Abstract

COVID-19 has been associated with a variety of cardiac manifestations. Myocarditis and pericarditis have been reported as one of the many cardiac manifestations in association with COVID-19. We describe below three cases of myocarditis, pericarditis with associated pericardial effusion and myopericarditis, respectively, in the setting of COVID-19. Although these entities may occur in isolation, they often occur in association to varying degrees. It could either be the initial diagnosis at the time of presentation or it could occur later in the course of COVID-19 infection. Pericarditis may occasionally be associated with significant pericardial effusion and tamponade requiring therapeutic pericardiocentesis. The assessment of pericardial effusion has been found to be exudative and is usually negative for SARS-CoV-2. Treatment of pericarditis with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, colchicine, and corticosteroids has proven to be safe in COVID-19. Myocarditis may present with severe left ventricular systolic dysfunction and cardiogenic shock requiring inotropes and mechanical circulatory support.

Keywords: COVID-19, cytokine storm, myocarditis, myopericarditis, pericarditis, SARS-CoV-2

INTRODUCTION

COVID-19 is a global pandemic caused by SARS-CoV-2. It causes pulmonary and extra pulmonary manifestations. Among extra pulmonary manifestations, cardiac involvement is one of the most frequent and serious. Myocarditis and pericarditis are among cardiac manifestations of COVID-19. They can occur in the absence of pulmonary involvement. Diagnosis of these conditions can sometimes be challenging and appropriate treatment will improve the outcome.

CASE PRESENTATIONS

Case 1

A 19-year-old male patient who presented to the emergency department on May 21, 2020 with a 7-day history of fever, generalized weakness, cough, and shortness of breath. He has no significant comorbid conditions and gives no history of recent travel or contact with a sick patient. On examination, he was ill-looking and in respiratory distress with tachypnea (respiratory rate 45 breaths/min), tachycardia (heart rate 126 beats/min), hypotension (blood pressure [BP] of 76/44 mmHg), temperature of 38.3°C, and oxygen saturation of 92% on room air. There was no lower limb edema, and his extremities were warm. Cardiovascular examination revealed no significant murmurs with no signs of heart failure. There was decreased air entry bilaterally, and abdominal examination was unremarkable.

His laboratory investigations are detailed in Table 1. He had leucocytosis with lymphopenia and significantly elevated inflammatory markers, interleukin-6 (IL-6) and D-dimer levels. Urea and creatinine were elevated as was high-sensitive troponin T.

Table 1.

Laboratory investigations

| On admission | Peak illness | At discharge | |

|---|---|---|---|

| WBC (4.0-10.0×103/uL) | 19.4 | 36.9 | 5.9 |

| Lymphocyte count | 0.6 | 2.8 | 2.78 |

| Hb (g/dL) | 10.0 | 8.9 | 10.5 |

| Platelets (150-400×103/uL) | 200 | 125 | 416 |

| D-Dimer (<0.44 mg/L) | 4.97 | 16.44 | 0.86 |

| Fibrinogen (<4.1 g/L) | 8.68 | 9.00 | 2.5 |

| LDH (135-225 U/L) | 273 | 820 | 412 |

| CRP (<5 mg/L) | 323 | 340 | 9 |

| Procalcitonin (<0.5 ng/mL) | 18.70 | >100 | 3.14 |

| IL-6 (<7 pg/mL) | 678 | 678 | <2 |

| Ferritin (38-270 ug/L) | 822 | 11,719 | 5278 |

| Trop T (<15 ng/L) | 256 | 398 | 40 |

| Lactic acid (0.5-2.2 mmol/L) | 2.6 | 2.6 | 1.3 |

| Urea (2.8-8.1 mmol/L) | 27.0 | 32.4 | 52 |

| Creatinine (62-106 umol/L) | 344 | 335 | 60 |

| ALT (<40 U/L) | 34 | 873 | 567 |

| AST (<41 U/L) | 25 | 570 | 225 |

WBC: White blood cell, Hb: Hemoglobin, LDH: Lactic dehydrogenase, CRP: C-reactive protein, IL: Interleukin, ALT: Alanine aminotransferase, AST: Aspartate aminotransferase

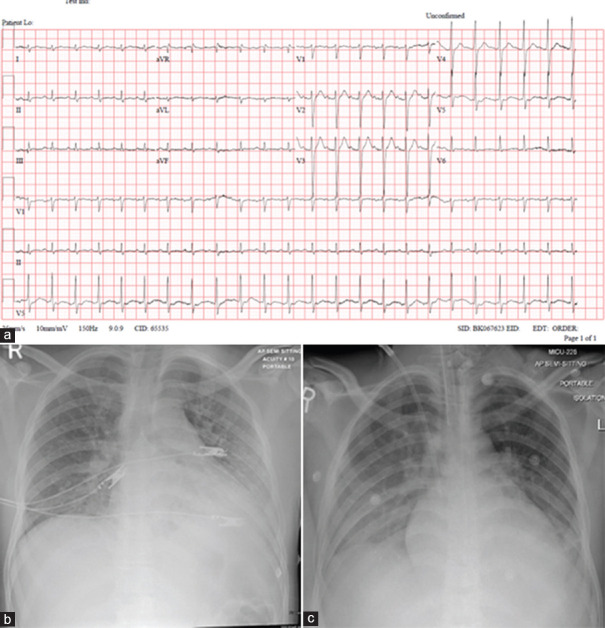

Electrocardiogram (ECG) on admission showed sinus tachycardia at a rate of 150 beats per min [ECG Figure 1a]. At presentation, chest X-ray [Figure 1b] showed bilateral congestive changes and infiltrates in the left lower zone.

Figure 1.

(a) Electrocardiogram at presentation. (b) Chest X-ray upon presentation. (c) Chest X-ray on May 27, 2020 (day 5)

He was admitted to the medical intensive care unit with an initial diagnosis of septic shock. He received intravenous (IV) fluid boluses, vasopressors, and IV antibiotics after septic work up screening. He was put on a nonrebreather mask with 10 L/min of oxygen but was subsequently intubated and ventilated because of increasing respiratory distress. After a positive result of the nasopharyngeal swab for COVID-19, ID team was consulted, and he was started on hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin as per local hospital guidelines. Blood cultures showed no growth. Repeat chest X-ray on day 5 [Figure 1c]. The patient continued to have spikes of fever with hypotension requiring increased hemodynamic support with IV vasopressors (noradrenaline and vasopressin).

Echocardiogram showed a normal left ventricle size with severe global hypokinesia and severely reduced LV systolic function (calculated ejection fraction [EF] of 24%), and there was mild-to-moderate mitral regurgitation (MR). Right ventricular (RV) function was also severely reduced, with moderate-to-severe tricuspid regurgitation (TR) and mildly increased pulmonary artery pressure (40 mm Hg). There was no pericardial effusion.

Cardiology team was consulted, and a diagnosis of COVID-19 myocarditis was established in the setting of severe COVID-19 pneumonia associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome, shock, and acute kidney injury. Significantly elevated inflammatory markers and IL-6 levels were in keeping with a diagnosis of the cytokine storm. He was treated with tocilizumab, methylprednisolone, and IV immunoglobulin. This was followed by improvement in hemodynamic parameters and reduction in vasopressor support, which was discontinued 3 days after the administration of tocilizumab.

Renal function also improved and normalized. The patient was successfully extubated on day 9. Repeat COVID polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test on day 10 was negative.

Repeat echocardiography on day 13 showed normalization of both the left and RV systolic function with left ventricular ejection fraction of 62% and no wall motion abnormalities. There was a trivial MR, no TR, and no pericardial effusion.

He was discharged on day 16 with a heart rate of 80 beats/min, BP of 108/70 mmHg, temperature of 37.1°C and SpO2 of 100% on room air. His total white cell count, lymphocyte count, inflammatory markers, D-dimer, and renal function had normalized prior to discharge. His discharge medications included ramipril, bisoprolol, and ivabradine.

Case 2

This 42-year-old male patient presented on August 2, 2020 with a 1-week history of fever, cough, shortness of breath, and pleuritic chest pain. He gave no history of recent travel or sick contact. On examination, he looked comfortable, temperature of 37°C, heart rate of 102 beats/min, BP 113/74 mmHg, respiratory rate 19 breath/min, and oxygen saturation of 99% on room air. The chest examination was normal and cardiovascular examination revealed distant heart sounds.

He had a history of positive PCR for COVID-19 (as a part of screening in the workplace) 6 weeks prior to admission requiring no therapy.

Labs showed white blood cell 8.1 × 103/uL (absolute neutrophil count 5.8 × 103 (2.0–7.8), lymphocyte count 1.5 × 103 (1.0–3.0), hemoglobin 10.8 g/dL, platelets 338 × 103/uL, C-reactive protein (CRP) 100.2 mg/L (0.0–5.0), procalcitonin < 0.02 ng/mL, D-dimer 6.14 mg/L fibrinogen equivalent unit (0.00–0.49), lactic dehydrogenase (LDH) 279 U/L (135–225), ferritin 657 ug/L (30–490), high-sensitive Troponin T < 3, and normal kidney and liver functions.

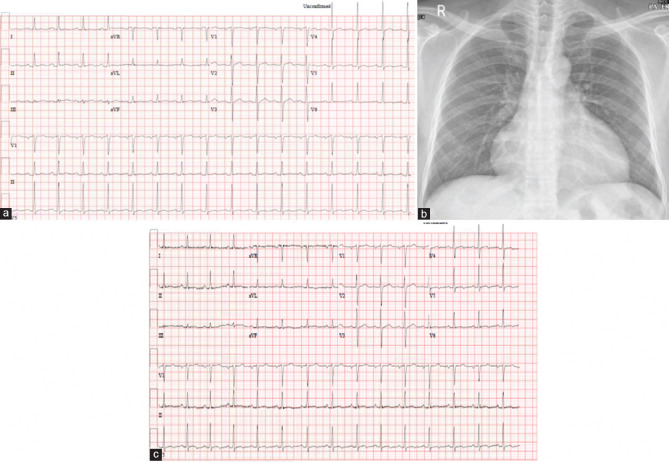

ECG showed normal sinus rhythm. There was mild ST-segment elevation in inferior leads associated with discrete PR depression as well as in lead V6. Minimal PR elevation was noted in Lead aVR [Figure 2a].

Figure 2.

(a) Electrocardiogram on admission. (b) Chest X-ray on admission. (c) Electrocardiogram on discharge

Chest X-ray showed enlarged cardiac silhouette [Figure 2b].

Because of symptoms of shortness of breath and raised D-Dimer, a computed tomography (CT) pulmonary angiogram was performed, which did not reveal any evidence of pulmonary embolism. However, it showed the presence of a large pericardial effusion. Transthoracic echocardiogram confirmed the presence of a large circumferential pericardial effusion (without any echocardiographic evidence of cardiac tamponade). Ventricular functions were normal, with no valvular dysfunction.

Repeated PCR was positive for COVID-19 with a CT value of 36.

He was diagnosed with a case of large pericardial effusion in the setting of a recent COVID-9 infection. The patient was admitted to the hospital under cardiology service and treated conservatively withibuprofen 600 mg TID and colchicine 0.5 mg BID. Serial echocardiograms did not show further increase in the pericardial effusion or the development of pericardial tamponade. He remained hemodynamically stable throughout his hospital stay and was discharged 10 days later on ibuprofen and colchicine. ECG on discharge [Figure 2c].

Case 3

A 38-year-old male diabetic patient presented on July 1, 2020, with a proven moderate COVID-19 pneumonia for which he was treated with antibiotics and antiviral medications as per the hospital guidelines. He made an uncomplicated recovery and was discharged 3 weeks later. He presented to the emergency department a few hours later on the same day of discharge (July 23, 2020) with atypical pricking chest pain, not related to breathing, exertion, or posture.

Clinically, he was apyrexial and not distressed. His vital signs were unremarkable with a heart rate of 102 beats/min, BP 121/93 mmHg, and SpO298% on room air. Cardiovascular examination was unremarkable, and his chest was clear to auscultation.

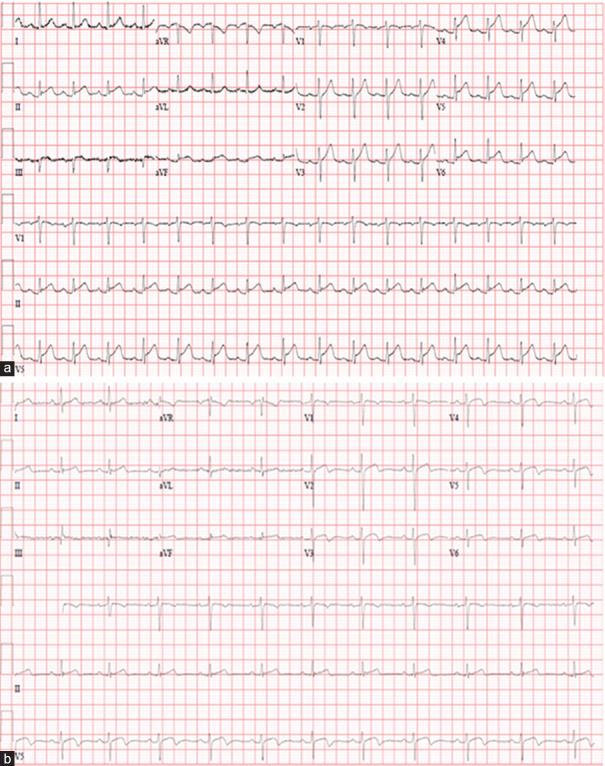

ECG on admission showed sinus rhythm with diffuse concave ST-segment elevation in multiple leads. PR depression was also noted in inferolateral leads and PR elevation in aVR [Figure 3a]. Chest X-ray on admission showed bilateral infiltrates which were less prominent compared to his previous X-rays when he was admitted with COVID-19 pneumonia.

Figure 3.

(a) Electrocardiogram on admission. (b) Electrocardiogram on discharge

Laboratory investigations revealed an elevated total white cell count of 15,200 with a normal lymphocyte count and a normal CRP level at 3 mg/L (N <5). Renal functions were normal. Serial Troponin T levels were elevated with a peak of 1264 ng/L (normal <15).

Transthoracic echocardiogram showed a normal left ventricular systolic function with an EF of 53%. Apex was noted to be akinetic while other segments were moving normally. There was no pericardial effusion.

Repeat ECGs on the day of presentation did not show any serial changes.

He was diagnosed with myopericarditis in the setting of recent COVID-19 infection and treated with aspirin 800 mg three times a day and colchicine 0.5 mg twice a day.

Serial ECGs during his hospital stay showed resolution of ST-segment elevation and development of T wave abnormalities in the anterior leads. Coronary angiogram did not show obstructive coronary artery disease.

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging showed normal biventricular volumes and function. There was akinesia of the apico-lateral, apico-inferior walls and apical cap, myocardial hyperemia, and myocardial scar/necrosis consistent with a diagnosis of myocarditis.

He responded well to treatment and was chest pain-free upon discharge. ECG on discharge showed a resolution of ST-elevation [Figure 3b]. He was discharged on tapering doses of aspirin, colchicine, and esomeprazole.

COVID-19 AND MYOCARDITIS/PERICARDITIS

The exact incidence of myocardial involvement or myocarditis among hospitalized COVID-19 patients is unknown. Myocardial injury is observed in up to 7%–17% of patients with COVID-19.[1] In a cohort of 416 patients at the Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University, 82 patients (19.7%) had the cardiac injury. Mortality among the myocardial injury group was significantly higher than those without (51.2% vs. 4.5%; P < 0.001).[2]

Review of the reported COVID-19 myocarditis cases has shown that LV systolic dysfunction is temporary and improves rapidly with treatment.[3,4]

Endomyocardial biopsy is recommended in certain clinical situations to aid in the diagnosis of myocarditis.[5] Xu et al. were the first to report interstitial mononuclear inflammatory infiltrates in a postmortem biopsy of a COVID-19 patient.[6] In a histopathologic study involving three patients, all patients had small amounts of lymphocyte, monocyte, and neutrophil infiltration in heart tissue, but PCR did not detect COVID-19 in myocardial tissue.[7]

A case reported by Sala et al. showed diffuse T-lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrates (CD3+ >7/mm2) with interstitial edema, but no COVID-19 genome in the myocardium.[8] Furthermore, Tavazzi et al. showed viral particles typical of coronavirus involving interstitial macrophages and their surroundings, but not within the cardiac myocytes.[9]

Pericarditis with pericardial effusion and tamponade associated with COVID-19 can be associated with pneumonia or without pneumonia. There have been several case reports of pericarditis with large pericardial effusion and tamponade requiring therapeutic pericardiocentesis.[10,11,12,13,14] Analysis of pericardial effusion in all patients were exudative with high LDH and albumin and high fluid LDH: serum LDH ratio > 0.6.[10,11,12,13] In two patients, the effusion was bloody and exudative.[12,13] Pericardial fluid was not tested for SARS-CoV-2 as the facility was not available in treating hospital[11,12] and was negative for SARS-CoV-2 in two patients.[13,14]

In the setting of COVID-19 pericarditis/myopericarditis, management is similar to what is recommended for viral pericarditis (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs] and Colchicine). A recent study reviewing the safety and potentiality of anti-inflammatory therapies for pericardial diseases in COVID-19 considered their use safe in this setting.[15]

In cases of myocarditis, treatment of heart failure, arrhythmias, and mechanical circulatory support for cardiogenic shock refractory to medical therapy is required.[16] COVID-19 related fulminant myocarditis, should be treated as cardiogenic shock,[17] including administration of inotropes and/or vasopressors, mechanical ventilation, and mechanical circulatory support such as extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, ventricular assist device, or intra-aortic balloon pump.

Tocilizumab, an IL-6 receptor blocker, licensed for cytokine release syndrome, has been approved for use in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia and elevated IL-6.[18] All patients with severe COVID-19 should be screened for hyperinflammation using laboratory trends (e.g., increasing ferritin, decreasing platelet counts, or erythrocyte sedimentation rate) and the HScore to identify the subgroup of patients for whom immunosuppression could improve mortality. Therapeutic options include steroids, intravenous immunoglobulin, selective cytokine blockade (e.g., anakinra or tocilizumab), and Janus kinase inhibition.[19]

CONCLUSION

During the current COVID-19 pandemic, patients presenting with chest pain and ST-segment elevation should be carefully evaluated for features of pericarditis and myocarditis other than acute coronary syndrome and treated accordingly.

Myocarditis/pericarditis or myopericarditis associated with COVID-19 may occur with or without pneumonia. Pericardial effusion causing tamponade may occur in the setting of pericarditis and requires therapeutic pericardiocentesis. NSAIDs, colchicine, and corticosteroids are safe to use in pericarditis/myopericarditis associated with COVID-19.

Myocarditis can be associated with LV systolic dysfunction and cardiogenic shock, requiring inotropic support or mechanical circulatory support. Patients should be evaluated for cytokine storm and when indicated, treated with tocilizumab (IL-6 blocker).

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the legal guardian has given his consent for images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The guardian understands that names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Guzik TJ, Mohiddin SA, Dimarco A, Patel V, Savvatis K, Marelli-Berg FM, et al. COVID-19 and the cardiovascular system: implications for risk assessment, diagnosis, and treatment options. Cardiovasc Res. 2020;116:1666–87. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvaa106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shi S, Qin M, Shen B, Cai Y, Liu T, Yang F, et al. Association of cardiac injury with mortality in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China? JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5:802–10. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.0950. doi:10.1001/jamacardio.2020.0950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Inciardi RM, Lupi L, Zaccone G, Italia L, Raffo M, Tomasoni D, et al. Cardiac Involvement in a Patient With Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)? JAMA Cardiol. 5:819–24. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1096. doi:101001/jamacardio20201096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fried JA, Ramasubbu K, Bhatt R, Topkara VK, Clerkin KJ, Horn E, et al. The variety of cardiovascular presentations of COVID-19. Circulation. 2020;141:1930–6. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.047164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fairweather D, Cooper LT, Blauwet LA. Sex and gender differences in myocarditis and dilated cardiomyopathy. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2013;38:7–46. doi: 10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2012.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xu Z, Shi L, Wang Y, Zhang J, Huang L, Zhang C, et al. Pathological findings of COVID-19 associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:420–2. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30076-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yao XH, Li TY, He ZC, Ping YF, Liu HW, Yu SC, et al. A pathological report of three COVID-19 cases by minimal invasive autopsies. Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi. 2020;49:411–7. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112151-20200312-00193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sala S, Peretto G, Gramegna M, Palmisano A, Villatore A, Vignale D, et al. Acute myocarditis presenting as a reverse Tako-Tsubo syndrome in a patient with SARS-CoV-2 respiratory infection. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:1861–2. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tavazzi G, Pellegrini C, Maurelli M, Belliato M, Sciutti F, Bottazzi A, et al. Myocardial localization of coronavirus in COVID-19 cardiogenic shock. Eur J Heart Fail. 2020;22:911–57. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Allam HH, Kinsara AJ, Tuaima T, Alfakih S. Pericardial Fluid in a COVID-19 Patient: Is it exudate or transudate? Eur J Case Rep Intern Med. 2020;7:001703. doi: 10.12890/2020_001703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Asif T, Kassab K, Iskander F, Alyousef T. Acute Pericarditis and Cardiac Tamponade in a Patient with COVID-19: A Therapeutic Challenge. Eur J Case Rep Intern Med. 2020;7:001701. doi: 10.12890/2020_001701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dabbagh MF, Aurora L, D'Souza P, Weinmann AJ, Bhargava P, Basir MB. Cardiac Tamponade Secondary to COVID-19. JACC Case Rep. 2020;2:1326–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jaccas.2020.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fox K, Prokup JA, Butson K, Jordan K. Acute effusive pericarditis: A late complication of COVID-19. Cureus. 2020;12:e9074. doi: 10.7759/cureus.9074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Derveni V, Kaniaris E, Toumpanakis D, Potamianou E, Ioannidou I, Theodoulou D, et al. Acute life-threatening cardiac tamponade in a mechanically ventilated patient with COVID-19 pneumonia. IDCases. 2020;21:e00898. doi: 10.1016/j.idcr.2020.e00898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Imazio M, Brucato A, Lazaros G, Andreis A, Scarsi M, Klein A, et al. Anti-inflammatory therapies for pericardial diseases in the COVID-19 pandemic: Safety and potentiality. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown) 2020;21:625–9. doi: 10.2459/JCM.0000000000001059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McMurray JJ, Adamopoulos S, Anker SD, Auricchio A, Boehm M, Dickstein K, et al. ESC committee for practice guidelines ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012: The task force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012 of the European Society of Cardiology.Developed in collaboration with the Heart Failure Association of the ESC (HFA) Eur Heart J. 2012;33:1787–847. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kociol RD, Cooper LT, Fang JC, Moslehi JJ, Pang PS, Sabe MA, et al. Recognition and initial management of fulminant myocarditis: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;141:e69–92. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chinese Clinical Trial Registry. Multicenter, Randomized Controlled Trial for the Efficacy and Safety of Tocilizumab in the Treatment of New Coronavirus Pneumonia (COVID-19) 2020 Feb 13; [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mehta P, McAuley DF, Brown M, Sanchez E, Tattersall RS, Manson JJ, et al. COVID-19: Consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. Lancet. 2020;395:1033–4. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30628-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]