Abstract

Recent efficiency records of organic photovoltaics (OPV) highlight stability as a limiting weakness. Incorporation of stabilizers is a desirable approach for inhibiting degradation—it is inexpensive and readily up-scalable. However, to date, such additives have had limited success. We show that β-carotene (BC), an inexpensive and green, naturally occurring antioxidant, dramatically improves OPV stability. When compared to nonstabilized reference devices, the accumulated power generation of PTB7:[70]PCBM devices in the presence of BC increases by an impressive factor of 6, due to stabilization of both the burn-in and the lifetime, and by a factor of 21 for P3HT:[60]PCBM devices, owing to a longer lifetime. Using electron spin resonance and time-resolved near-IR emission spectroscopies, we probed radical and singlet oxygen concentrations. We demonstrate that singlet oxygen sensitized by [70]PCBM causes the “burn-in” of PTB7:[70]PCBM devices and that BC effectively mitigates it. Our results provide an effective solution to the problem that currently limits widespread use of OPV.

Keywords: organic solar cells, singlet oxygen, stability, burn-in, antioxidant

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

In the world today, energy consumption is on the rise. As such, there is a great need for novel schemes of green electricity generation. Organic solar cells are key in this regard.1 These devices are easy to produce (e.g., through roll-to-roll technology), and their cost of production is lower than that of their inorganic counterparts.1 Organic devices can be thin, lightweight, highly transparent, and mechanically flexible, all of which enables new methods for photovoltaic panels integration. Most importantly, their power conversion efficiencies (PCEs) have increased appreciably in the past year, reaching a current record of 17.3%.2–4 Thus, organic photovoltaics (OPV) is a promising renewable energy technology for electricity generation. Unfortunately, their organic nature also makes them susceptible to degradation mediated by environmental stresses such as oxygen, heat, light, and humidity.5–10 Although device encapsulation can mitigate some of these adverse effects,11,12 the most desirable solution is to address these limitations at a molecular level.

For many common polymer-based OPV systems, such as P3HT (poly(3-hexylthiophene-2,5-diyl)),13–17 PCDTBT (poly[N-9′-heptadecanyl-2,7-carbazole-alt-5,5-(4′,7′-di-2-thienyl-2′,1′,3′-benzothiadiazole)]),18,19 SiPCPDTBT (poly-[(4,4-bis(2-ethylhexyl)dithieno[3,2-b:2′,3′-d]silole)-2,6-diyl-alt-(2,1,3-benzothiadiazole)-4,7-diyl]),20–22 and PDTSTzTz (poly[4,4′-bis(2-ethylhexyl)dithieno[3,2-b:2′,3′-d]silole]-2,6-diyl-alt-[2,5-bis(3-tetradecylthiophen-2-yl)thiazole[5,4-d]-thiazole-1,8-diyl]),23 degradation can start by scission of the polymer side chains. The radicals produced can react with the triplet ground state of oxygen, O2(X3Σg−), and propagate in a standard radical chain oxidation scheme.24 In addition, because light is an integral component in the operation of an OPV device, the photosensitized production of singlet molecular oxygen, O2(a1Δg), must also be considered when evaluating degradation mechanisms.25 Singlet oxygen reacts with a variety of organic functional groups,26 many of which are commonly found in OPV and, as such, will adversely affect the photoactive material. Such photosensitization involves energy transfer to ground state oxygen from an excited state of one of the OPV components. Usually, only states of triplet multiplicity are sufficiently long-lived to encounter oxygen and facilitate the production of singlet oxygen.27 In a multicomponent OPV, triplet state formation can occur via a number of different pathways, including cooperative interactions between the components. In the PCPDTBT:[60]PCBM system (poly[2,6-(4,4-bis(2-ethylhexyl)-4H-cyclopenta [2,1-b;3,4-b′]dithiophene)-alt-4,7(2,1,3-benzothiadiazole)] blended with [6,6]-phenyl-C61-butyric acid methyl ester), it was shown that the fullerene can enhance the formation of polymer triplet states via the polymer:fullerene CT state.21 The resulting presence of long-lived polymer triplets, in turn, enables photosensitization of singlet oxygen, which then causes degradation of these active layers.28 The same degradation mechanism has been identified in the PTB7:[70]PCBM system (poly[[4,8-bis[(2-ethylhexyl)oxy]benzo-[1,2-b:4,5-b′]dithiophene-2,6-diyl][3-fluoro-2-[(2-ethylhexyl)-carbonyl]thieno[3,4-b]thiophenediyl]] blended with [6,6]-phenyl-C71-butyric acid methyl ester).29–31

These light-initiated degradation processes can be mitigated in different ways: using device encapsulation,11,32 by introducing oxygen “getter” and UV blocking functionalities,33–35 by developing more stable organic materials,36–38 and by the addition of radical inhibitors and singlet oxygen quenchers (i.e., additive-assisted stabilization).39,40 The latter approach, which is routinely used with commodity plastics,24 comes with no added complexity and expense in the device processing. Of course, the requirements placed on the stabilizers for use in OPV are strict. For example, the additive must not adversely perturb the morphology of the active layer and the additive’s energy levels must be such that charge carriers trapping is avoided. We reported on successful stabilization of P3HT:[60]PCBM devices using hindered phenols,41 hydroperoxide decomposers,42 and UV absorbers.43 These additives cause a significant reduction in the radicals’ concentration within the photoactive layer due to their antioxidant, radical scavenging, and UV blocking properties, thus extending the lifetime of the devices and increasing the accumulated power generation. Salvador et al. reported on nickel chelates for double-action stabilization of several different polymer:fullerene systems,44 in which the additive both suppresses the concentration of reactive radicals and quenches the singlet oxygen sensitizing triplet state of the polymer. However, for this additive type, the stabilization comes at the expense of device performance, as the nickel quenchers cause trap-assisted recombination effects. Furthermore, the stabilization effect was demonstrated only for a shorter time span (5 h) in these devices.

In this work, we utilize a biomimetic approach to emulate the archetypal photosystems I and II in a leaf45 by using a carotenoid to stabilize the OPV system. Carotenoids are naturally occurring radical inhibitors, antioxidants, and singlet oxygen quenchers known to be effective in multiple biological systems.46,47 β-Carotene (BC) is one member of this large family that has been extensively studied and used as an additive in a range of systems.48 Like other carotenoids, BC acts both as a radical trap and as a quencher of singlet oxygen.49 Evolution has bestowed BC with a unique triplet energy that is slightly lower than the 94 kJ mol−1 excitation energy of singlet oxygen.50 In this way, through a spin-allowed collision-dependent process, the O2(a1Δg) → O2(X3Σg−) transition is complemented by the 1BC → 3BC transition. In the same way, BC can quench the triplet state of another organic molecule and thereby preclude the sensitized formation of singlet oxygen. The caveat here, however, is that a collision complex must be formed between BC and the molecule to be quenched (i.e., they must have orbital overlap), and this may not easily occur in materials where diffusion is curtailed.51

We now demonstrate that, when added to the OPV active layer, BC leads to an appreciable long-term stabilization resulting in a record-high increase in the accumulated power generation (APG). Specifically, we observe a factor of 6 increase for PTB7- and a factor of 21 increase for P3HT-based OPV systems, as compared to the reference devices without the BC additive. We also demonstrate that BC mitigates the so-called “burn-in” degradation commonly observed in many OPV devices. Thus, our results provide an effective solution to the problem that currently limits widespread use of OPV.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Device Performance and Stability.

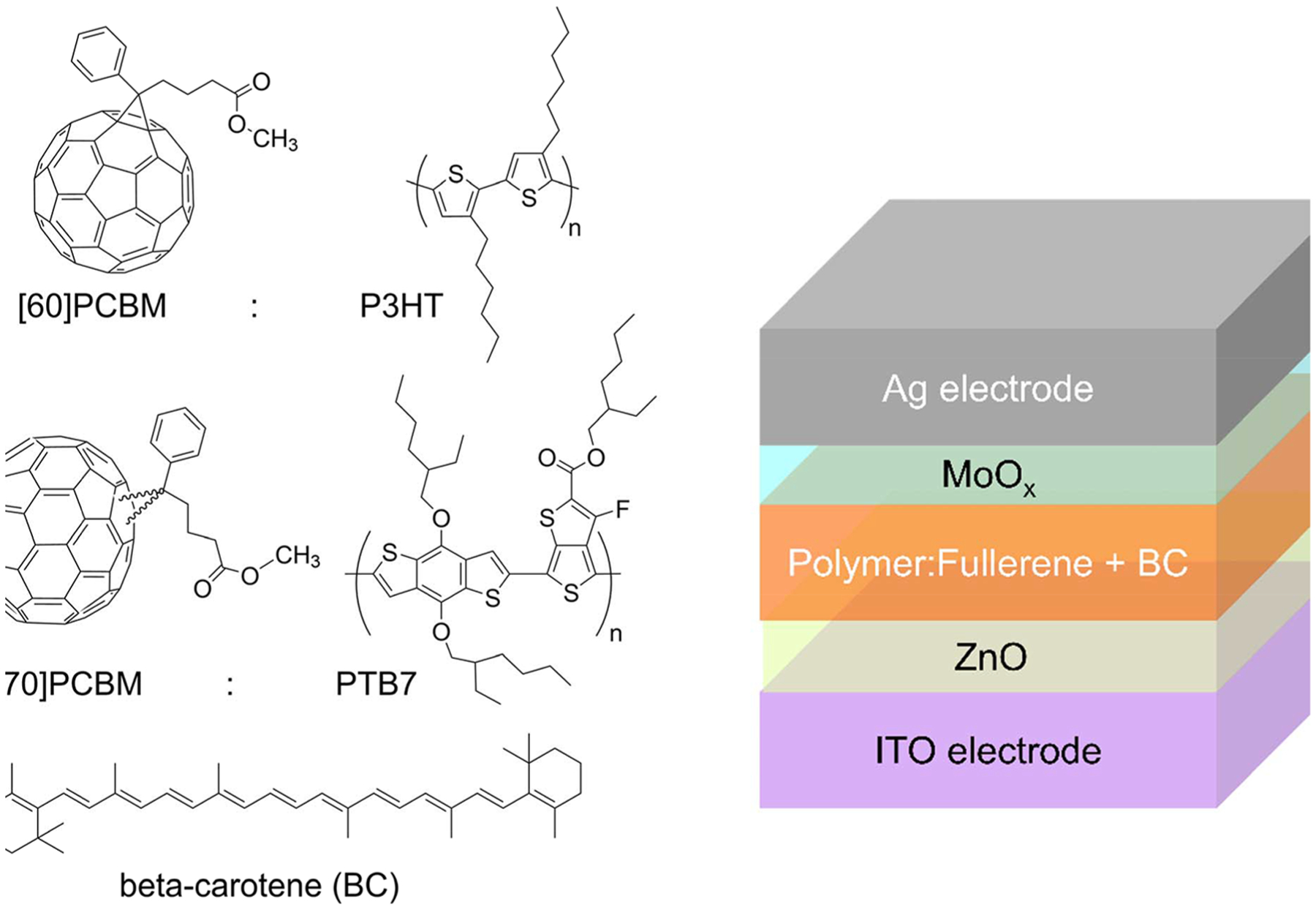

We fabricated devices with BC added in amounts of up to 20% of total polymer and fullerene weight. Shown in Figure 1 are the chemical structures of BC, polymers PTB7 and P3HT, and fullerenes [70]PCBM and [60]PCBM, used in our devices. Although a greater stabilizing effect could be expected upon addition of more BC, this could also diminish device performance. Therefore, we limited the amount of added BC to where the PCE of the devices remains above 2/3 of the PCE for reference devices without additives (see Supporting Information Table S1). Representative current density–voltage, J(V), curves for devices with and without BC are shown in Figure 2, and the pertinent solar cell parameters are given in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Molecular structures and the OPV device structure. Shown are the investigated polymer:fullerene pairs, P3HT:[60]PCBM and PTB7:[70]PCBM, and additive β-carotene (BC).

Figure 2.

J(V) characteristics of PTB7:[70]PCBM (turquoise) and P3HT:[60]PCBM (orange) devices, without and with the additive BC.

Table 1.

Solar Cell Parametersa

| Voc (V) | Jsc (mA cm−2) | FF (%) | PCE (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTB7:[70]PCBM | 0.71 ± 0.01 | 11.9 ± 0.3 | 76.2 ± 0.7 | 6.40 ± 0.21 |

| PTB7:[70]PCBM + 3% BC | 0.72 ± 0.02 | 10.9 ± 0.4 | 61.1 ± 4.9 | 4.80 ± 0.43 |

| P3HT:[60]PCBM | 0.64 ± 0.01 | 5.6 ± 0.3 | 62.2 ± 1.1 | 2.24 ±0.13 |

| P3HT:[60]PCBM + 10% BC | 0.64 ± 0.01 | 6.6 ± 0.1 | 50.6 ± 1.7 | 2.13 ± 0.05 |

The open-circuit voltage (Voc), short-circuit current density (Jsc), fill factor (FF), and power conversion efficiency (PCE) parameters extracted from the J(V) characteristics of the PTB7:[70]PCBM and P3HT:[60]PCBM OPV devices without and with the additive BC are shown. The data are average values obtained from 10 devices along with standard deviations.

As seen from the J(V) curves and Table 1, the P3HT:[60]PCBM devices can be loaded with relatively large amounts (10%) of BC without hampering the device performance. The FF value drops slightly upon addition of BC, which is compensated for by an increased Jsc value, leading to similar PCE values. For the PTB7:[70]PCBM device, the PCE decreases from 6.4% to 4.8% upon the addition of 3% BC, which is again due to changes in the FF and Jsc values. We note that, for higher concentrations of BC, the device performance dropped below 2/3 of the reference PCE; see Table S1.

The stabilities of the PTB7:[70]PCBM and P3HT:[60]PCBM devices containing 3% and 10% BC, respectively, were examined with reference to analogous devices without BC. The unencapsulated devices were stressed for 90 h under ISOS-L-2 accelerated degradation conditions (Figure 3). Data recorded from the reference devices are consistent with what has previously been reported.5,52 Most importantly, we find that the addition of BC appreciably increases the stability of these devices.

Figure 3.

Lifetime measurements of optimized solar cells. (A) Time-dependent performance of PTB7:[70]PCBM and P3HT:[60]PCBM solar cells with and without added BC. (B) Expanded version of the data recorded at early times to better show the burn-in region. The data were recorded under ISOS-L-2 conditions.

The data in Figure 3 can be quantified using a bi-exponential decay function, with time constants t1 and t2 and corresponding initial PCE contributions A1 and A2, to characterize the initial fast and ensuing slow degradation components, respectively:53

| (1) |

To evaluate the kinetics of the stabilizing effect of BC following the conventions of OPV stability testing, two values were extracted from the bi-exponentially fitted curves, tburn-in and tlifetime.54 The initial fast decay period is referred to as the burn-in period, tburn-in, and was calculated analytically as41

| (2) |

The burn-in is followed by a slower degradation process, characterized by tlifetime, which is defined as the time at which a further 20% reduction in performance is seen with respect to the efficiency at the end of the burn-in period.

To assess the BC-mediated improvement in the power generated over time, we compare the accumulated power generation, APG,41 of the reference and BC-stabilized devices, calculated as the integral of the bi-exponential fit of the efficiency of the devices over their lifetime, as expressed by eq 3:

| (3) |

where Pin refers to incident power arising from the 1 sun illumination (1000 W m−2).

Parameters that characterize the light-induced degradation of our OPV devices are presented in Table 2. Clearly, BC appreciably increases the stability of the devices, yielding a 6-fold increase in APG of the PTB7-based devices and a 21-fold increase of the P3HT-based devices, relative to the nonstabilized reference devices. The increase in APG in the presence of BC, for both device types, is caused by the decrease in burn-in intensity (as reflected in smaller A1/A2 ratios) and a significantly prolonged long-term stability (tlifetime). Additionally, we note that in PTB7:[70]PCBM devices, tburn-in is prolonged upon addition of BC, whereas in P3HT:[60]PCBM devices, the burn-in time is decreased. These results suggest different active stabilization mechanisms of BC in these two systems.

Table 2.

Lifetime Parametersa

| A1 (%) | A2 (%) | t1 (h) | t2 (h) | A1/A2 | tburn-in (h) | tlifetime (h) | APGlifetime (kWh m−2) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTB7:[70]PCBM2:3 | 5.40 | 1.24 | 1.47 | 117 | 4.36 | 8.73 | 33.5 | 44.1 |

| PTB7:[70]PCBM (2:3) + 3% BC | 1.41 | 3.19 | 3.00 | 363 | 0.440 | 12.0 | 90.1 | 259 |

| P3HT:[60]PCBM (3:2) | 2.29 | 0.0444 | 1.79 | 26.1 | 51.6 | 12.7 | 17.0 | 4.66 |

| P3HT:[60]PCBM (3:2) + 10% BC | 1.35 | 0.850 | 0.457 | 552 | 1.59 | 3.45 | 126 | 96.5 |

Shown are the extracted parameters of the bi-exponential fit, A1, A2, t1, and t2, as well as the commonly used parameters, tburn-in, tlifetime, and APGlifetime for devices with and without BC. For fitting errors, see Table S2.

The observed BC-mediated stabilization effect correlates well with a decrease in the extent to which the chemical structure of the OPV active layer changes, as detected by Fourier transform IR (FTIR) spectroscopy (see Figure S8). The degradation of the thienothiophene C–C double bond seems to be reduced in the presence of BC. Also, a C–O stretching signal appears in the absence of BC. Both observations are consistent with less oxidation of the polymer in the presence of BC.30,55–57

Radical Scavenging.

To shed further light on the BC-mediated stabilization mechanisms in our devices, we used electron spin resonance (ESR) spectroscopy to quantify the total concentration of radicals in the polymer:fullerene active layers.58 As shown in Figure 4, the presence of BC appreciably decreased the concentration of radicals in films of both PTB7 and the PTB7:[70]PCBM blend under light exposure in ambient atmosphere. Within the errors of our measurements, we were not able to discern a corresponding effect for the P3HT:[60]PCBM system (see Figure S4).

Figure 4.

(A) Radicals concentration in the PTB7:[70]PCBM system as quantified using ESR. Evolution of the total concentration of radicals versus aging time in pure PTB7 and PTB7:[70]PCBM blends with (filled symbols) and without (empty symbols) 3% BC. The initial radical concentrations are 7.13 × 1015 spins g−1 for PTB7, 6.02 × 1015 spins g−1 for PTB7:[70]PCBM, 1.07 × 1015 spins g−1 for PTB7 with BC, and 1.96 × 1016 spins g−1 for PTB7:[70]PCBM with BC. The G-factor for PTB7:[70]PCBM with 3% BC and without is 2.0032 ± 0.0002. (B) Energy level diagram (LUMO and HOMO) of BC, P3HT, and PTB7, showing the proposed mechanism of electron transfer mediated radical scavenging via BC. HOMO values were determined by PESA measurements (see Table S3).

Photoelectron spectroscopy in air (PESA) measurements (Table S2) were used to estimate the ionization potentials (IP) of the pristine materials and their blends, including samples loaded with BC. It is seen that the IP of BC is closely aligned with that of PTB7 (within 100 meV). Thus, electron transfer from BC to the PTB7 radical is possible; i.e., electrons can be transferred from the HOMO of the BC to the HOMO of the PTB7 to scavenge the PTB7 radicals.59–62 Thus, the clear decrease of the radical concentrations in PTB7 and the PTB7:[70]PCBM blends in the presence of BC could come as a consequence of this electron transfer scavenging effect. However, the full reaction scheme for the radical scavenging process remains unknown and could include multiple processes occurring at the same time.

Singlet Oxygen Production.

BC is known to efficiently quench the triplet state of organic molecules.63 This mechanism could also be active in our systems, deactivating polymer and/or fullerene triplet states and, consequently, preventing the formation of singlet oxygen. Singlet oxygen has previously been reported to be responsible for the degradation of PTB7:[70]PCBM systems.29,31,44 In these investigations, a fluorescent probe, singlet oxygen sensor green (SOSG), was used to detect the formation of singlet oxygen. While this, indeed, can indicate the presence of singlet oxygen, it is not a direct measurement. Moreover, this method has some limitations. Because SOSG is itself a sensitizer of singlet oxygen, and it also can react with radicals, it does not provide unambiguous singlet oxygen detection.64,65 In our present work, O2(a1Δg) → O2(X3Σg−) phosphorescence at 1275 nm is used as a direct and unambiguous probe for singlet oxygen.27

To investigate the extent to which the BC-dependent stabilization of the OPV devices might be due to the quenching of singlet oxygen by BC, we performed a series of time-resolved singlet oxygen phosphorescence experiments on PTB7:[70]PCBM films (Figure 5). To probe the contribution of singlet oxygen sensitization from each of the components in the blends, we examined films in which the PTB7:[70]PCBM ratio was varied over a broad range (Figure 5a). Upon irradiation of these films at 400 nm, we observed a pronounced 1275 nm phosphorescence signal,27 indicating that the compounds in the active layer sensitize the production of singlet oxygen. To our knowledge, direct spectroscopic evidence for the formation of singlet oxygen from OPV films has not previously been reported. The observed decrease in signal intensity with a decrease in the concentration of the fullerene component is consistent with the expectation that the pertinent sensitizer of singlet oxygen in this case is [70]PCBM.66–70 However, we note that a singlet oxygen signal is still present in the optimal ratio blend system (2:3) (see Figure S6). We also note that the rate of signal decay increases with a decrease in the fullerene concentration, indicating that PTB7 is a more efficient quencher of singlet oxygen than [70]PCBM. Similar data were obtained for P3HT:[60]PCBM films (see Figure S5).

Figure 5.

Time-resolved singlet oxygen phosphorescence signals. (A) Data recorded from PTB7:[70]PCBM films with different polymer:fullerene ratios. (B) Data recorded from films analogous to those shown in panel A, but with 3% BC added. The percentage in the legend refers to the amount of [70]PCBM in each film. Note the different scales in y axes of the respective figures.

Upon addition of 3% BC to PTB7:[70]PCBM films, we observed a notable decrease in the intensity of the singlet oxygen signal and an appreciable increase in the rate of signal decay (Figure 5b). These two observations clearly demonstrate that BC effectively reduces the concentration of singlet oxygen formed in PTB7:[70]PCBM films. Specifically, the intensity of the phosphorescence signal reflects the amount of singlet oxygen produced, whereas the signal decay reflects the rate at which singlet oxygen is removed. As outlined in the Introduction, these processes require orbital overlap between BC and the quenched molecule (either singlet oxygen or the triplet fullerene/polymer molecule that sensitizes the production of singlet oxygen). Although the signal decays are multiexponential, it is noteworthy that the measured average lifetimes are relatively long (>50 μs in the absence of BC). Our data thus indicate that, at a 3% BC loading, the diffusion distance of singlet oxygen within its lifetime in these films is large enough to allow an encounter with BC molecules. For the P3HT:[60]PCBM films (see Figure S5), a similar trend is seen, however, showing overall lower singlet oxygen signal intensities than for PTB7:[70]PCBM films.

The common singlet oxygen-mediated degradation mechanism of organic compounds includes the formation of peroxides and the subsequent homolytic cleavage into reactive alkoxy and peroxy radicals.14 Successful reduction of the singlet oxygen concentration should thus also result in a reduction of the concentration of radicals, thus giving a possible explanation for the data shown in Figure 4.

Burn-In Stabilization.

For the PTB7:[70]PCBM system, the ESR and singlet oxygen measurements reveal a stabilization effect via both radical scavenging and singlet oxygen quenching, and both potentially add to the overall stabilization of the OPV devices. It should be emphasized that the radical scavenging effect of BC only decreases the radical concentrations in films containing PTB7 and not in neat fullerene films (Figure 4), and that the singlet oxygen signal intensity scaled according to the fraction of fullerene in the blend (Figure 5). To gain a deeper understanding of these effects, we therefore investigated the lifetime of devices with different polymer:fullerene ratios, similar to those used in the singlet oxygen experiments.

Figure 6 shows the lifetime curves in the initial “burn-in” phase of PTB7:[70]PCBM solar cells prepared using different ratios of PTB7 and [70]PCBM. The active layers in these studies have the same thickness as the films investigated in the time-resolved singlet oxygen phosphorescence measurements. The results demonstrate that, without the added BC, PTB7:[70]PCBM devices decay slightly faster, particularly when prepared with larger fractions of the fullerene. In addition, it is clear that, with added BC, the devices with larger fullerene content are more stable, and devices with a larger polymer content show the fastest performance drop during the burn-in period. Because [70]PCBM is the principal singlet oxygen sensitizer in these films, this suggests that singlet oxygen is the main cause of the PTB7:[70]PCBM burn-in. As the BC strongly reduces the concentration of singlet oxygen, it mitigates the burn-in period in PTB7:[70]PCBM devices, leading to an enhancement in APG by a factor of 6, by far the largest reported for these devices to date.

Figure 6.

Lifetime measurements of solar cells with varied PTB7:[70]PCBM ratios. (A) Solar cells without BC and (B) solar cells with 3% BC. The normalized lifetime data of solar cells degraded under ISOS-L-2 conditions are shown. In each case, the data represent the average of three devices.

Although the ESR and singlet oxygen phosphorescence measurements do not reveal the origin of the BC-mediated stabilizing mechanism in the P3HT:[60]PCBM system, it has been demonstrated that the degradation of this system follows a standard radical chain oxidation scheme.24 Although the overall concentration of radicals in our P3HT samples appears to be influenced by BC (see Figure S4), the changes are sufficiently small as to preclude a definitive conclusion without additional studies.

CONCLUSIONS

In this work, we investigated the use of β-carotene (BC) as an inexpensive, roll-to-roll processable, and environmentally friendly additive for photochemical stabilization of PTB7:[70]PCBM and P3HT:[60]PCBM solar cells. In the case of PTB7:[70]PCBM, a short-term stabilization effect during the burn-in phase of the device degradation was observed, in addition to a long-term stabilization, leading to an enhancement by a factor of 6 in the accumulated power generation. Although both radical scavenging and singlet oxygen quenching potentially contribute to the large stabilization effect, we show that singlet oxygen sensitized by [70]PCBM is the main contributor to the burn-in process in these devices. In the case of P3HT:[60]PCBM, a pronounced long-term stabilization of the organic solar cell devices leads to an enhancement in the accumulated power generation by a factor of 21. On the basis of ESR and singlet-oxygen-phosphorescence measurements, we hypothesize that radical scavenging by BC stabilizes the P3HT polymer against radical chain oxidation reactions. Notably, we introduce time-resolved singlet oxygen phosphorescence as a direct probe of singlet oxygen in these OPV systems, whereas only indirect detection techniques have been used to date. In the PTB7:[70]PCBM system, our results point to the fullerene as the main sensitizer of singlet oxygen that causes device degradation but, importantly, also reveal that singlet oxygen is responsible for the burn-in phase of these devices. In addition, BC-stabilized devices tested in this work exhibit the largest stabilization effect reported to date, for both the PTB7 and P3HT materials system. The work therefore not only contributes with important fundamental understandings of the degradation mechanisms in OPV devices, which may also be relevant for new non-fullerene acceptor systems, but it also suggests an inexpensive, green and effective method for prolonging the longevity of OPV devices using β-carotene as stabilizers. This may be an important route for the further up-scaling of this technology using roll-to-roll processing techniques.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Certain commercial equipment, instruments, or materials are identified in this work in order to specify the experimental procedure adequately. Such identification is not intended to imply recommendation or endorsement by the National Institute of Standards and Technology, nor is it intended to imply that the materials or equipment identified are necessarily the best available for the purpose.

Materials.

Poly[[4,8-bis[(2-ethylhexyl)oxy]benzo[1,2-b:4,5-b′]-dithiophene-2,6-diyl] [3-fluoro-2-[(2-ethylhexyl)carbonyl]thieno[3,4-b] thiophenediyl]] (PTB7) and poly(3-hexylthiophene-2,5-diyl) (P3HT) were purchased from 1-Material and Solaris, respectively. [70]PCBM and [60]PCBM were purchased from Solenne, BC from Carbosynth, and the processing additive 1,8-diiodooctane from Alfa Aesar.

Device Fabrication.

Fabrication followed a standard procedure.71,72 Briefly, devices were produced in a nitrogen-filled glovebox with O2 < 1 ppm and H2O < 0.1 ppm. The ITO substrates (150 nm of tin indium oxide on glass, bought from Kintec, 15–20 Ω sq−1) were cleaned in acetone and then isopropanol for 15 min, followed by a UV–O2 plasma treatment. A 30 nm layer of ZnO nanoparticle ink (GenesInk, H-SZ01034) was spin-coated onto the ITO substrate at 2000 rpm for 60 s and annealed on a hot plate at 130 °C for 15 min. Active layers were then spin-coated using chlorobenzene solutions of the polymer:fullerene mixtures. For most studies, a PTB7:[70]PCBM solution of 2:3 ratio (10:15 mg mL−1 solvent) was deposited at 1000 rpm. Similarly, a P3HT:[60]PCBM solution of 3:2 ratio (20:13 mg mL−1 solvent) was deposited at 1000 rpm. For PTB7:[70]PCBM, 1,8-diiodooctane with a volume concentration of 3% was also added to the solution. In case of the experiment where fullerene loading was varied, film thicknesses were kept identical for films with all ratios, at 200 nm. The top layers on a given device, MoOx and then silver, were deposited by thermal evaporation (glovebox connected) at 10−8 mbar base pressure to obtain films of 10 and 100 nm, respectively.

Singlet Oxygen Phosphorescence.

The equipment used to produce and detect singlet oxygen in time-resolved phosphorescence experiments has been described.73 Briefly, samples were excited at 400 nm using the frequency-doubled output of a femtosecond pulsed laser (Spectra Physics Spitfire) operated at a repetition rate of 1 kHz. The characteristic phosphorescence from singlet oxygen at 1275 nm was isolated using, in series, a 1064 nm long-pass filter (SemRock) and a 1270/20 nm band-pass filter (Spectrogon) and focused onto the active area of a near-infrared-sensitive PMT (Hamamatsu, H12694-45). Sample films were housed in a home-built atmosphere-controlled holder that could be purged with dry air, oxygen, or nitrogen as needed. The films were positioned at an angle of 30° relative to the exciting laser beam to minimize the amount of scattered laser light reaching the detector. The possible contributions of emission from the CT state of the active layer (which is on the order of 1 eV and quite broad74) to the emission at 1275 nm can be ruled out. Specifically, the CT singlet states will decay much faster than singlet oxygen, and, thus, any such emission would be convoluted with signal we associate with scattered laser light.75

Radical Concentration by Electron Spin Resonance Spectroscopy.

Standard 5 mm o.d. NMR tubes (which are ESR silent within the g = 2.00 region) were loaded with the fullerene–polymer blend solutions (~0.1 mL to 0.3 mL), which were concentrated in vacuum (ca. 0.1 mbar) at elevated temperature (water bath ca. 45 °C) to form thin films on the walls of the tubes. The films were dried in high vacuum (10−6 mbar) overnight to remove traces of solvent. The weights of the empty sample tubes, with and without the introduced material, were determined with a high accuracy (±0.01 mg) balance. Usually, the weight of the deposited films was in the range of 2–4 mg. The prepared samples were exposed to continuous white light illumination (metal–halogen lamps, power ~ 65 mW cm−2) in ambient air. The ESR spectra were periodically recorded from the samples using a benchtop Adani CMS8400 spectrometer. Integration of the ESR signals was performed using the EPR4K software developed by National Institute of Environmental Health Science (NIEHS). Each sample was characterized by the average number of spins per gram of material following an approach presented previously.76 The concentrations were normalized with respect to the initial radical concentration of the respective fresh sample. The initial radical concentrations were as follows: 7.13 × 1015 spins g−1 for PTB7, 6.02 × 1015 spins g−1 for PTB7:[70]PCBM, 1.07 × 1015 spins g−1 for PTB7 with BC, and 1.96 × 1016 spins g−1 for PTB7:[70]PCBM with BC.

Photoelectron Spectroscopy in Air.

The instrumentation for electron photoemission spectrometry in air has been described earlier.77 To estimate the ionization potentials (IP) of the materials and their blends, photoelectron emission spectra (electron photoemission current versus excitation photon energies) were recorded. Deep UV-light generation by a deuterium lamp (ASBN D130 CM), passed through a monochromator (CM110 1/8m), was used for excitation. A 6517B Keithley electrometer was utilized for both applying +300 V to a counter electrode and measuring the electron photoemission current in a circuit under different excitation wavelengths. The solid layers for PESA measurements were spin-coated from solutions described above at 1000 rpm onto fluorine-doped tin oxide-coated glass substrates.

Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy.

Polymer:fullerene films were prepared in a similar manner as described above for the OPV devices, but on IR-transparent CaF2 substrates. IR spectra of these films were recorded using a Shimadzu IRAffinity-1S spectrometer in transmission mode, both before and after irradiation in a solar simulator (see below).

Device Characterization.

The J(V) curves were obtained using a Keithley 2400 source-measure unit, and a class AAA solar simulator (Sun 3000, Abet Technologies Inc., USA). The lifetime data were collected in a home-built setup, by periodically measuring J(V) characteristics under accelerated conditions according to the ISOS-L-278 degradation protocol standards. The devices were continuously illuminated in ambient air at 65 °C, using an InfinityPV ISOSun solar simulator consisting of an Osram metal halide lamp delivering 1 kW m−2 and characterized using a Keithley 2602A source-measure unit mounted on a Keithley 3706A multiplexer unit, all of which were controlled by home-built Labview software.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

V.T., M.M., and H.-G.R. acknowledge support from the Independent Research Fund Denmark for Project Stabil-O (Grant No. 4181-00519B). M.M., V.T., P.R.O., H.-G.R., M.B., and M.P. acknowledge support from the Villum Foundation for Project CompliantPV (Grant No. 13365). V.T., P.A.T., J.V.G., M.M., H.-G.R., L.I., D.V., and F.A.O. acknowledge support from EU Framework Programme Horizon 2020 for MNPS COST ACTION MP1307 StableNextSol. S.E. acknowledges support from the U.S. Department of Commerce, National Institute of Standards and Technology under the Financial Assistance Award 70NANB17H305. P.A.T. acknowledges support from the Russian Science Foundation (Grant No. 18-13-00205).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsami.9b13085.

Optimization of BC concentration, lifetimes of all solar cell parameters, lifetime fitting errors, ionization potentials, radical concentrations during aging, singlet oxygen detection with respect to polymer:fullerene ratio, and FTIR spectra comparison of reference degraded and stabilized active layers (PDF)

REFERENCES

- (1).Krebs FC; Espinosa N; Hösel M; Søndergaard RR; Jørgensen M 25th Anniversary Article: Rise to Power – OPV-Based Solar Parks. Adv. Mater 2014, 26 (1), 29–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Meng L; Zhang Y; Wan X; Li C; Zhang X; Wang Y; Ke X; Xiao Z; Ding L; Xia R; Yip H-L; Cao Y; Chen Y Organic and Solution-Processed Tandem Solar Cells with 17.3% Efficiency. Science 2018, 361, 1094–1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Zheng Z; Hu Q; Zhang S; Zhang D; Wang J; Xie S; Wang R; Qin Y; Li W; Hong L; Liang N; Liu F; Zhang Y; Wei Z; Tang Z; Russell TP; Hou J; Zhou H A Highly Efficient Non-Fullerene Organic Solar Cell with a Fill Factor over 0.80 Enabled by a Fine-Tuned Hole-Transporting Layer. Adv. Mater 2018, 30 (34), 1801801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Yuan J; Zhang Y; Zhou L; Zhang G; Yip H-L; Lau T-K; Lu X; Zhu C; Peng H; Johnson PA; Leclerc M; Cao Y; Ulanski J; Li Y; Zou Y Single-Junction Organic Solar Cell with over 15% Efficiency Using Fused-Ring Acceptor with Electron-Deficient Core. Joule 2019, 3 (4), 1140–1151. [Google Scholar]

- (5).Turkovic V; Engmann S; Egbe DAM; Himmerlich M; Krischok S; Gobsch G; Hoppe H Multiple Stress Degradation Analysis of the Active Layer in Organic Photovoltaics. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2014, 120 (Pt B), 654–668. [Google Scholar]

- (6).Turkovic V; Engmann S; Gobsch G; Hoppe H Methods in Determination of Morphological Degradation of Polymer:Fullerene Solar Cells. Synth. Met 2012, 161, 2534–2539. [Google Scholar]

- (7).Engmann S; Turkovic V; Hoppe H; Gobsch G Aging of Polymer/Fullerene Films: Temporal Development of Composition Profiles. Synth. Met 2012, 161, 2540–2543. [Google Scholar]

- (8).Gevorgyan SA; Heckler IM; Bundgaard E; Corazza M; Hosel M; Søndergaard RR; dos Reis Benatto GA; Jørgensen M; Krebs FC Improving, Characterizing and Predicting the Lifetime of Organic Photovoltaics. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys 2017, 50 (10), 103001. [Google Scholar]

- (9).Cheng P; Zhan XW Stability of Organic Solar Cells: Challenges and Strategies. Chem. Soc. Rev 2016, 45 (9), 2544–2582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Roesch R; Faber T; von Hauff E; Brown TM; Lira-Cantu M; Hoppe H Procedures and Practices for Evaluating Thin-Film Solar Cell Stability. Adv. Energy Mater 2015, 5 (20), 1501407. [Google Scholar]

- (11).Giannouli M; Drakonakis VM; Savva A; Eleftheriou P; Florides G; Choulis SA Methods for Improving the Lifetime Performance of Organic Photovoltaics with Low-Costing Encapsulation. ChemPhysChem 2015, 16 (6), 1134–1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Ahmad J; Bazaka K; Anderson LJ; White RD; Jacob MV Materials and Methods for Encapsulation of OPV: A Review. Renewable Sustainable Energy Rev. 2013, 27, 104–117. [Google Scholar]

- (13).Manceau M; Rivaton A; Gardette J-L; Guillerez S; Lemaitre N The Mechanism of Photo- and Thermooxidation of Poly(3-Hexylthiophene) (P3HT) Reconsidered. Polym. Degrad. Stab 2009, 94 (6), 898–907. [Google Scholar]

- (14).Abdou MSA; Holdcroft S Solid-State Photochemistry of Pi-Conjugated Poly(3-Alkylthiophenes). Can. J. Chem 1995, 73 (11), 1893–1901. [Google Scholar]

- (15).Abdou MSA; Orfino FP; Son Y; Holdcroft S Interaction of Oxygen with Conjugated Polymers: Charge Transfer Complex Formation with Poly(3-Alkylthiophenes). J. Am. Chem. Soc 1997, 119 (19), 4518–4524. [Google Scholar]

- (16).Manceau M; Rivaton A; Gardette J-L Involvement of Singlet Oxygen in the Solid-State Photochemistry of P3HT. Macromol. Rapid Commun 2008, 29 (22), 1823–1827. [Google Scholar]

- (17).Hintz H; Sessler C; Peisert H; Egelhaaf HJ; Chasse T Wavelength-Dependent Pathways of Poly-3-Hexylthiophene Photo-Oxidation. Chem. Mater 2012, 24 (14), 2739–2743. [Google Scholar]

- (18).Tournebize A; Bussiere PO; Wong-Wah-Chung P; Therias S; Rivaton A; Gardette JL; Beaupre S; Leclerc M Impact of UV-Visible Light on the Morphological and Photochemical Behavior of a Low-Bandgap Poly(2,7-Carbazole) Derivative for Use in High-Performance Solar Cells. Adv. Energy Mater 2013, 3 (4), 478–487. [Google Scholar]

- (19).Aguirre A; Meskers SCJ; Janssen RAJ; Egelhaaf HJ Formation of Metastable Charges as a First Step in Photoinduced Degradation in Pi-Conjugated Polymer: Fullerene Blends for Photovoltaic Applications. Org. Electron 2011, 12 (10), 1657–1662. [Google Scholar]

- (20).Fraga Dominguez I; Topham PD; Bussiere P-O; Begue D; Rivaton A Unravelling the Photodegradation Mechanisms of a Low Bandgap Polymer by Combining Experimental and Modeling Approaches. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119 (4), 2166–2176. [Google Scholar]

- (21).Distler A; Kutka P; Sauermann T; Egelhaaf H-J; Guldi DM; Di Nuzzo D; Meskers SCJ; Janssen RAJ Effect of PCBM on the Photodegradation Kinetics of Polymers for Organic Photovoltaics. Chem. Mater 2012, 24 (22), 4397–4405. [Google Scholar]

- (22).Tournebize A; Seck M; Vincze A; Distler A; Egelhaaf HJ; Brabec CJ; Rivaton A; Peisert H; Chasse T Photodegradation of Si-PCPDTBT:PCBM Active Layer for Organic Solar Cells Applications: A Surface and Bulk Investigation. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2016, 155, 323–330. [Google Scholar]

- (23).Silva HS; Domínguez IF; Perthué A; Topham PD; Bussière P-O; Hiorns RC; Lombard C; Rivaton A; Bégué D; Pépin-Donat B Designing Intrinsically Photostable Low Band Gap Polymers: A Smart Tool Combining EPR Spectroscopy and DFT Calculations. J. Mater. Chem. A 2016, 4 (40), 15647–15654. [Google Scholar]

- (24).Zweifel H Stabilization of Polymeric Materials; Springer Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- (25).Scurlock RD; Wang B; Ogilby PR; Sheats JR; Clough RL Singlet Oxygen as a Reactive Intermediate in the Photodegradation of an Electroluminescent Polymer. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1995, 117 (41), 10194–10202. [Google Scholar]

- (26).Clennan EL; Pace A Advances in Singlet Oxygen Chemistry. Tetrahedron 2005, 61 (28), 6665–6691. [Google Scholar]

- (27).Ogilby PR Singlet Oxygen: There Is Indeed Something New under the Sun. Chem. Soc. Rev 2010, 39 (8), 3181–3209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Dettinger U; Egelhaaf HJ; Brabec CJ; Latteyer F; Peisert H; Chasse T FTIR Study of the Impact of PC 60 BM on the Photodegradation of the Low Band Gap Polymer PCPDTBT under O-2 Environment. Chem. Mater 2015, 27 (7), 2299–2308. [Google Scholar]

- (29).Soon YW; Cho H; Low J; Bronstein H; McCulloch I; Durrant JR Correlating Triplet Yield, Singlet Oxygen Generation and Photochemical Stability in Polymer/Fullerene Blend Films. Chem. Commun 2013, 49 (13), 1291–1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Shah S; Biswas R; Koschny T; Dalal V Unusual Infrared Absorption Increases in Photo-Degraded Organic Films. Nanoscale 2017, 9 (25), 8665–8673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Perthué A; Fraga Domínguez I; Verstappen P; Maes W; Dautel OJ; Wantz G; Rivaton A An Efficient and Simple Tool for Assessing Singlet Oxygen Involvement in the Photo-Oxidation of Conjugated Materials. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2018, 176, 336–339. [Google Scholar]

- (32).Früh A; Egelhaaf H-J; Hintz H; Quinones D; Brabec CJ; Peisert H; Chassé T PMMA as an Effective Protection Layer against the Oxidation of P3HT and MDMO-PPV by Ozone. J. Mater. Res 2018, 33 (13), 1891–1901. [Google Scholar]

- (33).Kettle J; Bristow N; Gethin DT; Tehrani Z; Moudam O; Li B; Katz EA; dos Reis Benatto GA; Krebs FC Printable Luminescent Down Shifter for Enhancing Efficiency and Stability of Organic Photovoltaics. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2016, 144, 481–487. [Google Scholar]

- (34).Fernandes RV; Bristow N; Stoichkov V; Anizelli HS; Duarte JL; Laureto E; Kettle J Development of Multidye UV Filters for OPVs Using Luminescent Materials. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys 2017, 50 (2), 025103. [Google Scholar]

- (35).Engmann S; Machalett M; Turkovic V; Roesch R; Raedlein E; Gobsch G; Hoppe H Photon Recycling across a Ultraviolet-Blocking Layer by Luminescence in Polymer Solar Cells. J. Appl. Phys 2012, 112 (3), 034517–4. [Google Scholar]

- (36).Vahdani P; Li X; Zhang C; Holdcroft S; Frisken BJ Morphological Characterization of a New Low-Bandgap Thermocleavable Polymer Showing Stable Photovoltaic Properties. J. Mater. Chem. A 2016, 4 (27), 10650–10658. [Google Scholar]

- (37).Heckler IM; Kesters J; Defour M; Penxten H; Van Mele B; Maes W; Bundgaard E A Stability Study of Polymer Solar Cells Using Conjugated Polymers with Different Donor or Acceptor Side Chain Patterns. J. Mater. Chem. A 2016, 4 (42), 16677–16689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Leman D; Kelly MA; Ness S; Engmann S; Herzing A; Snyder C; Ro HW; Kline RJ; DeLongchamp DM; Richter LJ In Situ Characterization of Polymer-Fullerene Bilayer Stability. Macromolecules 2015, 48 (2), 383–392. [Google Scholar]

- (39).Turkovic V; Madsen M Inhibiting Photo-Oxidative Degradation in Organic Solar Cells Using Stabilizing Additives In Devices from Hybrid and Organic Materials; Turkovic V; Madsen M, Rubahn HG, Eds.; World Scientific: Singapore, 2019; Chapter 12, DOI: 10.1142/10993. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Yan L; Wang Y; Wei J; Ji G; Gu H; Li Z; Zhang J; Luo Q; Wang Z; Liu X; Xu B; Wei Z; Ma C-Q Simultaneous Performance and Stability Improvement of Polymer:Fullerene Solar Cells by Doping with Piperazine. J. Mater. Chem. A 2019, 7 (12), 7099–7108. [Google Scholar]

- (41).Turkovic V; Engmann S; Tsierkezos N; Hoppe H; Ritter U; Gobsch G Long-Term Stabilization of Organic Solar Cells Using Hindered Phenols as Additives. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6 (21), 18525–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Turkovic V; Engmann S; Tsierkezos N; Hoppe H; Madsen M; Rubahn H-G; Ritter U; Gobsch G Long-Term Stabilization of Organic Solar Cells Using Hydroperoxide Decomposers as Additives. Appl. Phys. A: Mater. Sci. Process 2016, 122 (3), 255. [Google Scholar]

- (43).Turkovic V; Engmann S; Tsierkezos NG; Hoppe H; Madsen M; Rubahn HG; Ritter U; Gobsch G Long-Term Stabilization of Organic Solar Cells Using UV Absorbers. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys 2016, 49, 125604. [Google Scholar]

- (44).Salvador M; Gasparini N; Perea JD; Paleti SH; Distler A; Inasaridze LN; Troshin PA; Lüer L; Egelhaaf H-J; Brabec C Suppressing Photooxidation of Conjugated Polymers and Their Blends with Fullerenes through Nickel Chelates. Energy Environ. Sci 2017, 10, 2005–2016. [Google Scholar]

- (45).Krieger-Liszkay A; Fufezan C; Trebst AJPR Singlet Oxygen Production in Photosystem II and Related Protection Mechanism. Photosynth. Res 2008, 98 (1), 551–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Yasushi K New Trends in Phyotobiology: Structures and Functions of Carotenoids in Photosynthetic Systems. J. Photochem. Photobiol., B 1991, 9 (3–4), 265–280. [Google Scholar]

- (47).Larson RA Naturally Occurring Antioxidants; Lewis, CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- (48).Foote CS; Denny RW; Weaver L; Chang Y; Peters J Quenching of Singlet Oxygen. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci 1970, 171 (1), 139–148. [Google Scholar]

- (49).Edge R; McGarvey DJ; Truscott TG The Carotenoids as Anti-Oxidants - a Review. J. Photochem. Photobiol., B 1997, 41 (3), 189–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Bensasson R; Land EJ; Maudinas B Triplet States of Carotenoids from Photosynthetic Bacteria Studied by Nanosecond Ultraviolet and Electron Pulse Irradiation. Photochem. Photobiol 1976, 23 (3), 189–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Bosio GN; Breitenbach T; Parisi J; Reigosa M; Blaikie FH; Pedersen BW; Silva EFF; Mártire DO; Ogilby PR Antioxidant Beta-Carotene Does Not Quench Singlet Oxygen in Mammalian Cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135 (1), 272–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Abdel-Fattah TM; Younes EM; Namkoong G; El-Maghraby EM; Elsayed AH; Abo Elazm AH Stability Study of Low and High Band Gap Polymer and Air Stability of PTB7:PC71BM Bulk Heterojunction Organic Photovoltaic Cells with Encapsulation Technique. Synth. Met 2015, 209, 348–354. [Google Scholar]

- (53).Krebs FC; Carlé JE; Cruys-Bagger N; Andersen M; Lilliedal MR; Hammond MA; Hvidt S Lifetimes of Organic Photovoltaics: Photochemistry, Atmosphere Effects and Barrier Layers in ITO-MEHPPV:PCBM-Aluminium Devices. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2005, 86 (4), 499–516. [Google Scholar]

- (54).Peters CH; Sachs-Quintana IT; Kastrop JP; Beaupré S; Leclerc M; McGehee MD High Efficiency Polymer Solar Cells with Long Operating Lifetimes. Adv. Energy Mater 2011, 1 (4), 491–494. [Google Scholar]

- (55).Fernandes L; Gaspar H; Tomé JPC; Figueira F; Bernardo GJPB Thermal Stability of Low-Bandgap Copolymers PTB7 and PTB7-Th and Their Bulk Heterojunction Composites. Polym. Bull 2018, 75 (2), 515–532. [Google Scholar]

- (56).Tremolet de Villers BJ; O’Hara KA; Ostrowski DP; Biddle PH; Shaheen SE; Chabinyc ML; Olson DC; Kopidakis N Removal of Residual Diiodooctane Improves Photo-stability of High-Performance Organic Solar Cell Polymers. Chem. Mater 2016, 28 (3), 876–884. [Google Scholar]

- (57).Razzell-Hollis J; Wade J; Tsoi WC; Soon Y; Durrant J; Kim JS Photochemical Stability of High Efficiency PTB7:PC70BM Solar Cell Blends. J. Mater. Chem. A 2014, 2 (47), 20189–20195. [Google Scholar]

- (58).Inasaridze LN; Shames AI; Martynov IV; Li B; Mumyatov AV; Susarova DK; Katz EA; Troshin PA Light-Induced Generation of Free Radicals by Fullerene Derivatives: An Important Degradation Pathway in Organic Photovoltaics? J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5 (17), 8044–8050. [Google Scholar]

- (59).Mortensen A; Skibsted LH; Sampson J; RiceEvans C; Everett SA Comparative Mechanisms and Rates of Free Radical Scavenging by Carotenoid Antioxidants. FEBS Lett. 1997, 418 (1–2), 91–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Everett SA; Dennis MF; Patel KB; Maddix S; Kundu SC; Willson RL Scavenging of Nitrogen Dioxide, Thiyl, and Sulfonyl Free Radicals by the Nutritional Antioxidant Beta-Carotene. J. Biol. Chem 1996, 271 (8), 3988–3994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Al-Sehemi AG; Irfan A; Aljubiri SM; Shaker KH Density Functional Theory Investigations of Radical Scavenging Activity of 3′-Methyl-Quercetin. J. Saudi Chem. Soc 2016, 20, S21–S28. [Google Scholar]

- (62).Di Meo F; Lemaur V; Cornil J; Lazzaroni R; Duroux J-L; Olivier Y; Trouillas P Free Radical Scavenging by Natural Polyphenols: Atom Versus Electron Transfer. J. Phys. Chem. A 2013, 117 (10), 2082–2092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Montalti M; Credi A; Prodi L; Gandolfi MT Handbook of Photochemistry, 3rd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- (64).Kim S; Fujitsuka M; Majima T Photochemistry of Singlet Oxygen Sensor Green. J. Phys. Chem. B 2013, 117 (45), 13985–13992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (65).Gollmer A; Arnbjerg J; Blaikie FH; Pedersen BW; Breitenbach T; Daasbjerg K; Glasius M; Ogilby PR Singlet Oxygen Sensor Green: Photochemical Behavior in Solution and in a Mammalian Cell. Photochem. Photobiol 2011, 87 (3), 671–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (66).Yamakoshi Y; Umezawa N; Ryu A; Arakane K; Miyata N; Goda Y; Masumizu T; Nagano T Active Oxygen Species Generated from Photoexcited Fullerene (C-60) as Potential Medicines: O2- Radical Versus 1O2. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2003, 125 (42), 12803–12809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (67).Arbogast JW; Darmanyan AP; Foote CS; Rubin Y; Diederich FN; Alvarez MM; Anz SJ; Whetten RL Photophysical Properties of C60. J. Phys. Chem 1991, 95 (1), 11–12. [Google Scholar]

- (68).Arbogast JW; Foote CS Photophysical Properties of C-70. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1991, 113 (23), 8886–8889. [Google Scholar]

- (69).Prat F; Stackow R; Bernstein R; Qian WY; Rubin Y; Foote CS Triplet-State Properties and Singlet Oxygen Generation in a Homologous Series of Functionalized Fullerene Derivatives. J. Phys. Chem. A 1999, 103 (36), 7230–7235. [Google Scholar]

- (70).Speller EM; McGettrick JD; Rice B; Telford AM; Lee HKH; Tan CH; De Castro CS; Davies ML; Watson TM; Nelson J; Durrant JR; Li Z; Tsoi WC Impact of Aggregation on the Photochemistry of Fullerene Films: Correlating Stability to Triplet Exciton Kinetics. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9 (27), 22739–22747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (71).Patil BR; Mirsafaei M; Cielecki PP; Cauduro ALF; Fiutowski J; Rubahn HG; Madsen M ITO with Embedded Silver Grids as Transparent Conductive Electrodes for Large Area Organic Solar Cells. Nanotechnology 2017, 28, 405303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (72).Liang YY; Xu Z; Xia JB; Tsai ST; Wu Y; Li G; Ray C; Yu LP For the Bright Future-Bulk Heterojunction Polymer Solar Cells with Power Conversion Efficiency of 7.4%. Adv. Mater 2010, 22 (20), E135–E138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (73).Arnbjerg J; Johnsen M; Frederiksen PK; Braslavsky SE; Ogilby PR Two-Photon Photosensitized Production of Singlet Oxygen: Optical and Optoacoustic Characterization of Absolute Two-Photon Absorption Cross Sections for Standard Sensitizers in Different Solvents. J. Phys. Chem. A 2006, 110 (23), 7375–7385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (74).Szarko JM; Rolczynski BS; Lou SJ; Xu T; Strzalka J; Marks TJ; Yu L; Chen LX Photovoltaic Function and Exciton/Charge Transfer Dynamics in a Highly Efficient Semiconducting Copolymer. Adv. Funct. Mater 2014, 24, 10–26. [Google Scholar]

- (75).Bregnhøj M; Rodal-Cedeira S; Pastoriza-Santos I; Ogilby PR Light Scattering Versus Plasmon Effects: Optical Transitions in Molecular Oxygen near a Metal Nanoparticle. J. Phys. Chem. C 2018, 122 (27), 15625–15634. [Google Scholar]

- (76).Susarova DK; Piven NP; Akkuratov AV; Frolova LA; Polinskaya MS; Ponomarenko SA; Babenko SD; Troshin PA ESR Spectroscopy as a Powerful Tool for Probing the Quality of Conjugated Polymers Designed for Photovoltaic Applications. Chem. Commun 2015, 51 (12), 2239–2241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (77).Gudeika D; Grazulevicius JV; Volyniuk D; Juska G; Jankauskas V; Sini G Effect of Ethynyl Linkages on the Properties of the Derivatives of Triphenylamine and 1,8-Naphthalimide. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119 (51), 28335–28346. [Google Scholar]

- (78).Reese MO; Gevorgyan SA; Jørgensen M; Bundgaard E; Kurtz SR; Ginley DS; Olson DC; Lloyd MT; Morvillo P; Katz EA; Elschner A; Haillant O; Currier TR; Shrotriya V; Hermenau M; Riede M; Kirov KR; Trimmel G; Rath T; Inganas O; Zhang F; Andersson M; Tvingstedt K; Lira-Cantu M; Laird D; McGuiness C; Gowrisanker S; Pannone M; Xiao M; Hauch J; Steim R; DeLongchamp DM; Roesch R; Hoppe H; Espinosa N; Urbina A; Yaman-Uzunoglu G; Bonekamp J-B; van Breemen AJJM; Girotto C; Voroshazi E; Krebs FC Consensus Stability Testing Protocols for Organic Photovoltaic Materials and Devices. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2011, 95 (5), 1253–1267. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.