Summary

Drug‐induced photosensitivity, the development of phototoxic or photoallergic reactions due to pharmaceuticals and subsequent exposure to ultraviolet or visible light, is an adverse effect of growing interest. This is illustrated by the broad spectrum of recent investigations on the topic, ranging from molecular mechanisms and culprit drugs through epidemiological as well as public health related issues to long‐term photoaging and potential photocarcinogenic consequences. The present review summarizes the current state of knowledge on the topic while focusing on culprit drugs and long‐term effects. In total, 393 different drugs or drug compounds are reported to have a photosensitizing potential, although the level of evidence regarding their ability to induce photosensitive reactions varies markedly among these agents. The pharmaceuticals of interest belong to a wide variety of drug classes. The epidemiological risk associated with the use of photosensitizers is difficult to assess due to under‐reporting and geographical differences. However, the widespread use of photosensitizing drugs combined with the potential photocarcinogenic effects reported for several agents has major implications for health and safety and suggests a need for further research on the long‐term effects.

Photosensitivity: mechanisms and impact

The complete depiction of a complex matter such as drug‐induced photosensitivity in a single publication seems almost impossible, given the numerous reports on this topic. The present review therefore aims to cover two focal points. These are (1) the drugs responsible for photosensitive reactions and their consequences, and (2) the mechanisms of phototoxicity.

Drug‐induced photosensitive skin reactions are adverse drug reactions of significant interest. The first reports mentioning occurrence of dermatitis following contact with angelica or parsnips appeared in 1897 [1]. Photosensitive adverse events are usually categorized as either phototoxic or photoallergic, and additionally as either topical or systemic. While this classification is based on different pathophysiological mechanisms, several features illustrate the contrast between them, including incidence, immunization, onset after exposure and clinical appearance [2]. Photosensitizing agents are exogenous chromophores that absorb photons, commonly from solar radiation, leading to their activation and chemical reactions [3]. Photosensitive reactions are limited to specific parts of the electromagnetic spectrum, and occur mainly in the UVA range (wavelength 315–400 nm), although some drugs produce photosensitivity upon exposure to UVB radiation (280–315 nm) or even visible light (400–740 nm). A combined effect of different wavelengths has also been described [4].

Phototoxic reactions

Phototoxic reactions have a higher incidence than photoallergic reactions and can theoretically occur in any individual exposed to the respective agent and radiation, if the dose of either of the two involved factors exceeds a critical threshold [2, 5]6]. Phototoxic reactions are a dose‐dependent phenomenon with respect to both the drug and light exposure [7, 8]. The skin reactions vary depending on the responsible photosensitizer and its respective intracellular target, with some sensitizers even affecting multiple sites [9]. Erythema is the most common clinical manifestation and can be categorized according to its onset as immediate, delayed (12–24 h) or late‐onset erythema (24–120 h). Delayed‐onset erythema is often referred to as with “exaggerated sunburn”. Immediate reactions include burning or prickling sensations and edema. Hyperpigmentation and telangiectasia are additional long‐term features. Pseudoporphyria and photo‐onycholysis are rare but severe manifestations [9, 10, 11]. Phototoxic tissue damage is characterized histologically by dermal edema, dyskeratosis and necrosis of keratinocytes, in severe cases even pan‐epidermal [1, 12]. Especially in the case of pseudoporphyria the agents seem to concentrate at the dermo‐epidermal junction [9]. Due to its non‐immunological nature, phototoxicity can only occur in skin areas receiving light [13]. Delineation of clothing and its shading capacity is an important clinical feature when making a diagnosis [10].

Mechanisms of phototoxic skin damage

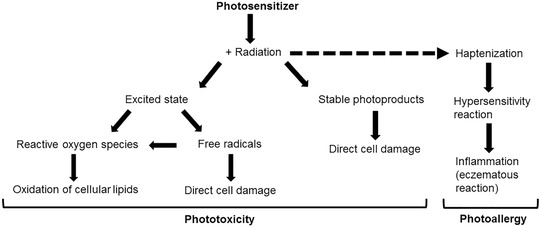

There are several pathways that ultimately lead to the observed phototoxic skin response, but initiation of a phototoxic drug reaction always starts with the absorption of UV radiation or visible light. When this happens, the molecule shifts a valence electron to the first available outer shell, thus abandoning its ground state and transforming to an excited state that is chemically unstable. The two following major photochemical pathways involve either an excited triplet state or free radicals. The excited triplet cascade leads to a transfer of energy, either directly to biomolecules or molecular oxygen, thus creating excited singlet oxygen, which corresponds to reactive oxygen species (ROS) [14, 15]. Oxidation of cellular lipids damages cellular components, which results in the clinically apparent skin reaction. Free radicals act by electron transfer, since they have an unpaired valence electron. This then leads to molecular changes of cellular components, which may result in a cytotoxic cellular burden and induce a macroscopically visible phototoxic skin reaction. Interaction of these free radicals with oxygen can also result in the generation of reactive oxygen species [10]. Formation of stable photoproducts by covalent binding of the photosensitizing agent to critical cell compartments and DNA can also cause tissue damage [16]. Figure 1 illustrates the different pathways of photosensitivity schematically.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of the major mechanisms of phototoxic and photoallergic tissue damage.

Reactive oxygen species are generated intracellularly due to various metabolic processes within the mitochondria. ROS have intracellular as well as extracellular functions, and can cause oxidative damage to the cell if its intrinsic antioxidant capacity is exceeded [4]. Since irradiation with UVA light leads to increased ROS generation, keratinocytes have several endogenous enzymatic and non‐enzymatic protective antioxidants [17]. These include catalase, glutathione peroxidase and superoxide dismutase to neutralize ROS; higher levels of these are found in the epidermis than in the dermis [18]. Mechanisms to repair damage to DNA and cell membranes as well as to remove damaged proteins have also been discovered [18, 19, 20]. With regular sunburn, keratinocytes are forced to undergo programmed cell death [21]. Sunburn is induced primarily by UVB radiation, which causes more direct DNA damage and is slower to repair than ROS damage. However, the majority of phototoxic reactions result from UVA exposure [7, 20]22].

In general, phototoxic drugs share common features: they have a low molecular weight (between 200 and 500 Daltons) and planar, tricyclic or polycyclic configurations. Their structure may incorporate heteroatoms, which enables resonance stabilization. However, no element or molecule has an automatic ability to induce phototoxicity, although some structural elements, such as aromatic chlorine substituents, are frequently seen in several photosensitizers [10]. Different drugs have different absorption spectra, and therefore have different action spectra regarding the development of phototoxicity, since the former correspond directly with the latter [2, 23].

Photoallergic Reactions

In photoallergic reactions the photosensitizer absorbs photons, which convert it into a biologically reactive chromophore [24]. This molecule binds to a protein within the dermis or epidermis, forming a complete antigen (haptenization) [25]. Langerhans cells process the antigen and present it via MHC II molecules to T cells that reside in lymph nodes. The following response is a homing of activated T lymphocytes into the skin. A photoallergic reaction is therefore a cell‐mediated type IV hypersensitivity reaction, and can only occur in previously sensitized patients [25, 26]. Such reactions are rare compared to phototoxic reactions, but have a low threshold dose similar to non‐photo‐induced cutaneous hypersensitivity reactions [2]. Data regarding the proportion of photoallergic reactions among cases of drug‐induced photosensitivity are scarce. However, out of 245 cases of drug‐induced photosensitivity diagnosed at the Dundee Photobiology Unit between 1970 and 2000, just a single case (0.04 %) was confirmed as a photo‐allergy [9]. Photo‐allergies present as eczematous eruptions in areas of skin that are exposed to radiation, but may lack the sharp delineation of phototoxic lesions and do not occur until 24 to 72 hours after exposure [1, 26]27]. An important feature that distinguishes photoallergic from phototoxic reactions is the typical “crescendo” pattern of the cutaneous manifestations, which is a typical feature of delayed‐type hypersensitivity reactions of the skin. This implies that in photoallergic reactions the cutaneous changes increase during the course of the disease, with a peak at about 48–72 hours after the onset of symptoms (crescendo pattern). This is different in phototoxic reactions, where clinical symptoms show a rapid increase to the maximum clinical manifestation after about 24–48 hours of UV exposure, which is followed by a gradual decrease for some days (decrescendo pattern) [1, 28]. The predominant pathogenesis is topically induced photoallergic contact dermatitis, while photo‐allergy induced by systemic agents is rather rare [29, 30]. However, a patient sensitized to a topical allergen may develop systemic contact dermatitis following further systemic application of this allergen [31].

Epidemiological burden

It is generally believed that drug‐induced photosensitivity is significantly under‐reported, due to the difficulty of clinical recognition and the lack of documentation in public databases [4]. The difficulty associated with documentation is increased by the fact that affected patients (and often health professionals) attribute “exaggerated sunburn” to other causes such as excessive sun exposure [32]. The incidence of photosensitive reactions is often reported as up to 8 % of all drug‐related cutaneous adverse effects (64 out of 799), based on the retrospective analysis of reports by Selvaag to the Norwegian Adverse Drug Reactions Committee between 1970 and 1994. This amounts to around 0.5 % of all reported side effects [33]. However, these approximations may overestimate the global incidence rates of drug‐induced photosensitivity due to two main facts. Firstly, individuals with a fair skin complexion (Caucasian skin type) are more susceptible to phototoxic reactions, while the higher melanin content of darker skins seems to offer some protection [34]. In photoallergic reactions this correlation cannot be observed due to their immunological nature [26]. In a Scandinavian country like Norway, where only 2.4 % of the inhabitants have an African ethnic background associated with a darker skin type [35], this constitutes a significant bias. Secondly, the number also seems to exceed figures reported in other studies. At the Dundee Photobiology Unit, 7 % of all diagnosed photodermatoses from 1970–2000 were classified as drug‐induced photosensitivity [9]. Additionally, an analysis of drug‐induced photosensitivity using the Japanese Adverse Drug Event Report (JADER) database by Nakao et al. revealed that between 2004 and 2016 only 0.08 % (330 out of 430,587) of all reports concerned photosensitive reactions [36]. When combining these findings, 8 % (and due to under‐reporting perhaps more) of all drug‐related cutaneous adverse effects appears to be a reasonable upper boundary for drug‐induced photosensitivity when focusing on high risk regions. Globally the incidence is likely lower, even in the light of a higher “dark figure”. However, these numbers only represent the portion of photosensitive reactions among (clinically apparent) photodermatoses; the incidence of drug‐induced photosensitivity itself is not known. In the light of recent reports on the potential carcinogenicity of photosensitive drugs, even subclinical photosensitive reactions may have major health implications when considering chronic drug intake and sun exposure [37]. Therefore, although 7 % of drug‐induced photosensitive reactions among all photodermatoses may seem a rather minor health impact, the global impact on health may still be significant. Given the unknown incidence combined with the high dark figure, the following data seem particularly intriguing. A study investigating the number of reimbursed dispensed packages containing potentially photosensitive drugs in Germany and Austria from 2000–2017 based on nation‐wide health insurance‐based databases revealed that of around 630 million (Germany) and 113 million (Austria) drugs dispensed per year, the mean percentages of photosensitive drugs dispensed were 49.5 % in Germany and 48.2 % in Austria [38]. One might conclude that exposure to potential photosensitizers is substantial, at least in industrialized countries. Given the potential impact of subclinical photosensitivity on carcinogenicity, these numbers raise concern, especially when dealing with increasing rates of chronic drug intake and global sun exposure.

Photosensitizing Drugs

As a result of the growing interest in photosensitive reactions and drugs that induce them, several reviews have been published on drug‐induced photosensitivity in the previous twenty years that mention high numbers of relevant drugs and/or drug compounds [3, 9]10, 26]39, 40]. The exact number of drugs reported differs substantially between these reviews, but drugs of the following drug classes are present in all published lists of photosensitive drugs: non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), antimicrobials, antihypertensives and antineoplastic drugs [3, 9]40]. A study regarding the dispensing rates of photosensitizing drugs in Austria and Germany found a total of 387 different drugs and drug compounds with phototoxic and/or photoallergic reactions [38]. Since this is the largest collection of potential photosensitizers that we are aware of, it served as the basis for development of an updated, even more extensive list summarizing all published photosensitive drugs. Furthermore, a PubMed search using the terms “drug‐induced photosensitivity”, “drug‐induced phototoxicity” and “drug‐induced photo‐allergy” was conducted to complement the list, resulting in the addition of six drugs in total. Table 1 includes the final list of potential photosensitizing drugs, categorized by drug classes and pharmacological effects. The final compilation consists of 393 different drugs and drug compounds that are potentially photosensitizing, and is therefore the largest of such registers known to the authors to date.

Table 1.

A compilation of photosensitizing drugs (total n = 393). Number in brackets indicates the number of agents assigned to the respective drug class/subclass. Agents in bold represent drugs with high evidence of their photosensitizing effects (number of publications n ≥ 15). Asterisks identify agents of which the first report concerning their photosensitizing effects have been published recently (2005 and later)

|

Cardiovascular (60) Diuretics (25) RAAS effecting (15) Antiarrhythmics (11) Ca2±‐channel antagonists (2) Antihypertensives (4) Others (3) |

Hydrochlorothiazide Furosemide Chlorothiazide Hydroflumethiazide Methyclothiazide Piretanide Polythiazide Trichlormethiazide Bemetizide Enalapril Ramipril Quinapril Captopril Fosinopril Amiodarone Dronedarone*c Disopyramide Procainamide Amlodipine Hydralazine Rilmenidine Clopidogrel |

Bendroflumethiazide Benzthiazide Bumetanide Butizide Cyclothiazide Chlorthalidone Metolazone Quinethazone Benazepril Lisinopril Moexipril Valsartan Candesartan* Diltiazem Verapamil Carvedilol Tilisolol Nifedipine Diazoxide Oxerutins |

Indapamide Triamterene Chlorothiazide Amiloride Torasemide Xipamide Ethacrynic acid Acetazolamide Spironolactone Losartan Olmesartan* Telmisartan* Irbesartan* Quinidine Propranolol Sotalol Methyldopa Triflusal |

|

Anti‐inflammatory (38) NSAIDs (28) COX‐2 inhibitors (6) Others (4) |

Naproxen Ketoprofen Tiaprofenic acid Piroxicam Carprofen Aceclofenac Diclofenac Mefenaminic acid Phenylbutazone Leflunomide Celecoxib Etodolac Heroin Gold |

Bexaprofen Diflunisal Nabumetone Benzydamine Flurbiprofen Ketorolac* Meclofenamate Nalidixic Acid Oxaprozin Rofecoxib Meloxicam Pentosan polysulfate |

Benoxafen Indoprofen Indomethacin Fenoprofen Sulindac Suprofen Ibuprofen Tolmetin Mesalazine Nimesulide Valdecoxib Achillea millefolium |

|

Antineoplastic (47) Alkylating (4) Antimetabolite (9) Anti‐microtubule (3) Anthracycline (1) |

Hydroxyurea Procarbazine Methotrexate Mercaptopurine Capecitabine Vinblastine Epirubicin |

Dacarbazine Pentostatin Tegafur/Uracil Tegafur Docetaxel |

Chlorambucil Thioguanine Tegafur/Gimeracil/Oteracil Fluorouracil Paclitaxel |

|

Small molecule inhibitors (14) Topoisomerase inhibitor (1) Monoclonal antibodies (6) Others (9) |

Vemurafenib* Vandetanib* Dabrafenib* Gefitinib* Lapatinib* Irinotecan Nivolumab* Eculizumab* Flutamide Midostaurin PEG Interferon* |

Cobimetinib Crizotinib* Dasatinib* Canartinib* Trametinib* Cetuximab* Panitumumab* Bicalutamide* Mitomycin Interferon alpha |

Regorafenib* Erlotinib* Imatinib* Alectinib Trastuzumab* Mogamulizumab* Rucaparib Anagrelide Arsenic |

|

Anti‐infectious (70) Fluorquinolones (16) Tetracyclines (7) Sulfonamides (5) Cephalosporins (3) Aminoglycosides (3) Antimycotics (6) Antituberculosis (6) Antiviral (11) Others (13) |

Lomefloxacin Enoxacin Ciprofloxacin Clinafloxacin Sparfloxacin Pefloxacin Tetracycline Doxycycline Demeclocycline Sulfamethoxazole Cotrimoxazole Cefazolin Kanamycin Griseofulvin Voriconazole Isoniazid Pyrazinamide Efavirenz Ritonavir Saquinavir Zalcitabine Quinine Chloroquine Hydroxychloroquine Azithromycin Atoraquone/proguanil |

Ulifloxacin Grepafloxacin Gemifloxacin Levofloxacin Fleroxacin Minocycline Oxytetracycline Sulfadiazine Sulfisoxazole Ceftazidime Streptomycin Terbinafine Ketoconazole Ethionamide Ethambutol Daclatasvir* Amantadine (Val‐)Ganciclovir Tenofovir Mefloquine Pyrimethamine Quinacrine Sulfadoxine |

Ofloxacin Trovafloxacin Gatifloxacin Moxifloxacin Norfloxacin Chlortetracycline Lymecycline Sulfasalazine Cefotaxime Gentamicin Itraconazole Rosemary Clofazamine Aminosalicylate sodium (Val‐)Aciclovir Simeprevir* Ribavirin Dapsone Furazolidone Methenamine Flucytosine |

|

Nervous system (80) Antidepressants (23) Antipsychotics (34) |

Hypericum Amitriptyline Imipramine Clomipramine Desipramine Trimipramine Nortriptyline Doxepin Promethazine Thioridazine |

Escitalopram Paroxetine Protriptyline Fluvoxamine Fluoxetine Sertraline* Citalopram Venlafaxine* Olanzapine* Clozapine |

Duloxetine* Isocarboxazid Phenelzine Tranylcypromine Amoxapine Trazodone Nefazodone Chlorprothixene Chlorpromazine |

|

Anticonvulsants/barbiturates (11) Triptans (4) Others (8) |

Fluphenazine Perphenazine Flupentixol Molindone Pimozide Thiothixene Ziprasidone Meprobamate Zolpidem Aripiprazole Carbamazepine Lamotrigine Phenytoin* Felbamate Sumatriptan Naratriptan Cevimeline Methylphenidate Ropinirole |

Haloperidol Thioxene Trimeprazine Prochlorperazine Trifluoperazine Alprazolam Chlordiazepoxide Clorazepate Triazolam Topiramate Valproic Acid Trimethadione Phenobarbital Zolmitriptan Bupropion Danazol Acamprosate |

Perazine Loxapine Mesoridazine Quetiapine Risperidone Eszopiclone Zaleplon Maprotiline Carisoprodol Butabarbital Butalbital Pentobarbital Almotriptan Procyclidine Trihexyphenidyl |

|

Metabolism/endocrinologic (53) Statins (5) Fibrates (3) Antidiabetics (12) Proton‐pump inhibitor (3) Xanthine‐oxidase inhibitor (2) Hormones (6) Antihistamines (19) Antithyroid (1) Others (1) |

Simvastatin Atorvastatin* Fenofibrate Chlorpropamide Tolbutamide Glyburide Glipizide Esomeprazole* Allopurinol Melatonin Hydrocortisone Mequitazine Repirinast Astemizole Azatadine Brompheniramine Chlorpheniramine Ranitidine Propylthiouracil Bergamot |

Pravastati* Pitavastatin* Bezafibrate Gliquidone Glymidine Acetohexamide Glimepiride Pantoprazole Febuxostat Estrogen Epoetin Alpha Clemastine Dexchlorpheniramine Hydroxyzine Meclizine Tripelennamine Triprolidine |

Rosuvastatin* Clofibrate Canagliflozin Sitagliptin* Metformin* Tolazamide Rabeprazole Progesterone Ethinyl estradiol Dimenhydrinate Cyproheptadine Diphenhydramine Loratadine Cetirizine Terfenadine |

|

Others (45) Antiseptic (1) Anticholinergic (6) Cholinergic (1) PDE5 inhibitors (2) Photosensitizers (11) |

Thimerosal Scopolamine Hyoscyamine Pilocarpine Sildenafil Porfimer sodium 8‐Methoxypsoralen 5‐Methoxypsoralen Anthracene |

Benzatropine Glycopyrrolate Vardenafil Aminolevulinic acid Temoporfin Verteporfin Protoporphyrin |

Atropine sulfate Tiotropium* Dihematoporphyrin Ether Trioxsalen Hematoporphyrin |

|

Interleukins (1) Retinoids (4) Antifibrotic (1) Immunosuppressant (6) Chemotherapy adjuvant (1) Phytotherapy (4) Additives (3) Antidote (1) Vitamins (2) Vaccines (1) |

Aldesleukin Isotretinoin Tretinoin Pirfenidone* Tacrolimus Azathioprine Mesna Ginseng Ruta Cyclamate Tiopronin Pyridoxin Smallpox |

Acitretin Omalizumab* Colchicine Hydrastis canadensis Tartrazine Acetylcysteine* |

Etretinate Tocilizumab *Interferon Beta Angelica sinensis Saccharin |

The major limitation of this list is the potential lack of sufficient scientific evidence regarding the photosensitizing potential of several agents. While randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trials of possible photosensitizing drugs using standardized photo‐testing would be desirable, a recent review by Blakely et al. found that the majority of reports focusing on this issue stem mainly from case reports and case series [40]. Kim et al. concluded in a review that most associations between oral drugs and phototoxicity are not supported by high‐quality evidence. Out of 240 eligible studies (with a total of 2,466 subjects), 1,134 cases of suspected phototoxicity were supported by either low or very low‐quality evidence, in total 89 % of all studies. Furthermore, they reported that photobiologic evaluation was performed in only 23 % of all studies, and challenge/re‐challenge tests were performed in only 10 % of cases [39]. The presented compilation is therefore a list of all potential photosensitizers discussed in the literature, but without a guarantee for completeness.

In addition, a systematic comparative analysis of the photosensitive potential of different photosensitizers would be desirable but is lacking so far. A recent research paper used the number of publications associating an agent with its capability to induce photosensitive cutaneous reactions as an indicator for its photosensitizing potential, which resulted in a “heatmap” of photosensitivity [38]. This indicator is incorporated into Table 1 in order to highlight agents with high numbers (n ≥ 15) of reports on photosensitivity (shown in bold). Recently discovered photosensitizers (2005 and later) are labeled with an asterisk. Nevertheless, the strongest evidence for the ability to induce phototoxic or photoallergic adverse effects is generally attributed to photo‐testing, photopatch testing or re‐challenge testing.

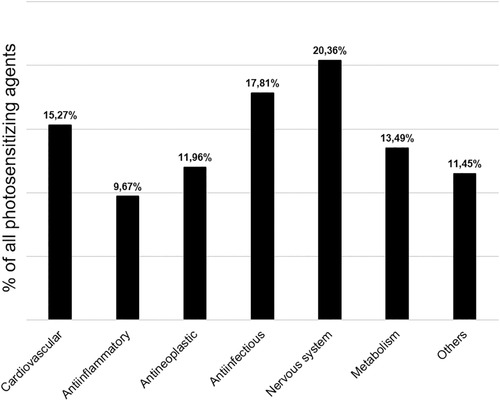

Distribution of photosensitizers among drug classes

The 393 agents and compounds that constitute a potential risk of inducing phototoxic or photoallergic reactions (and in some cases both) are summarized in Table 1. The classes that were specified for this review are neither arbitrary nor trivial. The drugs were assigned to a specific class and subclass based on the following principles. Agents were assessed using the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical/Defined Daily Dose (ATC/DDD) Classification established by the WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology [41]. There are difficulties associated with ATC codes in that (1) some countries establish their own ATC classifications and (2) many pharmaceuticals have more than one ATC code attached to them. Nevertheless, the ATC classification used for this review assisted in establishing an initial schematic classification. The drug classes were then merged or newly formed based on their main therapeutic target – to create a final total of seven major drug classes: Cardiovascular, Anti‐inflammatory, Antineoplastic, Anti‐infectious, Nervous system, Metabolism/Endocrine, and Others (consisting of agents that could not be assigned to any of the above‐mentioned groups). The subclasses were then categorized based on their primary indication or molecular target/structure. Again, agents that could not be assigned to any of the subclasses were allocated to their own subclass (“others”). The final classification resembles a clinical approach rather than a pharmacological or chemical classification.

Agents and compounds are not equally distributed among the different drug classes. The largest category is “Nervous system”, with 80 drugs, followed by “Anti‐infectious” (n = 70) and “Cardiovascular” (n = 60). The group “Anti‐inflammatory” contains the lowest number of agents (n = 38). The category “Antineoplastic” is arguably the only drug class where prescription and usage are limited to the respective field. Figure 2 illustrates the relative distribution of the seven drug classes and offers a pharmacological perspective. However, this distribution can be misleading from a clinical point of view. The categories “Nervous system” and “Anti‐infectious” both comprise several drugs that have been developed historically but have little or no significance in the clinical daily routine. Cardiovascular, anti‐inflammatory and endocrinological photosensitizers are currently highly prescribed medications [38]. Additional information regarding the distribution of agents and subclasses is shown in Supplementary Figure 1. The compilation and classification of photosensitizing drugs is primarily of academic interest since it provides no information on actual usage.

Figure 2.

Relative share of potential photosensitizers per major drug class.

Clinical Consequences

Diagnosis and Management

Patients developing photodistributed erythema (especially after apparently mild exposure to sunlight) should always be regarded as potential cases of photosensitivity. Diagnosis of photosensitive drug eruptions relies on obtaining a detailed medical history, in particular the chronology of medication with respect to the onset of the event [40]. Due to the various presentations of phototoxic and photoallergic reactions, inquiring into potential photosensitizers in the patient’s history is mandatory. Furthermore, differential diagnosis between phototoxic and photoallergic reactions is important, since the two reactions require different treatment and different strategies for preventing relapses. The macroscopic presentation of phototoxically damaged skin tends to reveal sharp lines of demarcation of shading clothes, but these lines can be blurred with photo‐allergies. Additionally, phototoxic reactions are more common with systemic drugs, while photo‐allergies nearly always occur after topical administration. Treatment of photosensitive eruptions should always be initiated by complete avoidance of the causative drug. In cases where the medication is indispensable to the patient, phototoxic effects can be minimized or prevented by dose reduction of either the drug or UV radiation. In photo‐allergies this is not feasible due to their immunological nature. Furthermore, photoprotective measures such as sunscreen and UV‐blocking clothing are necessary as a supplementary action. Appropriate topical steroids are an option for acute phototoxic cases. Photoallergic reactions may be treated in the same way as allergic contact dermatitis, with topical steroids, antihistamines and NSAIDs as primary treatment options [1, 9]10]. Appropriate tests for phototoxic reactions are usually reserved for unclear cases, since (at least in theory) all individuals develop them given enough exposure. However, suspected photoallergic dermatitis can be further investigated and confirmed with photopatch testing [11].

Photocarcinogenic Effects of Phototoxic Pharmaceuticals

Drug‐induced photocarcinogenesis is a result of taking photosensitizing medication. This is an ongoing problem and the subject of controversial scientific discussions. Even if several specific agents have been associated with photocarcinogenesis, probable mechanisms are still under investigation [32] and subject to debate [38]. The relationship between the use of photosensitive drugs and an increased risk of developing skin cancer is probably multifactorial. Such factors include susceptibility to solar radiation, patient age, cumulative dose and/or duration of treatment as well as other factors as yet unknown [42]. Furthermore, the absorption spectrum of the administered drug has been related to the histologic type of skin cancer. For example, amiloride (a diuretic with a maximal absorption in the UVA spectrum) has been associated with a dose‐dependent increase in the rate of developing squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) [43]. However, these investigations mostly represented associative analyses, and proof of a causative role of specific photosensitizing drugs in inducing a specific type of skin cancer due to a specific absorption spectrum has only been shown in sporadic cases. A moderate number of phototoxic drugs has already been associated with photocarcinogenesis in various epidemiological studies and in some cases even involving entire drug classes [43, 44, 45]. However, the quality of evidence for single agents is quite diverse. The strongest evidence for photocarcinogenic effects exists for psoralens (furocoumarins), for which the effects have been investigated in animal and human models. This includes studies that demonstrate increased risks of SCC [46], basal cell carcinoma (BCC) [47], and melanoma [48]. Other drugs for which an increased risk of skin cancer has been reported include: NSAIDs and fluoroquinolones [45], thiazide diuretics [43, 44]49, 50], tetracyclines [44], amiloride [43], amiodarone [51, 52], azathioprine [53, 54], vemurafenib [55, 56] and voriconazole [57, 58]. The increased risk of skin cancer after administration of photosensitizing drugs is likely higher for SCC and melanoma than for developing BCC, although for certain drugs there are studies that suggest an increased risk for BCC as well, such as amiodarone, ciprofloxacin or tetracycline [44, 59]. However, the available data are conflicting in several cases. For example, use of NSAIDs has been associated with a decreased risk of SCC and melanoma, especially with long‐term use [60]. To summarize, it can be stated that although there seems to be conflicting epidemiological data on the photocarcinogenic risk of long‐term prescription of photosensitizing drugs, an increasing number of studies demonstrate that there is probably a positive correlation between phototoxicity and photocarcinogenesis that requires particular caution with immunocompromised or immunosuppressed patients [4, 32]. Future studies on this question are urgently needed, in particular when considering the potential impact of photosensitizing and/or photocarcinogenic drugs on the health of aging populations with increasing rates of drug prescription.

Conflict of interest

None.

Supporting information

Figure S1

References

- 1. Dubakiene R, Kupriene M. Scientific problems of photosensitivity. Med Kaunas Lith 2006; 42(8): 619–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gould JW, Mercurio MG, Elmets CA. Cutaneous photosensitivity diseases induced by exogenous agents. J Am Acad Dermatol 1995; 33(4): 551–73; quiz 574–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Monteiro AF, Rato M, Martins C. Drug‐induced photosensitivity: Photoallergic and phototoxic reactions. Clin Dermatol 2016; 34(5): 571–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Khandpur S, Porter RM, Boulton SJ et al. Drug‐induced photosensitivity: new insights into pathomechanisms and clinical variation through basic and applied science. Br J Dermatol 2017; 176(4): 902–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Toback AC, Anders JE. Phototoxicity from systemic agents. Dermatol Clin 1986; 4(2): 223–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Allen JE. Drug‐induced photosensitivity. Clin Pharm 1993; 12(8): 580–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Vassileva SG, Mateev G, Parish LC. Antimicrobial photosensitive reactions. Arch Intern Med 1998; 158(18): 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Morison WL. Clinical practice. Photosensitivity. N Engl J Med 2004; 350(11): 1111–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ferguson J. Photosensitivity due to drugs. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed 2002; 18(5): 262–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Moore DE. Drug‐induced cutaneous photosensitivity: incidence, mechanism, prevention and management. Drug Saf 2002; 25(5): 345–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Frosch PJ, Menné T, Lepoittevin J‐P. Contact dermatitis. [Online], Springer: Berlin; New York, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mammen L, Schmidt CP. Photosensitivity reactions: a case report involving NSAIDs. Am Fam Physician 1995; 52(2): 575–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ljunggren B, Bjellerup M. Systemic drug photosensitivity. Photodermatol 1986; 3(1): 26–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Moore DE. Mechanisms of photosensitization by phototoxic drugs. Mutat Res 1998; 422(1): 165–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shimoda K, Kato M. Involvement of reactive oxygen species, protein kinase C, and tyrosine kinase in prostaglandin E2 production in Balb/c 3T3 mouse fibroblast cells by quinolone phototoxicity. Arch Toxicol 1998; 72(5): 251–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cimino GD, Gamper HB, Isaacs ST et al. Psoralens as photoactive probes of nucleic acid structure and function: organic chemistry, photochemistry, and biochemistry. Annu Rev Biochem 1985; 54: 1151–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pandel R, Poljšak B, Godic A et al. Skin photoaging and the role of antioxidants in its prevention. ISRN Dermatol 2013; 2013: 930164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shindo Y, Witt E, Han D et al. Enzymic and non‐enzymic antioxidants in epidermis and dermis of human skin. J Invest Dermatol 1994; 102(1): 122–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Briganti S, Picardo M. Antioxidant activity, lipid peroxidation and skin diseases. What’s new. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol JEADV 2003; 17(6): 663–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Besaratinia A, Kim S‐I, Pfeifer GP. Rapid repair of UVA‐induced oxidized purines and persistence of UVB‐induced dipyrimidine lesions determine the mutagenicity of sunlight in mouse cells. FASEB J Off Publ Fed Am Soc Exp Biol 2008; 22(7): 2379–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ziegler A, Jonason AS, Leffell DJ et al. Sunburn and p53 in the onset of skin cancer. Nature 1994; 372(6508): 773–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Willis I, Cylus L. UVA erythema in skin: is it a sunburn? J Invest Dermatol 1977; 68(3): 128–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zaheer MR, Gupta A, Iqbal J et al. Molecular mechanisms of drug photodegradation and photosensitization. Curr Pharm Des 2016; 22(7): 768–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lankerani L, Baron ED. Photosensitivity to exogenous agents. J Cutan Med Surg 2004; 8(6): 424–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Neumann NJ, Schauder S. [Phototoxic and photoallergic reactions]. Hautarzt Z Dermatol Venerol Verwandte Geb 2013; 64(5): 354–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Glatz M, Hofbauer GFL. Phototoxic and photoallergic cutaneous drug reactions. Chem Immunol Allergy 2012; 97: 167–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Coleman JJ, Cox AR. Antihypertensive drugs. In: Side Effects of Drugs Annual Elsevier 2014; 35: 363–85. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yokoyama WM. Contact hypersensitivity: not just T cells! Nat Immunol 2006; 7(5): 437–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wilm A, Berneburg M. Photoallergy. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2015; 13(1): 7–12; quiz 13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. González E, González S. Drug photosensitivity, idiopathic photodermatoses, and sunscreens. J Am Acad Dermatol 1996; 35(6): 871–85; quiz 886–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Veien NK. Systemic contact dermatitis. Int J Dermatol 2011; 50(12): 1445–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ibbotson S. Drug and chemical induced photosensitivity from a clinical perspective. Photochem Photobiol Sci 2018; 17(12): 1885–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Selvaag E. Clinical drug photosensitivity. A retrospective analysis of reports to the Norwegian Adverse Drug Reactions Committee from the years 1970–1994. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed 1997; 13(1–2): 21–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nakamura M, Henderson M, Jacobsen G et al. Comparison of photodermatoses in African‐Americans and Caucasians: a follow‐up study. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed 2014; 30(5): 231–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kunst JR, Phillibert EN. Skin‐tone discrimination by Whites and Africans is associated with the acculturation of African immigrants in Norway. PloS One 2018; 13(12): e0209084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nakao S, Hatahira H, Sasaoka S et al. Evaluation of drug‐induced photosensitivity using the Japanese adverse drug event report (JADER) database. Biol Pharm Bull 2017; 40(12): 2158–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Schmidt SA, Schmidt M, Mehnert F et al. Use of antihypertensive drugs and risk of skin cancer. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol JEADV 2015; 29(8): 1545–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hofmann GA, Gradl G, Schulz M et al. The frequency of photosensitizing drug dispensings in Austria and Germany: a correlation with their photosensitizing potential based on published literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020; 34(3): 589–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kim WB, Shelley AJ, Novice K et al. Drug‐induced phototoxicity: A systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol 2018; 79(6): 1069–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Blakely KM, Drucker AM, Rosen CF. Drug‐induced photosensitivity‐an update: culprit drugs, prevention and management. Drug Saf 2019; 42(7): 827–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. ATC/DDD Index 2020. 2019[Online] 2019 [cited 2020]. Available from: https://www.whocc.no/atc_ddd_index/ [Last accessed August 5, 2020].

- 42. Robinson SN, Zens MS, Perry AE et al. Photosensitizing agents and the risk of non‐melanoma skin cancer: a population‐based case‐control study. J Invest Dermatol 2013; 133(8): 1950–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Jensen AØ, Thomsen HF, Engebjerg MC et al. Use of photosensitising diuretics and risk of skin cancer: a population‐based case‐control study. Br J Cancer 2008; 99(9): 1522–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kaae J, Boyd HA, Hansen AV et al. Photosensitizing medication use and risk of skin cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2010; 19(11): 2942–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Siiskonen SJ, Koomen ER, Visser LE et al. Exposure to phototoxic NSAIDs and quinolones is associated with an increased risk of melanoma. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2013; 69(7): 1437–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Stern RS, Thibodeau LA, Kleinerman RA et al. Risk of cutaneous carcinoma in patients treated with oral methoxsalen photochemotherapy for psoriasis. N Engl J Med 1979; 300(15): 809–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Stern RS, Lange R. Non‐melanoma skin cancer occurring in patients treated with PUVA five to ten years after first treatment. J Invest Dermatol 1988; 91(2): 120–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Stern RS. Photocarcinogenicity of drugs. Toxicol Lett 1998; 102–3: 389–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ruiter R, Visser LE, Eijgelsheim M et al. High‐ceiling diuretics are associated with an increased risk of basal cell carcinoma in a population‐based follow‐up study. Eur J Cancer 2010; 46(13): 2467–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Addo HA, Ferguson J, Frain‐Bell W. Thiazide‐induced photosensitivity: a study of 33 subjects. Br J Dermatol 1987; 116(6): 749–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Maoz KB‐A, Dvash S, Brenner S et al. Amiodarone‐induced skin pigmentation and multiple basal‐cell carcinomas. Int J Dermatol 2009; 48(12): 1398–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Monk B. Amiodarone‐induced photosensitivity and basal‐cell carcinoma. Clin Exp Dermatol 1990; 15(4): 319–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Perrett CM, Walker SL, O’Donovan P et al. Azathioprine treatment photosensitizes human skin to ultraviolet A radiation. Br J Dermatol 2008; 159(1): 198–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Molina BD, Leiro MGC, Pulpón LA et al. Incidence and risk factors for nonmelanoma skin cancer after heart transplantation. Transplant Proc 2010; 42(8): 3001–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Lacouture ME, Duvic M, Hauschild A et al. Analysis of dermatologic events in vemurafenib‐treated patients with melanoma. The Oncologist 2013; 18(3): 314–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Su F, Viros A, Milagre C et al. RAS mutations in cutaneous squamous‐cell carcinomas in patients treated with BRAF inhibitors. N Engl J Med 2012; 366(3): 207–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Williams K, Mansh M, Chin‐Hong P et al. Voriconazole‐associated cutaneous malignancy: a literature review on photocarcinogenesis in organ transplant recipients. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 58(7): 997–1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Miller DD, Cowen EW, Nguyen JC et al. Melanoma associated with long‐term voriconazole therapy: a new manifestation of chronic photosensitivity. Arch Dermatol 2010; 146(3): 300–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Monk BE. Basal cell carcinoma following amiodarone therapy. Br J Dermatol 1995; 133(1): 148–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Johannesdottir SA, Chang ET, Mehnert F et al. Nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs and the risk of skin cancer: a population‐based case‐control study. Cancer 2012; 118(19): 4768–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1