. (1999). Salmonella Enteritidis phage types 1 and 4: Pheno‐and genotypic epidemiology of recent outbreaks in Finland. Journal of Clinical Microbiology, 37(7), 2176–2182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ly, V. , Parreira, V. R. , & Farber, J. M. (2019). Current understanding and perspectives on Listeria monocytogenes in low‐moisture foods. Current Opinion in Food Science, 26, 18–24. [Google Scholar]

- Miksch, R. R. , Leek, J. , Myoda, S. , Nguyen, T. , Tenney, K. , Svidenko, V. , … Samadpour, M. (2013). Prevalence and counts of Salmonella and enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli in raw, shelled runner peanuts. Journal of Food Protection, 76(10), 1668–1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadon, C. , Van Walle, I. , Gerner‐Smidt, P. , Campos, J. , Chinen, I. , Concepcion‐Acevedo, J. , … Perez, E. (2017). PulseNet International: Vision for the implementation of whole genome sequencing (WGS) for global food‐borne disease surveillance. Eurosurveillance, 22(23), 30544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker, C. T. , Huynh, S. , Quiñones, B. , Harris, L. J. , & Mandrell, R. E. (2010). Comparison of genotypes of Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis phage type 30 and 9c strains isolated during three outbreaks associated with raw almonds. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 76(11), 3723–3731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price, M. N. , Dehal, P. S. , & Arkin, A. P. (2010). FastTree 2 ‐ Approximately maximum‐likelihood trees for large alignments. PLoS ONE, 5(3), e9490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rantsiou, K. , Kathariou, S. , Winkler, A. , Skandamis, P. , Saint‐Cyr, M. J. , Rouzeau‐Szynalski, K. , & Amézquita, A. (2017). Next generation microbiological risk assessment: Opportunities of whole genome sequencing (WGS) for foodborne pathogen surveillance, source tracking and risk assessment. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 287, 3–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santillana Farakos, S. M. , Pouillot, R. , Davidson, G. R. , Johnson, R. , Spungen, J. , Son, I. , … Doren, J. M. V. (2018). A quantitative risk assessment of human salmonellosis from consumption of pistachios in the United States. Journal of Food Protection, 81(6), 1001–1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santillana Farakos, S. M. , Pouillot, R. , & Keller, S. E. (2017). Salmonella survival kinetics on pecans, hazelnuts, and pine nuts at various water activities and temperatures. Journal of Food Protection, 80(5), 879–885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, H. , & Hensel, M. (2004). Pathogenicity islands in bacterial pathogenesis. Clinical Microbiology Reviews, 17(1), 14–56. 10.1128/cmr.17.1.14-56.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timme, R. E. , Pettengill, J. B. , Allard, M. W. , Strain, E. , Barrangou, R. , Wehnes, C. , … Brown, E. W. (2013). Phylogenetic diversity of the enteric pathogen Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica inferred from genome‐wide reference‐free SNP characters. Genome Biology and Evolution, 5(11), 2109–2123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U. S. Food and Drug Administration . (2017). BAM Appendix 2: Most Probable Number from serial dilutions . Retrieved from https://www.fda.gov/Food/FoodScienceResearch/LaboratoryMethods/ucm109656.htm

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration . (2013). Assessment of the risk of human salmonellosis associated with the consumption of tree nuts; request for comments, scientific data and information . Retrieved from https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2013/07/18/2013-17211/assessment-of-the-risk-of-human-salmonellosis-associated-with-the-consumption-of-tree-nuts-request

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration . (2018). Bacteriological Analytical Manual (BAM) Chapter 5: Salmonella . Retrieved from https://www.fda.gov/food/foodscienceresearch/laboratorymethods/ucm070149.htm

- Yada, S. , & Harris, L. J. (2019). Recalls of tree nuts and peanuts in the U.S., 2001 to present (version 2) [Table and references] . Retrieved from http://ucfoodsafety.ucdavis.edu/Nuts_and_Nut_Pastes/. Accessed 25 December 2020.

- Zhang, G. , Chen, Y. , Hu, L. , Melka, D. , Wang, H. , Laasri, A. , … Hammack, S. T. (2018). Survey of foodborne pathogens, aerobic plate counts, total coliform counts, and Escherichia coli counts in leafy greens, sprouts, and melons marketed in the United States. Journal of Food Protection, 81(3), 400–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G. , Hu, L. , Melka, D. , Wang, H. , Laasri, A. , Brown, E. W. , … Hammack, S. T. (2017). Prevalence of Salmonella in cashews, hazelnuts, macadamia nuts, pecans, pine nuts, and walnuts in the United States. Journal of Food Protection, 80(3), 459–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G. , Hu, L. , Pouillot, R. , Tatavarthy, A. , Doren, J. M. V. , Kleinmeier, D. , … Hammack, S. T. (2017). Prevalence of Salmonella in 11 spices offered for sale from retail establishments and in imported shipments offered for entry to the United States. Journal of Food Protection, 80(11), 1791–1805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]