Abstract

Little is known about how well the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ five-star rating system for the overall quality of Medicare Advantage (MA) contracts captures quality of care. Leveraging contract consolidation as a natural experiment to study the association between outcomes and insurer-initiated enrollee shifts to plans with higher-rated contracts, we found that enrollees experiencing a one-star MA rating increase were 20.8 percent less likely to voluntarily leave their plan to enroll in another plan or traditional Medicare. When hospitalized, they were 3.4 percent more likely to use a higher-quality hospital and 2.6 percent less likely to be readmitted within ninety days. Our findings suggest that MA star ratings may capture key domains of an MA plan’s quality; however, the differences in outcomes that they capture might not all be clinically meaningful.

More than one-third of all Medicare enrollees are enrolled in Medicare Advantage (MA).1,2 In Medicare Advantage, private insurers receive capitated payments to cover their enrollees’ health care needs. Capitated payment models may provide incentives to provide more efficient health care, yet they may also present perverse incentives for MA plans to restrict access to care. To address this concern, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) monitors the quality of MA plans using a star rating system. However, little is known about the adequacy of these ratings in actually capturing the different aspects of care quality and the outcomes that enrollees experience.

Star ratings have proliferated in health care to guide consumers in their selection of providers or health plans and to promote transparent and accessible reporting of performance.3 The MA star ratings, first introduced in 2008, range from two to five stars in 0.5-star increments and are calculated on the basis of approximately thirty-five measures of quality and patient experience. In 2012 CMS initiated bonus payments to MA contracts with higher ratings. Contracts that are rated four or more stars are eligible to receive a 5 percent bonus to their capitated payments for each enrollee in the contract, as well as higher rebate payments that may be reinvested into supplemental benefits. In 2019, 72 percent of enrollee-weighed contracts were rated four stars or higher and were therefore eligible for a bonus (9 percent were rated 5 stars, 21 percent 4.5 stars, and 42 percent 4 stars).2

Higher star ratings have been found to be associated with increased enrollment,4-6 better access to higher-quality nursing homes and hospitals,7,8 and lower disenrollment among patients with complex health care needs.9,10 However, many of the measures in the star ratings are correlated with sociodemographic characteristics and geography. Therefore, the rating of a contract may reflect the composition of its enrollees rather than the quality of its care.11-13

Concern about what the differences in contract star ratings amount to in terms of quality of enrollee care has also been fueled by the engagement of MA insurers in a practice known as contract consolidation. Until recently, MA insurers could use consolidation to increase their eligibility to receive bonuses by concentrating MA enrollees in higher-rated, bonus-eligible contracts. At the end of a plan year, as long as the cost-sharing structure does not vary substantially, consolidation allows an insurer to automatically move all enrollees—without action on the enrollees’ part—from one contract into another. The original contract no longer exists as of the following plan year. Historically, when the shift was from a contract rated lower than four stars into a contract rated four stars or higher, that process increased insurers’ eligibility for bonus payments. Although consolidation requires plan cost sharing to remain the same, the benefits, provider networks, and other outreach efforts by the contract may change (for example, availability of call centers and care management programs). As of 2020 CMS changed its regulations to prevent insurers from using consolidations to boost bonus payments. However, more than 3.3 million beneficiaries (11 percent of MA enrollees) were consolidated between 2012 and 2016.14 In online appendix A we present a diagram of the consolidation process.15

In this study we leveraged the natural experiment in which MA insurers dissolved lower-rated contracts and moved all enrollees into higher-rated contracts without the enrollee needing to opt in to the change in enrollment. We used the exogenous change in star ratings to gain insight into the relationship between star ratings and enrollees’ use of higher-quality hospitals and nursing homes, contract switching, and quality of care.

Study Data And Methods

Data Sources

To identify MA enrollment, we used the Medicare Beneficiary Summary File from 2014 to 2016. The file includes variables for beneficiaries’ monthly MA enrollment status, their MA contract, and their demographic characteristics. In the MA program, insurers enter into contracts with CMS to provide services. Contracts are the level at which quality is assessed, and contracts can contain multiple plans that have different cost-sharing designs. We linked each enrollee’s contract from the Medicare Beneficiary Summary File to publicly available MA star ratings and plan characteristics files.

For quality-of-care outcomes, we used the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS), which includes more than twenty quality outcomes reported by MA contracts on their enrollees at the individual level. These individual-level data can be linked to beneficiaries from the Medicare Beneficiary Summary File. To assess the quality of hospitals and skilled nursing facilities to which enrollees are admitted, we used the Medicare Provider Analysis and Review file, which includes hospital records for more than 90 percent of MA enrollees,16-18 and the Minimum Data Set 3.0, which includes records for all nursing home stays. We linked both of these files to data from Hospital Compare and Nursing Home Compare.

Study Population

We included all MA enrollees in 2014 and 2015, including those dually eligible with Medicaid, in this study. We excluded enrollees in national Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly plans, Medicare-Medicaid integrated plans (a plan type available in some states that represents a minority of all dually eligible enrollees), and employer-sponsored plans, as each of these plan types operates differently from most other plans in the MA market.

Instrumental Variable Contract Consolidation

Because market consolidations transferred enrollees from one contract to another without enrollee input and most consolidations were from lower-rated contracts to higher-rated contracts, contract consolidation presents a natural experiment in which enrollees are exposed to higher-rated contracts without actively selecting them. In this study we used prior-year consolidation as an instrumental variable to assess whether exposure to a higher-rated MA contract leads to improved outcomes.

Treatment/Nontreatment Groups

We separated enrollees into two groups according to whether their enrolled contract in 2014 consolidated at the end of 2014 (the treatment group) or not (the control group). We observed these two groups in 2014 (pre period) and 2015 (post period). Because most of the consolidations involve dissolving a lower-rated contract and moving its enrollees to a higher-rated contract, the treatment group experienced an increase in contract star rating in the post period. The assumption of this design is that the only mechanism by which the quality of care for enrollees in consolidated contracts would change after consolidation would be because they were exposed to a higher-rated contract. In other words, the experience of being in a consolidated contract would not lead to a change in the quality of care except through the pathway of being moved to a contract with a higher star rating. Using the consolidation as an instrumental variable allowed us to calculate the association between an increase in star ratings and outcomes as if the assignment of star ratings were random. In appendix A we present a diagram of the consolidation process, and in appendix B we present diagrams of how our control and treatment groups were specified.15

Outcome Variables

The study outcomes were voluntary disenrollment (moving from MA to traditional Medicare) or switching contracts (voluntarily switching between two contracts in the MA program), thirty- and ninety-day readmission rates after a hospitalization, admission to higher- and lower-rated hospitals (defined as hospitals rated four stars or higher and hospitals rated fewer than three stars, respectively), admission to higher- and lower-rated nursing homes (defined as nursing homes rated four stars or higher and nursing homes rated fewer than three stars, respectively), and quality indicators for follow-up after a mental health visit, diabetes eye screening, poor HbA1c control, management of high blood pressure, management of osteoporosis, use of low-value prostate-specific antigen exams, colorectal cancer screening, and breast cancer screening. We also included measures of whether an enrollee had any primary care visit and the number of outpatient visits. Details on the sources of each outcome and how they were calculated are in appendix D.15 It is important to note that although the Nursing Home Compare star ratings have been found to be effective in capturing improvements in nursing home outcomes,19 the Hospital Compare star ratings are relatively new and may perform differently across hospital types.20 Nevertheless, they may still be useful as an aggregate measure of quality. In sensitivity checks, correlations between the measures did not differ between enrollees in consolidated and nonconsolidated contracts, ranging from 0.1 to 0.6.

To flag enrollees who were in a consolidated contract, we used the Medicare Beneficiary Summary File to identify contracts that were terminated between 2014 and 2015 and the subsequent contract for their enrollees. If more than 70 percent of those enrollees moved to the same contract owned by the same parent company as the one that was terminated, we considered it a consolidation.14 All enrollees in a contract in 2014 that consolidated were given the consolidation flag regardless of their enrolled contract in 2015, in an intent-to-treat approach. As a sensitivity check, we compared this consolidation definition with plan crosswalk files released by CMS.

Consolidations can occur either within a given state or nationally, which may have implications for provider networks available to enrollees. If the consolidation is national and the destination contract is based in a different state, an enrollee might be less likely to experience a change in provider network. If the consolidation is within the same state, however, an enrollee might be more likely to experience such a change. To test these possibilities, we performed an additional sensitivity check, limiting the analysis to only contracts that were consolidated to another contract that had overlapping service areas within the same state.

Statistical Analysis

We first described the characteristics of enrollees who were in consolidated contracts between 2014 and 2015 and those who were not. We then fit our primary two-stage least squares instrumental variable models, adjusting for age, sex, race/ethnicity, and dual-eligibility status. In our first stage we estimated the role of consolidations on star ratings, using a dichotomous variable for enrollee consolidation status and a flag for year and their interaction. From this first-stage model, we estimated our second stage on the outcomes. We also included 2014 contract fixed effects in our models to account for differences that may be related to each enrollee’s initial contract (that is, the contract before consolidation occurred).

The instrumental variable approach is valuable, as it allowed us to estimate the effect of star ratings on outcomes. Without a causal identification strategy, it is likely that our estimates would be biased because of selection. The instrumental variable approach is also preferable in this case to difference-in-differences, as the latter would only allow us to estimate the effect of consolidation on outcomes.

A valid instrument must fulfill two criteria. First, the instrument (consolidation) must be strongly associated with the treatment (enrollment in a contract with a higher star rating). We confirmed this association by calculating the F statistic. Second, the instrument should not affect the outcome except through its association with the treatment. There are no established methods to empirically confirm this second criterion. However, the decision for a company to consolidate its contracts may be plausibly independent from the enrollee’s decision to enroll in a higher-rated plan. The contract fixed effects further controlled for initial contract-level heterogeneity. A more complete discussion of the instrumental variable approach we employed is in appendix C.15 All analyses were conducted in Stata 15 and used an α of 0.05.

Limitations

Our study had several limitations. First, although it is likely that consolidation is independent of patient characteristics, this could not be proven definitively. Second, as HEDIS outcome variables are reported by MA contracts themselves, we could not determine whether improvements in an outcome came from an actual improvement in quality or whether certain contracts were better at reporting favorable outcomes to HEDIS. This limitation would not apply to measures of readmission, contract switching, and the quality of nursing homes and hospitals, which we generated directly from administrative data. Third, as consolidation and the assignment of star ratings occur at the contract level, we were unable to disentangle what role individual plans within contracts played for enrollees. Fourth, given that our study has large sample sizes from across the MA program, some results from this study may be statistically significant but less clinically meaningful if the effect sizes are relatively small. We also cannot rule out potential violations to the exclusion restriction. Enrollees are contacted when a consolidation occurs, which may change their behavior and lead to different outcomes. However, the burden of mailings to Medicare patients is already high, and most enrollees remain in the consolidated plan when their previously enrolled contract is ended.

Study Results

Descriptive Results

Our sample included 16,002,968 MA enrollees in 515 contracts, among whom 1,325,632 in 42 contracts were involved in a consolidation. Exhibit 1 presents the demographic characteristics, outcomes, and HEDIS measures of consolidated and nonconsolidated enrollees in 2014 and 2015. Demographic characteristics were largely similar between the two groups. Among those who were consolidated, there was an average 0.7-star increase in star ratings compared with a 0.1-star increase among those who were not consolidated.

EXHIBIT 1.

Medicare Advantage (MA) enrollees’ characteristics, by consolidation status, 2014

| Characteristics | Consolidated | Nonconsolidated |

|---|---|---|

| Enrollees | ||

| Number | 1,325,632 | 16,002,968 |

| Percent | 7.7 | 92.4 |

| Mean MA plan star rating | 3.4 | 3.9 |

| Mean age, years | 72.6 | 71.9 |

| Race/ethnicity (%) | ||

| White | 76.3 | 69.4 |

| Black | 10.5 | 11.4 |

| Other or unknown | 1.5 | 1.6 |

| Asian | 2.8 | 3.5 |

| Hispanic | 8.8 | 13.8 |

| Native American/American Indian | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| Female (%) | 57.5 | 56.4 |

| Dually eligible for Medicaid (%) | 15.4 | 19.3 |

| Basis of Medicare eligibility (%) | ||

| Age | 88.5 | 86.1 |

| Disability | 11.4 | 13.8 |

| End-stage renal disease | 0.02 | 0.03 |

| Disability and renal disease | 0.05 | 0.06 |

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data from the 2014 Master Beneficiary Summary File. NOTE MA plan star ratings range from 2 to 5 stars.

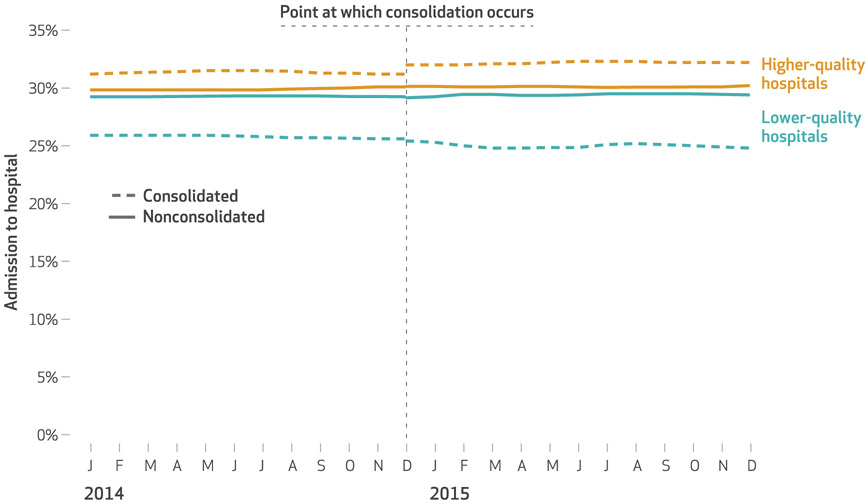

Exhibit 2 compares the hospital admissions patterns for enrollees who were consolidated into higher-rated contracts compared with the patterns for those who were not. For those who were moved to a higher-rated contract, if hospitalized, they were more likely to be admitted to hospitals with a star rating of four or more and less likely to be admitted to hospitals with fewer than three stars. For enrollees who were not in a consolidated plan, there was minimal change in the use of higher- and lower-rated hospitals.

EXHIBIT 2. Monthly trends in admission to higher- and lower-rated hospitals by Medicare Advantage contract consolidation status, 2014-15.

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of 2014 and 2015 Master Beneficiary Summary File and Medicare Provider Analysis and Review files. NOTES The axes represent the percentage of enrollees admitted to hospitals in the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Hospital Compare database, by star rating. Lower-quality hospitals have fewer than three stars. Higher-quality hospitals have four or more stars. The lines are smoothed using a polynomial fit line.

Across all outcomes, consolidations appeared to be a strong instrument, with F-statistics generally higher than 5,000 (well above the established threshold of 10) (appendix F).15,21 Across most first-stage models, consolidation was associated with a 0.6-star increase in the rating of the enrollee’s contract. Complete first-stage regression output and ordinary least squares results are in the supplemental appendix (appendixes G and H).15

Primary Results

In instrumental variable analyses (exhibit 3), a one-star increase in an MA contract’s rating led to a 0.8-percentage-point increase in the likelihood that an enrollee was admitted to a higher-rated hospital (95% confidence interval: 0.3, 1.2), or a 3.4 percent relative increase, and a 0.9-percentage-point lower likelihood of admission to a lower-rated hospital (95% CI: 0.4, 1.4), or a 2.7 percent relative decrease. An increase of one star in the contract rating an enrollee experiences also led to a 2.6 percent relative reduction in ninety-day readmissions and a 20.8 percent relative reduction in the likelihood of voluntarily switching either to traditional Medicare or between MA contracts.

EXHIBIT 3.

Change in disenrollment and contract switching rates, use of higher- and lower-rated hospitals and nursing homes, and readmissions associated with a 1-star increase in Medicare Advantage (MA) contract star rating

| Baseline rate in 2014 (%) |

Change in outcome associated with 1-star increase in star rating (percentage points)a |

Relative change (%) |

No. of observations |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Switching or disenrollment | 13.0 | −2.7**** | −20.8 | 30,104,761 |

| Admission to hospital with 4+ stars | 23.4 | 0.8*** | 3.4 | 4,132,632 |

| Admission to hospital with <3 stars | 33.0 | −0.9*** | −2.7 | 4,132,632 |

| MedPAR 30-day readmissions | 17.0 | −0.3 | −1.8 | 4,132,632 |

| MedPAR 90-day readmissions | 19.5 | −0.5** | −2.6 | 4,132,632 |

| Admission to nursing home with 4+ stars | 42.4 | 1.0** | 2.4 | 1,342,226 |

| Admission to nursing home with <3 stars | 32.3 | −1.1** | −3.4 | 1,342,226 |

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data from the 2014 and 2015 Master Beneficiary Summary Files and Medicare Provider Analysis and Review (MedPAR) files. NOTES Admission to nursing home is derived from Minimum Data Set records. Admission to hospital and hospital readmission rates are derived from the MedPAR files. We consider a hospital or a nursing home to be higher quality if rated four or more stars on Hospital Compare or Nursing Home Compare, respectively, and lower quality if rated below three stars. The readmission rates are unadjusted unplanned readmissions using the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project unplanned readmissions algorithm. An enrollee is considered to have disenrolled if, at the start of the following year, they are still alive but are enrolled in traditional Medicare. An enrollee was considered to have switched plans if they moved from one MA contract to another voluntarily. Disenrollment or switching was considered as a single outcome in this analysis. All regression values are percentage-point differences associated with a one-star rating increase. The baseline column is the mean outcomes among enrollees who did not consolidate. The number of observations changes because of the availability of the outcome variable.

Instrumental variable approach.

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001

Changes In Quality Metrics

Exhibit 4 presents the instrumental variable results for HEDIS quality measures. There was a positive relationship between a one-star increase in contract rating and colorectal cancer screening (3.6-percentage-point increase; 95% CI: 0.6, 2.2), breast cancer screening (1.8-percentage-point increase; 95% CI: 1.3, 2.2), management of high blood pressure (a 5.3-percentage-point increase; 95% CI: 1.7, 8.9), and a reduction in low-value prostate-specific antigen exams (a 6.6-percentage-point reduction, 95% CI: 6.1, 7.0). Using HEDIS data, we also found a 0.5-percentage-point increase in the likelihood an enrollee had any primary care visit within a year (95% CI: 0.4, 0.6) and a 0.8-visit increase in mean annual outpatient visits per person (a 9.5 percent relative increase; 95% CI: 0.8, 0.8).

EXHIBIT 4.

Change in Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) quality measures associated with a 1-star increase in Medicare Advantage (MA) contract star ratings

| HEDIS quality measures | Baseline rate in 2014 |

Change in outcome associated with 1-star increase in star rating (percentage points)a |

Relative change (%) |

No. of observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mental health follow-up visit | 53.4% | 2.4 | 4.5 | 107,369 |

| Colorectal cancer screening | 65.1% | 3.6** | 5.5 | 1,079,010 |

| Breast cancer screening | 72.3% | 1.8*** | 2.5 | 5,741,351 |

| Management of osteoporosis | 39.8% | −0.6 | −1.5 | 190,892 |

| Management of high blood pressure | 64.3% | 5.3*** | 9.8 | 261,479 |

| Poor HBa1c control | 28.1% | 1.3 | 4.6 | 566,025 |

| Diabetes eye screenings | 69.1% | −2.9 | −4.2 | 558,198 |

| Use of low-value PSA exam | 37.1% | −6.6*** | −17.8 | 6,128,042 |

| Any primary care visit | 86.1% | 0.5*** | 0.6 | 28,487,694 |

| Mean no. of outpatient visits | 8.4 | 0.8** | 9.5 | 33,454,558 |

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data from the 2014 and 2015 Master Beneficiary Summary Files and HEDIS files. NOTES All variables come from HEDIS data. All regression values are percentage-point differences associated with a 1-star rating increase. The number of observations changes across HEDIS measures because of different criteria for inclusion in each metric. PSA is prostate specific antigen.

Instrumental variable approach.

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

Sensitivity Analyses

Sensitivity analyses that used a binary indicator of star ratings rather than a continuous measure, that restricted the analysis to parent companies that had two or more contracts nationally, and that restricted the control group to similarly rated contracts all yielded similar results. We found that there was no significant effect of an increased star rating on any hospitalizations within a year, which indicates that differences in observed hospital ratings were not related to differing rates of hospitalizations. Approximately one-third of the consolidations were to MA contracts that had a primary service area within the same state. When we restricted our analysis to these consolidations, the associations between star rating and quality of admitted hospital and nursing home were larger than in the full sample (appendix I),15 as would be expected if in-state consolidations gave beneficiaries the opportunity to participate in a different, higher-quality provider network. For most other measures, however, the in-state results were not significant. We also found similar results when restricting our analysis to those dually eligible for Medicaid, who may have greater health needs.

Discussion

In this study on the relationship between MA star ratings and outcomes, we found that enrollees in MA contracts with higher star ratings had a significant 3.4 percent increase in the use of higher-rated hospitals, a significant 2.6 percent reduction in ninety-day readmissions, a significant 20.8 percent decrease in disenrollment to traditional Medicare and switching contracts within MA, and several statistically significant yet small-in-magnitude improvements across several metrics of quality.

The lower disenrollment and switching rates associated with higher star ratings aligns with prior studies.11 This may be a sign of higher satisfaction with these contracts, as enrollees may “vote with their feet” when making enrollment decisions. CMS provides five-star contracts with additional incentives, including the ability to communicate the higher rating to enrollees and special enrollment periods. These factors also may translate to a greater proportion of enrollees remaining enrolled in higher-rated contracts. Further study of patient-reported outcomes would be valuable to assess to what degree lower contract enrollment switching or disenrollment is associated with improved plan satisfaction.

The selection of providers for inclusion in a network is one of the mechanisms by which managed care plans may affect members’ quality experience.22 Our finding that enrollees in contracts with higher star ratings were slightly more often admitted to higher-rated hospitals suggests that higher-rated contracts may have higher-rated hospital networks. This aligns with prior literature that finds an association between star ratings and network quality.7,8 The associations we found between star ratings and network quality are further bolstered by our analysis only of consolidations that occurred within the same state; when a consolidation occurs in the same region, it may be more likely to result in an actual change in networks. We found that enrollees who experienced within-market consolidations were much less likely to be admitted to lower-quality facilities. Our finding of a relationship between star rating and provider rating may suggest that provider networks are indeed a pathway used by MA contracts to improve outcomes; however, more research on this topic is needed. The reduction in hospital readmissions that we found may be related to this higher quality of providers but might also be influenced by care management provided by contracts.

We found that there were some improvements in HEDIS quality measures related to star ratings. To some degree, this could be expected, as these indicators are included in the calculation of the star ratings. HEDIS measures are reported by the contracts using their own data and internal processes, and prior work has found that MA contracts overstate clinical performance on these measures.23 An additional limitation with the HEDIS data is that although screenings are important measures of quality of care, they do not always reflect health outcomes. More work is needed to understand whether the improved screening rates we measured will translate to downstream improvements in cancer and diabetes outcomes. It is also important to note that although many of the changes were significant, not all of the improvements in quality were likely to be clinically meaningful. We could not evaluate the extent to which improved HEDIS performance in higher-rated contracts reflected inaccurate reporting, more comprehensive data collection, or better care.

One potential driver of our findings could be the increased capitated payments and rebates that come with increased star ratings after consolidation. The bonuses to rebate payments must specifically be spent on expanding enrollee benefits. Contracts may be able to offer better-quality networks and supplemental benefits to improve satisfaction and quality outcomes.

Given current payment incentives and the potential ability for increased star ratings to drive higher enrollment4-6 and to allow plans to increase premiums,24,25 it is important to ensure that these star ratings are performing as intended when they capture enrollee outcomes. CMS pays around $6 billion annually in bonus payments,26 and prior work has estimated that $1.1 billion was paid out because of contract consolidations alone.14 Although we found that increased MA star ratings were associated with reductions in disenrollment and switching, as well as improvements in both the use of higher-quality providers and some quality measures, it is important that policy makers weigh these benefits against the costs of running the program. Many of the associated improvements we found were small and might not be clinically meaningful. Also, although consolidations may have given enrollees access to higher-quality care, there may be more cost-effective and targeted ways to achieve the same results. Given that most MA plans receive bonus payments under the current system, there may be opportunities to modify the ratings to further build on the improvements in outcomes that we measured. The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission has recently proposed simplifying the star rating calculation and making quality payments in MA budget neutral, thereby penalizing plans that receive lower ratings.26 It is unclear how these proposed changes would affect the program.

Overall, our study provides evidence that MA contract star ratings capture some important measures of quality and outcomes for enrollees. However, it is unclear whether all of the differences they indicate are clinically meaningful.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Preliminary results were presented at the American Society of Health Economists Conference in Washington, D.C., June 26, 2019. David Meyers was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (Grant No. R36-HS027051) and was paid as a consultant under contract with NORC. Vincent Mor is chair of the Independent Quality Committee at HCR ManorCare; chair of the Scientific Advisory Board and a consultant at NaviHealth, Inc.; and a former director of PointRight, Inc., where he holds less than 1 percent equity.

Contributor Information

David J. Meyers, Department of Health Services, Policy, and Practice at the Brown University School of Public Health, in Providence, Rhode Island..

Amal N. Trivedi, Department of Health Services, Policy, and Practice at the Brown University School of Public Health and a research health scientist at the Providence Veterans Affairs (VA) Medical Center, both in Providence..

Ira B. Wilson, Department of Health Services, Policy, and Practice, Brown University School of Public Health..

Vincent Mor, Department of Health Services, Policy, and Practice at the Brown University School of Public Health and a research health scientist at the Providence VA Medical Center..

Momotazur Rahman, Department of Health Services, Policy, and Practice at the Brown University School of Public Health..

NOTES

- 1.Neuman P, Jacobson GA. Medicare Advantage checkup. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(22):2163–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jacobson G, Damico A, Neuman T. Medicare Advantage 2017 spotlight: enrollment market update [Internet]. San Francisco (CA): Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2017. June 6 [cited 2020 Dec 15]. Available from: https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/medicare-advantage-2017-spotlight-enrollment-market-update/ [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hibbard JH, Jewett JJ. Will quality report cards help consumers? Health Aff (Millwood). 1997;16(3):218–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reid RO, Deb P, Howell BL, Shrank WH. Association between Medicare Advantage plan star ratings and enrollment. JAMA. 2013;309(3):267–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reid RO, Deb P, Howell BL, Conway PH, Shrank WH. The roles of cost and quality information in Medicare Advantage plan enrollment decisions: an observational study. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(2):234–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Darden M, McCarthy IM. The star treatment estimating the impact of star ratings on Medicare Advantage enrollments. J Hum Resour. 2015;50(4):980–1008. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meyers DJ, Mor V, Rahman M. Medicare Advantage enrollees more likely to enter lower-quality nursing homes compared to fee-for-service enrollees. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(1):78–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meyers DJ, Trivedi AN, Mor V, Rahman M. Comparison of the quality of hospitals that admit Medicare Advantage patients vs traditional Medicare patients. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(1):e1919310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li Q, Trivedi AN, Galarraga O, Chernew ME, Weiner DE, Mor V. Medicare Advantage ratings and voluntary disenrollment among patients with end-stage renal disease. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(1):70–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meyers DJ, Belanger E, Joyce N, McHugh J, Rahman M, Mor V. Analysis of drivers of disenrollment and plan switching among Medicare Advantage beneficiaries. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(4):524–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Soria-Saucedo R, Xu P, Newsom J, Cabral H, Kazis LE. The role of geography in the assessment of quality: evidence from the Medicare Advantage program. PLoS One. 2016;11(1):e0145656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hu J, Schreiber M, Jordan J, George DL, Nerenz D. Associations between community sociodemographics and performance in HEDIS quality measures: a study of 22 medical centers in a primary care network. Am J Med Qual. 2018;33(1):5–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Durfey SNM, Kind AJH, Gutman R, Monteiro K, Buckingham WR, DuGoff EH, et al. Impact of risk adjustment for socioeconomic status on Medicare Advantage plan quality rankings. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(7):1065–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meyers DJ, Rahman M, Wilson IB, Mor V, Trivedi AN. Contract consolidation in Medicare Advantage: 2006–2016. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(2):606–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.To access the appendix, click on the Details tab of the article online.

- 16.Huckfeldt PJ, Escarce JJ, Rabideau B, Karaca-Mandic P, Sood N. Less intense postacute care, better outcomes for enrollees in Medicare Advantage than those in fee-for-service. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(1):91–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kumar A, Rahman M, Trivedi AN, Resnik L, Gozalo P, Mor V. Comparing post-acute rehabilitation use, length of stay, and outcomes experienced by Medicare fee-for-service and Medicare Advantage beneficiaries with hip fracture in the United States: a secondary analysis of administrative data. PLoS Med. 2018;15(6):e1002592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Panagiotou OA, Kumar A, Gutman R, Keohane LM, Rivera-Hernandez M, Rahman M, et al. Hospital readmission rates in Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare: a retrospective population-based analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2019;171(2):99–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cornell PY, Grabowski DC, Norton EC, Rahman M. Do report cards predict future quality? The case of skilled nursing facilities. J Health Econ. 2019;66:208–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Austin JM, Jha AK, Romano PS, Singer SJ, Vogus TJ, Wachter RM, et al. National hospital ratings systems share few common scores and may generate confusion instead of clarity. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34(3):423–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Staiger D, Stock JH. Instrumental variables regression with weak instruments. Econom Evanst. 1997;65(3):557–86. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Landon BE, Wilson IB, Cleary PD. A conceptual model of the effects of health care organizations on the quality of medical care. JAMA. 1998;279(17):1377–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cooper AL, Kazis LE, Dore DD, Mor V, Trivedi AN. Underreporting high-risk prescribing among Medicare Advantage plans: a cross-sectional analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159(7):456–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCarthy IM, Darden M. Supply-side responses to public quality ratings: evidence from Medicare Advantage. Am J Health Econ. 2017;3(2):140–64. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Layton TJ, Ryan AM. Higher incentive payments in Medicare Advantage’s pay-for-performance program did not improve quality but did increase plan offerings. Health Serv Res. 2015;50(6):1810–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Report to the Congress: Medicare and the health care delivery system [Internet]. Washington (DC): MedPAC; 2019. June [cited 2020 Dec 15]. Available from: http://www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/jun19_medpac_reporttocongress_sec.pdf [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.