Food allergy (FA) affects approximately 8% of children in the United States.1 The strongest and most established risk factor for the development of FA is atopic dermatitis (AD), a pruritic inflammatory skin disease that is most common in children.2 The HealthNuts cohort study found that 1 in 5 Australian infants with AD were allergic to peanut, egg white, or sesame compared with 1 in 25 infants without AD,2 indicating a strong link between AD and FA. A leading theory for how AD predisposes patients to the development of FA is referred to as the dual allergen exposure hypothesis, which proposes that allergic sensitization to food can occur through cutaneous exposure and the altered skin barrier in AD results in increased permeability to food allergens.3

In this study, we evaluate the prevalence of physician-diagnosed AD and current FA using a US population-based, cross-sectional questionnaire that was administered between October 2015 and September 2016. The survey extended our 2009–2010 childhood FA prevalence survey and assessed other atopic comorbidities (eg, AD). Informed consent was obtained from all participants, and the Northwestern University Institutional Review Board approved all study activities.

Because the chief aim of the survey instrument was to assess current FA prevalence, parents provided a detailed history regarding any suspected food allergies for their child, including if their child had a physician diagnosis of FA. A systematic procedure was used to exclude parent-reported allergies that did not meet our stringent criteria for a convincing IgE-mediated allergy.1 In addition, parents were asked if their child had a physician-diagnosis of FA, eczema or atopic dermatitis (current or past), and other chronic atopic conditions. Parents were also asked about their own atopic disease history. Complex survey-weighted proportions were estimated to systematically compare participant characteristics and allergic disease status among the US population. The full description of this process and statistical analysis can be referenced in the article by Gupta et al.1

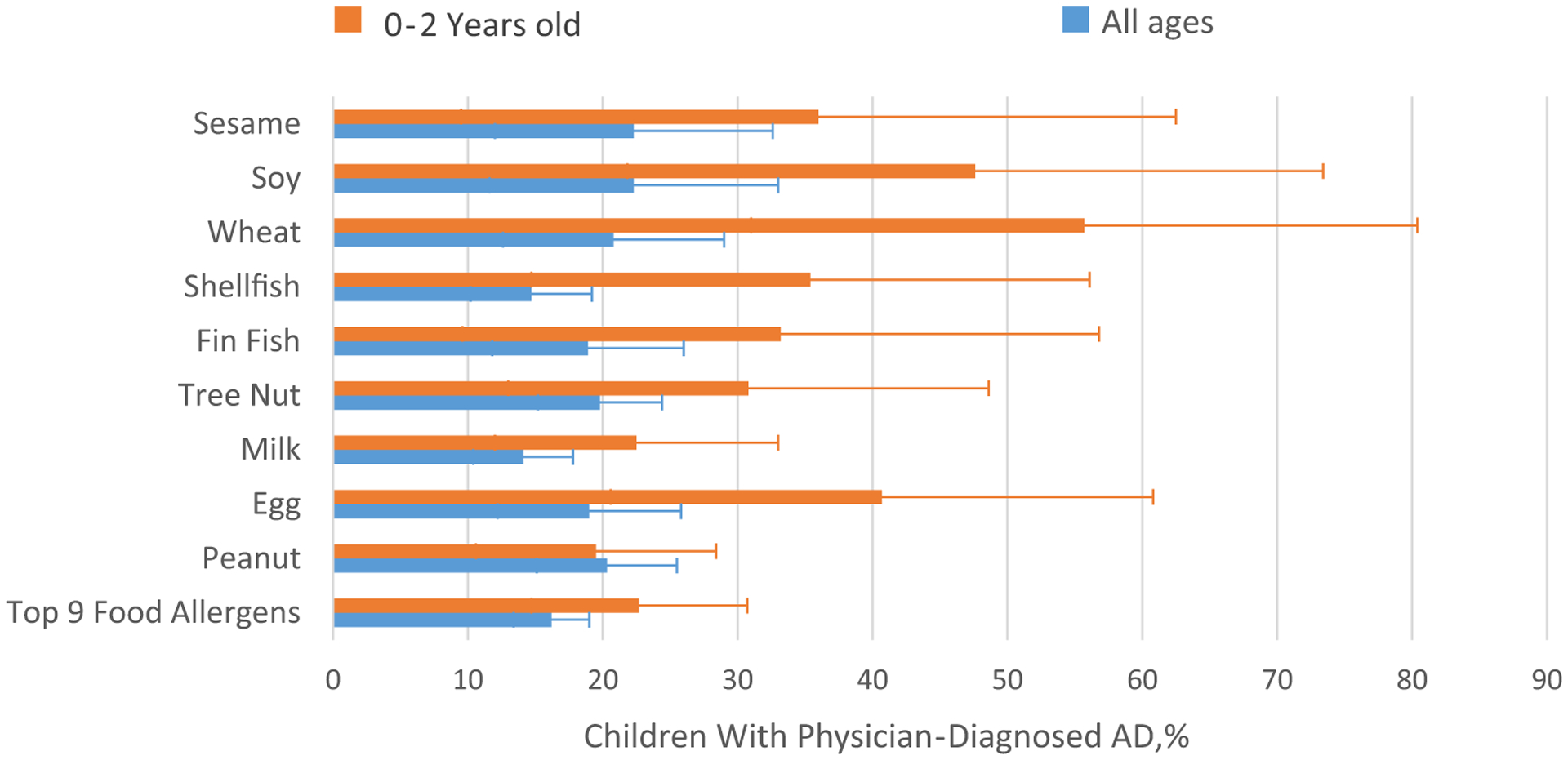

A total of 53,575 US households were surveyed, and parent-proxy data were collected for 38,408 children (0–17 years of age). There were no associations among race, sex, household income, or country of origin when evaluating FA and/or AD status (eTable 1). The overall estimated prevalence of children with convincing FA was 7.6%. The physician-diagnosed AD prevalence in our sample was 5.9%. This finding is consistent with a previous population-based survey that reported a prevalence of 6.8% for physician-diagnosed eczematous conditions.4 AD prevalence among children with convincing FA was 16.2% (95% CI, 13.4%−19.3%) in all ages and 22.7% (95% CI, 14.7%−33.4%) in young children (0–2 years of age) specifically (Fig. 1). AD prevalence among children with physician-diagnosed FA was 18.9% (95% CI, 15.4%−23.0%) in all ages and 29.2 (95% CI, 18.7%−42.5%) in young children.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of atopic dermatitis (AD) among children with food allergy.

Although the most common food allergens among children with FA are peanut, milk, and tree nuts,1 AD prevalence among all children with FA was highest for sesame (22.3%; 95% CI, 12.0%−37.5%), soy (22.3%; 95% CI, 11.6%−38.6%), wheat (20.8%; 95% CI, 12.6%−32.4%), peanut (20.3%; 95% CI, 15.1%−26.8%), tree nut (19.8%; 95% CI,15.2%−25.5%), and egg (19.0%; 95% CI, 12.2%−28.2%). Among young children (0–2 years of age), AD was most common in children with wheat (55.7%; 95% CI, 31.0%−77.8%), soy (47.6%; 95% CI, 21.8%−74.7%), and egg (40.7%; 95% CI, 20.6%−64.4%) allergies. AD was found in19.5% (95% CI, 10.6%−33.3%) of children 0 to 2 years of age with peanut allergy.

We also found that other atopic disorders and a parental history of AD were common in children with FA and AD. Rates of asthma were higher among those with both AD and FA compared with just FA alone (43.8% vs 30.6%, P = .008) or AD alone (43.8% vs19.4%, P < .001). Similar patterns were also seen for allergic rhinitis:44.8% of those with both AD and FA have allergic rhinitis compared with 27.9% for FA alone (P < .001) and 29.6% for AD alone (P < .001). Rates of parental history of atopy were also highest among children with both AD and FA at 57.8% followed by children with AD alone(49.7%) and FA alone (23.1%, P < .001). Unlike child AD, reports of parental AD did not require physician diagnosis because parental diagnosis history was not assessed.

This study provides up-to-date information regarding the important association between AD and FA in a nationally representative sample of children. Overall, 16.2% of children with FA (and22.7% of children aged 0–2 years) had physician-diagnosed AD. Although the prevalence of AD was consistently higher in young children compared with older children with FA, it was highest for those with wheat, soy, and egg allergies. Although the significance of egg allergy as a risk factor for peanut allergy is well documented, the associations between wheat and soy allergies and AD have not been previously documented. In addition, many children with FA in this study did not have AD. Thus, it may be important to consider whether primary FA prevention efforts should be evaluated in all infants, not just those with AD.

There are limitations to our study. This was a parent-proxy response survey; thus, no clinical or laboratory records were used, and bias using self-report data is a concern. However, survey-based approaches can capture patients with FA who may not receive formal evaluations or diagnoses and stringent criteria were established, and FAs that were not consistent with IgE-mediated FA were excluded. In addition, although our prevalence rates are similar to previous studies that measured physician-diagnosed eczematous disorders, they are lower than overall estimates of AD in the pediatric population.5 Thus, it is likely that by requiring a physician diagnosis, we are underreporting overall AD prevalence. This may also indicate that our study findings are more representative of children with moderate to severe AD because families are more likely to seek physician diagnosis and prescription ointments in these cases.

Improving our understanding of AD as a risk factor for FA development suggests that early diagnosis and initiation of treatment for AD in young infants may be critically important, especially with recent reports that AD rates continue to increase.6 Past studies have reported that infants with a diagnosis of AD before 6 months of age and infants with skin barrier dysfunction with or without overt AD are at higher risk for FA development.3,7 The landmark Learning Early about Peanut Allergy (LEAP) study focused on infants with severe AD (and/or egg allergy), finding a 81% decreased risk of peanut allergy development if peanut-containing foods were consumed in the first year of life.8 Currently in the United States, it is recommended that all infants with AD or egg allergy be evaluated for early introduction of peanut-containing foods between 4 and 6 months of age.9 These guidelines have the potential to significantly decrease peanut allergy development; however, timely diagnosis and assessment of AD are critical to implementing the early introduction recommendations. Furthermore, similar to the HealthNuts population study,10 findings from our survey highlight the significant proportion of children with FA without a history of physician-diagnosed AD. Although skin barrier dysfunction is an evidence-based causal pathway for the development of FA, future research should examine risk associated with more mild forms and timing of skin barrier dysfunction as possible targets to improve primary prevention efforts.

Supplementary Material

Funding Source:

This study was funded by R21AI135702 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (principal investigator: Dr Gupta).

Disclosures: Mr Warren is a coinvestigator on National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease grant R21AI135702. Dr Bilaver has received research support from grant R01 ID AI130348 from the National Institutes of Health, Rho Inc, BEFORE Brands, Thermo Fisher Scientific, and the National Confectioners Association and is an assistant professor of pediatrics employed by Northwestern University. Dr Mancini has served on the scientific advisory boards for Pfizer with honorarium (outside submitted work). Dr Gupta has received grant funding from the National Institutes of Health, Stanford University, Allergy and Asthma Network, Food Allergy Research & Education, Rho Inc, Northwestern University Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute, Thermo Fisher, United Health Group, National Confectioners Association, and Aimmune Therapeutics. She serves as medical consultant/adviser for the following companies (in the past 3 years): DBV, Aimmune, Before Brands, Pfizer, Mylan, Kaleo Inc. No other disclosures were reported.

Footnotes

Supplementary Data

Supplementary data related to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anai.2019.03.019.

References

- 1.Gupta RS, Warren CM, Smith BM, et al. The public health impact of parent-reported childhood food allergies in the United States. Pediatrics. 2018; 142(6):e20181235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martin PE, Eckert JK, Koplin JJ, et al. Which infants with eczema are at risk of food allergy? results from a population-based cohort. Clin Exp Allergy. 2015; 45(1):255–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lack G Update on risk factors for food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012; 129(5):1187–1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hanifin JM, Reed ML, Eczema Prevalence Impact Working Group. A population-based survey of eczema prevalence in the United States. Dermatitis. 2007;18(2): 82–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Silverberg JI. Public health burden and epidemiology of atopic dermatitis. Dermatol Clin. 2017;35(3):283–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mohn CH, Blix HS, Halvorsen JA, Nafstad P, Valberg M, Lagerløv P. Incidence trends of atopic dermatitis in infancy and early childhood in a nationwide prescriptionregistry study in Norway. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(7):e184145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kelleher MM, Dunn-Galvin A, Gray C, et al. Skin barrier impairment at birth predicts food allergy at 2 years of age. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137(4): 1111–1116. e1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Du Toit G, Roberts G, Sayre PH, et al. Randomized trial of peanut consumption in infants at risk for peanut allergy. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(9):803–813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Togias A, Cooper SF, Acebal ML, et al. Addendum guidelines for the prevention of peanut allergy in the United States: report of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases-sponsored expert panel. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017; 139(1):29–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koplin JJ, Peters RL, Dharmage SC, et al. Understanding the feasibility and implications of implementing early peanut introduction for prevention of peanut allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;138(4):1131–1141. e1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.