ABSTRACT

Objective.

To identify barriers to the implementation of National Childbirth Guidelines in Brazil from the women’s perspective.

Methods.

A descriptive exploratory study was performed using a qualitative approach and an interpretive perspective. The hermeneutic unit of analysis was established based on the contribution of users to a public online consultation about the National Childbirth Guidelines in Brazil, performed in 2016 by the National Committee for Health Technology Incorporation into the Unified Health System (CONITEC). Content analysis techniques were used to examine the answers provided to the following specific question: “Considering your local reality, what would hinder the implementation of this protocol or guideline?”

Results.

Of 396 contributions recorded by CONITEC, 55 were included in the content analysis. The mean age of women was 31 years, with most self-declared as white (69%) and living in the Southeast of Brazil (56.3%). Coding revealed seven barrier categories, which were grouped into three families — barriers related to 1) professional training and culture (which highlighted the centrality of physicians, not women, in childbirth), 2) social culture (general population not well informed), and 3) political and management issues (little interest on the part of managers, lower physician compensation for vaginal childbirth vs. cesarian section, and poor hospital infrastructure).

Conclusions.

Aspects of professional training and culture, social culture, and political as well as management issues are critical points to be considered in future interventions aiming at overcoming or weakening the barriers to implementing childbirth recommendations in Brazil.

Keywords: Parturition, clinical protocols, implementation science, Brazil

RESUMEN

Objetivo.

Determinar los obstáculos existentes para la aplicación de las directrices de asistencia al parto normal en Brasil desde la perspectiva de las mujeres.

Métodos.

Se realizó un estudio descriptivo exploratorio, con un enfoque cualitativo y una perspectiva de investigación interpretativa. La unidad hermenéutica se construyó a partir de los aportes hechos por usuarias a una consulta pública en línea sobre las directrices nacionales de asistencia al parto normal realizada en el 2016 por la Comisión Nacional de Incorporación de Tecnologías (CONITEC) en el Sistema Único de Salud. Se utilizó la metodología de análisis del contenido para examinar específicamente las respuestas a la siguiente pregunta: considerando su realidad local, ¿qué dificultaría la implantación de este protocolo o de esta directriz?

Resultados.

En el análisis del contenido se incluyeron 55 de los 396 aportes recibidos por la CONITEC. Las mujeres tenían una media de edad de 31 años y, en su mayoría, eran blancas (69%) y residentes en la región Sudeste de Brasil (56,3%). La codificación reveló siete categorías de obstáculos, agrupados en tres clases, a saber, obstáculos relacionados con 1) la formación y la cultura profesional (con hincapié en la centralidad de los médicos y no de las mujeres en el parto), 2) la cultura social (la falta de información por parte de la población) y 3) las cuestiones de política y gestión (la falta de interés de los gestores, la menor remuneración de los médicos que atienden el parto normal en comparación con quienes practican cesáreas y la falta de infraestructura hospitalaria).

Conclusiones.

Los resultados mostraron que los aspectos relacionados con la formación y la cultura profesional, la cultura social y las cuestiones de política y gestión son puntos críticos que deben considerarse en la realización de intervenciones futuras con objeto de superar o reducir los obstáculos existentes para la aplicación de las recomendaciones de asistencia al parto normal en Brasil.

Palabras clave: Parto, protocolos clínicos, ciencia de la implementación, Brasil

RESUMO

Objetivo.

Identificar barreiras à implementação das diretrizes de assistência ao parto normal no Brasil sob a perspectiva das mulheres.

Métodos.

Realizou-se um estudo descritivo-exploratório, de abordagem qualitativa e perspectiva interpretativista. A unidade hermenêutica foi construída a partir das contribuições de usuárias a uma consulta pública on-line sobre as Diretrizes Nacionais de Assistência ao Parto Normal realizada em 2016 pela Comissão Nacional de Incorporação de Tecnologias no Sistema Único de Saúde (CONITEC). Foi utilizada a metodologia de análise de conteúdo para examinar especificamente as respostas à questão “Considerando sua realidade local, o que dificultaria a implantação deste protocolo ou diretriz?”.

Resultados.

Das 396 contribuições recebidas pela CONITEC, 55 foram incluídas na análise de conteúdo. A média de idade das mulheres foi de 31 anos, sendo a maioria branca (69%) e residente na região Sudeste do Brasil (56,3%). A codificação revelou sete categorias de barreiras, agrupadas em três famílias — barreiras relacionadas a 1) formação e cultura profissional (com destaque para a centralidade dos médicos, e não das mulheres, no parto), 2) cultura social (falta de informação por parte da população) e 3) questões políticas e de gestão (falta de interesse dos gestores, menor remuneração para médicos que atendem parto normal vs. cesariana e falta de infraestrutura hospitalar).

Conclusões.

Os resultados mostraram que aspectos da formação e cultura profissional, cultura social e questões políticas e de gestão são pontos críticos que devem ser considerados na realização de intervenções futuras com o objetivo de transpor ou enfraquecer as barreiras à implementação de recomendações ao parto normal no Brasil.

Palavras-chave: Parto, protocolos clínicos, ciência da implementação, Brasil

Brazil’s Unified Health System (SUS) is one of the largest and most complex universal public health systems in the world, guaranteeing comprehensive coverage from primary care through the highest level of complexity and offering benefits that range from immunization programs and to access to high-cost drugs and organ transplants (1). In addition to this program, slightly more than 46 million of the country’s 209.5 million inhabitants have coverage through private health insurance plans (2).

In recent decades, Brazil, as along with other Latin American countries, has seen an alarming spike of the rate of cesarean sections, which now account for the majority of births—55.9% in 2018 (3). In that same year, the average rate of C-sections reached 70% in some states and federal entities and 90% in some private health facilities (3, 4).

To address this problem, several initiatives have been taken with a view to improving the quality of childbirth and delivery care in both the public and supplementary health systems (5, 6). The most notable example has been the adoption of National Guidelines for Normal Childbirth Care in Brazil (7). These Guidelines, prepared by Brazil’s Ministry of Health in consultation with scientific groups and representatives of civil society, contain evidence-based recommendations on issues related to childbirth options. They were developed following systematic methods described in the literature for adapting existing clinical guidelines to local realities (8). The process was led by the National Committee for the Incorporation of Health Technology into the Unified Health System (CONITEC), the Ministry of Health’s legal entity responsible for providing advice on the preparation of clinical protocols and treatment guidelines (9).

Despite their methodological foundation, the Guidelines have weaknesses. Use of the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation II (AGREE II) (10), a methodological tool for assessing the methodological rigor of clinical guidelines, revealed limited applicability, based on analysis and identification of the potential factors affecting their implementation.

International experience has shown that, in addition to planning for the implementation of clinical guidelines, it is essential to incorporate the perspective of users from the outset and during all the stages of guideline development (11, 12) in order to ensure that their experiences and requests are duly reflected. Inclusion of the user perspective also plays an important role in disseminating knowledge about the subject (13, 14).

To include the perspective of society in its decision-making process, CONITEC sought social participation through public consultations and developed a form for compiling the users’ contributions (15). In this context, the objective of the present study was to identify potential barriers to implementation of the National Guidelines for Normal Childbirth Care in Brazil based on the women’s perspective, because it is women who are central to these recommendations and the ones who are directly affected.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was part of the project “Barriers and Strategies for Implementation of the Guidelines for Normal Childbirth in Brazil” [Call for Proposals on Embedding Research for the Sustainable Development Goals (ER-SDG)],” sponsored by the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) and other institutional partners. Two other related articles are included in this special supplement (16, 17).

A descriptive-exploratory study was conducted using a qualitative approach and an interpretivist perspective. The subject of the analysis was the comments on a preliminary version of the National Guidelines for Normal Childbirth Care in Brazil provided by women who participated in a public consultation held in January 2016 (7). The document was made available on the CONITEC public portal and the comments were gathered online between 12 January and 29 February 2016. After this period, all the contributions received were made available anonymously on the CONITEC portal (18). For the purposes of the present study, comments by health professionals and corporations or individuals with an interest in the subject were excluded. The only responses studied were those from female users who responded to the question: “Considering your own local reality, what would make it difficult to implement this protocol or guideline?” (18).

Once the data were entered in an electronic spreadsheet, the content of the contributions was analyzed. The analysis was conducted in three stages, based on the structure proposed by Bardin (19). First, the content was subjected to a pre-analysis in which the contributions were organized by type in order to create a hermeneutical unit and those received from women were identified. In the second stage (examination of the material), the data were read and encoded. The third stage focused on processing the data and interpreting the results in order to categorize their content according to shared characteristics. This categorization was not based on any predetermined assumptions; in other words, the categories emerged from interpretation of the meanings derived from the codes that were assigned. Next, the categories were organized into groups, called “families,” based on the perceived relationships between them. Content analysis was conducted using Atlas.ti 7.0 software.

The following criteria were adopted for assessing the methodological rigor (“trustworthiness”) of qualitative research: credibility, dependability, confirmability, and transferability of the findings (20). The criteria of credibility and dependability were assumed to be met because the data used in this study were drawn from a public repository (http://dx.doi.org/10.17632/znjsyz3kzy.1). To ensure validity, the data analysis was performed by one researcher (ATV) and then re-done by a second researcher (DR). The criterion of confirmability was tested using the Atlas.ti software. The record of all the methodological steps taken during the research is available in a public data repository, where it is possible to access the report with the codes corresponding to the comments cited and the classification of the families identified in the hermeneutical unit http://dx.doi.org/10.17632/znjsyz3kzy.1). With regard to transferability, is should be noted that the women’s contributions may suffer from contextual effects; in other words, the fact that they were obtained through an anonymous online public consultation over a period of time may affect their content.

A process of self-reflection is called for at this point to consider the possible influence of the researchers’ values on the interpretation of the data. Even though there was never any interaction between the research group and the women who made the comments, it must be recognized that the perspective from which the subject of study is observed can affect interpretation of the data. For this reason, it is important to declare that the researcher responsible for analysis of the data had participated in the discussion of the recommendations in the Guidelines and that one of the researchers works on the defense of women in matters related to their health and the humanization of childbirth. While their experience and knowledge of the topics being addressed have been helpful in identifying and recognizing the categories, this background may also slant the perspective of the analysis.

As provided in National Health Council (CNS) Resolution 510/2016, since the content being analyzed was publicly available information and no individuals were identified (18), there was no need to obtain approval from the Research Ethics Committee.

RESULTS

A total of 396 contributions were received through the CONITEC portal: 66 from users/patients; 24 from a patient’s family members, friends, or caregivers; 233 from health professionals; 63 from individuals interested in the subject; and 10 from corporations. Of the 90 contributions submitted on the form for users/patients, friends, or caregivers, 82 were from women. Of these, 55 answered the question “Considering your own local reality, what would make it difficult to implement this protocol or guideline?” Their responses were submitted for content analysis.

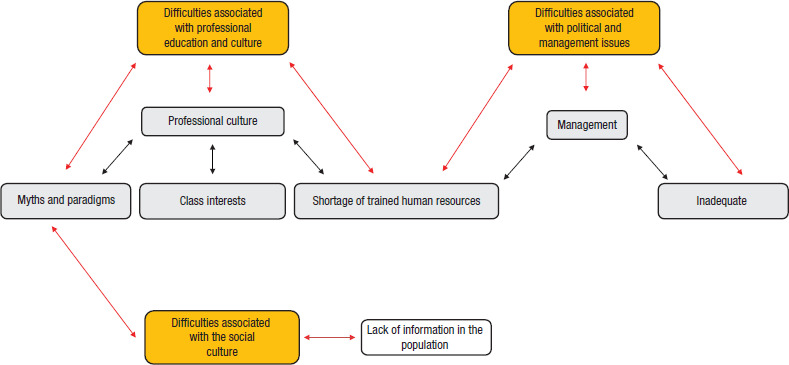

The women’s average age was 31; most of them (69%) were White; and the majority (56.3%) lived in the Southeastern region of Brazil. Analysis of the content of their contributions regarding difficulties encountered in implementation of the Guidelines for Normal Childbirth resulted in the identification of seven recurring categories: 1) professional culture; 2) shortage of trained human resources; 3) management issues; 4) inadequate structure; 5) lack of information on the population; 6) class interests; and 7) myths and paradigms.

These categories were grouped into three families: 1) difficulties associated with professional education and culture; 2) difficulties associated with the social culture; and 3) difficulties associated with political and management issues. Interrelationships were observed between these families, since the categories share links to both shortage of trained human resources and myths and paradigms, as shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1. Network of relationships between families of difficulties cited by women participating in a public consultation on implementation of the recommendations on normal childbirth in Brazila.

Difficulties associated with professional education and culture

With regard to professional culture, the women’s comments mentioned the resistance of health professionals to accept changes; physician-centered, rather than women-centered, childbirth; and lack of autonomy of other nonmedical professionals. These concerns were reflected in the following statements:

Resistance of professionals to change their reality: As long as the professionals insist that it is not feasible to humanize childbirth, whether because of inconvenience or lack of patience to wait for the normal progress of labor, implementation of the protocol and Guidelines will continue to be delayed (CONITEC, Public Consultation, Jan 2016, p. 126) (18).

Health professionals in this area (obstetricians, nurse technicians, nurses, and pediatricians) insist on turning childbirth into a medical event […]. They do not allow the woman to be the protagonist—for example: to walk, to eat, or choose the most comfortable position to give birth (CONITEC, Public Consultation, Jan 2016, p. 15) (18).

Two other points are emphasized in this category: humanization, and obstetric violence. Both were addressed, with emphasis on the absence of humanized treatment and violent interventions that disregard women’s rights:

Much obstetric violence is still occurring in the current obstetric context, which outrages us; we know, based on the small amount of information that is shared with us as laypeople, that childbirth care doesn’t need to be this way (CONITEC, Public Consultation, Jan 2016, p. 111) (18).

Three additional categories related to the professional culture were shortage of trained human resources, class interests, and myths and paradigms. The women said that the network does not have enough health professionals trained to provide integrated, humanized care that incorporates practices based on scientific evidence rather than outdated myths and care paradigms. The problem is reinforced by class interests, which, according to the women, perpetuate the same practices and attitudes regarding childbirth and delivery and the continued defense of the same practices and models of childbirth care.

[…] one major hindrance will be the medical corporations, which are intent on maintaining control over women’s bodies and the procedures they have been using for decades, with emphasis on C-section and episiotomy, while failing to provide women with explanatory information when they are receiving childbirth care (CONITEC, Public Consultation, Jan 2016, p. 227) (18).

An issue worth reflecting on here is the normalization of granting women’s “requests” for C-sections, rather than exploring their real wishes and considering the need to perform the intervention. This situation may exemplify what the women referred to in the public consultation as “class interests.”

Difficulties associated with the social culture

Another important point raised was inability of the population to fully exercise their autonomy and their rights due to lack of information. This issue was reflected in the comments in phrases like “the population’s lack of awareness and information” and concern regarding “lack of access thereto by pregnant women and the fathers.”

For purposes of the present analysis, myths and paradigms were regarded as elements that reinforce this issue, cited in the responses as “outdated concepts and preconceptions” and “decades-old cultural paradigms and myths.”

Difficulties associated with political and management issues

Management-related issues, another point often mentioned in the women’s contributions, were cited as a factor hindering the implementation of a policy to support quality normal childbirth care. The comments referred to “lack of political will on the part of managers” (p. 30), “lack of interest on the part of City Hall and the Ministry of Health” (p. 34), and “… political maneuvers [that] prevent many resources being utilized in my municipality” (CONITEC, Public Consultation, Jan 2016, p. 136) (18). Another management-related issue that emerged from the women’s contributions was the remuneration received by physicians.

Remuneration of professionals who attend normal childbirth: It is much more profitable to perform 10 C-sections in a day than to attend a single delivery that lasts 12 hours (CONITEC, Public Consultation, Jan 2016, p. 23) (18).

The compensation received by health plan doctors should be fair, much higher than the current rates (CONITEC, Public Consultation, Jan 2016, p. 246) (18).

The comments also mentioned lack of oversight and compliance with Collegiate Directorate Resolution (RDC) 36 of the National Health Surveillance Agency (ANVISA), which refers to the operation of obstetric and neonatal health care services, and the Companions Law (21), which guarantees the parturient the right to be accompanied during labor, delivery, and the immediate postpartum period: “… the lack of oversight of compliance with RDC 36/2008 and the Attendant Law” (p. 181).

Structural issues that were cited included shortage of professionals, inadequate hospital facilities, and in some cases, the absence of maternity services. Another structure-related problem reported was the absence of birth homes and the shortage of obstetric nurses and midwives: “The absence of childbirth clinics and lack of access to obstetric nurses and midwives to attend women during labor” (CONITEC, Public Consultation, Jan 2016, p. 235).

DISCUSSION

The present study analyzed the contribution of Brazilian women who participated in a public consultation on the National Guidelines on Normal Childbirth Care, with emphasis on the difficulties perceived by these users regarding implementation of the Guidelines. Among the reports of difficulties, the comments on professional education and culture were consistent with previous findings. In an earlier national survey, Childbirth in Brazil, in which 23 894 women from all the regions of the country were interviewed about their experience with obstetric interventions during labor and childbirth (22), good practices during labor were reported by fewer than 50% of the women. In terms of practices considered to be detrimental, Loyal et al. (23), reporting on a 2017 study of 10 675 women attended at 606 public and mixed maternity services in the Rede Cegonha (“Stork Network”), found lower but still significant percentages for episiotomy (27.7% versus 47.3%) and the Kristeller maneuver (15.9% versus. 36.1%).

In 2015, to call international attention to the problem of detrimental practices during childbirth, the World Health Organization (WHO) published a statement on the prevention and elimination of disrespect and abuse during facility-based childbirth (24). WHO also issued specific recommendations on intrapartum care for a positive childbirth experience (25) and lent its support to the International Childbirth Initiative (ICI) (26), a partnership with the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO). The subject is so important and timely that a 2019 systematic review of studies in Latin America found a 43% prevalence of disrespectful attitudes and abuse of women during the childbirth—evidence that this violence is inherent in the culture of the services (27).

In Brazil, recent discussions about the autonomy of women and the role of the medical professional led the Federal Council of Medicine (CFM) to adopt a resolution which states in its Article 1 that, given the information it has received regarding the risks and benefits of cesarean and vaginal delivery, the parturient has the right to opt for cesarean delivery in elective situations (starting in the 39th week) (28).

Data from the study Childbirth in Brazil (22) revealed that only 27.6% of women preferred cesarean delivery at the start of their gestation, with differences depending on the sector where they were receiving care (the public and supplementary health systems) and their number of previous pregnancies. It is important to point out that, regardless of the wishes of the women and the health care sector, the proportion of C-sections was higher than the initial preference of these women.

A study conducted in maternity services in the Southern region of Brazil (29) found that the following factors were significantly associated with requests for C-sections: high levels of schooling and household income; prenatal care received in the private sector; history of being seen by the same physician throughout the prenatal period; and absence of any reported comorbidity during the pregnancy. In other words, the occurrence of requested C-sections was higher among women with fewer risks of complications during pregnancy and delivery.

The women’s comments also referred to difficulties associated with the social culture, lack of information, and myths and paradigms. In this same vein, WHO recommendations on nonclinical interventions to reduce unnecessary C-sections (30) indicate that health education for women is an essential component of prenatal care. Having this education empowers them to have an informed dialogue with health professionals.

An example of how lack of information can affect implementation of the Guidelines can be seen in the above-cited WHO document on intrapartum care (25), which indicates that some women may be reluctant to use epidural analgesia because of fears about the procedure, its risks, and pain; conflicted feelings; or self-blame. Awareness that high C-section rates in Brazil and other Latin American countries are strongly correlated with sociocultural factors (31) makes it all the more important to engage in effective communication and provide these women with access to information.

With regard to difficulties associated with policy and management issues, it is important to remember that a woman’s right to ongoing care during labor, childbirth, and the immediate postpartum period has been guaranteed under Brazilian law since 2005 (21). However, even though this statute has been in place for 15 years, compliance continues to be inconsistent. Diniz et al. (32) found that 24.5% of the women in the national Childbirth in Brazil study had not been attended at any time during their hospitalization, with significant differences between the public (29.5%) and private (4.7%) sectors.

A study in Brazil conducted by Bittencourt et al. (33) found that 70.6% and 98.8% of public and private hospitals, respectively, had minimum maternal emergency equipment. In terms of such equipment for newborns, the proportions were 67.7% and 87.8%, respectively. The situation varied regionally. Of public hospitals in the Northern region, 56.3% had maternal and newborn emergency equipment, while this availability was 44.8% in the Northeastern region. These figures illustrate the problem of inadequate hospital structure, which is an important barrier to implementation of the Guidelines aimed at ensuring quality care. To evaluate human resources, the indicator used by Bittencourt et al. was the presence of medical and nursing coordinators with professional certification in obstetrics and neonatology. The authors found that the majority of physicians in their study had credentials in obstetrics: 94.4% in the public hospitals and 100.0% in the private hospitals. For neonatology, the percentages were 94.4% and 77.0%, respectively. With regard to the presence of specialized nursing coordinators, the figures were lower in both specialties: 58.0% had certification in obstetrics and 64.4% in neonatology in the public hospitals, while these figures were 62.7% and 71.8% in the private hospitals. These findings support the women’s concerns regarding the shortage of trained human resources (33).

Although the present study is based on sound methods, it does have some limitations—among them, the size of the sample size and selection bias due to the fact that the data were not actively collected. The profile of the women who participate in a public consultation is potentially differentiated by such parameters as access to the Internet and the ability to volunteer their time to contribute a text of this kind. Also, since the findings are based on conclusions directed toward implementation of the Guidelines, we cannot state that they reflect the views of all Brazilian women.

In interpreting the comments studied, it is also important to consider the possibility that most of the respondents are active in the cause of childbirth care in Brazil. It can also be assumed that these women have good access to information and that they have therefore developed an inquiring attitude toward the care that is offered in both the public and private sectors.

The present analysis has shown that the perceptions of the women who contributed to the public consultation on barriers to implementation of the Guidelines for Normal Childbirth Care focused mainly on difficulties associated with professional education and culture, the social culture, and political and management issues. Barring the limitations mentioned, it is believed that this study makes an important contribution to the implementation of public policies on the health of women by identifying potential critical points for further study or interventions aimed at overcoming or reducing some of the barriers to implementation of the Guidelines for Normal Childbirth Care.

Financing.

This study was financed by the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), by the Special Program of Research and Training in Diseases Tropical (TDR), and by the Alliance for Research in Policies and Health Systems (AHPSR) through a donation to the project “Barriers and Strategies for Implementation of the Guidelines for Normal Childbirth in Brazil” (Call for Proposals on Embedding Research for the Sustainable Development Goals [ER-SDG]). The funding agencies did not have any role in the project design, the analysis process, interpretation of the data, or drafting of the manuscript.

Disclaimer.

Authors hold sole responsibility for the views expressed in the manuscript, which may not necessarily reflect the opinion or policy of the RPSP/PAJPH or the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO).

Footnotes

Authors’ contribution.

All the authors took part in conceiving the original idea and planning the studies. ATV collected the data. ATV and DR analyzed the data. ATV, JOB, and DR conducted the interpretation of the results. ATV wrote the first version of the manuscript. All the authors reviewed and approved the final version.

Conflicts of interest.

None declared by the authors.

Orange boxes correspond to families of difficulty; red arrows represent the relationships between the families difficulty and the codes; black arrows represent the relationship between the codes.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brasil, Ministério da Saúde Sistema Único de Saúde. [Accessed in 11 September 2020]. Available at: https://www.saude.gov.br/sistema-unico-de-saude.; 1. Brasil, Ministério da Saúde. Sistema Único de Saúde. Available at: https://www.saude.gov.br/sistema-unico-de-saude Accessed in 11 September 2020.

- 2.Brasil, Agência Nacional de Saúde Suplementar (ANS) Beneficiários de planos privados de saúde, por cobertura assistencial (Brasil – 2010-2020) [Accessed in 11 September 2020]. Available at: http://www.ans.gov.br/perfil-do-setor/dados-gerais.; 2. Brasil, Agência Nacional de Saúde Suplementar (ANS). Beneficiários de planos privados de saúde, por cobertura assistencial (Brasil – 2010-2020). Available at: http://www.ans.gov.br/perfil-do-setor/dados-gerais Accessed in 11 September 2020.

- 3.Brasil, Ministério da Saúde Painel de Monitoramento de Nascidos Vivos segundo Classificação de Risco Epidemiológico (Grupos de Robson) [Accessed in 14 June 2020]. Available at: http://svs.aids.gov.br/dantps/centrais-de-conteudos/paineis-de-monitoramento/natalidade/grupos-de-robson/2018.; 3. Brasil, Ministério da Saúde. Painel de Monitoramento de Nascidos Vivos segundo Classificação de Risco Epidemiológico (Grupos de Robson). Available at: http://svs.aids.gov.br/dantps/centrais-de-conteudos/paineis-de-monitoramento/natalidade/grupos-de-robson/2018 Accessed in 14 June 2020.

- 4.Oliveira RR de, Melo EC, Novaes ES, Ferracioli PLRV, Mathias TA de F. Factors associated to Caesarean delivery in public and private health care systems. Rev Esc Enferm USP. 2016;50(5):733–740. doi: 10.1590/s0080-623420160000600004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 4. Oliveira RR de, Melo EC, Novaes ES, Ferracioli PLRV, Mathias TA de F. Factors associated to Caesarean delivery in public and private health care systems. Rev Esc Enferm USP. 2016;50(5):733–40. 10.1590/s0080-623420160000600004 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Brasil, Ministério da Saúde Gabinete do Ministro. Portaria 1 459/2011. [Accessed in November 2020]. Available at: http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/saudelegis/gm/2011/prt1459_24_06_2011.html.; 5. Brasil, Ministério da Saúde. Gabinete do Ministro. Portaria 1 459/2011. Available at: http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/saudelegis/gm/2011/prt1459_24_06_2011.html Accessed in November 2020.

- 6.Brasil, Agência Nacional de Saúde Suplementar (ANS) Resolução Normativa 368/2015. [suplementar Accessed in November 2020]. Available at: https://www.ans.gov.br/component/legislacao/?view=legislacao&task=TextoLei&format=raw&id=Mjg5Mg==#:~:text=Disp%C3%B5e%20sobre%20o%20direito%20de,no%20%C3%A2mbito%20da%20sa%C3%BAde%20.; 6. Brasil, Agência Nacional de Saúde Suplementar (ANS). Resolução Normativa 368/2015. Available at: https://www.ans.gov.br/component/legislacao/?view=legislacao&task=TextoLei&format=raw&id=Mjg5Mg==#:~:text=Disp%C3%B5e%20sobre%20o%20direito%20de,no%20%C3%A2mbito%20da%20sa%C3%BAde%20 suplementar Accessed in November 2020.

- 7.Brasil, Ministério da Saúde Secretaria de Atenção à Saúde. Portaria n° 353, de 14 de fevereiro de 2017. Aprova as Diretrizes Nacionais de Assistência ao Parto Normal. [Accessed in November 2020]. Available at: http://conitec.gov.br/images/Protocolos/Diretrizes/DDT_Assistencia_PartoNormal.pdf.; 7. Brasil, Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Atenção à Saúde. Portaria n° 353, de 14 de fevereiro de 2017. Aprova as Diretrizes Nacionais de Assistência ao Parto Normal. Available at: http://conitec.gov.br/images/Protocolos/Diretrizes/DDT_Assistencia_PartoNormal.pdf Accessed in November 2020.

- 8.Fervers B, Burgers JS, Voellinger R, Brouwers M, Browman GP, Graham ID, et al., editors. Guideline adaptation: an approach to enhance efficiency in guideline development and improve utilisation. BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;20(3):228–236. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs.2010.043257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 8. Fervers B, Burgers JS, Voellinger R, Brouwers M, Browman GP, Graham ID, et al. Guideline adaptation: an approach to enhance efficiency in guideline development and improve utilisation. BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;20(3):228–36. 10.1136/bmjqs.2010.043257 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Brasil Lei 12 401/2011. [Accessed in November 2020]. Available at: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2011-2014/2011/lei/l12401.htm#:~:text=Altera%20a%20Lei%20n%C2%BA%208.080,Sistema%20%C3%9Anico%20de%20Sa%C3%BAde%20%2D%20SUS.&text=%E2%80%9CArt.&text=A%20assist%C3%AAncia%20terap%C3%AAutica%20integral%20a,do%20inciso%20I%20do%20art.; 9. Brasil. Lei 12 401/2011. Available at: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2011-2014/2011/lei/l12401.htm#:~:text=Altera%20a%20Lei%20n%C2%BA%208.080,Sistema%20%C3%9Anico%20de%20Sa%C3%BAde%20%2D%20SUS.&text=%E2%80%9CArt.&text=A%20assist%C3%AAncia%20terap%C3%AAutica%20integral%20a,do%20inciso%20I%20do%20art Accessed in November 2020.

- 10.Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Cluzeau F, Feder G, et al., editors. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. Can Med Assoc J. 2010;182(18):E839–E842. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 10. Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, et al. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. Can Med Assoc J. 2010;182(18): E839–42. 10.1503/cmaj.090449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Harrison MB, Graham ID, van den Hoek J, Dogherty EJ, Carley ME, Angus V. Guideline adaptation and implementation planning: a prospective observational study. Implement Sci. 2013;8(1):49. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 11. Harrison MB, Graham ID, van den Hoek J, Dogherty EJ, Carley ME, Angus V. Guideline adaptation and implementation planning: a prospective observational study. Implement Sci. 2013;8(1):49. 10.1186/1748-5908-8-49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Gagliardi AR, Marshall C, Huckson S, James R, Moore V. Developing a checklist for guideline implementation planning: review and synthesis of guideline development and implementation advice. Implement Sci. 2015;10(1):19. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0205-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 12. Gagliardi AR, Marshall C, Huckson S, James R, Moore V. Developing a checklist for guideline implementation planning: review and synthesis of guideline development and implementation advice. Implement Sci. 2015;10(1):19. 10.1186/s13012-015-0205-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) NICE; 2016. Improving how patients and the public can help develop NICE guidance and standards. [Google Scholar]; 13. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Improving how patients and the public can help develop NICE guidance and standards. NICE; 2016.

- 14.Chapman E, Haby MM, Toma TS, de Bortoli MC, Illanes E, Oliveros MJ, et al. Knowledge translation strategies for dissemination with a focus on healthcare recipients: an overview of systematic reviews. Implement Sci. 2015;15(1):14. doi: 10.1186/s13012-020-0974-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 14. Chapman E, Haby MM, Toma TS, de Bortoli MC, Illanes E, Oliveros MJ, et al. Knowledge translation strategies for dissemination with a focus on healthcare recipients: an overview of systematic reviews. Implement Sci. 2020;15(1):14. 10.1186/s13012-020-0974-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Brasil. Ministério da Saúde . Brasília: Ministério da Saúde; 2016. Entendendo a Incorporação de Tecnologias em Saúde no SUS: como se envolver. [Google Scholar]; 15. Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Entendendo a Incorporação de Tecnologias em Saúde no SUS: como se envolver. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde; 2016.

- 16.Oliveira CF, Ribeiro AAV, Luquine Jr CD, de Bortoli MC, Toma TS, Chapman EMG, et al., editors. Barreiras à implementação de recomendações para assistência ao parto normal: revisão rápida de evidências Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2020;44:e132. doi: 10.26633/RPSP.2020.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 16. Oliveira CF, Ribeiro AAV, Luquine Jr CD, de Bortoli MC, Toma TS, Chapman EMG, et al. Barreiras à implementação de recomendações para assistência ao parto normal: revisão rápida de evidências. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2020;44:e132. 10.26633/RPSP.2020.132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Barreto JOM, Bortoli MC, Luquine Jr. CD, Oliveira CF, Toma TS, Ribeiro AAV, et al., editors. Barreiras e estratégias para implementação de Diretrizes Nacionais do Parto Normal no Brasil. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2020;44:e120. doi: 10.26633/RPSP.2020.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 17. Barreto JOM, Bortoli MC, Luquine Jr. CD, Oliveira CF, Toma TS, Ribeiro AAV, et al. Barreiras e estratégias para implementação de Diretrizes Nacionais do Parto Normal no Brasil. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2020;44:e120. 10.26633/RPSP.2020.120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Comissão Nacional de Incorporação de Tecnologias no SUS (CONITEC) Contribuições da Consulta Pública - PCDT - Diretriz Nacional de Assistência ao Parto Normal - CONITEC. Consulta Pública no 1, de 8 de janeiro de 2016. [Accessed in November 2020]. http://conitec.gov.br/images/Consultas/Contribuicoes/2016/CP_CONITEC_01_2016_PCDT_Diretriz_Nacional_de_Assist%C3%AAncia_ao_Parto_Normal.pdf.; 18. Comissão Nacional de Incorporação de Tecnologias no SUS (CONI- TEC). Contribuições da Consulta Pública - PCDT - Diretriz Nacional de Assistência ao Parto Normal - CONITEC. Consulta Pública no 1, de 8 de janeiro de 2016. Available at: http://conitec.gov.br/images/Consultas/Contribuicoes/2016/CP_CONITEC_01_2016_PCDT_Diretriz_Nacional_de_Assist%C3%AAncia_ao_Parto_Normal.pdf Accessed in November 2020.

- 19.Bardin L. São Paulo: Edições 70; 2016. Análise de conteúdo. [Google Scholar]; 19. Bardin L. Análise de conteúdo. São Paulo: Edições 70; 2016.

- 20.Forero R, Nahidi S, De Costa J, Mohsin M, Fitzgerald G, Gibson N, et al., editors. Application of four-dimension criteria to assess rigour of qualitative research in emergency medicine. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(120) doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-2915-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 20. Forero R, Nahidi S, De Costa J, Mohsin M, Fitzgerald G, Gibson N, et al. Application of four-dimension criteria to assess rigour of qualitative research in emergency medicine. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(120). 10.1186/s12913-018-2915-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Brasil, Presidência da República Lei 11 108/2005. [Accessed in November 2020]. Available at: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2004-2006/2005/lei/l11108.htm.; 21. Brasil, Presidência da República. Lei 11 108/2005. Available at: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2004-2006/2005/lei/l11108.htm Accessed in November 2020.

- 22.Leal M do C, Pereira APE, Domingues RMSM, Filha MMT, Dias MAB, Nakamura-Pereira M, et al., editors. Intervenções obstétricas durante o trabalho de parto e parto em mulheres brasileiras de risco habitual. Cad Saude Publica. 2014;30(suppl 1):S17–S32. doi: 10.1590/0102-311X00151513. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; 22. Leal M do C, Pereira APE, Domingues RMSM, Filha MMT, Dias MAB, Nakamura-Pereira M, et al. Intervenções obstétricas durante o trabalho de parto e parto em mulheres brasileiras de risco habitual. Cad Saude Publica. 2014;30(suppl 1):S17–32. 10.1590/0102-311X00151513 [DOI]

- 23.Leal M do C, Bittencourt S de A, Esteves-Pereira AP, Ayres BV da S, Silva LBRA de A, Thomaz EBAF, et al., editors. Avanços na assistência ao parto no Brasil: resultados preliminares de dois estudos avaliativos. Cad Saude Publica. 2019;35(7) doi: 10.1590/0102-311x00223018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 23. Leal M do C, Bittencourt S de A, Esteves-Pereira AP, Ayres BV da S, Silva LBRA de A, Thomaz EBAF, et al. Avanços na assistência ao parto no Brasil: resultados preliminares de dois estudos avaliativos. Cad Saude Publica. 2019;35(7). 10.1590/0102-311x00223018 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.World Health Organization (WHO) Geneva: WHO; 2015. [Accessed in November 2020]. The prevention and elimination of disrespect and abuse during facility-based childbirth. Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/134588/WHO_RHR_14.23_eng.pdf;jsessionid=CDC29B6324A27B5F7889C28A4C0A5990?sequence=1. [Google Scholar]; 24. World Health Organization (WHO). The prevention and elimination of disrespect and abuse during facility-based childbirth. Geneva: WHO; 2015. Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/134588/WHO_RHR_14.23_eng.pdf;jsessionid=CDC29B6324A27B5F7889C28A4C0A5990?sequence=1 Accessed in November 2020.

- 25.World Health Organization (WHO) Geneva: WHO; 2018. [Accessed in November 2020]. HO recommendations: intrapartum care for a positive childbirth experience. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241550215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 25. World Health Organization (WHO). WHO recommendations: intrapartum care for a positive childbirth experience. Geneva: WHO; 2018. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241550215 Accessed in November 2020. [PubMed]

- 26.Lalonde A, Herschderfer K, Pascali-Bonaro D, Hanson C, Fuchtner C, Visser GHA. The International Childbirth Initiative: 12 steps to safe and respectful MotherBaby-Family maternity care. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2019;146(1):65–73. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.12844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 26. Lalonde A, Herschderfer K, Pascali-Bonaro D, Hanson C, Fuchtner C, Visser GHA. The International Childbirth Initiative: 12 steps to safe and respectful MotherBaby-Family maternity care. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2019 Jul;146(1):65-73. 10.1002/ijgo.12844 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Tobasía-Hege C, Pinart M, Madeira S, Guedes A, Reveiz L, Valdez-Santiago R, et al., editors. Irrespeto y maltrato durante el parto y el aborto en América Latina: revisión sistemática y metaanálisis. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2019;43:1. doi: 10.26633/RPSP.2019.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 27. Tobasía-Hege C, Pinart M, Madeira S, Guedes A, Reveiz L, Valdez-Santiago R, et al. Irrespeto y maltrato durante el parto y el aborto en América Latina: revisión sistemática y metaanálisis. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2019;43:1. 10.26633/RPSP.2019.36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Conselho Federal de Medicina (CFM) Resolução CFM no 2 144/2016. [Accessed in November 2020]. Available at: https://portal.cfm.org.br/images/stories/pdf/res21442016.pdf.; 28. Conselho Federal de Medicina (CFM). Resolução CFM no 2 144/2016. Available at: https://portal.cfm.org.br/images/stories/pdf/res21442016.pdf Accessed in November 2020.

- 29.Cesar JA, Sauer JP, Carlotto K, Montagner ME, Mendoza-Sassi RA. Cesarean section on demand: a population-based study in Southern Brazil. Rev Bras Saude Materno Infant. 2017;17(1):99–105. doi: 10.11606/S1518-8787.2019053001466. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; 29. Cesar JA, Sauer JP, Carlotto K, Montagner ME, Mendoza-Sassi RA. Cesarean section on demand: a population-based study in Southern Brazil. Rev Bras Saude Materno Infant. 2017;17(1):99–105. 10.11606/S1518-8787.2019053001466 [DOI]

- 30.World Health Organization (WHO) Geneva: WHO; 2018. [Accessed in November 2020]. WHO recommendations: non-clinical interventions to reduce unnecessary caesarean sections. Available at: https://www.who.int/repro-ductivehealth/publications/non-clinical-interventions-to-reduce-cs/en/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 30. World Health Organization (WHO). WHO recommendations: non-clinical interventions to reduce unnecessary caesarean sections. Geneva: WHO; 2018. Available at: https://www.who.int/repro-ductivehealth/publications/non-clinical-interventions-to-reduce-cs/en/ Accessed in November 2020. [PubMed]

- 31.Teixeira S, S Machado H. Who Caesarean Section Rate: Relevance and ubiquity at the present day – a review article. J Pregnancy Child Health. 2016;03(02) doi: 10.4172/2376-127X.1000233. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; 31. Teixeira S, S Machado H. Who Caesarean Section Rate: Relevance and ubiquity at the present day – a review article. J Pregnancy Child Health. 2016;03(02). 10.4172/2376-127X.1000233 [DOI]

- 32.Diniz CSG, D’Orsi E, Domingues RMSM, Torres JA, Dias MAB, Schneck CA, et al., editors. Implementação da presença de acompanhantes durante a internação para o parto: dados da pesquisa nacional Nascer no Brasil. Cad Saude Publica. 2014;30(suppl 1):S140–S153. doi: 10.1590/0102-311X00127013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; 32. Diniz CSG, D’Orsi E, Domingues RMSM, Torres JA, Dias MAB, Schneck CA, et al. Implementação da presença de acompanhantes durante a internação para o parto: dados da pesquisa nacional Nascer no Brasil. Cad Saude Publica. 2014;30(suppl 1):S140–53. 10.1590/0102-311X00127013 [DOI]

- 33.Bittencourt SD de A, Reis LG da C, Ramos MM, Rattner D, Rodrigues PL, Neves DCO, et al., editors. Estrutura das maternidades: aspectos relevantes para a qualidade da atenção ao parto e nascimento. Cad Saude Publica. 2014. pp. S208–S219. [DOI]; 33. Bittencourt SD de A, Reis LG da C, Ramos MM, Rattner D, Rodrigues PL, Neves DCO, et al. Estrutura das maternidades: aspectos relevantes para a qualidade da atenção ao parto e nascimento. Cad Saude Publica. 2014;(suppl 1):S208–19. 10.1590/0102-311X00176913 [DOI]