Abstract

Aims

To synthesize the qualitative evidence of the views and experiences of people living with dementia, family carers, and practitioners on practice related to nutrition and hydration of people living with dementia who are nearing end of life.

Design

Systematic review and narrative synthesis of qualitative studies.

Data sources

MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO, CINAHL.

Review methods

Databases were searched for qualitative studies from January 2000‐February 2020. Quantitative studies, or studies reporting on biological mechanisms, assessments, scales or diagnostic tools were excluded. Results were synthesized using a narrative synthesis approach with thematic analysis.

Results

Twenty studies were included; 15 explored the views of practitioners working with people living with dementia in long‐term care settings or in hospitals. Four themes were developed: challenges of supporting nutrition and hydration; balancing the views of all parties involved with ‘the right thing to do’; national context and sociocultural influences; and strategies to support nutrition and hydration near the end of life in dementia.

Conclusion

The complexity of supporting nutrition and hydration near the end of life for someone living with dementia relates to national context, lack of knowledge, and limited planning while the person can communicate.

Impact

This review summarizes practitioners and families’ experiences and highlights the need to include people living with dementia in studies to help understand their views and preferences about nutrition and hydration near the end of life; and those of their families supporting them in the community. The review findings are relevant to multidisciplinary teams who can learn from strategies to help with nutrition and hydration decisions and support.

Keywords: artificial nutrition and hydration, carers, dementia, end of life, experiences, nurse, nutrition and hydration, practitioners, qualitative, systematic review

摘要

目的

综合痴呆患者、家庭护理员以及执业医师对与痴呆患者临终前的营养和水分补充相关实践的观点和经验的定性证据。

设计

对定性研究进行系统评估和叙事综合。

数据来源

MEDLINE、Embase、PsycINFO和CINAHL。

评估方法

对数据库自2000年1月至2020年2月期间的数据进行检索。不包括定量研究或生物机制的研究报告、评估、量表或诊断工具。使用叙事综合方法和主题分析,以综合汇总结果。

结果

共纳入20项研究。其中,15项探讨了在长期护理环境或医院为痴呆患者服务的执业医师的观点。其中,4项主题探讨了:提供营养和水分补充所面临的挑战;平衡‘正确做法’涉及的各方观点;国家背景和社会文化影响;以及为痴呆患者在临终前提供营养和水分补充的策略。

结论

为痴呆患者在临终前提供营养和水分补充的复杂性,与国家背景、知识匮乏和在患者可以交流时的有限规划有关。

影响

本评估概述了执业医师和家庭的经验,强调了将痴呆患者纳入研究的必要性,以帮助理解他们在临终时的观点和对营养和水分补充的偏好;以及那些在社区中支持他们的家庭。评估研究结果与多个专业团队有关,其可从策略中进行学习,以帮助做出营养和水分补充的决定和支持。

1. INTRODUCTION

It is estimated that 47 million people were living with dementia in 2015, expected to increase to 132 million by 2050 worldwide (WHO, 2017). Difficulties with eating and drinking affecting nutrition and hydration are common among people living with dementia and might develop at different times depending on the type and progression of dementia (Cipriani et al., 2016; Ikeda et al., 2002). In the earlier stages of dementia an individual may sometimes forget to eat and drink and experience changes in perceptions of food, including altered taste and smell (Sandilyan, 2011). As dementia develops, apraxia or a lack of attention might develop, making it difficult for the person to feed themselves (Sampson et al., 2009; Volkert et al., 2015). Some might struggle to recognize food, reject food, or not feel hungry (Harwood, 2014).

1.1. Background

As someone living with dementia approaches end of life, their symptoms may worsen and new difficulties can emerge, such as swallowing problems (Sampson et al., 2017) which affect over 80% of those nearing the end of life (Baijens et al., 2016). Swallowing problems, or dysphagia, together with the symptoms associated to the progression of dementia (e.g., apraxia) may lead to malnutrition, dehydration, weight loss, aspiration and pneumonia (Alagiakrishnan et al., 2013; Arcand, 2015; Guigoz et al., 2006; Neuberger, 2013; White et al., 1996). These problems often lead to a dilemma among practitioners and families over what is best for the person living with dementia (Watt et al., 2019).

The use of Artificial Nutrition and Hydration (ANH) is sometimes considered. Despite a lack of evidence to support the use of ANH for people living with dementia (Sampson et al., 2009), it is unclear to what extent this knowledge reaches family carers and practitioners working with people living with dementia near the end of life. There is reported to be a lack of understanding of how best to manage nutrition and hydration difficulties (Alagiakrishnan et al., 2013; Nell et al., 2016) and what strategies to use to support intake (Ball et al., 2015).

2. THE REVIEW

2.1. Aims

This review aims to synthesize the qualitative evidence of the views and experiences of people living with dementia, family carers, and practitioners on practice related to nutrition and hydration of people living with dementia near the end of life. An inclusive approach to defining end of life was chosen by using the term “near the end of life” and including research referring to palliative care, the later, advanced, severe or end of life stages of dementia conducted in any setting.

While the aim of the review was broad we were also guided by, but not limited to more specific questions including: (a) What is the level of knowledge and understanding of nutrition and hydration near the end of life?; (b) What strategies do family carers and practitioners (including nurses, doctors, healthcare assistants and other staff in the community, hospitals or long‐term care settings) use to support nutrition and hydration for a person living with dementia near the end of life?; (c) What help is needed to better support nutrition and hydration for the person living with dementia near the end of life?; and (d) What are the views and experiences about provision of artificial nutrition and hydration for people with dementia near the end of life?

2.2. Design

A systematic review of qualitative studies following the guidelines from the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (2009) and reported using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analysis (PRISMA) Statement (Moher et al., 2009). The protocol for the review was registered and published with PROSPERO (CRD42019134299). Papers were included or excluded following the criteria summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Papers were included if they | Papers were excluded if they |

|---|---|

|

|

2.3. Search methods

We searched MEDLINE, CINAHL, Embase, and PsycINFO for articles published between January 2000‐25 February 2020. Keywords used were dementia, nutrition, hydration, palliative care and qualitative. Initial scoping searches were conducted to identify relevant search terms including index terms (Medical Subject Headings) and a comprehensive list of synonyms. An example search strategy from PsycINFO is provided in Supplementary Material A. Citations were tracked using Google Scholar and reference lists of all relevant papers were screened to identify any additional studies.

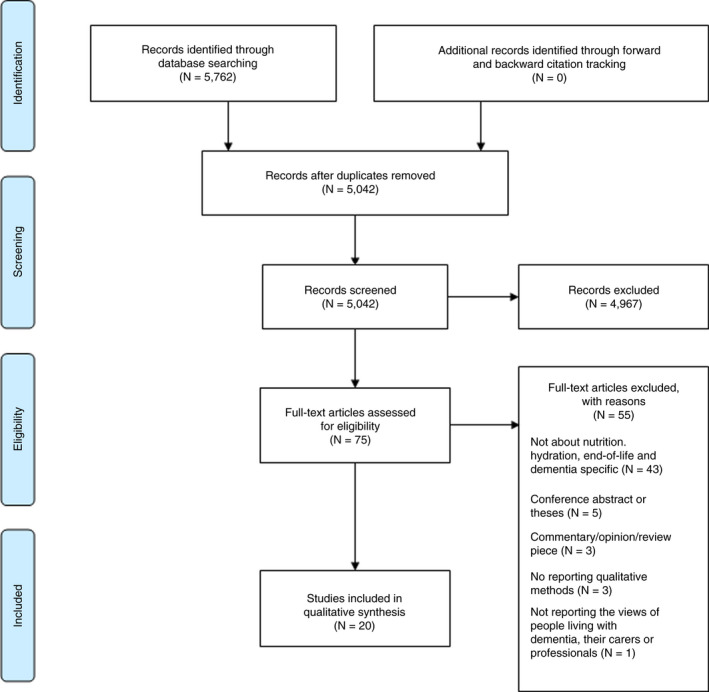

2.4. Search outcome and selection procedure

Duplicates were removed and titles and abstracts were screened by one reviewer (YBM or LH) against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. A second reviewer screened a random 20% of the titles and abstracts (either YBM or LH). Articles that were potentially eligible were read in full by one reviewer (YBM or LH). A second reviewer screened a random 20% of the excluded full texts (either YBM or LH). Both reviewers read all included articles (YBM and LH). Any disagreements regarding inclusion between the two reviewers were resolved through discussion with a third reviewer (ND). Disagreement between both reviewers was rare and only lead to the exclusion of further papers at the title and abstract screening stage. Non‐English articles were rapidly appraised using English abstracts to check relevance. Experts in the field were contacted to identify any additional papers. Figure 1 shows the PRISMA flowchart.

FIGURE 1.

PRISMA Flow diagram summarizing the screening process [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

2.5. Quality appraisal

Quality of the included studies was appraised using the Critical Appraisal Skill Programme (CASP) qualitative checklist (2018) by LH and YBM. No studies were excluded based on quality, but the CASP checklist was used as a way to discuss the included papers and consider quality when weighting findings and the discussion. The CASP checklist does not provide cut offs for high and low quality in a dichotomous form so we have not classified studies as high or low quality but presented them in Table 4.

TABLE 4.

Quality appraisal of included papers

| Paper | Clear aims of research | Appropriateness of qualitative research | Appropriate research design | Appropriateness of the recruitment strategy | Data collected addressed the research issue | Adequate consideration of the relationship between researcher and participants | Considered ethical issues | Rigorous data analysis | Clear statement of findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aita et al. (2007) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Austbo Holteng et al. (2017) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Berkman et al. (2019) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Bryon et al. (2010) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Bryon De et al. (2012a) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Bryon et al. (2012) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Buiting et al. (2011) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Gessert et al. (2006) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Gil et al. (2018) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Kuven and Giske (2015) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Lopez and Amella (2011) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Lopez, Amella, Mitchell, et al. (2010) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Lopez, Amella, Strumpf, et al. (2010) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Pasman et al. (2004) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Pasman et al. (2003) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Smith et al. (2016) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Snyder et al. (2013) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| The et al. (2002) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Volicer and Stets (2016) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Wilmot et al. (2002) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

Ticked boxes represent “yes.” White boxes represent “no/can't tell.”

2.6. Data extraction and synthesis

We extracted the following data: author(s), year of publication, country of study, aims, study participants, sample size, study setting, methods, key findings, and conclusions. Data were extracted by YBM or LH and later crosschecked by each other. Any discrepancy was discussed and any disagreement discussed with a third reviewer (ND).

A narrative synthesis was used following guidance from the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) methods programme (Popay et al., 2006), using tabulation and thematic analysis methods. Analysis followed an inductive approach, two reviewers (YBM & LH) independently coded three papers to produce a coding frame. The two reviewers met to discuss their coding and agree a coding framework to be applied to all papers. The refined coding frame was applied to all papers by YBM with meetings throughout the coding process to discuss and amend the framework. Coding of all papers was shared with a third reviewer (ND) and the team met to discuss and explore relationships and hierarchies between codes, devising themes across the data. Preliminary themes were shared and discussed with all authors for further discussion and refinement.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Characteristics of included studies

Twenty papers were included (Table 2 for characteristics). These 20 papers related to 15 different research projects. An overview of included papers is provided in Table 3.

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of the included studies

| Characteristics | Papers |

|---|---|

| Year of publication | Six papers were published between 2000 and 2009 (Aita et al., 2007; Gessert et al., 2006; Pasman et al., 2003, 2004; The et al., 2002), and 14 between 2010 and 2020 (Austbo Holteng et al., 2017; Berkman et al., 2019; Bryon et al., 2012a; Bryon et al., 2010, 2012b; Buiting et al., 2011; Gil et al., 2018; Kuven & Giske, 2015; Lopez & Amella, 2011; Lopez, Amella, Mitchell, et al., 2010; Lopez, Amella, Strumpf, et al., 2010; Smith et al., 2016; Snyder et al., 2013; Volicer & Stets, 2016). |

| Study country | Most of these studies were based in the USA (N = 8) (Berkman et al., 2019; Gessert et al., 2006; Lopez & Amella, 2011; Lopez, Amella, Mitchell, et al., 2010; Lopez, Amella, Strumpf, et al., 2010; Smith et al., 2016; Snyder et al., 2013; Volicer & Stets, 2016) and The Netherlands (N = 4) (Buiting et al., 2011; Pasman et al., 2003, 2004; Volicer & Stets, 2016), followed by Belgium (N = 3) (Bryon et al., 2012; Bryon et al., 2010, 2012), Norway (N = 2) (Austbo Holteng et al., 2017; Kuven & Giske, 2015), Australia (N = 1) (Buiting et al., 2011), Israel (N = 1) (Gil et al., 2018), UK (N = 1) (Wilmot et al., 2002) and Japan (N = 1) (Aita et al., 2007). |

| Methods used | Studies used interview methods (N = 13) (Aita et al., 2007; Bryon et al., 2012a; Bryon et al., 2010, 2012; Buiting et al., 2011; Gil et al., 2018; Lopez & Amella, 2011; Lopez, Amella, Mitchell, et al., 2010; Lopez, Amella, Strumpf, et al., 2010; Pasman et al., 2003, 2004; Snyder et al., 2013; The et al., 2002), focus group methods (N = 6) (Austbo Holteng et al., 2017; Gessert et al., 2006; Kuven & Giske, 2015; Smith et al., 2016; Volicer & Stets, 2016; Wilmot et al., 2002), observational/ethnographic methods (N = 5) (Gil et al., 2018; Lopez, Amella, Strumpf, et al., 2010; Pasman et al., 2003, 2004; The et al., 2002) and open‐ended survey questions (N = 1) (Berkman et al., 2019). |

| Setting | Most studies reported data collected from long‐term care facilities (care homes or nursing homes) (N = 11) (Austbo Holteng et al., 2017; Berkman et al., 2019; Gessert et al., 2006; Gil et al., 2018; Lopez & Amella, 2011; Lopez, Amella, Mitchell, et al., 2010; Lopez, Amella, Strumpf, et al., 2010; Pasman et al., 2003, 2004; Snyder et al., 2013; The et al., 2002), followed by medical settings or hospitals (N = 9) (Aita et al., 2007; Berkman et al., 2019; Bryon et al., 2012a; Bryon et al., 2010, 2012; Buiting et al., 2011; Kuven & Giske, 2015; Volicer & Stets, 2016; Wilmot et al., 2002), and community settings (N = 4) (Berkman et al., 2019; Buiting et al., 2011; Lopez & Amella, 2011; Smith et al., 2016). |

| Participants | The majority of participants in these studies were practitioners (including nurses, doctors, healthcare assistants and other practitioners in hospitals or long‐term care settings) (N = 15) (Aita et al., 2007; Austbo Holteng et al., 2017; Berkman et al., 2019; Bryon et al., 2012a; Bryon et al., 2010, 2012b; Buiting et al., 2011; Kuven & Giske, 2015; Lopez, Amella, Mitchell, et al., 2010; Lopez, Amella, Strumpf, et al., 2010; Pasman et al., 2003, 2004; Smith et al., 2016; The et al., 2002; Wilmot et al., 2002), followed by family carers (N = 7) (Gessert et al., 2006; Gil et al., 2018; Lopez & Amella, 2011; Pasman et al., 2004; Snyder et al., 2013; The et al., 2002; Volicer & Stets, 2016) and people living with dementia (N = 3) (Pasman et al., 2003, 2004; The et al., 2002). People living with dementia were only included in observational studies (Pasman et al., 2003, 2004; The et al., 2002). |

| Central topic | Eleven studies focused on the use of ANH in dementia care, focusing on different practitioners’ perceptions and communication between practitioners involved in the decision making or implementation of ANH (Aita et al., 2007; Bryon et al., 2012a; Bryon et al., 2010, 2012b; Buiting et al., 2011; Gil et al., 2018; Lopez, Amella, Mitchell, et al., 2010; Lopez, Amella, Strumpf, et al., 2010; Pasman et al., 2004; Smith et al., 2016; The et al., 2002). The other nine studies focused broadly on nutrition and hydration in people with dementia (Austbo Holteng et al., 2017; Berkman et al., 2019; Gessert et al., 2006; Kuven & Giske, 2015; Pasman et al., 2003; Snyder et al., 2013; Volicer & Stets, 2016; Wilmot et al., 2002), however, two also addressed ANH (Snyder et al., 2013; Wilmot et al., 2002). |

TABLE 3.

Overview of included studies

| First author, year of publication and country | Aims | Methods | Sample size, population and location | Key findings and conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aita et al. (2007) Japan | To identify and analyse factors related to the decision to provide ANH a through PEG b in older Japanese adults with severe cognitive impairment. | Retrospective, in‐depth interviews. | 30 doctors and nurses in the Tokyo metropolitan area. |

|

| Austbo Holteng et al. (2017) Norway | To investigate the experiences of care staff when providing nutritional care for people with dysphagia and dementia using texture modified food (TMF c ). | Semi‐structured focus groups. | 12 professional ‘carers’ in a care home. |

|

| Berkman et al. (2019) USA | To describe the circumstances under which SLPs d (Speech and Language Pathologists) recommend oral nutritional intake for these patients. | One open‐ended question within a survey. | 509 SLPs working in general medical hospital, nursing home, or home‐health agency responded to the open‐ended question in the survey. |

Speech and Language Pathologists recommend oral nutritional intake even when people living with dementia are at high risk of aspiration when:

|

| Bryon et al. (2010) Belgium | To explore and describe how nurses are involved in the care that surrounds decisions concerning ANH in hospitalized patients with dementia. | Semi‐structured interviews. | 21 hospital nurses in Flanders. |

|

| Bryon et al. (2012a) Belgium | To explore and describe how Flemish nurses experience their involvement in the care of hospitalized patients with dementia, particularly in relation to ANH. | Same as Bryon et al. 2010 Belgium (Bryon et al., 2010) | Same as Bryon et al. 2010 Belgium (Bryon et al., 2010) |

|

| Bryon et al. (2012) Belgium | To explore nurses’ experiences of nurse–physician communication during ANH decision‐making in hospitalised patients with dementia. |

Same as Bryon et al. 2010 Belgium (Bryon et al., 2010) |

Same as Bryon et al. 2010 Belgium (Bryon et al., 2010) |

|

| Buiting et al. (2011) Australia and The Netherlands | To investigate how Dutch and Australian doctors decide about the use of ANH in patients with advanced dementia, and under what circumstances its use is considered appropriate or inappropriate. | Interviews with open‐ended questions. | 31 hospital and community doctors. |

|

| Gessert et al. (2006) USA | To describe and understand rural‐urban differences in attitudes toward death and in end‐of‐life decision making. | Focus groups. | 38 family members of people with severe cognitive impairment in a residential or nursing home. |

|

| Gil et al. (2018) Israel | To probe the considerations underlying the decision for gastrostomy, despite the data and the recommendations. | Participant observation at the clinic and in‐depth interviews with guardians. | 17 guardians of patients with advanced dementia most of whom were nursing home residents. |

|

| Kuven and Giske (2015) Norway | To explore the ethical dilemmas faced by nurses in hospitals when taking care of malnourished people living with dementia. | Focus groups. | 15 hospital nurses. |

|

| Lopez, Amella, Mitchell, et al. (2010) USA | To understand nursing beliefs, knowledge and roles in (ANH) feeding decisions for nursing home residents with advanced dementia. | Semi‐structured interviews. | 11 nurses working in 2 nursing homes. |

|

| Lopez, Amella, Strumpf, et al. (2010) USA | To better understand how nursing home characteristics influence the practice of tube feeding in patients with advanced cognitive impairment. | Observation (80 hr) and semi‐structured interviews. | 30 practitioners in 2 nursing homes (including social workers, nurses, speech and language pathologists, and diet technicians). |

|

| Lopez and Amella (2011) USA | To explore the perspective of community and nursing home family caregivers’ experience of assisting a family member with advanced dementia. | In‐depth interviews. | 16 family carers of people living with advanced dementia at home or living in a nursing home. |

|

| Pasman et al. (2003) The Netherlands | To describe the nature of problems nurses face when feeding nursing home patients with severe dementia, and how they manage these problems. | Participant observation (and interviews). | Observed: 106 participants; 60 patients with feeding problems [and severe dementia] and 46 nurses in 2 nursing homes. Unclear how many people were interviewed. |

|

| Pasman et al. (2004) The Netherlands | To determine the role and influence of different participants in the decision‐making process of starting or withholding ANH in people living with dementia in nursing homes. | Participant observation (and interviews) |

Observed 83; 8 nursing home physicians, 32 families, and 43 nurses. Unclear how many people were interviewed. |

|

| The et al. (2002) The Netherlands | To clarify the practice of withholding the artificial administration of fluids and food from elderly patients with dementia in nursing homes. | Participant observation (and interviews). |

Observed: 118; 35 patients on 10 wards, and 8 nursing home physicians, 32 families, and 43 nurses. Unclear how many people were interviewed. |

|

| Smith et al. (2016) USA | To explore perceptions of home healthcare nurses related to suffering, artificial nutrition and hydration in people with late‐stage dementia. | Focus groups. | 17 home‐health nurses working in a home‐care setting. |

|

| Snyder et al. (2013) USA | To describe surrogates’ baseline perceptions of the advantages and disadvantages of feeding options in dementia; and assess the impact of using a decision aid. | Interviews. | 126 surrogate decision makers for nursing home residents with advanced dementia. |

|

| Volicer and Stets (2016) USA | To explore the acceptability of an advance directive that includes discontinuation of feeding at certain stage of dementia for relatives of persons who died with dementia. | Focus groups. | 15 relatives of patients with dementia who died between 6 and 12 months ago in a hospice |

|

| Wilmot et al. (2002) UK | To explore how nursing and health care assistant staff apply ethical principles in feeding the person living with dementia, how they manage conflicts between those principles, and what they think influences their views on these issues. | Focus groups. | 12 nursing and health care assistant staff in a psychiatric hospital. |

|

Artificial Nutrition and Hydration.

Percutaneous Endoscopic Gastrostomy.

Texture Modified Food.

Speech and Language Pathologists.

3.2. Quality assessment

The quality of the 20 included papers varied (see Table 4 for various quality criteria). All papers provided an explanation of their aims and justified their use of qualitative methods, reflected on the ethical issues taken into consideration in their study and explicitly reported their findings.

The recruitment process was less frequently reported in detail as the way data were collected (e.g., using topic guides) and the description of data saturation. Rarely was the relationship between the researcher and the participant reported and description of the data analysis process was often brief.

3.3. Themes

We developed four main themes from the papers: (a) Challenges of supporting nutrition and hydration; (b) Balancing the views of all parties involved with “the right thing to do”; (c) National context and socio‐cultural influences; and (d) Strategies to support nutrition and hydration.

3.3.1. Challenges of supporting nutrition and hydration

Challenges around nutrition and hydration near the end of life were commonly discussed, including:

Communication difficulties

Verbal communication was often diminished in the later stages of dementia and practitioners relied on non‐verbal communication from the person living with dementia, such as facial expressions (Bryon et al., 2010, 2012a; Buiting et al., 2011; Pasman et al., 2003, 2004; Smith et al., 2016; The et al., 2002; Wilmot et al., 2002). However, staff differed in how they interpreted these expressions and hence led to different responses for the same expression by different staff (Pasman et al., 2003).

Lack of preparation and validity of advance care plans (ACP)

Papers often used the terms ACP, advance directives and living wills interchangeably (Berkman et al., 2019; Buiting et al., 2011). Many observed that planning was not completed routinely (Bryon et al., 2012a; Buiting et al., 2011; Lopez et al., 2010; Pasman et al., 2004) and existing plans, often did not mention nutrition and hydration (Volicer & Stets, 2016). A lack of discussion and reporting of wishes regarding eating and drinking sometimes led to families thinking ANH could be used to avoid ‘killing’ the individual (Aita et al., 2007; Gil et al., 2018). However, many felt decisions should be dependent on the current situation, context and individuals’ latest wishes, which meant care plans would always be outdated and irrelevant (Bryon et al., 2012a; Buiting et al., 2011; Pasman et al., 2004; The et al., 2002; Volicer & Stets, 2016).

Strain on carers and practitioners

Helping someone to eat and remain hydrated while balancing risks of choking and aspiration requires skill, giving rise to not just practical challenges for family carers and practitioners but also emotional challenges. Helping someone with dementia to eat was a time‐consuming process which meant families were not able to focus on other aspects of care (Lopez & Amella, 2011). Staff had to prioritize tasks around mealtimes and it significantly reduced their ability to care for other patients in settings where there were often already staff shortages (Austbo Holteng et al., 2017; Kuven & Giske, 2015). Practitioners experienced guilt when they felt they had not met their duty to support adequate nutrition (Austbo Holteng et al., 2017; Kuven & Giske, 2015) and for many family carers the heightened level of need highlighted the progression of the dementia and that their relative may be near the end of their life (Bryon et al., 2010; Lopez & Amella, 2011; Pasman et al., 2004).

Information and understanding

Throughout studies there was limited understanding of the natural progression of dementia (The et al., 2002) and the dying process (Gessert et al., 2006; Kuven & Giske, 2015; Lopez, Amella, Strumpf, et al., 2010; Volicer & Stets, 2016). Practitioners saw understanding of these principles as crucial to support families (Smith et al., 2016; The et al., 2002). However, nurses in the USA in particular appeared to lack confidence supporting families (Lopez et al., 2010; Pasman et al., 2004; Smith et al., 2016).

This broad lack of understanding about death and dying, coupled with lack of knowledge about the evidence base of using ANH among family carers (Gil et al., 2018; Pasman et al., 2004; Snyder et al., 2013) and practitioners meant some still favoured using ANH. Some practitioners and families perceived benefits of ANH, including the ability to extend life, maintain weight and avoiding starvation (Aita et al., 2007; Gessert et al., 2006; Gil et al., 2018; Pasman et al., 2004; Snyder et al., 2013). Some also felt ANH provided hope and comfort to the person living with dementia (Smith et al., 2016; Snyder et al., 2013). However, with greater knowledge of the evidence and understanding of their role, practitioners were strongly opposed to the use of ANH (Bryon et al., 2010). Likewise, increased knowledge among family carers reduced the use of ANH (Aita et al., 2007; Berkman et al., 2019; Buiting et al., 2011; Kuven & Giske, 2015; Smith et al., 2016; Snyder et al., 2013). However, some families resisted withholding ANH when they felt that it was their duty to protect the person living with dementia's right to life, or if they perceived comfort feeding or palliative care to be synonymous with euthanasia (Gessert et al., 2006; Gil et al., 2018).

3.3.2. Balancing the views of all parties involved with ‘the right thing to do’

The decision‐making process was complex, practitioners were not only constantly managing fluctuations in the health of the individual (The et al., 2002), but they also had to consider the wishes and beliefs of the individual, their quality of life (Berkman et al., 2019), the views of families and also their own views (Bryon et al., 2012a; Bryon et al., 2010; Buiting et al., 2011; Gil et al., 2018; Lopez, Amella, Mitchell, et al., 2010; Pasman et al., 2003, 2004; Smith et al., 2016). This created the difficulty of balancing the views of all parties involved with ‘the right thing to do’ clinically, reflected in the sub‐themes below.

Disagreement and conflict

Some papers discussed disagreements between friends and family, which increased as the numbers of people involved rose (Lopez & Amella, 2011; Pasman et al., 2004). The complexity of the decision, together with lack of knowledge around end of life and/or different views among third parties (e.g., extended family), created further emotional distress for some family carers (Lopez & Amella, 2011; Pasman et al., 2004).

Internal conflict was discussed by nurses or healthcare practitioners who reported having their own views about what was right for the individual which sometimes conflicted with their idea of what was right for the family (Bryon et al., 2010; Gessert et al., 2006; Kuven & Giske, 2015; Lopez & Amella, 2011; Pasman et al., 2004). This conflict occasionally manifested into disagreement with colleagues (Bryon et al., 2010, 2012a, 2012b; Pasman et al., 2004; The et al., 2002). Despite disagreements, it was accepted that doctors were responsible for making the ultimate decision on the type of treatment to be used near the end of life, but a shared decision was best practice (Bryon et al., 2010; Lopez, Amella, Strumpf, et al., 2010; Pasman et al., 2004; The et al., 2002).

Ethical concerns and considerations

Ethical dilemmas for practitioners and family were common mainly concerning problems of decision‐making, capacity, and communication (Lopez & Amella, 2011; Pasman et al., 2003, 2004; Snyder et al., 2013; Wilmot et al., 2002).

Staff in hospitals and nursing homes reflected on the dilemmas they faced when applying the principles of minimizing or doing no harm, autonomy, and preservation of life. They discussed the challenges of following these principles when they were superimposed, or when the person living with dementia was unable to verbally communicate (Kuven & Giske, 2015; Wilmot et al., 2002). Those in a nursing home reported finding themselves balancing what they were expected to do with what they thought was right. This included respecting the views of the individual and stopping assisting them with eating versus using lure and tricks to sustain eating (Kuven & Giske, 2015).

Ethical issues were particularly prevalent in the literature discussing ANH. Some practitioners reflected on the difference between withholding (or ‘avoiding inappropriate care’) and withdrawing ANH (Buiting et al., 2011). Family members also experienced ethical conflicts when having to decide on stopping ANH (Lopez & Amella, 2011; Snyder et al., 2013). At one end of the spectrum family carers and practitioners discussed the idea of not using ANH (a lack of intervention) as feeling like they would be taking someone's life. ANH was considered as a ‘basic’ element of care (Aita et al., 2007; Pasman et al., 2004) and not the same as life support used to keep people alive. Not providing ANH was ‘killing’ the person with dementia and ‘giving up’ (Aita et al., 2007; Gessert et al., 2006; Gil et al., 2018; Lopez & Amella, 2011). Some practitioners who felt ANH was futile, still could not ‘do nothing’ (Aita et al., 2007; Gil et al., 2018).

Prognosis

The approach to nutrition and hydration appeared to be influenced by prognosis. For example, the use of ANH together with antibiotics for acute episodes was justified if it was expected that this would cure the infection and increase quality of life (Buiting et al., 2011; The et al., 2002).

Unexpected fluctuations in the patient's condition made decisions difficult and sometimes altered previous agreements (Pasman et al., 2004; The et al., 2002; Wilmot et al., 2002). Doctors stated they mainly focused on their assessment of the current well‐being (including prognosis) and patient's quality of life (Buiting et al., 2011; Pasman et al., 2004; The et al., 2002).

3.3.3. National context and sociocultural influences

National and sociocultural factors influenced supporting eating and drinking, particularly the use of ANH; however, they did not explicitly lead to withholding ANH (Aita et al., 2007; Gessert et al., 2006; Gil et al., 2018; Lopez, Amella, Strumpf, et al., 2010; Pasman et al., 2004). At a national level financial factors were seen to be influential on implementation of ANH in some countries; for example; lack of staff and resources in Israel (Gil et al., 2018), generous reimbursement for use of PEG in Japan (Aita et al., 2007) and healthcare regulations around weight monitoring in US care homes penalising weight loss (Lopez, Amella, Strumpf, et al., 2010)). Fear of legal action by some led to the use of ANH, particularly in countries like Japan where there was a lack of clear legislation and guidance (Aita et al., 2007).

Cultural values were also relevant. For example, in Japan, greater emphasis was placed on the wishes and happiness of families than the individual patient (Aita et al., 2007). Sub‐groups and populations within countries, for example African Americans and urban residents, appeared to be favourable to the use of ANH (Gessert et al., 2006; Lopez, Amella, Strumpf, et al., 2010). Finally, religious beliefs (or religious interpretations) were also identified as a factor influencing support; however its influence was mixed across studies (Gil et al., 2018; Pasman et al., 2004; Snyder et al., 2013).

3.3.4. Strategies to support nutrition and hydration near the end of life in dementia

Only a few papers reported on strategies to support nutrition and hydration in people nearing the end of life including:

Getting to know the person and their preferences

Needs and preferences of the individual may change continuously (Austbo Holteng et al., 2017), studies suggested offering food at various times and exploring individual's needs through involving families to learn about their food preferences (Bryon et al., 2010). These approaches were important to family carers who reported the importance of the enjoyment of food and drink (Snyder et al., 2013).

Enriching food

Practitioners and family carers reported altering food to ensure high caloric intake through enriching food with cream for example or offering more caloric food, such as two desserts (Kuven & Giske, 2015; Lopez & Amella, 2011; Pasman et al., 2003).

Texture modified diet

Adapting food according to the individual's needs, such as modifying food consistency by blending or choosing softer food and using ‘baby’ food (Volicer & Stets, 2016). Texture modified food increased care staff confidence by reducing the risk of choking, better meeting the needs of people living with dementia and enhanced the individual's independence by enabling them to feed themselves (Austbo Holteng et al., 2017).

Assisted techniques to encourage eating

Family carers felt preserving the individual's dignity was one of the advantages of eating by mouth as opposed to tube feeding (Snyder et al., 2013). Practitioners reported this could be done via several techniques including: stimulating the swallowing reflex by gently touching the individual's lips with a napkin and gently pushing them to eat softly (Pasman et al., 2003); maintaining visual contact, providing physical support, and using verbal encouragement (Lopez, Amella, Strumpf, et al., 2010). These techniques enabled the human connection and preserved dignity. Speech and language pathologists highlighted the need for the individual to be alert and carers had to be able to provide adequate oral hygiene and use strategies to reduce aspiration risk (Berkman et al., 2019). However, family carers raised concerns these techniques encouraged the loss of independent eating, the risk of choking and overfeeding (Snyder et al., 2013). Occasionally, practitioners also reported situations where they pushed the person living with dementia forcefully or held their hands in a restrictive way (Pasman et al., 2003).

Environmental and contextual modifications

Modification of the environment and the use of routines, reminiscence (e.g. recreating family celebrations) and involvement of familiar faces played an important role in facilitating nutrition and hydration as reported by practitioners and family carers (Kuven & Giske, 2015; Lopez & Amella, 2011). Environmental modifications creating a more home‐like environment in care homes or encouraging a quieter environment, were considered to lead to a better quality of care overall, focused on the pleasure and enjoyment of nutrition and hydration and to fewer residents receiving ANH (Lopez, Amella, Strumpf, et al., 2010; Pasman et al., 2003). Other approaches to nutrition and hydration were also discussed, ranging from small steps of adapting cutlery, cups, and plates that may also enhance the individual's autonomy around eating, through to more substantial changes of increasing time allocation for mealtimes (Bryon et al., 2010; Lopez, Amella, Strumpf, et al., 2010).

4. DISCUSSION

Four main themes were identified: challenges of supporting nutrition and hydration; balancing the views of all parties involved with ‘the right thing to do’; the national context and sociocultural influences; strategies to support nutrition and hydration near the end of life in dementia. Most studies focused on practitioners’ views, rather than family carers’. No studies reported the views of people living with mild dementia, reinforcing that little is known about people living with dementia's wishes in respect of nutrition and hydration.

Studies focused on the use of ANH and the process of decision‐making, including contextual factors influencing these processes. Few focused on alternative strategies to ANH to support and manage nutrition and hydration. This might be related to studies’ focus on practitioners’ perspectives in long‐term care or medicalized settings rather than those of family carers. Notably, most of the family members in the included studies were supporting their relative with dementia in care home or nursing homes settings, with few studies including carers supporting someone living at home (Gil et al., 2018; Lopez & Amella, 2011).

Whilst every possible scenario cannot be planned, advance care planning (ACP) is often seen as ‘the solution’ to ensure a good death. However, this review highlights that some practitioners may question the ‘validity’ of ACP. This helps to understand previous findings that under 40% of physicians surveyed in The Netherlands agreed that an advance directive should always be followed (Rurup et al., 2006). This leads to questions of why undertake ACP, if it is seen as immediately outdated. If policy is to continue to encourage the use of ACP, more work is needed on the use of discretion in interpreting the validity and utility of ACP. Importantly, if the use of ACP is questioned and discussion is needed, it is important to include the views of people living with dementia in end of life research so we have a better understanding of what the priorities at the end of life are from their perspective to inform practice. This review has revealed a lack of research with people living with dementia focusing on nutrition and hydration and this mirrors the wider field of end of life care research more generally. This will ensure their views and experiences around important topics such as nutrition and hydration near the end of life are better respected.

Latest evidence continues to report the lack of effectiveness of ANH interventions near the end of life of people living with dementia (De & Thomas, 2019; Sampson et al., 2009). However, this review suggests that practitioners in some countries (e.g., US, Japan, Israel) have not necessarily been applying the latest evidence to their clinical practice. A multitude of factors appear to affect decision‐making going beyond the individuals involved and including both national and sociocultural factors, such as; staff and financial imperatives, weight control policies and lack of clear legislation. These findings are aligned with those of a previous systematic review on the decision‐making process around the use of ANH among people lacking capacity, where the basis for its use was the belief that ANH could prolong life (Clarke et al., 2013) despite not corresponding with current evidence (Davies et al., 2019; Sampson et al., 2009). In contrast, living in rural areas and some religious interpretations led to the withholding of ANH near the end of life of the person living with dementia. The role of religious beliefs seems unclear, however, as two papers identified religious beliefs would lead to the use of ANH while another paper reported the opposite. This could point towards religious interpretations (in different groups or locations) and more broadly culture not just religious beliefs having an impact on decision‐making (Chakraborty et al., 2017).

Strategies to support nutrition and hydration near the end of life were identified and included, however, findings suggest that strategies to support nutrition near the end of life in the context of dementia are rarely explored in depth. Hence, there is a need for studies exploring how carers and practitioners manage such difficulties, what support they need and how people living with dementia would like to be looked after at life's end.

4.1. Strengths and weaknesses

This review used a systematic and rigorous approach to our search strategies and screening by multiple reviewers. The review was conducted by a large multi‐disciplinary team consisting of backgrounds in psychology, speech and language therapy, social work, psychiatry, and general practice. This enabled a variety of perspectives to understand and interpret the findings and address the implications for practice and research.

This review only included qualitative studies, which may mean we have omitted an important part of the story from quantitative studies; however, we are aware of other ongoing reviews investigating quantitative literature. A strength of this review is the wide time frame searched (20 years). Including studies published in the past 20 years allowed us to reflect on both the growing interest in end of life research but also the limited inclusion of people living with dementia's views and the slow translation of research into practice (e.g., regarding the use of ANH).

We only included studies where it was clearly mentioned that carers and practitioners were caring for the person living with dementia nearing the end of life, at an advanced or later stage of dementia. Thus, some qualitative papers were excluded as they did not refer to the stage of dementia. This highlights the importance for qualitative researchers to clearly report participant characteristics.

Finally, when making international comparisons we should be mindful of the variety of terms used to discuss staff. In some studies, it appeared that the term nurses might be being applied to both certificated and non‐certificated staff and was not necessarily being applied to registered nurses. This may have implications for the interview data and observations and the nurses' communications with medical personnel.

4.2. Implications for research and practice

The use of ACP to inform decision‐making differs between countries (Harrison Dening et al., 2019). In our review, some studies noted that some practitioners raised issues regarding the validity of ACP, since these cannot account for every contingency. Existing research is focused on developing resources to support ACP and exploring how we conduct ACP and engage in discussions. However, reluctance to complete ACP and issues around validity are important and should be explored further. In particular, there is a lack of research to explore directly the views of people living with dementia regarding their preferences near the end of life and approach towards advance care planning.

Even when ANH decisions take place in national or sociocultural contexts where ANH use is considered as the default option, learning about ANH and guidance might help reduce its use without unwarranted consequences for physicians and others involved.

Finally, our understanding of challenges is well‐developed but ways of supporting nutrition and hydration near the end of life, particularly at home, remain largely unexplored. This is an important gap. The difficulties and the successful approaches undertaken by carers and practitioners of people living with dementia at home are important to understand as we see an increasing shift of emphasis of formal care services providing care, to family carers providing care at home. Increasing this understanding would enable us to understand what further support family carers need at home and how.

5. CONCLUSION

This review points towards the complexity of supporting nutrition and hydration for the person living with dementia near end of life. Lack of awareness of evidence, limited prior discussions and care planning with the person living with dementia and the national and sociocultural context, all further increased this challenge. Exploration of how families are successfully supporting nutrition and hydration at home near the end of life is needed, focusing on situations when ANH is not used. Furthermore, the inclusion of diverse groups of people living with dementia is needed in qualitative work to understand their views and lived experience about nutrition and hydration near the end of their lives.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No conflict of interest has been declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors have agreed on the final version and meet at least one of the following criteria (recommended by the ICMJE*):

substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data;

drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content.

Dr Yolanda Barrado‐Martín: Conception and design, acquisition of data (identification, screening of papers and data extraction), analysis and interpretation of the data, drafting the manuscript, final approval of the version to be published, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Dr Lee Hatter: Acquisition of data (identification, screening of papers and data extraction), analysis and interpretation of the data, revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be published, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Dr Kirsten J. Moore: Analysis and interpretation of the data, revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be published, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Prof Elizabeth L. Sampson: Analysis and interpretation of the data, revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be published, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Prof Greta Rait: Analysis and interpretation of the data, revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be published, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Prof Jill Manthorpe: Analysis and interpretation of the data, revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be published, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Dr Christina H. Smith: Analysis and interpretation of the data, revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be published, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Dr Pushpa Nair: Analysis and interpretation of the data, revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be published, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Dr Nathan Davies: Conception and design, acquisition of data (screening of papers), analysis and interpretation of the data, drafting the manuscript, final approval of the version to be published, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Supporting information

Supinfo

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Dr Johan Thygesen for his support in the translation of articles and our lay advisors in the Nutri‐Dem study.

Barrado‐Martín Y, Hatter L, Moore KJ, et al. Nutrition and hydration for people living with dementia near the end of life: A qualitative systematic review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2021;77:664–680. 10.1111/jan.14654

Funding information

This work was supported by Marie Curie [grant number MCRGS‐20171219‐8004].

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

REFERENCES

- Aita, K. , Takahashi, M. , Miyata, H. , Kai, I. , & Finucane, T. E. (2007). Physicians' attitudes about artificial feeding in older patients with severe cognitive impairment in Japan: A qualitative study. BMC Geriatrics, 7, 22 10.1186/1471-2318-7-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alagiakrishnan, K. , Bhanji, R. A. , & Kurian, M. (2013). Evaluation and management of oropharyngeal dysphagia in different types of dementia: A systematic review. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 56(1), 1–9. 10.1016/j.archger.2012.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arcand, M. (2015). End‐of‐life issues in advanced dementia Part 2: Management of poor nutritional intake, dehydration and pneumonia. Canadian Family Physician, 61(4), 337–341. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austbo Holteng, L. B. , Froiland, C. T. , Corbett, A. , & Testad, I. (2017). Care staff perspective on use of texture modified food in care home residents with dysphagia and dementia. Annals of Palliative Medicine, 6(4), 310–318. 10.21037/apm.2017.06.24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baijens, L. W. J. , Clave, P. , Cras, P. , Ekberg, O. , Forster, A. , Kolb, G. F. , & Walshe, M. (2016). European society for swallowing disorders ‐ European union geriatric medicine society white paper: Oropharyngeal dysphagia as a geriatric syndrome. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 11, 1403–1428. 10.2147/CIA.S107750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball, L. , Jansen, S. , Desbrow, B. , Morgan, K. , Moyle, W. , & Hughes, R. (2015). Experiences and nutrition support strategies in dementia care: Lessons from family carers. Nutrition & Dietetics, 72(1), 22–29. 10.1186/s12904-018-0314-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman, C. , Ahronheim, J. C. , & Vitale, C. A. (2019). Speech‐language pathologists' views about aspiration risk and comfort feeding in advanced dementia. American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Medicine, 36(11), 993–998. 10.1177/1049909119849003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryon, E. , De Casterle, B. D. , & Gastmans, C. (2012a). 'Because we see them naked'‐Nurses' experiences in caring for hospitalized patients with dementia: Considering artificial nutrition or hydration (ANH). Bioethics, 26(6), 285–295. 10.1111/j.1467-8519.2010.01875.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryon, E. , De Casterle, B. D. , & Gastmans, C. (2012b). Nurse‐physician communication concerning artificial nutrition or hydration (ANH) in patients with dementia: A qualitative study. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 21(19–20), 2975–2984. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.04029.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryon, E. , Gastmans, C. , & de Casterle, B. D. (2010). Involvement of hospital nurses in care decisions related to administration of artificial nutrition or hydration (ANH) in patients with dementia: A qualitative study. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 47(9), 1105–1116. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2010.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buiting, H. M. , Clayton, J. M. , Butow, P. N. , van Delden, J. J. M. , & van der Heide, A. (2011). Artificial nutrition and hydration for patients with advanced dementia: Perspectives from medical practitioners in the Netherlands and Australia. Palliative Medicine, 25(1), 83–91. 10.1177/0269216310382589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (2009). Systematic reviews: CRD's guidance for undertaking reviews in health care. University of York: Centre for Research and Dissemination. Retrieved from https://www.york.ac.uk/media/crd/Systematic_Reviews.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty, R. , El‐Jawahri, A. R. , Litzow, M. R. , Syrjala, K. L. , Parnes, A. D. , & Hashmi, S. K. (2017). A systematic review of religious beliefs about major end‐of‐life issues in the five major world religions. Palliative & Supportive Care, 15(5), 609–622. 10.1017/S1478951516001061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cipriani, G. , Carlesi, C. , Lucetti, C. , Danti, S. , & Nuti, A. (2016). Eating behaviors and dietary changes in patients with dementia. American Journal of Alzheimer's Disease & Other Dementias, 31(8), 706–716. 10.1177/1533317516673155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, G. , Harrison, K. , Holland, A. , Kuhn, I. , & Barclay, S. (2013). How are treatment decisions made about artificial nutrition for individuals at risk of lacking capacity? A systematic literature review. PLoS One, 8(4), e61475 10.1371/journal.pone.0061475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme . (2018). CASP qualitative checklist. Retrieved from https://casp‐uk.net/wp‐content/uploads/2018/03/CASP‐Qualitative‐Checklist‐2018_fillable_form.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Davies, N. , Barrado‐Martin, Y. , Rait, G. , Fukui, A. , Candy, B. , Smith, C. H. , Sampson, E. L. (2019). Enteral tube feeding for people with severe dementia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (12), CD013503 10.1002/14651858.CD013503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De, D. , & Thomas, C. (2019). Enhancing the decision‐making process when considering artificial nutrition in advanced dementia care. International Journal of Palliative Nursing, 25(5), 216–223. 10.12968/ijpn.2019.25.5.216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gessert, C. E. , Elliott, B. A. , & Peden‐McAlpine, C. (2006). Family decision‐making for nursing home residents with dementia: Rural‐urban differences. The Journal of Rural Health, 22(1), 1–8. 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2006.00013.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil, E. , Agmon, M. , Hirsch, A. , Ziv, M. , & Zisberg, A. (2018). Dilemmas for guardians of advanced dementia patients regarding tube feeding. Age & Ageing, 47(1), 138–143. 10.1093/ageing/afx161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guigoz, Y. , Jensen, G. , Thomas, D. , & Vellas, B. (2006). The Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA®) Review of the literature‐what does it tell us?/Discussion. The Journal of Nutrition, Health & Aging, 10(6), 466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison Dening, K. , Sampson, E. L. , & De Vries, K. (2019). Advance care planning in dementia: Recommendations for healthcare professionals. Palliative Care, 12, 117822421982657 10.1177/1178224219826579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harwood, R. H. (2014). Feeding decisions in advanced dementia. Journal of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh, 44(3), 232–237. 10.4997/JRCPE.2014.310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda, M. , Brown, J. , Holland, A. J. , Fukuhara, R. , & Hodges, J. R. (2002). Changes in appetite, food preference and eating habits in frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry, 73(4), 371 10.1136/jnnp.73.4.371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuven, B. M. , & Giske, T. (2015). Når mor ikke vil spise – Etiske dilemmaer i møte med underernærte mennesker med demens i sykehjem: When mother will not eat – Ethical dilemmas experienced by nurses when encountering malnourished patients. Nordic Journal of Nursing Research, 35(2), 98–104. 10.1177/0107408315578593 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez, R. P. , & Amella, E. J. (2011). Time travel: The lived experience of providing feeding assistance to a family member with dementia. Research in Gerontological Nursing, 4(2), 127–134. 10.3928/19404921-20100729-02 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez, R. P. , Amella, E. J. , Mitchell, S. L. , & Strumpf, N. E. (2010). Nurses' perspectives on feeding decisions for nursing home residents with advanced dementia. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 19(5–6), 632–638. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.03108.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez, R. P. , Amella, E. J. , Strumpf, N. E. , Teno, J. M. , & Mitchell, S. L. (2010). The influence of nursing home culture on the use of feeding tubes. Archives of Internal Medicine, 170(1), 83–88. 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D. , Liberati, A. , Tetzlaff, J. , Altman, D. G. ; The PRISMA Group . (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta‐analyses: The prisma statement. Annals of Internal Medicine, 151(4), 264–269. 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nell, D. , Neville, S. , Bellew, R. , O'Leary, C. , & Beck, K. L. (2016). Factors affecting optimal nutrition and hydration for people living in specialised dementia care units: A qualitative study of staff caregivers' perceptions. Australasian Journal on Ageing, 35(4), E1–E6. 10.1111/ajag.12307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuberger, J. (2013). More care, less pathway: A review of the liverpool care pathway. Retrieved from http://data.parliament.uk/DepositedPapers/Files/DEP2013‐1240/More_Care_Less_Pathway_A_Review_of_the_Liverpool_Care_Pathway.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Pasman, H. R. W. , Mei, B. A. , Onwuteaka‐Philipsen, B. D. , Ribbe, M. W. , & van der Wal, G. (2004). Participants in the decision making on artificial nutrition and hydration to demented nursing home patients: A qualitative study. Journal of Aging Studies, 18(3), 321–335. 10.1016/j.jaging.2004.03.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pasman, H. R. W. , The, B. A. M. , Onwuteaka‐Philipsen, B. D. , van der Wal, G. , & Ribbe, M. W. (2003). Feeding nursing home patients with severe dementia: A qualitative study. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 42(3), 304–311. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02620.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popay, J. , Roberts, H. , Sowden, A. , Petticrew, M. , Arai, L. , Rodgers, M. , Britten, N. , Roen, K. , & Duffy, S. (2006). Guidance on the Conduct of Narrative Synthesis in Systematic Reviews: A Product from the ESRC Methods Programme. Retrieved from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.178.3100&rep=rep1&type=pdf [Google Scholar]

- Rurup, M. L. , Onwuteaka‐Philipsen, B. D. , Pasman, H. R. W. , Ribbe, M. W. , & van der Wal, G. (2006). Attitudes of physicians, nurses and relatives towards end‐of‐life decisions concerning nursing home patients with dementia. Patient Education and Counseling, 61(3), 372–380. 10.1016/j.pec.2005.04.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson, E. L. , Candy, B. , Davis, S. , Gola, A. B. , Harrington, J. , King, M. , Kupeli, N. , Leavey, G. , Moore, K. , Nazareth, I. , Omar, R. Z. , Vickerstaff, V. , & Jones, L. (2017). Living and dying with advanced dementia: A prospective cohort study of symptoms, service use and care at the end of life. Palliative Medicine, 32(3), 668–681. 10.1177/0269216317726443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson, E. L. , Candy, B. , & Jones, L. (2009). Enteral tube feeding for older people with advanced dementia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2, CD007209 10.1002/14651858.CD007209.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandilyan, M. B. (2011). Abnormal eating patterns in Dementia: A cause for concern. Age and Ageing, 40, 10.1093/ageing/el_195 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, L. , Amella, E. J. , & Nemeth, L. (2016). Perceptions of home health nurses regarding suffering, artificial nutrition and hydration in LATE‐STAGE DEMENTIA. Home Healthcare now, 34(9), 478–484. 10.1097/NHH.0000000000000459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder, E. A. , Caprio, A. J. , Wessell, K. , Lin, F. C. , & Hanson, L. C. (2013). Impact of a decision aid on surrogate decision‐makers' perceptions of feeding options for patients with dementia. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 14(2), 114–118. 10.1016/j.jamda.2012.10.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The, A.‐M. , Pasman, R. , Onwuteaka‐Philipsen, B. , Ribbe, M. , & van der Wal, G. (2002). Withholding the artificial administration of fluids and food from elderly patients with dementia: Ethnographic study. BMJ, 325(7376), 1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volicer, L. , & Stets, K. (2016). Acceptability of an advance directive that limits food and liquids in advanced dementia. American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Medicine, 33(1), 55–63. 10.1177/1049909114554078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkert, D. , Chourdakis, M. , Faxen‐Irving, G. , Frühwald, T. , Landi, F. , Suominen, M. H. , & Schneider, S. M. (2015). ESPEN guidelines on nutrition in dementia. Clinical Nutrition, 34(6), 1052–1073. 10.1016/j.clnu.2015.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watt, A. D. , Jenkins, N. L. , McColl, G. , Collins, S. , & Desmond, P. M. (2019). Ethical issues in the treatment of late‐stage Alzheimer's disease. Journal of Alzheimers Disease, 68(4), 1311–1316. 10.3233/jad-180865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White, H. , Pieper, C. , Schmader, K. , & Fillenbaum, G. (1996). Weight change in Alzheimer's disease. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 44(3), 265–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilmot, S. , Legg, L. , & Barratt, J. (2002). Ethical issues in the feeding of patients suffering from dementia: A focus group study of hospital staff responses to conflicting principles. Nursing Ethics, 9(6), 599–611. 10.1191/0969733002ne554oa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . (2017). Global action plan on the public health response to dementia ‐ 2017–2025. Retrieved from https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/259615/9789241513487‐eng.pdf;jsessionid=429D8C18CF5C0D45C8EE175743B00A4E?sequence=1 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supinfo

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.